Abstract

There is a lack of research in the progress and evaluation of social capital in the field of agritourism and its effect on the development of the social identity of the entrepreneur. To explore this problem, this article aims to understand the development of agritourism businesses by focusing on the role of social capital and the social identity of an entrepreneur. To achieve this objective and based on a review of the relevant literature on the two concepts, an exploratory qualitative study is carried out on a sample of 10 agritourism entrepreneurs who were farmers, or who started businesses in this field. To do this, a large amount of documentation was examined, and semi-structured interviews were conducted and analyzed. The results revealed that social capital helps strengthen the social identity of entrepreneurs when launching their business. According to this observation, a conceptual model has been proposed to test this relationship in the future.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

There is a lack of research in the progress and evaluation of social capital in the field of agritourism and its effect on the development of the social identity of the entrepreneur. To explore this problem, this article aims to understand the development of agritourism businesses by focusing on the role of social capital and the social identity of an entrepreneur. To achieve this objective and based on a review of the relevant literature on the two concepts, an exploratory qualitative study is carried out on a sample of 10 agritourism entrepreneurs who were farmers, or who started businesses in this field. To do this, a large amount of documentation was examined, and semi-structured interviews were conducted and analyzed. The results revealed that social capital helps strengthen the social identity of entrepreneurs when launching their business. According to this observation, a conceptual model has been proposed to test this relationship in the future.

1. Introduction

The agritourism creates significant and continuous benefits for rural tourism sites. Consequently, those responsible for the development, promotion, and organization of rural tourism areas meet to assist in the development of these areas (Roman & Golnik, Citation2019) and to offer and adapt their rural tourism product or service to the needs of today’s customers. In the agritourism sector, the survival of individual businesses depends on their collaboration and cooperation with their network (Che et al., Citation2005). However, the importance of social structures and their effects on development has become very important for researchers. Qualitative as well as quantitative studies have presented this relationship and a review of the literature has defined the extent to which these networks and structures have become widely known as “social capital”. Social capital helps individuals to maintain a strong relationship with others and helps to facilitate collective action and group work. Social capital is very important because it allows people to come together in groups for the development of their environment.

Table 1. Qualitative sample characteristics

From this perspective, members of social groups rate activities according to their conformance with their identity prototype, making them more likely to engage in most appropriate activities.

From this point of view, members of social groups classify activities according to their conformity with their prototype identity, which makes them more likely to engage in the most appropriate activities. Besides, the social identity of entrepreneurs influences the type of opportunities they develop (Wry & York, Citation2017; York et al., Citation2016), the strategic decisions they consider appropriate, and the type of value they create (Fauchart & Gruber, Citation2011). Based on this observation, the analysis of the social identity of nascent entrepreneurs can also highlight an unexplained variance in the process of business creation (Fauchart & Gruber, Citation2011; Powell & Baker, Citation2017). Some researchers (Beyers et al., Citation1998; Ulhøi, Citation2005) have argued that the people with whom the entrepreneur spends time helping to reflect their actions and how to respond. Despite much research on social capital in the literature, there is not a complete picture of how the entrepreneur in different industries can gain insight into the concept of social capital and its effect on his social identity.

This study aims to shed light not only on the formulation of the dimensions of social capital in the context of agritourism but also on the interrelationships existing between these dimensions and the social identity of an entrepreneur through the following research question:

How does Social capital affect the reconstruction and development of the entrepreneur’s social identity in the field of agritourism?

These questions probably retrace the contours of a major research issue in the vast field of entrepreneurship and the approach to social capital for which a single answer cannot satisfy all its aspects. Besides, we believe that the agritourism sector can constitute itself, an imperative territory to attract a target that probably obscures a surprising experiential potential in the field of agriculture and tourism.

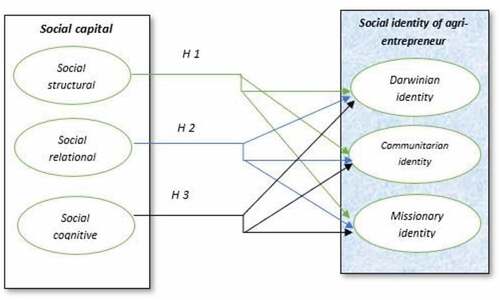

Through a literature review, we will first expose what can be the effects of the social capital of an agritourism entrepreneur on the development of his social identity. Our empirical approach includes a qualitative phase. We will present, in the third section, the research methodology and, in the fourth section, the hypothesis proposals. The results of the qualitative analysis will be detailed in the fifth section. We will highlight the main limitations of the work and conclude in the sixth section.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurial social capital

Ultimately, entrepreneurial success remains dependent on the degree of access to external resources, notably financial and informational (Groen, Citation2005). These resources include both the financing required for the development of the project (cash, credits granted, bank deposits, investment on the part of venture capitalists, aid and subsidies …), as well as the information advocated by suppliers, customers, venture capitalists, advisers, etc. to reduce the uncertainty surrounding the project. Furthermore, a research perspective initiated by the supporters of the social approach gave rise to a broad consensus among researchers in entrepreneurship according to which: the network of relations between the entrepreneur and his various stakeholders seems to play a protagonist role, touching on several aspects of the creation process. This relational fabric forms a set of channels through which information flows, knowledge is exchanged, and resources are acquired. Thus, access to the resources required for the development of the newly created project depends considerably on the knots made by the project leader (Simon & Tellier, Citation2013). All these social relationships constitute the social capital of the entrepreneur, which, in its most evocative sense, represents the number of people among whom he can access the resources that they possess (Pelletier, Citation2014). Most researchers define social capital based on social networks (Neergaard, Citation2005). The central proposition in the social capital literature is that networks of relationships constitute, or lead to, resources that can be used for the benefit of the individual, organization, or community. First, at the individual level, social capital has been defined as the resources embodied in its relationships with others. Emphasis is placed on the actual or potential benefits generated from a network of formal and informal ties of an individual with other members (Burt, Citation2000). Next, at the organizational level, social capital has been defined as the value created in an organization, in terms of relationships formed by its members, to engage in collective action (Freel, Citation2000; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). Finally, social capital was studied on a more global level in terms of its impact on the well-being of regions or societies (Putnam, Citation1993).

