Abstract

As an archaeological heritage, valuable heritage settlements entail preservation to avoid destruction and eventual extinction. Intending to propose a study for revitalising heritage villages, Tinbak is selected as a case study. It is an old abandoned village in Qatar identifiable by its distinct yet straightforward local architecture features. This article applies the concept of sustainable tourism to architectural heritage with consideration to social, cultural, and economic factors. The study employs qualitative research methods, grand and mini-tours, interviews and SWOT analysis with attention to three objectives, 1. Maintain the domestic identity of Tinbak; 2. Shift the value of space from residential to an attractive, sustainable touristic place; and 3. Highlight the connectivity to adjacent communities and open lands as a means of enhancing accessibility and ecotourism. To implement tourism sustainability, the study suggested the guidelines of the albergo diffuso model that promote local culture, stimulate the local economy and considering environmental sustainability. Recommendations suggested protecting and conserving the existing heritage, considering the surrounding rural area as part of revitalising the village, engaging the stakeholder and the citizens in the decision-making, and revitalisation management to ensure the successful transformation of a heritage village from an abandoned place to an operationally sustainable tourist centre.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The world is going through globalisation that is categorised by sharing knowledge, cultural exchange and environmental concern. This study represents the potentiality of cultural heritage tourism as a means of global sharing knowledge by proposing a study of the heritage village of Tinbak, Qatar. The village consisted of 18 houses, a mosque, and 3 public guest halls. It was abandoned in 1970; experiencing neglect and misused ever since. The analytical study of its strengths, opportunities, threats, and weaknesses shows its suitability for revitalisation. The albergo diffuso, an Italian concept that means “scattered hotel,” is the followed approach in this study. It is a solution that offers traditional lodging and an area like a private home. This study is an excellent example of the conservation of heritage places and their conversion into tourist attractions to reach the global position while preserving their distinctive identity.

1. Introduction

Tourism has grown at an accelerated pace over a couple of decades. Forecasts suggest an ever rapid growth rate into the new millennium (World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Citation2020). The first mass visits for leisure purposes to remote and hard-to-access rural areas took place after railways’ innovations in the 19th century (Roberts & Hall, Citation2001). As the Industrial Revolution began in Western Europe, technological trends facilitated human experience and human mobility. Moreover, after the significant advances in labour rights and work conditions in the early 20th century, people had greater access and time for movement and touring. One of the tourism enterprise pillars has been the inherent desire to explore and study the cultural identity of various parts of the globe (Ismagilova et al., Citation2015; Short, Citation2004). In domestic tourism, cultural heritage stimulates national pride in cities and countries’ history (UNESCO, Citation2013). The appreciation and understanding of other cultures promote peace and better communication (Emerson, Citation2017).

Since the 1990s, writing on tourism, sustainable tourism and ecotourism have increased significantly in publications and scientific journals. Currently, the study in tourism encompasses social, cultural, and economic perspectives and includes environmental and governance magnitudes (Bramwell et al., Citation2017; Swarbrooke, Citation1999). Cultural heritage attractions are unique and fragile (Nepravishta, Citation2018), particularly in rural or conservative sites. Heritage revitalisation should follow the ecotourism and sustainability approaches as inevitable requirements for successful results (Tsaur et al., Citation2006). Sustainability and revitalisation are feasible development (Steinberg, Citation1996). It prevents a heritage village from extinction while transferring it to a living heritage (Zhao, Citation2020). It benefits not only the local environment but also society and culture (Sharpley, Citation2006). The research intends to study the historical Qatari village of Tinbak to illustrate an approach of revitalising an authentic heritage settlement by rehabilitating its structural and functional elements to attract tourists. This study is aligned with the heritage policy as part of Qatar’s national vision (General Secretariat For Development Planning, Citation2018). The country has an advantage related to climate characteristics and arid land. Winter has an ideal temperature that stretches from December to February, where the temperature ranges from 17 to 25°C (Qatar Climate, Citation2020). Like other GCC countries, Qatar attracts people from Europe and northern countries where the winter is freezing in winter. It has become common to build resorts on the periphery of deserts to experience the barn landscape and perform sports such as climbing dunes. Therefore, Qatar depends on conventional tourism development 3 Ss model of Sea, Sand and Sun. In the last two decades, it has added the 4 Ss model of Safari, Skyscrapers, Sport, Shopping, and Surgery (Giampiccoli & Mtapuri, Citation2015). Both the 3 Ss and the 4 Ss have led to diversification strategy to attract tourists globally (Hazbun, Citation2004) as “globalisation has decentered the national scale of social relations and intensified the importance of both sub- and supra-national scales of a territorial organisation” (Brenner, Citation1999). John Rennie Short (Citation2004) sees globalisation as an opportunity for diversity and distinctiveness of local places.

