?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

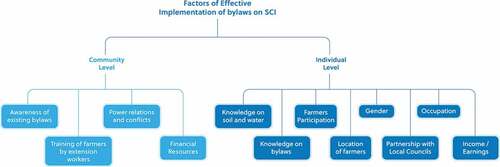

The study examined the factors for the successful implementation of bylaws on sustainable crop intensification. The study used the new institutionalism theory to examine the implementation of bylaws in the potato cropping system in southwestern Uganda. A mixed model featuring both qualitative and quantitative approaches was used in the study. This involved analysis of primary data. The primary sources were key informants, focus group discussions, and face to face interviews with individual farmers, as well as secondary data sources. Factors influencing the effective implementation of bylaws on sustainable crop intensification at community level included awareness of existing bylaws, availability of extension agents to sensitize and train farmers on bylaws, power relations and conflicts among farmers, and availability of financial resources for procurement of agro-inputs. The factors influencing implementation of bylaws on sustainable crop intensification at the individual level included farmers’ knowledge on bylaws (P = 0.03), farmers’ participation in activities organised by government agencies (P = 0.01), the farmers’ village/location (P = 0.03), farmers’ gender (P = 0.001), farmers’ other occupations (P = 0.01), and income earnings (P = 0.02), support of local councils and technical persons to implement bylaws (P = 0.01), and knowledge on soil and water conservation laws (P = 0.03). Thus, there is need to protect land rights (regardless of gender), create awareness on best practices and bylaws among farmers, and mobilize resources to strengthen formal and informal farmer groups to enhance sustainable crop intensification and economic development of the potato sector.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Polices have been found to be good on paper but their implementation is often non-effective. The study focused on establishing the factors that imped the implementation of bylaws on sustainable potato intensification in southwestern Uganda. The findings revealed the key factors responsible for effective implementation of bylaws. The community-level factors included awareness of existing bylaws, availability of technical persons to sensitize and train farmers, power relations and conflicts, and availability of financial resources. The individual-level factors included the farmers’ knowledge on bylaws, participation in activities organised by government agencies, location, gender, other occupation, income earnings, partnerships with local councils and technical persons to implement bylaws, and knowledge on soil and water conservation bylaws. The farmer’s awareness of existing bylaws, mobilizing resources to strengthen formal and informal farmer groups, and developing mechanisms for addressing gender issues that constrain potato production and productivity to ensure economic development of the sector is recommended.

1. Introduction

There is a growing concern about low agricultural production and productivity, which has remained a major development challenge in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) (Godfray, Citation2015; Vanlauwe et al., Citation2014). This is partly attributed to the little attention on the policy component that promotes agricultural sustainability and investment (Brookfield, Citation2001; Yami & Asten, Citation2017). The interest of governments and development partners in agriculture as a development agenda increased with the need to improve food security, nutrition, and incomes of farmers in SSA (Yami & Asten, Citation2017). This was exemplified by prevailing commitments to increase investment in agriculture, such as the formation Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Programme (CAADP) in 2003, when African Heads of State committed at least 10% of their budgets to increase agricultural production (African Union (AU), Citation2003; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Citation2016).

In the past, the primary solution to food shortages was to increase land and water supply in agriculture (Pretty, Citation2008). However, with the rampant land scarcity and increased population growth, there was much need for sustainable crop intensification (SCI) in agriculture (Otsuka & Place, Citation2014). Consequently, SCI was recognized as a means to increase crop productivity and improve rural livelihoods by governments and development partners in SSA and a strategy for increasing the use and efficiencies of agricultural inputs to increase crop production while maintaining integrity of the environment (Chartres & Noble, Citation2015; Royal Society, Citation2009; Vanlauwe et al., Citation2014).

SCI entails increasing production of available farmland while minimizing the pressure on soil without jeopardizing production capacities in the future (Vanlauwe,, Citation2014). SCI embraced abroad range of practices and contexts, including adherence to agroecological principles, as well as application of “new” or improved technologies and management practices (Baulcombe et al., Citation2009; Foresight, Citation2011). Accordingly, this paper considered the following SCI interventions; 1) improved and quality seed, 2) soil and water conservation, and 3) access to market by farmers in potato cropping system, as predictors for sector growth and development. A successful potato cropping system ensured increased income and livelihoods improvements among communities in potato growing area of southwestern Uganda. Potatoes indeed serve as important cash crops and means of livelihoods for people in the region.

Bylaws constituted local laws and customs of villages, towns, cities, or lower-level local government council that provided local guidelines for implementing sectorial policies and rectifying their inefficiencies (Alinon & Kalinganire., Citation2008; Sanginga et al., Citation2009). Indeed, certain formal and informal bylaws were developed to operationalize macro-level policies. These included bylaws on improved and quality seed; soil and water conservation; and market access in the potato cropping system. Nonetheless, the implementation of these bylaws on SCI was affected by several factors (Campenhout, Citation2016; Nkonya et al., Citation2008). Potato (Solanum tuberosum) production presented a good case in point, as Uganda was ranked as the third greatest producer of potato in the East and Central African Region (FAOSTAT, Citation2014). Nonetheless, productivity remained as low as 7 tons per hectare (7 t/ha) of potato crop (FAO Stats, Citation2014). Myriad of factors explained the low production challenge, including but not limited to disease and pests, low-quality seed, low soil fertility, poor management practices, increased post-harvest losses, and lack of local policies (ASARECA, Citation2005).

In Uganda, development programmes, such as livestock services project (LSP), Plan for Modernization of Agriculture (PMA), Poverty Eradication Action Plan (PEAP) National Agriculture Advisory Services (NAADS), Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF), Prosperity for All, Operation Wealth Creation (OWC), and the 4-acre plan focused on improving agricultural production and productivity. However, most of the agricultural policies were not fully implemented to realize the expected agricultural growth (Campenhout, Citation2016; Nkonya et al., Citation2008). They focused on aggregated national level context and specific conditions, and less at the local level where farmers operated. At local level, bylaws are formulated to address constraints to increased agricultural productivity. However, the bylaws were often characterized with low level of implementation. This prompted the need to address bottlenecks to SCI interventions by creating an enabling environment, which eased actions against low crop productivity.

Bylaws are important for SCI as they constitute power negotiation between decentralized bodies and traditional institutions for example, between the local councils and local farmer groups, cultural institutions (Alinon & Kalinganire., Citation2008). In addition, bylaws have the potential to reduce transaction costs by providing measures for reduced costs in institutional monitoring, enforcement of appropriators, and sanctioning of violators (Colding & Folke, Citation2001). In spite of the benefits of bylaws in supporting SCI, the factors that affected their implementation were little known.

The study postulated that bylaws implementation was affected by several factors both at individual and community level. A clear understanding of the factors that influenced effective implementation of bylaws was necessary to foster prioritization of interventions, enhancement of SCI, improvement of livelihoods, and attainment of food security and sustainable development of the region. The study aims to assess the extent of participation among farmers and to determine ways to strengthen it, which ensured high productivity, marketability, and sustainable livelihoods in the region. The study examines the role of demographic factors, such as age, gender, level of education, occupation, alternative sources of income, and access to information, or knowledge helped the study to understand challenges that undermined SCI and focused on the human capital challenges and transformational actions to boost production and productivity of the potato cropping system.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the conceptual framework discussing the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of the study. Next, is the methodology section with the study approach, data collection, and analysis. Then, sections on the findings and discussion follow. Finally, the conclusion and recommendations section presents the actions required based on the findings and key recommendations.

