Abstract

Globally, there have been significant changes in women’s reproductive behaviour that have had profound effects on population growth. Despite declining fertility in South Africa in recent years, population growth is yet to slow down. This study examined patterns of childbearing in contemporary South Africa. Specifically, it investigated the prevalence of fertility among women of different relationship status and its associated social, economic, and cultural factors. Cross-sectional survey data from 6,124 responses of women in the reproductive age (15–49 years old) to the 2016 South African Demographic and Health Survey were used to decompose fertility into its constituent parts and analysed using binary logistic regression techniques. The findings showed that both marital and nonmarital childbirths significantly contribute to the overall fertility levels in South Africa. Moreover, the results showed that race, ethnicity, household size, age at first sex and contraceptive use were risk factors for childbearing among South African women of childbearing age, while younger age, increased education and wealth were found to be protective factors against childbearing. Policy implications of the findings are discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The total number of children women give birth to have a direct impact on a country’s population size. Traditionally, researchers have focused on how marriage affects fertility because it was assumed that childbearing mostly happens within marriages. However, because marriages are increasingly reducing or being delayed in South Africa, it cannot be concluded that women are necessarily not having children. The 2016 South African demographic and health survey was used to investigate the kind of women who are having children and the relationship context within which they are having these children. The results showed that childbearing in and out of socially recognised marriages are happening simultaneously, although women who have never married contribute more to current fertility levels in South Africa. Further, women who have children are likely to be poor, African, have low education, live in larger households, have started sexual activities early, and use some form of contraceptives.

1. Introduction

Between 1990 and 2019, the global fertility level has fallen from 3.2 to an average of 2.5 children per woman (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA/Population Division), Citation2020). Despite the apparent global trend of fertility decline, it has been estimated that the world’s population will increase in the coming decade (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA/Population Division), Citation2019). However, the size and pace of this fertility growth will be unevenly distributed as most of it is expected to occur in the global South, particularly sub-Saharan Africa. This projection is alarming considering that fertility remains high in this region, with a total fertility rate of 4.6 children per woman (UN DESA/Population Division, Citation2019). An increase in the population, however negligible, poses great challenges in efforts to achieve a number of the Sustainable Development Goals (UN DESA/Population Division, Citation2019). To avoid any adverse impact of rapid population growth on the development agenda, policymakers have introduced varied interventions—including improved access to contraceptive to all population groups and sex education—to influence fertility rates and patterns. Globally, the number of women of childbearing age using some form of contraception has increased from 42 to 49 per cent in the last two decades (UN DESA/Population Division, Citation2020).

In light of these interventionist efforts, notable fertility declines are being registered in some parts of sub-Sahara Africa, albeit relatively slower and delayed (UN DESA/Population Division, Citation2020). South Africa has one of the lowest fertility rates in the region, with an average national fertility rate of 2.4 children per woman (Macrotrends, Citation2020). In addition to this low total fertility, South Africa scores high on most of the observed determinants of fertility decline. Observably, South African women of reproductive age are increasingly delaying marriage and their first births, extending the interval between subsequent births, and using some form of modern contraception (National Department of Health (n.d.oH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) & ICF, Citation2019). Despite this trend, South Africa is also a fairly high-populated country, with over 58 million people and counting (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA/Population Division), Citation2017).

The steady decline of fertility rate in South Africa from 2.8 to 2.4 births per woman over the last two decades is a positive trend in the right direction (Macrotrends, Citation2020). However, more needs to be done to control the current population size effectively. In this respect, a more nuanced understanding of what is driving the current fertility is needed for targeted policy interventions. A detailed analysis of fertility has important implications for family and welfare policing as fertility patterns can affect family functioning and the wellbeing of family members. For instance, some researchers have found that nonmarital fertility plays a role in the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic inequality (Crosnoe & Wildsmith, Citation2011). In other words, children born to unmarried or single mothers are more likely to be raised in poverty and therefore at a greater risk of poor outcomes compared to children born to married women (Crosnoe & Wildsmith, Citation2011; Posel & Rudwick, Citation2012).

In light of the above, this study seeks to investigate in detail fertility patterns in South Africa using a nationally representative sample of reproductive women. This study is distinct in that it decomposes fertility into its constituent parts, allowing for separate and detailed analysis of each component. In doing so, the study population is categorised into three childbearing groups based on their relationship status—namely nonmarital, cohabiting and marital—with the view of explaining their relative contributions to the observed fertility level in South Africa. This allows for a closer examination of the changing patterns of childbearing and the social, economic, and cultural conditions driving women’s childbearing behaviour. For purposes of this study, nonmarital births relate to births to never-married women; cohabitating births relates to births to women who are living together with a partner as if married; and marital births relates to births to ever-married women, including those divorced, separated or widowed.

2. Theoretical framework and literature review

In the demographic literature, several fertility theories exist to help identify important determinants and variables that describe and explain changes in fertility levels, and by extension the determinants of population growth, in a given society or population. However, these theories differ in their hypotheses and methods, owing to diverse discipline influences. This invariable means that no single theory comprehensively captures all the fertility determinants. Nonetheless, fertility theories converge on the idea that the level of fertility in any population is affected by many social, economic, cultural and geographical factors.

