Abstract

The influence of rural tourism on the socio-economic well-being of indigenous people is often ignored in scholarly literature. To address this gap in the literature, a qualitative case study research design was used to gain insights into how tourism strategies had over the years influenced the economic wellbeing of indigenous people living within the catchment area of the Kakum National Park (KNP) in the central region of Ghana. The participants of the study comprised residents of “Dwaso” and “Ahafo” within the central region of Ghana. The study’s findings revealed that the establishment of tourist site has been a mixed blessing. This is not surprising because it has made the names of the communities popular across the world. However, the negative side of the tourist site far outweighs the dividends because it has impoverished the people in terms of depriving them of their source of livelihood. To worsen their plight, natives are subjected to various forms of harassment as their source of eking out a living and virtually rendering them paupers, which used not to be so before the advent of the tourist site.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Recognizing the resultant consequences of existing tourist attractions from the perspective of rural fringe communities is an essential component of sustainable tourism development, about which little is known. Tourism in Ghana is making a significant contribution to the country’s development but little is known about how the Kakum National Park is contributing to livelihood improvement and wellbeing of the indigenous people through the earlier and creation of new livelihood activities within the catchment area. This study interviewed participants who hail from the communities surrounding the tourist site on their opinions regarding how beneficial the site is to them, especially through the creation of livelihood activities. The result revealed that the site has been mixed blessings because it has positively projected the name of their community worldwide, but the only snag is that poverty resulting from loss of livelihood activities and displacements, including maltreatment has become their lot.

1. Introduction

Political and philosophical debates have emerged over the years regarding how the aims of conservation projects can be tailored to conform with the demands and desires of people who are likely to be directly affected (Borchers 2004 as cited in Agyeman, Citation2005). Governments from different countries across the globe in 1992 converge at the Earth Summit. The essence of the meeting was to deliberate on how tourist sites can be managed prudently to become sustainable and improve conservation to engender sustainable development. Unlike previous practices that perceived local communities as a threat to nature, the 1992 Earth Summit, African Union Agenda 2063, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 takes into account not only conservation but sustainable use and directing of benefits to local people from conservation projects including a high standard of living, quality of life and wellbeing of local people (African Union Commission, Citation2015; Bergman et al., Citation2018; Colglazier, Citation2015; Gowreesunkar, Citation2019). In line with this, conservation agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) were entered into by member countries (Paterson, Citation2011).

The convention appeared to be a blessing in disguise because several developing counties have seen an increase in the number of national parks and its influence on local livelihoods in the wake of the signing of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) agreement by governments across the globe and the significance therein has been remarkable (Atisa, Citation2014; De Oliveira et al., Citation2011). African countries like South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Ghana are among the few countries to have witnessed such an impact regarding the creation of national parks. Yet, there still exist problems for the legal regime regulating the creation of the parks and tourism activities therein. Even though there are benefits that accrue to the beneficiary communities regarding the establishments of national parks and tourism, the sacrifices that they have to bear are enormous and painful (Amoah & Wiafe, Citation2012).

An effective way of developing tourism in local communities to improve livelihoods is said to be through nature-based tourism and the distribution of benefits tied to it in a targeted manner (Mayaka et al., Citation2018). However, in a developing country such as Ghana, these reserves and national parks are on the same land those local communities depend on for their livelihoods. Even though the establishment of nature reserves and national parks has been a priority of policymakers in the field of tourism and conservation since the 19th century (Agyeman, Citation2005), the creation of these parks and reserves restricts livelihood activities of local communities on their land considering their activities as unsustainable (Adu-Ampong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Melubo & Lovelock, Citation2019). Livelihood activities of local communities, such as hunting and collecting Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) as well as building materials are considered activities that tend to degrade the natural environment, which in turn leads to the extinction of biodiversity (Agyeman, Citation2005).

Tourism is reliant on local communities and the natural and man-made environment. This explains why communities in most developing countries that support tourism have their development channeled through tourism development. Tourism is currently viewed by many practitioners as an instrument for preserving and conserving the natural and monumental resources of a country. Tourism is tied to development (Adu-Ampong & Kimbu, Citation2019; Asiedu, Citation2002); and has many times been used in development studies as a way of addressing the issue of inequalities among communities through equal distribution of benefits. There are identified means through which benefits from tourism projects could be channeled to local communities to address issues of inequality and to enhance the long-term viability of tourism projects. As a result, tourism practitioners use these means to ensure local communities living close to tourist attractions centers benefit considerably from tourism in place of lost livelihood activities (Akyeampong & Asiedu Citation2008).

