Abstract

Urban household food insecurity is highly prevalent in Zimbabwe due to the persisting poor macro-economic environment, droughts, HIV and AIDS and climate change. This paper examines the effectiveness of cash transfers in alleviating urban household food insecurity in the city of Bulawayo. The assessment focuses on understanding the extent to which cash transfers improve poor households’ access to food. The study was conducted in Makokoba and Njube townships. A combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods were used in gathering and analysing data. Purposive sampling techniques were used to select study participants. Semi-structured in-depth interviews (50), questionnaires (280), and key-informant interviews (11) were used to collect primary data. The study is anchored on Sen’s Entitlement Approach in examining the role of cash transfers in strengthening trade-based entitlements of ultra-poor households. We find that cash transfers have nominally alleviated urban household food insecurity in these townships. Households receiving cash transfers have not meaningfully improved access to food on a regular basis. They ate small quantities of food, skipped meals and had poor dietary diversity regardless of receiving cash transfers. Factors such as low transfer value, irregular distributions, weak targeting mechanisms, disbursement mechanism and poor communication have deterred the effectiveness of cash transfers in the two townships. We recommend a revamp in design and implementation processes of cash transfer programmes. Transfers meant for improving access to food should be implemented in conjunction with livelihood projects to enable poor urbanites to meet non-food basic needs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Urban household food insecurity is increasing in many developing countries despite global commitments of ending poverty and hunger. Urban household food insecurity is a result of an array of factors such as; rising food prices, weak institutions, high unemployment, poor governance, population growth and limited livelihood/employment opportunities. Cash transfers have been implemented to alleviate urban household food insecurity. Cash transfers are social protection programmes that have been implemented in many developing countries to alleviate food insecurity and poverty at large. This study examines the role of cash transfers in alleviating urban household food insecurity in Bulawayo townships in Zimbabwe. Findings form this study suggest that cash transfers have not significantly improved food access for poor urbanites. Households receiving cash transfers reported unstable food access due to low transfer value, irregular distributions, weak targeting mechanisms, disbursement mechanism and poor communication. Households continued eating small quantities, skipping meals and poor dietary diversity.

1. Introduction

Urban household food insecurity has increasingly become deterrent to sustainable development in many countries of the Global South despite global commitments of ending poverty and hunger by 2030. Food insecurity is defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) & World Food Programme (Citation2015, p. 53) as “a situation that exists when people lack secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active and healthy life”. Rising food prices, weak institutions, high unemployment, poor governance, population growth and limited opportunities to produce food are some of the factors that have aggravated urban poverty in many developing countries (Battersby, Citation2013; Legwegoh et al., Citation2020; Ravillion, Citation2016). Urban poverty has deepened as economies in many African countries have failed to support the increasing population in improving incomes and standards of living (Frayne et al., Citation2014). Urban food security hinges on household’s purchasing power. Resultantly, urban poor households are extremely vulnerable to food insecurity due to persistently low incomes (Ndlovu et al., Citation2019; Ruel et al., Citation2017). Poor urban households are vulnerable to income and food price shocks due to dependence on food purchases and income from the informal sector (Ruel et al., Citation2017).

Governments and Non-Governmental Organisations have implemented cash transfer programmes in urban settings targeting ultra-poor, labour constrained families, households with orphans and vulnerable children, and other specific vulnerabilities (Food and Agriculture Organisation, Citation2014). Cash transfers are social protection programmes that have been implemented in many developing countries to alleviate food insecurity and poverty at large. Cash transfers are payments that are provided by formal institutions to selected recipients to enable them to meet their minimum consumption needs (Pega et al., Citation2014). Cash transfer programmes provide a predictable and reliable source of income to food insecure households (Mokomane, Citation2013). These transfers are diverse in their objectives and designs. Cash transfer programmes vary as some have been available to all, available to a selected group, conditional and unconditional (Johnston, Citation2015).

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) provide cash incentives for households to engage in specified behaviours (Sandberg & Tally, Citation2015; Scarlato et al., Citation2015; Yeboah et al., Citation2015) such as sending children to school, attending health check-ups, attending trainings and performing some community/public works. Conditional cash transfers are widespread in many Latin American, South and East Asian countries with long-term objectives of improving human capital development. Conditional cash transfers are intended to alleviate poverty through investing in children with the aim of building human capital. Investing in human capital is viewed as an important tool for breaking out the vicious cycle of household poverty (Rabinovich & Diepeveen, Citation2015; Saad-Filho, Citation2015). Unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) are grants paid to beneficiaries without having to do anything specific to receive the benefit (Garcia & Moore, Citation2012). Unconditional cash transfers are common in Sub-Saharan Africa. In recent years Universal Basic Income (UBI) has been introduced as a policy option in addressing poverty. A Universal Basic Income provides unconditional and no targeting cash transfer (Gentilini et al., Citation2020). Large scale UBIs have mainly been implemented in countries such as Mongolia, Iran, China, India and United States. Some countries (for example, Kenya, Namibia, Uganda, India) have piloted UBI on small scale. The implementation of the UBI is still at the stage of infancy, and a handful of countries have either launched pilot projects recently or are considering one (United Nations Development Programme China Office, Citation2017). Many developing countries are resource constrained which hinders implementation of UBI projects.

Targeting processes for cash transfers are mainly informed by national surveys and community-based processes. In most cases amounts received depend on the number of household members. The role of these cash transfers in addressing household food insecurity is largely determined by programme designs, implementation processes and context (Holmes & Bhuvanendra, Citation2013). Cash transfers have been implemented in supporting the four pillars of food security (availability, access, utilisation and stability). Available evidence from many developing countries shows that improvements in household income, boosts their food purchasing power. Cash transfers have also been implemented to improve access to food by poor urbanites in Bulawayo townships, Zimbabwe. This study examines the contributions of cash transfers in addressing urban household food insecurity in Makokoba and Njube townships, Bulawayo.

2. Theoretical framework

The study is anchored on Sen’s (Citation1981) Entitlement Approach which explains occurrences of food insecurity in circumstances where food is available but households lack entitlements over it. An entitlement refers to a person’s set of alternative commodity bundles that can be acquired through the use of various legal channels of acquirement open to that person (Sen, Citation1981). The entitlement approach provides four categories of legal sources of food, namely, production, labour, trade and transfers entitlements. Sen’s (Citation1981) main argument is that food insecurity is not caused by food supply failure but lack of access to food. Originally the entitlement approach helped explaining the manifestation of famines in settings where aggregate food supply was adequate to feed entire population in specific countries, the approach has also been used in explaining the occurrence of poverty, food insecurity and economic problems experienced households in various settings (Dodson et al., Citation2012). Sen explains entitlements through the endowment set, entitlement mapping, and the entitlement set concepts. An endowment set is comprised of legal resources (tangible and intangible) that a person owns and are used to obtain basic commodities. The study utilises Sen’s entitlement approach in assessing the role of cash and in-kind transfers in improving endowment sets of food insecure households so as to allow them to access food. Poor urban households struggle to secure sufficient income as they rely on precarious formal employment for their livelihoods (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2012). Poor urban households experience food insecurity due to factors that negatively influence their endowment sets thereby limiting their entitlement mapping options.