In the context of fertility patterns, perhaps the one suitable attempt that closely explains changing birth patterns is the second demographic transition (SDT) theory. Though initially developed to analyse changes in marital attitudes and fertility patterns primarily in the developed western world (see e.g., Surkyn & Lesthaeghe, Citation2004), it can prove useful in developing contexts. The SDT framework helps examine changes in reproduction levels through the prism of marriage, childbearing and contraception (Susel, Citation2005). Thus, emerging trends such postponement of marriage and motherhood, rising alternative forms of partnerships, motherhood outside marriage, and widespread accessibility to family planning help explain changes in fertility levels, patterns and ultimately population growth (Susel, Citation2005). Accordingly, the ensuing review analyses the above assumptions of the SDT and draws heavily on empirical studies that relate to aspects of the framework in identifying determinants of fertility levels.

The assumptions of “marriage” and “fertility” in the SDT are interconnected as marital patterns invariably affect fertility patterns. Fertility and marriage have been theoretically and empirically linked, in that marriage directly influences fertility (Bongaarts, Citation2015). This is because most societies normatively restrict childbearing to marriage (Fletcher & Polos, Citation2017; Harwood-Lejeune, Citation2001). In this respect, married women are expected to contribute significantly to fertility due to their exposure to the risk of pregnancy and childbearing (Chola & Michelo, Citation2016; Palamuleni et al., Citation2007). This assertion, however, presumes that there is no fertility outside marriage. As a proximate determinant, changes to marriage patterns invariably change childbearing patterns (Ahmed, Citation2020). Consequently, delayed or nonmarriage should ideally reduce exposure to the risk of pregnancy and subsequently reduce total fertility.

Empirically, nonmarriage has been identified as playing a substantial role in the low fertility rates in some parts of the world (Jones, Citation2007). Notwithstanding the implications of nonmarriage on fertility levels, nonmarriage alone does not necessarily help in explaining declining fertility in places like South Africa. This is because the 2016 demographic and health survey indicates that a significant proportion of South African women—six in 10 women—have never been married or lived together with a partner as if married (NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC & ICF, Citation2019). This, suggests that active childbearing does not necessarily only occur within the context of marriage. A significant proportion of childbearing may be occurring outside of socially recognised marital unions. Given the low prevalence of marriage in South Africa (Garenne, Citation2016), we expect to find the proportion of women who have never been married but have children to be quite high compared to cohabiting or married women.

Another crucial assumption of the SDT relates to the availability and accessibility to family planning in shaping women’s reproductive decisions, behaviours and outcomes. Contraception is a key determinant that has a direct effect on fertility, either in timing or quantum (Bongaarts, Citation2015). Unlike marriage, however, contraception use is a fertility-constraining behaviour in that increased use of contraception is expected to drive down total fertility (Cheng, Citation2011). Since the use of reliable contraceptives reduces the number of unplanned pregnancies (Secura et al., Citation2014), it is expected that contraceptive use will decrease the odds of childbearing for all women, relationship status notwithstanding. In the South African context, there is a low contraceptive prevalence as less than half (48%) of women of reproductive age are using a contraceptive method (NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC & ICF, Citation2019). This is surprising bearing in mind that knowledge of contraceptives is universal in South Africa, and contraceptives are widely and publicly available at no cost. This means that there is a strong prospect of incidences of unplanned or mistimed pregnancies emanating (mostly nonmarital) from the 52% who are not using any method of contraception. Accordingly, we expect to find the proportion of women who are not using contraceptives and have given birth to be high across all relationship type.

Moreover, a closer inspection of age-specific fertility rates may help piece together the fertility puzzle. Some studies focusing on the age structure of nonmarital and marital births indicated that the vast majority of nonmarital childbearing is by younger women (Fletcher & Polos, Citation2017). Conversely, other studies have found that fertility increases with women’s age, for both married and unmarried women (Bbaale, Citation2014). In South Africa, current age-specific fertility rates indicate relatively high fertility among young South African women as 16% of adolescent women aged 15–19 have begun childbearing (NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC & ICF, Citation2019). In South Africa, because early marriage is uncommon, almost all adolescent childbearing is nonmarital, that is to women who have never been married (Branson & Byker, Citation2018; Makiwane & Chimere-Dan, Citation2009; Marteleto et al., Citation2008). Given the low prevalence of marriage and the high rate of sexual activity among South African young women, nonmarital fertility is generally higher amongst younger women compared to older women (Mturi, Citation2015; Nzimande, Citation2005). In this respect, we expect the age profile of married and cohabiting mothers to be much higher than single mothers.

Linked to age is the role of the timing of first sex in shaping total fertility as well as fertility patterns. Early sexual debut predisposes women to the risk of pregnancy, including unintended and adolescent pregnancy (Ajala, Citation2014; Baumgartner et al., Citation2009). For instance, Manlove and Mincieli (Citation2006) study of American youths aged 15–29 found that females who initiated their first sex at younger ages had greater odds of first nonmarital birth. In this study, we expect to find women who begin sexual activities early, before age 14, to contribute more to nonmarital births.

Additionally, lifestyle indicators such as socioeconomic status (SES) (i.e. education, employment, wealth) and geographical location play a role in determining fertility. First, there is an established empirical negative relationship between female education and total fertility, with studies showing that fertility generally decreases with women’s increased education (Bbaale, Citation2014; Frank, Citation2017). Further, increased education reduces the likelihood of women being married (Bbaale, Citation2014). Since better-educated women are more likely to delay marriage and childbearing, we expect to find an association between the educational level of mothers and childbearing in and outside of marriage. A previous study in South Africa found women with low education have increased odds of nonmarital fertility (Maluleke, Citation2017). Premised on the protective effect of education, we expect better-educated women to have lower odds of births, irrespective of relationship status.

