?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Khat is one of the most controversial products of our time which is mostly produced and consumed in the eastern parts of Africa and Saud Arabia. This study contributes to the debate on khat by comparing the family wellbeing of khat chewer (consumer) and non-chewer families in Harar city, by using the International Wealth Index’s (IWI) characterization of wellbeing. The study utilized the survey method. Respondents were identified using a cluster sampling method. The data was gathered using an interview schedule, in-depth interviews, and non-participant observation. Appropriate time was considered in dealing with chewer respondents. The findings of the study indicate that there is a great difference between families who chew khat and who did not, in terms of their material well-being, housing, and quality of life. Most of the khat consumer households have no emergency money nor plan for their families. The data from key informant interviews also show that women experience the greatest burdens of the negative impacts of khat consumption habits. Khat culture affects the base of a community, the family, by affecting its social and economic wellbeing and disrupting its unity. There is no simple solution for addressing the problem of khat due to the intricate nature of the problem. Health officials and health institutions can establish rehabilitation institutions and civil societies can establish a voluntary foundation which creates awareness on the impact of khat on a family.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The using of khat is expanding in Ethiopia. Although some people claim it help some individuals to work hard by postponing fatigue, the recent wider use at the community level is making it clear it also has a negative economic and social impacts on the chewer family. By comparing the economic wellbeing of families who use khat and families who did not use, this study finds that the material wellbeing, housing and its quality, family happiness and unity of the families who did not use khat are far better than those who use khat.

1. Introduction

Khat consumption is contentious (Anderson et al., Citation2007); many nations have listed it as a controlled substance (Cochrane & O’Regan, Citation2016). Some nations have linked khat with terrorism and the commercial sex industry (Beckerleg, Citation2009; Gebissa, Citation2012). Similarly, some scholars present khat as a malicious product that distracts the nation’s health, economy, and family (see Abiye et al., Citation2007; Cox & Rampes, Citation2003; Hassan et al., Citation2007; Nakajima et al., Citation2016; Wuletaw, Citation2018). While others argue that khat has cultural or religious significance for a nation (Carrier, Citation2007; Gebissa, Citation2004; Carrier, Citation2005). These scholars point out the positive economic impacts it has for a country and a family (see Armstrong, Citation2008; Beckerleg, Citation2009; Gebissa, Citation2012, Citation2010b, Citation2009). Ference (Citation2009) suggests that khat is “the most controversial and ubiquitous stimulant.” Yet, given the scale of production and consumption, relatively little is known about the many ways in which khat interacts with lives, livelihoods and economies (Wolf, Citation2013, p. 2). This paper provides insight into a question raised by Wolf (Citation2013), which wonders if while khat production is flourishing if Ethiopians are flourishing because of khat. This study analyses specific aspects of economic well-being, particularly the individual and family, as experienced in Harar, Ethiopia.

Khat is a leafy shrub planted mostly in the north-eastern parts of Africa, including Ethiopia. Khat leaves and buds contain the alkaloid cathinone, a stimulant, which is said to cause excitement, loss of appetite, and euphoria (Carrier & Klantschnig, Citation2018). Khat is “chewed” or held within the mouth while absorption takes place (typically only the “juices” are swallowed, not the leaves). Khat consumption or chewing is a habit of chewing khat frequently and encountering symptoms of withdrawal when consumption is skipped or missed. Khat culture is the widespread consumption of khat in a given community, which is a growing trend now in Harar. It is a community level khat consumption where every group of people chews khat, like in Harar.Footnote1 In Harar, khat is used not only for entertainment but also for more serious businesses like religion and work, and they accepted it as an integral part of their culture. Khat culture also involves the ceremony of chewing khat. This culture develops over a long period of time. Written evidence shows that khat chewing started in Harar before the 19th century (Burton, Citation1856). One of my informants said, “this is the culture that we inherited from our grand grand-fathers.” Khat chewer or consumer, in this study, refers to a person who uses khat at least two or three times a week and feels uncomfortable, bored and displays unusual behavior including depressive mood, irritability, anorexia, and difficulty to sleep and mood swings when not consuming or finding khat (ECDD, Citation2006; Havell, Citation2004). People in Harar called this feeling Haraara.

Different organizations and scholars used different kinds of indicators of family well-being. There is very limited research work in Ethiopia which is related to family well-being. The only work that tried to explain living standards is a report by Development Planning and Research Directorate, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, which equates living standards with well-being (Citation2012). Most scholars measured family well-being by looking at economic well-being, which is understood from asset ownership indicators and basic housing quality variables. In addition, the International Wealth Index (IWI) used the material as indicators, it measures a household’s level of material well-being by looking at the “household’s possession of durables, access to basic services, and characteristics of the house in which they are living.” (Smits & Steendijk, Citation2013, p. 3; Wai-Poi et al., Citation2008, p. 11) Well-being also includes “the quality of relationships between parents and the quality of parent-child relationships” (McKeown et al., Citation2003, p. 5). Other studies relate these variables with living standards, the ease by which people living in a time or place can satisfy their needs or wants (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], Citation2011).

The IWI work on wellbeing is not only recent work on the subject but also clearly illuminates indicators which is measurable and match with the culture and economy of Harar, the study area. Moreover, IWI is “the first strictly comparable [asset-based] index for household’s long-term economic status that can be used for all low and [middle-income] countries.” (Smits & Steendijk, 2013, p. 1) Besides, in relation to the objective of this study, these indicators are believed to be enough because the focus of the study is not on the precise measurements of family well-being rather on the comparison of two groups, chewer and non-chewer household. To compare the family wellbeing of khat chewer and non-chewer families and demonstrate the impact of khat consumption, there is no better place than Harar, where khat use first started and diffused to a considerable portion of the community (Zerihun, Citation2019). In terms of the prevalence of khat chewing, studies show that Harar is the leading city in Ethiopia (Wuletaw, Citation2018). Khat is not cultivated in Harar city rather it is imported from Awaday and other surrounding Oromo villages. Thus, the residents of Harar city is basically buyers and consumers of khat. Because of this, similar to scholars mentioned above, there is always a debate among the people in Harar regarding whether khat is good or bad for a community and specifically for family wellbeing.

2. Methodology

2.1. Description of the study area

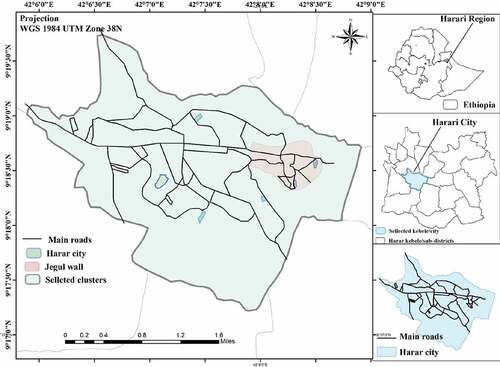

Harar is the capital of Harari Regional State, which is one of the nine regional divisions of states in Ethiopia. Harar city has two parts: the old, which is surrounded by a wall called Jegul, and the new outside of Jegul (see Figure ). According to the population projection figure of 2011, 110,457 people live in both parts of the city. The city is located on a hilltop, in the eastern extension of the Ethiopian highlands, at about 525 km east of Addis Ababa, with an elevation of 1,885 meters. The walls surrounding the old part of the city (Jegul) was built between the 13th and 16th centuries and served as a protective barrier from external invasions. (Sultan, Citation2011).

