?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In favour of the Big Five Invertebrates form the basis for ecosystem functioning but are typically neglected in ecotourism activities. Entotourism is introduced to elevate awareness about the potential of invertebrates and their conservation activity through tourism. Improved awareness via tourism activity can potentially lead to improved conservation practices. Yet, do tourists accept entotourism as another product of ecotourism? This study aims to determine the perception of tourists on entotourism activity in Sabah. We are implementing a mixed-method to acquire information needed via questionnaire surveys and in-depth interviews. At the same time, we applied a random sampling technique to gain the respective respondents. Data analysis used a t-test to examine gender perception and presented via Spider-Web configuration. In comparison, we used content analysis via Leximancer for qualitative analysis. This study demonstrated that people have a slightly different perception of insects and awareness based on their gender. Results show that most participants responded positively to insect information, awareness and their interest in certain insects. Respondents also gave their support to entotourism, which provided them with some new knowledge about insects. The interview has also indicated a positive perception of invertebrate information as part of the entotourism concept included in ecotourism activity. In conclusion, tourists’ perception of entotourism activity unveils a significant potential for the inclusion of invertebrate into current and future ecotourism activity, especially in Sabah. Alternately, it can be applied as a preparatory step for better planning and execution of invertebrate’s conservation and entotourism activity.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Insects tourism is an emerging ecotourism industry, such as the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) watching tourism in Mexico. Insect-based tourism has enormous potential. It can bring substantial economic benefits, especially to the host country. However, for the past four decades, insect populations had declined by 45%. Insects serve as the food web base, eaten by everything from birds to small mammals to fish. If they decline refuse, everything else will as well. Therefore, it is crucial to reviving public awareness about the importance of having insects in the ecosystem through entomological ecotourism.

Nevertheless, one needs to understand the public’s perception and awareness of insects before introducing them as a nature tourism product. Therefore, this research provides some insights into public perception and their awareness about insects. This preliminary research will give a baseline understanding of entomological ecotourism as a tool for insect conservation.

1. Introduction

Invertebrates are generally known to be the dominant group in the animal kingdom. They have enormously outnumbered all other terrestrial animals and can be found almost anywhere (Triplehorn & Johnson, Citation2005). Importantly, every invertebrate species has its ecosystem importance and is extremely valuable to human welfare (Kumar & Asija, Citation2004). However, they are also suffering from species loss and extinction (Clausnitzer, 2009). Thus, its conservation effort should be considered (Straub et al., Citation2015). It brings the idea and opportunity to elicit invertebrate’s potential and conservation into ecotourism activity. Ecotourism emerged in the late 1980s due to the world’s acknowledgement of sustainable and global ecological practices (Diamantis, Citation2004). Many countries are home to many of the world’s rare and threatened species (Brooks et al., Citation2006), and many protected areas are overwhelmingly the dominant setting for ecotourism activity (Weaver, Citation2008). Malaysia geographically possesses approximately 15,000 floras and fauna biodiversity that boasts ecotourism products (Ahmad et al., Citation2014). Ecotourism sectors in Malaysia are mostly rainforest and island-oriented-based attractions. Sabah and Sarawak both have advantages with the most incredible natural attractions such as Orang Utan, Rafflesia flower, Mount Kinabalu, Sipadan Island and Mulu Cave System (Weaver, Citation2008). Sabah is explicitly renowned for national parks, sanctuaries and reserves such as Kinabalu Park, Danum Valley Conservation Area, Maliau Basin, Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary and Tabin Wildlife Reserve (Chong, Citation2004) for wildlife observing particularly of mammals and birds.

