?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

One of the concerns in improving the quality of minority education in multicultural nations is how to choose the appropriate types of learning for different ethnic groups, especially when such decision can be constrained their cultural diversity. This paper aims to analyze the effect of cultural differences on selecting types of learning for ethnic minorities; thus, recommending some ethic-specific policies to better utilize the manpower resources in the Northwest region of Vietnam. Questionnaires were employed to survey 250 people from 6 ethnic minority groups, whose population is over one million locating in three provinces in the Northwest border region of Vietnam. The study also conducted 20 in-depth interviews with management teams of different educational institutions and corporations. The results show that ethnic-cultural factors including gender, customs, ethnic relations, and marriage age have determined the choice of learning types in higher education levels. From those points, this paper suggests development interventions so that ethnic-cultural factors do not reduce the ability to pursue higher education, increase the unemployment rate of ethic minorities, and cause waste in finance, resources, infrastructure for training in the Northwest region of Vietnam.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper focuses on analyzing the effect of cultural differences on selecting types of learning among ethnic minority groups and recommending some ethic-specific policies to better utilize the manpower resources in the Northwest region of Vietnam. The research employed a mixed methods approach. Specifically, questionnaires were employed to survey 250 people from 6 ethnic minority groups, whose population is over one million. The study also conducted 20 in-depth interviews with management teams of different educational institutions and corporations. The results show that ethnic-cultural factors including gender, customs, ethnic relations, and marriage age, have an influence on the choice of learning types in further education. The paper draws overall message attention to inclusive development, based on the cultural diversity in ethnic culture, to adapt the suitable types of learning for ethnic minorities.

1. Introduction

Fostering the academic attainment of ethnic minorities is one of the sustainable development directions in modern education. Since different minority groups have their own cultural behavior characteristics, taking such differences into consideration will help define approaches to enhance the academic achievement of minority groups. In fact, this has been the concern of policymakers from both developing and developed countries (Ogbu, Citation1983). Comprising 54 ethnic groups, Vietnam is considered one of the countries with high cultural diversity (Committee for Ethnic Minority Affairs, Citation2020). However, the current education program for all of these 54 ethnic groups developed by the Ministry of Education and Training in Vietnam has been facing many obstacles (Ministry of Education and Training [MOET], Citation2017), especially when the culture of each ethnic group plays a decisive role in education results (World Bank, Citation2009). In the Northwest mountainous region of Vietnam, 27 minority groups encompassing 7 distinctive language families (Mong-Dao, Tang-Mien, Viet-Muong, Thai-Kadai, Mon-Khmer, Han-Tang) are living together and create a close-knit multicultural community (Vuong et al., Citation2015). Among them, the Thai, the Mong, the Dao, the Hoa, the Tay, the Nung, etc. have their own verbal and writing form. There are other ethnic groups, such as Kho mu, Lao, Khang, Sila, Mang, etc. who can communicate verbally only. Undeveloped infrastructure caused by the stretch of their residental areas over remoted mountainous terrains has also led to learning barriers.

To solve such issue, many multinational countries including Vietnam consider two choices of education: Core Curriculum education or Multicultural Education (Banks & Banks, Citation2019), each of which has stirred up different debates. On one hand, Bennet (Citation1984), Bloom (Citation2012), Finn (Citation1989), and Hirsch (Citation1988) downgraded the minority cultural diversity and stressed the need of economic and technological advancement instead. Realizing the burgeoning economic growth of countries with Core curriculum Education, they highlighted this education as a one-size-fits-all solution. For a long time, advocates of Core curriculum education built up a hegemony and inadequate representation of dominant culture in the curriculum, aiming to assimilate all students with an one-way approach. This conventional solution, however, has widened the gap of academic attainment between the minority groups and the majority ones. Because of this, proponents for Core Curriculum Education were once called “assimilationists” (Carroll & Schensul, Citation1990). On the other side, Edmonds (Citation1986), Karakara et al. (Citation2019), and Ogbu (Citation1974) assured that addressing cultural diversity in the school can help eradicate the minority education disparities. Unless problems with culturally inclusive development are addressed, minorities may continue to significantly lag behind majorities on all development indicators, and form a permanently disadvantaged class. Such an outcome would be detrimental to long-standing economic development.

Moreover, there are different types of education—namely formal learning, no-formal learning, and informal learning (Cedefop, Citation2000; European Commission, Citation2001)—that governments should consider carefully before deciding the most suitable one for their country. In Vietnam, the formal and non-formal learning are officially applied across the education system for all ethnic groups, in all localities.

