Abstract

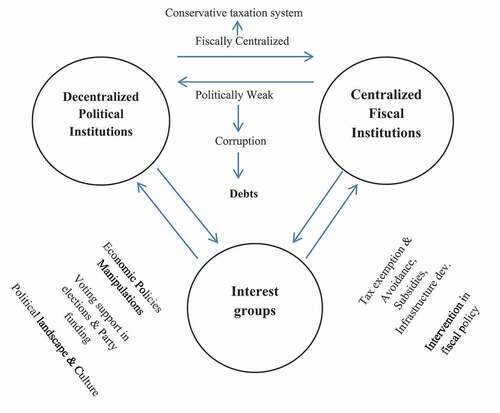

The political and fiscal institutions are arguably the most significant factors that determine the way a society operates. Some countries, such as the USA and Canada, have decentralized political and fiscal institutions, and some are centralized, e.g., China and Singapore. However, this is not true in Pakistan. This paper, first, explains that Pakistan has decentralized political and centralized fiscal institutions. It then describes how the Pakistan government and interest groups interact with each other within such an asymmetric system. Finally, it analyzes the consequences, how governments and interest groups’ interaction leads to cultural polarization, and centralization of the taxation system, which carries the public debts at the uncontrolled threshold.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Usually, some countries are decentralized politically and fiscally, and some are centralized in both dimensions.

The USA and Canada have decentralized politically and fiscally; simultaneously, China and Singapore are excellent examples of centralization.

The above assumption does not hold in Pakistan; it has decentralized political institutions and centralized fiscal institutions as a federalist country. The problem is why has Pakistan adopted politically decentralized and fiscal centralized?

It has been analyzed that interest group’s intervention shapes the fiscal and political institutions asymmetrically.

The interest group’s intervention mark the political institutions as decentralized and weak. At the same time, they shape the centralized fiscal institutions. Consequently, it increases economic instability, corruption, growing debts, and a centralized taxation system.

1. Introduction

Fiscal and political institutions are often assumed to be symmetric, which means they should be both decentralized or both centralized within a country. Guibert and Lanvin (Citation1984) explain that the USA is a fiscally and politically decentralized country. In contrast, China is considered centralized in both dimensions (Xu, Citation2011). However, this assumption does not hold in Pakistan. Its political system is decentralized, whereas its fiscal structure is centralized. According to Cheema et al. (Citation2005) and Jalal (Citation1995), Pakistan has a decentralized political-institutional network. By the 1973 constitution,Footnote1 Pakistan has entirely decentralized political governments at three layers: federal, provincial, and local governments.

Each government level is responsible for its general public after the election. The elections are held every five years for federal and provincial governments, while four years for local government.Footnote2 On the fiscal side, some researchers conclude that Pakistan’s fiscal system is centralized: for example, Cevik (Citation2016) analysis determines that the public revenue remains highly centralized in Pakistan. The federal government collects a large part of its tax revenues, whereas all provinces collectively contribute a minor share. In contrast to the decentralized political system, the fiscal structure looks highly centralized in expenditure, revenue, tax autonomy, and transfers. The federal government spends 63.1% of total government expenses. At the same time, it holds most tax revenue powers and collects 91.3% of total government revenueFootnote3, and transfers it to the provincial government by federal transfer through NFC award. According to Morozov (Citation2016) and Schneider (Citation2003a), the fiscal degree of centralization of an economy is evaluated at the sub-national share of both expenditures and revenues. The main point is that the higher the percentage shares of subnational governments expenditures and revenues, the higher the State’s degree of (de)centralization. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate why Pakistan has adopted asymmetric political and fiscal systems. How can we understand such asymmetry? What shapes the relationship between fiscal and political systems? This paper explains the fiscal and political structures in Pakistan and highlights the role of interest groups in modeling them asymmetrically.

This paper argues that interest groups played an essential role in shaping this asymmetric political and fiscal system. In Pakistan, political institutions are heavily influenced by interest groups, including traditional elites (landlords and religious), professional elites (warlords and bureaucrats), and business elites (industrialists, real estate tycoons, and media). The lobbying in politicians and elites makes interest groups more potent in substitute; they attempt to manipulate the fiscal and economic policies in their favor, leading to an inefficient centralized taxation system with tax collections recorded less than 13% of GDP.Footnote4 As a result, a remarkable rise in the current public spending, in the presence of weak performing conservative taxation system, poses various difficulties for policy-makers. Although growing interest payments on debts upsurge the government’s problems, and mark-up payment estimated 83.5%Footnote5 of the federal government budgeted revenue in 2019–20.Footnote6 The tension on the line of control with India is another noticeable problem that increases security-related spending and recorded 42.7% of federal revenue in 2019–20.Footnote7 Simultaneously, growing current federal expenditures reduced the development spending and restrict it to under 5% of GDP in 2018. However, these mark-up payments, subsidies, military budget, increasing current federal government expenses, damage economic efficiency, and increased public debts to the uncertain level that recorded 97.9% of GDP in 2019. It confines the fiscal structure centralized and perceived that the country has a conservative centralized taxation system.

The remaining parts of this paper are organized as follows: section 2 is about the literature review. Section 3 demonstrates political decentralization, and section 4 illustrates fiscal centralization. Section 5 is about the intervention of interest groups in political and fiscal institutions, and section 6 depends on the discussion, consequences, and outcomes of the research. The last part is about conclusions and recommendations.

2. Literature review

The importance of the relationship between fiscal and political institutions is well documented, and many researchers explain it in different ways. The extant literature extensively explores and describes fiscal federalism and political-fiscal (de)centralization. However, different researchers describe the influence of stakeholders differently in political and fiscal institutions and calculate the various essential results. Therefore, the influence of stakeholders has been explored widely in the legislative and budgetary literature but without convincing results. There are many definitions to explain the term “(de)centralization” in the literature. The terms “centralization” and “decentralization” refer to features of multiple systems. They contain various numbers of tier and non-tier governments (Treisman, Citation2002). Bryce (Citation1901) was the first to think systematically and comparatively about the centripetal and centrifugal forces leading to centralization and decentralization, and the constitutional devices countries include federations which contain the centralized and decentralized form of government. Schneider (Citation2003a) described states where political decentralization refers to how central governments allow non-central government tiers. While Rondinelli and Nellis (Citation1986) define devolution as a transfer of responsibilities and allocating resources from the federal to the last layer of governments. Leacock (Citation1908) argues that classic federalism was increasingly ill-suited to the needs of governing the modern economy and predicts this would lead to centralization.

Similarly, Corry (Citation1941) detects a generalized pattern of growing centralization, which he attributes to modern industrial society’s development. Falleti (Citation2005) describes political decentralization as a set of constitutional amendments and electoral reforms. West and Christine () explain that the political decentralization provides its defective structure, i.e., mostly based on central to subnational to local. Jalal (Citation1995), Callard (Citation1957), and Fisher (Citation2000) describe that General Ayub liked the British colonialists and established a local governmental system for the first time as a third official tier. Jalal (Citation1995) states that, during the period of General Zia, the local governments were restored for the second time in the country through the declaration of local government ordinances (LGOs). According to NRB (Citation2001), the third attempt was made by General Musharraf’s regime via the SBNP LGOs in 2001. After the 18th amendment to the constitution in 2010 under the Art: 140-A (1), the federal government emphasized to each province to establish a local government system and legislation under the provincial local government act and give the rights to provincial assemblies to decide whether they devolved political, administrative, and financial responsibility to local authorities.