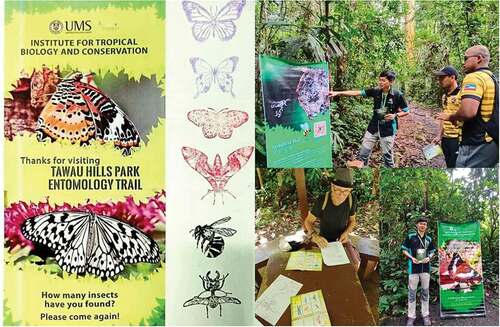

In the context of invertebrate abundance, in Malaysia, according to records from the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, there are more than 150,000 invertebrates identified. Most of them are insects (Nbsap, Citation2014), over 2000 insects’ species found in Sabah (Bruhl et al., Citation1998; Chung et al., Citation2000; Floren & Linsenmair, Citation1998). However, invertebrates are the most threatened living organisms on Earth due to climate change, deforestation and other human activity, especially in tropical area (Collins, Citation2012; Kim, Citation1993; New & New, Citation2009; Oberhauser & Guiney, Citation2009). It opens a massive opportunity for entotourism to elevate the invertebrate’s potential as an eco-tourists conservation activity. Matusin et al. (Citation2014) and Saikim et al. (Citation2015) exemplify tourists’ opinions to support the inclusion of invertebrates into the walking trail activity of Tabin Wildlife Reserve, Sabah the preliminary entotourism activity. Yet, are tourists able to accept the concept of entotourism as another focused ecotourism products, especially in Sabah? Therefore, this study aims to ascertain tourists’ receptivity to the concept of entotourism activities in Sabah.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entotourism for conservation

Entotourism is an invertebrate-focused ecotourism activity. The main goal of incorporating invertebrates into ecotourism activity is to raise awareness of invertebrates’ roles in the ecosystem (Huntly et al., Citation2005), leading to improved conservation action and lifting pressure ecotourism activities that solely focus on the Big Five (Matusin et al., Citation2014). Invertebrate provides an enormous array of goods and services to human and ecosystem including decomposition of dead plants and animals (Srivastava & Saxena, Citation2007), pollination (Gallai et al., Citation2008) and biological indicators (Losey & Vaughan, Citation2006). In fact, invertebrates are integral to life on Earth but often neglected in our natural capital (Collen et al., Citation2012). Invertebrate conservation is hard to justify when people have negative perceptions of them (potential of pest or health threat), and the public is unaware of the invertebrate role in ecosystems. Without information dissemination, people tend to disregard invertebrates as vital for ecosystem functioning or need protection (Martin-Lopez et al., Citation2007).

In most cases, policymakers and stakeholders assumed that large mammals’ protection as “umbrella” species would also protect other species occupying the same habitats (Cabeza et al., Citation2008). Indeed, the fallacy of umbrella species effectiveness has the detriment of invertebrate conservation by limiting the amount of available funding (Collen et al., Citation2012). Huntly et al. (Citation2005) agreed that people are now tending to be more interested in nature as a whole. This, in turn, has the potential to incorporate a focus on invertebrate activity in ecotourism. Yacob et al. (Citation2011) define ecotourism as interpretative tourism where conservation, understanding and appreciation of the visited environment. Notably, the primary aim of interpretation in ecotourism is to boost awareness and appreciation of fragile nature, the interrelationships between wildlife and habitats and the impact of human activities on nature (Mason, Citation2000). Some of entotourism activity around the world, such as in Mexico, there are tours to watch the spectacles of the annual migration of millions of monarch butterflies (Huntly et al., Citation2005), a glow-worm tour in Australia and New Zealand that attracts a hundred thousand visitors annually (Baker, Citation2003). Next, nearly 500,000 tourists come to Costa Rica and Taiwan for butterfly farm every year (Samways & Samways, Citation2005). In Malaysia, firefly watching is a popular international attraction (Mahadimenakbar et al., Citation2009). The acceptance of these spectaculars entotourism activities shows the support of tourists to this kind of invertebrate-focused ecotourism. Thus, it opens the opportunity for entotourism activity in Sabah.

2.2. Tourists perception of invertebrate

Public perception of insects is a vital key to their conservation and awareness (Snaddon & Turner, Citation2007). Most public dislike insects mainly as they can transmit diseases. This perception could hinder the development of entotourism. (Boileau & Russell, Citation2018). One of the main challenges is the generally negative attitude toward invertebrates (Huntly et al., Citation2005). Thus, it is necessary to understand the public perceptions of the environment through tourism (Petrosillo et al., Citation2007). People perceive animals as influenced by many attributes such as gender, age, educational level and cultural factors (Borgi & Cirulli, Citation2015). Woods (Citation2000) adds that public perspective on insects is related to their experience and education. Thus, the influence of socio-economic status, cultural ties and expertise on how people perceive environmental quality should be investigated further (Petrosillo et al., Citation2007). Mainly, gender research plays a significant role in defining ecosystem services perception (Citation2012). Many studies indicated that perceptions are influenced by many variables together with gender, including wealth, education, cultural traditions and age (Muhamad et al., Citation2014; Daw et al., Citation2011; Fortnam et al., Citation2019; Iniesta-Arandia et al., Citation2014; Oteros-Rozas et al., Citation2014; Plieninger et al., Citation2013). A review from Yang et al. (Citation2018) indicated that only 0.7% of the articles on ecosystem services study related to gender. Researches suggest that the perception of ecosystem services is highly gender-biased. Women tend to perceive more water quality, erosion control, soil formation, habitat conservation, and sustainable biodiversity. Men value more regulating fuel, timber and extreme event mitigation services (Abdelali-Martini et al., Citation2008; Yang et al., Citation2018). A review by Meinzen-Dick et al. (Citation2014) suggested that the study of attitudes, desires and preferences between genders is essential in terms of sustainable environmental development. Therefore, this study aims to determine the gender influence on tourists’ perception of Sabah’s entotourism concept to fill the gap.

