?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Africa like other developing continents has the representation of limiting gaps of foreign exchange, investment and human capital skills. Sustainable development emphasizes that for the limits of both foreign exchange and savings to be reduced, there is need for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to flow inclusive of, foreign skills and technology diffusion for economic development. The objective of the research is to determine how the gaps of foreign exchange, investment and human capital skills has been reduced through the influx of foreign investment for the African economies. Pooled panel data between 2000 and 2018 was utilized for 39 African countries, and analysed with the fixed effect regression model. The results indicate that the influx of FDI has not brought about sufficient decline in the gaps for the selected African economies. The study recommends that government of developing countries need to select with care industries that foreign capital flows into in order to ensure tangible effect on investment domestically as well as deter crowding-out of capital. Furthermore, strategies on protection of domestic investors, enhanced export of production through industrial development as well as lesser consumption proportion, should be implemented, thereby, improving the balance of payment situation. These consequently would result into a gradual decline of the investment and the foreign exchange limits. Thus, resulting into a rise in domestic investment in addition to the much anticipated sustainable development goals of poverty reduction, total well-being and economic development in the continent.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

For several regions all over the globe, sustainable development is a germane discourse as well as aspiration. However, reference to Africa rather suggests pictures of civil disturbance, conflict, disease, poverty and increasing social challenges. This are actually the true situation in quite a number of countries in Africa, nonetheless it is not all encompassing. Africa typically has inadequate productive factors, hence, the reason for the low-income per capita and the least-developed classification the region possesses. Africa likewise other developing countries globally has salient features of limiting gaps of foreign exchange, human capital skills and investment. It is, however, expected that flows of foreign investment should come along with, foreign skills and technology to reduce the savings, skills and equally the foreign exchange limits. There is need, hence, for Africa to make use of external capital to attain the required level of development economically.

1. Introduction

The region of Africa, like other developing continents, has inherent features of limited skill factors, as well as savings and foreign exchange. Sustainable development accentuates the need to propel a decline in these limits of investment and foreign exchange, by encouraging the inflow of foreign investment, essentially specifying the flows that bring along both foreign skills and technological diffusion (Amoo, Citation2018). Developing economies typically have inadequate productive factors (Jaspersen et al., Citation2000); Africa, likewise other developing economies, globally have features of limiting gaps of foreign exchange, investment and human capital skills. It is, however, expected that the inflow of foreign investment should bring along both foreign human capital skills and technology. These hence, results into a decline in the gaps of human capital skills through diffusion of technology, as well as a decline in the gaps of foreign exchange and investment.

An economy could raise new resource and capital by amassing wealth domestically and by capital influx from the external context. Since the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) net inflow enhances investment if sustained, it increases growth and per capita income. This subsequently would bring about a rise in the degree of savings domestically and likewise acceleration of domestic resource, thereby gradually closing the savings gap. This would create a resultant effect of reducing dependence on FDI and thereby bring about development of the economy. However, for Africa, the gaps are becoming incessantly wider instead of closing up as experienced by other developing regions like Asia, Europe and Latin America. The desired sustained increase in income growth and by proxy income per capita is not achieved to lead to the anticipated increased savings and investment. This will make economic development farfetched, as FDI does not successfully substitute for the limited local factors to permit increase in total output, but rather witnessing continuous capital needs for these economies (Chenery & Stout, Citation1966; Easterly, Citation1999; Garcia-Molina & Ruiz-Tavera, Citation2009).

Developing countries are characterized with minimal per capita income; invariably, these countries likewise possess minimal volume of savings and this literarily translates to inadequate capital domestically (Jaspersen et al., Citation2000). This shows that the limit of capital, as well as savings is inadequate to meet investment demands. High skill and technology for developing economies are equally deficient factors of production and this limits investment capability in the economies, thereby restricting ability to attain required level of economic development. Unfavourable balance of payment position, which results from an excess volume of import compared to export creates a foreign exchange gap. The skills and savings gap, coupled with the foreign exchange gap, makes it imperative for inflow of external resource to augment the limits of factors of production. The probable challenges regarding savings, skills and foreign exchange could be sorted out in the time being through the addition of foreign resource, to substitute for absent indigenous resources. These thereby, permit a rise in aggregate productivity, which would gradually increase limited factors of production, reduce dependence on foreign capital and consequently result into economic development (Ahmed et al., Citation2015; Chenery & Stout, Citation1966; Szkorupova, Citation2015; Workneh & Francken, Citation2015).