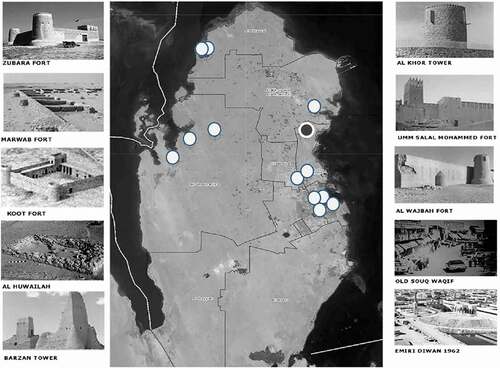

Qatar National Tourism expects the tourism industry to contribute up to 5.5% of the GDP by 2030 (‘QTA Unveils “Qatar National Tourism Sector Strategy Citation2030”’, 2014). With this expectation, the country aims to revitalise heritage sites and use historical resources for economic and social purposes to create the basis for interest in identifying viable historical resources and examining their potential as a factor promoting economic activities, particularly tourism (Mansfeld & Winckler, Citation2007). shows the location of Tinbak with a few illustrations of the significant buildings in Qatar.

Figure 1. Major historic locations state of Qatar. The black dot is the location of Tinbak.Footnote1

Over time, people changed and developed their built environment to meet their changing needs, resulting in unique spatial identities (Oakes, Citation2018). The intangible environment is as crucial as the authentic physical environment (Ahmad, Citation2006). Documenting the culture, ideology, and social environment of Tinbak is vital not only to imagine what spatial behavior may have been like there but also to understand the reasoning behind the form and shape of the traditional buildings and urban layout (Ferwati, Citation2010).

1.1. Objectives and methodology

The village of Tinbak lacks architectural, historical, and social documentation. Thus, obtaining the necessary data about Tinbak for this research requires extensive documentation, including physical surveys, architectural and urban drawings, and the spatial elements’ inventory. The revitalisation of Tinbak follows three objectives:

Maintain the domestic identity of Tinbak

Shift the value of space from residential to an attractive, sustainable touristic place.

Highlight the connectivity to adjacent communities and open lands as a means of enhancing accessibility and ecotourism.

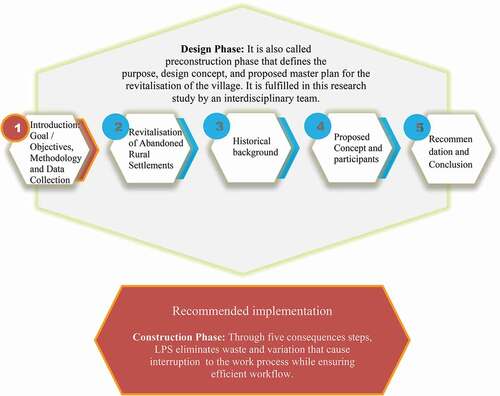

Before any intervention, the conservation of the premise must, first, acquire data of the townscape and building forms and, second, avoid any damage, falsification, or deletion of historical evidence. Minimum intervention is required to rehabilitate the village and ensure sustainable touristic development. A relentless reverence must regulate every interference in its cultural, historical, and physical entities (Rushi, Citation2016). shows the schematic flowchart of the study.

Collecting the necessary data involved both a grand tour and mini-tour. The grand-tour was general observation throughout the research area to obtain an image of its condition as a whole. We documented this research phase in notes, diagrams, photos, sketches, maps, as well as data of buildings and urban layout. The mini-tour included in-depth observation and 3D scanning of the village.Footnote2 For cultural documentation, we recorded interviews with the previous residents of Tinbak, including young and elderly family members and public figures.

1.2. Revitalisation of abandoned rural settlements

The world is going through globalisation that is categorised by sharing knowledge, cultural exchange and environmental concern. Several successful studies from different parts of the world are helpful references that provide thoughts and direction to the study of Tinbak. “Globalisation is not just about replacing difference with sameness, but providing opportunities for new interactions between spaces and locations, new connections between the global and the local, new social landscapes and more diversity rather than less” (Brenner, Citation1999). Considering the significance of revitalisation of heritage sites, “Domestic and international tourism continues to be among the foremost vehicles for cultural exchange, providing a personal experience” (ICOMOS, Citation1999). Tourism creates new economic sources for nations. When it involves natural conservation, it is referred to as ecotourism (Epler Wood et al., Citation1991; Kiper, Citation2013). Ecotourism is recognised as a positive and weak force for preserving natural and cultural heritage (ICOMOS, Citation1999). When visitors interact carelessly with the natural environment, they weaken the positive forces by harming the environment, such as throwing plastic in the sea and hunting rare species. The buoyant force of ecotourism enhanced the local government’s consideration of conservation, for example, the ecological footprint, the economic impact for local communities, socio-economic effects on production and job creation, cultural adjustments, and spirituality. Given that Tinbak is a village surrounded by natural open space and nearby sea, the consideration of its unique ecology and surrounding adds extra attraction to it as an ecotourism site. Such attention will promote the sustainability of the rehabilitation development of Tinbak as a tourist site because it complies with the four main attributes of sustainability: the environment, social, economic, and education (Diamantis, Citation2010; Kiper, Citation2013; Ross & Wall, Citation1999).