The practice of fiscal decentralization has been tremendously affected by the USA’s experience after the Second World War (Olson, Citation1968; Richard et al., Citation1959). In fiscal decentralization, the central government devolved their responsibilities and resources up to the last level of government (Rondinelli, Citation1983). Schneider (Citation2003a) defines fiscal decentralization as the percentage of surrender by the federal government, which fiscally influences sub-level entities relative to central control. Kee (Citation2003) defines fiscal decentralization as the devolution of responsibilities by the central government to local governments (state, regions, and municipalities finance), which specify functions of expenditures, revenue, and administrative duties. The fiscally decentralized governance structure is probably contended to offer taxes and public goods provisions at the last tier (Brennan & Buchanan, Citation1980). Cevik (Citation2016), an IMF researcher, explains that the revenue collection remains highly centralized in Pakistan, and most of the revenue collection relies on the federal government’s domain. Oates (Citation2005) explains that decentralization of taxation will probably generate conflict among provincial governments. It increases the competition between jurisdictional levels, resulting in a decrease in tax income. Cyan and Bahl (Citation2011) state that subnational governments are heavily dependent on transfers from the federal level; they reconnect the revenue and expenditure responsibilities and increase accountability challenges at the middle levels. Searle and Ahmad (Citation2005) assume that fiscal transfers are an essential job to guarantee the equal and efficient distribution of public goods. Measuring the degree of fiscal (de)centralization is in the literature. Although Schneider (Citation2003a) and Morozov (Citation2016) explain that to analyze the fiscal’s degree of centralization of an economy is to perspective of the subnational share of both expenditures and revenues. The main point is that the higher the percentage shares of subnational government’s expenses and taxes, the higher the (de)centralization. Arzaghi and Vernon Henderson (Citation2005) state that the constant changes and the informal structure of financial institutions declined from 0.74 in 1975 to 0.64 in 1995. Countries in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa have the highest centralization.

Influence of interest groups in political and fiscal institutions: Stakeholders have one thing in common: their interests. No nation in the world developed its unconstrained institutional operations without any politicians’ intervention and concern for the benefit (Collins, Citation2011). Klimovski et al. (Citation2016) define that interest groups are organizations separated from the government; they often have very close ties with the government and have an interest in influencing public policies. These attempts to intervene in policy-making may occur through different mechanisms, such as direct communication with government officials, participation in public hearings, drafting reports to a government member on specific policy issues, and media camping (Chari et al., Citation2010). Such groups may also have different resources to influence policy-making, party funding during an election campaign, expertise on policy issues, and information on other policy-makers’ opinions (Dür & De Bièvre, Citation2007). Some political systems are more politicized than others, but civil servants always support powerful politicians in Pakistan (Khurshid, Citation2011). The administrative and political system in Pakistan depends heavily on a nepotism network whereby politicians cooperate with bureaucracy to share and defend each other’s interests (Lyon, Citation2021). This unconventional intervention by politicians indicates weak institutional control, where their interest groups enjoy the benefits of institutional disabilities, which insist on corruption, and abandoned the public debt burden in the economy (Shabbir, Citation2013). The revenue department’s government officials frequently manipulate the tax policies to favor powerful people in business and allow them an amnesty scheme and exemptions (Levi & Suddle, Citation1989; Tunio et al., Citation2020; Umer, Citation2011).

Interest groups have a collective membership organization that engages with federal policies. The legislative actions are influenced and affected by consultants/lawyers’ activities when they work for the interest group, and every group has different preferences (Jordan et al., Citation2004). Some advanced countries have tackled the prevalence of these competing goals by regulating the interest groups. The USA and Canada, for instance, have monitored interest groups through the “Lobbying Disclosure Act 1995” and “Lobbyist Code of Conduct,” respectively, for many years. They have been designed to ensure and enhance integrity in the public sector. The European Union followed suit and promoted the “Transparency Register” to improve politicians’ regulations related to influencing policy-making.

2.1. Research design

This paper is a review and analysis of socioeconomic performance interactions through a peer lens. We combine different approaches for measuring political decentralization in Pakistan. We collect data from the State Bank of Pakistan, Ministry of Finance, Pakistan, and parliament for fiscal and political analysis. Further, we evaluate the compatibility of interest groups and government and then analyze the consequences of the asymmetric political–fiscal intergovernmental system. For analysis, the potential material is selected through the research journals and filtered based on quality. Our preference is to choose the related impact factor and ABCD ranked journals. Furthermore, we select the top newspaper articles nationally and internationally for analysis of elites and government compatibility.

3. Political decentralization

The federation of Pakistan has a constitutionally decentralized governmental structure; in that sense, the federal and provincial governments divide their functions, responsibilities, and powers according to the constitution. The country has a unique state structure; it consists of the federal government and four federating units: Sindh, Punjab, Baluchistan, and KP. Further, it includes one provisional province recognized as Gilgit Baltistan, one capital territory, and the region of Kashmir, disputed with India. Moreover, the Federal Administrative Tribal Area (FATA) was also identified as a separate territory before May 2018. Recently, FATA merged into KP province under the 25th amendment in the constitution. After the amendment in constitution under art-246,Footnote8 FATA’s executive authorities are excise under chief minister instead of governor, it has done with away. Now, as part of the province, the executive authority shifted to the Chief Minister of KP.Footnote9

The country’s governmental structure devolved into three layers. The law offers shelter to each level: the federal government under Art-90 (1),Footnote10 the provincial government under Art-129 (1),Footnote11 and the local government under Art-140-A (1).Footnote12 The devolution plan of 2000 delivers the framework intended to guarantee the general public’s authentic interests at the last tier.

Measuring political decentralization is quite challenging; therefore, various researchers use different approaches. Brancati (Citation2006) measures political decentralization and confers sub-central elections, sub-central control over tax power, and sub-central veto over constitutional amendments. Bahl (Citation1999) and Morozov (Citation2016) typically agree upon measuring the degree of political decentralization in light of democratic elections, political stability, and accountability. Therefore, we have measured political institutions’ levels via three dimensions: institutional, legislative, and administrative. According to the law, each level of Pakistan’s political institutions is regulated in the constitution, and every branch has political elections. provides the dimensions and indicators for measuring and analyzing the degree of political decentralization in Pakistan.

Table 1. Dimensions and indicators of political decentralization

3.1. Characteristics of the federal government as a parliamentary system

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan was founded in 1947 after the British regime’s end and the Second World War. Pakistan has a parliamentary system established under the 1973 constitution. The parliament is widely known as the country’s legislative body and is responsible for making rules/regulations/laws enforced at the national level or in any particular region/state. The Art-50 of the constitution describes the parliamentary system, which contains the president, the senate (Upper House), and the national assembly (Lower House). In Pakistan, there are two parliamentary committees: standing committees and select committees (on-demand of members). Standing committees are permanent and play an important role in oversight, and monitor the relevant federal ministries’ responsibilities and functioning. Under the Rules of Procedure 198, each ministry establishes a standing committee, which scrutinizes bills/act/ordinance brought up to them by the house and submits its reports to the Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament). The president is the head of the State and shall represent the unity of the republic.Footnote13 The primary purpose of creating the senate is to give equality in representation to all provinces to minimize the regional representation inequalities in the national assembly. National assembly membership is based on population, and the national assembly is the most dominant parliament house. The senate’s equivalent representation plays a crucial role in preserving national unity and alleviating the small provinces’ fear regarding the dominance of a large region in population. The national assembly is the sovereign legislative body of the country. It is accountable for the lawmaking process, and, from the perspective of the legislative powers, it is enumerated under the constitution. This house is responsible for checks and balances across the executive branch and ensures that the federal government functions within its parameters. The national assembly members are elected for five years through a diverse ballot process widely known as a “parallel system.” The election procedure is broadly described in the constitution of Pakistan Part VIII elections.

In a parliamentary system where the national assembly members elect the prime minister, the president appoints the minister’s cabinet upon the prime minister’s suggestion. These fundamental principles of institutional setup remained unchanged over time. The federation was initially composed of four provinces, one provisional pprovince,and a federal capital territory, each having equal status instead of the interim province because province operations are directly controlled by the federal government and retain residual powers. The senate is less potent than the national assembly but has a significant co-decision-making role that has gained importance over time. The constitution mandates that the Supreme Court (SC) act as a federal umpire and review federal and land laws’ constitutionality.

