Abstract

South Africa has a high incidence of HIV. Violence in the country is also high and often perpetrated by dating partners. Dating violence can make it difficult for partners to negotiate safe sex practices. Moreover, the field of interpersonal violence is changing as social networking sites redefine interpersonal boundaries. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined the influence of cyberbullying on safe sexual practices. This study investigates the relationship between cyberbullying, physical violence and sexual behavior (i.e., condom use and number of sexual partners). A cross-sectional study was conducted among students at a South African university. Only 28.5% reported using a condom at every sexual intercourse during the last 3 months. Cyberbullying was reported by 76.2% of respondents. Physical assault from an intimate partner was endorsed by 50.6% of respondents and 42.2% perpetrated physical assault on a dating partner. Both victims of cyberbullying and dating violence as well as perpetrators of dating violence reported lower condom usage. There was an inverse relationship between cyberbullying and the number of sexual partners. It is concluded that high levels of cyberbullying and intimate partner violence are present among students and that these are linked to low rates of condom use.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

A country with both high HIV and violence rates, South Africa provides an ideal setting for studying the interrelationship between violence and sexual risk behaviors. The increasing use of social media among young people is changing the field of interpersonal violence, with cyberbullying becoming common. This study was conducted among students attending a tertiary education institution in South Africa to investigate whether cyberbullying and dating violence affect condom use. Three-quarters of tertiary education students experienced cyberbullying while half experienced physical dating violence. Almost half also perpetrated dating violence. Victims of cyberbullying had lower condom usage. Dating violence victimisation and perpetration were also associated with lower condom usage. We conclude that high levels of cyberbullying and intimate partner violence are present among students and that these are associated with low rates of condom use.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Background

South Africa has the highest prevalence of HIV in the world with 6.4 million people living with the infection, representing 18% of the global burden (Shisana et al., Citation2014). Young people are at particular risk as 12% of South Africans aged 15–24 years are living with HIV (Giorgio et al., Citation2017). Many factors play a role in the transmission and prevention of HIV. Goal one of the National Strategic Plan (NSP) of South Africa is to reduce new HIV infections by 2022 [South African National AIDS Council (SANAC, Citation2017)]. In order to achieve this target, preventative measures that are currently in place must be utilized by those at risk of HIV infection. Consistent condom use has shown to decrease HIV transmission by 80–90% (Halperin et al., Citation2004; Potts et al., Citation2008). However, the use of condoms among young people, in South Africa is generally low (Haffejee et al., Citation2018), with the resultant increase in HIV infection, particularly among women (Haffejee et al., Citation2016; Osuafor & Mturi, Citation2014).

Risks for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been linked to violence, particularly sexual assault, in southern Africa (Garcia-Moreno & Watts, Citation2000). Gender-based violence may make it difficult for partners to negotiate safer sexual practices such as using condoms consistently. Women in abusive relationships, for instance, may feel powerless to negotiate safer sex or condom use, due to fear of their partner’s response. As a result, their reports of condom use when sexually active are low and they have a higher prevalence of STIs than women in non-abusive relationships (Haffejee & Maksudi, Citation2020; Kalichman et al., Citation1998; Vetten & Bhana, Citation2001).

Violence per se is very high in South Africa, which compared to the rest of the world has a 4.6 times higher rate of interpersonal violence resulting in death (Seedat et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, a study found that a quarter of South African women had previously been physically abused by a partner (Jewkes et al., Citation2003). Another study conducted in Tanzania and South Africa reports that up to 42.8% of adolescents had been victims or perpetrators of dating violence (Wubs et al., Citation2009). Dating violence amongst adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa is high, with more than a third reporting violence by their partners (Wubs et al., Citation2009). Youth with dating violence experience are at risk for negative health consequences, which affect both physical and mental health. Youth who experience dating violence (victimization or perpetration) are more likely than non-exposed peers to engage in unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol, tobacco and drug use (Black et al., Citation2011).

