Abstract

The coronavirus is affecting almost every part of the world. The impact of the virus has worsened the difficulties already confronting residents of the fast-growing cities of the developing world already suffering from many challenges, such as inadequate housing, growing poverty, poor urban environmental management, and high levels of unemployment and underemployment. As authorities introduced restrictive measures to curb the spread of the virus, the low-income people appear to be affected by the measures more than the high-income groups. One of the interventions municipal and national leaders have introduced are limitations to movements, commonly known as lock downs. Together with these lock downs has been closures of spaces where low-income vendors and other informal traders operate. How are low-income urban residents being affected by these restrictive measures? Using field observations, newspaper reports and interviews with traders as well as key informants the article examines the changing typology of informal trade under the lockdown conditions. A key finding of the study is that under a restricted trading environment, the means for carrying bulky stock and a quick get-away is giving advantage to traders on wheels. Bringing wares to sites and traveling back home now requires own transport. The well-to-do traders are replacing poor vendors.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Street vending has been changing through time and spaces in various African countries, and in Zimbabwe, in particular. Traditionally, market stalls were installed in various cities in Zimbabwe with the vendors being made to be stationary and customers having to visit the stall to buy goods and wares displayed. Later, push carts were introduced by those who could move from one place to the other in search of customers. Today, the central business districts of many urban centres, the residential spaces, the recreational spaces and industrial spaces have many push carts, driven especially by male vendors. In more recent times, cars and trucks have emerged on the scene. Women have joined the ‘vendors on wheels’ revolution by being involved to, selling from the boots of their cars and vehicles. Such trends and developments are noteworthy for scholarship as they speak to the issue of livelihoods engagement and diversity of players on the urban landscape hence this article.

1. Introduction

In 2020 the world was afflicted by a viral attack. There was a new virus that affected the respiratory system as well as other critical organs, such as the lungs and the heart. Having first been discovered in China the virus quickly spread across the world. By mid-year 2020, the coronavirus had become a huge health and economic scare in sub-Saharan Africa. Although Zimbabwe only experienced the first infection and fatality in March 2020, by August the same year, the country had over 5000 confirmed cases (Ministry of Health, Citation2020). In line with measures that other countries took to curb the spread of the coronavirus, the government of Zimbabwe introduced a national lockdown. The term lockdown was used to refer to measures that restricted free movement of people to curb the spread of the virus. Initially there was a heavy restriction of people’s movements known as a total lockdown. This referred to a restricted stage where only permitted essential workers, such as those working in the food value chain, health, and utility workers had the right to leave their homes to go to work. The rest of the population was expected to stay indoors with minimum contacts with people that they did not live with.

Initially only formal food system suppliers, such as supermarkets and registered and licensed traders, were permitted to operate. Later on, informal food suppliers were also permitted if they operated in built-up or approved premises. This left informal sector vendors exposed as many of them operated from unregistered premises. This study sought to establish whether the effects of the lock downs had any impacts on food vendors. This was done by observing the streets and other areas where food vendors operated from. Site visits were conducted during that traders found on the sites were interviewed. The study also used secondary sources, such as academic and newspaper reports, that came out during the period. Comparisons were also drawn with other published literature on the typology and characteristics of vending in Harare. The article argues that when many low-income vendors could not operate freely during the highly restricted lock down environment, they were replaced by a new type of vendors. The restricted lock down environment favoured the well-to-do traders who could travel under the restrictions and could quickly get away from sites should that be necessary. The typology of informal vending changed during the coronavirus induced lock downs. Small-scale low-income traders were replaced by a new type of better-resourced traders that are described in this article as vendors on wheels because they mainly traded from vehicles.

The article starts with an introduction of the topic before providing a review of literature on vending and the experience of small-scale informal traders in Africa. This is followed by a discussion of the methods that were used to collect data used in the paper. The data is then presented followed by a discussion of the findings before drawing conclusions.

