Abstract

In the wake of active shooting, the commonly cited “See Something, Say Something” campaign is, by and large, ineffective, not because it lacks good intent. Rather, it fails insofar as it does not give the public clear criteria of what to see, what to say, to whom to say it and when. Terrorists and other types of armed assailants wishing to use violence, wreaking out death and destruction for political or personal ends, do not suddenly launch an attack. Prior to each attack, the could-be armed assailant does extensive research, And, even prior to deciding on becoming an armed assailant, the could-be armed assailant broadcasts clear and recognizable signals. While not predictable, active shootings are foreseeable. After debunking four popular myths, the article identifies a pyramid of five phases which the could-be armed assailant ascends and the respective indicators. The article concludes by discussing a proposed risk model and means by which to reduce that risk, not the least of which is an effective awareness and reporting program incorporating among others human resource personnel, psychologists, social workers and naturally law enforcement officials designed to mitigate the risk a could-be armed assailant ascend the pyramid. It ultimately challenges scholars in the fields of Psychology, Sociology, and Political Science to explore the underlying reasons which explain and thereby confront the underlying triggers which inspire could-be armed assailants to move toward the apex of the pyramid. But more it calls for raising the awareness of those who witness the broadcasts.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Orlando, Paris, Las Vegas, Manchester. Once these cities were places people associated with fun, glamour, and relaxation. Today, these cities are places where the “inexplicable” occurred as a seemingly normal person callously took the lives of countless innocents. But were these events truly inexplicable and what made a person, who could have been our neighbor, suddenly wreak become an armed assailant wreaking out death? Based on a survey of recent armed assailant incidents, this article maintains armed assailants do not suddenly appear; they develop gradually, frequently in full view of their family, neighbors, and coworkers. More importantly, it describes key characteristics which a potential armed assailant exhibits months prior to the individual launching the attack. Finally, it lays out a risk mitigation model for venues, be it a restaurant, school or concert hall, which owners and managers which can use.

“A strong man with homicidal and religious mania at once might be dangerous. The combination is a dreadful one.” Brom Stroker, Dracula.

1. Introduction

Heinous shootings, formerly referred to as insider attacks but now more broadly categorized as “active shooters,” have rocked US society. Active shooters are not a new phenomenon. Only hearken back to the old phrase coined in the 1970’s and 1980’s, “going postal” or to the event in the 1970’s which inspired “I Don’t Like Mondays,” by The Police and realize active shooters are not a new phenomenon.

What does seem novel, where in the past active shooter incidents seemed largely confined to the workplace, today the threat seems to be to any venue, where large numbers of people congregate. Consequently, be they shootings in our schools, our workplaces, or in our public venues, the threat of active shooters seems pervasive. And, far worse, the general view is there is nothing the general public can do to preclude itself from having the misfortune of being at a venue where an active shooter releases his or her madness.

Policymakers focus on limiting individuals’ rights to own automatic weapons. Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies at all levels dedicate significant effort to educating the public on how to react when an armed assailant becomes active, namely at the point in the cycle when the armed assailant enters the target area and begins to wreak death and mayhem on his unsuspecting victims. However, educating the public and, for that matter, security personnel at that point is far too late. Sadly, the perpetrator has already largely succeeded in his venture. At that point, the venue owner, program sponsor, etc. are left only then with caring for the wounded, mourning the dead, and, in the best circumstance, analyzing deficiencies in order to prevent another such incident in the future.

By and large, the “See Something, Say Something” campaign is ineffective not because it lacks good intent. It fails insofar because it does not give the public clear criteria of what to see, what to say, to whom to say it and when. Terrorists and other types of armed assailants wishing to use violence, wreaking out death and destruction for political or personal ends, do not suddenly launch an attack. Prior to each attack, the could-be armed assailant does extensive research, seeking out the ideal target, time, and methods. And, even prior to deciding on becoming an armed assailant, the could-be armed assailant broadcasts clear and recognizable signals, especially noticeable to friends, family, co-workers, and on occasion, random strangers.

While not predictable, active shootings are foreseeable if the public recognizes the indicators in advance and communicates those indicators to those who can take preventative or remedial actions, be it to medical or law enforcement professionals. In the wake of the Parkland shootings, newspaper articles contained numerous accounts of individuals stating they suspected the perpetrator was not behaving normally and likely posed a threat to himself or others. Anecdotes aside, recent studies indicate 93% of shooters displayed behaviors that concerned others. And at least one person knew the shooter was planning an attack in 80% of the cases. (Rossi, Citation2018)

The statistics for workplace shootings as well as other types of active-shooter events may not be that dissimilar. The Mandalay Bay rifleman, the Orlando night-club shooter, the Brussels bombers, Dylan Roof, and Anders Breivik, the ultra-right fanatic who massacred Norwegian young students at Norwegian island summer camp, all broadcast clear signals of their intent and followed set patterns prior to conducting their attacks. Whether the motivation comes from unconventional interpretations of religious beliefs, ultra-rightist, ultra-leftist, nationalist political views, or pure socio-pathetic urges, the armed assailant does not suddenly materialize; he has lived, worked and played among us. And, unfortunately, his success hinges as much on our lack of knowledge, our belief in others’ innate goodness, and our associated reluctance to report odd behaviors as on the active shooter’s own imperative to maintain the secrecy of his plans and the security of his operation so necessary to implement his surprise attack.

Publicly available studies on active shooters, to include those by the FBI, largely categorize “workplace shootings,” “school shootings,” and ideologically inspired shootings into discreet categories. They treat a workplace shooter as distinct phenomenon from a religiously inspired shooter. Generally, the perpetrators’ motivations, at least those expressed, may be different. However, the general traits of an active shooter and the indicators of a potential active shooter are quite similar.

This article hopes to fill a void. First, it combines the results of publicly available studies on all types of active shooters and distills the commonalities. Second, it aims to inform non-practitioners of the indicators which they can use to identify an active shooter before he actually begins his or her attack.

It is not necessarily intended for the law enforcement community but more for the general public, specifically venue owners, their employees, and their patrons. Law enforcement has both limited jurisdiction but more critically fewer resources in detecting an armed assailant in the early stages. The general public is legion and sees far more. Each armed assailant consciously or unconsciously operates according to a discernable cycle and exhibits recognizable pre-attack behaviors, which, if reported to the proper professionals, can markedly reduce the likelihood of success.Footnote1 More importantly, businesses can use the knowledge of these indicators to implement security measures to decrease their vulnerabilities, thereby making themselves a less attractive target for an attack.

2. Debunking popular myths

Myth 1: Armed assailant attacks are unpredictable and unforeseen. While the percentages vary, there is an overall consensus that armed assailants emit indicators and warnings of their intent. Studies of successful attacks have found 31 percent of the incidents attackers broadcast clear signs to those around them prior to the attack. (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students, Citation2017) A recent Janes study indicated that 53 percent verbalized their intent to commit a terrorist attack to those around them and 41 percent voiced their intent online. (Jackson, Citation2016) Other studies place the percent of leakages as high as 83 percent. (LiveSafe, Citation2017) Those signals ranged from sudden mood changes to browsing online sites encouraging violence, describing successful attacks or perusing weapons.Footnote2 Many either bragged to friends, family and colleagues of their intent or had emotional outbursts to coworkers extolling the rightfulness of the use of violence, a behavior which professionals refer to as “leakage.” Only in hindsight do witnesses, who dismissed the rants as either the individual’s right to free expression or just the attacker’s typical tirades, realize the attacker was an individual “at risk.” They also exhibit non-verbal leakages ranging from out-of-context, increased interest in weapons to changes in appearance and demeanor.