Similarly, female wage employment is associated with a reduction in fertility, as active employment affects women’s childbearing decisions in favour of fewer children (Bbaale, Citation2014; Sibanda & Zuberi, Citation2005). In South Africa, research has shown that unemployed women have increased odds of nonmarital fertility (Maluleke, Citation2017). Since motherhood and employment are competing roles (Sibanda & Zuberi, Citation2005), we anticipate that unemployed women will be overrepresented among all fertility types compared to the employed.

Moreover, studies have shown that generally, women with higher incomes have lower fertility than those with lower incomes (Frank, Citation2017). In particular, women of lower socioeconomic status or lower family income are more likely to have children outside marriage (Crosnoe & Wildsmith, Citation2011; Upchurch et al., Citation2002). In this study, we expect increased wealth index to be a protective factor against fertility, particularly nonmarital and cohabiting births.

Broadly speaking, urbanisation has been identified as playing a key role in fertility reduction since total fertility is decreasing more rapidly in urban areas (Ayele & Melesse, Citation2017). Several studies have observed significant variation in fertility level among rural and urban residents, with women living in rural areas having higher fertility compared to women who live in urban areas (Ayele & Melesse, Citation2017; Bbaale, Citation2014). A study of premarital births and union formation in rural South Africa found that single motherhood is common in rural South Africa as 45% of the women have had a premarital first birth (Sennott et al., Citation2016). However, since rural women marry relatively early in South Africa (Maluleke, Citation2017), we expect to find a higher level of marital, and to some extent cohabitation births from rural women, and a corresponding higher level of nonmarital births from urban women.

Similarly, we anticipate provincial differences in fertility patterns. A previous study on South African youths aged 15–24 years found that nonmarital adolescent childbearing is particularly high in KwaZulu Natal, North West, Limpopo and Gauteng provinces (Makiwane & Chimere-Dan, Citation2009). We expect a similar trend across all women in this study. Further, while no studies are focusing explicitly on women’s childbearing behaviour and household size, a study of 43 developing countries found the household size to be positively associated with the level of fertility (Bongaarts, Citation2001). In this study, we expect to see some residential differential in fertility patterns and levels among women based on the size of the household they live in, with all women from larger households having children, irrespective of their relationship status.

Finally, culture, using race and ethnicity as proxies, plays a role in the pace of family formation and childbearing generally (Lailulo & Susuman, Citation2018). For example, an examination of race-ethnic differentials in nonmarital fertility, albeit predominately in the U.S., indicate that African Americans and Latinos are at a greater risk of a nonmarital birth compared to white women (Crosnoe & Wildsmith, Citation2011; Kim & Raley, Citation2015; Manlove & Mincieli, Citation2006). In the South African context, observed racial differences in patterns of union formation, where the prevalence of marriage is lower among Africans, are reflected in racial differences in fertility levels and patterns (Moultrie & Timæus, Citation2001; Posel & Rudwick, Citation2012). Previous studies show that nonmarital fertility varies by race, with high nonmarital births amongst Africans and coloured population groups (Makiwane & Chimere-Dan, Citation2009; Maluleke, Citation2017; Nzimande, Citation2005). Since marriage rates are substantially lower among African women in the country (Posel & Rudwick, Citation2012), we expect African women will likely be disproportionately among those involved in nonmarital and cohabitation births.

However, the use of race as a proxy for culture has been criticised as masking important differences between groups (Madhavan et al., Citation2013). In light of this criticism, we go a step further in our analysis to include ethnicity as a measure of culture and measured by home language spoken. Previous studies have used ethnicity to show differences in fertility among black South Africans. For instance, Sibanda and Zuberi (Citation2005) found that Swazi, Venda, Ndebele, Northern Sotho and Tsonga women have lower mean ages at first birth than the average for all Africans. In an unrelated study, Maluleke (Citation2017) found increased odds of nonmarital fertility among Xhosa and Zulu (Nguni) women. Thus, we expect to see significant ethnic variations in the childbearing patterns of women.

Given the variations in the demographic, socioeconomic and cultural factors discussed above which create the contexts for women’s childbearing behaviour, the present study will test the impact of these sociodemographic factors using the 2016 South African Demographic and Health Survey data. Consistent with the study’s design, we contend that the impacts of the sociodemographic factors will be different for women based on their relationship status. This is because the existence of a partnership, or lack thereof, has strong bearings on the formation of fertility intentions and by extension behaviour (Philipov et al., Citation2005).

3. Data and methods

3.1. Sample

The data for the study comes from the 2016 South Africa Demographic and Health Survey (SADHS). The survey is a nationally representative two-stage cluster sample designed to deliver reliable information on population and health indicators at all levels. Enumeration areas from the 2011 population census were either pooled or divided to form the primary sampling unit (PSU) with 468 urban PSUs, 224 traditional areas PSUs and 58 farm areas PSUs sampled, stratified by province. A total of 8,514 individual women aged 15 to 49 years are drawn but only 6124 of the women who meet the study criteria are included in the analyses.

3.2. Measures

Outcome variable: The dependent variable of interest for this study is children ever born. This information is obtained by asking women to indicate the total number of children ever born at the time of the survey. The responses are recoded and dichotomized as: “0 = no birth” and “≥ 1 = birth(s)”. Women having at least one living child are considered for further analysis in this study.

