Abstract

Governments implement many anti-polarization-programs to prevent radicalization. Evaluations of these programs give insights in either (psychological) effects, program-mechanisms or contexts, but often do not show how they interact. This study provided such a model and increased awareness of the psychological complexity behind polarization prevention. We evaluated a dialogue-training that aimed to prevent polarization by giving adolescents with ethnic minority backgrounds a platform that enables them to discuss their societal opinions. Our evaluation showed what the psychological impact was by quantitatively (N = 32, pre- and post-test) and qualitatively assessing changes in their polarization belief system and critical thinking. Complementary, we showed why this was the psychological impact by analyzing interviews, manuals and theories of change within the Realist Evaluation Model that explains how Program-Mechanisms foster Outcome-patterns in certain Contexts. The qualitative evaluation-results showed that dialogue-trainings can stimulate critical societal participation. The possible complexity behind polarization prevention becomes salient in observed changes in the polarization belief system. Some adolescents expressed polarizing attitudes more negatively after participating. Though counter-intuitive, we discuss how these exploratory results could stand for improved awareness of own societal positions, expression skills and resilience towards isolation and polarization. Yet, after-care seems an often forgotten, but necessary contextual component.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Governments implement many anti-polarization-programs to prevent radicalization. This study evaluated a dialogue training that aimed to prevent polarization by giving adolescents with minority backgrounds a platform that enables them to discuss societal opinions. Our evaluation showed what the psychological impact was by quantitatively (N = 32, pre- and post-test) and qualitatively assessing changes in their polarization belief system and critical thinking. Complementary, we showed why this was the psychological impact by analyzing interviews, manuals and theories of change. We assessed how the program-mechanisms fostered the program-results in certain contexts. The qualitative evaluation-results showed that dialogue trainings can stimulate critical societal participation. Some adolescents did express some polarizing attitudes stronger after participating. Though counter-intuitive, we discuss how these preliminary and exploratory results could stand for improved awareness of own societal positions, expression skills and resilience towards polarization. Replication studies are necessary, but after-care seems a necessary contextual component to achieve this latter outcome.

1. Introduction

Politically motivated attacks, such as the attacks in a number of European cities (e.g., London, Paris and Brussels) as well as in other parts of the world, combined with the existence of European foreign fighters and right-wing radical groups emphasize the importance of research on policies to prevent political violence (Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN), Citation2019; Webber et al., Citation2018). A psychological radicalization process, in which individuals become more motivated to use violence to achieve political goals, is often perceived as the stage people go through before they commit these violent attacks, regardless of whether these attacks stem from religious, right-wing or left-wing ideologies (Doosje et al., Citation2013, Citation2016; McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2008; Moghaddam, Citation2005; Veldhuis & Bakker, Citation2007). Accordingly, it has been widely accepted that one sustainable solution to prevent people from radicalizing would be to prevent societies, in which they live, from polarizing (Malmros, Citation2019; Lub, Citation2013). Polarization refers to the “sharpening of divisions between groups that share certain social, cultural or religious traits” (Lub, Citation2013, p. 165), which in extreme form can be related to societal conflict (Dimaggio et al., Citation1996).

As a result, a long-term strategy of European governments is the large-scale (financial) support of programs that aim to prevent polarization (See for instance, Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN), Citation2019). These policies tend to focus on social psychological, societal, political and contextual risk and resilience factors in the general population or vulnerable groups to ensure that these groups stay closely connected to and part of their societies (Gielen, Citation2019; Malmros, Citation2019). Published evaluation-studies that empirically investigate the psychological impact of prevention-programs, unfortunately, remain scarce mainly due to theoretical, practical and methodological complexities (Feddes & Gallucci, Citation2015; Horgan & Braddock, Citation2010).

Considering the wide support these polarization prevention-programs enjoy, this study aims to show how important evaluations of such programs are. This is mainly due to the psychological complexity that lies behind polarization prevention. It seems especially crucial to be aware of the psychological (side-)effects these programs can provoke (Vermeulen, Citation2013). Only then, program developers can adapt the contexts and elements of the program in such a way to make these programs as beneficial as possible for their target group. To illustrate the added value of psychological evaluations, we evaluated one example of a polarization prevention strategy (Paluck, Citation2010; See also Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN), Citation2019)—a dialogue training on sensitive societal issues that enables minority groups to express themselves and enhance their expression skills, critical thinking and confidence.

To be able to evaluate such a complex polarization prevention program and to understand the psychological complexity behind it, we first need to analyze social-psychological (evaluation) research and assess what the psychological impact is. Second, we use lessons from process, manual, scientific theories of change and stakeholder evaluations that consist of techniques to grasp why this psychological impact can be found in the context of the program. Third, we show how previous evaluations solely give theoretical and empirical insights in either (psychological) outcomes, working program-mechanisms or beneficial contextual factors, but often do not provide a clear model that shows how these three factors interact. We believe, however, that all these factors interact with each other and that knowledge on these interactions support a better understanding of the effectiveness or possible harmful side-effects of the program (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). We therefore end our introduction with a description of the Realist Evaluation Method that enables us to grasp these interactions.

1.1. What is the psychological impact?

Before discussing the psychological research on polarization prevention, it is important to stress why psychological impact evaluations are a necessity, especially when it comes to locally implemented programs. National policies demand more general evaluations of its plans, processes and involved institutional actors such as municipalities (CitationMinistry of Justice and Security, National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism, and Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment; Noordegraaf et al., Citation2016). Outcomes such as the purposiveness, legitimacy and robustness of national policies give insights into their effectiveness (Noordegraaf et al., Citation2016). National policies, however, trickle down to local programs, which are executed by practitioners in local communities. These programs directly influence their beneficiaries. Because they most often tackle social-psychological factors that have been related to polarization in their beneficiaries, such as societal grievances (Malmros, Citation2019), it is crucial to assess the actual impact on these factors.

A dialogue training on sensitive societal issues is thus not a specific method for preventing radicalization. It is a suitable method to enable individuals to engage more in society, and to stage general polarization prevention. Nonetheless, prevention of polarization and the psychological factors that are tackled are often viewed within the broader framework of primary radicalization prevention (Lub, Citation2013). Although the outcome can be diverse and non-violent (Schmid, Citation2013), one definition of radicalization is that it is “a process through which people become increasingly motivated to use violent means against members of an out-group or symbolic targets to achieve behavioral change and political goals” (Doosje et al., Citation2016, p. 79). The psychology behind radicalization and radicalization as a concept, are however widely contested topics, let alone evaluating the primary prevention of radicalization. Research and policies thus face a complex conceptual challenge in this field. They insurmountably suffer from the theoretical dispute and the empirical haziness that exists around the radicalization and polarization process and the hypothesized psychological risk factors that make up such processes (Schmid, Citation2013). This problem is enhanced by the fact that sensitivity and secrecy around this topic, small research samples and an academic over-reliance on secondary sources, empirically limit conclusions (Czwarno, Citation2006; Lum et al., Citation2006; Nelen et al., Citation2010; Sageman, Citation2014). Additionally, some scientists even question the existence of a radicalization process and emphasize the unwanted stigma related to the securitization of the concept (De Goede et al., Citation2014; Schmid, Citation2013). We thus conclude that primary polarization prevention-programs may ideally not want to carry the name “radicalization prevention” as this concept is theoretically and societally contested and can trigger unwanted feelings of stigmatization in target groups.