Given the multi-ethnic status in Vietnam, although the universal basic education has been delivered as a foundation for social development and economic growth, the Core Curriculum Education is creating a big gap in educational attainment between minority groups and the majority ones. Cultural differences influences the selection of different types of learning, including formal and non-formal. According to Tran and Nguyen (Citation2015), regardless of a huge investment in tangible and intangible resources such as facilities and teacher professional development, insufficient educational policies catering to cultural diversity will to an increase in the unemployment rate among minority groups. At the same time, there is a research gap in analyzing the impacts of cultural diversity on the choice of learning types in the Northwest region of Vietnam.

This study is conducted to clarify the effects of ethnic cultural factors, including (i) beliefs and customs; (ii) livelihoods and knowledge to deal with the environment; (iii)) ethnic relations, gender and marriage; and (iv) social structure of the community, on selecting the types of learning in minority education in Northwest region of Vietnam. The results of this study contributes to help fill the research gap of the choice for learning among ethnic minorities from Vietnam, a developing multinational country in the Southeast Asia. Furthermore, based on the assessment of the correlation between factors, policy implications in organizing effective training for ethnic minority areas according to the Millennium Development Goals (MOET, Citation2017) would be proposed.

2. Literature review

In order to understand the impact of ethnic culture on minority groups’ choice of types of learning, we would clarify the concepts of ethnic culture, and types of learning including both formal and non-formal learning.

2.1. Ethnic culture

The concept of ethnic groups was formerly understood as culture-bearing units consisting of people who share a total “assemblage of cultural traits” (Barth, Citation1969, p 12). However, in the 1930 s, anthropologists began to challenge the idea that the distinctive sets of cultural attributes from ethnic groups adhere (Cam & Phuong, Citation2011). First was Leach (Citation1954), then Moerman (Citation1965) and Keyes (Citation1976). They developed a new formulation of the concept of ethnicity and ethnic groups (Cam & Phuong, Citation2011), and argued that the conventional concept of ethnic groups as strongly procrustean units was “hopelessly inappropriate” (Leach, Citation1954, p. 281). Until now, Keyes’s, (Citation1998) view that ethnic culture is a product of a particular type of cultural practice is widely accepted. According to him, ethnic culture does not limit to a geographical area nor include people from the same origin, share the same language or have the same cultural practices. In fact, it is developed through continuing structural interactions and mutual acceptance among and within ethnic groups.

In Vietnam, due to the influence of the Soviet anthropologist’s approach, the current classification of ethnic groups is based on three criteria: language, ethnic awareness and cultural practices (General Statistical Office [GSO], Citation1979). This approach has ignored the cultural diversity of ethnic groups (Cam & Phuong, Citation2011); thus, unintentionally creating narrow-minded perspective upon the formulation and implementation of affirmative action programs and preferential policies for ethnic minorities living in Vietnam. Considering such paradox in mind, in this study, we decided to use Keyes’s (Citation1998) conceptual framework to assert the cultural diversity of difference ethic groups upon selecting the types of learning for minorities in the Northwest region of Vietnam.

2.2. Formal, non-formal learning

According to Cedefop (Citation2000), Colardyn and Bjornavold (Citation2004) and the European Commission (Citation2001), there are three types of learning, namely formal, non-formal and informal learning. Specifically, formal learning is the learning that occurs within an organized and structured context (formal education, in-company training), and that is designed as learning. It may lead to a formal recognition (diploma, certificate). Formal learning is intentional from the learner’s perspective. Non-formal learning relates to learning embedded in planned activities that are not explicitly designated as learning, but which contain an important learning element. Non-formal learning is intentional from the learner’s point of view. Informal learning consists of the learning that results from daily life activities related to work, family or leisure. It is not structured and typically does not lead to certification. Informal learning may be intentional but in most cases it is non-intentional.

This classification was first applied in the education system of some European countries in the 2000 s, and is still a standard for education classification in the education system there (Colardyn & Bjornavold, Citation2004). Some countries known for developing the best education systems—such as the United States, Australia, Japan, and Singapore—are also applying this learning classification.

In this research, we would focus on types of learning in higher education only. According to the Law on Higher Education (MOET, Citation2012), the levels of higher education in Vietnam are provided in two forms including: (1) Formal education: full-time courses are provided at higher education institutions in order to implement a training program at a certain level of higher education; (2) Continuing education: including in-service training and distance learning in which the classes and courses are provided at higher education institutions or associate education facilities depending on the students’ demand in order to implement a college or university training program.

