Abstract

Situated close to the Golden Triangle region, and lying across important South-East Asian region traffic routes, Vietnam has a long history of drug use. The negative attitudes among Vietnamese people towards drug use have emerged from the past actions of colonial governments and recently been influenced by social media and political factors. Yet the reality of drug use is more complex, and it is essential to move beyond the overly simple axiom that drug use causes addiction and crime. Combining historical narratives and grey literature, this paper argues that drug use has been politically and socially constructed in Vietnam rather than based on evidence or rationale. Moving forward on harm reduction in drug policy, Vietnam should need more specific actions with its clear plans to at least support drug users during and post detoxication in voluntary community’s models as well as methadone maintenance treatment rather than in compulsory treatment centres.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Over 35 years implementing the Renovation Period (Doi Moi in Vietnamese) since 1986, Vietnam has achieved several milestones to develop economic and maintain society as well as enhance international cooperation. From a low-income country to a middle-income country, Vietnam contributed to support the quality of life and ensure sustainable development for all groups. However, for people who use drugs (PWUDs), they are still facing practical stigmas and potential vulnerabilities during detoxicating and rehabilitating. Although the government had efforted to shift from punitive approach to harm reduction in recent years, particularly after decriminalizing drug use in 2009, applying voluntary community and methadone maintenance treatment for PWUDs still limited in comparison to utilizing compulsory detention centres. As the first study in Vietnam, through analysing from long history in the past to modern approaches we use social norms and political constructions of drug use to demonstrate the process of changes and attitudes for PWUDs.

1. Introduction

The history of drug use in Vietnam should be assessed based on multifaceted approaches. Throughout Vietnamese history, drug use has been negatively viewed. It was first seen as a national enemy of the state because the French were seen as using opium as a means to control and poison Vietnamese people (Windle, Citation2018). This perception remained until Vietnam unified in 1975. The consequences of drug use from Vietnam’s wars were difficult as Vietnam had to deal with a significant number of people who drug users (PWUDs) who remained dependent on drugs. Drug use was then seen as a leftover of old regimes and external contamination from the West. The tradition of viewing drug use as a destructive force and social evil was documented in the Vietnam 1992 Constitution. Beyond charting this history, this article also examines how drugs and harm are defined within Vietnam.

The current drug classification is determined by two main factors, including historical issues (drugs like opium and cannabis are associated with the colonial government)Footnote1 and international instruments (such as the 1961 UN Narcotic Drug Convention and the UN 1971 Psychotropic Substances Convention). These have led to a robust official approach that treats legal and illegal drugs quite differently. Accordingly, within Vietnam, harms are generally seen only to be caused by illicit drug use and those taking these drugs. These perceptions of drugs and harm have fuelled an abstinence philosophy, which promotes punitive measures against drug use and drug users. From a Vietnamese perspective, definitions of “harm” generally overlook the complexity of drug use, or the role of social, environmental and legal factors which can cause more harm than the drugs themselves. Importantly, these negative social perceptions of drug use are led by current legal classifications, but they are also based on social and political constructions as other countries. This article argues that the unfavourable attitudes to drug use in Vietnam have historically served political purposes. It has been a response of Vietnam politicians to external influences (from colonial forces to increasing market neoliberalism). It has also reflected the Vietnamese media and political discourse that has shaped how Vietnamese people perceive drug use and those who take drugs. These provide a basis for understanding why drug use is socially and politically constructed as a “social evil” and why those taking drugs are treated as “outsiders” in Vietnam.

2. Negative perceptions of drug use from history

Situated close to the Golden Triangle region, and lying across important South-East Asian region traffic routes (Laos, Myanmar and Thailand), Vietnam has a long history of producing and consuming opium. Opium was first introduced to Vietnam around the 1600s in the northern mountainous areas before spreading to the whole country over the next centuries (Failler, Citation2000; Y. Nguyen, Citation2001). This section illustrates some vital historical milestones that generally explain why Vietnamese people have negative views towards illicit drug use.

At first, Vietnamese people viewed opium as a medicine that could treat diseases, such as rheumatism or intestinal infections, and relieve pain (Doumer, Citation1903; Failler, Citation2000, Citation1993). Yet they also recognised the potential influences of opium for harm that led to addiction when overused (Failler, Citation1993, Citation2000). To prevent the expansion of opium cultivation and opium addiction, the first national regulation forbidding opium cultivation was promulgated by Kinh “Canh Tri III” of the feudal state called “Dai Viet” in 1665 (Vu, Citation2007). This first prohibitive regulation elaborated that:

… men and women use opium to satisfy their libido; thieves use it as a precursor to steal other people’s property … opium use also causes fires and bankruptcies … it severely damages people’s health, and those who take it are not as normal persons … therefore, from now all mandarins and citizens have to stop cultivating and trading opium … and for those who are growing or possessing opium, they have to demolish it immediately (cited in Vu, Citation2007, p. 13)

Although the feudal states outlawed opium consumption and also issued policies against opium trafficking from China, opium use still spread into other highland and lowland regions (Failler, Citation2000; Lau, Citation1993). However, the efforts of the feudal states generally failed because of the annexation of Vietnam by France’s colonial policies in 1858 (Failler, Citation2000; Quang, Citation2009). Shortly after this invasion, the newly installed colonial government established a monopoly regulating the production and sales of opium in Vietnam to finance the substantial initial expenses of colonial rule (Failler, Citation1993; Nguyen & Scannapieco, Citation2008).

In 1899, the colonial state reorganised the opium business by scaling up sales and significantly reduced prices to make opium more affordable to poor people (Doumer, Citation1903; Failler, Citation1993; McCoy et al., Citation1972). By 1900, the tax on the drug had contributed to more than 50% of all colonial state revenue (Edington, Citation2016; Failler, Citation1993). More dens and shops were established to meet increased demand, and, by 1918, there were 1,512 dens and 3,098 retail shops selling and distributing opium in Vietnam (McCoy et al., Citation1972). Although there was a vigorous international crusade again the “evils of opium”, which forced colonial administrations to reduce opium business elsewhere, French officials continued to expand the opium trade (Failler, Citation1993; McCoy et al., Citation1972).Footnote2 By the early 1940s, it was estimated that around 2% of the Vietnamese population used opium (Vuong et al., Citation2012a). At that time, the poppy was not only seen as one of the leading financial pillars of colonialism but as a powerful symbol of French intervention and oppression (McCoy et al., Citation1972).