2. Conceptual framework

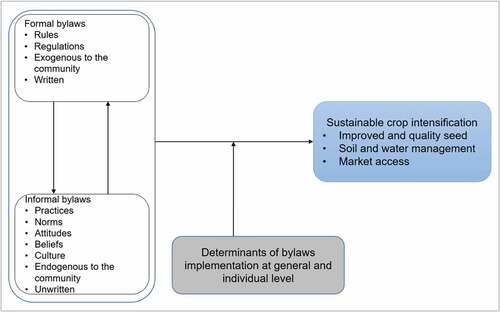

The new institutionalism theory states that bylaws are normative reference framework and behavior rules to guide, constrain, and create power within the potato farmer communities (North, Citation1990). The new institutionalism theory highlights the importance of formal rules and regulations, as well as informal rules, taboos, and norms for guiding human behavior and governing interactions among users, with the aim of achieving common goals in natural resources management (Figure ).

The new institutionalism is based on the principle that, all the results of the human actions are explained by the individual actor’s action whose interactions in the structures, legitimatize the institutions (Vargas-Hernández, Citation2008). Indeed this normally influences individuals in function of their actions. The new institutionalism emphasized the institutions that define the behavior of the actors. According to the new institutionalism theory, the role of states and governments in providing necessary governance structures is emphasized. It further argues for the role of the local governments to exercise its function without blocking its work and to protect it from other people’s inherencies. This theory informed and guided the study focusing on both formal and informal bylaws as there is increased interest in understanding the factors that influenced implementation of bylaws, awareness, and compliance (Kayambazinthu et al., Citation2003; Nkonya et al., Citation2008; Struika et al., Citation2014).

Sustainable crop intensification (SCI) is a process or system, where agricultural yields increase without adverse environmental impact and conversion of additional non-agricultural land (Pretty & Bharucha, Citation2014). SCI was first implemented in the green revolution. The green revolution resulted in increased economic growth, improved rural livelihoods, and conserved fragile ecosystems from adverse effects of extensive farming (Xie et al., Citation2019). It contributed to the general reduction of poverty, hunger and avoided the conversion of thousands of hectares of land into agricultural cultivation.

However, the economic boom caused by the green revolution had a negative impact on the environment and natural resources. This was a result often not because of the technology itself but rather, because of the policies that were used to promote rapid intensification of agricultural systems and increase food supplies (Pingali, Citation2012). Drawing from the lessons learned, a second green revolution is envisaged integrating environmental and social safeguards combined with agricultural and economic development. As a consequence, SCI was fronted and positioned as a key pathway to address those challenges. SCI innovations, practices, and technologies are aimed at enhancing production, productivity and resilience of agricultural production systems; and, at the same time, conserve and protect the natural resource base (Kassie et al., Citation2014; Vanlauwe et al., Citation2014).

As such, there was a nexus between SCI and bylaws. Implementation of bylaws that dealt with the challenges of SCI interventions and low crop productivity is important. Moreover, it was paramount to target interventions and support to farmers that enhanced productivity and improved livelihoods. This necessitated unraveling of the factors that impended bylaws from being implemented among farming communities in the southwestern Uganda region in order for them to gain from the economic potential of the sector.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study area

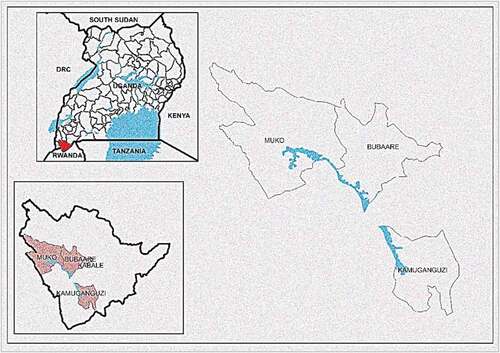

The study was conducted in southwestern Uganda, in the districts of Kabale and Rubanda (Figure ). The study area was characterized as mountainous, with relatively fertile soils and favorable weather for potato production. The montane cropping system supported a high population (UBOS, Citation2017). Three sub-counties, including Muko and Bubare in Rubanda district and Kamuganguzi in Kabale district were selected for study. The sites were selected based on a recently implemented project on Policy Action for Sustainable Intensification of Ugandan Cropping Systems (PASIC), which indicated that they had high potential for crop intensification, and shaping of behavior by formal and informal bylaws in the potato cropping system (Yami & Asten, Citation2018). This explained why potato growing was main occupation and source of livelihoods for the people in the region. In that respect, the study sites provided interesting cases for analyzing factors influencing bylaws implementation and SCI.

3.2. Procedure of sampling

A three multi-stage sampling procedure was used in the study. This involved the use of both purposeful and random sampling procedures to draw a representative sample of the potato farmers. Respondents were selected based on their firsthand experience and knowledge of the institutional contexts influencing the potato cropping systems. The initial stage involved the selection of the two districts; Kabale and Rubanda. They were purposively selected based on existence of bylaws on SCI, drawn from a preliminary reconnaissance and previous studies (Nkonya et al., Citation2008; Sanginga et al., Citation2009). Besides, they were perennially potato producing areas renowned for land degradation and breadth of interventions by development partners to overcome it, such as PASIC. The second step involved purposive selection of three sub-counties that showed strong indicators of improved and quality seed bylaws: (i) Kamuganguzi sub-county (soil and water conservation, and improved and quality seed bylaws); Muko sub-county (soil and water conservation and quality and improved seed bylaws), and (iii) Bubare sub-county (market access and quality and improved seed bylaws). The third and final step was conducting the simple random sampling of potato farmers from the selected sub-counties. This gave each farmer an equal chance of being selected to participate in the study. The lists of names of potato farmers were obtained from each of the selected sub-county offices to facilitate completion of this final stage. One hundred and four (104) farmers in total were randomly selected from the three sub-counties to participate in the study.

The research was registered, peer-reviewed, and approved by the National Research and Ethics Committee at the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). Individual consent was secured from participants before administration of study tools.

3.3. Tools and methods of data collection and sources

A semi-structured questionnaire was used to conduct face-to-face interviews. 104 randomly selected potato farmers/. This method allowed in-depth examination of the subject and relived experiences of researchers. Sufficient time was allocated during the interviews to prove and exhaust questions to gain deeper meaning about questions asked. The use of semi-structured questionnaires was adopted because it proved effective in minimizing bias and random error from occurring (Fowler, Citation2001). Furthermore, the semi-structured questionnaire were used to explore initial study themes and probe deeper into the factors affecting bylaws implementation by the potato farmers The data collected involved compiling existing bylaws on sustainable potato intensification, knowledge on existing bylaws, implementation of existing bylaws, potato farmer-specific characteristics, like age and level of education, gender, institutional factors such as access to financial resources and farm characteristics, including land size and management, major crops grown and innovations adopted on sustainable crop intensification.

