?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Most indigenous populations in developing counties are burdened by limited health literacy, and validated, cultural and language-specific health literacy measures are not available for them. This article describes a phased approach that was followed to validate the Sesotho Health Literacy Test (SHLT). Data from 474 patients and high school learners were used to test understandability of SHLT items, item response, factor analysis, and convergent and predictive validity of test items. SHLT items showed good internal reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.77). Exploratory structural equation modelling showed acceptable fit as the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR = 0.04). The convergent validity of the SHLT was good, indicated by people with more years of formal schooling scoring higher on the SHLT. The predictive validity of the SHLT was good, as those participants who scored high on the SHLT never had reading assistance. The test can be used by practitioners before they implement health promotion.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Validated, cultural and language-specific health literacy measures are not readily available for most indigenous populations in developing counties. This article presents how researchers went about to validate a health literacy test of an indigenous population. Various routes can be followed to validate tests, with a generic route presented here. This user-friendly, general health literacy test could provide local governments, community groups and health care providers with valuable information on the unique health needs of an indigenous population group. Validated health literacy tests may assist in improving the health outcome of populations..

1. Introduction

Health literacy is an important construct in healthcare, and requires rigorous measurement. It is unfortunate that there are limited validated health literacy measures, especially non-English tools. These tools are often used for ethnic minorities in developed countries (Nguyen et al., Citation2015). Although minority groups in these countries are considered high-risk populations for limited health literacy, this is not the case in developing countries, where the majority of the indigenous populations are burdened by limited health literacy (Dowse, Citation2016).

Indigenous populations face specific and unique health literacy challenges (Crengle et al., Citation2014). Health-literacy-based data for the Basotho, an indigenous population group in South Africa, speaking Sesotho, are lacking. Although only 8% of the households speak Sesotho as their home language in South Africa, within the Free State province of the country, the majority (72%) of the population is Sesotho home language speakers. Almost two-thirds of this group makes use of public health services (Statistics South Africa (StatsSA), Citation2016). It is therefore essential to have a context-specific, validated health literacy test available to better understand health literacy in the province.

The tendency to translate existing health literacy tools originating from developed countries for use in developing countries posed to be ineffective in South Africa (Dowse et al., Citation2010; Hunt et al., Citation2008). The developed Sesotho Health Literacy Test (SHLT) is contextually relevant (Reid et al., Citation2019). The Basotho can therefore only benefit from the undisputed positive health outcomes associated with their practitioners or themselves knowing their health literacy status, when a validated health literacy tool is available.

Various studies reported by literature conclude that low health literacy negatively affects health outcomes, healthcare access, and hospitalizations/emergency care, and leads to higher healthcare costs (CitationBerkman et al.,; Heijmans et al., Citation2015). The health literacy profile of the Basotho is likely to be similar to population groups in other developing countries, given similar inequalities in health and education observed by practitioners.

Valid and reliable health literacy measures are essential for identifying such high-risk populations (Chakalakal et al., Citation2017). In validating health literacy measures, the challenge lies in the variance as to how the concept of health literacy is operationalized into a measurable construct (Haun et al., Citation2014), due to the absence of a “gold standard” to measure health literacy (How, Citation2011). The theoretical foundation of the Sesotho Health Literacy Test (SHLT) (Reid et al., Citation2019) integrated the health definition of Dodson et al. (Citation2015) in its framework:

Health literacy refers to the personal characteristics and social resources needed for individuals and communities to access, understand, appraise and use information and services to make decisions about health. Health literacy includes the capacity to communicate, assert and enact these decisions.

The bottom line is that the majority of validated health literacy measures emanate from developed countries; in turn, validated cultural and language-specific health literacy measures for indigenous groups in developing countries are not widely available. The study aimed to validate the SHLT.

2. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study followed a phased approach to, first, evaluate the understandability of the SHLT by patients (Phase 1) and, second, describe item response, factor analysis, and convergent and predictive validity of the SHLT (Phase 2). The phased approach was guided by the generic methodology proposed by Tsai et al. (Citation2011). As it is a recognized practice (Bollweg et al., Citation2020), it is paramount that items are evaluated for understandability prior to further rigorous validity testing.

2.1. Phase 1—Understandability of the SHLT

2.1.1. Sample

A convenience sample consisted of 15 patients at a primary health care (PHC) clinic in the Free State province of South Africa. This PHC clinic was conveniently sampled due to its accessibility and availability of adult participants speaking Sesotho as their first language. All participants provided written consent. Ethical approval of the research project was obtained from the … … … … . (UFS-HSD2017/1526).

2.1.2. Data collection

A trained, Sesotho-speaking fieldworker conducted cognitive interviews, in Sesotho, at the PHC clinic. In a private setting at the clinic, participants were instructed to think aloud as they explained their understanding of the SHLT items (N = 47), which were posed as questions. This process created the opportunity for the authors to assess participants’ understanding of the test items. Each Sesotho interview was audio-recorded and transcribed, after which translation from Sesotho to English, and back-translation to Sesotho was done.

2.2. Phase 2—Item response, factor analysis, convergent and predictive validity

2.2.1. Sample

The sample in Phase 2 consisted of two Sesotho first-language-speaking population groups, namely, adult patients and Grade 11/12 learners. All participants provided written consent prior to participation in the study.

A convenience sample of 330 patients from the PHC clinic completed the SHLT. On average, 350 patients are seen per day at the clinic.

A convenience sample of 144 Grade 11/12 learners at high schools in two Free State towns also completed the SHLT. These schools had 187 Grade 11/12 learners enrolled in 2018.

2.2.2. Data collection

Trained Sesotho-speaking fieldworkers used structured interviews (n = 474) to complete the SHLT (N = 47 items) individually with each patient or learner in a pre-arranged private setting at the clinic or high school.

In addition to completing the SHLT, all patients and learners answered questions relating to demographic descriptions, as well as their health knowledge, health status, reading habits and reading assistance (see Supplemental material: Additional questionnaire). Health knowledge was measured by means of 10 general health questions, which measured the percentage of knowledge, which was calculated by summing the correct responses to 10 general health questions (see Questions 11 to 20). The participants indicated their health status for the last 6 months (Question 8). A Likert scale (always, sometimes, never) was used to enquire about reading habits (Question 10) by asking participants to indicate health information sources and interval of usage. Participants were asked to identify any need for help with reading health information (Question 11). The highest qualification indicated general schooling (Question 5).

3. Analysis

3.1. Phase 1—Understandability of SHLT

The author (MR) assessed the understandability of SHLT items during discussions with the fieldworker. An item was deemed to be understandable if the participant correctly interpreted the question. Both the Sesotho and English versions of the scripts were taken into consideration.

3.2. Phase 2—Item response, factor analysis, convergent and predictive validity

Descriptive statistics, namely, frequencies and percentages for categorical data, and medians and percentiles for continuous data, were calculated per group. The groups were compared by means of the appropriate statistical test. Item analysis was done to determine which items had slopes of less than 0.5. The relatively small sample size (in comparison to the number of items) resulted in Heywood cases in the factor analysis; the analysis was simplified to a principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The ideal number of factors was determined using a scree plot. Any items not loading well on the final factors were discarded and the remaining items were classified into factors based on the communal item content. Exploratory factor analysis was done. The internal reliability of the measurement instrument was described by means of Cronbach alpha. The convergent validity of the SHLT was described by means of the number of years of formal schooling, as an indicator of general literacy. Two variables, namely, health knowledge and reading assistance, were used to describe the predictive validity by means of descriptive statistics (Tsai et al., Citation2011).

4. Results

depicts the demographic profile of participants from both phases.