Independent variables: The explanatory variables of interest in this study include age, race, ethnicity, educational level, employment status, wealth index, place of residence, province of residence, number of household members, age at first sex, and contraceptive use. All independent variables are categorised. For instance, Age is categorised into 5-year gaps as “15–19”, “20–24”, “25–29”, “30–34”, “35–39”, “40–44” and “45–49”. Race is dichotomized into “Black African”, “Others”. Ethnicity is measured using home language spoken as proxy and includes the following response alternatives, “English”, “Afrikaans”, “Nguni”, “Sotho” and “Tshivenda/Xitsonga”. Level of education is categorised into “below secondary”, “secondary education” and “higher education”. Employment status is dichotomized as “unemployed” and “employed”. Wealth index is categorised into “poorer”, “middle” and “richer”. Place of residence is dichotomized into “urban” and “rural”. Province of residence is categorised into the nine provinces: “Western Cape”, “Eastern Cape”, “Northern Cape”, “Free State”, “KwaZulu-Natal”, “North West”, “Gauteng”, “Mpumalanga” and “Limpopo”. Household size is categorised into “1–2 people”, “3–5 people” and “6+ people”. Age at first sexual debut is dichotomized as “≤ 14 years (early debut)” and “> 14 years”. Finally, contraceptive use is dichotomized into “no” and “yes”.

3.3. Analysis

The study uses three levels of statistical analysis; univariate, bivariate and multivariate. The univariate section focuses on the distribution of sociodemographic factors of the respondents using descriptive statistics. The second stage is a bivariate analysis to evaluate the sociodemographic factors associated with fertility by relationship status, using p-value < 0.05 as the condition for significance. The last stage of the analysis involves a series of multivariate investigation to identify predictors of fertility by relationship status.

First, a multicollinearity diagnostic test is performed to test for collinearity, if any. Thereafter, forward stepwise model selection is used to pick significant variables for the final analysis. Finally, a binary logistic regression model is used in estimating the influence of selected sociodemographic variables in predicting the risk of childbearing according to women’s relationship status. The results are interpreted using the Odds Ratios (ORs), and variables are deemed to be significantly predicting births if the p-value associated with the ORs is less than 0.05. All variables are adjusted for each other simultaneously in one model and analysed using SPSS version 25.

4. Results

4.1. Background characteristics

shows the distribution of the characteristics of the sample. The results show that single or never-married women constitute three-fifths (60.3%) of the sample, while slightly over a quarter (27.8%) are ever-married, and just over a tenth (11.9%) are cohabiting. Further, slightly more than one-sixth (17.7%) of them are in the 15–19 years cohort; and just under one-sixth are in the 20–24-year (16.5%) and 25–29-year (16.4%) cohorts. The majority (86.4%) of the respondents are black Africans, with the rest (13.6%) constituting other racial groups. The ethnic breakdown shows that over a third of the respondents identify as Nguni (38.5%) and Sotho (35.3%); a tenth (10.1%) are English, 8.6% Afrikaans and 7.5% are Tshivenda/Xitsonga.

Table 1. Percentage distribution of married women by selected socioeconomic and demographic characteristics on relationship status

In terms of the human capital indicators, over three-quarters (77.3%) of the respondents have secondary level education, over three-fifths (63.5%) are unemployed, and about two-fifths (42.6%) are in the poor wealth index. Slightly more than half (56.4%) of the respondents reside in urban areas; more than two-fifths (47.7%) reside in a 3-5-person household; just over one-seventh (16%) reside in KwaZulu-Natal province and about one-eighth residing in Limpopo (13%), Mpumalanga (12.4%) and Eastern Cape (12.2%) provinces. Lastly, nearly all (93.9%) of the women report having started sexual activities after age 14 years; with over two-fifths (47.3%) using some form of modern contraception.

Finally, a striking pattern emerges within the never-married group. Single women are significantly overrepresented among the very young (15–24 years), unemployed, the poor, rural residents, Kwa-Zulu Natal residents, those living in larger households (6+ people), and those who do not use any contraceptives.

4.2. Patterns of fertility in South Africa

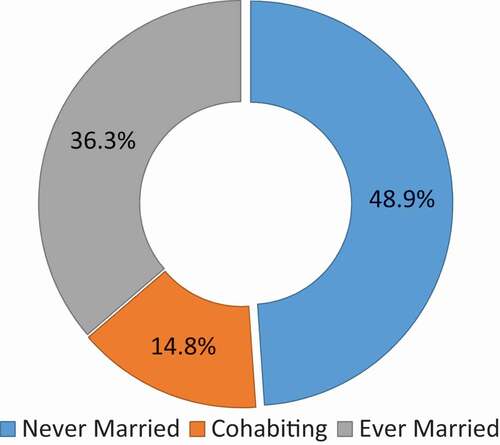

The analysis shows that five out of every seven (71.9%) women of reproductive age (15–49 years) report bearing one or more children (). There are substantial variations in the patterns of childbearing in South Africa. Among the proportion of women reporting childbirths, nearly half (48.9%) are nonmarital births, slightly more than one-third (36.3%) are marital births and about one-seventh (14.8%) are cohabitation births ().

Figure 1. Schematic framework showing the percentage distribution of children ever born by relationship status. Source: Authors’ computation from SADHS (Citation2016)

shows the distribution of the mean number of children ever born to the women by selected socio-demographic factors. Variations in fertility are noted by all selected socio-demographic variables. According to , fertility increases with age across all relationship statuses. The mean number of children ever born is higher among never-married and ever-married African women compared to other race groups. Among the never-married women, fertility is highest among Tshivenda/Xitsonga women, followed closely by Afrikaans-speaking women, then Nguni and Sotho women, and lowest for English-speaking women. However, among the cohabiting, English women have the highest fertility and the lowest for Tshivenda/Xitsonga women. Among the ever-married women, Nguni women have the highest fertility, whilst Tshivenda/Xitsonga women have the lowest.