The entire region has 46,169 households. Ethnic groups in the a include Oromo (56.41%), Amhara (22.77%), Harari (8.65%), Guraghe (4.34%) and Somali (3.87%). The majority of the population of the area are the followers of Islam, 68.99%, followed by Ethiopian Orthodox, 27.1%, and Protestant 3.4%.

2.2. Sampling techniques

The population of the study consisted of the residents of Harar city and the sampling focused upon households in the city. Cluster sampling was used to identify the respondents. Households in blocks or clusters were identified using Google Earth and Google Maps as well as Harari Regional State Tourism Bureau’s maps. Using the maps, households were divided into 61 clusters or blocks, as per physical settlement patterns and infrastructure, such as highways and small roads; letters were assigned for each block. A lottery method was used to select clusters from where the data were collected. The selection of districts using the lottery method continued until the required sample size was achieved. A total of six clusters were included in the study. (See Figure )

The required sample size, 398 respondents, were identified using Slovin’s formula, n =. The sample size was divided into two groups, 201 khat consumer households, and 197 non-consumer households. A chewer household was defined as a household where a family head (usually husband) and other family members consume khat at least two or three times a week. Non-chewer households were a household where a family head (usually the husband) did not consume khat, although some other members might. The focus on the household head to define participants as “consumer” and “non-consumer” is based on the economic significance of the head for the family. Thus, although in most instances the household head is a husband, there is also a case in which a wife or an older son or other relatives in the family become a household head. The focus is on the economic significance that the “family member” has in the household.

2.3. Approach and tools of data collection

Before starting the study, ethical clearance was obtained. Most of the data for this research were collected using an interview schedule. The questions comprised of various probes related to the participant’s experiences regarding khat chewing and its related activities. The researcher identified appropriate time for the interview schedule, particularly to deal with the addicted khat consumers. This includes time before they begin chewing and before those who could not find khat feel bad. This is a very important point neglected by most scholars who researched khat. However, no one denies that khat does influence not only the behavior, feeling, and mood of the consumers, but also their speech and action (Cox & Rampes, Citation2003; Havell, Citation2004; Rita Annoni, et al. Citation2009), and this consequently affects the result of the study.

After identifying the sample size and a block using the lottery method, the researcher directly moved to the area and started to knock houses in a row for interviews. In most instances, the interview was conducted with the household head. However, there were some families where the household heads allowed active members of the family to answer the questions. After asking general information about the household, which is for both chewer and non-chewer, the household head was asked if he/she is a chewer (consumer of khat). If the household head is a chewer, the specific questions related to khat consumption will be asked, if not, only question common for both groups are administered. However, in some clusters in Harar, especially within the Jegul, it is difficult to find non-consumer households, thus the researcher was forced to skip some households in order to include the required number of non-consumer households from the selected clusters. The move from block to block and house to house for interview allowed the researcher to conduct the observation. During the interview, the researcher observed the environments, house equipment, from what the house is built and the others using the already prepared checklists. In some instances, where it is not clear to observe, the researcher is forced to ask questions to fill the checklist of observation. At the end of the interview with consumer households, the researcher asked for any non-chewer family member who lives with the chewer for key informant interviews.

The 20 key informant interview participants were identified purposively from chewer households and interviewed separately to freely speak the effect of khat culture in their families. These are non-chewer family members who live with chewer household heads. They are the ones eager to share the effect of khat consumption on their family. It allowed us to capture any effect of khat in the household which is not mentioned by the chewer household head.

All the data from the interview schedule, key informant interview and observation are recorded on a sheet of paper prepared separately for each household with different identification. Then the data typed on an excel sheet to be imported to SPSS and analyzed. Using statistical tools like frequency, percentage, mean and median results are generated. The data was organized in such a way to allow comparison between two groups of people who live under the same structure but different in terms of the presence of khat consumer household head in the family. Because the purpose is to see any differences caused by khat consumption. For this, the statistical tools listed here are believed to be enough.

There were some limitations in this study: first, difficulty in obtaining some specific data related to household economic wellbeing. Some families were afraid to share while some others did not have the information. There was also difficulty in finding a precise indicator and measurement for family well-being. Various institutions and researchers used different kinds of indicators and measurements and there is no study in Ethiopia on wellbeing. The researchers adopted some indicators of family well-being from the International Wealth Index (IWI), which are convenient to compare two groups of households and goes with the context of Harar and Ethiopia. Third, difficulty finding an appropriate time to interview addicted to khat consumers. Although, for most of them the best time is 9:00 am to 10:00 am, still some participants want to engage in khat consumption at these times. Lastly, difficulty identifying whether the difference between consumer and non-consumer is actually due to the structure, inheritance or overall economic problem in the country. However, the researcher tried to randomly identify the respondents who live under the same structure. The impact of the economic problems in the country is equal for both chewer and non-chewer families. For other challenges, like inherited properties, for instance, house residences, the researcher tried to look at the differences between the two groups and found that the number of inherited houses for both chewer and non-chewer families is very small and almost equal.

2.4. Theoretical and conceptual framework of the study

Similar to the case of khat, there is also debate on whether or not culture is related to economic wellbeing. Some scholars argued that there is a strong relationship between culture and living standards. For instance, probing the difficult questions of why some modern industrialized nations are more successful than the others at providing basic freedoms and decent economic wellbeing to their people Harrison and Huntington looked on the cultural values underpinning societies. Moreover, they argued that they are “the key to understanding the success or failure of the ‘developed’ nation.” (Harrison and Huntington, ed., Citation2000, p.xviii-xxix). Regarding the case of Africa and other underdeveloped countries, they stated that, if colonialism and dependency are not a satisfactory explanation for poverty, authoritarianism and underdevelopment, and if there are so many exceptions for the geographical or climatological explanations how else can the unsatisfactory progress in the past century be explained? Moreover, they discussed issues like “Culture [makes] almost all the difference” to strengthen their argument. These scholars, who supported the relationship between culture and economic development started with modernization theorists and were dominant in the 1950s and 1960s.

On the other hand, another group of scholars argued that there is no relationship between culture and living standards or economic wellbeing. They discussed the example of Japan to show how high living standard is possible by keeping traditional cultural values. Ambe J. Njoh regarded modernization theorists as those who promote western culture rather than development. He revealed that they put under development and poverty in Africa “as products of African indigenous customs and cultural tradition,” but this is “outlandish charges” against African culture. Njoh tried to show as Africa had its own civilization in the past that can serve as a model for the current development planers for poverty alleviation and development (Njoh, Citation2006, p. ix–xi). The scholars who oppose modernization theory started with the dependency theory.