A scenario for protecting cultural resources in deserted rural settlements is re-functioning or revitalising tourism sites, either entirely or partially (Dincer & Dincer, Citation2005; East, Citation2017; Güler & Kâhya, Citation2019). Several studies applied different approaches for revitalizing abandoned villages or ghost towns (Brown, Citation1971). One of which is that approach that defines the causes of abandoning the village as a way to find a solution to bring life to the village. East (Citation2017) listed 23 causes such as fire, earthquake, flood and dam break, land sliding, migration, and urbanization. The solution to ghost town depends on the causes and condition of the village; however, the solution considers ecological perspective in addition to sustainability perspectives of social, economic and environment. 2. Ecovillage movement or back to land movement (East, Citation2017) that is defined as “human scale settlements, rural or urban, … ., that strive to create models for sustainable living.” (Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), Citation2014). An example will be Torri Superiore ecovillage, located in Ligurian Alps between the French-Italian border. 3. Albergo diffuso model for reviving several historical buildings to form a scattered hotels to attract tourists (Girard & Nijkamp, Citation2016). 4. The study “Conservation of Abandoned Rural Settlements in Turkey,” by Güler and Kâhya (Citation2019). It classified the revitalisation of rural heritage settlements into four approaches: reforestation, museumification, tourism, and resettlement. outlines these approaches and their implementation.

Table 1. Approaches for a reevaluation of rural settlements. Developed by the authors after Güler and Kâhya (Citation2019)

The conservation of heritage places and their conversion into tourist attractions is a contemporary global trend. The preference of entertainment activities for tourism is based on the sea, sand, and sun as much as the case of the 20th century that marks the beginning of the increase in tourist choices. Rural areas with natural and cultural facilities attract more tourists due to the growing desire and demand for alternative vacations and entertainment (Kiper, Citation2013). These choices are due to several reasons such as advanced academic level and intellectual potential, globalisation, development of new advertising techniques, change in holiday perception, urbanization problems, and improved social mobility.

2. The case study

2.1. Historical background and participants

The village of Tinbek sits in the municipality of al-Daayen. It is accessible from al-Khor Coastal Road 45 km away from Doha, Qatar’s capital city, and 8 km from al-Khor, the second major city in Qatar (). The area once served as a Bedouin camping ground that sourced their drinking water from a masonry well sunk into the stony ground at a depth of seven fathoms (Lorimer, Citation1908). The location of Tinbak and its abundance of freshwater wells attracted Alhumidi tribe to initiate their urban settlement. The village consisted of 18 houses, a mosque, and 3 separate public guest halls (Majlis). The village was completely abandoned in 1970 after the government offered the inhabitants free lands next to Tinbak.

Figure 3. The regional context and location of the study area, Tinbek Qatar. Source: the left map from Qatar Development Atlas -Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics, while the right plan, developed by the authors, shows a figure-ground map of the village

Although ownership of the village was deferred to the state after granting new housing to its residents, some people continue exercising their guardianship and exploiting the place. Today, the village is subject to vandalism and misuse, with some taking advantage of its abandonment to use its rooms for storage and the open areas for leaving old cars. Others continue to use some of the barns to raise cattle. During our site visits, we noticed that the extent of misuse only involved storage. shows a few views from the village, indicating its current condition. It is worth mentioning that, likely due to nostalgia; one may see people pass by the village on their way to neighbouring farms.

As a result of years of neglect, the village, with its distinctive Qatari and ancient Arab forms, is rapidly deteriorating. Because of this long neglect and misuse, the village requires urgent preservation with attention to its historical values and archaeological heritage.

Tinbak sits between several old and new roads, making it accessible for local visitors and tourists. Besides, Tinbak rests beside Al-Khor Coastal Road that is used for car races and rallies. Visitors of different nationalities, who attend the races held annually, can take advantage of the proximity to the village to visit and rest. Therefore, revitalising an abandoned site like Tinbak is essential. Bringing life to the village is a form of urban recycling development because it decreases construction waste.

Additionally, it not only generates revenue but also promotes local identity along with the attention of tourists. Therefore, revitalising the village is sustainable. Seeking the best plan for revitalising the village, we examined the potential application of Güler and Kâhya’s four approaches to revitalise rural settlements. summarises this analysis.

Table 2. Approaches for a reevaluation of rural settlements and their applicability to Tinbak. The general implementation of each approach is shown in above

2.2. Tinbak SWOT analysis

In Tinbak’s traditional housing typology, each house has a detached kitchen and storage for grains, oil and sugar. Some larger houses also have a guest room (majlis). The village’s fabric reflects a minimal architectural style; the walls are made of stone, clay mortar and clay plaster, while the roof is made of a few local timber sources available in Qatar, such as palm tree trunks fronds and leaves. The traditional layout of the houses has a simplicity that reflects the life of its residents. The houses consist of two multi-functional rooms with a bathroom in between. Most houses in Tinbak have a colonnade, forming access to the rooms. The colonnade is also an outdoor seating area for hosting guests or leisure at night after a day’s work. Each house has a large central courtyard, where family activities take place. Four exterior staircases across the village lead to the rooftops with a remarkable view of the village ().