Moreover, the field of interpersonal violence is changing as new technologies redefine interpersonal boundaries. Electronic communication with cell phones and social networking sites has provided a virtual space in which to communicate but could also be used to engage in unfavorable and often harmful behavior such as cyberbullying (Piccoli et al., Citation2020). Electronic communications can be used in arguments, monitoring of activities and perpetration of emotional as well as verbal aggression (Draucker & Martsolf, Citation2010; Sullivan et al., Citation2010). In addition to such harassment, it could also be used to exclude a peer from a group or impersonate someone by taking over their profiles (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, Citation2019). Experiencing cyberbullying is associated with anxiety, depression, behavioral problems, low self-esteem and peer rejection (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, Citation2019). Peer pressure often promotes cyberbullying behaviors (Hinduja & Patchin, Citation2013; Sasson & Mesch, Citation2017) and adolescents often expect the peer group to condone cyberbullying, which in turn intensifies such behavior (Hinduja & Patchin, Citation2013). To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined the relationship between cyberbullying and condom use, which is an important means of HIV prevention.

According to the socio-cognitive theory, which is widely used for studying HIV prevention among young people, behavior is determined by the interaction between the personal (cognitive component), behavioral and social components. The cognitive component refers to the individual’s confidence in performing a task. The behavioral component includes the skills that are required to obtain a desired outcome, which in the case of HIV prevention would include skills to manage interpersonal interactions for protection against sexually transmitted infections. The social component involves aspects of the environment that influence certain behaviors and encompasses the social consequences of a behavior. Activities can be learnt by observing how other people belonging to the same social sphere behave and the consequences of such actions. Accordingly, young people whose friends use condoms would be more likely to do so themselves (Espada et al., Citation2016). This model has previously been used as a theoretical framework to assess condom use amongst high-risk groups such as adolescents (Jemmott et al., Citation1992; O’Leary et al., Citation1992).

It is unknown whether social networking over cyberspace would provide an environment that influences sexual behavior with or without condoms. Against the backdrop of the social cognitive theory, it is hypothesized that negative social behavior such as cyberbullying would negatively influence condom use.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between cyberbullying and condom use. It also compares the effect of physical violence on condom use and the relationship between cyberbullying and physical violence among young people. Findings from this investigation will expand on the literature of psychosocial factors that impact on the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, in particular HIV, among young South Africans.

2. Methods

After obtaining ethical clearance (REC 73/16), a cross-sectional study was conducted among students registered for full-time study at a tertiary educational institution in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Data were collected by means of a self-administered questionnaire, which formed part of a larger study. Details of sampling and the questionnaire were reported previously (Corona et al., Citation2019; Haffejee et al., Citation2018) All participants were living at the residences of the university. From the total of 15 student residences, at the university, seven residences were randomly chosen for the research project. Subsequently, students were randomly selected from different years of study. Participation was voluntary. After an initial verbal explanation of the study, written information was provided to those interested in participating. Signed consent was obtained prior to answering the questionnaire, which took approximately 45 minutes to complete.

The questionnaire was adapted from previously established questionnaires to suit the local context (Bennett et al., Citation2011; DiClemente & Wingood, Citation1995; Foshee & Langwick, Citation2010; Hood & Shook, Citation2013). The questionnaire was validated by an expert group and subsequently piloted with five students, who met the inclusion criteria and were later excluded from the main study.

The questionnaire comprised questions to obtain demographic characteristics and data on sexual history. It also included questions on condom use, dating violence and cyberbullying. All questionnaires were provided in English, which is the language medium of the university.

For the purpose of this study, the frequency of condom use in the last 3 months was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “never used a condom” to “used a condom at every sexual act”. This measure was dichotomized prior to conducting regression analysis to a yes/no option for having used a condom at every sexual act in the last 3 months. Cyberbullying was measured using 22 items from a previously validated questionnaire (Bennett et al., Citation2011). Sample questions included: In the last year a dating partner (1) sent me a mean or hurtful text message; (2) Bullied me through text messaging. All items are listed in Table . These items were summed for a total score, with higher scores indicating receiving more cyberbullying.