A July 2017 event involving a Syrian family residing in Denmark illustrates a success story. The incident is that of Ahmed Samsam. Samsam, who had served with IS-AQ in Syria, returned to Europe. He eventually travelled to Spain. Some of Samsam’s alert relatives suspected he was now willing to take his fervor to the next level and initiate an armed attack, possibly against the World Pride Parade in Madrid, Spain. Samsam’s relatives reported their suspicions to European authorities, who on 1 July 2017 arrested Samsam in Malaga. Unfortunately, the number of other cases, where friends, colleagues, and relatives noted strange behavior but did not report it are too many to mention. These failures are the impetus for this article.

A touchstone for an indicator of an armed assailant is not him being a stranger. Quite the contrary, it is the strangeness, the out of place, out of context behavior which each of us must take note and report either to medical professionals or law enforcement. Reporting a Phase I indicator to medical professional, a counselor, human resources member, or clergy member will pay higher dividends than reporting it to law enforcement, which has comparatively fewer resources and lacks the investigative jurisdiction to investigate somebody, whose emotional rants or mood swings resemble large swathes of society and resemble somebody going through a period of emotional stress.

Like an individual pondering suicide, armed assailants either consciously or unconsciously, want others to know they are in crisis, if only to ensure those around them know they have the intent. Ironically, the armed assailant has not solidified his plans during the initial phases of the cycle. An alert or caring person can intervene to derail, to defuse or deter the attacker. Without intervention though the armed assailant moves into more secretive stages during which he begins to formulate and solidify this plan. Early intervention by a caring person, e.g., a family member, an employee counselor, a medical professional or religious leader can prevent the would-be armed assailant from progressing to the next stage, the initial planning phase of the attack.

Once the would-be armed assailant has entered the initial planning phase and progresses through the planning cycle, his penchants are to increase his security and obscure his intent. Even so, he is not invisible to those around him and those at his target site. Even the best-trained and most security-conscious individual make mistakes as they surveil and test the security of their target. They also must acquire the material he will need for his attack. He may need to procure resources to purchase the weapons or bomb-material. The next section of the article will go into more detail on the indicators at each stage, of which there are five. As the would-be attacker moves through those stages, he becomes more determined, more dangerous, and more secretive. Recognizing and reporting the indicators early are two key risk management measures to prevent your venue from being the next victim.

Myth 2: With regard to ideologically motivated armed assailant incidents, the armed assailant threat stems not only from those claiming allegiance or expressing support for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant/Al Qaeda (IS-AQ). The prevalence in the media of IS-AQ-inspired attacks seems to leave the impression the armed assailant threat comes from that sector of the political arena alone. However, the right-wing extremist and black separatist threats are also on the rise and not insignificant. (Struyk, Citation2017) Dylan Roof and Brevik are two of the best-known cases of right-wing extremists launching attacks for ideologically right extremist-inspired reasons. The 2018 attack on the Tree of Life Congregation in Pittsburgh and the string of anti-Semitic attacks in New York in December 2019 only underline this disturbing trend.

Of the 201 ideologically inspired incidents which occurred in the US between 2008 and the end of 2016, 115 cases involved right-wing extremists; only 63 instances involved those linked to IS-AQ inspired terrorists. (Grosman) Another study indicates that of the 215 ideologically inspired incidents,Footnote3 excluding the 9//11 attacks, which occurred between 1990 and 2014, 177 incidents involved right-wing extremists; only 38 involved IS-AQ inspired terrorists. Right-wing extremists killed 245 individuals while IS-AQ killed 62 individuals. (Parkin et al., Citation2016) And, between 2014–2015 hate-crimes increased overall by approximately 6.7 percent. Hate-crimes against blacks rose by about 7.6 percent, anti-Jewish incidents rose by about 9 percent, and incidents based on sexual orientation rose by about 3.5 percent. Hate-crimes against Muslims rose by 67 percent. (Zapotosky, Citation2016)

The figures are not meant to downplay the IS-AQ threat. The IS-AQ threat remains and will remain very substantial. The statistics only indicate that it is imprudent to ignore the threat from other shades of extremists. The polarized political environments in the United States and Europe only serve to exacerbate the trends as each pole on the extremes uses attacks by the other to rationalize its counterattacks. Likewise, those who witness an individual with right-wing extremist beliefs enter the radicalization and/or attack cycle need to be alert to the real threats the individual poses. Venues too need to guard themselves against the threats emanating from all sides of the politico-ideological spectrum.

Myth 3: Political leaders statements have little impact on the willingness of the potential active shooter to commit his crime. While acknowledging that individuals such as Usama Bin Laden, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, or their senior ideologues can inspire active shootings by IS-AQ inspired killers, there is reticence to believe western political leaders of democratic states can impact the decision-process of right-wing, black separatist, pro-life, or eco-conservationist motivated killers. Belief in such a myth is pure folly. As political leaders passively or actively condone racist attitudes, potential active shooters can more readily justify their actions. Comparing the Department of Justice’s hate crime statistics shows a disturbing tendency, as the political rhetoric against minorities have increased, so has the rate of hate crimes against minorities. Between 2014 and 2017, hate crimes against non-Whites have risen by 29 percentage points, and, since the 2016 election and Donald Trump's inaugartion as president, such crimes have increased 22 percentage points. There is one point of consistency in the racially based hate crime statistics: As a proportion of all those committed, the percentage of hate crimes committed against non-whites has hovered around 82 percent of all racially based hate crimes committed. Likewise, since 2014, anti-Jewish hate crimes have risen by 54% and between 2016–2017, they rose 37 percent. Anti-gay hate crimes show similar increases, 59 percent between 2014–2017 and 13% between 2016–2017. Anti-Islamic hate crimes rose 77 percent since 2014. They did decrease by 13% between 2016 and 2017. (Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice, Citation2014–2017)

Myth 4: The Defeat of IS-AQ in Syria and Iraq will lessen the IS-AQ threat. Defeating IS-AQ in Iraq and Syria is a necessary and laudable objective, however the hope that the victory will cause the threat from IS-AQ inspired terrorists to decrease is misplaced at best, wishful thinking at worst. The IS-AQ threat did not start in 2001 with 9/11 or with the IS invasion of Iraq in 2014. The IS-AQ threat has its roots in the 1950’s, got impetus during the Soviet-Afghan War and the 1990’s Balkan Wars, and gained incalculable momentum with Operation Iraqi Freedom. The ideological battlefield is worldwide; worse than being worldwide, it is viral as the internet offers legions of venues for individuals to become radicalized, to connect with like-minded individuals, and to seek methods to carry out attacks.

The IS-AQ threat is not an outright war for political power over a territory. In the wake of the Manchester bombings, Dabiq, ISIL’s official publication, cited the topic six reasons ISIL hates westerners. Of the six, the first five are because westerners are disbelievers, i.e. they shun Allah and his teachings; they are liberal in their moral views; many westerners are atheists; westerners insult Islam, and they commit crimes against Muslims. The sixth reason, although using drones to attack Muslims is included in the fifth reason, is for invading Muslim lands. (Dean & Evans, Citation2017) The IS-AQ threat is more an ideological struggle against Western values and westernization of traditional cultures than against an outright military threat.