Sharing of revenues from nature-based tourism is among the strategies widely accepted and used by international, national, local, and private tourism organizations including conservationists at all levels to address issues of inequalities and loss of livelihoods among communities (Melubo & Lovelock, Citation2019). This claim validates campaigns for conservation alongside issues of poverty and restricted livelihood opportunities in less developed countries (Ahebwa et al., Citation2011). In less developed countries like Ghana, this strategy is used to channel benefits to local communities for development and livelihood enhancement. How these benefits are distributed and how they impact the livelihoods of individual households is the crux of this study. Tourism is linked with local involvement and the livelihood of local communities. It is believed that the benefits from the Park which will be shared among communities are likely to reduce poverty (Novelli, Citation2015) and influence the lives of the local people in the various fringe communities. Direct and indirect tourism livelihood strategies in the communities are as well vital for enhancing the livelihoods of the local people (Njana et al., Citation2013; Rakodi, Citation2014).

The question that arises is the extent to which Communities living around the Kakum National Park (KNP) have benefits from the establishment of the park and the extent to which it has improved the lives of the people, and this is the crux of the study. Even though anecdotal evidence suggests that the part to some has been mixed-blessings, research evidence is needed to confirm this claim and this is the crux of the current study. In essence, the study seeks to address the following research objectives;

Assess livelihoods strategies available in the Conservation Area;

Determine the influence of livelihood strategies on households in the Conservation Area.

The following research questions guided the study:

What livelihood strategies are available to people in that locality?

How have livelihood strategies influenced the lives of individual households?

1.1. Research context

Tourism in Ghana has been identified with exceptional performance and contribution to the country. Statistics have indicated that tourism is the fastest-growing industry in the Ghanaian economy (Adu-Ampong, Citation2017; Asiedu, Citation2002). Tourism contributes greatly in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and both direct and indirect employment (Adu-Ampong, Citation2018; MBOKA, Citation2008). Ghana has always strived on strategies to increase both international and domestic tourist arrivals and to make the tourism industry the most important economic sector in Ghana (Cobbinah & Darkwah, Citation2016).

Government policies were instigated to make the growth of the Ghana tourism industry possible. Tourism in the mid-1980s was recognized and given precedence in the investment code of Ghana (PNDC Law 116) as one among the five sectors permitting development as well as investments. The prospective nature of tourism as a long-term national development plan resulted in the formulation of national tourism development plans that that focused on the notion of sustainability in Ghana. Among these plans was the 15-year National Development Tourism Plan (NDTP) 1996–2010, which was followed by the Tourism Sector Medium Term Development Plan (TSMTDP) 2010–2013 and currently the Ghana National Tourism Development Plan (GNTDP) 2013–2027 (Adu-Ampong, Citation2019; E. Adu-Ampong, Citation2018; Teye, Citation2008). These plans propose equal benefit distribution and development among residents of the country and specifically local people of rural communities living close to attractions. In this case, the plan supports the development of rural tourism, which considers issues of rural development important. This is to make sure that resources are utilized sustainably with tourism benefits equitably distributed throughout the country (Akyeampong & Asiedu, Citation2008; Asiedu, Citation2002).

Furthermore, the continuous formulation of policies for the Ghanaian tourism industry establishes the fact that successive governments in addition to the economic benefits of tourism have plans to develop tourism and use it effectively to achieve other socio-economic needs such as regional development as well as poverty reduction in Ghana (Akyeampong, Citation2011). Tourism in this sense is anticipated to be one most important sources to create reasonable employment for the residence of Ghana. Currently, one main aim of tourism about Ghana National Development Planning Commission (Citation2013) is to ensure the generation of more opportunities for local participation and tourism benefit acquisition by local entrepreneurs in terms of employment, training, and awareness including accessibility to better infrastructure.

Ghana is blessed with numerous rural tourism resources and for that reason, a strategic rural tourism plan has been formulated by the Ghana Wildlife Department which is in charge of managing all protected areas and ensuring that these resources benefit residents living in surrounding communities. The main aim of the plan is to increase visitor arrivals and revenues yielded from protected areas. Districts with rural tourism resources such as the Twifo-Hemang, Lower Denkyira, Yilo Krobo, Mpohor-Wassaw East, etc. are currently implementing or formulating rural tourism development plans to enhance and manage their rural tourism resources.

