ABSTRACT

Vote-buying is a contentious issue in contemporary discourse on the sustainability of democratic development in Nigeria. This menace is gradually crippling electoral processes and undermining the efforts of the electoral umpire in conducting competitive, free, fair, and credible elections for the sustenance of democratic development in Nigeria. The study, therefore, investigates the effects of vote-buying on the sustainability of democratic development and good governance in Nigeria. It argues that vote-buying compromises the well-being of the populace by entrenching bad governance and poor service delivery. The study adopts reciprocal determinism theory to illustrate how the political environment and bad governance are stimuli to consolidating the commercialisation of Nigerian electoral processes. The study adopts the documentary method for gathering data from secondary sources and recommends institutionalisation of a strong electoral management body to enforce a stiff penalty for commercialisation of the electoral system in Nigeria.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Election is one of the major elements of democracy through which individuals and political parties acquire power. The acquisition of power is not an end in itself but a means towards an end, where such end is about the socio-economic development of the people for whom the elected hold power in trust. The vitiation of this process is the foundation for underdevelopment in most emerging economies such as Nigeria. The Nigerian electoral process has recently begun to experience vote-buying; an exchange of ballot paper for monetary gains that occur between politicians and the electorates. Suffocated by poverty, illiteracy, and sometimes greed, some Nigerian electorates mortgage good governance and accountability by selling their votes to corrupt politicians that are willing to exploit the conditions of the masses. This ultimately results in bad governance, inept leadership, weak institutional framework, and perennial development deficit and conflicts in Nigeria.

1. Introduction

Vote-buying is the transactional process through which voters offer their votes for sale and political parties or public office aspirants or their agents’ bargain to buy the votes from the sellers. It is synonymous with selling and buying goods and services in an open market on agreed prices. Where competition is very high, the process seems to be auction sales whereby the voters sell to the highest bidder. Modern scholars of social sciences and humanities trace the historical origin of election and electoral processes in Nigeria with emphasis on its fraught with vote-buying (cash-and-carry democracy), and other electoral malfeasances, ethnic chauvinism, religious extremism, and politically motivated violence and killings (Onuoha & Okafor, Citation2020; Adigun, Citation2019; Olaniyan, Citation2020; Amao, Citation2020; Ojo & Onuoha, n.d; Onapajo et al., Citation2015; Olorunmola, Citation2016.). Onapajo et al. stress that “Nigeria’s electoral process has always been known for its chaotic nature and at the heart of this quagmire, is the predominance of vote buying, a phenomenon which arguably reflects the nature of politics and election” (2015, p. 2). Amao (Citation2020) corroborates this assertion as he stresses that the electoral process in Nigeria has frequently been identified for its corrupt, violent, and chaotic tendencies characterised by the utilisation of thugs, maiming of political opponents by those seeking electoral positions through electoral fraud. It is therefore not astonishing that virtually all the elections organised in Nigeria were marred by controversies, with their processes and outcomes facing crisis of integrity, credibility, and legitimacy. According to Onuoha and Okafor (Citation2020), vote-buying, in recent time, has risen in proportion, in scope, and sophistication as videos and images uncover the illegal practice of distributing money, materials, and other incentives among the electorates by political aspirants, party agents in order to lure voters to vote for their candidates. Onwudiwe and Berwind-Dart (Citation2010, p. 1) opine that

While Africa’s largest democracy prepares for the polls, serious questions remain about Nigeria’s capacity and political will to conduct free, fair and peaceful elections. Since independence in 1960, violence and myriad irregularities have persistently marred the process of electing the country’s leaders, Nigerian politicians have become habituated to fraud, corruption, intimidation and violence, as if they consider these the necessary weapons of political winners.

Olorunmola (Citation2016) argues that money is considered a crucial factor for political parties to run their affairs during and between elections. Unregulated utilisation of resources, private or public, for political activities is capable of reversing the ethics, practices, and spNDIt of democracy; it confers undue advantages and improperly changes choice to electorates. “The 2015 general election was one of the most heavily monetised election which saw the two leading candidates tried to outspend each other. Vote buying was carried out in 2015 and 2019 elections with brazenness and audacity, in some cases with electoral officials and security agents” (Adigun, Citation2019. p. 21). The cases of Olisa Metuh diverting N400 million and US$2 million originally meant for national security to vote-buying (Yahaya, Citation2020); Sambo Dasuki misusing US$2.1 billion and N19.4 billion initially meant for the purchase of arms for the army to sponsor President Jonathan’s re-election bid through vote-buying (NnochNDI, Citation2016); and Diezani Alison-Madueke surreptitiously disbursed US$20 billion to the following persons to influence 2015 elections outcomes: INEC officials $115 million, Fidelity Bank officials (Martin Izuogbe & Mrs Gesil Khan)—N185,842,000, Fidelia Omoile—Electoral Officer N112,480,000, Uluochi Obi-Brown, INEC Administrative Secretary—N111,500,000, Edem Okon Effang, former INEC Deputy Director—N241,127,000, and Immaculata Asuquo, INEC Head of Voter Education—N241,127,000 (Alli, Citation2016); Christian Nwosu, INEC official—N30 million, Musiliu Obanikoro, former Minister of State for defense—N4.7 billion, Yisa Adedoyin and Tijani Bashir—N264,880,000, Dele Belgore—N450 million. In Kwara State, Resident Asst. Inspector-General of Police—N1 million, Kwara State Commissioner of Police—N10 million, Deputy Commissioner of Police in-charge of operations—N2 million, Asst. Commissioner of Police in-charge of operations and administration—N1 million, Resident Electoral Commissioner—N10 million, Administrative Secretary—N5 million. INEC Head of Department (Operations) and subordinates—N5 million, rank and file officers N2 million. Officer in-charge of Mobile Police and subordinates—N7 million, the 2i/c mobile police and subordinates—N10 million, Director of State Security Services and subordinates—N2.5 million, the military personnel in Kwara State—N50 million; and paramilitary agencies got N20 million, all meant to pervert elections outcomes (Alli, Citation2016; Kayode-Adedeji, Citation2015; Onyekwere, Citation2017). Appendix A1 discloses detailed narratives of the unlawful transactions.

These electoral compromises, in most cases, have derailed the course of democracies and led to loss of lives and properties, political instability, underdevelopment, poverty, and bad governance. The vote-buying syndrome, as one of the major drivers of electoral fraud, is not a new phenomenon in Nigeria’s political landscape nor is it peculiar to the country. It is an aged-long global political plague that has been ruining the development efforts and consolidation of democratic politics. It transcends the African continent to other parts of the world. For instance, vote-buying, as a campaign strategy to lure voters, is prevalent in the Philippine, Britain, Pakistan, India, the United States, and some other European countries. Other countries that practice it during elections are Nicaragua, Argentina, Taiwan, and Lebanon. In Africa, vote-buying is very prevalent in Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, Sao Tome Principe, Rwanda, Equatorial Guinea, Burundi, Uganda, Liberia, Togo, Sierra Leone, Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, etc. (Ovwasa, Citation2013; Baidoo et al., Citation2018; Onuoha & Ojo, Citation2018; Romero & Regalado, 2019).

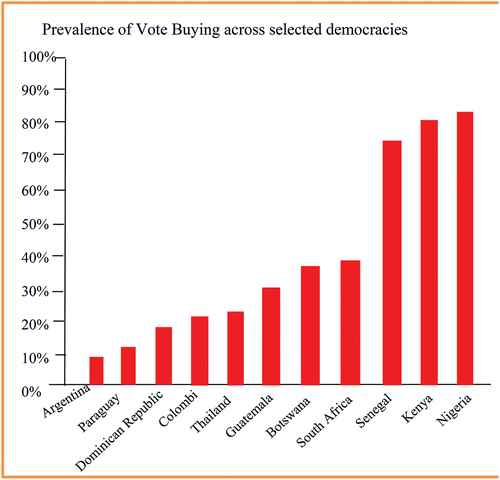

Canare et al. (Citation2018) carried out empNDIcal study on vote-buying in the Philippines to investigate the patterns of vote-buying among poor voters in Metro Manila. The study revealed that although vote-buying is prevalent in the Philippines, but it is unrestrained in most developing democracies. Vote-buying incidences are frequent among African countries than in Latin American nations as illustrated in . The study harps on the consequences of vote-buying: it causes huge costs to society, weakens accountability in governance, and impedes institutional growth required for democracy. Voters in the Philippines see election periods as viable opportunities for making money. Aspirants offer free medical care, scholarships, food, and subsidisation of funeral bills to voters (Felongco, Citation2019; Schaffer, 2002). Vote-buying is correlated with high-profile corruption and inefficiency in government institutions. A similar study also disclosed evidence of votes selling being prevalent among poor voters in Argentina, Egypt, and Nigeria (Stokes, Citation2005).

