Abstract

The Vedic literature constitutes the fulcrum of Sanskrit literature and is repositories of some fundamental concepts of human rights. This manuscript endeavors to decode the tenets of human rights concealed in the Vedic texts. It further endeavors to view a connection between archaic Vedic literature and human rights and approaches the subject of human rights from the perspectives of Vedic texts. As an articulated concept, human rights have distinct western inception though the elements that constitute the concept postulate different cultural forms and are found in sundry civilizations of which one is Vedic civilization. The Vedic rights are certainly not akin to modern-day human rights but then it would not be feasible to expect much from the texts that are approximately 3500 to 4000 years old. Though the Vedic literature vividly resonates with some rudimentary conceptions of human rights, the relationship between Vedic literature and human rights is not entirely smooth and tension free. This manuscript withal fixates on the incongruities subsisting between Vedic literature and human rights.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Vedic literature is the foundation of Sanskrit literature and is a source of many basic principles of human rights. This manuscript aims to decipher the tenets of human rights hidden in the Vedic scriptures. It also attempts to see a link between archaic Vedic literature and human rights and, from the viewpoint of Vedic texts, addresses the issue of human rights. While certain rudimentary concepts of human rights echo vividly in Vedic literature, the connection between Vedic literature and human rights is not completely smooth and free of conflict. This manuscript also reflects on the incongruities that exist between Vedic literature and human rights.

1. Introduction

While the high standards of universal human rights were laid down in the modern period during the renaissance era, there is no obnubilating that some aspects of human rights have been revered by virtually all the leading cultures. For instance, in Archaic West Asia, the Urukagina reforms of Lagash (2350 B.C.), the Ur-Nammu’s Neo-Sumerian Code (2050 B.C.), and the Hammurabi Code (1780 B.C.) talk about laws on the liberation of girls, women’s rights, men’s rights, and slave rights. Similarly, ancient Egypt’s Northeast African culture promoting basic human rights is ostensible from the decisions of Pharaoh Bocchoris (725–720 B.C.), who fortified equal rights, suppressed debt confinement, and reformed land transfer rules. The Achaemenid Persian king Cyrus the Great’s, Cyrus Cylinder (539 B.C.) sanctioning the Jews to return from their Babylonian bondage to their homeland is viewed by some as a charter of independence to exercise one’s religion without any oppression or coercive conversion. Some philomaths however, term the Cyrus cylinder by the Pahlavi regime as military propaganda (Kuhrt, Citation1983). Likewise, in the early poleis of ancient Greece, one could trace the notion of democracy where all people had the liberation to verbalize and vote in political assembly (Shelton, Citation2007). The Laws of the Twelve Tables, inscribed on twelve bronze tablets engendered in ancient Rome in 451 and 450 B.C., promulgate legislation which composed the substructure of Roman laws and founded the “privilegia ne irroganto” concept, designating that “privileges are not to be enforced”. Similarly, ius or jus was a privilege in ancient Rome that people received solely by dint of their citizenship. As formulated in the Western European tradition, the concept of Roman ius is a precursor to the term called “right”. The term “justice” is withal extracted concretely from ius.

It is further evident that in one way or another all the world’s main religions strive to talk to others on the issue of human rights and responsibility(Lauren, Citation2013). For instance, when we optically discern Islam, we find that as a reformer, Prophet Muhammad denounced the lamentable activities like female infanticide, abuse of the poor and weak, usury, assassination, fake communications, and purloining, prevalent among the pagan Arabs. Muhammad is withal credited with inditing Medina’s Constitution in 622 A.D. that placed within the fold of one community-the Ummah-the Muslim, Jewish and pagan cultures of Medina. Similarly, Buddhism urge to renounce caste and rank disparities in favor of uniform fraternity and liberation; Judaism appeals on the ritual purity of human endowed with merit and equality; Confucianism request on, “don’t force on someone, something you don’t do yourself”, Christianity, claiming golden rules saying, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” and Hinduism, accentuating on non-violence, the consequentiality of obligation, commiseration towards poor and incapacitated; portray the elements of human rights intrinsical in religious texts of all major religions of the world.

Philosophers across the globe, have always exhibited a profound interest in the nature, theory, magnification, and development of human rights. However, it is widely accepted that until the seventeenth century, the convivial noetic conceptions outside Europe and social and licit phrenic conceptions inside Europe accentuated more on obligations rather than general human rights (Kamenka & TAY, Citation1984). The Vedic society was mainly an obligation-predicated society and most of the rights that resonate in the Vedic literature are mainly abstract. This paper will endeavor to decode the abstract rights concealed in the Vedic literature to understand the phrenic conceptions and philosophy of Vedic people on human rights. It is paramount in the sense that the Vedic people constituted a society that engendered the first kenned literature of mankind called Vedic literature. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which affirms the dignity and rights of all humans is in accord and affirmation to the dignity, obligations, and rights mentioned in archaic Vedic literature. There are hymns in Vedic literature that are in consonance with the UDHR and hence the concept of human rights appears to be indirectly ostensible, pervasive, and acceptable in the Vedic society. However, the main question is not so much whether Vedic literature mentions any particular human rights but rather whether the conception of human rights finds any philosophical justification within the boundary of Vedic vision of individual or social good. The manuscript endeavors to decipher the resonances and dissonances cognate to transtemporal human rights concealed in the Vedic literature indited in Sanskrit. The manuscript will further endeavor to explore the philosophical justification of the conception of human rights within the vision of Vedic literature. The first part of the manuscript deals with the rudimental features of human rights. The second part expounds on the genealogy of Vedic literature. The third part will fixate on the resonances of transtemporal human rights in Vedic literature. And the fourth and final part of the manuscript will address the issues of potential dissonances between the conception of modern human rights and the Vedic concept of human rights.

2. An overview of human rights and human rights literature

The concept of modern human rights draws heavily from the natural laws which were a parameter for judging all the laws. The natural laws acted as a check and balance and restrained the extortionate powers of the state and ascendant entities. These natural laws further translate into natural rights. In the 17th century, John Locke defined natural rights as the right to “life, liberty, and property”. A century later Thomas Jefferson defined natural rights as the right to “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness” (Heywood, Citation1994). Natural rights didn’t subsist simply as moral claims but were considered to reflect the most fundamental inner human drives. Moral rights are perceived as independent of legal rights and have been in subsistence afore legal rights. Moral rights primarily arise due to ethical obligations. Philosophers like Bentham consider moral rights as nonsense upon stilts i.e. the silliest kind of preposterousness (Bentham et al., Citation2012; Waldron- Citation1987) and perceives legal rights as the only true rights (Bowring, Citation1843; Hart, Citation1973) whereas other philomaths advocate for a more comprehensive view which includes moral rights as well (Renteln, Citation1988). Marx considers every right as the right of inequality as it applies an equal standard to an unequal individual (Heywood, Citation1994). Feinberg has identified rights as a claim to something against someone (Feinberg, Citation1973) whereas for McCloskey, rights are an entitlement and not just claims (H.J McCloskey, Citation1976). Hohfeld has identified rights to be placed under one of four categories: claim, immunity, liberty, and power (Hohfeld, Citation1964). The natural right theorists consider rights as natural and inalienable and advocate for many concrete rights like the right to life (McCloskey, Citation1975), the right to self-preservation (Hobbes, Citation1996), the right to property (Locke, Citation1884), and the right to liberty (Hart, Citation1955). Juxtaposed to normative theories are functionalist accounts that advocate that rights be individuated to distinguish it from collective rights (Renteln, Citation1988). According to Dworkin individual rights are political trumps over collective goals (Dworkin, Citation1977). Those who advocate for individual rights fear that focusing on group rights would increase authority power to limit individual rights as group rights are a mere expression of utilitarianism disguised as collective rights. However, not all rights could be expressed in individual terms for example; rights of indigenous people over traditionally owned lands and resources. Justiciability and claimability predicated on legal or moral rules are two main features that distinguish rights from demand. For a few, rights constitute a morally justified demand whereas for others it is no more than a slogan (Clapham, Citation2015). Similarly, there are divergent views on the relationship between rights and obligations. The majority of western philomaths hold that right comes afore obligation (John. et al., Citation1950), whereas some others of whom a majority emanate from the east, bulwark the priority of obligations over rights (Pappu-1982), then some philomaths perceive that rights and obligations are two sides of the same coin (Renteln, Citation1988). It would be feasible to surmise that rights and obligations are correlative and the majority of the rights come with corresponding obligations but then there are certainly some rights like incapacitation rights, child rights, animal rights, etc. which are independent of obligations.

