Abstract

Under the lens of Neoclassical Realism, this article aims to comprehend the vanishing claims of Brunei in the South China Sea, by considering systemic stimuli and elite perceptions as major factors to the foreign policy decision. The results of this research indicate that; (1) The current Multipolar International system contributed to Brunei’s decision to secure BRI-related development investments and to advance the two-way trade between the countries, (2) The unified perception of Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah, Brunei MOFA, and the Royal Brunei Navy to place more weight on the perception of alignment for future economic gains, therefore, side-lining their claims.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The South China Sea conflict is one of the flashpoints of international relations in the 21st century. China’s Nine-Dash line claims have led great power contestations to take place, including claimant states in Southeast Asia. Brunei has taken the stance of a silent claimant to the seas, but has shown indication of vanishing its claims, despite China’s direct violation of Brunei’s territorial waters. In understanding the vanishing claim, this study looks deep into how the current multipolar system and domestic elite perception of China have equally contributed to Brunei’s differing approach in handling the South China Sea dispute.

1. Theoretical foundation

The territorial disputes over the South China Sea have now reached an escalated and concerning rate. Continuous developments conducted by China in the Scarborough Shoal, Spratly Island, and Paracel Islands, have been the center point of attention for claimant states to the South China Sea, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam, and the Philippines (Luttrull & Fleming, Citation2020; Singh & Yamamoto, Citation2017). As of 2020, China has continuously piled sand onto reefs in the South China Sea, with these artificial islands being transformed and filled with port facilities, military buildings, even to airstrips (Nohara, Citation2017; Qi, Citation2019; Xie, Citation2014). The accelerated rate of construction has made claimant states wary of such developments, except for Brunei Darussalam (Brunei).

Brunei’s claims in the South China Sea are considered less in comparison towards other of its Southeast Asian neighbors. Brunei claims a certain maritime boundary in the North of Borneo, which is currently being contested by Brunei and China (Odgaard, Citation2003; Rüland, Citation2005). Brunei, as a country with vastly limited resources in Southeast Asia, considers all available natural resources to be critical in order to maintain order and provide economic opportunities to the 420 thousand citizens that currently reside in that country. But a troubling dynamic has emerged since the incidents in the South China Sea have occurred. The crisis between China and the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia has surfaced from time to time, majorly concerning the problem of maritime territorial trespassing to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the respective Southeast Asian states (Mancheri, Citation2015). This issue though does not appear to take place between Brunei and China. This poses a number of questions, due to the irregularity of foreign policy implemented by Brunei in the crisis of the South China Sea. Brunei’s reluctance to take a strict stance in the South China Sea conflict provides explanatory room towards explanations that emphasizes the power of economic opportunities in shaping and reorienting certain foreign policies implemented by state actors.

The current stance taken by Brunei from 2010 until the present time represents a dynamic of ‘foreign policy anomaly. Other claimant states to the South China Sea have consistently shown and expressed their tough stance and unwillingness to give up the significant maritime boundaries to one of the most emerging economies in the world (He, Citation2019; Sato, Citation2013; Suehiro, Citation2017). However, Brunei has decided to consider other alternatives in responding to China’s aggression in the South China Sea, by neglecting the act of belligerence, and focusing on the possible opportunities that can preside if a soft stance is implemented in the case of the South China Sea. The act of foreign policy implemented by Brunei also constitutes as a foreign policy anomaly as state actors are not accustomed to being silent once a certain state or non-state actor decides to unilaterally claim a large amount of a state’s EEZ, which are not based on existing International law instruments (Oba, Citation2019). As of 2020, all of the claimant states to the South China Sea (Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei) are parties to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and have implemented measures that are consistent to the clauses outlined in the Law of the Sea. This explains why the Philippines are confident enough to bring their maritime boundary claims to the South China Sea arbitration case, which was decided in favour of the Philippines in 2016 (Pemmaraju, Citation2016; Wiegand & Beuck, Citation2018). Therefore, the limited act of aggression and protest expressed by claimant states of the South China Sea is well based on existing International law instruments. Despite so, as a party of the UNCLOS, Brunei has shown a disregard and neglect towards that reality, and somehow surrendered in the crisis.

This article aims to shed light on the current dynamics in the South China Sea, by focusing on the foreign policy anomaly that has been embraced by Brunei since the escalation of the South China Sea crisis. In analysing the choice of foreign policy implemented by Brunei, this article employs the theory of Neoclassical Realism, specifically to the concept developed by Ripsman et al. (Citation2016) that elaborates on how elite perception, strategic culture, state-society relations, and domestic institutions influence the choices of foreign policies embraced by state actors, as well as how structural factors influence decisions. However, this article will only focus on the influence of systemic stimuli and test the intervening variable of elite perception for the case of Brunei, with aims to answer whether differing opinions exist in Brunei, in regards to the South China Sea crisis, and how significant those differences in perceptions are towards the outcome of foreign policies decided by Brunei as a country. By the end of this article, the focus on Brunei and the question of whether elite perception matters, in this case, will directly contribute to contemporary discourses of Neoclassical Realism that relates to whether certain domestic variables such as elite perceptions alone can provide explanations to the choices of foreign policies by state actors, especially in the setting of non-democratic states.

Discussion on past studies related to this article will focus to fill in the following research gaps; (1) relevance of Neoclassical Realism in study cases of non-democratic states, and (2) Brunei’s orientation of foreign policies related to the South China Sea. A systematic analysis will be provided concerning both research gaps, firstly by outlining past relevant studies, and secondly pointing out gaps in the literature as well as its significance.

