Abstract

The social construction of gender has profound implications on how individuals of different gender identities perceive health and formulate health-related decisions. An online survey experiment (N = 262) was conducted using implicit association test (IAT) to examine gender stereotypes on two preventative health behaviors—lung cancer screening and family planning—and how these stereotypes interact with gender identity to impact information-seeking intentions. Lung cancer screening was viewed to be significantly more related to men, while family planning was more linked to women. Female participants showed stronger stereotypical perceptions regarding the two preventive behaviors than their male counterparts. While both male and female participants who believed more in the gender stereotype on lung cancer screening reported decreased intention to seek relevant health information, gender stereotypes interacted with participant gender identity in influencing intention to seek information on family planning. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study informs health workers, policymakers, campaign organizers, media workers, and the public about the influence of gender stereotypes on people’s intentions of seeking health information about particular preventative health behaviors. Even though both males and females can be diagnosed with lung cancer and should take equal responsibility in family planning, this paper reveals that lung cancer screening was considered more related to males and family planning to females using implicit association tests. Moreover, these gender stereotypical associations and individuals’ self-identified gender identities (e.g., male vs. female) have a significant impact on individuals’ intention to seek relevant information, such that individuals with higher levels of stereotypical associations demonstrated less intention to seek information for illnesses they do not perceive to be relevant to themselves. The findings of this research study call for more attention to gendered messages that run through health narratives.

1. Introduction

Our health is socially bound. From smoking advertisements to planned parenthood campaigns, our evaluations regarding who is susceptible to which health problems and who should take action under what responsibilities are all collectively shaped (Fennell, Citation2011; Kimport, Citation2018). When social constructions get integrated and consolidated in human minds, stereotypes arise as a result (W. Courtenay, Citation2000). Scholars found the concerning ramifications of gender stereotypes on various health issues, such as smoking being framed as a masculine activity (Collins, Citation2005). The effects of gender stereotypes on health are further compounded by the social constructions of gender itself, that is, how men and women are expected to act. Together, they generate a series of profound impacts on individual decision-making processes regarding health. While a growing body of scholarship has discussed the impact of gender stereotypes in health (e.g., Pederson & Vogel, Citation2007; Vogel et al., Citation2007), very few have examined such impact at the intersection of gender stereotypes and gender identity.

Using an implicit association test (IAT), this study examines how stereotypical beliefs on two highly gendered health preventative behaviors—lung cancer screening (masculinized) and family planning (feminized)—interact with individuals’ self-identified gender identities (male vs. female) to influence their intention to seek relevant health information. Understanding gender and gendered perceptions of a variety of health problems has profound implications on illuminating a more nuanced picture as to how individuals’ health-related decisions are closely intertwined with the social constructions of gender and offers practical insights to policymakers, health organizations, and healthcare professionals on improving health inequality through reconstructing social portrayals of gender in health.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Gender, sex, and health

While most research focuses on sexual differences in health, sex and gender have been used interchangeably in the literature on illness and medical behaviors without being differentiated as two distinct concepts. As Butler (Citation1988) proposed the idea of gender as fluid and unstable “performance,” one’s gender is performed based upon the socialization process and social norms regarding that gender as a result of social and cultural constructions. Gender identity, as a socially constructed idea, is a person’s identification as male, female, queer, gender fluid, etc. In contrast to the flexible nature of gender, sex is a pre-determined biological difference upon birth. Discussing gender and sex in relation to health, Payne (Citation2001) noted that sex referred to one’s hormones, reproductive system, or other biological traits; yet gender meant one’s health behavioral pattern associated with their socially or culturally constructed identity (e.g., social expectations of how men should exercise).

Heise et al. (Citation2019) investigated the relation between heath and gender norms. They noted that individuals’ health could be influenced by one’s biological sex, such as diseases of sex-specific organs; however, they also underlined that there were gender-related health differences: individuals would act differently according to their socially assigned roles and, therefore, expose themselves to different health risks. In this regard, certain masculine norms can discourage males from seeking help from others while facing physical illness and emotional distress (Fleming & Agnew-Brune, Citation2015), while females are more likely to seek relevant information and assistance due to the expectations that females are caring and nurturing (W. Courtenay, Citation2000; Mahalik et al., Citation2007). Sometimes, individuals’ sex and gender identities can play significant parts in people’s health behaviors at the same time (Krieger, Citation2003). For instance, while males and females are at different risk levels of the diseases due to biological differences (Rubin et al., Citation2020), when facing the same diseases, one’s attitude towards help-seeking and information-seeking influenced by gender norms can also lead to different health outcomes (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2007). Even though females are found to be more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer because of genetic reasons (Rubin et al., Citation2020), their health outcomes can still be improved when they pay more attention to relevant health information and seek medical help as needed. Simultaneously, individuals’ perception of whether the disease is related to themselves also affects their intention to seek information and care.

Andermann (Citation2010) then underlined that the expectations of one’s behaviors built upon socially constructed ideas could impact individuals’ health outcomes. One manifestation of various social constructions at the individual level is the corresponding stereotypes created in individual minds. Human beings develop cognitive schemata—pre-registered cognitive scripts that guide our reactions to presented objects (McVee et al., Citation2005)—to process and interpret gender-related information according to how it has been socially shaped (Bem, Citation1981). Cognitive schemata work as systematic frameworks and networks, and the perceptual cues embedded in incoming information can elicit elaborate concepts and meanings associated with the schemata (Littlejohn & Foss, Citation2009). Within the organized cognitive schemata, individuals link particular information, such as illnesses, to certain gender identities and further assign meanings to these linkages when encountering relevant cues (Bem, Citation1981). These links made are, thus, cognitive associations. As these cognitive schemata consolidate, stereotypes emerge as a result, which has profound implications on individual behaviors. Gender stereotypes specifically refer to the overgeneralized beliefs about individuals based on their gender (Casad & Wexler, Citation2017).