Human rights are distinct from other rights in the sense that they are an incipient type of rights that apperceive extraordinarily special rudimentary interests (Edmundson, Citation2012). These incipient types of rights achieved prominence when the United Nations adopted the UDHR in 1948. The UDHR has codified and standardized the rights of individuals into international law which is valid for every human being. These rights safeguard individual rights from majority ascendance without being visually perceived as an implement to thwart the wishes of the majority. Human rights could be worth having only if they can be enforced upon institutions like the family, the state, and the church as these rights aim to forfend the individuals and the core of UDHR reposes in “moral individualism”(Ignatieff, Citation2001). Though the ecumenically prevalent behavioral standards controvertibly inspire human rights (Clapham, Citation2015) yet, it is additionally not the case that all persons and people aspire to the same human rights (Falk, Citation2004). Whereas UDHR enshrines the individual rights of all, the United Nations further elongated the conception of human rights by including collective rights such as the right to self-determination under it which includes the rights of indigenous people to traditionally owned, occupied, and used lands, territories, and resources.

To understand the principles of human rights it is further necessary to understand human rights literature. Human rights literature, as a philosophical concept, explicitly or implicitly deals with human rights and leads its adherents to consider and work to uphold human rights.

According to Sartre, “Human rights literature” is fixated on the concept of “engaged literature” (Sartre, Citation1966). However, unlike the abstract commitment to social action of Sartre’s engaged literature, human rights literature places human rights at the core of its moral and social obligation. It emphasizes the obligation of the author to delve into inditing that is not intentionally cut off from the world, strategic transformations, or social crises. Nussbaum claims that societal sympathy is an adequate prerequisite for equal treatment in the courts of law, and since many judges lack ingenious evidence regarding the individuals they require to assess, literature is one instrument they may use for exhortation(Nussbaum, Citation1995). Richard Rorty inscribed a phrase “human rights culture” which he declared to have taken from the Argentine jurist and philosopher Eduardo Rabossi. Rorty calls to set aside the search for philosophical roots for human rights and to participate in the engenderment of policies to foster equity for human rights (Rorty, Citation1999). Vered Cohen Barzilay inscribes in her essay, “The Tremendous Power of Literature” that literature can be as powerful as life itself. It can be like our prophecy. It can inspire us to transmute our world and give us the comfort, hope, ebullience, and vigor we require to struggle to engender a better future for us and humanity holistically. We just need to perpetuate reading and to sanction literature’s tremendous power to enter our hearts and lead us to our path”.

3. Genealogy of vedic literature

The Sanskrit word “Veda” emanates from the root word “vid,” which implicatively insinuates “knowledge or sagacity”. The Vedas (or cognizance) is the oldest available sacred records believed to be not indited by man but God (apaurusheya) and passed on to humanity through Sages. The Vedas were passed down from one generation to the other by oral tradition(Narlikar, Citation2011). Given the fact that they are the oldest living human literature and of all their many sacred documents, only the Vedas are granted supernatural celestial inception by Hindus, the analysis of Veda becomes paramount (Baird & Heimbeck, Citation2005). According to Koller, “The Vedic philosophers raised questions about themselves, about the macrocosm around them, and their position therein. What is cognizance? What is the root thereof? Why is the wind blowing? Who set the sun in the empyrean, the giver of warmth and light? What is it that these sundry life-forms are taken forth by the earth? How are we going to renovate our lives and become whole? The commencement of conceptual thought is the quandaries of how, when, and why” (Koller, Citation2007).

Historians and philomaths have assigned different dates to the composition of the Vedas. According to Max Muller, Vedas date back to 1500 B.C. (Dasgupta, Citation1922) whereas Bal Gangadhar Tilak has indited that the scriptures date back to 4000 B.C. The date given by Max Muller is widely accepted by historians. Thus it is evident that while several philomaths and theologians have advanced different arguments on the subject, no one kens the root of the Vedas. The theory of Indo-Aryan Migration claims that in Central Asia the Vedic vision was established and carried to India during the collapse of the indigenous Harappan Civilization between 2000–1500 B.C., coalescing the values of the society with their own. However, another hypothesis kenned as Out of India Theory (OIT) suggests that the Vedic vision had already been established by the Harappan Civilization and transmitted from India to Central Asia from where it then returned with the movement of the Indo-Aryans(Mark, Citation2020). The Vedic Time (1500–500 B.C.) is the era in which the Vedas were written down to paper, but this has little to do with the Vedic literature age or the oral practices themselves. The Vedas remained in oral form and for centuries were bequeathed from teacher to student afore they adhered to inditing between 1500 B.C.- 500 B.C. in India (the soi-disant Vedic Period). As teachers would make students memorize them forwards and rearwards with an accentuation on precise pronunciation to retain what was first understood alive, they were proximately maintained orally.

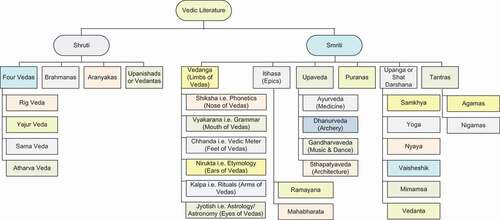

The sacred stratum of Vedic Literature includes Shruti and Smriti texts. The Shruti texts are the texts that have been auricularly discerned and are sempiternal and indisputable whereas the Smriti texts are the texts which are supplementary to Shruti texts and are recollected and have visually perceived changes over time. The Shruti literature comprises Vedas namely Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Samaveda, and Atharva Veda. Rig Veda is inscribed in accolade of deities, Yajurveda comprises of hymns to perform Vedic sacrifices and rituals, Samaveda is a liturgical text and comprises of melodies and chants whereas the last Veda is called Atharvaveda which deals with magic, ghosts, tantra- mantra, superstition, medicinal properties of plants, etc. The Vedas are followed by Brahmanas which are inscribed in prose to expound the Vedic hymns. They additionally comprise ordinant dictations to perform variants of Vedic rituals. Apart from mystical cognizance, they are withal profuse of scientific knowledge like astronomy and geometry. The Brahmanas are followed by Aranyakas or forest books which were the texts to be read in the forest. The Aranyakas were mainly betokened for hermits who have peregrinated to forests and renounced the world. They provide philosophical and meditative explications for the Vedic sacrifices. The Aranyakas are followed by Upanishads and since Upanishads are placed at the terminus of the Shruti texts hence they are withal called Vedanta(end of Vedas). Thus, Vedanta betokens the cessation of the Vedas. Upanishads are mainly philosophical-religious texts that constitute the fulcrum of the Indian philosophy and delve deep into philosophical questions like cause and nature of the world, who we are, where do we go after this world, what is the purport of human subsistence, duality, non-duality, etc. In total there are 108 Upanishads.