Many studies have shown the impact of different factors on the learning process of higher education in both developed and developing countries. These factors include: confidence (Lohman, Citation2006); interest in progression (Berg & Chyung, Citation2008; Lohman, Citation2006); endurance for changing (Eraut, Citation2004; Skule, Citation2004); previous experience (Marsick et al., Citation1999; Tewari & Ilesanmi, Citation2020); climates of collaboration, sharing, and trust (Lohman, Citation2006; Marsick et al., Citation1999); feedback of people (Berg & Chyung, Citation2008; Jeon & Kim, Citation2012; Lohman, Citation2006); and supervisor’s support and encouragement (Lohman, Citation2006; Marsick et al., Citation1999; Skule, Citation2004; Tewari & Ilesanmi, Citation2020). Among these factors, Ellinger (Citation2005) and Reardon (Citation2010) were especially interested in learning culture, and considered it as a vital one in the learning process. However, despite such diverse ethnic groups, Vietnam has not taken into account cultural attributes while implementing a labor training program in higher education. Therefore, this study aims to clarify the influence of ethnic culture on the choice of higher education: formal education and continuing education.

Different research methods have been used to assess the impact of cultural factors on the choice of learning types of different ethnic minority groups. There are the use of secondary materials, through looking up research results published in journals, chapters, and dissertations, and qualitative research of “voluntary and involuntary minorities” groups over a long time (Ogbu & Simons, Citation1998). However, there are very few studies using both qualitative and quantitative simultaneously to assess the influence of culture on the choice of learning types among ethnic minorities from the perspective of all three skateholders: educators, policymakers, employers and students.

3. Methods

Mixed methods were used in this study to maximize the amount of information about ethnic minority groups living in the Northwest region of Vietnam collected. Unlike other common implementation of mixed method models (Haverland & Yanow, Citation2012; Mertens & Hesse‐Biber, Citation2013), this study tries to fill the gap about analyzing qualitative and quantitative data separately so that the study can create mutual validation of the data and a more coherent and complete picture of the investigated domain (Creswell & Clark, Citation2011; Kelle, Citation2006; Teddlie & Tashakkori, Citation2003). Any unknown explaining variables, incomprehensible statistical findings or misspecified models encountered during the quantitative analysis process will be compensated by the qualitative method in the forms of in-depth interviews.

We used data from a survey conducted in 2015–2016 and have been formally defended in front of the Vietnamese Council of the Committee for Ethnic Minority Affairs in 2017. Up to 2016, this was the first survey assessing the influence of ethnic culture on the decision of choosing learning types of ethnic minorities in the Northwest of Vietnam. The interviews were scientifically based and therefore reasonably self-assessing according to the criteria outlined in scientific rigor and its impact on local training effectiveness.

This study was conducted in multi-ethnic provinces, whose higher education (after high schools) still confronts many difficulties. The ethnic minority groups in these provinces also represent ethnic minorities living in mountainous areas in Vietnam. Three out of the four provinces were surveyed. Ethical considerations were concerned during the process of data collection and data analysis. All the interviewees were informed about the purpose of the research and that all the information they provided would be anonymous.

For quantitative research, Anket questionnaires were used to collect information about ethic minority students who are participating in either universities, colleges or vocational training schools. These institutions must have at least 50% of students being ethnic minorities. These participants also must represent different ethnic minority groups (Tay-Thai group, Mong-Dao group, Han-Tang group, Ka Dai group, etc.). The survey includes the following topics: (1) their current choice of learning type; (2) ethnic cultural factors influencing their choice; (3) level of satisfaction, and reasons for dissatisfaction for the current learning type; (4) their own desire for choosing the right types of learning. In total, there are 250 out of 400 questionnaires submitted, which is equivalent to the participation rate of 62.5%.

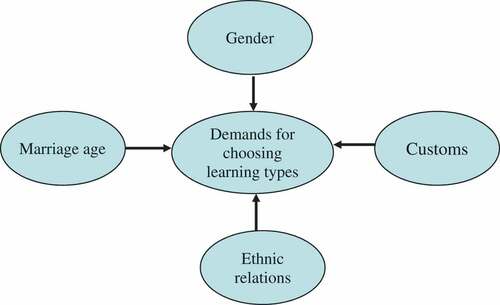

In addition, different assumed factors influencing the choice of learning types among ethnic minority students in Northwest region of Vietnam are shown in the following figure.