2. Literature review

Informality was first given scholarly prominence by Hart in the early seventies after he undertook extensive studies of cities in Ghana (Hart, Citation1973). In many cities in the global South, vending is a common informal activity. It takes different forms in different countries but has several common characteristics. In some countries and cities authorities take a more accommodating and supportive approach whilst in others both the regulatory framework and practice is constraining (Skinner, Citation2008; Skinner & Watson, Citation2018).

Vending is common and widespread in many parts of Africa (Mitullah, Citation2004). The vendors are typically female and low-income and street trade is especially important to them as it comprises 51% of all informal activities of women in sub-Saharan Africa (Roever & Skinner, Citation2016). They are mostly small-scale and have low-value wares reflective of their low-income status (Njaya, Citation2014).

The informal traders face general heavy-handedness from the police and other regulatory authorities daily in many places (Chen, Citation2012). They face many challenges even when they are licensed. Challenges faced include “generalized workplace insecurity, harassment and confiscation of merchandise of street vendors” (Roever & Skinner, Citation2016, p. 359). In Zimbabwe, planning professionals and regulatory authorities are documented as heavy-handed towards informality (Kamete, Citation2012; Rogerson, Citation2016). Planning professionals are also accused of acting in service of the rich whose values serve to suppress the innovation of these poor small-scale informal sector traders (Kamete, Citation2009). Vendors have demonstrated resilience under severe opposition from authorities (Bromley, Citation2000; Toriro, Citation2019). Generally, operating as a small-scale informal trader in different parts of the African continent is a difficult task that these vendors live with.

Despite the enormous resistance from city officials, vending constitutes an important livelihood for most low-income city residents (Skinner & Watson, Citation2018). They contribute a lot more than is acknowledged through linkages with the formal sector, generate demand for a lot of other services and contribute significantly to urban food systems. “Street vendors” contributions to urban life go beyond their own self-employment’. It is an important service to many city residents and an important cog in the larger economy (Roever & Skinner, Citation2016, p. 361). The contribution of informal street trade across the continent is huge and largely unappreciated.

Some scholars believe that vendors must be included in the economy to fully realize their potential (De Soto, Citation2000). Roever and Skinner argue that in addition to political will, “legislative reform and greater transparency in the content and implementation of regulations are needed” (Roever & Skinner, Citation2016, p. 360). But as demonstrated above, this has not happened in many cities on the continent. There is a limited appetite for accommodating informal vending activities. Planning appears to have no space for poor people’s livelihoods. Numerous scholars lament how the planned city seem to “sweep” the poor out by not considering them and their livelihoods (Kamete, Citation2012; Mpofu, Citation2010; Rogerson, Citation2016; Watson, Citation2009; A. Y. Kamete, Citation2010). Despite the documented consensus towards accommodation of these livelihood activities, policy and action have not responded as fast.

Vendors and other informal livelihoods seem to offend many planners and city managers who have modernist and utopian views of urbanism (Toriro, Citation2018; Watson, Citation2014). They cannot accept the fact that vending is part of informality that has become a new manifestation of urbanisation (Roy, Citation2005). Planners however struggle with accepting the rationale of the lived reality of the majority poor people they plan for that differs sharply with their own values (Watson, Citation2003). A past Executive Director of UN-Habitat observed that whilst planners have the potential to solve most of urbanisation’s challenges in the global South, practically that has not happened (Tibaijuka, Citation2006). Potts (Citation2008) has observed positions regarding the informal sector have been changing over time. She observes how attitudes of city managers have shifted from negative to positive and appear to be going back to negative again with regards to how they treat informality. Perhaps the attitudes of planners that have so far been largely influenced by the west can only be changed by a new robust curriculum that considers informality as a way of urbanisation in some regions of the world (Owen et al., Citation2013; Watson & Odendaal, Citation2013). This change is necessary to close the yawning gap between the lived reality of the many residents in the global South cities and the “world class city” aspirations of planners and other city managers.