Modernization theorists themselves have two views. Some (like Karl Marx and Daniel Bell) have argued that economic development brings pervasive cultural changes, while others, like Max Weber and Samuel Huntington, have claimed that cultural values have an enduring and autonomous influence on the economy of a given society (Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000). Weber, in his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, wrote: “to what combination of circumstances the fact should be attributed that in … Western civilization only, cultural phenomena have appeared” (Weber, Citation1930, p. 13). The basic question of Weber was why capitalist manufacturing became dominant only in the economies of Western Europe. The answer according to him is the existence of a cultural process peculiar to Western society, namely: “rationalization”. He explained the role of western culture, particularly Christianity and rationalism. Weber focused on the doctrines of Calvinism, which strongly believes in the significance of predestination. This is the belief that God has already decided on the saved and the damned. Accordingly, no one knows whether he or she is one of the “chosen few”. This teaching led to the belief that economic success was a sign of election, promoting hard work and rationality. In short, culture (Christianity) indirectly promoted rationality, which in turn led to capitalism, economic development and high living standard and economic wellbeing. By this, Weber clearly stipulated the relation between culture and living standards (Weber, Citation1930, pp. 120–135).

Another recent study by Ronald Inglehart and Wayne E. Baker justified the theory of Weber in a more clear way. Using data from the three waves of the World Values Surveys, they found that economic development and good living standard is associated with shifting away from absolute norms and values toward values that are increasingly rational, tolerant, trusting, and participatory. However, they stated, cultural change is path-dependent. The broad cultural heritage of a society: Protestant, Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Confucian, or Communist-leaves an imprint on values that endures despite modernization. They concluded, “Economic development is associated with pervasive and to some extent predictable cultural change.” Thus, although modified a little bit, they supported the idea of modernization theory that the rise of “industrial society is linked with [a] coherent cultural shift away from traditional value systems” (Inglehart & Baker, Citation2000, p. 49). Generally, although the researcher does not agree with most of the ideas of modernization theorists of the 20th century, many compelling studies justified the relation between culture and economic development or living standard.

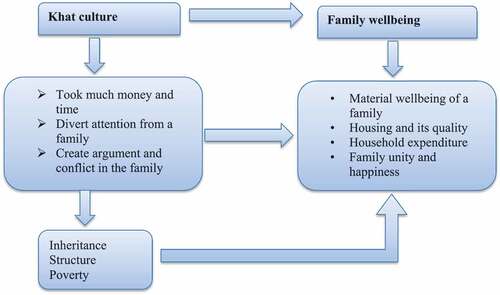

In this study, the driving power behind a living standard, and which hinders better economic wellbeing, as shown in the following diagram, is khat culture. Khat culture, which includes not only the long hours spent on chewing but also the money spent on buying khat, the attention it took, the habit it produces and the conflict it creates in a family can affect not only the households ownership of material wellbeing, but also the quality and quantity of material they own, the amount of time a family can spend together, and family unity in general. These tremendously affect not only the income of a family but also the time they have together as a family.

In general, as the khat culture continues to exist in a society, it continues to affect the material wellbeing, housing and its quality, household expenditure, family unity, expenditure, and the overall economic wellbeing of a family by taking the lions to share of the household income, creating an argument and taking the attention of the household head. Although not considered in this study, inheritance, the overall structure and poverty level of the country also has its own impact on the economic wellbeing of a family.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Summary of the respondents’ profile

The data were collected from a total of 418 respondents using an interview schedule, key informant interview, and non-participant observation. From the participants in the interview schedule, 201 are consumer households and 197 are non-consumer households. The following Table presents the marital status and family size of the respondents. The data shows that, relatively, chewers are greater than non-chewers in terms of being single and divorced. The reason for this will be discussed in detail in the following subtopics.

As shown in Table , great difference between consumer and non-consumer households only appeared on large family size (households which have greater than five family members): 42 (20.9%) of the consumers have large family members while it is only 18 (9.1%) for non-consumers. This indicates that, although like non-chewers, some of the chewers are not married, once they got married, there is difficulty managing their family size. This has a negative impact on the chewer households’ family well-being by creating stress and shortage of resources in the house. Moreover, this is bad news for countries like Ethiopia, which is struggling to minimize its birth rate.

In terms of religion, 183 (45.9%) of the respondents are Muslim and 209 (52.2%) are Christians. However, 117 (63.9%) of the followers of Islam consume khat, while only 78 (37.3%) of the Christians consume khat (See Table ). This indicates the role of religion in the decision to chew or not khat. Some religious groups strongly believe and teach their followers that khat chewing is a serious sin in front of God while others keep silent. Although some of my Muslim informants indicated that the Quran does forbid intoxication and drug use, most of them believe that khat chewing is a culture that is acceptable by God. This is similar to the findings of Gebissa (Citation2004), who conducted his study in the same region and his informants indicated that khat is not only allowed by God but also a gift from Allah.

Ethnically, for both chewer and non-chewer households, the Amhara constituted the largest, followed by the Oromo. These figures only show the average amount of all ethnic groups who participated in this study, not the percentage of ethnic groups in Harar city. All the Tigre participants are non-consumer and all the participants from Southern Nation and Nationalities become consumers. The Somali case is also unique since the majority of the participants are consumers.

3.2. Comparison of the material well-being of chewer and non-chewer families

The material wellbeing indicators used by IWI to measure a household’s material well-being can be divided into two: nonperishable and perishable home materials. Nonperishable home materials are materials that are not subject to rapid deterioration or decay. These include television, computer, refrigerator, stove, beds, home residence and others.

The result on the above table shows that there are no such great differences between consumer and non-consumer families in terms of the ownership of television and radio, which is mostly used for entertainment. Even, radio is mostly owned by consumer families. This is because, first, during the chewing ceremony consumers need issues to discuss or talk about, for this radio and television are essential sources. Second, some chewers claimed that they chew khat for entertainment, for this television and radio are used to increase the value obtained from it. That is, they are the required, although not mandatory, materials for the khat ceremony. Thirdly, since chewing mostly involves sitting in one place for a long period of time, some find it boring unless there is something to watch or listen to. That is also why some of the key informants stressed, the chewers like television very much, and they do not want to have a khat ceremony without it. As shown in Table , regarding the computer and telephone (fixed), there is a considerable difference between the two groups. These home materials are mostly needed to facilitate work or business than entertainment.