Among various preventative health behaviors recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Citation2020a), two preventative behaviors—lung cancer screening and family planning—have been repeatedly identified as potentially gendered due to how they were conventionally, socially constructed (e.g., Collins, Citation2005; Fennell, Citation2011). In the context of health communication, the health messages themselves then involve gender cues. However, little research has examined how these social constructions would impact individuals of different gender identities in terms of their willingness to seek more information on lung cancer screening and family planning—a key predictor of individuals’ behavioral compliance with health recommendations.

2.2. Gender and lung cancer screening

While the causal relationship between lung cancer and tobacco smoking has been found irrespective of gender (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Citation2020b), smoking has been repeatedly framed as the embodiment of masculinity (Collins, Citation2005). Among the U.S. population, men were found to be more likely to engage in risky behaviors (Copenhaver et al., Citation2000) and various addictions (Mandal, Citation2007) compared to women, including smoking (W. Courtenay, Citation2000). In a 2018 report on tobacco-use-related cancers, men were found at a much higher rate of diagnosis than women (Gallaway et al., Citation2018). Cui et al. (Citation2018) examination on three Asian cities also reported males to be 30 times more likely to smoke than females.

The grave danger looming in the socially constructed tie between smoking and masculinity (Kerr-Corrêa et al., Citation2007) and the stereotypical image of “typical smokers” (McCool et al., Citation2004) is the potentially gendered perceptions regarding the susceptibility to lung cancer. As the Reasoned Action Theory posited (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975), individuals, dictated by their cognitive associations regarding gender and lung cancer would reasonably take different actions to prevent lung cancer even though reality checks suggest a different picture. Among never-smokers, women reported a higher diagnosis rate of lung cancer than men (Clément-Duchêne & Wakelee, Citation2010) due to a constellation of risk factors, such as environmental tobacco smoke, cooking oil fumes, air pollutants, and family medical history (Samet et al., Citation2009). A study in Europe revealed more lung-cancer-caused deaths among non-smoker women than non-smoker men due to exposure to second-hand smoking (Tredaniel et al., Citation1997). A meta-analysis by Jia et al. (Citation2017) further demonstrated that the lung cancer rates of non-smoker women were largely associated with their responsibility for domestic housework like cooking. Even so, Zambon et al. (Citation2017) found significantly lower female participation in lung cancer screening programs. Thus, the social constructions of males as the typical smokers and hence more susceptible to lung cancer do not only have ramifications on individuals’ perceptions of health risks but also on their likelihood of taking preventive actions against lung cancer.

2.3. Gender and family planning

According to WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs, Knowledge for Health Project (Citation2018) and Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Citation2020c), family planning includes contraception, pregnancy testing, counseling, infertility services, and sexually transmitted diseases (STD) services. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s (Citation2020c) definition of quality family planning services involves the preconception health services in STD and mental health that are considered influential to men’s and women’s ability to conceive and their reproductive health outcome. Family planning then helps improve health by preventing STD, maternal deaths, unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and high-risk pregnancies (Canning & Schultz, Citation2012). In that, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Citation2020c) recommends individuals from 13 to 64 years old to actively participate in family planning services.

In contrast to the social constructions of smoking, females have been predominantly portrayed as the major responsible party for family planning such as reproduction and fertility (Gordon, Citation2002). Gender stereotypes and family planning have been explored extensively, especially in one of its feminized aspects—contraception that intersects women’s bodies (sex) with females’ responsibilities (gender). Lowe (Citation2005) underlined the relationship between social narratives of female bodies in the experience of pregnancy and social norms about women’s contraceptive responsibilities. Fennell (Citation2011) found the responsibilities for taking care of reproductive health in heterosexual relationships had disproportionately fallen on women’s shoulders. The feminized contraception and the associated professional counseling visits then leave men out of the picture of family planning (Kimport, Citation2018). Consequently, social expectations of gender roles were found to be a prominent factor in sexual and reproductive health (Varga, Citation2003), which called for gender integration into family planning programs (Garg & Singh, Citation2014).

Based on previous literature regarding the social constructions of lung cancer and family planning in relation to masculinity and femininity, we hypothesize:

H1: There will be gender stereotypes regarding lung cancer screening and family planning, such that lung cancer screening will be viewed as linked to males and family planning, on the other hand, will be viewed as related to females.

2.4. Internalization of gender stereotypes

According to Foucault (Citation1980), power relations in everyday life are embedded in disciplinary institutions like schools, prisons, and hospitals, form where individuals learn to engage in self-surveillance and self-discipline “voluntarily.” Individuals internalize social norms, including gender stereotypes, and act out accordingly. This concept echoes with the social constructionist theory (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1967) that individuals act in certain ways due to their adaptation to the social concepts of femininity and masculinity (W. Courtenay, Citation2000). They are active participants in co-producing gendered roles and perceptions, rather than mere passive victims of socially constructed gendered roles (Courtenay, Citation1998a). In this sense, Saltonstall (Citation1993) claimed that “health actions are social acts” (p. 12), thereby doing health is a form of doing gender.