Table 1. Demographic profile of participants from phase 1 and phase 2

4.1. Phase 1—Understandability of SHLT

Assessment of understandability of SHLT items (N = 47) led to four questions being changed and seven questions being omitted. The Sesotho translations of nine items were simplified further. The SHLT questionnaire entered Phase 2 of the study with 40 items. (See supplemental material: 40 Item SHLT English questionnaire.)

4.2. Phase 2—Item response, factor analysis, convergent and predictive validity

Item response analysis was done to determine whether the item loaded well onto the latent construct. presents the difficulty and slope per SHLT item (n = 40).

Table 2. Difficulty and slope per SHLT item (n = 40)

Only 10 items, highlighted in bold in , had a slope larger than 0.5. A slope below 0.5 was considered the sign of a poor indicator (An & Yung, Citation2014; Kunicki et al., Citation2018). Items that have large slope values are more informative than items with low slope values. Three different levels of difficulty were also included within the 10 items remaining. The South African health clinic patient typically has to wait for hours before they can be seen by a healthcare professional; hence, the scale needs to identify a patient’s health literacy quickly (Kelly et al., Citation2019).

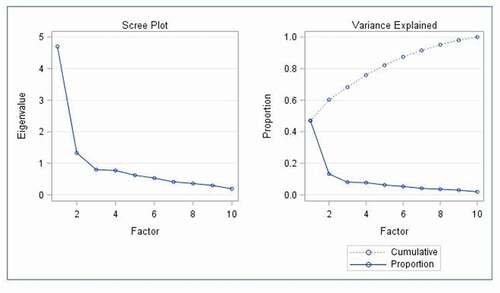

On the basis of the estimated discrimination and difficulty, 30 of the 40 items appeared to provide redundant information in terms of discrimination and difficulty. For these 10 items, the scree plot indicated two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 and these two factors declared 60.2% of the variance. See . Only the first two factors had eigenvalues higher than 1.0; therefore, only they were included as also seen in the Scree plot (Cattell, Citation1966).

The factor names were derived from the health literacy definition of Dodson et al. (Citation2015) where appraisal and understanding of information were highlighted. Factor 1 was classified as appraising information, and included Questions 8, 9, 11, 17, 18 and 20. Factor 2 was classified as understanding information, and referred to Questions 13, 15.2, 22 and 25.

Exploratory structural equation modelling showed acceptable fit, as the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) was below 0.08, SRMR = 0.04 (Hu & Bentley, Citation1999). The chi-square test was significant (45) = 871.5514, p < 0.001, though chi-square tests tend to be sensitive and a significant result does not necessarily indicate poor fit (Harlow, Citation2014; McIntosh, Citation2007). The internal reliability was acceptable, as the Cronbach alpha value for the SHLT was 0.77 (DeVellis, 2011), and the Cronbach alpha per factor was 0.78 for Appraising and 0.83 for Understanding.

Correct responses to questions were scored as one, and the total score was calculated as the sum of the 10 questions (see supplemental material: 10-item SHLT). The total score of the remaining 10 questions had a median of 6 (interquartile range 4–8) and a minimum 0 and maximum of 10. The two factors’ summary statistics are as follows: Appraising information had a median of 3 (interquartile range of 1–5) and a range of 0–6, the factor Understanding information had a median of 3 (interquartile range of 2–4) and a range of 0–4.

shows the association between the two identified factors and years of schooling as well as knowledge and reading assistance. These results also confirm the scale’s ability to distinguish regarding the level of literacy.

Table 3. Factors’ association regarding year of schooling, knowledge and reading assistance (n = 474)

Comparing scores for appraisal of information for 9 and 10 years of schooling respectively showed no difference (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.10); however, different years of schooling had corresponding differences for understanding information (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.01). The number of years of formal schooling is, thus, an indicator of general literacy (convergent validity of the SHLT), as participants who had more years of formal schooling scored higher on the SHLT. The predictive validity of the SHLT was good, as participants with high scores on the SHLT never had reading assistance.