The focus of Neoclassical Realism is to evaluate foreign policy outcomes. Systemic factors (a state’s relative power in the International system) and domestic constraints are both considered, as both variables are able to provide a balanced explanation that differs itself from pure systemic factors of foreign policy determinants as those in the Classical Realism School. Since the introduction of Neoclassical Realism through Gideon Rose (Citation1998), to well-recognized studies related to the equal impacts of systemic and unit-level variables (Zakaria, Citation1991), and the need to always connect systemic and unit-level variables in contextualizing foreign policy decisions (Schweller, Citation2004; Zakaria, Citation1998), the focus of existing studies is to justify the need to take systemic and domestic variables into consideration when it comes to foreign policy analysis.

The trend that must be highlighted in this case is that existing literatures have chosen study cases of democratic states in analysing cases under Neoclassical Realism. Past notable studies that have employed Neoclassical Realism include the differing perceptions of threat for Indonesia (Syailendra, Citation2017), balance of risk for great powers such as the US (Taliaferro, Citation2004), and the Theory of Underbalancing (Schweller, Citation2004), which are all unified by the assumption that a democratic process exists in the foreign policy decisions chosen by state actors. Therefore, enabling intervening variables to be varied to include stakeholders under the government (ministers, departments, institutions, etc.). Although the study of Neoclassical Realism has been considered as revolutionary in providing a different perspective in justifying foreign policy options of state actors, a significant research gap exists in the case of non-democratic states that may not have other voices besides the autocratic leader of that state. Therefore, this research will fill in this major research gap in the study of Neoclassical Realism, by testing the relevance of systemic stimuli and domestic constraints (specific to elite perception) to determine the relevance of this theory in the context of non-democratic states such as Brunei.

The second discourse focuses on Brunei’s foreign policy in the South China Sea. It is worth noting that literature specifically addressing this question is near non-existent. Scholars have majorly focused on identifying patterns of foreign policy for other claimant states to the South China Sea (Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia the most) (Guoxing, Citation1998). This trend can be constituted to the fact that most crisis in the South China Sea relates to the obvious trespassing of maritime zones for the previously mentioned states (Huxley, Citation1998; Rüland, Citation2005; TO, Citation1999). Brunei on the other hand is a silent claimant, as it is by coincidence that the Nine-Dash Line collides with Brunei’s EEZ.

In regards to past studies on this topic, a limited number of discourses have been developed. First of all, it is worth noting the distinct stances adopted among ASEAN states, a discourse that has been well developed by scholars such as Darmawan and Mahendra (Citation2018) and Storey (Citation2014). The different stance adopted among member states of ASEAN is majorly constructed based on claimant and non-claimant states, with claimant states being more vocal in ASEAN led forums. But this is not the case for Brunei, as Brunei’s stance in the South China Sea has been consistent with non-claimant states to the South China Sea, a phenomenon that will be investigated in this article. But to provide a foundation for the upcoming arguments on Brunei’s foreign policy behavior towards the South China Sea crisis, the dilemma is well highlighted by (Noor and Daniel (Citation2016) Noor & Daniel, Citation2016) that provides a limited explanation on how the economic opportunities of engaging with China are more favorable over maritime claims. It is thus imperative to complete this discourse by filling in the research gap of how Brunei vanished its South China Sea claims due to systemic and domestic factors.

In comprehending the foreign policy behavior of Brunei in the context of the South China Sea conflict, the methodological approach to this research will consist of both primary and secondary data to complete the qualitative analysis put forward in the article. The primary data here are defined to consist of government statements and official positions, meanwhile, the secondary data consist of relevant articles and books that focus on determinants of foreign policy behaviors, especially in the case of Brunei. For both the primary and secondary data, the period defined is between 2010 and 2020. A deductive approach is embraced in identifying how systemic and domestic factors impact certain orientations of foreign policy.

As previously stated, literature analysing Brunei’s foreign policy in the context of the South China Sea conflict is scarce. Considering the unique stance of Brunei in comparison to other claimant states to the South China Sea, it will be critical to include the most relevant variables that can shed light on the orientation of Brunei’s foreign policy that has throughout the years vanished. In an attempt to answer this dilemma, this article employs the theory of Neoclassical Realism, by considering the impact of systemic stimuli, and how intervening variables consisting of domestic determinants can also influence foreign policy choices taken. The defining question that this article hopes to contribute is towards the question of “How systemic and domestic factors (specific to elite perception) influence the conduct of Brunei’s foreign policy in the South China Sea conflict.”

It is worth noting that the utilization of elite perception alone will need a justification, considering that Ripsman et al. (Citation2016) lists four different intervening variables, which include; (1) elite perception, (2) strategic culture, (3) state-society relations, and (4) domestic institutions, as significant intervening variables under Neoclassical Realism. However, high consideration is given to criticisms of Neoclassical Realism, in which many argue that the choice of domestic determinants in study cases have been majorly “random,” with authors failing to justify why certain intervening variables are chosen over the other. This article thus will focus on the intervening variable of elite perception alone, as the empirical facts show a consistent pattern of the impact that elite perception can lead to. Elites here include state policymaking stakeholders with high influence on the construction of foreign affairs-related issues. For this research, the elite perceptions that will be considered include the Brunei Sultan (Hassanal Bolkiah), Brunei Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Royal Brunei Navy.