3.1.1. Static for measures political (de)centralization

The federation was considerably more centralized at its foundation than other federations at the time of its birth. Compared to other federal states in 1950, however, Pakistan was slightly more centralized because of one unit policy from 1955 to 1970. The basic law was characterized by a powerful functional division of power after Pakistan’s constitutional law in 1973.

3.1.1.1. Measuring dimensions

However, measuring the degree of political decentralization is quite tricky. Thus, Kaiser and Vogel (Citation2019) note the deficiency of inadequate measurement and analysis of the vertical distribution over the life of the federation, legislative, administrative, and financial powers. Moreover, the authors aim to fill the void in 22 policy areas and on five fiscal measures by evaluating federal and constituent strength in (de)centralization.

Therefore, we take 17 policy fields of legislative and administrative dimension and then create a scale for measuring each area. 1 = exclusively federal government; 2 = almost exclusively federal government; 3 = predominantly federal government; 4 = equally federal and provincial governments; 5 = predominantly provincial governments; 6 = almost exclusively provincial governments; 7 = exclusively provincial governments of 17 categories only. We then give them a confidence rating: *low, **medium, ***high, and no star for equally federal and provincial.

The constitution institutionally decentralizes the federation of Pakistan. It has three governmental layers: federal, provincial, and local. Each layer of the executive government is elected by a ballot voting system. Moreover, the federal government is legislatively predominant at the national level, as shown in for all policy fields. Eight policy fields are exclusively, almost exclusively, and predominantly controlled by the federal government, and three areas are equally controlled by federal and provincial governments. At the same time, the remaining six policy fields rely on the domain of provincial governments.

Table 2. Policy statistics of de/centralization in 2019

In contrast, the provincial governments are predominantly responsible for administration. The eight policy fields are controlled by provincial governments exclusively, almost exclusively, and predominantly. Enumerating the federal level’s legislative and administrative management is dominant in the legislative policy field, and provincial governments remain stronger in administrative areas. The differences in legislative power distribution across policy fields are pronounced, as indicated by a centralized structure. For half of the 17 policy fields analyzed, the federal government through the national assembly had exclusive, almost exclusive, and predominant control over lawmaking.

The federal government’s administrative privileges comprised the typical subnational domains of culture, education and law enforcement, and natural resources. More importantly, the federal government monopolized or almost monopolized legislative power in eight policy fields. Only in two areas did the federal government implement most of its policies, namely, external affairs and currency and money supply. The lower dominancy in the administrative side across policy fields underlines that administrative powers are consistently attributed to the provincial government.

Confidence rating: *low, **medium, ***high, and no star for equally federal and provincial.

4. Fiscal centralization

According to the federal legislative list, the federal government holds most of the revenue powers in the fourth schedule in the constitution. It collects massive amounts of tax and non-tax revenue. displays the measuring formula of the federal government’s share of income and taxation; it indicates that the degree of fiscal centralization is high in Pakistan. The degree of fiscal centralization can be measured by the percentage shares of subnational government expenditure and revenue in the total government expenditure and revenue: the lower the share, the more centralized the State (Arzaghi & Vernon Henderson, Citation2005; Cevik, Citation2016; Morozov, Citation2016). Pakistan’s fiscal system is highly centralized: the federal government and all provincial governments collectively contributed to revenue receipts and recorded 91.3% and 8.7% of the total government revenue, respectively, in FY 2019. The federal government collects 90.9% of the taxation side, while provinces constituted 9.1% of the total government taxes in FY 2019. A significant share of subnational government expenditures is the reliance on federal transfers recorded by 84.7% in FY 2019. However, on the expenditure side, the federal government spent 63.1% of the total government expenditures. In comparison, the provincial governments spent 36.9%, including the larger portion of federal transfers. Therefore, this indicates the four-dimensional centralization from the perspective of fiscal centralization. See for more details on fiscal indicators.

Table 3. Fiscal (de)centralization measurement dimension and indicators

After applying the (de)centralization measurement model, we conclude that Pakistan has a centralized fiscal system from expenditure, revenue, taxation, and transfers. At the same time, the details of indicators and dimensions are described, respectively, in subsections.

4.1. Static for measures fiscal (de)centralization

The federal and provincial governments also had limited fiscal autonomy, as demonstrated by a mean score of 4.8 (). The local governments could set the rates for taxes on local businesses and real estate. While the federal government had its sources of tax revenues, these sources could collectively co-decide with the federal government and its majority in the national assembly on all other major tax laws through the parliament. Conditional grants by the federal government played only a minor role in land finances and had relatively strong strings attached. Finally, the provincial governments were not fully autonomous in borrowing.

Table 4. Measuring indicators of fiscal de/centralization

Fiscal autonomy is divided into five sub-dimensions. The first degree of public revenue of own resources is directly controlled by provincial governments, which can be defined as the proportion of own public revenues out of total government revenue resources. The higher the proportion of provincial own revenue sources, the greater the fiscal autonomy of the provincial government. Thus, we measure it based on a 7-point scale in percentage, 1 = 0–14 high centralized; 2 = 15–29 centralized; 3 = 30–44 quite centralized; 4 = 45–59 medium; 5 = 60–74 quite decentralized; 6 = 75–89 decentralized; 7 = 90–100 high decentralized (Dardanelli, Kincaid, Fenna, Kaiser, Lecours, Singh et al., Citation2019). The scale is based on equivalent intervals but at the top to capture the better distribution variation at the top end.

The second and third dimensions relate to expenditure and tax autonomy; therefore, we measure these dimensions. The higher the percentage at a provincial level is, the greater the fiscal independence. The fourth indicator, federal transfer, concerns the sphere based on federal transfers’ percentage share in regional own revenue resources. Therefore, the more limited the sphere of federal transfers, the more autonomous the provincial governments are in allocating the federal government’s funds. If a sphere of federal transfer is significant, it means higher centralization. We measure it as a percentage share of federal transfers in provincial revenue. The fifth dimension is related to autonomy in borrowings; a provincial government can increase its spending via borrowings. However, greater autonomy in borrowings specifies higher fiscal decentralization. We measure this indicator using the above scale.

4.1.1. Measuring dimension

The property of direction change is shifting over the measure from the highest to lowest value, indicating a reduction in the provincial governments’ fiscal autonomy and centralization. Variable changes entailing the shift from the lowest to highest value specify an increase in the provincial government’s fiscal autonomy and denotes decentralization. Morozov (Citation2016) and Schneider (Citation2003a) measure the fiscal degree of (de)centralization of an economy. The higher the percentage shares of subnational government’s expenditure and revenue, the more elevated the (de)centralization in the State.

The fiscal centralization section’s conclusion has determined that Pakistan has a centralized fiscal framework on the prospective expenditure side. The federal government controlled 77.1% of spending. After the 18th amendment, the provincial government spending ratio increased, recording 37.3% in FY 2019. The federal government has collected an average of 89% of total government revenue over the last 39 years. The power over tax collections rose simultaneously to 89.1% in FY 2017–2018. Increased centralization of revenue also raises the importance of transfer payments; however, the federal and provincial governments’ share was calculated under the 7th NFC Ward.

5. The interest groups

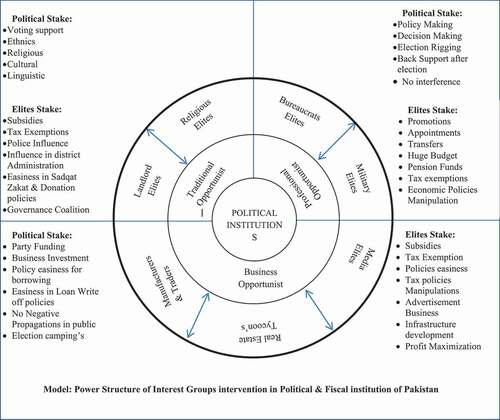

In this section, we will introduce the important interest groups in Pakistan. Interest groups gain their political influence in different ways and also pursue different goals. We have classified all elites into three main interest groups. Traditional opportunists comprise landlords and religious elites, professional opportunists comprise military and bureaucrats elites, and business opportunists comprise manufacturers and traders and media and real estate tycoons.

