Abstract

Changes in socio-economic dynamics in an increasingly globalized world have triggered a significant increase in migration, especially for individuals from Africa. Voluntary migration comes with numerous costs, both hidden and unhidden. These costs, without doubt, do vary from one individual to another. Taking an evidence-based approach with data collected from the United States’ Department of State, this paper uncovers the expenses shouldered by Africans who seek Non-Immigrant Visas to the United States of America (US or USA). With over 80 categories of Non-Immigrant Visas (NIVs), the paper is narrowed to the most commonly sought NIV: the B1/B2 (business and tourism). This paper reflects on not only the increasing numbers of applications made over the years, and the financial implications these applications have on both the applicants and the national economies wherefrom they are made. Furthermore, it reviews the policies relating to US nationals who seek visas to visit African countries for business or tourism. As observed in the analysis of the evidence (official data), this paper argues that the payment of lower amounts thereof is indicative of a bias and lack of reciprocity in this regard, making migration to the Western world a drainage pipe through which African financial resources are collected.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The voluntary movement of people comes with a financial implication: individuals seeking to move are required to incur these costs. It is logical to expect fees to be levied on individuals who seek, amongst other things, visas. At least, from an administrative side, these fees cater for the processing of their applications. It is also logical to think that there should be reciprocity in the fees imposed: in other words, amounts paid by nationals of a country should be similar to what nationals of that country pay when they seek visas for the other country. Unfortunately, this is not the reality: as observed from the data, the fees that Africans pay when they apply for a B1/B2 visa to the United States are much higher than what Americans pay when they seek a visa to African countries for business or tourism. In my view, this is indicative of a policy bias which needs a more urgent attention.

1. Introduction

In propounding and corroborating the arguments herein, the points of departure are founded on two incontrovertible premises: first, that migration is as old as the origin of mankind itself as traces thereof can be made for as long as mankind has been in existence (Afshar, Citation2007; Bellwood et al., Citation2011; Bhui et al., Citation2003; Huber & Blackburn, Citation2012; IOVIT̨Ă & Schurr, Citation2004; Ness, Citation2014; Reed & Tishkoff, Citation2006; Sirkeci, Citation2006; Waterston, Citation2013). Secondly, migration is a constant and recurrent feature of humanity as every human being, at some point in time or place, would probably migrate, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, temporarily or permanently, for one reason or the other (Azeez & Begum, Citation2009; David, Citation1969; Gieling et al., Citation2011; Hansen, Citation2019; Oliver-Smith & Hansen, Citation2019; Richmond, Citation1993; Verkuyten et al., Citation2018). Despite this centuries-old practice, its dynamics have changed, triggering different responses from various parts of the world. So too are the factors that influence migration: political instability (Agadjanian & Gorina, Citation2019; Bezuidenhout et al., Citation2009; Karemera et al., Citation2000; Widgren, Citation1990); wars (Afshar, Citation2007; Bhui et al., Citation2003; Sirkeci, Citation2006; Waterston, Citation2013); socio-economic conditions (Azeez & Begum, Citation2009; Icduygu et al., Citation2001; McNabb, Citation1979; Sirkeci, Citation2006; Williams & Jobes, Citation1990); persecutory attitudes and policies towards minorities were some of the main reasons why people migrate (Behera, Citation2006; Betts, Citation2010; Bhugra & Becker, Citation2005; Boustan, Citation2007; De Costa, Citation2002; Jordan, Citation2009; Moore & Shellman, Citation2004; Sircar, Citation2006). Today, with the impact of globalisation, fascinated and facilitated by rapid advancements in technology, coupled with the dynamics of labour mobility and changes in income levels, the global responses have now acknowledged the world as a village, with the human race more closely knit by an invisible tread that runs across every corner of the world (Boniface & Fowler, Citation2002; Falk, Citation1998).

Migration, however, has its own financial implications which, often remain neglected or under-explored, especially in the context of voluntary migration (Erdal & Oeppen, Citation2018; Ottonelli & Torresi, Citation2013; Yamamoto & MacAndrews, Citation1975), the costs involved therein may be enormous. These costs vary from individual to individual, and often depend on a few factors, some of which are the number of individuals (whether an individual alone or is accompanied by his or her family); his or her nationality; the purpose of the trip; pre-visa formalities (such as possession of a valid passport and other travel documents, medical examinations, police clearance certificates); accommodation, ground and air transportation prior to the application for visa; visa fees; travel insurance; air transportation in cases where the visa has been obtained; and accommodation at the place of destination. Central to the pursuit of voluntary migration is the possession of a valid visa for the destination country.