3. Research methodology

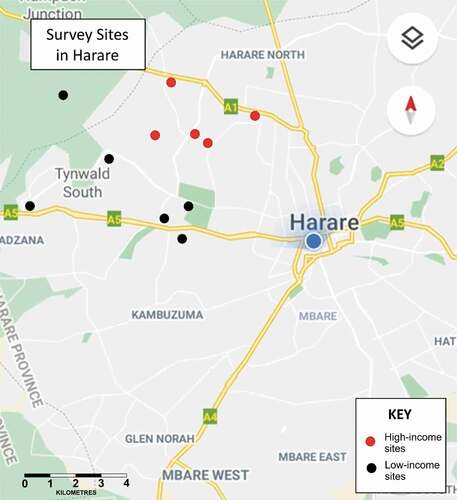

Data for the article was collected from primary sources at selected areas where vendors were known to cluster. Both quantitative and qualitative data was collected. The quantitative data pertained to sites and numbers of traders as well as range of wares. The qualitative data was collected from interviewees regarding their background and experience operating as vendors under COVID-19 restrictions. Ten sites were purposively selected in different parts of Harare that reflect the different income groups (see ). At each site 5 interviews were conducted with randomly selected traders who were willing to share their experiences. Observations of types of goods, mode of space and characteristics of traders were made using a semi-structured checklist. Secondary data sources, such as newspaper reports and published literature on informal trade, were also used to provide a background to the subject (Njaya, Citation2014; Rogerson, Citation2016; Tawodzera et al., Citation2019; Toriro, Citation2019). Data for the article was collected during the period between June 2019 and June 2020.

4. Vending in Harare in pre-COVID-19 days

To fully understand the changing patterns of street trading in Harare during the corona virus restrictions, it is important to briefly reflect on the history of vending in Harare before the pandemic restrictions. Street vending was widespread and constituted a major livelihood for many citizens within the context of an underperforming economy (Chirisa, Citation2008; A. Y. Kamete, Citation2010, Citation2013; Njaya, Citation2014; Tawodzera et al., Citation2019). There were frequent clashes between vendors and municipal authorities as city managers enforcement of planning regulations (Toriro, Citation2019). These clashes were described by some scholars as heavy-handed although the street traders still demonstrated immense resilience (Kamete, Citation2013; Rogerson, Citation2016). Most traders were low-income and carried their daily wares on public transport for display on street pavements in the city centre and small tables on suburban street corners (Skinner & Watson, Citation2018; Toriro, Citation2019). Street trade in Harare before lock down restrictions can therefore be characterised as operating at micro-scale and situated mainly in the city centre and on small tables in the residential areas undertaken mainly by poor residents.

5. The changing typology of vendors

This section presents the study findings. The data show that the coronavirus induced restrictions are changing the way informal trade is conducted as well as the scale at that it was operating as will be shown and explained below.

6. Study sites

The map in shows the location of the 10 study sites in Harare.

Most of the interviewed vendors were aged below 40 years as shown in above. There were eight vendors below the age of 20 and only four above the age of 40 years. The vendors comprised more women than men with 28 respondents being female and 22 being male.

Table 1. Demographic profile of vendors

7. Most vendors now mobile

In the many areas surveyed, it was observed that an overwhelming majority of vendors found during the COVID-19 pandemic were mobile. In all the 10 sites most of the traders were using different forms of mobile means dominated by motorised vehicles. All types of vehicles were being used from small passenger cars to large trucks as trading spaces. This was unlike in the past when most traders were pedestrian and only used vehicles to transport goods to sites.

8. Types of goods sold

The vendors were selling different types of goods, but the variety was changing over time in response to the lockdown conditions. The initial lockdown conditions were much stricter and only allowed for food trade and other things, such as medicines that were considered critical for people’s day to day survival. Most vendors initially sold food. Many cars would sell basic food stuffs, such as cooking oil, sugar, rice, maize meal, and tinned foods. Others would sell vegetables and other farm produce, such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, leafy vegetables, onions, and whole grains. Although medicines were also classified as essential, there was no visible trade in medicines in the informal sector. Trade in medicines is very strictly regulated in Zimbabwe and it has only been done by licensed professionals in formal places.

When the lockdown conditions eased, the range of goods traded by these vendors on wheels increased to include many non-food items. These included skin lotions, perfumes, clothes, toys, shoes, and many other non-essential stuffs. Food products remained the dominant commodities sold by these new types of vendors. Whilst there was an introduction of non-food items, foodstuffs remained the predominant products sold. The range of food stuffs and variety had increased to include tinned foods and fresh fish in frozen containers.