After Vietnam gained independence from France in 1945, following the first Indochina War, President Ho Chi Minh linked the opium monopoly to the systematic poisoning of the Vietnamese people, criticising the French colonialists “acting against principles of humanity and justice … [who] had forced the use of opium on the people to weaken our race” (Edington, Citation2016, p. 326). As a social norm between the colonial regime and feudal remnants at that time, opium use has been recognised as a “social evil” (Y. Nguyen, Citation2001). Thus, the new government requested the strict prohibition of opium use and emphasised that the prevention of opium smoking (Y. Nguyen, Citation2001; Rapin et al., Citation2003). However, the new government faced a dilemma in entirely eradicating opium production and consumption (Nguyen & Scannapieco, Citation2008). While considering these drug activities as expressions of colonial exploitation that were “incompatible with new Vietnam’s socialist lifestyle” (Edington, Citation2016, p. 326), the state had to consider their role in the socio-economic reality of highland areas. This tension led to selective opium policies based on beneficial motivations rather than geography-based distributions among different regions in Vietnam at that time (Y. Nguyen, Citation2001). Accordingly, while opium cultivation and consumption were tolerated in the highlands, the new government aggressively sought to restrict opium production and use in all other regions (Bankoff & McCoy, Citation2007; Rapin et al., Citation2003). These selective drug policies were prolonged during the “Second Indochina War” (1954–1975).

Unfortunately, because the country was at war with America, no precise information or documentation is available in terms of how many people smoked opium and other drugs, how prevalent drugs were, or how drug production took place during this period in North Vietnam (Rapin et al., Citation2003). Meanwhile, in South Vietnam, heroin, cannabis and amphetamine consumption had become a severe problem, particularly among American and Vietnamese soldiers,Footnote3 who worked for the Southern Vietnamese Government. By the early 1970s, it was estimated that 35% of American soldiers in Vietnam were using heroin, followed by cannabis and synthetic drugs (mainly amphetamine) with around 29% and 5% respectively (Menninger & Nemiah, Citation2008). Before the end of the second Indochina war (1975), there were roughly 300,000 drug users, including Vietnamese, American soldiers and citizens, within the Southern government border (Vu, Citation2007).

After 1975, alongside with pushing former officials of the South Vietnam regime and others involved in protests against the newly unified government into rehabilitation at the same time as PWUDs (Failler, Citation2000; Y. Nguyen, Citation2001; Rapin et al., Citation2003). These camps are considered to be the foundation of current compulsory treatment centres since the 1990s, known as 06 centres (Edington, Citation2016, p. 328). The communist government deployed restrictive drug policies to address “a vestige of an inglorious past” (Edington, Citation2016, p. 329). Drugs were again regarded as a leftover of imperialist power; therefore those who produced or consumed drugs were seen to have “personal corruption” or “external contamination” (Edington, Citation2016, p. 330). This rhetoric of contamination has continued, albeit in different ways, particularly given the strong emphasis on linking HIV/AIDS prevention and eradication with efforts to combat drug use. Article 61 of the 1992 Vietnamese Constitution (1992) declares drug use to be a dangerous social disease and a social evil that needs to be immediately eradicated (Windle, Citation2015). This legal foundation has led a two-way process, including intensifying a broad government campaign against drug use and emonising of drug use reflected in law, which in turn further stigmatises PWUDs.

3. Definition of “Drugs” and “Harm”

The Vietnamese translation of the word “drug” is a Chinese-Vietnamese compound word: “Ma Tuy” in which ‘Ma’Footnote4 refers to something that paralyses people, while “Tuy” means something that causes people to get drunk (Vu, Citation2000). The term “drugs” means “illicit drugs” or “narcotics” in the Vietnamese context. At that time, Ma Tuy refers to opium (not yet to heroin and amphetamine until the end of the 1990s) and thus, to some extent, it is widely used to highlight harmful substances. For instance, according to the Vietnamese dictionary, Ma Tuy refers to all substances that cause people to feel ecstatic or drowsy, and that will cause dependency if people use them many times (Vu, Citation2007). Critically, language plays an essential role in explaining why Vietnamese people see illicit drugs as unfavourable while other drugs like alcohol and tobacco are regarded in neutral ways, or socially and culturally embraced within Vietnamese society. For example, alcohol and tobacco are translated in Vietnamese as “Ruou” and “Thuoc La” respectively, while medicines are called “Thuoc”. In practice, Ruou and Thuoc La have neutral meanings; in contrast, Thuoc has positive implications to treat illnesses and to save people (Ministry of Health, Citation2016). Although Ruou and Thuoc La are seen as harmful from the government’s perspective, they are socially and culturally adopted as normalised drugs for users.

In reality, alcohol and tobacco have caused plenty of harm to Vietnamese society. For instance, the Ministry of Health (Citation2016b) reports that there were, on average, around 44,000 fatalities related to alcohol and 4,000 associated with tobacco per year. In contrast, the figure for drug-related deaths is about 10,000 (3,000 overdoses and 7,000 associated with HIV and other blood-borne diseases). Notably, in 2012, it was reported that Vietnamese people spent over US$3 billion on beer and alcohol while, ironically, Vietnam—an agricultural country—only made around US$3.5 billion (gross) from rice exports (VTV, Citation2013). In Vietnam, alcohol and tobacco cause more problems than illicit drugs, but this seems to be ignored within Vietnamese lawmakers, politics, and academia’ debates without scientific recognitions and evidences.