Broadly speaking, a visa is a permission or authority granted to an individual to travel to a particular destination (receiving or destination country), for a specific purpose (visit, study, business, tourism, medical treatment, family reunion, etc.). A visa is usually valid for a specified amount of time (the validity of a visa is usually annotated to it at the time of its issuance) with an annotation of the number of times (single or multiple). Over time, visas have changed in form: from an inked stamp affixed to a passport to stickers with security features to electronic visas applied for prior to departure. Today, most countries are increasingly making use of electronic visas: an online application for a visa that is assessed and approved or refused electronically. Without a visa, a person cannot embark on international migration. These aspects, however, vary from nationality to nationality. Most countries have bilateral and multilateral arrangements with other countries to allow the free movements of their nationals without requiring the possession of a visa prior to embarking on such journey. For example, holders of United States passports can travel to South Africa without obtaining a visa prior to departing for South Africa as they are issued a visa for up to ninety days at the port of entry. These arrangements are common in the Global North (Western Europe even prior to the Schengen visa arrangement) and North America (the USA and Canada). On the African continent, sub-regional blocs like the South African Development Community (hereafter SADC); the Economic Community of West African States (hereafter ECOWAS); the Communauté Économique et Monétaire de l’Afrique Centrale (hereafter CEMAC) and the East African Community (hereafter EAC) do have similar arrangements. Migration, however, is not limited to only countries with which others have entered into agreements for the free movements of their people. People travel to different destinations, for various reasons.

For people who are not nationals of the Western world, global travel is a luxury (Tanelorn & Anderson, Citation2019). Even though addressed from the perspective and experience of non-Western countries, a broader application would unfold that this holds true especially when the people come from poor or developing countries. In most capital cities in these poor and developing countries, it is difficult to ignore the long queues in front of diplomatic missions mounted by individuals who are seeking visas to travel to the West. Examples abound French, Italian, Dutch, Belgian and German embassies are a few that come to mind. In addition to these are the embassies of the United States of America (US or USA) whose visa outcomes are not only uncertain but very unpredictable: unfortunately, these add to the prestige when one succeeds in obtaining a visa to the US. Put simply, seeking a visa to the US can be costly, and in the case of Non-Immigrant Visas (hereafter NIVs), the anxiety that it arouses given the fact that one can hardly predict if the application will be successful or unsuccessful.

Gauging these numbers of peoples seeking visas to the US, one may be tempted to wonder what the cumulative outcomes are on an annual basis: the total number of applications received, how many are successful and how many are unsuccessful. The United States’ Department of State (hereafter DoS) provides a wealth of information on these aspects, making the task of finding answers much easy. The figures on the total number of visa applications as well as the number of successful applications, on a first look, might be impressive and encouraging. Yet, when the financial implications are analysed, it becomes worrying and vexing.

Lawful migration as used in the US system requires, at least, a visa. However, visas are placed under two main categories: Immigrant Visas (hereafter IVs) and Non-Immigrant Visas. The former is issued to applicants who, undoubtedly, are deemed to migrate, or relocate to the US where they have to settle and find work. The process is usually commenced with the filing of a petition, which, most often, is relative-based (spouse; descendant or ascendant of the petitioner). The latter, NIV, is issued to individuals who intend to travel to the US for a temporary stay (Tanelorn & Anderson, Citation2019). Examples of NIVs include academic student; exchange student; business visit; tourist visit; medical treatment; etc. There are over 80 types of NIVs (Tanelorn & Anderson, Citation2019). For most of these sub-categories, the numeral affixed to the end of the letter indicates whether the individual is the primary holder or a dependent. For example, F1 and F2: F1 is the academic student who is pursuing an academic program at an accredited institution while F2 is the dependent (spouse or children) of the academic student. The same applies to J1 and J2 (academic exchange student and the dependents). This, however, does not apply to the B1/B2 categories: B1 traditionally for business visits and B2 for tourist visits.