Table 1. Marital status and family size of the respondents

Table 2. Religion and ethnic composition of the respondents

Table 3. Some indicators of material well-being: ownership of home materials

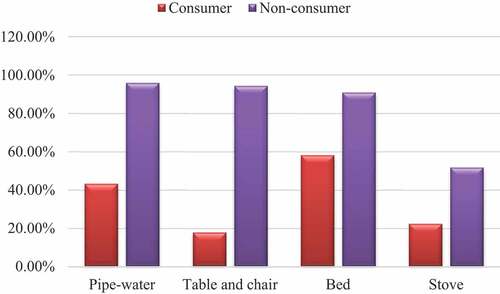

Table also shows as the home materials become more necessary for life there are more widened differences between consumer and non-consumer households. For this, we can see the refrigerator, locker, and stove or cooking machine (in Figure ). These home materials are needed not only to add joy for the family but also necessary since they make life easy, organized and comfortable. These materials also indicate how household heads care for their family members, especially wives, who mostly use these materials to perform their home chores. The absence of a stove means wives must use woods or charcoal to make food that consumes more of their energy and time. The absence of a refrigerator means foods have to be prepared instantly time and again since it is not possible to keep prepared foods unspoiled for a long period of time. The absence of a locker in a house also implies that there is no easy way to keep household stuff properly in an organized way. The interview participants disclosed that in a family, where there is a non-consumer, especially where the wife is non-consumer, there is always an argument to buy these home appliances than “wasting money” on khat consumption. Accordingly, family members, especially wives, are the first to feel the effect of khat consumption in the family.

When it comes to basic home materials and services, more differences are found between chewer and non-chewer families. Figure shows the difference between consumer and non-consumer households in terms of owning pipe water, table, and chairs. These are materials and services which are very necessary for life, without them life is very difficult for the family. For instance, only 43% of consumers have access to pipe-water while the rest, 57% have no access, this is only 4.1% for non-consumer families. Like other parts of Ethiopia, in Harar, it was the housewives or children who mostly fetch water from other places. Harar is known for its problem of water, this is common for both consumers and non-consumers. But the data shows non-consumers are doing better to cope up with the problem and provide what is necessary for their family. Some wives who participated in the key informant interview indicated that sometimes they need to travel more than 9 KM to fetch water. The implication of the absence of beds is not only for wives but also for the whole family members. More than 40% of the chewers sleep on the floor by laying a tinny couch or mattress on the floor, which also serves as a table and chair in the day time. They sit, eat, and sleep on this mattress, this creates a bad odor in the house and discomfort.

3.3. Housing and its quality: chewer vs non-chewers

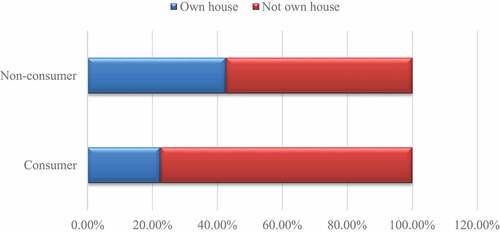

The other main indicator of family well-being is housing and its quality, food, and taking care of one family’s safety. Figure shows, only 45 (22.4%) of the consumers have their own houses while 84 (42.6%) of the non-consumers do own house residences. That is, non-consumers own houses two times more than consumers. In most instances, building or owning a house requires a large amount of money. However, consumers have an additional burden of expenditures in addition to the basic family needs. For most of them, the expenditure on khat ceremony is greater than expenditure for basic family needs. As a result, their saving culture is highly affected (Zerihun et al., Citation2019). If they do not save, obviously, it is difficult to buy or build a house. Not having once own house is very difficult for the well-being of the whole family members. They must rent a house which in turn again drain their monthly income or force them to live on the street. During the data collection, the researchers able to observe many khat consumers who live on the street because of their khat consumption habits.

Let us look at the case of FA, one of our key informants. She has two children one eight and the other six years old. They are living in a small house built from plastic garbage, it only has a place to lay down. If you want to sit the plastic roof will touch your head. Their life is very desperate and frustrating, on that day they have nothing to eat for lunch, they have to scavenge from the nearby condominium garbage to find food. I have asked how this happened? She remembered, “we have been having a good life there around Qalladanba [a place in Harar city]. My husband was an employed worker, as a guard. We have a salary. However, he chews khat every day. He cannot work without it. He smokes cigarettes too. Later, he also started to smoke shisha. After that our life started to deteriorate and got worse. While chewing khat he got late every time to go to work. It was after this that he lost his job. Now we cannot pay our rent and that is why we live here” pointing at here shanty house between two walls. She indicated that she also chews khat “sometimes” but argued that she is “not addicted” like her husband. This can show one reality behind many khat users that they cannot stop on chewing. After long years of using khat their satisfaction from it starts to decrease and they get fade up with it. Then they start to use other drugs alongside khat, which even more complicates their lives.

In addition to owning a house, what matters most is also the quality of the house. During the data collection, the researchers tried to observe what the house is constructed? The size or number of rooms; and the safety and cleanness of the house and its surroundings. The observation data is collected from both consumers and non-consumers who have their own house residence. Because, those who live in a rented house, the cleanness and safety of its surrounding depends not only on them, there were others who live in the same compound.Footnote2

The observation data shows that the majority of the houses of the non-consumers were built from bricks and stone, 43 (51.2%), but only 16 (35.6%) of the consumer’s houses were built from stone and brick. Most of the houses of the consumers were made from mud and wood, 18 (40%). A larger number of consumer’s houses are also built from shanty plastics and garbage, 5 (11.1%), and metal sheets 6 (13.3%). The size and number of rooms of most of the consumer households were small: 15 (33.3%) of them have only one room and 19 (42.2%) of them have two rooms. Whereas only 11 (24.4%) of the consumer households have three and above rooms, this is 24 (28.6%) for the non-consumer. Moreover, a clearer difference between consumer and non-consumer houses were seen on its safety and cleanness. Most of the houses of the consumer households were found to be not hygienic and safe. Some of them even not have a fence, 8 (17.8%), and their fences were getting too old, 19 (42.2%). Dogs and other animals can pass through it. On the other hand, 53 (63.1%) of the non-consumer households have a very good fence. Moreover, relatively the houses and the surroundings of the non-consumer households are clean. On the other hand, the environment, the sanitation, and the safety of the consumer houses are bad, messed, and full of dust, a leftover of khat and unclean materials (For all the data please see Table 1 on the Appendix). Although some of the participants (both chewer and non-chewer) live under extreme poverty, khat created a clear difference between the two groups. The effect of living in bricks/mud, small/big, one-room/many rooms and safe/unsafe, hygienic/unhygienic and houses with fences/without fence on the wellbeing of the family member is clear.

Particularly, the condition of those who say, “life for me is chewing” is very bad, compared to those who say “I only chew sometimes”. The majority of the houses of the former were made from wood and mud. The rooms of their houses are also small, crowded, and disordered. The quality of the furniture in the rooms also clearly indicates their lifestyle. It is full of dust and leftover of khat leaves and peanuts, materials used for the khat ceremony. Moreover, some of these consumers use the leftover of khat and peanuts that stored for long periods in their houses to lie on and chew khat. It is stinky and not good for the health of their family members. Although some of the problems encountering this group of consumers can be attributed to their economic status, it is not difficult also to sense that khat consumption habits can make them docile and careless about their hygiene or sanitation.

