Abstract

Brunei Darussalam (hereafter Brunei) aspires to be one of the countries in the world with the highest Quality of Life by 2035. However, there is a dearth of studies on the meaning of Quality of Life and characteristics of a high Quality of Life in Brunei. This study examined the conceptualisation of Quality of Life by the Government of Brunei and descriptions of a high Quality of Life within the country. It also analysed the constructs that inform such a conceptualisation and such descriptions. Lastly, the study assessed the conceptualisation of Quality of Life in Brunei using the principles for conceptualising Quality of Life. It employed a mixed methods approach and drew data from government policy documents and interviews with 208 purposively selected households. The study found that the government construes Quality of Life, through the capability lens, as having a population that is well-educated, highly skilled and healthy, among other elements; lives harmoniously and peacefully; and engages effectively in economic and social activities. Descriptions of a high Quality of Life in Brunei, expressed through the basic needs and capability lenses, include “fulfilled basic needs”, “being financially secure”, ‘being well-educated”, “having a well-paying and permanent job”, “living comfortably” and “being healthy”. These descriptions are, by and large, similar in urban and rural areas. Moreover, the descriptions are similar to those held in other Southeast Asian countries. The conceptualisation of Quality of Life in Brunei is sound in that it satisfies Quality of Life conceptualisation principles.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Brunei is working towards becoming one of the countries in the world with the highest Quality of Life by 2035. However, there is a relatively little understanding of the meaning of Quality of Life” in the country. This study provides invaluable insights as to how the Government of Brunei conceptualises Quality of Life and what constitutes a high Quality of Life within the country. The insights are expected to ignite academic debates on Quality of Life issues in Brunei, which should not only bring clarity as to the use of the Quality of Life concept in the country’s social development sector but also advocate for the adoption of the concept at global level, given the sensitivity associated with the term “poverty” the world over.

1. Introduction

Improving the Quality of Life (QoL) in any society is at the heart of social development. However, there is no consensus amongst scholars on how to define QoL (Dijkers, Citation2007; Mandzuk & McMillan, Citation2005; Mishra, Citation2015). This could be due to the fact that the meaning of QoL is determined by social, economic, political, religious and environmental factors that are context-specific (Cummins, Citation2005). It is important, therefore, to understand the meaning(s) attached to QoL within a given context.

In Brunei’s social development sector, QoL as a concept is preferred over the term “poverty”. This may be attributable to the emphasis that the Government of Brunei places on enhancing the QoL within the country in its current long-term development plan (Brunei Vision 2035). Moreover, the term “poverty” is somewhat sensitive in Bruneian society as it could potentially erode a person’s self-confidence, esteem or sense of (self-) worth (Gweshengwe et al., Citation2020). Under the Brunei Vision 2035, Brunei aspires to be ranked amongst the top ten countries in the world with the highest QoL (Brunei Darussalam Long-term Development Plan, Citationn.d.; Department of Economic Planning and Development, Citation2012). However, the meaning of QoL and what would constitute a high QoL in Brunei are hardly subjected to scholarly examination. Moreover, constructs that underlie the conceptualisation of QoL in this country are not well-known. Lastly, there has not been any review of the conceptualisation of QoL in Brunei.

The present study therefore examines the conceptualisation of QoL by the Government of Brunei and descriptions of a high QoL held within the country. In the process, the study sheds light on the constructs through which QoL is conceptualised in Brunei and assesses the country’s conceptualisation of QoL. Thus, the study generates insights which enrich scholarly literature on QoL. The insights, moreover, are expected to ignite a scholarly discussion on Brunei’s preference for the QoL concept rather than the poverty concept in issues relating to social development. The discussion should help to bring clarity, within Brunei’s social development sector, about the conceptualisation of QoL and poverty, since there is some parallelism in the usage of the concepts. Furthermore, the discussion will advocate for the adoption, at global level, of the QoL concept in social development as the sensitivity of the term “poverty” is, according to Gweshengwe and Hassan (Citation2020), not only peculiar to Brunei but very much in evidence throughout the world.

2. Conceptualisation of Quality of Life

Although the debate about the conceptualisation of QoL is still evolving (Cummins, Citation2005), principles and approaches for QoL conceptualisation have been—and continued to be—advanced. This section reviews such principles and approaches since they are considered to be central to understanding and assessing the conceptualisation of QoL in Brunei, which is the primary objective of this study.

