Abstract

This systematic review discusses the shifted paradigm in the place-making concept, from being focused on physical changes in the environment (product-oriented) created by urban planners, towards place-making as an iterative process that involves various actors other than the planning professionals. Despite this conceptual re-orientation that was emerged in the 1960s, important discussions, such as factors that support or obstruct the process of place-making are often mentioned incidentally in publications without being systematically analysed across cases. Therefore, this paper aims to bring a better overview of the concept of place-making as a process by combining theoretical and empirical research in the planning context. To achieve this aim, a systematic literature review of 61 articles published between 1960 and 2016 has been used. This research demonstrates a variety of approaches, influential factors, and outcomes of place-making. It points out the importance to take into considerations the interplays among the roles of actors, along with physical-spatial elements of places. These factors should be acknowledged in combination with the others, rather than being treated as unidimensional. Such circumstances not only lead to viable place-making but also bring positive social impacts to local communities, especially on gaining local empowerment, enhancing social ties, reinforcing place identity, and increasing quality of life.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The paper demonstrates a systematic review of place-making from 61 articles published during 1960–2016. The results show that most of the studies only focus in investigating influential factors and general outcomes of place-making without explicitly discussing the relation between them. We therefore recommend a research framework to study the relationship between particular influential factors of place-making and (social) outcomes in a more systematic manner. In the research model, we distinguish three different main categories of factors: (1) local residents-related factors, (2) stakeholders-related factors, and (3) contextual factors. In addition to response our review findings that showed more quantitative and mixed studies are needed, the present model is aimed at a mixed methodology. It can be first tested with a quantitative approach, and the second be clarified further with a qualitative research approach.

1. Introduction

1.1. Paradigm shifting in place-making

Over the years, place-making has been implemented in many different places across the world and been increasingly used in a wide array of disciplines, including geography, planning, architecture, and sociology (John Friedmann, Citation2010). The concept has its origin in urban design which only focuses on physical transformation and end product of places. However, throughout its development, there has been a shift in the place-making concept. This current notion of place-making argues that urban placesFootnote1 are embedded in the built environment and come into being through the reiterative social practices, meanings that are made and remade on a daily basis (Cresswell Citation2004). In other words, place is seen as a process where the setting of place is a product of the users’ activities, and therefore, remaking a place is a social activity that involved peopleFootnote2 (Arefi, Citation2014; Lombard, Citation2014).

The shift in place-making literature has been particularly observed since 1990s, which revolved around the focus of and the decision-making process in place-making (Strydom et al. Citation2018). It changes the responsibility of urban planner from building places to promoting the institutional capacity in communities for (on-going) place-making activities (Healey, Citation1998). This shift cannot be separated by the concept of people-place relationships that was proposed and explored by Jane Jacobs and William Whyte in the 1960s.Footnote3 The critics on the urban design approach—that mainly focused on the physical constructions with slight contribution of local residents, have been supported by other authors who claim that the right to make space is not designated to expert policy-makers and professionals but also a right to residents.

Lefebvre’s co-production of space theory (1991) offered important insights regarding people’s ability to transform a space and vice versa. He states that the actual value of space lies in the human experience that is attached with the space—which he called as “lived space”. In a similar vein, Schneekloth and Shibley (Citation1995) also point out that before design and planning take place, they (design and planning) must be situated and transformed in relations with the people in places. A more current work of Lepofsky and Fraser (Lepofsky & Fraser, Citation2003, pp. 132–133) demonstrates the concept of “flexible citizenship” that place-making is not only for professionals and neighbourhood residents but must be open for other stakeholder groups that have a decision-making role even though they are not residents of the particular target neighbourhood. In this case, they refer these groups to community-building initiatives, which can be in the form of Civil Society Organisation (CSO), grassroots community, NGOs, and other types of locally led organisations that are non-profit and non-governmental based. Their involvement is relevant and important because this type of actor is usually involved to help local community and plays a central role in the fight against large-scale development which tends to harm the community (see further explanation in Section 5.2).

1.2. Preliminary taxonomical discussion of place-making

To deepen the understanding of place-making, it is necessary to highlight that specific (social) production processes make places. The concept of place-making is underpinned by the difference between “space” and “place.” While “space” refers to the functional “physical space,” “place” forms a concept of “space” in a relational sense as the location of social practices of different stakeholders (Healey Citation2001). Spaces become places because they are recognized by the people who live and do activities there (Franz et al., Citation2008). It is important to know that different stakeholders have different “conceptions of place” (Healey Citation2001). In this sense, one specific place can be perceived and treated differently by each stakeholder group. Differences in socio-economic and cultural backgrounds and access to power, knowledge, and capital should be taken into consideration when integrating different interests. Otherwise, all these differences can generate conflicts when producing the image of one place. For instance, in their study, Franz et al. (Citation2008) found conflicts between old-established inhabitants and Muslim migrants in the creation process of new mosques in Cologne. Conflicting interests also arose between some groups of stakeholders in the reuse of brownfields in the Ruhr. Therefore, classifying the definition of place-making based on different stakeholder groups and cultural contexts is essential.

Habibah et al. (Citation2013) defined place-making as making sense of a place in the views of stakeholders’ vision, strategies and practices. For urban designers and governments, place-making is often seen as the physical change of a place as an end-product of a project. The beautification of public spaces with iconic architecture, monumental artworks, sculptures and other artistic expressions, has been a critical factor in creating images of and identity for cities, villages and towns wanting to profile themselves. From the practitioners’ perspectives or self-funded initiatives, such as volunteers and non-profit organizations, place-making is a process of adding value and meaning to the public realm through community-based revitalization projects rooted in local values history, culture, and the natural environment. Lastly, place-making is usually a construct of places or experiences that the communities can display and offer from the local community perspectives. Place-making, as a component of participation in urban planning, should bring these different interests together. Franz et al. (Citation2008) stated that moderation is essential to arbitrate disagreement between different “conceptions of place” of different user groups (e.g., ethnic or social groups) and to promote a collective place-making that brings the different interests together.

To summarise what was explained earlier, place-making (as a process) is defined as an activity of integrating various actors’ viewpoints and functions in order to transform urban spaces; by not only viewing place as static spatial aspect and designing the physical form but also taking into consideration the social processes that construct places. In other words, place-making focuses a lot on the process itself rather than on the outcomes. “Design may follow; however, it should be only stem from the need of community; it is never a goal on its own” (Iwinska Citation2017, p. 76).

Differences between Conventional Place-making and Place-making

Table 1. Differences between Conventional Place-making and Place-making

Cilliers et al. (Citation2014a) provide differences between conventional place-making and place-making as a process (as can be seen in ). They argue that while conventional place-making is able to strengthen the local economy at the city level, their development scales and costs put pressure on the city budget and cause significant displacement of residents and local businesses. Therefore, it is important to rethink the conventional place-making concept and instead using the current place-making concept where it puts forward local communities’ agenda in the global city research agenda. “With this as the starting point, an elaboration of the concept of place-making should take into account its social dimensions, the actors involved, and its different scales” (Ho & Douglass, Citation2008, p. 206).

