Abstract

Social psychological skill deals with how people understand and predict social psychological phenomena. This skill has been shown to be positively correlated with other parameters such as cognitive reflective ability and introversion. In our study, we examined social psychological skill and its relationship with cognitive reflection ability, language preference, gender, and fear of failure in a sample of undergraduate medical and dentistry students of multiple nationalities at Jordan University of Science and Technology. A questionnaire in Arabic or English language testing participants’ social psychological skill was given to 605 participants. Fear of failing exams was assessed by measuring reported incidence of fears of failing tests in college, and the Bat and Ball problem was assessed to measure cognitive reflection. The results showed that 501 students (82%) opted to answer in their Arabic native language and 61% of total respondents were females. We found that social psychological skill was significantly and positively related to English language preference and cognitive reflection but not significantly related to less fear of failure in college exams. The obtained results are compared to existing data and conclusions are withdrawn.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In the world of psychology, social psychological skill is the ability of understanding and predicting the thoughts and behaviours of others in certain situations and how the actions of the group influence the individual in social interactions. Intelligent and introverted people generally tend to have greater social psychological skill. In our study, we gave the social psychological skill test to college students to search for possible relationships with other factors, such as; anxiety about academic performance, gender, intelligence and the preference for a second language. We discovered that students who were more intelligent and people who preferred answering the questionnaire in a second language had higher social psychological skill. This points towards the idea that the understanding of society and others is facilitated by greater mental ability.

1. Introduction

Social psychological skill (SPS) is defined as “individuals’ skill at accurately predicting social psychological phenomena e.g., how individuals feel, think, and behave in social contexts and situations”. Such a skill has been positively linked to multiple traits and abilities such as intelligence, cognitive reflection, melancholy, introversion and other factors (Gollwitzer & Bargh, Citation2018). Although this ability may seem intuitively universal to humans, however, psychological phenomena often vary across cultures (Gollwitzer & Bargh, Citation2018).

Cognitive reflection captures the cognitive ability to avoid miserly information processing and to think deliberately (Primi et al., Citation2016; Thomson et al., Citation2016). Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) argue that cognitive reflection positively predicts SPS because such reflection allows the individual to suppress cognitive biases which are associated with incorrect assumptions and judgments about people’s social psychological tendencies.

To our best knowledge, Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) were the first to publish a paper on SPS, and ours is the first paper to describe the skill in a different cultural setting.

In this study, we intend to test SPS in a sample of undergraduate medical and dentistry students at Jordan University of Science and Technology. English language proficiency at our medicine and dentistry schools is believed to reflect higher academic status. Students who are more skilled in the English language would obviously prefer taking tests in English. This attitude would be expected to be associated with higher SPS, higher CRT and less fear of failure in college exams.

Moreover, we plan to test whether Jordanian participants’ performance on one item of the cognitive reflection test (CRT), the commonly used Bat and Ball problem, positively predicts their SPS, as has been observed in participants in the United States (Gollwitzer & Bargh, Citation2018).

In addition; we also intend to examine participants’ self-reported fear of failure in college exams, as this parameter may reflect the level of academic achievement. It has been reported that test anxiety is negatively correlated with academic achievement (Cassady & Johnson, Citation2002; Chapell et al., Citation2005). Specifically, we tested whether such fear of failure relates to SPS as well as CRT performance. We predict that more fear of failure will relate inversely with SPS and CRT performance.

Conformity is a classical topic in social psychology (Asch et al., Citation1951). People with higher SPS and CRT show more accurate predictions about social psychological phenomena and have greater cognitive ability (Gollwitzer & Bargh, Citation2018). We also intend to examine if our students can predict conformity in one relevant situation and whether they believe this conformity applies to them. Finally, we are keen to examine whether the predictors of SPS e.g., cognitive reflection. remain constant across different cultures.

2. Objectives

Our objectives in this study are:

To investigate the level of SPS in college students.

To examine the relationship of SPS with CRT, reported fear of failing exams, as well as language effect in college students in a cross-cultural environment.

To present the first cross-cultural investigation of SPS in Jordan.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Our test participants were randomly recruited from medical and dentistry undergraduate students at the Jordan University of Science and Technology. Approval of the Institutional Review Board was obtained. The native tongue of all participants is Arabic; however, English is the primary language of instruction at the university and all students possess an intermediate to high proficiency level in English.

3.2. Procedure

Google Forms were used to distribute the following items:

3.2.1. Social psychological skill

The SPS test part 2 (adopted from Gollwitzer & Bargh, Citation2018) was used. Questions included were, for example:

“Extrinsic motivation (i.e., a monetary reward) is always more powerful than intrinsic motivation (personal feelings of reward)

A) True

B) False”

For the Arabic version of the SPS test, the questions were translated from English to Arabic by the two authors and further adjusted for clarity after receiving feedback from peers. Minor modifications were made -such as alteration of foreign names and removing the “I don’t understand the question” option- but the test material was otherwise identical. The test included 20 SPS items, each item scored 1 point from a total of 20 points. Questions outside the SPS test did not score any points.