Consequently, the entrepreneur’s social capital is a construct that is the responsibility of his network of social relations. It is a process that evolves, resonating with the growth of the entrepreneur’s knowledge base and giving rise to an evolving number of external resources.

In the following, we will define the different measures for social capital.

2.2. Measurement of social capital

The measurement of social capital can be a difficulty regarding the different theoretical interpretations concerning an intangible factor. In examining the different approaches, there is a place to return to the context of our problem. We will use the concept of social capital to describe social resources in an entrepreneurial context in the agritourism sector. Social capital is made up of three dimensions: the structural dimension, the relational dimension, and the cognitive dimension (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). The structural dimension is the interpersonal configuration of individual relationships in a social network. It is characterized by the size of the network, the density, and the diversity of relationships in the network. The structural dimension of social capital allows the individual to develop and share collectively, with the other members of the network, common representations with which he identifies over time. The relational dimension refers to the nature of the personal relationships that develop between people and that manifest themselves concerning “strong” ties and “weak” ties. It helps build trust, standards, obligations, and identity among network members (Pelletier, Citation2014). These values, which lead to a lasting bond between individuals, influence individual behaviors such as cooperation, communication, and commitment to a common goal (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998). Trust between actors increases the chances for entrepreneurs to obtain relevant information and emotional support (Klyver & Schott, Citation2011). The cognitive dimension refers to shared visions, interpretations, and codes that allow network members to give meaning to information and to classify it in perceptual categories (De Carolis & Saparito, Citation2011). Since these shared representations and vision are written in the collective memory of network members, they can then anticipate and predict their actions more easily. Measurement social capital is not an easy task (Fornoni et al., Citation2012). The social capital literature presents an evolution of measurement models. The first was one-dimensional models, where the social capital of an agent was measured just in terms of its relative position in its social network and the properties that flow from it (Arribas & Vila, Citation2010). Other models have introduced other dimensions such as the relational dimension (Koka & Prescott, Citation2002) and the resource dimension (Fornoni et al., Citation2012).

2.3. The relation between social capital and social identity

Generally, social capital is developed based on reciprocal relationships such as trust, norms, and social networks between individuals (Yoon & Lee, Citation2019). Indeed, social capital presents itself as “the resources incorporated in its relationships with others. Emphasis is placed on the actual or potential benefits generated from a network of formal and informal ties of an individual with other members (Gharbi, Citation2020). People with a varied and expanded network of contacts have exclusively higher social capital and a more positive life than those with small and less varied networks. By investing more in social networks, individuals obtain standards on reciprocity and trust and have opinions and expectations that are positively convergent on people and life (Yoon & Lee, Citation2019). Social capital also functions as a resource available to individuals through social interaction (Lin et al., Citation2001). Social capital, however, refers to social networks that allow cooperation among members of the social community and argues that promoting coordination and cooperation results in an increased social network (Putnam, Citation1993).

Various links between two or more actors show that these relationships are dynamic and multiplexed (Gattiker & Ulhøi, Citation2001). From this observation, it can be explained that the exchange of advice and/or information, access to resources, etc., is the result of social norms and rules as well as social structure and individual power. In other words, these activities are affected by access to social networks and their relative position.

Generally, weak links are used for faster and shorter information exchanges and are defined by a weakness in the frequency of interaction. This is called “casual knowledge” and does not reflect friendships. However, as the frequency of interactions increases, these personal connections can become more powerful and strong (Nohria, Citation1992). A network relationship based on a weak link implies that respondents may not know each other personally (but may also know each other) and in this way, they form a basis for non-superfluous information.

Getting reliable advice and/or serious engagement with nodes in the social network is more necessary than simply getting quick access to new information. Indeed, the latter normally requires mutual trust.

In the literature, weak links have often been associated with the generation of ideas, while strong links are involved in problem-solving (Eisenhardt & Tabrizi, Citation1995; Hansen, Citation1999). However, the literature on innovation addresses the fact that close and frequent social interaction between groups and relevant internal functions during the internal development process improves the efficiency of the innovation process (Hansen, Citation1999).

To start or move forward in a knowledge-intensive enterprise, the entrepreneur needs capital, skills, axillary resources, and manpower. To realize them, the entrepreneur needs an important resource of social capital.

Previous research explains the role of social networks as a source of identity formation (Davis, Citation2014; Deaux & Martin, Citation2003). According to Deaux and Martin (Citation2003), social networks are used as a bridge between major social categories and interpersonal relationships. Previous research has stated that there is a relationship between social networks and social identity (Davis, Citation2014; Yoon & Lee, Citation2019). In other words, categorical social identities emerged in homogeneous social networks, while relational social identities present in social networks among heterogeneous groups of individuals. Indeed, the degree of homogeneity and heterogeneity of social networks affects the level of identity exclusivity (Lubbers et al., Citation2007). Besides, the components of social capital have a significant influence on identification: the greater the heterogeneity of social networks, the greater the tendency to get to know others (Yoon & Lee, Citation2019). For the authors Maya-Jariego and Armitage (Citation2007), they suggest that participation in new communities shrinks dependence on strong identities. Based on the review of the previous literature, we can judge that social capital is related to social identity. However, it has been noted that link capital, which is characterized by the homogeneity of the network, influences social identity (Liu & Chan, Citation2011). Briefly, if a person is closer to each other in their social network, he could more easily be determined with their social groups.

Now that we have presented the theoretical references of our main concepts as well as our understanding related to our problem, we will identify the different dimensions that will be studied in the context of our research. This will be the subject of the next chapter which presents the conceptual framework of research.

3. Research methodology

The primary goal of this publisher is to inform the relationship between social capital and social identity in the circumstance of agritourism entrepreneurship. Accordingly, the search epistemology has opted for a qualitative approach (Royer, Citation2016). However, the various case study of the approach allows us to make some generalized conclusions centered on our findings.