Within the West African region, Ghana seems to possess much improved opportunities for establishing diverse game reserves. Some rural tourism resource in Ghana has been selected and classified by the Wildlife Department. Among the classifications are tropical rainforest, savanna woodland, coastal wetlands, outlier forests, sub-montane forests, wetlands, ancient grooves, and other cultural links to conservation, waterfalls, bird watching, monkey and butterfly sanctuaries (Asiedu, Citation2002). However, the main rural tourism facilities that are legally protected by the Wildlife Department of Ghana are the Kakum, Mole, Bui and Bia National Parks, Shaihills, Kogyae and Bobiri reserves, Paga and Agyambra crocodile ponds, Tafi Atome and Buabeng Fiema monkey sanctuaries, Lake Bosomtwe and the Volta River estuary including some other wildlife sanctuaries and wetlands. Apart from these are other unprotected areas such as the Digya and Kyabobo range national parks, Kalakpa and Gbele resource reserves that are important resources for rural tourism development

2. Literature review

2.1. Concept of sustainable rural livelihoods

The issue of development and poverty reduction in rural parts of the world has become important for development organizations, non-governmental and governmental organizations across the world. And currently, prominence has been given to the sustainability of rural livelihoods also termed as sustainable livelihoods. Livelihood is argued to be sustainable when it can develop present and future capabilities and handle stress and shock without damaging the natural resources upon which local people depend (Ashley & Hussein, Citation2000). This could mean food, health, family ties, income, properties, social relations, and diversities as well as occupations of people. It could also be used to explain the diverse levels of resources that provide physical as well as social wellbeing and quality of life of individuals and groups living in a particular location (Scoones, Citation2009, p. 2). Significant values to livelihoods are most excellent systems and practices that are people-centered and focus on poverty reduction and rural development (IDS, Citation2011; McNamara, Citation2008).

Rural tourism projects existed to support conservation together with the development needs of local communities. According to Kumar (Citation2005), these projects aim to encourage the survival of local people with nature through participation and enhanced livelihood opportunities. However, Bediako (Citation2000) identified limited participation of local people in the management of parks has brought about leakage of economic benefits meant for local communities. In many cases studies done in rural communities for instance, have exhibited issues of destruction of nature and poverty, lack of livelihood opportunities, and unequal contribution to livelihood conditions (Mbaiwa & Stronza, Citation2010; Nkhata & Breen, Citation2010). Also, literature available on rural tourism indicates that most projects have contributed to human and financial capital wastage, with little importance given to households (Akyeampong, Citation2011; Mensah et al., Citation2013).

Few studies have used the SLF in analysing the influence of the KNP on local livelihood conditions though some others by Sey (Citation2011) used the SLF focusing on poverty reduction and technology use in Ghana; Marchetta (Citation2011) adopted the SLF with emphasis on strategies to cope with the changing economic, institutional and environmental conditions in the Northern region; and Mensah et al. (Citation2013) used the SLF focusing on residents perception of impacts of the Amansuri in the western region of Ghana.

2.2. Theoretical framework

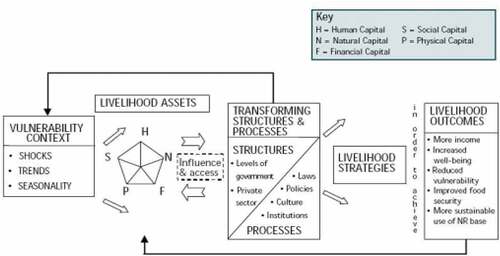

The study was framed by the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) (DFID, Citation2007) which highlights principles that highlight mechanisms for improving the livelihoods of venerable groups in catchment areas of tourism projects. Improving the livelihoods of vulnerable groups is largely dependent on their asses to livelihood resources and the use of effective livelihood strategies positive/negative and direct/indirect for the production of different levels of livelihood outcomes.

The Sustainable Livelihood Approach serves as a tool that aids in exploring people’s livelihoods whereas it envisages the main features of influence on these livelihoods (Rakodi, Citation2014). The approach tends to investigate livelihood impacts in the viewpoint of local people and therefore adopts the qualitative and participatory techniques in enquiring (Van Rijn et al., Citation2012). In this study, the approach allows for evaluating the various influence on livelihood strategies and resulting outcomes on individual households. The various influences identified strategies also envisage the type of influences and outcome rural tourism projects have on the lives of rural communities hence the sustainability of the project.

In effect, upon powers that be in tourist sites such as the Kakum National Park, the sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) offers the best stands to look at the livelihoods of local communities and to answer questions of what impacts. The livelihoods of households are largely dependent on the utilization of assets in their livelihood strategies to improve their lot. However, the use of assets by households is also shaped by individual preferences together with external influences such as policies, institutions, and processes. But these activities can only yield the desired outcome if the product contributes to improvements in conditions of households in the beneficial communities. It is therefore essential to evaluate the impact of rural tourism projects considering the diverse effects they have on local communities (Gubbi et al., Citation2008; Huluka & Wondimagegnhu, Citation2019).

The sustainable livelihood theoretical framework comprises five main components: the vulnerability context, livelihood assets, structures and processes affecting livelihood strategies, and associated livelihood outcomes (E. J. Mensah, Citation2011; Mensah et al., Citation2013; Pandey et al., Citation2017). depicts the elements of the framework.