Table 1. Experience of victimization through cyberbullying from an intimate partner

Experience of any form of physical assault was measured using 16 items. Sample questions included: How many times has any person that you have been on a date with, done the following to you: (1) Scratched me; (2) Slapped me. Perpetration of physical violence on an intimate partner was measured using the 16 items, by rewording as follows: How many times have you done the following to a person that you have been on a date with: (1) Scratched them; (2) slapped them. The items for physical assault victimization and perpetration were from the Safe Dates questionnaire (Foshee & Langwick, Citation2010). All items used to measure physical assault are provided in Table . Items were summed for a total score. Higher scores indicate more victimization [first item] and more perpetration [second item].

Table 2. Responses to experience and perpetration of violence with dating partners

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS, version 24 (IBM Corp 2013). Descriptive statistics including frequencies, means, standard deviations, and range were computed. Using Chi-Square tests, the correlation among study variables was examined. Regressions were also conducted. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were determined using means and standard deviations. Pearson’s correlation and one-way ANOVA were used to determine regression (r) and F values, respectively. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Of the 450 questionnaires distributed, a total of 441 completed questionnaires were received giving a response rate of 98%. Participants’ mean age was 22.7 ± 4.3 years and 52.4% (n = 231) were female. The mean number of current sexual partners was 1.4 ± 1.47 (range: 0–13). Only 28.5% reported using a condom during every sexual intercourse in the last 3 months.

Experience of at least one form of cyberbullying was reported by 76.2% (n = 336) of respondents. Receiving mean or hurtful text messages was the most common form of cyberbullying experienced (n = 235; 53.2%). This was followed by monitoring via intrusive calling or texting (n = 180; 47.4%) and being bullied through text messages (n = 130; 29.5%). Other forms of cyberbullying included posting of unwanted pictures on websites (n = 22; 5.1%) and the circulation of embarrassing stories which were either true (n = 30; 6.7%) or false (n = 28; 6.4%). Table shows the responses to each cyberbullying item.

At least one form of physical assault from an intimate partner was endorsed by 50.6% (n = 223) of study respondents. The most common form of physical assault experienced by the participants was having had their arms twisted (n = 84; 19.1%), having their fingers bent (n = 84; 19.1%) and being pushed, grabbed or shoved (n = 80; 18.1%). Some participants were beaten up (n = 25; 5.7%) or assaulted with a weapon (n = 10; 2.2%) by a dating partner. Table shows the number of participants who experienced the different forms of physical assault from an intimate partner.

Many (n = 195, 42.2%) were also the perpetrators of at least one form of physical assault on a dating partner. Common forms of violence that were perpetrated included slapping the partner (n = 81; 18.4%), pushing, grabbing or shoving a partner (n = 70; 15.9%) and twisting a partner’s arm (n = 66; 15%). Frequencies for the perpetration of physical assault on an intimate partner are indicated in Table .

More males reported experiencing some form of cyberbullying from a dating partner than did females (p = 0.02). There was no gender difference in being assaulted by a dating partner (p = 0.36) nor in the perpetration of dating violence on a partner (p = 0.15).

There was a positive correlation between cyberbullying victimisation and dating violence victimisation (r = 0.32; p < 0.001). There was also a positive correlation between cyberbullying victimisation and dating violence perpetration (r = 0.26; p < 0.001). There was a strong positive correlation between being a victim of dating violence and perpetrating dating violence (r = 0.52; p < 0.001).

The variance in condom use over the last 3 months was 3.1% [F(5.104) = 3, 491, R2 = 0.031, p = 0.002]. There was a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.6) for the relationship between cyberbullying and condom use in the last 3 months. As cyberbullying increased, condom use in the last 3 months decreased. The effect size for the relationship between being a victim of dating violence and condom use in the last 3 months was large (Cohen’s d = 0.8). Specifically, as an individual experienced greater amounts of dating violence, condom use decreased. A similar large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.8) for the relationship between perpetrating dating violence and condom use in the last three months was observed. As perpetration of dating violence increased, condom use decreased.

