Abstract

Global attention to penile care is an aspect of men’s health within the Sustainable Development Goal 3 of the United Nations. Environmental and healthcare concerns about the connection between circumcision and penile care are real. According to the World Health Organisation, approximately 665 million males across the world are circumcised. However, social hush about penile problems as contributors to men’s life expectancy further incubates it for millions of men to suffer in silence. The purpose of this study is to open and direct healthcare attention to the dangers of penile disorder with an awareness check and knowledge sources. Designed questionnaire was operated on randomized 1,000 adults of equal gender distribution on mainland Lagos, Nigeria. Multi-stage cluster sampling technique was applied to carefully select a fair representation of study population. Newman’s health awareness theory and its applications by three other authors support this study. Results show that whilst men are more concerned about their penile performance, women showed extra interest in penile care and healthy usage. Open discussions and literatures on penile issues are rare in Nigeria. The study would spur public, academic and research interests in men’s penile health; by recommending the adoption of appropriate penile health policy within the SDG3 of the United Nations.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Sustainable Development Goal three of the United Nations clearly states the need for everyone to enjoy good health and wellbeing. Poor health is partly due to lack of awareness (Blair, Citation2017; Fletcher, Citation2018) especially in Nigeria where the healthcare system and available data are suspect. This paper investigates adults’ awareness of penile challenges and their sources of knowledge about associated problems in Lagos, Nigeria. Findings show that women are more aware about penile problems than men; and interpersonal communication aids general awareness level of penile problems. Opinions strongly support the statement that men’s exclusive property is not always in excellent condition. Understanding these outcomes can help increase awareness, reduce the problems and raise male life expectancy through deliberate healthcare strategies and programmes. Gender relationships, marriage, families and men’s careers can be more positive. Global agencies, governments and public advocators will be able to assist men through healthcare campaigns and investigations.

1. Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Three is a global health action for providing good health and well-being for everyone (Amoo, Citation2018; United Nations, Citation2018). Though this SDG aims at guaranteeing healthy living and comfort for all, its interpretation and execution seem skewed in favour of child health and maternal wellbeing. Male inclusion is more mouthed than implemented; and of all male infirmities, penile ailments suffer the worst recognition within the SDG’s microscope of life expectancy.

Manhood has a life which it cannot care for by itself. Yet, when something goes wrong with it, the man who carries it suffers, sometimes unto death (Cohen, Citation2006; Friedmann, Citation2008; Hickman, Citation2013; van Driel, Citation2010). Like any other part of a man, manhood needs regular devotion. This is because it shapes the life of men as preys and predators, losers and champions as well as healthy and sickly. In any of these situations, manhood conditions the body of a man to attract the attention that transcends gender, cultural and geo-demographic barriers. Penile care is the medical terminology for an act of actively attending to man’s manhood; it refers to natural parenting actions, acquired attitude of young men and expected schedules of male adults in looking after an intriguing organ of life (Paley, Citation2000).

Tracing the history of penile care, Friedmann (Citation2008) raised Saint Augustine’s biblical position that the male organ symbolized the sin in the Garden of Eden that was passed from generation to generation (Bible, Citation1997, Genesis 3:1–17). He however averred that pagan cultures that evolved before Christendom did not see it as a “demon rod” but “an icon of creativity … a link between the human and the sacred, an agent of bodily and spiritual ecstasy … a weapon against women, children and weaker men; a force of nature revered for its potency …, which tied man to the cosmic energy” (page 5). Early Christians venerated virginity as purity (Bible, Citation1997, Song of Songs 4:1–15) and castigated the male organ as animalistic (Bible, Citation1997, Ezekiel 23:20). In contrast, early pagans perceived the male equipment as a thing to worship; to care for, and prepare for cosmic duty without concern for virginity.