All illicit drugs or narcotic drugs in Vietnam are regulated in the 2000 Drug Control Law (amended and supplemented in 2008). This law divides drugs into four schedules,Footnote5 for example:

Schedule 1 contains the “extremely dangerous narcotic substances” which are strictly prohibited, such as cannabis, heroin, and MDMA (ecstasy) or morphine methobromide;

Schedule 2 refers to toxic substances that are limited to use in medical therapy or scientific studies, such as amphetamine, methamphetamine, methadone, cocaine, morphine, or opium;

Schedule 3 covers the stimulants that can be used in medicine, science or experiments, including ketamine, bromazepan, buprenorphine or triazolam;

Schedule 4 encompasses the precursor substances used for preparing synthetic drugs, including addictive and psychotropic substances, such as acetic acid, acetone, pseudoephedrine (PSE) and ephedrine (substances to produce synthetic drugs).

These Vietnam’s schedules have been driven by and are based on outdated drug classifications that have emerged from the UN’s 1961 Narcotic Drug Convention and the 1971 Psychotropic Substances Convention after Vietnam signed and ratified these Conventions in 1996. Under the influence of these instruments, Vietnam calculates heroin, cannabis, or LSD as the most dangerous drugs, followed by amphetamine, opium, cocaine or methadone; meantime, alcohol and tobacco did not involve into legislative prohibition for users. Still, they are not mentioned under the Vietnamese drug schedules, while LSD and Buprenorphine are among the least problematic, but are categorised as Schedule 1 and 2 respectively (Nutt et al., Citation2007). Similarly, while cannabis is decriminalised in countries such as the Netherlands or Portugal, it is classified in Schedule 1 as one of the most dangerous drugs in Vietnam. Perhaps, when regulating these narcotics’ listing in the law, Vietnam’s government has not yet clarified as clearly scientific as practically possible to separate legal and illegal drugs. As Buchanan and Young (Citation2000, p. 410) argued about misleading separation of legal and illegal drugs that

The consumption of legal and illegal drugs for pleasure should be recognised as a highly complex social issue, but instead, it has been presented within a reductionist framework. Within certain boundaries, the government sees the use of legal drugs (primarily alcohol and tobacco) as wholly acceptable. In contrast, the use of illicit drugs in any circumstance is seen as dangerous and harmful.

As a consequence of drug definitions and classification, Vietnamese government officials and policymakers have presented a narrow and misleading perception of harms related to illicit drugs. Vietnamese authorities tend to frame harm as being caused by illegal drugs or unauthorised drug users. Yet, almost Vietnam’s policymakers, politicians, and scholars often see the harm as being caused by the ravages of drugs and their inherent psychoactive properties, which lead to brain disease (addiction) and danger (MOLISA, Citation2015; T. P. Nguyen, Citation2002; Vietnamese Government, Citation2014; Vu, Citation2007). This perception of harm in Vietnam is not unique. The International Network of People Who Use Drugs (Citation2014) even emphasises the physical harms of drugs and drug use, such as addiction, blood-borne diseases, the higher risk of non-fatal and fatal overdoses, or a greater chance of premature death. In Vietnam, in general, there are no distinctions made between drug misuse and recreational drug use, so all illegal drug use is seen as harmful, and PWUDs are referred to as being addicted to drugs, which is generally not applied to legal drugs like alcohol or tobacco.

From these approaches, Vietnamese drug law enforcement agencies have advanced the idea that reducing harm means preventing illegal drug use, controlling drug users and importantly promoting a so-called drug-free society (Vuong, Citation2016). In reality, the Vietnamese government tends to exacerbate the danger of harm from illicit drugs to prevent the escalation of drug use and importantly, to control and punish drug users (Windle, Citation2015). Their representations of harm are generally misleading and not necessarily based on evidence, science or rationality (Nutt et al., Citation2007). Further, only considering harm from the harmful effects of drugs generally ignores the fact that many harms are caused by prohibitionist policies, not the drugs themselves, and such harms would be evident if governments treated alcohol or tobacco in the same way.

In short, Vietnamese definitions of “harm” generally overlook the complexity of drug use, and the role of social, environmental or legal factors that cause more harm than drugs themselves. For example, Vietnamese drug users often experience high levels of social dislocation as a result of their stigmatisation (Hong et al., Citation2011). These social and environmental disadvantages often drive drug users “underground”, isolating them from normative society, and reducing their opportunities for education, outreach or employment. The environment of criminalisation and punishment also means that most Vietnamese drug users are reticent about accessing health or social services for fear of exposing themselves. One typical example is that many drug users do not call an ambulance (and can die of overdose) because they do not want to face prosecution and punishment for any drug use. Overall, this narrow perception of “harm” has led Vietnam’s drug policy to become punitive and abstinence-based. As the article will demonstrate, Vietnam’s drug policy is based on a social and political construction rather than on evidence-based researching.

4. Political and social constructions of drug use

The history of drug use in Vietnam has, as shown previously, played an essential role in shaping negative attitudes and perceptions toward drug use and drug users. Yet alongside this history, many other factors have strongly influenced the way people perceive drug use and users, including (i) external contamination, (ii) addiction, (iii) crime, and (iv) media influences. This section illustrates how these political and socio-cultural elements impact on the perceptions of “evil” drug use in Vietnam. Importantly, this section reinforces that fact that in Vietnam, as in other countries, drug use is politically and socially constructed.

4.1. External contamination

From 1986, under the “Renovation” policy (Doi Moi in Vietnamese), Vietnam inaugurated a profound economic and social transformation. This Doi Moi shifted the country from a centrally planned economy to one that is market-oriented. The government subsequently loosened controls on domestic and foreign goods and opened opportunities for private businesses and foreign investment, and even foreign-owned enterprises. The country has transformed from one of the poorest nations into one of the Southeast Asia’s most prosperous economies. Yet the Doi Moi policy has presented Vietnam with new challenges, not least as the Vietnamese government has sought to protect and consolidate its power and authority in a market-oriented economy. As Beresford (Citation2008) argued, the Vietnamese government not only has to handle new demands arising from its population but to grapple with aid donors and foreign investors who tend to influence the country’s economic policies. Although the country has some successes regarding the rise in living standards and the reduction of poverty, the Doi Moi policy has also resulted in deepening inequalities (Phinney, Citation2008). Some welfare subsidies and social safety nets, such as healthcare or educational support, have been cut off (Phinney, Citation2008). As a result, PWUDs who are regarded as a burden to society have inevitably encountered a conspicuous lack of social and health service support.