In line with the entitlement approach, urban poor households in Bulawayo are extremely vulnerable to food insecurity due to persistently low incomes which affect their exchange or trade-based entitlement. In many urban areas, food is available in the markets but poor households fail to access it due to limitations in their entitlements (Dodson et al., Citation2012; Simiyu & Foeken, Citation2014). Poor urban households with weak purchasing power and limited assets are vulnerable to food insecurity as they lack entitlements over food that is available in the markets (Alemu, Citation2007). Cash transfers are part of the social security programmes which form transfer entitlements. Within entitlement approach reasoning, this study therefore explores the role of transfer entitlement in addressing food insecurity in Bulawayo. The study therefore assesses the role of cash transfers in improving the endowment sets (purchasing power) of poor households to strengthen their trade-based entitlement.

3. Cash transfers in the Global South

Literature demonstrates that the introduction of cash transfers in many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, South and East Asia, and Latin America has resulted in improvements in access to food by poor households. Cash transfers have been implemented to improve purchasing power of food insecure households. Poor households fail to access adequate food due to low income. Household poverty and food insecurity are highly interwoven issues that reinforce each other (Tolossa, Citation2010). In consequence, poverty is largely seen as an impetus for household food insecurity in many countries. Oduro (Citation2015) echoes that;

Over the years cash transfers have gained increased recognition among international development partners as a core pro-poor development tool for reducing short term poverty, breaking the intergenerational transmission of poverty …

Thus Oduro (Citation2015) explains that cash transfers have been implemented to reduce poverty which has a negative bearing on household food security. Further to this, Hall (Citation2012) argues that many Latin American countries introduced cash transfers to generate a sustained increase in household income/purchasing power. Increases in household income have resulted in improvements in access to food. In their 2013 “State of Food Insecurity in the World” report the Food and Agriculture Organisation, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) & World Food Programme (Citation2013) point out that global access to food improves significantly in line with income poverty reduction. This is largely because income poverty is recognised to be a root cause of food insecurity in many food insecure households.

Crush & Frayne, Citation2010) also note that widespread food insecurity in many Southern African cities is a poverty related phenomenon. In line with this, the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) (Citation2011, p. 17) points out that;

Cash transfers constitute the most direct possible approach to addressing extreme poverty. By directly providing income or consumption goods and services to the poor, cash transfers can raise living standards, reduce the gap rich and poor.

Available evidence from many developing countries shows that improvements in household income results improved purchasing power amongst poor households. In some settings the implementation of cash transfers has resulted in reductions in household poverty. This has resulted in improvements in households’ purchasing power which has in turn improved economic access to food. Evidence suggests that implementation of cash transfers in many Latin American countries has contributed towards combating poverty. Grugel and Riggirozzi (Citation2012, p. 10) summarise the role of cash transfers in reducing poverty as follows;

In Argentina, levels of poverty have now retreated to their normal level of around 11 percent from a peak of over 45 percent in 2002. In Bolivia the number of those classified as poor dropped from 62 percent of the population to 54 percent between 2008 and 2010. The percentage of Venezuelans living below the poverty line fell from 49.4 percent in 1999 to 27.6 percent in 2008; while in Ecuador, the number of poor people has fallen by 10 percent …

This illustrates that cash transfers have played a central role in reducing income inequality in food insecure communities in Latin America. Such evidence demonstrates that cash transfers play a great role in reducing household poverty which in turn reduces food insecurity.

Studies have also shown that cash transfers directly increase income which can be spent on increasing the quantity and quality of food purchased (Alderman, Citation2014; Holmes & Bhuvanendra, Citation2013). Pega et al. (Citation2015) are of the view that lack of financial resources is a key barrier that prevents poor households from accessing basic goods like food, thus cash transfers provide regular income. With reference to Nicaragua, Maluccio (Citation2010) concluded that households that received cash transfers experienced significant improvements in accessing food. This has been witnessed in many food insecure environments. Increases in purchasing power enable households to access adequate food (Miller et al., Citation2011; Bailey & Hedlund, Citation2012). Evidence from evaluations in many countries in the Global South has shown that cash transfers improve access to food as a result of increasing expenditure on food (Hugo & Gaia, Citation2011). Households receiving additional income are particularly likely to prioritise spending on improving the quantity and or/quality of food consumed (Gentilin, Citation2015).

In addition, cash transfer programme evaluations conducted in Malawi (2008–2009) revealed that on average recipient households spent approximately 75% of the money on purchasing food (Vincent & Cull, Citation2009). A study done in India concluded that cash transfers provided opportunities for poor households to shift to nutritious non-cereal options (Gangopadhyay et al., Citation2015). Another study done in Niger by Tumusiime (Citation2015) concluded that cash transfers have a positive influence on food consumption for poor households thereby alleviating food insecurity. Accordingly, cash transfers improve food expenditures thereby improving food consumption.

Cash transfers have also stabilized access to food which results in increasing the number of meals and quantities of food consumed. For example, results from a study done in Mozambique concluded that the Basic Social Subsidy Programme provided predictable and regular transfers of food cash which resulted in smoothing households’ consumption. Another study conducted in Mexico City by Gentilin (Citation2015) established that Prospera transfers improved food consumption of poor households. Holmes and Bhuvanendra (Citation2013) also established that cash transfers increase the number of meals consumed by beneficiary households based on results from studies done in several cities including Abijan, Port-au-Prince, Manila and Nairobi. Thus, cash transfers are important for improving household food purchasing power which in turn improves food consumption behaviours of poor households. Given the role of cash transfers in enhancing access to food in other countries, the study examines their effectiveness in alleviating urban household food insecurity in Bulawayo townships.

4. Context of the study

Zimbabwe is a land-locked country in Southern Africa. It is a low-income, with a population of about population of 13,061,239 (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2012). Since year 2000, Zimbabwe has undergone deteriorating economic challenges which have resulted in deep economic and social crises (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2013). The economic crises have been characterized by a myriad of challenges such as hyperinflation, low industrial capacity utilization and declines in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Between 2000 to 2006 Zimbabwe’s GDP declined by 36% and the unemployment rate increased to around 80% (Chimhowu, Citation2009; Parsons, Citation2007). Tawodzera (2012) also noted that Zimbabwe has become a world leader in creating poverty and food insecurity. Gandure et al. (Citation2010) also argued that Zimbabwe has moved from being the food basket of Southern Africa to a hub of food insufficiency.

Poor urbanites in Zimbabwe experience high poverty and food insecurity due to political, persisting poor macro-economic environment, droughts, HIV and AIDS and climatic dynamics which have impeded the stability of food availability and access. In recent years, the food insecurity situation in Zimbabwe has been worsened by economic related shocks such cash shortages, high food prices, loss of employment and high fuel costs (Food and Nutrition Coucil, Citation2014). Urban poverty induced by precarious livelihoods in Zimbabwe is a major underlying cause of vulnerability to household food insecurity. By year 2016 the economy was characterized by low investment, high external debt and constrained employment opportunities which affected the purchasing power of poor urbanites (Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, Citation2016). Poor urban households have low purchasing power which inhibited access to adequate food supplies. An urban vulnerability assessment survey conducted in 2016 highlighted that 80.6% of urbanites reported loss of employment and income source as major challenges experienced (Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, Citation2016). Most (76.8%) urban households in Zimbabwe live below the Food Poverty Line (Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, Citation2016). Poor urbanites struggle to put food on the table due to prolonged economic hardships.