3.1. Research object

The social networks of the entrepreneur have special importance to rebuild the social identity of the entrepreneurs because it helps them in their strategic decision-makers. Also, to examine how the social capital helps and encourage in the development and reconstruction of the social identities of entrepreneurs and how it influences their behavior during the business process, we adopted face-to-face interviews with agritourism entrepreneurs. All these interviews operated in Tunisia which took between 30 minutes and 45 minutes each one and was recorded and transcribed. This study draws on the literature on social capital and the social identities of entrepreneurs. First, we study the concept of social capital on the agritourism entrepreneurial networks. Then, we combine its key features with the social identities of entrepreneurs. And on the other hand, we will examine how social identity contributes to the progression and development of the business in the agritourism field. Hence, while drawing on Walliman’s (Citation2005) approach, our work will be organized as follows: pre-analysis phase and data analysis.

3.2. Pre-analysis phase

3.2.1. Investigation procedure

The qualitative approach remains an essential step for the construction of our model. Qualitative studies generally lead to a generation of proposals. They also make it possible to explore new concepts and relationships related to the field studied (Andréani & Conchon, Citation2005). The objectives of this qualitative study are, on the one hand, to verify the research directions that have emerged in the literature review, and, on the other hand, to explore new aspects that may emerge in connection with our conceptual framework. It aims to explore the relationships between social capital and the social identity of the agritourism entrepreneur. Given our objective, we used a semi-structured interview to collect qualitative data allowing for adequate extraction of information from the field. The interview takes place according to a guide comprising leading questions which must be characterized by a relatively general and open aspect. Besides, the interview guide must bring out the central theme of research emanating from theory, the problem studied, and the flair of interviewing it (Romelaer, Citation2002).

These interviews—with three question headings—were addressed to the participants: (1) the benefit of social capital, (2) their social identities used when starting a business, and (3) their capacities to adapt their capital. social in the development of their identities.

The objective of this qualitative research as we presented previously motivates us to rely on the rule of “semantic saturation” to optimize the number of interviewees making up the sample (Evrard et al., Citation2000). On this basis, if two successive interviews no longer generate new information, the data collection ends.

3.2.2. Sampling

For the objectives of our research, we nominated a ten small- and medium-sized agritourism businesses, utilizing their business size as the major choice criterion. The convenience sample is selected while including 10 participants of Tunisian entrepreneurs belonging to the agritourism sector and having already started their businesses there is more than one year. This action took place concerning the criteria of socio-demographic diversity and structural relevance of the studied population and not its statistical representativeness. From where, each of the respondents was asked to recruit other subjects corresponding to the predefined criteria, until saturation. Table shows in detail the characteristics of the sample studied.

3.2.3. Selection of the corpus

Product content is provoked (Murray & Sage, Citation2018) from an interview guide developed to introduce research to participants, target the most appropriate profiles, and explore their social identities after the effect of their social capital. Interviews vary between 30 minutes and 45 minutes have been preferred given the possibilities of registration.

3.3. Assumptions proposals

3.3.1. The qualitative study between the new founders in agritourism

To help develop assumptions about the relationship between social capital and entrepreneurial identity, an exploratory study including interviews with ten entrepreneurs that started their new businesses was led. We have selected new businesses in agritourism which is evolving in response to augment the demand for the tourism experiences market (Alsos et al., Citation2014). As a developing area, the framework in which these new businesses are created, propose a little direction in terms of industry standards, recognized segments market, or a ready-made competitive analysis. Therefore, new businesses looking to suggest products and services for tourists who combine agriculture and tourism at the same time. Besides, it is a sector that draws both the entrepreneurs who perceive it as an opportunity to realize add incomes and the entrepreneurs that interested in other motivations, as an attraction to specific sorts of experiences. (historic heritage or cultural activities) or connected to the social objectives that help gainfully the development of the local community. From this effect, find several varieties of entrepreneurial identity (Di Domenico & Miller, Citation2012). As such, agritourism encourages the development of the social identity of the entrepreneur. Through this study, we selected new companies in the field of agritourism. All interviews were led on face-to-face, recorded on tape, and transcribed. Respectively, the interview was coded one by one and analyzed to recognize the entrepreneur’s identity and main behaviors. Subsequently, a cross-case comparison was performed to discover and analyze the relations. The potential relations recognized from the circumstances were then conferred based on the literature, and hypotheses were established based on an iterative procedure among the data analysis and theorization, that is, the following abductive reasoning (Klyver & Foley, Citation2012). Regarding the identity, six entrepreneurs were categorized:

An entrepreneur has been recognized as being primarily Darwinian (guest house). His elementary motivation is connected to the construction of his financial wealth.

Another entrepreneur was classified as primarily a communitarian (restaurant in a firm with a rounded club on horseback). Their basic motivation is related to the community to which it belongs, the bases of self-evaluation are the authenticity of this community and their framework of reference is associated with the community it serves (visitors).

Two companies were considered as a communitarian, in grouping with a certain missionary identity (guest house, green educational space for children). The bases social motivation stalks from idealistic ecological ethics related to the communities (children) and its involvement in the rural area. Their framework of reference is associated with the community of visitors (adults and children).

Two entrepreneurs were recognized as having a missionary identity (guest house and horse firm). The bases social motivation stalks from profiting the local community (guest house visitors) and educational objectives (horse fans) but also to the cheese producer community. Its framework of reference was related to the idealistic aims regarding the educational and beneficial characteristics and its bases of self-evaluation were connected to the progress and advance of the local community.

An entrepreneur has been recognized such as a person who has a missionary identity in grouping with a certain Darwinian identity (restaurant firm). Here, the bases of social motivation were replication, related to both an idealistic aim and an individual awareness in the formation of employment and profits. The bases of self-evaluation were linked to idealism.

Two entrepreneurs have been recognized by way of having a communitarian identity in grouping with certain identities of Darwinian (equestrian firm and guest house). Here, the bases social motivation was related to both contribute to the local community (young diploma and local people) and self-interest in creating more income.

4. Results and discussion

The objectives of this part of the qualitative study are, on the one hand, to verify the research directions that have emerged in the literature review, and, on the other hand, to explore new aspects that may emerge in connection with our conceptual framework. First, it aims to clarify the components of social capital by Tunisian entrepreneurs in the agritourism sector. This fieldwork plans, secondly, to check whether the dimensions of social identity mobilized in our research find a favorable response among the owner-managers of agritourism businesses and to distingue the manner that the different social identities identify distinct opportunities.