In Pakistan, the traditional opportunists have a very close consensus during elections. They agree that there will be no infighting, no speeches, and no opposition as they are attributable to massive losses in fair elections (Dawn, Citation2014). Different economic benefits are realized after winning an election. The professional opportunists, in contrast, have been running the country for the last six decades; the resulting military has governed the country for more than 30 years and has progressively consolidated control over the political-institutional process. However, at the same time, bureaucracy intentionally takes the cover of feudal and military elites and obtains appointments, transfers, and promotions in relevant and lucrative departments. The main posts are filled through elites’ nepotism, and individuals are inadequately qualified (Ahmad et al., Citation2014). Although business opportunists fund the political parties during elections, they demand various economic and fiscal policies in response. In Pakistan, the political and fiscal institutions are inversely under the control of interest groups. These groups are functioning for their family, personal, and party interests, not for general public development and growth (Ahmad et al., Citation2014). This dependency is due to the weak political structure of Pakistan (Kennedy, Citation1988).

Governmental, semi-governmental, and private organizations cannot work without the pressure and influence of interest groups. The elite is viewed balefully in a multi-class-oriented society like Pakistan. The power structure is also relatively pluralistic, with no single elite maintaining supreme control in the country. The colonialism, ethnic heterogeneity, industrialization, Islamism, and historical precedents all contributed to the evolution of several competing elites, making it impossible for a single group to absolutely control the political power grid. The political power structure in Pakistan is described in terms of the model below. The power translates into action and exchange within an integrated system or interest groups existing together. It is a structure primarily concerned with the circulation of sovereignty within its boundaries. The model below explains the political and fiscal stakes of interest groups and politicians .

Figure 1. Power structure of interest groups intervention in political & fiscal institutions of Pakistan

The Landlord Elites: The citizens who hold a massive amount of agricultural property and lease their forms to other people are called landlords (LaPorte, Citation1975). In Pakistan, since its inception, land distribution is skewed toward 5% of the landlord who owns almost 64% of the aggregate farmland, whereas small farmers, constituting around 65%, still hold a meager 15% land (Dawn, Citation2006). Baker (Citation2008) explains that the feudal is the elites of the elite in Pakistan. They have cronies in every community. They know very well who is favoring whom. If they lose in any polling during the election, they can figure out via this system and take revenge through fabricated police cases or low crop prices, which the feudal lords own. They spent their entire lives following the feudal system. After winning elections, Saleem (Citation2010) writes, the landlord intends to interpret the political influence as favorable economic policies. They are enjoying the income tax exemption and tax amnesty schemes through various policies. It was reckoned that around Rs 550 billion has been provided in the form of duty exemption and the cost of tax (Khan, Citation2018). The landlord-turned-politicians of rural areas get district police officers or station house officers of choice posted to increase their authority in the constituency with political influence (Dawn, Citation2009).

The Religious Elites: The concept of ‘Political Islam’ was coined by Akhtar et al. (Citation2006), who defined it as the framework of political ideas and Islamic practices that came into being and later evolved from the power struggle. Religious elites are running religious institutions known as Madressah. It attracts a tremendous amount of charity, Sadqat, and zakat according to its size; indeed, thousands of Madressah in the country are only used for fundraising. The religious elites exploit them as their political constituency and source of strength and power (Rana, Citation2015). However, despite the vital role of religious elites, especially in weak institutional contexts, there is limited research on them (Hertz & Imber, Citation1995).

The Military Elites: Military elites identify as the top-level military personal, based on Colonel through general ranks, with an emphasis on seniority in position, and principally belong to the army, air force, and navy (Rizvi, Citation2018). Internal problems of ethnic and language conflicts between the Punjabi, Balochi, Sindhi, Muhajir, and Pashtuns are still prevalent in the country. The reliance on military forces created a mindset about military strength in the country that believed the military is the only choice & rescuers who have the capacity & power to save the country from any challenge. The army can run the government in place of democratically elected politicians. Pakistan’s Military Generals always have an active role to play in the country’s domestic and foreign affairs even during the civilian rule” (Waqar, Citation2012). The military coups have takeover four times over the civilian government; Marshall was imposed on the country for more than 30 years in the last 72 years. It drives the military strongest and makes it powerful in the country. Legal and constitutional changes were introduced after the second army rule, which further strengthened the military’s political power and gave it maximum autonomy, which would empower the military's overall political stakeholders, and Article 58(2)(b) in the constitution protects the military's core interest (Siddiqa, Citation2007). Warlords are also the dominant economic players in the country, and all their business ventures are registered under the welfare foundations. Business is very diverse, such as education, health, commercial banks, insurance companies, fertilizer, cement, steel, foods, land, TV channels, etc. They enjoy tax exemption, avoidance, and enjoy the Milbus amount (Siddiqa, Citation2007).

The Bureaucrat Elites: Bureaucracy means the assemblage of bureaucrats, who include all government servants, except those who are popularly elected” (Khan, Citation2006). According to Kalia (Citation2013), a country’s bureaucracy is responsible for policies, maintaining political order, upholding the rule of law, and promoting economic development. Kardar (Citation2014) explains that, during elections, senior and mid-tier bureaucrats can play an essential role in elections. At the district level, the police can deploy to harass and intimidate opposition candidates and voters. Simultaneously, commissioners can use powers to refuse and delay permission for rallies to less preferring politicians. The bureaucrats grab the loyalty of winning politicians, deploying on good posting, quick promotions, and restricting their transfers. Political back support provides a lavish lifestyle to bureaucrats. The gifts of plots, licenses for friends & supporters, corruption easiness, monopolistic profiteering, resistance to the tax net’s widening, and transferring funds abroad are the vital examples (Kardar, Citation2014).

Business Opportunist/Elites: Business elites are defined as those who influence large companies’ policies and decisions through the positions they hold (Useem, Citation1980). Business elites have shared concerns and objectives on the levy on taxes and economic programs (Ahmed, Citation2017). Family firms in Pakistan are an effective form of business. The findings of Saeed et al. (Citation2014) in their studies conclude that business groups and politicians influence the business world and that it is a common practice in Pakistan to use political connections by business groups. Additionally, Dawn (Citation2017), concerning that some business elites were funding many protests and anti-government rallies, held by the prevailing government party, they often saw standing beside the current prime minister. One of the contemporary examples is the Pakistan government that issued a presidential order to waive over RS 300 billion worth of liabilities, which goes into the business elite’s account (Rana, Citation2019).

Media Elites are also considered a business elite group, including media houses and other owners, journalists, TV talk shows, print media journalists, and columnists (Ahmed, Citation2017). BBC (Citation2013) shows that marginal political actors advanced their interest through media to meet their electoral goals. Media elites are the only close to monopoly power in the country that influences public opinion and influences the policy-making process. They target a political party and dent its image in front of the public (Ahmed, Citation2017). Naseer (Citation2010) explains that criticizing government policies is a way for the media elite to generate revenues for their businesses in the form of advertising revenue, licenses, and tax reliefs. Tax breaks, concessions, privileges, and incentives cause billions of revenue losses to the tune of Rs 700 to Rs 800 billion per annum under the Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO) 1125 (I)/2011. It provides a protective shield of tax exemptions on industries, traders, media, etc. (Haider, Citation2019).