2.1. Principles for the conceptualisation of Quality of Life

Cummins (Citation2005) asserts that the conceptualisation of QoL is guided by four principles. Firstly, QoL is a construct that is multidimensional and influenced by personal and contextual factors. Human life has multiple facets and can, according to Hick (Citation2014), be blighted in various ways. It is, moreover, determined by age, gender and the environment one lives in. Accordingly, QoL should be conceptualised as a multidimensional phenomenon (Betti et al., Citation2016; Kreitler & Kreitler, Citation2006; Shin & Inoguchi, Citation2009), taking into account personal and contextual factors (Cummins, Citation2005; Ventegodt et al., Citation2003). Secondly, QoL is a concept with common elements across society but with variations in terms of the value placed on individual elements. Accordingly, there may be, within QoL conceptualisation, universal aspects of QoL in a society (Cummins, Citation2005) but with different levels of significance. Thirdly, the QoL construct has both objective and subjective components. The objective QoL component refers to how good a person’s life is perceived to be by the outside world, while the subjective QoL component refers to how good one feels one’s life is (Arif et al., Citation2019; Ventegodt et al., Citation2003). Both components should be included in the conceptualisation of QoL (Betti et al., Citation2016; Shye, Citation2010; Ventegodt et al., Citation2003). Fourthly, QoL is a concept that is improved by self-determination, resources, purpose in life and a sense of belonging. These aspects should be taken into account in the conceptualisation of QoL.

2.2. Approaches for the conceptualisation of Quality of Life

For the most part, the Social Sciences discipline makes use of three approaches in conceptualising QoL, namely utility, basic needs and capability (Alkire, Citation2008; Moonsa et al., Citation2006; Phillips, Citation2006; Stiglitz et al., Citation2010). It is essential to examine the different ways in which these approaches conceptualise QoL and critique them based on the four QoL conceptualisation principles discussed above.

The utility approach is a commonly used QoL construct, which interprets QoL in terms of utility (Phillips, Citation2006). Utility refers to the mental state reflected in a person’s level of satisfaction (Alkire, Citation2008; Robeyns & Van der Veen, Citation2007). Satisfaction, as Robeyns and Van der Veen (Citation2007) explain, refers to contentment with life domains, such as health, education and family relationships. It has “intrinsic value” (Alkire, Citation2008; Sen, Citation2008), which is defined by Sen (Citation1987) as the value of a phenomenon in its own right. In other words, satisfaction is valuable in and of itself (Tay et al., Citation2015), and for this reason, it provides invaluable insight on the impact of policy action (Sen, Citation2008). The focus on satisfaction may, however, give a misleading representation of the life of the “satisfied” poor, who are comfortable with their situations of deprivation (Alkire, Citation2008; Qizilbash, Citation2006; Sen, Citation2008). Income is usually used as an indicator or proxy of utility (Graham, Citation2008; Stewart, Citation1996). Utility is therefore attained when a person has an income that enables him/her to access essential goods and services (Phillips, Citation2006). A high-income level translates to a high utility level and this implies a high QoL (Phillips, Citation2006). Inoguchi and Fujii (Citation2013), for example, used the utility approach to study QoL in Asian societies: they focused on 16 domains, which include education, health, marriage and public safety.

This approach reasonably satisfies two of the four QoL conceptualisation principles. It fulfils the principle that elements of QoL are the same across a community but with different levels of significance. The approach defines QoL in terms of satisfaction (utility), which is usually universal to people in a society, and the focus is on “the level of satisfaction”, which varies according to an element of QoL under consideration. Central to the approach is the achievement of life satisfaction, which can be enhanced by having access to resources (a high income), a clear purpose in life and a sense of belonging. However, the utility approach disregards the principle that QoL is a multidimensional construct. The approach, in fact, is reductionist in nature. QoL is complex and has dimensions, such as long and healthy life, nutritional level and public safety, which cannot be reduced to a single metric or proxy (income) without distortions (Alkire, Citation2008; Pukeliene & Starkauskiene, Citation2011; Rogerson et al., Citation1989). Moreover, this approach is anchored on subjective utility (life satisfaction) (Phillips, Citation2006; Robeyns & Van der Veen, Citation2007) and does not incorporate the objective component of QoL.

The basic needs approach meanwhile, construes QoL as having a decent life achieved by accessing basic goods and services, such as food, water, shelter, medical services and education (McKenna & Doward, Citation2004; Peruniak, Citation2010; Stewart, Citation1996). This approach is anchored on the minimalist philosophy and focuses only on health, nutrition and literacy (Mishra, Citation2015; Phillips, Citation2006; Stewart, Citation1996). An individual’s level of QoL is dependent on his or her ability to meet his/her basic needs: one has a high level of QoL if his or her basic needs are sufficiently met (McKenna & Doward, Citation2004). This approach has the potential to reveal the actual QoL in the case of the “satisfied” poor, who are well adapted to their circumstances of deprivation.

This approach does little to satisfy the principles for conceptualising QoL. Its underlying philosophy that the definition of what constitutes basic human needs is universally and uncontroversially accepted (Phillips, Citation2006) fulfils part of the principle that the elements of life quality are the same for all people within a society, but it overlooks variations in the level of significance of each element (basic needs). In order to improve QoL, the approach places emphasis on access to resources. In fact, the approach “says absolutely nothing about quality of life above [the] ‘decency’ threshold” (Phillips, Citation2006, p. 7), and this threshold, as stressed earlier, comprises three basic needs: health, nutrition and literacy. Moreover, the basic needs are determined by experts or “outsiders” (Wong, Citation2012). The approach therefore only factors in the objective component of QoL. The last point to be made is that the basic needs approach hardly takes into account the multidimensional nature of the QoL concept. As Graham and Behrman (Citation2009) opine, QoL goes beyond basic needs to capabilities, which are measured by the Human Development Index (HDI).