Like the other extremist ideologies, the IS-AQ ideology preys on those whom, in reality or only in their own minds, globalization has socially or economically marginalized. Most adherents to extremist ideologies are seeking a cause which explains their own inability to succeed in twenty-first century society. Many IS-AQ adherents, notably those who served as fighters in Iraq, cite hope of financial gain or sheer desperation. Others cite their marginalization from mainstream opportunities. Notably, there are indications the higher rate of terrorist attacks in Europe (604) versus the United States (100) between 2015–2016 is largely due to Europeans’ comparative inability or unwillingness to successfully integrate immigrants into their societies. (Hjelmgaard, Citation2017) Individuals, like Brevik, turn the table and blame broad acceptance of Muslims and other minorities into society as the root cause for economic and moral decay of Western society. The polarization creates a cycle of mutually reinforcing paranoias and becomes a self-fulling prophecy.

Beyond question, IS-AQ has planted seeds throughout all countries and has a global reach through the internet which will transcend any successes which coalition forces achieve. Defeat in Iraq and Syria may even spur higher levels of threats in Europe and North America as adherents seek revenge or attempt to prove the cause is eternal. Hence, without addressing some of the deeper underlying causes, the IS-AQ threat will persist after any nominal defeat of ISIL in Mosul, Raqqa, or Fallujah.

3. Demographics and the armed assailant

Broadly, there are no definitive demographics of an armed assailant. However, J. Reid Malloy’s 2016 study provides some broad insights, which recent events seem to corroborate. The vast majority are males and usually younger than 45 years of age (95 percent). Most are or feel socially or economically marginalized. Namely, most are single (67 percent), specifically never married (62 percent) or were divorced (5 percent). And 79 percent had no children. Finally, most are either unemployed (75 percent) or underemployed (8 percent). (Meloy, Citation2015) Their level of education varies. The majority did complete school. Many entered college, but they did not complete their degree. The general impression is they feel society has unjustifiably discriminated against them because of their race, their religion, or ethnic background. (Meloy, Citation2015).

The general perception is most active shooters are Caucasian (or AQ-IS inspired). One need only recall the Black Hebrew Israelites’ taunts of being future active shooter directed at students from Covington Catholic High in front of the Lincoln Memorial in January 2019. Ironically, the Black Hebrew Israelites’ beliefs reflect the same racist bias against minorities as those expressed in the mainstream media. In a 2018 article in the Journal of Crime and Delinquency, scholars found there is an inherent bias in the way the media assigns blame to those who commit a mass shooting, defined by the FBI as a killing of four or more victims at a single location in a single event. (Duxbury et al., Citation2018) One need only consider how news organizations report about an armed attack committed by an African-American or Hispanic. White males, who commit mass shootings, receive more sympathetic treatment. White males’ actions are attributed to mental or emotional instability versus portraying African Americans and Latinos as being violently inclined.

Emma Fridel’s 2017 study tends to validate those findings. She found while Whites account for 49 percent of public mass shootings, the rarest form of mass shootings, they account for only 22 percent of the felony mass shootings. African Americans account for 31 percent of the public mass shootings and 50 percent of the felony mass shootings. (Fridel, Citation2017) And, a 2017 Department of Justice study found that between 2012 and 2015, most violent crimes (51%) were intra-racial, i.e. the perpetrator and the victim share the same race. Many of these violent crimes are linked to other criminal activity, such as drug-trafficking or discouraging others from cooperating with law enforcement in investigating other crimes. (Morgan, Citation2017) The prevalence of intra-racial versus the lower prominence of interracial crime stems from lower fear of being prosecuted. Anecdotally, there is a belief that law enforcement are less prone to arrest and prosecutors less eager to prosecute a crime committed by a Latino or African American on a White than they are willing to pursue legal action when the alleged perpetrator and the victim are both members of a minority community.

There is also some question about the reliability of how the Department of Justice classifies interracial hate crimes. It seems the Department of Justice’s hate crime statistics bias hate crimes committed against Whites too low and reflect a similar strain of racial discrimination, attributing Black and Latino attacks on Whites as violent crimes while White attacks on Blacks and Latinos as hate crimes. Thus, it is sound to conclude that race is not a reliable predictor of who will be an active shooter and that the priming and framing function of the media, imbued with a degree of inherent bias, distort reality

The potential for recruitment increases if an overlapping political cleavage, as political scientists call it, exists, e.g., economic disadvantage rooted in a history of real or perceived discrimination or persecution. Those who successfully proselytize right-wing and IS-AQ extremists find fertile recruiting grounds in economically disadvantaged and ghettoized neighborhoods. Likewise, many have prior criminal, often misdemeanor, histories as was the case with the Brussels bombers. For those, who have served time, prison often has served as a recruiting and grooming grounds, where senior extremists offer what could-be armed assailants lack: A sense of purpose and a means to redeem themselves for the previous wrongs they have committed. Finally, there is seems to be a prior history of emotional problems.

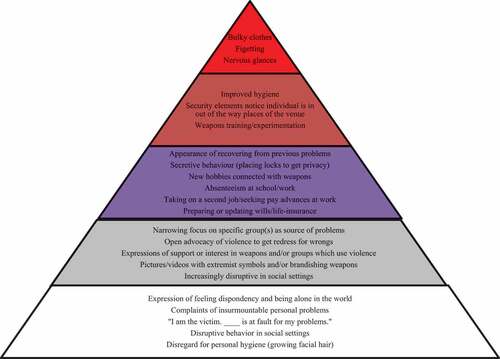

Regarding the more specific traits which an armed assailant exudes, as depicted in Figure , the numbers of individuals who progress through the stages is like a pyramid. Many who exhibit indicators, especially those in the first phase, are legion, but the number of those who actually commit an armed assault are comparatively few. Family members, employers, religious leaders, and medical professionals, who intervene early in the cycle, or simple changes in an individual’s circumstances trim down the number of those who progress further up the pyramid.Footnote4

That said, in terms of risk management, the advantage rests with the armed assailant. To paraphrase Condoleezza Rice, the risk manager must get it right 100 percent of the time; the armed assailant only once. Understanding, assessing, and mitigating the risk increase the odds in the risk manager’s favor. Knowledge of the indicators is one risk mitigation measure.

4. The five phases of the armed assailant attack cycle and their indicators

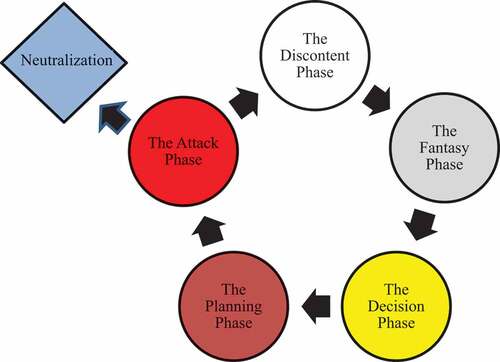

There are five phases through which the armed assailant progresses. As illustrated in Figure, the phases closely resemble the terrorist planning cycle. But it is also akin to the planning cycle which criminals, most notably burglars or bank robbers, consciously or unconsciously follow when they plan their crime. Broadly, there is a period of contemplating the crime followed by periods of gathering the information necessary to commit the crime, of acquiring the tools necessary, and of conducting trial runs to check the feasibility of the plan. And, finally, there is the moment when the criminal executes the crime. During each period, the criminal displays certain necessary behaviors which others can notice.