9. Downward shift and new traders

Many of the vendors on wheels were new to the sector. They previously worked in offices or ran other businesses but were stuck at home due to the COVID-19 restrictions. Some of the vendors previously operated as vendors but were now employed by people with cars or approached people with cars so that they could operate as a partnership. Almost half (48%) of all traders were new vendors who started the small businesses as alternatives to their affected businesses or closed work places.

‘This is my first-time trading in food products. I was a teacher in a public primary school before the lockdown. I used to complement my income by conducting extra lessons to children who are slow learners. Due to the coronavirus restrictions, no parents have brought their children for extra lessons and so my vital income stream stopped. My friend has a farm, and their market options are now limited by the pandemic. Meanwhile, I found a need for food in my locality. I now use my car to get fresh produce from my friend’s farm and sell from the road side.’ (Mrs Chandiwana, 2020Footnote1).

Her story differs from that of Edza who already operated as a vendor selling vegetables from Harare city centre.

‘Prior to the pandemic I operated from the city centre. But business was getting tough with increased raids by the municipal police. The frequency of joint raids by municipal officials working with the national police and sometimes with soldiers was increasing making our business very difficult. During the pandemic I approached my uncle who owns a truck with an idea to work together. It has worked perfectly. He used to work in the bank but has not been called back to work and so was idle at home with his truck. I have shown him where to get fresh produce and taught him the basics of trading, such as pricing and marketing. He is happy with me because I can handle those aspects of the business that he cannot. We are both happy and are surviving decently under the difficulties’ (Edza, 2020Footnote2).

Both these cases show that some middle-income people who never worked as vendors before, have joined the popular informal trade sector. Whilst there some old vendors, such as Edza who also joined the vendors on wheels, this shift means that the new well-to-do vendors may have elbowed out some poor vendors. There has been a downward structural shift of people from higher income brackets who have entered the space that was previously the preserve of the poor.

10. Need for space for storage

The new vendors indicated that they traded from cars because of the need for a combination of storage and trading space. These cars serve as storage space for excess stock. The also serve as the retail space from where the wares are sold. One vendor explained this:

When the COVID-19 restrictions were introduced, they impacted on freedom of movement. In the past vendors would store most of their stock and only display minimum stock as a measure to minimise losses when the municipal police raided. With the coronavirus restrictions, there were no options for storage anywhere nearby and so you had to have all your daily stock with you. Only cars could offer that capability.

The cars constitute a more robust environment that responds to the challenges imposed by the lockdown restrictions. They have more space and so can meet the twin requirements of storage and display.

11. Need for Means to Travel

The restrictions have also introduced the need for private means to travel. The local corner table may no longer be possible because there may no longer be a viable market. The few pedestrian vendors were found in a few places, but these were being eclipsed by the more visible vendors on wheels. Vendors are identifying new locations where customers can still come, and these may not be within walking distance of pedestrian vendors. Mobility provides the possibility of travelling and sampling places for viability, safety, and ease of surveillance for enforcement forces. As the vendor below said, without mobility, one is dis-empowered:

Nowadays a vehicle is everything if you want to trade. Otherwise how do you access the trading places when there is no public transport? You need your own vehicle or access to one. I quickly realized that and so I approached a friend for his vehicle. He kindly rented me his vehicle and so I pay him a weekly fee of 50 USD for use of his truck. This is what has enabled me to continue to trade, otherwise most of the people I used to trade with are stuck at home (Thandiwe, 2020).Footnote3

As Thandiwe indicated above, a vehicle became an essential tool of the business of street vending, separating those that could trade and those that were pushed out of business. Mobility became the difference between going to work and staying at home. The restrictions grounded all other means of public transport hence only those that could find own means of transport could survive.