Research has shown mixed findings regarding how males or females internalize gender stereotypes differently. Some indicated that the traditional beliefs of manhood and masculinity were strong predictors of health behaviors and negative health outcomes, which led males to experience more social pressure and to internalize gender stereotypes more than females did (W. Courtenay, Citation2000; Ng et al., Citation2007). Other researchers (e.g., Pavlova et al., Citation2014) documented a greater impact of gender stereotypes on females. As such, we hypothesize:

H2: Males and females differ significantly in their beliefs in gender stereotypes regarding lung cancer screening and family planning.

2.5. Implications of gender stereotypes on health

Socially constructed gender stereotypes bear multiple implications on individual health. When it comes to disease prevention and health promotion, one outcome of particular interest is information seeking—the action of obtaining information, which includes “information about [one’s] health, health promotion activities, risks to one’s health, and illness” (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2007, p. 1008). As health knowledge has been noted as one of the cornerstones for improving health (e.g., Adams, Citation2010), being motivated to seek relevant health information serves as a key prerequisite for knowledge acquisition and decision-making. Scholars found various predictors of health information seeking, including sex differences (Lebeau et al., Citation2020), social connections (Glanz et al., Citation2015), socioeconomic status (Ishikawa et al., Citation2016), and perceived susceptibility (Ahadzadeh et al., Citation2015). Indeed, a simple “main-effect” prediction is unlikely considering how complex the formation of individual intentions is. The extent to which individuals are motivated to seek information on lung cancer screening and family planning, in this case, will be dictated not only by their beliefs in gender stereotypes but also by the socially constructed expectations of their own gender identities. As such, we predict:

H3: Information-seeking intention varies as a function of gender stereotype and gender identity, such that individuals of stronger gender stereotypes will intend to seek more information on a preventative behavior (i.e., lung cancer screening and family planning), which matches their gender accordingly (e.g., male participants on lung cancer screening, female participants on family planning).

3. Methods

3.1. Implicit association test

IAT was originally developed in psychology for “diagnosing a wide range of socially significant associative structures” (A. Greenwald et al., Citation1998, p. 1464). Measuring automatic cognitive associations, IAT is particularly useful at gauging implicit attitudes that individuals are either unaware of or unwilling to admit (Greenwald & Banaji, Citation1995; Nosek et al., Citation2005). Built on the tenets of theories on the automaticity of human minds (see Nosek et al., Citation2007 for a review), the underlying assumption of IAT is that it is a lot easier to respond to objects in a way that is consistent with our preconceived cognitive schemata. IAT has been found particularly effective in measuring a variety of implicit cognitions, including stereotypes (e.g., Blair et al., Citation2001; Rezaei, Citation2011), prejudices (e.g., Rudman & Glick, Citation2001), and biases (e.g., Green et al., Citation2007).

As self-report responses are prone to the distortion of social desirability—the human tendency of presenting themselves positively (Van de Mortel, Citation2008)—explicitly asking participants their perceptions will likely prime participants and yield artificial answers on sensitive topics like gender stereotypes. One major advantage of IAT is its robustness against faking (Cvencek et al., Citation2010; Steffens, Citation2004). Hence, we utilize IAT for measuring pre-existing gender stereotypes of the two preventative health behaviors—lung cancer screening and family planning.

3.1.1. IAT design and stimuli

The way IAT tests implicit attitudes is through association-sorting tasks, in which participants need to classify stimulus items into targets or categories. The strength of association between targets and categories is measured by the speed of categorizing stimulus items in two conditions that pair up targets and categories in reverse order. Participants were presumably able to sort a stimulus item faster in a compatible condition where for example, lung cancer screening and male are paired up as opposed to when family planning and male appear in pairs in an incompatible condition (A. G. Greenwald et al., Citation2003).

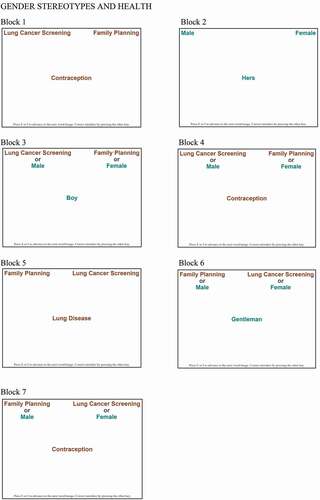

In IAT, each target and category have a set of stimulus items either in text or in images (Lane et al., Citation2007). Text stimuli were chosen in this study to minimize confounding variables. Based on previous literature on creating stimuli items (Nosek et al., Citation2005), seven stimulus words were used for each target (lung cancer screening; family planning) and category (male; female) (see Appendix A for full stimulus words). Participants were instructed to use the “E” and “I” key on a computer keyboard to categorize a given stimulus word into targets or categories as fast as they can (e.g., “E” key for male in the upper-left corner of the computer screen; “I” key for female in the upper-right corner) (see Appendix B). IAT usually consists of seven blocks, including a practice Block 1 (B1: 20 practice trials) to classify words into targets lung cancer screening (by pressing “E” key) and family planning (by pressing “I” key), a practice B2 (20 trials) to categorize words into categories male and female in the same order, followed by a block combining targets and categories (compatible block: lung cancer screening + male; family planning + female) where participants press “E” key for words in lung cancer screening or male and “I” key for words in family planning or female. This combined block is divided into a practice B3 (20 trials) and a critical B4 (40 trials), followed by practice B5 on the same categories but with the sides switched (“E” key for female; “I” key for male) for removing the left/right associations learned in previous blocks (Carpenter et al., Citation2018). Finally, participants repeat a block combining targets and categories reversely (incompatible block: lung cancer screening + female; family planning and male). Similarly, this block is divided into a practice B6 of 20 trials and a critical B7 of 40 trials (Nosek et al., Citation2005) (see Appendix C for details).