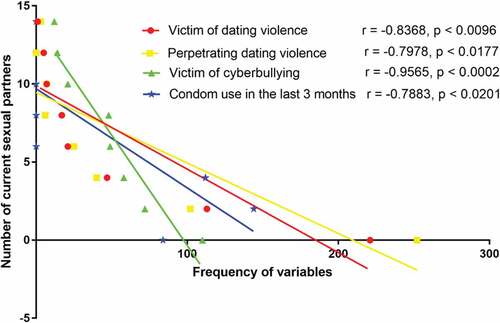

Figure indicates the relationship between the various variables of dating violence, cyberbullying and condom use and the number of current sexual partners. There was an inverse relationship between cyberbullying and the number of sexual partners (r = −0.9565; p < 0.0002), such that those who experienced more cyberbullying had fewer current sexual partners. The effect size for the above relationship was large (Cohen’s d = 0.8). A similar inverse relationship was noted between dating violence victimization and the number of current sexual partners (r = −0.79; p < 0.017), but the effect size was small (Cohen’s d = 0.2). Similarly, an inverse relationship was noted between perpetration of dating violence and the number of current sexual partners (r = −0.7978; p < 0.02). However, the effect size between dating violence perpetration and the number of sexual partners was trivial (Cohen’s d = 0.07). In addition, as the number of sexual partners increased, condom use in the last 3 months decreased (r = −0.7883; p < 0.02). The effect size for this relationship was small (Cohen’s d = 0.20).

4. Discussion

This study shows that only 28.5% of tertiary education students in Durban, South Africa, used a condom every time during sexual intercourse in the last 3 months. Cyberbullying as well as dating violence was widespread among university students and both were associated with irregular condom use in the last 3 months. Hence, cyberbullying and dating violence are risk factors for HIV transmission in this young population.

This study shows that 76.2% of the student population have been victims of cyberbullying, with a larger proportion of victims being male. Similarly, Wong et al. (Citation2018) reported that cyberbullying victims were usually male. Cyberbullying is reported across the globe. In a review of 159 studies, Brochado et al. (Citation2017) reported a cyberbullying prevalence of up to 61%. A study in Hong Kong reported that 68% of students experienced cyberbullying (Leung et al., Citation2018). The latter study also reported a relationship between cyberbullying and life satisfaction and that friendship quality was protective against cyberbullying.

Accordingly, enhanced quality of relationship would be important in sexual partnerships. The association of cyberbullying with decreased condom use is a novel finding of this study. Sexual behavior can be influenced by many factors at both an individual and interpersonal level. Social media interactions result in different social networks, which are more likely to be on a larger scale than personal social interactions. The results indicate that over half of the participants received hurtful text messages from their dating partners and almost a third were bullied on social media platforms. The fear of these personal messages being placed on social media by a dating partner can influence sexual behavior, particularly where the partner engages in bullying behavior. Hence, sexual behavior, such as condom-less sex, could be influenced by the dominant partner. Other research reports that youth, who bully partners, are less committed to their romantic relationships and have fewer positive opinions of their dating partner (Connolly et al., Citation2004). The same can be argued for cyberbullying. Indeed, the current findings indicate that unwanted pictures, hurtful and even false information about partners were posted on social media. Such emotional abuse allows the perpetrator to maintain power and control in the relationship. It also confirms a lack of concern for the partners’ feelings, particularly since online information can be viewed and frequently forwarded, providing widespread propagation of the information, without further active contribution of the perpetrator (Schultze‐Krumbholz et al., Citation2016). The victimized partner may consequently have a fear of negative information such as promiscuity, for example, being posted on social media. Accordingly, such anxiety results in the inability to negotiate condom use as the victim feels unable to make decisions within the relationship.