In traditional African societies exemplified by the Balubas, in present day Republic of Congo, an active male organ is an indication that a man is “whole or healthy” because it allows him to contribute to the continuity of community. Differentiating between active and inactive manhood, traditional Africans believe that a man in possession of a productive organ should be respected as a muntu; whilst the impotent is a “handicapped” and “dead” mufu (Booth, Citation1977, p. 36, 38). Penile care in the Baluba Kingdom begins with circumcision rites through instructions on sexual matters leading to traditional guide on how to care for the organ through stories and songs. Circumcision is the first act of penile management in a man’s life and it is common to all African societies until the health implications of its handling became controversial globally (Amoo et al., Citation2019; Lawal & Olapade-Olaopa, Citation2016; World Health Organisation [WHO], Citation2006).

The prevalence, causes and symptoms of penile diseases vary and could be region specific. For example, Ajayi (Citation2017) and Odiboh et al., (Citation2017) observed that the people of Lagos, South Western Nigeria, believe that high consumption of sugar, sedentary living, long-distance driving, and consumption of western food lead ultimately to erectile disorder in men. Erectile dysfunction or impotence is one of the most popularly identified penile glitches among the people of Lagos. Arguing that men know little about their penile problems, Spath (Citation2013) identified 19 other challenges of manhood which could be classified as disorders, conditions and diseases.

Penile disorders include phimosis (tight penile foreskin), penile duplication (two instead of one organ), pudendal nerve entrapment (painful nerve compression), hypospadias (wrong positioning of opening tip of the male member) and others. Penile conditions comprise priapism (prolonged post-intercourse erection), lymphargioscelerosis (lymph vessel hardening), penile fracture (excessive bending during erection) and psoriasis (thick red patches). Some of the penile diseases identified by Spath (Citation2013) include penile cancer, peyronie’s disease (extreme curvature at erection) and sexually transmitted ailments such as balantitis (inflammation of the head of the penis), syphilis, warts, herpes and yeasts. Some of these problems are life-threatening and depressing; others have forced carriers to commit suicide and murder.

Men’s life expectancy in Nigeria is shorter, averaging 54.7 years, compared to women’s 55.7 years. At 178th position (World Health Ranking, Citation2018; World Population Review, Citation2018)) in global ranking, Nigerian men live one of the shortest lives in the world. Local health challenges are significant reasons for the development. Urologists (Constans, Citation2003; Haylock, Citation2001; Heidelbaugh, Citation2016) agree that penile cancer, for example is a man’s irreversible death sentence if allowed to fester; and sexually transmitted diseases could cause complications leading to death from HIV/AIDS. For an improvement in life expectancy and better health for men, penile care needs to move from the back yard to the front burner in every climate (Oyero, Oyesomi, Abioye, Ajiboye, & Kayode-Adedeji, Citation2018).

The theoretical basis of this study on men’s penile health is Newman’s health awareness theory. Newman (Citation1994) averred that health cannot be purchased like a commodity but can be lost carelessly. The author affirmed that healthiness is not the absence of disease but a wholesome consciousness of wellness (Bateman, Citation2014); and that in health and disease, the individual and environment are united. Other applications of Newman’s theory (Ayiera, Citation2016; Endo, Citation2017; Macharia, Jelagat, & Juma, Citation2015; Vandemark, Citation2009) uphold this study’s argument that penile care is an individual’s conscious action in need of environmental support and consistent societal communication. Locally, establishments, institutions and non-government organizations are expected execute plans which would help increase public awareness on penile problems using the tools of integrated marketing communication (Odiboh, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Odiboh & Ajayi, Citation2019; Odiboh, Ezenagu, & Okuobeya, Citation2019; Odiboh & Oladunjoye, Citation2019; Odiboh, Omojola, Ekanem & Oresanya, Citation2017). Similarly, private companies should be helping to create internal and external awareness of penile problems as part of their public relations programmes (Ndubueze, Odiboh, Nwosu, & Olabanjo, Citation2019; Nwosu, Odiboh, Ndubueze, & Olabanjo, Citation2019; Olabanjo, Odiboh, Nwosu, & Ndubueze, Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

Consequently, an important objective of this study is to find out men’s and women’s awareness and perception of the need for penile care. Another objective is to find out the types of penile problems known to male and female residents of mainland Lagos, Nigeria. The result of this study would show whether the two genders are aware or unaware, concerned or unconcerned about the condition of men’s unique natural property; given the health and life expectancy implications of (un)conscious action or inaction.