Figure 1. The sustainable livelihoods framework.Source: DFID (Citation2007)

The vulnerability context is considered the first point in the livelihoods analysis and borders the external environments in which local people live and operate. The context articulates that the livelihoods of local people and the accessibility of assets by local people are influence by natural, demographic and economic situations with trends, shocks, and seasonality being liable for the increase in vulnerability. This can be positive and/or negative, therefore influencing communities and households’ decisions on strategies to implement for their livelihood conditions.

Assets represent the strength of local people. These are assets that local people depend on to make livelihood activities. They are the fundamental livelihood foundation and these establish local people’s capability to break out of poverty. They comprise human, financial, social, physical, and natural assets (DFID, Citation2007).

Human assets are the skills, knowledge, and the capability of individuals to work as well as the health of individuals that facilitate in carrying out their livelihoods strategies to achieve their livelihood outcomes.

A financial asset is the economic resources that individuals obtain to achieve their livelihoods preferences. These may include savings in the form of cash and microcredit that can be obtained from both formal and informal basis. Others may as well include inflows such as gifts, remittances, etc.

A social asset is various social resources that local people gain in the quest for their livelihoods. These consist of trust, social norms, networks, and membership of groups that usually lie behind profit-making ventures/activities.

Physical asset is the infrastructure and producer goods that are required by communities and individuals to sustain their livelihoods. They include roads, safe shelter, adequate water supply, and sanitation as well as clean and affordable energy and equipment used to effectively achieve livelihoods objectives.

Natural assets comprise land, water, forests, marine resources, air quality, erosion protection as well as biodiversity. This asset is essential to individuals whose livelihoods partly or fully depend on resource-based activities such as farming, collection of non-timber resources, and fishing (Kollmair & Juli, Citation2002).

Livelihood structures and processes include public, private and non-governmental institutions and policies; also political, economic, social, legal and cultural mechanism that controls assess to livelihood assets (Bannett, et al., Citation1999; Duncombe, Citation2006).

Livelihood strategies include farming, hunting, mining, trading, and decisions and activities used to attain needed livelihood outcomes (Ashley & Hussein, Citation2000; DFID, Citation2007).

Livelihood outcomes are the component that indicates improved and better wellbeing of local people. Out of the implementation of the livelihood strategies results from the livelihood outcome and improved wellbeing. Livelihood outcomes include increase incomes, reduced vulnerabilities, food security, and sustainable use of natural resources resulting from livelihood strategies.

Focusing on the livelihood strategies and outcomes, this study considers how the park has impacted on livelihoods of local households through direct and indirect tourism strategies.

2.3. Methodology and study area

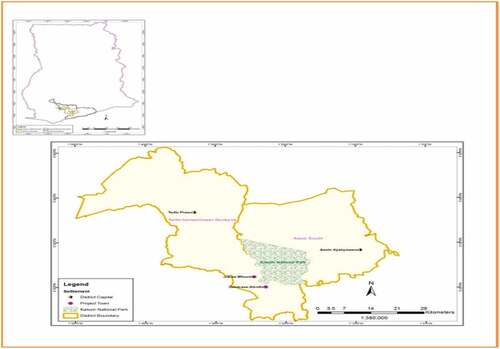

The Kakum National Park is located in the Twifo-Hemang-Lower Denkyira District in the central region of Ghana. It is one of the remaining nature conservation areas in Ghana that has existed as a forest reserve since 1934. The area was turned into a national park in 1992 but on 5 March 1992, it was formally declared as a national park (Amoah & Wiafe, Citation2012; Caesar, Citation2010). The headquarters of this park is in Abrafo-Odumase; one of the communities that surround the park. The vegetation of the park is a tropical moist semi-deciduous forest of about 347 square meters. The park lies between the latitude 05° 20´ and 05° 40´ with longitudes 1° 18´ and 1° 26´W and approximately 30 km from Cape Coast the central regional capital. The park is surrounded by about 60 fringe communities. These communities include villages such as Abrafo-Odumase, Mfuom, Ankaako, and Antwikwaa as well as other small settlements like Gyaware, Mesomagor, and Anomakwaa among others. Kakum National Park and two surrounding villages (Abrafo-Odumase and Mfuom) were selected for the study for the reason of certain successes realized by the park. Also, Abrafo-Odumase is the headquarters and the entrance/gate to the Kakum National Park (KNP) while Mfuom is the next village and about 6.1 km from Abrafo-Odumase. shows the location of KNP together with Abrafo-Odumase and Mfuom

To explore the various influences of both direct and indirect tourism strategies resulting from KNP on the livelihood conditions of individual households, a qualitative approach of data collection and analysis was used for the study. This was to allow local communities to make meanings about available strategies and associated influences based on their experiences (Boeije, Citation2010, p. 11; Ospina & Wagner, Citation2004). A significant principle regarding the use of qualitative study is to gather unexpected data through exploring the minds of individuals and groups to subjective and differing meanings based on experiences. Also, this approach encourages probing deep into complex issues in communities under study and helps appreciate the motives of the individuals involved (James, Citation2007). Two out of the about 60 fringe communities that surround the park and make livelihoods out of forest resources were selected (Abrafo-Odumase and Mfuom).