Key informant (KIs) interviews were conducted to gather expert opinion on factors facilitating/impeding the implementation of bylaws on SCI. The KIs consisted of government employees (9), employees of NGO (3), staff national agricultural research organization (2), and employees working with either farmer groups or associations in various capacities (8). They were selected based on their knowledge of potato production and existing bylaws. The key informants were interviewed using semi-structured questionnaires with open and closed-ended questions to understand factors affecting implementation of formal and informal bylaws relevant to SCI. They were flexible enough to cause clarity and consistently reciprocate responses while maintaining the scope of the study.

This was followed by six FGDs, using a checklist to collect data on the respondents’ views on facilitating and impeding factors for implementation of formal and informal bylaws. The FGDs were composed of potato farmers knowledgeable on potato production and ranged between six and eight per FGD. Two FGDs were organized in each of the three sub-counties of Kamuganguzi, Bubabare and Muko.

The total number of participants in the focus group discussion were 58 (32 Males and 26 Females). The key informants were disaggregated as follows: Seven were males and 15 females.

3.4. Data analysis techniques

The data were analyzed and led to generation of descriptive statistics. An empirical model was used to analyze factors influencing bylaw implementation on SCI. The data were coded, entered in Epidata version 3.1 package, and exported to Stata version 13.0 for analysis.

3.4.1. The model equation—multiple linear regression

Multiple linear regression was used to determine strength of relationship between the independent variable and dependent variables under study. This model was most favored because it measured levels of significance between more than two or more variables. For example, there were two sets of variables; causal factors and a single effect variable (Alexandrowicz et al., Citation2016). In this study, the levels of implementation of seed quality, soil, and water conservation and market access practices as the outcome (Y) in sustainable crop intensification were measured by scoring each of the existing bylaws on seed quality, soil, and water conservation and market access, and then summing them all total implementation (Y) which was linear a continuous variable in nature. Thus, multiple linear regression was most appropriate statistical model in understanding the strength of relationship between more than two variables against a single variable in this study (Bremer, Citation2012). This was represented by linear model equation shown below:

Where:

Y (dependent) is the total resultant implementation owing to changes in variables/factors: X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6 to the ith factor as determined by the fitness of the model with their respective linear regression coefficients β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, β6 to βi and βo as the intercept.

X1 to xi is the independent variables

Β0 is the intercept, the value of Y when X1 to xi are zero.

e is the error term

3.4.2. Scoring the independent and the dependent variables

3.4.2.1. Independent variable

The independent variables, particularly farmer’s knowledge on by-laws on seed quality; knowledge on by-laws on soil and water conservation; and knowledge on by-laws on market access, where knowledge on each of the assessed bylaws was scored as 1, and failure to acknowledge the assessed bylaw as 0.

Farmer’s knowledge on seed quality bylaws was examined using 28 bylaws including “not growing on the same plot season after”, “cutting off-shoots when the potatoes have matured to allow them harden”, “not harvesting potatoes in rain”, “preparing land well before planting”, “spraying pesticides”, “harvesting only mature potatoes”, “putting potatoes on stalls for hardening”, “potato seeds should not peel off”, “potato seeds should have germinated”, “seeds gardens should be inspected and certified if they qualify”, “only disease-free seeds should be planted”, “seeds should be from valid sources”, “potato seed gardens should be separated”, “digging trenches”, “not mixing seed varieties on the same plot”, “seeds should be sprinkled with pesticides”, “farmers should use fertiliser on seeds”, “seeds should be planted on flat uphill”, “planting right size seeds”, “weeding for seeds should be done in time”, “only clean or disinfected equipment should be used”, “seeds should be planted in lines”, “standard spacing during planting of seeds”, “weed of seeds should not be done in rain”, “farmers should do Fanyachini”, “not spraying in rain”, “not spraying and weeding at same time”, and “not planting when raining”

Knowledge on soil water bylaws, included knowledge on 16 by-laws, including “digging trenches”, “digging channels in valleys”, “planting Irish in lines”, “not grazing in other people’s gardens”, “no planting eucalyptus in potato gardens”, “digging Fanyachini”, “digging FanyaJuu”, “carrying on bush fallowing on plots for potato growing”, “addition of manure in gardens”, “use of fertiliser”, “separate gardens”, “planting of reeds”, “planting elephant grass”, “terracing”, “ digging ditches on top hills”, and carrying out crop rotation.

Knowledge on by-laws on market access included knowledge on 14 bylaws including “selling only mature potatoes”, “proper packaging potatoes”, “ensure good quality potatoes”, “cutting off the stalks”, “levying penalties to thieves”, “having collection stores”, “selling in bulk”, “sorting potatoes in grades before sell”, “standardizing price”, “collective purchase of inputs”, “proper storage of potatoes”, “keeping farm records”,’ drivers of trucks for potatoes should have permits’, and traders should have licenses’.

Overall knowledge on by-laws on soil-water conservation, seed quality, and market access involved summing up all scores on the three categories of bylaws, leading to 58 total scores.

3.4.2.2. Dependent variable: implementation of the bylaws

The implementation of bylaws was assessed by scoring each of the by-law known to exist on soil and water conservation, seed quality, and market access. Each bylaw implemented was scored 1 and 0 for any by-law not implemented. Thus, a maximum of 58 points and 0 as minimum was expected.

3.4.2.3. Testing for normality and analysis process

The dependent variable (total scores on implementation of bylaws) was tested for normality, using histogram with a distribution curve and shapiro wilk test, which indicated that data were normally distributed p-value-0.3). Linear regression was used for analysis with total scores on implementation as the dependent variable. It allowed researchers to measure extent of which changes on the x-axis caused changes on the y-axis. The variables with p-value = or less than 0.2 at bivariate analysis were considered for multivariate analysis and model fitting. Multicollinearity was tested and one of the paired variables with a correlation coefficient of 0.4 or more was eliminated, basing on literature concerning those variables to be retained. The adjusted R-squared value was used for evaluating the fitness of the model. The model with the highest adjusted R-squared value was considered the most fitting (38.4%).

3.4.2.4. Analysis of key informant interviews and focus group discussions

The primary data from the focus group discussions (FDGs) and key informant (KI) interviews were transcribed. Translations were done using English language to enable analysis for interviews that researchers conducted in local dialect (Rukiga). The transcripts were well-edited before analysis. In total, six FDGs and nine key informant interview transcripts were analyzed using a master sheet analysis technique. Each transcript was repeatedly read at ago and emerging issues from them coded. This method facilitated keeping of records of original data for review and direct quotation to emphasise the findings presented and interpreted. Categories and deductive coding were developed and used for analysis, based on the themes that emerged from each transcript by reading and determining meaning for each sentence (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). Lastly, the retrieval and interpretation of data were done by including data from observations recorded in the field.

The summary of respondents (individual potato farmers) is shown in Table .

Table 1. Characteristics of the individual farmer interview respondents, N = 104

4. Findings

4.1. Individual farmer factors influencing bylaws implementation

At the bivariate level, farmer’s knowledge on soil and water bylaws, and farmer’s participation in activities organized by Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry, and Fisheries (MAAIF) was associated with the implementation of formal and informal bylaws (Table ). The changes in knowledge of soil and water influenced the implementation of bylaws.