Table 2. Mean number of children ever born to women by selected sociodemographic factors

Fertility also varies by women’s SES (level of education, employment status, household wealth) as well as place and province of residence. For the level of education, fertility decreases with increased education, with the mean number of children ever born higher among women with less than secondary level education, irrespective of relationship status. Never-married employed and unemployed ever-married women have higher fertility, whilst there is no variation among cohabiting women. Poorer women have higher fertility across all relationship statuses. Compared to urban residents, rural women have a higher mean number of children ever born, regardless of relationship status. Lastly, unmarried women in North West, cohabiting women in Kwa-Zulu Natal, and ever-married women in Mpumalanga and Eastern Cape provinces have relatively higher fertility.

Finally, fertility is affected by the number of people who co-reside with a woman, the woman’s age at first sex and contraceptive use. Women living in a 6+ people households have a higher mean number of children ever born, irrespective of relationship status. Similarly, women who initiated sex before age 14 years have higher fertility generally. Finally, cohabiting and ever-married women who use contraceptives, as well as never-married women who do not use contraceptives, have higher fertility.

presents the results of the bivariate model showing the association between childbearing and selected sociodemographic factors by relationship status. Generally, women’s age, race, household size and contraceptive use are significantly associated with childbearing generally (). Fertility increases with women’s age, peaking at 35–39 years, relationship status notwithstanding. Similarly, fertility is higher among black African women, irrespective of relationship status. Lastly, fertility is higher among women living in larger households and those using contraceptive across different relationship statuses.

Table 3. Bivariate association of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics and fertility with relationship status

When broken down into its constituent parts, the results further show that non-marital fertility is significantly associated with all the explanatory variables explored, including age, race, ethnicity, level of education, employment status, wealth, place and province of residence, household size, age at sexual debut, and contraceptive use. Disaggregation by sociodemographic characteristics shows that women in the 35–39 age cohort (91%) are overrepresented among women who have nonmarital births. Black African women (59.7%) and Tshivenda/Xitsonga women (69.9%) are overrepresented among women who have nonmarital births. Similarly, employed women (78.7%), poor women (62.8%) and women with less than secondary level education (68.5%) are overrepresented among women who have nonmarital births. Likewise, rural residents (60.9%), women living in larger households (6+ people) (61.5%) and those living in North West province (63.9%) are overrepresented among women who have nonmarital births. Finally, women who started having sex before 14 years (74.4%) and those using contraceptive (76.8%) are overrepresented among women who have nonmarital births.

also shows that cohabitation fertility is significantly associated with age, race, level of education, employment status, household size and contraceptive use. Further, women aged 35–39 years (94.1%), African women (91.2%), English and Tshivenda/Xitsonga women (91%), those with less than secondary level education (92.1%), the employed (91.7%), the poor (91.3%), urban residents (91.5%), those living in Kwa-Zulu Natal (92.6%), those living in a 3-5-person household (95.5%), those who started sex early (90.1%), and those using contraceptive (95%) are disproportionately represented among those cohabiting with children.

Finally, marital fertility is significantly associated with age, race, ethnicity, wealth, place and province of residence, household size, and contraceptive use. Specifically, older women (≥35 years) (95%), black African women (95.4%), Nguni women (96%), women with secondary level education or lower (94%), the employed (94.3%), the poor (95.6%), rural residents (96.2%), women living in Limpopo province (97.1%), those living in larger households (6+ people) (98%), and those using contraceptive (97.6%) account for most of the marital fertility.

4.3. Multivariate results

presents the results of the bivariate logistic regression model showing odd ratios predicting factors associated with different fertility types among South African women of reproductive age. First, the results show that, generally, age, household size and contraceptive use play significant roles in predicting fertility behaviour among women, regardless of relationship status. In particular, younger age has a protective effect against childbearing, as younger women aged 15–24 years significantly less likely to have more children compared to older persons.

Table 4. Multivariate model using binary logistic regression technique predicting fertility by relationship status controlling for selected socioeconomic characteristics

Increased household size and contraceptive use are risk factors for childbearing among South African women. Women living in larger households with three or more people are significantly more likely to have children irrespective of relationship status. However, the odds of marital childbirth are greater for women living in 6+ people (OR = 26.87) and 3-5-person (OR = 13.61) households. Similarly, women using contraceptive are significantly more likely to have children, with the odds greater for cohabiting (OR = 5.45) and ever-married (OR = 5.06) women.

The results also show that race, ethnicity and age at first sex are significant risk factors for childbearing among South African women. Particularly, black African women are significantly more likely to have cohabiting (OR = 5.05) and marital (OR = 3.25) births. Regarding ethnicity, Nguni women are significantly more likely to have more? Marital births (OR = 2.11). Lastly, women who start sexual activities early (before age 14) are significantly more likely to have nonmarital births (OR = 2.51).

Lastly, increased education is a protective factor against nonmarital and cohabitating births. Specifically, women with more than secondary-level education are significantly less likely to be single mothers (OR = 0.64) or have children while cohabiting (OR = 0.24). Likewise, increased wealth is a protective factor against both nonmarital and marital births. Particularly, women in the middle (OR = 0.69) and richer (OR = 0.46) wealth indices are significantly less likely to give birth whilst single. Also, women in the richer wealth index are less likely to have marital births (OR = 0.43).