The test was distributed through medical and dentistry groups on social media platforms. Participants were informed about the study and were asked to participate if they consent. They chose freely between Arabic and English as a test language. Participants completed the test during a period of 3 days (25th January to 28 January 2018).

3.2.2. Cognitive reflection

Only one out of three questions from the CRT (Frederick, Citation2005) was used to keep the test as short as possible to maintain participant attention and increase compliance: The Bat and Ball problem was used, which reads:

“A bat and a ball cost 1.10. USD

The bat costs 1.00 USD more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?”

(The full version of the test can be found in the supplementary material)

The question and response choices were presented in jordanian currency: [5 piasters -correct-, 10 piasters, 1 dinar, the given information is not enough to answer the question.] When participants answer this question, they most often show a similar pattern of reasoning error, they respond with 10 cents. But a careful analysis shows this to be incorrect because it would mean that the bat costs 1.10 USD (1 + 0.10) and the total becomes 1.20 USD (1.1 + 0.10). This question is surprisingly easy in hindsight, yet, it tends to be mentally challenging at the first exposure. When administered to a large sample of students from highly prestigious universities, many failed to reach the correct answer and instead gave the false heuristic answer of 10 cents (Frederick, Citation2005).

3.2.3. Fear of failure on exams

Participants responded to one item asking: “have you ever entered an exam in university and were afraid to fail? ” responses were [never, once, 2 or 3 times, 4+ times], this served as an indirect measure of academic performance since test-taking anxiety relates inversely to academic performance (Cassady & Johnson, Citation2002; Chapell et al., Citation2005). GPA was avoided because students often do not remember it and do not feel comfortable sharing it.

3.2.4. Conformity judgements

Conformity was addressed by two items in the forums. The first is part of the SPS test and it described a scenario similar to that of Solomon Asch’s experiment (Asch et al., Citation1951) and asked them to predict if most people will conform. The second was an item we added after the first one asking: “In case you were in the situation described in the previous question, what do you think you would do?” options were:

I most probably will not conform

I most probably will conform at least once

This question was not awarded any points for the SPS as it was not part of the original SPS test. In the results and discussion, we highlight some findings about awareness of this concept and the degree to which people make accurate predictions about it. The overall relationship of SPS with CRT will be discussed as well.

4. Results

We recruited 605 students in our study, 501 of which were in Arabic and 104 in English, 61% (n = 369) of the total respondents were females. 254, 119, 199, 16, 11, and 6 of the participants were 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th 5th, and 6th-year college students, respectively.

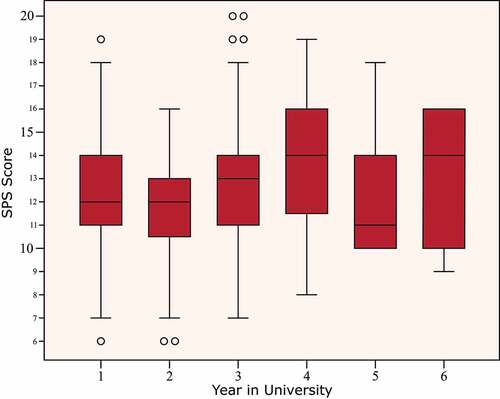

SPS score mean was 12.26 (SD = 2.29) for all participants in both languages (see Table ). Participants scored significantly better on the SPS test than by random chance as shown by a one-sample t-test (M = 12.26 vs. M = 9) (p < 0.001). In consistency with our hypothesis; Test-takers in English scored significantly higher than their Arabic counterparts (M = 12.7, SD = 2.52 vs. M = 12.17, SD = 2.23) (p = 0.031, Cohen’s d = 0.22). There was no significant difference between male and female SPS scores (p = 0.163). Using ANOVA, a significant difference in SPS was found between participants in different years of college education, F(5,599) = 4.347, p < 0.001. Further post hoc testing with Tukey’s honestly significant difference showed that second-year college students were significantly lower in SPS than third and fourth-year college students (p = 0.023, p = 0.003, respectively) and that fourth-year college students were significantly higher than their first-year counterparts (p = 0.014). Figure presents the results on a box and whiskers plot. SPS score in our study was significantly lower than that reported in the USA by Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018), (M = 12.26, SD = 2.29, N = 605 vs M = 12.76, SD = 2.69, N = 133) (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.2). This is the first study to report such a variation in SPS across two different cultural settings.