3. Methods

3.1. Research paradigm and methodology

This study relied on the pragmatism paradigm that postulates the importance of focusing attention on the research problem in social science study and applying a pluralistic approach to acquire knowledge about the issue (Tashakkori & Teddlie, Citation2010). Creswell (Citation2014) emphasises that pragmatism is not solely engaged in any one system of philosophy and reality. It applies mixed-method research that liberally draws both quantitative and qualitative assumptions (Creswell, Citation2014). The explanatory sequential mixed method can determine the tourists’ perception of entotourism activity in Sabah. The design helped this study provide solid and reliable quantitative findings that further explore details via qualitative inquiry.

3.2. Data collection

This study focused on two specific locations in Sabah: Tabin Wildlife Reserve (TWR) and Kota Kinabalu City Centre (KKCC). Both places are hotspots for eco-tourists in Sabah. shows the location of TWR and KKCC. Respondent criterion is the tourist who participated in nature or ecotourism activities either in TWR or KKCC area. We used a purposive sampling technique. For the questionnaire survey, we implemented a Personal Meaning of Insects Map (PMIM) technique to assess respondents’ perception without fear of judgment or correction (Lemelin et al., Citation2016). We conducted the session at the departure hall of Kota Kinabalu International Airport and Kota Kinabalu City, including islands in Tunku Abdul Rahman Park. We approached the respondents while they were waiting for flight boarding and during sunbathing in the islands. There are two sections in the questionnaire tourist perception and awareness (). A face-to-face semi-structured questionnaire was conducted after the tourists finished their trail walk activity for the interview session. There were five fundamental questions related to tourist perception on entotourism activity elicited during the interview session (). We interviewed a total of 384 tourists from September 2018 to January 2019.

3.3. Data analysis

Quantitative findings were analysed using a t-test via Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and presented through Spider-Web configuration. Spider-Web configuration is an effective model for visual representation, especially for comparing different individuals or groups (Laverack, Citation2006). While qualitative findings were analysed using content analysis via Leximancer version 4.0 to examine the content of textual document collections and display the extracted information visually. Content analysis is used to quantify the qualitative findings and involves a non-linear analysis process (Creswell, Citation2014).

4. Results

This study demonstrated that people have a slightly different perception of insects and awareness based on their gender. Demographics will affect people’s perspective on ecosystem services and conservation, but its influence on insects still needs to be concerned more. Thus, it is important to share to ensure insects’ proper management through entomological ecotourism or entotourism.

Three hundred and eighty-four participants responded to the questionnaire, 34.4% were males, and 65.6% were females. There were 47.4% Malaysian and 52.6% non-Malaysian tourists who participated in this survey. Their ages ranged from 13 to 28 as adolescence, and young adults were the domain parts (45.3%), and people from 51 to 65 (8.6%) and beyond 66 years old were the least (2.1%). In the education section, the bachelor was the most respondents. Respondents who had bachelors degree were the highest in number (54.2%), primary school, doctorate and other were the least below 5%. The participants were interviewed randomly during the daytime.

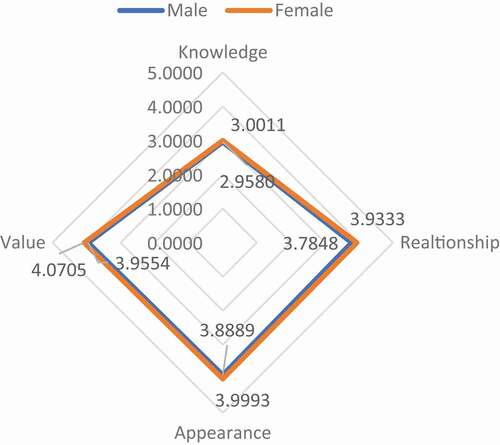

T-test shows that there are no significant differences in both insect perception and awareness between males and females. of spider Web configuration indicated their mean difference between each factor and that gender biases still slightly influenced ecosystem services perception and conservation awareness. Women have a more positive response than men. demonstrated a mean list of tourists’ perception and their awareness regarding insects between men and women. It interprets a range of strengths and weaknesses among tourists of insects’ knowledge; scale of women participants is all larger than men. The highest was the ecology part in terms of knowledge of insects. It was a moderate perspective of insects in the ecosystem services and its relationship to nature, women perception (=3.38) is higher than men (