Developing African countries have increasingly seen the inflow of external assistance as an avenue for economic of development as well as providing growth of income and job creation. Nations do open up international capital flow systems and practice other strategies to pool in foreign finance. The imminent concern is the determination of the most appropriate approach to practice strategies domestically. This could enable the indigenous economic environment to make the most of the gains of the existence of international finance. However, countries have neglected possible avenues to develop the domestic investment to be able to sustain the productive engagement advantage. Nevertheless, countries are engrossed with the general effect of flow of capital on the progress of the entire economy and all wellbeing-boosting procedures. This could be attained through the avenues by which these gains effectively contribute towards greater growth of the economy, essentially the effective device for reducing poverty in developing economies (Adegboye, Citation2014; Ahmed et al., Citation2011; Zandile & Phiri, Citation2019). The research therefore appraised the effect of net inflow of foreign capital on closing foreign exchange likewise investment gaps of selected economies in Africa. In addition, it evaluated the extent to which the net inflow of foreign finance has successfully closed the gaps of limiting productive factors in the selected African countries.

2. Theoretical framework and literature review

Developing continents Africa inclusive, portend features of minimal per capita income; limited savings that literarily translates to inadequate investment domestically (Jaspersen et al., Citation2000; Lee & Sami, Citation2019). The gaps of investment can be explained thereby, as savings which is insufficient to meet investment demands. Skill and technology for developing economies are equally deficient factors of production and this limits investment capability in the economies, thereby restricting ability to attain required level of domestic engagement economically (Ullah et al., Citation2014). Also, a higher volume of import compared to export creates a foreign exchange gap. The skills and savings gap, coupled with the foreign exchange gap, creates the need for foreign assistance influx to augment the limits of factors of production. The impending restrictions of foreign exchange, human capital skills and investment, could be temporarily relaxed by inflow of foreign assistance, to substitute for lacking local production factors. This thereby, results into an increase in total output, which gradually increase limited factors of production. It would consequently reduce dependence on foreign capital, and thus result into economic development (Bakare Aremu & Bashorun, Citation2014).

FDI net inflow is also expected to reduce the limit of scarce production factors, increase total productivity, thereby gradually increasing income per capita. These increases gradually boosts domestic investment, which is needed to attain increased national output and economic development. The theory of the determination of a nations’ trade pattern developed in Sweden from Heckscher (Citation1919), and Ohlin (Citation1933), states that those products that require (profuse production factors) for producing more of and fewer of (limited factors) are exported in trade for commodities which require for resources counter wise. Hence tangentially, we export factors that are in abundance and import factors that are scarce Jones (Citation2002). The Heckscher-Ohlin theory forecasts that countries export the commodity that utilizes the abundant factors exhaustively, and import the products utilizing limited resources or factors intensely. An economy that is relatively labour-abundant should possess high proportion of labour relative to other resources than it is available from the remaining parts of the globe. A commodity also is said to be labour intensive, if labour cost has more proportion of its worth than the value of other products (Opp et al., Citation2009).

The factor endowment theory states that physical capital (non-human) and high skilled labour that is technical workers (human capital) are abundant in industrialized countries. Unskilled labour are however scarce in developed countries. This implies that the opposite pattern of abundance and scarcity of physical capital; high skilled labour, and unskilled labour is obtainable in developing economies. Therefore, for developing countries, there is limited supply of physical capital, technology and skilled human capital, and these can be filled by inflow of foreign capital which comes with skills and technology (Jurcic et al., Citation2013).

According to the theory of FDI and new growth, the net influx of foreign capital is expected to reduce the limits of production components, which limit development and rather improve growth and living standard for the economies. Once an economy is liberalized resulting into easing up the capital account, challenges resisting the inflow of external finance decline. An increase in investment, funded by external savings results into a sturdy progression of the local rate of interest, and thereby greater investment and quicker economic growth (Prasad et al., Citation2007).

However, an indirect association between external finance inflow and savings gap has been highlighted by previous research regardless of the sturdy hypothetical standpoint for a direct impact on economic development. This was asserted by Taslim and Weliwita (Citation2000), and also Easterly (Citation1999) summed that there was no evidence that foreign investment was condition for growth. According to Nushiwat (Citation2007), however, there is a general direct association between foreign finance inflow and savings. This is also corroborated by the research of Baltabaev (Citation2013), which indicated the condition of absorptive capacity of the concerned countries being determinant for positive relationship.