The intervening variables of strategic culture, state-society relations, and domestic institutions will not be valid in analysing Brunei’s foreign policy. Such variables can be considered for study cases that focus on democratic states, in which enough spaces exist for other governmental institutions to adopt a distinctive stance in certain cases of foreign policy issues. Brunei’s system of absolute monarchy ultimately closes such possibilities, with the Sultan having complete authority over the perception of threat, and the final word in foreign policy decisions.

2. Systemic and domestic factors to the vanishing claims of Brunei in the South China Sea

The claimant states of the South China Sea have shown consistent policies in response to China’s belligerence in the South China Sea (Odgaard, Citation2003; Santino & Regilme, Citation2018; Thayer, Citation2016). The Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia have been vocal in the various International law violations committed by China in the South China Sea. Some claimant states have responded by taking the matter to international arbitration (Blazevic, Citation2012; Thayer, Citation2011), meanwhile some state actors have reoriented their grand strategies in order to respond to the political landscape in the region (Qi, Citation2019; Suehiro, Citation2017). Vanishing here is defined as a non-responsive action taken by state actors, amid the emergence of the South China Sea crisis. Being responsive in action will constitute the act of harsh statements (rhetoric) and policy-based actions such as pushing regional norms, and reorienting the past policies to include the present danger. This article argues that Brunei is considered a silent claimant state that has no regard whatsoever as to what happens in the South China Sea, despite a small portion of the disputed areas that include Brunei’s maritime zone. The following elaborates on the systemic and domestic factors that influence this choice of foreign policy, with specific reference to elite perceptions that will represent the domestic factors in general.

2.1. The pressure of the international system: Brunei’s relative power in a multipolar age

A major cornerstone of Brunei’s foreign policy is through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Brunei became a member in September 1984, and has since then shown great enthusiasm to contribute to the Southeast Asian regionalism, despite limitations in human and natural resources (Evers & Karim, Citation2011; Thambipillai, Citation2008; Weatherbee, Citation1983). Through ASEAN, Brunei has been able to mobilize most of its resources to establish firm diplomatic relations with neighboring states such as the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia (Koh, Citation2013). One of the factors that have constructed Brunei’s foreign policy in the South China Sea is the current structure of the International system, especially in the continent of Asia.

Throughout the years, the International system has tremendously evolved in power structures. Starting from a bipolar system during the Cold War between the US and USSR, we have now come to an age in which not a single state holds hegemonic status in the International System (Copper, Citation1975; Kegley & Raymond, Citation1992). The US hegemonic status has been contested with emerging economies and previously existing powers in the form of Russia, China, and to a certain extent, other members of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) (Bharthur, Citation2018; Bond, Citation2018; Dwyer & Arifon, Citation2019; Sarkar, Citation2014). It is thus justified to argue that we are currently living in an International system of multipolarity. This is not a favorable status quo, especially for middle powers that may be stuck in the middle of great power politics among one of the major existing powers (Vo Huyen Dung, Citation2020). This is the case in the Asian region, with great power contestations between the US and China, on many fronts of International politics (Darwis et al., Citation2020).

For states in the Southeast Asian region, their stance has been clear since the 1950s. Most have shown support to non-alignment initiatives that do not force them to align with a certain great power during the Cold War (US or USSR) (Kardelj, Citation1976; Mates, Citation1989). And such a background provides room for small states such as Brunei to exert its limited International influence through organizations such as ASEAN. It provides a major strategic position for Brunei as it has the opportunity to echo norms align to Brunei, but through a solid regional organization in the form of ASEAN.

But in responding to the current structure in the International system, through its activeness in ASEAN, Brunei has agreed with the concept of Omni-Enmeshment, as a Southeast Asian strategy in responding to great power politics in Southeast Asia. The crisis in the South China Sea has led contestations between the US and China to emerge, and transform the geopolitical landscape of the Asian region (specifically in the Pacific Oceans) to one that is volatile. As argued by Evelyn Goh (Citation2007) in the article Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia, Brunei is a major proponent of engaging states to involve it in a web of sustained exchanges and relationships. This condition establishes room for norm unification and integration between Southeast Asian states (through ASEAN) with China, which may have implemented different norms throughout the years in its conduct of international politics.

Brunei’s trust towards ASEAN’s regional norm construction in the Southeast Asian region is not baseless. The region has been faced with great power rivalry over the South China Sea, which involves half of the members of ASEAN. In response, ASEAN has been able to exert its influence to conclude a conflict management proposal to implement non-coercive and non-belligerent military postures in South China Sea through the Declaration of Conduct in the South China Sea. ASEAN is also currently in the talks with China to conclude the Code of Conduct, which will act as the primary International law to regulate the dynamics in the South China Sea. ASEAN thus hopes to represent the voices of middle powers amid the presence of great power politics in the region.

But states such as Brunei have embraced the perception that the Omni-Enmeshment may not always work, especially in the construction of norms in the South China Sea. In reality, the slow progress to conclude a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea has led claimant states to act independently on the matter. Philippines and Vietnam, for example, are well-known to be more vocal and coercive in their approach in defending their EEZ. Indonesia as of late has also shown a strict stance to defend their territorial sovereignty. The dynamics in the past several years indicate that despite that there is a level of trust in the Omni-Enmeshment, states continue to be present in a self-help system, leading them to implement a plan B in case ASEAN’s norm construction in the South China Sea fails. Brunei is no exception, considering their intensive bilateral relations with China since the past decade.

