Abstract

Some of the contemporary debates within urban geography is around the changing nature of neoliberalism, how cities have become the new sites for capitalist accumulation through new forms of neoliberal urban governance and whether or not this holds true for cities in the global South. This paper focuses on two cities in the global South, Cape Town and Medellin and uses safety and spatial transformation as lenses to interrogate this issue through an examination of spatial transformation efforts in the Voortrekker Road Corridor Integration Zone (VRCIZ). It seems that in Cape Town, more than Medellin, crime prevention efforts in certain parts of the city, as witnessed in the Voortrekker Road Corridor Integration Zone (VRCIZ), are driven largely by a desire to deal with crime and grime in order to attract private business. What is lacking in Cape Town is an explicit focus on addressing the underlying socio-economic causes of violence and crime. This will go a long way towards creating a sense of inclusion and belonging amongst Cape Town’s marginalised communities. The stories of Medellin and Cape Town point to the idea of different kinds of neo-liberalism(s); shaped by the particularities of the local socio-political, economic, cultural and institutional context.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper deals with topics such as systemic violence, its underlying root causes and programmes to address violence and crime in two cities of the global South, Cape Town and Medellin. This is relevant given the growing and persistent levels of violence and crime in Southern cities, linked to fast-paced urbanisation and growing socio-spatial inequality. After describing the Cape Town context and detailing the city’s efforts in bringing about socio-spatial transformation, the paper highlights several lessons which can be learned from Medellin’s efforts in this regard. These have important policy implications regarding the nature and content of socio-spatial transformation programmes in cities, a pressing concern for South African and other Southern cities. These insights are based on in-depth case study work conducted in the Voortrekker Road Corridor Integration Zone (VRCIZ). The paper, therefore, brings together theoretical and policy concerns with sound empirical evidence.

1. Introduction

Some of the contemporary debates within urban geography is around the changing nature of neoliberalism, how cities have become the new sites for capitalist accumulation through new forms of neoliberal urban governance and whether or not this holds true for cities in the global South. This paper focuses on two cities in the global South, Cape Town and Medellin and uses safety and spatial transformation as lenses to interrogate this issue. These two cities are chosen for the following reasons. They are similar in terms of population size and challenges related to high levels of inequality as well as drug-related violence and crime. Both cities have embarked on a concerted programme of spatial transformation in which transport infrastructure has played a pivotal role. In addition, scholars have pointed out how a range of spatial planning initiatives in these cities have been implemented within a context of neoliberal urban governance.

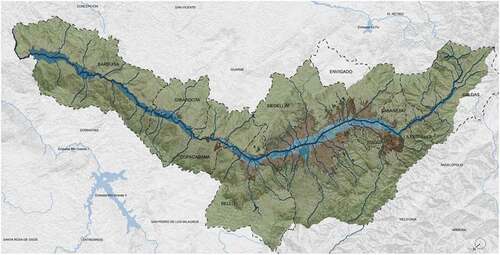

Cape Town is the second largest city in South Africa with a population of 4.52 million in 2018 (refer to Figure ). Cape Town as a city continues to be plagued by inefficient, fragmented and exclusionary spatial patterns inherited from Apartheid spatial planning. Internationally renowned for its natural beauty; Cape Town is also known as one of the most violent cities in South Africa and the world in terms of recorded rates of homicide. The municipal government, in response to national policy directives, has implemented a concerted programme of spatial transformation. Greater synergy between urban development and mobility through Transit-oriented development (TOD) is considered to be central to the spatial and social restructuring of the city.

Figure 1. Map of Cape Town with Voortrekker Road Corridor and Study Sites (Maitland, Kensington and Factreton/Windermere)

Medellin is the second largest city in Colombia with a population of 2.427 million inhabitants in 2018 (refer to Figure ). Medellin has experienced considerable population group, growing from a population of just over 350 000 residents in 1950 to more than 1.5 million people in 1985 (Orsini, Citation2016). This population growth was driven by migration from rural areas as many were attracted to the opportunities offered by industrial growth in Medellin. Due to its particular geography and location in the Aburrá valley, new arrivals to the city could not be accommodated and many settled on the surrounding mountain slopes in informally constructed housing. Medellin is one of the most unequal cities in Colombia with a gini coefficient of 0.5.Footnote1 In the 2000s the city embarked on a programme to address high levels of crime and violence driven to a great extent by socio-spatial exclusion and inequality (Orsini, 2016). The provision of affordable, safe transport through Medellin’s Metrocable was a central pillar of these reforms.

This paper uses violence and crime as a lens to interrogate Cape Town’s TOD-driven socio-spatial transformation programme. The focus on safety is significant as experiences and feelings of safety and security are an essential component of people’s quality of life. The City of Cape Town’s Social Development Strategy (City of Cape Town, Citation2013) states that “a safe and secure environment and the perception thereof, is a goal and enabler of social development. Safe communities are part of a ‘good life’ and provide an enabling environment where people may realise their potential” (City of Cape Town, Citation2013, p. 13).

This paper will present findings from a recent study focussing on the potential for spatial transformation in the Voortrekker Road Corridor Integration Zone (VRCIZ); one of the strategic corridors identified by the municipal government to effect spatial integration and transformation. Research was conducted in Maitland, Kensington and Factreton, three neighbourhoods which form part of the Western Area of the VRCIZ. In-depth interviews were conducted with a range of residents including those living in backyard shacks, informal settlements, owners of formal housing, tenants in apartment blocks across the three areas as well as informal traders, small business owners and other role-players like developers, school principals and government officials.

The research indicates a divergence between official plans and policies for the VRCIZ and the experiences of respondents, particularly in relation to crime and violence. Given the fact that the city of Medellin has gained worldwide recognition for successfully reducing high levels of violence through its social urbanism programme, it provides a useful reference point for the city of Cape Town in its efforts towards socio-spatial transformation.

The overarching question that this paper grapples with is “what do spatial interventions and how they are experienced within local communities tell us about urban governance within these two cities? Sub-questions include:

How do spatial transformation goals relate to broader social transformation imperatives in Cape Town?

Can a spatial integration agenda-driven overwhelmingly by a TOD focus, achieve the social transformation needed in Cape Town particularly in relation to the prevention of violence and crime?

Is it possible to address the underlying challenges of poverty, inequality and exclusion which drive insecurity and lack of safety within a neo-liberal economic context?

The paper argues that a TOD-driven programme aimed at improving socio-economic outcomes through closer integration between residential spaces, economic opportunity and other services is a significant, but not sufficient strategy to prevent violence and improve safety in a context of high levels of poverty, inequality and social exclusion. There needs to be an acknowledgement of the underlying psycho-social factors which produce and sustain high levels of violence. Appropriate socio-cultural interventions need to form part and parcel of efforts to effect spatial integration through the provision of public transport infrastructure. This means a more holistic approach and greater synergy and integration between those municipal departments driving spatial transformation and those responsible for social transformation and development. This should be accompanied by increased budget prioritisation of social development infrastructure and programmes and not the current approach which seem to suggest that spatial transformation efforts will somehow trickle down into improved social outcomes in cities. With regards to neo-liberal governance, the paper suggests that the cases of Cape Town and Medellin and their varied approaches to socio-spatial transformation and violence prevention efforts may point to the idea of different kinds of neo-liberalism(s) which are shaped by the particularities of the local socio-political, economic, cultural and institutional context as suggested by scholars like Brenner and Theodore (Citation2002).