However, for the purpose of anonymity and confidentiality of the communities and participants of the study, pseudonyms “Dwaso” and “Ahafo” were captured in the analysis to represent the two communities.

The data collection was completed within 7 weeks. And 26 households were purposely selected based on households who were either participants or non-participant of tourism strategies in the communities. Both males and females were selected to participate in the study without particular attention to age and level of gender inclusion/participation. This is because households in these communities were not dependent on age and gender as people with ages less than 20 years in the communities were already married and living with their families and others as single parents. For a successful data collection, contacts were first made through phone calls and e-mails to some lecturers, experts, and others who have insights into the phenomenon under investigation, and permission was asked from opinion leaders in the communities before data collection began (Ruth-mcswain, Citation2011). In-depth face-to-face interviews were conducted and participants were given the free will to decide if they preferred to participate in the study or not. Twenty-six households in total were interviewed from the two selected fringe communities around the KNP. The interviews covered the objectives and allowed for the viewpoints of participants to shape what was to be adhered to (Joffe & Yardley, Citation2004).

Data analysis is significant because it makes it possible in identifying themes tied to the study (Boeije, Citation2010, p. 76). Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data. The recorded interviews were transcribed and coded into categories. The themes were drawn from words that repeatedly occurred in the responses (data) of households interviewed. Thematic analysis is effective for qualitative data because themes and their corresponding sub-themes can be unearthed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Ryan & Bernard, Citation2003). This is significant because the data was coded into categories and which in turn, made it possible for the themes to be identified (Boeije, Citation2010, p. 75). The supervisor listened to the audio recordings and compared them with the transcriptions that were done.

2.4. Credibility

In this study, the four benchmarks for guaranteeing credibility, as outlined by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), include the use of different data sources (triangulation), debriefing, member checking and thick description.

2.5. Findings and analysis

The pseudonyms of the participants of the study have been captured in the analysis.

The following excerpts highlight livelihood strategies that two communities (Dwaso and Ahafo) employed to eke out a living since the establishment of the tourist site since its establishment. The following excerpts capture the perceptions of the two communities regarding livelihood strategies that were in existence before tourism and are currently being practiced by the participants of the study.

2.6. Existing livelihood strategies

There are not many strategies for us to participate since the establishment of the park; we are struggling in taking care of our families. This is bad because we were given the assurance that, the existence of the park would add many more strategies to the existing ones but now look, we have lost even what we use to have.

Even petty trading has been what our women do long before the park came to existence but there has been nothing new about it even with the park just close to us. For now, we cannot point to anything new or even improvement in old strategies even though the park is receiving a lot of tourists.

The Park is a hindrance to meeting our livelihood needs. The majority of our youth have stopped participating in the few existing strategies to migrate to the cities for better jobs that can assist them to support their families. I wish I could go to the city myself because nothing is here to do and the few is not lucrative; employment opportunities we expected from the park have failed while much priority is given to people outside the community rather than us.

We have been in this trading strategy for a very long time but there has not been any form of improvement. Though we expected that the introduction of tourism will help us have access to more credit facilities to improve our trading business, our expectations had not come to reality.

It can be discerned from the excerpts from the participants of the study that the establishment of the tourist site has brought nothing new in terms of improving their lot through livelihood strategies that have since been implemented by the powers that be. Their concerns appear to be genuine because the strategies they relied on in the past like farming, collection of NTFPs, petty trading, and basket weaving, etc. are the very ones they are currently relying on to eke out a living. In essence, the lofty promises made to them have not materialized and their plight keeps worsening day in day out.

2.7. Influence on livelihood strategies

The following excerpts capture the communities’ perception about tourism-related livelihood strategies employed by the powers that be at the tourist site to improve the standard of living and associated pleasures and displeasures expressed by people living in that catchment area about lack of new strategies and the sitting of the national park on their land resource.

Only about ten of the community members are working in the park with few others who are also working in the craft centre; it is not even consistent. The hotel which was just put up by a private man has not started operation so only about five young men have been given temporary employment by the owner to take care of the place till it fully starts operation.