Table 2. Factors of implementation of bylaws

In Table , farmer’s education, age, ownership of land, occupation, land acreage under cultivation, gender, farmer’s location in terms of district and sub-county, marital status, religion, farmer’s knowledge on market access bylaws, knowledge on improved and quality seed bylaws, realization of benefits from implementing bylaws, financial sources, like SACCOs, from savings or loans from traders for implementing bylaws, farmer’s participation in attending meetings, implementing what was learnt from agriculture training or sensitizations, or linking with farmer groups, local councils, National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS), Local governments, or with agricultural institutions, like NARO, IIT, KARDI, when implementing the bylaws were not associated with implementation of formal and informal bylaws at bivariate level.

At multivariate level (Table ), the final model predicted 37.7% (Adjusted R-Squared = .0377) for bylaw implementation. Indeed, the model used had an R—squared (0.5374). This implied that the model was such fitting with 53% variance in the independent variable.

Table 3. Multivariate level analysis of factors influencing bylaws implementation

The factors significantly associated with bylaw implementation included (i) farmer’s village, particularly residing in: Murukoro (β = 3.13, p value = 0.03, 95% C1, 0.08; 6.17), Kateete (β = −23.17, p value = 0.03, 95% C1, −31.14; −15.19), and in Muko hill (β = 7.79, p value = 0.02, 95% C1, 1.49; 14.09); (i) farmers’ gender (β = −3.13, p value = 0.001, 95% C1, −4.90; −1.37); (iii) farmers’ other occupation, particularly being a business person (β = −2.79, p-value = 0.01, 95% C1, −4.95; −0.64), and income earners (β = −3.57, p value = 0.02, 95% C1, −6.57; −0.57); (iv) linking with local councils in implementing the bylaws (β = 2.93, p value = 0.01, 95% C1, 0.69; 5.17), and (v) having knowledge on soil and water conservation laws (β = 1.56, p value = 0.03, 95% C1, 0.14; 2.99).

The average difference in implementation of bylaws was 2.13 (3.13–1.00), higher among farmers residing in Murukoro village, compared to farmers in Nyambyumba village (reference category) while maintaining that of farmers’ gender. The farmers’ major occupation, farmer’s linking fellow farmers, when implementing bylaws, the linkage between farmers and local council, and development of farmer’s knowledge on soil and water conservation bylaws were constant. On the other hand, the average difference in implementation of bylaws was 24.17 (−23.17–1.00) bylaws, less among farmers residing in Kateete village, compared to farmers residing in Nyambyumba village (reference category), while controlling factors, such as farmer’s gender, farmer’s major occupation, farmer’s linking fellow farmers when implementing the bylaws, farmer’s linking with the local council and farmer’s knowledge on soil and water conservation bylaws.

Likewise, female farmers were 4.13 (−3.13–1.00) less on average in bylaws implementation compared to the male farmers, controlling factors, such as farmer’s village, farmer’s major occupation, farmer’s linking fellow farmers, when implementing the bylaws, farmer’s linking with the local council and farmer’s knowledge on soil and water conservation bylaws. Farmers who were business people, engaged in small trade were less by 1.79 bylaws on average in implementation compared farmers, who had no other occupation, controlling factors, like farmer’s village, farmer’s gender, farmer’s linking with fellow farmers when implementing the bylaws, farmer’s link with the local council, and farmer’s knowledge on soil and water conservation bylaws. Similarly, farmers who linked with fellow farmers when implementing bylaws were 3 (−2.01–1.00) bylaws lower on average in implementation compared farmers who did not associate with fellow farmers when implementing bylaws controlling for farmer’s village, farmer’s gender, farmer’s other occupation, farmer’s linking with the local council and farmer’s knowledge on soil and water conservation bylaws.

Indeed, the model used had an R—squared (0.5374) and adjusted R (0.3771). This implied that the model was such fitting with 53% variance in the independent variable (SCI implementation).

4.2. General perception of factors influencing implementing bylaws on SCI

The analysis of the factors influencing the implementation of bylaws relevant to SCI generated five main categories. These categories included awareness on existing bylaws on sustainable potato intensification, availability of extension agents to sensitize and train farmers on bylaws, power relations, and conflicts, and lack of financial resources to support the implementation of the local bylaws.

4.2.1. Awareness of existing bylaws on sustainable potato intensification

The study revealed that formal bylaws were easy to implement, as communities knew the benefits of bylaw implementation and implications of failing to abide by them, including being prosecuted. Institutions, for example; Challenge Programme (CP), International Fertiliser Development Center (IFDC), Africa 2000 Network (A2N), Integrated Seed Sector Development Programme in Uganda (ISSD Uganda), and Kachwekano Zonal Research and Development Institute (KAZARDI) were involved in sensitizing farmers on bylaws and best farming practices. Sensitization of people was made possible through community meetings, radios on talk shows, print media adverts, and video clips. Talk shows or adverts and video clips were conducted in the early morning before children and mothers went to school and gardens, respectively. Evening sessions, often around 8pm were most conducive at that time the farmers would have retired to their homes. For instance, after formulation of bylaws on natural resource management, agriculture, and marketing bylaws, community members highly complied by digging trenches to rehabilitate degraded water shades of Kagera Tamp Project in Bubare sub-county. Women had limited say over natural resources and influence in formulation of bylaws, which undermined commitment and ownership of the laws, as well as SCI. The natural resource management, and agriculture and marketing bylaws were also used in Kyokyezo, Nyamweru sub-county mobilizing communities’ members to lands slides, flooding and soil erosion.

After the natural resource management, agriculture and marketing bylaws were developed, the CP helped in sensitizing people about bylaws. This helped people to properly understand bylaws and implications of failing to follow them. The informed communities went to the district to get photocopies of the bylaws for more clarification. Some of the existing NGOs provided training and created awareness to and among the farmers. The most driving factor and motivation to them were benefits of implementing bylaws. The local governments also played a key role in creating awareness on the bylaws. Local governments ensured custody of all the bylaws enacted by the farmers, often helped to replace those misplaced by the farmers.

If you are at the border and you look at Rwanda you see a different landscape yet it’s almost the same bigger water shade and when you ask that why is that place is better than Uganda, people will tell you that’s Rwanda; they follow laws. If there is an instruction everyone has to comply. I think we need a lot of training and sensitization of the communities to change mindset (Former coordinator of the Challenge programme, Kabale district Local government, interview conducted in March 2018).

4.2.2. Collaboration and good information sharing between the actors

Local and international NGOs played a key in linking the local potato actors together. For example, IFDC and ISSD Uganda worked closely on providing quality seeds. IFDC was oriented towards producing and providing fertilizers. ISSD Uganda, with expertise on seed quality, supported them. More still, IFDC collaborated with IITA, through the Policy Action for Sustainable Intensification of Ugandan cropping systems (PASIC) project, under IITA on bylaws and in research activities. The local actors collaborated on implementing bylaws. For example, under the IFDC-REACH Uganda Project (Making Markets Work for the Poor), the local actors collaborated with other development agencies on the Climate Smart Agriculture related activities, where IITA conducted mostly research. So, their roles were mutually reinforcing.