Figure 1. Prevalence of vote-buying across selected democracies.Source: Canare et al, Citation2018.

Nicaragua’s municipal elections in 2008 recorded incidence of vote-buying, whereby food stamps, rice, beans, and 25,000 stores were distributed to eligible voters to earn their votes (Gonzalez-Ocantos et. al., Citation2010). In India, voting was invalidated in a constituency in the southern state of Tamil Nadu in the 2019 general elections where the 100 million rupees meant for vote-buying was seized. The rate of vote-buying per family was estimated to range between 75 and 100 US$ (Aljazeera, Citation2019; Bari, Citation2018). Sanni’s (Citation2019) study revealed that the prevalence of vote-buying and perception that votes were actually purchased from voters placed south–south zone highest with 24% prevalence and (76%) perception of vote-buying in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections; north–west 23% (53%); north–central 21% (64%); southeast 19% (73%); southwest 19% (71%); and northeast 18% (52%), respectively. According to Jesten and Justesen (Citation2014), vote-buying has emerged, with the spread of democracy, as an integral part of election campaign in the developing world. In Pakistan, election period is perceived as an opportunity to demand for their own electoral benevolence which includes money, digging wells to provide water, distribution of solar panels, paving of streets, fans, donation of huge money to shrine, mosques, seminaries, welfare organisations, other religious institutions, and bankrolling faithfuls to Mecca for pilgrimage (Ali, Citation2018; Kramon, Citation2016)

In a similar empNDIcal study carried out on vote-buying in Kenya, Kramon (Citation2009) disclosed that vote-buying is a ubiquitous phenomenon, as he argues that from the Roman Republic to nineteenth-century Britain and the United States to such newer democracies as the Philippines and Argentina, and to such African countries as Sao Tome Principe and Nigeria, the practice of vote-buying has been commonplace in political campaigns. It is evident that the nineteenth-century laws providing for the secret ballot in both the United States and Great Britain were largely accountable for the reduction of vote-buying in those countries.

The degree of its prevalence and escalation in Nigeria is rooted in elites’ politics and was more pronounced in 2011, 2015, and 2019 general elections. If the menace is left unchecked, it foreshadows doom for democracy in Nigeria, and Africa in general. Vote-buying appears to be a contentious issue amongst scholars in contemporary discourse on the sustainability of democratic development and good governance in developing countries. As underscored by some social science scholars, such as Sarkariyau et al. (Citation2015) and Onapajo et al. (Citation2015), since the inception of the fourth republic’s experimental democracy, 1999–2019, Nigeria has experienced electoral violence characterised by instability, insecurity of lives and properties, election irregularities, and organised arsons occasioned by bad governance and inept leadership, with its attendant ripple effects on public service delivery and standard of living of the masses. These social menaces are gradually crippling electoral processes and undermining the efforts of Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and other stakeholders in conducting unbiased competitive, free, fair, and credible elections in accord with the yearnings of voters for transparent, reliable, and acceptable elections (Abba & Babalola, Citation2017; Adekoya, Citation2019; Olaniyan, Citation2020; Owen, Citation2013).

The weak regulation of political parties and politicians by the INEC (as the regulatory agency) in an incoherent political environment and the abysmal performance of government in the provision of infrastructural facilities are stimuli to vote-trading (selling and buying of votes) in consolidating the commercialisation of electoral processes. The unbridled display of abuse of power and uncontainable spread of wealth by these unguarded political elites, whose activities do not align with the Electoral Act 2010 (as amended), stimulates feeble voters to patronise them in selling/mortgaging their voting rights. The authors express concern about election period which is supposed to be an appraisal season to assess the government and politicians’ performance vis-a-vis the manifestoes and campaign promises is rather perceived by gullible voters as a time for “lucrative commercial venture”, a period of “harvest”, instead of being a time to hold government and politicians accountable for stewardship so as to make rational decisions on voting choice.

The act of vote-buying is unlawful in Nigeria; and the “legalisation” of the illegalities being perpetrated by political elites is worrisome and unacceptable in the electoral processes only if the electoral management body is vibrant, independent, competent, and capable to regulate the activities of the political class. One of the major factors that trigger off vote-selling among eligible voters is the overwhelming gap in leadership and character of the state. It is a political strategy being utilised by political elites to weaken and deplete votes in areas perceived to be opponents’ strongholds. Vote-buying (political bait) is being applied to attract voters to use their civic powers against strong opposition contenders during elections (Khemani, Citation2015; Onapajo et al., Citation2015; Olaniyan, Citation2020). Looking at the pervasive nature of vote-buying in many electoral regimes, the nexus between vote-buying and behaviour of teeming electorates, specifically in the context of a voluntary secret ballot, remains unpredictable. If the voting procedure is secret and voluntary, vote-buying would hardly be possible to have an impact on the voter’s behaviour. The voter is at liberty to vote privately in accord with the dictates of his discretion, without recourse to the tacit nod with the vote-buyer. The voting choice of the voter is concealed and protected by the secrecy of the act (Kramon, Citation2009; Ojo, Citation2020). Yakobson (Citation1995, p. 4) cited a Roman politician and a great thinker Cicero to have complained that “private voting allowed a man to wear a smooth brow which cloaks the secrets of his heart, and leaves him free to act as he chooses without recourse to any promise he may be asked to give”.

The act of vote-selling/-buying is largely being attributed to translucent manifestations of incompetence and unacceptability of unsalable aspirants in elections under normal rationale decision-making of voters; and partly on a high level of poverty rate among the masses, unemployment, illiteracy, and absence of old people’s home where the most vulnerable segments of the society (the pensioners, jobless aged persons, physically challenged individuals, etc.) could be catered for. Poor parliamentary representations and infrastructural deficits in governance, and harsh economic conditions are some of the stimuli that adversely influenced the electorates to reciprocate on voting choice, but prompted political class to resort to vote-buying as a viable means of enticing unwilling poverty-ridden electorates who, unfortunately (out-of-acute-hunger), prefer having greater appealing incentives in the short-term socio-economic benefits the situation provides to waiting for unrealistic long-term elusive campaign promises that are merely made to catch votes (Heath & Tillin, Citation2017; Hicken et al., Citation2015; Onapajo & Babalola, Citation2020). Desposato (Citation2007, p. 104) succinctly notes:

Poor voters, on average, should have higher utility for immediate private goods than for delayed public goods. Moreover, unless a voter has an alternative source of income and simply did not need the incentive, it is unlikely that poor voters will, therefore, be able to resist vote-buying incentives.

Money politics plays destructive roles by truncating and frustrating the collaborative synergies of the electoral umpires, the INEC, civil society organisations, and international stakeholders in consolidating and developing genuine participatory democracy in Nigeria. Money plays a dominant role in the crude canvass for votes, and the poor frustratingly patronise corrupt politicians to empower themselves for at least a day’s meal. It becomes incredibly worrisome the conspicuous absence of INEC’s statutory functions to control and regulate election expenses incurred by individual candidates and political parties to curb the excesses of vote-buying. In the face of an enormous amount of money directed specifically to achieving victory willy-nilly, the will of the electorates cannot locate expression and flourish in a politically polluted environment. “Elective offices become mere commodities to be purchased by the highest bidder, and those who invest merely see it as an avenue to recoup and make a profit. Politics becomes business, and the business of politics becomes simply to divert public funds from the essential needs of the people for real development in their lives” (Sarkariyau et al., Citation2015, p. 5). Nwagwu (Citation2016) observes that money determines who vies for election in Nigeria than allowing potentially salable candidates with credible credentials to compete on competence and capabilities to serve. Voters are easily pulled around by the nose with material enticement. They vote according to the dictates of the vote-buyer.