Given this backdrop, this study assesses the effectiveness of cash transfers in alleviating urban household food insecurity in poverty wracked townships in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Bulawayo continues to experience high rates of poverty, unemployment, deteriorating infrastructure and overcrowding. Many of the city’s townships (including Makokoba and Njube) are therefore home to many urban poor and food insecure households (Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, Citation2016). Given the centrality of cash transfers in livelihoods and food security of the urban poor in other countries, we therefore found it opportune to assess their effectiveness in alleviating urban household food insecurity in Bulawayo townships. In addition to documenting the obvious merits of cash transfers, we critically examine factors that hinder their effectiveness in addressing urban household food insecurity. The study also questions the implications of cash transfers on household dietary and diversification.

5. Overview of harmonised cash transfer programme in Zimbabwe

The government of Zimbabwe has implemented various social protection programmes since 1980. Social protection is key for the achievement of human development. Social protection needs have increased over the years due to socio-economic shocks (United Nations International Children Emergency Fund, Citation2020). A persistent unstable macro-economic environment has negatively affected social protection programmes in Zimbabwe. The poor performance of the economy has resulted in irregular and under financing of social protection programmes (Ravillion, Citation2016). Zimbabwe spends about 1.2% of GDP or 7.3% of total national budget on social protection programmes and this is insufficient considering ever increasing social protection needs (United Nations International Children Emergency Fund, Citation2020). In this regard the social protection programmes have covered a small proportion of citizens. Many vulnerable individuals and or households are not supported by social protection programmes. The government of Zimbabwe works with various development partners in providing social protection to vulnerable citizens. Social protection in Zimbabwe is guided by the National Social Protection Framework. The main social protection programmes in the country include Basic Education Assistance Module, Health Assistance, Food Deficit Mitigation and the Harmonised Social Cash Transfer.

The government of Zimbabwe through the Ministry of Labour and Social Services introduced the Harmonised Cash Transfer (HSCT) programme in year 2011. The objective of the HSCT programme has been to strengthen the purchasing power of ultra-poor households who are labour-constrained and live below the food poverty line (Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare, Citation2014). The programme was designed to support ultra-poor and labour constrained beneficiary households in increasing consumption to above the food poverty line. The cash transfer programme targeted food-poor households who; i) eat only one or no meal per day, ii) are not able to purchase essential non-food items, iii) live on begging or some piece work, have no valuable assets, and iv) get no regular support from relatives, pensions, and other welfare programmes (Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare, Citation2014). HSCT programme also targets labour-constrained households. These are households; i) without able-bodied members (aged 18–59) fit for work, or ii) have a high ratio of dependents (more than three children, chronically ill, or disabled members per one adult), or iii) have a severely disabled or chronically ill member who requires intensive care (Angeles et al., Citation2018).

Beneficiary households received bi-monthly unconditional cash payments of between US$10 to US$25 per month depending on the size of the household, one member, $10; two members, $15; three members, $20; four members and above, $25 (Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare, Citation2014). Distributions are done through a cash-in-transit method by a private security company. Distributions were organised by the Department of Social Services Office. Like other social protection programmes, the HSCT has been underfinanced, thereby covering a few vulnerable households. Only 55,059 households benefitted from the HSCT programme in 2014, representing approximately one third of vulnerable households (Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare, Citation2016). HSCT has been implemented in all the 10 provinces of Zimbabwe covering rural and urban households.

6. Methods

6.1. Study site

The study was conducted in Bulawayo (Njube and Makokoba townships), Zimbabwe. Bulawayo is Zimbabwe’s second largest city with a total population of about 653,337 (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2012). The economy of Zimbabwe faces challenges such as liquidity for both local and foreign currency and lack of decent and secure employment. Households in the two townships are food insecure due to high unemployment rates. As of 2015 about 55% of the population in Bulawayo was employed and the majority (72%) of the employed earned between US$1 and US$400 per month, which was far below the poverty datum line (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2015). The population of Njube township is 26,978, with approximately 6 777 households (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2012). Makokoba has a total population of about 36,756 and 6 126 households (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2012). Makokoba was established in 1894 and is the oldest black township in Bulawayo. Njube came into existence in 1954 (Key informant 8, March 2017). The two townships are densely populated. Due to closure and scaling down of many companies and manufacturing industries in the city of Bulawayo, most households in the two townships have been exposed to extreme poverty and food insecurity. De-industrialisation of the manufacturing sector in Bulawayo has been triggered by lack of access to loans, low demand, low-capacity utilisation, lack of government support, unfavourable tax and labour laws, and accumulation of losses (Mbira, Citation2015). Poor households in Makokoba and Njube mainly depend on informal trade as their source of income.

6.2. Sampling and data collection methods

Data was collected between January and April 2017. The study utilised qualitative and quantitative research methods. Data was collected through a semi-structured questionnaire, household in-depth interviews and key informant interviews. A descriptive research design was adopted to examine the effectiveness of the cash transfers in improving access to food. Quantitative data is summarised in form of tables and figures and supported by in-depth narrative explanations. A semi-structured questionnaire, comprising of closed and open-ended questions, was used to collect qualitative and quantitative data respectively. A team of five researchers administered a semi-structured questionnaire to a total of 280 households out of 1600 cash transfer beneficiary households in the two townships. Probability sampling was used to select questionnaire respondents from beneficiaries of the cash transfer programme. Random sampling permits members of the study population to have equal chances of participating (Etikan & Bala, Citation2017). Probability sampling was employed to enable the researchers to generalise the quantitative findings in Bulawayo townships. Respondents were randomly selected from the HSCT beneficiary lists. Questionnaires were administered using IsiNdebele and chiShona languages. IsiNdebele and chiShona are the two common indigenous languages in Zimbabwe amongst other minority indigenous languages.

The structured sections of the questionnaire were used to gather demographic data, Household Dietary Diversity Scores (HDDS) and Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS). HDDS is used as a proxy measure of household food access. In line with HDDS the questionnaire was used to capture the number of food groups consumed by household in the previous 24 hours. HDDS utilises a total of twelve food groups and these are; cereals, white tubers and roots, vegetables, fruits, meat, eggs, fish and other seafood, legumes and nuts, milk and milk products, oils and fats, sugar and honey and beverages. The scores range from 0–12, low scores are associated with limited access to various food groups. The scale was used to group households into three categories (1–3, poor/low, 4 and 5, moderate and 6–12, good) of dietary diversity (McCordic & Frayne, Citation2017). This was important for the study in assessing the implications of cash transfers on household access to various food groups.

The questionnaire also captured data for Household Food Insecurity Access. HFIAS “measures core behaviours and experiences related to food sufficiency, access or food insecurity” (Alam et al., Citation2016, p. 4). HFIAS uses a 30-day reference period. Households were asked nine questions (worry about food supply, unable to eat preferred foods, eating smaller meals, unable to eat a variety of foods, eat fewer in a day, eat foods they really don’t want to eat, no food of any kind in the household, go to sleep hungry and, go a whole day and night without eating) to establish food insecurity based on food access. HFIAS scores were calculated for each household based on answers to nine frequency-of-occurrence questions designed to capture different components of the household experience of food insecurity in the previous four weeks. A higher score indicates a food insecure household. The minimum score is 0 and the maximum is 27.