With the advent of the market-oriented economy, the Vietnamese government has also tried to control the effects of market liberalisation upon national identity (Wilcox, Citation2000). The term “Van Minh” (being civilised) is used in both official and popular discourses to manage and make sense of the local presence of the global economy (Bradley, Citation2004). Promoting Van Minh discourse is regarded as an attempt by Vietnam’s government to strengthen the national spirit, revitalise tradition and preserve national culture (Pettus, Citation2004). As Edington (Citation2016, p. 329) explains:

In contemporary nationalist discourse, Van Minh rests on the articulation of a seamless Confucian past alongside the imperatives of the neoliberal marketplace and its implicit cultural dangers. Van Minh has, therefore, come to embody the convergence of the material and cultural ambitions of the Vietnamese postcolonial state in the forging of national identity.

The state’s campaign for attaining Van Minh was also intended to “anchor Vietnam’s timeless spiritual past as an ethical and moral counter to the forces of Western Capitalism” (Edington, Citation2016, p. 329). For example, drug use, prostitution, karaoke bars, massage parlours and pornography with Western models were deemed to represent “social evils”, “dirt” and an unhealthy lifestyle, which could degenerate good “morality” (Rydstrøm, Citation2006, p. 284). Drug use is highlighted as a result of negative values from the West, which are considered to be opposed to original Vietnamese values. Indeed, Windle (Citation2018, p. 373) pointed out “as alien conspiracies … are founded in stereotypical portrayals of ‘foreign’ criminals and “foreign” drugs undermining … and even, French had forced [Vietnamese] to use opium.’ In response to the fear of external contamination (mainly drug misuse), in 1994, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Vo Van Kiet requested the mobilisation of mass organisations, state bureaucracy and the public at large to exercise all “poisonous” forces from Vietnam society, such as prostitution, drug and alcohol addiction or gambling (Edington, Citation2016, p. 331).

Also, the externally destructive forces are argued to cause the degradation of Vietnamese young people. That is, according to a 2015 MOLISA report, around 76% of registered drug users (202,000 individuals) were aged below 35 years old, and about 60% (over 92,000) had first tried drugs before the age of 25 years (MOLISA, Citation2015). It was reported that young people have the highest consumption rates of illicit drugs and also legal drugs like alcohol and tobacco (Ministry of Health, Citation2018). Importantly, it must be acknowledged that most of these young people do not have problems with their drug use at all. However, regarding ideology, leaders of Vietnam’s Communist-State always highlight the importance of protecting the young generation from drug use to ensure that the future decision-makers of Vietnamese society cannot addict. In comparison to China, Chan et al. (Citation1999) argued that Vietnam wants to prevent social evils because if adolescents were influenced by “dirty” foreign forces (drugs and prostitution), the future of Vietnam would be jeopardised. Therefore, those who take drugs are regarded as having low moral standards that violate ‘Vietnamese social conventions’Footnote6 and as copying harmful western lifestyles. Nevertheless, the external factors are not only the reasons to explain negative social and political constructions toward drug use in Vietnam, as other misperceptions are also widespread.

4.2. Drug use inevitably leads to addiction

The Vietnamese government and relevant agencies often propagandise that illicit drug use inevitably causes addiction. Indeed, the idea that using illegal drugs will lead to addiction is presented as an iron law (Frey, Citation1997). As a stigmatising point, under the perception of Vietnamese people, drug use is harmful and addictive. The standard message is that using a drug even once will cause addiction. The conflation between drug use and addiction is such that many families and communities think that all drug users must be sent to treatment centres for detoxification (Hong et al., Citation2011). This confusion has resulted in the widespread use of abstinence-based approaches like compulsory treatment centres. From a Vietnamese perspective, addiction is primarily connected to individual biological or psychological defects.

Accordingly, solutions or interventions against addiction are generally placed at the level of the person, rather than towards social and environmental issues. In Vietnam’s society, as stigmatising and discriminating’ impacts between residents and PWUDs, whenever people see or hear of someone taking drugs, people will view them as “addicts”. This stereotype is widespread because conventional Vietnamese materials and propaganda campaigns frequently claim that people use drugs once and you’re addicted (UNAIDS, Citation2016). This message is widely disseminated across the whole country to influence people to stay away from drug use. The Vietnamese construction of drug use reflects the dominance of “the moral model of addiction”, which is the oldest model used to explain addiction. According to Bauer et al. (Citation2007), addictive behaviours are considered as violating social rules and norms. Thus, punishment and rehabilitation are vital solutions in drug policies to support PWUDs in both physical and moral recovery. Following up this ethical model of addiction explained why Vietnam had a punitive approach to drug use, though the trend and pattern of drug use have still increased since the 2000 Drug Control Law passed to the present.

4.3. Drug use causes crime

There are many conflicts to explain the symbiotic relations between drug use and crime in Vietnam. Firstly, revealing about the leading causes of increasing rate among violent crimes such as robbery, murder, and assaults, Vietnam’s authorities often shifted the blame into PWUDs as key drivers contributed (MPS, Citation2016). At the high-ranking agencies in the government to drug control, both Ministry of Labour, War Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) and Ministry of Public Security (MPS) often emphasise that illicit drug use causes crime or at least is responsible for any increase in the crime rate. For example, the former stated that a large proportion of arrestees’ criminal activity (over 70%) is attributable to PWUDs; meanwhile, the latter highlighted there were several serial killers and armed robbers, at least over 50%, conducted by PWUDs and/or its related methamphetamine’s overdoses (MOLISA, Citation2015; MPS, Citation2016). This type of constructed evidence is used to cement an undeniable connection between drug use and crime, or to put it another way; drug use turns law-abiding citizens into criminals who commit a crime to obtain drugs. Secondly, lacking evidence-based researching to assess and analyse the relations between crime and drug use since the Drug Control Law passed in 2000 until now that created official contests between lawmakers and practitioners. In particular, Vietnam fails to distinguish which mechanism or motive leads Vietnamese drug users to criminal behaviours without either specific studies or official conclusions for this controversial debate, although they do not deny cause-and-effect factors between drug use and crime.Footnote7 However, lacking official statistics and its evidence-based researching are considered as one of the main reasons to lead this ambiguous approach of Vietnam in explanations (Nguyen & Scannapieco, Citation2008; Vuong et al., Citation2012b). In other words, crime and drug use nexus is needed to evaluate and approach based on research-based finding rather than political influences (Bennett & Holloway, Citation2009). Finally, there are unweighting databases to illustrate the link between drug use and crime in Vietnam, both theory and practice. The Vietnamese government only counts PWUDs have been arrested/incarcerated and does not record all those drug users who are engaged in recreational drug use (MPS, Citation2016; Nguyen & Scannapieco, Citation2008). Yet, using only those arrested to argue drug use “causes” crime is contested, particularly when the criminal rate needs to compare among other social and economic factors. Unfortunately, these arguments are not taken into serious consideration in Vietnam based on evidence contributions (Vuong et al., Citation2017). The misperception of the drug use–crime connection has reinforced the standard view that there is an inevitable link between drug use and criminal behaviour. This perception also has a secure relationship with the brain and moral models of addiction in which drug use and users are seen as the drivers of social disorder and crime.