In Pakistan, politicians, civil-military bureaucracy, and real estate tycoons controlled the real estate market. Most real estate tycoons and other business people have belonged to mainstream parties such as PML-N, PTI, and PPP. They support their political parties with funding to enhance their vote bank during elections (Tribune, Citation2018). In the feedback, they demand the amnesty scheme to bring its undeclared income under documentation. The June 2019 amnesty scheme is the right example to facilitate the real estate tycoons and other business elites (Haider, Citation2019). Due to the close relations between real estate giants and politicians in government, they have to enjoy the narrow tax rates and extensive tax exemptions in the real estate sector (Rehman, Citation2019). Malik (Citation2018) explains that a military-based real estate developer known as defense housing authority (DHA) usually avoids capital gain taxes. The interest groups within the business community in Pakistan not only fund the political parties for election or even senators, but also directly contest in the polls in a personal capacity, and cater to the business elites’ combined interests (NIPA, Citation2006).

6. Consequences and outcomes of a political decentralized and fiscally centralized system

This section attempts to analyze and describe the implications and results of Pakistan’s two inverse institutions: politically decentralized and fiscally centralized. Why is the federal government reluctant to promote fiscal decentralization? How did this asymmetric system come to be? We will provide explanations based on evidence and explain the perspective of political landscape and culture, intervention of interest groups, and public debts.

6.1. Political landscape and culture

Historically, the process of political decentralization in Pakistan can be summarized as one where the federal government gradually lost its political authority after several coups. Moreover, party competition in provincial elections is mostly reduced by cultural affiliation between voters and parties. As each province has a dominant culture, the political landscape is relatively stable because certain parties control each provincial government for a long time.

After independence, the ethnic, language, and cultural conflicts remained as problems, and military forces were the sole option for the civilian government to maintain law and order. Heavy reliance on the military reinforced the political influence of military groups, which laid the groundwork for the later coups.

As a cultural convention, religious groups, such as Shiah, Sunni, Brailvi, Deobandi, Qadiyani, and Ismaili,Footnote14 had significant influence over Pakistan’s socioeconomic life. The General Zia-ul-Haq regime witnessed this massive Islamization when the religious groups developing as major political parties, particularly Jamiat Islam, emerged as active political players (Shoukat et al., Citation2017).

However, a culture defined by those expected principles and values of the ethnic, religious, and social groups remains relatively unchanged from generation to generation. It is quite challenging to understand and scrutinize the country’s political culture because of a mixed and confusing set of rules. In the past decade, sociopolitical experts have studied the political alteration response to questions concerning various political groups. Who crafts different political cultures in countries parallel in population size, economic growth level, class structures, ethnic appearances, and religious and other cultural values? The political parties are culturally engaged and generate the country’s political uncertainty, and the politicians have gained sympathy in the different shades of democratic costumes. Therefore, all regions’ cultural diversity played a vital role. Every part supports its culture-based political parties during elections, e.g., Punjab’s political parties supported by Punjabi, Sindh by Sindhi, KP by Pashtuns, and Balochistan by Baloch. The cultural masses and interest groups are primary reasons influencing whether the public will see their parties in power during elections and have control over the political institutions.

However, elites’ symmetric dominant behavior and cultural norms assert the country’s decentralization process, attempted three times during military coops, making military elites more influential and significant players in elections. In 2010, after the 18th amendment under Art: 140-A (1), a democratic government emphasized to provincial governments to establish the local government system and make it legitimate under the provincial local government acts. illustrates the cultural effect of political parties in the country.

Table 5. Political parties’ governance and cultural effect in Pakistan from 1972 to 2018

explains that each political party has a strong concern with its culture during elections. Pakistan People Party (PPP) belongs to Sindh province; it has governed the province six times, and landlords hugely influence the party. Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) belongs to Punjab and has served in the region three times. Some other cultural and religious parties are most dominant and supported by brotherism and are caste-based. Simultaneously, the PK government mostly relies on religious, linguistic, and party coalitions. While culture is heavily interfering in Balochistan areas, Baloch political parties are primarily dominant during elections or coalition governments.

6.2. The intervention of interest groups

The intervention of interest groups played a crucial role in shaping the asymmetric fiscal and political institutions in Pakistan. The asymmetric institutional structure divides the interest groups into two broad categories: direct and indirect elites. Hence, political institutions are directly influenced by the landholding, religious, and bureaucratic elites to support the politicians during the election for maximum voting gain. Some elites, such as in military, business, and media, are indirectly interfering in the voting process to support their political party through election riggings, party funding, and media campaigns. The compatibility among politicians and elites makes interest groups more potent in substitute; they attempt to manipulate the fiscal and economic policies favoring this harmony, molding the fiscal institutions centralized in the country.

After independence, the country’s governance system was intensely dominated by the colonial tendencies to centralize control. The State’s political landscape is traditionally based on feudal elites, religious clergy, military, bureaucrats, businesspeople, and media elites. The transgression of the army and civil dictator regime, supported by self-controlled feudal classes and endorsed by the religious clergy, has caused the country’s fragmentation of political culture. However, in rural areas, caste, cultural, and BaradrismFootnote22 systems play into the hands of feudal elites, who suitably use them for their own benefit. Some elites directly influence the cultural norms and divide voting arrangements into Brotherism, religious, ethnic, language, and illiteracy bases. Therefore, landlords play a dynamic role in individuals’ and groups’ decisions during elections and are highly affiliated with the voting pattern in Sindh and Baluchistan’s rural areas. In Punjab, caste and brotherism function effectively in voting support for political actors. In KP, most people choose their leaders/representatives through the prism of religion and tribal affiliation.

The bureaucratic elites play an influential role in supporting their favorite politicians over others during elections at the district levels. Opposition candidates and voters are harassed and intimidated during elections by deployed preferred police officers. For example, some other bureaucrats can use powers to refuse or delay rallies to favor politicians less. Meanwhile, bureaucrats seize winning politicians’ loyalty and deploy on good postings, quick promotions, and restricted transfers (Kardar, Citation2014). This politicization process makes the bureaucracy dependent on them for good appointments, early promotions, and transfer restrictions (Wilder, Citation2010). In this way, political actors eliminate bureaucrats’ compulsion and use them for corruption whereas the business opportunist provides massive funding to political parties during the election. Dawn (Citation2017) states that elites were funding many protests and anti-government rallies held by the prevailing government party, during which some elites were often seen standing beside the current prime minister. In place of party funding and political support during the election, they quickly intervene in the country’s economic and other policies and manipulate it in their favor. Haider (Citation2019) describes that the elites have received all kinds of tax breaks, concessions, privileges, and incentives in Pakistan, which causes billions in revenue loss per annum. Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO) 1125 (I)/2011 provides a protective shield of tax exemptions for industries, traders, media, and so on.

6.3. In terms of public debts

The influence of elites and culture has driven political institutions to be decentralized and weak. In contrast, interest groups’ intervention forcefully pushes the financial institution to centralize and restrict it at the federal level. The politically weak institution left a corruption gap while centralized fiscal institutions resist decentralized taxation and insist on their conservative taxation system. The general layout of FFT describes the functions of fiscal assignment to multiple government layers which carried out these fiscal instruments appropriately (e.g., Oates, Citation1972; Richard et al., Citation1959. However, Pakistan has an institutional imbalance structure where the provincial government spending at the cost of federal revenue makes the spending inefficient, leading to corruption and ineffective subsidies and conventional centralized taxation structure escalation of the public debts at an uncontrolled level.

Some macroeconomic variables also inversely affect and cause national liability at a dangerous level. The delayed development projects, rising interest payments on mortgage and defense expenditures, growing current expenditures, and massive subsidies are the best examples. This section mostly focuses on corruption and the centralized taxation system. How do corruption and a conservative taxation system contribute to public debts? While macroeconomic factors are recommended for future research, they help to understand the different critical clues.