Dialogue trainings that aim to prevent polarization do tackle a specific sub-set of both potential risk and protective factors, such as polarization indicators and critical thinking. Critical dialogues about societal issues and opinions can support adolescents’ formation of nuanced ideals and identities, which are crucial elements for adolescents to become critically engaged citizens in democratic societies (Van San, Sieckelinck, and de Winter, Citation2013). If adolescents are enabled to express their (non-mainstream) opinions, it could enhance their awareness and perspective taking (empathy), as well as intergroup and political tolerance. It could additionally diminish societal grievances, needs to use verbal or physical violence to express these opinions and isolation (Aly et al., Citation2014; Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter, Citation2013; see also Paluck, Citation2010). Moreover, enhanced critical thinking skills could make people more resilient towards one-sided extremist propaganda (Cherney et al., Citation2018; Neumann, Citation2013; Ten Dam & Volman, Citation2004). Critical thinking in this case does not refer to what, but rather how people think. Ennis defines critical thinking as “reasonable, reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do”(Ennis, Citation1991, p. 474). A critical thinker, for example, is able to review several sides of one problem, to question important issues, to look for solutions, and to investigate an issue if necessary (Ennis, Citation1991). If individuals are enabled to express themselves and feel heard, supported and more empathetic towards diverging and opposing opinions in dialogues, risks for polarization could be diminished. We thus expected that this dialogue training on societal opinions indeed fosters increased critical thinking skills and resilience against polarization (Ennis, Citation1991; See also Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN); Brandsma, Citation2016).

Many models have identified polarization indicators and have shown that certain psychological attitudes and experiences can make someone more susceptible for polarization and possibly radicalization (Baruch et al., Citation2018; McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2008; Moghaddam, Citation2005; Webber et al., Citation2018). Doosje et al. (Citation2013), for instance, developed a model that lends itself perfectly to assess individual experiences about inter-group divisions. This polarization belief system is comprised of polarizing attitudes towards own societal group positions and individual positions. Note that the large majority of individuals with these attitudes will never use violence towards outgroups (McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2014). Specifically, we used a part of the model that shows how polarizing social factors (perceived individual and collective deprivation, perceived realistic and symbolic group threat, perceived personal emotional uncertainty and perceived procedural injustice) are determinants of the psychological variables “perceived illegitimacy authorities”, “perceived in-group superiority”, and “societal disconnectedness”. Moreover, these psychological variables seem related to positive attitudes towards in-group violence, conducted by peers. This attitude was again related to individuals’ own violent intentions towards other groups (Doosje et al., Citation2013). Other polarization risk models are similar and range from radical attitudes (attitude towards the West) to grievances (experienced stigmatization) (McCauley & Moskalenko, Citation2008).

Previous impact evaluations have shown the value of using psychological models, such as the polarization belief system, to quantitatively assess psychological changes over the course of the program. One study used a quantitative questionnaire to assess elements of the polarization belief system to evaluate a radicalization prevention program (Feddes et al., Citation2015). The authors found that this resilience and positive identity training indeed led to more empathy, perspective taking and lower attitudes toward ideology-based violence and own violent intentions. These results showed what the psychological impact was, and additionally increased the awareness of possible unwanted harmful effects; participants of this program also showed stronger traits of narcissism (an identified radicalization risk factor) after the program. Nonetheless, for the sake of policy-improvement, it is important to also empirically assess in the same study why this program led to those changes.

1.2. Why is this the psychological impact?

From a methodological point of view, social psychological evaluation research needs to be complemented with methods that explain why psychological changes happened in the context of a program (black box) (Nelen et al., Citation2010). Isolated quantitative questionnaires are too sterile to build a comprehensive bridge between the academic world and the practical reality of policy programs. In order to detect with a questionnaire which working element of a program leads to that specific impact, one must manipulate a laboratory-like situation and filter out all other working elements of a program that can explain this result as well. To illustrate this, think of an adolescent who receives a group training that encourages dialogue and teaches how to show more empathy to different people and how to deal with discriminatory situations. In order to investigate with a quantitative questionnaire which element of the training caused a certain result (e.g., less polarized views), several control trainings that cover one or no element should be evaluated. Accordingly, the trainings with more positive results contain the successful working elements. However, in the real world, in which trainings are costly and contain many different elements, this is often an impossible methodological demand. In most cases, working elements cannot be filtered out, as they are rather fixed. Additionally, elements of polarization prevention-programs have different effects in different complex Contexts (e.g., heterogenic characteristics of mentors or target-groups) (Gielen, Citation2015; Pawson, Citation2006). Furthermore, the small samples that are willing to participate in these voluntary evaluation studies and practical constraints limit the options for control-groups. Thus, psychological non-controlled quantitative methods must be complemented with different methods to understand why certain program-elements and contextual factors foster certain results (Greene et al., Citation1989).

Moreover, research on target group characteristics and mentors in group dialogues illustrates the importance of doing research on complex contextual influences. Dialogues could, for instance, prevent (further) polarization between individuals who are not yet in conflict with each other (Brandsma, Citation2016). On the other hand, dialogues in the context of a heated and rising conflict might even do harm, as groups tend to benefit more from dialogues if they have similar goals, cooperate and have an equal status (Paluck, Citation2010). Moreover, research on mentors states that just “opening and guiding” a plenary dialogue is probably not sufficient to obtain wanted results such as critical thinking. Adolescents will be more likely to participate in a dialogue if there is a motivating, matching and positive relation between the mentors and the adolescents. It seems crucial that the mentors show true interest and are able to view more extreme expressions of participants as a critique on society and not as harmful signs of potential radicalization (Brandsma, Citation2016; Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter, Citation2013; Wentzel & Asher, Citation1995).

Qualitative effect, process and theory driven evaluations are suitable methods to open this black box and to understand underlying mechanisms and contextual components. The black box refers to information on working (and potentially harmful) program-mechanisms and contextual influences (Lub, Citation2013; Nelen et al., Citation2010; Williams & Kleinman, Citation2014). Previous evaluations in the framework of radicalization prevention assessed working program-elements and contextual influences with observations and interviews with beneficiaries and the respective communities, but also with professionals who were actively involved in implementing the program (Aly et al., Citation2014; Choudhury & Fenwick, Citation2011; Feddes et al., Citation2013; Lakhani, Citation2012; Lamb, Citation2012; Pickering et al., Citation2008; Vermeulen, Citation2013). Finally, qualitative and theoretical research gains more insight in the black box by investigating scientific theories of change, program descriptions, and the goals of policy-makers and stakeholders and finally by assessing the process of the program-implementation (Williams & Kleinman, Citation2014). Conversely, these black box evaluations in itself do not always quantitatively assess the psychological impact. In short, both social psychological impact and black box evaluation research should be merged and accordingly grasped in one holistic model. We use an evaluation method for this study that incorporates this model—The Realist Evaluation Method.