In the past few decades, Africa has emerged as a continent wherefrom a considerable number of applications for the B1/B2 visas are made. As mentioned earlier, many reasons account for this observable trend. For the years 2013 till 2019, the data curled from the DoS and showed below indicate the following: total number of applications for the B1/B2 visas from across the world; as well as how many from Africa. The data also sub-categorises the number of applications that were successful and those that were unsuccessful, with Africa’s portion therein. The African numbers are also expressed in percentages of the total numbers (worldwide):

Table

It is therefore evident that Africa is a major source of applications for the B1/B2 NIVs. In 2013, approximately 6.5% of the global applications for B1/B2 NIVs came from Africa. This percentile rose slightly to about 6.9% the following year (2014), and then suffered a slight drop to 6.25% in 2015. It experienced a dramatic rise in 2016, with about 7.6% and grew to 8.1% in 2017, 8.4% in 2018 and 9.3% in 2019. These statistics corroborate the view that traveling to the USA for business and pleasure is a contemporary development influenced, amongst other things, by socio-economic conditions such as income flow, change in income levels, and prestige. If seen from an American perspective, this increasing trend is remarkable given the fact that it shows, at least, that the US is still an attractive destination for many Africans. Viewed from an economic perspective, one may consider and reflect on the financial implications of these applications, especially when weighed in comparison to what US nationals would pay for visas to travel to an African country for business or tourism.

There is an avalanche of relevant and respectful literature penned by a wide range of social sciences scholars and policy makers on the impact of migration: from the perspectives of both the sending and receiving countries (Ajayi et al., Citation2009; Antman, Citation2013; Anyanwu & Erhijakpor, Citation2010; Artal-Tur et al., Citation2014; Azam & Gubert, Citation2006; Docquier et al., Citation2012; Dustmann et al., Citation2007; Ehrlich & Canavire-Bacarreza, Citation2006; Haque & Kim, Citation1995; Richard & Page, Citation2003). Some authors have evaluated the valuable contribution of migration to societies wherefrom these migrants come, and whereto they migrated (Ajayi et al., Citation2009; Antman, Citation2013; Anyanwu & Erhijakpor, Citation2010; Artal-Tur et al., Citation2014; Azam & Gubert, Citation2006; Docquier et al., Citation2012; Dustmann et al., Citation2007; Ehrlich & Canavire-Bacarreza, Citation2006; Haque & Kim, Citation1995; Richard & Page, Citation2003). With regards to the US NIVs, there is a wealth of literature thereon, especially with regards to student visas in the post-9/11 era (Borjas, Citation2002; Model, Citation2018; Tiger, Citation2007; Walfish, Citation2002). Others have sought to provide scientific analysis on NIVs statistics in the US, with a focus on denials (Tanelorn & Anderson, Citation2019). Yet, a remarkable paucity exists in the literature that collects and analyses the data on B1/B2 visas from a financial implication perspective. Without delving into the reasons behind these successful and unsuccessful applications, this paper looks at the financial implications of B1/B2 visa applications from Africa, and highlights the financial bias that exists as US nationals who seek to travel to African countries for business or tourism are required to pay a much lesser amount for visa applications.

2. Objectives

This research examines the trends and outcomes of applications for visas made by Africans to travel to non-African countries, with focus on the costs incurred by these applicants. While ignoring other costs incurred prior to and after a successful visa application, the costs expended on visa applications only. It makes use of the available data for the ten-year period to understand what expenses are incurred by Africans who seek NIVs to the US.

3. Research question(s)

The central question to be answered here is what has been the financial expense borne by Africans who apply for the B1/B2 NIVs? A few sub-questions need to be answered: first, whether African countries charge US nationals the same amount(s) paid by Africans when they seek visas to travel to African countries for business or tourism? Secondly, and related to the previous question is whether there is reciprocity or bias in this regard?