2. Neoliberalism (s) in Cape Town and Medellin

Sites define neo-liberalism as a “set of politically inflected claims or discourses that reconfigure liberal conceptions of freedom, markets and individualism into powerful representations of contemporary capitalism” (Sites, Citation2007, p 118). Within the urban studies literature, the debate around neo-liberalism centres on whether or not neo-liberalism is to be construed as an ideology or whether in fact it constitutes a set of institutional practices. Linked to this is the debate around the notion of neo-liberalism as a set of predetermined ideological practices versus a constantly evolving process. Orsini (Citation2016) argue that neoliberalism or rather neo-liberalisation is constantly evolving and constructed and reconstructed through interaction between a host of individuals, groups, organisations and institutions across different scales. He argues that there is not one form of neo-liberalism, but different neo-liberalism(s), forms of neo-liberalisation or “varying neoliberal governances that barely resemble each other”. In this regard it represents:

“Constituted and reproduced historically and geographically specific forms in local settings

Complex cultural projects enabled by production and use of space

Not end states, but evolving processes” (Sites, 2002)

In this sense then, neoliberalism is fluid, evolving and constantly adjusting to changing socio-political, cultural understandings and economic local contexts.

In a similar vein, Wilson argues that neo-liberalism is “human crafted, complex and richly differentiated” (Wilson, Citation2004). Brenner and Theodore (Citation2002) define neo-liberalisation as a “historically specific, ongoing and internally contradictory process of market-driven socio-spatial transformation rather than a fully actualised policy regime, ideological form of regulatory framework and argue that neo-liberalism constantly evolves as it responds to its own disruptive, dysfunctional socio-political effects” (p353). One other significant question is around the role of the State within a neo-liberal economic paradigm. It has been argued for some time that neo-liberalism entails a reduced role for the state. A push towards greater privatisation and deregulation are intrinsic to neo-liberalism. This results in a retreat of the State specifically with regards to regulation of market practices and the provision of social services. However, some argue that the notion of a retreating State is a fallacy and that in fact “neo-liberalism impels rather than reduce state action as public resources continue to be put in the service of assisting capital, but in new ways” (Jessop, Citation2002, p. 781).

Thirdly, there is the question of the role of cities within neo-liberalism. Scholars like Brenner and Theodore (Citation2002) are adamant that over the last two decades cities have become the primary sites for capitalist accumulation as “cities are playing a crucial role in the contemporary re-making of political-economic space”. As neo-liberalism is constantly changing and evolving, cities have become important sites for the reproduction of neo-liberalism as they are important spaces for economic development and the engines of broader capitalist accumulation and elite consumption. However, it is also within cities that the internal contradictions of neo-liberalism characterised by unequal spatial patterns of development, economic inequality and social disruption are glaringly visible. Jessop argues that it is within cities “that the various contradictions and tensions of actually existing neoliberalism are expressed most saliently in everyday life” (Jessop, Citation2002, p. 452).

Cape Town has often been characterised as a neoliberal city (IDRC, Citation2002; McDonald, Citation2008; McDonald & Smith, Citation2004; Samara, Citation2010). One of the areas in which this is particularly evident is in the realm of crime control. According to Samara, “market-driven neoliberal governance underpins development and urban renewal within post-Apartheid Cape Town with the consequence that crime has assumed a priority within development discourse”. Within a neo-liberal economic paradigm, crime and violence are seen as challenges not so much because of the socio-economic burden it imposes on the state and poor households especially, but because of the impediment, it presents to capitalist accumulation and the attraction of global capital investment. Often, areas within cities which are identified as areas of economic potential do not realise this potential as firms, both local and international, are reluctant to locate themselves in these areas due to crime, grime and violence. With regards to Medellin, whereas its social urbanism programme has been hailed by many urban scholars as a “miracle”, some are more sceptical and argue that this has been used as a facade to advance a neo-liberal market-centred agenda (Franz, Citation2016; Moncada, Citation2016). This will be further interrogated below with a closer look at socio-spatial transformation programmes and the nature of their implementation in Cape Town and Medellin with a specific focus on their outcomes with regards to crime and violence reduction.

3. Cape Town and the need for socio-spatial transformation

South African cities today are still marked by social and spatial fragmentation as well as unacceptably high levels of inequality. This is reinforced by low-density urban sprawl and unequal land distribution patterns. These result largely from Apartheid spatial planning policies but have been further entrenched in recent times by inappropriate regulation, confusing and often conflicting policy priorities and an unequal land market. According to Dewar (2004)Footnote2 the interaction between Apartheid spatial planning and the “modernism” urban planning ideology, with its emphasis on suburban development, separation of urban activities of work and leisure as well as the prioritisation of technical efficiency over social and environmental imperatives have profoundly impacted on the urban spatial form.

Since the advent of democracy in 1994, the South African government has implemented a myriad of new laws and policies in an attempt to reverse the socio-spatial legacy of Apartheid. However, despite national policy imperatives calling for sustainable human settlements with an emphasis on higher density developments on well-located land, better integration between land use, transportation and the provision of infrastructure and services; the delivery of subsidised housing has not been in line with these policy prescriptions. The primary reasons for this are the exorbitant cost of well-located land and the availability of more affordable land on the urban periphery as well as insufficient subsidy amounts to build at higher densities to offset higher land costs. According to Pieterse (Citation2014)Footnote3 “we have had a lot of policy rhetoric about the virtues of high density, mixed-use, mixed-income living, while investments have gone in the opposite direction”. He further argues that even though Breaking New GroundFootnote4 (BNG) (2004) and other policy documents speak to the importance of higher density, mixed-use and mixed-income housing delivery, BNG was not supported by a transformation of the fiscal arrangements of the housing subsidy regime to facilitate this new direction.

So despite a range of legislation, policies and strategies like the new Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act (SPLUMA) (2013), Spatial Development Frameworks (SDFs), and Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) to name a few, which all speak to greater social and spatial integration, the Integrated Urban Development Framework (IUDF) argues that “spatial fragmentation of settlements, with resulting inefficiencies remain” (CoGTA, Citation2014, p. 33).Footnote5 This stems largely from a lack of clarity on exactly how to operationalise and achieve the goals identified in said policies and legislation. This gap between policy intention and development outcomes impacts greatly on social and environmental sustainability and has a significant bearing on the quality of life of the majority of urban residents.

Cape Town as a city is plagued by the same inefficient, fragmented and exclusionary spatial patterns inherited from Apartheid as “90% of the city is still largely dominated by an urban structure that deliberately reduced interaction between different ethnicities and social classes to a minimum through urban planning and social engineering” (Provoost Citation2015: 90).Footnote6 Persistent spatial inequality imposes a considerable cost on the state, environment and increase the socio-economic burden and marginalisation of poor households and individuals. According to the African Green City index; at 1500 people/km2 Cape Town is the least dense out of 15 African cities, compared to an average of 4600 people/km2 for the 15 cities surveyed and an 8200 people/km2 average for Asian cities.Footnote7 This translates into an average of 30% additional spent in terms of infrastructure provision and maintenance. Public transport subsidies for Cape Town is more than double the amount dedicated to housing, with an amount of R696 236 000 budgeted in 2013 for public transport by the Western Cape Department of Transport.Footnote8Footnote9 A recent report which compares the carbon footprint of Cape Town and Sao Paulo states that Cape Town’s carbon emissions of 10.21 CO2 per capita is higher than the national average of 9.91 CO2 per capita, which it attributes largely to a lack a connectivity in the city (Da Schio & Brekke, Citation2013).