Corruption: Pakistan has been a distressed and nontransparent state for years, providing room for bribery and corruption (TIP, Citation2018). The greed of good postings, promotions, and transfers force the bureaucracy to bow to politicians. These bureaucrats work with politicians on mutual understanding, and manipulate policies and provide loopholes to politicians for corruption. In this way, political actors get rid of the direction of bureaucrats and use them for fraud. According to the (GCR, Citation2018) report, Pakistan’s public sector is at high risk for corruption. Unproductive bureaucracy, lower public officials, and a growing ratio of uneducated politicians are working together and involved in bribery levels. Corruption is spread deeply in institutional backbones. There is proof that favoritism in transfers of individual bureaucrats from the federal to subnational governments encourages corruption in institutions (ICS, Citation2017).Footnote23 Lack of institutional accountability, punishment, and penalties in the law kills merit in appointments, transfers, and promotions. Limited salary packages and low benefits also engage government officials in corruption (GCR, Citation2018). According to TICPI (Citation2018) transparency international, Pakistan is 117 on a list of least corrupted countries worldwide among 180 countries and 33 out of 100. One recent example of corruption is that of a real estate tycoon who settled the corruption probe and paid $248 million to the Pakistan government (Al Jazeera, Citation2019). The country’s anti-corruption transparency framework of the right to information has suffered and needs transformation. However, the law and implementation are inferior; operationalizing public officials is limited. Lack of public awareness of the law fails to hold the government accountable (TIP, Citation2018).

The parliament passed an anti-corruption bill known as the Public Interest Disclosure Bill in August 2017; the law gives whistle-blowing securities protection to politicians. Simultaneously, anti-corruption institutional deficiencies in authorities, finance, and staff capacity enfeeble the institution. Meanwhile, the punishment for corruption by a 14-year imprisonment is fair. The minimum sentence generates interests tied with those (local) elites who are willing and capable to participate in bribery.

Conservative Taxation System: Pakistan falls in the lowest categories of tax-to-GDP ratio ranking countries based on tax revenue collection estimated at 12.9% in the 2018 budget for Pakistan. This low status is due to inadequate tax revenue decentralization efforts by the federal government and leaves the system centralized. Some other reasons include:

Inefficient Tax Management (weaker administration, unskilled human resources, inadequate technical supporting systems, excessive freedom to an employee for the decision-making process in any situation, and rent-seeking behavior).

Limited tax circle: Pakistan has 207.7 million people; less than 0.5% of them are taxpayers. In the group of 39.4 million employed persons, less than 2.62% are listed as active taxpayers.

Conservative tax disbursement arrangement: 64.1% of tax revenue comes from indirect taxes (Sales Tax, Federal Excise Duty, and Customs Duty).

Complex and less-transparent taxation system.

Tax evasion and bribery (low retribution to tax collection officials, which creates a large informal sector in the country).

Corrupt political environment: A lack of tax reforms and favoritism in bureaucrats’ deployment cause the manipulation in tax policies to favor influential fund donors of political parties and other interest groups.

These issues constitute a marriage of convenience between the government and politically supported fragments of the populace. They create a domain in which tax policy is planned and tax administration is equipped to allow tax exemptions and concessions for interest groups, mostly for mutual benefits. The government is compelled to maintain assessment concessions on taxes to support more prosperous interest groups for parties based on future election fund support. On the other side, the wealthy and potent business people utilize their political influence and resources to get these concessions instead of offering help to the governing party. The recent political polarization movement has exacerbated this symbiosis. Haider (Citation2019) explains that interest groups have obtained many tax breaks, concessions, privileges, and incentives, causing revenue loss to the tune of Rs 700 to Rs 800 billion per annum under the different SROs, which are responsible for the protective shield of tax exemptions.

However, due to institutional asymmetry and the influence from interest groups, the government is inefficient on both expenditure and revenue sides at the cost of long-term national interest. Ultimately, Pakistan faces various challenges such as inefficiency, which leads to a large number of fiscal deficits and public debts. The trend of public debts is mainly on based (i) economic and security issues; (ii) the uncomplimentary situation of supporting a budget deficit suspended by loan financing supporters for a considerable period; and (iii) minimal borrowing from the central bank for the budget. However, these trends levy a massive loss on the economy. Subsequently, public debts rose continuously. The composition of federal liabilities must be critically analyzed and discussed, not only the fiscal impacts indicators, but also the confusion about the international debts and adverse effects of the political economy on debt reforms. The country’s public debt touched the highest level in history and recorded 37.7 trillion (97.9% to GDP) in 2019–20,Footnote24 crossing the limit of the FRDL Act 2005, which is 60% of the GDP. A large portion of these debts depended on domestic borrowings. It carried a tremendous interest rate, reaching 13.74% in September 2019Footnote25; the share recorded 58.6% of total liabilities while foreign debt stood at 41.4%Footnote26

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we have concluded that Pakistan has a decentralized political structure and a centralized fiscal system. Interest groups are the leading players in tailoring this asymmetry. The implication of interest groups and cultural masses shapes the political structure weak and decentralized. It generates clues for policy-makers (bureaucrats) and politicians for manipulating the policies in favor of elites. This compatibility between politicians and policy-makers creates loopholes for corruption, restricting the taxation system at the federal level and marking the fiscal institutions centralized.

Further, we conclude that growing public debts, rising fiscal deficit, corruption, and massive subsidies, leave the taxation system conservative and centralized. It makes the situation worse for the country, which impacts the financial system harshly and increases public debts on an uncertain level, which is another reason for fiscal centralization. The conservative taxation system and unnecessary promotions and transfers are politicians’ compulsions because they desire to support the preferred masses. In the contradiction, they get kickbacks of party funding, and voting helps during the elections.

In this research, we recommend and suggest that before reforming the fiscal system, the federal government must first improve the political institutions’ performance. Therefore, the federal government needs to educate the public. Simultaneously, it reduces the compatibility between the politicians and interest groups, which hurt political and fiscal institutions’ autonomy and generates loopholes for corruption. The legislative institutions must pass a unified law, which brings political and fiscal institutions, including interest groups, accountable in front of the public and reduces the harmony between elites and politicians.

The government must be decentralized in the financial institution and shift the powers to elected politicians, in the form of revenue and spending autonomy in their jurisdiction, for quick and efficient public services to maximize social welfare.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fayaz Hussain Tunio

Dr. Fayaz Hussain Tunio did his Ph.D. in Public Finance from the Central University of Finance and Economics. His research focused on the Asymmetric Political and Intergovernmental Fiscal system: Neo-Public Finance theory’s perspective. Specifically, his research work is based on the evolution of FFT and Neo-Public Finance Theory. How does the intergovernmental structure work within different approaches? He has an extensive expertise in intergovernmental relations, public policy, government tax management, and financial management.

Prof. Dr. Agha Amad Nabi has broad experience in finance, and he has published around 39 articles in SSCI, SCI, ESCI, Scopus, and Web of Science. His current research interest includes fiscal federalism, fiscal decentralization, intergovernmental relations, financial development, environmental quality, debts, and financial crises. He is a well-renowned researcher in the field of finance; see his profile on google scholar

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=5ltATsoAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

Agha Amad Nabi

Dr. Fayaz Hussain Tunio did his Ph.D. in Public Finance from the Central University of Finance and Economics. His research focused on the Asymmetric Political and Intergovernmental Fiscal system: Neo-Public Finance theory’s perspective. Specifically, his research work is based on the evolution of FFT and Neo-Public Finance Theory. How does the intergovernmental structure work within different approaches? He has an extensive expertise in intergovernmental relations, public policy, government tax management, and financial management.

Prof. Dr. Agha Amad Nabi has broad experience in finance, and he has published around 39 articles in SSCI, SCI, ESCI, Scopus, and Web of Science. His current research interest includes fiscal federalism, fiscal decentralization, intergovernmental relations, financial development, environmental quality, debts, and financial crises. He is a well-renowned researcher in the field of finance; see his profile on google scholar

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=5ltATsoAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

Notes

1. The Federal Government Subject to the constitution Art-90 (1) “the executive authority of the federation shall be exercised in the name of President by the Federal Government, consisting of the Prime Minister and Federal Ministries, which shall act through the Prime Minister, who shall be the chief executive of the federation”. Second tier, The Provincial government protected under the constitution of Pakistan, Art-129 (1) “The Provincial Government: subject to the constitution, the executive authority of the province shall be exercised in the name of the Governor by the Provincial Government, consisting of Chief Minister and Provincial Ministries, which shall act through the Chief Minister”. Third level is local government. In this level federation gives powers to provincial governments constitutionally for organizing the local body according to Art-140 (1) each province shall, by law, established a local government system and devolve the political, administrative and financial responsibilities and authorities to the elected representatives of the local government.