2. Method and materials

A quantitative approach was adopted for this study which allowed the achievement of the research objective. It focuses on a large study population of 2,569,022 inhabitants of mainland Lagos, Nigeria (Nigeria Office of Statistics, Citation2006). Mainland Lagos is the metropolis with the highest mixed concentration of Nigerians, made up of Ajeromi Ifelodun (1,746,634), Mainland (317,980) and Surulere (504,408) local government areas (LGAs) of Lagos State (Nigeria Office of Statistics, Citation2006; Nawrot & Kleer, Citation2018). Multi-stage sampling technique was applied to better sample the cluster of three local government areas within mainland Lagos. At the first stage, Mainland Local Government Area (LGA) with 317,980 inhabitants was randomly selected because of its central link between mainland Lagos and other parts of Lagos State. At the second stage, streets within the Mainland LGA were clustered as commercial and residential. Then, the residential cluster was selected as the research location because it has a more reliable concentration of less distracted potential respondents. At stage three, identified residential streets were selected through balloting in order to give all the streets equal chance to be part of the study location sections. Selected street names were written on separate pieces of paper, folded and dropped in ten black bags; each bag represented one of the ten sections of the research location. During balloting, one after the other, ten blind-folded field assistants picked four streets per jar, to reveal 40 streets in the study area. Bias was avoided with this selection process.

A questionnaire was designed for operation in homes on Sundays, thereby giving all respondents equal chance of selection at all stages (Omojola, Odiboh, & Amodu, Citation2018). Sunday was selected for field operation because it is a work-free day in Nigeria when the people stay at home predominantly with little or no office or work distraction. A primary study of residential streets showed that there are average 50 houses per street with adult occupiers. Twenty-five respondents in each of the 40 streets made up the 1,000 sample size (Wimmer & Dominick, Citation2011, p. 103). Gender equality was observed in respondents’ distribution of 500 males and 500 females.

At stage four, uninhabited houses were omitted from the survey, which commenced from the number which is also the day’s code. For example, on 2 December 2018, the day’s research began at house number 2 and the field assistant went round the street, back to house number 1, applying the questionnaire.

At stage five, gender alternation was observed in the operation of the questionnaire. For instance, where the first respondent was a female, the next must be a male, and then female and so on within an interval of a house. Direct operation of the questionnaire on 1,000 respondents was done and proxy approach was strictly avoided. Responses on the questionnaire were processed using the Scientific Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software. Resulting data were produced through quantitative analysis and the findings presented with graphic illustrations of column and bar charts.

3. Results

Although gender was the key consideration for this study, the questionnaire returned with varying distributions of the respondents’ other demographics. These are education, income, age and religion. Respondents with secondary school education are more than the rest, followed by tertiary education graduates. Respondents with primary or basic schooling are the least. This means that all the respondents are educated enough to understand the essence of the survey.

Nine age brackets were created on the questionnaire and the feedback shows that those aged 18 to 25 are more than the rest. Results indicate that the older the age bracket, the lesser the number of respondents. However, it confirms that only adults between the universal threshold of 18 years and 60+ filled the questionnaire; meaning that all the respondents are mature enough to answer the “adult” questions in the instrument. All the respondents are income earners, granting that more than half of them earn below N1m annually. Christians, Muslims and other religionists filled the questionnaire, meaning that the study did not controvert any religious injunction in the multi-religious mainland Lagos. Even though Christians showed interest in filling the questionnaire more than Muslims and others, it did not suggest that one religion was more important than another in this study.