Poor households are disproportionally affected by spatial fragmentation; not only in economic terms, but also in terms of social costs. A survey comparing travel times between private car and public transport in Cape Town found that average travel time in Cape Town is 90 minutes, significantly higher than the global average of 70 minutes. The average for public transport, which is what the majority of low-income households in Cape Town make use of, is 110 minutes (Hitge & Vanderschuren, Citation2015). Long hours spent travelling to and from work impacts negatively on family life and leaves little time for any other social activities.

Dormitory townships with minimal access to services, let alone much needed social and recreational infrastructure and programmes, high rates of poverty and unemployment, particularly youth unemployment, provide an ideal environment for social dysfunction including high rates of interpersonal violence and crime to thrive (Bauer, Citation2010; Un Habitat, Citation2007).

4. Violence and crime in Cape Town

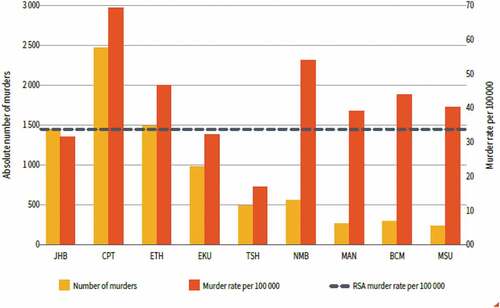

Cape Town is the most violent city in South Africa according to the 2018/2019 State of Urban Safety Report (SACN, Citation2017) (refer to Figure ). Rates of murder, robbery and property-related crimes in Cape Town are highest amongst the nine major cities in South Africa (ibid). This is so despite slower population growth, lower levels of poverty, income inequality and youth unemployment than other major urban centres in South Africa which are the factors usually associated with high levels of violence and crime in cities.

SACN (2019) “The State of Urban Safety in South Africa Report”, 2018/2019

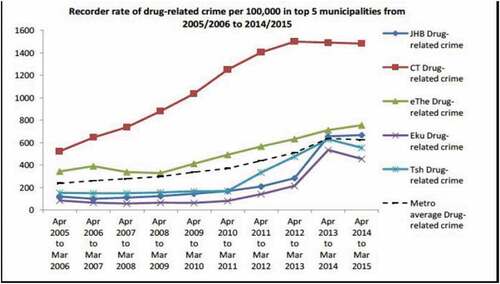

Figure 4. Top 5 municipalities in terms of recorded drug-related crime per 100 000 of the population

SACN (Citation2017) “The State of Urban Safety in South Africa Report”, 2017

The 2018/2019 State of Urban Safety in South Africa report identifies access to alcohol, drugs and firearms as the main factors associated with high levels of crime and violence in Cape Town. Although by no means the only factor accounting for high levels of violence and crime in Cape Town, gangs and the associated drug trade are important considerations when trying to make sense of the particularity of violence and crime in Cape Town (refer to Figure ). The City of Cape Town’s (Citation2013) identifies gangs and substance abuse, particularly in relation to young people and their development as an essential focus area in the quest to create safe households and communities. This is so because according to the Department “gang-related activities fuel a large amount of crime in the City and in addition, there are strong links between gangs and drugs, fire-arms, prostitution and violent crimes (City of Cape Town, Citation2013, p. 15).

The number of gang members in Cape Town are estimated to be over 100 000 according to the South African Police Services.Footnote10 The Western Cape Police service estimate that one-third of all attempted murders in the province can be attributed to gang violence (Goga et al., Citation2014). The causes and manifestations of violence and crime are multi-dimensional. The same holds true for gang violence which in the case of Cape Town is rooted in the city’s particular historical, socio-economic and political context. Jensen (Citation2005) and Howell (2018)Footnote11 argue that Cape Town gangs are products of history, identity and necessity and a response to social isolation, powerlessness and economic exclusion experienced by low-income communities. The intensification of gang formation and activity in Cape Town can be traced back to South Africa’s Apartheid history and specifically the forced removal of Coloured families to the Cape Flats, which saw the destruction of informal home-based economic activity and crucial social support networks like the extended family (Pinnock, Citation1984 in Goga et al., Citation2014).

“Deprived of work opportunities, torn from the social support of the extended family unit, and thrust into a dangerous, dysfunctional and racist state, many young men turned to gangs for protection, opportunity and a sense of belonging” (Goga et al., Citation2014, p. 3)

Besides providing protection, access to opportunity and a sense of belonging, Pinnock (Citation1997) argues that gang affiliation, activity and the rituals and symbols associated with it also fulfils the need for a “rite of passage” which many adolescents, boys in particular, desire. The period post-1994 which was accompanied by an opening up of South Africa to the rest of the world also saw an evolution of the structure and nature of gangs from street gangs to sophisticated crime syndicates as well as a diversification in crime activities to include prostitution, the illegal abalone and crayfish trade, illegal protection arrangements and nightclub security (Kinnes, Citation2000; Goredama & Goga, Citation2014; Lambrechts, Citation2012).

Despite the acknowledgement of the underlying socio-economic drivers of violence and the need for longer-term efforts to prevent violence and crime, in reality, state responses to violence and particularly the war on gangs in Cape Town are still characterised by a security-driven, policing mindset whilst developmental aspects, such as fostering socio-economic inclusion and a sense of belonging, are being downsized or even rolled back (Jensen, Citation2010). Similarly, Samara (Citation2010) argues that “the practice of policing under a neo-liberal governance framework, in which security, its understanding and practice are closely linked to the growth requirements of the markets raises questions about the possibility of even sustained crime reduction, much less development in the townships that most residents of the city call home”.

5. Interrogating Cape Town’s vision for socio-spatial transformation

One of the key outcomes of the City of Cape Town’s Spatial Development Framework (City of Cape Town, Citation2018)Footnote12 is the creation of an inclusive, integrated and vibrant city. Greater synergy between urban development and mobility through densification and the provision of quality public transport is considered to be central to the spatial and social restructuring of the city. This vision is again reiterated in the new Municipal Spatial Development Framework (City of Cape Town, Citation2018) for Cape Town:

“The City is intent on building—in partnership with the private and public sector—a more inclusive, integrated and vibrant city that addresses the legacies of apartheid, rectifies existing imbalances in the distribution of different types of residential development and avoids the creation of new structural imbalances in the delivery of services. Key to achieving this spatial transformation is transit-oriented development (TOD) and the densification and diversification of land uses.”

(Municipal Spatial Development Framework (MSDF) for Cape Town, (City of Cape Town, Citation2018), p. 35)

The City of Cape Town (Citation2018, p. 100) defines TOD as “a multifaceted and targeted strategic land development approach to improved urban efficiencies and sustainability by integrating and aligning land development and public transport services provision. It promotes inward growth and compact city form with an emphasis on building optimum relationships between urban form, development type, development intensity, development mix and public transport services to create a virtuous cycle of benefits over the long term”.

TOD is a planning approach centred on improved integration between transport and land use and aims to encourage higher density, compact, mixed-use developments around transport interchanges (Cunningham, Citation2012; SACN, Citation2014). Proponents of this approach argue that it has the potential to combat urban sprawl, reduce distances between employment and residential development, provide a mix of housing options and encourage integration and environmental sustainability. TOD also offers location efficiency and allows residents to offset their housing costs against transport costs thereby making housing more affordable. Guthrie and Fan argue that “the location efficiency of TOD can be especially beneficial to low-income residents if affordable housing is included in TOD projects” (Guthrie & Fan, Citation2016, p. 104). By the same token high demand for housing around transport interchanges and the resultant increase in property prices can actually exclude low-income families and individuals. Holmes and van Hemert (Citation2008) therefore call for “customized zoning” or inclusionary zoning to encourage varied housing options, specifically affordable housing, in order to ensure social inclusion.