1.3. Realist Evaluation Method

The Realist Evaluation Method of Pawson and Tilley (Citation1997), which was applied to radicalization prevention policies by Amy-Jane Gielen (Citation2018), has received little attention to assess psychological processes in beneficiaries of polarization prevention programs (Christiaens et al., Citation2018; Schuurman & Bakker, Citation2016; Veldhuis, Citation2012). Nonetheless, it can be used as a merging model that guides how psychological effects should be reviewed and grasped holistically in working program-mechanisms and contextual factors (Bonell et al., Citation2012; Bouwman-van ‘T Veer et al., Citation2011; Omlo et al., Citation2013). Specifically, Realist Evaluations use so-called Context-Mechanism-Outcome (CMO) configurations to describe the ad-hoc hypotheses that guide the evaluation materials and to describe post-hoc hypotheses—“what works, for whom, in which context and how” (Gielen, Citation2015, p. 23). CMO-configurations are hypotheses about how Mechanisms (i.e. M; hypothesized working program-elements that lead to a certain change, based upon theories from program practitioners and stakeholders, and scientific theories) in certain Contexts (i.e. C; conditions in which programs operate, such as geographic values and types of beneficiaries), lead to Outcome-patterns (i.e. O; (un)intended program-results) (Gielen, Citation2015). Note that Mechanisms are the engines that explain Outcome-patterns, but that these Outcome-patterns are contingent, caused by complex interactions between Mechanisms and Contexts.

The fact that knowledge about Contexts supports the understanding of psychological Outcome-patterns is illustrated in this example: in a group-based setting (C-Context), a vulnerable adolescent (C-Context), who voluntarily signed up for a prevention-program (C-Context), receives a training that focuses on individual talents and self-certainty (M-Mechanism). Due to the awareness of his positive talents (e.g., organization skills), his positive self-identity could be strengthened (O-Outcome-pattern), which could make him more resilient against radicalization (Hogg & Adelman, Citation2013). This training could have less impact on his positive identity formation when the adolescent was obligated to participate (Context).

1.4. Rationale and research questions

In conclusion, for this study we evaluated one dialogue polarization prevention program with elements of the Realist Evaluation Method. For our evaluation, we used quantitative methods (N = 32, pre- and post-test) to assess the psychological polarization belief system and critical thinking skills in the target group and we used theories of change, manual analyses and qualitative interviews to explain these changes in light of the working mechanisms and contextual factors. To our knowledge, this study is the first to combine the Realist Evaluation Method with psychological impact assessments of the polarization belief system and critical thinking skills to evaluate a polarization prevention program. Specifically, this evaluation study aimed to answer the following research questions: What is the social psychological impact of dialogue trainings that enable adolescents to discuss and express their self-chosen sensitive (extreme) societal ideas on the polarization belief system, critical thinking skills, expression skills and self-confidence? How can we explain the psychological impact considering the program-mechanisms and contextual factors?

The method and results sections will describe how we practically applied the Realist Evaluation Method in a social-psychological paradigm. In the method section, we discuss how we empirically evaluated the dialogue training with its CMO-configurations, psychometric materials and procedure. In the results section, we present the findings of our empirical evaluation. In the conclusion, we merge and analyze the results with the scientific literature. The paper ends with a general discussion on the limitations of our approach, which will be used to provide suggestions for future evaluations.

2. Method

In the method section, we explain how we identified the main CMO-configurations (hypotheses) of the dialogue training with a specific focus on polarization prevention and how we assessed the CMO’s with quantitative and qualitative materials. We end with the methodological and ethical procedure of this study.

2.1. CMO-hypotheses dialogue training

The current study evaluated a three-day workshop dialogue training which was implemented at three schools in The Netherlands. The Context-Mechanism-Outcome-configurations (hypotheses) of the program were identified with an analysis of the program manual. The main goal of this program is to prevent polarization and consequently possible future tensions between groups.

The following CMO-configurations were identified as hypotheses: the target group consists of adolescents between 14 and 18 years old, who are supposedly not in a polarized conflict, within school classes that are characterized by diversity and localized in neighborhoods with a high percentage of youth from ethnic minority backgrounds (C1). During three workshops, these adolescents will develop their own professional TV talk show, in which they are encouraged to express their personal opinions and ideals about self-chosen topics. Every adolescent is appointed to a different role in the talk show, ranging from the audience to the presenter (M1). Accordingly, the adolescents learn how to be resilient against biased and one-sided polarizing media (media literacy) by theoretical lessons and by generating their own talk show (M2). During the program, mentors encourage plenary dialogues in which sensitive topics, such as discrimination, are discussed and in which there is room for personal expressions (M3). These mentors also teach the adolescents how they can express, formulate and justify opinions and arguments (M4). The latter Mechanisms are expected to solely work if all actors involved in the program do not treat the target group as a securitized group, but rather as critical and engaged democratic citizens (C2). In addition, in order to feel understood, heard and motivated to participate in the dialogues and possibly society, adolescents should respect and appraise their mentors (C3).

Due to the latter Mechanisms and Contexts, we expected that adolescents gained experience in expressing their ideas and feelings about society (in which their feeling of being important, heard and taken seriously are supported) (O1), which improved their critical thinking skills (O2) and media literacy (O3). Combining all factors, we expected that adolescents became less vulnerable for polarization (i.e., experienced less polarizing feelings within the eleven constructs of the polarization belief system after their participation) (O4).

2.2. Materials to assess CMO-configurations

Quantitative questionnaires were used to assess changes in critical thinking and the polarization belief system (Outcome-patterns) and the appreciation of the mentors (Context) (N = 32, pre- and post-test). Mechanisms cannot be quantitatively assessed since the “elements” that were used by the program are fixed, rather than contingent. With qualitative semi-structured interviews (N = 11) we investigated the complex interactions between the CMO-configurations.

2.3. Quantitative materialsFootnote1

2.3.1. Contexts

The Teachers’ Teaching Behavior questionnaire (Maulana et al., Citation2014) was given after the end of the program to assess how adolescents evaluated the relation with their mentors of the dialogue training (C3). This questionnaire contains 24 cover statements about the mentors. The items could be answered on a scale of 1 (never), 2 (rarely), 3 (sometimes) to 4 (often). Previous research showed a good reliability (α = 0.85) (Maulana et al., Citation2014). The maximum score corresponds with a positive mentor-evaluation. An example item is: “My mentor of the dialogue training treated me with respect”.

2.3.2. Outcome-patterns

The questionnaires that assessed the Outcome-patterns were given both prior to and after the dialogue training. All items were statements and we adapted original questionnaires to the level of the target group. All items could be answered on a Likert scale of 1 (completely disagree), 3 (neutral) to 5 (completely agree).