There are different assumed factors—such as gender (G), customs (C), ethnic relations (ER), and marriage age (MA). They all impose influences, to a certain extent, on the need of choosing either formal or continuing education of 500 participants who are studying in universities, colleges or vocational schools in the Northwest region of Vietnam.

For each dependent variable, this study has different coding of questions in order to diversify the information, handle variables that have abstract connotations such as customs or ethnic relations. On the other hand, the qualitative variable “gender” will only have two options: “male” or “female”, whereas the third answer for LGBT people is excluded due to cultural appropriateness with the community.

The dependent variable “Customs” includes different observed variables, namely food (F), clothes (Cl), distance of residence (Dis), rituals (Ri), ethnic festivities (EFes), and customary law (Cuslaw). In this study, six assumptions related to the dependent variable “Customs” were made. There are: (1) cuisine differences of where the institutions are taken plance affects minorities in choosing their forms of education; (2) since ethnic minorities may not be able to get used to wearing their ethnic attire in formal educational settings, they opt for non-formal learning; (3) due to the geographical distance between home and formal learning institutions, ethnic minorities do not want to participate there; (4) ethnic rituals take too much time that ethnic minorities do not want to participate in formal education; (5) ethnic minorities prefer attending ethnic festivals than learning in formal education; (6) ethnic minorities may be bound by their customary law; thus, reluctant to participate in formal education.

In order to verify the reliability of the scales, 50 pilot questionnaires were verified by the measurement formula using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient (α = Nρ/[1 + ρ (N-1)]. As can be seen from Table , the observed variables that need to be removed are Food (F) and Clothes (Cl) because their test results were not >0.3, although the Cronback’s Alpha if item-Deleted coefficient of Food was 0.612. and of the Clothes is 0.639.

Table 1. Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of the factors in the dependent variable “Customs”

To further examine the interrelationships between variables at all different factors in order to detect observed variables that have multiple factors or are benevolently differentiated from the outset, we further employ exploratory factor analysis. The results show that the KMO coefficient reaches 0.832, satisfying the condition 0.5 ≤ KMO ≤ 1, which means that the factor analysis is accepted within the research data set. Sig Barlett’s Test = 0.000 < 0.05 also further strengthen the appropriateness of factor analysis. Newly emerging factors include X1, X2, D5, D6.

The survey results were processed on the software SPSS 24.0. Linear regression model is used to calculate the impact level of the factors … … …. The analytical model has the form of:

In which:

The dependent variable Y is the choice of learning types.

B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6 are standard Beta coefficients in the multivariate regression equation.

X1, X2, X3 are new factors after the exploratory factor analysis.

The multivariate regression equation in this study did not use the standard regression equation because only one independent variable “Customs” was changed while other independent variables remained the same.

Qualitative research was conducted in the form of in-depth interviews with the following subjects: (1) representatives of vocational training schools in researched areas; (2) representatives of universities/colleges in researched areas; (3) ethnic minority students learning at universities/colleges in researched areas; and (4) ethnic minority students learning at vocational training schools in researched areas. The questionnaire in qualitative research is designed to include all open questions. Questions explore holistic information about the needs and types of learning for ethnic minorities in researched areas. In-depth interviews were conducted for at least 40 minutes. In total, 12 interviews were carried out, then manually transcripted.

For this study, the representativeness of the total variables of universities/colleges/vocational schools is based on local characteristics. The Northwest region of Vietnam comprises four provinces, of which there is only one university. In the remaining provinces, each has a college and a vocational training school. During the research period, the number of ethnic minority students attending school for over 2 years always accounted for 50% of the total population. There are no private or enterprise-sponsored schools in the Northwest region of Vietnam. The sex ratio in the questionnaire generated by population/sample for men was 68.1%/67.4% and for women was 31.9%/32.6%. Therefore, we conclude that the sample is representative. This is very important for the generality of our research results. The results are statistically significant to infer that the relationships we discovered in this article also refer to the total population.

4. Results

The paper uses the ordinary least squares method to estimate the linear regression model; thus, identifying the cultural factors that affect the choice of training type of ethnic minorities. Estimated results are presented in Table .

Table 2. Estimated results

The estimation results show that the model has a very high significance (>1%) and many cultural factors affects the choice of ethnic minority students about learning types. At the same time, the model also explained 45.21% of the variation of the independent variable to the dependent variables.