The capability approach, developed by Amartya Sen as an alternative to the income and basic needs approaches (Alkire, Citation2008), construes QoL based on capabilities that a person has to achieve functionings (A.K. Sen, Citation1989; Qizilbash, Citation2006; Rokicka, Citation2014; Sen, Citation1999). Capabilities refer to abilities, freedoms or real opportunities to lead a life that one values; while functionings denote the “beings” and “doings” (what one views as important to be or to do), such as being safe, well-nourished, literate and active in communal life or able to appear in public without a sense of shame (Alkire, Citation2008; Hick, Citation2012, Citation2014; Nussbaum, Citation2003, Citation2011; Sen, Citation1985, Citation2008). Thus, the capability approach defines QoL as having a set of basic capabilities that makes one achieve functionings in accordance with what one values (Alkire, Citation2008; Robeyns & Van der Veen, Citation2007; Rokicka, Citation2014; Sen, Citation1985). As Sen argues, QoL is based on “being” and “doing” rather than possessing goods, resources or income (Alkire, Citation2008; Rokicka, Citation2014; Sen, Citation1985, Citation1987). The “beings” and “doings” have intrinsic significance (Alkire, Citation2008; Robeyns & Van der Veen, Citation2007; Sen, Citation1999). Hence, the approach is suitable for understanding the QoL of the “satisfied” poor, who are accustomed to their circumstances of deprivation.

The capability approach is more appealing in conceptualising QoL in that it satisfies all the QoL conceptualisation principles. It is all-inclusive (Hick, Citation2012) and anchored on pluralist and non-reductionist philosophies (Nussbaum, Citation2011; Robeyns, Citation2005; Sen, Citation1999). This approach therefore acknowledges the multidimensionality of the QoL concept. Moreover, it does not have a predetermined set of basic capabilities; people have to generate the set in keeping with their contexts or an expert can develop the list based on his or her expertise and knowledge of the context (Nussbaum, Citation2011; Sen, Citation1999). Accordingly, the approach recognises that QoL is influenced by personal and contextual factors, and allows for the generation of a universal set of basic capabilities but with variations in the value accorded to these capabilities. It also allows for the inclusion, in QoL conceptualisation, of both objective and subjective components of QoL. Lastly, the approach’s focus on capabilities and functionings (doings and beings) implies that it accepts that access to resources, self-determination, purpose in life and sense of belonging are also central to improving QoL.

3. Study area and methods

Brunei is an oil-rich Muslim country situated on the northwest of the Borneo Island, Southeast Asia. In 2019, the country had a total population of 459 500: 46.8 % female and 53.2% male (Department of Economic Planning and Statistics, Citation2019). The country is making significant strides in providing an enhanced QoL to its people through different government programmes in education, health and other dimensions of social welfare (Gweshengwe & Hassan, Citation2019). Bruneians are well-educated, healthy, with a high life expectancy (74.64 and 79.41 years for males and females, respectively) and are satisfied with their housing, standard of living, public safety, the social welfare system, social networks, and the conditions of their natural environment (Gweshengwe, Citation2020; Inoguchi & Fujii, Citation2013). In 2018, Brunei had a high HDI of 0.845 (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2019).

The country has a small but prosperous economy, which is a mixture of “foreign and domestic entrepreneurship, government regulations, welfare measures and village tradition” (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2008, p. 102). Brunei’s economy is anchored on the oil and gas industry, which accounts for nearly 70% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), more than 90% of exports, and almost 90% of the government revenue (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2008; Fifth National Development Plan, Citationn.d.; Gweshengwe, Citation2020). The country had a GDP of USD 13.5 billion in 2019 (World Bank, Citation2020).

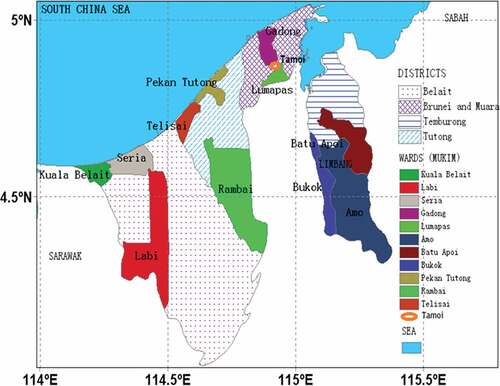

The study covered 12 Wards (Figure ), which were purposively selected based on the researchers’ knowledge about Brunei.

The study adopted a mixed methods approach: more qualitative and less quantitative. For the qualitative component, the study used an exploratory method. According to Gratton and Jones (Citation2010), the exploratory method seeks to generate insights for a phenomenon with little or no prior knowledge available. Moreover, it is flexible as it allows the features of a phenomenon under study to be considered as they emerge (McNabb, Citation2010). Hence, the exploratory method was appropriate for the study, which required a flexible method due to the lack of prior knowledge about QoL in Brunei. The quantitative component took the form of a frequency distribution graph and table, which were used at the analysis stage to summarise and describe data.