3.1.2. IAT scoring

As Carpenter et al. (Citation2018) suggested, data in the two combined blocks (B3, B4, B6, B7) were analyzed to calculate a D score for each participant. The D score indicates in which condition, compatible or incompatible, each participant completes the sorting tasks faster. A positive D score suggests that a participant is faster in the compatible block, and a negative score indicates that one is faster in the incompatible block. A D score of 0 means no difference in the speed between compatible and incompatible blocks (see Back et al., Citation2005; A. G. Greenwald et al., Citation2003; Lane et al., Citation2007). Here, a more positive D score in this study means one possesses a stronger “lung-cancer-screening-for-males-and-family-planning-for-females” gender stereotype. The D scores can be further used for other statistical analyses like regression to examine the relationships between implicit attitudes and other outcome variables.

The entire IAT was programmed into Qualtrics using iatgen R scripts, a free, user-friendly tool for administering IATs in Qualtrics (Carpenter et al., Citation2018). The D scores were also analyzed using iatgen R scripts.

3.2. Participants

After the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at SUNY Albany approved the study, participants were recruited through the Lucid Theorem, which has received increasing recognition as a reliable source for online respondents with quality national samples (e.g., Coppock & McClellan, Citation2019; Wood & Porter, Citation2019). The sample was a quota sample with all participants residing in the U.S. and was managed to approximate the population with regard to age, sex, ethnicity, income, and region of residence based on the U.S. Census data. The final sample included a total number of 262 participants who completed the study. Out of these participants, 49.24%, or 129 were males, and 50.76%, or 133 were females. The average age was 50.10 (SD = 16.44, Range = 67). 23.92%, or 61 participants lived in the Northeastern regions, 20.39%, or 52 in the Midwest, 37.65% or 96 in the South, and 18.04%, or 46 resided in the West.

3.3. Procedure

Participants were invited by Lucid Theorem with a link to participate via a Qualtrics questionnaire voluntarily. Upon indicating consent, they proceeded to do the IAT that examined their beliefs in the gender stereotypes regarding lung cancer screening and family planning. Afterward, they were randomly assigned to indicate how likely they were going to seek information on either lung cancer screening or family planning. It was intentionally designed to ask only a half of the entire participants their information-seeking intentions on one preventative behavior (lung cancer screening or family planning) to avoid revealing the true purpose of this study to them. Participants were then prompted with a few demographic questions, including gender and age. Upon the completion of the study, participants were thanked and compensated for their participation.

3.4. Independent variables

3.4.1. Gender stereotype

Participants’ gender stereotypes toward lung cancer screening and family planning were measured using the IAT. Participants’ D scores represented the degree to which they believed in the stereotypical association between a certain gender and a preventative behavior. A more positive D score indicated a stronger belief congruent with the linkage (male and lung cancer screening, female and family planning) and a more negative score suggested a stronger incongruent perception. Participants’ D scores ranged from −.45 to 1.40, M = .55, SD = .38.

3.4.2. Gender identity

Participant gender was measured by asking “what is your gender?” with three options—“Male, Female, and Other”. 129 participants self-identified as males, and the remaining 133 self-identified as females. None of the 262 participants chose the “Other” category. Therefore, participant gender was dummy coded as 0 = male and 1 = female.

3.5. Dependent variable

3.5.1. Information-seeking intention

Five items adapted from Kahlor et al. (Citation2006) were used to measure the intention to seek information. A random half of the participants were asked to rate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale of 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree” regarding items such as “I plan to seek information about lung cancer screening in the near future” and “I intend to find more information about lung cancer screening in the near future”, and the other random half rated the same five items for family planning (Cronbach’s α = .99, M = 4.24, SD = 1.85 for lung cancer screening, Cronbach’s α = .99, M = 3.20, SD = 2.03 for family planning).

4. Results

4.1. Gender stereotypes

H1 predicted a significant gender stereotype regarding the two behaviors, such that lung cancer screening to be strongly associated with males and family planning with females. A one-sample t-test was conducted to test the null hypothesis that there was no gender stereotype (i.e., MDscore = 0). Such analysis revealed that there was indeed a significant gender stereotype (M = .55, SD = .38). Lung cancer screening was viewed as significantly more related to males, whereas family planning was perceived as largely associated with females, t(261) = 23.11, p < .001. Therefore, H1 was supported.

4.2. Gender difference in gender stereotypes

H2 hypothesized that males and females were different in their beliefs in the gender stereotypes regarding lung cancer screening and family planning. An independent sample t-test on participants’ D scores confirmed that female participants displayed significantly stronger stereotypical beliefs regarding the two behaviors (M = .65, SD = .32) than male participants did (M = .46, SD = .40), t(260) = −4.29, p < .001. Hence, H2 was supported as well.