The 10 questions of the SHLT were classified into three groups, namely less than 6 was low (n = 213, 44.9%), 6–7 was moderate (n = 101, 21.3%) and 8 and higher was high (n = 160, 33.8%). These three groups referred to the total score of the 10 questions being classified as low, moderate and high.

5. Discussion

We developed the SHLT (Reid et al., Citation2019), using the proposed generic methodology described by Tsai et al. (Citation2011). We further followed these authors’ recommendation to exercise cultural and contextual sensitivity when developing a health literacy test, by carefully selecting experts and consumers who are familiar with the local healthcare system. However, health literacy test development is incomplete without focusing on the validation of a test, as presented in the current paper.

Various methodologies are promoted to follow when validating developed tests. The wide application of the validation process proposed by Lee and Tsai (Citation2015) to measure health literacy in Manderin Chinese in Taiwan assisted us in validating the SHLT. Boateng et al. (Citation2018) offered specific steps, some coinciding with those of Lee and Tsai, to be followed as part of a scale evaluation. The steps include tests of dimensionality, reliability and of validity. Carpenter (2018) also proposed a detailed step-wise process to assist researchers to follow best practices related to scale development and validation. Again similarities can be found between steps proposed by Lee and Tsai (Citation2015) and Carpenter (2018). We have also made use of cognitive interviews to evaluate item wording, determined the number of factors using the scree test and presented eigenvalues for factors.

The phased approach followed by us to initially evaluate the understandability of the SHLT items is common practice when testing the validity of health literacy tests (Bollweg et al Citation2020). Cognitive interviews were also used in the development of the Health Insurance Literacy Measure (HILM) (Paez et al., Citation2014) and the Cancer Health Literacy test (Dumenci et al., Citation2014).

The final phase applying item response theory is furthermore an acceptable practice to evaluate patient outcome (Nguyen et al., Citation2014), used in both the High Blood Pressure Health Literacy Scale (Kim et al., Citation2012) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Osborne et al., Citation2013). Item response models contribute in improving score accuracy and also prioritize saving on test administration by using only the discriminative items (An & Yung, Citation2014). It allowed the initial 47 items of the SHLT to be reduced to only 10 items. Deciding on the methodology to follow when validating a test, is but an aspect to consider.

Fundamental to validating a health literacy test is the understanding of the concept of health literacy. The concept of clarification endorsed by the authors, provided by Dodson et al. (Citation2015) when developing the SHLT, highlighted four essential health literacy competencies: accessing, understanding, appraising and applying health-related information. During the validation of the SHLT, the scree plot indicated only two factors, namely appraising and understanding of information. In spite of the SHLT being developed and validated as a general health literacy test within the context of a developing country, a health literacy test for colorectal cancer screening validated in the Netherlands, confirmed comprehension, application, communication and appraisal as separate factors (Woudstra et al., Citation2019). These factors align to the health literacy competencies validated in the SHLT.

Completing the SHLT therefore requires a range of literacy skills to determine whether individuals can accomplish health-related tasks critical for health maintenance, prevent and manage disease and gain access to medical services. The tasks included in the test items are based on actual situations that Basotho patients would encounter in public healthcare facilities in the Free State. The item formats vary, to allow for the assessment of reading, comprehension and numeracy skills. The structure of the SHLT therefore acknowledges the need for developing countries to include a variety of questions in health literacy tests, not only relying on reading literacy and numeracy (Dowse, Citation2016).

Limitations to be acknowledged include convenience sampling, which may have generated selection bias. However, sampling a population with diversity related to age and healthcare experiences supported the predictive validity of the SHLT. Since a similar socio-economic background can be expected among members of the sample, testing in populations that are more diverse could benefit validity testing.