We have not seen new strategies introduced in this community except the two men who are employed as tour guides. It is a cheat on this community; it is only Ahafo that has had some development and new livelihoods strategies. Hmmm, even Ahafo is the only community allowed to sell at the entrance of the park.

For this community, it hasn’t brought anything good apart from just the two people who happen to be working there that maybe they get some money to take care of themselves, it hasn’t brought anything good.

There is not even one strategy from the park has been introduced in this community; they have not done anything good for us since they came. If you come to this community and you happen to mention this name (Kakum National Park) we might not even give you water to drink.

I would be very happy should the park collapse because we have not benefited from the park since its establishment, even as we sit here should we be asked to demonstrate against them, I would gladly join in the demonstration.

If it is money from the laborer work, then yes, with that even if I want to do it today, I can go and do it right now and come back with money for my family”. For me, I am happy the park is here and I want the whites to come since it is a form of civilization for the community.

If we are allowed into the forest, then the forest would be destroyed, and all the trees would be cut down, therefore I won’t be happy if that happens. This is because when the park collapses, the people working there will become unemployed and it would bring problems into the community.

I cannot say the park has hurt my household rather than positive impact since our forefathers had money from the forest through the picking of snails, cutting of canes, etc. Though the establishment of the park has deprived us of all these benefits, I believe it is the changing situation in the world. As the world changes, things also change, therefore I cannot wholly say it hurts us; to a certain extent, it is good.

we do take pride in that since this community has become popular, for instance, when we go out and want to show someone where we come from, we tell the person we live at where the canopy walkway is and they easily locate us as a result of that.

At the beginning there were problems, but we later adjusted and coped with it. Even with that, it was just at the beginning, for now, we have adjusted, though there are still poachers around, they are punished when arrested. For this community, they have not arrested any of us because we are law-abiding.

They have done nothing wrong. They are working and when you flout their laws, they make you pay, therefore since there are laws we also have to follow and obey them.

It can be inferred from the extract that the sitting of the park is a mixed-blessing because the town has become popular worldwide. This is not surprising because tourists from diverse backgrounds across the globe in terms of race and social standing have become regular visitors to the site and this has placed the community on the map of the tourist world thereby bringing dignity and honour to the indigenes, Ghanaians, and the black race across the world.

2.8. Influence on livelihoods

The following extracts illustrate the distress that the indigenous communities sited in the catchment areas are currently going through because day-in-day-out a number of them go through hardships because they do not have any reliable source of eking out a living. Because the lands of their forefathers have virtually become part and parcel of the tourist site (the national park) thereby, depriving them of their source of livelihood.

If you are caught in the forest, you would be arrested. As if that is not enough, the way they would even beat you before jailing you is disturbing.

Ever since they established Kakum, they said we should not enter the forest ever again. Those of us who have landed there, should they come to meet you there, you would be arrested and beaten seriously to the extent that you may even die as they drag you through the forest to their office.

This community, we are scared because one old man who is suffering from illness happened to go into the forest, though the park management did not have any evidence on what he was doing, they beat and dragged him to the police station. It was serious because this man was bleeding in his old wounds. I think he is even dead now.

The Park has made life difficult; we do not get the medicines from the forest any longer. Food prices in the market have even gone high. Also, because this community and other communities are competing for livelihoods in the same side of the forest given to us, food is scarce and expensive now than before.

We are suffering; no work for us and our children and all other companies have collapsed due to the establishment of the park. We have educated youth who can work at the park but as I am talking most of them are jobless and some few have gone to the city in search of greener pastures.

All the things we used to get from the forest and that we sold to support our families have seized. This has resulted in most children dropping out of school since there is no money from any other strategies in this community.

No job has been created after the establishment of the park; the creation of the park rather destroyed the only form of employment we had in this community. They have taken our farmlands from us and also refused to employ our youth; they have also refused to ensure that we also benefit from the park. All this has affected our standard of living in the sense that previously, we could go into the forest to take whatever we needed to support our life but now we have been stopped and seized from entering the park, this means that all the things that we could have gone for to sell and support our life, we no longer have control over them.

With the state farm and the previous forest reserve, both men and women were given employment and the opportunity to work with them, it brought development to this community because they paid us at the end of every month and also gave us foodstuffs in the form of provisions. The government had a lot of local workers working there.

It can be discerned from the excerpts that; life has become a living hell for people within the tourist site. Their source of livelihood such as traditional medicine, which plays a significant role in the health delivery system of the rural folks is currently a thing of the past. Because the indigenes are not allowed to draw closer to the forest, and those who dare defy the order of the officials who manage the site are subjected to diverse forms of inhuman treatment thereby, making their lives a living hell and virtually reducing almost everybody to a life of squalor, deprivation, and sorrow. This, in turn, has a detrimental effect concerning the education of their children thereby exacerbating the poverty situation in that locality.