The GENDER variable reaches a positive value of 1.478, which shows that gender has a strong influence on the selection of learning types among ethnic minority students. According to our observation, most of the girls tend to choose non-formal training because they thought that formal education will hinder their marriage, or that “Girls don’t need a higher education” (Interviewee, female, 20 years old, DHTB, 2015). Many girls had the patriarchal culture that devalues female education“Girls just need to get married, have children, stay home to cook and take care of the children. If taking formal education, we may find it hard to find love and get married” (Interviewee, female, 23 years old, CĐĐĐB, 2015). As a result, most of the female participants chose non-formal learning (77% of women) over formal learning (23% of women).

In contrast, men tend to prefer formal education because they think that “learning can change their lives, giving them a chance to work in government agencies or businesses” (Interviewee, male, 22 years old, TBTB, 2015, ethnicity … .). This informant further said that “in the future, as the breadwinner of the family, I need to earn money to support my wife and children so studying in formal education would provide a better chance than other courses. You know, in Vietnam, degrees from formal education are considered more valuable than continuing education.”

The variable CUSTOMS is thought to have the highest level of influence on the choice of learning type of ethnic minorities living in Northwest Vietnam (2,001 ***). There are various manifestations of customs and practices, including some basic features such as eating, dressing, worship, beliefs, regulations on festival organization, rituals, laws about wedding organization, and laws on natural protection. Regarding the choice of learning types, the most powerful factor interrupting the learning process in formal education is rituals as students must comply with such (76% of respondents had answers related to this content). For example, the Dao Do ethnic group living in the Northwest of Vietnam has the custom of celebrating maturation ceremonies for men when they reach adulthood. The “right” date and time for the ceremony of maturation depends entirely on the decision of a “shaman”; thus, it is not fixed. If boys are announced about the right time to take part in the ceremony, they must give up everything, even in the middle of the exam, and immediately go back home to conduct the ceremony. This greatly affects the ability of boys to maintain their study in formal education. Take the Mong ethic group as an another example.”Our Mong New Year festival, which is different from Lunar New Year, takes place in the first month. During that time, we have to leave school to go back home and join the family gathering.” (Interviewee, male, 22 years old, CĐBB, 2016). From the findings, we can conclude that both men and women are equally affected by this variable.

The variable ETHNIC RELATIONS also has a relatively high positive coefficient β of 1,840 ***, confirming that people who are in the same ethnic relations are more likely to have a similar choice of learning types. This is reasonable since most ethnic groups in Vietnam, with similar backgrounds, would make the same choices in similar circumstances. Common characteristics of anthropology, language group, and cultural practice leads to cultural “empathy” and the tendency to form similar “common sense” groups. In Vietnam, this is understandable for minority groups in a multi-ethnic country with a developing economy. However, for developed countries, there seem to be opposite views. We will examine this in a later section.

The variable MARRIAGE AGE or, to be exact, the “early marriage” has the highest impact on whether students choose formal or non-formal learning. Most young people of ethnic minority groups get married much earlier than young people of dominant groups. One informant noted:

The Mong students at my school usually “catch wives” at the age of 14-15. According to Mong’s customs, at that age, a boy has the right to “catch” his own wife and live together without having to notify their parents. If appropriate, they will report to the family to get married; otherwise, they will just break up. In many cases, girls have to drop out of school due to being “caught” to be wives when they have not reached the age of marriage. (Interviewee, Manager of DHTS, 2016)

5. Discussion

The evaluation of the role of culture in learning outcomes in developed countries has been done by many researchers since the 1960 s and 1970 s. Ogbu studied the cultural and linguistic differences between white students with black groups from Africa and yellow groups from China, Vietnam, and Japan differences (Ogbu, Citation1995a). Edmonds (Citation1986), Ogbu (Citation1974), and Passow (Citation1984) have also studied different student groups at prestigious universities in the United States. Scholars have shown that culture is an important factor in choosing the type of learning for groups of students from different countries. The findings in the current research argue that culture has great influences on the learning viewpoints of citizens in developing countries. Specifically, this study confirms that ethnic culture plays an important role in choosing the learning types for ethnic minority groups in Vietnam.