5. Discussion

Undoubtedly there has been a notable decline in the total fertility in South Africa in the last four decades (Rossouw et al., Citation2012). While this is a positive development, the total fertility decline does not fully portray the reproductive behaviour of South African women. Consequently, the fertility behaviours of a nationally representative sample of 6124 of women in the reproductive age were assessed to get a better understanding of how socio-demographic contexts help us to understand their childbearing behaviours. In doing so, fertility was decomposed into its constituent parts and each component is analysed separately and in detail.

One way of understanding the current fertility trend is to examine the role of marriage and contraception as proximate determinants of fertility. First, the diminishing rate of marriage in South Africa is not necessarily leading to a reduction in fertility. The results of the present study have indicated that the level of fertility for women who have never been married is quite high. Coupled with the number of cohabitation births, it is clear that a substantial proportion of childbearing occurs outside socially recognised marital unions. This may suggest that marriage may not be an important condition for childbearing in South Africa as it is elsewhere in the region. Our results suggest that the recent total fertility decline in the country is likely to be attenuated by emerging patterns of premarital or nonmarital childbearing.

Contraceptive use significantly predicted fertility among South African women but not in the expected direction. Generally, contraception is a fertility-constraining behaviour so its use should reduce incidences of pregnancy and childbirth (Secura et al., Citation2014). However, we found that contraceptive use was a risk factor for childbearing for South African women. Our results showed that women using contraceptives were significantly more likely to have children, with the odds greater for cohabiting and ever-married women. This finding was confirmed by the estimate of fertility by contraceptive usage, where cohabiting and ever-married women had a higher mean number of children ever born compared to non-users. Our results indirectly corroborate findings from Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania, where women who used contraceptives were found to have higher mean births (Ayele & Melesse, Citation2017). This finding of the effect of contraceptive use on fertility points to issues of improper use or inconsistent use than, say, contraceptive failure.

Aside from the changing role of the proximate determinants of fertility, the study identified several individual, social, economic and cultural factors that affect women’s childbearing behaviours. First, we found significant age patterns in childbearing. Women’s age, particularly younger age, had a protective effect against childbearing generally. Younger women, mostly 15–24-year olds, were significantly less likely to have children compared to older persons, irrespective of relationship status. Contrary to existing evidence in the literature, the age structure of nonmarital, cohabiting and marital births did not differ much. Further, differentials in fertility were found regarding women’s age, with the mean number of births increasing with age for all women regardless of relationship status. Nonetheless, our results support Bbaale’s (Citation2014) finding in Uganda, where fertility was observed to increase with age for both married and unmarried women.

Related to age is the timing of women’s first sexual encounter. As expected, we found that early sexual debut was a risk factor for nonmarital births. Specifically, unmarried women who started sexual activities before age 14 were significantly more likely to have children. The mean number of children ever born was higher among women who had begun sexual activities early across relationship status. This relationship of age at first sex and fertility is unsurprising since sexual activity at a young age is invariably unsafe owing to limited knowledge of reproductive health information, some misconceptions about human reproduction, as well as a lack of emotional maturity to negotiate for safer sex (Biney et al., Citation2020).

Race, ethnicity and household size were found to be risk factors for childbearing among South African women. Regarding race, black African women were significantly more likely to have cohabiting and marital births compared to other race groups. Moreover, our results showed that Nguni women were significantly more likely to have marital births. Further, our estimation shows that fertility is generally higher among African women and married Nguni women specifically. Palamuleni (Citation2014), has argued that the racial and ethnic differences in reproductive behaviour can be explained by cultural influences on marriage and fertility among these groups. Despite the persistence of pro-natalist ideologies in many African communities, many have culturally sanctioned procedures regulating childbearing, which make nonmarital births undesirable (Bimha & Chadwick, Citation2016; Madhavan et al., Citation2013). Also, in a context where motherhood is a normative perquisite of femininity (Bimha & Chadwick, Citation2016), having children is likely to rate high on the list of women’s achievements, hence the high fertility among this group.

The present study found that generally women who lived in larger households, that is with three or more people, were significantly more likely to have children on the whole. In particular, married women living in 6+ people and 3-5-person households were significantly more likely to contribute to fertility levels. Estimates of fertility by household composition also confirms this as fertility is higher in larger households. This finding corroborates that of Bongaarts (Citation2001) study of 43 developing countries in which household size was positively associated with the level of fertility.

Consistent with the literature, increased education and wealth are protective factors against childbearing, particularly nonmarital births. Specifically, we found that women with higher education were significantly less likely to procreate whilst single or whilst cohabiting. Further, higher educated women had a lower mean number of children ever born compared to those with secondary level or lower. This supports Upchurch et al. (Citation2002) finding that the risk of nonmarital conception increases after a woman leaves school. In any case, education is a competing activity with childbearing, thus better/higher educated women are likely to trade-off their time for childcare for work and earnings (Bbaale, Citation2014).

Women in the middle and richer wealth indices were significantly less likely to be single mothers. This corroborates Upchurch et al.’s (Citation2002) finding in the U.S. that the risk of nonmarital conception was significantly lower for women with higher family income. Women from richer wealth index were significantly less likely to have marital births. The results suggest that richer women, in particular, have the lowest fertility, across relationship status. The effect of increasing household wealth on fertility could be because wealth makes varied lifestyles possible. There is also a strong possibility that wealthier women are voluntarily choosing to have fewer children based on some perceived associated benefits (Bimha & Chadwick, Citation2016).