3. Research methods

An analysis of the impact of the net FDI inflow on closing the gaps of foreign exchange and investment of selected countries in Africa is executed in a conceptual structure of a regression analysis on cross-country basis with the use of data on foreign capital inflows for 39 countries in Africa over the period beginning from 2000 to 2018. The countries selected were from four sub-regions of Africa that comprise the sub-Saharan region and the period selected represented the appropriate balance for the panel data set. Based on theory, the likely limits of savings, skills, and foreign exchange could be in the interim loosen up by inviting foreign resources, to substitute for limiting local factors. These thereby, permit an increase in total output, which gradually increase limited factors of production and reduce dependence on foreign capital (Workneh & Francken, Citation2015).

Chenery and Stout (Citation1966) noted a triple phase development pattern through which economic progress advances at the pace that is acceptable for the scarcest resources; the gaps of savings, skill and foreign exchange. At the foremost phase of development, growth is probably investment restricted as encountered by majority of developing countries. It is anticipated that external technology and skill result into a decline in the gap of skill. Likewise, inflow of investment results into a decline in the savings and foreign exchange gaps. This theory is adopted for the African experience, because of the apparent gaps of savings and skills resulting into the dire need of foreign capital for economic development, as asserted in the model.

In the national income equation

To derive savings equation

Where; C = Consumption, I = Domestic capital formation or Investment

X = Export, M = Import and S = Savings.

From EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2)

National income is given as, Simplifying further we have,

If

Therefore, dearth in payment balance; and need for financing.

The gap of foreign exchange is as follows:

Where F = capital import.

Therefore, (this means actual savings gap equals actual foreign exchange gap).

This as well is the savings gap that requires closure via external assistance.

However, the surplus of premeditated capital formation above savings might vary from the volume of excess planned importation above exportation. If , then all investment will not be realized. The required foreign assistance equals the greater of the dual limits. Supposing the foreign exchange limit is greater than the gap of investment, importation reduces and external assistance declines. This if viewed along with the contributions inclined towards development efforts, makes growth limited. The import of capital for the foreign exchange gap will remove the limitation placed on trade and therefore close the trade gap.

The empirical model for this study draws insight from Adegboye (Citation2014) that covered 39 SSA countries which are: Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central Africa Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cote d’Voire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda and Zambia.

These countries are selected from the Central, Eastern, Southern and Western African and with regards to the accessibility of Data. The study engaged data from Human Development Index (HDI) and World Development Indicators (WDI) for the period (2000–2018).

3.1. Empirical Model

A model of 39 SSA economies as listed above is selected premised on data availability for the period. Therefore, the baseline model for the study is specified implicitly as:

EquationEquation (7)(7)

(7) can be simplified explicitly as:

Where: HDI: means Human Development Index as proxy for economic development, FDI: means foreign direct investment; INFR means infrastructure; ROI means rate of return on investment, DOMINV: means Domestic investments which represents Savings Gap, IMEXP means trade deficit which represents the Foreign Exchange Gap, ε is the error term which encapsulates all descriptive variables that are excluded from the model.

β0 is the constant term, β1, β2, β3, β4, β5 are the constants of the descriptive variables, while “i” and “t” represents entities and time respectively. Entities in this study refer to the 39 SSA countries listed above, and time represents the period of study (2000–2018). The A priori expectation for the study is given such that: β1 > 0, β2 > 0, β3 > 0, β4 > 0, β5 > 0. This implies that, the explanatory variables have a direct impact on economic development.

The variables utilized in the specification of the model are from two sources: the WDIs (WDI, Citation2017) and the Human Development Index (HDI, Citation2017). To estimate the specified model, the study employed the fixed effects regression model.

3.2. Data sources and measurement

The data was sourced from WDIs (WDI, Citation2017) and Human Development Index (HDR, Citation2017). The variables are; Human Development Index (HDI), that is used as proxy for economic development. The components of HDI used are life expectancy at birth; adult literacy; school enrolment and per capita gross domestic product. Foreign direct investment (FDI), is measured by net inflow percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP); Infrastructure (INFR), is measured as access to electricity percentage of population; Rate of return on investment (ROI), is measured as inverse of GDP Per Capita Local Currency Unit (LCU); Domestic investments (DOMINV), is measured as Gross Fixed Capital Formation as percentage of GDP, which represents the Savings Gap; and trade deficit (IMEXP), is measured by the total value of import minus the total value of export, which represents the Foreign Exchange Gap.