Table 1. Comparison of SPS Score and Bat and Ball problem Answers Across Arabic and English Respondents

Figure 1. A presentation of education and SPS score relationship

Regarding the CRT Bat and Ball problem, of the 605 test-takers, 42.5% (n = 257) answered correctly (see Table ). Using chi-square analysis, significant gender differences were found, only 38.5% of females answered correctly while 48.7% of males gave the correct answer (p = 0.013). This appears to be consistent with other research showing that males score higher on the CRT than females (Frederick, Citation2005; Thomson et al., Citation2016). However, further analysis showed that the significant difference between males and females was only present in the English test-takers where the correct answer was given by 72% of males and 40% of females (p = 0.001). The difference within the Arabic group was far away from significance (p = 0.29), meaning that males and females performed equally on the Bat and Ball problem while in their native tongues, but males outperformed their female classmates when the test was taken in a foreign language -English-, which resulted in shifting the total outcome towards significance. Students in Arabic and English testing groups also performed differently on the Bat and Ball problem, 55% of English test-takers answered correctly, compared to only 40% of their Arabic test-taker classmates (p < 0.01).

Regarding the relationship between the Bat and Ball problem of the CRT and SPS, Respondents who answered the CRT question correctly scored significantly higher on the SPS compared to the ones who answered incorrectly (M = 12.75, SD = 2.4 vs. M = 11.89, SD = 2.13) (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.37) and this finding was consistent in both languages. These findings replicate those of Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) in a culture outside of the United States. Finally, regarding cognitive reflection and academic achievement, we found that students who correctly answered the Bat and Ball problem reported significantly less fear of failure compared to those who answered incorrectly (p < 0.001). See Table .

Table 2. Comparison of respondents regarding reported fear of exams and bat and ball problem

Finally, regarding the relationship between SPS and fear of failure; Pearson correlation showed no significant relationship between the two (Pearson coefficient = −0.06) (p = 0.097).

On the item requiring participants to predict conformity in a setting similar to that of the famous Solomon Asch’s experiment, 77% of participants predicted that most people would conform. However, in another item asking them to predict their own behaviour, only 18% thought that this phenomenon applies to themselves and that they would conform as well. There was no significant difference in SPS or CRT between participants in regard to what answer they chose (p = 0.222, p = 0.0504; 1 sided).

5. Discussion

SPS is a skill that varies from one person to another, some find certain aspects of psychology easy and intuitive, scoring high on the SPS test with ease, while others lack in such a skill and score lower on the scale. Certain concepts were more easily understood (e.g., 91% of students correctly answered the self-serving bias item) while others were counterintuitive and challenging (e.g., only 8% correctly answered the overjustification effect in cognitive dissonance. And only 37% correctly predicted that catharsis is not effective for anger management). While psychology students are often taught these basic principles, it is reasonable to assume that laypeople may only encounter them in non-academic settings, if at all.

Demographics were not related to SPS according to the original article by Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) except for level of education. We found—as the original article did—that gender did not have an influence on SPS. In regard to education, our sample only included undergraduate medical and dentistry undergraduate, so we expected not to find a statistically significant difference in terms of SPS since the difference in the level of education is minimal. However, the difference was statistically significant, but we could not find a meaningful trend.

English test-takers had significantly higher SPS scores than Arabic test-takers which suggests a systematic difference between the two groups, especially since the tests were presented in an identical manner in both languages. Also, English test-takers performed significantly better on the Bat and Ball problem than Arabic test-takers. This finding may be explained by two factors; first, English test-takers may be more intelligent on average because of better socioeconomic status and educational background which encouraged them to take the test in English. Second, taking the test in English may have resulted in the “foreign language effect” in which thinking in a foreign tongue reduces decision bias and encourages a more deliberative and rational thinking pattern (Keysar et al., Citation2012).

SPS score in our study was significantly lower than that reported in the USA by Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018). This is the first study to report such a variation in SPS across two different cultural settings. This difference can be explained by many factors, one of which is the difference in the sampling of these two studies, our sample included medical and dentistry undergraduates, Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) included a wider range of education and age. Another explanation is that Arabs are more collectivists in terms of their culture than Americans, who are more individualistic (Buda & Elsayed-Elkhouly, Citation1998). This may alter the occurrence of some psychological phenomena that were included as items in the SPS test and was highlighted by Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) as they discussed the possibility that SPS score may be affected by variation in social phenomena across demographics and therefore, some variation in SPS score may not be due to a real difference in SPS, but rather test items that are favourable to Americans. Also, unlike in the United States, psychology is not part of the Jordanian high school curriculum. All these hypotheses are speculative and might act as future research projects in the region. Finally, the removal of attention-check items and “I don’t understand the question” options from our test should be noted as well.

Of the total participants, 42.5% answered the Bat and Ball problem. The gender differences in this question were only observed in the secondary language of the students -English- but not in their native language, we do not have an explanation for this outcome, further research may shed some light.