To perfectly achieve this delicate objective, we have chosen to deeply evoke social capital since this networking allows us to bring out the components of social identity. Finally, the study examines the exploration of the relationships of these two variables with the development of the agritourism sector.

The qualitative phase confirmed the importance of the three subcategories identified as a result of the entrepreneur’s expression of these experiences with his networking that influenced their identity as an agritourism entrepreneur: structural capital, relational capital, and cognitive capital.

4.1. Structural social capital

During the survey, certain interactive aspects related to the entrepreneur’s decision to launch his business that could refer to strong and direct links appear through the interviews of the respondents. In consequence, network-connected of social relationships offer information channels that diminish the time and effort obligatory to collect information. The awareness sharing is rather easy to attain and preserve when networks have solid relatives and direct links among their members. The comments of some respondents also highlight the role of social interaction in determining their behavior to start a business “I preserve nearby and solid social relationships with some members of the local community of this region”, “I communicate frequently They made things easier for me before the beginning of my project. ““I know most of the people here on a personal level since I lived my childhood in this area, right after when I grew up and I had my old job, I changed to the capital. Often here with my family to get away from everyday life and, I decided to start my project, the locals here helped me a lot and we welcomed the idea of this guesthouse with lots of encouragement””. Similarly, the importance of knowing other entrepreneurs to create a propensity for self-employment is very beneficial. The knowledge of specialists and professionals in agriculture and tourism and integrated into the social network could similarly be a strength that can simplify the identification and corruption of opportunities. For example, an interviewee said: “My friend knows a man who already works in tourism … and we met … after a long discussion, he helped me by certain places and gave me some contacts if I need it”.

In rural areas of Tunisia, people with close relatives or certain friends who work as village representatives and have knowledge about the creation of projects in these areas. For example, these village representatives are well informed about government policy and regulation. Moreover, they have the richest management experience between the locals. The excerpt from the speech of some interviewees shows it. “I know the” 3omda “here, and he showed me the necessary papers to start a project”, “the difficulty in the launching of a project is the regulatory papers, but the head of this village facilitated my tasks.”.

4.2. Relational social capital

Relational social capital has emerged as an emotional feeling in the relationships between individuals facilitating the exchange of knowledge. Indeed, relational capital exists when individuals identify strengths and trust a network. Trust is an imperative antecedent of collaboration, resource achievement, and sharing of awareness between persons. In the literature, some researches (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003; Zhao et al., Citation2011), identified trust as a component of relational social capital. This variable was clear in speeches; that is mean that the entrepreneur built his decision based on the trustworthiness of his/her networking. However, following the thematic analysis, Trust is implicitly built out in speeches related to Relational social capital and the exchange of information. Besides, when relationships are highly trustworthy, persons are more enthusiastic to involve in social and supportive exchanges and interactions. The excerpt from the speech of some interviewees shows it. “I have total trust in my relatives and friends”, “… for me building strong relationships with the local community is more profitable and profitable in terms of time and money”. Interpersonal trust is important to create an atmosphere conducive to knowledge sharing. Respondents expressed their trust in their networking throughout a project and it appears more important in some verbatim. “I’m trying to jump into the project or change another direction”, “… Yes, what others are saying and I’m proposing, is of great importance to me … makes things easier for me and allows me to save a lot of time “. In terms of the benefits of information, strong links are more advantageous to the transmission of detailed information and implicit awareness. From the time when a piece of good information and implicit awareness cannot be simply codified or understood, their transmission principally necessitates close and recurrent connections. And therefore, it can be argued that the strength of the relationship has a more direct effect on the transmission of resources. From this effect, identification appears to be a very important process in the responses of some interviewees. Persons perceive themselves as grouped with another individual or a group of individuals and maintain a strong relationship with them. Here is an example of verbatim: “The period before the launch of my project, I needed some advice, some information, … and oh!!! I got them by contacting my networking …” have received full help and exchange information about the project, competitors, pars, too, a friend offered me contact with an investor “. Social capital is also enabled by a solid sense of exchange: favoritisms given and received and a solid sense of equality. The verbatim of the interviewees confirm it: “I like shared with others my knowledge because some of them also helped me in the launch of my business”, “it’s just a give-and-give”, “when I do not find the correct information or when I find a lack in my bank account for the project, I ask for help to my relatives, and I know they will help me … and it will be the same when someone of them will need my help. “.

4.3. Cognitive social capital

We found that cognitive social capital for launching agritourism projects is essentially expressed by entrepreneurial participants. Besides, cognitive social capital has highlighted the difference between individuals, language, and shared codes. To increase the opportunities for understanding among members, it is better to have mutual knowledge by allowing them to express their knowledge freely. The cognitive dimension encompassed by the parties not just to create a fruitful relation, but also to develop the mental presence of both parties. These respondents mention “My family and friends boost me to become autonomous”, “… In the beginning, When I started my startup, my family, my friends, my colleagues in my work told me that I’m crazy to launch Now, I see they are proud and encourage me all the time. “ Shared codes and language simplify the mutual understanding of collective aims and how to act in local communities. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) have stated that language sharing effects in many ways the conditions of intellectual combination and exchange. Shared language makes it easier for people to contact other people and to their information. Second, shared language offers a common conceptual apparatus for evaluating the expected profits of exchange and combination. Finally, shared language also denotes the knowledge of connection. It improves the ability of the diverse parties to combine the knowledge attained through social exchanges. The comments of some respondents also highlight the role of the sharing vision in communication with their networking: “To understand the local community of this area, it is necessary to use their languages and not that of capital or professionalism that I have used in my old job and with my directors … “,” You cannot work without a balanced communication with your surroundings “. Likewise, cognitive social capital embodies the collective aims and aspirations of the members of an organization through a shared vision. Indeed, it is considered as “a liaison mechanism that supports diverse parts of the organization to integrate or combine resources” (Tsai & Ghoshal, Citation1998, p. 467). As a result, members of like-minded organizations will be more expected to be partners in sharing or exchanging their resources. In the case of agritourism businesses, local communities, and the networking of the individual form groups that share common interests and goals. The results obtained fit well with Cohen and Prusak (Citation2001). From this, they approve that shared values and objectives fix the members of networks and human communities and facilitate cooperation and better knowledge sharing, in terms of quantity and quality, and ultimately help to achieve the project. For example, an interviewee said: “… since we have the same interest in promoting our region, the community here helped me a lot at the beginning of the launch phase of my project”, “in parallel with my personal goal, I wanted to make my old region a famous destination that people from different countries or city come to visit … And that helped me a lot at first because the people here appreciated the idea of promoting our region”.