=3.19). The public’s knowledge of human relationships has the second highest value, where men show low perspective. The other biological knowledge of insects shares a similar value between genders which all-around 3. Female respondents have a similar preference to male respondents on insect appearance. They all showed high interest in it. The mean disparities in all aspects were less than 0.2, and only respondents thought that small size insects are not suitable for appearance. Male and female participants’ views on the appearance of insects do not significantly differ in this case. When tested people’s awareness of insects relationship to humans, it showed no significant difference between genders. Participants value insects more especially when discussing whether insects are beneficial insects or pests. Females and males have a bigger perspective on insects as necessary parts of human life and live in harmony with insects, which means the difference is more significant than 0.22. Further interpretation from insects’ value illustrates all participants have positive thinking of insects value such as pollinator, the value of food web and economical industry. The most significant difference is in insects’ research value, where the gap of mean is 0.22.

Table 1. Tourists’ profile in terms of gender, nationality, age, education level and place of residence (n = 384)

Table 2. Mean of Perception and Awareness

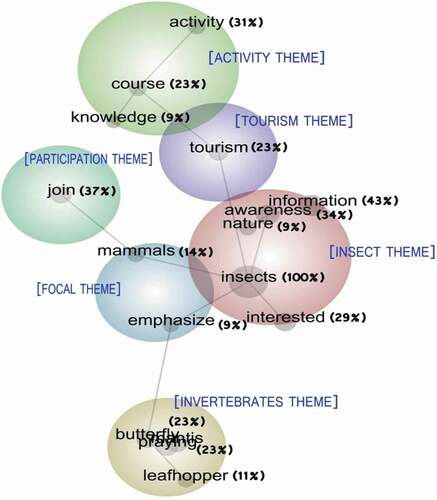

For qualitative findings, Leximancer extracted the content of textual documents into visual information. enumerates the ranked concepts of word-like based on the occurrence and co-occurrence in the document text displayed in the percentages of relevance. The word Insects was the most frequent word extracted in the document text with 100% relevance (35 counts), followed by information with 43% relevance (15 counts), Join with 37% relevance (13 counts), awareness with 34% (12 counts), activity with 31% (11 counts) and Interested with 29% (10 counts). Praying Mantis, Butterfly, Tourism and Course represented 23% relevance (8 counts) each, Mammals with 14% relevance (5 counts) and Leafhopper with 11% (4 counts). Nature, Emphasise and Knowledge were the lowest occurrences with 9% relevance (3 counts).

Table 3. Ranked Concept of Leximancer

displays the visual concept map produced to reveal the most common themes and concept disclosed in the interview text document based on the occurrences and co-occurrences. The themes were heat-mapped to indicate its importance where the hottest or most crucial theme will appear in red and next hottest orange and so on according to the colour wheel (Leximancer, Citation2011). Six dominant themes represented tourists’ perceptions to the concept of entotourism in ecotourism activity, namely Insects, Participation, Tourism, Activity, Invertebrates and Focal ().

Based on the Leximancer map, the Insects theme assigned with red colour was the most important theme in this concept map and connected to other concepts within the theme such as Information, Awareness, Interested and Nature. The second important theme was the tourism theme assigned with purple colour related to the Activity theme (light green colour). This activity theme comprised two concepts: Activity and Knowledge. Next, the Focal theme assigned with blue colour composed two concepts: Mammals and Emphasise, directly connected to Insects theme. The last two themes were the Participation theme assigned with dark green colour and Invertebrates theme with Brown colour. Participation themes were connected with Mammals concepts while the Invertebrates theme connected to Emphasise concepts. Invertebrates theme comprised three concepts, namely, Butterfly, Praying Mantis and Leafhopper.