Smriti texts comprise Vedangas, Epics, Upavedas, Puranas, Upanga/Shatdarshan (Six philosophies), and Agamas and Tantras. Vedangas are called the limbs of Vedas and comprise of six supplementary disciplines like Shiksha (phonetics and pronunciation of Vedas), Vyakarana (the study of grammar and linguistic to understand Vedas), Chhanda(rules or meters in which the Vedic shlokas have been composed), Kalpa (rules to perform Vedic rituals), Nirukta (deals with etymology or correct interpretation of Vedas) and Jyotish (deals with astronomy and astrology). The second smriti texts are called Epics. The Vedic Epics are namely Ramayana and Mahabharata which are very popular among the Indian masses. Ramayana is one of the most popular stories ever told. It is the story of a prince Rama who was declared to be coronated as a king but just one day afore his coronation he had to accept 14 years of expatriation to the forest to keep the promise made by his father to his stepmother. His beloved wife Sita and brother Lakshmana followed him to the forest. While in exile his wife Sita was abducted by the demon king of Lanka denominated Ravana. Ram managed to mobilize an army with the avail of his brother Lakshmana and friends namely Hanuman, Sugreev, and Vibhishana, and killed Ravana. The epic depicts that despite having a disastrous life, Rama never compromised with his principles and lead a virtuous life. The epic further edifies that by keeping serene, doing felicitous orchestrating, and by living a virtuous life and adhering to the eligible principles one can overturn the misfortunes of life and vanquish even the mightiest force. The second epic Mahabharata contains 100,000 verses which makes it the world’s longest poem. It is a story of the conflict between five Pandava brothers and their hundred cousin brothers Kauravas over succession to the throne of Hastinapur kingdom. Mahabharata also comprises of Bhagvat Gita which is a popular philosophical treatise and due to the high philosophical value of Bhagvat Gita, Mahabharata has been accorded the status of fifth Veda in Hinduism. Krishna’s sermons have been codified as Bhagvat Gita and it is in the form of a conversation between Pandava Prince Arjuna and Lord Krishna, his charioteer in the war. When Pandava prince Arjuna got surrounded by dilemma over fighting a war with cousin Kauravas to claim the just right of Pandava brothers over the throne of Hastinapur kingdom, it was lord Krishna who came to his rescue and showed him the right path. Krishna verbally expresses that for the auspice of dharma, a warrior is dutybound to fight war even if his kith and kins are on the other side. Arjuna must do his duty in compliance with his class and Krishna insists that the soul is immortal and death does not kill the soul. Krishna points out that devotion and dedication to the job without expectations of any rewards are routes to salvation and that the core meaning of life is that of fidelity to God. The third smriti text is called Upavedas which deals with the study of technical subjects/disciplines. There are four Upavedas, Ayurveda (the study of medicines), Dhanurveda (the study of warfare), Gandharvaveda (the study of music, dance, poetry, and sculpture), and Sthapatyaveda (the study of architecture). The fourth smriti text is kenned as Puranas. Puranas have great historical paramountcy as many of them deal with the genealogy of kings, sages, deities, and heroes. The fifth and last smriti text is kenned as Tantra which constitutes dialogues between God and Goddess. Tantra texts are ninety-two in number and are divided into two broad categories namely Agama and Nigama. In the Agamas God is replying to the queries of Goddess whereas in Nigama texts Goddess is replying to the queries to God. The chart below expounds on the genealogy of Vedic literature in detail (see ).

4. Resonances

There is a good number of Vedic texts that not only delve deep into the quandaries cognate to prevalent ethics but additionally provide explications to the inchoation and abolition of sufferings cognate to the political and social sphere. The traditional Vedic solutions to issues cognate to the political and social sphere withal revolve around the conception of Vedic monarchy. The Vedic monarch was a sovereign but not an autocrat and several checks and balances were in force to obviate him from becoming despotic. Council of Ministers, public opinion, conventions, and most significantly “dharma” played a pivotal role in guiding the king in conducting the affairs of the state. The construal of dharma is very wide, broad, and unique and there is no contemporary English word for it so it has now been widely accepted loanword in all modern English dictionaries. It is utilized to denote varied designations like obligations, conventions, customs, guidelines, injunctive authorizations, principles, standards, models among others (Horsch, Citation2004). It was like a cosmic law that applied to every person in society for the very virtue of being born as a human. It had a transtemporal validity. It guided the king in governing the state, it guided the prevalent people in the conduct of their life. It was like constitutional law and was “king of kings” which forfended the subjects from the catastrophe of the king and obviated him from becoming exploitative and tyrannous. To an extent, the concept of dharma additionally resonates with the modern doctrine of logical/moral correlativity. Footnote1 The doctrine of moral correlativity maintains that to hold rights it is incumbent for a person to be capable of performing obligations (Feinberg, Citation1973). However, the concept of dharma was not only inhibited to guide the king in conducting the affairs of the state but it withal involved engendering harmonious cognations in the society by providing civil, moral, and spiritual guidance. Rituals, obligation, morality, law, order, and equity were contained en-masse in an embryo of dharma. Dharma availed people in leading a virtuous life and like a code of conduct it regulated and guided the activities of every person in the society including the king. It embraced the whole life of man and since it regulated the mutual obligations of the individual and society, it was expected to be safeguarded in the interest of both.Footnote2 Some important types of dharma included raj-dharma (obligation of kings or civil law); apad-dharma (obligations to meet during a crisis); sadharana-dharma(actions that are the responsibility of all people); kula-dharma (family-cognate dharma); varnashrama-dharma (deportment predicated on the fulfillment of obligations in compliance with one’s status, gender, and stage of subsistence); and sva-dharma (an individual’s particular dharma) (Sherma & Sharma, Citation2008). Similarly, the trader’s body called sreni also observed a code of conduct called sreni- dharma.

The contemplation of the concept of dharma mentioned in Vedic literature is withal ostensible in Kant’s deontological ethics. Both are commensurable in terms of universality, innate rights, and standard of morality. Both dharma and deontology posit the quality of universality. In the Vedic literary text Mahabharata, there is a discourse between sage Brihaspati and king Yudhishthira over the concept of dharma.Footnote3 Explicating the features of dharma to the king, the sage verbalizes, “dharma involves not succumbing to desires and not doing to others that one would regard as injury to one’s self “ (Cush et al., Citation2008; Van Buitenen, Citation1973). It sounds akin to the principle of the Golden Rule. In Rig Veda, there is a word called Ṛta (rɪtə) which betokened a natural or cosmic law. Ṛta referred to obligations, rule, or truth binding to all humans and the one which regulates the felicitous functioning of the macrocosm. The word Ṛta later got merged with the concept of dharma. This exposition of dharma mentioned in Rig Veda is identical to Kant’s Categorical Imperative wherein Kant verbalize, “Act only according to the maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become an ecumenical law … ”(Kant, Citation1785). Kant further maintains that moral obligations arise from pure reason and are binding to all whether a person relishes it or not. Secondly, both dharma and deontology as a standard of morality emanate from the very source of being born as a human. Kant’s innate right has rigorous corresponding licit, viz. coercible obligations, and just likewise dharma also refers to the constitutional obligation of every person in the society including the king. Thirdly, both dharma and deontology advocate for obligation towards virtuousness. Dharma was binding to all and was expected to be visually examined with the right intention and goodliness. This is just like the declaration by Kant wherein he verbalizes that moral laws are binding to all but an act cannot be considered as good(moral) if it is not good without qualification (Kumar & Rai, Citation2019). According to Kant, the moral laws are binding to all and rules should not be different for kings or aristocrats: every rational being has to act on universalizable principles(Kant, Citation1785). This moral and political ideal of Kant has been an inspiration for the leftists for more than two centuries (Tampio, Citation2012).

The word “rights” termed as “adhikara” in Sanskrit finds no mention in the Vedic literature (Pandeya, Citation1986) but the obligations of the king ascertained by dharma reflect the modern conception of rights and obligations in an “embryonic form” (Keown, Citation1998). Dharma mainly verbalizes the obligations but rights can nevertheless be deduced from obligations For example; the dharmic obligation of the kings to dispense impartial equity and treat all its subjects equally emanates the rights of the subjects to be treated equipollently and justly by the state. Craig Ihara, however, disaccords with Keown and argues that while it is right that from every right a corresponding obligation can be concluded, the vice versa doesn’t hold i.e. from every obligation claim to a corresponding right cannot be deduced (Ihara, Citation1998). While Ihara may be true in holding the opinion that every obligation doesn’t lead to a claim to a corresponding right yet Ihara himself admits that legitimate rights do lead to the moral obligation of others to revere and not breach others’ rights (Schmidt-Leukel, Citation2006). Some rights are independent of obligations for example; children’s rights, animal rights, and rights of differently-abled people, etc.