4. Methodology

In order to find answers to the foregoing questions, this research takes an evidence-based approach, exploring and analysing data on B1/B2 NIVs. In order to gauge the financial implications of visa applications, and ascertain what it costs Africans to seek this category of NIVs to the US, an evidence-based methodology is taken: data from the Department of State for a ten-year period (2010–2019) were collected. This span of time (10-year period) would provide data on the amounts of money spent on applications for visas. As mentioned earlier, there are about 80 types of NIVs. To put together data on every class of NIV will not only cluster this research with figures and tables, but also make it an unnecessarily ambitious exercise. From a preliminary survey of the data, it was observed that the class of NIV most Africans applied for was B1/B2 (business/tourism). For two reasons, the study was thus narrowed to this category of NIV which, like the others, are issued on the presumption that the applicant intends to spend only a sojourn in the USA and return to his or her country of residence. First, from a comparative perspective of other NIVs, the sub-category B1/B2 was most applied for, probably because of the breadth of activities covered therein: holiday visits; family visits; pleasure and tourism. For Africans who traveled as a result of prestige (social, economic or both), this class of NIV was most appropriate. Secondly, in order to have an actual figure of the financial expenses incurred by applicants from Africa, application data for this class (B1/B2) from all 54 African countries were collected and analysed. There was no random or pre-determined selection since the paper seeks to analyse what Africans are paying in order to travel for business and leisure in the USA. The totality of the evidence helps in ascertaining the financial expenses in this regard. Americans, however, must not be blamed for making their country a much desired destination. However, there should be parity and reciprocity when it comes to, at least, the cost of visa applications. In other words, the amount Africans pay when they apply for a US visa must also be the same amount US nationals pay when they apply for a visa to any African country. In order to establish whether there is parity or reciprocity in this regard, the fee US nationals must pay when they apply for a business or tourist visa to travel to a specific African country was investigated. The findings are very disturbing and chilling.

5. Analysis and findings

As observed from the data studied, and discussed below, migration, broadly speaking, may be a visible drainage pipe through which African financial resources are taken when one considers the huge amounts of money squandered on unsuccessful visa applications. Based on the foregoing, it is an urgent imperative for policy makers to bring parity on the imposition of visa application fees for US nationals who travel to Africa for business and tourism. Having examined the different data on B1/B2 NIVs issued to Africans for the period 2010 to 2019, a few findings were made. These relate to the issue of reciprocity/issuance fees charged by the US Embassies on African nationals and the variations in amounts charged by African countries for US nationals who travel to Africa for business or tourism.

5.1. Trends in applications for B1/B2 NIVs from Africa

Looking at the figures below, one will notice a gradual increase in the applications for B1/B2 NIVs since 2010. In the ten-year period, a total of 5583377 applications for the B1/B2 visas were made by Africans. Of this number, 3450627 were successful, while 2132750 were unsuccessful.

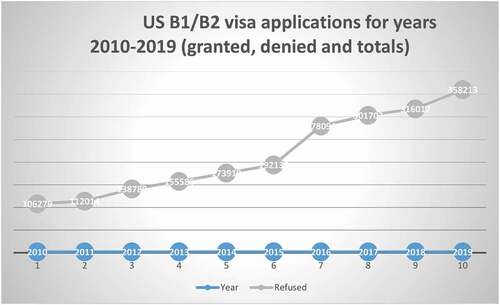

Graphical presentation of applications for B1/B2 NIVs (granted, refused and total for the years 2010–2019)

The numbers only began to drop from 2017 till 2019, but remained much higher when compared to the pre-2017 period. The number of successful applications rose steadily from 2010, and went on a decline from 2017. In 2019, the number of unsuccessful applications exceeded the number of successful applications.

5.2. The cost of refusals

Form the foregoing figures, it is quite easy to know how many visa applications were unsuccessful. Given the fact that every applicant for a B1/B2 NIV must pay the application fee of US$ 160, the number of granted and refused applications was multiplied by this amount. The table gives the actual figures of how much was spent on both granted and refused visa applications. For the ten-year period, 5,583,377 applications were made, generating US$ 893,340,333. Successful applications for the years 2010 to 2019 were 3,450,627, accounting for US$ 552,100,320 of the total amount. Unsuccessful applications were 2,132,750, costing US$ 341,240,013. Evidently, through visa applications, funds are drained from the African continent. There is no problem with the charge paid by every applicant for a visa. The problem, as discussed below, arises when African countries do not charge similar amounts to US nationals who travel to Africa for business or tourism.