Place-making demands complexity to work in different contexts, with different stakeholders, and for different aims (Silberberg et al., Citation2013). We acknowledge the broad spectrum of place-making research and the numerous contributions that analyse them from different perspectives. However, studies which have emphasised that local residents can play a significant role in the success of place-making are still scattered in the literature. Important elements such as outcomes and factors that support or obstruct the process of place-making are often mentioned incidentally in publications without being systematically analysed across cases. We also aim to understand to what extent place-making can be implemented in various spatial scales, which we found that it is related with the type of approach that is taken (bottom-up, top-down, or collaborative). Therefore, there is a need to provide an overview and structure of this widespread literature and create a more coherent understanding of what the literature on place-making has to offer.

A systematic literature review of this study aims to bring better overview, comprehensive understanding of the concept of place-making and the factors influencing the outcomes of place-making. We used the following questions to guide and structure our systematic literature review: What are the definitions, characteristics, objectives, approaches, the influential factors, and the outcomes of place-making? To answer these questions, this paper systematically reviews place-making. This systematic review aims not only to provide a more evidence-based analysis regarding the place-making concept but also to make the current body of knowledge more transparent and comprehensive.

2. Methodology for conducting systematic literature review

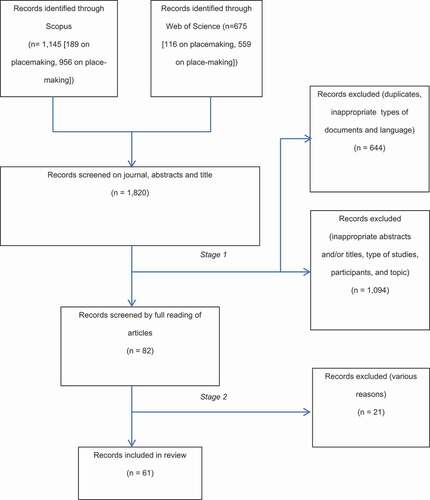

In order to manage and report on our systematic review, the author follows the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) approach as guidelines. This approach helps authors to ensure that their systematic reviews are transparent while assessing a wide array of literatures (Liberati et al., Citation2009). According to this approach, studies from our original searches were included in the systematic review if they met all the following inclusion criteria:

Type/field of studies

In this systematic review, we focus on place-making that is held in public spaces. In the literature, public spaces were defined broadly as “spaces that belong to the public domain that is open and accessible to all, regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, age or socioeconomic level” (E. J. Cilliers et al., Citation2014, p. 414). The reason why we limit the scope of this study to public spaces only is because the main aim of place-making (as a process) is to create, activate, and improve public spaces as a comfortable and accessible place for every member in every community. As explained by Brunnberg & Frigo (Citation2012, p. 113), “the practice of place-making is an inclusive and community-driven approach … it focuses on the entire process of creating meaningful public spaces in urban environments”. This aim will not be achieved (and will not be considered as ‘place-making’) if it is held in private spaces or other types of spaces that are exclusive to certain members or communities. Therefore, taking into consideration the importance of public space in the concept, sources should deal with the implementation of place-making that is influenced by local community’s activities during the creation of a public space, neighbourhood, city, or region into a more liveable place.

Topic

We selected sources between 1960 and August 2016. The year 1960 was chosen as some pioneers in place-making such as Jane Jacobs, William Whyte, published their works in this year. While August 2016 was selected as the last search was run on 11 August 2016.

Type of participants

It is important to bear in mind that we are keen to know what happens when local communities take part in the transformation of place. Local communities can refer to individuals, group, and representatives of residents in general. Therefore, the participants in the place-making process should be local communities (or their representatives) of the place where the movement is conducted.

Study design

Both theoretical and empirical studies are considered eligible. Many have argued that the place-making concept is still ambiguous, which requires more work to clear up the conceptual confusion about it. Therefore, instead of focusing only on the empirical evidences, this review also includes theoretical studies as an attempt to establish both theoretical and evidence-based understanding of place-making.

Language

Concerning the language, only English written sources were included, which is typical for systematic reviews, given the practical difficulties of translation and the replicability of the review (Voorberg et al, 2015).

Publication status

As quality appraisal standard in a systematic review study, one of the inclusion criterions to ensure the originality of the research is to select only the research papers that were peer-reviewed and published in a scholarly journal (Dupre 2018; Strydom et al. 2018). Therefore, this study only picked out peer-reviewed journal articles and used Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) as these two databases are frequently used for searching the literature on different scientific fields (Aghaei Chadegani et al. 2013). We were completely aware that this criterion presents some limitations as it excludes ‘grey’ literature. By using only databases that exclusively provide peer-reviewed journals such as WoS and Scopus, we limit some potential papers in grey literature which can be important to contribute in expanding our understanding of the place-making concept. Yet, it considerably helped to ensure that the studies we use as references are original works.

Year of publication

We selected sources between 1960 and August 2016. The year 1960 was chosen as some pioneers in place-making such as Jane Jacobs, William Whyte, published their works in this year. While August 2016 was selected as the last search was run on 11 August 2016.

As can be seen in , there were mainly two steps in selecting the articles to be included in this systematic review. The first level of screening involved the identification of 1,820 sources that were found through the keywords “placemaking” and “place-making” on both databases, Scopus and Web of Science. At this stage, we excluded 1,738 sources. The first 644 sources were removed in view of their irrelevancy to languages, types of documents, and also duplicates that were already reported in another included study. Afterward, we excluded other 1,094 sources based on other criteria, such as the type of studies, topic, and type of participants. We realise that the latter part of this stage contained large numbers of exclusion of the sources, the reason will be explained it in the following paragraphs.

Firstly, we found that most of the documents do not contain any words of “placemaking” or “place-making” in their title and/or abstract, while they appeared on the search engines as authors’ keywords. In these instances, some of the articles incidentally mentioned place-making in their publications without providing further discussion on the concept of place-making itself. In other words, these articles only used place-making as a word, not as a concept. Secondly, many articles were carried out in the field of studies that define place-making in a very different way with our definition, which relates to the activation of public space by local communities. The fields ranged from food (Sen, Citation2016, pp. 67–88), transportation (King, Citation2012, pp. 41–45), religion (Dwyer et al., Citation2015, pp. 477–490), sport (McManus, Citation2015), medical (Hörbst & Wolf, Citation2014, pp. 182–202), and tourism (Habibah et al., Citation2013, pp. 84–95). Thirdly, some other articles explain place-making in private spaces (such as offices, apartments, universities, religious spaces, and private housing), and therefore they focused on the other type of participants besides the local residents as was meant in our eligibility criteria (Arreola, Citation2012; Barr, Citation2015, 199–216; Harrop & Turpin, Citation2013). In the last stage of screening, we excluded more studies after reading the full-text that finally led to the inclusion of 61 studies. Some articles had been rejected because they approached place-making purely as a physical phenomenon, rather than a product of a social process. In these studies, local communities only act as the third party, which are only affected by the place-making efforts without really engaging in the process. For example, Fields et al. (Citation2015) discussed the critical components of place-making projects in recovering a district in New Orleans post-hurricane. However, it was fully organised by local government and did not involve local communities in the process. Therefore, we excluded this article in our review.