6. Conclusion

This paper presented the process followed to validate a Sesotho Health Literacy Test for assessing health literacy in the Sesotho language, an indigenous South African language. Adding a mileu-appropriate health literacy test does not only add to empirical data in this under-researched field in Africa but will assist health practitioners and patients alike to understand the influence of health literacy on health outcome. This user-friendly, general health literacy test could therefore provide local governments, community groups and health practitioners with valuable information on the unique health needs of the Sesotho population in the South African context.

The analysis shows the SHLT has good reliability and validity, and demonstrates that the methodology reported is sound and widely applicable. The 10-item SHLT is suitable for rapidly appraising the health literacy of the almost 4 million people in the Free State province who speak Sesotho as their first language. It creates a platform for gaining a better understanding of health literacy in this indigenous population group. Improvement in health status and healthcare-seeking behavior by this population may become a reality. Future studies are needed to understand its performance in larger clinical settings better.

The generic methodology (Tsai et al., Citation2011) followed allows the phased approach in development and validation of health literacy tools for other indigenous languages worldwide to be explored. Investing in contextual and mileu-appropriate health literacy tools for indigenous population groups cannot be overemphasized.

Supplemental data for this article (Additional questionnaire; 40-item SHLT English questionnaire; 10-item SHLT) can be accessed on the publisher’s website at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.917744

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and learners for their participation in this study.

Declaration of interest statement/Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marianne Reid

Dr M Reid is the lead researcher in Health Communication within the School of Nursing at the University of the Free State in South Africa. This inter-professional team of researchers focus on health dialogue between healthcare providers and patients diagnosed with chronic conditions. Research outputs include a health dialogue model for patients diagnosed with diabetes, a peer support model for diabetic patients and the use of traditional folk media when conveying health messages to specific indigenous language groups. A validated observational checklist of health dialogue elements assisted in creating a reliable communication skills assessment tool. mHealth interventions focused on supporting patients and caregivers. Since health literacy is poorly understood within developing countries, an indigenous health literacy test was development and validated. Research needs addressed by this team strengthen national and international efforts to increase risk perception by healthcare workers and patients alike and empower patients to improve their health outcomes.

References

- An, X., & Yung, Y. F. (2014). Item response theory: What it is and how you can use the IRT procedure to apply it. SAS Institute.

- Berkman, N. D., Sheridan, S. L., Donahue, K. E., Halpern, D. J., & Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals Internal Medicine, 155, 97–11. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Bollweg, T. M., Okan, O., Pinheiro, P., Bröder, J., Bruland, D., Freţian, A. M., Domanska, O. M., Jordan, S., & Bauer, U. (2020). Adapting the European health literacy survey for fourth- grade students in Germany: Questionnaire development and qualitative pretest. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 4(2), e119–e128. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20200326-01

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1, 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

- Chakalakal, R. J., Venkatraman, S., White, R. O., Kripalani, S., Rothman, R., & Wallston, K. (2017). Validating health literacy and numeracy measures in minority groups. Health Literacy Research and Practice, 1(2), e23–e30. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20170329-01

- Crengle, S., Smylie, J., Kelaher, M., Lambert, M., Reid, S., Luke, J., & Harwood, M. (2014). Cardiovascular disease medication health literacy among indigenous peoples: Design and protocol of an intervention trial in Indigenous primary care services. BMC Public Health, 14, 714. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-714

- DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications (Vol. 26, Applied Social Research Methods Series). Sage.

- Dodson, S., Good, S., & Osborne, R. H. (Eds.). (2015). Health literacy toolkit for low- and middle-income countries: A series of information sheets to empower communities and strengthen health systems. World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/205244

- Dowse, R. (2016). The limitations of current health literacy measures for use in developing countries. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 9, 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2016.1147742

- Dowse, R., Lecoko, L., & Ehlers, M. S. (2010). Applicability of the REALM health literacy test to an English second-language South African population. Pharmacy World & Science, 32(4), 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9392-y

- Dumenci, L., Matsuyama, R., Riddle, D. L., Cartwright, L. A., Perera, R. A., Chung, H., & Siminoff, L. A. (2014). Measurement of cancer health literacy and identification of patients with limited cancer health literacy. Journal of Health Communication, 19, 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.943377

- Harlow, L. L. (2014). The essence of multivariate thinking: Basic themes and methods. Routledge.