4. Results

The results of the descriptive analysis provide a simple summary of the variables selected. This includes: Human Development Index (HDI), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Infrastructure (INFR), Return on Investment (ROI), Domestic Investment (DOMINV) and Trade Deficit (IMEXP). Various descriptive statistics used were mean, range, standard deviation and so on. The mean as used here implies the average of the dataset. It is determined by summation of the entire numbers in the dataset divided by the entire volume of the numbers. The median is the middle value of every variable in the dataset. The standard variation is termed as the direct squared value of the deviation, minimum rate is the smallest figure for a dataset, maximum rate is the greatest figure in the dataset and the range is the difference between the greatest and the smallest figure in the dataset. The sloppiness depicts the level of lop-sidedness of the dispersion which could be indirectly or directly sloped. The kurtosis assesses the level to which the rate of dispersion is concentrated around the mean. It may be mesokurtic (if the value of kurtosis is = 3), platykurtic (if the value of kurtosis is <3) and leptokurtic (if the value of kurtosis is >3) as presented in the descriptive statistic presentation in Table .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Table represents the outline of statistics of each variable utilized in the study. Human development index (HDI) had an average value of 0.46 and it ranged between 0.268 and 0.779 during the period of study (2000–2018). The result also showed the dispersion of Human Development Index about the mean coefficient of 0.101. The dissymmetry value of 7.15 that is above the zero threshold indicated that the human development index is positively skewed. The kurtosis coefficient ˂3 indicates that the Human development index is platykurtic. The uniformity of the sequence was investigated by the kurtosis as well as the skewed uniformity investigation; the hypothesis was stated in the null form, the analysis depicts that the sequence has normal distribution, though the analysis’ p value is <0.5. This is lower than the 5% level of significance, which shows that HDI does not have normal distribution.

The mean coefficient of foreign direct investment (FDI) during the study period is 5.4 and it ranged between 6.5 and 159.7. The result also revealed the distribution of the FDI around the average coefficient of 11.92 (standard deviation), indicating the sequence is sparsely distributed about the average. The skewed coefficient was 89.89, which is above the zero threshold indicates that FDI has positive direct skewness. The kurtosis coefficient >3.0 indicates that FDI is leptokurtic. The uniformity of the sequence was verified by the kurtosis and the skewness uniformity analysis; the hypothesis stated in the null form of the analysis depicts that the sequence are uniformly dispersed; however, the p value of the analysis is less than 5%. This is lesser than the 5% level of significance and it shows that FDI does not have normal distribution.

The mean of infrastructure (INFR) during the years under review is 35.6834 and it ranges from 0.15 to 99.4. The result further revealed the distribution of infrastructure around the average coefficient of 24.94 (standard deviation) as presented in (Table ). This indicates that the sequence is sparsely distributed about the average. The skewed coefficient was 7.95, which is above the zero threshold indicates that INFR has positive direct skewness. The kurtosis coefficient <3.0 indicates that INFR is platykurtic. The uniformity of the sequence was verified by the kurtosis and the skewness uniformity analysis; the hypothesis stated in the null form of the analysis depicts that the sequence are uniformly dispersed, however, the p value of the analysis is less than 5%. This is lesser than the 5% level of significance and it shows that infrastructure does not have normal distribution.

The mean of rate of return on investment (ROI) during the years under review is 0.2 and it ranges from 0.0 to 0.79. The result further revealed the distribution of rate of return on investment around the average coefficient of 0.1 (standard deviation) as presented in (Table ). This indicates that the sequence is sparsely distributed about the average. The skewed coefficient was 65.90, which is above the zero threshold indicates that ROI has positive direct skewness. The kurtosis coefficient >3.0 indicates that return on investment is leptokurtic. The uniformity of the sequence was verified by the kurtosis and the skewness uniformity analysis; the hypothesis stated in the null form of the analysis depicts that the sequence are uniformly dispersed, however, the p value of the analysis is less than 5%. This is lesser than the 5% level of significance and it shows that (ROI) does not have normal distribution.