Cost analysis of B1/B2 NIVs applications from Africa

5.3. The reciprocity/issuance fees

Based on information on the Department of State’s website, and the practices of the US Embassies across African countries, all applicants for a US non-immigrant visa must pay the application fee of US$160 (its equivalent payable in the local currency). This application fee is non-refundable (irrespective of the outcome); non-transferrable and is valid for a 365-day period. Secondly, once the application is made, and the outcome known, a reciprocity (or issuance) fee may be imposed. This is only for those whose applications have been successful. The reciprocity fee, as advised by the Department of State, is imposed on countries that have similar fees for US nationals. This depends on how a country charges US nationals for visas, making it vary from country to country. Data on all 54 countries in Africa indicate the following:

there are 45 African countries with no reciprocity fee and nine countries with a reciprocity/issuance fee;

of these African countries with a reciprocity fee, nationals of Comoros and Cameroon pay US$ 307 and US$ 240, respectively;

In the case of Cameroon, the reciprocity fee depends on the duration of the visa (US$ 240 for a twelve-month visa and US$ 60 for a six-month visa)—there are some African countries that have policies similar to that of Cameroon. Examples include Malawi (whose nationals pay US$ 140 for a twelve-month visa; US$ 60 for a six-month visa and nothing for a single entry visa with a three-month validity) and Mozambique (whose nationals get a single entry three-month visa free but pay US$ 20 for a three months’ multiple entry visa).

In addition to the foregoing variances, other important findings were made. An example is the duration of visas which vary from country to country: nationals of countries such as Chad; Democratic Republic of Congo; Eritrea; Burundi; Libya (with an issuance fee of US$ 10); Mozambique (with the possibility of determining single or multiple entries depending on whether issuance fee is paid); South Sudan (with two entries within the three-month period); Sudan; and Somalia do have very tough restrictions with regards to the validity of the B1/B2 visa and the number of times such a visa can be used. For some other countries, visas with multiple entries were issued with validity of up to 120 months (10 years). These countries include Botswana; Eswatini (Swaziland); Lesotho; Mauritius; Rwanda; Senegal; Seychelles; South Africa; and Tunisia. In between these brackets of duration are multiple entries visas with 6 months (Sao Tome and Principe); 12 months (Cameroon; Comoros; Côte d’Ivoire; Liberia; Mauritania; Niger; Tanzania and Zimbabwe); 15 months (Guinea-Bissau); 24 months (Algeria; Angola; Ethiopia; Nigeria and Uganda); 36 months (Benin; Guinea; Togo and Zambia) and 60 months (Burkina Faso; Egypt; Equatorial Guinea; Gabon; Ghana; Kenya; Mali; Namibia; and The Gambia) validity. Clearly, the same amount of money is paid for visa applications, yet, the validity of the visa, when issued, varies from country to country.

5.4. The bias in the visa application charges

A country, in furtherance of its legislative sovereignty, decides what conditions have to be fulfilled by individuals who intend to travel thereto. Applicants have the choice to decide on where to travel. Once they decide on where to travel, they are required to shoulder the financial expenses involved. One such expense is the cost of applying for a visa, often done without any knowledge of what the outcome will be. In fact, some authors hold the view that the adjudication and determination of the B1/B2 as well as other NIVs is “arbitrary” (Tanelorn & Anderson, Citation2019). The question to be asked is whether there is reciprocity in the amount charged by African countries to US nationals who seek visas to come to Africa.

Findings indicate that there is a glaring bias in this regard. Information obtained from diplomatic missions in Washington, DC, indicate the following: first, holders of US passports do not need to apply for visas prior to traveling as they obtain visas with a ninety-day validity at the port of entry. An example is South Africa. In mathematical terms, South Africans are required to pay US$ 160 to apply and obtain a US visa prior to traveling to the USA. On the other hand, holders of American passports depart from anywhere and arrive in South Africa where a visa, at no charge, is issued to them, valid for 90 days. If one looks at the number of South Africans who obtained this category of NIV, one may be tempted to argue that, without a corresponding levy on American nationals, the visa application cost is a huge drainage through which funds are taken from South Africa to the USA.

Secondly, there are some African countries that charge the same amount for visa applications from US passport holders. Algeria is an example. Also, some African countries impose an application fee for US passport holders which is much lower than what is charged for their nationals: for example, Angola (US$ 70); Eritrea (US$ 50 for a single entry tourist visa); Rwanda (US$ 70 for 30 days single entry and US$ 90 for a 30-day multiple entries); and Djibouti (US$ 30 for a short stay single entry only valid for 90 days maximum).