- Haun, J. N., Valerio, M. A., McCormack, L. A., Sørensen, K., & Paasche-Orlow, M. K. (2014). Health literacy measurement: An inventory and descriptive summary of 51 instruments. Journal of Health Communication, 19(Suppl.2), 302–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.936571

- Heijmans, M., Waverijn, G., Rademakers, J., Van der Vaart, R., & Rijken, M. (2015). Functional, communicative and critical health literacy of chronic disease patients and their importance of self-management. Patient Education and Counselling, 98, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.006

- How, C. H. (2011). A review of health literacy: Problem, tools and interventions. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 20(2), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/201010581102000209

- Hu, L., & Bentley, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hunt, S., Dowse, R., & La Rose, C. (2008). Health literacy assessment: Relexicalising a US test for a South African population. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 26(2), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.2989/SALALS.2008.26.2.7.571

- Kelly, G., Mrengqwa, L., & Geffen, L. (2019). “They don’t care about us”: Older people’s experiences of primary healthcare in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatric, 19, 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1116-0

- Kim, M. T., Song, H.-J., song, Y., Nam, S., Nguyen, T. H., Lee, H.-C. B., & Kim, K. B. (2012). Development and validation of the High Blood Pressure-Focused Health Literacy Scale. Patient Education Counseling, 87(2), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.09.00

- Kunicki, Z. J., Schick, M. R., Spillane, N. S., & Harlow, L. L. (2018). Creation and validation of the barriers to alcohol reduction (BAR) scale using classical test theory and item response theory. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 7, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.01.004

- Lee, S.-Y. D., & Tsai, T. I. (2015). Health literacy assessment. In D. Y. Kim & J. W. Dearing (Eds.), Health communication research measures (pp. 57–64). Peter Lang.

- McIntosh, C. N. (2007). Rethinking fit assessment in structural equation modelling: A commentary and elaboration on Barrett. Personality and Individual Difference, 42, 859–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.020

- Nguyen, T. H., Han, H., Kim, M. T., & Chan, K. S. (2014). An Introduction to item response theory for patient-reported outcome measurement.. Patient, 7(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-013-0041-0

- Nguyen, T. H., Paasche-Orlow, M. K., Kim, M. T., Han, H.-R., & Chan, K. S. (2015). Modern measurement approaches to health literacy scale development and refinement: Overview, current uses, and next steps. Journal of Health Communication, 20, 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1073408

- Osborne, R. H., Batterham, R. W., Elsworth, G. R., Hawkins, M., & Buchbinder, R. (2013). The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health, 13, 658. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-658

- Paez, K. A., Mallerly, C. J., Noel, H., Pugliese, C., Mcsorley, V. W., & Lucado, J. L. (2014). Development of the health insurance literacy measure (HILM): Conceptualizing and measuring consumer ability to choose and use private health insurance. Journal of Health Communication, 19, 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.936568

- Reid, M., Nel, M., & Janse van Rensburg, E. (2019). Development of a Sesotho health literacy test in a South African context. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 11(1), a1853. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1853

- Statistics South Africa (StatsSA). General household survey 2016. http://www.stassa.gov.za

- Tsai, T.-I., Lee, S.-Y. D., Tsai, Y.-W., & Kuo, K. N. (2011). Methodology and validation of health literacy scale development in Taiwan. Journal of Health Communication, 16(1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2010.529488

- Woudstra, A. J., Smets, E. M. A., Galenkamp, H., & Fransen, M. P. (2019). Validation of health literacy domains for informed decision making about colorectal cancer screening using classical test theory and item response theory. Patient Education and Counseling, 102, 2335–2343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.09.016