3.4. Effect of khat consumption on family unity and happiness

Although it is difficult to precisely measure “happiness” and “unity” for a family, it is possible to compare two groups of people using some specific indicators. For instance, by asking how much the family eats in a day, how much the family has a good time together and other related questions we can compare two groups’ relative contented state of being happy healthy. Moreover, data from observation and key informant interviews can help us clearly see the existing facts.

The above table shows that there is no consumer household who eats four times a day, while there are 51 (25.9%) non-consumers who eats four times. On the other hand, 54 (26.9%) of consumer households and 26 (13.2%) of non-consumer households eat two times a day. There is no non-consumer household that eats only once a day, but six (3.0%) of consumer households reported that they eat only once a day. This finding seems to match with the study by Solomon et al. (Citation2011) who suggests some consumers chew khat to decrease their appetite for food. Because of the economic problems, it is not easy to find food for this family, but they can easily find khat. Either they can chew by joining others or, at least, collect garaba (leftover of khat) in the khat market.

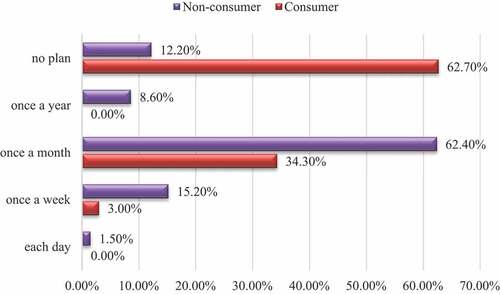

Table also presents how the households of consumer and non-consumer families have a good time with their family. Having a “good time with family” is explained for the study participants as allocating a specified time within a week, month, or a year and having at least a cup of tea or coffee only with once family members or relatives. If possible, going to other places with the family members (like a hotel, park, cafeteria or lakes shores) and on such occasions discussing family matters or having a good time. Although some people may consider this habit as “luxurious”, it is basic or vital to strengthen family unity and happiness. Nonetheless, there are a considerable number of consumers who responded that there is no such thing as having a good time with their families. In addition, on the frequency of having a good time non-consumers are far greater than consumer households.

Table 4. Comparison of the frequency of food consumption and having a good time

It was not denied that having or not a good time with once family has a great impact on the overall family’s well-being, not just for the family’s happiness but also for the unity of the family. Most of the consumer household heads only meet with their family when chewing or at night when they sleep together. This creates a boring and stressful situation in the family, leading to a bad relationship and conflict.

The other important factor that is considered under family unity and happiness is planning family life. This is explained for the informants as planning on what to do, how to do, where to entertain, what to eat, how much to spend, and how much children to have within a specified period of time. As the bellow Figure shows, more than half of chewer households responded that there is no such thing as a plan in their family. These results vividly depict how the consumers and non-consumers differ in managing their family. The majority of the consumers, particularly those who say “life for me is chewing” lead their family life without a plan. They have no objective or aim for the next month or year. It is easy to imagine the effect of such kind unplanned family life for a given family. This can indicate an absence of care for the family. That is most probably why some of the consumers do not have money saved for an emergency. These kinds of consumers do not care about tomorrow. Life for them is only to satisfy their need for khat today. When the consumer is the husband, his children also lead the same kind of aimless life. This lack of a plan also relates to a lack of family planning. As already indicated above, the average family size of the chewer household is greater than a non-chewer household.

During the data collection, the researchers made several separate discussions with consumers and clearly understood their perception of planning. Most of the consumers who say, “life for me is chewing”, when asked about planning they often say “tata yelegnim”, which literally means “I do not have a problem” or I do not care. Their friend also proudly says about them, “tata yelewum” or “he does not have a problem” or he does not care. The way they say or view and their perception about the one who is “tata yelewum” is positive and encouraging, they are reinforcing his behavior. On the other hand, they describe those who plan or view life seriously as “abo yakabidal” or “he is too serious”. The way they say implies the guy has a problem. Some even segregate this kind of people, because they did not spend money in a happy go lucky way with them. Paradoxically, key informants showed that those guys who described as “tata yelewum”, have a lot of problems: they smoke, chew, drink, they are in a debt and they have no emergency money or bank account. Since they did not fully support their family, they also have a lot of problems in their family.

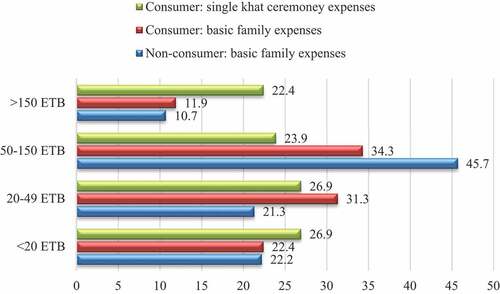

Although the existence of money cannot secure family happiness it can play a significant role in increasing overall family wellbeing. Looking at how a family spent or use money can help us understand what priority they give and their focuses in life. The following Figure presents the comparison of expenditure for basic family needs and expenditure on a single khat chewing ceremony during the data collection.Footnote3 Basic family expenses include expenditure for water, foods, soap, and other related daily expenses. The mean of daily expenditure for consumers is 52 ETB while it was 63 ETB for non-chewers. This expenditure may impact the quality and quantity of the foods being consumed by the family, and thereby give insight into how they care for their families.

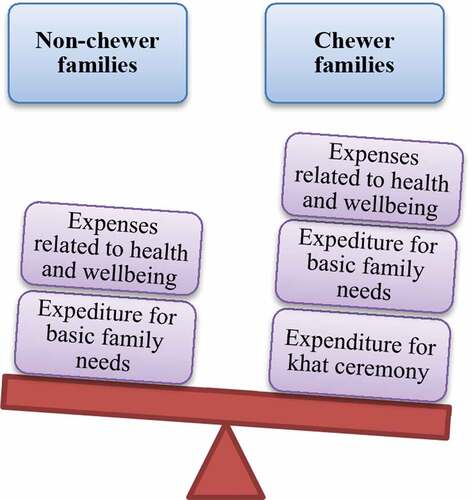

Consumer households spent less on basic family needs because they have another additional burden, the khat ceremony. Expenditure for the khat ceremony includes not only the expenses to buy khat but also the incenses (for good aroma during chewing), coke, peanut or sugar (used to reduce the bitter test of khat during chewing) and drink (some use it after chewing to reduce the effect khat and sleep) As we can see in the above Figure , the average expenditure on khat ceremony is greater than the expenditure for basic family needs. The mean expenditure for the khat ceremony is 75.8 ETB. Key informant participants indicated that there are consumers who spent money on khat while their children are hungry for food and had nothing to eat. Consumers also spent this amount of money on khat while their family members have no school utensils like pens and exercise books. For some consumers, especially for those who say “life for me is chewing” they give priority for khat than the basic needs of their family. In some families, this causes conflict in the household. When the household head chews khat while the family is suffering from a shortage of foods or other basic family needs, the other member of the family, especially the non-chewer wife, complains. As shown in the following Figure , khat is becoming an additional burden on the chewer families and this is creating argument, conflict and even divorce for some families, which is common according to my informants.