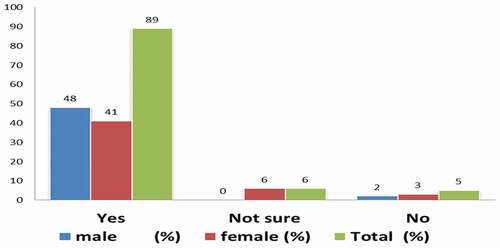

Regardless of gender, almost all the respondents are aware of the need for men to be healthy as shown in Figure . This may be attributed to the general desire for good health by any living being. Curiously, some women are not sure of their awareness of the need for men’s health.

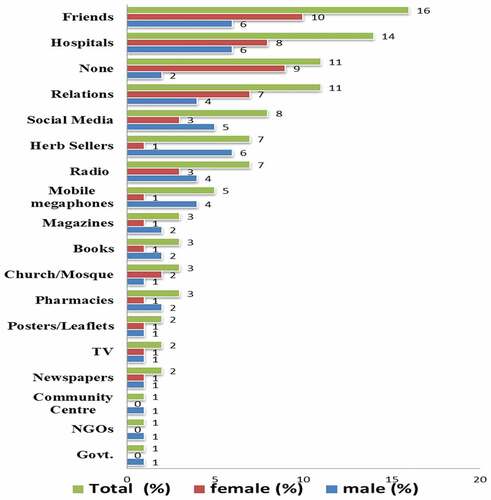

Friends, hospitals, relations and social media are the major sources of awareness of men’s health. Traditional and regular media such as radio, television, newspapers, posters and leaflets are lesser sources of respondents’ awareness of men’s health. Government and non-governmental organizations are the least sources according to Figure . For the female respondents, friends, hospitals and relations play a major role in their awareness of men’s health; whilst for men, friends and hospitals are major awareness sources of men’s health.

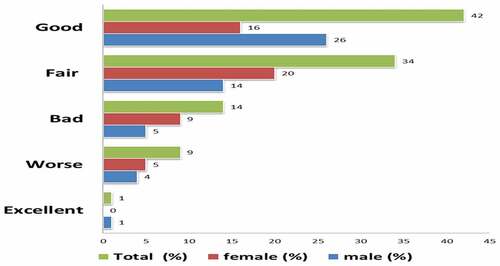

Respondents were requested to score men’s health on a scale of 1–5. Less than half (42%) agreed that men’s health is “good”; whilst 34% said it is “fair.” Whereas some (14%) said men’s health is bad, others (9%) agree it is worse. Overall, women presented lower acknowledgment of men’s health, while men scored themselves higher. This result is clearly shown through Figure .

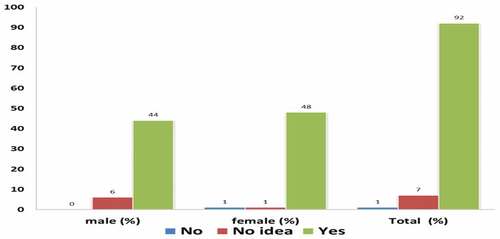

Almost all the respondents (92%) are aware of the need for men to care about their private part according to Figure . However, women’s opinion (48%) on this question is stronger than men (44%) view it; especially as 6% of the men claim that they have no idea about caring for their private part. Gender-based answers to this question suggest that in the eyes of women, privacy handling is crucial to healthiness.

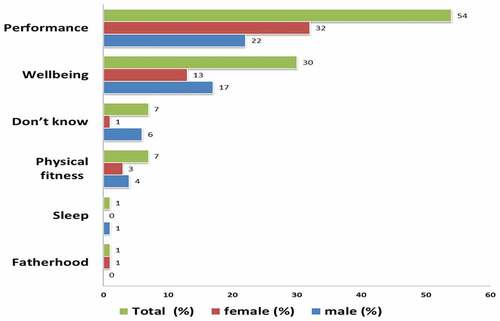

In the eyes of more than half (54%) of the respondents, healthy private part improves men’s performance. Figure shows further that thirty percent said that a healthy private part improves men’s wellbeing. As a major outcome of a healthy private part, women see more of men’s performance than their wellbeing; whilst men view wellbeing more strongly than women. The result shows further that some men (6%) do not know what improvement that a healthy private part could bring.