From the 280 household questionnaire respondents, 50 were purposively selected (25 from each township) for in-depth semi-structured interviews. Data saturation was reached after conducting 43 interviews. Data saturation criterion was therefore used to achieve the sample size of 50. Interviews were stopped after reaching 50 respondents. In interviews, when the researcher begins to hear the same comments again and again, data saturation is being reached (Grady, Citation1998). We stopped interviewing more households after realising that data from additional interviews did not lead to new issues.

Non-probability (purposive) sampling also facilitated the identification of eleven key informants that were knowledgeable about cash transfers in Makokoba and Njube townships. comprising of personnel from Non-Governmental Organisations, World Food Programme, Department of Social Services, Mzilikazi District Administrator’s office, Bulawayo City Council, Bulawayo Progressive Residents Association, Bulawayo United Residents Association and ward-based Child Protection Committees. In-depth interviews were utilised to gather rich and comprehensive data on the role of cash transfers in alleviating household food insecurity.

This study was guided by standard social science research ethical considerations. Informed consent was sought from all study participants. Bulger (Citation2002) points out that the informed consent process is a very important aspect of research as it promotes rights of participants as autonomous beings to ensure that they are treated with justice and respect. Potential respondents were given adequate information relating to the purpose of the study. Participants were asked to sign a consent form. The researchers adhered to confidentiality and all responses are anonymous.

7. Findings and discussion

7.1. Respondents’ socio-economic demographics

Most (66%) beneficiary households were female headed. This is mainly due to high poverty levels among female headed households. This is confirmed by Schubert and Slater (Citation2006) who argues that households headed by women in Zimbabwe face a plethora of multiple disadvantages as they usually carry more burdens of caring for children, terminally ill and disabled family members. It has been observed that female-headed households constitute a disproportionate number of the poor and they experience greater extremes of poverty than male headed . Due to high poverty levels among female headed households they were a majority of beneficiaries of cash transfer programmes in Makokoba and Njube townships. Most (77%) beneficiary households’ incomes were less than US$50 per month. Another 19% had income between US$51 and US$100. Only 4% of the respondents had monthly income between US$101 and US$200. Households that had more than US$100 were dependent on formal employment. These households were included in the programme due to limitations (inclusion error) of the targeting systems employed. Poor households in the two townships have low purchasing power which inhibits access to adequate food. Such an environment of extreme poverty makes these households vulnerable to food insecurity, hence they were beneficiaries of cash transfer programmes.

Most (73%) households receiving cash transfers were dependent on informal activities for their livelihoods. Due to high unemployment levels in Bulawayo, poor households are largely dependent on informal activities. Fourteen percent (14%) of respondents reported that their households were dependent on casual labour for their income. An additional 9% of households were dependent on remittances. Most (82%) households had one member contributing to their household income while 16% of households had two members contributing. Most (73%) households were labour constrained as they are composed of children, elderly and chronically ill members.

7.2. Cash transfers and food access in Bulawayo townships

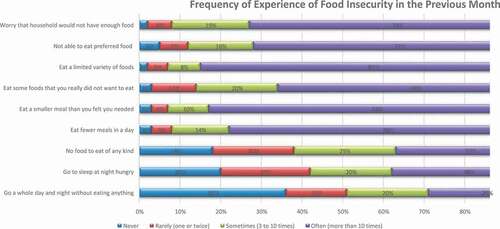

Poor households in Makokoba and Njube townships received cash transfers under the Harmonised Social Cash Transfer (HSCT) programme since 2014. The study examined the role of cash transfers in improving food access by beneficiary households. The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) was used to assess the degree of food access during the implementation of the cash transfer programme in the two townships. HFIAS scores derived from the study indicated that the majority of households benefitting from the cash transfer programme struggled to access food. Most sampled households had high HFIAS scores as shown in . High scores show that households were struggling to access food as indicated by being worried about food supply, unable to eat preferred foods, ate small meals, unable to eat a variety of foods, ate few meals in a day. Unstable food supply was also revealed by households who sometimes spent a whole day without eating and some even went to sleep hungry. About 30% of the households had scores ranging between 21 and 24, followed by 26% of households with scores ranging from 16 to 20. Twenty percent of households (20%) had scores ranging between 10 and 15. Twelve percent (12%) of the households had higher scores of 25 to 27. A few (8%) had scores between 4 and 9. These findings show that 72% of households had scores between 15 and 27. Therefore, for most households the transfers did not meaningfully improve quantities, preferences and quality of food items accessed by the urban poor households. In this regard, cash transfers did not meaningfully improve food access by the urban poor in the two townships. Cash transfers have not greatly improved the trade-based entitlement of poor urban households due to factors such as low transfer values and inconsistent distributions obstructed the effectiveness of the cash transfers.

Table 1. Frequency distribution of HFIAS scores

A greater part (73%) of households in Makokoba and Njube at one point during the previous month indicated that they were often worried that their families would not have enough food regardless of receiving cash transfers (see ). Sixty eight percent (68%) of the respondents also reported that they were not able to eat preferred food items on a regular basis. Many (58%) households also reported that they frequently went to bed hungry due to inadequate food. However, it is important to note that although households faced challenges in accessing, food most households were able to eat one meal a day. Only a few (29%) households reported that they often spent the whole day and night without eating. These findings reveal that cash transfers have nominally improved access to food in the two townships as households struggled to purchase adequate food. Cash transfers have therefore, narrowly improved the trade-based entitlement to food by beneficiary households.

The study also examined the role of cash transfers in improving food consumption behaviours of poor urban households. Cash transfers slightly increased the number of meals per day. In this regard, households in the two townships frequently skipped meals due to limited food access. An overwhelming (78%) proportion of households reported that cash transfers had minimally improved the number of meals consumed per day (see ). These findings are not in unison with studies in many developing countries which have established that households receiving cash transfers significantly improve the quality and quantity of food consumed (Bailey, Citation2013). One of the respondents highlighted that;

The money we receive is inadequate. We still struggle to eat two meals a day … . The money has not increased the number of meals consumed because urban problems are numerous (Household respondent 4, January 2017).

These findings are contrary to what has been observed in other countries where cash transfers improved access to food, thereby increasing the number of meals consumed (Bailey, Citation2013; Holmes & Bhuvanendra, Citation2013; Villanger, Citation2008). The HSCT programme did not improve significantly the number of meals for most households due to low transfer values and inconsistent distributions. The HSCT programme has slightly improved the exchanged entitlements of households in Makokoba and Njube townships. Poor households have failed to access adequate food due to insufficient exchange entitlement resulting from low value cash transfers.

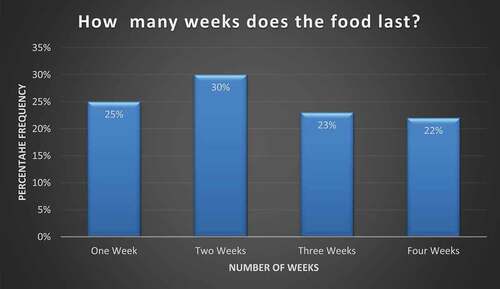

Most households reported that the food items they purchased using cash transfers did not last a month. The cash received by poor urban households in Makokoba and Njube was meant to cushion them for two months, yet it was hardly adequate for a month. This was worsened by an increase in food prices due to a currency crisis hastened by foreign currency shortages. For example, a 10 kg of unrefined mealie meal was US$6.40 up from US$5.90 (Financial Gazette, Citation2017). The cost of a food basket increased from US$133.06 (December 2016) to US$163.92 as of March 2017 (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2017). Consequently, due to low value cash transfers received by most households, increases in the number of meals consumed per day have largely been marginal.