The mean of Domestic Investment (DOMINV) during the years under review is 22.37252 and it ranges from 1.96 to 145.746. The result further revealed the distribution of DOMINV around the average coefficient of 11.71 (standard deviation) as presented in (Table ). This indicates that the sequence is sparsely distributed about the average. The skewed coefficient was 43.47, which is above the zero threshold indicates that DOMINV has positive direct skewness. The kurtosis coefficient >3.0 indicates that DOMINV is leptokurtic. The uniformity of the sequence was verified by the kurtosis and the skewness uniformity analysis; the hypothesis stated in the null form of the analysis depicts that the sequence are uniformly dispersed, however, the p-value of the analysis is less than 5%. This is lesser than the 5% level of significance and it shows that DOMINV does not have normal distribution.

The mean of Trade deficit (IMEXP) during the years under review is −3.28×1010* and it ranges from −4.4×1012* to 1.4×1012*. The result further revealed the distribution of trade deficit around the average coefficient of 3.57×1011* (standard deviation) as presented in (Table ). This indicates that the sequence is sparsely distributed about the average. The skewed coefficient was −88.3, which is below the zero threshold indicates that IMEXP has negative skewness. The kurtosis coefficient >3.0 indicates that trade deficit is leptokurtic. The uniformity of the sequence was verified by the kurtosis and the skewness uniformity analysis; the hypothesis stated in the null form of the analysis depicts that the sequence are uniformly dispersed, however, the p value of the analysis is less than 5%. This is lesser than the 5% level of significance and it shows that (IMEXP) does not have normal distribution.

Joint test of significance on named regressors—Test statistic: F(5, 733) = 250.924

with p value = P(F(5, 733) > 250.924) = 4.44022 × 10−156*

Test for differing group intercepts

Null hypothesis: The groups have a common intercept Test statistic: F(2, 733) = 38.1887

with p value = P(F(2, 733) > 38.1887) = 1.67199 × 10−16*

Relating EquationEquation (8)(8)

(8) with Table , we have the resulting model as follows:

Table 2. Panel fixed effects coefficients standard

From Table , Infrastructure and Domestic investment presents a significant relationship with

HDI, while FDI, ROI, and IMEXP do not have a significant relationship with HDI at α = 0.5. From Table , the overall model is significant with p value of 8.2×10−161*. Akaike criterion (−2054.32), Schwarz criterion (−2017.45), Hannan-Quinn (−2040.10), shows the model performance. Durbin-Watson (0.17506) test for presence of autocorrelation in the model, Within R-squared (0.631217); shows that the model is good, the closer to unity the better. The joint test on regressors gives F(5, 733) = 250.924, and a p value 4.44022×10−156*, this shows that the regressors are suitable for the model. The test for differing group intercepts with F(2, 733) = 38.1887, and p value of 1.67199×10−16*, where the null hypothesis posits that “there is an accepted intercept for the group”, hence, the null hypothesis is rejected and says that the groups does not have a common intercept.

Table 3. Model performance

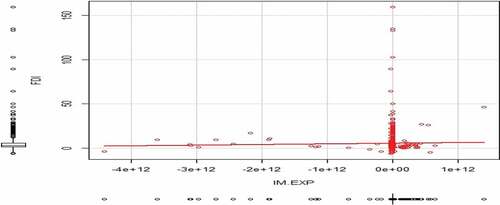

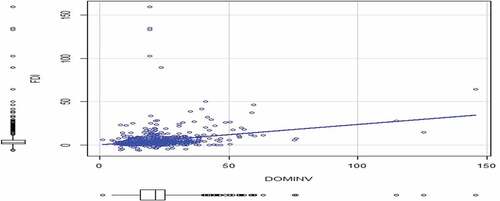

Figures and above, represents the relation amid FDI, domestic investment and foreign exchange gaps for the 39 African countries. From Figure , it can be seen that as FDI increases, the gap of foreign exchange also increases, for the selected period. Also from Figure , it could be deduced that as FDI increases, the gap of savings could be seen to increase though quite insignificantly, for the review period. From the figures, as FDI grows in the region, the gaps of foreign exchange increased rather than reduce for the selected period, thereby, rather escalating the already deprived balance of payment deficit. Also, the domestic investment gaps has intangible increase, which is too insignificant to ginger domestic economic activities in the selected countries.