When the could-be attack reaches Phase 5, the Attack Phase, there two outcomes, as illustrated in Figure . The first is to carry out the attack; the second outcome is labelled “Neutralization.” Neutralization, as used here, is a rather broad term to connote either law enforcement or security forces arrest the individual or the individual turns his weapon on him/herself. The third alternative is the attacker changes his mind. Naturally, all three of these possibilities exist throughout the cycle. In the phases prior to launching the attack, it is also possible, even preferable for all parties involved, that a third-party, such as a psychologist, a cleric, a family member, or a trusted associated, intervenes to deter the could-be armed assailant by counseling or providing him/her some source of hope. And, of course, those who recognize the indicators, can also alert the appropriate professional personnel who can then intervene.

As illustrated in Figure , the phases themselves progress up a hierarchy with the intensity of conviction to act increasing as the could-be armed assailant become a commited armed assailant. The number of individuals who pass through each stage becomes fewer. Many people experience periods of feeling alienated from society. But only a few find it necessary to commit an armed attack as means to address those feelings.

As a cautionary note, there are three specific provisos regarding the indicators and the phases through which the armed assailant progresses. First, though placed into phases, the indicators in the phases are not necessarily distinct or confined to a single stage. The boundaries up the pyramid are fluid. Phase 2 indicators may appear during an individual’s Phase I and so on. Browsing the internet for extremist sites or interest in weapons, which are listed in Phase II, may appear in Phase I.

Second, there is no clear timeline about how fast or how slow an individual progresses up the pyramid. Undoubtedly, much depends on the pace and intensity of events which trigger the progression. Likewise, events can occur which slow or even halt the progression.

And, finally, no single indicator, especially in the early phases, is defining. It is the compilation of several factors which should create cause for alarm and provoke intervention. The most compelling indicators stem from changes in an individual’s normal behaviors. The danger arises not from strangers but from an individual’s strangeness, specifically e.g., departures from their normal behaviors.

As a quick overview, Phase I, “The Discontent Phase,” is a period typified largely by feelings of hopeless and social isolation, real or perceived, and a generalized frustration with the world around him. Phase II, “The Fantasy Phase,” is a period of increased but generalized anger and the period where the could-be armed assailant fantasizes about how to get even with those, often specific groups or individuals, to whom he attributes to be the source of his discontent and isolation. Phase III, “The Decision Phase,” is the period during which the armed assailant has decided that using violence is his best redress to right the wrongs done against him, perhaps even to redeem himself for his own past wrongs, or to raise his self-esteem by showing his true worth. Phase IV, “The Planning Phase,” is the period when the armed assailant chooses his target, acquires his weapons, and acquires information to ensure his attack is successful.Footnote5 And, Phase V, “The Attack Phase,” is the phase where the individual is at his target venue prepared to launch his attack. While family members, coworkers, associates, classmates, instructors, and friends are the mostly likely to see indicators in the first three phases, security elements are those most likely to see the indicators in Phases IV and V. That said, family members and associates may see indicators in the latter phases. As well, it is possible for alert security forces to notice indicators in the early phases, especially if the could-be armed assailant is a co-worker or frequent customer.

Phase I-The Discontent Phase: During Phase I the typical potential armed assailant expresses feelings of being or is socially isolated. Many of the symptoms correlate with those who are depressed. He is or becomes withdrawn. His colleagues may view him as “a loner,” somebody whom others exclude or whom society marginalizes, be it through lack of economic opportunities or professional advancement. He has become a stranger in his own land, at least in his understanding of his current situation. His leakages during this period may be about financial, legal, professional, or domestic problems, especially as a result of some type of dramatic changes. It could be the breakdown of a romantic relationship, a loss of a job, or the onset of apparently unbearable financial burdens. It could be failure to achieve a new job or position. Or it could be simply rejection in general by his peers, his associates, or family. He may even feel bullied by those from whom he most seeks acceptance.

In his utterances, he feels victimized, blaming others generally for his isolation, and his inability to succeed in mainstream society. Others are the source of his failures. At work, at home or in social settings, he will be argumentative, disruptive, and prone to explosive emotional outbursts. He vents his frustration broadly, blaming general circumstances or large groups as the cause of his despair. He pays less attention to personal hygiene. His use of drugs or alcohol will increase, even to the point he abuses them. Not surprisingly, these behaviors and his feelings of isolation become mutually reinforcing. During this phase, he is clamoring for help. He may be testing to see if others respond to his cries while at the same time exploring the options available, only one of which is violence, to soothe the internal pain.

Phase II-The Fantasy Phase: At this point in the progression, the could-be armed assailant is searching for and imagining how to get re-dress for the slights against him. His feelings of despair exhibited in Phase I remain, but he has hope for a solution, one of which is the use of violence. In his mind he is visualizing himself exacting revenge, sending a message to those who have wronged him, and finally emerging victorious over his oppressors. And as is the case in all phases, changes in the could-be armed assailant’s normal behavior are the behaviors which need to alert those around him. While in Phase I, his anger is at broad swathes of society, during Phase II, the could-be attacker’s anger becomes directed at specific groups, specific individuals or specific lifestyles.

The most notable indicators involve his verbal leakages. His grievances narrow, identifying and focusing on a clear and distinct adversary. The level of his conflicts with others, classmates, co-workers, family members, associates, etc., in social settings increase in frequency, and in emotional intensity.Footnote6 Further, he will outwardly express sympathies with the use of violence by others to resolve problems and attempt to convince others violence is a legitimate means to resolve society’s, his group’s or his own personal grievances.

In addition to verbal pronouncements, his leakages may take non-verbal form, namely through writings, drawings, and pictures. His personal interest in weapons, violent groups, or successful armed attacks will also likely increase. These leakages are most apparent in his internet browsing habits, his choice of reading material, or his preferences in video games/online-gaming sites. He may establish contacts with individuals who advocate the use of violence and even refer to them in general terms, such as “a friend,” “an online acquaintance,” a “social media contact,” etc.

The backdrop against which potential armed assailants choose to pose is important. He could place pictures of himself on social media broadcasting his musings, for example, brandishing a handgun threateningly or with a symbolic hand gesture. IS-AQ-motivated armed assailants will point their extended index finger to the sky, signaling their allegiance and meaning “There is one god and that is Allah. Also, a lightweight, black and white small-checkered scarf should immediately sound alarm bells. Similarly, a white-power fist raised against the backdrop of a Confederate flag, especially one with the words, “The South Shall Rise Again!” or a flag embroidered with a swastika or its derivative should be a significant cause for concern. These leakages, verbal and non-verbal, are the indicators to those around him the could-be armed assailant is coming closer to finding a salve for this pain.

Phase III-The Decision Phase: For the could-be armed assailant’s associates and family, this phase may appear as if he has “gotten better.” He appears calmer, more at ease, and in better spirits. Not excluding the possibility, he has indeed found a peaceful path to ease the pain, the could-be armed assailant has identified his most viable course of action: violence. He has found his re-dress and more than simply visualizing it, he knows it. Those around him may confuse his apparent peace of mind for him “getting better.Footnote7” His mood changes from one of outward anxiety and frustration to one of seemingly inner peace. The emotional outbursts recede. Public uncensored verbal support for violence too diminishes. A state of calm appears to exist.

However, in private his anger seethes and at home seeks greater privacy to begin finalizing his plan. He is more alert to his operational security. He may change locks on his doors, change passwords to his digital devices, or simply seek out a more private spot within his residence. The Sandy Hook and Columbine perpetrators all made strong efforts to limit what their parents knew about their preparations, much of which got attributed to typical teenage demand for more privacy in his/her personal life.