4.4. Relationships between social capital and social identity

Entrepreneurs must or still want to differentiate themselves from other members of society. Indeed, they fundamentally affirm the psychological necessity to belong to the group. Basing themselves on the theory of social identity, people define themselves as a person who identifies with an internal group that their features are completely dissimilar from an external group. In other words, by belonging to an internal group, people integrate the positive attributes such as the success and status of the internal group by comparing them to the perceived negative features of the external group, which leads to an increase in their esteem and their effectiveness. As such, members of social groups rate activities according to their conformance with their identity prototype, making them more likely to engage in most appropriate activities. The social identity of the individual develops throughout their life from their childhood and will be constantly changed and reassessed during their lifetime. According to the interviews of our study, we took three types of relative social identity for Tunisian agritourism entrepreneurs and which are confirmed with the research of Sieger et al. (Citation2016).

As a result, the social identity of entrepreneurs effects the category of opportunity that they exploit, the strategic decisions that they reflect suitably, and the sort of value that they create. From this observation, the analysis of the social identity of the entrepreneur can shed light on an unexplained variance in the process of starting up a business. The social motivation of entrepreneurs, their self-evaluation, and their reference group which all shape their social identity and create three diverse forms of social identity: Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries.

4.5. The social capital and Darwinian identity

The Darwinian identity accounts for the “classic entrepreneur” identity who has the elementary objective of starting a solid and fruitful business. For the Darwinians, competitive businesses and other Darwinians are the reference framework and the social group against which they evaluate themselves. For example, an interviewee said: “I create my firm to make money because on our days and especially after the revolution, in Tunisia, to stay in your job without any other income, it makes life difficult. Also, I want to be an owner business and advance my career as an agriculture engineering in the world of business. My family supports me with my decision … and this is a support for me … they help me morally, money, networks … and now, I think that I took the right decision to launch my cottage in this area … my business shows a growth success near the visitors”.

For these categories of entrepreneurs, the industry where they exploit, the markets that they provide or the most social cause support relatively little meaning or nothing. Therefore, provided more profits and improved opportunities for accomplishment, they might flip and commit to new businesses. Entrepreneurs with a predominantly Darwinian identity focus on the profitability of their businesses and personal profit. In other words, they give most of their attention to the activities designed to guarantee the success of their businesses. This objective orientation is equivalent to the principle of causality, which will take the ends as a base to act and basis judgments on the assessment of anticipated returns. The verbatim of the interviewees confirms: “… my ambitions are quite high. We are in the agritourism market, and from everywhere we are visiting and enjoying the ambiance”, “ To be successful, my business reveals a successful financial performance compared to my competitors”. Darwinian entrepreneurs rely on their social capital to get into the business. This is confirmed in some verbatim: “My family supports me on my decision … and this is supportive of me … they help me morally, money, networks … and now, I think that I took the right decision to launch my cottage in this area …,” to me, the success of most of the businesses started by your networks”.

The results obtained agree well with the variables mentioned in the literature and presented in the conceptual model previously proposed. Besides, the analysis identified a new variable that seems specific to the Tunisian context, namely “ Personality traits specific to entrepreneurship”.

General traits (namely: openness to experience, being conscientious and emotional stability, the need for accomplishment, the tendency to innovation or inventiveness, a proactive personality style, a global feeling self-confidence or self-efficacy and tolerance for stress, the need for autonomy) are not only the most suitable factors for predicting behavior or performance in a specific field such as entrepreneurship. Our analysis of the interviews revealed the entrepreneurial traits of Tunisian entrepreneurs, namely: Entrepreneurial Orientation. This factor indicates the degree to which the managers of a company display an entrepreneurial spirit. This concept is broken down into 3 factors: the trend towards innovation, risk-taking, and proactivity. The excerpt from the speech of some interviewees shows it. “it’s a new field of battle that deserves to discover it”, “Being an entrepreneur means taking risks”, “In any case, you are challenged every morning”, “I, in five years, I had to arrive two or three mornings with peace of mind in this business, therefore, every morning you are called into question on your forecasts, on your vision of things, therefore, it takes the spirit of the initiative”, “I prefer to go ahead and discover new ideas, new battlefields to dig into”.

4.6. The social capital and communitarian identity

The Communitarian identity can be elaborated according to the motivation of hobbies or leisure interests in a business to maintain a group of similar-minded persons. These respondents mention “My grandfather has owned this farmhouse for many years … It is my main motivation to reconstruct it while maintaining the old charm and traditional things in this house … It is very important for me and for the visitors to exchange stories related to this house showing them some pictures that remember the history of this treasure”.

Community identity can be developed based on the motivation of the hobbies or leisure interests of a company that wants to maintain a group of similar-minded people. In this case, building a trustworthy identity is essential to being part of the social group, sharing the intimate skills and competencies of the community, and serving it from within. The excerpt from the speech of some interviewees shows it. “The first time, before we start our business, we think about making money and our farmhouse, but we are going to have a good time. the visitors are looking for a place to eat in the area … the place to taste our traditional food, beautiful nature … the local community here farmhouse, they also helped us to start their business with their knowledge, information, friends …“,” that’s what I wanted to do for a long time …”. For communitarians, it is not important to change the sector; in return, they may be innovating new, more powerful directions to aid the group. This meaning is nearby to the concept of the “entrepreneurial user” suggested by Shah and Tripsas (Citation2007). In their definition, they introduced users as entrepreneurs who come across an idea through their use and then share it with their community. Besides, the process contains a cooperative creative activity before business creation within the user community. Some interviewees confirm it: “I have owned this farmhouse many years ago … a few years ago, a thought has progressed that when I withdraw, I will be the owner of my business … today, I am achieving my dream”.