Therefore, enforced abstinence-based approaches, such as punishment, incarceration or detention, are preferred methods for preventing crime. As noted above, challenging Vietnam’s harsh enforcement/prohibition measures is extremely difficult for any Vietnamese researchers. Like elsewhere, the typical stereotypes of the contested drug-crime connection still dominate Vietnamese drug policy and the media.

4.4. Media influence

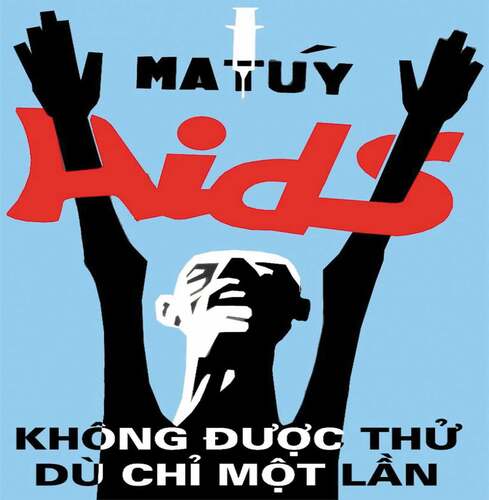

The Vietnamese social and political constructions of drug use are also accompanied by Vietnamese media campaigns, which stereotype drug use as a serious social problem and present drug users as weak-willed and morally corrupted individuals, as blights on the honour of their family and the country as the whole. In particular, attacking the political system/prohibition as a source of crime is extremely sensitive in the country. Blaming drug use for offending has dominated the coverage of the Vietnamese media, and it is embedded in the general public’s mindset. For example, ANTV, a popular television channel in Vietnam, often bombards people with sensational headlines like “drug use and addiction is the shortest path leading to criminal behaviours” (Dinh & Duc, Citation2014). Regarding using symbols in the press, to propagandise drug use and drug users, the Vietnam government has often used caricatures showing the skull and crossbones to indicate the connection between drug use, drug users and the HIV epidemic (Kincaid & Sullivan, Citation2010). As being shown below of Vietnam’s National Committee on AIDS Drugs and Prostitution Prevention and Control, these images cement the fact that drug use is a social evil, not a public health issue.

As Taylor (Citation2008, p. 374) argued, caricatures that portray drug use in the media generally provide:

… a simplistic understanding of the situation and reinforces the belief that something can be done realistically and relatively quickly about the drugs crime ‘problem’ if you stop drug use amongst ‘this’ group via the criminal justice system

In Vietnam, as a communist country like China, the press plays as a principal ideology to convey the leaders’ thoughts and provisions in everything, including drug control’s policies. Therefore, it is not surprising when the government continues to use negative caricatures stereotype that drug use is a social evil and that people should avoid this high-risk behaviour. Almost every day, Vietnamese people are bombarded with breaking news and sensational headlines that generally associate drug users with deviant or criminal behaviours to attract public attention. For example, Vietnamese press often mentions drug users as follows:

Robberies are increasing for many reasons, but the dominant purpose is the high number of drug addicts … Many drug users form gangs that get high before going out on the street to rob—Lieutenant General Trieu Van Dat of the Ministry of Public SecurityFootnote8

The ongoing campaign to collect drug addicts into rehabilitation centres in Ho Chi Minh City has helped improve the crime situation in the city remarkably—Senior Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Si QuangFootnote9

Police have warned about increasing cases of people committing crimes under the influence of methamphetamine, especially “ice” (crystal methamphetamine), as the drug trade has grown in recent years—Major General Nguyen Anh Tuan, Director of the Drug-Crime Police Department at the Ministry of Public SecurityFootnote10

Doan Trung Dung, the prime suspect in the killings of a sexagenarian woman and her three grandchildren in Uong Bi City, Quang Ninh, has been arrested … According to the suspect’s initial statements, he admitted the crime, confirming that he was high on ‘crystal meth’Footnote11

To a lesser extent, the same representations are generally not applied for other legal drugs like alcohol or tobacco. Ironically, alcohol and tobacco use have led to many health, social and economic problems in Vietnam, but their use is socially and culturally accepted. According to the Ministry of Health (Citation2016) report, about 80% of Vietnamese males use alcohol and around 37% with females; meantime, about 17% of Vietnamese people have smoked cigarettes. It is often ignored within government discourses that alcohol use results in crime, violence and domestic violence in Vietnam.

5. Discussion

Political and socio-cultural elements have a substantial impact on the perceptions of “evil” drug use in Vietnam and how drug use is politically and socially constructed in Vietnam. Yet the history and contemporary reality of drug use are more complex, and it is essential to move beyond the overly simple axiom that drug use causes addiction, crime and social problems (Nguyen & Scannapieco, Citation2008; Vuong et al., Citation2012b). The use of drugs for recreational, medical and social purposes is recorded throughout human history and only a small number of those who take drugs become chronic dependent users (Hong et al., Citation2011). Under the flexible guidelines combined with specific descriptions, the rest are recreational drug users who do not resort to crime or other anti-social behaviours and seemingly, this fact generally is ignored in Vietnam (Vuong et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). Almost all Vietnamese researchers, the media and government have exaggerated the connection between drug use and crime, addiction and the perils of drug use, and have limited the discussion of the complexity of drug experiences and perpetuated inaccurate stereotypes for political purposes rather than evidence (Vuong et al., Citation2017). Although Vietnam has made great efforts to prevent and warn people from using illicit drugs, the contemporary drug situation has remained complicated both trend and patterns of drug uses alongside with the increasing rate of drug supply from regional sources particularly the Golden Triangle via Laos and also from China (Luong, Citation2019; Vuong et al., Citation2017, Citation2018).