The subjective level of critical thinking is measured with the “critical open-mindedness” scale (O2) (Sklad & Park, Citation2016). This scale uses nine items to assess the extent to which people think critically, rather than what they think (i.e., to what extent they are critical towards all sources of information, see the complexity behind different visions, are able to take perspective, understand that there is not one truth and solution and understand personal biases). Previous research (N > 200) shows sufficient reliability (α = 0.77), as well as the current study (α = 0.66). An example-item is: “Some people can have completely different opinions than me and still be right”. Higher scores indicate higher levels of critical thinking, critical open-mindedness and perspective taking.

We assessed the resilience against polarization with the psychological variables of the polarization belief system (i.e., indicators for polarization vulnerabilities) (O4). All items (three to four per scale) that assessed these variables were combined in one questionnaire (Doosje et al., Citation2013; Feddes et al., Citation2013; Mann et al., Citation2015). The questionnaire consisted of negative and positive statements and the scores on the positive statements were reversed for the final analyses. Higher scores indicate higher levels of polarized experiences or expressions. This questionnaire assesses the eleven experienced concepts A) Emotional uncertainty: example-item “I worry when a situation is unsure”; B) Individual relative deprivation: example-item “I feel discriminated against”; C) Collective relative deprivation: example-item “I think that my group is being discriminated against”; D) Perceived procedural in justice: example-item “I think that I am normally being treated with justice”; E) Symbolic group threat: example-item “I think that other groups in The Netherlands think that their group is better than mine”; F) Realistic group threat: example-item “I think that many companies within The Netherlands hire someone from a different group faster than someone from my group, even though someone from my group is more suitable”; G) Societal distance: example-item “I feel at home in The Netherlands”; H) Illegitimacy Dutch authorities: example-item “I respect the Dutch government”; I) In-group superiority: example-item “I think that everyone should be the same as the people from my group”. Finally, this questionnaire also contained two scales (J & K) which assess the positive attitudes towards the usage of violence by oneself (example-item: “I would be capable of destroying things to achieve something that I find very important”) and the positive attitudes towards the usage of violence done by others to achieve goals or ideals (example-item: “I understand that if someone else of my group strives for a certain ideal, violence can be necessary”). The reliability of the latter items ranges from sufficient to good (α = 0.71—α = 0.86).

2.4. Qualitative materials

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were held with eleven students and two teachers to understand the links between the Contexts, Mechanisms and Outcome-patterns. We used thematic analysis as a method to understand the results and we analyzed the following themes: Outcome-patterns: expressions of ideas and emotions about society (during which their feeling of being important, heard and taken seriously are supported) (O1); critical thinking (O2); media literacy (O3); experienced societal group positions (O4); Mechanisms: given agency in the development of talk shows (M1); receiving information on the media (M2); receiving practical information on and participating in dialogues (M3 and M4); Contexts: target group (C1); approach of mentors (C2); and finally, the evaluation of the mentors (C3). In the interviews, the interviewer asked specifically whether the latter Contexts and Outcome-patterns were influenced and how and if they were influenced due to participation in the program. If that was the case, the interviewees were asked which element of the project was influential and why. Finally, we analyzed scientific theories of change in the academic literature, which were used to understand the empirical results.

2.5. Procedure

Before the dialogue training and study started, all participating adolescents, their parents (if adolescents were younger than 18) and their teachers were notified about this study via an information sheet. After signing an informed consent form, the participating adolescents filled out the quantitative questionnaires in their classroom, once before and once after the program. The interviews were held after the program in private rooms.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

The dialogue training was implemented at three schools in The Netherlands. Approximately 130 adolescents participated in the dialogue training. All adolescents were approached to participate in the quantitative part of the evaluation study. For the final study, 32 adolescents participated in the quantitative part (Pre- and Post-testFootnote2). The adolescents were between 14 and 18 years. The sample consisted of female (N = 20) and male (N = 12) adolescents with mostly ethnic minority backgrounds. Relevant for this sample is that our quantitative data showed that the adolescents scored on average negative (lower than neutral) on items that measured positive attitudes towards violence. In addition, we interviewed eleven adolescents who were randomly selected from the sample that agreed to participate in the quantitative study. We also interviewed two teachers about the process and learning experiences of the adolescents during the course of the program. These teachers acted independently from the program, but monitored the program closely.

3.2. Quantitative data—outcome-patterns and context

3.2.1. Outcome-patterns

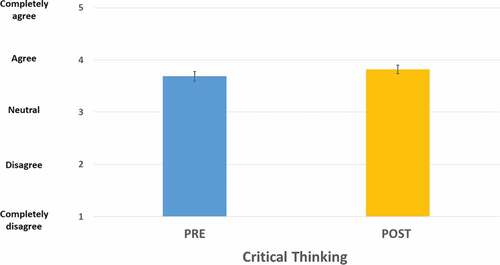

(O2) A quantitative pre- and post-data-analysis, using a Paired t-test (Figure ), showed that adolescents tended to score higher on the critical thinking scale after their participation in the program, compared to their score prior to the program (t(30) −1.480, p = 0.08 (one-tailed), d = 0.27, 95% CI [−0.32, 0.05]).

Figure 1. Critical Thinking; Difference over time in the mean score on the critical thinking scale before and after the participation in the program. Higher scores indicate a higher presence of critical open-mindedness and perspective taking. Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean

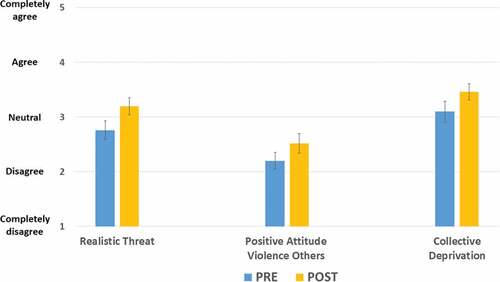

(O4) Paired t-tests showed that there were changes in some polarization belief system determinants that did not meet our a-priori expectations. Holm-Bonferroni corrections were made for eleven a-priori comparisons within the eleven polarization belief system scales. We did not take the 12th comparison within the critical thinking scale into account for this correction, as it is a separate analysis and in line with the direction of our expectation. As can be seen in Figure , and in contrast to our expectations, Paired t-tests showed that adolescents scored after their participation in the program on average significantly higher on the scales positive attitudes towards the usage of violence done by others (t(29) −3.564, p = 0.001, d = 0.65, 95% CI [−0.50, −0.13]) and realistic group threat (t(29) −3.002, p = 0.005, d = 0.55, 95% CI [−0.74, −0.14]) with a critical Alpha level of 0.005. We furthermore saw a similar trend in collective deprivation (t(30) −2.321, p = 0.027, d = 0.42, 95% CI [−0.68, −0.04]), that is deemed insignificant after the Holm-Bonferroni correction with a critical Alpha level of 0.0045. Higher scores on these scales indicate higher levels of negative attitudes toward societal in-group positions. Note that these preliminary exploratory results should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than hypotheses-testing due to their unexpected nature.