Community identity presents their entrepreneurial activities such as indispensable for community progress. “My main motivation for this business was to offer a new product for our customers that they did not get it before”. This interviewee is based on his welfares in local heritage and traditional handmade, wishing to interconnect with them to a wider community. From this observation, this motivation on products and business development founded on self-interest is corresponding to effective behavior based on the starting principle of knowing self and not focusing on the end goal. Entrepreneurs who specialize in a community identity were focusing on what their networks could offer for them, especially, while developing their projects. They sought to retain the flexibility to develop ideas based on the opportunities, and they cooperated with others to further develop opportunities. The excerpt from the speech of some interviewees shows it. “People like to tell others … So, I started with a word of mouth to make known my cottage.” Now, they came to accommodate in my house and taste my tradition food “,” Through the contact with the local community, I knew what I wanted to do in this business … I knew what I wanted to start my business “,” … I believe that if you know the people already, then I’m sure it’s a lot easier to get you up and running, that’s getting results very quick “,” Our first customers are coming from here”.

An entrepreneur who has social orientations, therefore, puts more chances on his side. Social orientations refer to the ability to correctly perceive others, to express emotions and opinions clearly, to be convincing, and to create a good impression (confidence, seriousness …). These social orientations as an entrepreneur with a community identity allow both to build up significant relational capital, but also to extract useful resources (advice, help, money, time …) from his social network. Besides, the more social orientations increase, the more the financial success of a business increases (Baron & Markman, Citation2003).

4.7. Social capital and missionary identity

The missionary identity that motivated starting with a business to advocate for a better reason and to act responsibly is considered essential. Consequently, their motivation is strictly related to social entrepreneurship, and studies focused on the identity of social entrepreneurship. According to Jones, Latham, and Betta (Citation2008), individuals committed to a social entrepreneurial identity must differentiate themselves from Darwinians and decline their proximity to for-profit identities. Therefore, it can be just as essential that missionary identity builds its identity according to the social cause of entrepreneurs and differentiates itself from other types of identity. Therefore, the foundation of identity is not only “who I am” but also “who am I not?” The comments of some respondents also highlight the role of missionary identity for social development: “Many people go to my farm to educate about horses and make a tour around the village.”, “My principal motivation is to open my cottage on the farm, I can pursue values that are essential to me or special cause (for example, social, sustainability, …).

Entrepreneurs with a missionary identity come to the fore based on their deep convictions towards their companies, which represent a vector of social change towards society. They see their businesses such as a platform from which they can continue to develop their societal goals. This objective positioning is not based on profit or predictable return, but it can always be said that they adopt the principle of causality to take the end as a base for the act. The interviewee’s answer confirms this: “To us, our green cottage can contribute to change many bad habits and to make some places better to consume”. Its missionary identity based on the organic way of life and the local contribution encouraged to give a clear vision of the ultimate form of the company This objective was at the center of his concerns when he started to create their business in agritourism. ” I want to convince them that it is what I’m looking for and what I’m dreaming about … A farmhouse in the middle of my firm … Now, many visitors to my cottage come to relax and to change the place of everyday life and also to make the tour around the village … which encourages the development of the region and transforms it to the best “, “to open a cottage on the agriculture firm, both ministries of tourism and agriculture oblige for some criteria as the cottage does not spoil the base of agriculture land”. On this basis, we maintain that the missionary identity of entrepreneurs is based on the collective goals of society. Indeed, their decisions will be made according to the societal community. The verbatim of the interviewees confirm it: “Of right! We must think about earning money, but we have other viewpoints also … we can be atypical as a business since there is so much idealism in it”, “It is a distinct venture. If you do not comprehend it, you will think it is working … we could change the city … with the community of our region, we will create a new different picture”, “… that’s what we like and then that’s what we can do. And always with a social purpose”.

We recognize that one entrepreneur can have hybrid identities occur and may even be shared. Some verbatim confirm it: “It is not just a business for money, there are these types of firms everywhere in many different places. To me, it is to deliver goods and services with high quality to our customers and to help them to live an unforgettable experience. For me, it is also better to be able to work your own business ‘,’ Through the contact with the local community, I realized there was an opportunity to get into this business … I knew what my local community wants to react to this place … I am sure that you will be able to start your business. Our first customers who came to consume our service was from the relative of our neighbor … So, I started with the word of mouth … from everywhere, they came to taste my traditional food ‘,’ Here, to live a new experience and to be able to do what we truly need the best. What is the motivation behind our business? How do you go about it? … Discover new things different than a hotel, it is a challenge”, “For us, the green concept is the most important … we care about the future of our children … we want to create a green life … To be healthy in their mind and their behavior. To us, we are going to make our business better.”.

Hybrid identities can be influenced by social capital, which can lead to mixed approaches or ambiguous behavior. Given the difficulty of testing these hybrid identities in the future, our assumptions focus on the social capital effect on one type of identity at a time without excluding the influence of other potential identities.

The contribution of this work compared to previous research is the consideration of the effect of social capital on entrepreneurial social identity. It aims to show the importance of this concept as an analytical framework for integrating the social aspect into the social identities of entrepreneurs. In the process of creating an agritourism business, it will be appropriate to help the founders to build relationships with communities in the region, associations of entrepreneurs and organizations that support business creation. Characteristics of relationships established with entrepreneurs (number, diversity, intensity), creation and participation in associations related to entrepreneurship, support for family members and friends in entrepreneurial activities carried out by entrepreneurs during their creation process, can contribute to the development of significant social capital. These elements can constitute indicators of the social identity of entrepreneurship in the agritourism sector.

On a theoretical implication, the concept of social capital has been grasped on the one hand, both in its static and dynamic aspect and on the other hand according to the objective and subjective approaches.

We have found in the literature a multitude of indicators for measuring social capital, and therefore we have selected those that are most relevant in terms of our research objectives. On the managerial implication, with the development of the agritourism sector and the increase in the number of businesses in it in the Tunisian context, a longitudinal study seems to be interesting to see the influence of social capital on the social identity of the agritourism entrepreneur. In this observation, our qualitative study highlighted the importance of training for the entrepreneur. Indeed, the importance of training for the development of agricultural tourism should not be underestimated, because the integration of tourism with the farmer obliges the producer to have completely new skills for him; marketing, reception, catering, presentation and explanation of heritage, management of visitor flows, promotion of festivals and other events, conversion of buildings and strategic planning of rural tourism.