Lastly, there are countries that charge an application fee higher than the amount paid for the US tourist visa (B1/B2): Chad (single entry valid for 1 month is US$ 150, 3 months multiple entries is US$ 200 and 6 months multiple entries is US$ 250); Cameroon (tourism for up to 30 days is US$ 93; a long stay that is from 3 to 6 months is US$ 184; and for a long stay that ranges between 3 and 6 months is US$ 275); and the Central African Republic (US4 150 for visas valid for up to 3 months and US$ 200).

There is a recognition that every country determines what fee to charge, but common sense should dictate to policy makers in African countries the following: if parity or reciprocity is sought in international travel, then, the imposition of similar amounts for visas is plausible. One may struggle to find an eloquent argument to justify the disparities in the amounts paid for visa applications by US passport holders (who pay a significantly lesser amount when compared to what nationals of African countries pay).

If one were to consider the economics of development and the availability of resources for tourism and business, then, one would expect nationals from developing, lower income or poor countries to sustain a much lower financial expense when it comes to the cost of applying for a visa, and require nationals from developed and rich economies who have the resources to pay a much higher visa application fee. Unfortunately, the reality is the reverse: much more is taken from the poorer African countries, while very little, from a comparative perspective, is taken from the rich and developed countries like the United States.

6. Reflecting on other experiences: Schengen and the UK data on visa applications

The foregoing discussion, backed by evidence, has been on the financial expenses and wastes as a result of both applications for the B1/B2 visas, and the sizeable refusals thereto. Even though the discussion was narrowed to only the US, with focus on the B1/B2 visas, it may be important and necessary, as a point of conclusion, to consider the experience elsewhere. Is the US experience a unique one? Or could there be similar attitudes and experiences with different major destinations? The United Kingdom (UK) and the broader Western Europe which do now constitute the Schengen, are also major destinations for Africans. Without doubt, for short stays (such as business and tourism), the nationals of most of these countries travel to African countries without any pre-departure visa requirements, and obtain visas at the port of entry at no cost. Information from the European Commission on the 2015 Schengen area short-term visa applications ranked the following African countries as making the top 13 with the following figures and expenses incurred:

In 2015, these top 13 African countries made 600,427 applications for short-term visas to the Schengen area. A total of 492,906 were successful while 107,511 were unsuccessful. The costs of these applications amounted to €36,025,620. Of this amount, €6,450,581 was spent on unsuccessful applications. For the top 13 African countries, for short-term visas for a single year. Probably, the figures will change if one were to consider the entire Africa for that year, and worst if looked into for a ten-year period. A similar approach was taken to consider what the UK experience is. Looking at entry clearance visas for the UK for the year 2015, with focus on the top 16 African countries. However, the data encompasses visitors, work and study visas made from these countries for the year 2015. These visas (visitors/transit, work and study) do have different application fees (as indicated in the table hereunder):

From the figures above, in 2015, 355,863 applications for entry clearance visas to the UK were made by nationals of 16 African countries. This number comprises applications for visitors/transit, study and work visas in the UK. A total of 273,857 applications were successful, and 82,259 unsuccessful. In financial terms, the total number of applications generated GB£ 44,879,935. For unsuccessful applications, the amount was GB£ 13,984,030.

7. Conclusion

Without doubt, migration impacts both the sending and receiving communities and countries. However, from a policy standpoint, one must consider the need for equality and reciprocity in the charges imposed on Africans for visa applications while a corresponding equivalent amount is not paid by holders of certain passports. This is purely a policy issue which must be attended to by policy makers within the diplomatic circles. If Africa is considered the poor and developing continent, then, migration costs must not be excessively and unreasonably higher than what nationals of rich and developed countries pay when they visit Africa.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Avitus A Agbor

Professor Avitus A Agbor is a Research (Associate) Professor of Law at the Faculty of Law, North-West University. His research interests include international human rights; international criminal law and justice; international humanitarian law; governance; the rule of law; and the dynamics and politics of Africa’s underdevelopment. He has written extensively on aspects of international criminal law and justice; international human rights law; international crimes; and good governance.