This study also reports a direct relationship between cyberbullying and dating violence. Other recent studies also found an association between online and physical violence, including intimate partner violence, among young people (Lam et al., Citation2019; Ranney et al., Citation2019). The current findings of half (50.6%) of the student population being victims of physical violence is higher than that of young people in other parts of South Africa. For instance, 40% of high school pupils in Cape Town experienced some form of dating violence (Swart et al., Citation2002). This could relate to greater amounts of violence with increasing age or the possibility of young people becoming more violent with the progression of time as the latter study was conducted in 2002. Furthermore, previous studies reported greater perpetration of dating violence by males (Boafo et al., Citation2014), which contrasts to our findings of similar levels of dating violence perpetration by both males and females. Girls previously reported that their physical aggression was in self-defense against their boyfriends’ use of violence (Hird, Citation2000). However, the latter study did not measure the order of violence, which makes self-defense difficult to assess. This explanation of self-defense has also been criticized because it assumes male aggression and does not include circumstances in which males are abused (Dutton & Nicholls, Citation2005).

There is reduced condom use among both victims and perpetrators of dating violence, indicating poorer sexual health outcomes in these relationships. Feminist theories propose that partner violence is usually committed in an effort to maintain power and control in the relationship (Walker, Citation1979). Because of the fear of potential physical violence from their partners, many women would find it difficult to insist on condom use. Other studies have shown that women may not ask their partners to use condoms for fear of appearing promiscuous, an apprehension of intimate partner violence, and threats of the partner leaving the relationship (Haffejee & Maksudi, Citation2020; Jewkes et al., Citation2003; Varga, Citation1997). Furthermore, young girls tend to use contraceptives more effectively when they have greater control over their sexual activities (Conner & Norman, Citation1996); however, young South Africans lack the confidence to use condoms (Haffejee et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, abuse by dating partners has previously been linked to the early initiation of sexual activity (Niolon et al., Citation2015). In the province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, over a third of young girls, aged 15–19 years, reported their sexual debut through force or coercion [United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, Citation2004)]. Furthermore, there is low condom usage at sexual debut among young people in the same geographic location (Haffejee et al., Citation2018). In contrast, sexual debut is delayed among those who are not involved in any form of dating violence (Boafo et al., Citation2014).

Studies also indicate a low prevalence of condom usage among women with multiple sexual partners (Haffejee et al., Citation2016; Kalichman et al., Citation2007; Ports et al., Citation2015). Participants of the current study indicated up to 13 concurrent sexual partners. This is supported by the large numbers of lifetime sexual partners reported in the South African Demographic and Health survey, which also reported that approximately two-thirds of men and women with multiple sexual partners used a condom during their last sexual intercourse (Statistics South Africa, Citation2016). However, results from the current study indicated an inverse relationship between the number of sexual partners and cyberbullying, and dating violence victimization and perpetration. This suggests that different factors may be involved in young people having multiple sexual partners. This requires further investigation.

The interrelationship between both cyberbullying and dating violence with irregular condom use indicates that a person may not feel confident in requesting condom use when he or she is with either a physically or emotionally abusive partner. Although the study did not examine whether the inconsistent use of condoms was only with abusive partners, it is likely that abuse from a previous partner would cause a lack of confidence with future partners. Hence, emotional and physical abuse is linked to increased risky sexual behavior among young people. When both of these exist within a dating relationship, the fear of the dominant partner would be enhanced.

The association of dating violence and cyberbullying with decreased condom use indicates that these behaviors serve as barriers to achieving the NSP target of reducing HIV as well as other sexually transmitted infections (STI) by 2022, since condom use is one of the key prevention measures in combatting the spread of HIV and STIs (Hopkins et al., Citation2018). Although health promotion interventions have been implemented to improve condom use, these interventions are often not effective as many young adults still lack the confidence to use condoms and negotiation skills are poor (Haffejee et al., Citation2018). Gender-based imbalances within relationships also play a role in poor negotiation skills and low condom use (Haffejee & Maharajh, Citation2019). Furthermore, HIV-associated stigma could also contribute to failure of health interventions (Haffejee & Maharajh, Citation2019) and this also needs to be addressed. Programs that combine sexual health with all these factors, including cyberbullying and dating violence prevention are warranted in this population. Such programs in other settings have been useful in reducing physical violence among young men (Niolon et al., Citation2015).

It is concluded that high levels of intimate partner physical violence and cyberbullying are present in the student population in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and that these are linked to inconsistent condom use.