First of all, gender has different levels of impact on the choice of learning types depending on the context. In this study, the variable GENDER has a strong impact, which is different from the study of Ogbu (Citation1995b) about black or yellow groups specifically represented by African-Americans and Chinese-Americans. In his study, with the setting in a developed country like the United States, men and women almost had no gap in access to different types of learning. In fact, they are relatively equal in their decisions regarding types of learning. The only barriers for them to participate in different types of learning are related to race, skin color, and religion. Additionally, Cheteni et al. (Citation2019) argue that people in the rural and traditional areas were literate regardless of both gender and race. In contrast, those factors are not the case in Vietnam. Although ethnic minorities in Vietnam have no conflict in religious beliefs as well as race, cultural norms continue to place ethnic minority women in a subordinate position in many communities, and minority women continue to be disadvantaged in all respects. Specifically, women have to do more work, are less likely to involve in community activities including learning, and choosing learning types for further education. Patriarchal minority traditions also perceive men as the ones who must have the responsibility to study and get a job so that they can support their family. This finding is consistent with Gabriel et al.’s (Citation2020) study that women of indigenous communities have inadequate access to resources, education, and sources of income.

Next, customs are an important factor leading to the decision of choosing the types of learning of ethnic minorities living in the Northwest region of Vietnam. The studies of Cameron (2001), Edmonds (Citation1986), Ogbu (Citation1974), and Passow (Citation1984) show that when grouping minority groups with majority ones, the culture of the former does not influence the choice of learning types. While the studies of these educational anthropologists referred to foreign students from Africa and Europe who come to the United States to study and contribute to the cultural differences there, the current research in Vietnam does not share the same context. Obviously, international students from different nationalities come to the United States to study with financial stability, a certain academic background, and a deep sense of cultural readiness to adapt to a new life in a new country. However, ethnic minority students participating in vocational or higher education in the Northwest region of Vietnam do not have such advantages. They face food insecurity in the middle of the crops and the lack of labor resources when their hometown come to harvest. These ethnic groups are also strongly influenced by the cultural references in their community. They always need to remember that they will be urged to stop studying for a long time to fulfill their “responsibilities” or to satisfy their “cultural needs”.

Additionally, ethnic relation affects the choice of learning types among young people. According to Banton (Citation2008), members in an ethnic group share many common factors including language, religion, politics and the feelings of attraction and repulsion generated by beliefs about blood relationships. In other words, people in one ethnic relation have many connections between everyday interactions, which enables them to combine in the pursuit of shared ends (Batur & Feagin, Citation2018). In addition, with ethnic, individual members have “feelings of ethnic belonging and pride, a secure sense of group membership, and positive attitudes toward one’s ethnic group” (Phinney & Alipuria, Citation1996, p. 142). In this study, informants belonging to the same ethnic minority group share similar choice in learning types. This finding confirms Gushue’s (Citation2006) study that culture has an influence on the kinds of learning experiences to which a young person has access or is encouraged to seek.

Last but not least, marriage age also has influences on young people’s learning decision. Most of the research on the cultural factors affecting the choice of learning types have been undertaken in countries whose economy is developed and the marriage of young people is less restricted by social prejudices and customs (Batabyal, Citation2003). In developed countries, the sense of marriage is much more personal. The marriage is mainly decided by individuals, instead of family and community. In contrast, early and teenage marriage is quite common in developing countries (Anukriti & Dasgupta, Citation2017). This echoes the study finding that the marriage decisions of young couples in ethnic groups in the Northwest region of Vietnam are strongly influenced by family and community. Most of the ethnic minorities here get married earlier than the regulations of the Vietnamese Government. However, they do not feel guilty because they have been accepted or urged by their relatives and the community. Therefore, their pursuit of formal learning in higher education will automatically become postponed.

6. Conclusions

The Government of Vietnam has already made great strides to address some disparities between ethnic minority groups and the majority of ones in recent years. The proposed solutions are in many aspects including finance, health care, education, culture, and environment. However, at present, the quality of education in ethnic minority areas in Vietnam is much lower than in other regions. This creates a huge waste of finance, resources and infrastructure for training Vietnamese ethnic minority groups. As long as minority education disparities remain, the poor economic growth is likely to persist. The Government of Vietnam has promulgated and implemented several policies such as adding scores, reducing tuition fees, and awarding scholarships to encourage ethnic minority students to participate in higher education. However, the enrollment rates have still been low and the learning process can be hindered easily. This study shows that one of the important impacts leading to this issue is the influence of ethnic minority culture. Therefore, this article draws overall message attention to inclusive development, based on the cultural diversity in ethnic culture, to adapt the suitable types of learning for ethnic minorities.