References

- Afshar, H. (2007). Women, wars, citizenship, migration, and identity: Some illustrations from the Middle East. The Journal of Development Studies, 43(2), 237–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380601125057

- Agadjanian, V., & Gorina, E. (2019). Economic swings, political instability and migration in Kyrgyzstan. European Journal of Population, 35(2), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-018-9482-4

- Ajayi, M. A., Ijaiya, M. A., Ijaiya, G. T., Bello, R. A., Ijaiya, M. A., & Adeyemi, S. L. (2009). International remittances and well-being in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 1(3), 078–084. https://doi.org/10.5897/JEIF.9000069

- Antman, F. M. (2013). The impact of migration on family left behind. In A. F. Constant & K. F. Zimmermann(Eds.), International handbook on the economics of migration (pp. 293–308). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Anyanwu, J. C., & Erhijakpor, A. E. (2010). Do international remittances affect poverty in Africa? African Development Review, 22(1), 51–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2009.00228.x

- Artal-Tur, A., Peri, G., & Requena-Silvente, F. (2014). The socio-economic impact of migration flows. Springer.

- Azam, J., & Gubert, F. (2006). Migrants‘ remittances and the household in Africa: A review of evidence. Journal of African Economies, 15(Suppl. 2), 426–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejl030

- Azeez, A., & Begum, M. (2009). Gulf migration, remittances and economic impact. Journal of Social Sciences, 20(1), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2009.11892721

- Behera, N. C. (2006). Gender, conflict and migration (Vol. 3). Sage.

- Bellwood, P., Chambers, G., Ross, M., & Hung, H. (2011). Are ‘cultures’ inherited? Multidisciplinary perspectives on the origins and migrations of Austronesian-speaking peoples prior to 1000 BC. In B. W. Roberts & M. V. Linden (Eds.), Investigating Archaeological Cultures (pp. 321–354). Springer.

- Betts, A. (2010). Survival migration: A new protection framework. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 16(3), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01603006

- Bezuidenhout, M. M., Joubert, G., Hiemstra, L. A., & Struwig, M. C. (2009). Reasons for doctor migration from South Africa. South African Family Practice, 51(3), 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2009.10873850

- Bhugra, D., & Becker, M. A. (2005). Migration, cultural bereavement and cultural identity. World Psychiatry, 4(1), 18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1414713/

- Bhui, K., Abdi, A., Abdi, M., Pereira, S., Dualeh, M., Robertson, D., Sathyamoorthy, G., & Ismail, H. (2003). Traumatic events, migration characteristics and psychiatric symptoms among Somali refugees. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0596-5

- Boniface, P., & Fowler, P. (2002). Heritage and tourism in the global village. Routledge.

- Borjas, G. J. (2002). Rethinking Foreign Students A question of the national interest. National Review, 54(11), 38–40.

- Boustan, L. P. (2007). Were Jews political refugees or economic migrants? Assessing the persecution theory of Jewish emigration, 1881–1914. In T. J. Hatton, K. H. O'Rourke & A. M. Taylor (Eds.), The New Comparative Economic History: Essays in Honor of Jeffrey G. Williamson (pp. 267–290). The MIT Press.

- David, H. P. (1969). Involuntary international migration: Adaptation of refugees. International Migration, 7(3–4), 67–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.1969.tb01062.x

- De Costa, A. (2002). Assessing the cause and effect of persecution in Australian Refugee Law: Sarrazola, Khawar and the Migration Legislation Amendment Act (No. 6) 2001 (CTH). Fed. L. Rev., 30, 535. DOI: 10.22145/flr.30.3.4

- Docquier, F., Marchiori, L., & Shen, I. (2012). Brain drain in globalization: A general equilibrium analysis from the sending countries’ perspective. Economic Inquiry, 51(2), 1582–1602. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00492.x

- Dustmann, C., Frattini, T., & Glitz, A. (2007). The impact of migration: A review of the economic evidence. Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (Cream), Department of Economics, University College London, and EPolicy LTD, November, 1–113. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpb21/reports/WA_Final_Final.pdf

- Ehrlich, L., & Canavire-Bacarreza, G. J. (2006). The impact of migration on foreign trade: A developing country approach. Latin American Journal of Economic Development, (6), 125–146. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/1090/1/MPRA_paper_1090.pdf

- Erdal, M. B., & Oeppen, C. (2018). Forced to leave? The discursive and analytical significance of describing migration as forced and voluntary. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(6), 981–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384149

- Falk, D. K. (1998). Law in an emerging global village: A post-Westphalian perspective. Brill/Nijhoff.