Rural characteristics are an abstract and subjective concept as everyone may already have an idea or an image in their mind. However, some critical rural features, such as architecture and traditional residential layout, are the most unique as indigenous rural-scape as they blend better with the surrounding environment (Liu, Citation2010). Other essential characteristics, tied to the rural village of Tinbak, require site visits to comprehend the overall views of the village and its surroundings, sequences of views throughout passageways, views from the rooftop (roof landscape), views of public spaces, views of natural landscapes, and close up view of architectural and urban details such as the construction materials ( and ).

Figure 5. The master plan and land-use map for the existing structures in the Tinbak village. The pie-chart indicates the percentage of land use areas, the image shows the colonnaded area, and the plan is a 3D scan of the house in the middle of the left-hand side

The villagers’ major work includes either grazing camels, fishing, or hunting in the Qatari mainland. In some cases, courtyards were used to raise cattle. The abandoned village of Tinbak has excellent urban and architectural characteristics, but is it suitable to be converted into a tourist attraction? We utilized SWOT analysis to respond to this question.Footnote3 SWOT stands for four attributes: strength and weakness as internal factors, and opportunity and threats as external factors. SWOT is an instrumental tool for assessing the success and potential of urban sites, buildings, and outdoor activities (Dealtry, Citation1994; Gürel, Citation2017; Karppi et al., Citation2001) from the sustainable tourism’s three perspectives: economic, environmental, social, and ecology (East, Citation2017; Swarbrooke, Citation1999). The analysis of Tinbak’s current condition and urban context are listed in . The analysis reports six significant strengths, eight excellent opportunities, four manageable weaknesses and three expectable threats for the abandoned village. While the strengths and opportunities indicate the feasibility of the development, the weaknesses and threats indicate the required effort and cost to achieve the project’s aim.

Figure 8. Illustrates the deterioration of buildings in Tinbak as one of its internal weaknesses. On the other hand, its strength appears in the old building that reflects traditional Qatari architecture and traditional roof construction techniques

Table 3. SWOT analysis of the study case of Tinbak. The authors conducted an online questionnaire to determine the weight values of SWOT attributes. Ten participants from the Geography Program, the Philosophy Program, the GIS Program, Computer Science and Engineering, Architecture and Urban Planning at Qatar University; three from the Ministry of Municipalities and Environment; and one from QMA. The strength and opportunity have 16 attributes. The weakness has 6 attributes that will add cost to the project. The threat has only 3 attributes resulted from negligence. It is anticipated that without the revitalisation of the village, the threat attributes will result in significant damage to the heritage village

2.3. Proposed concept

In response to the SWOT analysis of Tinbak and the four approaches defined by Güler and Kâhya (Citation2019), we proposed a master development plan for revitalising the villageFootnote4 ( and ). The master plan has four zones () that hold different activities for targeting tourists and local visitors. The master plan tailors the location of the site to locate 3 gates to the village. Gate 1 forms the main corridor through the village between Zones 2 and 4 and ending at the mosque in Zone 1. As one walks inside the village from Gate 1, a large, linear, open space stretches ahead, forming the project’s spinal circulation that gradually leads to semi-private areas surrounded by buildings. shows a proposal of the detailed master plan. It shows that the designated car parking areas are outside Gate 1 and 2, enhancing the pedestrians’ walking experiences inside the village. As visitors enter through Gate 2, they will pass by many public facilities and spaces for cultural events in Zones 3 and 4, including an open-air theatre. Zone 2 is the most serene area of the site, with traditional housing acting as a scattered hotel. Gate 3 opens onto the village’s prominent landmark, the mosque, resting on the northwest corner (). With its distinctive minaret, the mosque creates a head-turning moment (Ferwati, Citation2007) that leaves a lasting impression as people walk into the open-air museum zone defined by the edge of several traditional buildings.

2.3.1. Zones 1 and 4: open air museum and cultural event area

After adopting the Geneva Declaration in 1956, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) established the European Open Air Museum Association (AEOM) in 1972 to determine international criteria for open-air museums. AEOM suggests the protection and restoration of rural buildings in their original environment as much as possible to improve the scientific quality of the outdoor museum approach (Eres, Citation2016, p. 162). Preserving cultural assets in their authentic environment has become more prominent with modern conservation principles in the 1960s. The International Colloquium on Folk Architecture held in 1971 (UNESCO, Citation2013) and The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS, Citation1999) encourages open-air museums to protect rural buildings.

In Tinbak, open spaces can act as extensions of the indoor museum in Zone 1. This extension would expand the education of visitors and tourists about tangible and intangible Qatari heritage. The open-air museum accommodates events and cultural activities, including an outdoor theatre, social events, traditional arts, crafts and foods, falconry and houbara hunting, Saluki dog sustainable hare hunting demonstrations and traditional food in traditional Bedouin tents. The indoor exhibits focus on the village’s historical value in its traditional social life and economy.