In line with national policy imperatives, the City of Cape Town has identified three Integration Zones, the Metro-South East Corridor Integration Zone (MSEIZ), the Voortrekker Road Corridor Integration Zone (VRCIZ) and the Blue Downs Integration Zone as critical tools for the realisation of a more inclusive and integrated Cape Town. According to National Treasury, integration zones are “prioritised spatial focus areas within the urban network that provide opportunities for coordinated public intervention to promote more inclusive, efficient and sustainable forms of urban development” (National Treasury, Citation2013, p. 8).Footnote13 The identification of integration zones is meant to allow for targeted public investment in specific spatial areas of opportunity in order to attract private investment. It will also provide different spheres of government with the necessary tools to “measure and manage the form and pace of change in spatial form” (ibid).

There seems to be an implicit assumption within the MSDF and other strategic policy documents like the Integrated Public Transport Network Plan (2032) as well as the city’s City of Cape Town, Citation2017a that spatial integration through a TOD approach will not only improve urban efficiency and sustainability but will also address inequality and in so doing bring about social transformation and address the structural conditions which foster and perpetuate much of the dysfunction manifesting in high levels of interpersonal and community violence as well as property-related crime in Cape Town. Pieterse (Citation2014) however, argues that “the current model of TOD development boils down to a 20–30 year agenda to lay the basis for real-estate driven urban integration and reconfiguraiton along the transit corridors” and doubts that this approach is a viable strategy to deal with Cape Town’s intractable socio-spatial challenges.

Although spatial policies and plans seem to make an implicit link between spatial integration through TOD and improved socio-economic outcomes, in reality the department tasked with addressing social transformation challenges within the municipality is the Department of Social Development and Early Childhood Development. This Department’s 2013 Social Development strategy aims at addressing social challenges like gangsterism, high rates of violence, substance abuse, particularly drug abuse, youth unemployment and homelessness and to effect social inclusion. The strategy has five high-level objectives which are focussed on using the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) as a primary vehicle to maximise income-generating opportunities for those excluded from the economy, employing holistic strategies to combat gangs, substance abuse and youth development in order to create safe households and communities, improving access to infrastructure and services like primary health care, early childhood development and housing opportunities for those most marginalised, to foster social integration and inclusion by combating spatial segregation and promoting social interaction and to mobilise resources for social development (City of Cape Town, Citation2013).

There seems to be a disconnect between spatial and social development policies which both aim to address socio-spatial inequalities through social integration. Both sets of policies speak to the importance of a transversal approach to effect integration and coordination across different departments and spheres of government. The social development strategy, however, acknowledges that “departments and directorates often see the challenges they face in terms of their own sphere of activity, providing isolated, sector-specific responses to social issues”. Moreover, “social development is often viewed as the domain of one specific directorate concerned with relatively small, discrete projects rather than viewed broadly as encompassing all of the City’s work”.

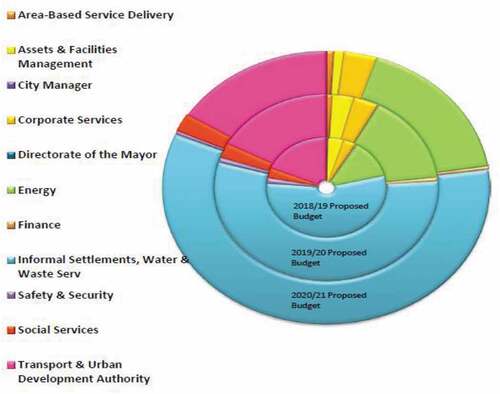

This lack of clear and focussed programming and prioritisation of social development imperatives is also reflected in the municipality’s proposed budget for 2018/2019 (refer to Figure ). Whereas the increased budget allocation for informal settlement upgrading is noteworthy and encouraging, it is concerning that the budget allocation for social services and safety and security is almost negligible. The other big winner in terms of budget prioritisation is the transport and urban development authority tasked with driving the City’s TOD-driven spatial transformation vision.

6. The Research study—potential for socio-spatial transformation in the Voortrekker Road Corridor Integration Zone

6.1. Research methods

In trying to gain a deeper understanding of the City’s Spatial Transformation programme and how it is understood and received within a local neighbourhood context research was conducted in the Western area of the Voortrekker Road Integration Zone (VRCIZ). The objectives of the research were to get a sense of the prevailing socio-economic conditions, current mobility patterns as well as patterns in the residential property market and how they relate to housing need and demand in the area. We were also interested in gaining a better understanding of the development aspirations of those who reside and conduct business in the area and how these compare with the vision of city officials and politicians as outlined in major policy documents. Finally, we wanted to gain insight into the perceptions of role-players concerning the main challenges standing in the way of their aspirations being fulfilled.

In-depth interviews were conducted with residents, informal business owners and commuters in order to garner a more fine-grained understanding of their everyday practices and routines. Other respondents included private developers who provided another perspective of the area, their vision for its development and the challenges/obstacles they foresee in terms of advancing socio-spatial integration through the VRCIZ. City officials and role-players involved in the creation of the strategy and investment plan for the corridor as well as principals at some of the schools in the three study areas were also interviewed. A desktop analysis of the City of Cape Town’s plans for the corridor as well as a review of relevant polices were conducted. This was done to identify the development goals for the corridor as well as challenges to the realisation of these goals.

Questionnaires were tailored to the different categories of residents, i.e. homeowners, back yard dwellers, occupants of apartment blocks, and informal settlement dwellers. Themes covered in questionnaires included biographical details; historical profile; socio-economic profile; housing profile; household services; public facilities, and development issues. Fieldwork interviews were also conducted with commuters and informal/small businesses. Themes covered in interview guides with commuters were mobility patterns (from/to); reason for travelling; residential preferences for employed commuters; preferred mode of transport; travelling time; accessibility of public transport; costs of travelling, and facilities/services needed in the area. The table below provides a breakdown of the categories and of respondents per study area (see )

Table 1. Categories and number of respondents per study area

Data were analysed using an inductive approach entailing rigorous mining of the various sources of data. Colour coding was used to identify recurring themes across interviews conducted with different stakeholders including residents from the three study areas. A number of themes were identified. These related to perceptions around densification, affordable housing and the opinions of different respondents about what constitutes affordable housing, issues of mobility; quality of life including access to social and physical infrastructure and services and experiences of violence and safety, feeling of belonging and inclusion as evidenced in the municipality’s engagement with residents around development plans for their neighbourhoods.

7. Research findings—residents’ vs city’s vision for VRCIZ in relation to violence and safety

Although not an explicit focus of the study, a lack of safety and concerns over violence and crime were consistently mentioned by respondents from across the three study areas. For those living in backyard shacks and informal settlements, safety was one of top desires for development after housing and sanitation as captured in the quotes below.