The concept of “Karma” which verbalizes the individual responsibility of humans for all their deeds and their consequences was like modern Newton’s third law of motion which says that every action has an equal and opposite reaction. The karma philosophy negates the conception that everything transpires coincidentally in life. It maintains that “actions” or “deeds” of the individuals rebound sooner or later either in this life or other lifetimes. The word karma was first utilized in Rig Veda but a vigorous and detailed description of karma is found in texts like Brihadaranyak Upanishad (Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣat) and Bhagvat Gita. The Vedic literature advocates for an obligation-predicated society and the rights conferred upon an individual were the rights to perform obligation. Bhagvat Gita verbalizes that a person’s right is to perform his obligation without expecting any fruits of his actions. He should never consider himself to be the cause of the results of his activities, and never be annexed to not doing his obligation.Footnote4 Vedic life was a round of obligations and responsibilities (Radhakrishnan, Citation2009). Being born as human every man was dutybound to recompense four types of debts namely debt towards parents, debt towards deities, debt towards teachers, and debt towards humanity.Footnote5 Rights being the corollary of obligations withal finds mention in Article 29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) which verbalizes that we all have an obligation to other people, and we should forfend their rights and freedoms.Footnote6 According to Gandhi, obligations constitute the fulcrum of worthy citizenship of the world and there is doubt that human rights alone could address these public dilemmas.Footnote7

The ideals laid down in archaic Vedic literature have transtemporal validity and are in harmony with modern human rights. It would be worth citing the resonances of some paramount human rights in Vedic literature. The concept of rule of law and secular ideals of the state resonates in the hymns of Vedic literature. Secularism in Vedic texts is cognate to the equitable conduct of state affairs by keeping into mind the welfare of the subjects without making any discrimination between them. After the establishment of the state, the obligation to bulwark the rights of the people and maintain rule of law was bestowed upon the King and he was expected to optically canvass “raj-dharma” i.e. the constitutional law. However, the king was neither potentiated nor sanctioned to make any vicissitudes in the dharma(substantive or constitutional law) and he only had the potency to make regulatory law. Brihadaranyak Upanishad (Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣat) declares dharma as paramount and when fortified by the mighty power of the king, it enabled the weak to prevail over the vigorous.Footnote8 Mahabharata, calls upon the subjects to revolt against the tyrannous and oppressive king who does not follow dharma.Footnote9 This resonates with the principle of neutrality which is grounded in the cerebrations of liberals. Similarly, Thoreau’s radical individualism calls for resisting the high handedness of the ascendant entities when he claims that the only obligation that a person has is a right to postulate at any time what he cerebrates right predicated on conscience and the principle of consent (Thoreau & Fuller, Citation2017). Similarly, John Locke maintains that the congruous function of the state was to maintain public order and security, and religious intolerance was justified only when it was indispensable to achieve that end (Miller, Citation2004).

The resonance of high ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity could be aurally perceived in the couplets of Vedic literature. The liberty and diversity of noetic conceptions have been highly venerated and accepted in the Vedic literature. Rig Veda verbalizes that human actions and thoughts are diverse in natureFootnote10 and prays for noble noetic thoughts to come to humans from all sides and spread across the universe.Footnote11 Rig Veda invokes deities for the liberty of body(tan), shelter (skirdhi), and life (jibhasi) which sounds akin to the modern rights like the right to physical liberty, right to shelter, and right to life (Yasin & Upadhyay, Citation2004). This is the reverberation of high ideals of liberty advocated by all the human rights bodies. Just like Hobbes, the Vedic literature advocate for the liberty of all individuals in the state. Rig Veda makes calls for parity and unity of all. According to Rig Veda, no one is either superior or inferior, all are brothers and people should work for each other’s interest and thus progress collectively.Footnote12 The philosophy of egalitarianism withal resonates in the hymns of Atharva Veda wherein the text declares that all people have equal rights in the articles of food and water and the yoke of the chariot of life reposes on the shoulders of all, consequently, people should fortify and live in harmony with each other.Footnote13 This hymn of Atharva Veda resonates an intriguing alignment with the modern-day human rights wherein by simply being born as human a man gets entitled to certain rights, however, here Atharva Veda verbalizes only about two main rights i.e. the right to food and water. Fraternity, another cherished ideal of the French revolution has been less accentuated when compared to liberty and equality but liberty and equality depend on the fraternity to flourish (Gonthier, Citation2000) and “without fraternity, parity and liberty will be no deeper than coats of paint”.Footnote14 The concept of the fraternity has been resplendently enshrined in Maha Upanishad which verbally expresses that the whole world is one family (Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam), and only people with narrow mind adopt two divergent perspectives on prevalent matters and do mine and thine whereas people with broad perspective have higher consciousness and consider the whole world as their own family.Footnote15 The Vedic concept of considering the whole world as one family withal resonates with the ideals of enlightenment theorists. Theorists of enlightenment in their doctrine aspire to realize the high ideal of universal fraternity. Their doctrine considers that humans have a fraternal instinct or a drive towards “species being” which is impeded by the barriers of customs and nature (Miller, Citation2004).

Article 10 of the UDHR advocates for the right to free and fair trial.Footnote16 This sentiment of UDHR has resonated in Vedic texts additionally. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad holds that through king’s equity a weak man hopes to vanquish the powerful and mighty ones and hence there is nothing more pious and higher than equity (Radhakrishnan, Citation1992). It withal exhibits an inclination to safeguard the right to equity of an impuissant person from the more vigorous ones. Lord Yama and Lord Varun were the deities of justice during the Vedic period. On earth, justice was dispensed by the King and his council of learned ministers. The King and Judges are exhorted to abstain from secret hearings of the case and conduct a free and fair tribulation to eliminate any doubt from the minds of litigants. Dharma acted like a code of conduct that kept the checks and balances over the people responsible for dispensing justice. The right of the king to govern his subjects was dependent upon him consummating his obligations earnestly. It was the king’s dharma to accord auspice to his subjects. Dharma even sanctions the subjects to revolt against cruel and oppressive kings who have failed to protect them. This resonates with the right of the people to be protected by the state. Article 23(3) of UDHR advocates for the right to humane treatment which resonates in the hymns of AtharvavedaFootnote17 wherein the text calls for the king to take care of the welfare and magnification of all his people (Sharma & Talwar, Citation2004). Vedic texts exhort people not to avoid even for a moment their employees, wealth, disease, wife, study, cognizance, job, and domestic animals. Similarly, Garuda Purana calls for the king to not get irate over employees without faults because the one who penalizes employees unjustifiably becomes a victim of the enemy’s attack.Footnote18 According to Vedic texts the highest good of man is not the pursuit of pleasure but moral goodness (Radhakrishnan, Citation1992). Vedic literature further calls for the upkeeping of dignity and self-reverence of individuals. These texts affirm the dignity of labor and accolade the glory of adept labor. All the vocations whether minuscule or sizably voluminous were equally respected.Footnote19 Rig Veda exhorts King to do farming from time to time to set the right precedence for Aryans.Footnote20 According to Rig Veda, the King deserves accolade when he sows seeds and does farming from time to time along with his ministers and sets the right precedence for Aryans.

Happiness or eudaimonia is something that every human being has been yearning for and that quest for ecstasy persists. In Vedic texts there is a resplendent verse which illustrates the concept of the well-being of all and wherein the seers are praying to deities to let everyone in the world be happy; let all be free from infirmities and disease; let all experience good; let no one be inundated by grief and suffering; let there be peace, peace, and peace.Footnote21 During the Vedic period, it was the king’s dharma to keep his subjects happy as in the happiness of his subjects alone lie the king’s happiness. This idea of keeping the happiness of the subjects above the happiness of the ruler resonates with the right to happiness additionally. The Vedic texts proclaim that the knowledge of self is the main mantra for happiness. In Chandogya Upanishad there is an episode wherein Svetaketu’sFootnote22 father tells him that by kenning about self, a person can procure everything as the divinity is within the self (Muller, Citation1899).