2.3.2. Zone 2: albergo diffuso—the scattered hotel model

The albergo diffuso, an Italian concept literally translating to “scattered hotel,” is a type of accommodation that offers traditional lodging together with an area that is like a private home (Dall’Ara, Citation2015; Reichert-Schick, Citation2018). One of the unique characteristics of this design approach is its horizontal structure which spreads the hotel services over numerous scattered buildings (Lanfranchi et al., Citation2009). The guest rooms and residential units, for example, maybe located on different streets within the neighbourhood. At the same time, the reception area is placed, for example, in Zone 1, the restaurants in Zone 2, and other amenities in Zone 4, all within a 200-meter radius in Tinbak. The model design is structured in a horizontal layout as opposed to typical vertical hotels by providing visitors with accommodation across several properties, especially in small heritage towns or villages. The model’s main objective is to allow guests to experience living in historical areas, enabling visitors to embed themselves in these neighbourhoods like the ancient residents of the place and simultaneously to the services of hospitality. Details of the villagers’ life can be fulfilled by adding full-size figures imitating various actions (Hashimoto et al., Citation2020), such as neighbours standing beside a shared fence talking to each other, a group of women gather in a wedding celebration, and family sitting on the floor having their meal. The concept prescribes that the interiors of the rooms should be well designed to high standards while keeping an image of an authentic and warm local style. The concept also highlights the importance of providing all the services of a traditional hotel. For example, bedrooms are scattered around the historical and heritage sites within a radius of 200 meters from the centre. Guest services include reception and concierge assistance, common public spaces, dining areas, and room service ().

The implementation of albergo diffuso in the village of Tinbak would mark a unique tourism destination as the first of its kind in the country. The guidelines of the albergo diffuso model consider the aspects of sustainable development in many ways:

Figure 11. Promoting local culture: One reason tourists select this type of accommodations is to enjoy the experience of the authentic local culture of the place. (Printed with permission from the Dall’Ara, Citation2015)

Promote the local culture: One reason tourists select this type of accommodations is to enjoy the place’s authentic local culture.

Stimulate the local economy: implementing the Albergo Diffuso model encourages the previous homeowners of Tinbak to collaborate in an organisation that supports the prosperity of small businesses working in traditional sectors like handicrafts and food preparation.

Protect the environment: keeping existing buildings and enabling them to have a second life that helps protect the village’s history and limits the environmental damage and carbon intensity of new construction.

2.4. Recommendation and conclusion

The study represents an approach to the potentiality of cultural heritage tourism at a village scale. It shows that revitalisation of Tinbak is a necessary action to bring life to the abandoned village. The anticipated success of Tinbak revitalisation is based on location, accessibility, location context, and architectural characteristics. Tinbak is located at the centre of the active eastern side of Qatar. Farms surround it alongside simple architectural features signifying its advantage among other places in the country. The study of the revitalisation of Tinbak focuses tightly on coupling the physical environment with learning and experiencing traditional local life.Footnote5

The following are several recommendations to ensure the successful transformation of a heritage village from an abandoned place to an operationally sustainable tourist centre:

Protect and conserve the existing heritage: If we do not prudently preserve valuable structures, the damage would be irreparable and irreversible and extends to hurt global and domestic cultural identities (ICOMOS, Citation1999). Thus, the promotion of tourism around unique culture and heritage requires revitalisation and protection and preservation.

Accessibility to cultural heritage: The cultural heritage should be accessible to the public, whether for the citizen who has the right to participate in the local heritage villages or tourists whose intention is to explore the uniqueness of new places (ICOMOS, Citation1999; Sani, Citation2020)

Heritage protection: It is critical to consider different tourist behaviour to avoid the misuse of heritage sites (Powell & Ham, Citation2008).

Tourism environment: It is essential to establish environmentally friendly tourism. (Richtzenhain et al., n.d.)

Traditional features, practices, and lifestyle: The success of touristic sites requires focusing on what makes the place and its inhabitants attractive. For example, Tourists, who are visiting Qatar, are interested in exploring, for instance, bedouin practices (e.g., falconry, camping).

Citizens’ participation: Local inhabitants and former residents should be part of the decision-making and participating in the running of the place to ensure successful cultural representation (Ziffer, Citation1989).

Rural context: It is always advantageous to include the surrounding farms or settlements to facilitate rural tourist activities (Yachin & Ioannides, Citation2020) as an approach to ecotourism.

Stakeholders: The revitalization of a heritage site affects directly or indirectly the entire society; therefore, stakeholders should include not only governmental agencies and intergovernmental organisations but also business owners, citizens, and individuals who have an essential role in developing rural ecotourism management.