For instance, let us see the life of TM. She divorced her husband and abandoned her four children and lives on the street of Harar because of her khat consumption habit. She indicated that she tried many times to get rid of this habit but not successful. She said regretfully, “This is my fate, bad luck. Though I have four children I was lonely, homeless … my family hates me … there is a conflict with my family, they take care of my children and I also left them to try my best. They tried to imprison me for nine months to force me quite khat and shisha. But I said, ‘I cannot stop this until I die.’ Previously I was imprisoned for five months, but I did not stop, it is a habit! it is an addiction! I refused to stop, and I was still doing it.” She preferred khat more than her children and family.

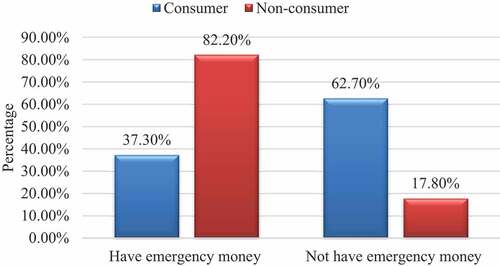

The following Figure shows another area where there is a great difference between consumer and non-consumer households in terms of caring for their family wellbeing. When only 75 (37.3%) of consumers have money saved for an emergency, it is 162 (82.2%) for non-consumers. “Emergency money” is money kept aside for emergency needs of the family only, like health problems. The absence of emergency money for hospitals and other natural or man-made disasters for the family makes the households of consumers extremely vulnerable and cannot afford quality health care since they have no money kept aside for this purpose.

3.4.1. The role of religion and difference in the management of income and expenditure in a family where either a husband or a Wife is non-chewer

To reduce bias and to do not look only from one perspective, the following data was gathered from non-consumers who live with chewers. These data were collected from twenty key informant interview participants. They are non-chewers who live with chewer family members and have a clear and neutral understanding of the impact of khat culture on their household. The information corroborates the issues presented above, the impact of khat culture on family wellbeing, particularly on family unity and happiness.

These data are presented basically depending on the participant’s religion. Because, religion plays a significant role in the perception toward khat, chewer family members, and the ceremonies involved. For instance, for the general question, “Do you see any problem related to khat in your family?”, only 2 (28.6%) of the Muslim respondents responded “yes” while 11 (84.6) of the Christian respondents responded “yes.” Similarly, while 5 (38.5%) of the Christian respondents indicated that they always relate the social and economic problems in their family to khat, only 1 (14.3%) of the Muslim respondents think in the same way. In addition, when 4 (57.1%) Muslims indicate that there is no khat related social and economic problems in their family, only 2 (15.4%) Christians believe in this way. However, 4 (30.8%) of the Christians rated the social and economic problems caused by khat in their household as worst and 12 (53.8%) as a medium, while it is only 1 (14.3%) and 2 (28.6%) for the Muslims, respectively. In addition, 4 Muslims consider khat as having no effect on their family (see Table in the Appendix).

These differences between Muslims and Christians families regarding their view toward khat are not by chance. Religion and religious practices either justify or abjure chewing khat and the ceremonial practices involved. Most of the Muslims in Harar believes that the Quran does not forbid chewing khat. Some even tried to quote from the religious books to justify their chewing. On the other hand, most of the non-consumer Christian families who live with chewer family members do not only believe the time and money spent on khat as a waste but also consider the act as a sin. Thus, they always challenge the consumer member/s, and this leads to arguments and hostility among family members. However, the non-consumer Muslims who live with the consumer family member support him/her during the chewing ceremony by sitting, drinking, and playing with him/her. In contrast to the non-consumer Christian wives who always quarrel with their consumer husband, some Muslim wives like to involve in the khat chewing ceremony of the consumer member. She, clean the house, buy khat, incense, and any other materials necessary for the ceremony and even sometimes chew with him.

The impact of the difference in religion was also observed during the interview schedule, some Christians were ashamed of their chewing habit. They do not want to talk about it because they believe it is a sin. As a result, they feel guilty for the money and time spent on chewing. On the other hand, Muslim consumer participants do not worry about their habit, whether it is good or bad. They like to talk about khat, they accept it as their culture and do not feel guilty for chewing.

The result from the key informant interview also shows that mostly it was non-consumer women (wives) who are the victims of living with the consumer family member, especially husband. Most of them are forced to see their husbands spending a large sum of money on khat ceremony rather than fulfilling the basic need of their children. From the key informant interviewees who voluntarily responded to the interview questions of the study, 12 (60%) of them were women (wives). They were eager to share information on the impact of khat culture in their families. They were looking for someone who listens to them, who could solve their problems. The majority of the women (wives) believe that there is a problem in their household that can be related to their khat chewer family members particularly when it comes to the management of income and expenditure of the household.

Regarding income management, 1 (8.3%) non-consumer females and 4 (50.0%) non-consumer males responded that their family manages their income and expenditure always transparently and openly. However, 5 (41.7%) females respondents indicated that their chewer household head sometimes tries to hide their incomes and expenditures from them. Moreover, 3 (25.0%) of female respondents (wives) revealed that their fellow consumers do not discuss with them at all about their incomes and expenditures. The table also shows that 8 (75.0%) of females or wives indicated that the problems related to khat in their household are always active (for more information see Table 3 on the Appendix). That is, each and every day, there will be an argument related to khat in the family. The clandestineness in the household between consumer household head and non-consumer members on handling household income and expenditure is a cause for most of the hostilities in the family, as the consumer always abuses money to consume khat at the expense of fulfilling the family’s basic needs.

4. Conclusions and recommendations

The data from interview schedules, observation, and key informant interview indicates that khat culture affects the wellbeing of a family. Consumers own lesser house materials that will increase the family’s wellbeing than non-consumer. Moreover, as the home materials and services become more basic and essential for life there are more differences between consumer and non-consumer households. A larger number of non-consumers own house residences than the consumer families. In addition, great differences were found on the quality and safety of the houses and their surroundings. Most of the houses of the consumer families are found to be small, have no fence, and less furnished. Khat also negatively affects family unity and happiness. Consumer families eat less within a day, most of them have no plan for tomorrow, have a less good time with their family, spent less on basic family need, and have no money saved for an emergency. The data also shows that relatively Muslim chewer families are more united and peaceful than Christian chewer families. Non-chewer females (wives) who live with chewer husbands believe that there is always a problem regarding handling family income. As a result, there are more quarrel, disagreement, and conflict in the families of chewers, caused by khat culture.