The study drew data from government key policy documents, namely the Brunei Darussalam Long-term Development Plan (Wawasan 2035) and Tenth National Development Plan (2012–2017), which outline Government of Brunei’s aspirations and approaches intended to enhancing QoL in the country. Data drawn from these policy documents were used to examine the government’s conceptualisation of QoL. The study also drew data from 208 households (130 urban households and 78 rural households). The households were purposively selected based on the researchers’ in-depth knowledge of Brunei and research experience on poverty and QoL issues in the country. Access to the households was facilitated by District Officials as well as Wards and Village leaders. The study used data saturation technique to determine the sample size of 208 households. Based on Bowen’s (Citation2008) description of the data saturation technique, the study recruited households until nothing new was being generated from the exercise. From the selected households, the study collected, using semi-structured interviews, data on the descriptions of a high QoL in Brunei. This was influenced by the argument by Yuan et al. (Citation1999, p. 3) that: “quality, like beauty, basically lies in the eyes of the beholder.” In other words, what constitutes a high QoL is better known and articulated by people who live the life or circumstances.

4. Findings

4.1. Conceptualisation of QoL by the Government of Brunei

In order to understand how the government conceptualises QoL, the study examined the “ends” (policy objectives), “means” (policy actions) and “measurement method” of the QoL component of the long-term development plan (Wawasan Brunei 2035) and 10th National Development Plan. Table presents the “ends” and “means” of the QoL component. The government uses the HDI to measure its progress in achieving a high QoL in the country (Brunei Darussalam Long-term Development Plan, n.d). This implies that Brunei aspires to be in the top ten countries in the world with the highest HDI in the “very high human development” category of the United Nations Development Programme human development ranking. In 2019, the country was ranked 43 in the very high human development category (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2019).

Table 1. “Ends” and “Means” of the QoL component

As the results presented above reflect, the Government of Brunei conceptualises QoL as having a population that is well-educated, highly skilled, healthy, responsible, charitable and safe from life-threatening phenomena; lives harmoniously and peacefully; and engages effectively in economic and social activities. The conceptualisation is anchored on the capability approach. The “ends” (Table ) are functionings: the valuable states of life (beings) and activities (doings) that government aspires its citizens to attain and realise. The “means” are the “real opportunities” or “freedoms” that the government is focusing on or investing in for Bruneians to achieve the functionings (“beings” and “doings”). The use of HDI to measure the impact of QoL policy actions reinforces the observation that the government conceptualises QoL using the capability lens. The HDI measures a country’s progress in terms of human development (Stanton, Citation2007; United Nations Development Programme, Citation2019). The human development concept, anchored on the capability approach, entails expanding people’s choices (freedoms) to achieve functionings (Alkire, Citation2005; Farrar, Citation2012; Fifth National Development Plan, Citationn.d.; Pramono, Citation2016). The human development paradigm also influences Brunei’s poverty reduction policies (Gweshengwe & Hassan, Citation2019). The government therefore makes use of a sound QoL conceptualisation approach, which does not only construe QoL as a multidimensional phenomenon but also effectively captures the QoL of the “satisfied” poor, who are accustomed to their situations of deprivation.

4.2. Descriptions of high Quality of Life in Brunei

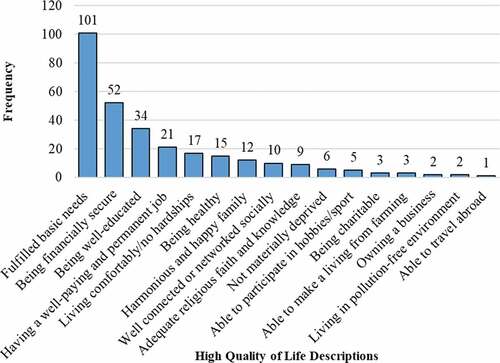

The study asked household respondents what they consider to be a “high QoL” in Brunei and they gave varied descriptions of their perceptions of this (Figure ). The most-reported ones were “fulfilled basic needs”, “being financially secure”, “being well-educated”, “having a well-paying and permanent job”, “living comfortably/no hardships”, “being healthy” and “harmonious and happy family, respectively. These findings reinforce the observation by Inoguchi and Fujii (Citation2013) that health, home, diet (food), family and job are the principal lifestyle choices in Brunei. Based on the findings in Figure , then, households construe a ‘high QoL through the basic needs and capability lenses.

The descriptions of a high QoL in Figure are explained hereafter.

“Fulfilled basic needs”: the households explained a high QoL as having satisfied basic needs, which were listed as food, basic amenities (water, electricity and communication), owning a car, housing and clothing. Unlike other countries, where private transportation such as a car is seen as a luxury, households regarded owning a car in Brunei as a necessity owing to the relatively unreliable public transport. A household respondent in Ward Gadong, for example, said: “ … mempunyai kereta adalah satu kemestian di Brunei” (… having a car is a must in Brunei). This is confirmed in the poverty study by Gweshengwe et al. (Citation2020), in which it was found that the Bruneian community considers people without their own cars to be poor. In analysing a high QoL in terms of “fulfilled basic needs”, this study treats education and health independently, as they were mainly expressed by households using the capability lens.