4.1. Non-parametric test: correlation estimate coefficient test on FDI and gaps of investment and foreign exchange

Figures and both represents the non-parametric test results for FDI and the gaps of investments and foreign exchange. From Figure , it can be seen that as FDI grows, the gaps of foreign exchange which is expected to reduce and hence close for the selected period is rather widening and not much of closing up. This invariably means that rather than the limit of foreign exchange closing for selected countries in the region, it is widening. Hence, the scarce productive factors are rather getting more limited than abundant as it is being experienced in some other developing economies globally essentially Asia, Europe and Latin America.

It can also be deduced from Figure that as FDI grows, it also expected that domestic investment growth will appreciate commensurately. However, from the test, we deduce that the growth of investment domestically has intangible increase for the selected countries in the region. As foreign capital inflow increases, it is expected that it would bring about a resultant effect on the impact of domestic investment. It is expected that as FDI grows, domestic investment should also grow as it does in other developing regions of the world. However, for the selected countries of Africa this cannot be seen. The increase is rather not significant enough to close the gap of savings thereby, too weak to effect any change regarding the already existing gap of savings and investment domestically.

5. Discussion

The study provided empirical results for selected 39 African countries, through the evaluation of panel data that was pooled between 2000 and 2018 with the fixed effect regression model. The study found that FDI do not have a tangible impact relating to closing the investment as well as the foreign exchange gaps. This depicts that for Africa, the sustainable development goals are apparently yet implausible, as poverty reduction and total wellbeing of citizens are not being appreciably attained. This is in consonance with the findings of Adegboye et al. (Citation2016a) that selected countries’ return on investment rate had no significant impact even on attracting the inflow of foreign capital, despite enormous opportunities available in these economies. However, the inability of the foreign capital to close gaps of exchange rates and investment is contrary to the theory stated by Chenery and Stout (Citation1966), but is corroborated by the study of Malikane and Chitambara (Citation2017), as the results showed a weak positive relationship with FDI and total factor productivity in Africa.

The study hinges on the deficiency of the African region to entirely absorb foreign technology as the restricted ability to engage it, hence, describing it as being relatively laid back (Blomstrom & Kokko, Citation2003). The flow of foreign investment should increase domestic activities, which will invariably increase income, savings and gradually close the investment and foreign exchange gaps. This will enable the country to sustain further development from its own resources and reduce dependence on foreign capital as observed in literature, and as it obtains in other developing countries globally for instance, in Asia, Europe and Latin America. As net influx of FDI increases, the consequent rise in income habitually do not impact tangibly in relation to investment in the domestic sector. This has not tangibly brought about a decline in the savings gap; neither did it result in the decline of the gaps in foreign exchange. However, the inflow of FDI is capable of inciting an increase in the domestic sector activities, and also increase domestic production. These would reduce import dependence, as well as increase potentials of export due to increased domestic production, hence improving the balance of payment misalignments. Thereby, consequently creating better living standard for the citizenry of the developing African economy. However for the research work on the African experience, rather than close the factor limit of savings, foreign exchange as well as skills, the gaps rather increased.

This research work found that as FDI increased in the economies, so did the gaps of foreign exchange and investment increase over the years. This can be clarified by the fact that the positive effect of foreign investment is minimal for the African economies. Also, the sector of inflow of FDI, which is usually the capital intensive resource exploitation for the African region, more often than not crowd-out investment domestically. This is not the case for other developing regions like Asia, Europe and Latin America, where a tangible positive effect of foreign investment is found on economic development (Susic et al., Citation2017). For Africa, in spite of the great deposit of natural resource and large investment opportunity, there is the continuous presence of the savings limit, hence, the investment gap (Diouf & Hai, Citation2017; Fasanya & Olayemi, Citation2018). Also, the gaps of foreign exchange increasing rather than closing is an indication of the peculiar characteristics of developing economies like Africa that are usually consuming rather than producing nations, thereby, consistently worsening balance of payments position. This was the position of Fasanya and Olayemi (Citation2018) and Adegboye et al. (Citation2016b) that a boost of export for developing economies is rather expedient, in order to reduce overdependence on foreign exchange. These hence, would result into a better balance of payment position and consequently reduction in the foreign exchange gap.

The research work found that despite the relative increase in FDI, the gaps of investment in the domestic sector has rather widened instead of closing in expectation to theoretical prospects. This is same as the result of Bender and Lowenstein (Citation2005) reporting an indirect association between imported investment and per capita income of the selected economies. In the same vein, an inverse relationship was determined between the foreign inflow of capital and savings in the research work of Nushiwat (Citation2007), Taslim and Weliwita (Citation2000), and Easterly (Citation1999) also stressed that there was no evidence that foreign investment was condition for economic growth or development in the selected economies.