Khat culture affects the base of a community, a family, by disturbing its social and economic well-being and disturbing its unity. Everything starts from a family: prosperity, peace and stability, the culture of saving and economic success, on one hand, and failure, disturbance, instability, extravagance, and other evils, all starts at a family level. That was why Confucius said, “The strength of a nation derives from the integrity of the home [or family]”

The government and other concerned bodies need to regulate and device a mechanism to reduce the impact of khat on a family. The government can provide job opportunities for the consumers and for those whose lives depend on khat business. This is because as we advise one household to quit or minimize their dependence on khat, we are creating unemployment for the khat traders on the other hand. Health officials and health institutions can establish rehabilitation institutions (like Mekele University) particularly for those who say “life for me is chewing.” Establishing a voluntary foundation like Yemen’s Erada Foundation for Khat Free Nation is another important measure that needs to be taken by non-chewers. The members can demonstrate on the street around the khat market holding banners and posters to create awareness. They can show that life can be enjoyable and fun without khat. They can advocate a khat free wading, grieving, work or any other activities among their members. Lastly, religious institutions can also play a significant role, priests or shekhas can teach and help their khat chewer followers to minimize and stop chewing by presenting chewing as a sin.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zerihun Girma Gudata

Zerihun Girma studied MA in Sociology at Haramaya University. Currently he is serving as a Formative Research and Community Engagement Lead in Hararghe Health Research Partnersh, CHAMPS Ethiopia. He has published several researches works and participated in international and national conferences. He is interested to issues related to khat, ethnic interaction and history in east Africa. He used both qualitative and quantitative approaches in his studies.

Notes

1. Khat production and consumption is also expanding in the other parts of Ethiopia. Khat plantation and areas covered by khat is also increasing in Ethiopia. See, Tirusew Abere, Enyew Adgo and Selomon Afework, Trends of land use/cover change in Kecha-Laguna paired micro watersheds, Northwestern Ethiopia, Cogent Environmental Science (Abere et al., Citation2020), 6: 1801219

2. But there are limitations with this data: first it is only a one round observation; second, observations were made on a limited number of variables listed above. In addition, poverty may also affect most the variables discussed here. However, this study focuses on comparison of two groups of people who live under the same condition, i.e. poverty.

3. The data for this study gathered in the year 2017. some of the data are taken from Zerihun et al. (Citation2019).

References

- Abere, T., Adgo, E., & Afework, S. (2020). Trends of land use/cover change in Kecha- Laguna paired micro watersheds, Northwestern Ethiopia. Cogent Environmental Science, 6(1), 1801219. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311843.2020.1801219

- Abiye, G., Abebe, G., & Meseret, Y. (2007). Khat use and risky sexual behavior among youth in Asendabo Town, South Western Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 17(1), 1–27. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhs/article/view/146055

- Anderson, D., Susan, B., Degol, H., & Axel, K. (2007). The Khat Controversy: Stimulating the debate on drugs. Berg.

- Armstrong, G. E. (2008). Research note: Crime, chemicals, and culture: On the complexity of Khat. Journal of Drug Issues, 38(631), 631–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260803800212

- Beckerleg, S. (2009). Khat in East Africa: Taking women into or out of sex work? Substance Use & Misuse, 43(8–9), 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080801914139

- Burton, F. R. (1856). First footsteps in East Africa. Longman, Brown Green, and Longman.

- Carrier, N. (2005). ‘Miraa is cool’: The cultural importance of miraa (khat) for Tigania and Igembe youth in Kenya. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 17(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696850500448311

- Carrier, N. (2007). Kenyan Khat: The social life of a stimulant. Brill.

- Carrier, N., & Klantschnig, G. (2018). Quasilegality: Khat, cannabis and Africa’s drug laws. Third World Quarterly, 39(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1368383

- Cochrane, L., & O’Regan, D. (2016). Legal harvest and illegal trade: Trends, challenges and options in khat production in Ethiopia. International Journal of Drug Policy, 30(5), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.009

- Compendium of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2011) . Well-being indicators: Material living conditions. OECD.

- Cox, G., & Rampes, H. (2003). Adverse effects of khat: A review. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(6), 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.6.456

- Development Planning and Research Directorate, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. (2012). Ethiopia’s progress towards eradicating poverty: An interim report on poverty analysis study (2010/11).

- ECDD. (2006). Assessment of khat (Catha edulis Forsk) 34th ECDD/4.4.

- Ference, M. (2009). Book reviews. Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, Volume, 23(2), 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1086/SHAD23020181

- Gebissa, E. (2004). Leaf of Allah: Khat and agricultural transformation in Hararge, Ethiopia 1875–1991. James curry Ltd.

- Gebissa, E. (2009). Scourge of life or an economic lifeline? Public discourses on Khat (Catha edulis) in Ethiopia. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(6), 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701738950

- Gebissa, E. ( Ees.). (2010a). Taking the place of food: Khat in Ethiopia. Red Sea Press.

- Gebissa, E. (2010b). The culture of Khat. OGINA, Oromo arts in Diaspora. Retrieved April, 2013, from, http://www.ogina.org/issue5/issue5_culture_of_khat_ezekiel.html

- Gebissa, E. (2012). Khat: Is it more like coffee or cocaine? Criminalizing a commodity, targeting a community. Published Online on SciRes journal.

- Harrison, E. L., & Huntington, P. S. (Eds.). (2000). Culture matters: How values shape human progress. Basic books.

- Hassan, A. N., Gunaid, A. A., & Murray-Lyon, I. M. (2007). Khat (Catha edulis): Health aspects of Khat Chewing. Eastern MediterraneanV Healthy Journal, 13(3), 706-718. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/117302

- Havell, C. (2004). Khat use in Somali, Ethiopian and Yemeni communities in England: Issues and solutions. A report by Turning Point.

- Inglehart, R., & Baker, E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657288

- McKeown, K., Pratschke, J., & Haase, T. (2003). Family well-being: What makes a difference? Report to The Céifin Centre: Insights and initiatives for a changing society, Town Hall, Shannon, County Clare. Kieran McKeown Limited.

- Nakajima, M., Dokam, A., Saem, N. K., Alsoofi, M., & Al’Absi, M. (2016). Correlates of Concurrent Khat and tobacco use in Yemen. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(12), 1535–1541. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1188950

- Njoh, J. A. (2006). Tradition, culture and development in Africa: Historical lessons for modern development planning. Ashgate Publishing Company.

- Rita Annoni, M., & Riaz, K. (2009). Khat Use: Lifestyle or Addiction? Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 41(1), 1–10

- Smits, J., & Steendijk, R. (2013). The International Wealth Index (IWI). NiCE Working Paper, 2, 12–107. http://www.ru.nl/nice/workingpapers

- Solomon, T., Charlotte, H., Atalay, A., Lars, J., & Teshome, S. (2011). Khat chewing in persons with severe mental illness in Ethiopia: A qualitative study exploring perspectives of patients and caregivers. Transcultural Psychiatry, 48(4), 455–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461511408494

- Sultan, H. T. (2011). Harari people regional state: Programme of plan on adaption to climate change. Environmental Protection Authority of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

- Wai-Poi, M., Spilerman, S., & Torche, F. (2008). ‘Economic well-being: Concepts and measurement with asset data’ NYU population centre Working Paper, 8.