“Being financially secure” was described by the households as having sufficient income for basic needs and wants, and not depending on welfare assistance. The households also described “being financially secure” as having a “side income” (earning extra income) and savings for unforeseen events and children’s future needs and earning a “legitimate” income (honest income permissible by God). However, households did not specify the amount needed for one to be considered to be financially secure.

“Being well-educated” was explained by households as having the highest academic qualifications (graduate and postgraduate degrees) that enable one to secure or compete for a permanent and well-paying job. By way of example, the head of a household in Ward Labi, who is a secondary school (Year 11 or equivalent to Form 5) graduate, stressed: “there is a growing demand for highly educated personnel: even for lowly ranked jobs, those with Form 5 qualifications are now competing with degree holders.” Another example is of a household in Ward Pekan Tutong, which said: “tahap pendidikan yang rendah menjadikan seorang individu lebih sukar mencari pekerjaan dan pendapatan yang tinggi” (low education makes it harder for a person to get employment with a high salary.” Moreover, “being well-educated” makes an individual highly regarded or esteemed in society.

“Having a well-paying and permanent job”: according to the households, ensures an adequate and stable income for a household. Such a job, as the households explained further, guarantees one a high QoL in that it ensures financial security, which, according to Gweshengwe et al. (Citation2020), enables one to meet basic needs and wants and stay out of debt.

“Living comfortably/no hardships” was described by households as having a comfortable life, characterised by being employed, having adequate income, living in a comfortable house and enjoying good health. This observation concurs with that of Gweshengwe et al. (Citation2020), who found living in hardship as a sign of poverty in Brunei.

“Being healthy” was defined by households as being free from serious or chronic sickness. The households considered “being healthy” as valuable as it enables a person to enjoy livelihood opportunities such as employment, operating a business and farming; to have an improved life expectancy, prolonging his or her time with family, and to stop worrying about medical bills or being a burden to the family in terms of needing care and money for treatment.

“Harmonious and happy family” was defined by households as having peace, unity, love and joy in a family. It strengthens family bonds and helps families to easily solve conflicts or be resilient in the face of life challenges. Moreover, a harmonious and happy family is a source of hope.

“Well connected or networked socially”: according to the households, people with high QoL have sound social capital. By definition, social capital refers to norms relating to social control and relationships (networks) for support and securing benefits (Barkus & Davis, Citation2009; Brand, Citation2002; Ostrom, Citation2009; Portes, Citation1998). As the households asserted, a strong social capital ensures the availability of support or assistance from extended families and friends. Hassan (Citation2017) notes, moreover, that since Brunei is a collective society, family and social groups are important. This, according to Hassan (Citation2017), is a common characteristic of Southeast Asian societies.

“Adequate religious faith and knowledge”: according to the households, a solid religious grounding helps people, especially children, to guard against any immoral activities. Households viewed efforts or activities not adequately grounded in religious faith and knowledge as not worthwhile.

From the analysis made of the findings relating to the descriptions of “high QoL”, two observations were made. Firstly, households’ conceptualisation of “high QoL” is in keeping with the government’s conceptualisation of QoL. That is to say that, with the exception of the “fulfilled basic needs” expressed using the basic needs lens, the descriptions of a “high QoL” given by households are construed in terms of functionings. Secondly, what constitutes a high QoL in Brunei is similar to that of other countries in the Southeast Asian region. As the case in Brunei, health, home, job, family and food are the five most important QoL aspects in Singapore, Malaysia and Cambodia (Inoguchi & Fujii, Citation2013). However, what is possibly unique about Brunei is the fact that car ownership is viewed as necessary for one to enjoy a high QoL. Inoguchi and Fujii (Citation2013), in their study of quality of life in Asian regions, did not select car ownership as one of the domains of high QoL. This, theoretically, is not unexpected, as the majority of Asian countries like Singapore, Korea, Japan, and China do not regard owning a car as a necessity.

4.3. High Quality of Life—Comparison between urban and rural areas

The meaning QoL varies according to context (Inoguchi & Fujii, Citation2013; Yuan et al., Citation1999). This is not unexpected, as urban and rural contexts have different culture and resource endowments. However, Shucksmith et al. (Citation2009), in their comparative study of QoL of urban and rural areas in the European Union (EU), concluded that urban-rural difference in terms of QoL is less marked in rich countries, particularly in the EU, but rather more noticeable in poor countries in the East and South. This begs the question as to whether Brunei, an oil-rich country with a GDP of USD 13.5 billion (World Bank, Citation2020) and located in the East, would have varying definitions of high QoL between urban and rural. To address this, the study compared the descriptions of high QoL in Brunei between urban and rural areas (Table ).