12. Social distancing

Vehicles also enabled traders to comply with the need to maintain a safe distance from the next person, a phenomenon commonly referred to as social distancing. One of the main interventions recommended and strictly enforced by governments across the world to curb the spread of the virus was social distancing in the conduct of any business. This was expected in all aspects of life, such as when people travelled or, as they shopped, and as they generally interacted. Whereas traders could cluster and trade close to each other prior to the pandemic, the new regulations required the keeping of safe distances, oftentimes at least 1 m from the next person. Those with vehicles could easily comply by parking or moving their car a safe distance from the next trader. They could also comply with the new requirement to avoid crowded spaces during travel. There were many check points where the police would inspect how travellers were seated and spaced in a vehicle. It was not easy to keep safe distances unless the vehicle was yours and you controlled how many people could be transported. Many pedestrian vendors used small trucks in groups as means of transport for themselves and their wares prior to the pandemic and during the pandemic. They were however stopped and sometimes fined for being “overcrowded” in these trucks.

13. Quick response to enforcement

Vehicles also provided the means for a quick get-away when that was required. The authorities in Harare also took advantage of the lockdown to increase their clampdown on vendors. Many traders who tried to trade in their usual places were raided and lost all their stock as it was confiscated by municipal police. Some were also arrested during the raids. So, vendors suffered double losses; they were arrested and had to pay fines whilst their stock was taken by local government. Only those that had vehicles could quickly close their car doors should they be trading where they were forbidden, and quickly drive away, or pretend they were just parking as highlighted in the interview below.

“The car helps when there is a police raid because if you get alerted early enough, you simply close the car and pretend you are doing something else, or you just drive away. When you are a pedestrian, you have nowhere to hide. These days a car is useful in providing cover or a quick getaway when necessary” (Gibson, 2020)Footnote4

Vehicles therefore also became the means to quickly respond to the traditional harassment and confiscation of wares by municipal officials. Without a vehicle it was easy to be caught. Being caught whilst trading by raiding police officers means a trader loses their wares and get arrested as well.

14. Alternative use of banned informal omnibuses

A significant number of the vendors on wheels were formerly operators of commuter mini buses whose services were banned as part of the COVID-19 restrictions. Thirty percent of the vehicles being used by the vendors on wheels were commuter omnibuses that were being adapted for street trade. Whilst these used to operate as 16-seater buses, but they were now redundant at home. Many were re-designed as mobile shops with shelving having replaced passenger seats. Zimbabwean authorities took a particularly harsh position regarding the commuter omnibuses during the coronavirus lock downs. For many years, the operations of these small volume commuter omnibuses caused headaches to municipal and national government authorities. The coronavirus pandemic presented an opportunity to deal with this problematic sector. Many owners of these informal public passenger vehicles found themselves out of business with the COVID-19 restrictions. The new need by the vendors on wheels created new alternative business for owners of the mini buses.

15. Discussion

The restricted operating environment under the coronavirus pandemic was found to be shifting the character of the small-scale informal trade by replacing the usual operators with other better-resourced people. The small-scale street traders were found to have been stopped from accessing their previous livelihoods by the restrictions. The operating environment was now found to have a clear absence of the lowest income group of people that have been documented as constituting most people comprising the informal sector vendors in literature (Chen, Citation2012; Njaya, Citation2014; Skinner, Citation2008; Skinner & Watson, Citation2018).

The use of vehicles by these new informal traders was causing an increase in the volume of wares carried by traders as well as the scale of the activities. Whereas previously vendors in Harare were reported to be carrying small quantities of stock to minimise risk of loss of goods to enforcement agents, such as municipal police and soldiers, the vendors on wheels were different (Toriro, Citation2019). They carried huge stocks of goods in comparison to the previously observed phenomenon.

The small-scale vendors appeared dis-empowered. Past studies found vendors radical and fighting to defend their “illicit livelihoods” (A. Y. Kamete, Citation2010). In this study the few small-scale vendors that were found still trying to trade no longer displayed capacity to fight for their space. The sheer force of security forces and the strict regulations under the pandemic severely weakened this group of traders. They could no longer organize and fight back as was becoming the trend. The limited numbers of people allowed free movement deprived the vendors of cover. It was very easy to be noticed on the streets when there were limited numbers of people moving around.