4.3. Information-Seeking intention

H3 hypothesized that information-seeking intention varied as a function of gender stereotype and participant gender identity. A hierarchical regression was conducted to examine the impact of gender stereotype and participant gender identity on the intention to seek information on lung cancer screening. Zero-order terms of these variables were entered in step 1, and the interaction term between gender stereotype and gender identity was entered in step 2. As gender stereotypes (in D scores) and information-seeking intentions (on the 7-point Likert scale) were measured on different metrics, they were standardized prior to being entered into the model. Such an analysis indicates that overall, the total model accounts for a marginally significant portion of the variance in intention to seek information on lung cancer screening, F (3, 133) = 6.50, p < .10, adjusted R2 = .02. reports the statistics associated with the analysis and reveals that a significant main effect for gender stereotype, such that a stronger gender stereotype toward lung cancer screening significantly decreased the intention to seek information on this topic, β = −.18, p < .05. In contrast, neither the participant gender identity (β = −.03, p = .70) nor the interaction between gender stereotype and gender identity (β = .06, p = .62) had any significant effect on information-seeking intention.

Table 1. Predictors of intention to seek information on lung cancer screening

Another hierarchical regression was conducted to examine the impact of gender stereotype and participant gender identity on their intention to seek information regarding family planning. The zero-order terms of these variables and their interaction terms were entered as with the previous hierarchical regression analysis. Gender stereotype and information-seeking intention regarding family planning were standardized prior to entering into the model. Such an analysis indicates that the total model accounts for a significant portion of the variance in the intention to seek information on family planning, F (3, 133) = 6.50, p < .001, adjusted R2 = .11. reports all statistics associated with the hierarchical regression analysis. A significant main effect of gender stereotype emerged in such an analysis. A stronger gender stereotype toward family planning significantly reduced intention to seek information on this topic, β = −.29, p < .01. In contrast, the main effect for gender identity was not significant, β = −.10, p = .24.

Table 2. Predictors of intention to seek information on family planning

However, the main effects of gender stereotype and gender identity need to be interpreted in light of a significant Gender stereotype X Gender identity that was also obtained with a marginal significance, β = .18, p < .10. To decompose the interaction, a simple slope analysis was conducted for male and female participants. As shown in , participants who self-identified as male and subscribed more to the gender stereotype regarding family planning had significantly lower intention to seek information on family planning, β = −.41, p < .001. For female participants, their intention to seek family-planning-related information stayed the same regardless of the strength of their stereotypical perceptions of family planning, β = −.13, p = .34.

5. Discussion

5.1. General discussion

The findings on gender stereotypes regarding lung cancer screening and family planning confirm the pre-existing social constructions at an individual, cognitive level, such that lung cancer screening is indeed viewed as more related to males (Collins, Citation2005) and family planning is more linked to females (Fennell, Citation2011; Varga, Citation2003). While gender stereotypes run rampant for both men and women, our study reveals that women tend to internalize stereotypes more than men do in the context of these two health behaviors. The significant gender difference suggests that females internalize not only the stereotypes on males (lung cancer screening + males) but also the ones on their own gender (family planning + females) more than men do. This offers empirical support to previous literature that women are at a higher risk of falling prey to stereotypical gender portrayals in health (Pavlova et al., Citation2014).

This study also indicates that a stronger gender stereotype on lung cancer screening decreases individual intention to seek information irrespective of gender identities—the significant main effect of gender stereotype on information-seeking intention regarding lung cancer screening. Understandably, females are less interested in seeking more information on lung cancer screening as they believe more in the stereotype that lung cancer screening is mainly for men. However, more complicated reasoning might be at play for male participants’ counterintuitive and inconsistent results. Research demonstrates health information-seeking behaviors are influenced by perceived susceptibility to specific health issues (Ahadzadeh et al., Citation2015). Hence, when holding a stronger gender stereotype on lung cancer screening, male participants should report greater intentions to seek information on lung cancer screening due to augmented perceived susceptibility to lung cancer. Yet considering how masculinity has been traditionally depicted, participants who self-identified as males are very likely also subscribed to the socially constructed ideal image of men as tough and courageous (W. Courtenay, Citation2000; Mandal, Citation2007). Thus while perceiving themselves as more susceptible to lung cancer, they are still hesitant to proactively seek information on lung cancer screening because the idea of self-protection runs against the social expectations of men and prevents them from properly performing “being a real man.”

Results on the significant interaction of gender stereotype and gender identity on the intention to seek family-planning-related information provide support to our above speculation. While a greater gender stereotype on family planning also significantly decreases individuals’ intention to seek more information on this health preventive behavior, the interaction reveals a much more intricate story. Male participants’ intention to seek information on family planning drops significantly as they believe more in the stereotypical link between family planning and females. Female participants reported similar levels of information-seeking intention on family planning regardless of the degree to which they subscribe to the gender stereotype on family planning. This non-significant intentional variation among female participants could be due to the social expectations imposed on them when it comes to family planning (Fennell, Citation2011; Kimport, Citation2018).

Going back to the social constructionist theory, individuals are not simply influenced by the social norms; they also contribute to the construction and reinforcement of these social norms. As such, it is not surprising to see invariance on female participants’ intention to seek family-planning-related information as they are socially related to planned parenthood. This finding bears problematic implications as previous research found that, ironically, men, tended to be the decision-makers on family size and family planning options like fertility, contraceptive use, and health care utilization for themselves and their sexual partners (e.g., Mosha et al., Citation2013), even though they might not be well-informed or even interested in knowing more about family planning (Courtenay, Citation1998a, Citation1998b; Lebeau et al., Citation2020).