Based on the map, most respondents were very positive with the information and awareness on insects and put their interest towards it. Besides, informants also supported the ecotourism activity related to insects which provided them with some new knowledge about this group of animals. Despite that, respondents also mentioned that their focus in visiting the Tabin Wildlife Reserve (TWR) was to enjoy the mammals (like elephants, monkeys and small mammals). However, they also emphasised some examples of insects that caught their interest during the visit, such as butterflies, praying mantis and leafhoppers. It is probably the potential of insects that can be “commercialise” as a new attraction.

5. Discussion

Studies previously proved that its popularity influenced people’s perception of insects (Lemelin et al., Citation2017), flagship and beautiful insects also human-like animals will help and easily attract people’s attention more. It always favoured tourists towards animal watching activities (Agrawal, Citation2017; Lemelin, Citation2013). Nevertheless, insects’ experience was the main factor relevant to the public’s entomophobia, which determines people’s judgment of insects (Hayati & Minaei, Citation2015; Tan et al., Citation2015; Shahriari, Citation2018). Participants’ knowledge of insects resulted in the middle level. Shortage of insect education could be the main issue where mammals and other big animals were usually more concerned. The information they learned about insects may also relate to their age, education, and cultural background, which still need further study. Appearance does not affect people’s preference for insects. Men and women have no notable difference when it comes to insects appearance. Insects of various colours and shapes could also fit for all kinds of people’s preference, which is a positive way of promoting insects. Insects have been utilised for nearly 3000 years; their both ecological and economical values, such as silk, honey, medicine and food, are widely accepted by people (Chen & Chen, Citation2009; DeFoliart, Citation1995). Hence, the respondents had more positive feedback when asked about the value of insects. Women seem to have higher awareness among all aspects compared to men. Studies of people’s perception of ecosystem services explained that women are often more sensitive to ecosystem services (Fortnam et al., Citation2019; Yang et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, females have a higher awareness of ecosystem services than males (Martín-López et al., Citation2012). Women are more conscious of the importance of ecosystem services and are more willing to conserve them, such as biodiversity (Yang et al., Citation2018). However, few kinds of research have studied gender differences in the insects field compared to other ecosystem services. We suggest that future researchers should study a different population or look at a different set of variables.

As revealed by Leximancer, tourists expressed their interest in insects after participating in the preliminary entotourism activity in TWR. This shows a positive perception of tourists on the concept of entotourism. Entotourism activities need few improvements to encourage high demand from the tourists since invertebrates generally have much interest in it and are able to attract people in many ways (Lemelin, Citation2009). Indeed, many people want to observe the beauty and subtle features of invertebrates. Alternately generate interest from the tourists who wanted to experience how invertebrates contribute to human well-being (Yi et al., Citation2010) and the practical information about what they could do to help protect the wildlife (Ballantyne et al., Citation2009). Even though some tourists pointed out their focus on mammals and small mammals during the ecotourism activity, they still raise their intention to participate in the preliminary entotourism activity and gain more knowledge on invertebrates. Importantly, tourists’ interest has been established as the core indicators to encourage ecotourism activity sustainability (Bagul & Eranza, Citation2010). The public perception of insects is not as strong as that for other animals since people are more perceived and attracted by animals that human-like, aesthetic and flagship species (Boileau & Russell, Citation2018, Citation2018; Gurung, Citation2003; Lemelin et al., Citation2016; Woods, Citation2000). However, both knowledge and awareness of insects are highly dynamic and vary according to the situation (Gurung, Citation2003). We urge more research, and conservation studies should continuously focus on insects . Thus, it is a huge opportunity to elevate tourists’ interest via entotourism activity, especially in Sabah as one of the ecotourism attractions. Increased awareness can support improved conservation effort in favour of invertebrates.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study aimed to determine the perception of tourists toward entotourism activity in Sabah. The findings revealed that gender bias might have no significant differences in association with insects compared to other studies. The concept of insects, such as basic knowledge, relationship, appearance, and value, should also be considered when related to insects tourism as well as education and management. Demographic dimensions such as gender, nationality, age, and education level should be considered in ecosystem services assessment. It provides a better strategy for manager, educator, and innovator for conservation research, management, and policy. However, the study of insect perception and awareness is still limited. The understanding of the demographic biases to international conservation and management is significant. Insects biology and protection is also crucial to ecosystem service, not only for its conservation but also to entotourism. People still have limited knowledge of insects and their essential role in ecosystems. Overall, this study has brought a new opportunity to broaden and advance the scope of current and future ecotourism activity, especially in Sabah. It aided perceive positive perception among tourists towards entotourism activity, especially invertebrates species. Eventually, encourage the invertebrate conservation action.