Figure 2. Polarization belief system; Differences in mean scores over time (before and after participation) on the scales realistic group threat, positive attitudes towards violence done by others to achieve certain goals or ideals and collective deprivation. A higher score indicates a higher presence of these expressions or experiences. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

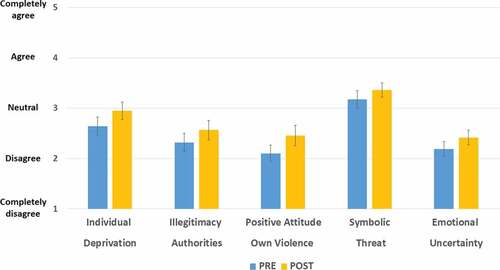

We found non-significant results in the same direction (Figure ) for the scales individual deprivation (t(30) −1.889, p = 0.069 d = 0.34, 95% CI [−0.64, 0.02]), illegitimacy authorities (t(29) −1.613, p = 0.118, d = −0.29, 95% CI [−0.55, 0.07]), positive attitudes towards the usage of own violence (t(28) −1.935, p = 0.063, d = 0.36, 95% CI [−0.73, 0.02]), symbolic threat (t(29) −1.506, p = 0.143, d = 0.28, 95% CI [−0.45, 0.07]) and finally, emotional uncertainty (t(29) −1.690, p = 0.102, d = 0.31, 95% CI [−0.50, 0.05]). These scales assess attitudes towards individual societal positions. We did not observe quantitative changes in the scales societal distance, procedural injustice, and in-group superiority during the course of the program.

Figure 3. Polarization belief system; Differences in mean scores over time (before and after participation) on the scales individual deprivation, illegitimacy authorities, positive attitudes towards the usage of own violence to achieve certain goals or ideals, symbolic threat and finally, emotional uncertainty. A higher score indicates a higher presence of these expressions or experiences. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean

3.2.2. Contexts

(C3) The questionnaire that assessed how the participants evaluated the mentors of the program showed that the mean score was 3.66, which indicates that the mentors were on average well respected.

3.3. Qualitative data—outcome-patterns, mechanisms and contexts

The interactions between the CMO-configurations were investigated with the interviews, according to quantity and quality.Footnote3 Based on these results, we further explained, underpinned, reformulated or added elements to the pre-existing CMO-configurations.

3.3.1. Outcome-patterns

(O1) Based on our qualitative data, it seems as if the majority of our interviewed adolescents indeed gained experience and comfort in expressing their ideas and emotions about society. They felt important, heard and being taken seriously. For example, student 11 indicated:

During the project we had to discuss certain topics with each other, and then you had to argue why you had a certain opinion, and that helped me to share my opinion with others … it is easier to express my opinion now.

(O2) In the interviews around half of the adolescents also showed signs of enhanced critical thinking skills, which was supported in our interviews with the teachers. Themes, such as increased awareness of the existence of diverse opinions among individuals and the acceptance of different opinions, were prominent in most interviews with the students. Student 8, for example, stressed the importance of critically consulting different types of media to come closer to the truth:

When I watched the news, I just was a sheep and I always went along with it. And now, when I see something big, I will check other websites to broaden my knowledge and to look whether it is all true or not, so that was my takeaway lesson.

(O3) Several students mention that they better understand the (complexity of the) media and how news is developed. A quote of student 9 also confirms that some adolescents became more literate in the media, which is confirmed in our post-hoc analysis:

I knew that the news did not make much sense, but now I know how they come to certain conclusions and why they say or don’t say certain things … Local things are discussed sooner, hence it is also interesting to investigate international media and to discuss it.

(O4) In contrast to our expectation, some adolescents expressed or experienced their societal group-positions as more negative. Our qualitative data explained and underpinned these results as adolescents showed signs of increased awareness of society and expressions skills. For example, the increase in experienced collective deprivation and realistic group threat, was explained by student 1 with a migrant background who spoke to the interviewer with a non-migrant background:

Yes, I think now, that the project stimulated that I should better … With you for example, it is easy if you are going to talk with a Dutch racist, because you are Dutch yourself, I think. But I must prove myself ten times harder than you must do, I am thinking about that now. I am just focused now on things; I take them seriously. Look, before that, I did not take it seriously.

3.3.2. Mechanisms

(M1) One of the main aspects of the dialogue training revolved around the talk show that was developed by the adolescents themselves, including the formation of topics. Data showed that this procedure enhanced engagement in expressing oneself, the feeling of being important, heard and taken seriously, critical thinking and media literacy. Especially, learning about different platforms to express opinions, researching self-chosen topics, and the active discussions, and passive participation in discussions in which they learned from peers, were perceived as helpful. Two different teachers discussed the added value of the talk show:

That process, of developing a product, for which they can discover themselves, like, I can do this, ohh from that point of view, there is so much more going on besides my own scope … I think that this was an important element.

I am careful that such a program does not force the adolescents in one way, it was not like that … the adolescents could choose their own topics, I liked that … The nice thing about it is that it was a nice alternative didactic method … when I saw the adolescents working, how enthusiastic, that pleases me … that is the reason to go to school, to reach people, that they are busy working, they are learning, it is all about that.

(M2) Second, media literacy seems to be stimulated by the actual information adolescents received about the media. Student 9 illustrates this:

I think that, because we received more information, because the mentors come from that world, they have a sober way of thinking about it, they tell us about how the news is developed. When they explained that, I thought, oh, I did not know … At first, I did not understand why they never showed news items from Syria, or Africa, and afterwards, I thought, yes I understand it, because it is not relevant here, we cannot do anything about it right away, and the things that happen in The Netherlands, we find them interesting because we can do something about it together.

(M3) The relevance of dialogues additionally became clear in the interviews—the adolescents interviewed others for their talk show, asked for people’s opinions, collected information, and finally, they analyzed different types of information. Critical thinking, for instance, due to increased empathy could be stimulated by the dialogues, which is illustrated by student 2:

But in the project, I feel empathetic towards other people, and that is how I changed … I listen more to people … because we sat next to each other and we had to listen to each other.

(M4) Several adolescents stressed the importance of the practical information which was provided by the mentors about dialogues, such as how one could express, formulate and justify opinions. This support could logically enhance the openness of adolescents about their societal visions. Student 5 illustrates this well:

Many examples, how you for example, you can express your own opinion, and be happy with what you are … There are no right or wrong answers when you are talking about yourself.

3.3.3. Contexts

(C1) The target group seemed suitable for this program. The quantitative results show that the target group holds on average a negative attitude (lower than neutral) towards the usage of violence by themselves or others. Hence, the target group should not be viewed as radicalized. This is also relevant for the next Contextual factor that the mentors did not securitize the target group, but rather approached them as engaged and critical democratic citizens (C2). This latter Context is illustrated by student 2:

Yes, I quite liked the project, because you could express your opinion, no matter how tough it is, everyone accepted it, and that was quite nice.

(C3) Both qualitative and quantitative data-analyses showed that on average adolescents respected the mentors well and were positively motivated by them. For instance, several students stated that mentors involved them during dialogues and made them feel heard and that they are being taken seriously. A quote of student 6 shows this well:

‘She said something, which did not relate to my opinion, and normally, I would react really mean. During the project, I could really control myself and enter the dialogue with her in a normal manner, due to the mentors … from the beginning, they told us to show respect to one another and that you should let other people finish and that you should listen, and so I did … and then a discussion is always better.”