5.2. Theoretical implications

This study adds to the existing literature by exploring the health implications of gender stereotypes intersecting with gender identity. While many studies have discussed inequality caused by gender stereotypes (e.g., Fennell, Citation2011; McCool et al., Citation2004), our findings offer a more nuanced examination as to the complicated impact of gender stereotypes on individual health. The interaction between gender stereotypes and gender identity suggests that we need to take a multifaceted approach to understand how gender plays out in health.

This study also offers a methodological contribution: the application of IAT to measure gender stereotypes rather than using self-reported data. While IATs have been utilized to explore gender stereotypes and prejudices (Blair et al., Citation2001; Rezaei, Citation2011; Rudman & Glick, Citation2001), it has not, to our knowledge, been applied to measuring gender stereotypes in relation to preventative health behaviors. As self-report responses have been criticized for their artificiality (Van de Mortel, Citation2008), our findings offer an extra level of validity and ecological realism as IATs have been repeatedly found sound for measuring implicit attitudes like stereotypes.

5.3. Practical implications

As gender (and stereotypes) being socially constructed, its fluid nature and individuals’ roles in constructing (or reinforcing) the gender stereotypes offer a promising outlook to reconstruct existing gender stereotypes to mitigate health inequality purposefully. More strategic communications can be done at the individual level to promote preventive health behaviors. By understanding the association between gender stereotypes and specific preventative health behaviors, this study offers useful insights into health message designs and health campaign management for raising public awareness of preventative behaviors. Building on the findings, health message designing should consider the possible gender stereotypes on targeted health behaviors. For campaigns aiming at increasing lung cancer screening rates, the framing of lung cancer should not simply focus on how it can be caused by “masculine” behaviors like smoking. Instead, one can bring in other risk factors like environmental tobacco smoking and domestic housework (Samet et al., Citation2009) to female non-smokers who are equally susceptible, if not more, to lung cancer. The attempts to promote family planning can target more male audiences and encourage their participation in their own and their partners’ health.

For health providers and professionals, the findings can serve as reminders that gender stereotypes could impact the decision-making of their patients. They can mindfully educate patients with “genderless” information to avoid reinforcing pre-existing gender stereotypes on certain health behaviors that are beneficial to both males and females. They can order examinations and offer professional advice to those who are not aware of the potential health threats, such as recommending lung cancer screening for more female patients when needed. Policymakers and government officials can promote these preventative health behaviors for everyone with health campaigns. For instance, as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose CT scans generally for individuals who are smokers, with a smoking history, or beyond age 50 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Citation2021), they can also provide policy prescriptions aiming at people constantly exposed to environmental risk factors like second-hand smoke, cooking oil fume, and air pollutants. The findings also call for media collaborations to reconstruct the portrayals of certain health behaviors. As an important source for individuals to perceive and understand the surrounding world, the media could actively avoid depicting health behaviors in ways that further reinforces existing gender stereotypes. They should further strategically help reconstruct the social expectations of different gender identities in health by diversifying story framing and storytelling of preventative behaviors.

5.4. Limitations and future directions

Like all research, this study is not without limitations. First, while our study confirms gender stereotypes on lung cancer screening and family planning, individuals could hold these stereotypes differently. For instance, family planning involves contraceptives, pregnancy, infertility, STD, and more; individuals might be stereotypical about STD but not about its other aspects. Qualitative studies could be particularly useful to further understand gendered perceptions on certain aspects of a preventative health behavior.

Second, as gender has been continuously nuanced along the spectrum as a fluid concept, this study starts off by exploring gender through the binary female/femininity vs. male/masculinity. This approach, though providing a promising start in an understudied area, could mask the full intricacy of gender in relation to health. Future research could expand our research by taking a more nuanced gender perspective (e.g., LGBTQ) and explore how individuals of more gender identities perceive health behaviors. Finally, although not all preventive behaviors are equally gendered, understanding the role of gender and how we socially construct (reconstruct) gender stereotypes is an essential step on our path to better health.

6. Conclusion

The findings of this study confirmed the gender stereotypes regarding family planning and lung cancer screening found by the existing literature and further revealed the relationship between individuals’ gender identity and their intention to seek certain preventative health information. While we found that female participants internalized the gender stereotypical perceptions of illnesses more than male participants did, both males and females subscribing more to the gendered perceptions of the illnesses reported significantly less intention to seek relevant information, especially on the illnesses they did not consider to be associated with themselves. The internalization and identification of socially constructed gender identities, in this sense, could influence one’s preventive health behaviors. As such, this study suggests that health providers, health policymakers, health campaign designers, and the media should all play critical roles in delivering more genderless health information to the public and further reconstruct the gendered social expectations in health contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chia-Heng Chang

Chia-Heng Chang is a Ph.D. candidate in Communication at the University at Albany-SUNY. Her research focuses on gender-relevant issues in health and political communication. Fan Yang (Ph.D. Pennsylvania State University) is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University at Albany-SUNY. Her research focuses on information processing and decision-making particularly in the context of new media through classic and computational quantitative research methods.

Fan Yang

Chia-Heng Chang is a Ph.D. candidate in Communication at the University at Albany-SUNY. Her research focuses on gender-relevant issues in health and political communication. Fan Yang (Ph.D. Pennsylvania State University) is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University at Albany-SUNY. Her research focuses on information processing and decision-making particularly in the context of new media through classic and computational quantitative research methods.

References

- Adams, R. (2010). Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 3, 61–18. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S7500

- Ahadzadeh, A. S., Sharif, S. P., Ong, F. S., & Khong, K. W. (2015). Integrating health belief model and technology acceptance model: An investigation of health-related internet use. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3564

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall.