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Sabah Parks for their support during the field works and data collection.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fiffy Hanisdah Saikim

Our entomological ecotourism research group consists of academia from four universities in Malaysia that are Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS), Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) and Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM). The team comes from various fields of expertise: recreation, ecotourism, business management, entomology, ecology, and conservation. Our research team dedicated to promoting insects’ conservation through ecotourism by creating public awareness and providing guidelines and standards for sustainable entomological ecotourism. We are productively in academia to make tourism a viable conservation tool, protection of insect diversity, and sustainable entomological ecotourism or entotourism development in Malaysia. Through various entotourism projects and initiatives, our team aims to: increase awareness of entotourism and responsible insect-based travel; expand entomological learning opportunities; connect travel professionals and ecotourism stakeholders, and help shape policy to mainstream sustainability in entotourism.

References

- Abdelali-Martini, M., Amri, A., Ajlouni, M., Assi, R., Sbieh, Y., & Khnifes, A. (2008). Gender dimension in the conservation and sustainable use of agro-biodiversity in West Asia. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(1), 365–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2007.06.007

- Agrawal, A. (2017). Monarchs and milkweed: A migrating butterfly, a poisonous plant, and their remarkable story of coevolution. Princeton University Press.

- Ahmad, J. A., Abdurahman, A. Z. A., Ali, J. K., Khedif, L. B., & Bohari, Z. (2014). Social Entrepreneurship inEcotourism: An opportunity for fishing village of Sebuyau, Sarawak Borneo. Tourism, Leisure and Global Change, 1, 38–48. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jati_Kasuma/publication/283562713

- Bagul, A. H., & Eranza, D. R. (2010). Success indicators for ecotourism site. Social transformation platform. Proceedings of regional conference on tourism research. August 13-16, 2010. Penang Malaysia.

- Baker, C. H. (2003). Australian glow-worms: Managing an important biological resource. Australian cave and karst management association inc. Journal, 53, 13–16. http://www.online-keys.net/sciaroidea/2000_/Baker_2003_GLOW-WORMS.pdf

- Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Hughes, K. (2009). Tourists” support for conservation messages and sustainable management practices in wildlife tourismexperiences. Tourism Management, 30(5), 658–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.11.003

- Boileau, E., & Russell, C. (2018). Insect and human flourishing in early childhood education: Learning and crawling together. In Research handbook on childhoodnature: Assemblages of childhood and nature. New York, NY: Springer. Advance of print. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51949-4_65-1

- Borgi, M., & Cirulli, F. (2015). Attitudes toward animals among kindergarten children: Species preferences. Anthrozoös, 28(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279315X14129350721939

- Brooks, J., Franzen, M., Holmes, C., Grote, M., & Borgerhoff, M. (2006). Testing hypotheses for the success of different conservation strategies. Conservation Biology, 20(5), 1528–1538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00506.x

- Bruhl, C. A., Gunsalam, G., & Linsenmair, K. E. (1998). Stratification of ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in a primary rain forest in Sabah, Borneo. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 14(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467498000224

- Cabeza, M., Arponen, A., & Van, T. A. (2008). Top predators: Hot or not? A call for systematic assessment of biodiversity surrogates. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45(3), 976–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01364.x

- Chen, X., Feng, Y., & Chen, Z. (2009). Common edible insects and their utilisation in China. Entomological Research, 39(5), 299–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5967.2009.00237.x

- Chong, K. K. 2004. Tourism, culture and environment, Sabah. BBEC 2004: Resource use human behaviour. Procceding of Bornean biodiversity and ecosystem conservation information conference. February 24-26, 2004. Kota Kinabalu Sabah.

- Chung, A. Y. C., Eggleton, P., Speight, M. R., Hammond, P. M., & Chey, V. K. (2000). The diversity of beetle assemblages in different habitat types in Sabah, Malaysia. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 90(6), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007485300000602

- Collen, B., Bohm, M., Kemp, R., & Baillie, J. E. M. (2012). Spineless: Status and trends of the world’s invertebrates. Zoological Society of London.

- Collins, N. M. (Ed.). (2012). The conservation of insects and their habitats. Academic Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design (4th ed.). SAGE Publication, Inc.