Social capital is a strategic tool for the development of a business, to grow or anticipate difficulties. To meet this challenge, it is better to educate the entrepreneur by focusing on training in the field concerned. There are three points to focus on. First, the identification of the stakeholder to be trained. Training in the agritourism sector does not only concern agricultural producers, but also employees, specialists, community and cooperative groups and trainers. It is necessary to study the needs of each of them to offer them the most suitable training programs. Second, training programs must provide several benefits by helping to empower all stakeholders. Essentially, training is needed to help businesses become more efficient and profitable by encouraging better marketing, better organization and cooperative work, and allowing tourists to return for new stays. Third, the choice of the organization that will develop and execute the training program.

5. Conclusion

This article raises the interest of studying the role of social capital in rebuilding the different social identities of the entrepreneur in launching a business in the agritourism sector. This concept is an intrinsic and extrinsic force for the entrepreneur by developing the different types of social identity that can reincarnate it when launching a project. social capital helps individuals to maintain a strong relationship with others. Social capital is very important because it allows people to come together in groups for development. The perspective of social capital which adopts that resources ingrained in social relations can be organized to support entrepreneurship should provide a more whole clarification of the phenomenon and exposition of new information that allows the success of business development in the future. Indeed, social capital can act on the re-construction and development of the social identity of the entrepreneur to help him in the development of their business. Since social capital plays a decisive role in the formation and development of community-based ecotourism entrepreneurship (CBEE). This will in turn help to explore how social capital influences the decision-making ability of the entrepreneur and thereby reinforces their identity. Although some entrepreneurs have started in the agritourism sector, most of the businesses in this sector are still doing so. From a managerial point of view, our research will help agribusiness entrepreneurs to develop their networks to have more confidence during their launch and after projects in the agritourism sector. This research also helps the governorates and all actors have developed and improved this new sector by helping agribusiness entrepreneurs in their projects and by giving more facilities to them.

6. Limitations and future recommendations

This study helped us to better understand the effect of social capital on the development of the social identity of the agritourism entrepreneur. However, it is not exempt from a few limitations which open interesting avenues of research. First, it concerns the validity of the proposed model based on exploratory work, and thus limits the exploitation of the theoretical effects. From an empirical point of view, future research could develop suitable measurement tools to assess the role of social capital in the development of entrepreneurial social identity. It would thus be interesting to empirically validate the theoretical structure that we have advanced in Figure . This is even more relevant as this kind of tool would help managers to identify failures at the level of their program, to target their communication, and to segment their customers. Besides, a better understanding of these two levers: social capital and social identity will be achieved, in our opinion, if we consider education and training programs of the entrepreneur concerning the context of agritourism. A second concerns the failure to consider the variables of empowerment and communication in qualitative analyzes that may lead to differences in the relationships between the categories explored. Note, for example, the effect of age on behavioral experience and the effect of sex on the management of negative emotions. These factors can influence the social capital effect on the reconstruction of the entrepreneur’s social identity, more specifically, the choice of the appropriate identity with the decision to launch their business and thus constitute new horizons of research. The study of social capital and the identity of the entrepreneur in the new sector agritourism suffering from poor surveillance has opened avenues of research that allow validating its important role in the behavioral change of the entrepreneurs in the field. agritourism businesses. The components and consequences of this concept are discussed in this exploratory part. Further questions arise as to the validity of this multidimensional construct and its results in adopting and maintaining a contractor’s behavior.

Highlights

This article aims to understand the development of agritourism businesses by focusing on the role of social capital and the social identity of an entrepreneur. To achieve our objective, an exploratory qualitative study is carried out with a sample of 10 agritourism entrepreneurs who were farmers, or who started businesses in this area. To do this, a large amount of documentation was examined, and semi-structured interviews were conducted and analyzed. The results revealed that social capital helps strengthen the social identity of entrepreneurs when launching their business. According to this observation, a conceptual model has been proposed to test this relationship in the future.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nesrine Khazami

Nesrine Khazami is a research scholar in Business and Management at the University of Szent Istvan, Hungary. She did her post-graduation in Master Marketing from economics sciences and management University, Tunisia. She has been in academics for 3 years. Her research interests are a destination, tourism management, tourism marketing, and social psychology of tourism.

References

- Alsos, G., Eide, D., & Madsen, E. (2014). Introduction: Innovation in tourism industries. ( G. A. Alsos, D. Eide, and E. L. Madsen ed.). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Andréani, J., & Conchon, F. (2005). Fiabilité et validité des enquêtes qualitatives. Un état de l’art en marketing. Revue Française du Marketing, 201, 5–17. http://www.escp-eap.net/conferences/marketing

- Arribas, I., & Vila, J. (2010). Guanxi management in Chinese entrepreneurs: A network approach working paper. BBVA Foundation. http://www.fbbva.es/TLFU/dat/DT_8_2010.pdf

- Baron, R., & Markman, G. (2003). Beyond social capital: The role of entrepreneur’s social competence in their financial success. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00069-0

- Beyers, T., Kist, H., & Sutton, R. I. (1998). Characteristics of the entrepreneur: Social creatures, not solo heroes. ( (Dorf, R.C. ed.). (T. T. Handbook, Ed.)). CRC Press/IEEE Press.