4. Conclusion and discussion

Governments (financially) support the implementation of many local programs that aim to prevent polarization by enabling minority groups, who might have less access to the societal debate, to express themselves and enhance their expression skills, critical thinking and confidence. Published evaluations of these local prevention programs are however scarce and mainly give theoretical or empirical insights into either (psychological) outcomes, working program-mechanisms or contextual factors, but often do not provide a clear model that shows how these three factors interact. This study provided such a model and the results of our evaluation warrant more research in this field by increasing awareness of the psychological complexity behind polarization prevention and potential psychological effects due to certain program-mechanisms and contextual conditions.

For our study, we evaluated a dialogue-training that aimed to prevent polarization by giving adolescents with ethnic minority backgrounds a platform that enables them to discuss their (non-mainstream) societal opinions. In the long term, this could make them more resilient towards inter-group divisions, such as polarization. Our evaluation showed what the psychological impact was by quantitatively and qualitatively assessing changes in critical thinking skills and the polarization belief system before and after the program. The polarization belief system is comprised of polarizing attitudes towards one’s own group and individual positions within society. Complementary, we showed why this was the psychological impact by conducting interviews with the beneficiaries, qualitative process evaluations, manual analyses and scientific theories of change analyses within the Realist Evaluation Model. This model explains how and which Outcome-patterns are achieved in which Contexts and due to which program-Mechanisms. Table shows the updated hypothesized CMO-configurations that this evaluation study generated. These CMO-configurations will be explained more in detail below and can be used as a framework for future research and anti-polarization-program evaluations. Replications of this study are necessary to test these hypotheses.

Table 1. Hypothesized context-mechanism-outcome configurations for a dialogue training

The preliminary qualitative results and the literature support that active and playful didactic methods within dialogue trainings, such as the development of a talk show and guided dialogues on self-chosen topics, combined with theoretical lectures on dialogues and a broad range of societal news articles, could indeed marginally stimulate critical thinking, media literacy and active and critical participation in society. In the context of preventing ideals from getting adrift, Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter (Citation2013) also stress the importance of this possibility for and the capability of young adolescents to express and discuss their ideals. As such, adolescents feel heard and taken seriously. Note that the quantitative changes we found in critical thinking were not significant. The results do indicate that programs in which young adolescents are encouraged to express their opinions could foster more engagement in democratic societies.

Moreover, the results about contextual factors showed that this program is suitable for adolescents who do not justify extremist violence. The trainers should not approach adolescents with non-mainstream societal opinions as a possible threat to security, but rather treat them as critical and engaged democratic citizens. By extension, these types of programs may ideally not carry the name “radicalization prevention” as this concept is theoretically and societally contested and can trigger unwanted feelings of stigmatization in target groups.

4.1. The psychological complexity behind polarization prevention

The complexity that could lie behind the psychological impact of primary polarization prevention becomes especially salient in our analysis of the pre- and post-training changes in the polarization belief system. We expected that this program would be associated with a mitigation of polarizing experiences in the polarization belief system. Unexpectedly, however, some adolescents experienced or expressed marginally higher levels of negative polarizing attitudes after their participation, such as experienced realistic threat towards the in-group. Due to their unexpected nature and the small research-sample, these preliminary results should be interpreted as exploratory hypotheses-generating results. They could nonetheless indicate that some adolescents can become more vulnerable in the short term in terms of their societal awareness or experiences about their own group positions. Future studies should investigate this unexpected effect more rigorously with expanded samples. Yet, with our post-hoc theoretical analysis we can speculate why this result is at first logical, but could secondly even be beneficial for the adolescents and society if the right context is provided by the anti-polarization program.

This reinforcement seems at first logical. The discussions during the training often concerned positions of certain (minority groups) within society and some of these adolescents might have never received an opportunity to discuss and express their own societal frustrations or ideas with external mentors and their peers. If adolescents were less aware of or less able to feel or express their polarizing experiences before their participation, enabling them to express themselves seems effective and even beneficial. Some did express these group-related sensitivities more openly after critical thinking and dialogues about society. Societal dialogues in general can trigger an increase in awareness of own identities, ideals and social inequality (Aiello et al., Citation2018; Dessel & Rogge, 2008). And after all, positions of minority groups, which were the target groups of this program, tend to be indeed worse than those of the majority group in terms of the labor market, schooling and housing (Coenders et al., Citation2008). In line with this notion, their in-group-feelings of superiority did not seem to increase. These results match with a study that found that discussions, in which participants had to take the perspectives of the out-group, made the participants more aware of their own polarizing experiences (Paluck, Citation2010).

This short-term outcome of more awareness or negative expressions in terms of societal group-positions could be in line with the goal of preventing polarization in the long-term. Constructive societal engagement can be, for instance, stimulated by this effect, which keeps adolescents closer to democratic societies (Aldana et al., Citation2012). The expressions of individuals’ own beliefs can also support clarifications of such beliefs which in itself supports identity formation (Dessel & Rogge, Citation2008; Gaertner et al., Citation1996). Moreover, Paluck speculated that “the shape of positive change might feature a decline in positive attitudes before an upturn” (Paluck, Citation2010, p. 1182). In line with this, Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter (Citation2013) argue that non-mainstream opinions in an early stage of adolescence should thus not be seen in advance as dangerous, but rather part of a normal development of ideals. It seems preferable that adolescents feel comfort in externally expressing frustrations, extreme opinions and ideals, rather than keeping them internal, being isolated and expressing them solely online (Baruch et al., Citation2018; Van San, Sieckelinck and de Winter, Citation2013). Internal frustrations additionally could prevent vulnerable individuals from acting upon these emotions constructively. Thus, greater expressions of tension fields should be even a necessary condition of a dialogue to deal with polarization (Brandsma, Citation2016).

In terms of constructive impact, it can be however problematic if the professionals involved in implementing similar programs are not aware of this possible side-effect. Awareness is crucial, as the contextual component after-care is needed for those adolescents who possibly experience a reinforcement in, or are more aware of, their vulnerability (Aldana et al., Citation2012). Some adolescents do not understand the goal behind these discussions and might not know how they can constructively act upon increased vulnerabilities in a positive manner. If they do learn tools how to act constructively, they could possibly even change the status quo. However, without the right guidance and goal-setting on the long term, polarization could possibly be fueled in these adolescents (Klar & Branscombe, Citation2016; Paluck, Citation2010). Trainers and teachers thus should be skilled, unprejudiced and truly interested in the adolescents, but should also be able to set necessary pedagogical boundaries after the program has finished (Van San, Sieckelinck, and de Winter, Citation2013). Furthermore, trainers should prevent unwanted groupthink that could fuel irrational group polarization in one direction by providing critical alternative visions and ideas (Tsintsadze-Maass & Maass, Citation2014; see also Brauer & Judd, Citation1996). To conclude, dialogue trainings for adolescents can only be applied in schools where competent teachers or professionals are well able to provide good after-care and guide adolescents after implementation of the program when needed. These professionals need personal guidance themselves as well, as it can be a complex and demanding job.