We also rejected studies that did not explain the concept of place-making. For example, in their studies (Dis)connected communities and sustainable place-making, Franklin and Marsden (Citation2015) include the terms “place-making” without further explaining about the definition, concept, process, and outcomes of “place-making”. Instead, their research is more concerned about the “sustainable communities” and “connection” concepts. In similar cases, we rejected the studies because of ‘less focus on place-making concept’, which was not always clear from abstract and thus required reading the full paper. We take another example from Mollerup et al. (Citation2015) who explained about street screenings in Egypt as an interactive engagement between local organisations as organizers and residential neighbourhood as participants. Nevertheless, instead of explaining the social process behind organizing the street screenings, this article pays more attention to the influence of images that appeared on the screening projects to participants’ perception on the political issues in the nation.

3. Types of approaches of place-making

In this systematic review, the data analysis consists of several steps. First, the analysis focused on the type of approaches of place-making. As shown in , these approaches differ in their degree of local community involvement during the place-making process, which are bottom-up, top-down, and collaborative approaches. We categorized each paper into these approaches through the following criteria:

Place-making procedures are managed through a bottom-up approach if local communities play key roles during their process (Douglas, Citation2016; Houghton et al., Citation2015; Lazarević et al., Citation2016; Piribeck & Pottenger, Citation2014). In other words, place-making is done by community groups who attempt to change and improve their places without (or very little) involvement of other stakeholders.

The second approach, top-down, is where place-making practices are implemented for new development in a larger scale and with a significant level of investment from government and private sectors who often play as the main (if not only) decision-makers (Chan, Citation2011a,; Darchen, Citation2013a,; Røe, Citation2014b; Teernstra & Pinkster, Citation2016b).

Place-making through a collaborative approach is indicated by the involvement of diverse stakeholders, including communities and experts, at varying stages of the process from inception, consultation and implementation, to evaluation (Cohen et al. Citation2018). However, we are aware that in every collaborative-based case, the roles of stakeholders cannot always be equal. In some cases, we found that collaborative approaches tend to be community-based, while in other cases they are more expert-based.

Table 2. Approaches of Place-making

As shown in , most of the cases are found to use the bottom-up approach. This is indeed an expected result as this study has focused on place-making where local communities are involved in the process. We found that place-making activities under this approach are mainly informal, tactical, and often using temporary, small, and low-technology interventions, such as artworks (Andres Citation2013; Balassiano & Maldonado Citation2015; Cohen et al. Citation2018) and cultural festivals (Kern Citation2016; Rota & Salone, Citation2014). Other authors also demonstrate that place-making is done through collective “mundane” activities of ordinary residents in their neighbourhoods. In the literature where the characteristic was found, scholars drew upon “everyday life” to explain place-making (Douglas, Citation2016; Elwood et al., Citation2015; John Friedmann, Citation2010; Lombard, Citation2014). Everyday life was defined as a process where places are claimed and shaped through everyday social practices. For instance, Elwood et al. (Citation2015) provide an interesting case in two Seattle neighbourhoods. Place-making is used by middle-class residents to teach poorer groups who live in the same neighbourhood. Together they create their neighbourhood into a place they envision through various collective efforts, such as community clean-ups and self-improvement activities (e.g., sewing and English class).

What stands out in the table is that despite place-making is often perceived as a collaborative process, only a few empirical studies showed that place-making could be implemented through the involvement and work of multiple stakeholders. A study by Andres (Citation2013) provides a clear explanation of why collaborative place-making is still a challenge. As quoted, “Tensions and conflicts appear as power shifts from temporary place-shaping users to formal place-making decision-makers. This process challenges the distribution of powers between various stakeholders” (p. 5). The finding of this study further shows that the collaborative process has not been clear-cut. While the power distribution between the city council and local community can be done quickly; the nature, components and the overall strategy of redevelopment take time. It took at least 10 years where the municipality finally transferred all powers to the local community.

Although there are only a few authors who mentioned about collaborative approaches in their studies, they have shown positive outcomes in place-making that are rarely found in a bottom-up and top-down approach. The collaborative approach shows how they successfully strike a balance between tangible and intangible aspects of places. For instance, Lazarevic et al. (Lazarević et al., Citation2016) report that synergy and joint stakeholders in the redevelopment process of cultural districts could lead to the “balanced outcomes” of all aspects. This is evident that while place-making increases economic opportunity for the locals through the creation of the business centre and tourist attraction in the districts, enhances the health and wellbeing of the community through the creation of green spaces and public spaces, place-making also strengthens local culture and educates people by applying a creative mix of cultural, environmental and historic resources linked with social and economic aspects. Along the same line, Knight (Citation2010) shows that place-making could rebuild confidence in places and make a sustainable community-based tourism destination while stimulating economic growth. The key success lies in the vision and leadership of local champions within the community. However, place-making would not achieve its huge success if not supported and assisted by the local government that commits to working together with the community and NGOs who are involved in the development, promotion, and marketing of the projects. A study by Woronkowicz (Citation2016) also found that place-making through open-air performance in neighbourhoods can increase the neighbourhoods’ growth with less gentrifying effects. The implementation of the project is created through a partnership with the local municipality and then operated by a separate charitable organisation, which provides the venue with seed capital and operating support. In their study about the development of creative clusters, Drinkwater and Platt (Citation2016) demonstrate that the success of developing and sustaining creative clusters in the two cases is related to place-making processes. It is said to add activity and vitality of the public realm in the areas as well as build its positive image. The critical component of the process is the successful integration of public policy with policy-led initiatives, business interests, and organic movements by the local community.

In this systematic review, we distinguish the local community into two categories, which are local residents and local organisation. This division is based on their organisational structure. The former category refers to an informal group of community which is not established by any formal authority but arises from the personal and social relations of the people. Residents can act as individuals or members of neighbourhood organisations who do place-making collectively. While the latter category refers to any social movement, institute, or organisation which is established by formal authority but not part of the government and private sectors. This group is usually committed to working for residents’ needs, such as volunteer/non-profit organisations, non-governmental organisations, a group of local artists, and local entrepreneurs (Douglas, Citation2016; Piribeck & Pottenger, Citation2014; Thomas et al., Citation2015; Stevens & Ambler, Citation2010a). Based on these types of the local community and our investigation towards a bottom-up approach, we also classified two other categories of place-making according to the level of local community involvement during the process.

shows that the place-making initiative was more often found within the local organisation rather than residents. Many previous studies showed the importance of local organisation in place-making since the practice was first initiated and dominated by this organisation. For instance, Bendt et al. (Citation2013) explains the role of community gardens in improving public green spaces of degraded neighbourhoods in Berlin through gardening projects while local residents were passive actors who merely participate in the implementation of place-making. Piribeck and Pottenger (Citation2014) demonstrate the importance of a local art organisation that successfully did place-making for revitalizing a neighbourhood and reinforcing its identity as well as connecting various stakeholders, including the local community, government, and private sectors. While Foo et al. (Citation2013) found CSO as the main network resource and support beyond the local community’s boundaries in the case of a Boston’s vacant lot conversion into community park.

Table 3. Local Community in Place-making

Nonetheless, several other studies showed how residents played active roles during the whole place-making process, from an initiator, planner to the organizer (e.g., Bendt et al., Citation2013; Brunnberg & Frigo, Citation2012; Sandoval et al., Citation2012). Semenza (Citation2003) gives an example of Sunnyside, a neighbourhood in Portland, where residents initiate place-making by transforming a busy street intersection into a plaza as a community gathering place. It showed a strong, independent community who had planned the project since the beginning until the implementation, whereas the other stakeholders were only complementary. Knight (Citation2010) states that many of place-making initiatives in Newfoundland were started by residents instead of professional planners. The self-reliant community who was able to utilize their available resources was said to be the main factor that contributes to the success of place-making.