Table 2. Comparison of the descriptions of a “high QoL” in urban and rural areas

As Table shows, both urban and rural areas have a similar list of the most expressed descriptions of a high QoL. Specifically, “fulfilled basic needs”, “being financially secure”, “being well educated”, “having a well-paying and permanent job” and “living comfortably/no hardships” are at the core of what constitutes a “high QoL”, irrespective of the geographical location in Brunei. However, there are descriptions of a “high QoL” that were only mentioned in urban areas and vice versa. By way of example, “able to make a living from farming” was only expressed by households in rural areas, while “owning a business” was exclusively mentioned by those in urban areas. This does not imply that farming is exclusive to rural areas, nor does it mean that owning a business is limited to urban areas. Rather, based on our observations, farming is one of the main sources of income in rural areas in Brunei, while entrepreneurial activities are a growing trend in urban Brunei as a means of earning a side income for many or main income source for those who cannot secure employment elsewhere.

From the comparison, the study concluded that what constitutes a high QoL is, by and large, similar in urban and rural areas of Brunei. This conclusion confirms the observation of Shucksmith et al. (Citation2009) that the difference in urban-rural perceptions of what constitutes a high QoL is less marked in rich countries. In rich countries, rural areas are less deprived than those in poorer countries (Shucksmith et al., Citation2009). This is the case in Brunei, where most rural areas have a better infrastructure (roads, potable water and electricity), have access to affordable health services and education, and depend on urban markets and employment for a livelihood (Gweshengwe, Citation2020; Gweshengwe et al., Citation2020).

4.4. Assessment of Brunei’s conceptualisation of Quality of Life

Conceptualisation of QoL in Brunei satisfies Cummins (Citation2005) principles for QoL conceptualisation discussed earlier. As the findings reflect, both the government and Bruneians construe QoL as a multidimensional phenomenon and acknowledge the effect of personal and contextual factors on QoL. The “ends” and “means” presented in Table and the descriptions of a high QoL in Figure reflect the varied dimensions of QoL and the influence, on QoL, of age, gender, class as well as the socio-economic and environmental characteristics of people in Brunei. The conceptualisation also fulfils the principle that QoL has same elements for all people in a society, but with variations in terms of the value of individual elements. This is evidenced by the fact that the government’s conceptualisation of QoL is in keeping with Bruneians’ descriptions of a high QoL. The frequencies of what Bruneians consider to be elements of high QoL (Figure ) demonstrate the variations in the significance accorded to the elements. Moreover, Brunei’s conceptualisation of QoL incorporates both objective and subjective components of QoL. The “ends” and “means” presented in Table contain both objective (relating to education, health, public security and environment) and subjective (such as a harmonious and peaceful life) elements of QoL. Finally, the conceptualisation satisfies the principle that QoL is improved by self-determination, resources, purpose in life and a sense of belonging: these elements are well reflected in the “ends” and “means” presented in Table and the descriptions of a high QoL in Figure , which are comprehensive and all-inclusive. In addition, QoL improvement initiatives receive the lion’s share of the national budget (Gweshengwe & Hassan, Citation2019). In light of the observations made above, Brunei’s conceptualisation of QoL is sound.

5. Conclusion

This study examined the Government of Brunei’s conceptualisation of QoL and the descriptions of a high QoL in Brunei. It also shed light on the lenses through which QoL is conceptualised in the country and assessed Brunei’s QoL conceptualisation. For the government’s conceptualisation of QoL, the study analysed the “ends”, “means” and measurement method of the QoL component of the country’s long- and mid-term development plans. The study depended on data from households for the description of high QoL in Brunei. It employed the principles for QoL conceptualisation put forward by Cummins (Citation2005) to assess the conceptualisation of QoL within the country.

As the study found, the government conceptualises QoL as having a population that is well-educated, highly skilled, healthy, responsible, charitable and safe from life-threatening phenomena; lives harmoniously and peacefully; and engages effectively in economic and social activities. The conceptualisation is anchored on the capability approach, which is a sound approach for construing QoL.

High QoL in Brunei is described as, among other aspects, “fulfilled basic needs”, “being financially secure”, “being well-educated”, “having a well-paying and permanent job”, “living comfortably/no hardships”, “being healthy” and having ‘harmonious and happy family. The descriptions derived from urban and rural areas are, by and large, similar. Moreover, these descriptions are similar to those held in other Southeast Asian countries. In Brunei, High QoL is mainly construed through the capability lens.

Brunei’s QoL conceptualisation is sound since it fulfils Cummins (Citation2005) principles for the conceptualisation of QoL. It construes QoL as a concept that is multidimensional and influenced by personal and contextual factors. It has the same elements for all people but with variations in terms of the value placed on individual elements; it has both objective and subjective components; and is improved by resources, self-determination, purpose in life and sense of belonging.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of our research assistants: Faiz Zul Hamdi, Nurul Hafizah Matzini, Nur Khairi, Mahrina Pungut, Faith Izasuriawati and Janet Stori; and translators: Safwan Jalil, Lawrence Wee and Suraya Hussain. Also, we wish to express our sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Blessing Gweshengwe

Blessing Gweshengwe is a Poverty/Quality of Life Specialist. He holds a PhD in Geography (Poverty Analysis) from the Universiti Brunei Darussalam; MA in Poverty and Development from the University of Sussex, United Kingdom; and BSc Honours Degree in Rural and Urban Planning from the University of Zimbabwe. He is a lecturer in the Department of Rural and Urban Development, Great Zimbabwe University. His research interests include quality of life, poverty, sustainable livelihoods and urban planning.