The essence of elections competition is to provide the people the opportunity to participate in all electoral processes to elect their leaders. Therefore, elections periods present ample chances for performance evaluation of the governments’ programmes or activities (at all levels) centred on degree of accomplishment of their campaign promises on the security of lives and properties, education, economy, agriculture, and public health delivery, the standard of living, infrastructural facilities, and the war against corruption, poverty, and unemployment. Specifically, elections are cardinal process through which electorates legitimately allocate political powers to aspirants of elective public offices (Abba & Babalola, Citation2017; Amao, Citation2020; Baidoo et al., Citation2018; Mustopha & Omar, Citation2020). The abysmal performance of the government, the parliamentarians, and the political parties is the environment that influences the behaviour of eligible voters in elections. Elections are meaningful only when the people are given unlimited freedom to vote massively for candidates of their choice, and their votes count to determine the exact winners who would authoritatively assume the responsibilities to administer the affairs of the state within a time frame. The elected members through free and fair process would be responsible to the electorates in meeting their needs and aspirations. Perpetrators of vote-buying impudently distort and stunt the fundamental precepts of democracy and rules and regulations of elections with its ripple effects on governance, leadership quality, and public service delivery capacity. Bad governance and insufficient institutional performance indicators arouse voters to patronise vote-buyers and by extension, portraying the loss of confidence in Nigeria polity (Heath & Tillin, Citation2017). Nevertheless, several scholars have found evidence of poverty, illiteracy, unemployment, and vulnerability of poor voters that make them susceptible target for vote-buying. Scholars have given scanty attention to the damages vote-buying has occasioned in Nigeria. It is therefore instructive to underscore the latent consequences of inept leadership and weak institutional frameworks caused by vote-trading, which has heightened insecurity of lives and properties, worsened the living standard of vulnerable groups, and tilting Nigeria towards disintegration.

On the strength of the above, an interrogation of the factors militating against the integrity of elections and good democratic governance in Nigeria becomes imperative. Vote-buying in the 2015 and 2019 general elections was frighteningly sophisticated, brazenly enormous, and it calls for radical reform of the subsisting Electoral Act 2010 to halt the trend of lawlessness and foster sanctity of elections.

2. Methodology

This study is a qualitative research which focused on the secondary method of eliciting data from existing sources. The documentary method anchors on descriptive analysis of documents containing essential data relating to the phenomenon under investigation. Payne and Payne (as cited in Mogalakwe, Citation2006, p. 221) “describe the documentary method as the techniques used to categorise, investigate, interpret and identify the limitations of physical sources, most commonly written documents whether in the private or public domain”. Mogalakwe (Citation2006, p. 221) argues that “the use of documentary methods refers to the analysis of documents that contain information about the phenomenon under study”. This type of research approach has mistakenly been viewed by social scientists as the domination of professional historians, librarians, and information science specialists. Umar (Citation2016, p. 127) opines that some social scientists “often project the qualitative methods as a worthless pursuit, incapable of aiding the understanding of social phenomena let alone prescribing for its resolution or amelioration”. Accordingly, Burnham et al. (Citation2004, p. 168) argue that “it is somewhat surprising that most social research methods texts fail to give documentary materials more than a passing reference”.

Therefore, the apparent neglect of the significance and seeming underutilisation does not translate qualitative research in social sciences to less rigorous methods; researchers demonstrate absolute trust and plain proof that the method is as well scientific that needs rigorous adherence to research protocol. Qualitative inquiry applies diverse philosophical suppositions; strategies of inquNDIes; and methods of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. A qualitative method emphasised strictly on the qualities of entities, processes, and meanings that cannot be experimentally evaluated or measured in terms of quantity, amount, intensity, or frequency. The principal aim of descriptive research is to project the phenomenon under investigation and elaborate on its characteristics. In descriptive research, information collected qualitatively may be analysed quantitatively, making use of frequencies, percentages, averages, or other statistical analyses to establish relationships (Nassaji, Citation2015; Umar, Citation2016).

The documentary method of data collection has inherent flexibility in information gathering through the utilisation of government records, public and school libraries, reports on events or personal accounts on experiential incidents, retrieval of facts and figures from statistical records on social issues or the archival sources, journals, literary books, the media, and internet sources. The importance of the documentary method of data generation has been succinctly highlighted by Johnson and Joslyn (Citation1995) in the outline of the merits of the method that it provides. It affords researchers the process of smooth access to phenomena that may prove difficult or impossible to collect through physical contact, either because the event happened in the past or to objects that are geographically located in distant places; the use of information collected from the archives is normally important because raw data are often non-reactive. That means the researchers and the data stored or preserved are, in most instances, unplanned for further future research objectives or generating hypotheses with the intent that the outcome of the work would be used for the research goal. However, data preservation does not at all times remain dormant. Record preservers are not likely to create and keep information that reveals unlawful or immoral deeds; or that reveal greed, stupidity, or other discrediting qualities; or even in some instances, that have security implications that are embarrassing to them, their friends, or their superiors; qualitative method creates easy access to information or records that have been in existence long enough to allow analyses of a political phenomenon over time; having documented record always allows researchers to enlarge sample size above what would have been practicable through either interview, questionnaire or other forms of direct observation; and essentially, qualitative method of data generation often saves much time and resources for the researcher. It accelerates consultation of government printed records, reference materials, computerised data, and research institute reports than it is to gather information by the researcher through the survey methods.

The qualitative method was used to establish the gaps in the literature that needed to be filled through a review of a plethora of existing literature. The study exposed the researchers to a wide stream of literature on vote-buying. The study adopted a qualitative descriptive method of data analysis to analyse the data collected. In formulating the research problem and analysing the data generated, the researchers used descriptive statistics obtained largely from Nigeria’s election management body, the INEC, Nigeria’s Electoral Act, and print media such as ThisDay. Others include reports from National Democratic Institute (NDI), International Republican Institute (NDI), Nigerian International Election Observation, and plethora of existing body of knowledge from extant literature which provided the authors with the benefit of learning from the findings of other related research. Qualitative researchers are keen in acquNDIng understanding and insights of the problems under investigation. Also, 2010 Electoral Act on regulation of party campaign expenses, party primaries, and monitoring of party activities were reviewed. The utilisation of multiple sources to assist in elaborating the campaign funding and vote-trading of the two dominant parties in Nigeria was intended to heighten the reliability of data. Due to the illegality of political parties’ activities, vote-buying and faceless donors during campaign fundraising are mostly surreptitiously executed without records. This creates limitations in obtaining donors’ names and exact sum donated. The data generated were subjected to comparison with other relevant publications to establish the validity of the research results. The usefulness of the exercise is buttressed as Burnham et al. (Citation2004, p. 114) argue in favour of the method thus:

Descriptive statistics is a range of basic statistical tools for describing data. The main appeal of descriptive statistics is that it is a powerful and economical way of measuring, analysing and presenting political phenomena such as voting behavior, political participation, and social and political attitudes generally. Description of political attitudes is essential not only because it is of interest in itself, but also because it is the basis for explanations and inference when, as is usually the case, a piece of research only includes a sample rather than an entire population.

The methodology rests on this premise. The next section is the theoretical framework of analysis.

3. Theoretical framework

Reciprocal determinism theory is adopted as the theoretical framework of analysis for the study. Reciprocal determinism postulates that the individual’s behaviour influences and is being influenced by both the personal characteristics and the social world. The theory is a model built around three major characteristics that influence behaviour—the environment, the individual, and the behaviour. The model explains the interwoven nature of the three factors which made them be interdependently working together to produce reflective responses. As the environment influences individual behaviour, the individual’s reactions as well as influence the environment. Thus, the theory investigates the part our behaviour plays in the environment. This theory was firstly propounded by a psychologist, Albert Bandura (Singh, Citation2018). Other proponents that expounded on the theory were Judith Rich Harris (1998), Akoul Gregory M. (1998), and Larry J. Siegal (n.d.).