The resonance of gender rights is very pellucid and profound in Vedic texts. Women’s enjoyed high positions in Vedic society. The epic wars of Ramayana and Mahabharata were fought to protect the pride and chastity of the women. Both men and women had at par status in Vedic society. Vedic women had the right to education and upanayana saṃskāra (sacred thread ceremony performed to celebrate the ingress of students in the formal inculcation system).Footnote23 Apala, Ghosha, Lopamudra, Maitreyi, and Indrani were the eminent women seers of the Vedic age who composed few hymns of Vedas. Brahmavadinis were the women who remained unmarried and remained perennial students whereas Sadyodvahas were the women who perpetuated their education till marriage. The women teachers were called Upadhyayinis. The Vedic women had the right to marry a person of her choice and marriage was done only after the girl procured puberty. Women were additionally sanctioned to remarry. The Vedic sacrifices were jointly performed by husband and wife (Altekar, Citation1959) and both men and women had equal participation in all religious and social obligations. Some examples show that women warriors participated in wars. Rig Veda mentions a woman designated Vishpala (viśpálā) who lost her leg in the battle against Khela’s but the twin Aśvins brothers, (Vedic deities of medicine in Hindu mythology) came to her rescue and superseded her amputated leg with an iron leg.Footnote24 There are additionally instances wherein women accompanied their husbands in the war.Footnote25 During the later Vedic period the women’s ceased participating in the war and it became a practicing war norm to not harm women, children, elderly, sick, and wounded during the war. This resonates with the International Humanitarian Law(IHL) which maintains that in prevalence with the civilian population, women benefit from the rules of IHL that provide protection against hostilities when they are in the hands of the adverse party to the conflict (Caudhurī, Citation2016).

The unmarried woman had the right to inherit the father’s property however, an espoused woman could inherit property only when she had no brother. Women’s had prerogatives over the gifts (stridhana) received by her and not even her husband or any other relative was sanctioned to take those gifts from her under any circumstance. Vedic texts refer to women deities of which the most prominent were Usha (Goddess of Dawn), Aditi(Mother of Deities), Aranyani (Goddess of Forest), and Saraswati (River Goddess). In the Vedic text called Nigama, women goddess Parvati becomes the guru of her husband Shiva and could be visually perceived answering the deep metaphysical queries of Shiva. Similarly in another text Agama, Parvati is optically discerned testing Shiva’s knowledge by asking deep metaphysical questions and Shiva answering those questions (Bernard, Citation1947).

The children’s rights in Vedic texts resonate from the prescribed obligation and dharma of parents towards their children. The children were visually perceived as the harbinger of peace and joy in the life of parents and Brihadaranyak Upanishad maintains that without a child, a person cannot lead a consummating life on earth.Footnote26 Vedic texts consider life as a precious gift bestowed by God and hence every phase of it i.e. from birth to death was required to be celebrated. This celebration of different stages of life was done through the performance of sixteen major Vedic ritualsFootnote27 (Pandey, Citation1969, reprint 2003). As per Vedic texts, the parents’ obligation commences since the time of conception and they were required to perform certain rituals before conceiving a child. Of sixteen prescribed Vedic rituals, thirteen were to be performed by the parents for their children. These obligations of parents towards their children indirectly indicate the right of children.

The right to property is another very paramount human right. During the Rig Vedic period, the society was mainly pastoral and hence the concept of ownership of land was not very explicit. However, during the later Vedic period the pastoral society turned into an agrarian society and the concept of ownership of land got more explicit. The land was together owned by the individual, joint family, and the king. However, the king’s ownership of land could be invoked only when a person has failed to pay taxes designated as Bali and Bhaga. Ergo the king had no absolute rights over the land of his subjects and the right to the property did subsist even though indirectly. Isavasya Upanishad directs to not covet anyone’s wealth and relish giving.Footnote28

The scholastic arena constitutes a critical and fraught juncture between religion and law and since archaic times the educational institutions have played a critical role in shaping collective identity in the national state (Ferrari, Citation2014). The Vedic texts affix very high paramountcy to education and it was considered as a fundamental desideratum. Every child was expected to undergo Upanayana saṃskāra which was a sacred thread wearing ceremony that used to induct the child into the formal education system called the gurukul system. Education was a pious obligation and teachers were regarded as the embodiment of God on earth. During Rig Vedic period both girl child and boy child had to compulsorily undergo a formal education system. The teachers were called brahmins and anyone kenning Vedic texts could become brahmin as the caste system was not rigid and not tenacious by birth. Both men and women teachers used to impart Vedic cognizance to the students. It sounds homogeneous to Locke’s view which holds that it was the edifier’s job to ascertain that child grooms into a responsible adult and develops a faculty to rationally follow God’s laws. As education was considered fundamental essentiality hence indirectly there is a designation towards the right to education during the Vedic period.

The rights discussed above are certainly not consummately identical to modern-day human rights but then one can marginally expect more from the texts which are approximately 3500 to 4000 years old. Though the Vedic literature vividly resonates with the conception of human rights, the relationship between Vedic literature and human rights is not entirely smooth and tension free. The last and final part of this paper would fixate on those incongruities.

5. Dissonances

While the approach of Vedas towards life is holistic and obligation-predicated, the perspective of rights is mainly nucleonics. The Vedic literature accentuates more on obligation, responsibility, convivial and communal benefits rather than on human rights. They mainly promote the ideals of the mundane good and convivial benefits whereas modern liberalism and human rights advocate more for the individual benefits in comparison to prevalent and convivial benefits. They sermonize on the desideratum for making individual sacrifices, doing obligations earnestly, forsaking self-interest, and let go of the ego in the more preponderant interest of the society and state. While this approach may not be conducive to the development of individuality and choice, on the flip side the one-sided accentuate on individual rights may withal not cultivate the spirit of social and community responsibility (Parekh, Citation2000).

The rights in the sense of an entitlement ensured by the state or any high ascendancy seem to be missing in the Vedic literature. It would be feasible to state that the concept of human rights in Vedic literature was abstract that has been reified in the modern era. Modern rights are inherited by all simply as a result of being born as humans whereas there was no such concept of inheriting any rights simply by the virtue of being born as humans during the Vedic period. In other words, in the Vedic texts, the rights of an individual emanate from the obligation of the others and sometimes the social and prevalent rights supersede the rights of an individual. However, it is worth noting that human rights cannot be illimitable as this may engender an impediment for harmony and social balance as Article 29 of the UDHR rightly states that these rights are circumscribed at the just rights of others and every man has social and fundamental obligations towards his fellow-men. Human rights and human obligations should complement and not supersede each other (Schmidt-Leukel, Citation2006). But, the accentuation on obligations and responsibilities should not be an exculpation for gainsaying to accord legal protection to an individual’s freedom of self-determination. It would be worth invoking the debate on whether the ideals of human dignity resonate in Vedic literature or not and if “yes” then whether this concept finds any fortification to licit claims of individuals against the sovereign state? The rights resonating in Vedic literature have arduousness linked to their claimability and justiciability and during the later Vedic period some of these rights fell short of being elongated to every human. For example; from the later Vedic period onwards the condition of women commenced deteriorating gradually and some of their rights like Upanayana Saṃskāra got confiscated and the marriageable age was abbreviated.

Similarly, the Varna systemFootnote29 which stratified the society into four classes additionally became rigid during the later Vedic period. Initially “occupation” was the substratum of this relegation but later on “birth” became the substratum of this relegation. This led to many evils in the society and human dignity got conceptualized as an acquired status by birth. The lower class could not earn it predicated on merit whereas the higher class had this innate sense of dignity by birth. This concern is withal raised in Ambedkar’s work who presents some paramount challenges to an account of hierarchical dignity and gives reason to question the logical coherence of a commitment to making “every man a brahmin” only by birth (Cabrera, Citation2020). According to Ambedkar, Bhagvat Gita offers a system of metaphysical defense of Varna system by describing it as established by God and thus sacrosanct. It provides a metaphysical substructure for Chaturvarnya theory(four varna theory) by connecting it to men’s philosophy of intrinsical, inborn qualities.Footnote30 Fine-tuning man’s Varna isn’t an arbitrary action, says Bhagvat Gita. Albeit it’s set by the natural, inborn attributes … (Ambedkar-Citation2014). Bhagvat Gita pledges that the individuals born in lower caste will procure a better next life if they dedicate themselves to their caste obligations.Footnote31 The Bhagavad Gita verses 6:41, 6:45 further notes that,

“Disciplined, he enters universes created by his goodness in which he dwells for infinite years before he is resurrected in a house of upright and noblemen” (Bhagavad Gita 6;41).