In responding to the dynamics caused by a multipolar world structure, Brunei has focused to show a gesture to align with China, despite engaging at the same time, the strategy of Omni-enmeshment of ASEAN peaceful norms in the region. This condition is due to the growing interdependence of the Brunei economy towards China’s future-oriented development projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and favorable foreign direct investments throughout the years (Aoyama, Citation2016; Xue, Citation2016; Yoshikawa, Citation2016). As the second-largest economy in the world, China’s economic prowess has shaped the perception of Brunei of the clear gap of power between China and Brunei, leading Brunei to establish stronger alignment with China, rather than going against it. The following explanations will provide the basis of justification for Brunei’s engagement to China, with reference to the consistent rise of two-way trade and BRI-related development projects and foreign direct investments to Brunei.

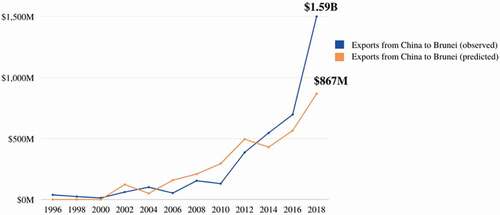

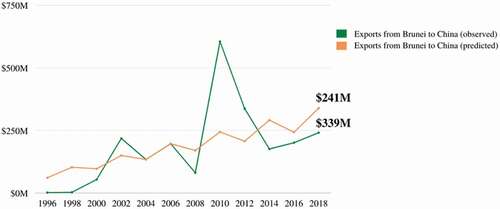

Between China and Brunei is a consistently rising two-way trade that has indicated a steady trend since 1996. In 2018 alone, the estimated value of exports from China to Brunei is USD 1.5 Billion, with Brunei to China’s estimated value of export calculated to USD 241 Million (OEC, Citation2020). As shown in , a steady rise of two-way trade between China and Brunei indicates a healthy economic and diplomatic relations among the two-state actors. Furthermore, it is worthy to note that the observed trend of economic partnership has not fluctuated since 1996 until 2018, which indicates a consistent economic partnership and favorable prospect for future partnerships to come. Based on the bilateral trade by-products, we can see a certain trend in which China’s exports to Brunei have focused on commodities such as iron structures and machineries, meanwhile Brunei’s focus of commodities to China being majorly petroleum gas and acyclic alcohol. In understanding the significance of the two-way trade, the annualized rate of China-Brunei trade has increased by 18%, meanwhile Brunei-China’s annualized rate increase has risen by 49% since 1998 to 2020 (OEC, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Export forecasts from China to Brunei (1996–2000)

Figure 2. Export forecasts from Brunei to China (1996–2000)

The growing significance of the two-way trade between China and Brunei can also be associated with the alignment of Brunei’s Wawasan Brunei 2035 to China’s BRI. Wawasan Brunei 2035 is Brunei’s defined national vision, in which it is hoped that the country achieves a number of goals by the year 2035, including educated citizens, a sustainable economy, as well as highly skilled and dynamic individuals (Bo, Citation2017; Widyawardhana et al., Citation2018). Meanwhile, in an attempt to secure the Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOC) of China’s demanding energy needs, the BRI is a global infrastructure development project that focuses on securing strategic areas for global export-import security (Callahan, Citation2016; Hu, Citation2019). Throughout the years, Xi Jinping and Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah have coordinated closely on how to connect the grand strategies of Wawasan Brunei 2035 and the BRI in order to establish grounds of intensive cooperation among the states. China has throughout the years pitched the construction of the Brunei-Guangxi Economic Corridor, Land-Sea Trade Corridor, the advancement of trade and investments, as well as the China-Brunei Year of Tourism, as several examples of China’s ambitious projects to secure Brunei’s trust and allegiances (CGTN, Citation2018).

Brunei is much attracted to petrochemical-based trade and relations with China, due to aspects that go beyond this sector. The rise of China is inevitable, and the BRI is a major stepping stone to China’s global dominance in world affairs (Zhou & Esteban, Citation2018). By focusing on the petrochemical-based trade and relations, Brunei is laying the foundations for securing solid foreign investments to diversify its economy through projects under the umbrella of the BRI. As an oil-producing state located in Southeast Asia, fluctuations in oil prices may become critical for Brunei’s economic future. By taking this approach, Brunei is ensuring that fluctuations to the oil prices will not lead to Brunei’s economic downfall. In the past years, investments have taken place in diversifying sectors, including small and medium enterprises, petrochemical industries, as well as infrastructure.

Brunei can also act as a strategic partner for China’s future trade projections in the Southeast Asian region, considering Brunei’s position that channels access to the Malacca Strait. Furthermore, China’s investments have been consistent, as seen by the investments from Zhejiang Hengyi Petrochemical Corporation that will proceed to production in 2019, and the second stage to be completed in the upcoming 2022 (Shumei, Citation2018). In the past, China also invested in the construction of the Muara Terminal between 2014 and 2019, with a value of US$ 3.4 billion (CIMB, Citation2018), under the umbrella of the BRI. It is worth noting that the Zhejiang Hengyi is, for a small country with limited economic options and natural resources, reflects China as a solid economic partner for Brunei. As states argue about the true intentions of the BRI and how it will negatively impact countries, Brunei focuses on the rhetoric of economic opportunities for a country with limited options.

The introduction of the BRI has led a number of development projects to take place in Brunei, and attracted foreign direct investments from China. It has been difficult for Brunei to attract a consistent source of foreign direct investments due to the dwindling supply of oil and gas, until China’s promising development projects under the framework of the BRI. A number of promising investments include the petrochemical and refinery complex, container ports, integrated industrial park, and a number of investments directed to the fields of education, logistics, finance, and many others. It is thus much justified to conclude that China in the status quo and in the distant future, will be part of Brunei’s strategic plans due to the overarching benefits of aligning itself to the second-largest economy in the world. Therefore, unlike the Philippines, Vietnam and Indonesia’s domestic unrest and debates about China’s true intentions, Brunei has come to a conclusion to surrender to China in a Multipolar system with intentions to secure itself.