5. Limitations

This study was conducted in a university setting and hence excluded youth who were unable to access tertiary education. The latter have greater disadvantages due to financial or other social constraints and hence more likely to be involved in violence. These results may therefore not be generalizable to all young people within the region. Further studies are required to address these factors in other populations in the region.

The cross-sectional nature of the study is also limiting as it precludes causal connections between cyberbullying, dating violence and risky sexual behavior. It is suggested that future studies implement intervention programs to reduce cyberbullying and/or dating violence, to evaluate their effects on risky sexual behavior.

6. Recommendations

Given the harmful consequences of cyberbullying and dating violence, it is recommended that antibullying programs be implemented in schools to prevent these behaviors and their negative consequences.

Availability of data and materials

The data analyzed in the current study are available, on reasonable request, from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

FH: Involved in the inception of the research, analysis of results and wrote the first draft of the paper.

PDS: Statistical analysis and interpretation of results.

RC: Involved in the conceptualization of the research, compiling of data collection tool, editing of the final draft of the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Prior to data collection, ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (IREC 084/16). All participants provided written informed consent, prior to answering the questionnaire.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the late Dr Euvette Taylor, Mr Senzo Mpangase and Dr Khanyie Khumalo for assistance with data collection. The authors are grateful to Dr J Basdav for administrative assistance.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Firoza Haffejee

Dr. Haffejee, is an associate professor in Physiology and Epidemiology at the Durban University of Technology in South Africa. She holds a PhD in Women’s Health and is currently conducting research on public health issues, particularly in the field of HIV prevention.

Dr. Corona is a professor of Psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University in the United States of America. She holds a PhD in Clinical Psychology. Her community-engaged research focuses on Latina/o and African-American adolescents’ health promotion and risk reduction with specific expertise in adolescent sexual health. Dr. Corona partnered with Dr. Haffejee for the research project on condom use among South African students and visited South Africa to work on this research.

Dr. Shallie holds a PhD. from Olabisi Onabanjo University in Nigeria and is currently a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences, at Durban University of Technology, South Africa.

References

- Bennett, D. C., Guran, E. L., Ramos, M. C., & Margolin, G. (2011). College students’ electronic victimization in friendships and dating relationships: Anticipated distress and associations with risky behaviors. Violence and Victims, 26(4), 410–11. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.26.4.410

- Boafo, I. M., Dagbanu, E. A., & Asante, K. O. (2014). Dating violence and self-efficacy for delayed sex among adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 18(2), 46–57.

- Brochado, S., Soares, S., & Fraga, S. (2017). A scoping review on studies of cyberbullying prevalence among adolescents. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(5), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016641668

- Conner, M., & Norman, P. (1996). The role of social cognition in health behaviours. In Conner, M. & Norman, P (Ed), Predicting health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models (pp. pp. 1–22). Open University Press.

- Connolly, J., Craig, W., Goldberg, A., & Pepler, D. (2004). Mixed‐gender groups, dating, and romantic relationships in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.01402003.x

- Corona, R., Hood, K. B., & Haffejee, F. (2019). The relationship between body image perceptions and condom use outcomes in a sample of South African emerging adults. Prevention Science, 20(1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0957-7

- DiClemente, R. J., & Wingood, G. M. (1995). A randomized controlled trial of an HIV sexual risk—reduction intervention for young African-American women. Jama, 274(16), 1271–1276. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530160023028

- Draucker, C. B., & Martsolf, D. S. (2010). The role of electronic communication technology in adolescent dating violence. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(3), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00235.x

- Dutton, D. G., & Nicholls, T. L. (2005). The gender paradigm in domestic violence research and theory: Part 1—The conflict of theory and data. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(6), 680–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.02.001

- Espada, J. P., Morales, A., Guillén-Riquelme, A., Ballester, R., & Orgilés, M. (2016). Predicting condom use in adolescents: A test of three socio-cognitive models using a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health, 16(35), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2702-0

- Foshee, V., & Langwick, S. (2010). Safe dates: An adolescent dating abuse prevention curriculum. United States of America.