Interestingly, however, employment status, place and province of residence did not significantly explain variations in fertility patterns in South Africa as suggested by previous studies. Given the impact of education on childbearing, it is surprising that employment did not have a similar effect. Perhaps, it is not employment per se but the type or the quality of employment that makes a difference, although this is something we could not test with our data. Moreover, given the variations in fertility observed at both residential and provincial levels, it is surprising that both variables were not significant in the multivariate model.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to the literature on fertility transition in sub-Saharan Africa. Unlike other cross-sectional studies that explore fertility as a singular measure, this study decomposed fertility into its constituent parts to examine in detail childbearing patterns in contemporary South Africa. While both marital and nonmarital childbirths significantly contribute to the overall fertility levels in South Africa, the proportion of never-married women having children is quite high and likely to increase.

In conclusion, the present study has underscored the fact that the traditional African family, as defined by the presence of a large number of children, is transforming as a result of modernising influences such as formal education, wage employment and its associated wealth. However, this transformation of the traditional African family is far from being linear as a result of such patterns as Africans’ preference for extended family living and scepticism about using modern contraception.

Policy implications

To the extent that the recent fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa is a desirable outcome in the face of the prospects of population growth, policy interventions to facilitate this end state should include empowerment measures such as promoting girl-child education, eliminating discrimination against women in the labour market and educating women about the importance of effective modern contraceptive methods.

First, policies that promote more uptake of family planning among women should continue and be strengthened to increase contraceptive prevalence. Age and ethnic differences in childbearing patterns also suggest that family planning programmes need to be more targeted, rather than the current wholesale approach that treats women as a homogenous group. Thus, a concerted effort should target younger women and African women through well-crafted family planning services with ethnic-specific messages, while simultaneously ensuring the availability of contraceptives to all women.

Secondly, the government should continue its efforts in investing in education, job creation and improved opportunities for girls and women outside of childbearing. The social and economic emancipation of women will impact fertility downwards.

Lastly, though our findings make important contributions to the area of fertility research, the analysis adopted in this study is not rigid enough considering the issues being investigated. Nonetheless, this study is a good start in understanding childbearing patterns in a culturally diverse society like South Africa. More studies of this nature are needed. Future studies should attempt to study fertility patterns using qualitative and/or multidisciplinary approach

Study limitations

The present study has some limitations which must be acknowledged. First, the data does not permit the estimation of the completed fertility as some of the women are very young and may only be at the early stages of childbearing. Secondly, the reported age at first sex may have been influenced by social desirability bias, with some possible age misreporting among older women. Lastly, there is a strong possibility that the reported marital births may have started as premarital before transitioning into marriage, but there was no way of ascertaining this information from the data.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Olusegun Ewemooje

Elizabeth Biney and Olusegun Sunday Ewemooje are postdoctoral fellows in the Population and Health Research Entity, Faculty of Humanities, North-West University (Mafikeng Campus), where Acheampong Yaw Amoateng is both a research professor and Director.

The authors are one of several multidisciplinary teams within the Entity. Biney is a socio-legal researcher, Amoateng is a family sociologist, and Ewemooje is a statistician and a lecturer at the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria.

The research reported in this paper forms part of the research focus area as well as the Entity’s aim of scientific contribution in understanding and addressing demography and health-related issues in South Africa and sub-Saharan Africa.

References

- Ahmed, S. S. (2020). Roles of proximate determinants of fertility in recent fertility decline in Ethiopia: Application of the revised bongaarts model. Open Access Journal of Contraception, 11, 33–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S251693

- Ajala, A. O. (2014). Factors associated with teenage pregnancy and fertility in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(2), 62–70. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEDS/article/view/10699

- Ayele, D. G., & Melesse, S. F. (2017). Proximate determinants of fertility in Eastern Africa: The case of Kenya, Rwanda and Tanzania. Scientific Review, 3(4), 29–42. https://ideas.repec.org/a/arp/srarsr/2017p29-42.html

- Baumgartner, J. N., Geary, C. W., Tucker, H., & Wedderburn, M. (2009). The Influence of early sexual debut and sexual violence on adolescent pregnancy: A matched case-control study in Jamaica. International Perspective on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1363/ifpp.35.021.09

- Bbaale, E. (2014). Female education, labour force participation and fertility: Evidence from Uganda. AERC Research Paper 282. African Economic Research Consortium.

- Bimha, P. Z. J., & Chadwick, R. (2016). Making the childfree choice: Perspectives of women living in South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 26(5), 449–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2016.1208952

- Biney, E., Ewemooje, O. S., & Amoateng, A. Y. (2020). Predictors of sexual risk behaviour among unmarried persons aged 15-34 years in South Africa. The Social Science Journal, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2020.1727225

- Bongaarts, J. (2001). Household size and composition in the developing world in the 1990s. Population Studies, 55(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720127697

- Bongaarts, J. (2015). Modelling the fertility impact of the proximate determinants: Time for a tune-up. Demographic Research, 33, 535–559. https://dx.doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.33.19

- Branson, N., & Byker, T. (2018). Causes and consequences of teen childbearing: Evidence from a reproductive health intervention in South Africa. Journal of Health Economics, 57, 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.11.006

- Cheng, K. W. (2011). The effect of contraceptive knowledge on fertility: The roles of mass media and social networks. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(2), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/2Fs10834-011-9248-1

- Chola, M., & Michelo, C. (2016). Proximate determinants of fertility in Zambia: Analysis of the 2007 Zambia Demographic and Health Survey. International Journal of Population Research, 2016, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5236351

- Crosnoe, R., & Wildsmith, E. (2011). Nonmarital fertility, family structure, and the early school achievement of young children from different race/ethnic and immigration groups. Applied Developmental Science, 15(3), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2011.587721

- Fletcher, J. M., & Polos, J. (2017). Nonmarital and teen fertility. IZA DP No. 10833. IZA – Institute of Labour Economics.