- Daw, T. I. M., Brown, K., Rosendo, S., & Pomeroy, R. (2011). Applying the ecosystem services concept to poverty alleviation: The need to disaggregate human well-being. Environmental Conservation, 38(4), 370–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892911000506

- DeFoliart, G. R. (1995). Edible insects as minilivestock. Biodiversity and Conservation, 4(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00055976

- Diamantis, D. (2004). Ecotourism. Thompson Learning.

- Floren, A., & Linsenmair, K. E. (1998). Diversity and recolonisation of arboreal Formicidae and Coleoptera in a lowland rain forest in Sabah, Malaysia. Selbyana, 19(2), 155–161. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41759986

- Fortnam, M., Brown, K., Chaigneau, T., Crona, B., Daw, T. M., Gonçalves, D., Hicks, C., Revmatas, M., Sandbrook, C., & Schulte-Herbruggen, B. (2019). The gendered nature of ecosystem services. Ecological Economics, 159, 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.018

- Gallai, N., Salles, J.-M., Settele, J., & Vaissiere, B. E. (2008). Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecological Economics, 68(3), 810–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014

- Gurung, A. B. (2003). Insects–a mistake in God’s creation? Tharu farmers’ perception and knowledge of insects: A case study of gobardiha village development committee, Dang-Deukhuri, Nepal. Agriculture and Human Values, 20(4), 337–370. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AHUM.0000005149.30242.7f

- Hayati, D., & Minaei, K. (2015). Investigation of entomophobia among agricultural students: The case of Shiraz University, Iran. Journal of Entomological and Acarological Research, 47(2), 43–45. https://doi.org/10.4081/jear.2015.4817

- Huntly, P. M., Noort, S. M., & Hamer, M. (2005). Giving increased value to invertebrates through ecotourism. South African Journal of Wildlife Research, 35(1), 53–62. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/EJC117205

- Iniesta-Arandia, I., García-Llorente, M., Aguilera, P. A., Montes, C., & Martín-López, B. (2014). Socio-cultural valuation of ecosystem services: Uncovering the links between values, drivers of change, and human well-being. Ecological Economics, 108, 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.09.028

- Kim, K. C. (1993). Biodiversity, conservation and inventory: Why insects matter. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2(3), 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00056668

- Kumar, U., & Asija, M. (2004). Principles and conservation (2nd ed.). AGROBIOS.

- Laverack, G. (2006). Evaluating community capacity: Visual representation and interpretation. Community Development Journal, 41(3), 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsi047

- Lemelin, R. H. (2009). Goodwill hunting? Dragon hunters, dragonflies and leisure.Current Issues in Tourism. 12(3), 235–253.

- Lemelin, R. H. (Ed.). (2013). The management of insects in recreation and tourism. Cambridge University Press.

- Lemelin, R. H., Dampier, J., Harper, R., Bowles, R., & Balika, D. (2017). Perceptions of insects: A visual analysis. Society & Animals, 25(6), 553–572. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341469

- Lemelin, R. H., Harper, R. W., Dampier, J., Bowles, R., & Balika, D. (2016). Humans, insects and their interaction: A multi-faceted analysis. Animal Studies Journal, 5(1), 65–79. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol5/iss1/5

- Leximancer. (2011) . Leximancer Manual.

- Losey, J. E., & Vaughan, M. (2006). The economic value of ecological services provided by insects. Biosciences, 56(4), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[311:TEVOES]2.0.CO;2

- Mahadimenakbar, M. D., Fiffy, H. S., & Godoong, E. (2009, June). Studies on the potential of fireflies watching tourism for firefly (Coleoptera: Lampyridae; Pteroptyx spp.) Conservation. In Proceedings of the international seminar on wetlands & sustainability; wetland & climate change: The need for intergration, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia (pp. 26–28).

- Martín-López, B., Iniesta-Arandia, I., García-Llorente, M., Palomo, I., Casado-Arzuaga, I., Del Amo, D. G., González, J. A., Palacios-Agundez, I., Willaarts, B., González, J. A., Santos-Martín, F., Onaindia, M., López- Santiago, C., Montes, C., & Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2012). Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS One, 7(6), e38970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038970

- Martín-López, B., Iniesta-Arandia, I., García-Llorente, M., Palomo, I., Casado-Arzuaga, I., Del Amo, D. G., González, J. A., Palacios-Agundez, I., Willaarts, B., González, J. A., Santos-Martín, F., Onaindia, M., López-Santiago, C., Montes, C., & Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2012). Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS One, 7(6), e38970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038970

- Martin-Lopez, B., Montes, C., & Benayas, J. (2007). The non-economic motives behind the willingness to pay for biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 139(1–2), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.06.005