The vendors on wheels exposed the difficulties that traders face in transporting their produce from wholesale markets as well as around different areas where people live. Although they were considered as an essential service during some periods of the lockdown, they reported that they were often stopped at checkpoints and experienced immense difficulties in moving wares. The main problem they encountered was being considered to be using inappropriate transport where they did not observe safe distances or “social distancing”.

16. Conclusions

In many parts of Harare, the typology of vendors changed during the COVID-19 restrictions. Most of the vendors were now trading from vehicles, a significant departure from the previous situation where vendors were typically low-income and kept very small stocks. Previously vendors traded from small containers and spaces, such as dishes, small tables, or laid their wares on street pavements. There has been a structural shift in the income status of the new vendors. Poor vendors have been elbowed out of their vending spaces and are being replaced by people with access to bigger assets, such as cars. Most people interviewed indicated that they are new to street trade as they were previously employed in other jobs mainly in the formal sector. They were teachers, bankers, and other professionals holding qualifications in other areas. There were few individuals who reported having been vendors in the informal sector before the pandemic. Although the type of goods traded changed over time, most traders were forced to trade in food products as these fell under what authorities classified as essential services. At the beginning of the restrictions, all the vendors on wheels traded in food products, such as potatoes, vegetables, and mealie meal. When the conditions were somewhat relaxed, more varied goods including non-food items came on the market. During the period when lock down conditions were relaxed, the non-food items that were introduced to the market included body lotions, perfumes, detergents.

These vendors on wheels constitute a major shift in the informal trade business. They have introduced a new way of street trading that never happened in the same environment before. These challenges the documented ways in that street trade occurs in African cities where mainly poor small-scale traders dominate the sector (Bromley, Citation2000; Hart, Citation1973; Mitullah, Citation2004; Skinner, Citation2008; Skinner & Watson, Citation2018). At this stage it is too early to know whether this is a temporary or permanent change. It however shows how adaptive the informal sector is to changes in the operating environment. It also proves the resilience of informality in cities of the global South (Toriro, Citation2019). Presented with challenges of different types, informality has survived by adapting to the new environment. In Harare’s case under the coronavirus restrictions, some of the traders have been replaced by new ones. Time will tell whether the previous micro-scale vendors will be able to reclaim their space at the end of the restrictions. Meanwhile policy makers and planning officials must intervene and protect the low-income traders who have been elbowed out by lack of access to vehicles. They have lost livelihoods and must be empowered so that they can continue to feed their families. Inclusive cities ensure that all residents are protected and given an opportunity to live decent food secure lives. Allowing vendors on wheels to take over at the expense of other weaker citizens only solves part of the problem. A more sustainable and equitable solution is required.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Percy Toriro

Innocent Chirisa is a professor at the Department of Demography Settlement, University of Zimbabwe. He is currently the dean of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences at the University of Zimbabwe and a Research Fellow at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Free State, South Africa. His research interests are systems dynamics in urban land, regional stewardship and resilience in human habitats.

Innocent Chirisa

Percy Toriro is an Urban Planner practicing in Eastern and Southern Africa. He is also a Research Consultant with the African Centre for Cities and past President of the Zimbabwe Institute of Regional and Urban Planners. He also taught in the Planning School at the University of Zimbabwe and once headed Town Planning for the City of Harare. Percy holds a PhD from the University of Cape Town and is a Fellow of the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Canada. His research includes Housing, Urban Informality, Food Systems and Security, Migration, Urban Environments and Sustainability.

Notes

1. Not her real name. Pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of the traders.

2. Not his real name. The vendor’s real name was not used to protect them from possible identification.

3. Vendor interviewed at a site in Madokero suburb (Harare West) on 16 July 2020.

4. Vendor interviewed in Mabelreign suburb on 20 July 2020. Please note that a pseudonym was used to protect respondent.

References

- Battersby, J. (2018). Cities and urban food poverty in Africa. In G. Bhan, S. Srinivas, & V. Watson (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to planning in the global South (pp. 34-36). Routledge.

- Bromley, R. (2000). Street vending and public policy: A global review. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 20(1/2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330010789052

- Chen, M. A. (2012) The informal economy: Definitions theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper No.1, August Cambridge.