4. Factors influencing place-making

In this section, we focus on addressing the third sub-question: What are the factors that influence place-making? We identified six main categories as influential factors of place-making, which are institutional context: local resident-related factors (35%), local organisation-related factors (15%), governmental-related factors (12%); physical and spatial contexts (12%); and other contextual factors (15%) such as media exposure and political and economic factors including a weak property market, unstable financial condition of the project, and strong disagreements relating to land use modification.

Table 4. Influential Factors

Next, we discuss all categories of influential factors that we found in our systematic literature review in more detail. The first three factors address the various ways (the involved) actors in place-making think and act.

4.1. Residents-related factors

It can be seen from the data in that there are three influential factors from the residents. All these factors can be considered as “two sides of the same coin,” where they can be either “supporting” or “opposing” factors. The first factor is the capacity of residents. Some authors referred to capacity as a particular tactic that is used by locals in improving their places without being driven by government or other stakeholders. This also includes using the individual and communal skills, talents, resources, and abilities during place-making (Andres, Citation2013; Knight, Citation2010; Warren, Citation2014; Zelinka & Harden, Citation2005). There were also some other authors who defined the local capacity as self-organisation—which can be in the form of identifying public needs, organising place-making by their own, and drawing benefit from place-making (Bendt et al., Citation2013; De Sartre et al., Citation2012). It is also believed that this kind of capacity is built through the various life histories of the dwellers living in the same area, including the struggles, the failures, and also the interactions among the dwellers (Lombard, Citation2014). Regardless of how the capacity is defined and measured, it is apparent from the literature that the higher the capacity of residents, the bigger the chances of place-making to deliver positive impacts (E. J. Cilliers et al., Citation2014; De Carteret Citation2008; Lepofsky & Fraser, Citation2003).

Table 5. Local Resident Factors

The second factor is residents’ network which relates to their enthusiasm and openness in collaborating with other groups of community and stakeholder (Andres Citation2013; Bendt et al., Citation2013; Foo et al., Citation2015; Keating, Citation2012; Rota & Salone, Citation2014). This factor addresses the importance of local networks in place-making, particularly since many cases in the literature identify strong network as an enabling factor. An example is evident in a study by Rios and Watkins (Citation2015) who found that the success of place-making depended on the collective ties among particular ethnic groups. Through strong networks that were built across regional boundaries and state lines, these groups were capable to arrange cultural and political events by themselves and transform a former vacant place into lively farmer’s markets.

While the last factor is related to demographic factors, including the social, cultural, and economic characteristics of residents (Main & Sandoval, Citation2014; Rios & Watkins, Citation2015). Referring to early research works, the socio-economic status in this study comprises gender, age, marital status, occupation, education, and income. The difference in the socio-economic characteristic could influence how place-making is implemented as well as how it impacts the different groups of residents. It is because in some cases, place-making is more attractive for particular groups. For instance, Benson and Jackson’s (Citation2013) study in a London neighbourhood where participation in everyday activities often depended on the longevity of residence and age. In their case, it is the older and retired group of residents who are involved more often than the younger group. In contrast, Peng (Citation2013a) found that youth, such as college students, joined the community organisations and helped in organizing various events and annual cultural activity as a part of an anti-dam campaign in the area. They were the ones who brought up more diverse social issues in the activities and also oriented the transformation of the area.

4.2. Local organisation-related factors

From the local organisation side, three factors are mentioned to influence place-making: capacity, openness, and network.

As can be seen in , the first factor is related to the capacity of local organisation. During our analysis, we further found various indicators of this capacity that mainly refer to social and practical capacities (Goldstein, Citation2016; De Sartre et al., Citation2012; Stevens & Ambler, Citation2010a). Social capacity refers to the organisation’s potential for providing social learning in a given place-making activity, such as reaching out to different social groups or leading place-making participants to particular social outcomes. For instance, Keating (Citation2012) demonstrates the role of local artists as one of the essential factors in assisting residents during a place-making initiation to engage other people to appreciate and build a sense of place with the landscape surrounding them. In the same vein, Friedmann (Citation2012) also states that the number and variety of local organisations that depend primarily on local volunteering trigger an additional place attachment for the residents.

Table 6. Local Organisation Factors

Other authors also mention the significance of the practical capacity of local organisation. This refers to how the organisation can manage place-making agendas and achieve the goal of place-making activities through their technical knowledge such as understanding tools for activities and technology use (Alexander & Hamilton, Citation2015; Bendt et al., Citation2013; E. J. Cilliers et al., Citation2014; Keating, Citation2012; Thomas et al., Citation2015). For instance, Douglas (Citation2016) investigates 69 local organisations in the USA who have conducted “do-it-yourself” projects and found the common characteristic that influences their place-making practices. These local organisations have technical knowledge which in this case, refers to their understanding of urban policy and planning practice. Stevens and Ambler (Citation2010a) found that one of the key success factors in place-making was the capacity of local organisation who had the technical and organizational capacities and autonomy to carry it out.

The other factor is the level of openness and awareness of local organisation to involve residents in the place-making process, which can be represented in their open attitude towards residents (Bendt et al., Citation2013; De Sartre et al., Citation2012). This openness includes acknowledging local needs, consulting projects with residents, involving them in decision-making process, handing over responsibility to them (Bendt et al., Citation2013; E. J. Cilliers et al., Citation2014; Darchen; Franz et al., Citation2008; Keating, Citation2012; Pollock & Paddison, Citation2014; Teernstra & Pinkster Citation2016b). The level of openness of local organisation determines to what extent place-making is favourable for residents. For instance, Alexander and Hamilton (Citation2015) found that the most critical part of the place-making process lies in the local organisation who recognised the importance of community participation and provided the opportunities to engage residents in place-making. Together they did physical improvements in railway stations, which not only empowered the residents along the process but also created a sense of place and community.

The third factor is the affiliation between local organisations and other primary stakeholders, such as public and private sectors. Other authors (e.g., Foo et al., Citation2013; Goldstein, Citation2016; Lim & Padawangi, Citation2008) also relate to this relationship with the ability of local organisations in negotiating with these actors during place-making. This factor is important to achieve a stable and viable place-making. Unless they are large and well-established organisations, most cases show that local organisations need to collaborate with authorities to support their place-making projects. This support is particularly important in regard to the finance, networks, and other aspects that local organisations cannot handle alone. For instance, Peng (Citation2013a) shows that experts and researchers play important roles in bridging the gap between government and civil society organisation during the process of making policy in a place-making project so that it can be more accountable to local communities. Lazarevic et al. (Lazarević et al., Citation2016) also point out that despite the success of place-making by local communities in the redevelopment of a vacant area to ensure a long-term regeneration process, they should be accompanied by a more strategic plan compiled by a range of stakeholders. In this case, specifically, one of the barriers of place-making is related to property-ownership issues by the private business which remains unsolved due to difficult and lengthy legal proceedings. It is important to note that this affiliation between the local organisations and other stakeholders should be in favour of the local community. Lim and Padawangi (Citation2008) demonstrate the case where certain local organisations collaborate with government and private sector in the creation of public spaces. However, their access to policies and decision-making in the project is done without the involvement of residents who live and work around the area. As a result, place-making leads to marginalisation of particular residents whose identities do not match what state and local organisations intend to promote.