“People running government are ignorant about security situation in our areas, and perhaps lack of finance in terms of renovating buildings” (Maitland resident)

“Safety is the main concern” (Maitland resident)

“Difficult to answer because I don’t walk around much, but it’s virtually dangerous in all places. I don’t walk around much” (Factreton resident)

“Need green spaces and original vegetation for oxygen and nature therapy because this is a traumatised community. There is also cable theft and people are murdered inside their homes and cars are stripped of tyres” (Kensington resident)

“Cape Town library is good, Maitland isn’t good and is not safe; not enough resources” (Maitland resident)

Safety and security concerns were often linked to social challenges like drug abuse, gangsterism, youth unemployment and a lack of activities and facilities to engage the youth in productive ways. As observed in the quotes below, residents indicated a desire for a better future for their children and interventions which would break the inter-generational and inter-connected cycle of poverty, violence and deprivation.

“I am nobody. I want my kids to be somebody. (Factreton resident)

Stay in school, be a doctor or a lawyer. “

“There should be more facilities for youth to avoid the drugs trap” (Maitland resident)

Safety was for example, also mentioned as one of the main reasons for under-use of public facilities like parks.

“Bad quality and not safe. City of Cape Town should have independent contractors to maintain these spaces on a monthly basis”

Nearest park is not in good condition and not safe due to drug dealing” (Factreton resident)

“Not safe because drug addicts sit in parks and parks not in good condition because drug addicts break everything” (Factreton resident)

“11th Street and 5th Avenue park in very bad condition. There’s nothing there, its also not safe because youth smoke drugs there” (Kensington resident)

Government was seen as non-responsive, and respondents expressed a real sense of being forgotten. This was reinforced by a lack of a clear communication and engagement strategy from the city government.

“Attention should be paid to the people in this area because they’re ignored. Someone should encourage and teach them to get out of their circumstances “(Kensington resident)

“Government does not care about Facreton” (Factreton resident)

“Ward councillors should take more interest in their area. We only see them during election campaigns. We don’t know them” (Factreton resident)

The municipality’s vision for the VRCIZ, on the other hand, is centred on spatially targeted interventions in areas of economic potential in order to leverage private investment (City of Cape Town, Citation2014). Within this approach, “crime and grime” is viewed as a major disincentive to investment within the area as it contributes to increased risk. Interestingly the baseline study conducted by the municipality to inform their investment strategy for the VRCIZ also identifies safety as a concern; however, the issue is viewed more from a traditional urban regeneration perspective and the focus is therefore on eradicating “crime and grime” in order to attract private investment into the VRCIZ. There seems to be no acknowledgement of and therefore very little by way of concrete strategies, beyond a statement about “inclusive regeneration”, to address the underlying social challenges which contribute to and sustain violence and crime. The municipality’s strategic plan for the VRCIZ envisages that inclusive urban regeneration and growth will take place according to the principals of TOD and possible displacement which may occur as a result of regeneration will be mitigated through the development of “inclusive residential opportunities and a range of commercial premises” (City of Cape Town, Citation2014). Yet, according to the plan, the bulk of the estimated excess future housing supply would cater to the GAP,Footnote14 social housing and middle-income brackets. This means that “accommodation of households living in the under minimum wage and indigent households’ segment within the VRC remains relatively poor” (City of Cape Town, Citation2014, p. 130). Backyarders and those in informal settlements, the majority of whom reside in Factreton, Kensington and Maitland (the three study areas) will therefore not be included in new housing opportunities envisaged for the VRCIZ.

This “crime and grime” private investment-centred approach to address pressing social issues is very different to the social urbanism approach adopted in Medellin. A comparison is appropriate as Cape Town and Medellin face similar challenges in terms of levels of inequality and violence. In Medellin, the starting point for addressing social and spatial segregation and fragmentation was not a desire to do away with crime and grime in order to attract private investment, but rather to adopt a more developmental approach in terms of addressing the underlying drivers of violence and crime; i.e. income and spatial inequality. The social urbanism programme “included a set of policies & tools to mitigate segregation and inequality, connecting and integrating the city through instruments of physical and social inclusiónFootnote15 (Orsini, 2016).”

The section below will provide a brief overview of Medellin’s social urbanism programme.

8. The Medellin “Miracle”

Medellin was infamously known as the most violent city in the world. At the height of its violent past, it had a homicide rate of 381 murders for every 100 000 of the population in 1991 (Brand Citation2010). This was the highest in Colombia and one of the highest in the world. In the 2000’s under the leadership of Mayor Sergio Fajardo, the city introduced a socio-spatial transformation programme called “social urbanism”. This programme was pioneered by Mayor Fajardo between the years 2003–2007 and consists of a number of well-integrated interventions incorporating both preventive and control-oriented activities (Patino & UN Habitat, Citation2011). It encompasses a more comprehensive set of elements than other crime-prevention planning methods like Defensible Space for example, yet also has a focus on physical improvements in the built environment. The prime objective for the introduction of the social urbanism programme in Medellin was to address the city’s high levels of violence as well as inequality. This programme represented, according to Mayor Fajardo, a new social contract between Medellin’s government and the city’s residents. This programme that earned Medellin the accolade for “the most innovative city in the world in 2013” has been hailed by many as a “miracle” and a best-case example for urban transformation and the improvement of urban safety (Brand Citation2010; Brand & Davila, Citation2011; Hernandez-Garcia, Citation2013; Patino & UN Habitat, Citation2011; Scruggs, Citation2014; Turok, Citation2014).

Some of the defining features of social urbanism are investment in architecturally appealing buildings, improvements in public spaces and the provision of social services and infrastructure such as schools, libraries, recreational and cultural facilities. These are located in the poorest neighbourhoods in order to create a sense of place, local identity and promote spatial equality in the city. Importantly these interventions were also aimed at improving residents of Medellin’s sense of social inclusion and belonging. The programme saw a substantial investment in safe, high-quality public transport and the construction of new housing projects around stations which was one of the defining features of the social urbanism programme. Not only did this contribute to spatial integration by connecting badly located, inaccessible areas to the rest of the city, but again also contributed to a sense of inclusion and belonging (Turok, Citation2014). Some of the more practical benefits of this transport infrastructure like Medellin’s aerial cable-car, the first of its kind, was a decrease in transport costs and improved mobility for poor residents (Brand & Davila, Citation2011).

Most importantly, the success of social urbanism is underpinned by an awareness of the root social causes of crime and violence and recognition of the need for more holistic planning to address these (Patino & UN Habitat, Citation2011). This is in sharp contrast to a more security, policing-driven approach as is the case in Cape Town which does very little by way of addressing the root causes and drivers of urban violence. The introduction of social urbanism in Medellin set in motion “an explicit confluence of safety policies, with generation of public spaces, urban renewal, and socio-cultural programmes” (Patino & UN Habitat, Citation2011, p. 13). Good governance and a focus on transparency, community participation and citizen ownership are also important elements of social urbanism. This was accompanied by other principles such as mature political leadership, extensive dialogue and civil society engagement, devolved responsibilities to all levels of government and institutional capacity building of various sectors of society (Turok, Citation2014).

Despite being hailed as a miracle, social urbanism has, however, seen a fair number of challenges and shortcomings. It has been criticised by some as having very little significance beyond its symbolic value in terms of the contribution towards social inclusion and the creation of a sense of belonging amongst socially, economically and spatially marginalized communities (Brand & Davila, Citation2011). One of the biggest criticisms levelled against the programme is that it achieved very little in terms of economic development and improving the material conditions of poor residents (Brand 2010; Fukuyama & Colby, Citation2011; Scruggs, Citation2014). This is argued is because the programme did not have an explicit focus from the outset on addressing structural conditions like unemployment, poverty and inequality. Sustainability and institutionalization of the model have also been raised as a concern (Patino & UN Habitat, Citation2011). Another shortcoming of the programme has been in terms of sustained and meaningful community participation, which while prominent during the earlier stages, was not carried through all the way (Hernandez-Garcia, Citation2013).