- Chirisa, I. (2008). Population growth and rapid urbanisation in Africa: Implications for sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 10(2), 361–394.

- De Soto, H. (2000). The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the West and fails everywhere else. Basic Books.

- Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00008089

- Kamete, A. Y. (2009). In the service of tyranny: Debating the role of planning in Zimbabwe’s urban clean-up operation. Urban Studies, 46(4), 897–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009102134

- Kamete, A. Y. (2010). Defending illicit livelihoods: Youth resistance in Harare’s contested spaces. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00854.x

- Kamete, A. Y. (2012). Interrogating planning’s power in an African city: Time for reorientation? Planning Theory, 11(1), 66–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095211419116

- Kamete, A. Y. (2013). On handling urban informality in southern Africa. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 95(1), 17–31

- Ministry of Health. (2020). Daily COVID-19 statistics published by the Ministry of Health and Child Care. Government of Zimbabwe

- Mitullah, W. (2004, August). A review of street trade in Africa. In M. A. Chen (Ed.), The informal economy: Definitions theories and policies. WIEGO Working Paper No.1(p. 321). Cambridge

- Mpofu, B. (2010) No place for ‘undesirables’: The urban poor’s struggle for survival in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, 1960-2005 [PhD Thesis submitted to the University of Edinburgh].

- Njaya, T. (2014). Operations of street food vendors and their impact on sustainable urban life in high density suburbs of Harare, Zimbabwe. Asian Journal of Economic Modelling, 2(1), 18–31.

- Owen, C., Dovey, K., & Raharjo, W. (2013). Teaching Informal Urbanism. Journal of Architectural Education, 67(2), 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2013.817164

- Potts, D. (2008). The urban informal sector in sub-Saharan Africa: From bad to good (and back again?). Development Southern Africa, 25(2), 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768350802090527

- Roever, S., & Skinner, C. (2016). Street vendors and cities. Environment and Urbanisation, 28(2), 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247816653898

- Rogerson, C. M. (2016). Responding to informality in urban Africa: Street trading in Harare, Zimbabwe. Urban Forum, 27(2), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-016-9273-0

- Roy, A. (2005). Urban Informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

- Skinner, C. (2008). Street trade in Africa: A review. School of Development Studies, University of Kwazulu-Natal.

- Skinner, C., & Watson, V. (2018). The Informal Economy in the Global South. In G. Bhan, S. Srinivas, & V. Watson (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to planning in the global South (pp. 140–151). Routledge.

- Tawodzera, G., Chigumira, E., Mbengo, I., Kusangaya, S., Manjengwa, O., & Chidembo, D. (2019). Characteristics of the urban food system in epworth, Zimbabwe. Consuming urban poverty working paper No.9. African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town.

- Tibaijuka, A. K. (2006). The importance of urban planning in urban poverty reduction and sustainable development. World Planners Congress.

- Toriro, P. (2018) Food production processing and retailing through the lens of spatial planning legislation and regulations in Zimbabwe [PhD Thesis]. University of Cape Town.

- Toriro, P. (2019). Resilience under Sustained Attack from the City Police: Will informality survive? Journal of Urban Systems and Innovations for Resilience in Zimbabwe, 1 (1), 2019. University of Zimbabwe Publications, Harare. https://jusirz.uz.ac.zw/index.php/jusirz/article/view/153

- Toriro, P., & Chirisa, I. (In print). Harare: Evaluating and epitomizing master plan performance in an African City in search of a positive future. Palgrave.

- Watson, V. (2003). Conflicting rationalities: Implications for planning theory and ethics. Planning Theory and Practice, 4(4), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000146318

- Watson, V. (2009). ‘The planned city sweeps the poor away…’: Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation. Progress in Planning, 72(3), 151–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002

- Watson, V. (2014). African urban fantasies: Dreams or nightmares? Environment and Urbanisation, 26(1), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813513705

- Watson, V., & Odendaal, N. (2013). Changing planning education in Africa: The role of the association of African planning schools. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 33(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X12452308