Drug use is still widely perceived as a severe social problem, rather than the public health matter that is depicted in law and strategies. As noted previously, drug use was regarded by Vietnamese authorities as a leftover of old regimes and a form of external contamination from the West and capitalism (Windle, Citation2018). Although the country has opened its economic policy to integrate global market liberalisation, state agencies still conduct nationalistic campaigns in a bid to counter the “poisonous forces” of Western capitalism (Nguyen & Scannapieco, Citation2008; Vuong et al., Citation2012b). Preventing drug use is seen as an essential part of these campaigns. As a result of the HIV epidemic, and the ongoing prevalence of illicit drugs, drug use is also constructed as a social evil with stigmatizing impacts within Vietnam (Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Officials argue that drug use causes the degradation of young people, as it leads to addiction and crime (MOLISA, Citation2015; MPS, Citation2016). As a result, although Vietnam still maintain to send PWUDs in compulsory treatment centres, they still failed to prove the effectiveness and costs of this measure in comparison to apply the voluntary models in community as well as methadone maintenance treatment (Vuong et al., Citation2018).

Under current conditions of the global capitalist economy, the Vietnamese state is less able to secure the economic wellbeing of its citizens. In turn, Vietnam has sought to ensure its standing by emphasising that it can protect citizens from crime or other threats. This approach has contributed to the development of increasingly repressive discourses and practices to those seen as harming society, including drug users whom they are wanting to achieve “normal life” (Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Vietnamese researchers, media and government continually exaggerate the connection between drug use and addiction and crime, as well as the dangers of drug use (Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Vuong et al., Citation2018). Seemingly, aiming to build a “drug-free society”, Vietnam’s ensuing strategies have been ineffective and had limited impacts on drug demand and supply.

Currently, PWUDs suffer from the controversial nature of Vietnamese drug policy, and they have been treated harshly. Drug users are widely perceived as having low levels of education, being unemployed and unemployable, causing anti-social problems, and going against conventional values (Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Vuong et al., Citation2012b, Citation2018). Drug users are also broadly labelled as having deviant or criminal behaviours (Bennett & Holloway, Citation2009), so all drug users are expected to be sent to treatment centres for crime prevention without evidence-based persuading (Vuong et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, much criminal behaviour related to drug use today is a direct result of prohibition; even under prohibition regimes, the vast majority of people with problematic drug use do not commit any crime other than contravening drug laws (Vuong et al., Citation2018). Despite this, Vietnam still stereotypes all drug users as uncertain and potential criminals, and it fails to recognise that most people use drugs recreationally (Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Vuong et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, the failure to acknowledge the complex nature of drug misuse and PWUDs has resulted in misleading perceptions (Luong et al., Citation2019). It is also questioned about the effectiveness of harm reduction in drug policy, which Vietnam considered as one of the three fundamental pillars to drug control in last decade till the present (Vuong et al., Citation2017, Citation2018). Yet, maintaining the compulsory treatment centres is placing sceptical worries about human rights’ accountabilities when the number of protests and escapes of candidates from these rehab’s camps which made Vietnamese authorities more concerned (Windle, Citation2015). Perhaps, this paves the way for making Vietnam be among the most punitive drug control countries worldwide.

6. Conclusion

Since the early 2000s, the perception of drug use and addiction has gradually shifted from a social evil problem to a public health issue, on paper. Step-by-step approaching with harm reduction in drug policies, in 2006, the HIV Prevention Law officially acknowledged that drug use and drug addiction are public health issues and officially recognised harm reduction as one of the priorities to reform the Drug Control Law in 2008. One year later, the 1999 CCV (amendment and supplement) removed the criminalisation of personal possession (article 199), which provided a basis for considering drug use as a public health matter instead of a criminal one. However, in practice, drug use has been seen as an administrative violation in the 2012 Administrative Violation Law—which means that drug users are still cast as a high-risk group. In other words, drug use and PWUDs are primarily seen as social evils rather than a health issue and patients that make a paradox approach in terms of harm reduction in drug control in Vietnam. In the recent meeting of the National Assembly to supplement and amend the Drug Control Law, proposing re-enact the article 199 to criminalize drug use also led to further concerns during shifting harm reduction in Vietnam (Luong, Citation2019). It is still opaque to question about Vietnam’s harm reduction style to deal with PWUDs, which the government believes that reducing harm means preventing illegal drugs and drug misuse and controlling PWUDs (Luong et al., Citation2019). Moving forward on harm reduction in drug policy, Vietnam should need more specific actions with its effective programs to support PWUDs during and post detoxication in voluntary community’s models as well as priorities to deliver methadone maintenance treatment rather than in compulsory treatment centres.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hai Thanh Luong

Dr. Dung Tuan Truong and Dr. Bang Duc Nguyen are senior lecturer at the People’s Police College to focus on criminology and criminal justice in Vietnam, particularly harm reduction in drug policy. Both Dr. Oanh Van Nguyen and Dr. Du Cong Pham are lecturers at the People’s Police Academy to research and teach human trafficking, people smuggling, child sex trafficking, immigration, and police training. Dr. Hai Thanh Luong is a Vietnamese criminologist and visiting scholar at Institute of Research and Development, Duy Tan University and his interests include criminology, criminal justice, and policing.

Notes

1. In fact, both these drug-based plants were also available in the North-west areas, particulalry mountainous provinces shared borderland with China, for many centeries in feuderal regimes and used for both medicinal (opium) and textile (cannabis hemp) purposes. We would like to thank this added point from anonymous reviewer.