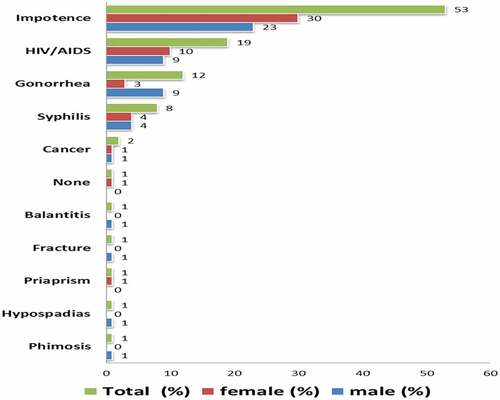

Impotence (53%), HIV/AIDS (19%) and Gonorrhea (12%) are the top three penile problems best known to the respondents. Gender analysis of the prompted open-ended responses shows that impotence is more known to women (30%) than men (23%). However, men (9%) seem to know more about gonorrhea than women (3%). Figure shows that little is known about penile conditions such as priapism and fracture; disorders such as phimosis and hypospadias; and other diseases such as cancer and balantitis. Some of the “unknown” conditions, disorders and diseases are lifetime penile problems whilst others are deadly. In the eyes of the respondents, impotence or sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are the major penile problems.

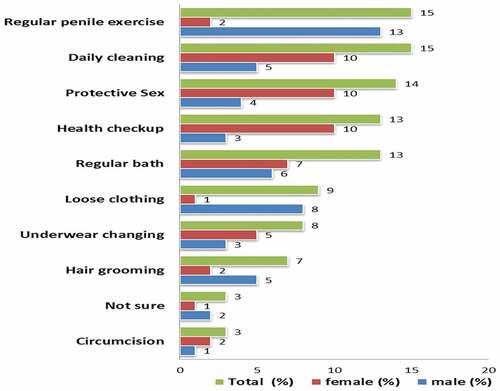

Answers to the question concerning what penile care means are expressed on Figure . Top five responses show that daily cleaning, regular penile exercise, protective sex, regular bath, and health checkup are respondents’ definitions of penile care. However, for women, penile care means daily cleaning, protective sex and health checkup; whilst men understand it as regular penile exercise.

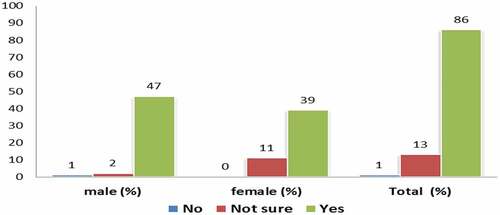

Nearly all the respondents (86%) desire to know more about penile problems and how to handle the care, according to the results on Figure . Expectedly, men are more interested than women; but whilst some men (1%) showed no interest at all, women are merely unsure about their stance. In other words, every female respondent is interested in the matter.

The results presented in Figure show where men and women stand in relation to the issues of penile care and men’s health. In some areas, male and female respondents agree, whilst in others, they disagree. The response of each gender however impacts on the overall results in one way or another. The details of these outcomes are discussed below

4. Discussion

Strong local awareness on the need for men to be healthy as highlighted in this study shows how close the issue is to the hearts of the local people. Men constitute a contributory workforce to the Nigerian economy. Increased gross domestic production (GDP) of the country will undoubtedly be hemorrhaged if the male folks are largely unhealthy. Family finances and cohesion would similarly be affected because men are traditional breadwinners for their wives, children and extended dependents in Nigeria as a whole. Men’s positive contribution to sovereign and families’ economies can only be guaranteed it they are healthy. Individually, an unhealthy man is an unhappy person. Such a psychological state of the mind suppresses self-confidence, negates self-esteem and disrupt gender relationship.