4.3. Governmental factors

When we focused on the influential factors that come from governments, we see three aspects emerge, as shown in .

Table 7. Government factors

The most mentioned factor is the level of openness and awareness towards community participation (Andres Citation2013; Barnes et al., Citation2006; Knight, Citation2010; Larson & Guenther, Citation2012; Peng 2013; Roe Citation2014b; De Sartre et al., Citation2012). This may refer to the presence or absence of support from governments in acknowledging local needs (Chan Citation2011a; Hunter, Citation2012; John Friedmann, Citation2010), providing sessions to communicate with residents and deliver their aspirations in place-making projects which are initiated through top-down approach (Bendt et al., Citation2013; Darchen Citation2013; Franz et al., Citation2008; Keating, Citation2012), or integrating place-making project by communities with public sector agendas (Barnes et al., Citation2006; Dukanovic & Zivkovic, Citation2015; Semenza, Citation2003).

Most cases in the literature mention that open-mindedness towards community participation by public officials can influence what kinds of impact occur from place-making (Darchen 2013; Knight, Citation2010; Lim & Padawangi, Citation2008; Teernstra & Pinkster 2016). For example, Semenza (Citation2003) highlights that one of the enabling factors in the success of place-making project by local community is that the city council agreed to include the project as part of the city’s community enhancement project and provide materials to support the project. In contrast, lack of openness and acknowledgement to involve the local community in place-making often lead to adverse impacts on the community. This is evident in a comparative study by Chan (Citation2011a) which shows sharp contrasts between place-making impacts in the case where government is involved and where community is excluded during the process of running place-making to create local specialities. The residents in the first case are drawn closer together in their joint participation in communal activities to promote local cultures and place-making can promote local speciality and successfully build local identity. While in the latter case the impact is very minimal and tends to be driven by individual profit motive instead, which weakens communal relations as a result of the quest for individual gain.

Many of the authors (Cilliers & Timmermans, Citation2014a; Ho & Douglass, Citation2008; Larson & Guenther, Citation2012; Pierce et al., Citation2011; Stevens & Ambler, Citation2010a) also highlight the importance of government networks in place-making. Franz et al. (Citation2008) pointed out the role of government in place-making as a process, which has to cooperate with other stakeholders and use its power to push the local development. In this way, government can play key role in the provision of funding, trainings, infrastructure, materials, or other resources to help community projects (E. J. Cilliers et al., Citation2014; Semenza, Citation2003), encouragement to scale up place-making projects from a local level to city and regional level (Andres Citation2013; Franz et al., Citation2008), or support decision-making over land-use or land-tenure in favour of local communities (Andres Citation2013; De Sartre et al., Citation2012).

Institutional collaboration can also be done to support place-making by and for local communities (Bendt et al., Citation2013; Healey, Citation1998; Roe, 2014). A common form of support includes Public–Private Partnerships (Andres 2013; Drinkwater Citation2016; Foo et al., Citation2013) and collaboration in policy-making through the involvement of multiple stakeholders in the process of policy development (Healey, Citation1998). Larson and Guenther (Citation2012) demonstrate an example where collaboration between the government and private sectors for place-making projects initiated by a local community not only supported local identity, building social capital, promoting community building, but also ensured the viability of the project through securing funding from multiple sources, including business improvement grants. In some cases, however, collaboration between the government and other stakeholders does not always come as a support for the local community (Chan 2011; Darchen 2013; Roe 2014). The tendency of the government to cooperate with certain parties can be an obstacle to involve the community in the place-making process. For instance, Darchen (2013) found that over-reliance on the private funding sources leads to a type of place-making that is strongly shaped by business interests and puts aside the community needs. Further explanation on this topic will be provided in the following paragraphs.

The third factor is the type of governance. Much of the literature emphasises governance as horizontal and cross-sectional collaborations (Jackson & Kent, Citation2016; John Friedmann, Citation2010; Larson & Guenther, Citation2012; De Sartre et al., Citation2012). Healey (Citation1998, p. 1537) describes governance in the context of collaborative place-making: “It complements or replaces vertical and sectional linkages to the central state leading to all kinds of efforts in place-making and in building the institutions for place-making at region, city, and local settlement levels”. Some cases emphasise the importance to address cross-departmental objectives within the same level of governance. This is evident in a case study by Stevens and Ambler (Citation2010a) which reports that as a result of coordination works among the municipality’s 12 different departments, an annual place-making project held by Paris government has become part of the city’s cultural heritage and contributed to the collective memory of the citizens. Similarly, Larson and Guenther (Citation2012) found that interdepartmental collaboration within a municipality ensures the function and viability of place-making projects to run over the long term. In other cases, governance can also be a bridging tool for a state or regional government to help place-making at the local level and the other way around. For instance, Ho and Douglas (Ho & Douglass, Citation2008) reviews case studies where place-making can enhance local capacity mainly because of the state support. In this case, the type of governance where a regional government involves representatives from different cities of a wider metropolitan region is said to support place-making at the local level.

The importance of integrating local governance with a broader structural policy of municipal government is not limited to the collaboration between governmental actors. It is also important to collaborate with other stakeholders who implement place-making project at the local level. A study by Foo et al. (Citation2015) discusses how neighbourhood-based CSOs could act as formal partners of municipalities in providing public services at the neighbourhood level. This collaboration enhances the well-being and positive perceptions of residents towards their neighbourhood environment while integrating local interventions with city policy. A case study by Franz et al. (Citation2008) found that the realisation of place-making projects at the local level and the monitoring of this development can support the growth of overall strategies at the regional level. However, moderation by the project team is necessary to mediate local community and to arbitrate different “conceptions of place” of different user groups and to promote a collective place-making that brings the different interests together.

Governance also refers to the ways public authorities control over development. Studying governance in place-making provides insight on how well the government system is able to respond to the changing circumstances of a society while shaping the decision-making process that involves different objectives and interests of various actors (Razali and Ismail Citation2015). In this way, governance is often linked to development orientation (Barnes et al., Citation2006; Chan 2011; Darchen 2013; Ho & Douglass, Citation2008; Roe 2014; Teernstra & Pinkster, 2016) and power distribution (Andres 2012; Drinkwater & Platt Citation2016; Franz et al., Citation2008; Healey 1997; Hunter, Citation2012; Quayle et al., Citation1997; Roe, p. 2014).

Similar to the previous factors, the presence or absence of good governance leads to different types of outcomes. For instance, in her comparative study of the two modes of governance, Darchen (2013) found differences between state-sponsored, market-driven development and government-led, local-centred development. She concludes that the different dynamics among various actors lead to how likely collaborative approach can be implemented in place-making. In his case study of governance and entrepreneurial policies in place-making, Roe (2014) refers to this “dynamics” as power differences between stakeholders which can lead to conflicts and social division. In this case, the political purpose between the government’s (which aims to reshape and expand the city as a municipal capital) goes along with the private sector’s intention (to earn better returns on their investments).

4.4. Physical and spatial contexts

This factor describes physical and spatial aspects which can be either enablers or barriers in the place-making process. It encompasses four categories: geographical characteristic of the area, provision of social amenities and basic infrastructure, design of neighbourhood and the availability of and access to land. However, their influence on the success of place-making projects cannot be easily determined because the multiple institutional aspects along with other aspects often overcast underlying physical and spatial conditions ().