2.2. Elite perceptions in Brunei’s vanishing claims in the South China Sea dispute

In understanding Brunei’s foreign policy towards the South China Sea between 2010 and 2020, this section will focus on elite perceptions consisting of the Monarch (Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah) that holds supreme autocratic authority, Brunei’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), and the Royal Brunei Navy. Elite perception is defined as stakeholders in a state that have influential voices in determining certain foreign policy actions. In the case of the South China Sea, considering the scope of the issue being of maritime boundaries in nature, the three chosen stakeholders are justified to represent the intervening variable of elite perception for this analysis. But in comparison to past studies, we need to understand that the issue of Brunei’s foreign policy cannot be understood the same with those of other claimant states to the South China Sea. In the system of Brunei’s absolute monarchy, Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah has the supreme authority of both executive decisions for domestic dynamics and towards foreign affairs. Therefore, the perception of threat will mostly be driven by the Sultan’s perception of threat, rather than having the Foreign Affairs Ministry and the Royal Navy embracing a distinct perception of threat. It is worth noting that despite this issue of absolute monarchy, the argument is that if a consensus on the perception is reached, the foreign policy, however different it is to others, will be implemented.

Sultan’s perception towards the South China Sea is overweighed by the general perception of Brunei towards China. In general, the Sultan highly favors China due to the promising economic partnership that can be established in the current status quo, and how Brunei’s Wawasan Brunei 2035 can be integrated into China’s BRI initiatives in Brunei. Brunei’s vanishing claim in the South China Sea thus can be concluded because of the Sultan’s perception of the South China Sea as not a major national interest agenda that must be defended.

But Sultan’s perception is not straightforward in the South China Sea conflict. He faced a dilemma of whether to adopt a stance that is pure of national interest, or to follow the constructed norms of ASEAN. In 2012, despite Brunei’s willingness to be silent on the South China Sea conflict and to not be frontal on the matter, Brunei decided to participate in the making of the Declaration of the Conduct on the South China Sea (DOC) (Mishra, Citation2017; York, Citation2015). In the same year, Sultan Bolkiah also expressed in an opening statement in the ASEAN Summit of his concerns over the South China Sea disputes and how it can grow to become a new source of tension (ASEAN, Citation2012). He echoed the need for ASEAN to make necessary continual adjustments amid the great power contestations in the region. But Sultan’s act of concern and the need for ASEAN to adapt is a gesture that follows along with the regional norm of ASEAN in responding to the South China Sea. The Sultan’s perception even since 2012, has always been one that neglects the significance of the conflict to Brunei’s national interest. In comparison to other claimant states to the South China Sea conflict, Brunei is categorized as a silent actor in the conflict due to fears of China’s retaliation on the prospective trade among Brunei and China.

Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah always had a high focus on domestic-oriented policies to be achieved, such as the Wawasan Brunei 2035. Furthermore, Brunei always praised China for bringing major infrastructural projects to Southeast Asia in the form of the BRI. In 2017, Brunei hosted the China-ASEAN Expo and Sultan Bolkiah delivered an opening speech at that Expo, stating that China-ASEAN’s relationship “is an interdependent partnership,” stressing the importance of China’s BRI and its impact to the global economy (CAEXPO, Citation2017). Brunei’s neglect over its territorial waters in the North of Borneo was solidified since 2018, when both states agreed that they will cooperate in the disputed waters to exploit gas and oil (Zhen, Citation2018).

Both the MOFA and the Royal Brunei Navy does not have a significant difference in perception as the Sultan. MOFA and the Royal Brunei Navy have focused on executing the perception of the Sultan in the South China Sea conflict. Since 2013, it has been the MOFA that emphasized the need to cooperate, be peaceful and diplomatic in resolving the South China Sea dispute (Brunei, Citation2013). Similar to the Sultan, MOFA also integrates ASEAN norms in interacting with other Southeast Asian states in relation to the conflict. This is reflected by Brunei’s limited-assertive responses when crisis occurred in the area (Hara, Citation2019). An example, how in 2016, the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Hj Erywan stated that the urgency to restrain from any conflict-inducing activities in the disputed waters on the South China Sea (Xinhua, Citation2016). A similar gesture is also adopted by the Royal Brunei Navy, though not as conclusive as to the previously stated elite perceptions.

In general, the Royal Brunei Navy has been silent in a number of South China Sea-related crises that have occurred in this past decade. It is essential to note that in 2019 and 2020, the Royal Brunei Navy has shown certain gestures that many may question as against China in the South China Sea. First, in 2019, the US and Brunei conducted a 10-day naval exercise at Muara Naval Base in Brunei (Lopez, Citation2019). Second, in 2020, Brunei participated in a naval drill with the Philippines and Vietnam (Mangosing, Citation2019). In both cases, the emphasis is on maritime coordination and security in securing the maritime boundaries of states. But this article argues that in both cases, the perception of the Royal Brunei Navy is still aligned to that of the Sultan and Brunei MOFA. In the naval exercise, the US-Brunei cooperation is purely based on Brunei’s support over existing global norms related to the freedom of navigation. The participation only indicates that Brunei is still integrated into relevant global maritime norms and willing to respect it. Therefore, the subject of focus, unlike the US, is not to send a message to China on the urgency to implement a freedom of navigation norm in the South China Sea. In the second case on the naval drill with Vietnam and the Philippines, it may seem at first that conducting a naval drill with other claimant states to the South China Sea is a posture of coerciveness. But this action only represents Brunei’s support over regional norms that is implemented in ASEAN through the DOC, which asserts that a peaceful relation must be maintained in the conducts located in the South China Sea. Therefore, similar to the first case, the aim is not to send a message of coerciveness and strictness to China, but to assure regional partners that Brunei is still willing to contribute to regional security-based norms in the region. The Royal Navy does not implement an independent and differing perception on the South China Sea to that of the Sultan, as it will also be unfeasible to implement a different perception considering the non-democratic setting of Brunei.