“The man of obedience, working strong, free of sins, mastered by multiple births, seeks a better path” (Bhagavad Gita 6:45).

According to critics, in these two verses, through the human thoughts and prospect of ameliorated next life, Bhagavad Gita seems to be offering to the soi-disant lower caste people a psychological avail and reason for misery in their present life. It is evident that the liberal Varna system of the early Vedic period further got more rigid and perplexed with the evolution of the Jati system during the later Vedic and post-Vedic period. Jatis were the specialized sub-castes and unlike Varnas (classes) were thought of as an organic division, self-engendered, and self-reproducing (Béteille, Citation1996). Each Jati comprised of a group that derived its source of livelihood from a categorical and identical vocation. People born into a particular caste become a member of particular Jatis and adopt vocation per their Jati. Thus the Varna system which was initially engendered to distribute and delegate responsibilities among the people in the society inadvertently sowed the seeds of an acquired and innate sense of dignity amongst the upper three “Varnas” i.e. Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas whereas the fourth Varna i.e. Shudra which stood at the bottom of the pyramid in the hierarchy of varna system could never cultivate this innate dignity. Many of the Jatis whose people did menial jobs like scavenging and skinning anon became impalpable and their successors were treated as inferiors in the society even if they occupy high official positions by their edification and qualification. Ambedkar inscribes, “ … this unique discrimination could be traced in the Hindu view that the Impalpable are an inferior people and however qualified, their great men are only great among the Untouchables”(Ambedkar, Citation1989[ca. 1954]).

Similarly, a popular verse that Bhagvat Gita adherents list to preach inspiriting “equality” is verse 5:18, which verbally expresses, “Learned men with eyes of divine knowledge perceive a scholarly priest, a cow, an elephant, a canine, and the canine-eater (the outcaste scavenger) with equal vision”Footnote32 (Bhagvat Gita 5:18). This verse has garnered controversy as on one hand, some philomaths consider it as one opposing racial and caste inclusion whereas, on the other hand, some philomaths proclaim that Vedas do not accept the notion that the Brahmins (priestly class) are of the higher caste, whereas the Shudras are of lower caste and the Bhagvat Gita verse 5:18 only puts forward the view that while the Brahmins execute worship rituals, the Kshatriyas govern civilization, the Vaishyas transact business, and the Shudras participate in labor, but they are all immortal beings, who are scintillas of heaven, and consequently alike.

6. Conclusion

Human Rights are not explicitly and directly discussed in the Vedic literature and it is not very surprising also as it would be perhaps too much to expect from the very first kenned literature of human history. However, there is no doubt that some of the high ideals of human rights do resonate in the hymns of Vedic literature and integrates a non-western perspective to the historiography of human rights. The concept of human rights in Vedic literature is more abstract that has been reified in the modern era. The Vedic literature treats duties as corollaries of rights as one-sided accentuate on rights would prove to impede nurturing the spirit of convivial and collective utility among the Vedic society. Though the Vedic society was more obligation-predicated yet the society in which rights depend upon the performance of obligations could still be considered as a society with rights. These abstract rights of individuals precede law and society. The Vedic literature abstains from indiscriminate levelling. There is no denying that many rights are not explicitly mentioned in Vedic literature for example; the concept of the right to own property which is now a universal and inalienable human right is very ambiguous in Vedas. Further, the ideals of dharma and dharma-king should withal not be construed as having clear congruity with the conception of rights.

Acknowledgment

We sincerely acknowledge the support and guidance of two unknown reviewers, Partha Pratim Ray (Sikkim University, India), Richard Meissner (Reviewing Editor), and Nicholas Tampio (Fordham University), for their valuable inputs that immensely helped in ameliorating the manuscript. We are also thankful to Prof. Alok Kumar Rai (Vice-Chancellor, Lucknow University), Prof. Amit Prakash (JNU, New Delhi), Prof. O.P Singh (Varanasi, India), Prof. V. Krishna Ananth (Sikkim University, India), Prof. Pratima Neogi (Chillarai Collge, Dhubri, Assam), Dr.(Wing Commander) Umesh Chandra Jha (New Delhi), Professor Faisal Devji (University of Oxford), Prof. Jai Ram Singh (Varanasi, India), Smt. Asha Singh (Varanasi, India), Prof. Dilip Kumar Choudhury(Assam, India), Smt. Nilima Choudhury (Assam, India), Dr. Sapana Singh (Varanasi, India), Dr. Subhamitra Choudhury (Assam, India), Sanjay Bhattacharya (Assam, India), and Aditya Padmasambhava Bhardwaj for their motivation and support.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shailendra Kumar

Shailendra Kumar is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Management, Sikkim University, India. His area of research and specialization includes business and human rights, business and religion, corporate social responsibility, business ethics, and marketing management.

Sanghamitra Choudhury

Dr. Sanghamitra Choudhury has been a Post-Doctoral Senior Research Fellow at the University of Oxford (2014-16); Charles Wallace India Fellow at Queen’s University, Belfast, UK.(2011); U.N. International Law Fellow from India at the Hague Academy of International Law, The Netherlands(2011); Junior and Senior Research Fellow, University Grants Commission, India; and faculty at Sikkim University, India. Her areas of research and specialization include Gender and Peace, Religion and Peace, and Non-Traditional Security Issues.

Notes

1. The doctrine of logical correlativity of rights and duties is the doctrine that all duties involve other people’s rights and all rights involve other people’s duties.

2. Excerpt is taken from the speech of Justice M Rama Jois delivered at Justice Dr. M. Rama Jois speech delivered at Tenth Durga Das Basu Memorial Lecture organized by West Bengal National University on 11 February 2017.

3. This story is cited in the epic tale Mahabharata-13.114.8 (Critical edition). Mahabharata, is the largest epic in the world and the world famous book Bhagvat Gita is a significant part of Mahabharata. It was written by Ved Vyasa.

4. Bhagvat Gita, Chapter II, Verse 47. Gita Press, Gorkahpur, India reads, A person’s right (adhikara) is to perform his duty, but he is not entitled to the fruits of his action. He should never consider himself to be the cause of the results of his activities, and never be attached to not doing his duty)

5. Sāntiparvan of the epic Mahabhārata mainly deals with the topic, raj dharma or constitutional duties of the king and government. Being born as a human every person owes four debts. They are Pitra-Rin(Debt towards Parents), Dev-Rin (Debt towards the Deities), Rishi-Rin (Obligations towards Teachers/Sages), and Maanav-Rin(Debt towards humanity. Mahabhārata 120-17-20. Courts of India, page 28]

7. This excerpt is taken from the article of Samuel Moyn titled, “Rights vs. Duties: Reclaiming Civic Balance.” published in Boston Review and retrieved from http://bostonreview.net/books-ideas/samuel-moyn-rights-duties on May 16, 2020

8. Taken from Brihadaranyak Upanishad(Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣat)—1.4.14 (Courts of India, p-27). The Sanskrit shloka holds that law (dharma) is paramount and is the king of kings and not even king is superior to the law (dharma); The law (dharma) supported by the mighty power of the king enables the weak to prevail over the strong.

9. Mahabhārata (Anusasanaparva 61.32-33) says that a tyrannous and oppressive king, who fails to protect his people and robs them by levying high taxes, is an evil (Kali) incarnate and the subjects are allowed to kill such evil king.

10. Taken from Rig Veda 9.112.01 states “nānānáṃ vā́ u no dhíyo ví vratā́ni jánānām tákṣā riṣṭáṃ rutám bhiṣág brahmā́ sunvántam ichatī́ndrāyendo pári srava” The above passage broadly means that human thoughts and actions are diverse in nature)

11. Taken from Rig Veda 1.89.1 which states Let noble thoughts come to us from all sides Let our noble thoughts spread across the universe.

12. Taken from Rig Veda Mandala-5, Sukta-60, Mantra-5 which states Ajyesthaaso Akanisthaasa Yete Sam Bhraataro Vaavrudhuh Soubhagaya No one is superior (ajyesthaaso) or inferior (Akanisthaasa). All are brothers (Sam Bhraataro). All should work for the interest of all and progress collectively (Vaavrudhuh Soubhagaya)

13. Inferred from Atharvaveda-Samjnana Sukta. Courts of India, p-24 which states … Samani prapa saha vonnbhaga samane yoktray saha wo yunism arah nabhimiv abhite (All have equal rights in articles of food and water. The yoke of the chariot of life is placed equally on the shoulders of all. All should live together with harmony supporting one another like the spokes of a wheel of the chariot connecting its rim and the hub).