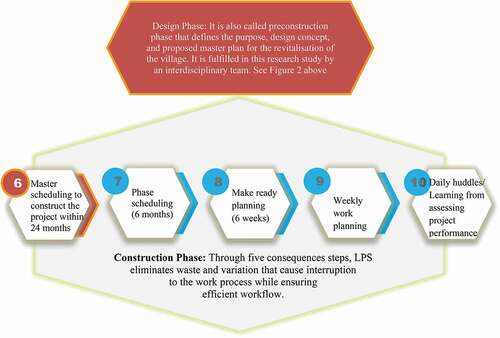

Revitlisation Management: shows a recommended flowchart relied on Lean Construction System (America, Citation2013a).

Priorities to conservation policies should include funding resources, tools, and conservation methods to sustain Qatar’s cultural heritage and ecological balance. We can only implement conservation policies of rural heritage if they are compatible and work with the national development plans like Qatar Vision 2030 and national policies, including rural development, environment, water, urbanisation, tourism, education, energy, economy, and administration. Also, Qatar should consider national agriculture and forestry and all related policies and large-scale planning decisions with the priority given to cultural conservation. This approach would ensure harmony among these policies while preserving local culture and sustainably growing the tourism sector.

Figure 12. Shows the revitalisation process flow (workstructuring). It is a lean construction flowchart that consists of a design phase and the construction phase. The former represents this research paper presented in . The latter, which is not part of this research paper, is the production planning that is defined in Lean Construction book, Unit 4, the Last Planner System (LPS) by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC of America) (America, Citation2013). The authors suggest it for QMA or Ashghal—Public Works Authority for the revitalisation of Tinbak

Declarations of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors. This work was supported by Qatar University Internal Grand, number QUCG-CENG-19/20-2 2019-2020.This publication was made possible by the NPRP grant (NPRP 12S-0304-190230) from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the author (s).

We would like to express our gratitude to Arch. Ibrahim Jaidah, Group CEO & Chief Architect of the Arab Engineering Bureau (AEB Qatar), for his advice and support with the required resources. Furthermore, we are grateful to the architects Hend AlNashar and Shaden Alriyabi for their enormous assistant in producing the figures and tables.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

M. Salim Ferwati

M. Salim Ferwati is an assistant professor at Qatar University. From 1995 to 1999, he worked as an expert in the architectural documentation of heritage buildings at Damascus University, where he documented over 30 historical buildings in Damascus, Syria. Recently his research is targeting the application of bio-mimicry in traditional architecture.

Sherine El-Menshawy

Sherine El-Menshawy is an Associate Professor at the Department of Humanities, History Program, Qatar University. Her area of specialisation is ancient history, archaeology, and cultural heritage.

Faisal Al Nuaimi is the Head of the Archaeology Department at QMA. He worked in the protection of world heritage that resulted in registering the site of the country’s Zubara on the UNESCO list.

Maha E A Mohamed is a Master student at the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University. Her research focuses on heritage buildings.

Sami Ferwati

Sami Ferwati is a graduate student at the Department of Geography and Planning, Toronto University, Canada. His interest is in urban planning and cultural geography.

Notes

1. All figures in the manuscript are produced by the authors except Figure 11.

2. The study is two-year grant research sponsored by Qatar University, starting from January 2019 to December 2020. The research team consisted of five interdisciplinary faculty members at Qatar University. The team included one faculty from the Departments of Architecture and Urban Planning, three faculties from Humanities Department (one from Geography Program, one from History Program, and one from Philosophy Program), one from Computer Science, and a consultant from Qatar Museum Authority and two research assistants.This paper illustrated only a plan that resulted from the 3D scanning of the 21 buildings in the village ().We interviewed the former villagers. The interviewees represented elderly, adult, and young people from both genders. The interview included 23 males and 19 females. We used oral-open-ended questionnaire technique. The questions were divided into three categories: the social aspects, the physical characteristics, and the environmental adaption. For example, we asked about the evolution of the village, their daily and occasional social activities and where it took place. We voice recorded the interviews as the only effective method in a group interview. The group interview was useful because it not only made everyone enjoyed talking with enthusiasm about their past but also they were reminding and supporting response of one another.

3. SWOT analysis relied on data collected from field trips, documentation of building conditions, urban context, and examination of the location map. One of the research team is a former inhabitant of the village. She made it possible to communicate with the former inhabits and discuss the result of the study, including the SWOT analysis. Additionally, we had feedback from Mr Faisal Al-Naimi, the research consultant from QMA.

4. The former residents of the heritage village of Tinbak settle nearby the village. Currently, the government owns the heritage village of Tinbak. The government intends to transfer the village into a touristic area. The primary stakeholder is the Qatar Museum Authority (QMA). Mr Faisal Al Nuami, the Head of the Archaeology Department at QMA is a collaborator and consultant for the study. The former villagers and the consultant provided the research team with their feedback about the suggested solution at all stages of the research workflow.

5. In the last 25 years, with the implementation of 3 and 4 Ss, similar functional consequences have taken place in Doha, Qatar. These developments are an indication of the possible success of revitalising Tinbak. For example, the most prominent project is Katara cultural village in Doha. The success of Katara is a result of coupling tradition and international architectural styles with a contemporary and diverse function such as open museum and open door seasonal festivals. In 2010, Katara was available for the public with few activities. It visitors are dominated by expatriates and tourists. Now it tripled in size with more diversified functions.