The finding that women showed greater interest in penile care than men is intriguing. It confirms that men’s private property determines how women see and relate with them. Women naturally love to be cared for. Similarly, what women love should receive as much care. This finding also throws up the question: whose property is it? Why should women be more interested in what men carry? There are socio-psychological implications of this finding requiring further studies.

High awareness of the need for men to be healthy expectedly confirms the natural human desire to live forever. As Marcel (Citation1965) and Buber (Citation1970) averred, no man or woman wants to die, even as the world is full of dread and diseases. That is why it is healthy to note that’s the promotion of good health is part of SDG 3, a global response to human desire for longevity; and Nigerian men and women see this as worth pursuing as revealed by this finding.

Human, institutional and technological mediation of drive penile care awareness. However, interpersonal channels of communication are more powerful than techno-social mediation of audio, visual, video and print apparatuses when considering the epistemology of penile health. In the consciousness of Nigerian men and women as people, healthcare delivery is a personal pursuit, especially in an area where the government and social advocators have shown little interest.

Even in this pursuit, it is generally held that male Nigerians are not in excellent health condition as shown in the findings. This result confirms the aforementioned point that Nigerian men live one of the shortest lives globally, amidst poor healthcare delivery system. Paying greater attention to men’s health comes at a cost but the benefits far outweigh the liabilities. Nigerian men would live longer and their global rating index would be better.

The point is made by this study that, to be aware of men’s health is to be mindful of men’s private part. Although health could be physical, mental and even spiritual, the focus of this study is the physical state of affairs of men’s body, part of which is publicly covered. By virtue of this result, men’s private part is generally seen as something to care for, even as some men claim to have no idea about the need for the attention. All said, it remains an important aspect of healthiness.

Caring for men’s private part has benefits as shown in this study. Though such benefits have gender differentials, the general opinion shows what the respondents appreciate (performance and wellbeing) and what they cannot connected (fatherhood and sleep). The point is made that it is individually profitable and socially responsible for a man to have a healthy private part.

It cannot be overemphasized that “penile problem” is a big problem, hence its mass awareness by both genders. The problem is expressed in one or two words where impotence leads the rest. The fact that penile problems are expressed mainly as physical diseases supports the argument of Spath (Citation2013) that men know little about the matter. Absence of most genital conditions and manhood disorders on the table of responses, and the low scores of those mentioned confirm the argument that Nigerian men (and women) need to be properly informed that penile problems transcend sexually transmitted diseases.

Penile care means many things to different people; and it is mainly about taking “regular” action. The word “regular” needs further clarification; whether it means hourly, daily, weekly or even shorter constancy. In the eyes of the people, men should be cleaning, exercising and bathing their private property constantly. Frequency is also implied in the word “regular” because men need to know how many times they should clean, exercise, bathe, and check up their manhood per hour, day, week or month. This aspect of penile care which this study did not anticipate should be handled by healthcare professionals globally and locally.

Protective sex is promoted everyday by healthcare professionals, child spacing advocators and general medical practitioners. So, its appearance in the results of this study is not surprising. However, the nexus between protective sex and penile care in the eyes of the people, especially women, is a curious finding needing further examination.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

This study highlights the instrumentality of men’s icon to gender relationships and socialization within the need for good health and wellbeing objective of UNO’s SDG3. Urgent action needs to be taken to raise public awareness of penile care to avert complications on men’s health and improve their life expectancy rating globally. Sustainable Development Goal 3 needs to be redefined by the United Nations to properly accommodate the healthcare concerns of the adult male. By so doing, male inclusivity in the gender equality goal five of the UNO would also be enhanced.

9Acknowledgements

We appreciate the Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Discovery (CUCRID) for the financial support for this publication.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oscar Odiboh

Dr. Oscar Odiboh is a communication teacher and consultant. He teaches Integrated Marketing Communication, Philosophy of Mass Communication, Advertising, Public Relations and Journalism. He has supervised several industry and academic projects. He has attended numerous academic and professional conferences locally and overseas. He is a Senior Lecturer at Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria.