4.2. Limitations

Although our results reveal some complexity behind the aim of tackling polarization in prevention programs, we must interpret our conclusions with caution. Most importantly, we cannot draw causal conclusions due to the lack of a control group. Nonetheless, within the practical limitations our evaluation faced, our results give valid preliminary insights and show that more research is necessary. For instance, our pre- and post-training assessments support that the participants developed during the course of the program. Additionally, it seems unlikely that a societal event rather than the dialogues could explain the changes in the polarization belief system within the sample. Participants came from three different schools and participated in different time periods. In line with this, there is no statistical relationship between the outcome and school type. Our qualitative findings also demonstrated induced sensitivity for societal group-positions that the participants linked to the actual dialogues. Finally, our conclusions seem credible as the adolescents did not score significantly higher on most subscales (e.g., in-group superiority and individual societal positions), but they did score higher on a scale that assessed experiences of relatively deprived societal group-positions.

Another limitation is that we used self-report questionnaires, which makes the results less objective and sensitive for retest-bias. Subjective results seem however relevant, because we aimed to understand the psychological impact on the beneficiaries themselves. Finally, we acknowledge the limitation that only a small percentage of all adolescents who participated in the project also participated in the evaluation study. Our sample was representative for the larger population due to the diversity in the sample, but a limited sample size decreases statistical power. This is an often experienced problem in evaluations. Even though the mixed-methods setup in combination with the Realist Evaluation Method is not bounded by the limitation of a minimum sample size to obtain insights, future evaluations should obtain data of as many beneficiaries as possible.

4.3. Conclusion

In conclusion, we believe that our Realist Evaluation combined with psychological impact assessments of the polarization belief system and protective critical thinking skills could be a useful platform for future evaluation initiatives in the field of polarization prevention. More applications and an increased awareness of this method could contribute to the development of a new evaluation standard in this field. This standard could accordingly support the improvement and development of polarization prevention program implementations throughout Europe and beyond.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Norah Schulten

Norah is an external PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam under the supervision of Dr. B. Doosje and Dr. F. Vermeulen (departments of Political Science and Psychology). For her PhD, she conducts research into prevention of polarization and radicalization and the (psychological) effects of policy programs that aim to prevent this. Especially she looks into productive, but also potential contra-productive side-effects of these policies. This interdisciplinary research has both a psychological and a political science approach. For her evaluation research she uses both quantitative methods and qualitative methods to measure the policy’s impact and to understand this impact in the framework of effective mechanisms, boundary conditions and contextual factors (Realist Evaluation Model). The current paper is an example of such an evaluation. The second part of Norah’s PhD consists of research into the relationship between mental health disorders and terrorism.

Notes

1. Items are translated from Dutch to English for this article.

2. We did not take missing data into account, since a Logistic Regression analysis showed no link between two “violence” scales and the adolescents that missed one assessment. Furthermore, the sample was representative for a larger population due to the diversity in the sample.

3. Quotes are translated from Dutch to English.

References

- Aiello, E., Puigvert, L., & Schubert, T. (2018). Preventing violent radicalization of youth through dialogic evidence-based policies. International Sociology, 33(4), 435–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580918775882

- Aldana, S. J., Rowley, B. C., & Richards-Schuster, K. (2012). Raising ethnic-racial consciousness: The relationship between intergroup dialogues and adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity and racism awareness. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(1), 120–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.641863

- Aly, A., Taylor, E., & Karnovsky, S. (2014). Moral disengagement and building resilience to violent extremism: An education intervention. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 37(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.879379

- Baruch, B., Ling, T., Warnes, R., & Hofman, J. (2018). Evaluation in an emerging field: Developing a measurement framework for the field of counter-violent-extremism. Evaluation, 24(4), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389018803218

- Bonell, C., Fletcher, A., Morton, M., Lorenc, T., & Moore, L. (2012). Realist randomised controlled trials: A new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 75(12), 2299–2306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.032

- Bouwman-van ‘T Veer, M., Knijn, T., & van Berkel, R. (2011). Activeren door Participeren. De Meerwaarde van de Wet Maatschappelijke Ondersteuning voor Re-integratie van Mensen in de Bijstand. MOVISIE.

- Brandsma, B. (2016). Polarisatie: Inzicht in de dynamiek van wij-zij denken. BB in Media.

- Brauer, M., & Judd, C. M. (1996). Group polarization and repeated attitude expressions: A new take on an old topic. European Review of Social Psychology, 7(1), 173–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779643000010

- Cherney, A., Bell, J., Leslie, E., Cherney, L., & Mazerolle, L. (2018). Countering violent extremism evaluation indicator document. Australian and New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee, National Countering Violent Extremism Evaluation Framework and Guide.

- Choudhury, T., & Fenwick, H. (2011). The impact of counter-terrorism measures on Muslim communities. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 25(3), 151–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2011.617491

- Christiaens, E., Hardyns, W., & Pauwels, L. (2018). Evaluating the BOUNCEUp tool: Research findings and policy implications. IBZ Fedral Public Service Home Affairs.

- Coenders, M., Lubbers, M., Scheepers, P., & Verkuyten, M. (2008). More than two decades of changing ethnic attitudes in the Netherlands. Journal of Social Issues, 64(2), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00561.x

- Czwarno, M. (2006). Misjudging Islamic terrorism: The academic community’s failure to predict 9/11. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 29(7), 657–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100600702014

- de Goede, M., Simon, S., & Hoijtink, M. (2014). Performing pre-emption. Security Dialogue, 45(5), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614543585

- Dessel, A., & Rogge, M. (2008). Evaluation of intergroup dialogue: A review of the empirical literature. Conflcit Resolution Quarterly, 26(2), 199–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.230

- Dimaggio, P., Evans, J., & Bryson, B. (1996). Have American’s social attitudes become more polarized? American Journal of Sociology, 102(3), 690–755. https://doi.org/10.1086/230995

- Doosje, B., Loseman, A., & Van Den Bos, K. (2013). Determinants of radicalization of Islamic youth in the Netherlands: Personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 586–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12030

- Doosje, B., Moghaddam, F. M., Kruglanski, A. W., de Wolf, A., Mann, L., & Feddes, A. R. (2016). Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.008

- Ennis, C. D. (1991). Discrete thinking skills in two teachers physical education classes. The Elementary School Journal, 91(5), 474. https://doi.org/10.1086/461670

- Feddes, A., Mann, L., De Zwart, N., & Doosje, B. (2013). Duale Identiteit in een Multiculturele Samenleving: Een Longitudinale Kwalitatieve Effectmeting van de Weerbaarheidstraining Diamant. Tijdschrift Voor Veiligheid, 12(4), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.5553/TvV/187279482013012004003