- Mason, P. (2000). Zoo tourism: The need for more research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(4), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580008667368

- Matusin, A. M. R. A., Suki, N. M., Dawood, M. M., & Saikim, F. H. (2014). Giving Increased value to Invertebrates through Ecotourism. IJAAEE, 1(2), 179–182. https://iicbe.org/upload/6536C614060.pdf

- Meinzen-Dick, R., Kovarik, C., & Quisumbing, A. R. (2014). Gender and sustainability. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 39, 29-55. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-101813-013240 https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-101813-013240

- Muhamad, D., Okubo, S., Harashina, K., Parikesit, Gunawan, B., Takeuchi, K. (2014). Living close to forests enhances people's perception of ecosystem services in a forest-agricultural landscape of West Java, Indonesia. Ecosyst. Serv., 8, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.04.003

- Nbsap, M. (2014). The 5th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

- New, T. R., & New, T. R. (2009). Insect species conservation. Cambridge University Press.

- Oberhauser, K., & Guiney, M. (2009). Insects as flagship conservation species. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews, 1(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1163/187498308X414733

- Oteros-Rozas, E., Martín-López, B., González, J. A., Plieninger, T., López, C. A., & Montes, C. (2014). Socio-cultural valuation of ecosystem services in a transhumance social-ecological network. Regional Environmental Change, 14(4), 1269–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0571-y

- Petrosillo, I., Zurlini, G., Corliano, M. E., Zaccarelli, N., & Dadamo, M. (2007). Tourist perception of recreational environment and management in a marine protected area. Landscape and Urban Planning, 79(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2006.02.017

- Plieninger, T., Dijks, S., Oteros-Rozas, E., & Bieling, C. (2013). Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy, 33, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.12.013

- Saikim, F. H., Matusin, A. M. R. A., Suki, N. M., & Dawood, M. M. (2015). Tourists perspective: inclusion of entotourism concept in ecotourism activity. Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation, 12, 55–74. https://jurcon.ums.edu.my/ojums/index.php/jtbc/article/view/272

- Samways, M. J., & Samways, M. J. (2005). Insect diversity conservation. Cambridge University Press.

- Shahriari-Namadi, M., Tabatabaei, H. R., & Soltani, A. (2018). Entomophobia and Arachnophobia Among School-Age Children: A Psychological Approach. Shiraz E-Medical Journal, 19(7). https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.64824

- Snaddon, J. L., & Turner, E. C. (2007). A child’s eye view of the insect world: Perceptions of insect diversity. Environmental Conservation, 34(1), 33–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892907003669

- Srivastava, R. C., & Saxena, R. C. (2007). Entomology at a glance (3rd edition). Agrotech Publishing Academy.

- Straub, L., Williams, G. R., Pettis, J., Fries, I., & Neumann, P. (2015). Superorganism resilience: Eusociality and susceptibility of ecosystem service providing insects to stressors. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 12, 109–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2015.10.010

- Tan, H. S. G., Fischer, A. R., Tinchan, P., Stieger, M., Steenbekkers, L. P. A., & Van Trijp, H. C. (2015). Insects as food: Exploring cultural exposure and individual experience as determinants of acceptance. Food Quality and Preference, 42, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2015.01.013

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (2010). SAGE handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural. Sage.

- Triplehorn, C. A., & Johnson, N. F. (2005). Study of Insects (7th edition). Peter Marshall.

- Weaver, O. (2008). Ecotourism (2nd ed.). John Willey & Sons Australia Ltd.

- Woods, B. (2000). Beauty and the beast: Preferences for animals in Australia. Journal of Tourism Studies, 11(2), 25–35. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/24139/1/24139_Woods_2000.pdf

- Yacob, M. R., Radam, A., & Samdin, Z. (2011). Tourists perception and opinion towards ecotourism development and management in Redang Island Marine Parks, Malaysia. International Business Research, 4(1), 62.

- Yang, Y. E., Passarelli, S., Lovell, R. J., & Ringler, C. (2018). Gendered perspectives of ecosystem services: A systematic review. Ecosystem Services, 31, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.03.015

- Yi, C., He, Q., Wang, L., & Kuang, R. (2010). The utilisation of insect resources in Chinese rural area. Journal of Agriculture Science, 2(3), 146–154.

Appendix

Table A1 Questionnaire surveys

Appendix

Table A2 In-depth semi-structured interview questions