- Weber, M. (1930). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. George Allen & Unwin ltd.

- Wolf, V. M. (2013, April 30). Chewing Khat increasingly popular among Ethiopians. Reporter for the Voice of America.

- Wuletaw, M. (2018). Public discourse on Khat (Catha edulis) production in Ethiopia: Review. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 10(10), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.5897/JAERD2018.0984

- Zerihun, G. (2019). A historical analysis of Magaalaa Guddoo (Gidir Magaalaa) market centre in Harar City (1938–1991). East African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 3(1), 63–86. http://ejol.aau.edu.et/index.php/EAJSSH/article/view/1590.

- Zerihun, G., Cochrane, L., & Imana, G. (2019). An assessment of khat consumption habit and its linkage to household economies and work culture: The case of Harar city. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0224606. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224606

Appendix

Table 1. The houses and its surroundings of chewer and non-chewers

Table 2. Data from Non-chewers who live with Chewers

Table 3. Management of Income and Expenditure by a Household where either Husband or Wife is non-chewer, Data from a non-chewer family member

Questions for Interview Schedule, key informant interview, and Observation Checklists

a. Questions for both Chewers and Non-chewers

1.

2. Age ____________

3. Sex ____________

4. Marital status

Married

Living together

Widowed

Divorced

Separated

Single (never married)

5. Religion _________________

Muslim

Orthodox Christian

Protestant

Jehovah’s witnesses

Other ____________________

6. Ethnic group _____________________

Amhara

Oromo

Adari

Guraghe

Tigre

Somali

SNN

7. How many family members do you have? __________________

8. Level of education.

Not educated

Less-educated (Grade 1 to Grade 7)

Educated (Grade 8 to Grade 12)

Well educated (12+ and University or college graduate)

9. Do you have a child(ren) who are not sent to school or kindergarten?

Yes No

10. If Yes, Why _____________________________________________________________________

11. Did your child(ren) go without each of the following things in the last month because of a shortage of money?

Clothes Yes No

Shoes Yes No

Bag Yes No

Food Yes No

Pen/pencil Yes No

Exercise book Yes No

12. Does your household own this accommodation?

Television Yes No

Telephone Yes No

Computer Yes No

Internet Yes No

Pipe Water Yes No

Table, Chair Yes No

Water tower Yes No

Boiler Yes No

Bed Yes No

Stove Yes No

Radio Yes No

Refrigerator Yes No

Sofa (Arabian Majlis) Yes No

Locker Yes No

Toilet Yes No

13. How often do you eat within a day?

Once

Twice

Three times

Four times

More than four

14. Occupation or any sources of income for the entire household?

Employed

Underemployed

Unemployed

15. Can you give a rough estimate of your household income per month? ________

16. On average for how many hours do you work within a day? ____________

17. Do you have any saved money for emergency need, such as health problem? Yes _________No________

18. If “No” why? ______________________________If “Yes” how much?____________

19. On the workday, mostly at what time do you leave the workplace for lunch?

Ten (4)

Eleven (5)

Twelve (6)

One (7)

20. After a lunch break, mostly at what time do you return to work?

Two (8)

Three (9)

Four (10)

21. Does your household own its accommodation (home residence) or do you rent it?

Owned outright

Rent from the local authority

Rent from the housing association

Rent from a private owner

Other

22. Do you have a bank account?

Yes No

23. If “No” why? ______________________________________

24. Can you give a rough estimate of your household expenditure on daily family needs, like food and drink? _______________________

25. How often do you plan yours or your family’s life?

Each day

Once a week

Once a month

Once a year

No plan

b. Questions only for Chewers families (after identifying chewer)

26. Is there anyone who chew khat in your family?

Yes No

27. If Yes who?

Father

Mother and father

Son/daughter

Mother

The whole family

28. How long since you/he/she have started chewing? ___________

29. Why you chew khat?

To help me pray

To work effectively

To resist social exclusion

For entertainment

To focus on reading

Other ______________

30. How often do you chew?

Three times a day

Twice a day

Once a day

Three times a week

Two times a week

Once a week

31. What happened to you if you don’t chew khat in the above specified periods?

Cannot work well

Cannot treat others well

Cannot be happy

I isolate myself

I fight with others

Nothing happens

32. How long do you stay without chewing khat?

A day

Two day

Three day

Four day

A week

A month

33. If you badly need khat (in Harara) but have no money, what would you do? (rate the following actions)

I borrow and buy

I take money reserved for food

I start selling my own household materials

I take others money without permission

I beg and join others

I will tolerate till I find money

Do you use other substances beside khat:

Yes No

34. If Yes, which one?

Cigarette

Alcohol

Shisha,

Others

35. After Barcha drinking is

Essential

Desirable

Not necessarily

36. Which of the following is essential for the khat chewing ceremony and give a rough/average estimate of the cost of each material?

Khat_______________

Candle _____________

Soft drink___________

Alcohol_____________

Shisha______________

Incense_____________

Peanuts ____________

Barcha house________

37. On average how long you spent on chewing, in one session? (in minute or hours)_____

38. What would you personally find really difficult to give up if money was tight?

The need of your son/daughter

Your wife’s need

Khat

Food

Smoking

Drinking (alcohol)

39. How often do you have a good time with your family, other than for chewing, just to enjoy yourself with them?

Once a day

Once a week

Twice a month

Once a month

Once a year

No such thing

c. Observation Checklist (Can also be asked)

Are khat chewers better off than non-chewers, in having better houses? See

Type of the house

Width of the house

How many rooms it has?

From what the house is made?

Fence?

Environment?

Condition of the room

Condition of the outside campus

Condition of the chairs and table

Condition of the informant

Condition of the child/ren

Wear better clothes and shoes?

Quality of the shoes the informant has

Quality of the shoes the informant’s child/ren has

Quality of the closes the informant has

Quality of the clothes the informant’s child/ren has

d. Questions for key Informant Interview (for Non-chewers in the Family)

1. Sex________________ Religion ____________________

2. Is there any other things that we didn’t hear about khat and its impact on your family? _____________________________________________________________________

3. How do you rate or see the effect of khat chewing on your family member?

Worst

Medium

No effect

4. Do you experience any problem related to your khat chewer family members?

Yes No

5. If “Yes”, What? Explain ______________________________________________________

6. Any house conflict or argument caused by khat chewing in your family?

Yes No

7. How you relate the problem (economic or social) in your house to khat?

Always

Sometimes

Rarely

Not at all

8. If yes, what was it?________________________________________________________

9. Was it resolved or continued?_________________________________________________

10. People organise their household finances in different ways. How do you and your partner (the chewer) organize your income and expenditure?