During this phase, the could-be armed assailant begins acquiring or gaining access to weapons and/or explosive materials. He begins practicing, perhaps claiming he has found a new hobby or justifying his actions as a seeking way to defend him or others from criminals and thugs. He may practice his tactical maneuvers by playing paintball. The common tread being he shows an increased interest in violence.

At work, he may ask for pay advances, seek to references to take out loans, or take on a second job in order to fund his purchase of weapons. At work or school, his search for time to plan and practice may cause increased absenteeism. He could travel abroad to countries, where he can meet, train and receive approval to carry out his attack.

He may also start putting things in order as if preparing for death, namely penning final letters to loved ones and drawing up legal documents, e.g., wills, life insurance, etc. He may privately prepare manifestos, which he may leave for others to find or to place online, justifying the course of action he has now chosen. It is also during this phase he increases his security dramatically to limit the risk others do not detect his plans. He may choose to use virtual private networks and begin encrypting his communications with others.Footnote8 He will likely erase his true-name identities on social media and the internet, replacing them with pseudonyms, nom de guerre, and avatars. Beyond a doubt, the could-be armed assailant has entered a critical phase.

Phase IV-The Planning Phase. Phase IV involves target selection and reconnaissance of the target. In Phase III, he has chosen the means. Many of the indicators, e.g., public appearance of being more normal and privately secluding himself from those who could detect his intentions continue. In Phase IV, he is choosing the time and place of the attack. The will-be armed assailant searches, like a common criminal, for the target venue, estimating the time when he can inflict optimal harm, and identifying vulnerabilities, be they in the physical environment, in security personnel’s routines, and in employees,’ patrons’ or coworkers’ careless security practices. More will be said later about trends in venue selection, but generally the will-be armed assailant is searching for a relatively unprepared, also known as soft, but meaningful target venue.

With regard to identifying the target and searching out vulnerabilities, IS-AQ entities recommend will-be armed assailants use the internet to its maximum advantage. (Abu Ubayda, Citation2016) Online maps and photos of facilities provide valuable information and limit the will-be armed assailant’s need to physically visit the target venue and minimize the risk surveilling the site could alert onlookers and security personnel. Likewise, a will-be armed assailant can use the internet to identify which dates and times a target venue will have the largest crowds or the most meaningful events so as to maximize the impact of his attack.

Once exhausting the internet for information, the will-be armed assailant needs to visit the target-venue to choose his most efficient entry, staging, and launch points, the latter being the point where he starts his killing spree. In this regard, the will-be armed assailant has two competing priorities. The first priority is to gain as much knowledge of the target-venue, so his attack produces maximum results. The second priority is to avoid drawing attention to himself. He needs to blend into the target venue’s environment and be conspicuous so as not to draw attention to the fact he is gathering the information he needs to stage his attack. Again, the indicators during Phase IV come from the strangeness of an activity, not necessarily the stranger himself.

Co-workers, customers, classmates, and other “insiders,” who become armed assailants, have a distinct advantage. They have already spent significant amount of time on target and know the facility, its activities, its peak periods of activities, and its vulnerabilities. The Orlando shooter, San Bernardino shooter and the Columbine killers all spent significant periods of time at their target venues and, aside from perhaps the occasional odd looks from others due to their personality traits, were just “another customer,” “just another co-worker,” or “just another student.” They more or less had the general confidence of those around them that they were reliable and non-threatening. Hence, the insider has a clear advantage and poses the most dangerous of threats because he has already blended in.

With that in mind, patrons, co-workers and especially security personnel need to be alert to individuals who, out of context, take pictures of entrances/exits, apparent structural faults, and avenues of approach, e.g., the path to entering a building. It is also essential to be alert for individuals sketching drawings or maps of a given facility or street leading up to the facility. The will-be armed assailant may also attempt to identify lightly guarded points of entrance, especially side-doors and emergency exits, especially those which do not close properly or which patrons or employees prop open to take smoke-breaks or use as short-cuts to exit and re-enter a building. Finding a stranger around an entrance or exit typically used by employees or service personnel should be especially alerting.

Likewise, finding a stranger in contextually out of place locations within a building or at unusual times should be a warning sign. The will-be armed assailant may also attempt to test facility security’s alertness and employees’ adherence to security policies. For example, do people with legitimate access allow others to enter controlled areas without scrutiny or without conducting due diligence to establish a legitimate reason for being in a specific location. When somebody asks an individual, be it a common criminal or will-be armed assailant, he may not know enough to give a justifiable answer for entering into or being in a not-often frequented area of the building. And, when confronted, the will-be armed assailant will react nervously, possibly acting offended, and demanding others respect his privacy or private intentions.

The will-be armed assailant may also conduct “test runs” to determine whether he can get his weapon undetected into the target-venue. If he intends to use a vehicle, he may make multiple, perhaps consecutive trips in quick succession past the target-venue without a good explanation. If he intends to use the vehicle as a bomb, he may park or abandon his vehicle in front of the site to assess how fast law enforcement and security react. And, if he intends to use a hand-carried explosive device, he may leave a backpack, shopping bag, or satchel unattended to determine whether and how fast others pay enough attention to report it or remove it. Depending on his temerity, he may attempt to enter a building with a heavy metal device, knife, or even toy weapon to see whether the installation’s metal detectors or security personnel take notice.

Finally, on his physical appearance, the will-be armed assailant surveilling a target-venue will likely seek to blend in with the others in the area or building. His personal hygiene habits will improve. An individual ascribing to IS-AQ motivations will likely be clean-shaven and neatly, appropriately dressed so as to minimize drawing suspicious gazes. Whether at business venue, or in a resort area, he will dress appropriately. He knows, if not instinctively but by others’ experience, he needs to avoid drawing undue attention to himself.

4.1. Phase V-the attack phase

At this point, the danger is imminent and chances to intervene without somebody getting injured are few. The armed assailant, however, does broadcast signals which enable others to minimize extent of the impact. He is, in common vernacular, “switched on.” He is focused and concentrated on carrying out his plan. In his mind, everything must go right. Because of or perhaps despite his level of preparedness and determination, the armed assailant is at his highest stage of alertness causing him a heightened degree of nervousness and over-attentiveness to his surroundings.

As in Phase IV, he will endeavor initially to blend into the environment, appear non-threatening and unobtrusive. Whether he intends to use weapons or an explosive device, he will move purposefully. He probably has an unfocused stare and is likely to be muttering to himself. His head may be darting back in forth, swiveling. He will make efforts to conceal his hands. He may unexplainably enter or exit the facility repeatedly. His movements and demeanor may appear out of context. If he has a timetable in mind, he may be glancing furtively at his watch or cell phone.

If he is using a handgun, knife or strapped on explosive device, his clothing may appear weighted more on one side than the other. There may be bulges in his clothing, typically at the chest level, hip level or ankle level. Weather conditions could betray the location of the weapon. In all likelihood, rain will dampen, and wind will flatten the clothing to reveal unexplainable but telling bulges. Humidity and sweat too are likely outline the contour of a weapon.

His high state of alertness may cause him to touch the weapon checking it is still in place. He may shift his hip on the side he has the weapon to prevent others from seeing it. He may adjust it or check it when going to sit down or when standing up. Or, if the public is fortunate, in a careless moment, the armed assailant may accidentally shift his jacket or shirt, flashing the weapon. Or he could drop it as he moves or attempts to reach for the weapon.