In determining the extent to which the HSCT programme has ameliorated urban household food insecurity, household consumption behaviours were assessed in line with improvements in quantities of food consumed. Transfers in these two townships slightly increased quantities of meals consumed as they did not significantly enhance exchange entitlement to enable access to adequate food. As households access more food, quantities of food consumed are expected to increase. Most (83%) households reported that they frequently ate small meals due to inadequate food supplies (see ). One household respondent highlighted that;

We still eat small portions. Nothing has changed … The money that Social Welfare gives us is not adequate. As it is, we do not know when are going to receive the money. The food items that I buy are not adequate (Household respondent 5, January 2017).

Cash transfers have not momentously improved access to food due to inconsistent distributions. As such, beneficiary households continued to have limited access to food. More so, the cash transfer value did not enable households to purchase adequate food necessary for increasing quantities of food consumed. This is contrary to what has been observed in several developing countries which have implemented cash and transfers that have enabled beneficiaries to increase the quantities of food consumed. For example, Villanger (Citation2008) and Gangopadhyay et al. (Citation2015) found that cash transfers improve food consumption behaviours and the number of severely food insecure households are reduced. The low value and inconstant distributions of have inhibited poor households in Njube and Makokokoba from strengthening their trade-based entitlements through cash transfers.

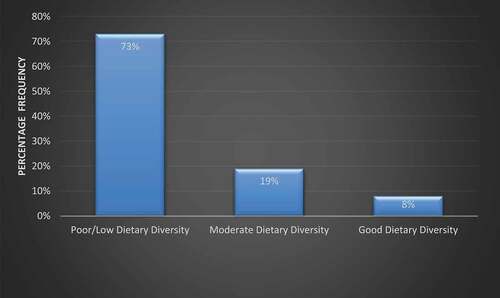

The study also investigated implications of cash transfers on household dietary diversity. Households are expected to buy food items from a variety of food groups when their trade-based entitlements permit them to do so. Household Dietary Diversity Scores (HDDS) were calculated by summing the number food groups consumed by households in the last 24 hours (see ). These food groups are; cereals, white tubers and roots, vegetables, fruits, meat, eggs, fish and other seafood, legumes and nuts, milk and milk products, oils and fats, sugar and honey and beverages. HDDS range from 0–12, low scores are associated with limited access to various food groups (poor dietary diversity). Dietary diversity is an important indicator of household food security as it measures household food access and the quality of food consumed (Jones et al., Citation2013). It also provides a reflection of household economic ability to access a variety of food groups (Powell et al., Citation2017).

The Household Dietary Diversity Score was also used to measure household food access. HDDS utilises a total of twelve food groups and these are; cereals, white tubers and roots, vegetables, fruits, meat, eggs, fish and other seafood, legumes and nuts, milk and milk products, oils and fats, sugar and honey and beverages. Food secure households are expected to consume more food groups. A significant proportion (73%) of households in the two townships had a poor dietary diversity. Such households consumed between 1 and 3 food groups. An additional 19% of the households had moderate household dietary diversity as they consumed food items that belonged to 4 or 5 food groups. Only 8% of the households had a good dietary diversity and they accessed between 6 and 8 food groups. However, the food items were purchased in small quantities, hence they did not last longer. Households reported that they purchased food items that they considered essential due to limited household income. In other urban settings, studies have found that cash transfers enhance access to various food groups. For example, in Guinea an evaluation conducted in Conakry city by Smith & Mohiddin (2015) concluded that cash transfers improved access to various food groups as beneficiary households spent much of the income on food consumption (especially in protein and dairy products). Similarly, results from a study done by Kroll et al. (2012) provides evidence that transfers led to a reasonable dietary diversity with an average of eight food groups consumed by households in poorer areas of Johannesburg. Most households in these urban settings spent a greater proportion of their cash transfer resources in accessing food from various food groups. In the two Bulawayo townships, most households had poor dietary diversity regardless of receiving cash transfers.

Cash transfers did not significantly improve the food purchasing power of households to enable them to access food items from fish, meat, dairy, fruits, legumes, roots and tubers, and eggs food groups (see above). Food items that belonged to these food groups were also not considered a necessity by most households due to limited household income. Insignificant proportions (fruits 15%, meat 11%, milk and milk products 10%, legumes 7%, roots and tubers 3%, and fish 3%) of households had consumed food items from such food groups. No household indicated that they had consumed eggs. These findings are contrary to many studies done in Latin America and other African countries where cash transfers increased the consumption of foods rich in protein, fruits and vegetables (Bailey, Citation2013). These results are in unison with Jones (Citation2015) who argues that food insecure households have less diverse diets as there are less likely to consume meat and dairy products at all.

Table 2. Food groups consumed

In addition to the above, a few households used cash transfers to buy least consumed food items such as meat on the day of distribution. It is important to note that food items that were purchased did not last the expected two months. highlights that, for a majority (74%) of households the food items lasted from one week to three weeks. Only 22% of households reported that the food items bought lasted four weeks. This was determined by household sizes and proportion of cash transfers used to purchase food commodities. Studies have shown that large households limit poor urbanites from accessing various food groups (Gaines et al., Citation2014). Low household purchasing power and poverty are major factors that limit access to various food groups (Kennedy et al., Citation2013). Since households received money that was less than the cost of an average food basket, it is therefore impossible for such low value cash transfers to enhance dietary diversity for ultra-poor households.

7.3. Barriers of the effectiveness of cash transfers in Bulawayo townships

Insufficient monitoring of household demographics has hampered the effectiveness of the HSCT programme in Njube and Makokoba townships. In-depth interviews with key informants revealed that registrations were done in 2014 and since then the government did not update household data in line with demographic changes. This is despite the fact that many demographic changes had occurred in most of the households. Therefore, increases or decreases in household members have not been met with adjustments in amounts received. It emerged that a significant number of households with more than one member received USD$10 per month. For example, twenty percent (20%) of households that had members between four and nine reported that their monthly allocation was USD$10 (instead of USD$25). More so, 53% of households with members between four and nine were recipients of amounts (US$15) meant for households with two people. Another 68% also reported that they were receiving USD$20 a month instead of USD$25 which is entitled to households with four and above members. Furthermore, 3% of households that had one to three members received USD$25 meant for households with four members and above. Insufficient monitoring resulted in households receiving money that does not match with the household sizes. Effective monitoring plays a major role in enhancing the effectiveness of development programmes (Kariuki, Citation2014). The efficiency of cash transfer programmes depends on effective mechanisms for monitoring beneficiaries (De Groot et al., Citation2017). Therefore, consistent monitoring of household demographics would assist in taking note of changes in household sizes.

In examining the extent to which cash transfers enhance household purchasing power (enabling entitlement to food), economic and food purchasing value of the HSCT amounts were assessed within the prevailing market conditions. A majority (59%) of households were entitled to USD$25 per month. An additional 22% of households received USD$10, while other households received USD$20 (12%) and USD$15 (6%). Beneficiary households received money that was far less than the cost of a basic food basket of an average five-member household, which stood (as of March 2017) at USD$163.92 per month (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, Citation2017). In this regard, the findings reveal that for most households cash transfer values contributed between 6% and 15% towards accessing a basic food basket. This implies that such low food purchasing value transfers have limited potential of alleviating urban household food insecurity. Therefore, the HSCT programme has not greatly boosted the purchasing power of urban food insecure households. As a result, ultra-poor cash transfer beneficiary households in the two townships were still financially constrained, which limits their trade-based entitlement to adequate food. However, studies have shown that the size of cash transfer must be sufficient to make substantial contribution to household income (Holmes & Bhuvanendra, Citation2013).