While Vietnam is still facing many obstacles in creating an equative and inclusive education, especially for ethnic minorities living in areas with difficult living conditions, the results of this study change the perception of organizing the existing types of learning. Culture is a factor that has a great influence on the choice of learning types in higher education levels among ethnic minorities in the Northwest of Vietnam. Specifically, these cultural factors include gender, customs, ethnic relations, and marriage. The findings of the current research can be applied in areas where there are many ethnic minorities living in highly concentrated areas and with culturally diverse identities. Consequently, we encourage the continuation of research on the influence of ethnic minority culture in other regions such as the Central Highlands and the Southwest to triangulate the research findings.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Trang Thu Nguyen

Dr. Trang Thu Nguyen is a lecturer at the Vietnam Academy for Ethnic Minorities. Her research interests are cultural anthropology and educational anthropology.

Trung Tran

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Trung Tran is the Director of the Vietnam Academy for Ethnic Minorities, and is the leader of the Vietnamese Science Editors (VSE) Team.

Loc My Thi Nguyen

Prof. Dr. Loc My Thi Nguyen works at the Vietnam National University, Hanoi. She is the Chairwoman of the Vietnamese State Council for Professorship in Education.

Thuan Van Pham

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Thuan Van Pham is Vice Rector of the VNU University of Education, Vietnam National University, Hanoi.

Tram Phuong Thuy Nguyen

Dr. Tram Phuong Thuy Nguyen is a visiting researcher at the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Research of Duy Tan University, Vietnam.

Hieu Trung Pham

MSc. Hieu Trung Pham is working at the Department of Personnel and Organization, Ministry of Public Security, Vietnam.

Binh Duc Pham

Dr. Binh Duc Pham is a lecturer at the University of Science and Technology of Hanoi, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology.

References

- Anukriti, S., & Dasgupta, S. (2017). Marriage markets in developing countries. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics. http://ftp.iza.org/dp10556.pdf

- Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. M. (Eds.). (2019). Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (10th ed.). Wiley.

- Banton, M. (2008). The sociology of ethnic relations. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(7), 1267–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701710922

- Barth, F. (1969). Ethnic groups and boundaries: The social organization of cultural difference. Long Grove: Waveland Press.

- Batabyal, A. A. (2003). Decision making in arranged marriages with a stochastic reservation quality level. Applied Mathematics Letters, 16(2003), 933–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0893-9659(03)90019X

- Batur, P., & Feagin, J. R. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of the sociology of racial and ethnic relations. Springer.

- Bennet, W. J. (1984). To reclaim a legacy: A report on the humanities in higher education. National Endowment for the Humanities.

- Berg, S. A., & Chyung, S. Y. (2008). Factors that influence informal learning in the workplace. Journal of Workplace Learning, 20(4), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620810871097

- Bloom, A. (2012). The closing of the American mind: How higher education has failed democracy and impoverished the souls of today’s students. Simon & Schuster.

- Cam, H., & Phuong, P. Q. (2011). Diễn ngôn, chính sách và sự biến đổi văn hóa – Sinh kế tộc người [Speech, policy, and changes in cutlure and ethnical livelihood]. World Publishing House.

- Carroll, T. G., & Schensul, J. J. (1990). Cultural diversity and American education: Visions of the future. Education and Urban Society, 22(4), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124590022004002

- Cedefop. (2000). Making learning visible: Identification, assessment and recognition of non-formal learning in Europe. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/3013

- Cheteni, P., Khamfula, Y., Mah, G., & Casadevall, S. R. (2019). Gender and poverty in South African rural areas. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1586080. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1586080

- Colardyn, D., & Bjornavold, J. (2004). Validation of formal, non‐formal and informal learning: Policy and practices in EU member states. European Journal of Education, 39(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0141-8211.2004.00167.x

- Committee for Ethnic Minority Affairs. (2020). Welcome to CEMA. http://english.ubdt.gov.vn/home.htm

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. P. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Edmonds, R. (1986). Characteristics of effective schools. In U. Neisser (Ed.), The school achievement of minority children: New perspectives (pp. 93–104). Erlbaum.

- Ellinger, A. D. (2005). Contextual factors influencing informal learning in a workplace setting: The case of “reinventing itself company”. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16(3), 389–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1145

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/158037042000225245

- European Commission. (2001). Making a European area of lifelong learning a reality. Communication from the Commission. http://aei.pitt.edu/42878/1/com2001_0678.pdf

- Finn, C. E. (1989). Norms for the nation’s schools. The Washington Post, B7.

- Gabriel, A. G., De Vera, M., & Antonio, M. A. B. (2020). Roles of indigenous women in forest conservation: A comparative analysis of two indigenous communities in the Philippines. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1720564. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1720564

- GSO. (1979). Decision No.121-TCTK/PPCĐ on 02, March, 1979. General Statistical Office.