Noor Hasharina Hassan

Noor Hasharina Hassan (PhD) is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. She teaches modules on social welfare and exclusion, sustainable development and urban economy for the Geography, Environment and Development Programme. Her research interests include poverty, quality of life, consumption and housing.

Hairuni Mohamed Ali Maricar

Hairuni Mohamed Ali Maricar (PhD) is a former lecturer (retired) for the Geography, Environment and Development Programme, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Her research interests include quality of life, poverty and migration.

References

- Alkire, S. (2005). Why the capability approach? Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 15–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/146498805200034275

- Alkire, S. (2008). The capability approach to the Quality of Life. A background paper for the Commission on the Measurement of economic performance and social progress.

- Arif, M., Rao, D. S., & Gupta, K. (2019). Peri-urban livelihood dynamics: A case study from Eastern India. Forum Geographic, XVIIIII(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.5775/fg.2019.012.i

- Barkus, V. O., & Davis, J. H. (2009). Introduction: The yet undiscovered value of social capital. In V. O. Barkus & J. H. Davis (Eds.), Social capital: Reaching out, reaching in (pp. 1–16). Edward Elgar.

- Betti, G., Soldi, R., & Talev, I. (2016). Fuzzy multidimensional indicators of Quality of Life: The empirical case of Macedonia. Social Indicators Research, 127(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0965-y

- Bowen, G. A. (2008). Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085301

- Brand, C. (2002). Making the livelihoods framework work (RUP No.20). Department of Rural and Urban Planning, University of Zimbabwe, Harare.

- Brunei Darussalam Long-term Development Plan. (n.d.). Brunei Darussalam long-term development plan: Wawasan Brunei 2035 – Outline of Strategies and Policies for Development (OSPD) 2007 – 2017 & National Development Plan (RKN) 2007 – 2012. Government of Brunei Darussalam.

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2008). The world factbook 2009. Skyhorse Publishing.

- Cummins, A. (2005). Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(10), 699–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00738.x

- Department of Economic Planning and Development. (2012). Tenth national development plan (2012 – 2017).

- Department of Economic Planning and Statistics. (2019). Report of the mid-year population estimates 2019. Department of Statistics, Ministry of Finance and Economy.

- Dijkers, M. (2007). “What’s in a name?” The indiscriminate use of the “Quality of life” label, and the need to bring about clarity in conceptualizations. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(1), 153–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.016

- Farrar, J. (2012). An assessment of human development in Uganda: The capabilities approach, millennium development goals, and human development index. Josef Korbel Journal of Advanced International Studies, 4, 74–101. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=advancedintlstudies

- Fifth National Development Plan. (n.d.). Fifth National Development Plan 1986 – 1990. Ministry of Finance.

- Graham, C. (2008). Measuring quality of life in Latin America: Some insights from happiness economics and the Latin Barometro. In V. Moller, D. Huschka, & A. C. Michalos (Eds.), Barometer of Quality of Life around the globe: How are we doing? (pp. 71–106). Springer Netherlands.

- Graham, C., & Behrman, J. R. (2009). How Latin Americans assess their Quality of Life: Insights and puzzles from novel metrics of well-being. In C. Graham. & L. Eduardo (Eds.), Paradox and perception: Measuring Quality of Life in Latin America (pp. 1–21). Brookings Institution Press.

- Gratton, C., & Jones, I. (2010). Research methods for sports studies. Routledge.

- Gweshengwe, B. (2020). Understanding poverty in Brunei Darussalam [PhD Thesis]. Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

- Gweshengwe, B., & Hassan, N. H. (2019). Knowledge to policy: Understanding poverty to create policies that facilitate zero poverty in Brunei Darussalam. Southeast Asia: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 19, 95–104. https://fass.ubd.edu.bn/SEA/vol19/SEA-v19-Gweshengwe-NoorHasharina.pdf

- Gweshengwe, B., & Hassan, N. H. (2020). Defining the characteristics of poverty and their implications for poverty analysis. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1768669

- Gweshengwe, B., Hassan, N. H., & Maricar, H. M. A. (2020). Perceptions of the language and meaning of poverty in Brunei Darussalam. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 55(7), 929–946. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0021909619900218

- Hassan, N. H. (2017). Everyday finance and consumption in Brunei Darussalam. In V. T. King, I. Zawawi, & N. H. Hassan (Eds.), Borneo studies in history, society and culture (pp. 477–492). Springer Singapore.