Akoul gave details on the earlier propositions of a child who implies that children were inactive receivers of environmental influences, which conveyed that the children were easily molded or shaped in whatsoever method the parents or school teachers and other caregivers select to work. The theory of reciprocal determinism holds the view that infants display more practical and interactive roles in the environment as the environment influences them. With difficulty would they react as an effect of learned associations or reinforcements; considering that their characteristics, feelings, thoughts, and behaviours impact how they interact with and respond to the environment (Cherry, Citation2018; Singh, Citation2018).

The focus of this theory is the assumption that a relationship exists between the environment and behaviour of persons, in which the environment influences the behaviour of the people. In other words, the environmental factors which produce very poor conduct of elected public office holders, abysmal performance of the government in power to provide good governance, weak public service delivery capacity, absence of infrastructural facilities and welfare of the public which is paramount in governance, poor legislation and a disservice to the people, the ineptitude of government functionaries, and individual experiences of voters fanned their sense of judgement to react the way they considered beneficial. For instance, the lack of genuine electoral processes, transparency, and accountability in governance formed the mindset of voters to respond to the environment by selling their votes in exchange for money and/or materials. Reciprocal determinism translates to how the environment produces effects on individual characteristics. Cherry (Citation2018, p. 2) stresses:

The environment component is made up of the physical surroundings around the individual that contain potentially reinforcing stimuli, including people who are present (or absent). The environment influences the intensity and frequency of the behavior, just as the behavior itself can have an impact on the environment. On the other hand, the individual component includes all the characteristics that have been rewarded in the past. Personality and cognitive factors play an important part in how a person behaves, including all of the individual’s expectations, beliefs, and unique personality characteristics.

Vote-buying as a cause of electoral irregularities in Nigeria before and during election periods serves to arouse stimulus or environmental influence on the voters; and vote-selling is a response to the stimulus on the environment. Reciprocal determinism theory argues that vote-buying is a symbol of a huge gap in leadership and bad governance; while vote-selling is a reciprocal behaviour of voters to the environment.

Bandura’s theory has demonstrated a vital paradigm shift from the behavioural perspective to a social-cognitive approach to understanding behaviour. Behaviourists believed that the environment wholly influences individual behaviour, but Bandura appreciated the relevance of the bidirectional relationship between individuals, their behaviours, and the environment. To a large extent, it reveals that while individuals are affected by their personal experiences in their environment, they as well have the collective power to effect a change on their situation and circumstances through personal sacrifices and problem-solving behaviours. This theory takes us to the next section on the manifestation of vote-buying in election periods.

3.1. Manifestation of vote-buying in election periods

Vote-buying has different connotations to different people or countries depending on the people’s history, culture, and political experience, and election models. The concept of vote-buying does not have a conventional single universally accepted definition. Etzioni-Halevy (Citation1989, p. 287) sees the concept as “the exchange of private material benefits for political support”; while Bryan and Baer (Citation2005, p. 4) conceptualised vote-buying as “the use of money and direct benefits to influence voters”. The two definitions emphatically stressed the objective of vote-buying which is to earn direct socio-economic benefits for political support of voters in return. The basic underscore of the abstraction “vote-buying” is the emphasis of exchanging voters’ political rights for material benefits. Contextually, the material benefits and political support are more significant and a centrepiece of the objective of vote-buying. Nurdin (Citation2014, p. 34) notes:

The aspect of exchange between the material benefit and political support is more significant than the objective of the vote-buying. In a money politics context, the financial condition of the voters is considered to be one of the crucial factors. The voters accept the vote-buying practice maybe because they do need the fund.

The repulsive manifestation of money politics in Nigeria’s political landscape is a premeditated infringement of subsisting electoral laws. The apparent dearth of skilful utilisation of contending political ideologies and problem-solving manifestoes by politicians to appeal to voters’ conscience, and convincingly influence the political behaviour of electorates in addressing perilous social issues that would touch their individuals or collective lives and interests creates a gap for vote-buying. Political elites are bereft of innovative political knowledge, and often seem to be naïve of their political parties’ programmes, course of direction, and at variance with raging socio-economic and political debates to foster good governance; hence the resort to mudslinging, non-issue-based campaigns, hate speeches, and inflammable utterances. These unsalable aspirants or political parties have no viable appealing options to anchor or hinge on their inordinate ambitions than vote-buying and application of other electoral frauds (Sarkariyau et al., Citation2015).

The primary contributory factors to vote-buying in Nigeria are poverty, unemployment, and illiteracy, and worsened by galloping inflation. The poor are the most vulnerable segment of the population who, on seeing money or other enticing benefits, do not reason or reflect on the future consequences of the unsolicited “gestures”, do not hesitate to grab the gifts for immediate satisfaction of social needs, no matter how small the benefits may be. These short-sighted decisions of voters due to a low level of education, hunger, and idleness caused mortgaging of their future for miserable lives, robotic manipulations, and intimidations in the hands of political adventurists. Worst still, the prevalent impact of the economic recession and intrinsic inflation rate in the country have disvalued the possessions of the impoverished with low purchasing powers and rubbished the standard of living of the poor the more, thereby projecting vote-buying to flourish in Nigeria polity endlessly. This situation calls for a radical reappraisal of electoral education and sensitisation of voters to create sufficient political awareness and emancipate the downtrodden from the clutches of poverty and illiteracy (Khemani, Citation2015; Nwagwu, Citation2016; Ovwasa, Citation2013; Sarkariyau et al., Citation2015).

Besides, the political cynicism inherent in the system manifested itself by frustration and disillusionment of the electorates, on the one hand, and distrust of the political class, associating public office holders as innate corrupt elements, on the other. This impression has given credence for voters to succumb to the sustainability and spread of money politics and vote-buying as a disease without elixir. The perception of voters about public office holders, whether elected or appointed, as self-centred, incompetent, and corrupt “representatives” of the governed is being engaged to justify the acceptance of money and/or materials as a condition to vote for the giver. Politics in Nigeria has been described as a dishonourable enterprise by electorates because of the inability of government, legislatures, and political parties to keep to terms with the fulfilment of the campaign promises, disgraceful convictions and imprisonments of politicians for being guilty of criminal offences, and these indices are viewed as an absolute betrayal of public trust reposed on them. Furthermore, the nature of politics in Nigeria seems to fan money politics. The zero-sum game (winner-takes-all and loser-loses-all) pattern of politics places exceptionally high premium on power, and the institutional mechanism for moderating political competitions is completely lacking. Thus, political competition assumes the character of warfare (do-or-die affair) in Nigeria (Ake, Citation1996; Sarkariyau et al., Citation2015). The next section is vote-buying in the 2015 elections.

3.2. Vote-buying in 2015 general elections and money politics in Nigeria

The essence of vote-buying in 2015 general elections is to influence the voting behaviour of electorates and to swing the political pendulum towards the buyers’ favour and actualisation of the ambition to secure victory in the elections. Vote-buying increases the election enthusiasm and draws massive voter turnout for the money and/or material benefits. This large turnout of voters for incentives has a significant effect on voting behaviour (Nurdin, Citation2014), not necessarily to vote but to collect the benefits and may abscond voting. Money is a dominant, determinant factor in Nigeria’s politics. The poor are vulnerable segment of voters easily predisposed to be victimised, intimidated, and manipulated by vote-buying because their limited means makes them susceptible to material inducements, including offers of basic commodities or modest amounts of money or job procurements (Abba & Babalola, Citation2017; Onapajo & Babalola, Citation2020). Baidoo et al. (Citation2018, p. 3) opine:

Theoretical perspectives have identified three dominant arguments to explain the foundations of vote-buying in elections. First it is argued that socio-economic factors, especially poverty, unemployment and illiteracy play a major role in promoting the market for votes in democracies. Second, it is argued that the voting methods in a particular electoral system may also guarantee the predominance of vote-buying during elections. The third explanation is predicated upon the belief that vote-buying is a product of the nature of partisanship and party organisation in a particular state.