In conclusion, the current silent claim of Brunei by positioning the country to have a vanished claim in the South China Sea can be constituted to the unified perception that the matter is overweighed by Brunei’s other economic interests. The urgent need to continuously attract China’s foreign direct investments, and assist in realizing the Wawasan Brunei 2035 equally contributes to the unified perception of the Sultan, MOFA, and the Royal Brunei Navy in the case of the South China Sea. In relation to the Neoclassical Realism theory in analysing foreign policy patterns, systemic stimuli have majorly influenced Brunei’s foreign policy to adopt a less coercive gesture in the South China Sea, meanwhile a unified elite perception equally contributed to the implementation of a foreign policy anomaly in comparison to other claimant states. The decision to slowly vanish the claims thus can be attributed to the Multipolar system and the unified elite perception that has evolved throughout the years.

Systemic Stimuli and elite perception have equally contributed to Brunei’s vanishing claims in the South China Sea. Brunei’s vanishing claims lead this article to conclude that Brunei will no longer contest in the South China Sea, and any form of indirect disagreement through ASEAN in the future is only a form of formality to prove Brunei’s adherence to regional norms constructed by ASEAN. Brunei will not act in coerciveness such as its neighbouring states, Philippines and Vietnam. It will, in the future, seek a diplomatic resolution with China in relation to China’s claims in Brunei’s EEZ, with full consideration to secure lucrative investments for Brunei’s development future.

3. Conclusion

Systemic stimuli and domestic constraints conclude as major factors in understanding the foreign policy orientation of Brunei towards the South China Sea dispute. Despite being a claimant state, Brunei has shown a distinct foreign policy posture by persuasively engaging China for economic opportunities, while neglecting their territorial claims in the South China Sea. In the argument of systemic stimuli, the multipolar system that emerged since the early 21st century has helped shape the foreign policy preference of Brunei. Considering the emerging economy and power of China in Asia, it has been imperative for Brunei to secure BRI-related development investments, and to advance the two-way trade between the countries. This status quo has led Brunei to undergo a double-stance approach in facing China in the South China Sea, which directly goes along the ASEAN regional norms that have been established, but at the same time, to be aware not to intervene or echo the issue in an exacerbated rate in which China will re-consider altering the current economic relations. Meanwhile, the intervening variable that can help clarify Brunei’s distinct behavior in the South China Sea is the presence of a unified elite perception that positions China as an ally, therefore neglecting any possible coerciveness in the political landscape related to the South China Sea. The Sultan of Brunei (Hassanal Bolkiah), Brunei MOFA, and the Royal Brunei Navy, all are united in the perception of how to view China specifically in the South China Sea dispute. In conclusion, the perception constructed is that the Brunei national interest in the disputes is side-lined, with the construction of possible future economic cooperation overweighing the importance, between the period of 2010–2020. Therefore, Neoclassical Realism provides a comprehensive understanding for policymakers in comprehending the Brunei foreign policy in the case of the South China Sea, as a claimant state. Both variables (system and domestic factors) proved to provide consistent justifications in understanding foreign policy behaviors.

4. Limitations and study forward

Neoclassical Realism’s major point of weakness is equally utilizing other intervening variables of Neoclassical Realism defined by Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell, including strategic culture, state-society relations, and domestic institutions. Though Neoclassical Realism can be relevant in understanding foreign policies of non-democratic states, specific intervening variables are difficult to measure if sub-national agents and domestic elements of a state do not have enough space to have independent analysis and responses to external threats, including in the case of Brunei. Future studies related to this article will need to have a deeper insight to the regional implications of vanishing claims in the South China Sea by Brunei (whether it could influence changes of the foreign policy of claimant states). Meanwhile, future studies in Neoclassical realism will need to develop other intervening variables that can act as alternatives to the traditional sub-national agents and domestic elements that are relevant in democratic settings.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my research assistant, Ari Putra Anugrah, that has dedicated the time to complete the data collection of the Brunei elite perceptions on the South China Sea dispute, as well as data analysis.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Bama Andika Putra

Bama Andika Putra is a lecturer in the Department of International Relations, Universitas Hasanuddin, Indonesia. He holds Master of International Relations degree from the Melbourne School of Government, the University of Melbourne. His major research interests are in Indonesian foreign policy, peace and conflict studies, and Southeast Asian regional dynamics.