However, despite its shortcomings, as a spatial transformation programme which delivered significant social benefits, it does offer some important lessons to Cape Town, a city which has the dubious reputation of being the most violent city in South Africa and 11th on the list of the most dangerous cities in the worldFootnote16 with a homicide rate of 66.36 per 100, 000 residents according to the Mexican Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice. The following section will highlight 4 key insights from Medellin’s social urbanism programme in relation to socio-spatial transformation and violence reduction which may be instructive for Cape Town.

9. Discussion—social urbanism in Medellin, Colombia—lessons for Cape Town?

This section will highlight four key differences between Cape Town and Medellin’s conception of socio-spatial transformation, the values and aims which underpin each city’s socio-spatial transformation programmes and their implementation as well as the outcomes observed in terms of crime and violence reduction and social inclusion.

A different conception of violence and acknowledgement of it being rooted in socio-spatial inequalities and therefore an approach focussed on addressing the root causes of violence rather than a security and policing-driven approach which still dominates locally (Sotomayor, Citation2015, p. 379).

This is reflected in the budget priorities where between 2004 and 2013, nearly 86% of all municipal expenditures in Medellin was devoted to social investment (Moncada, Citation2016). In contrast, in Cape Town, Samara (Citation2010) argues that despite efforts to reform the apartheid-era criminal justice system and incorporate the fight against crime both conceptually and in practice into a broader social development framework, policing and urban renewal in Cape Town remain linked through an approach to security in which dangerous populations threaten economic growth and social stability. (Samara, Citation2010, p. 198).

So whereas some commentators are critical of how the Medellin miracle has become a branding and marketing tool for the city and argue that social urbanism has not brought about a complete change in poor communities material conditions, it has nonetheless transformed how the state engages with poor residents and has given them a sense of inclusion and belonging; the importance of which is not to be under-estimated.

bSpatial targeting and prioritisation of a different kind

Cape Town’s spatial targeting is based on the selection of areas with economic potential, but which for some reason are not performing as well as they should economically, this is certainly the case with the VRCIZ. This is very much in line with a neo-liberal urban governance practice which favours the creation of ideal conditions for capitalist accumulation over social development goals like eradicating poverty and social ills like violence, crime and gangsterism.

In Medellin the areas chosen for public investment were those with the lowest quality of life and human development index, as well as high homicide rates, signifying a different approach to spatial targeting and prioritisation (Sotomayor, Citation2015, p. 384).

cTransport/mobility-driven spatial transformation approach versus transport as a component of a more comprehensive set of interventions

Another significant difference between Cape Town and Medellin’s approach to spatial integration and social transformation is in the way in which the role of transport infrastructure is being conceived. In Medellin, transport/mobility is a component of a more comprehensive set of interventions which includes the provision of quality social infrastructure like library parks, schools and cultural facilities in poorer, more violent areas of the city and improved urban governance through a set of democratic practises. In Cape Town there seems to be a perception that once the city is spatially integrated through a TOD approach, then social transformation and reduction of poverty and inequality will automatically follow. There is very little by way of a comprehensive, multi-faceted and holistic approach to deal with deep-seated social challenges which drive and sustain exceptionally high levels of violence and crime in Cape Town.

dParticipatory planning—accountable participation and clear communication with the community

In Medellin local community participation in the integrated urban projects ranged from identifying problems and opportunities through field trips, to the formulation and approval of projects, to the use of participatory design practices such as workshops of imaginaries. This meant that each integrated urban project forged a different identity and place-making practice, supporting the diversity of each site (Sotomayor, Citation2015, 381). Participatory budgeting was also an important component of the reconfiguration of state–society relationships in Medellin effected through its social urbanism programme.

“From a social perspective the goals were to identify processes and dynamics that emerge from the community and from different stakeholders working to foster local participation and appropriation before, during and after the interventions. (Castro & Echeverri, Citation2011, p. 100)

This is very different to the Cape Town case where a set of very complex spatial transformation policies and a range of catalytic projects have been identified and planned with minimal involvement of the communities that they supposedly aim to serve. This perception was voiced by respondents in Maitland, Kensington and Facreton and the resultant feelings of being ignored and excluded expressed by several respondents. There is a well-established literature advocating the importance of actively engaging community members in planning and implementing development interventions which affect their lives (Gaventa, Citation2002; Imparato & Ruster, Citation2003; Moser, Citation1989; UN-Habitat, Citation2014; Watson, Citation2014). Some have warned how the notion of participation has been hijacked by the neo-liberal agenda where communities are merely consulted about development projects, but are not actively participating in the decision-making processes at various stages of planning and implementation (Edigheji, Citation2004; Leal, Citation2007; Miraftab, Citation2004; Miraftub, Citation2004; Monno & Khakee, Citation2012). However, involving communities as active participants in development projects advances participatory governance and enable residents to realise their rights and fulfil their social responsibilities as active citizens. This is also crucial for fostering a sense of belonging and social inclusion amongst residents. This sense of belonging, it is argued, is a building block of social cohesion at different scales (community, neighbourhood and society) and is part and parcel of communal strategies to address high levels of violence and improve safety within neighbourhoods (Brown-Luthango, Citation2015, Citation2019; Duncan et al., Citation2003; Sampson, Citation2003).

In the final analysis, Cape Town and Medellin are cities which are striving to bring about socio-spatial transformation which would see an improvement in the quality of life of their residents. This has to be achieved within a constrained economic environment where city governments have to make careful decisions about prioritisation and where to invest financial and other resources. What this paper argues is that in Medellin, there was a firm acknowledgement of the need to address high levels of violence in an intentional, focussed and targeted manner through investment in transport as well as the provision of socio-cultural infrastructure and programming. There was also an acknowledgement of how the city’s spatial structure contributed to feelings of isolation, marginalisation and exclusion and this again was addressed in a targeted manner through the provision of infrastructure, services as well as a different way of engaging with citizens.

eNeo-liberalism and socio-spatial transformation in Cape Town and Medellin

In Medellin, there seems to have been a co-existence of market-based economic goals and socio-political imperatives. Brand (Citation2013) argues that the goal behind the social urbanism programme was the social imperative of restoring the social fabric of Medellin which had been destroyed by violence through fostering social inclusion and symbolic integration, a sense of dignity, greater community self-esteem and an authentic sense of inclusion—“the aspiration was to build, literally, a new social contract through the provision of spaces of citizenship, places for democracy and environments of conviviality (Brand, Citation2013, p. 6). Medellin, it seems, has aimed to integrate neo-liberal, marked based imperatives with social development goals. Moncada (Citation2016) illustrates how the city was able to achieve the twin ambitions of becoming, on the one hand, more democratic, equitable and inclusive through redistributional infrastructure and anti-poverty programmes and on the other hand, a better fit for attracting foreign capital investment through the internationalisation of the Medellin model. He argues that Medellin’s success in combating urban violence was based on a unique alignment of business and wider political interests (ibid). This, it is argued, produced a virtuous cycle where reduction in levels of urban violence and favourable economic conditions improved the city’s attractiveness to foreign direct investment which increased tenfold between 2002 and 2009. This in turn generated an increase in revenue; a large proportion of which was invested into social programmes aimed at strengthening violence prevention efforts.