Votes are not bought without considering the category or group of voters the person belongs. Three categories of voters have been identified to include core supporters, swing voters, and opposition backers (Baidoo et al., Citation2018). These three categories are the focus points in every election; they are the target population during vote-buying. Vote-buying proposal often focused on either electoral choices or electoral participation with the intent to convince persons to vote in certain ways, or not to vote in the first place. Political parties generate monetary and non-monetary incentives to induce the poor and less educated voters during elections. illustrates the characteristics of voters and their utilisation in elections. From the group (poor and less educated), swing voters and core supporters are sieved out as the positive turnout buying. The outcome of the positive turnout buying increases votes for the distributing party and places it at a vantage for victory. The second segment of the poor and less educated voters is filtered out of the population as opposition supporters whose intent and purpose is to execute negative vote-buying to reduce votes for the opposition.

Figure 2. Conceptual review of vote-buying.Source: Schaffer and Schedler (Citation2005).

Nigeria has made impressive breakthrough in improvement of the legal framework by consistent review of the 2002, 2006, and 2010 Electoral Act to guide against vote-buying. The identified inconsistencies and potential loopholes in course of application of the law have been addressed by amending the subsisting Act. For instance, Section 90(1) of the Act empowers the Commission to place limitation on the amount of money or other assets, which a person or group of individuals can contribute to a political party. Also, Section 91(9) of the 2010 Act stipulates that “no individual or other entity shall donate more than one million naira to any candidate or political party”.

In contraction, “Section 93(3) (b) gives political parties the leverage to receive limitless sums above the threshold, provided it can identify the source of the money or other contribution to the Commission” (Nwagwu, Citation2016, p. 79). Similarly, Section 91(2)–(7) provides 1-billion-naira maximum expenses a candidate would incur on a presidential election; maximum of 200 million naira to be incurred by each gubernatorial candidate at election; the maximum expenses each candidate shall incur in respect of National Assembly election shall be 40 million naira for each senatorial aspirant, while House of Representatives aspirants shall each expend 20 million naira. The State Assembly election expenses shall be 10 million naira per candidate; while candidates for chairmanship election in an Area Council shall incur 10 million naira; and in the case of candidates for councillorship election in an Area Council, 1 million naira shall be the maximum expenses to be incurred (Federal Republic of Nigeria, Citation2010).

Besides, Subsection 91(10) stipulates that any candidate who wittingly exceeds the limitations prescribed by the electoral law commits an offence, and if convicted, the culprit shall be liable to sanctions as illustrated in .

Table 1. Restrictions and sanctions on spending limits for candidates aspNDIng for public offices

The 2010 Act also made a provision in Section 93(1) that “no political party shall accept or keep in its possession any anonymous monetary or other contributions, gifts, properties, etc. from any source whatsoever”. Section 9(3)(2) provides that “every political party shall keep an account and asset book into which shall be recorded all money and other forms of contribution received by the party; and the names and address of any person or entity that contributes any money or assets which exceeds one million naira” (Federal Republic of Nigeria, Citation2010, p. 28). This provision has been flouted by donors and political parties as shown in , and no action was taken by the regulatory agency (INEC) against defaulters.

Table 2. List of donors for President Goodluck Jonathan’s 2015 presidential campaign: N22.442 billion was realised

Regulating political parties’ activities on election campaigns and maintaining strict adherence to rule of law accelerate democratic dynamisms, consolidate internal and external legitimacy, and curb vote-buying and other electoral menaces. Disorderliness and recklessness in party fundraising undermines public trust in the system and affects acceptance of the government by the people. Political financiers and corporate donors in campaign fundraising are business entrepreneurs, whose objectives are to swing the outcome of the parties’ primary elections and redirect political trends to suit their investments in politics. It debilitates sustainability of the developing democracy in Africa, particularly in Nigeria. Vote-buying, as an offshoot of money politics, has been harmful to any country practising it in Africa. As noted by Egwu (Citation2014, p. 193), “a greater percentage of those that emerged from party primaries are products of impositions … ”. The NDI and NDI observed that the 2018 party primaries for 2019 elections were plagued by vote-buying and rigging. Also the party leadership, in some cases, submitted candidate lists to INEC with nominees who had not won their party primaries. The ensued intra- and interparty disputes emerging from party primaries resulted in 800 court cases (Nigeria International Election Observation Mission Final Report, 2019). According to the Report, INEC acknowledged that 600 petitions were before Election Petition Tribunal but 560 of the petitions received court attention. State constituencies election petition had 309 (55.1%), House of Representatives 155 (27.6%), Senate 69 (12.3%), and Governorship 27 (4.8%). The Report harps on Nigeria’s electoral process which has been fraught with rancour and protestations, frequently resulting in a plethora of election petition cases. For instance, the 2003 elections brought about 560 petitions. In 2007, 1,290 petitions were instituted; in 2011, 732 petition cases; and in 2015, 611 petitions were filed in various Election Petition Tribunals (NDI & NDI, Citation2019).

The presidential election in 2015 witness unregulated campaign donations as President Goodluck Jonathan’ donors surpassed the guiding rules’ threshold and received billions of naira from faceless friends, individuals, ambiguous groups, and corporate bodies, with somewhat “fictitious” names, so also were Mohammadu Buhari’s donors (as shown above) against the constitutional provision in Section 225(2), which provides: “Every political party shall submit to the Independent National Electoral Commission a detailed annual statement and analysis of its sources of funds and other assets together with a similar statement of its expenditure in such form as the Commission may require” (Federal Republic of Nigeria, Citation1999, p. 116). Section 93(2) of the 2010 Electoral Act shielded donors who donated lawlessly and no record of amount, sources, nor donors’ names and addresses were kept for accountability. Unfortunately, INEC did not moderate the exercise or sanction defaulters (). The expenses incurred by the two dominant parties in various campaign strategies were incredibly high and negate the provisions of the 2010 Act as illustrated below.

Table 3. Buhari’s fundraising for 2015 presidential campaign

The expenses incurred by Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP) and All Progressives Congress (APC) campaigns were grossly bloated above the threshold. The figure under PDP on campaigns expenses N8,749,685,305 in failed to capture the alleged $2.1 billion the former National Security Adviser, Sambo Dasuki and Diezani Alison-Madueke, the former Minister of Petroleum Resources laundered on vote-buying, gratifications to organisations, individuals, security personnel, INEC officials, and financial institutions to compromise the presidential election in 2015 general elections. The somewhat senseless disbursement of public funds to serve self at the detriment of the people may be adduced as a plausible determinant factor on why starved voters sell their voting rights for peanuts and sacrifice their future and the future of the unborn generations as detailed in Appendix A1.

Table 4. Comparative analysis of campaigns expenses for 2015 presidential election between PDP and APC

The cash-for-vote syndrome has raised pertinent question on political legitimacy in Nigeria as politicians are deeply enmeshed in uncontainable corrupt practices at all stages of electoral process to win election. In some African countries such as Uganda, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and Malawi, vote-buying is being executed prominently during the periods of campaign. In Nigeria, vote-buying is transacted at multiple stages of the electoral timeline and has been taking place remarkably during voters’ registration, candidates’ nomination period, intraparty primaries, state parties’ conventions, and parties’ national conventions; national assembly elections of key functionaries of the two chambers; and vote-buying is predominantly displayed openly at polling units and collation centres during general elections at the local, state, and national stages.

Vote-buying was glaringly evident during the intra-political parties’ candidates’ nomination process in PDP and APC conventions, specifically during the 3-day presidential primary of the APC in Lagos before 2015 general elections (The genesis of Nigeria’s present predicament). The attendees at the convention were 7,214 delegates, and each participant allegedly received US$5,000 from the two main contestants. The delegates were scheduled to get $2,000 each from the Atiku Abubakar group, and another $3,000 each from the Muhammadu Buhari group. The accredited delegates that participated in the APC primary election were 7,214. Therefore, Atiku’s group might have spent over $14,428,000, and $21,642,000 from Buhari’s group, respectively, purely on vote-buying only, excluding hotel accommodation, feeding, and transportation bills at the primary stage. It was a game of the highest bidder emerging the winner. The People’s Democratic Party, on the other hand, was alleged to have expended state resources in its bid to sponsor President Goodluck Jonathan’s re-election as sole candidate for its presidential ticket as shown in Appendix A1; and the unsolicited campaign visits to northern and western monarchs with alleged undisclosed amount of money at each palace was vote-buying (Owete, Citation2014). At this point, the study focuses on the next section that dealt on 2019 general election ().