- Garaigordobil, M., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2019). Victimization and perpetration of bullying/cyberbullying: Connections with emotional and behavioral problems and childhood stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a3

- Giorgio, M., Townsend, L., Zembe, Y., Cheyip, M., Guttmacher, S., Carter, R., & Mathews, C. (2017). HIV prevalence and risk factors among male foreign migrants in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS and Behavior, 21(3), 949–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1521-8

- Haffejee, F., Koorbanally, D., & Corona, R. (2018). Condom use among South African University Students in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal. Sexuality & Culture, 22, 1279-1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9523-5

- Haffejee, F., & Maharajh, R. (2019). Addressing female condom use among women in South Africa: A review of the literature. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1643813

- Haffejee, F., & Maksudi, K. (2020). Understanding the risk factors for HIV acquisition among refugee women in South Africa. AIDS Care, 32(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1687833

- Haffejee, F., Ports, K. A., & Mosavel, M. (2016). Knowledge and attitudes about HIV infection and prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in an urban, low income community in Durban, South Africa: Perspectives of residents and health care volunteers. Health SA Gesondheid, 21(1), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.02.001

- Halperin, D. T., Steiner, M. J., Cassell, M. M., Green, E. C., Hearst, N., Kirby, D., … Cates, W. (2004). The time has come for common ground on preventing sexual transmission of HIV. The Lancet, 364(9449), 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17487-4

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2013). Social influences on cyberbullying behaviors among middle and high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(5), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9902-4

- Hird, M. J. (2000). An empirical study of adolescent dating aggression in the UK. Journal of Adolescence, 23(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado

- Hood, K. B., & Shook, N. J. (2013). Conceptualizing women’s attitudes toward condom use with the tripartite model. Women & Health, 53(4), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2013.788610

- Jemmott, J. B., Jemmott, L. S., Spears, H., Hewitt, N., & Cruz-Collins, M. (1992). Self-efficacy, hedonistic expectancies, and condom-use intentions among inner-city black adolescent women: A social cognitive approach to AIDS risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 13(6), 512–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(92)90016-5

- Jewkes, R. K., Levin, J. B., & Penn-Kekana, L. A. (2003). Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: Findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine, 56(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00012-6

- Kalichman, S. C., Ntseane, D., Nthomang, K., Segwabe, M., Phorano, O., & Simbayi, L. C. (2007). Recent multiple sexual partners and HIV transmission risks among people living with HIV/AIDS in Botswana. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 83(5), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2006.023630

- Kalichman, S. C., Williams, E. A., Cherry, C., Belcher, L., & Nachimson, D. (1998). Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. Journal of Women’s Health, 7(3), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1998.7.371

- Lam, S., Ferlatte, O., & Salway, T. (2019). Cyberbullying and health: A preliminary investigation of the experiences of Canadian gay and bisexual adult men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 31(3), 332–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2019.1596860

- Leung, A. N. M., Wong, N., & Farver, J. M. (2018). Cyberbullying in Hong Kong Chinese students: Life satisfaction, and the moderating role of friendship qualities on cyberbullying victimization and perpetration. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.016

- Niolon, P. H., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Latzman, N. E., Valle, L. A., Kuoh, H., Burton, T., Taylor, B. G., & Tharp, A. T. (2015). Prevalence of teen dating violence and co-occurring risk factors among middle school youth in high-risk urban communities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(2), S5–S13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.019

- O’Leary, A., Goodhart, F., Jemmott, L. S., & Boccher-Lattimore, D. (1992). Predictors of safer sex on the college campus: A social cognitive theory analysis. Journal of American College Health, 40(6), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.1992.9936290

- Osuafor, G. N., & Mturi, A. J. (2014). Attitude towards sexual control among women in conjugal union in the era of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Mahikeng, South Africa. Etude de la Population Africaine, 28(1), 538. https://doi.org/10.11564/28-1-506

- Piccoli, V., Carnaghi, A., Grassi, M., Stragà, M., & Bianchi, M. (2020). Cyberbullying through the lens of social influence: Predicting cyberbullying perpetration from perceived peer-norm, cyberspace regulations and ingroup processes. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.09.001