Participants who answered the Bat and Ball problem correctly scored higher on the SPS test. This finding replicates the findings of Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) in a culture aside from the United States. As hypothesized by Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018), this relationship may be due to higher cognitive reflection being linked to reduced cognitive bias, in turn allowing for greater accuracy at judging social human behaviour (Gollwitzer & Bargh, Citation2018). We also found that participants who answered the Bat and Ball problem correctly reported significantly less fear of failure in college exams, see Table . This was consistent with our predictions and is a novel finding, as to our knowledge, there is no report in the literature on CRT and fear of failure in college tests. The difference between Arabic and English test-takers in CRT was expected. Participants who feel comfortable answering the test in a foreign language are likely more well-educated since English is the language of instruction at Jordan University of Science and Technology.

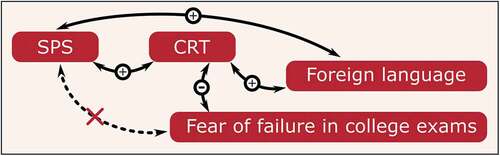

SPS did not correlate to fear of failure on college exams, this is the opposite of what we had predicted and is troubling because the fear of failure was related to CRT while not to SPS. Perhaps a more detailed inventory with more items on fear in exams and additional variables such as neuroticism and resilience to stressful factors could lead to a better understanding of the interplay between these factors. The relationship between these various factors is summarized in Figure .

Figure 2. Relationship between various factors like CRT, SPS, Fear of failure in college exams and Foreign language

The responses to the two conformity items showed that people are usually good at predicting conformity from others but are bad at predicting the same behaviour from themselves. This displays a perfect example of the illusory superiority bias (Headey & Wearing, Citation1988). It is plausible to hypothesize that people with higher SPS score would be more likely to choose that they will conform compared to the other group, given that such people likely have decreased motivational biases. However, the difference was not statistically significant. It is also possible that people higher in SPS and CRT are genuinely less likely to conform than the rest of the population, and if so, this would make their belief of not being conformists a description of reality rather than a delusional sense of superiority. This is a very intriguing possibility and further research is warranted.

6. Limitations

Our study was limited by not including attention check items in the test; however, participants participated willingly in the study and had no reason to answer inattentively. Further, respondents were free to choose between the different forms of the test (i.e., Arabic and English) instead of being assigned randomly; further research with a randomized structure should be conducted to account for possible confounders and biases of self-selection. In our analyses, college students at Jordan were compared to participants recruited by Gollwitzer and Bargh (Citation2018) online from MTurk and it can be argued that these samples are different. Finally, only one question of the CRT was used, this limits its discriminative ability as a continuous variable, however, it still demonstrated a significant ability in predicting less reported fear of failure in college and higher SPS scores.

7. Conclusion

The SPS is a newly introduced aptitude into the psychology literature. Our study shows that it is different across varying cultural settings. We also showed that it is positively related to cognitive reflection ability and English language preference, but not to academic achievement (at least when measured via fear of failure on college exams). We recommend further investigations across different settings and cultures to explore SPS and describe its variation and possible relationships with other domains of cognitive abilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Anton Gollwitzer; Yale University, and Moh'd Zaki Al-Wawi; RAK Medical & Health Sciences University, for their guidance and helpful feedback.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Belal Al Droubi

Belal Al Droubi & Husam Aldean Abuhayyeh are senior medical students at Jordan University of Science and Technology, they have a deep interest in cognitive and social psychology and their possible implications in clinical medicine and healthcare. They are currently active in research projects in medicine and psychology.

References

- Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. Organizational influence processes, 295–303.

- Buda, R., & Elsayed-Elkhouly, S. M. (1998). Cultural differences between Arabs and Americans: Individualism-collectivism revisited. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 29(3), 487–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022198293006

- Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(2), 270–295. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1094

- Chapell, M. S., Blanding, Z. B., Silverstein, M. E., Takahashi, M., Newman, B., Gubi, A., & McCann, N. (2005). Test anxiety and academic performance in undergraduate and graduate students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.268

- Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196732

- Gollwitzer, A., & Bargh, J. A. J. S. P. (2018). Social psychological skill and its correlates. Social Psychology, 49(2), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000332

- Headey, B., & Wearing, A. (1988). The sense of relative superiority—central to well-being. Social Indicators Research, 20(5), 497–516. doi.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03359554

- Keysar, B., Hayakawa, S. L., & An, S. G. (2012). The foreign-language effect: thinking in a foreign tongue reduces decision biases. Psychological Science, 23(6), 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611432178

- Primi, C., Morsanyi, K., Chiesi, F., Donati, M. A., & Hamilton, J. (2016). The development and testing of a new version of the cognitive reflection test applying item response theory (irt). Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 29(5), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1883

- Thomson, K. S., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2016). Investigating an alternate form of the cognitive reflection test. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(1), 99. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2016-09222-009