References

- Ahmad, Y. (2006). The scope and definitions of heritage: From tangible to intangible. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 12(3), 292–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250600604639

- America, A. of. (2013). Lean construction education program, unit 4: The last planner® system participant’s manual. Arlington, USA: The Associated General Contractors of America.

- Bramwell, B., Higham, J., Lane, B., & Miller, G. (2017). Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the journal of sustainable tourism: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1251689

- Brenner, N. (1999). Beyond state-centrism? Space, territoriality, and geographical scale in globalization studies. Theory and Society, 28(1), 39–78. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006996806674

- Brown, R. (1971). Ghost towns of the colorado rockies by brown, Robert L. USA: The Caxton Printers, Ltd. https://www.biblio.com/ghost-towns-of-the-colorado-by-brown-robert-l/work/66250

- Dall’Ara, G. (2015). Manuale dell’albergo diffuso: L’idea, la gestione, il marketing dell’ospitalità diffusa. F. Angeli.

- Dealtry, T. R. (1994). Dynamic SWOT analysis: Developer’s guide. Dynamic SWOT Associates.

- Diamantis, D. (2010). The concept of ecotourism: Evolution and trends. Current Issues in Tourism, 2, 93–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683509908667847

- Dincer, Y., & Dincer, I. (2005). Historical heritage—conservation—restoration in small towns and question of rural gentrification in Turkey. 1–7. ICOMOS. http://www.international.icomos.org/xian2005/papers/3-18.pdf

- East, M. (2017). Integrated approaches and interventions for the regeneration of abandoned towns in southern Italy. In G. Cairns, G. Artopoulos, & K. Day (Eds.), From conflict to inclusion in housing (Vol. 1, pp. 87–102). UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1xhr55k.12

- Emerson, R. W. (2017). The Role of Culture in Peace and Reconciliation. UNESCO, 2, 1–6. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/Emmanuel_Bombande_WANEP.pdf

- Epler Wood, M., Gatz, F., & Lindberg, K. (1991). The Ecotourism Society: An action agenda. In K. Kusler (Ed.), The 2nd international symposium: Ecotourism and resource conservation (pp. 75–79). Omnipress.

- Eres, Z. (2016). Mimari ve arkeolojik koruma kültürü üzerine yazılar. Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

- Ferwati, M. S. (2007). Head-turning situations: A street walk in the city of old damascus. archnet-ijar1(3), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v1i3.35

- Ferwati, M. S. (2010). Urban semiotic analysis: Spatial design and behavioural relations. VDM Verlag, Müller.

- Fyhri, A., Jacobsen, J. K. S., & Tømmervik, H. (2009). Tourists’ landscape perceptions and preferences in a Scandinavian coastal region. Landscape and Urban Planning, 91(4), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.01.002

- General Secretariat For Development Planning. (2018). Qatar national vision 2030. https://www.gco.gov.qa/en/about-qatar/national-vision2030/

- Giampiccoli, A., & Mtapuri, O. (2015). Tourism development in Qatar: Towards a diversification strategy beyond the conventional 3 Ss. African Journal of Hospitality Tourism and Leisure, 4(1), 13. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272497712

- Girard, L. F., & Nijkamp, P. (Eds.). (2016). Cultural tourism and sustainable local development. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315258720

- Global Ecovillage Network (GEN). (2014). Transformative social innovation theory. http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/resource-hub/global-ecovillage-network-gen

- Güler, K., & Kâhya, Y. (2019). Developing an approach for conservation of abandoned rural settlements in Turkey. A/Z : ITU Journal of Faculty of Architecture, 16(1), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.5505/itujfa.2019.48991

- Gürel, E. (2017). SWOT analysis: A theoretical review. Journal of International Social Research, 10(51), 994–1006. https://doi.org/10.17719/jisr.2017.1832

- Hashimoto, A., Telfer, D. J., & Telfer, S. (2020). Life beyond growth? Rural depopulation becoming the attraction in Nagoro, Japan’s scarecrow village. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1807556

- Hazbun, W. (2004). Globalisation, reterritorialisation and the political economy of tourism development in the middle east. Geopolitics, 9(2), 310–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040490442881

- ICOMOS. (1999). Heritageat at risk from tourism (International Cultural Tourism Charter Managing Tourism at Places of Cultural Significance). https://www.icomos.org/charters/tourism_e.pdf

- Ismagilova, G., Safiullin, L., & Gafurov, I. (2015). Using historical heritage as a factor in tourism development. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 188, 157–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.355

- Karppi, I., Kokkonen, M., & Lähteenmäki-Smith, K. (2001). SWOT-analysis as a basis for regional strategies. 84. Stockholm, Sweden: Nordic co-operation.