5.1. Conclusion and recommendations

In conclusion, the research work posits that for the African region, the foreign investment inflow has not succeeded in closing the gaps of foreign exchange as well as the investment gaps. Rather, as FDI increased relatively through the examined period, the gaps incessantly remained wider. The study recommends that; the government of developing economies in Africa that welcomes the inflow of external finance should implement it with flow directed to crucial sectors. This would boost industrialization, efficiency and linkages of local firms to aid impactful development of domestic sector. These attainments would encourage exports and discourage imports to enable the countries have better position in the balance of payments. The government should also, through policies of appreciation or depreciation of the countries’ exchange rates, reduce discrepancies in foreign exchange rates. This would bring about tangible progress result for a gradual decline of the foreign exchange gaps.

Acknowledgements

Our acknowledgements go to the authors of the research articles consulted and cited in the course of this study. We also, acknowledge Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Development (CUCRID) for funding the publication of this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Folasade Bosede Adegboye

Folasade Bosede Adegboye (Ph.D.) is a researcher and lecturer in the Banking and Finance Department of Covenant University, with special interest in foreign capital flows, international economics, effects on economic growth and development in Africa.

Tolulope Femi Adesina

Tolulope Femi Adesina (Ph.D.) also, is a researcher and lecturer in the Banking and Finance Department of Covenant University, with special interest in financial development and financial management.

Stephen Aanu Ojeka

Stephen Aanu Ojeka (Ph.D.) currently works at the Accounting Department, Covenant University. Stephen does research in corporate governance, audit committee and accounting technologies.

Victoria Abosede Akinjare

Victoria Abosede Akinjare (Ph.D.) currently works in the Banking and Finance Department as a lecturer and researcher. Her research interest is in real sector finance, small and medium enterprises finance and agricultural finance.

Felicia Omowunmi Olokoyo

Felicia Omowunmi Olokoyo (Ph.D.) is an Associate Professor of Corporate Finance in Covenant University. Her research interest is in Corporate Finance, Banks’ Attitude to Lend and Foreign Direct Investments.

References

- Adegboye, F. B. (2014). Foreign direct investment and economic development: Evidence from selected African countries [Ph.D. Thesis]. Covenant University.

- Adegboye, F. B., Babajide, A. A., & Matthew, O. A. (2016a). The effect of rate of return on investment on inflow of foreign direct investment in Africa. International Business Management, 10(22), 5352–13. https://medwelljournals.com/abstract/?doi=ibm.2016.5352.5357

- Adegboye, F. B., Ojo, J. A. T., & Ogunrinola, I. I. (2016b). Foreign direct investment and industrial performance in Africa. The Social Science, 11(24), 5830–5837. https://medwelljournals.com/abstract/?doi=sscience.2016.5830.5837

- Ahmed, A. D., Cheng, E., & Messinis, G. (2011). The role of exports, FDI and imports in development: Evidence from sub-Saharan African countries. Applied Economics, 43(26), 3719–3731. https://doi.org/10.1080/36841003705303

- Ahmed, K. T., Ghani, G. M., Mohamad, N., & Derus, A. M. (2015). Does inward FDI crowd-out domestic investment? Evidence from Uganda. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 172, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.395

- Amoo, E. O. (2018). Introduction to special edition on Covenant University’s perspectives on Nigeria demography and achievement of SDGs-2030. African Population Studies, 32(1), 3993–3996. https://aps.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/1170

- Bakare Aremu, T. A., & Bashorun, O. T. (2014). The two-gap model and the Nigerian economy; Bridging the gaps with foreign direct investment. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 3(3), 1–14. http://www.ijhssi.org/papers/v3(3)/Version-2/A033201014.pdf

- Baltabaev, B. (2013). FDI and total factor productivity growth: New macro evidence. The World Economy, 37(2): 311–334.

- Bender, D., & Lowenstein, W. (2005). Two-gap models: Post-Keynesian death and neoclassical rebirth (IEE Working Paper No 180). Institute of Development Research and Development Policy, Ruhr University Bochum.