Table 5. Buhari’s fundraising for 2019 presidential campaign

3.3. Bad governance, vote-buying in 2019 general elections, and money politics in Nigeria

Vote-buying in 2019 general elections went viral as APC-led government rolled out its intimidating public resources and massive arsenal of coercion to harass and subdue oppositions and their supporters. The National Leader of APC, Bola Tinubu, drove two bullion-vans into his residence on 22 February 2019 during the presidential election from where money was being recklessly dished out in large quantum to party agents for vote-trading. The picture of the bullion-vans () and crowd of prospective vote-sellers went viral in the social media but neither the security agents, Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Independent Corrupt Practices, and other related offences Commission (ICPC) nor the INEC (the regulatory agency) investigated the matter. The INEC chairman and members of the Management Board from the six geopolitical zones, the EFCC chairman, ICPC chairman, Inspector-General of Police, the Service Chiefs, and heads of paramilitary agents are appointees of the president as provided in the 1999 Constitution. These organisations are mere appendages of the presidency, and they brazenly serve the interest of the party in power, not the society. The abuse of utilisation of the security agents, including the military, paramilitary personnel, the police, and their unwelcomed activities which disrupted polling units, collation centres, and the forceful confiscation of the election materials, collated results and unlawful arrest and detention of INEC officials by the military to pervert the elections results in favour of their principles, overwhelmed voters to avoid polling stations. INEC confirmed that collation centres were fiercely invaded by military personnel and armed gangs with the trail of intimidation and unlawful arrest of INEC officials in effort to subvert the will of the electorates. The European Union Election Observation Mission in Nigeria, 2019, the NDI, the NDI, Centre for Democracy and Development, and Integrity Friends for Truth and Peace Initiative jointly condemned the involvement of the military personnel in 2019 general elections in Nigeria (Bassey, Citation2019; WANEP-West Africa Network for Peace Building, Citation2019).

Figure 3. Two bullion-vans in Bola Tinubu’s premises during election periods.Source: https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.vanguardngr.co m/2019/02/money-in-bullion-vans-at-bourdillon-what-is-your-headache-tinubu/amp/.

3.3.1. APC fundraising for 2019 general elections

The APC’s fundraising exercise for 2019 general elections was largely surreptitiously executed. For instance, the party Fundraising Committee mandated the 24 APC governors to raise N6 billion (N250 million per governor) for campaign, but was denied by the party based on public outcry that some of the governors could hardly pay workers salary, and the party concealed its transactions on the project. However, a scanty record was available to showcase some of the campaign funds and materials some groups and individuals donated for Buhari’s presidential campaign as shown below ( & ).

Figure 4. Forty vehicles donated by Malam Nuhu Ribadu Supporter Group for Buhari’s 2019 campaign.Source: https://www.channelstv.com/2019/01/01/controverty-arise-as-ribadu-donates-cars-for-buhari-re-election. campaign.

Figure 5. One hudred vehicles donated by Mohammed Musa, APC stalwart, for Buhari’s 2019 campaign.Source: Odogwu, C. (2019). https://naijauto.com/market-news/buharis-presidential- campaign-receives-more-than-100-cars-and-house-2178.

The exercise registered the lowest voter turnout (34.8%) and the highest vote-buying incidence in the history of election in Nigeria. The unfavourable economic policies of the government, minimal inflow of foreign investments, and extinction of domestic manufacturing industries impoverish poor citizens the more and engender vote-buying. Voters were willing to sell their votes as the only appealing option to empower themselves for a day or two to meet their immediate social needs. Vote-buying prevailed predominantly before and during the election periods due to prevailing hardship. In most cases, the effectiveness of vote-buying with vulnerable voters is literally interpreted as manifestation of the fact that the small material goods acquired translates to a greater marginal utility to poor voters (Baidoo et al., Citation2018). The quantum of money being distributed openly in the market places, in churches, mosques, and individual homes by APC was an irresistibly wooing bait amongst the poor. Its unbridled prevalence depicts the degree of the political elites’ rife with lawlessness and corruption. Bolanle (Citation2019) expressed surprise that vote-buying surfaced in 2019 general elections. Money was prevalent as a major factor in Nigeria politics, focusing on the poor. Voters’ wish to sell their voting rights is associated to the level of poverty in Nigeria, and the poor perceived their voters’ cards as a source of generating resources. Vote-buying limits voters to exercise their voting rights, coupled with fear of intimidation to comply with the terms of contract.

Ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo asserted that Osinbajo displayed executive recklessness and abuse of public office as vice president. The former president expressed disappointment in the way and manner Professor Osinbajo carried out his campaign activities which Obasanjo claimed had exhibited human frailty and proved the old saying that “corruption of the best is the worst form of corruption”. The explanation Osinbajo adduced that the trader-moni scheme was APC government-led initiative is being understood to be lacking substance and uneven, possibly a wasteful programme. Trader-moni, as federal government programme, was aimed to provide 2 million petty traders across Nigeria with non-collateral loans. Within 5 months, the vice president randomly distributed N10,000 to petty traders across the country in a bid to “empower” them to be “more resourceful and self-sustaining”. The critics highlighted that traders in rural and sub-urban areas of Nigeria are more than those in urban areas; and they are poorer than petty traders in Lagos, Abuja, and other cities. This category of poor citizens needs more attention and greater assistance from government (Iroanusi, Citation2019).

The puzzle in the minds of patriots is the nexus between taking the number of Permanent Voters Card (PVC) of the recipients of the N10,000 bogeyed to “petty traders” and the 2019 general elections. There is evidence of inauspicious elements in the entire hoax. With the INEC officials’ conspiracy and available card readers’ dysfunctionality, by quoting the PVC number, anyone in its possession might be allowed to vote as the revised Electoral Bill 2018 was not assented by the president. If that took place all over Nigeria, it might have resulted in massive rigging as the timing of the trader-moni project was a suspect (Iroanusi, Citation2019). Some of the vote-buying incidents are illustrated in Appendix A2.

The practice of vote-buying in Nigeria has been sustained to flourish due to weak institutional framework on ground, lack of financial and administrative autonomy of the electoral umpire, partisanship of INEC officials, and corporate corruption indices of the law enforcement agencies in aiding and abetting commercialisation of electoral process. The INEC, with its apparent subservient role, is powerless to investigate the activities of its employer or investigate the opposition parties. This weakness accounts for the undue political interference in INEC and ICPC statutory functions. The regulatory agencies are overtly partisan in all elections in order to secure their jobs and retain their “relevance” in the system. The docility of these impotent organisations serves the interests of the political elites in rigging elections and by extension the acceptance of the vote-trading culture as a norm in Nigeria. The political environment is grossly polluted and the negative reciprocal tendencies of voters not to vote for corrupt politicians without receiving instant reward seem to have watered vote-trading, as a survival strategy, to glow as a commercial venture. Vote-buying has adverse implications on the quality of lives of the people, socio-economic policies, and sustainability of political development as the next section takes on implications of vote-buying.

3.4. Implications of vote-buying on democratic development in Nigeria

One of the major implications of vote-buying is that it is capable of sparking off corruption amongst politicians after voting them into power. The danger is that politicians would firstly recoup all the money invested during nomination of candidates, party-primary election and campaigns. This ugly development will definitely result in looting of state treasury. Vote-buying attached to materials or cash incentives, apart from increasing financial burden on politicians, has its consequences on good governance in Nigeria. It serves as a springboard to catapult unsalable, incompetent elements and unsuitable political parties to public elective offices. Vote-buying enslaves vulnerable voters who are paid to support candidates of a particular party; it restricts their freedom of choice and blurred their rationale decision-making skill. The viral nature of vote-buying in 2019 general elections stimulates genuine concern about the leadership quality, capability of service delivery, and effectiveness of emerging democratic institutions; and ensuing results of the despicable elections conducted in Nigeria (Baidoo et al., Citation2018; Sarkariyau et al., Citation2015).