- Burt, R. (2000). The network structure of social capita. Research in organizational behavior, 22, 345–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/11652.5296

- Che, D., Veeck, A., & Veeck, G. (2005). Sustaining production and strengthening the agritourism product: Linkages among Michigan agritourism destinations. Agriculture and Human Values, 22(2), 225–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-004-8282-0

- Cohen, D., & Prusak, L. (2001). In good company: How social capital makes organizations work. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

- Davis, J. (2014). Social capital and social identity: Trust and conflict. In A. Christoforou & J. Davis (Eds.), Social capital and economics: Social values, power, and identity. Routledge. https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1407&context=econ_fac

- De Carolis, D., & Saparito, M. (2011). Social capital, cognition, and entrepreneurial opportunities: A theoretical framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00109.x

- Deaux, K., & Martin, D. (2003). Interpersonal networks and social categories: Specifying levels of context in identity processes. Social Psychology Quarterly, 66(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519842

- Di Domenico, M., & Miller, G. (2012). Farming and tourism enterprise: experiential authenticity in the diversification of independent small-scale family farming. Tourism Management, 33(2), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.007

- Eisenhardt, K., & Tabrizi, B. (1995). Accelerating adaptive processes: Product innovation in the global computer industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(1), 84–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393701

- Evrard, Y., Pras, B., & Roux, E. (2000). Market- études et recherches en marketing (2ème ed.). Nathan.

- Fauchart, E., & Gruber, M. (2011). Darwinians, communitarians, and missionaries: The role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Academic Management Journal, 54(5), 935–957. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0211

- Fornoni, M., Arribas, I., & Vila, J. (2012). Measurement of an individual entrepreneur’s social capital: A multidimensional model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(4), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0204-1

- Freel, M. (2000). Do small innovating firms outperform non-innovators? Small Business Economics, 14(3), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008100206266

- Gattiker, U., & Ulhøi, J. (2001). Entrepreneurial phenomena in a cross-national context (2 ed.). Marcel Dekker.

- Gharbi, M. (2020). Les Dimensions du capital social et l’intention entrepreneuriale des étudiants. Creating global competitive economies: 2020 vision planning & implementation, 590-601. https://www.academia.edu/11319594/Les_Dimensions_du_capital_social_et_l_intention_entrepreneuriale_des_%C3%A9tudiants

- Groen, M. (2005). using dialogues with customers as sources of knowledge. Accounting Finance and Management, 12(4), 291–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/11202.9504.

- Hansen, M. (1999). The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667032

- Jones, R., latham, J., & Betta, M. (2008). narrative Construction of the Social Entrepreneurial Identity. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 14(5), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550810897687

- Klyver, K., & Foley, D. (2012). Networking and culture in entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(7–8), 561–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.710257

- Klyver, K., & Schott, T. (2011). How social network structure shapes entrepreneurial intentions? Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 1(1), 3–19. http://ent.ut.ac.ir/jger/images/userfiles/1/file/pdf/kim%20kliver%201.pdf

- Koka, B., & Prescott, J. (2002). Strategic alliances as social capital: A multidimensional view. Strategic Management Journal, 23(9), 795–816. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.252

- Lin, N., Cook, K., & Burt, R. (2001). Social capital: Theory and research. Transaction Publishers.

- Liu, N., & Chan, H. (2011). A social identity perspective on participation in virtual healthcare communities. Thirty second international conference on information systems, Shanghai.

- Lubbers, M., Molina, J., & McCarty, C. (2007). Personal networks and ethnic identifications the case of migrants in Spain. International Sociology, 22(6), 721–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580907082255

- Maya-Jariego, I., & Armitage, N. (2007). Multiple senses of community in migration and commuting the interplay between time, space, and relations. International Sociology, 22(6), 743–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580907082259

- Murray, M. (2018). Narrative data. In Sage (Ed.), Narrative psychology (pp. 264–279). Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Michael_Murray3/publication/321949516_Narrative_data/links/5a4bb5740f7e9b8284c2dba1/Narrative-data.pdf

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533225

- Neergaard, H. (2005). Networking activities in technology-based entrepreneurial teams. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 23(3), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242605052073

- Nohria, N. (1992). Information search in the creation of new business ventures: The case of route 128 venture group. Harvard Press.

- Pelletier, L. (2014). Portrait du capital social entrepreneurial dans le secteur agroalimentaire en abitibi- témiscamingue. Université du Québec.

- Powell, E., & Baker, T. (2017). In the beginning: Identity processes and organizing in multi-founder nascent ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 60(6), 2381–2414. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0175

- Putnam, R. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 13, 35–42. http://staskulesh.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/prosperouscommunity.pdf

- Roman, M., & Golnik, B. (2019). Current status and conditions for agritourism development in the Lombardy region. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 25(1), 18–25. https://www.agrojournal.org/25/01-03.pdf.

- Romelaer, P. (2002). Notes sur l’entretien semi-directif centré, CEFAG, Méthodes qualitatives de Recherche en gestion, La Londe Les Maures.

- Royer, C. (2016). De prudence et d’imprudence en recherche qualitative. Recherches Qualitatives, (20), 594–599. http://www.recherche-qualitative.qc.ca/documents/files/revue/hors_serie/HS-20/rq-hs-20-royer.pdf

- Shah, S., & Tripsas, M. (2007). The accidental entrepreneur: The emergent and collective process of user entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1–2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.15

- Sieger, P., Gruber, M., Fauchart, E., & Zellweger, T. (2016). Measuring the social identity of entrepreneurs: Scale development and international validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(5), 542–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.07.001

- Simon, F., & Tellier, A. (2013). Comment développer le capital social des intrapreneurs? Revue Française de Gestion, 4(233), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.3166/rfg.233.123-140

- Tsai, W., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital and value creation: The role of interfirm networks. Academy of Management Journal, 41(4), 464–476. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/30254013/tsaighosal.pdf?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DSocial_capital_and_value_creation_The_ro.pdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A%2F20191008%2Fus

- Ulhøi, J. (2005). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. Technovation, 25(8), 939–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.02.003

- Walliman, N. (2005). Your research project: A step-by-step guide for the first-time researcher. 2nd ed. Sage.

- Wry, T., & York, J. (2017). An identity-based approach to social enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 42(3), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0506

- Yoon, S., & Lee, E. (2019). Social and psychological determinants of value co-creation behavior for South Korean firms A consumer-centric perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 31(1), 14–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-01-2018-0017

- York, J., O’Neil, I., & Sarasvathy, S. (2016). Exploring environmental entrepreneurship: Identity coupling, venture goals, and stakeholder incentives. Journal of Management Studies, 53(5), 695–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12198

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J., Jr, & Chen, Q. (2011). Reconsiderer Baron et Kenny: Mythes et verites a propos de l’analyse de mediation. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 26(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/076737011102600105