In the case of an explosive or rifles, the armed assailant probably will wear bulkier clothing and longer coats, especially if in his planning he has determined he has the advantage, namely the element of surprise. He may wear multiple layers and not be dressed, notably in the non-winter months, according to the season. If he is not carrying an explosive device or rifle underneath his clothing, he will likely have a heavy bag, perhaps with squared or rounded objects protruding from the sides. Nature has created very few objects which are perfectly geometrical; only humans have. Concealed geometric shapes are a definite signal of pending problems.

If he intends to plant bombs, he may conceal them in bags and boxes. The device may put off an acrid odor. Wires may protrude. It may leak oily liquids. And, more than likely, it will be heavy.

The use of vehicles is not new. The Oklahoma City bombing is a case-in-point. The use of vehicles as ramming devices is comparatively new outside of the Middle East and parts of Far Asia. If the vehicle is the bomb, it will likely be weighted to one side or another. The front or rear end may ride closer to the ground than the other. If the armed assailant intends to use the vehicle as a battering ram, he may likely again make multiple, unexplainable passes near the target-venue, to ensure he has an unobstructed path and to gain the speed he needs both surprise the victims and to maximize the damage. Or he may double-park on the side of an intersection closest to the target-venue, waiting for the moment when there are no vehicles or other obstacles blocking his line of attack. Finally, he may attach items to the undercarriage or front and sides of the vehicle, to include the axels, e.g., devices he deems he needs to maximize injury. At this point, his greatest challenge is ensuring he has enough momentum and means to inflict maximum damage.

In Phase V, the advantage lies with the armed assailant. He is already set to initiate his plan and knows his intentions. Security personnel and others in the area have limited time and few courses of action other than to confront the assailant and rush to clear the venue as quickly as possible. It is this area where insider attack training programs excel in preparing people. Unfortunately, by this point, it is often too late. Somebody is going to get injured or killed. The preference for all risk managers is to preclude the circumstances which enable the armed assailant to get this far. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

Regardless, having a definitive plan to enable innocents to escape or conceal themselves is imperative. More important than having a plan is training and practicing the plan. As with fire drills and bomb drills, venue security-managers should be asking themselves whether their employees know how they would secure doors to isolate the attacker from the attacked; which entry/exit points to use to evacuate bystanders; and what roles of each security officer has at a given post during an attack. At venues without a dedicated security presence, employees too should know what, if any responsibilities they have. Surely, a quick-thinking, selfless employee, who lacks training, may be able to scurry patrons into backrooms, closets, offices, or out other doors. However, from a risk-management perspective, knowing what to do creates a level of certainty as well as confidence. In terms of limiting damage and, as gruesome as the task is, training is imperative. As the military and law enforcement know, you fight only as well as you train.

5. Conclusion

Why individual progresses up the pyramid while others do not is truly a matter for further research and debate. In his recent book, Marc Sageman contends, with regards to ideologically motivated armed assailants, “a few exasperated activists step up to volunteer to defend their (real or imagined) community as soldiers defending their victimized comrades against salient and belligerent out-groups” and they are willing to sacrifice their lives to do “something significant with their lives.” (Sageman, Citation2017)

While instructive in theory, Sageman’s proposition is less useful to the general public. What concrete, observable events trigger the progression to the point he is willing to kill others and put his own life in danger? As stated during the discussion of Phase I, the trigger could be a significant change in his personal or professional life. Perhaps it is the loss of a job, a trusted friend, or a parent. It could be an unwanted, perhaps unjust change in his roles, responsibilities or work group. It could be a sense of abandonment or betrayal. When he found concrete indications, his mother had intentions to commit him to a mental institution, undoubtedly the Sandy Hook killer felt his mother had betrayed him. She was also the first to die.

In other instances, it could be an external event, unrelated to his immediate surroundings. Defacing or denigrating a religious article or site locally or in a far-off land is a prime example. Not surprisingly, Muslims, Jews and Christians alike take offense to somebody burning or shooting holes through their holy writings. And images of somebody defacing an important symbol, for example, a flag or a monument could trigger a progression. Symbols, like religious articles and sites, have a deep emotional significance, often defining a group’s identity. One only need note the rabid responses on both sides of the debate over the Confederate battle flag and public monuments. The Charlie Hebdo attack (January 2015), the foiled attack against the “Draw Mohammed Exhibition” (May 2015), and the Charlottesville attack (August 2017) are cases in point. Monuments have deep politico-symbolic value. Note the agitated response Russians have to the Polish government removing monuments to soldiers who fell defeating the Third Reich.

Maajid Nawaz, a former radical who now works to de-radicalize others, attributes his progression to third reason: a feeling of empowerment he got when he realized threatening and using violence leveled the playing field against his oppressors. Nawaz, an ethnic Pakistani and resident of Essex, England, felt local police were profiling him and Neo-Nazis were persecuting him, and other members of his community based on their heritage and color of their skin. One afternoon, some local Neo-Nazis led by “Mickey,” stopped Nawaz and his friend. Frustrated and scared, Nawaz’ friend pointed at his bag and yelled, “I told you we’re Muslims and we don’t fear death. We’re like those Palestinian terrorists on television blowing up planes … We’ve been taught how to make bombs and I’ve got one here in my rucksack.” (Nawaz, Citation2012)

The latter part was a bluff, but their assailants fled. But associating with a group who posed clear threat and had the means to carry out the threat was enough to convince Nawaz in the rightness of using violence. It returned his dignity when nothing else could. Tellingly, Namaz writes, “The violence I had been subjected to, the police discrimination, the greater awareness of foreign conflicts such as Bosnia, all this undoubtedly made me receptive … But while all that was essential background, it was that afternoon in the park and the fear in Mickey’s eyes that triggered my decision to take things further.” (Nawaz, Citation2012)

Nawaz’ explanation seems to offer the strongest argument. Perceiving he lacks another option, the could-be armed assailant finds empowerment in becoming a determined armed assailant. In his decision to use violence, he finds redress to the wrongs he endures. But, more importantly, he finds a sense of direction and means to fill the void left by his feelings of isolation. His planning for the event both distracts and directs him. He has a sense of purpose (again).

In the wake of the Parkland attacks and the seemingly never-ending occurrences of individuals using violence against others, what can the average person do? First and foremost is to be aware of the indicators and to report them to a person who can intervene. For the risk-manager of a public venue it is important to decrease the vulnerabilities which make a venue susceptible. Armed assailants choose their targets based as much on their estimation they can succeed in their attack as on their symbolic value.

Traditional terrorism, as during the bygone days of the Irish Republican Army, the Red Army Faction, and the Weathermen, targeted the establishment, namely government, military and key businesses supporting the government, to send a message but still win over public support. Even the infamous Berlin nightclub bombing was aimed primarily at killing service-members and public servants, who frequented the bar. The nature of terrorism has changed. The public is no longer the audience; it is the target.

A recent study found that in over 80 percent of the right-wing extremist killings, the armed assailant chose his target because they either knew the individuals and purposely decided to kill them for ideological reasons or because the victims were representative of something to which he was ideologically opposed. IS-AQ inspired armed assailants chose their victims based more on their lifestyle or routine. (Parkin et al., Citation2016) The common factor which unites the two findings is that identifying the venue which fits the ideological message is critical.