- Healey, J. H. (2009). Statistics: A tool for social research. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Hick, R. (2012). The capability approach: Insights for a new poverty focus. Journal of Social Policy, 41(2), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279411000845

- Hick, R. (2014). Poverty as capability deprivation: Conceptualising and measuring poverty in contemporary Europe. European Journal of Sociology, 55(3), 295–323. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975614000150

- Inoguchi, T., & Fujii, S. (2013). The Quality of Life in Asia 1: A comparison of Quality of Life in Asia. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Kreitler, S., & Kreitler, M. M. (2006). Multidimensional Quality of Life: A new measure of Quality of Life in adults. Social Indicators Research, 76(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-4854-7

- Mandzuk, L. L., & McMillan, D. E. (2005). A concept analysis of quality of life. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing, 9(1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joon.2004.11.001

- McKenna, S. P., & Doward, L. C. (2004). The needs-based approach to Quality of Life. Assessment Value in Health, 7(S1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.7s101.x

- McNabb, D. E. (2010). Research methods for political science: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. M.E Sharpe.

- Mishra, S. V. (2015). Understanding needs and ascribed Quality of life – Through maternal factors – Infant mortality dialectic. Asian Geographer, 32(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10225706.2014.962551

- Moonsa, P., Budts, W., & De Geest, S. (2006). Critique on the conceptualization of quality of life: A review and evaluation of different conceptual approaches. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(7), 891–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.015

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9(2–3), 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077926

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Ostrom, E. (2009). What is social capital? In V. O. Barkus & J. H. Davis (Eds.), Social capital: Reaching out, reaching in (pp. 17–38). Edward Elgar.

- Peruniak, G. S. (2010). A Quality of Life approach to career development. University of Toronto Press.

- Phillips, D. (2006). Quality of life: Concept, policy and practice. Routledge.

- Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and application in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Pramono, R. W. D., (2016). Capability approach for well-being evaluation in regional development planning: Case study in Magelang Regency. Central Java, Indonesia [DPhil Thesis]. Universitas Gadjah Mada.

- Pukeliene, V., & Starkauskiene, V. (2011). Quality of life: Factors determining its measurement complexity. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 22(2), 147–156. http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.22.2.311

- Qizilbash, M. (2006). Capability, happiness and adaptation in Sen and J. S. Mill. Utilitas, 18(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820805001809

- Robeyns, I. (2005). The capability approach: A theoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/146498805200034266

- Robeyns, I., & Van der Veen, R. J. (2007). Sustainable quality of life: Conceptual analysis for a policy-relevant empirical specification. Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

- Rogerson, R. J., Findlay, A. M., Morris, A. S., & Coombes, M. G. (1989). Indicators of quality of life: Some methodological issues. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 21(12), 1655–1666. https://doi.org/10.1068/a211655

- Rokicka, E. (2014). The concept of ‘Quality of Life’ in the context of economic performance and social progress. In D. Eibel, E. Rokicka, & J. Leaman (Eds.), Welfare state at risk: Rising Inequality in Europe (pp. 11–34). Springer International Publishing.

- Sen, A. (1985). Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. The Journal of Philosophy, 82(4), 169–221. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2026184

- Sen, A. (1987). Freedom of choice: Concept and content. WIDER Working Paper 25. World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. (2008). The economics of happiness and capability. In L. Bruni, F. Comim, & M. Pugno (Ed.), Capability and happiness (pp. 16–27). Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. K. (1989). Development as capability expansion. Journal of Development Planning, 19, 41–58.

- Shin, D. C., & Inoguchi, T. (2009). Avowed happiness in Confucian Asia: Ascertaining its distribution, patterns, and sources. Social Indicators Research, 92(2), 405–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9354-0

- Shucksmith, M., Cameroon, S., Merridew, T., & Pichler, F. (2009). Urban-rural differences in quality of life across the European Union. Regional Studies, 43(10), 1275–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802378750

- Shye, S. (2010). The motivation to volunteer: A systemic quality of life theory.”. Social Indicators Research, 98(2), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9545-3

- Stanton, E. A. (2007). The human development index: A history. Political Economy Research Institute Working Paper Series No. 127. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- Stewart, F. (1996). Basic needs, capabilities and human development. In A. Offer (Ed.), In pursuit of the Quality of life (pp. 46–65). Oxford University Press.

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2010). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

- Tay, L., Kuykendall, L., & Diener, E. (2015). Life satisfaction and happiness – The bright side of quality of life. In W. Glatzer (Ed.), Global handbook of well-being and quality of life (pp. 839–853). Springer.

- United Nations Development Programme. (1990). Human Development Report 1990. Oxford University Press.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2019). Human Development Report 2019. Beyond income, beyond averages, beyond today: Inequalities in human development in the 21st century. New York.

- Ventegodt, S., Merrick, J., & Andersen, N. J. (2003). Quality of life theory I. The IQOL theory: An integrative theory of the global quality of life concept. The Scientific World Journal, 3, 1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2003.82

- Wong, S. P. (2012). Understanding poverty: Comparing basic needs approach and capability approach. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2066179

- World Bank. (2020). Brunei Darussalam. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/country/brunei-darussalam

- Yuan, L. L., Yuen, B., & Low, C. (1999). Quality of Life in cities – Definitions, approaches and research. In L. L. Yuan, B. Yuen, & C. Low (Eds.), Urban Quality of Life: Critical issues and options (pp. 1–12). School of Building and Real Estate, National University of Singapore.