4.2.3. Availability of technical people to sensitise and train farmers on bylaws

Availability of technical persons to train farmers and foster bylaws implementation. The study found that, during training, people in the implementing organizations, like IFDC, ISSD, NARO, and KAZARDI, at both district and sub-county worked closely with farmers. For instance, IFDC, through the IFDC-REACH Uganda project offered mentoring and technical backstopping to implementing partners, especially farmer groups and farmer associations. Thus, technical persons were in a better position to sensitize farmers about better farming practices.

We have been with several implementing partners as frontline because we are very few staff and our major role is to do the mentoring, technical backstopping and follow up on activities in the region. We collaborate with other projects working in the region and our sister project with whom we receive funds from the same source (IFDC Southwestern Uganda, March 2018).

4.2.4. Power relations and conflicts

The personalities of local leaders influenced implementation of bylaws. It was revealed that the police, sub-county and district leaders as well as courts of laws in the district were instrumental in implementing and enforcing, particularly formal bylaws. For instance, follow-up of district ordinances were mainly done by the district department, from which they (ordinances) originated. Like other ordinances or bylaws and other decrees, the implementation of bylaws on sustainable potato sustainable intensification depended on the vigilance of the leader in that area, either at village, parish, sub-county or district level. However, it was noted that use of force in implementing the bylaws was not fruitful as community members often decided to resist the bylaws.

I think it depends on the vigilance of the sub-county leader. If the chief executive officer or Chairperson LCV said this month is a sanitation month, therefore, this ordinance applies everywhere it would work. It depends on how someone is vigilant especially the leaders (Former coordinator of the Challenge programme, Kabale District Local Government, March 2018).

4.2.5. The deterrent influence of politicians does affect bylaws implementation

Notwithstanding the efforts of the technical teams at districts, sub-county and lower councils, numerous programs were planned. Many politicians interfered with or interrupted the technical people from implementing or enforcing them. The politicians left people to do whatever they wanted, hoping for political votes in future. One of the key informants had this to say:

With the introduction of Local council, powers went too indirectly; not officially to local councils, to the politicians at different levels. It became difficult for the sub-parish and sub-county chiefs to enforce the bylaws. The politicians because they are voted for would say “do not touch my people” “do not touch my people” (Regional coordinator, IFDC southwestern Uganda, March 2018).

But what we found out is the lack of commitment of the drivers or would-be drivers of these initiatives. By drivers, I mean like the local leaders at LCI, LCII, and LCIII. There is a bug which has eaten up people in Uganda and that is being cheap especially dealing with politics whereby if someone is being hard on people, he fears that he may not be voted again. That is coming from up to down and in that way, bylaws fail to be implemented (Regional coordinator, Africa 2000 Network, April 2017).

The informants highlighted that, in the past, bylaws were implemented by the agricultural extension workers, parish chiefs (Muluka), sub-parish chiefs (Mutongole) and Sub-county chiefs (Gombolola). These were not politicians but technical persons. During that time, implementation was by “carrot and stick”. By “carrot”, concerned people were convinced, reinforced by some incentives from the government. And by “stick”, the technical people used coercion method to implement bylaws, when farmers refused to follow them. This motivated farmers to implement the bylaws, especially on land use management, crop management, pests, and disease management in the cash crops. The manipulation of existing courts of law, through appealing to higher magistrates affected the implementation of bylaws. For instance, it was observed that some learned individuals refused to abide by the local council or community courts and, instead, appealed to higher courts. Eventually, the courts acquitted them since informal bylaws were not gazetted and, thus, not recognized by the courts.

4.2.6. Lack of financial resources to support implementation of local bylaws

A small number of farmers, especially those who were market-oriented usually secured loans from banks or microfinance institution to finance their agricultural activities. Some of them even wrote business plans as a prerequisite for requesting agricultural loans.

It is only these market-oriented farmers who access these loans. So they even write business plans which they present to the banks or financial institutions so for them they are a bit ahead of the others. So for them, they go when they are very ready for any type of question that can be asked by the person going to lend them money (Regional coordinator, Africa 2000 Network, March 2018).

5. Discussions

This study postulated that bylaws implementation influenced SCI and implementation of such bylaws was affected by individual and community level factors. The researchers substantiated findings by using other methods and sources, for example, by asking other key informants to reflect on findings.

The study revealed that awareness of bylaws enhanced implementation of existing bylaws on sustainable potato intensification and various actors (research, NGOs, and local governments) were involved in enhancing awareness of bylaws. It helped farmers to properly understand the bylaws under the new institutionalism framework and the implications of failing to follow them, encouraged gender inclusivity and equity in formulation and implementation of bylaws, and increased awareness about existing bylaws and promoted institutionalism. This was translated into effective bylaw implementation, improved livelihoods, and economic growth and development of sector.

The findings underscored the importance of collective engagement of various actors, awareness raising, and information sharing was paramount during the implementation of bylaws. Similar findings were observed by Nkonya et al. (Citation2008), whose results showed that greater awareness of regulations contributed to more sustainable natural resources management. Again, awareness building was a prerequisite to creating demand for extension services (Klerkx & Jansen, Citation2010). Additionally, by the very nature of the area; characterized by steep terrain since colonial times, bylaws on terracing and digging trenches existed. No wonder, knowledge on existing bylaws enhanced their implementation overtime, compared to more recent bylaws on improved and quality seed and market access. Farmers were trained by technical persons from the districts, NGOs, research institutions fostered bylaws implementation, through knowledge generation, transfer, and utilization. This strengthened collective response to emerging agricultural challenges, change processes, and efforts to increase productivity, and economic growth and development of the sector. Therefore, new institutionalism theory was effective way to cause social change and socioeconomic transformation of the region and sector. The direct working relations with the presence of extension services and the need of multiple stakeholders in supporting farmers to implement bylaws existed. In addition, varied stakeholders brought on board various value addition processes, including knowledge, infrastructure, and resources.

5.1. Competing interests among the policy actors which constrains policy implementation

These competing interests emanated from each of the actors trying to claim legitimacy and control over the local constituents. The politician wanted to exercise power by claiming to be the legitimately elected representatives of the majority while the technical staff claimed being knowledgeable in the field of promoting sustainable potato intensification, even when they were not elected representatives in the communities. This undermined the spirit and theory of new institutionalism, which in a long run curtailed sustainable intensification of potato growing and economic growth of the region. Mostly, it was the cooperation of such actors that might have reduced politically motivated resistance against the bylaws and facilitated effective bylaw implementation to improve sector performance and contribution to national economy. This harmonization was necessary for development of the potato-growing sector and steady economic development of the region and country in general.