Dr. Oladokun Omojola is Associate Professor of Journalism and Mass Communication in Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria, with interest in media performance and health communication research. He was a writer with Daily Times from 1988 to 1989 and senior editor with The Guardian in Lagos, Nigeria where he worked before switching to academics.

Dr. Kehinde Oyesomi is a Senior Lecturer of Mass Communication, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria. She is a teacher, adviser, project supervisor, researcher and community development specialist. She specializes on gender, media, indigenous communication and development communication. A member of many professional associations, she has published in numerous local and international journals.

References

- Ajayi, D. (2017). Is sobotone a danger to your health? This is Africa (TIA) forum. (Online). Retrieved from www.thisisafrica.me.

- Amoo, E. O. (2018). Introduction to special edition on covenant university’s perspectives on Nigeria demography and achievement of SDGs-2030. African Population Studies, 32(1). Retrieved from http://aps.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/1170

- Amoo, E. O., Olawole-Isaac, A., Ajayi, M. P., Adekeye, O., Ogundipe, O., & Olawande, O. (2019). Are there traditional practices that affect men’s reproductive health in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review and meta-analysis approach. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1677120.

- Ayiera, F. (2016). the theory of health as expanding human consciousness: Margaret Newman’s contribution to nursing theory and practice. Germany: Verlag Muller.

- Bateman, G. C. (2014, January). Newman’s theory of health as expanding consciousness: A personal evolution. Nursing Science Quarterly, 27(1), 57–12. doi:10.1177/0894318413509725

- Bible. (1997). Life application bible study: New international version. Michigan: Tyndale House Publishers, Illinois and Zondervan Publishing.

- Blair, O. (2017). Penile cancer: The little known form of the disease affecting 600 men in the UK. Independent, (Online). Retrieved from www.independent.co.uk/life-style/penile-cancer-disease-penis-rare-uk-men-surgery-orchid-charity-a7660801.html

- Booth, N. (1977). African religions: A symposium. New York, NY: NOK Publishers.

- Buber, M. (1970). I and Thou. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Cohen, J. (2006). The penis book. London: Ebury Publishing.

- Constans, G. (2003). The penis dialogue: Handle with care. Fairfield: Asian Publishers.

- Endo, E. (2017). Margaret Newman’s theory of health as expanding consciousness and a nursing intervention from a unitary perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 4(1), 50–52.

- Fletcher, J. (2018). Everything you need to know about penile cancer. Medical News Today, (Online). Retrieved from www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323554.php

- Friedmann, D. M. (2008). A mind of its own: A cultural history of the penis. New York: The Free Press.

- Haylock, P. J. (2001). Men’s cancers: How to prevent them, how to treat them, how to beat them. California: Hunter Press.

- Heidelbaugh, J. J. (2016). Men’s health in primary care. New York, NY: Humana Press.

- Hickman, T. (2013). God’s doodle: The life and times of the penis. California: Soft Skull Press.

- Lawal, T. A., & Olapade-Olaopa, E. (2016). Circumcision and its effects in Africa. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(2), 149–157. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.12.02

- Macharia, K., Jelagat, R., & Juma, M. (2015). Applying margaret Newman’s theory of health as expanding consciousness to psychosocial nursing care of HIV infected patients in Kenya. American Journal of Nursing Science, 4(2–1), 6–11. doi:10.11648/j.ajns.s.2015040201.12

- Marcel, G. (1965). Being and having: An existentialist diary. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

- Nawrot, K., & Kleer, J. (Eds.). (2018). The rise of megacities: Challenges, opportunities and unique characteristics. New Jersey: World Scientific.

- Ndubueze, N., Odiboh, O., Nwosu, E., & Olabanjo, J. (2019, April 10–11). Awareness and perception of public relations practices in Public tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, Granada, Spain.