References

- Aoyama, R. (2016). “One belt, one road”: China’s new global strategy. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 5(2), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2016.11869094

- ASEAN. (2012). Opening statement his majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam - ASEAN | ONE VISION ONE IDENTITY ONE COMMUNITY. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from https://asean.org/?static_post=opening-statement-his-majesty-sultan-haji-hassanal-bolkiah-sultan-and-yang-di-pertuan-of-brunei-darussalam

- Bharthur, S. (2018). New world information and communication order and BRICS: Legacies and relevance. Global Media and China, 3(2), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436418785029

- Blazevic, J. J. (2012). Navigating the security dilemma: China, vietnam, and the South China Sea. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 31(4), 79–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341203100404

- Bo, M. (2017). An analysis of the strategic synergy between Brunei Darussalam’s Wawasan Brunei 2035 and China’s Belt and Road initiative. Southeast Asian Affairs,1(1). http://jtp.cnki.net/bilingual/detail/html/LYWT201701006

- Bond, P. (2018). East-West/North-South – Or imperial-subimperial? The BRICS, global governance and capital accumulation. Human Geography, 11(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861801100201

- Brunei, M. O. F. A. (2013). Press room - joint statement between Brunei Darussalam …. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from. http://www.mfa.gov.bn/Lists/PressRoom/news.aspx?ID=36&ContentTypeId=0x01040055E31CAE71A9C144B21BBB007363093500B667C4949BC69D4394F4AC8FA016E767

- CAEXPO. (2017). Review of CAEXPO - China-ASEAN Expo. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from. http://eng.caexpo.org/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=lists&catid=10078

- Callahan, W. A. (2016). China’s “Asia Dream”. Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, 1(3), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057891116647806

- CGTN. (2018). China’s investment surge in Brunei: China investments at right time for Sultanate - CGTN. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from. https://news.cgtn.com/news/30557a4e7a494464776c6d636a4e6e62684a4856/share_p.html

- CIMB. (2018). China’s belt and road initiative (BRI) and Southeast Asia. www.cariasean.org

- Copper, J. F. (1975). The advantages of a multipolar international system: An analysis of theory and practice. International Studies, 14(3), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/002088177501400304

- Darmawan, A. B., & Mahendra, L. (2018). Isu Laut Tiongkok Selatan: Negara-negara ASEAN Terbelah Menghadapi Tiongkok. Jurnal Global & Strategis, 12(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.20473/jgs.12.1.2018.79-100

- Darwis, Putra, B. A., & Cangara, A. R. (2020). Navigating through domestic impediments: Suharto and Indonesia’s leadership in ASEAN. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 13(6), 808–824. https://www.ijicc.net/index.php/volume-13-2020/189-vol-13-iss-6

- Dwyer, T., & Arifon, O. (2019). Recognition and transformation: Beyond media discourses on the BRICS. Global Media and Communication, 15(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766518818858

- Evers, H.-D., & Karim, A. (2011). The maritime potential of ASEAN economies. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 30(1), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341103000105

- Goh, E. (2007). Great powers and hierarchical order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing regional security strategies. International Security, 32(3), 113–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/30130520

- Guoxing, J. (1998). China versus South China Sea security. Security Dialogue, 29(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010698029001010

- Hara, A. E. (2019). The struggle to uphold a regional human rights regime: The winding role of ASEAN intergovernmental commission on human rights (AICHR). Revista Brasileira De Politica Internacional, 62(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201900111

- He, K. (2019). Constructing dynamic security governance: Institutional peace through multilateralism in the Asia Pacific. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 8(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2019.1675240

- Hu, B. (2019). Belt and road initiative: Five years on implementation and reflection. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies, 11(1–2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974910119871377

- Huxley, T. (1998). A threat in the South China Sea? Security Dialogue, 29(1), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010698029001011

- Kardelj, E. (1976). The historical roots of non-alignment. Bulletin of Peace Proposals, 7(1), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/096701067600700110

- Kegley, C. W., & Raymond, G. A. (1992). Must we fear a post-cold war multipolar system? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 36(3), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002792036003007

- Koh, W. C. (2013). Brunei Darussalam’s trade potential and ASEAN economic integration: A gravity model approach. Southeast Asian Journal of Economics, 1(1), 67–89. https://so05.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/saje/article/view/48750

- Lopez, C. (2019). Navy wraps up 10 days of training with Brunei in South China Sea - Pacific - Stripes. STRIPES website. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from. https://www.stripes.com/news/pacific/navy-wraps-up-10-days-of-training-with-brunei-in-south-china-sea-1.605451

- Luttrull, J. E., & Fleming, S. (2020). Artificial island development in the South China Sea. Case Studies in the Environment, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/cse.2020.1112838

- Mancheri, N. A. (2015). China and its Neighbors: Trade Leverage, Interdependence and Conflict. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 4(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2015.11869082

- Mangosing, F. (2019). Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei navies stage drills near South China Sea | Global News. Inquirer.Net website. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from. https://globalnation.inquirer.net/179664/philippines-vietnam-brunei-navies-stage-drills-near-south-china-sea

- Mates, L. (1989). Security Through Non-Alignment. Bulletin of Peace Proposals, 20(2), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/096701068902000208

- Mishra, R. (2017). Code of conduct in the South China sea: More discord than accord. Maritime Affairs, 13(2), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2017.1412098

- Nohara, J. J. (2017). Sea power as a dominant paradigm: The rise of China’s new strategic identity. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 6(2), 210–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2017.1391623

- Noor, E., & Daniel, T. (2016). NASSP issue brief series: Key issues and dilemmas for Brunei and Malaysia in the South China Sea Dispute. National Asian Security Studies Program (NASSP) and the UNSW Canberra at the Australian Defence Force Academy. https://www.unsw.adfa.edu.au/NASSP

- Oba, M. (2019). Further development of Asian regionalism: Institutional hedging in an uncertain era. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 8(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2019.1688905

- Odgaard, L. (2003). The South China Sea: ASEAN’s Security Concerns about China. Security Dialogue, 34(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/09670106030341003

- OEC. (2020). China (CHN) and Brunei (BRN) Trade | OEC - The Observatory of Economic Complexity. The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from. https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-country/chn/partner/brn

- Pemmaraju, S. R. (2016). The South China Sea arbitration (The Philippines v. China): Assessment of the award on jurisdiction and admissibility. Chinese Journal of International Law, 15(2), 265–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/chinesejil/jmw019

- Qi, H. (2019). Joint development in the South China sea: China’s incentives and policy choices. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 8(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2019.1685427

- Ripsman, N. M., Taliaferro, J. W., & Lobell, S. E. (2016). Neoclassical realist theory of international politics. Oxford University Press.