3. Discussion

Before the establishment of the tourist site, the indigenes of the community eke out a living by engaging in different activities. This is not surprising because they had competing needs and whatever they earned from one source of livelihood strategy was not enough to cater to all their needs. And this explains why they have to devise ingenious ways of earning extra income to supplement the mainstream of their income generation mechanisms. The common element that runs through their mode of generating income and sustaining their livelihoods is the use of a natural resource that they have been blessed with. Their survival in the past and within the current dispensation has always been driven by the forest that surrounds them or the elements therein. Scoones (Citation2009) describes sustainable rural livelihoods as the various levels of natural resources that improve the wellbeing and quality of life of individuals and groups residing in a specific locality. These natural elements have forged their lives in the past and into the future because it is endowed with a variety of natural resources that they can exploit to improve their lot. But the irony is that the establishment of the tourist site to some extent has changed their story, which can fittingly be best described as a mixed blessing. In line with this, Amoah and Wiafe (Citation2012) echo the fact that there is no doubt that diverse benefits associated with rural tourism development are attractive, however, the sacrifices to be endured by communities involved are unavoidable. In one breath, the existence of the park has brought their community to the limelight because tourists travel from far and near to visit the site to draw closer to nature to understand its essence through lived experiences thereby contributing to the sustenance of biodiversity, which is directly linked to human survival.

Despite the lofty ideals behind the creation of the tourist site, it has brought untold hardships to the indigenes of the community because the officers who are manning the site met out inhumane treatment to some of the indigenes of the community. Different studies (Mbaiwa & Stronza, Citation2010; Nkhata & Breen, Citation2010) identify poverty, lack of livelihood opportunities, and unequal contribution to livelihood conditions as resultant consequences of rural tourism on livelihoods of rural folks. Novelli (Citation2015) and Rakodi (Citation2014) point to the development of national parks as means to reducing poverty and improving the livelihoods of people living in communities close to these parks. The following excerpt succinctly captures the frustrations, pain, and sorrow that some of them have lived with over the years since its establishment:

If you are caught in the forest, you would be arrested. As if that is not enough, the way they would even beat you before jailing you is disturbing.

Moreover, with the establishment of the site and its negative effect on the survival of the indigenes, the majority of them have to engage in multiple-income generation activities to survive and this is having a toll on their health. Those who are unable to afford the high cost of health delivery in the hospitals and clinics resorted to the use of herbal medicine in the past. But with the establishment of the tourist site, such people are still not able to afford the high cost of health care but are also not allowed to go to those sites they use to harvest herbs with medicinal value. In essence, a lot of people are suffering from different kinds of ailments but cannot treat them because they do not have the wherewithal. In line with Melubo and Lovelock (Citation2019), Adu-Ampong and Kimbu (Citation2019), and Agyeman (Citation2005) development of national parks and reserves usually ends up restricting livelihood activities of local communities on their lands because their activities are considered unsustainable and threat to the environment.

Finally, the lives of innocent people are trampled upon by officers manning the tourist site because at the least suspicion innocent people are subjected to different forms of brutalities. This is creating a state of fear and panic in several communities in and around the site. The following excerpts capture the plight of the people in their quest to survive.

Everybody is scared in this community because one old man who is suffering from illness happened to go into the forest, but the officers did not have evidence of what he was doing, he was beaten up and sent to the police station. I guess he even died.

Contrary, the long-term national tourism development plans as described by Adu-Ampong (Citation2019), E. Adu-Ampong (Citation2018) and Teye (Citation2008) aim to extend development to rural residents especially those communities situated close to tourist attractions. According to Akyeampong (Citation2011), the continuous development of national tourism plans by various governments of Ghana is to effectively position tourism as a means of reducing poverty and which in turn, enhance and promote national development.

4. Conclusions

The study’s findings revealed that the potential exists for the use of tourism as a catalyst to improve the livelihoods of residents in tourist sites. The study revealed that tourism can be a mixed blessing because in one breath it has projected the community in question to the limelight across the globe. But the question that arises is the extent to which the site has contributed to the wellbeing of the indigenes within the catchment area. Undoubtedly, tourism can be used as a vehicle for the socio-economic transformation of communities within tourist sites and examples abound in several countries. But in the case of Kakum, the narrative is quite different because brutalities and arrests, poverty, and loss of sources of livelihoods have become a daily ritual etched in the lives of the people. This requires pragmatic steps need to be taken to alleviate the distress and associated resentments of the people. The lesson learned from the Kakum example is likely to inform policy decisions regarding siting of tourist sites in developing countries with socio-cultural contest akin to that of Kakum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mavis Adjoa Forson

Mavis Adjoa Forson is an Assistant Lecturer at the Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Ho Technical University, Ho, Ghana. She holds a Master of Science degree in Leisure Tourism and Environment from Wageningen University, the Netherlands, and a Master of Arts degree in Hospitality Management from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Her research interests include Sustainable Tourism Development and Livelihoods, Human Capital Management and Career Advancement for Women in Hospitality and Tourism, Role of Menus in the Hospitality Industry, Management of Food and Beverage Service, and Creative Tourism and Migration. This study relates to sustainable tourism development and livelihoods focusing on perceived interpretations by people living in local communities.