Franz (Citation2016) is much more critical of Medellin’s social urbanism programme and argues that what is often referred to as a “urban miracle” is only an illusion. This is because in Medellin “good governance” practices were used as a facade to advance a neo-liberal economic agenda and to insert Medellin into the global economy. This according to Franz is illustrated by the fact that even though Medellin experienced the fastest economic growth between 2002 and 2009, even compared to national economic growth, the city still had the highest levels of unemployment and remains one of the most unequal cities in Colombia. Whatever jobs were created in the city, were at the lower end of the value chain and therefore did not bring about a fundamental transformation in class relations. This begs the question; can fundamental socio-economic transformation be achieved within a market-centred economy driven by a neo-liberal agenda?

Parnell and Robinson (Citation2012) question the narrowness of a purely neo-liberal economic analysis of development to understand cities in the global South. Using South Africa as an example the authors illustrate how in the midst of pursuing a more neo-liberal economic approach through its Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) Policy (1996), the country simultaneously implemented an extensive social welfare programme through the provision of social grants, one of the largest subsidised housing programmes in the world and the indigent policy implemented by municipalities. This begs a number of questions which are possibly beyond the scope of this paper. Are these social interventions in the context of a capitalist, neo-liberal economic environment merely piecemeal? Is a complete restructuring of the economy needed to achieve “real” socio-economic transformation or can neo-liberalism be given a more human face through the implementation of targeted social welfare programmes and what role can cities play in this regard?

It would seem that in Cape Town, more so than in Medellin, crime prevention efforts in certain parts of the city, as witnessed in the VRCIZ, are driven largely by a desire to deal with crime and grime in order to attract private business. What is lacking in Cape Town is an explicit focus on addressing the underlying socio-economic causes of violence and crime and a focussed programme of redistributing the benefits of economic growth more equitably through targeted social infrastructure delivery programmes in poorer parts of the city where interpersonal and gang-related violence are most rife. This will go a long way towards creating a sense of inclusion and belonging amongst Cape Town’s marginalised communities.

The stories of Medellin and Cape Town maybe point to the idea of different kinds of neo-liberalism(s) which are shaped by the particularities of the local socio-political, economic, cultural and institutional context as suggested by scholars like Brenner and Theodore (Citation2002).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mercy Brown-Luthango

Dr Mercy Brown-Luthango is a senior researcher at the African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town. She is a sociologist with extensive research experience. Her main research focus is on the creation of sustainable human settlements with a particular interest in the management of urban land and housing and access to services and infrastructure for poor urban residents.

Notes

1. Warner, F and Sanders, C (2015) “Medellin: A Post-Pablo Economy”, COCAINECONOMICS, The Wall Street Journal, http://www.wsj.com/ad/cocainenomics-post-pablo accessed on 30 June 2020

2. Dewar (Citation2004) “The Relevance of the Compact City Approach: The Management of Urban Growth in South African Cities in Compact Cities: Sustainable urban forms for developing countries, Jenks, M and Burgess, R (eds). Spon Press. London and New York

3. Pieterse (Citation2014). Transport system and densification must foster mutually inclusive plans, Cape Times 18 July 2014

4. South African policy for sustainable, integrated human settlements

5. CoGTA (Citation2014) “Integrated Urban Development Framework—Draft for Discussion”.

6. Provoost, M (Citation2015) “Cape Town—Densification as a Cure for a Segregated City”, International New Town Institute: Netherlands

7. Future Cape Town Summit—Summit Proceedings and Discussion Paper: Drawing the line on urban sprawl, May 2013

8. ibid

9. Future Cape Town Summit—Summit Proceedings and Discussion Paper: Drawing the line on urban sprawl, May 2013

11. Presentation to “Governing and Living with Urban Insecurity—Everyday practices and politics of governing and living with (in) security in the city of Cape Town”, 29–31 January 2018, Institute for Science Technology and Policy, ETH Zurich

12. City of Cape Town (2012) “Cape Town Spatial Development Framework—Statutory Report”

13. National Treasury (Citation2013) “Guidelines for the implementation of the Integrated City Development Grant in 2013/2014”

14. Gap housing refers to housing for individuals/households who earn too much in order to qualify for the State housing subsidy, yet do not earn enough in order to qualify for a mortgage from a private bank.

15. Francesco Orsini, A City Transformation: Urbanism & Architecture as a tool for Social Integration in Medellín, presented as part of the African Centre for Cities (ACC) Socio-Spatial Transformation seminar series, 22 September 2016

References

- Bauer, B. (2010). Violence prevention through urban upgrading: Experience from financial Cooperation, Germany. In German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Government Printer.

- Brand, P. (2010). Governing Inequality in the South through the Barcelona Model: social urbanism in Medellin, Colombia, Interrogating Urban Crisis: Governance, Contestation, Critique, De Montfort University, 9–21 September

- Brand, P. (2013, September 9-11). Governing Inequality in the South through the Barcelona Model: Social urbanism in Medellin, Colombia. Interrogating Urban Crisis: Governance, Contestation, Critique, De Montfort University.

- Brand, P., & Davila, J. D. (2011). Mobility Innovation at the Urban Margins. City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 15(6), 647–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2011.609007

- Brenner, N., & Theodore, N. (2002). Cities and the Geographies of Actually Existing Neoliberalism. Antipode, 34(3), 349–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00246

- Brown-Luthango, M. (2015). “Collective (in) efficacy, substance abuse and violence in Freedom Park, Cape Town. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31(1), pg.123–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9448-3

- Brown-Luthango, M. (2019). Sticking to themselves: Neighbourliness and safety in two self-help projects in Cape Town, South Africa. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, Issue, 99(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2019.0010

- Castro, L., & Echeverri, A. (2011). Bogotá and Medellín: Architecture and politics. Architectural Design, 2011 (pp. 96-103). https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1246

- City of Cape Town. (2013). City of Cape Town – Social Development Strategy. Cape Town: City of Cape Town.

- City of Cape Town. (2014). Voortrekker road corridor integration zone: Strategy and investment plan – status quo analysis report. Cape Town: City of Cape Town.

- City of Cape Town. (2017a). Built environment performance plan (BEPP) 2017/2018 – As approved by council. Cape Town: City of Cape Town.

- City of Cape Town. (2018). Municipal spatial development framework – council approved. Cape Town: City of Cape Town.

- CoGTA. (2014). Integrated urban development framework – draft for discussion. Department for Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Republic of South Africa.

- Cunningham, L. (2012, September/October). Transit-oriented development – A viable solution to revitalise inner cities. Right of Way.

- Da Schio, N., & Brekke, K. (2013). The relative carbon footprint of cities. Working Paper du Programme Villes et Territoires, SciencesPO, Observatory of European Institutions.

- Dewar, D. (2004). The relevance of the compact city approach: The management of urban growth in South African cities in compact cities: Sustainable urban forms for developing countries, Jenks, M and Burgess, R (eds). London and New York.