- Andermann, L. (2010). Culture and the social construction of gender: Mapping the intersection with mental health. International Review of Psychiatry: Gender and Mental Health, 22(5), 501–512. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2010.506184

- Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2005). Measuring task-switching ability in the implicit association test. Experimental Psychology, 52(3), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169.52.3.167

- Bem, S. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88(4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge Anchor books ed. Doubleday.

- Blair, I., Ma, J., & Lenton, A. (2001). Imagining stereotypes away: The moderation of automatic stereotypes through mental imagery. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 828–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.828

- Butler, J. (1988). Performative acts and gender constitution an essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

- Canning, D., & Schultz, T. (2012). The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning. The Lancet, 380(9837), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60827-7

- Carpenter, K., Bell, R., Yunus, J., Amon, A., & Berchowitz, L. (2018). Phosphorylation-Mediated clearance of amyloid-like assemblies in meiosis. Developmental Cell, 45(3), 392–405.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.001

- Casad, B., & Wexler, B. (2017). Gender stereotypes. In K. Nadal (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of psychology and gender (pp. 755–758). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020a). Healthy Living. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020b). Smoking & Tobacco Use. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/cessation/quitting/index.htm

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020c). Providing Quality Family Planning Services. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/contraception/qfp.htm

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Who Should Be Screened for Lung Cancer? CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/screening.htm

- Clément-Duchêne, C., & Wakelee, H. (2010). Lung Cancer Incidence in Never Smokers. The European Journal of Clinical & Medical Oncology, 2(2), 49–57. http://search.proquest.com/docview/757064378/

- Collins, J. (2005). Letter from the Editor: Lung cancer and gender bias. Seminars in Roentgenology, 40(2), 77–78. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ro.2005.01.015

- Copenhaver, M., Lash, S., & Eisler, R. (2000). Masculine gender-role stress, anger, and male intimate abusiveness: Implications for men’s relationships. Sex Roles, 42(5/6), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007050305387

- Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174

- Courtenay, W. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1

- Courtenay, W. H. (1998a). Better to die than cry? A longitudinal and constructionist study of masculinity and the health risk behavior of young American men [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of California at Berkeley. Dissertation abstracts International, 59(08A), 232. http://search.proquest.com/docview/304432802/

- Courtenay, W. H. (1998b). College men’s health: An overview and a call to action. Journal of American College Health, 46(6), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448489809596004

- Cui, Y., Zhu, Q., Lou, C., Gao, E., Cheng, Y., Zabin, L., & Emerson, M. (2018). Gender differences in cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking among adolescents and young adults in Hanoi, Shanghai, and Taipei. Journal of International Medical Research, 46(12), 5257–5268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060518807292

- Cvencek, D., Greenwald, A. G., Brown, A. S., Gray, N. S., & Snowden, R. J. (2010). Faking of the Implicit Association Test is statistically detectable and partly correctable. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2010.519236

- Fennell, J. (2011). Men bring condoms, women take pills: Men’s and women’s roles in contraceptive decision making. Gender & Society, 25(4), 496–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243211416113

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fleming, P. J., & Agnew-Brune, C. (2015). Current trends in the study of gender norms and health behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.05.001

- Foucault, M. (1980). Discipline and punish. (A. Sheridan, trans.). Vintage Books.

- Gallaway, M. S., Henley, J., Steele, B., Monin, B., Thomas, C. C., Jamal, A., Trivers, K. F., Singh, S. D., & Stewart, S. L. (2018). Surveillance for cancers associated with tobacco use — United States, 2010–2014. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 67(12), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6712a1

- Garg, S., & Singh, R. (2014). Need for integration of gender equity in family planning services. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 140(4), 147–151. http://search.proquest.com/docview/2258265702/

- Glanz, K., Rimer, B., & Viswanath, K. (2015). Health behavior theory, research, and practice (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Gordon, L. (2002). The moral property of women: A history of birth control politics in America (3rd ed.). University of Illinois Press.

- Green, A., Carney, D., Pallin, D., Ngo, L., Raymond, K., Iezzoni, L., & Banaji, M. (2007). Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(9), 1231–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5

- Greenwald, A., & Banaji, M. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.1.4

- Greenwald, A., Mcghee, D., & Schwartz, J. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

- Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197

- Heise, L., Greene, M. E., Opper, N., Stavropoulou, M., Harper, C., Nascimento, M., Henry, S., Greene, M. E., Hawkes, S., Heise, L., Henry, S., Heymann, J., Klugman, J., Levine, R., Raj, A., Rao Gupta, G., & Zewdie, D. (2019). Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: Framing the challenges to health. The Lancet, 393(10189), 2440–2454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X

- Ishikawa, Y., Kondo, N., Kawachi, I., & Viswanath, K. (2016). Are socioeconomic disparities in health behavior mediated by differential media use? Test of the communication inequality theory. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(11), 1803–1807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.018

- Jia, P., Zhang, C., Yu, J., Xu, C., Tang, L., & Sun, X. (2017). The risk of lung cancer among cooking adults: A meta-analysis of 23 observational studies. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 144(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2547-7

- Kahlor, L., Dunwoody, S., Griffin, R. J., & Neuwirth, K. (2006). Seeking and processing information about impersonal risk. Science Communication, 28(2), 163–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547006293916

- Kerr-Corrêa, F., Igami, T., Hiroce, V., & Tucci, A. (2007). Patterns of alcohol use between genders: A cross-cultural evaluation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 102(1–3), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.031

- Kimport, K. (2018). Talking about male body-based contraceptives: The counseling visit and the feminization of contraception. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 201, 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.040

- Krieger, N. (2003). Genders, sexes, and health: What are the connections–and why does it matter? International Journal of Epidemiology, 32(4), 652–657. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg156

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2007). Health information-seeking behavior. Qualitative Health Research, 17(8), 1006–1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307305199

- Lane, K. A., Banaji, M. R., Nosek, B. A., & Greenwald, A. G. (2007). Understanding and using the implicit association test: IV: What we know (So far) about the method. In B. Wittenbrink & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Implicit measures of attitudes (pp. 59–102). The Guilford Press.