The populace is wittingly being starved to death through incompetence and leadership gaps; therefore, a vigorous government-driven poverty reduction initiative is an appealing strategy as a palatable option to curb vote-buying and fight poverty in the country. 2019 poverty rate index revealed that 91,885,874 people in Nigeria live in extreme poverty occasioned by unemployment and insecurity. Unemployment rate in 2019 was 23.1% and forecast to rise to 33.5% in the year 2020. Nigeria was declared Poverty Capital of the World (World Poverty Clock 2018). Illiteracy is the worst pestilent disease afflicting less educated voters. In 2018, illiteracy rate was 30% of the population, which comprised 65 million Nigerians; and a survey on Nigeria, conducted by the United Nations Children’s Fund, indicates that the population of the out-of-school children in Nigeria has risen from 10.5 million to 13.2 million in 2019, the highest in the world (premiumtimesng.com; google.com).

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) are genuinely canvassing for robust legislation and commensurate sanctions against culpable elements, stressing monitoring elections through playing the role of preventing vote-buying at the polling stations. The CSOs have not resisted nor overtly protest against the practice other than the subtle approach as vanguard of good governance. They advocate for vote education and wider civil education programmes as veritable tools to widening voters’ horizons on how vote-trading impacts negatively on their future well-being. The phenomenon of vote-buying, as a pestilence, is a symptom of grievous challenges bordering on the integrity, credibility, and legitimacy of electoral processes. It is a complex crime that involves political elites, the presidency, the legislature, the judiciary, political parties, and all other security agents and anti-graft supervisory agencies as accomplices. Therefore, in every regime, the issue is not about vote-buying, rather, it is purely located in conspicuous absence of respect for rule of law. The subsisting law is adequate to checkmate defaulters and address the menace, but its enforcement, unfortunately, is completely zero on the scoreboard. The hegemonic leadership, suppression of the populace, and extreme application of coercion to sustain the grip to political power do not create political ventilation for freedom of expression nor would CSOs’ resistance of the social plague make a change without drastic actions. Despotism and lack of political will would smash all resistance on the path of this scourge.

Governments at all levels should have the political will to fight the vote-buying menace; bodies like the National Orientation Agency, INEC, Civil Society Organisations, the media, social organisations (e.g., churches, mosques, and community-based associations), and all internal and external stakeholders in Nigeria project should declare total war against illiteracy and this pestiferous plague dubbed “vote-buying” that blindfold the citizenry, to rekindle the moral values of the people, so as to enhance sustainable development in the country. Vote-buying rears underdevelopment, stunts public service delivery to the people, institutes unpopular political party with transactional leadership into power, raises despotic ruler, emboldens ineptitude, and bad governance. The sensitisation campaign would focus on educating the electorates about the danger in accepting gratifications and selling their voting rights for peanuts, mortgaging their future and the future of unborn generations; strengthening with vigour the genuine process of sustaining precepts of democracy, and stressing the harmful effects of plutocratic politics to transparency and accountability, and protection of freedom of choice in elections (Baidoo et al., Citation2018; Sarkariyau et al., Citation2015).

4. Conclusion

Vote-buying is one of the factors militating against political development and sustainability of democracy in Nigeria. The country is practising a “patronage democracy”, a carrot and stick relationship between vote-buyers and vote-sellers in consolidation of commercialisation of the polity. The quantum of money in circulation during election barraged political development. Vote-buying is prevalent in Nigeria because an average voter in the country is poor and cannot resist the charming effects of uncontainable electoral bribes in cash or kind, and tantalisation of voters with job opportunities purported to exist; and the political elites’ disposition to capitalise on the weak-voters’ unity in vulnerability to exploit the situation to render them politically feeble to control their rights to vote for candidates of their individual choice.

Poverty, unemployment, and illiteracy have been identified by scholars as the major causes of vote-buying. The study argues that electoral fraud is fundamentally a derivative of vote-buying. Vote-buying is the origin of bad governance, facilitator of imposition of wrong and inept group of unsalable persons to find spaces in governance. Insecurity of lives and properties, disunity amongst ethnic groups, secessionists’ agitations from various ethnic associations, the massive blood-letting in all parts of the country, and enormous deficit of infrastructures are the products of vote-buying. The plague generates inept leadership and ineptitude yields poverty, unemployment, and illiteracy. Therefore, emphasis should be located on fierce wrestling against vote-buying and the capacity to institute legal suits against the culprits. CSOs, spNDIted citizens, and other stakeholders should operate beyond rhetorics and take proactive actions against political parties, politicians, or their agents and any delinquent anti-graft agency identified to have been involved in vote-buying or aiding and abetting vote-trading to face the wrath of the law. The “Independent” National Electoral Commission would exhibit proficiency only when it is constitutionally independent; when unbiased appointment of the chairman would be competitive through electoral process.

The utilisation of functional card readers in accrediting eligible voters must be sustained to curb electoral irregularities. The precept of ballot secrecy needs functional election legislation to ensure secret voting is not only a right on voters’ part but an absolute obligation that must be observed during election periods. Secret ballot is important to sustain the electoral integrity, and one of the primary devices being applied to restrain vote-buying.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kingsley Chigozie Udegbunam

Ejikeme Jombo Nwagwu was a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Political Science, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The author completed his master’s and doctoral degrees in the field of public administration at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He published widely in international and local journals. He had an interest in studies on good governance and human capital development, public policy and problem solving programmes, grassroots democracy and rural development, and peace and conflict studies. He died in September 2021 while this paper was still under peer review.

References

- Abba, S., & Babalola, D. (2017). Contending issues in political parties in Nigeria: the candidate selection process. Journal of Pan African Studies, 11(1), 118–28. http://www.jpanafrican.org/docs/vol11no1/11.1-11-Abba-Babalola.pdf.

- Adekoya, R. (2019). The 1951 elections: how awolowo forced Azikiwe out of western Nigeria. Business Day. Retrieved from 6. March 6, 2020. https://businessday.ng/columnist/article/the-951-elections-how-awolowo-forced-azikiwe-out-of-western-nigeria/

- Adigun, O. W. (2019). Vote buying: examining the manifestations, motivations, and effects of an dimension of election rigging (2015-2019). Canadian Social Science, 15(11), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.3968/11392

- Ake, C. (1996). Democracy and development in Africa. Spectrum Books Ltd.

- Ali, S. (2018). Votes on sales in several constituencies. Down.Com, Retrieved from July 24, 2021. https://www.down.com/news/1420313

- Aljazeera. (2019). India cancels polling in southern constituency over vote buying. Retrieved from August 18, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/04/india-cancels-poll-southern-area-vote-buying-190417121304093.html

- Alli, Y. (2016). EFCC traces Diezani’s $115m election bribery cash to stolen oil. Retrieved from May 6, 2020. http://saharareporters.com/2016/05/03/efcc-traces-diezani’s-115m-election-bribery-cash-stolen-oil

- Amao, O. B. (2020). Nigeria’s 3029 general election: what does it mean for the rest of the world? The Round Table, 109(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2020.1788767

- Baidoo, F. L., Dankwa, S., & Eshun, I. (2018). Culture and vote buying and its implications:range of incentives and conditions politicians offer to electorates. International Journal of Developing and Emerging Economics, 6(2), 1–20.

- Bari, S. (2018). Vote buying: A curse of inequality. The Express Tribune, Retrieved from July 20, 2021. https://tribune.com.plc/story/1700883/6-vote-buying-curse-inequality

- Bassey, J. (2019). Militarisation of elections diminishes Nigeria’s democracy. Accessed 22 February 2020. https://businessday.ng/ng-election/article/militarisation-of-elections-diminishes-nigerias-democracy-ulc

- Bolanle, A. O. (2019). Vote buying and selling as violation of human rights: Nigerian experience. Retrieved from April 24, 2020. https://catholicethics.com/forum/vote-buying-and-selling-as-violation-of-human-rights-the-nigerian-experience/

- Bryan, S., & Baer, D. (2005). Money in politics: A study of party financing practices in 22 Countries. National Democratic Institute for International Affairs.