And, a 2014 Texas State University-FBI study found approximately 89 percent of all armed assailant attacks occurred in public spaces, the majority of which were commercial venues (46.7 percent) followed by educational venues (24.4 percent) and open spaces (9.4 percent) Attacks on religious sites made up only 3.8 percent of the total attacks. And attacks on government, including military sites,Footnote9 made up only 11 percent of the attacked venues. (Pete & Schweit, Citation2014)

What do the numbers indicate? As in the choice of a home or a business, armed assailants know it’s all about location, location, location. Combining the findings of the two studies, it would be fair to estimate right-wing extremists carried out the majority of the attacks on the religious sites. And IS-AQ sympathizers likely carried out the majority of the attacks on commercial venues, symbols of a lifestyle, not specific individuals who represented a governmental or economic establishment. The right-wing extremists aimed to kill those with a specific religious, racial or ethnic character. Such was how Roots, Brevik and Beate Zchäpe, leader of the National Socialist Underground, who advocated a “foreigner-free Germany.” Zchäpe killed nine people of Greek and Turkish descent, and then bombed an Iranian family’s business in Cologne. Grafton Thomas' December 2019 attack on those celebrating Hannukhah at the home of Chaim Rottenberg in a Monsey, New York neighborhood, known for its large ultra-Orthodox Jewish population is another case in point, These armed assailants cared less about the identity of their victims and more about the lifestyle, hence the Manchester, Brussels, and Paris attacks and even the Orlando nightclub spree.

Why the dearth of attacks on government facilities? It is possible but unlikely armed assailants do not consider government facilities a tempting target. It is more likely government agencies have simply made it comparatively far more difficult for an armed assailant to stage an attack. In other words, the government has “hardened” their facilities while the private sector has not. Hardening entails implementing risk mitigation, e.g., security measures, which minimize the armed assailant’s likelihood of executing a successful murder spree. Government facilities have installed barriers outside their buildings to preclude a repeat of the Oklahoma City bombings. They have installed metal detectors and adjusted, both quantitatively and qualitatively, their security departments. They have imposed tougher policies and educated their workforce to the warning signs.

By and large, the non-government sector lags in adjusting its security posture. And, like a common criminal, the armed assailant looks for the easier, less alert, less protected target. It is like the old adage. When a bear is chasing you, you do not need run faster than the bear. You just have run faster than the guy next to you. Hardening your venue makes it a less attractive target.

In the current climate, all venues are at risk. Risk is a function of threat and vulnerability.Footnote10 And, it is not binary, a yes or no scenario. Risk exists on a continuum and is a matter of degree. And the degree of risk is a matter of where a given venue falls on a continuum. And the degree of risk varies with the type and timing of ongoing and upcoming events. Non-government venues can go far to reducing their risk by analyzing and reducing their vulnerabilities.

There is much a public venue can do to mitigate its vulnerabilities. There is a virtual shopping list of countermeasures which a public venue can implement.Footnote11 A first step is to critically and systematically analyze vulnerabilities, both permanent and event specific. And, while the penchant is to rely on law enforcement to inform venues of a pending threat, recognizing indicators of a could-be armed assailant and reporting them early to the proper people minimizes the threat. Likewise, increasing awareness and reporting of the indicators, as well as developing and practicing a response plan will reduce vulnerabilities, hopefully precluding a risk-manager from having his venue being the next site of carnage and mayhem.

The most dangerous threat to security is for outsiders to underestimate the intelligence and determination of the adversary. As public officials and private citizens become more aware of the indicators and tactics of a could-be armed assailant, the future armed assailant will undoubtedly adjust his behaviors to minimize being detected, especially the behaviors highlighted in Stage IV (Planning) and Stage V (Attack) phases. As in any match, the offense adapts its plays based on what it expects the defense has done or has expressed intent to do.

At least one sect of jihadists recognizes the need for their adherents to adapt to their environment in order to avoid drawing attention to themselves, thereby increasing their operational security. Specifically, Takfir wal-Hijra, an extreme fringe of jihadism, whom Spanish authorities are investigating in relation to the 2017 attacks in Barcelona, has long advocated that it is legitimate for its zealots to act non-piously, namely dress according in modern western clothes, date non-Muslim females, etc., purely as a tactic to blend into mainstream society. At least one of the Barcelona attackers had only recently purchased a new car and had a reputation for partying and smoking marihuana. Mohammed Atta, one of the ringleaders of the September 11th attacks, had a close association with an imam who advocated Takfir wal-Hijra approach. The Takfir wal-Hijra approach not only demonstrates the importance of watching for changes in individuals’ appearances, but also highlights the extremists’ cunning to adapt their lifestyles and tactics as law enforcement and the public identify tactics, techniques and procedures previous armed assailants used successfully in the past.

From new methods to conceal weapons to new methods of launching attacks, armed assailants adapt their plans based on what defenses law enforcement and security personnel put in place. Even during the planning stages, those who recruit, encourage or advise armed assailants study how law enforcement has detected and deterred other would-be armed assailants, and devise lessons-learned which they then use to adjust their followers’ behaviors and tactics. Risk-managers and the general public need also to adapt. But, more importantly, everybody needs to be aware and to report the “strangeness” of individuals they see around them.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mark A. Thomas

Mark A. Thomas is an adjunct professor at La Salle University in Philadelphia, PA, where he specializes in the underlying roots of ethnic conflict. Prior to returning to academia, Dr. Thomas spent several years in public service during which time he focused on countering armed assailant and other types of hostile threats. He currently advises and consults with public venues. i.e. educational, entertainment, and corporate entities, on how to mitigate the risk of becoming the victim of an armed assailant.

Notes

1. The article draws heavily from reports on terrorist attacks. However, I have surveyed articles on those who commit workplace violence, terrorist attacks, school-place violence; and classify them all as armed assailants’ attacks. While their motives differ, the indicators and processes are quite similar. Likewise, especially in the final two phases, armed assailants’ preparation and imminent attack behaviors mirror those of other criminals who seek to do damage to people or property.

2. I attribute the vast difference to what individuals define as a “warning sign.” If the warning sign is merely an overt statement of intent, the percentages will be lower. However, if we extend the definition further back in the process of radicalization and attack planning cycle, the percentages increase.

3. In strictly legal terms, the charge of domestic terrorism in the United States is problematic. 18 U.S.C § 2331(5) defines domestic terrorism as those activities that “involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State, appear to be intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping, and occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States,” and set the standard against which to prosecute domestically inspired attacks. 18 U.S.C. § 2331(1), uses the same descriptive language but states that the acts must occur outside the territorial jurisdiction of the United States or “transcend national boundaries in terms of the means by which they are accomplished, the persons they appear intended to intimidate or coerce, or the locale in which their perpetrators operate or seek asylum.” By terms outlined in 18 U.S.C § 2331(5) and the crimes committed, prosecutors likely could have charged Dylan Roof with “domestic terrorism.” His motive was ideologically (race-based) motivated as were the crimes committed by James Alex Fields Jr, who killed Heather Heyer and wounded several others in 2017 in Charlottesville. Likewise, the crimes committed by Robert Bowers in October 2018 at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh seem to meet the legal elements. Yet, prosecutors charged them with other crimes. Why? The answer lies in how 18 U.S.C. Sec. 2331 sets forth the definitions of words and terms that are used to establish the elements of the crime. Those are laid out within Chapter 113B (Sec. 2331–2339D) of the US Crimes Code. The remaining sections within Chapter 113B define the crimes and lay out the elements of each specific crime. Hence, the reluctance of prosecutors to charge the likes of Roof with domestic terrorism stems first and foremost from the fact Chapter 113B of the US criminal codes does not actually criminalize domestic terrorism, i.e. the chapter does not define a crime associated with domestic terrorism. Over the past 20 years the United States Department of Justice has prosecuted defendants who were accused of committing terrorist acts that took place within the United States under Chapter 113B. However. those acts fit within the definition of international terrorism and were prosecuted under the pertinent sections of Chapter 113B because the defendants acted on behalf of foreign terrorist organizations when they committed the acts. A second reason is prosecutors are not putting pressure on lawmakers to adjust 113B. Prosecutors, aiming for a conviction, can just as easily convict the likes of Roof using other existing statutes. Likewise, in their reporting statistics, federal law enforcement categorizes the crimes committed by Fields, Roof and Bowers as “hate crimes.” Hence, federal officials tend to charge individuals with civil rights violations, murder, destruction of public property, or similar type crimes, whatever evidence meets the legal elements of the crime. Part of the problem is lawmakers’ reticence to criminalize domestic terrorism clearly and concisely, at least in part linked to concerns of infringing on US hate groups’ First Amendment rights. By defining motive based on belief, lawmakers venture onto the slippery slope of making a form of free expression an element of a crime. On the other hand, appropriately chosen wording should pass the “clear and present danger test.” Finally, it is also likely there is a conscious decision made not to list a crime as domestic terrorism so as not draw public attention. Consequentially, cases of domestic terrorism are under-reported, especially those inspired by right-wing racist and homophobic beliefs, lack the status of terrorist events linked to AQ or IS-inspired attacks. This problem is not confined to the US. In 2015, in a large European city, an individual rammed his car into a crowd of innocent bystanders. Local law enforcement officials categorized the crime as vehicular homicide. However, there was reliable information within law enforcement circles indicating the individual had extremist ties and was motivated by an extremist ideology.