2. In the memoirs of Paul Doumer (Citation1903), the five-year governor general in the Indochina (1897–1902), he confessed that his regime encouraged the use of opium and furthermore, tax on opium which eventually raised one-third scale of the revenue needed to govern Indochina, had contributed as one of the most significant profits at that time.

3. Drugs were widely distributed to soldiers to prevent them from falling asleep, to make them lose weight and help them overcome the constant fear of guerrilla attack. Although around 20% of American soldiers became opiate addicts during the Vietnam War, the overwhelming majority desisted from opiate use after they returned home (See Gossop, (2012), Living with drugs (7th ed.). Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, UK: Ashgate).

4. This also means ghosts in the Vietnamese language. Although Vietnamese professionals do not use this meaning to explain the term “Ma Tuy” in official documents, those using illicit drugs (Ma Tuy) are seen as “ghosts” (or remnants of their former selves) by ordinary Vietnamese people.

5. Because the Vietnamese Illicit Drugs Classification, which includes four schedules, is lengthy, we just provide the link to access this classification. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1fx4qFn2MYf9o3FMEm_71_fVTA-5YfQQV/view?usp=sharing

6. Vietnam is heavily influenced by Confucianism, which emphasises the significance of conventional values and personal moralities, so people who use drugs, therefore, have been viewed as weak-willed and morally corrupted individuals or “social evils” (Edington, Citation2016; Hayes-Larson et al., Citation2013).

7. Goldstein (Citation1985) tripartite conceptual framework to explain the drug-crime nexus offered not just one explanation of the drug-crime link, but three: the psychopharmacological, economic compulsive, and systemic violence models. The psychopharmacological model proposes that some people may become excitable, irrational and may have violent behaviour after they consume illicit drugs, such as opiates or cannabis. In other words, the effects of drug use lead to certain types of criminal behaviour like violent crimes. The compulsive economic model suggests that some drug users conduct financial related crime to fund their drug habit. They may commit violent crimes like robbery, or nonviolent crimes such as burglary and/or shoplifting. Meanwhile, the systemic model explains that the world of the illicit drug market is inherently violent. Traffickers, dealers and users do not base their activities on the legal system, so they tend to regulate their affairs by using violence. Nearly 25 years later, both Bennett and Holloway (Citation2009) offered four suggested causal mechanisms, namely drugs cause crime, crime cause drug use, common aetiology (i.e. other factors may cause both), and bidirectional relationship. Accordingly, this relation should be refined to explain each type of crime conducted by drug misuse rather than only focusing on the tripartite framework of Goldstein.

8. Cited in Dinh, P., & Duc, T. (2014). As a crime, drug use rise, addicts run loose in Ho Chi Minh City. Retrieved 17/10/2017, from Thanh Nien News, p. 1

9. Cited in Dinh, P., & Duc, T. (2014). As a crime, drug use rise, addicts run loose in Ho Chi Minh City. Retrieved 17/10/2017, from Thanh Nien News, p.2

10. Cited in TuoitreNews. (2014). Collecting drug users helps improve the crime situation in Vietnam metropolis. Retrieved 21/02/2017, from TuoitreNews, p. 1

11. Ibid. p.3

References

- Bankoff, G., & McCoy, A. W. (2007). The politics of heroin: CIA complicity in the global drug trade. Lawrence Hill Books.

- Bauer, R., Eppler, N., & Wolf, J. (2007). Implications of understandings of addiction: An introductory overview. Bioethics, 7(1), 29–14.

- Bennett, T., & Holloway, K. (2009). The causal connection between drug misuse and crime. British Journal of Criminology, 49(4), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azp014

- Beresford, M. (2008). Doi Moi in review: The challenges of building market socialism in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 38(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472330701822314

- Bradley, M. (2004). Becoming ‘Van Minh’: Civilizational discourse and visions of the self in twentieth-century Vietnam. Journal of World History, 15(1), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1353/jwh.2004.0001

- Buchanan, J., & Young, L. (2000). The war on drugs or a war on drug users? Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 7(4), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/dep.7.4.409.422

- Chan, A., Kerkvliet, B. J., & Unger, J. (1999). Transforming asian socialism: China and Vietnam compared. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Dinh, P., & Duc, T. (2014) As crime, drug use rise, addicts run loose in Ho Chi Minh City. Thanh Nien News.

- Doumer, P. (1903). Indo-Chine Francaise. Vietnam The World’s Publishing and Alpha Books.

- Edington, C. (2016). Drug detention and human rights in post-Doimoi Vietnnam. In J. G. Singh, D. D. Kim, J. G. Singh, & D. D. Kim (Eds.), The postcolonial world (pp. 325-335). London, UK: Routledge.

- Failler, P. (1993) The international anti-opium movement and Indochina, 1906-1940 [PhD Thesis in History]. University of Provence [France language].

- Failler, P. (2000). Opium and colonial governances in Asia: From monopoly to prohibition, 1897-1940. The Cultural Communication Publishing.

- Frey, B. S. (1997). Drugs, economics and policy. Economic Policy, 12(25), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0327.t01-1-00025

- Goldstein, P. (1985). The Drugs/Violence Nexus: A Tripartite Conceptual Framework. Journal of Drug Issues, 15(4), 493–506. doi:10.1177/002204268501500406

- Hayes-Larson, E., Grau, L. E., Khoshnood, K., Barbour, R., Hai Khuat, O. T., & Heimer, R. (2013). Drug users in Hanoi, Vietnam: factors associated with membership in community-based drug user groups. Harm Reduction Journal, 10(33), 1–11. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1477–7517–10–33

- Hong, K. T., Van Anh, N. T., Oanh, K. T. H., et al. (2011) Understanding and challenging stigma toward injecting drug users and HIV in Vietnam. Toolkit for action. Hanoi, Vietnam: Institute for Social Development Studies (ISDS) and InternationalCenter for Research on Women (ICRW).

- Kincaid, H., & Sullivan, J. A. (2010). 13 medical models of addiction. In D. Ross, H. Kimcaid, & D. Superett (Eds.), What is addiction? (pp. 353–376). A Bradford Book.