- Burnham, P., Gilland, K., Grant, W., & Layton-Henry, Z. (2004). Research methods in politics. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Canare, T. A., Mendoza, R. U., & Lapez, M. A. (2018). An empNDIcal analysis of vote buying among the poor: evidence from elections in the Philippines. South East Asia Review, 26(1), 58–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967828X17753420

- Cherry, K. (2018). What is reciprocal determinism? Verywell Mind. Retrieved from August 16, 2019. https:www.verywellmind.com/what-is-reciprocal-determinism-2795907

- Desposato, S. W. (2007). How does vote-buying shape the legislative arena? In F. C. Schaffer (Ed.), Elections for sale: The causes and consequences of vote buying (pp. 144–179). Lynne Rienner.

- Egwu, S. (2014). Internal Democracy in Nigerian Political Parties. In O. Obafemi (Ed.), Political Parties and Democracy in Nigeria. University Press.

- Etzioni-Halevy, E. (1989). Exchange material benefits for political support: A comparative analysis. In D. Heidenheimer (Ed.), Political corruption: A handbook (pp. 287–304). Traction Publisher.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. (1999). Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. Government Press.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2010). An Act to Repeal the Electoral Act 2006 and Re-enact the Independent National Electoral Commission Regulate the Conduct of Federal, State and Area Council Elections and for Related Matters, 2010. Government Press.

- Felongco, G. (2019). Philippines elections: allegation of fraud, widespread vote buying emerged. Gulf News, Retrieved from August 14, 2021. https://gulfnews.com/world/asia/philippines/philippines-elections-allegations-of-fraud-widespread-vote-buying-emerge-1.63897798

- Gonzalez-Ocantos, E. de Jonge, C.K., Meléndez, C., Osorio, J., Nickerson, D.W. (2010). Vote buying and social desirability bias: experimental evidence from Nicaragua. Retrieved from August 14, 2021. https://sites.temple.edu/nickerson/files/2017/07/Nicaragua.AJPS2011.pdf

- Heath, O., & Tillin, L. (2017). Institutional performance and vote buying in India. St. Comp Int. Dev, Retrieved from March 26, 2020. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12116-017-9254-x. . https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-017-9254x

- Hicken, A., Leider, S., Ravanilla, N., & Yang, D. (2015). Measuring vote-selling: Field evidence from the Philippines. The American Economic Review, 105(5), 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151033

- Iroanusi, Q. E. (2019). Obasanjo attacks osinbajo says trader-moni an idiotic programme. Retrieved from May 13, 2020. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/306825-obasanjo-attacks-osinbajo-says-tradermoni-an-idiotic-programme-premium-times-nigeria.html

- NDI/NDI (2019). Nigeria International Election Observation Mission Final Report. Accessed from https://www.ndi.org/publications/NDIndi-nigeria-international-election-observation-mission-final-report.

- Jensen, P. S., & Justesen, M. K. (2014). Poverty and vote buying: survey-based evidence from Africa. Electoral Studies, 33(1), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.07.020

- Johnson, J. B., & Joslyn, R. A. (1995). Political science research methods. CQ Press.

- Kayode-Adedeji, D. (2015). We rejected Jonathan’s $3million – Islamic groups. Premium Times. Retrieved from April 25, 2020. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/195797-dasukigate-we-rejected-jonathans-3-million-islamic-groups.htm

- Khemani, S. (2015). Buying votes versus supplying public services: Political incentives to under-invest in pro-poor policies. Journal of Development Economics, 117(c), 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.07.002

- Kramon, E. (2009). Vote buying and political behavior: estimating and explaining vote-buying’s effect on turnout in Kenya. Afrobarometer Working Papers No. 114.

- Kramon, E. (2016). Where is vote buying effective? evidence from a list experiment in Kenya. Electoral Studies, 44, 397–408. Retrieved from August 15, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.09.006

- Mogalakwe, M. (2006). The use of documentary research methods in social research. African Sociological Review, 10(1), 221–230.

- Mustopha, L. K., & Omar, B. (2020). Do social media matter? examining social media use and youths’ political participation during the 2019 Nigeria general elections. The Round Table, 109(4), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2020.1788766

- N23billion diezani bribe: INEC staff pleads guilty to receiving N30million. Premium Times, April 5, 2017. Retrieved from 28 April 2020. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/228000-n23-billion-diezani-bribe-inec-staff-pleads-guilty-receiving-n30-million.html

- Nassaji, H. (2015). Qualitative and descriptive research: data type versus data analysis. Language Teaching Research, 19(2), 129–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815572747

- NnochNDI, I. (2016). Former national security adviser, Col. Sambo Dasuki (rtd.) $2.1billion arms deal: FG re-arraigns Dasuki, 3 others on amended 32-count charge. Vanguard Newspaper. Retrieved from May 8, 2020. https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.vanguardngr.com/2018/05/2-1bn-arms-deal-fg-re-arraigns-dasuki-3-others-amended-32-count-charge/amp/

- Nurdin, A. (2014). Vote buying and voting behavior in Indonesia local election: A case in Pandeglang District. Global Journal of Political Science and Administration, 2(3), 33–42. https://www.eajournals.org/wpcontent/uploads/Vote-Buying-And-Voting-Behavior-In-Indonesian-Local-Election-A-Case-In-Pandeglang-District.pdf

- Nwagwu, E. J. (2016). Political party financing and consolidation of democracy in Nigeria, 1999-2015. International Journal of Political Science, 2(4), 74–85.

- Odogwu, C. (2019). Buhari’s Presidential Campaign receives more than 100 cars, Naijauto.Com https://naijauto.com/marketnews/buharispresidentialcampaign-receives-more-than-100-cars-and-house-2178

- Ojo, J. (2020). Inconclusive elections and the integrity of the 2019 Nigeria’s Polls. The Round Table, 109(4), 458–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2020.1790777

- Onuoha, F., & Ojo, J. (2018). Practice and perils of vote buying in Nigeria’s recent elections. Retrieved from April 22, 2020. https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/practice-and-Perils-of-vote-buying-in-nigeria-recent-elections

- Olaniyan, A. (2020). Election sophistication and the changing contours of vote buying in Nigeria’s 2019 general elections. The Round Table, 109(4), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2020.1788762

- Olorunmola, A. (2016). Cost of politics in Nigeria. Westminster Foundation for Democracy, Retrieved on May 18, 2020. https://www.wfd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Cost-of-Politics-Nigeria.pdf

- Onapajo, H., & Babalola, D. (2020). Nigeria’s 2019 general elections – A shattered hope? The Round Table, 109(4), 363–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358533.2020.1788765

- Onapajo, H., Francis, S., & Okeke-Uzodike, U. (2015). Oil corrupts elections: The political economy of vote-buying in Nigeria. African Studies Quarterly, 15(2), 1–21. https://sites.clas.ufl.edu/africanquarterly/files/Volume-15-Issue-2-Onapajo-Francis-and-Okeke-Uzodike.pdf

- Onuoha, F.C. & Okafor, J.C. (2020). Democracy or Moneyocracy? Perspective on vote buying and electoral integrity in Nigeria’s recent elections, Africa Insight 49(4), 1–14.

- Onwudiwe, E., & Berwind-Dart, C. (2010). Breaking the Cycle of Electoral Violence in Nigeria. United States Institute of Peace, Special Report 263.

- Onyekwere, J. (2017). EFCC names beneficiaries of Alison-Madueke’s Alleged Bribe. The Guardian Newspaper. Retrieved from May 11, 2020. https://m.guardian.ng/news/efcc-names-beneficiaries-of-alison-maduekes-alleged-bribe/

- Ovwasa, O. L. (2013). Money politics and vote buying in Nigeria: the bane of good governance. Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3.4 Quarter III), 1–19.

- Owen, D. A. (2013). Conceptualising vote-buying as a process: an empNDIcal study in Thai Provence. Asian Politics and Policy, 5(2), 249–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12028

- Owete, F. (2014). Buhari wins APC presidential ticket. Premium Times. Retrieved from May 18, 2020. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/173134-buhari-wins-apc-presidential-ticket.html

- Sanni, K. (2019). 2019: vote-buying most prevalent in South-South, among educated Nigerians. Premium Times. Retrieved from July 23, 2021. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/369829-2019-vote-buying-most-prevalent-in-south-south-among-educated-nigerians.html