2. Constitution of Pakistan, and local government acts of respective provinces.

3. Economic Survey of Pakistan FY 2019.

4. Economic Survey of Pakistan 2018–19, actual tax collection 12.9% of GDP was recorded in FY 2018.

5. Pakistan Economic Survey 2017–18, page 50, calculated by author 5.8 × 100/17.2 = 33.7.

6. Pakistan Budget in brief 2019–20 and budget statement of Pakistan 2019–20, calculated by author.

7. Budget in Brief Calculated by Author, on federal government revenue after provincial divisible pool amount.

8. Constitution of Pakistan, Chapter-3 Tribal Areas, Article 246, Clause (C) & 4 (D) On the commencement of Constitution (25th amendment) Act, 2018, Area mentioned in Paragraph (b)—(ii) paragraph (c), shall be merged in the province KP.

9. 25th Amendment in constitution of Pakistan: Dated: 31 May 2018.

10. Subject to the constitution, the executive authority of the federation shall be exercised in the name of the president by the federal government, consisting of the prime minister and the federal ministries, which shall act through the prime minister, who shall be chief executive of the federation.

11. Subject to the constitution, the executive authority of the province shall be exercised in the name of governor by the provincial government, consisting of the chief minister and the provincial ministries, which shall act through the chief minister.

12. Each province shall, by law, establish a local government system and devolve political, administrative, and financial responsibility and authority to the elected representatives of the local governments.

13. Article 41 constitution of Pakistan.

14. Shiah, Sunni, Brailvi, Deobandi, Qadiyani, and Ismaili are well-known religious organization in Pakistan.

15. It shows the affiliation of Head of the Political party with different cultures like: Sindhi, Punjabi, Pashtuns, Baloch, Religious.

16. Sindhi: It represents the culture of Sindh people in Sindh province.

17. Punjabi: It represents the culture of Punjabi people in Punjab province.

18. Pashtun: It represents the culture of Pashtun in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

19. Religious: It represents the religious affiliation in different provinces.

20. P& P known as Punjabi & Pashtuns.

21. Baloch: It represents the culture of Balochi peoples in Balochistan province.

22. People follow the head of a related caste.

23. U.S. Department of State: Bureau of Economics and Business Affairs; Investment Climate Statement for 2017 (ICS) https://www.state.gov.

24. Debts and liabilities: State Bank of Pakistan.

25. Data source: State Bank of Pakistan as per structure of interest rate schedule—I.

26. Data source: State Bank of Pakistan.

References

- Ahmad, R. E., Eijaz, A., & Rahman, B. H. (2014). Political institutions, growth and development in Pakistan (2008–2013). Journal of Political Studies, 21(2), 257.

- Ahmed, M. A. (2017). Pakistan: State autonomy, extraction, and elite capture—A theoretical configuration. The Pakistan Development Review, 56(2), 127–21. https://doi.org/10.30541/v56i2pp.127-162

- Akhtar, A. S., Amirali, A., & Raza, M. A. (2006). Reading between the lines: The Mullah – Military alliance in Pakistan. Contemporary South Asia, 15(4), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584930701329982

- Al Jazeera. 2019. Pakistan tycoon hands over $248 million to settle UK corruption probe. Al Jazeera News, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/12/pakistan-tycoon-hands-244m-settle-uk-corruption-probe-191204065641192.html.

- Arzaghi, M., & Vernon Henderson, J. (2005). Why countries are fiscally decentralizing. Journal of Public Economics, 89(7), 1157–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.10.009

- Bahl, R. (1999). Implementation rules for fiscal decentralization. International Studies Program, school of public studies, Georgia university Atlanta, Working Paper 99-1.

- Baker, A. 2008. Landowner power in Pakistan election. Published in Daily Times, 2008. http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1712917,00.html.

- BBC. 2013. “Media action policy briefing #9.” BBC.

- Brancati, D. (2006). Decentralization: Fueling the fire or dampening the flames of ethnic conflict and secessionism? International Organization, 60(3), 651-685. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081830606019X

- Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. M. (1980). The power to tax: Analytic foundations of a fiscal constitution. Cambridge University Press.

- Bryce, J. 1901. Studies in history and jurisprudence, vol. 1 - online library of liberty. 1901. https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/bryce-studies-in-history-and-jurisprudence-vol-1.

- Callard, K. (1957). Pakistan: A poltical study. In Pakistan - A political study. Government: George Allen and Unwin, London. (pp. 350–355).

- Cevik, S. (2016). Unlocking Pakistan’s revenue potential. 22. IMF WP/16/182

- Chari, R., Hogan, J., & Murphy, G. (2010). Regulating lobbying: A global comparison. Manchester University Press.

- Cheema, A., Khwaja, A. I., & Qadir, A. (2005). Decentralization in Pakistan: Context, content and causes. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.739712

- Collins, R. (2011). International organisations and the idea of autonomy: Institutional independence in the international legal order. In R. Collins & N. D. White (Eds.), Modernist-positivism and the problem of institutional autonomy in international law. 40-65. Routledge.

- Corry, J. A. (1941). The federal dilemma. The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science/Revue Canadienne d’Economique Et De Science Politique, 7(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.2307/137114

- CpiTI CPI. 2018. Corruption perception index 2018. Transparency international. https://www.transparency.org/cpi2018.

- Cyan, M., & Bahl, R. (2011). Tax assignment: Does the practice match the theory? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2011, 29, 264280.

- Dardanelli, P., Kincaid, J., Fenna, A., Kaiser, A., Lecours, A., & Singh, A. K. (2019). Conceptualizing, measuring, and theorizing dynamic de/centralization in federations. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 49(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjy036

- Dardanelli, P., Kincaid, J., Fenna, A., Kaiser, A., Lecours, A., Singh, A. K., Mueller, S., & Vogel, S. (2019). Dynamic de/centralization in federations: Comparative conclusions. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 49(1), 194–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjy037

- Dardanelli, P., & Mueller, S. (2019). Dynamic d(e/centralization in Switzerland, 1848–2010. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 49(1), 138–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjx056

- Dawn. 2006. Governance is weakest link. DAWN.COM. Dawn Newspaper. January 30, 2006. http://www.dawn.com/news/176449.

- Dawn. 2009. Revamping the police structure. Dawn New Paper, 2009. https://www.dawn.com/news/841196.

- Dawn. 2014. Feudals unite in Sindh. DAWN.COM. Dawn Newspaper. January 7, 2014. http://www.dawn.com/news/1078818.

- Dawn. 2017. Jahangir Tareen one of the Pakistan’s healthiest lawmaker; Published in Dawn Newspaper, Dec 15th, 2017. Dawn New Paper, December 15, 2017.

- Dür, A., & De Bièvre, D. (2007). The question of interest group influence. Journal of Public Policy, 27(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X07000591

- Ebel, R. D., & Yilmaz, S. 2002. On the measurement and impact of fiscal decentralization. Policy Research Working Papers. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-2809.

- Falleti, T. G. (2005). A sequential theory of decentralization: Latin American cases in comparative perspective. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051695

- Fisher, M. H. (2000). Pakistan: A modern history. By Ian Talbot. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998. Xvi, 432 Pp. $35.00 (Cloth). The Journal of Asian Studies, 59(3), 787–788. https://doi.org/10.2307/2659005

- Fox, J., & Aranda, J. (1996). Decentralization and rural development in Mexico Community Participation in Oaxaca’s municipal funds program. Center for US-Mexican Studies. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.5160.0960

- Garrett, G., & Rodden, J. (2000, April) Globalization and decentralization. Annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

- GCR. 2018. The global competitiveness report 201718; (GSR). World Economic Forum. http://reports.weforum.org/global-competitiveness-index-2017-2018/.