- Lau, H. V. (1993). Lịch sử phòng chống ma túy ở Việt Nam (English translation: History of drug prevention in Vietnam). Sunday People.

- Luong, T. H. (2019). Time to rethink Vietnam’s drug policies. In Economic, politics and public policy in East Asia and the Pacific. Canberra, Australia: East Asia Forum.

- Luong, T. H., Le, Q. T., Lam, T. D., & Ngo, B. G. (2019). Vietnam’s policing in harm reduction: Has one decade seen changes in drug control? Journal of Community Safety & Well-Being, 4(4), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.35502/jcswb.108

- McCoy, A. W., Read, C. B., & Adams, L. P. (1972). The politics of heroin in Southeast Asia. Harper Colophon Books.

- Menninger, R. W., & Nemiah, J. C. (2008). American psychiatry after World War II (1944-1994). American Psychiatric.

- Ministry of Health. (2016). Hỏi và đáp: Phòng chống tác hại của rượi bia [English translation: Questions and answers: Preventing the danger and harm of alcohol]. Medical Publisher.

- Ministry of Health. (2016b). Report on Prevention HIV/AIDS in 2015 and Main Responses in 2016.

- Ministry of Health. (2018). Báo cáo về đánh giá tác động của chính sách pháp luật trong phòng chống tác bại của rượi, bia và thuốc lá (English translation: Report on evaluating effects of legall frameworks on preventing harm caused by alcohol and tobacco). Hanoi, Vietnam: Ministry of Health.

- MOLISA. (2015). Tổng quan về nghiện ma túy (English translation: An overiew on drug addiction). Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs.

- MPS. (2016). Annual Report for Drug Situation in Vietnam. Hanoi, Vietnam: Ministry of Public Security.

- Nguyen, T., Luong, N., Nham, T., Chauvin, C., Feelemyer, J., Nagot, N., Jarlais, D. D., Le, M. G., & Jauffret-Roustide, M. (2019). Struggling to achieve a ‘Normal Life’: A qualitative study of Vietnamese methadone patients. International Journal of Drug Policy, 68(June), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.026

- Nguyen, T. P. (2002). Giáo trình về phòng chống nghiện ma túy (English translation: Textbook on drug addiction prevention). The People’s Police Academy.

- Nguyen, V., & Scannapieco, M. (2008). Drug abuse in Vietnam: A critical review of the literature and implications for future research. Addiction, 103(4), 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02122.x

- Nguyen, Y. (2001). Prostitution, narcotics, and gambling: Crimes at the present. Vietnam People’s Public Security Housing.

- Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., & Blakemore, C. (2007). Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. The Lancet, 369(9566), 1047–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4

- Pettus, A. (2004). Between sacrifice and desire: National identity and the governing of femininity in Vietnam. Routledge.

- Phinney, H. M. (2008). “Rice is essential but tiresome; you should get some noodles”: oi Moi and the political economy of men’s extramarital sexual relations and marital HIV risk in Hanoi, Vietnam. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 650–660. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2376991/pdf/0980650.pdf

- Quang, N. M. (2009). Buôn lậu ma túy ở Việt Nam trước năm 1975 (English translation: Drug trafficking in Vietnam before 30th April 1975). Giao Hoi La Ma-Vatican.

- Rapin, A.-J., Dao, H. K., & Pham, H. T. (2003). Ethnic minorities, drug use and harm in the highlands of Northern Vietnam: A contextual analysis of the situation in six communes from Son La, Lai Chau, and Lao Cai. Hanoi, Vietnam: UNODC.

- Rydstrøm, H. (2006). Sexual desires and ‘social evils’: Young women in rural Vietnam. Gender, Place & Culture, 13(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690600701053

- Taylor, S. (2008). Outside the outsiders: Media representations of drug use. Probation Journal, 55(4), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550508096493

- UNAIDS. (2016). Do not harm: Health, human rights and people who use drugs. New York: UNAIDS.

- Vietnamese Government. (2014). Vietnam global AIDS response congress report: Following up the 2011 political declaration on HIV/AIDS. Hanoi, Vietnam: Government of Vietnam.

- VTV. (2013). Rice exports in 2012 reached a record. 08/01/201 ed.Vietnam Televison.

- Vu, V. H. (2000). Chứng cứ khoa học cho nâng cao hiệu quả phòng chống tội phạm ma túy [English translation: Scientific evidence for enhancing the effectiveness of preventing and combating drug crimes]. Ministry of Public Security.

- Vu, V. H. (2007). Phòng chống ma túy trận chiến cáp bách của toàn xã hội [English translation: Preventing drugs - A desperate battle of the whole society]. Labour Publisher.

- Vuong, T. (2016). Economic evaluation comparing the cost-effectiveness of center-based compulsory rehabilitation (CCT) and voluntary community-based methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) in Hai Phong City, Vietnam. University of New South Wales.

- Vuong, T., Ali, R., Baldwin, S., & Mills, S. (2012a). Drug policy in Vietnam: A decade of change? International Journal of Drug Policy, 23(4), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.11.005

- Vuong, T., Ali, R., Baldwina, S., et al. (2012b). Drug policy in Vietnam: A decade of change? International Journal of Policy Analysis, 23(4), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.11.005

- Vuong, T., Nguyen, N., Le, G., Shanahan, M., Ali, R., & Ritter, A. (2017). The political and scientific challenges in evaluating compulsory drug treatment centers in Southeast Asia. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-016-0130-1

- Vuong, T., Ritter, A., Shanahan, M., Ali, R., Nguyen, N., Pham, K., Vuong, T. T. A., & Le, G. M. (2018). Outcomes of compulsory detention compared to community-based voluntary methadone maintenance treatment in Vietnam. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 87(April), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.01.011

- Wilcox, W. (2000). In their image: The Vietnamese Communist Party, the” West” and the social evils campaign of 1996. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, 32(4), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2000.10419540

- Windle, J. (2015). A slow march from social evil to harm reduction: Drugs and drug policy in Vietnam. Journal of Drug Policy Analysis, 10(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1515/jdpa-2015-0011

- Windle, J. (2018). Why do South-east Asian states choose to suppress opium? A cross-case comparison. Third World Quarterly, 39(2), 366–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1376582