- Kiper, T. (2013). Role of ecotourism in sustainable development. In M. Ozyavuz (Ed.), Advances in landscape architecture(pp. 773–802). InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/55749

- Lanfranchi, M., Giannetto, C., G, M., & Paratore, S. G. (2009). Widespread hotel: An example of sustainable tourism development in rural areas (p. 7).

- Liu, C.-Z. (2010). Rural development and rural tourism in Taiwan. Asian Journal of Arts and Sciences, 1(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.30168/AJAS.201012.0004

- Lorimer, J. G. (1908). Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol. II. Geographical and statistical. British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers. https://www.qdl.qa/en/archive/81055/vdc_100023515711.0x000005

- Mansfeld, Y., & Winckler, O. (2007). The tourism industry as an alternative for the GCC oil-based rentier economies. Tourism Economics, 13(3), 333–360. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000007781497728

- Mao, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, H., Tang, W., & Kong, X. (2017). A spatial-territorial reorganization model of rural settlements based on graph theory and genetic optimization. Sustainability, 9(8), 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081370

- Nepravishta, F. (2018). The fragility of cultural heritage in the era of globalization: Skanderbeg square modernization. 1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328876515_THE_FRAGILITY_OF_CULTURAL_HERITAGE_IN_THE_ERA_OF_GLOBALIZATION_SKANDERBEG_SQUARE_MODERNIZATION

- Oakes, S. (2018). Changing places. DZS GRAFIK D.O.O.

- Powell, R. B., & Ham, S. H. (2008). Can Ecotourism Interpretation Really Lead to Pro-Conservation Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour? Evidence from the Galapagos Islands. Journal of Sustainable Tourism,16(4), 467–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802154223

- Qatar Climate. (2020). Qatar climate: Average weather, temperature, precipitation, best time. https://www.climatestotravel.com/climate/qatar

- QTA unveils ‘Qatar national tourism sector strategy 2030’. (2014, February 24). Marhaba Qatar. https://www.marhaba.qa/qta-unveils-qatar-national-tourism-sector-strategy-2030/

- Reichert-Schick, A. (2018). The village as a hotel. Tourism-oriented revitalisation of rural settlements: A good practice concept for European peripheries? In Grabski-Kieron, U., Mose, I., ReichertSchick, A., Steinführer, A., (eds.,), European Rural Peripheries Revalued: Governance, Actors, Impacts(pp. 198–228). Berlin, German: LIT Verlag Münster.

- Roberts, L., & Hall, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). Rural tourism and recreation: Principles to practice. CABI Pub.

- Ross, S., & Wall, G. (1999). Ecotourism: Towards congruence between theory and practice. Elsevier Science Ltd, 20(1), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00098-3

- Rushi, B. (2016). Cultural heritage: Vol. Value (ethics). https://www.scribd.com/document/326384117/chapter-1-docx

- Sani, M. (2020). Making Heritage Accessible: Museums, Communities and Participation (Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, pp. 1–7). NEMO Network of European Museum Organisations, Istituto Beni Culturali Regione Emilia Romagna, Italy. https://rm.coe.int/faro-convention-topical-series-article-5-making-heritage-accessible-mu/16808ae097

- Sharpley, R. (2006). Ecotourism: A consumption perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 5(1–2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040608668444

- Short, J. R. (2004). Global dimensions: Space, place and the contemporary world. Reaktion Books.

- Steinberg, F. (1996). Conservation and rehabilitation of urban heritage in developing countries. Habitat International, 20(3), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(96)00012-4

- Swarbrooke, J. (1999). Sustainable tourism management. CABI.

- Tsaur, S.-H., Lin, Y.-C., & Lin, J.-H. (2006). Evaluating ecotourism sustainability from the integrated perspective of resource, community and tourism. Tourism Management, 27(4), 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.02.006

- UNESCO. (2013). Earthen architecture in today’s world: Proceedings of the UNESCO international colloquium on the conservation of world heritage earthen architecture : UNESCO Headquarters, Room XI – Paris, France, 17-18 December 2012 = L’architecture de terre dans le monde d’aujourd’hui : Actes du colloque international de l’UNESCO sur la conservation de l’architecture de terre du patrimoine mondial : Siège de l’UNESCO, salle XI – Paris, France, 17–18 décembre 2012. http://whc.unesco.org/en/series/36/

- Walters, B. B. (2017). Explaining rural land use change and reforestation: A causal-historical approach. Land Use Policy, 67, 608–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.008

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (Ed.). (2020). AlUla framework for inclusive community development through tourism. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284422159

- Yachin, J. M., & Ioannides, D. (2020). “Making do” in rural tourism: The resourcing behaviour of tourism micro-firms. Journal of Sustainable Tourism,28(7), 1003–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1715993

- Zhao, X. (2020). Living heritage and place revitalisation: A study of place identity of Lili, a rural historic canal town in China [PhD thesis]. The University of Queensland https://doi.org/10.14264/uql.2020.803

- Ziffer, K. A. (1989). Ecotourism: The uneasy alliance. [Mexico]: Conservation International.