- Guibert, G., & Lanvin, B. (1984). Decentralization in government: The United States and France compared. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 3(2), 289. https://doi.org/10.2307/3323940

- Haider, M. 2019. IMF wants abolition of Rs 700 Bn tax exemptions. The News International, July 5, 2019.

- Hertz, R., & Imber, J. B. (1995). Studying elites using qualitative methods. Sage Publications.

- ICS. 2017. Bureau of economics and business affairs; investment climate statement for 2017. Investment climate statement US Department of State. USA Government. https://www.state.gov

- Jalal, A. (1995). Democracy and authoritarianism in South Asia (Vol. 50). Cambridge University Press 1995.

- Jordan, G., Halpin, D., & Maloney, W. (2004). Defining interests: Disambiguation and the need for new distinctions? The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 6(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2004.00134.x

- Kaiser, A., & Vogel, S. (2019). Dynamic de/centralization in Germany, 1949–2010. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 49(1), 84–111. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjx054

- Kalia, S. (2013). Bureaucratic policy making in Pakistan. 8(2), 156-170.

- Kardar, S. 2014. Elite living on borrowed time; former governor State Bank of Pakistan. Dawn New Paper, December 23, 2014.

- Kee, J. E. (2003). Fiscal decentralization: Theory as reform. 34. The George Washington University.

- Kennedy, C. H. (1988). Bureaucracy in Pakistan. Karachi: Oxford University Press.

- Khan, S. (2006). Public administration with special reference to Pakistan. Lahore.

- Khan, S. 2018. Government cuts development spending, increases taxes on country’s Elite. Dawn New Paper, September 18, 2018. https://www.dawn.com/news/1433668.

- Khurshid, K. (2011). A treatise on the civil service of Pakistan: The structural-functional history, 1601–2011. Sang-e-Meel Publications.

- Kincaid, J. (2019). Dynamic de/centralization in the United States, 1790–2010. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 49(1), 166–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjy032

- Klimovski, S., Karakamisheva-Jovanovska, T., & Spasenovski, D. A. (2016). Political parties and interest groups. In Konrad-adenauer stiftung in the republic of Macedonia “Iustinianus Primus” faculty of law in Skopje (pp. 636).

- LaPorte, R. (1975). Power and privilege: Influence and decision-making in Pakistan. University of California Press.

- Leacock, S. (1908). The limitations of federal government. In Proceedings of the American political science association (Vol. 5, pp. 37–52). JSTOR.

- Lecours, A. (2019). Dynamic de/centralization in Canada, 1867–2010. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 49(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjx046

- Levi, M., & Suddle, M. (1989). White-collar crime, shamelessness, and disintegration: The control of tax evasion in Pakistan. Journal of Law and Society, 16(4), 489. https://doi.org/10.2307/1410334

- Lyon, S. M. (2021). Power and patronage in Pakistan. Thesis, Durham University Library. 262.

- Malik, A. 2018. How not taxing the rich got Pakistan into another fiscal crisis. Al Jazeera News, October.

- Morozov, B. (2016). Decentralization: Operationalization and measurement model. International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior, 19(3), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-19-03-2016-B001

- Musgrave, R. A., & Peacock, A. T. (1958). Classics in the theory of public finance. London: MacMillan.

- Naseer, S. (2010). Regulation of electronic media and democracy in Pakistan. Journal of Political Studies, 2(17), 27–45.

- NIPA. 2006. Workshop on public policy analysis. Panel discussion presentation presented at the National Institute of Public Administration, Karachi, Pakistan. https://fp.brecorder.com/2006/02/20060227392030/.

- NRB. (2001). The SBNP local government ordinance 2001. National Reconstruction Bureau.

- Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal federalism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Oates, W. E. (2005). Toward a second-generation theory of fiscal federalism. International Tax and Public Finance, 12(4), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-005-1619-9

- OECD. 2001. Fiscal design across levels of government year 2000 surveys. Survey. Directorate for Financial, Fiscal and Enterprise Affairs Fiscal Affairs. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- OECD. 2002. Fiscal decentralisation in EU applicant states and selected EU member states. Report prepared for the workshop on “decentralisation: trends, perspective and issues at the threshold of EU enlargement.” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Olson, E. C. (1968). Dialectics in evolutionary studies. Evolution, 22(2), 426–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1968.tb05911.x

- Rana, M. A. 2015. “Madressah factor Https://Www.Dawn.Com/News/1165095.” Dawn New Paper, February 22, 2015. https://www.dawn.com/news/1165095.

- Rana, S. 2019. “PTI govt issues ordinance to waive over Rs300b GIDC dues.” The Express Tribune, August 30, 2019.

- Rehman, A. (2019). Real estate tax shelter. The Express Tribune. January 30, 2019.

- Reingewertz, Y. (2014). Fiscal decentralization - A survey of the empirical literature. SSRN Electronic Journal, MPRA Paper No. 59889. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2523335

- Richard, M., Musgrave, A., & Richard, A. (1959). The theory of public finance. In The theory of public finance (pp. XVII–628). McGraw-Hill Book Co.

- Rizvi, F. (2018). Circulation of elites in Pakistan’s politics. Orient Research Journal of Social Sciences, 3(1), 160–174.

- Rodden, J. (2003). Reviving leviathan: Fiscal federalism and the growth of government. International Organization, 57(4), 695–729. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303574021

- Rodden, J. (2004). Comparative federalism and decentralization: On meaning and measurement. Comparative Politics, 36(4), 481–500. https://doi.org/10.2307/4150172

- Rondinelli, D. A. (1983). Implementing decentralization programmes in Asia: A comparative analysis. Public Administration and Development, 3(3), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230030302

- Rondinelli, D. A., & Nellis, J. R. (1986). Assessing decentralization policies in developing Countries: The case for cautious optimism. Development Policy Review, 4(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.1986.tb00494.x

- Saeed, A., et. al. (2014). Political connections and leverage: Firmlevel evidence from Pakistan. Managerial and Decision Economics, 36(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2674.

- Saleem, S. 2010. “Military elites in Pakistan.” The Express Tribune, August 5th, 2010.

- Schneider, A. (2003a). Decentralization: Conceptualization and measurement. Studies in Comparative International Development, 38(3), 32–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686198

- Searle, B., & Ahmad, E. (2005). On the implementation of transfers to subnational governments. IMF Working Papers, 05(130), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451861495.001

- Shabbir, S. (2013). Does external debt affect economic growth: Evidence from developing countries. State Bank of Pakistan, Working Paper Series No: 63, 1-26.

- Shoukat, A., Gomez, E. T., & Cheong, K.-C. (2017). Power elites in Pakistan: Creation, contestations, continuity. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies, 54(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.22452/MJES.vol54no2.4

- Siddiqa, A. (2007). Military Inc: Inside Pakistan’s military economy. Ameena Saiyid Oxford University Press.

- Stegarescu, D. (2005). Public sector decentralisation: Measurement concepts and recent international trends*. Fiscal Studies, 26(3), 301–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2005.00014.x

- TIP. 2018. “Annual report on corruption awareness.” Karachi, Pakistan: Transparency international Pakistan. http://www.transparency.org.pk/documents/an2018.pdf.

- Treisman, D. (2002). Defining and measuring decentralization: A global perspective. Alexis De Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1 (1).

- Tribune. 2018. “Evolution of electables: How real estate developers replaced educated candidates.” The Express Tribune, July 23, 2018.

- Tunio, F. H., et al. (2020). Financial distress prediction using adaboost and bagging. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business (JAFEB), 8(1), 665–673. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no1.665