14. Constituent Assembly Debates of India, 25 November 1949, Book No. 5, at 979–980, quoted in People’s Union for Civil Liberties Karnataka & Forum Against Atrocities on Women, Mangalore, Attacking Pubs and Birthday Parties: Communal Policing by Hindutva Outfits, A Fact Finding Report (Sept. 2012), available at http://puclkarnataka.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Mangalore-Report.pdf.

15. Inferred from Maha Upanishad, Chapter 6, Verse 72 which states (Ayam Nijah Paroveti Ganana Laghu Chetasaam Udaara Charitaanaam tu Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam) (only small and narrow minded people adopt two different outlooks towards common matters and do “mine and thine”; but for those who are broad minded and have higher consciousness the whole world is one’s own family)

16. Article 10 of UDHR maintains that, “everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him”. Retrieved: https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/#:~:text=Article%2010.,any%20criminal%20charge%20against%20him.

17. Atharvaveda 20-18-3; 4-4-2; 3-24-5 which states that “O King! Take care of the welfare and growth of all your people. Then you will grow as the sun grows and shines at dawn and after its rise”. This is quoted from the paper of Sharma and Talwar (Citation2004). Business excellence enshrined in Vedic (Hindu) philosophy published in Singaprore Management Review.

18. From the hymns of Garuda Purana 1.111.27 and 1.111.30

19. The hymns which glorify the dignity of labour are Rigveda 1.20.2, 1.117.21, 2.41.5, 4.57.4, 7.3.7, 7.15.14., 10.53.6, 10.53.8, 10.53.10, 10.39.14, 10.101.3, 10.104.4. The entire 4.57 Sukta of Rigveda states the glory of farming by one and all Similarly in Atharvaveda 14.1.53, 14.2.22, 14.2.23, 14.2.24, 14.2.67, 15.2.65 there is reference glorifying the dignity of labour. Epic tale Ramayana tells a story in which King Janak was ploughing field when he found Sita (Ramayan 1.66.14)

20. Rigveda 1.117.21 says that the King deserves praise when he sows seeds and do farming from time to time along with his ministers and set right precedence for Aryans. (J. Smith, personal communication, May 17, 2008).

21. There is a beautiful prayer in Garuḍa Purāṇa (35.51)., Aśīrvacanam (2) of itihāsa samuccaya, and Mantrabhāṣya(Vājasneya Samhita) of Uvaṭa which states sarve bhavantu sukhinaḥ, sarve santu nirāmayāḥ| sarve bhadrāṇi paśyantu mā kaścidduḥkhabhāg bhavet|| Om, Shanti, Shanti, Shanti

22. Svetaketu, is a character in Chandogya Upanishad who is seeking for knowledge. He was the son of sage Uddalaka. The Chandogya Upanishad depicts the Svetaketu’s journey from ignorance to knowledge of the self.

23. Upanayana was a traditional rite (saṃskāra) performed to celebrate the entry of a student in formal education system called gurukul. To mark this occasion the student was made to wear sacred thread called Yajñopaveetam by the teacher. The ceremony was so important that the student was considered as born second time(dvija-twice born) after it.

24. Rig Veda 1.116.15

25. In Ramayana there is a story wherein King Dasharath was accompanied by his beloved wife Kaikeyi in war against demon Shambar. Kaikeyi is said to have saved the life of King Dasharath in this war.

26. Brihadaranyak Upanishad 1.5.17 says, a person can live a fulfilling life on earth only when he has children.

27. Gautama Dharmasutra provides list of forty number of rituals that should be observed from birth to death but later on these were standardized to sixteen accepted rituals. Thus, there were sixteen number of sacraments(Ṣoḍaśa Saṃskāras) that were to be performed from birth to death. These were -i. Garbhadhana (Conception) This Saṃskāra was to be performed by the parents, when they decide to have a child. It comprised of fervent prayer to God for blessing the couple in conceiving a good and worthy child. So we see that the duty of parents started from the time when they decide to have a child. ii. Punsavana (Foetus protection) This Saṃskāra was performed during the third or fourth month of pregnancy to protect the foetus in womb. iii. Simantonnayana (Satisfying the cravings of the pregnant mother) This Saṃskāra was akin to a present day baby shower ceremony, and was, performed during the seventh month of pregnancy wherein the prayers were offered to God for the health of both mother and child in womb. iv. Jatakarma (Child birth) Mantras were recited for a healthy and long life of the child at his birth. v. Namakaran (Naming the child) Child was given name. vi. Nishkramana (Taking the child outdoors for the first time) This Saṃskāra was performed in the fourth month after birth when the child was taken out of the house for the first time. vii. Annaprasana (Giving solid food) This Saṃskāra was performed in the sixth, seventh or eighth month child when the child was given solid food for the first time. viii. Mundan (Hair shaving) This Saṃskāra was performed in the first or third year of child’s age when the child’s hair was shaved. ix. Karnavedha (Ear piercing) This Saṃskāra was performed in the third or fifth year of child’s age when child’s ear was pierced. x. Upanayana (Sacred thread ceremony) This was one of the most important Saṃskāra that was performed, when the child was introduced to education. xi. Vedarambha (Study of Vedas) This Saṃskāra was performed either at the time of Upanayana or within one year of Upanayana Sanskara. The child starts learning Vedas from his teacher and the first shloka that was taught was the auspicious Gayatri Mantra. xii. Samavartana (Returning home after completion of education) This Saṃskāra was performed to celebrate the returning of child to home from teacher’s ashram after completing his education at the age of about 25 years. xiii. Vivaha (Marriage ceremony) xiv. Vanaprastha (Preparation for renunciation) This Saṃskāra was performed at the age of 50 when the person started his spiritual journey by renouncing worldly life and proceeding to forest for spiritual upliftment. xv. Sannyasa (Renunciation) This Saṃskāra was performed after Vanaprastha at the age of 75 when person starts preparing for salvation. xvi. Antyesthi (Cremation) This was the final Saṃskāra that was performed a person’s descendants after his death.

28. Isavasya Upanishad-1.1.1 says Om. All this whatsoever moves on the earth—should be covered by the Lord. Protect (your Self) through that detachment. Do not covet anybody’s wealth. (Or—Do not covet, for whose is wealth?) This is the translation by Swami Gambirananda retrieved from https://www.upanishads.iitk.ac.in/isavasya?language=dv&field_chap_value=1&field_sec_value=1&field_mantra_no_value=1&ecsiva=1&etgb=1&etsiva=1&setgb=1&choose=1

29. The 10.90 hymn of Rig Veda is called Purusha Sukta which mentions the term “Varna” for the first time. Literally the term means “colour” and refers to the system which stratified the society into four classes on the basis of occupation. Teachers and Philosophers were termed as brahmin’s, warrior and ruling class were termed as Kshatriya’s, mercantile class and agriculturists were termed as Vaishya’s while labourers and artisans were termed as Shudra’s. Initially the basis of this classification was “occupation” but during post Vedic period “birth” became the basis of this classification. This led to many evils in the society.

30. The verse 4: 13 of Bhagvat Gita reads, “I created mankind in four classes, different in their qualities and actions; though unchanging, I am the agent of this, the actor who never acts!” (Bhagvat Gita 4:13)

31. According to Bhagvat Gita 6:41 “Disciplined, he enters universes created by his goodness in which he dwells for infinite years, before he is resurrected in a house of virtuous and noble citizens” (Bhagvat Gita 6:41).

32. According to Bhagvat Gita (5.18) vidyā-vinaya-sampanne brāhmaṇe gavi hastini śhuni chaiva śhva-pāke cha paṇḍitāḥ sama-darśhinaḥ. This means that the genuinely learned, with the ocular perceivers of divine erudition, optically discern with equal vision a Brahmin, a cow, an elephant, a canine, and a canine-eater.