- Duncan, T. E., Duncan, S. C., & Okut, H. (2003). A multilevel contextual model of neighbourhood collective efficacy. American Journal of Community Psychology, 32(3–4), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AJCP.0000004745.90888.af

- Edigheji, O. (2004). Globalisation and the paradox of participatory governance in Southern Africa: The case of the new South Africa. African Journal of International Affairs, 7(1 & 2), 1–20. DOI: 10.4314/ajia.v7i1-2.57212

- Franz, T. (2016). Urban governance and economic development in Medellin: An urban miracle?. Latin American Perspectives, 44(213), 52–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X16668313

- Fukuyama, F., & Colby, S. (2011). Half a Miracle. Foreign Policy, Washington. Retrieved 7 September 2015, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/04/25/half-a-miracle/

- Gaventa, J. (2002). Exploring Citizenship, Participation and Accountability. Retrieved 30 June 2020, from www.opendocs.ids.ac.uk

- Goga, K., Salcedo-Albaran, E., & Goredama, C. (2014). A Network of Violence: Mapping a criminal gang network in Cape Town. ISS Paper 271, Institute for Security Studies. Cape Town.

- Goredama, C., & Goga, K. (2014). Crime Networks and Governance in Cape Town – The quest for enlightened responses. ISS Paper 262, Institute for Security Studies. Cape Town.

- Guthrie, A., & Fan, Y. (2016). Developers Perspective on Transit-oriented Development. Transport Policy, 51, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.04.002

- Hernandez-Garcia, J. (2013). Slum tourism, city branding and social urbanism: The case of Medellin, Colombia. Journal of Place Management and Development, 6(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538331311306122

- Hitge, G., & Vanderschuren, M. (2015). “Comparison of travel time between private car and public transport in Cape Town”, Technical Paper. Journal of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering, 57(3), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-8775/2015/V57N3A5

- Holmes, J., & van Hemert, J. (2008). Transit-oriented Development. Research Monologue Series: Urban Form, Transportation. The Rocky Mountain Land Use Institute.

- IDRC. (2002). Privatizing Cape Town: Service delivery and policy reforms since 1996. Occasional Paper No. 7, Municipal Services Project. Cape Town.

- Imparato, I., & Ruster, J. (2003). Slum Upgrading and Participation: Lessons from Latin America. The International Bank of Reconstruction and Development/World Bank.

- Jensen, S. (2005). The South African Transition: From development to security? Development and Change, 36(3), 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00423.x

- Jensen, S. (2010). The security and development nexus in Cape Town: War on gangs, counterinsurgency and citizenship. Security and Dialogue, 41(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010609357038

- Jessop, B. (2002). Liberalism, Neo-Liberalism and Urban Governance – A state-theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34(3), 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00250

- Kinnes, I. (2000). From urban street gangs to criminal empires: The changing face of gangs in the Western Cape. Monograph, 48, 1-41. European Union. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/from-urban-street-gangs-to-criminal-empires-the-changing-face-of-gangs-in-the-western-cape/

- Lambrechts, D. (2012). The impact of organised crime on state social control: Organised criminal groups and local governance on the cape flats, South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 38(4), 787–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2012.749060

- Leal, P. A. (2007). Participation: The ascendancy of a buzzword in the neo-liberal era. Development in Practice, 17(4–5), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469518

- McDonald, A., & Smith, L. (2004). Privatising Cape Town: From Apartheid to Neoliberalism in the Mother City. Urban Studies, 41(8), 1461–1484. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000226957

- McDonald, D. A. (2008). Introduction - world city syndrome: Neoliberalism and inequality in Cape Town. Routledge Press.

- Miraftab, F. (2004). Invited and invented spaces of participation: Neoliberal citizenship and feminist expanded notion of politics. Wagadu, 1, 1–7, Spring 2004. http://sites.cortland.edu/wagadu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2014/02/miraftab.pdf

- Miraftub, F. (2004). Making Neo-liberal Governance: The disempowering work of empowerment. International Planning Studies, 9(4), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563470500050130

- Moncada, E. (2016). Urban violence, political economy and territorial control: Insights from Medellin. Latin American Research Review, 51(4), 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2016.0057

- Monno, V., & Khakee, A. (2012). Tokenism or political activism – some reflections on participatory planning. International Planning Studies, 17(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2011.638181

- Moser, C. O. N. (1989). Community Participation in urban projects in the third world. Pergamon Press.

- National Treasury. (2013). Guidelines for the implementation of the Integrated City Development Grant in 2013/2014. National Treasury. Republic of South Africa.

- Orsini, F. (2016). A City Transformation: Urbanism & Architecture as a tool for Social Integration in Medellín, presented as part of the African Centre for Cities (ACC) Socio-Spatial Transformation seminar series, 22 September 2016, University of Cape Town. Cape Town, South Africa.

- Parnell, S., & Robinson, J. (2012). (Re)Theorizing cities from the global south: Looking beyond neoliberalism. Urban Geography, 33(4), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.4.593

- Patino, F. (2011). An integrated upgrading initiative by municipal authorities: A case study of Medellin. In UN Habitat Ed., Building urban safety through urban upgrading (pp. 7–20).

- Pieterse, E. (2014). Transport system and densification must foster mutually inclusive plans. Cape Times, 18(July), 2014.

- Pinnock, D. (1984). Breaking the Web: Economic Consequences of the destruction of extended families by Group Areas relocations in Cape Town. Carnegie Conference Paper, no. 258, 2nd Carnegie investigation into poverty and development in Southern Africa.

- Pinnock, D. (1997). Gangs, Rituals and Rites of Passage – Preface. African Sun Press. Cape Town: African Sun Press.

- Provoost, M. (2015). Cape Town – Densification as a Cure for a Segregated City, International New Town Institute: Netherlands.

- SACN. (2014). How to build transit-oriented cities: Exploring possibilities. South African Cities Network.

- SACN. (2017). The state of urban safety in South Africa Report 2017. A report of the Urban Safety Reference Group. Johannesburg: South African Cities Network.

- Samara, T. R. (2010). Policing Development: Urban renewal as neoliberal security strategy. Urban Studies, 47(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009349772

- Sampson, R. J. (2003). The neighbourhood context of well-being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46(3), S53–S64. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2003.0059

- Scruggs, G. (2014). Latin America’s New Superstar: How gritty, crime-ridden Medellin became a model for 21st century urbanism. The Next City. Ford Foundation. Retrieved 3 June 2020, from https://nextcity.org/features/view/medellins-eternal-spring-social-urbanism-transforms-latin-america

- Sites, W. (2007). Contesting the Neoliberal City? Theories of Neoliberalism and Urban Strategies of Contention. In Leitner, H., Peck, J., and Sheppard, E. S. (Eds), Contesting Neoliberalism - Urban Frontiers (Chapter 6). The Guidford Press. New York

- Sotomayor, L. (2015). Equitable Planning through Territories of Exception: The contours of Medellin’s urban development projects. IDPR, 37(4), 2015. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2015.23,373-397

- Turok, I. (2014). Medellin’s ‘Social Urbanism’ a Model for City Transformation. viewed 7 September 2015, from. http://mg.co.za/article/2014-05-15-citys-social-urbanism-offers-a-model

- Un Habitat. (2007). Reducing Urban Crime and Violence: Policy Directions – Enhancing Urban Safety and Security. Global Report on Human Settlements 2007, Abridged Edition, Volume 1. United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Earthscan.

- UN-Habitat. (2014). Practical guide to designing, planning and implementing citywide slum upgrading programs. United Nations Human Settlements Programme.

- Watson, V. (2014). Co-production and Collaboration in Planning – The difference. Planning Theory and Practice, 15(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2013.866266

- Wilson, D. (2004). Toward a Contingent Urban Neoliberalism”. Urban Geography, 25(8), 771–783. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.25.8.771