- Blomstrom, M., & Kokko, A. (2003). The economics of foreign direct investment incentives (NBER Working Paper 9489). Retrieved from https://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/redir.pf?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nber.org%2Fpapers%2Fw9489.pdf;h=repec:nbr:nberwo:9489

- Chenery, H. B., & Stout, A. (1966). Foreign assistance and economic development. American Economic Review, 56(4), 679–733. https://www.scirp.org/(S(i43dyn45teexjx455qlt3d2q))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1393458

- Diouf, M., & Hai, Y. L. (2017). The impact of Asian foreign direct investment, trade on Africa’s economic growth. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 3(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015

- Easterly, W. (1999). The ghost of financing gap: Testing the growth model used in international financial institutions. Journal of Development Economics, 60(2), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(99)47-4

- Fasanya, I. O., & Olayemi, I. A. (2018). Balance of payment constrained economic growth in Nigeria: How useful is the Thirlwall’s hypothesis? Future Business Journal, 4(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbj.2018.3.4

- Garcia-Molina, M., & Ruiz-Tavera, J. K. (2009). Thirlwall’s law and the two-gap model: Towards a unified dynamic model. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 32(2), 269290. https://doi.org/10.2753/PKE0160-3477320209

- Heckscher, E. (1919). The effect of foreign trade on the distribution of income. Economisk Tidskrift, 21, 497–512. doi: 10.2307/3437610. https://ideas.repec.org/a/jed/journl/v25y2000i1p75-94.html

- Human Development Reports (2017). United Nations development programme. https://hdr.undp.org/en/data#

- Jaspersen, F. Z., Aylward, A. H., & Knox, A. D. (2000). The effect of risk on private investment: Africa compared with other developing areas. In P. Collier & C. Pattillo (Eds.), Investment and risk in Africa (pp. 71–95). St. Martin’s Press.

- Jones, R. W. (2002). Heckscher-Ohlin trade models for the new century. Chapter 16 In R. Findlay, I Jonung, & M Lundahi. (Ed.), Bertil Ohlin: A centennial celebration (pp. 343–362). MIT Press. A general appraisal of the basic Heckscher-Ohlin approach.

- Jurcic, L., Josic, H., & Josic, M. (2013). Testing Rybczynski’s theorem: An evidence from the selected European transition countries. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(10), 99–105. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n10p99

- Lee, N., & Sami, A. (2019). Trends in private capital flows for low income countries: Good and not-so-good news. (CGD Policy Paper 151). Centre for Global Development.

- Malikane, C., & Chitambara, P. (2017). Foreign direct investment, productivity and the technology gap in African economies. Journal of African Trade, 4(1–2), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joat.2017.11.1

- Nushiwat, M. (2007). Foreign aid to developing countries: Does it crowd-out the recipient countries’ domestic savings? International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 11(11)94–102.

- Ohlin, B. (1933). Interregional and International Trade. Harvard University Press.

- Opp, M. M., Sonnenschein, H. F., & Tombazos, C. G. (2009). Rybczynski’s theorem in the Heckscher–Ohlin world — anything goes. Journal of International Economics, 79(1), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.5.5

- Prasad, E., Rajan, R., & Subramanian, A. (2007). The paradox of capital. Financial Globalization, Finance & Development, 44(1), 16–19. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2007/03/prasad.htm

- Susic, I., Stojanovic-Trivanovic, M., & Susic, M. (2017). Foreign direct investments and their impact on economic development of Bosnia and Herzegovina. IOP Conference Series: Material Science and Engineering, 200, 12019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/200/1/12019

- Szkorupova, Z. (2015). Relationship between foreign direct investment and domestic investment in selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Prodecia Economics and Finance, 23, 1017–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00350-0

- Taslim, M. A., & Weliwita, A. (2000). The inverse relation between saving and aid: An alternative explanation. Journal of Economic Development, 25(1).

- Ullah, I., Shah, M., & Khan, F. U. (2014). Domestic investment, foreign direct investment and economic growth nexus: A case of Pakistan. Economic Research International, 2014, 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/592719

- Workneh, M. A., & Francken, N. (2015). The review of the impact of aid on domestic saving. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. (MPRA Paper No 92174). https://mpra.ub.unimuenchen.de/92174/

- World Development Indicators (2017). The World Bank. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

- Zandile, Z., & Phiri, A. (2019). FDI as a contributing factor to economic growth in Burkina Faso: How true is this? Global Economy Journal, 10(1), 19500004. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2194565919500040