- Newman, M. (1994). Health as expanding consciousness. Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

- Nigeria Office (Bureau) of Statistics, Abuja, Nigeria. (2006). National population estimates. Retrieved from https://nigerianstat.gov.ng

- Nwosu, E., Odiboh, O., Ndubueze, N., & Olabanjo, J. (2019, April 10–11). Public awareness and perception of public relations activities in government agencies in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O. (2019a). Marketology: A philosophy of marketing communication for students, teachers and professionals. Texas: Prolific Communication.

- Odiboh, O. (2019b). Integrated marketing communication in Nigeria. Lagos: APCON.

- Odiboh, O., & Ajayi, F. (2019, April 10–11). Integrated marketing communication and carbonated drinks consumers in Nigeria: A consumerist analysis. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O., Ezenagu, A., & Okuobeya, V. (2019, April 10–11). Integrated marketing communication tools and facials consumers in Nigeria: Applications and connexions. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O., & Oladunjoye, A. (2019, April 10–11). Application of integrated marketing communication tools for promoting computers in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, Granada, Spain.

- Odiboh, O., Omojola, O., Ekanem, T., & Oresanya, T. (2017). Non-governmental organizations in the eyes of newspapers in Nigeria: 2013 – 2016 in view. The Covenant Journal of Communication (CJOC). Department of Mass Communication, Covenant University, 4 (1), 66-70.

- Odiboh, O., Omojola, O., Okorie, N., & Ekanem, T. (2017, July 10th–12th). Sobotone, Ponkiriyon, herbal marketing communication and Nigeria’s healthcare system. SOCIOINT 2017, 4th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

- Olabanjo, J., Odiboh, O., Nwosu, E., & Ndubueze, N. (2019b). Local governments, traditional councils and public relations practices in Ogun State, Nigeria: An awareness study. Journal of EU Research in Business. doi:10.5171/2019685616

- Olabanjo, O., Odiboh, O., Nwosu, E., & Ndubueze, N. (2019a, April 10–11). Public relations practices in local government and traditional institutions in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 33rd International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), ISBN: 978-0-9998551-2-6, Granada, Spain.

- Omojola, O., Odiboh, O., & Amodu, L. (2018). Opinions as colors: A visual analysis technique for modest focus group transcripts. The Qualitative Report, 23(8), 2019–2035.

- Oyero, O., Oyesomi, K., Abioye, T., Ajiboye, E., & Kayode-Adedeji, T. (2018). Strategic communication for climate change awareness and behavioral change in Ado-Odo/Ota local government of Ogun State. African Population Studies, 32(1), 4057–4067.

- Paley, M. (2000). The book of the penis. New York, NY: The Grove/Atlantic.

- Spath, A. (2013). 20 penis problems. Health 24. (Online). Retrieved from www.health24.com/Lifestyle/Man/Your-body/Whats-wrong-with-my-penis-20120721

- The Punch. (2017, October 18). Vaccine scare: A pupil and parents evacuating their children from a Port Harcourt school after rumours of poisonous vaccination by the military. A Cover page photo-story published in La.

- United Nations Organisation. (2018). Sustainable development goals. (Online). Retrieved from www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- van Driel, M. (2010). Manhood: The rise and fall of the penis. London: Reaktion Books.

- Vandemark, L. M. (2009). Awareness of self and expanding consciousness: Using nursing theories to prepare nurse-therapists. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 605–615. doi:10.1080/01612840600642885

- Wimmer, R., & Dominick, J. (2011). Mass media research: An introduction. Australia: Wadsworth.

- World Health Organisation. (2006). Information package on male circumcision and HIV prevention. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/malecircumcision/infopack_en_2.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2008). Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety, and acceptability. Health Organization and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

- World Health Ranking. (2018). Health profile: Nigeria. (Online). Retrieved from www.lifeexpectancy.com

- World Population Review. (2018). Nigeria population 2018. (Online) Retrieved from www.worldpopulation.com