Table 8. Physical and Spatial factors

Geographical characteristic includes location, size, former use, and access to surrounding areas (Andres 2012; Bendt et al., Citation2013; Roe 2014; Drinkwater & Platt 2015; Franz et al., Citation2008; Woronkowicz 2015). The literature identified neighbourhoods that are far away from the city centre as disadvantaged. In this regard (spatial) distance and lack of accessibility and connectivity to surrounding areas act as barriers for place-making, particularly the one that needs external visitors such as neighbourhood festivals or community gardening projects (Andres 2012; Cilliers et al. 2015; Drinkwater and Platt 2015). For instance, Bendt et al. (Citation2013) show that those neighbourhoods that are located in the central-busy area and mix cultured have generated stable flow and eclectic group of participants in community gardening projects rather than those that are located in more secluded and homogeneous areas.

The second category describes the materiality of resources. Several authors (Foo et al., Citation2015; Stevens & Ambler Citation2010a; Woronkowicz 2015; Zelinka & Harden, Citation2005) emphasise that for a neighbourhood to experience the benefits from place-making, it is important to ensure that residents’ basic needs are met. This includes a reliable supply of clean water, sanitation, shelter, electricity, roads, and other basic infrastructure. The lack of access to these facilities is unlikely to make place-making successful or last longer.

The availability of and access to land, which in this case refer to the legal status of the land, also affects place-making projects. Most of the literature discusses this factor as a barrier because of the lack of land availability or uncertainties of land tenure system and legislation in the places where place-making is implemented (Andres 2012; Foo et al., Citation2015; De Sartre et al., Citation2012). For instance, Foo et al. (Citation2015) found that lack of secure access to land and property created a barrier for place-making participants to care and maintain their neighbourhood because they do not feel like they own the place. In other words, “absentee land ownership fosters perceptions of neglect” (p. 143).

The last category is the design of places, which refers to usable and functional spaces provided in a neighbourhood or city (Cilliers et al. 2015; Ho & Douglass, Citation2008; Semenza, Citation2003). Well-designed places are said to have higher chances of getting advantages from place-making. Cilliers et al. (2015) argued that the creation of flexible spaces that suit various users is important to enhance the vitality and liveliness of a place. Semenza (Citation2003) states that neighbourhoods that have not applied mixed land use tend to be isolated. In a similar vein, Ho and Douglas (Ho & Douglass, Citation2008) found that place-making in mixed-use neighbourhoods is more likely to strengthen social connection rather than single-use neighbourhoods. As mixed-use neighbourhoods have a range of amenities close by, they can generate a more walkable lifestyle among its residents. This, in turn, results in neighbours being more likely to know each other, being more involved socially, and having higher levels of social trust and political participation.

4.5. Other contextual factors

In addition to the aforementioned factors, other contextual factors—such as political climate and socio-economic situation, can impact how the influential factors become apparent in the real-life cases of place-making. It is also important to take start conditions into consideration. In cases where the community already tend to have high level of place attachment and social capital even before place-making takes part, such as in a neighbourhood or settlement with relatively dense and rich relations, can for an important part influence the willingness of residents and the possibilities for place-making to take place. In this way, there is already fertile soil for place-making and its outcomes. Regarding to this condition, some reflection on the outcome place identity and attachment is also needed. Even though place attachment is treated as a potential outcome, one can also approach it as an influential factor. Residents with a high feeling of place identity and attachment are more likely to be positively motivated to get involved in place-making processes. The process of place-making in turn can then further strengthen their place identity as they interact with other community members. This variable has to be treated with care in the future research in order to avoid confusion about causal relationships between influential factors and outcomes of place-making.

5. Outcomes of place-making

In the literature, we found several outcomes of place-making, which then divided within four main categories: local empowerment, social connection and capital, place attachment and identity, and quality of life.

As can be seen in , most of the social outcomes of place-making as a process are related to the increasing capacity of the local community (Douglas, Citation2016; Goldstein, Citation2016; Main & Sandoval, Citation2014). Some authors also describe this outcome as technical exchange and organisational knowledge between stakeholders (Rios & Watkins, Citation2015) or broadened local community’s perspectives about their city and other people (Houghton et al., Citation2015). One specific example by Dukanovic and Zivkovic (Citation2015) underlines the importance of place-making as vehicles for increasing community capacity. They found that the project offered a learning experience to the participants through the opportunity to become tutors and project managers of the next event. As a result, the participants were able to gain knowledge and skills in interdisciplinary and collaborative work. This study concludes that enthusiasm for improvement of city spaces through place-making was rooted in a synergy of the citizen, expert and public sector.

Table 9. Social Outcomes

The second most mentioned outcomes are related to the creation and strengthening of social ties (Dukanovic & Zivkovic, Citation2015; Ho & Douglass, Citation2008; Lazarević et al., Citation2016; Peng 2013; Piribeck & Pottenger, Citation2014; Rota & Salone, Citation2014; Warren, Citation2014). This outcome particularly refers to the increase in the interaction, dialogue, cooperation, and inclusiveness among different group of local residents. Sandoval and Maldonado (Sandoval et al., Citation2012) also found that an annual cultural event in a Latino neighbourhood offered an opportunity for people of different cultures to interact and break down cultural barriers between the Latino and non-Latino residents as the festival attracted the participation of both groups of residents. It was also said that place-making has the power to forge new social network (Cohen et al. 2018). For instance, Piribeck and Pottenger (Citation2014) report that place-making created new friendship relations between local communities who may never know each other if they were not involved in the project.

The other outcome of place-making, local identity and pride is related to the specific social, cultural, and physical components of place that can contribute to strengthening the identity of the place and its inhabitants (Drinkwater & Platt, Citation2016; Larson & Guenther, Citation2012; Rota & Salone, Citation2014). In this way, place-making is verified to creating, strengthening, and regenerating community identity (Andres 2012; Chan 2011; Peng 2013) adding distinctive characteristic to the area (Rota & Salone, Citation2014), and fostering embedded knowledge within the community through social and cultural elements of places (E. J. Cilliers et al., Citation2014; De Carteret 2007; Roe 2014). A good example can be seen from Rota and Salone’s (Rota & Salone, Citation2014) study which demonstrates that art festival successfully reinforces social ties and renovates local identity of both places and its people. In this way, the event becomes a stimulating tool for representing the neighbourhood and its inhabitants.

In reviewing the literature, many studies also mentioned the importance place-making in improving the well-being of residents (e.g., Lazarević et al., Citation2016; Teernstra & Pinkster 2016). An example given by Sandoval and Maldonado (Sandoval et al., Citation2012) reported some changes related to their research respondents who felt isolated before frequently participate in place-making. Throughout the process, they felt safer and got better in both mental and physical ways. It was not only because of their engagement in the activity itself but also because the place-making activity became a place where the participants can connect with one another and get help for basic material needs, such as food and clothing.