- Gushue, G. V. (2006). The relationship of ethnic identity, career decision-making self-efficacy and outcome expectations among Latino/a high school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2006), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.03.002

- Haverland, M., & Yanow, D. (2012). A hitchhiker’s guide to the public administration research universe: Surviving conversations on methodologies and methods. Public Administration Review, 72(3), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02524.x

- Hirsch, E. D. (1988). Cultural literacy: What every American needs to know. Vintage.

- Jeon, K. S., & Kim, K. N. (2012). How do organizational and task factors influence informal learning in the workplace? Human Resource Development International, 15(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2011.647463

- Karakara, A. A., Osabuohien, E. S., & Chen, L. (2019). Households’ ICT access and educational vulnerability of children in Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1701877. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1701877

- Kelle, U. (2006). Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in research practice: Purposes and advantages. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(4), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478088706070839

- Keyes, C. F. (1976). Towards a new formulation of the concept of ethnic group. Ethnicity, 3(3), 202–213.

- Keyes, C. F. (1998). Ethnicity, ethnic group. In T. Barfield (Ed.), The dictionary of anthropology (pp. 152–154). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Leach, E. R. (1954). Political systems of Highland Burma. Harvard University Press.

- Lohman, M. C. (2006). Factors influencing teachers’ engagement in informal learning activities. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654577

- Marsick, V. J., Volpe, M., & Watkins, K. E. (1999). Theory and practice of informal learning in the knowledge era. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 1(3), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/152342239900100309

- Mertens, D. M., & Hesse‐Biber, S. (2013). Mixed methods and credibility of evidence in evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, (2013(138), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20053

- Ministry of Education and Training (MOET). (2012). Higher education law. National Assembly.

- Ministry of Education and Training (MOET). (2017). Bo Giao duc va Dao tao voi viec thuc hien Nghi quyet so 05/2011/NDCP ve cong tac dan toc [MOET with the implementation of the Decree No. 05/2011/NDCP on ethnic minority programs]. https://moet.gov.vn/giaoducquocdan/giao-duc-dan-toc/Pages/Default.aspx?ItemID=4611

- Moerman, M. (1965). Ethnic identification in a complex civilization: Who are the Lue? American Anthropologist, 67(5), 1215–1230. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1965.67.5.02a00070

- Ogbu, J. U. (1974). The next generation: An ethnography of education in an urban neighborhood. Academic Press.

- Ogbu, J. U. (1983). Minority status and schooling in plural societies. Comparative Education Review, 27(2), 168–190. https://doi.org/10.1086/446366

- Ogbu, J. U. (1995a). Cultural problems in minority education: Their interpretations and consequences—Part one: Theoretical background. The Urban Review, 27(3), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02354397

- Ogbu, J. U. (1995b). Cultural problems in minority education: Their interpretations and consequences—Part two: Case studies. The Urban Review, 27(4), 271–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02354409

- Ogbu, J. U., & Simons, H. D. (1998). Voluntary and involuntary minorities: A cultural-ecological theory of school performance with some implications for education. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 29(2), 155–188. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.1998.29.2.155

- Passow, A. H. (1984). Equity and excellence: Confronting the dilemmas[Paper presentation]. First International Conference on Education in the 1990s, Tel Aviv, Israel.

- Phinney, J. S., & Alipuria, L. L. (1996). At the interface of cultures: Multiethnic/multiracial high school and college students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 136(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1996.9713988

- Reardon, R. F. (2010). The impact of learning culture on worker response to new technology. Journal of Workplace Learning, 22(4), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621011040662

- Skule, S. (2004). Learning conditions at work: A framework to understand and assess informal learning in the workplace. International Journal of Training and Development, 8(1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-3736.2004.00192.x

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2003). Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In C. Teddlie & A. Tashakkori (Eds.), Sage Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 3–50). Sage.

- Tewari, D. D., & Ilesanmi, K. D. (2020). Teaching and learning interaction in South Africa’s higher education: Some weak links. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1740519. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1740519

- Tran, T., Nguyen, T. T., & Trinh, P. T. (2015). Situation of ethnic minority human resources and some recommendations for developing high quality human resources in ethnic minority areas. Journal of Education Science, 121(10), 58-60.

- Vuong, X. T., Bui, X. D., & Ta, T. T. (2015). Các dân tộc ở Việt Nam [Ethnic groups in Vietnam]. National Politics.

- World Bank. (2009). Country social analysis: Ethnicity and development in Vietnam: Summary report (English). World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/331741468124474580/Summary-report