Another key factor hampering the effectiveness of cash transfers is the cash disbursement mechanism used by the Department of Social Services. The cash-in-transit mechanism was utilised to distribute cash transfers to households. This mechanism is not flexible as it entails distributing cash transfers in specific times per township. Since such distributions lasted about two hours per point, this meant that recipients that arrived late could not access their entitlements for that month. The situation was further worsened by the fact that the Department of Social Services had no direct communication with beneficiaries. It relied on members of the Child Protection Committees (volunteers) to inform beneficiaries about the distribution dates and times. In some cases, these volunteers did not relay the information to all beneficiary households. For transfers to be effective, there is need for adopting flexible cash distribution mechanisms.

The effectiveness of the HSCT programme has also been deterred by the automatic removal of households from the database of beneficiaries. A key informant, pointed out that “if a household miss payment for three consecutive distributions, automatically the HSCT Management Information System removes the name from the database.” (Key informant 1, April 2017). It was noted that households were removed from the programme regardless of reasons for missing distributions. From a variety of explanations, it was noted that households missed payments if recipients had travelled or if the recipient is hospitalised during the period of distributions. This has reduced the effectiveness of cash transfers as deserving households are removed from the programme from time to time.

Irregularities in targeting of beneficiaries further hindered the effectiveness of the HSCT programmes in Makokoba and Njube townships. Targeting plays a significant role in increasing the effectiveness of cash transfers. Inclusion and exclusion errors were noted to be hampering effectiveness of the HSCT programme. It emerged that some households that were not ultra-poor were also benefitting from the programme yet several ultra-poor households were not part of the programme. Such families had household heads or family member/s that were formally employed. For example, one of the beneficiaries was employed as a general hand at a local central (Mpilo) hospital. In another case the household head was employed as a security guard. Such households had a monthly income that was approximately USD$250 per month. This was in contrast to the selection criteria of the HSCT programme. Targeting is important for correctly and efficiently identifying poor households (Bailey, Citation2013). Targeting is important as it ensures that cash transfers are directed to defined populations on time and in right quantities.

Lastly, irregular distributions also thwarted the effectiveness of the HSCT cash transfer programme. De Groot et al. (Citation2017) have argued that for transfers to be effective they should be distributed timely. Findings from previous research also shows that frequency and predictability of transfers play a pivotal role in alleviating household food insecurity (Peprah et al., 2017; Hagen-Zanker et al., 2017). Cash transfer distributions in Njube and Makokoba have been done inconsistently, thereby inhibiting their effectiveness in ameliorating urban household food insecurity. This resonates with available evidence which shows that predictable and regular transfers of cash are effective in smoothing households’ consumption (Selvester et al., 2012; Gangopadhyay et al., Citation2015). The frequency and regularity of the payments play a critical role in the effectiveness of cash transfers in alleviating household food insecurity (Bastagli et al., Citation2016).

8. Conclusion

Cash transfers programmes have been implemented in Bulawayo townships to strengthen the purchasing power ultra-poor households. However, empirical evidence from the study has established that cash transfers have not significantly reduced household food insecurity in Makokoba and Njube townships. Evidence indicates that cash transfers have not enhanced food consumption of poor households to a level that exceeds the food poverty line. While cash transfers have the potential of alleviating urban household food insecurity in the two townships, several design and implementation drawbacks have hindered their effectiveness in improving the endowment sets of beneficiary households.

First of all, cash transfers are of low value hence they have slightly boosted the exchange or trade-based entitlement to food purchasing power of poor household. For cash transfers to improve food consumption behaviours of poor households, the transfer value should meaningfully increase their exchange or trade-based entitlement. Increased food purchasing power enables households to access adequate food. Secondly, distributions are done irregularly and this has hindered poor households from having stable access to food. Thirdly, poor communication with beneficiaries combined with weak targeting systems have meant that some poor households fail to receive the transfers. Fourthly, a rigid distribution mechanism and automatic removal of households from beneficiary database have also reduced the effectiveness of these cash transfers. Lastly, weak monitoring and failure to update beneficiary demographics have resulted in many households receiving insufficient monies.

In view of the above, addressing urban food insecurity that continues to be on the rise in these townships, requires a revamp in design and implementation processes. The government of Zimbabwe and its development partners should increase the transfer value of the cash transfers to have significant changes on household purchasing power. The cash transfers should also be distributed regularly so as to improve the exchange entitlements of the poor households to enable them to access food. The government should also consider the use of food vouchers to allow poor households to have stable access to comprehensive food baskets. Vouchers are coupons with monetary value that enable households to access food in local shops. They are also key as transfer entitlements for improving access to food. A voucher system is a tried and tested transfer disbursement mechanism that has been used by the World Food Programme and NGOs in response to food insecurity in countries such as, Haiti, Ecuador, Niger and Uganda. In order to effectively address urban household food insecurity, transfers meant for improving access to food should be implemented in conjunction with income generating projects to support poor urbanites to meet non-food basic needs.

These findings can be generalised to other urban areas particularly the high-density areas (townships) in Zimbabwe experiencing an increase in poor households who live below the food poverty line. Study findings can assist in improving the design and implementation of cash transfer programmes in urban Zimbabwe. The study has given some insights on factors (e.g., cash transfer value, beneficiary verification, regular distributions, communication channels) hindering the effectiveness of cash transfers which can be generalized to other urban contexts in countries of the global South.

9. Limitations of the study

The researchers identified two limitations of this study. The first limitation related to quantitative data collection methods which involved recalling of household experience of food insecurity. Household Dietary Diversity Scores (HDDS) and Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) questionnaires required households to recall their food consumption behaviours over a seven-day and thirty-day period respectively. To minimise exaggerated and biased data, some of the questions were asked several times in different ways. In some cases, questionnaires were administered in the presence of two or three household members to improve accuracy of the data provided. The researchers also cross checked some of the responses with the cost of some food items in formal markets.

The second limitation is that the study was carried out in Bulawayo townships, yet the HSCT programme was implemented in 10 provinces of Zimbabwe. In this regard there is need for further research to be conducted in other urban areas in Zimbabwe for comparison of findings on food consumption behaviors since most studies have been carried in rural settings. However, the findings can be generalized to other urban areas in Zimbabwe due to similarities in design and implementation of the HSCT programme as well as the structural similarities exhibited by the households residing in townships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sibonokuhle Ndlovu

Dr Sibonokuhle Ndlovu is a senior lecturer, Department of Development Studies, Lupane State University, Zimbabwe. Research interests: Food Security, Social Protection, Gender, and Climate Change.

Dr Moreblessings Mpofu is a senior lecturer, Department of Property Studies and Urban Design, National University of Science and Technology, Zimbabwe. Research interests: Livelihoods, Gender, and HIV and AIDS.