5.2. Power relations and conflicts effect on bylaws implementation

Power relations led to compromise, by allowing interests of the powerful actors to influence policy processes while sidelining the less powerful. Therefore, it was important to address the negative influence of power relations among stakeholders on bylaws implementation to promote SCI. In study by Arts and Van Tatenhove (Citation2004), similar observations were made, where different stakeholders struggled for specific yet competing individual outcomes in policy-making processes, where one benefited and another lost. This phenomenon put the very idea of achieving common goals in the implementation of bylaws at risk. A study by Vorley et al. (Citation2012) confirmed that such bias against less powerful stakeholders in the policy-making processes undermined provision of infrastructure and agricultural extension services to small-scale farmers in a negative manner. It demonstrated dysfunctionality of new institutionalism theory in the potato farming region for failing to ensure inclusive development in institutionalization and potato production processes, without which conflict was eminent. Ultimately, this undermined potato production. Therefore, streamlining bylaw implementation across social classes without discrimination was critical in fulfillment of development plans, where both classes benefited and thrived was most effective in implementation of bylaws.

Likewise, less powerful farmers did not benefit from the implementation of the bylaws in situations of bad governance in government institutions. Hence, it was an excellent development decision to institute mechanisms that provided less influential stakeholders more power to negotiate inclusion of their interests and priorities in bylaws implementation processes to address the dominance of powerful farmers. In a study by Mohammed (Citation2013), similar findings were observed in policymaking processes that favored interests of elites, amidst the disorganized and marginalized interests of rural communities were ignored. This was against the theoretical elements of new institutionalism and undermined prospects of sustainable intensification of potato crop growing and economic potential of the region. Therefore, efforts towards realization of aggregate aspects of new institutionalism theory, as precursor for sustainable potato crop intensification, improved livelihoods and promoted sustainable development of the region were limited and, henceforth, necessary at this point.

Conflict emerged as an important factor in implementation of bylaws for SCI. It was linked to power relations between the elites and farmers. The study found that the elites disrespected existing informal bylaws and setup of courts, preferring to take matters to formal courts, where they bribed their way out. This undermined general efforts towards implementation of bylaws. It was another demonstration for failed new intuitionalism theory, where benefits associated with it, like high production and sustainable intensification of potato cropping and improved livelihoods, too, remained a dream. Yet, the effectiveness of bylaws implementation provided a clear mechanism for enforcing the agreed-upon positions by community and implementers, with the help of incentives provided as rewards to farmers for abiding by the bylaws. These conflicts lay at the heart of the effectiveness of the bylaw, where they undermined implementation and fostered impunity. However, harmonization of relations among stakeholders was always reassuring that a moment for high yields, quality cropping, improved livelihoods, reduced inequalities, and sustainable development of the region would always be reached. Under such circumstances, it was easier to preserve peace in the region and prevent conflict of any form.

5.3. Financial resources were key and prerequisite in the implementation of the local bylaws

In this case, financial resources enabled access to financial services, particularly savings and credit products. These expanded opportunities for more efficient technology adoption and implementation of bylaws. Similarly, in a study report presented by FAO (Citation2013) on review of food and agricultural policies in Uganda, financial constraints were more pervasive in agriculture and related activities than in many other sectors, reflecting both the nature of the agricultural activity and the average size of firms. This demonstrated the need for innovations in financial resources mobilization, such that smallholder farmers on a ladder of ascending financial market access complemented financial services with other sources of income. The integration of demographic dividends into harnessing region’s resource base for economic objectives was crucial at this point. This concretized the theory of new institutionalism and superior advantages associated with it, like sustainable intensification of potato cropping, improved livelihoods, economic growth and sustainable development. However, it should be noted that adequate resources were no guarantee for a policy to be implemented. Therefore, training of farmers was paramount in ensuring effective implementation of bylaws with respect to existing demographic statuses, like age, gender, level of education, occupation, and access to latest information on improving sector performance and economic transformation of potato farming communities, without leaving anyone out of the production and supply chain processes from participation in decision-making on institutional development, SCI and economic development of the sector.

At the individual level, the findings revealed that location of the farmers influenced the implementation of bylaws. The level of implementation of bylaws varied from one place to another. Thus, having an understanding of baseline information about a given location was important before any proposed interventions to enhance the implementation of bylaws for sustainable intensification of potato production to alleviate poverty, reduce inequalities, and ensure sustainable development of the region. Also, it was important to bring all farmers on board, across all villages and sub-counties with target messages for different locations and places. Similar observations were made by Mowo et al. (Citation2016) that the process of formulating bylaws required more focus on the area, where the problem was taking place rather than generalizing it as a national one. Emphasis on consultations was important and vital to garner consensus at the lower level, where the problem took place. It was at this point that value of new institutionalism theory began taking effect on the farming communities in the region. They were on their way to a prosperous future. Often generalization aimed at simplifying the process to ensure that there were bylaws in a given administrative area to facilitate performance evaluation purposes. But these were unlikely to be effective in the long run, especially, where success was measured by the number of bylaws passed rather than the site-specificity of the bylaws. Therefore, it was important in the implementation of bylaws as a matter requiring specific locations to have a mechanism of full involvement of the local communities and harness benefits of sustainable intensification of potato production, such as poverty eradication, reduced inequalities, and sustainable livelihoods among farming communities in the region.

5.4. Gender inequality affected the implementation of bylaws

The study revealed that women were less likely to implement bylaws compared to their male counterparts. Women were unaware of the bylaws and lacked the right to own land, despite playing a leading and distinct role in addressing development challenges, which strengthened efforts towards sustainable development in general. Also, power-relations had roots in gender-inequality and biases in decision-making, which characterized institutionalization processes, efforts towards SCI, and explained deceleration of growth. This was echoed in the reviewed literature, which expressed low production of potato crop in spite of its great contribution towards improved livelihoods of people associated with the sector, directly or indirectly, as well as strengthened economic progress of SSA (e.g., Godfray, Citation2015; Vanlauwe et al., Citation2014). Southwestern Uganda are among areas in SSA affected by low production of potato crop, with implications of gender-inequality and limited involvement of women in decision-making on matters of institutional development, bylaw formulation, and implementation, SCI, and economic benefits of and from the sector.

Further, a related studies recognized the distinct and selfless role of women in ensuring food security despite working under very challenging socioeconomic conditions. This reiterated the unfair treatment of women that was entrenched in the cultural, socioeconomic, and political systems of society despite the central role women play in crop production and development of agricultural economies (Ashby et al., Citation2008). Therefore, the lack of rights to own land aliened women most since it denied them all entitlements associated with land resource, including potato crop production, management of production processes, and any influence in policies (on land and production). This explained why new institutionalism theory entailed critical demographic aspects like gender. It strengthened efforts towards inclusive and sustainable development of the region.

As observed, most implementations of bylaws necessitated access to land. Undermining gender issues in policy development processes limited implementation and impact of the policies on sustainable intensification of potato cropping and development of the region. Policy makers at local level were able to develop mechanisms to undertake a thorough and participatory gender analysis. For example, during bylaw formulations, institutions which worked on gender-responsive agricultural practices were brought on board to advise and make an input in the development processes. Forum for Women in Democracy (FOWODE, Citation2012) confirmed the lack of efforts by policymakers to undertake gender analysis ahead of policy formulation processes, strategies, and programs on crop productivity in Uganda. Accordingly, Assan (Citation2014) suggested the need for women’s affairs ministries to get involved in the policy processes, or directly make contributions in the policy documentations, to ensure adequate attention to the productive roles of women in strengthening efforts towards sustainable development of the sector. Aggregation of inclusivity and equity aspects in the new institutionalism theory in potato sector development ensured efficacy of the bylaws and realization of economic benefits of SCI, such as increased production, high-quality yields, poverty eradication, reduced inequalities, improved livelihoods, and sustainable development of the region.