Various authors also link place-making’s ability to enhance positive perceptions of the local community towards their neighbourhood (Cilliers et al. Citation2015b; Foo et al., Citation2015; Lim & Padawangi, Citation2008; Stevens & Ambler Citation2010a) and build positive image and confidence in certain places (Knight, Citation2010; Lombard, Citation2014; Semenza, Citation2003). All of these outcomes can also directly or indirectly strengthen relationships between people and place. One of the common forms of this relationship is place attachment, which refers to the process where a place has the capacity to affect the emotional response of people (Benson & Jackson 2012; Chan 2011; John Friedmann, Citation2010; Marshall & Bishop 2015). For instance, Alexander and Hamilton (Citation2015) found that place-making created an aesthetically pleasing environment and made a station building as a useful space for particular activities. Through this transformation, people started to see the station more as a community asset than a transport hub. This condition increased the sense of ownership, pride, the responsibility of the community, and also developed a sense of place.

Other than these outcomes, there were a few other authors who also present that place-making can improve quality of place by adding various values—social, aesthetical, recreational and economic—to public spaces (Brunnberg & Frigo, Citation2012; Darchen 2013; Dukanovic & Zivkovic, Citation2015; Knight, Citation2010; Rota & Salone, Citation2014). For instance, Foo et al. (Citation2013) report that place-making improves the aesthetical and ecological values of a vacant lot into public space in a neighbourhood. Cilliers et al. (2015) also found that place-making through small interventions, such as making green roofs, walking routes, and other urban furniture, can transform temporary spaces into permanent places. Place-making is also said to vitalise the place environment, which leads to better well-being in addition to the vibrant social environment (Sandoval et al., Citation2012) and increases safety and security (Lazarević et al., Citation2016; Teernstra & Pinkster 2016).

Nonetheless, some cases demonstrate that place-making without community-orientation could only increase the physical and economic values of spaces but adversely impact the community. This highlights a critical stance towards place-making that it may lead to unfavourable results or side-effects. However, it is important to note that these negative outcomes are particularly found in place-making through a top-down approach with less community participation and focusing more on physical development (e.g., Andres, Citation2013; Barnes et al., Citation2006; Kern, Citation2016; Lepofsky & Fraser, Citation2003; Teernstra & Pinkster 2016).

The most mentioned adverse outcome of place-making is social division between the local community and other groups of communities and stakeholders. Some articles mention this type of social division differently as displacement of lower-income or weak group of residents (Teernstra & Pinkster, Citation2016b), exclusion (Barnes et al., Citation2006), alienation (Lepofsky & Fraser, Citation2003), and gentrification (Andres, Citation2013; John Friedmann, Citation2010; Kern, Citation2016). Despite using different terms, they all primarily refer to the inability of residents to participate in the new changes of particular places after place-making is conducted in those places/areas. This impact is often happened in slum areas or neighbourhoods that have become upgraded and transformed into a desirable residential location, which eventually leads to drive up the land and rent prices. Place-making then leads to these negative impacts because of the residential shifts—which usually happened between long-standing and new-comer residents (Andres 2012; Kern 2015; Roe 2014), differences on socio-economic status and cultural identities (Barnes et al., Citation2006; Teernstra & Pinkster 2016), differences on power and perspective between local community and other stakeholders (Ho & Douglass, Citation2008; Lim & Padawangi, Citation2008).

5.1. Factor–outcome relationships

Based on the literature, we found that none of the authors aimed at the investigation between influential factors and specific outcomes of place-making. Instead, most studies were keen to only identify influential factors, ranging from stakeholders (Bendt et al., Citation2013; Warren, Citation2014) to particular factors, such as storytelling (Cilliers et al. 2015), experiential academic education (Dukanovic & Zivkovic, Citation2015), cultural events (Rota & Salone, Citation2014), and urban technology (Houghton et al., Citation2015). Other authors also aimed their studies at the identification of particular influential factors with specific outcomes (Foo et al., Citation2013; Kern, Citation2016; Main & Sandoval, Citation2014; Woronkowicz, Citation2016). For instance, Hunter (Citation2012) investigated the impact of local leadership and strategic management within the local organization in shaping the residents’ quality of life and transforming local places. In several previous studies on place-making, different variables have been found associating with different outcomes. A study by Marshall and Bishop (2015) on the correlation between place-making and place attachment showed that there is a direct link between strong place attachment at both individual and community level with successful place-making process. While Woronkowicz (Citation2016) found a positive association between the existence of a particular type of place-making, which is an open-air performance venue, with a series of outcome variables measuring neighbourhood growth.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Place-making is a multifaceted concept that has been widely researched since the mid-1960s. It was previously focused on the physical change of a place as an end-product of a project by urban designers and has been shifted to be the process of transforming physical and social elements of places by numerous actors outside the planning profession. The observed shift is not only in the orientation (from product to process-oriented) but also regarding decision-making. The viewpoints of various stakeholders became important and subsequently guided the decisions associated with the making of places. For the scope of this paper, the review only focused on the shifted place-making concept.

Before we turn to conclude our systematic literature review, we first discuss some limitations of our approach. The first limitation is regarding the methodology. As we only selected peer-reviewed journal articles and did not include other materials (such as conference papers and books), we might have missed something useful for a better understanding of the concept. Future studies on place-making with broader publications, including books on the place-making subject, conference proceedings and exhibition catalogues of place-making, are needed to provide a more comprehensive study. The second limitation of the study is that we did not consider place-making as a practice and a category when it appears under different names during the selection process of articles for this systematic review. In comparison, it is most likely that in some topics, such as urban design, community improvement or regeneration projects, place-making is discussed differently. Therefore, we recommend future studies to include a wider base of articles or data that could bring more diverse and specific aspects of place-making related topics into their review and analysis. It would be worthwhile, however, to focus on the small pool of reliable resources that we have as previous systematic review studies (e.g., Strydom et al. 2018; Wesener et al., Citation2020) believed that even with these limitations we can draw some meaningful conclusions.

First, our study reveals that regardless of many theories that have emphasised the importance of collaborative approaches for place-making, most empirical cases found in the literature are purely bottom-up. This finding strengthens the idea that place-making can be achieved without a formal plan and the success of place-making does not solely depend on the influence of elite policymakers. It is evident in the various present cases that illustrate multiple ways in which place-making is made possible through factors that spring from within local communities. On one hand, it can be considered as an asset of place-making compared to traditional planning. Some characteristics of place-making as a process, which are temporary, inexpensive, spontaneous, and small, indicate how place-making is more accessible to the local community. It creates more projects that are based on the local needs and increases the likelihood for community empowerment. Although, at the same time, this outcome raises a critical question for scholars and practitioners in planning disciplines regarding the gap between theory and practice. From the former perspective, place-making is collaborative in nature and considered as a bridging tool between the top-down and bottom-up approaches. Yet, it seems that collaborative place-making is still quite a challenge to be implemented. An important underlying question is then to understand how to bridge bottom-up (place-making) initiatives on a small scale to the top-down initiatives on a larger scale. Other than to provide insights of how these initiatives emerged and evolved, one could conduct this research to address the infamous weakness of place-making on a small scale, in which it is difficult to place it in the bigger scale projects and incorporated with governmental policy and projects.

In the next research question, which is addressing the influencing factor of place-making, we distinguish four main factors that become apparent from this systematic review: residents-related, local organisation-related, governmental-related, and physical-spatial factors. These factors can be barriers and enablers for place-making, depending on their presence or absence. It is useful to analyse place-making through different actors’ lens to understand how to support place-making based on their perspectives and roles. Based on this study’s results, it is evident that the factors identified in the literature may be experienced differently by communities, local organisations, and governments. The analysis findings showed that local capacity, openness to other stakeholders and socio-economic factors are the most relevant resident-related factors. Communities need to develop related skills and self-organisation as well as being open to collaborate with other actors. Socio-economic and cultural factors are also important to take into consideration because place-making is a phenomenon created by and for local communities. In many cases, the differences in these attributes could trigger conflict within and between communities.