Professor Philani Moyo, is a Full Professor of Development Studies. He is the Director of the Fort Hare Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Fort Hare, South Africa. Research interests: Sustainable Food Systems, Food Sovereignty, Climate Smart Development, Migration and Development

Dr Keith Phiri is a senior lecturer, Department of Development Studies, Lupane State University, Zimbabwe. Research interests: Climate Change and Livelihoods, Food Security, Gender, and Natural Resource Governance.

Dr Thulani Dube is a senior lecturer, Department of Development Studies, Lupane State University, Zimbabwe. Research interests: Livelihoods, Climate Change, Gender, Monitoring and Evaluation.

References

- Alam, M., Siwar, C., Wahid, A. N. M., & Talib, B. A. (2016). Food security in Malaysian poor households. Urban and Regional Development Studies, 28(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/rurd.12042

- Alderman, H. 2014. “Can transfer programs be made more nutrition sensitive?” international Food Policy Research Institute, Discussion Paper 1342. Health, and Nutrition Division of the International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC Available from: http://ebrary.ifpri.org. [15 June 2016].

- Alemu, G. (2007). Revisiting the entitlement approach to famine: Taking a closer look at the supply factor-a critical survey of the literature. Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, 23(2), 95–129. https://doi.org/10.1353/eas.2007.0006

- Angeles, G., Chakrabarti, A., Handa, S., Otchere, F., & Spektor, G. (2018) Zimbabwe’s harmonised social cash transfer programme end-line impact evaluation report. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina. https://transfer.cpc.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/HSCT-Endline-Report_Final-v2.pdf

- Bailey, S. (2013). The impact of cash transfers on food consumption in humanitarian settings: A review of evidence. Canadian Foodgrains Bank. Retrieved March 15, 2018, from. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/cfgb—impact-of-cash-transfers-on-food-consumption-may-2013-final-clean.pdf

- Bailey, S., & Hedlund, K. (2012). The impact of cash transfers on nutrition in emergency and transitional settings: A review of evidence. Humanitarian Policy Group Overseas Development Institute

- Bastagli, F., Hagen-Zanker, J., Harman, L., Barca, V., Sturge, G., Schmidt, T., & Pellerano, L. (2016). Cash transfers: What does the evidence say?. A rigorous review of programme impact and the role of design and implementation features. Oversees Development Institute. Retrieved June 18, 2017, from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/10749.pdf

- Battersby, J. (2013). Hungry cities: A critical review of urban food insecurity research in Sub-Saharan African cities. Geography Compass, 7(7), 452–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12053

- Bulger, R. E. (2002). Research with Human Beings. In R. E. Bulger, I. Heitman, & J. Reiser (Eds.), The ethical dimensions of the biological and health sciences (pp. 117–125). Cambridge University Press.

- Chimhowu, A. (2009). Moving forward in Zimbabwe: Reducing poverty and promoting productivity. Brooks Poverty Institute.

- Crush, J., & Frayne, B. (2010). Pathways to insecurity: Urban food supply and access in Southern African cities no. 03. Queen’s University and African Food Security Urban Network. Retrieved March 18, 2018, from. http://www.afsun.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/AFSUN_3.pdf

- De Groot, R., Palermo, T., Handa, S., Ragno, L. P., & Peterman, A. (2017). Cash transfers and child nutrition: Pathways and impacts. Development Policy Review, 35(5), 1–23. http://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12255

- Department for International Development (DFID). (2011). Cash transfers: Evidence paper. DFID policy division. Retrieved January 18, 2017, from, http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/cash-transfers-evidence-paper.pdf

- Dodson, B., Chiweza, A., & Riley, L. (2012). Gender and food insecurity in Southern African cities. Urban Food Security Series No. 10. Queen’s University and African Food Security Urban Network.

- Etikan, I., & Bala, K. (2017). Sampling and sampling methods. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 5(6), 215‒217. https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2017.05.00149

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. (2014) The economic impacts on cash transfers in SSA. Retrieved April 20, 2017, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4194e.pdf

- Food and Agriculture Organisation, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) & World Food Programme. (2013). The state of food insecurity in the world 2013. The multiple dimensions of food security. Retrieved November 20, 2015, www.fao.org/publications/sofi/2013/en

- Food and Agriculture Organisation, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) & World Food Programme. (2015) The state of food insecurity in the world 2015.Meeting: The 2015 international hunger targets: Taking stock of uneven progress. FAO. Retrieved March 3, 2017, from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4646e.pdf

- Food and Nutrition Coucil. (2014). Zimbabwe national nutrition strategy 2014-2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018, from http://fnc.org.zw/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/3.-Zimbabwe-National-Nutrition-Strategy-2014-2018.pdf

- Frayne, B., Crush, J., & McLachlan, M. (2014). Urbanization, nutrition and development in Southern African cities. Food Security, 6(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0325-1

- Gaines, A., Robb, C. A., Knol, L., & Sickler, S. (2014). Examining the role of financial factors, resources and skills in predicting food security status among college students. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(4), 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12110

- Gandure, S., Drimie, S., & Faber, M. (2010). Food security indicators after humanitarian interventions including food aid in Zimbabwe. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 31(4), 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651003100405

- Gangopadhyay, S., Lensink, R., & Yadav, B. (2015). Cash or in-kind transfers? Evidence from a randomised controlled trial in Delhi, India. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(6), 660–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.997219

- Garcia, M., & Moore, C. M. T. (2012). The cash dividend: The rise of cash transfer programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank. Retrieved September 20, 2017, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2246

- Financial Gazette (2017, March 9). Price Hikes hit Zimbabwe. Financial Gazette, Retrieved September 20, 2017, from http://www.financialgazette.co.zw/price-hikes-hit-zimbabwe

- Gentilin, U.2015. Entering the city: Emerging evidence and practices with safety nets in urban areas. Social Protection and Labour Discussing Paper 1504, IBRD World Bank. Retrieved June 20, 2017, https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/…/Entering-the-City-Emerging-Evidence-and-Practices

- Gentilini, U., Grosh, M., Rigolini, J., & Yemtsov, R. (2020) Exploring universal basic income: A guide to navigating concepts, evidence, and practices, international bank for reconstruction and development/The World Bank, Retreived April 20, 2021, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32677

- Government of Zimbabwe. (2013). Zimbabwe agenda for sustainable socio-economic transformation. Government of Zimbabawe. Retrieved September 28, 2017, from http://www.veritaszim.net/node/930

- Grady, M. P. (1998). Qualitative and action research: A practitioner handbook. Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

- Grugel, J., & Riggirozzi, P. (2012). Post neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and reclaiming the state after crisis. Development and Change, 43(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01746.x

- Hall, A. (2012). The last shall be first: Political dimensions of conditional cash transfers in Brazil. Journal of Policy Practice, 11(1–2), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15588742.2012.624065

- Holmes, R., & Bhuvanendra, D. (2013). Social protection and resilient food systems: The role of cash transfers. Oversees Development Institute. Retrieved September 18, 2016, from https://www.odi.org/publications/7887-social-protection-and-resilient-food-systems-role-cash-transfers

- Hugo, K., & Gaia, E. (2011). Social policy and poverty: An introduction 1. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(3), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00786.x

- Johnston, D. (2015). Paying the price of HIV in Africa: Cash transfers and the depoliticisation of HIV risk. Review of African Political Economy, 42(145), 394–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2015.1064815