5.5. Farmer’s major occupation impacted implementation of bylaws

Farmers engaging in small trade activities were less likely to implement bylaws compared to farmers who had no other form of occupation. This was attributed to the fact that farmers who engaged in commercial potato production were likely to implement bylaws as they considered this to be their core source of livelihood. As a way forward, it was important to encourage farmers to grow potato crops and treat it as a business. With this in focus, the farmers begin to look at farming as an investment rather than as a secondary activity or hobby. Henceforth; implementation of bylaws for SCI enabled increased investment in the sector. Notwithstanding the impact of “having another job” on SCI, it was pure logic that potential income of farmers with two jobs was a lot higher and worked to benefit them, even better, in terms of realizing higher incomes and sustainable livelihoods. Although SCI was motivating enough for farmers with two jobs, they took it lightly. Indeed, it only worked against them if they did not tap into potato-growing sector for increased and sustainable income, such that, in case one job failed due to unforeseen events, another filled up the income gap. With that in consideration, new institutionalism theory presented a collective platform for everyone to contribute towards the development of the sector and benefit from economic prospects associated with it, such as sustainable incomes year round. Therefore, it was positively rewarding for business people to be involved in the implementation of bylaws (Weiermair et al., Citation2008).

The partnerships allowed farmers to process easily their harvest and make use of improved marketing facilities. In addition, innovative business models, such as signing of contracts between investors and farmers’ groups to supply a fixed amount of potatoes at favorable purchase fee influenced productivity. Farmers were encouraged to explore ways to improve the quality of seed, appropriate fertilizers, and customer-friendly bags for packaging their harvest. This enhanced implementation of both formal and informal bylaws, especially access to markets, improved and quality seed, which contributes to economic growth and national income.

With regards to the aspect of “farmers identifying with other farmers and local leadership in potato producing areas”, the findings showed that they were more likely to implement bylaws than those who did not have or participate in farmers’ associations. Farmers’ networks enhanced collective effort towards implementation of bylaws and boosted their ability to implement bylaws. Similarly, Sanginga et al. (Citation2010) demonstrated the importance of social capital as an asset, upon which people who largely depended on the natural resource base drew sources of livelihood and inspiration to sustain such livelihoods. Therefore, these associations needed to be fostered and nurtured to yield the desired development outcomes. Similarly, a study by (Pretty, Citation2003) demonstrated that social capital lowered the cost of working together, facilitated cooperation, trust, and collective action. The self-organizational capacities within communities created conditions, in which local people formulated, reviewed, monitored, implemented appropriate bylaws, and engaged in mutually beneficial collective action (Sanginga et al., Citation2004; Scoones & Thompson, Citation2003). Actions towards a common goal enhanced SCI, which was crucial in constructing key aspects of new institutionalism theory and rendering bylaws effective to gain economic benefits from the sector. The strength of this study was its ability to establish the impact of each factor influencing implementation of bylaws, individually, and examine their respective contribution towards development of new institutionalism, its application, and strength of the bylaws in realization of SCI and economic prospects associated with it.

6. Conclusions and recommendations

The study concludes that supportive bylaws were crucial in promoting sustainable crop intensification. However, it was not enough just to adopt bylaws, effective implementation of these mattered. Although each of these factors individually influenced bylaws implementation, they were, of course, interrelated. For example, knowledge on an issue typically was a prerequisite to implementation of the bylaws. The study demonstrated that implementation of bylaws was influenced by several factors, both at community and individual levels.

Efforts towards strengthening elements of new institutionalism theory to promote sustainable potato intensification demonstrated by effective bylaw implementation required creation of awareness. There was a big role played by extension services. Thus, it is necessary to strengthen and support them in the implementation of bylaws. Initiatives to move the farmers from just looking at potato production and productivity in a subsistence manner to venturing into potato farming, as a business, needs to be fostered to benefit from the economic potential of the sector. The farmers could take advantage of the existing social capital to enhance their bylaws implementation for improved quality of seeds, ensuring proper soil and water conservation, and market access by linking with fellow farmers in farmer groups and associations. Financial and technical support is needed to strengthen formal and informal farmer groups and collaboration with government, development partners, and researchers.

Furthermore, findings suggested the need to address gender inequality in decision-making processes in potato cropping systems. Accordingly, concerted efforts are required in empowering women in the formulation and implementation of bylaws such as assigning them leadership roles in village committees and local councils as well as establishing women groups which bring forward the gender-based constraints in intensifying potato cropping systems. More attention is needed in devising mechanisms that narrow the gender gap in accessing land and relevant information to intensify potato cropping systems. The economic prospects of SCI and sustainable development were elusive without increased gender equality and social inclusion.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Makuma-Massa Henry

Henry Makuma-Massa is a PhD scholar at Makerere University, Uganda. His research interests are on local polices, sustainable crop intensification, and environment. This study was part of the Policy Action for Sustainable Intensification of Ugandan Cropping Systems project.Paul

Kibwika is associate professor at Makerere University with research interests in agricultural knowledge systems; innovations management and social transformations; and adaptive management and sustainability.

Paul Nampala is currently working as an Independent Consultant with the Geotropic Consults. He is also an associate lecturer at the Uganda Christian University.

Victor Manyong is an Agricultural Economist with IITA. His research interests are on adoption and impact; production and marketing economics; and policy.

Mastewal Yami is an independent consultant based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Formerly, she served as a Policy Scientist in IITA. Her research interests are interplay of policies, institutions, gender issues in cropping systems, and the governance of land and water resources.

References

- African Union (AU) (2003). The Maputo declaration. Maputo, Mozambique. Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://www.nepad.org/caadp/publication/au-2003-maputo-declaration-agriculture-and-food-security

- Alexandrowicz, R. W., Jahn, R., Friedrich, F., & Unger, A. (2016). The importance of statistical modeling in clinical research. Neuropsychiatr, 30(2), 92–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40211-016-0180-3

- Alinon, K., & Kalinganire, A. (2008). Effectiveness of bylaws in the management of natural resources: The West African experience. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), CAPRi working paper 93(15).

- Arts, B., & Van Tatenhove, J. (2004). Policy and power: A conceptual framework between the ‘old’ and ‘new’ policy idioms. Policy Sciences, 37(3–4), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-005-0156-9

- ASARECA. (2005). Potato and sweet potato sub-sector analysis: A review of sub-sector status, constraints, opportunities and investment priorities.

- Ashby, J., Hartl, M., Lambrou, Y., Larson, G., Lubbock, A., Pehu, E., Ragasa, C., (2008). Investing in women as drivers of agriculture. Agriculture and Rural Development: Gender in Agriculture. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/75675

- Assan, N. (2014). Ensuring equitable resource allocation and gender sensitive policies in supporting food production and security in Southern Africa. Scientific Journal of Biological Sciences, 3(8), 77–83. doi:10.14196/sjbs.v3i8.1769

- Baulcombe, D., Crute, I. Davies, B., & Green, N. (2009). Reaping the benefits: Science and the sustainable intensification of global agriculture. The Royal Society.