- Ports, K. A., Haffejee, F., Mosavel, M., & Rameshbabu, A. (2015). Integrating cervical cancer prevention initiatives with HIV care in resource-constrained settings: A formative study in Durban, South Africa. Global Public Health, 10(10), 1238–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1008021

- Potts, M., Halperin, D. T., Kirby, D., Swidler, A., Marseille, E., Klausner, J., Hearst, N., Wamai, R. G., Kahn, J. G., & Walsh, J. (2008). Reassessing HIV Prevention. Science, 320(5877), 749–750. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1153843

- SANAC. (2017). South Africa’s national strategic plan for HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. South African National AIDS Council: https://sanac.org.za/download-the-full-version-of-the-national-strategic-plan-for-hiv-tb-and-stis-2017-2022/

- Sasson, H., & Mesch, G. (2017). The role of parental mediation and peer norms on the likelihood of cyberbullying. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 178(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2016.1195330

- Schultze‐Krumbholz, A., Schultze, M., Zagorscak, P., Wölfer, R., & Scheithauer, H. (2016). Feeling cybervictims’ pain—The effect of empathy training on cyberbullying. Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21613

- Seedat, M., Van Niekerk, A., Jewkes, R., Suffla, S., & Ratele, K. (2009). Violence and injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an agenda for prevention. The Lancet, 374(9694), 1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60948-X

- Shisana, O., Rehle, T., Simbayi, L. C., Zuma, K., Jooste, S., Zungu, N., … Onoya, D. (2014). South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. HSRC Press.

- Statistics South Africa. (2016). South Africa demographic and health survey 2016: Key indicator report Department of Health, South Africa. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report%2003-00-09/Report%2003-00-092016.pdf

- Sullivan, T. N., Erwin, E. H., Helms, S. W., Masho, S. W., & Farrell, A. D. (2010). Problematic situations associated with dating experiences and relationships among urban African American adolescents: A qualitative study. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0225-5

- Swart, L.-A., Seedat, M., Stevens, G., & Ricardo, I. (2002). Violence in adolescents’ romantic relationships: Findings from a survey amongst school-going youth in a South African community. Journal of Adolescence, 25(4), 385–395. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2002.0483

- UNAIDS. (2004). Facing the future together: Report of the secretary general’s task force on women, girls and HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa. United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc380-facingfuture_en.pdf

- Varga, C. A. (1997). Sexual decision-making and negotiation in the midst of AIDS: Youth in KwaZulu/Natal, South Africa. Health Transition Review, 7, 45–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40608688

- Vetten, L., & Bhana, K. (2001). Violence vengeance and gender. A preliminary investigation into the links between violence against women and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Centre for the study of violence and reconciliation. https://www.popline.org/node/187626

- Walker, L. E. (1979). The battered woman. Harper and Row.

- Wong, R. Y., Cheung, C. M., & Xiao, B. (2018). Does gender matter in cyberbullying perpetration? An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 79, 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.022

- Wubs, A. G., Aarø, L. E., Flisher, A. J., Bastien, S., Onya, H. E., Kaaya, S., & Mathews, C. (2009). Dating violence among school students in Tanzania and South Africa: Prevalence and socio-demographic variations. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 37(2_suppl), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494808091343

- Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2010 summary report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 19, 39–40. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11990/250

- Garcia-Moreno, C., & Watts, C. (2000). Violence against women: Its importance for HIV/AIDS. Aids, 14(3), 253–265. http://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=846718

- Hopkins, K. L., Doherty, T., & Gray, G. E. (2018). Will the current national strategic plan enable South Africa to end AIDS, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections by 2022? Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v19i1.796

- Ranney, M. L., Pittman, S. K., Riese, A., Koehler, C., Ybarra, M. L., Cunningham, R. M., … Rosen, R. K. (2019). What counts?: A qualitative study of adolescents’ lived experience with online victimization and cyberbullying. Academic Pediatrics, 20(4), 485-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.11.001