4. Why some progress from the broader population into the pyramid is a matter for further study. The number of people who meet the general description number undoubtedly in the millions. It is similar to question of why an individual commits espionage or any crime. Most claim they did it for the money. However, many people need money. Only a comparative few resort to committing a crime to earn it.

5. Phases IV and V compresses the terrorist planning cycle, notably Phase IV includes the site selection and the pre-attack tests phases as pedagogical means to make the indicators more accessible and usable to the average business owner and venue risk-managers.

6. The Meloy 2016 study confirms many of the indicators, though they do not segregate them into distinct phases. Notable is (only) 20 percent communicated a direct threat to law enforcement, implying the other 80 percent, if they made verbal leakages, did not privately.

7. Those who have served time in prison may enter the pyramid at Stage III, at least as far as his friends and family are aware.

8. As of December 2015, IS/AQ was publishing a German-language magazine, Kybernetiq, dedicated exclusively to advising jihadists on the best methods to maintain the online security of their operations.

9. While low, these numbers could be even lower than depicted depending on what is considered a military target. The study includes military killed in the line of duty. Including military killed in the line of duty may stretch the definition of armed assailant especially if the armed assailant was a member of an insurgency and the military member was deployed in a combat environment.

10. The first three elements of the Strengthens, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threat (SWOT) methodology identify the components of vulnerabilities.

11. In terms of the Return on Security Investment (ROSI), many countermeasures are low cost and prevent the ultimate tragedy as well as reduce the cost of loss of public goodwill, damage recovery, and damage to the label.

References

- Abu Ubayda, A. A.-A. 2016Safety and security guidelines for lone wolf mujahideen and cells, summarized English Translation. Al Fair Media Center. https://cryptome.org/2016/01/lone-wolf-safe-sec.pdf.

- Dean, J., & Evans, S. ISIS reveals 6 reasons why they despise westerners as terrorist’s sister claims he wanted revenge for US Airstrikes in Syria. The Mirror, 25 May 2017, 16 Aug 2017. Reach PLC. http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/why-isis-hate-you-reasons-8533563?service=responsive

- Duxbury, S. W., Frizzell, L. C., & Lindsay, S. L. (2018, November). Mental illness, the media, and the moral politics of mass violence: The role of race in mass shootings coverage. Journal of Crime and Juvenile Delinquency, 55(6), 766–19. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022427818787225

- Editorial. Why do Europe’s Muslims hate the west?. Investor’s Business Daily, 31 March 2016. Investor's Business Daily Inc. http://www.investors.com/politics/editorials/why-do-europes-muslims-hate-the-west/.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, US Department of Justice. (2014–2017). Hate crime statistics, 2014-2017. US Government Printing Office. https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/hate-crime-statistics.

- Fridel, E. (2017). A multivariate comparison: A felony, family and public mass murders in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, I–27. Sage Publications. https://www.hoplofobia.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/2017-Family-Felony-and-Public-Mass-Murders-in-the-United-States.pdf

- Hjelmgaard, K. (2017, 10 July). Why Europe has a greater terror problem than the United States. USA TODAY. Gannet Company, Inc. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2017/07/10/europe-terror-problem-united-states-isis/463554001/

- Jackson, P. (2016, 1 October). An overview of extreme-right lone-actor violence. Jane’s Terrorism & Insurgency Monitor. IHS Markit, Ltd. http://www.elibrary.com/elibweb/elib/do/document?set=pbsissue&searchType=&dictionaryClick=on&secondaryNav=&groupid=1&requestid=issue_docs&resultid=2&edition=&ts=026803BDCFE6FE88C2200C95BB9F0F4F_1477929746566&start=1&publicationId=PB008233&urn=urn%3Abigchalk%3AUS%3BBCLib%3Bdocument%3B246844251&pdfflag=y

- LiveSafe. 2017. Who becomes an active shooter? LiveSafe Solutions, Inc. http://www.livesafemobile.com/becomes-active-shooter/.

- Meloy, J. R., Roshdi, K., Galz-Ocik, J., & Hoffmann, J. (2015). Investigating the individual terrorist in europe. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 2(3–4), 140-152. http://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/tam000036. American Psychological Association.

- Morgan, R. E. (2017, October 7). Race and hispanic origin of victims and offenders, 2012-15. Publication of the Bureau of Justice Statistics. NCJ 25074 https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rhovo1215.pdf

- Nawaz, M. (2012). Radical: My journey from islamist extremism to a democratic awakening. Erbury Publishing LTD.

- Parkin, W. S., Chermak, S. M., Freilich, J. D., & Gruenewald, J. (2016, March). Twenty-five years of ideological homicide victimization in the United States of America. Report to the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.start.umd.edu/pubs/START_CSTAB_ECDB_25YearsofIdeologicalHomicideVictimizationUS_March2016.pdf

- Pete, B. J., & Schweit, K. W. (2014). A study of active shooter incidents, 2000-2013. Texas State University and Federal Bureau of Investigation, U.S. Department of Justice.

- Rossi, J. (2018, March 13). The states that experience the most school shootings have this 1 thing in common. Endgame360. https://www.cheatsheet.com/culture/states-where-school-shootings-are-morefrequent-have-this-thing-in-common.html/3/

- Sageman, M. (2017). Misunderstanding Terrorism. Philadelphia.

- Struyk, R. (2017, 15 August). By the numbers: 7 charts that explain hate groups in the United States. Cable News Network (CNN). Warner Media, Inc. http://www.cnn.com/2017/08/14/politics/charts-explain-us-hate-groups/index.htmlource

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Safe and Healthy Students. (2017). Active shooter situations: Preventing an active shooter situation, warning sings. Readiness and Emergency Management for Schools. US Government Printing Office. http://rems.ed.gov/IHEPreventingAnActiveShooter.aspx

- Zapotosky, M. Hate crimes against Muslims hit highest mark since 2001. The Washington Post, 14 November 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/hate-crimes-against-muslims-hit-highest-mark-since-2001/2016/11/14/7d8218e2-aa95-11e6-977a-1030f822fc35_story.html.