- Rose, G. (1998). Review: Neoclassical Realism and Theories of Foreign Policy. World Politics, 519(1), 144–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100007814

- Rüland, J. (2005). The Nature of Southeast Asian Security Challenges. Security Dialogue, 36(4), 545–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010605060453

- Santino, S., & Regilme, F. (2018). Beyond Paradigms: Understanding the South China Sea Dispute Using Analytic Eclecticism. International Studies, 55(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0020881718794527

- Sarkar, U. (2014). BRICS: An Opportunity for a Transformative South? South Asian Survey, 21(1–2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971523115592495

- Sato, K. (2013). The Rise of China’s Impact on ASEAN Conference Diplomacy: A Study of Conflict in the South China Sea. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 2(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2013.11869064

- Schweller, R. L. (2004). Unanswered Threats: A Neoclassical Realist Theory of Underbalancing. International Security, 29(2), 159–201. https://doi.org/10.1162/0162288042879913

- Shumei, L. (2018). China, Brunei to enhance ties under Belt and Road initiative - Global Times. Global Times website. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1127878.shtml

- Singh, S., & Yamamoto, L. (2017). China’s artificial islands in the south China sea: Geopolitics versus rule of law. Revista De Direito Econômico E Socioambiental, 8(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.7213/rev.dir.econ.soc.v8i1.7451

- Storey, I. (2014). Disputes in the South China Sea: Southeast Asia’s Troubled Waters. Politique Etrangere, Autumn Issue, 1(3), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.3917/pe.143.0035

- Suehiro, A. (2017). China’s offensive in Southeast Asia: Regional architecture and the process of Sinicization. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 6(2), 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2017.1391619

- Syailendra, E. A. (2017). A nonbalancing act: Explaining Indonesia’s failure to balance against the Chinese threat. Asian Security, 13(3), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2017.1365489

- Taliaferro, J. W. (2004). Balancing Risks: Great Power Intervention in the Periphery. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/J.CTVV414NR

- Thambipillai, P. (2008). Brunei Darussalam and ASEAN: Regionalism for a small state. Asian Journal of Political Science, 6(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02185379808434116

- Thayer, C. A. (2011). Chinese Assertiveness in the South China Sea and Southeast Asian Responses. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 30(2), 77–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341103000205

- Thayer, C. A. (2016). Vietnam’s Strategy of ‘Cooperating and Struggling’ with China over Maritime Disputes in the South China Sea. Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs, 3(2), 200–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347797016645453

- TO, L. L. (1999). The South China Sea. Security Dialogue, 30(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010699030002004

- Vo Huyen Dung, N. (2020). Opportunities and challenges of ASEAN in the United States’ free and open indo -pacific strategy. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 8(1), 659–665. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2020.8179

- Weatherbee, D. E. (1983). Brunei: The ASEAN Connection. Asian Survey, 23(6), 723-735. http://www.ucpressjournals.com/journal.asp?j=as

- Widyawardhana, H., Ali, Y., & Prasetyo, T. B. (2018). “Wawasan Brunei 2035”: Analyzing The Vision of Brunei Darussalam on National Security and State Welfare. Strategi Perang Semesta, 4(3), 77-94. http://www.bruneiembassy.org

- Wiegand, K. E., & Beuck, E. (2018). Strategic Selection: Philippine Arbitration in the South China Sea Dispute. Asian Security, 14(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2018.1540468

- Xie, Z. (2014). China’s Rising Maritime Strategy: Implications for its Territorial Disputes. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 3(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2014.11869077

- Xinhua. (2016). Brunei states commitment to peace in South China Sea: Official - Global Times. Global Times website. Global Times. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/994541.shtml

- Xue, L. (2016). China’s Foreign Policy Decision-Making Mechanism and “One Belt One Road” Strategy. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 5(2), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2016.11869095

- York, M. (2015). Asean’s ambiguous role in resolving South China sea disputes. Jurnal Hukum Internasional, 12(3), 286-310. www.dfa.gov.ph/index.php/2013-06-27-21-50-36/dfa-releases/3856-secretary-del-

- Yoshikawa, S. (2016). China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative and Local Government. Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies, 5(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/24761028.2016.11869098

- Zakaria, F. (1991). Realism and Domestic Politics: A Review Essay. International Security, 17(1), 177–198. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539162

- Zakaria, F. (1998). Realism and America’s Rise: A Review EssayFrom Wealth to Power: The Unusual Origins of America’s World Role. International Security, 23(2), 182. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539382

- Zhen, L. (2018). China and Brunei to step up oil and gas development in disputed South China Sea | South China Morning Post. South China Morning Post. Retrieved September 5, 2020, from. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/2173959/china-and-brunei-step-oil-and-gas-development-disputed-south

- Zhou, W., & Esteban, M. (2018). Beyond balancing: China’s approach towards the belt and road initiative. Journal of Contemporary China, 27(112), 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1433476