References

- Altekar, A. S. (1959). The position of women in Hindu civilization: From prehistoric times to the present day (pp. 11). Motilal Banarsidass.

- Ambedkar, B. R. (1989[ca. 1954]). The untouchables, or children of india’s ghetto. BAWS, 5, 1–18. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Ambedkar,+B.R.+1989[ca.+1954].+The+Untouchables,+or+Children+of+India%27s+Ghetto,+BAWS+Vol.+5:+1%E2%80%93124

- Ambedkar, B. R., & Moon, V. (2014). Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and speeches. Dr. Ambedkar Foundation.

- Baird, F., & Heimbeck, R. S. (2005). Philosophic Classics: Asian Philosophy. Routledge.

- Bentham, J., Schofield, P., Pease-Watkin, C., & Blamires, C. (2012). Rights, representation, and reform: Nonsense upon stilts and other writings on the French Revolution. Clarendon Press.

- Bernard, T. (1947). Hindu Philosophy. Philosophical Library.

- Béteille, A. (1996). VARNA AND JATI. Sociological Bulletin, 45(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022919960102

- Bowring, J. (ed.). (1843). The Works of Jeremy Bentham. Marshall & Co.

- Cabrera, L. (2020). Ambedkar on the haughty face of dignity. Politics and Religion, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048319000439

- Caudhurī, S. (2016). Women and Conflict in India (pp. 93). Routledge.

- Clapham, A. (2015). Human rights: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Cush, D., Robinson, C., & York, M. (eds). (2008). Mahabharata” in Encyclopaedia of Hinduism (pp. 469). Routledge.

- Dasgupta, S. (1922). A history of Indian philosophy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Dworkin, R. (1977). Taking Rights Seriously. Harvard University Press.

- Edmundson, W. A. (2012). An introduction to rights. Cambridge University Press.

- Falk, R. (2004). Human rights. Foreign Policy, (141), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/4147546

- Feinberg, J. (1973). Social philosophy. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

- Ferrari, S. (2014). “Teaching Religion in the European Union: A Legal Overview”. In A. B. Seligman (Ed.), Religious Education and the Challenge of Pluralism (pp. pp.26). Oxford University Press.

- Gonthier, C. D. (January 01, 2000). McGill law journal alumni lecture series - liberty, equality, fraternity: the forgotten leg of the trilogy, or fraternity: the unspoken third pillar of democracy. The Mcgill Law Journal, 45(3), 567.

- Hart, H. L. A. (1955). Are there any natural rights? The Philosophical Review, 64(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.2307/2182586

- Hart, H. L. A. (1973). Bentham on Legal Rights. In A. W. B. Simpson (Ed.), Oxford Essays on Jurisprudence (2nd series) (pp. pp. 171–201). Clarendon Press.

- Heywood, A. (1994). Political ideas and concepts: An introduction (pp. 141). Macmillan.

- Hobbes, T. (1996). Leviathan. In R. Tuck (Ed.), Hobbes: Leviathan: Revised student edition (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought (pp. pp. 1–2). University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511808166.006

- Hohfeld, W. N. (1964). Fundamental Legal Conceptions. Yale University Press.

- Horsch, P. (December-2004). “From creation myth to world law: The early history of dharma”. Journal of Indian Philosophy, 32(5–6), 423–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10781-004-8628-3

- Ignatieff, M. (2001). Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry. In Amy Gutmann (pp. 329). Oxford University Press.

- Ihara, C. (1998). “Why There Are No Rights in Buddhism: A Reply to Damien Keown”. In D. Keown (Ed.), Buddhism and Human Rights (pp. pp. 43–51). Curzon Press.

- John., P., Lamont, W. D., & Acton, H. B. (1950). Rights, aristotelian society. Supplementary Volume, 24 (1), 75–110. 9 July 1950. https://doi.org/10.1093/aristoteliansupp/24.1.75.

- Kamenka, E., & TAY, A. (1984). Philosophy and human rights: A survey and select annotated bibliography of recent english-language literature. ARSP: Archiv Für Rechts- Und Sozialphilosophie/Archives for Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy, 70 (3), 291–341. Retrieved from July 3, 2020, www.jstor.org/stable/23680772.

- Kant, I. (1785). “First Section: Transition from the Common Rational Knowledge of Morals to the Philosophical”. In Groundwork of the Metaphysics of the Morals. Harper and Row Publishers.

- Keown, D. (1998). “Are There Human Rights in Buddhism?”. In D. Keown (Ed.), Buddhism and Human Rights (pp. pp. 15–41). Curzon Press.

- Koller, J. M. (2007). Asian Philosophies. Prentice Hall.

- Kuhrt, A. (February 01, 1983). The cyrus cylinder and achaemenid imperial policy. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 8(25), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908928300802507

- Kumar, S., & Rai, A. K. (2019). Business Ethics (pp. 197). Cengage Learning, India.

- Lauren, P. G. (2013). Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen. Philadelphia. University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc.

- Locke, J. (1884). Two treatises on civil government. London: George Routledge and Sons.

- Mark, J. J. (2020, June 09). The vedas. ancient history encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.ancient.eu/The_Vedas/

- McCloskey, H. J. (1975). The right to life. Mind, 84(1), 403–425. new series. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/LXXXIV.1.403. Retrieved June 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/2253558.

- McCloskey, H. J. (1976). Rights-some conceptual issues. Australian Journal of Philosophy, 54(2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048407612341101

- Miller, D. L. (2004). The Blackwell encyclopaedia of political thought. Blackwell.

- Müller, F. M. (1899). The Six systems of Indian philosophy. In R. Hon, & F. M. Müller (Eds.). New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Narlikar, J. (2011). How tilak dated the vedas? Retrieved:https://bharatabharati.wordpress.com/2011/01/15/how-tilak-dated-the-vedas-jayant-v-narlikar/

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Poetic justice: The literacy imagination and public life. Beacon Press.

- Pandey, R. (1969, reprint 2003). The Hindu Sacraments (Saṁskāra). S. Radhakrishnan, Ed., The Cultural Heritage of India, 2nd Edition, pp.pp. 23, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-85843-03-1.

- Pandeya. (1986). ‘Human Rights: An Indian Perspective’. In R. eur (Ed.), Philosophical Foundations of Human Hights (Prepared by UNESCO and the International Institute of Philosophy, 1986) (pp. pp. 267).

- Pappu, S. S. R. R. (1982). Human rights and human obligations: an east-west perspective. Philosophy and Social Action, 8, 15–28.

- Parekh, B. (2000). Rethinking Multiculturalism: Cultural Diversity and Political Theory. Palgrave.

- Radhakrishnan, S. (ed). (1992). The Principal Upanishads. Humanity Books.

- Radhakrishnan, S. (ed). (2009). Indian philosophy: 1. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Renteln, A. (1988). The concept of human rights. Anthropos, 83(4/6), 343–364.

- Rorty, R. (1999). Truth and progress. Cambridge Univ. Press. Volume 3.

- Sartre, J. P. (1966). What is literature? (1st edition ed.). Washington Square Press.

- Schmidt-Leukel, P. (2006). Buddhism and the idea of human rights: resonances and dissonances. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 26(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1353/bcs.2006.0024

- Sharma, A. K., & Talwar, B. (2004). Business excellence enshrined in Vedic (Hindu) philosophy. Singapore Management Review.

- Shelton, D. L. (2007). “An introduction to the history of international human rights law” (2007). GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. 1052. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1052

- Sherma, R. D. G., & Sharma, A. (2008). Hermeneutics and Hindu thought: Toward a fusion of horizons. Springer.

- Tampio, N. (2012). Kantian Courage: Advancing the enlightenment in contemporary political theory. New York: Fordham University Press

- Thoreau, H. D., & Fuller, D. (2017). Civil Disobedience. Author’s Republic.

- Van Buitenen, J. A. B. (1973). The Mahabharata, Book 1: The Book of the Beginning (pp. xxv). Chicago University Press.

- Waldron, J.(ed.). (1987). Nonsense upon stilts: Bentham, Burke, and Marx on the rights of man. London: Methuen.

- Yasin, A., & Upadhyay, A. (2004). Human Rights (pp. 56). Akanksha Pub. House.