- Gieling, M., Thijs, J., & Verkuyten, M. (2011). Voluntary and involuntary immigrants and adolescents’ endorsement of multiculturalism. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(2), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.003

- Hansen, A. (2019). Involuntary migration and resettlement: The problems and responses of dislocated people. Routledge.

- Haque, N. U., & Kim, S. (1995). “Human Capital Flight”: Impact of Migration on Income and Growth. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 42(3), 577–607. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867533

- Huber, T., & Blackburn, S. (2012). Origins and migrations in the extended eastern Himalayas. Brill.

- Icduygu, A., Sirkeci, I., & Muradoglu, G. (2001). Socio-economic development and international migration: A Turkish study. International Migration, 39(4), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00162

- IOVIT̨Ă, R. P., & Schurr, T. G. (2004). Reconstructing the origins and migrations of diasporic populations: The case of the European Gypsies. American Anthropologist, 106(2), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2004.106.2.267

- Jordan, S. R. (2009). Un/convention (al) refugees: Contextualizing the accounts of refugees facing homophobic or transphobic persecution. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, 26(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.32086

- Karemera, D., Oguledo, V. I., & Davis, B. (2000). A gravity model analysis of international migration to North America. Applied Economics, 32(13), 1745–1755. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368400421093

- McNabb, R. (1979). A socio-economic model of migration. Regional Studies, 13(3), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595237900185261

- Model, S. (2018). Why are Asian-Americans educationally hyper-selected? The case of Taiwan. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(11), 2104–2124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1341991

- Moore, W. H., & Shellman, S. M. (2004). Fear of persecution: Forced migration, 1952-1995. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 48(5), 723–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002704267767

- Ness, I. (2014). The global prehistory of human migration. John Wiley & Sons.

- Oliver-Smith, A., & Hansen, A. (2019). Introduction Involuntary migration and resettlement: Causes and contexts. In A. Hansen(Ed.), Involuntary migration and resettlement (pp. 1–9). Routledge.

- Ottonelli, V., & Torresi, T. (2013). When is migration voluntary? International Migration Review, 47(4), 783–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12048

- Reed, F. A., & Tishkoff, S. A. (2006). African human diversity, origins and migrations. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, 16(6), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.008

- Richard, A. H. J., & Page, J. (2003). International migration, remittances, and poverty in developing countries. The World Bank.

- Richmond, A. H. (1993). Reactive migration: Sociological perspectives on refugee movements. Journal of Refugee Studies, 6(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/6.1.7

- Sircar, O. (2006). Can the women flee? Gender-based persecution, forced migration and asylum law in South Asia. In Gender, Conflict and Migration (pp. 255–273). SAGE Publishing.

- Sirkeci, I. (2006). Ethnic conflict, wars and international migration of Turkmen: Evidence from Iraq. Migration Letters, 3(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v3i1.29

- Tanelorn, J., & Anderson, A. (2019). Worldwide approval (and denial): Analysing nonimmigrant visa statistics to the United States from 2000 to 2016. Mobilities, 14(2), 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1567986

- Tiger, J. (2007). Re-bending the paperclip: An examination of America’s policy regarding skilled workers and student visas. Geological Immigration LJ, 22(3), 507–528.

- Verkuyten, M., Mepham, K., & Kros, M. (2018). Public attitudes towards support for migrants: The importance of perceived voluntary and involuntary migration. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(5), 901–918. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1367021

- Walfish, D. (2002). Student visas and the illogic of the intent requirement. Geological Immigration LJ, 17(3), 473–504.

- Waterston, A. (2013). My Father’s Wars: Migration, memory, and the violence of a century. Routledge.

- Widgren, J. (1990). International migration and regional stability. International Affairs, 66(4), 749–766. https://doi.org/10.2307/2620358

- Williams, A. S., & Jobes, P. C. (1990). Economic and quality-of-life considerations in urban-rural migration. Journal of Rural Studies, 6(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(90)90005-S

- Yamamoto, K., & MacAndrews, C. (1975). Induced and voluntary migration in Malaysia: The Federal Land Development Authority role in migration since 1957. Asian Journal of Social Science, 3(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1163/080382475X00210