- Jones, A. D. (2015). Household food insecurity is associated with heterogeneous patterns of diet quality across urban and rural regions of Malawi. World Medical and Health Policy, 7(3), 234–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.152

- Jones, A. D., Ngure, F. M., Pelto, G., & Young, S. L. (2013). What are we assessing when we measure food security? A compendium and review of current metrics. American Society for Nutrition Adv Nutrition, 4(5), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.113.004119

- Kariuki, J. P. (2014). An exploration of the guiding principles, importance and challenges of monitoring and evaluation of community development projects and programmes. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 5(1), 140–147.Retrieved March 15, 2021, from http://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_5_No_1_January_2014/17.pdf

- Kennedy, S., Ficth, C. A., Warren, J. R., & Drew, J. A. R. (2013). Food insecurity during childhood: Understanding persistence and change using linked current population survey data, University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series, DP2013-03. Retrieved March 23, 2017, from http://www.ukcpr.org/Publications/DP2013-03.pdf

- Legwegoh, A., Borelkamga, Y., Lekeufackmartin, L., & Njukeng, P. (2020). Food security in Africa’s secondary cities: No. 3. Dschang. African Food Security Urban Network, Retrieved January 10, 2021, from http://www.afsun.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Afsun29.pdf

- Maluccio, J. A. (2010). The impact of conditional cash transfers on consumption and investment in Nicaragua. The Journal of Development Studies, 46(1), 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380903197952

- Mbira, L. (2015). The de-industrialization of Bulawayo manufacturing sector in Zimbabwe: Is the capital vacuum to blame?. International Journal Of Economics Commerce and Management, 3(3), 1–14.Retrieved January 11, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318014955_THE_DE-INDUSTRIALIZATION_OF_BULAWAYO_MANUFACTURING_SECTOR_IN_ZIMBABWE_IS_THE_CAPITAL_VACUUM_TO_BLAME

- McCordic, C., & Frayne, B. (2017). Household vulnerability to food price increases: The 2008 crisis in urban Southern Africa. Geographical Research, 55(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12222

- Miller, C. M., Tsoka, M., & Reichert, K. (2011). The impact of the social cash transfer scheme on food security in Malawi. Food Policy, 36(2), 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.11.020

- Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare. (2014). Manual of operations for the Zimbabwe harmonised social cash transfer programme, unpublished

- Ministry of Public Services, Labour and Social Welfare. (2016). National social protection policy framework for Zimbabwe, ministry of public services. Labour and Social Welfare, Unpublished

- Mokomane, Z. (2013). Social protection as a mechanism for family protection in sub-Saharan Africa 1. International Journal of Social Welfare, 22(3), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2012.00893.x

- Ndlovu, S., Mpofu, M., & Moyo, P. (2019). Debunking the effectiveness of in-kind transfers in alleviating urban household food insecurity in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Development Southern Africa, 37(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2019.1584031

- Oduro, R. (2015). Beyond poverty reduction: Conditional cash transfers and citizenship in Ghana. International Journal of Social Welfare, 24(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12133

- Parsons, R. W. K. (2007). After Mugabe goes – The economic and political reconstitution of Zimbabwe. The South African Journal of Economics, 75(4), 599–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2007.00147.x

- Pega, F., Liu, S. Y., Walter, S., & Lhachimi, S. K. (2015). Unconditional cash transfers for assistance in humanitarian disasters: Effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low-and middle-income countries (Review). The Cochrane Library, (9), John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.

- Pega, F., Walter, S., Liu, S., Pabayo, R., Lhachimi, S. K., & Saith, R. (2014). Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: Effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11(11), CD011135. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011135.pub2

- Powell, B., Kerr, R. B., Young, S. L., & Timothy, J. T. (2017). The determinants of dietary diversity and nutrition: Ethnonutrition knowledge of local people in the East Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. Journal of Ethnobiology and Enthnomedicine, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0150-2

- Rabinovich, L., & Diepeveen, S. (2015). The design of conditional cash transfers: Experiences from Argentina’s universal child allowance. Development Policy Review, 33(5), 637–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12127

- Ravillion, M. (2016). The economics of poverty. In History, measurement and policy. Oxford University Press.

- Ruel, M. T., Garrett, J. L., & Yosef, S. (2017). “Food security and nutrition: Growing cities, new challenges.” International Food Policy Research Institute. In Global food policy report.International Food Policy Research Institute. 24-32. Retrieved January 10, 2018, from https://www.ifpri.org/publication/food-security-and-nutrition-growing-cities-new-challenges

- Saad-Filho, A. (2015). Social policy for neoliberalism: The Bolsa familia programme in Brazil. Development and Change, 46(6), 1227–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12199

- Sandberg, S., & Tally, E. (2015). Politicisation of conditional cash transfers: The case of Guatemala. Development Policy Review, 33(4), 503–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12122

- Scarlato, M., D’Agostino, G., & Capparucci, F. (2015). Evaluating CCTs from a gender perspective: The impact of Chile solidario on women’s employment prospect. Journal of International Development, 28(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3124

- Schubert, B., & Slater, R. (2006). Social cash transfers in low-income African countries: Conditionalor unconditional?. Development Policy Review, 24(5), 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2006.00348.x

- Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. Clarendon Press.

- Simiyu, R. R., & Foeken, D. W. J. (2014). Urban crop production and poverty alleviation in Eldoret. Kenya: Implications for Policy and Gender Planning, Urban Planning, 51(12), 2613–2628.

- Tolossa, D. (2010). Some realities of the urban poor and their food security situations: A case study of Berta Gibi and Gemechu Safar in the city of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Environment and Urbanisation, 22(1), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247810363527

- Tumusiime, E. (2015). Do early cash transfers in a food crisis enhance resilience? Evidence form Niger. Development in Practice, 25(2), 174–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1001320

- United Nations Development Programme. (2012). Africa human development report 2012; towards a food secure future.

- United Nations Development Programme China Office (2017). Universal basic income: A working Paperhttps://www.researchgate.net/profile/Enrique-Valencia-Lopez/publication/331629579_UNDP_Universal_Basic_Income/links/5c836e8c92851c6950641ae1/UNDP-Universal-Basic-Income.pdf

- United Nations International Children Emergency Fund. (2020). Zimbabwe social protection budget brief, https://www.unicef.org/esa/media/6511/file/UNICEF-Zimbabwe-2020-Social-Protection-Budget-Brief.pdf

- Villanger, E. (2008). Cash transfers contributing to social protection: A review of evaluation findings. Forum for Development Studies, 35(2), 221–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2008.9666410

- Vincent, K., & Cull, T. 2009. Impacts of social cash transfers: Case study evidence across Southern Africa. Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Económicos. Retrieved September 1, 2016, www.iese.ac.mz/lib/publication/II_conf/CP47_2009_Vincent.pdf

- Yeboah, F. K., Kaplowitz, M. D., Kerr, J. M., Lupi, F., & Thorp, L. G. (2015). Sociocultural and institutional contexts of social cash transfer programs: Lessons from stakeholders’ attitudes and experiences in Ghana. Global Social Policy, 6(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018115600039

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. 2012. Zimbabwe population census report, 2012.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. 2015. 2014 labour force survey.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2017). Poverty analysis.

- Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee. (2016). Urban livelihoods assessment report 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017, from https://reliefweb.int/report/zimbabwe/zimbabwe-vulnerability-assessment-committee-zimvac-2016-urban-livelihoods-assessment