- Bremer, M. (2012). Multiple linear regression. Published in the Journal “Math 261A-Spring.

- Brookfield, H. (2001). Intensification, and alternative approaches to agricultural change. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 42(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8373.00143

- Campenhout, V. B. (2016, September 23–26). Risk and sustainable crop intensification: The case of small-holder rice and potato farmers in Uganda. Invited paper presented at the 5th International Conference of the African Association of Agricultural Economists.

- Chartres, C. J., & Noble, A. (2015). Sustainable intensification: Overcoming land and water constraints on food production. Food Security, 7(2), 235e245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0425-1

- Colding, J., & Folke, C. (2001). SOCIAL TABOOS: “INVISIBLE” SYSTEMS OF LOCAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. Ecological Applications, 11(2), 584–600. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2001)011[0584:STISOL]2.0.CO;2 2

- FAO. (2013). Monitoring African food and agricultural policies (MAFAP): A review of food and agricultural policies in Uganda 2005–2011 country report.

- FAOSTAT (2014). http://data.fao.org/database?entryId=262b79ca-279c-4517-93de-ee3b7c7cb553. Accessed on July 2020. Food and Agriculture organisation of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. http://data.fao.org/database?entryId=262b79ca-279c-4517-93de-ee3b7c7cb553

- Foresight. (2011). The future of food and farming 2011. The Government Office for Science. Final Project Report.

- Fowler, F. (2001). Survey research methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- FOWODE (2012). Agricultural financing and sector performance in Uganda: A case study of donor-funded projects. The report, 52.

- Galvin, P. F. (1989). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation of a big brother/big sister program: Planning and evaluation example. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90022-0

- Godfray, H. C. J. (2015). The debate over sustainable intensification. Food Security., 7(2), 199e208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0424-2

- Haggblade, S., & Hazell, P. (Eds). (2009). Successes in African Agriculture: Lessons for the future. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kassie, M., Teklewold, H., Jaletab, M., Marenya, P., & Erensteinb, O. (2014). Understanding the adoption of a portfolio of sustainable intensification practices in eastern and southern Africa. Land Use Policy, 42(2015), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.08.016

- Kayambazinthu, D., Matose, F., Kajembe, G., & Nemarundwe, N. (2003). Institutional arrangements governing natural resource management of the Miombo woodland. In G. Kowero, B. Campbell, & U. Sumaila (Eds.), Policies and governance structures in woodlands of Southern Africa (pp. 45–64). Center for International Forestry Research.

- Klerkx, L., & Jansen, J. (2010). Building knowledge systems for sustainable agriculture: Supporting private advisors to adequately address sustainable farm management in regular service contacts. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 8(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2009.0457

- Mohammed, A. K. (2013). Civic engagement in public policy making: Fad or reality in Ghana? Politics & Policy, 41(1), 117–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12003

- Mowo, J., Masuki, K., Lyamchai, C., Tanui, J., Adimassu, Z., & Kamugisha, R. (2016). By-laws formulation and enforcement in natural resource management: Lessons from the highlands of eastern Africa. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 25(2), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2016.1159998

- Nkonya, E., Pender, J., & Kato, E. (2008). Who knows, who cares? The determinants of enactment, awareness, and compliance with community natural resource management regulations in Uganda. Environment and Development Economics, 13(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X0700407X.

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- OECD/FAO (2016). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016-2025. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/agr_outlook-2016-5-en

- Otsuka, K., & Place, F. (2014). Evolutionary changes in land tenure and agricultural intensification in sub- Saharan Africa. United Nation University Working Paper, 2014/051(November), 47. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199687107.013.015

- Pingali, P. L. (2012). Green Revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead. PNAS, 109(31). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912953109

- Pretty, J. (2003). Social capital and the collective management of resources. Science, 32(5652), 1912–1914. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1090847

- Pretty, J. (2008). Agricultural sustainability: Concepts, principles and evidence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 363(1491), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2007.2163.

- Pretty, J., & Bharucha, P. Z. (2014). Sustainable intensification in agricultural systems. Annals of Botany, 114(8), 1571-96. www.aob.oxfordjournals.org.

- Royal Society. (2009). Reaping the benefits: Science and the sustainable intensification of global agriculture.

- Sanginga, P. C., Abenakyo, A. R., Martin, M. A., & Muzira, R. (2009). Tracking outcomes of participatory policy learning Kamugisha and action research: Methodological issues and empirical evidence from participatory bylaw reforms in Uganda.

- Sanginga, P. C., Kamugisha, N., . R., & Martin, A., . M. (2010). Strengthening social capital for adaptive governance of natural resources: A participatory learning and action research for bylaws reforms in Uganda. Society & Natural Resources: An International Journal, 23(8), 695–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802653513

- Sanginga, P., Kamugisha, R., Martin, A., Kakuru, A., & Stroud, A. (2004). Facilitating participatory processes for policy change in natural resource management: lessons from the highlands of southwestern Uganda. Uganda Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 9, 950-962. http://naro.go.ug/UJAS/ujas.html

- Scoones, I., & Thompson, I. (2003). Participatory processes for policy change. PLA Notes, 6(10), 51–57. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/9224IIED.pdf

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage.

- Struika, P. C., Klerkx, L., & Hounkonnou, D. (2014). Unravelling institutional determinants affecting change in agriculture in West Africa. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 12(3), 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2014.909642

- UBOS. (2017). The national population and housing census 2014 – area specific profile series. Kampala Uganda: Uganda Bureau of Statistics

- Vanlauwe, B., Coyne, D., Gockowski, J., Hauser, S., Huising, J., Masso, C., Nziguheba, G., Schut, M., & Van Asten, P. (2014). Sustainable intensification and the African smallholder farmer. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 8, 15-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.06.001

- Vargas-Hernández, J. G. (2008). Institutional and neo-institutionalism theory in the international management of organizations. Vision of the Future, 10(2), 125–138. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7404964

- Vorley, B., Cotula, L., & Chan, M. K. (2012). Tipping the balance: Policies to shape agricultural investments and markets in favour of small-scale farmers. Oxfam.

- Weiermair, K., Peters, M., & Frehse, J. (2008). Success factors for public private partnership: Cases in alpine tourism development. Journal of Services Research Policy, 8, 7-21. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-39512010000400003

- Xie, H., Huang, Y., Chen, Q., Zhang, Y., & Wu, Q. (2019). Prospects for agricultural sustainable intensification: A review of research. Land, 8(11), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110157

- Yami, M., & Asten, P. (2017). Policy support for sustainable crop intensification in Eastern Africa. Journal of Rural Studies, 55(2017), 216e226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.012

- Yami, M., & Asten, P. (2018). Relevance of informal institutions for achieving sustainable crop intensification in Uganda. Food security: The science, sociology and economics of food production and access to food. The International Society for Plant Pathology, 10(1), 141–150. DOI: 10.1007/s12571-017-0754-3