- Frank, O. (2017). The demography of fertility and infertility. Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research (GFMER). Retrieved July 31, 2019, from https://www.gfmer.ch/Books/Reproductive_health/The_demography_of_fertility_and_infertility.html

- Garenne, M. (2016). A century of nuptiality decline in South Africa: A longitudinal analysis of census data. African Population Studies, 30(2), 2403–2414. https://doi.org/10.11564/30-2-846.

- Harwood-Lejeune, A. (2001). Rising age at marriage and fertility in Southern and Eastern Africa. European Journal of Population, 17(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011845127339

- Jones, G. (2007). Delayed marriage and very low fertility in Pacific Asia. Population and Development Review, 33(3), 453–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00180.x

- Kim, Y., & Raley, R. K. (2015). Race-ethnic differences in the non-marital fertility rates in 2006-2010. Population Research and Policy Review, 34(1), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-014-9342-9

- Lailulo, Y. A., & Susuman, A. S. (2018). Proximate determinants of fertility in Ethiopia: Comparative analysis of the 2005 and 2011 DHS. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 53(5), 733–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909617722373

- Macrotrends. (2020). South Africa fertility rate 1950–2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/ZAF/south-africa/fertility-rate

- Madhavan, S., Harrison, A., & Sennott, C. (2013). Management of non-marital fertility in two South African communities. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(5), 614–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.777475

- Makiwane, M. B., & Chimere-Dan, G. C. (2009). The state of youth in South Africa: A demographic perspective. HSRC Press.

- Maluleke, N. T. (2017, October 29–November 4). Examining non-marital fertility in South Africa using 1996, 2001 and 2011 census data [Paper presentation]. XXVIII International Population Conference, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Manlove, J., & Mincieli, L. (2006). Family, individual and relationship factors associated with a first nonmarital birth: Analyses by gender and race/ethnicity. Retrieved May 19, 2019, from ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/health_statistics/…/Manlove-Predictingafirstnonmaritalbirth.pdf

- Marteleto, L., Lam, D., & Ranchhod, V. (2008). Sexual behavior, pregnancy, and schooling among young people in urban South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 39(4), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00180.x

- Moultrie, T., & Timæus, I. (2001). Fertility and living arrangements in South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies, 27(2), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070120049930

- Mturi, A. J. (2015). Why young unmarried women bear children? A case study of North West province, South Africa. Collen Working Paper 2/2015. University of Oxford.

- National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), & ICF. (2019). South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016. NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC, & ICF.

- Nzimande, N. (2005). The extent of non-marital fertility in South Africa. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population. Retrieved May 19, 2019, from www.demoscope.ru/weekly/knigi/tours_2005/papers/iussp2005s51576.pdf

- Palamuleni, M., Kalule-Sabiti, I., & Makiwane, M. (2007). Fertility and childbearing in South Africa. In A. Y. Amoateng & T. B. Heaton (Eds.), Families and households in post-apartheid South Africa: Sociodemographic perspectives (pp. 113–133). HSRC Press.

- Palamuleni, M. E. (2014). Social and economic factors affecting ethnic fertility differentials in Malawi. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 3(1), 70–88. www.isdsnet.com/ijds

- Philipov, D., Spéder, Z., & Billari, F. C. (2005). Now or later? Fertility intentions in Bulgaria and Hungary and the impact of anomie and social capital. Working Paper No. 08/2005. Austrian Academy of Sciences & Vienna Institute of Demography.

- Posel, D., & Rudwick, S. (2012, November). Attitudes to marriage, cohabitation and non-marital childbirth in South Africa [Paper presentation]. Micro-econometric Analysis of South African (MASA) Data conference, Durban, South Africa.

- Rossouw, L., Burger, R., & Burger, R. (2012). The fertility transition in South Africa: A retrospective panel data analysis. Development Southern Africa, 29(5), 738–755. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2012.731779

- Secura, G. M., Madden, T., McNicholas, C., Mullersman, J., Buckel, C. M., Zhao, Q., & Peipert, J. F. (2014). Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(14), 1316–1323. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1400506

- Sennott, C., Reniers, G., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., & Menken, J. (2016). Premarital births and union formation in rural South Africa. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42(4), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1363/42e2716

- Sibanda, A., & Zuberi, T. (2005). Age at first birth. In T. Zuberi, A. Sibanda, & E. O. Udjo (Eds.), The demography of South Africa (pp. 65–89). M.E. Sharpe, Inc.

- South Africa Demographic and Health Survey(SADHS). (2016). Retrieved from [email protected]

- Surkyn, J., & Lesthaeghe, R. (2004). Value orientations and the second demographic transition (SDT) in northern, western and southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research, S, 3(3), 45–86. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2004.S3.3

- Susel, A. (2005). An overview of contemporary theories of fertility. Nowy Sącz Academic Review, 2005(2), 24–41. http://hdl.handle.net/11199/245

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA/Population Division) (2017). World population prospects: The 2017 revision, key findings and advance tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP/248. United Nations.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA/Population Division). (2019). World population prospects 2019: Ten key findings. United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_10KeyFindings.pdf

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (UN DESA/Population Division). (2020). World fertility and family planning 2020: Highlights. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/World_Fertility_and_Family_Planning_2020_Highlights.pdf

- Upchurch, D., Lillard, L., & Constantijn, W. A. P. (2002). Nonmarital childbearing: Influences of education, marriage, and fertility. Demography, 39(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2002.0020