- Lebeau, K., Carr, C., & Hart, M. (2020). Examination of gender stereotypes and norms in health-related content posted to snapchat discover channels: Qualitative content analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3), e15330. https://doi.org/10.2196/15330

- Littlejohn, S. W., & Foss, K. A. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of communication theory. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412959384.n151

- Lowe, P. (2005). Contraception and heterosex: An intimate relationship. Sexualities, 8(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460705049575

- Mahalik, J. R., Burns, S. M., & Syzdek, M. (2007). Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men’s health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 64(11), 2201–2209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.035

- Mandal, E. (2007). Gender and taking risks hazardous to health and life. Kobieta I Biznes, (1–4), 27–30. https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.albany.edu/docview/230450062?pq-origsite=primo

- McCool, J., Cameron, L., & Petrie, K. (2004). Stereotyping the smoker: Adolescents’ appraisals of smoking in film. Tobacco Control, 13(3), 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2003.006791

- McVee, M., Dunsmore, K., & Gavelek, J. (2005). Schema theory revisited. Review of Educational Research, 75(4), 531–566. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3516106

- Mosha, I., Ruben, R., & Kakoko, D. (2013). Family planning decisions, perceptions and gender dynamics among couples in Mwanza, Tanzania: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 523. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-523

- Ng, N., Weinehall, L., & Öhman, A. (2007). ‘If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man’—Indonesian teenage boys’ views about smoking. Health Education Research, 22(6), 794–804. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl104

- Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2005). Understanding and using the implicit association test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(2), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271418

- Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). The implicit association test at age 7: A methodological and conceptual review. In J. A. Bargh (Ed.), Frontiers of social psychology. Social psychology and the unconscious: The automaticity of higher mental processes (pp. 265–292). Psychology Press.

- Pavlova, M., Weber, S., Simoes, E., Sokolov, A., & Avenanti, A. (2014). Gender stereotype susceptibility. PLoS ONE, 9(12), e114802. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114802

- Payne, S. (2001). “Smoke like a man, die like a man”?: A review of the relationship between gender, sex and lung cancer. Social Science & Medicine, 53(8), 1067–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00402-0

- Pederson, E., & Vogel, D. (2007). Male gender role conflict and willingness to seek counseling: Testing a mediation model on college-aged men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(4), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.4.373

- Rezaei, A. R. (2011). Validity and reliability of the IAT: Measuring gender and ethnic stereotypes. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(5), 1937–1941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.04.018

- Rubin, J. B., Lagas, J. S., Broestl, L., Sponagel, J., Rockwell, N., Rhee, G., Rosen, S. F., Chen, S., Klein, R. S., Imoukhuede, P., & Luo, J. (2020). Sex differences in cancer mechanisms. Biology of Sex Differences, 11(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00291-x

- Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00239

- Saltonstall, R. (1993). Healthy bodies, social bodies: Men’s and women’s concepts and practices of health in everyday life. Social Science & Medicine, 36(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90300-S

- Samet, J., Avila-Tang, E., Boffetta, P., Hannan, L., Olivo-Marston, S., Thun, M., … Samet, J. (2009). Lung cancer in never smokers: Clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors. Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 15(18), 5626–5645. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0376

- Steffens, M. C. (2004). Is the implicit association test immune to faking? Exp. Psychol, 51(3), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169.51.3.165

- Tredaniel, J., Boffetta, P., Saracci, R., & Hirsch, A. (1997). Non-smoker lung cancer deaths attributable to exposure to spouses environmental tobacco smoke. International Journal of Epidemiology, 26(5), 939–944. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/26.5.939

- van de Mortel, T. F. (2008). Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-report research. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(4), 40–48. http://www.ajan.com.au/ajan_25.4.html

- Varga, C. (2003). How gender roles influence sexual and reproductive health among South African adolescents. Studies in Family Planning, 34(3), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00160.x

- Vogel, D., Wade, N., & Hackler, A. (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.1.40

- WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs, Knowledge for Health Project. (2018). Family planning: A global handbook for providers. CCP and WHO. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/fp-global-handbook/en/

- Wood, T., & Porter, E. (2019). The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. Political Behavior, 41(1), 135–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-9443-y

- Zambon, M., Regis, S., & Lamb, C. (2017). Comparison of lung cancer screening practices by gender in a large single-center lung screening program. Chest, 152(4), A623–A623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.08.656

Appendix A

Word Lists for Implicit Association Tests

Male words. he, man, men, boy, him, his, gentleman

Female words. women, girl, woman, hers, her, she, lady

lung cancer screening words. quitting smoking, smoking clinic, lung health, cigar, cigarette, pipes, lung disease

family planning words. baby, pregnancy, contraception, birth, birth control, sex, labor

Appendix B

Instruction Page of the IAT

Appendix C

Sequence of Trial Blocks in Gendered Preventative Health Behaviors