From the local organisation-related aspect, three factors are necessary: capacity, openness to community participation and network with other primary stakeholders. While the local organisation-related factors are similar to resident-related factors, they refer to the different meanings. For instance, the local capacity in residents-related factors indicates that communities need to develop related skills and attributes to reclaim and transform spaces into meaningful places by themselves. On the other hand, capacity in local organisation-related factor refers to organisational capacity and their technical knowledge regarding place-making.

Some other significant differences also occurred between the local organisation and government. Factors in a government-related aspect comprise openness to community participation, network with other primary stakeholders and governance type. It can be seen that open-mindedness towards community participation in place-making by both local organisation and government has been considered as essential factors. However, although both of them have “openness towards community participation,” they may have distinctive approaches in the process of involving residents. For local organisations, this openness reflects the extent to which place-making is favourable for residents, which can be done by acknowledging local needs and handing over responsibility to them. If seen from the government perspective, this openness may refer to what approach government initiates a place-making project, whether through top-down or bottom-up.

This review also reveals that place-making could bring positive social impacts to local communities, especially on gaining local empowerment, enhancing social ties, reinforcing place identity, and increasing quality of life. Nonetheless, some cases demonstrate that place-making without considering local needs could only increase the physical and economic values of spaces but adversely impact the community. This highlights a critical stance towards place-making, that it may lead to adverse impacts. Our investigation on this topic also found that few studies explicitly deal with the relationship between influential factors and outcomes of place-making. In this way, we lack evidence which factors are decisive in reaching (specific) social outcomes of place-making. Therefore, more empirical research on testing particular factors and social impact hypotheses is needed to understand and substantiate the outcome of place-making.

The findings (see Section 5) also illustrate the vital and complex roles that communities, public sector, and civic groups play in creating place-making that are viable and beneficial for its place users. It is important, therefore, to consider the interplays between factors—where one factor may influence the other and needs to be considered in combination with the others, rather than being treated as unidimensional. Urban planning and design practitioners should take into consideration the lens of different actors and factors to support place-making. Revealing and discussing such features are, as argued in the introduction,necessary to mediate local community and to arbitrate different “conceptions of place” of different stakeholders. Lastly, by understanding those differences, it can be an important step to promote a collaborative place-making that brings the different interests together and makes cities liveable, not just as an end-product of material gains but also as a continuous process of community and civil society involvement in place-making.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Poeti Nazura Gulfira Akbar

Poeti Nazura Gulfira Akbar is a lecturer at Tourism Department, University of Indonesia. She completed her PhD in 2020 at Erasmus University Rotterdam. She has studied, worked, and involved in several projects in the fields of urban and tourism development for 10 years. Her research interests include urban and rural tourism planning and development, creative community, events and festivals, and place-making.

Jurian Edelenbos is a professor of interactive urban governance at Department of Public Administration, Erasmus University Rotterdam. He completed his PhD in 2000 at Delft University of Technology. He has developed expertise in the fields of governance, citizen participation & self-organization, boundary spanning, trust, network management, and democratic legitimacy. He conducts research in the following domains: urban management & planning, integrated water management & sustainable energy.

Notes

1. In this study urban places refer to the inner-city places; from urban villages, neighbourhoods,districts to public spaces, such as parks, squares, plazas, and other types of publicly owned landthat are open and accessible to all members of a given community (cited from Drinkwater 2015)

2. By “people”, place-making can be carried out by different agents as explained by Cresswell (2004, p. 5): “All over the world people are engaged in place-making activities. Homeowners redecorate, build additions, manicure the lawn. Neighbourhood organisations put pressure on people to tidy their yards; city governments legislate for new public buildings to express the spirit of particular places. Nations project themselves to the rest of the world through postage stamps, money, parliament buildings, national stadium, tourist brochures, etc”

3. The people–place relationships mainly referred to the impact of the physicalenvironment on the people behaviour

References

- Alexander, M., & Hamilton, K. (2015). A ‘placeful’ station? The community role in place making and improving hedonic value at local railway stations. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 82, 65–29. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84942315858&partnerID=40&md5=1ede47aaf3dc8c63b9372c12f9870e6f

- Andres, L. (2013). Differential spaces, power hierarchy and collaborative planning: a critique of the role of temporary uses in shaping and making places. Urban Studies, 50(4), 759–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012455719

- Arefi, M. (2014). Deconstructing Placemaking: Needs, Opportunities, and Assets. Routledge.

- Arreola, D. D. (2012). Placemaking and latino urbanism in a phoenix Mexican immigrant community. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 5(2–3), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2012.693749

- Balassiano, K., & Maldonado, M. M. (2015). Placemaking in rural new gateway communities. Community Development Journal, 50(4), 644–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsu064

- Barnes, K., Waitt, G., Gill, N., & Gibson, C. (2006). Community and nostalgia in urban revitalisation: a critique of urban village and creative class strategies as remedies for social ‘problems’. Australian Geographer, 37(3), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180600954773

- Barr, O. (2015). A jurisprudential tale of a road, an office, and a triangle. Law & Literature, 27(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/1535685X.2015.1034474

- Bendt, P., Barthel, S., & Colding, J. (2013). Civic greening and environmental learning in public-access community gardens in berlin. Landscape and Urban Planning, 109(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.10.003

- Benson, M., & Jackson, E. (2013). Place-making and place maintenance: performativity, place and belonging among the middle classes. Sociology, 47(4), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038512454350

- Brunnberg, L., & Frigo, A. (2012). Placemaking in the 21st-century city: introducing the funfair metaphor for mobile media in the future urban space. Digital Creativity, 23(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2012.709943

- Chadegani, A., Arezoo, H. S., Yunus, M. M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., & Ebrahim, N. A. (2013). A comparison between two main academic literature collections: web of science and scopus databases. Asian Social Science, 9(5), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n5p18

- Chan, S. C. (2011a). Cultural governance and place-making in Taiwan and China. The China Quarterly, 206, 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741011000312

- Cilliers, E. J., & Timmermans, W. (2014a). The importance of creative participatory planning in the public place-making process. Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design, 41(3), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1068/b39098

- Cilliers, E. J., Timmermans, W., Van den Goorbergh, F. and Slijkhuis, J. (2015b). Green Place-making in Practice: From Temporary Spaces to Permanent Places. Journal of Urban Design, 20(3), 349–366. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84930573954&partnerID=40&md5=54605f0606a7180f903cc5caee3812f7

- Cilliers, E. J., Timmermans, W., Van Den Goorbergh, F., & Slijkhuis, J. S. A. (2014). Designing public spaces through the lively planning integrative perspective. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 17(6), 1367–1380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-014-9610-1

- Cilliers, E. J., Timmermans, W., Van Den Goorbergh, F., & Slijkhuis, J. S. A. (2015a). The story behind the place: creating urban spaces that enhance quality of life. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 10(4), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9336-0

- Cohen, M., Maund, K., Gajendran, T., Lloyd, J. and Smith, C. (2018). Communities of Practice Collaborative Project: Valuing Creative Placemaking: Development of a Toolkit for Public and Private Stakeholders. Landcom