- Feddes, A., Mann, L., & Doosje, B. (2015). Increasing self-esteem and empathy to prevent violent radicalization: A longitudinal quantitative evaluation of a resilience training focused on adolescents with a dual identity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(7), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12307

- Feddes, A. R., & Gallucci, M. (2015). A literature review on methodology used in evaluating effects of preventive and de-radicalization interventions. Journal for Deradicalization, 15/16(5), 1–27. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/view/33/31

- Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., & Bachman, B. A. (1996). Revisiting the contact hypothesis: The induction of a common ingroup identity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(3–4), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00019-3

- Gielen, A.-J. (2015). Supporting families of foreign fighters: A realistic approach for measuring the effectiveness. Journal for Deradicalization, 2(Spring/15), 21–48. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/viewFile/10/10

- Gielen, A.-J. (2018). Exit programs for female Jihadists: A proposal for conducting realistic evaluation of the Dutch approach. International Sociology, 33(4), 454–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580918775586

- Gielen, A.-J. (2019). Countering violent extremism: A realist review for assessing what works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how? Terrorism and Political Violence, 31(6), 1–19. DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2017.1313736

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

- Hogg, M. A., & Adelman, J. (2013). Uncertainty-identity theory: Extreme groups, radical behavior, and authoritarian leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 436–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12023

- Horgan, J., & Braddock, K. (2010). Rehabilitating the terrorists? Challenges in assessing the effectiveness of de-radicalization programs. Terrorism and Political Violence, 22(2), 267–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546551003594748

- Klar, Y., & Branscombe, N. R. (2016). Intergroup reconciliation: Emotions are not enough. Psychological Inquiry, 27(2), 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2016.1163959

- Lakhani, S. (2012). Preventing violent extremism: Perceptions of policy from grassroots and communities. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 51(2), 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2311.2011.00685.x

- Lamb, J. B. (2012). Preventing violent extremism; A policing case study of the West Midlands. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 7(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pas063

- Lub, V. (2013). Polarisation, radicalisation and social policy: Evaluating the theories of change. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 9(2), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413X662626

- Lum, C., Kennedy, L. W., & Sherley, A. (2006). Are counter-terrorism strategies effective? The results of the campbell systematic review on counter-terrorism evaluation research. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 2(4), 489–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-006-9020-y

- Malmros, R. A. (2019). From idea to policy: Scandinavian municipalities translating radicalization. Journal for Deradicalization, 18(Spring2019), 38–73. https://journals.sfu.ca/jd/index.php/jd/article/viewFile/185/139

- Mann, L., Doosje, B., Konijn, E., Nickolson, L., Moore, U., & Ruigrok, N. (2015). Indicatoren en Manifestaties van Weerbaarheid van de Nederlandse Bevolking Tegen Extremistische Boodschappen. Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid.

- Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Van De Grift, W. (2014). Development and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring pre-service teachers’ teaching behaviour: A rasch modelling approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(2), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.939198

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 20(3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546550802073367

- McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2014). Toward a profile of lone wolf terrorists: What moves an individual from radical opinion to radical action. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.849916

- Ministry of Justice and Security, National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism, and Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment. Action program integrated approach for Jihadism: Overview of proceedings and actions.

- Moghaddam, F. M. (2005). The staircase to terrorism: A psychological exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.2.161

- Nelen, H., Leeuw, F., & Bogaerts, S. (2010). Anti-terrorismebeleid en evaluatieonderzoek: Framework, toepassingen en voorbeelden. Boom Juridische uitgevers.

- Neumann, P. (2013). Options and strategies for countering online radicalization in the United States. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 36(6), 431–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2013.784568

- Noordegraaf, M., Dphil, S. D., Bos, A., & Klem, W. (2016). Gericht, Gedragen en Geborgd Interventievermogen? Evaluatie van de Nationale Contraterrorisme-strategie 2011-2015. University of Utrecht.

- Omlo, J., Bool, M., & Rensen, P. (2013). Weten wat werkt: Passend evaluatieonderzoek in het sociale domein. SWP.

- Paluck, E. L. (2010). Is it better not to talk? Group polarization, extended contact, and perspective taking in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(9), 1170–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210379868

- Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective. SAGE.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. SAGE.

- Pickering, S., McCulloch, J., & Wright-Neville, D. (2008). Counter-terrorism policing: Towards social cohesion. Crime, Law and Social Change, 50(1–2), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-008-9119-3

- Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN). Preventing radicalization to terrorism and violent extremism. RAN collection: Approaches and practices. Retrieved September, 16, 2019, from. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-best-practices/docs/ran_collection-approaches_and_practices_en.pdf

- Sageman, M. (2014). The stagnation in terrorism research. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(4), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.895649

- Schmid, A., Radicalization, De-Radicalization, Counter-Radicalization: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review (ICCT Research paper, The Hague, 2013).

- Schuurman, B., & Bakker, E. (2016). Reintegrating Jihadist extremists: Evaluating a Dutch initiative, 2013–2014. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 8(1), 66–85. DOI: 10.1080/19434472.2015.1100648

- Sklad, & Park. (2016). Results of a pilot study of a school based intervention aimed at universal primary prevention of radicalization by means of teaching social and civic skills.

- Ten Dam, G., & Volman, M. (2004). Critical thinking as a citizenship competence: Teaching strategies. Learning and Instruction, 14(4), 359–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2004.01.005

- Tsintsadze-Maass, E., & Maass, R. W. (2014). Groupthink and terrorist radicalization. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(5), 735–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2013.805094

- van San, M., Sieckelinck, S., & de Winter . (2013). Ideals adrift: An educational approach to radicalization. Ethics and Education, 8(3), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2013.878100

- Veldhuis, T. (2012). Designing rehabilitation and reintegration programs for violent extremist offenders: A realist approach. ICCT Research paper.

- Veldhuis, T., & Bakker, E. (2007). Causale Factoren van Radicalisering en hun Onderlinge Samenhang. Vrede en Veiligheid, 36(4), 447–470. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Edwin_Bakker4/publication/278241609_Causale_factoren_van_radicalisering_en_hun_onderlinge_samenhang/links/557d633008aeb61eae23e183/Causale-factoren-van-radicalisering-en-hun-onderlinge-samenhang.pdf

- Vermeulen, F. (2013). Suspect communities—targeting violent extremism at the local level: Policies of engagement in Amsterdam, Berlin, and London. Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(2), 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2012.705254

- Webber, D., Babush, M., Schori-Eyal, N., Vazeou-Nieuwenhuis, A., Hettiarachchi, M., Bélanger, J. J., Moyano, M., Trujillo, H. M., Gunaratna, R., Kruglanski, A. W., & Gelfand, M. J. (2018). The road to extremism: Field and experimental evidence that significance loss-induced need for closure fosters radicalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(2), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000111

- Wentzel, K. R., & Asher, S. R. (1995). The academic lives of neglected, rejected, popular, and controversial children. Child Development, 66(3), 754. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131948

- Williams, M., & Kleinman, S. M. (2014). A utilization-focused guide for conducting terrorism risk reduction program evaluations. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 6(2), 102–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2013.860183