References

- Adu-Ampong, E. A., & Kimbu, A. N. (2019). The past, present, and future of sustainability in tourism policy and planning in Sub-Saharan Africa. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 119–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1580836

- Adu-Ampong, E. A. (2017). Divided we stand: Institutional collaboration in tourism planning and development in the central region of Ghana. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.915795

- Adu-Ampong, E. A. (2019). Historical trajectories of tourism development policies and planning in Ghana, 1957–2017. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1537002

- Adu-Ampong, E. (2018). Tourism and national economic development planning in Ghana, 1964–2014. International Development Planning Review, 40(1), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2018.2

- African Union Commission. (2015). Agenda 2063.

- Agyeman, Y. B.2005). Assessment of ecotourism impacts on rural livelihoods: Basis for exploring its potential for poverty alleviation: A case study of kakum national park in Ghana. Assesment Wageningen University.

- Ahebwa, W. M., Duim, R. V. D., & Sandbrook. (2011). Tourism revenue sharing policy at impenetrable national park, Uganda: A policy arrangements approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 20(3), 377–394.https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.622768

- Akyeampong, O. A. (2011). Pro-poor tourism: Residents expectations, experience, and perceptions in the kakum national park area of Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2010.509508

- Akyeampong, O., & Asiedu, A. (2008). Tourism in Ghana: A modern synthesis. Assemblies of God literature Centre Ltd. 29–31.

- Amoah, M., & Wiafe, E. D. (2012). Livelihoods of Fringe Communities and the impacts on the management of conservation area: The case of kakum national park in Ghana. International Forestry Review, 14(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554812800923381

- Ashley, C. (2000). The impact of tourism on rural livelihoods: Namibia’s experience. Working paper 128, London, UK: Overseas Development Institute. http://www.WAJAE.com.

- Ashley, C., & Hussein, K. (2000). developing methodologies for livelihood impact assessment: experience of the African wildlife foundation in East Africa. In: Overseas development institute working paper 129, London, UK: Overseas Development Institute.

- Asiedu, A. B. (2002). Making ecotourism more supportive rural development in Ghana. West African Journal of Applied Ecology, 3.

- Atisa, G. (2014). Analysis of global compliance and implementation of the goals of international environmental treaties: A case study of the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) (Doctoral dissertation, College of Arts and Sciences, Florida International University).

- Bediako, V. J. (2000). Sustainable ecotourism development in Ghana: A case study of the kakum national park (Doctoral Dissertation, MPhil thesis, Department of Geography, Norwegian University of Science and Technology Trondheim).

- Bennett, O., Roe, D., Ashley, C. (1999). Sustainable tourism and poverty eliminationstudy UK departmnet for international development (DFID)/Overseas development Institute (ODI). UK: London

- Bergman, Z., Bergman, M. M., Fernandes, K., Grossrieder, D., & Schneider, L. (2018). The contribution of UNESCO chairs toward achieving the UN sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 10(12), 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124471

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Caesar, V. K. (2010). The modification of the kakum forest reserve into a national park and its socio-economic and cultural implications on the livelihood of the surrounding communities. Soil science school of agriculture University of Cape Coast Cape Coast.

- Cobbinah, P. B., & Darkwah, R. M. (2016). Reflections on tourism policies in Ghana. International Journal of Tourism Sciences, 16(4), 170–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980634.2016.1212595

- Colglazier, W. (2015). Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science, 349(6252), 1048–1050. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2333

- de Oliveira, J. P., Balaban, O., Doll, C. N., Moreno-Peñaranda, R., Gasparatos, A., Iossifova, D., & Suwa, A. (2011). Cities and biodiversity: Perspectives and governance challenges for implementing the convention on biological diversity (CBD) at the city level. Biological Conservation, 144(5), 1302–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.12.007

- DFID, U. (2007). The sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. UK DFID Department for International Development: London.

- Duncombe, R. (2006). Using the livelihoods framework to analyze ICT application for poverty reduction through microenterprise. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Information Technologies and International Development, 3(3), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1162/itid.2007.3.3.81

- Fiagbmeh, R. F., & Buerger-Arnt, R. (2010). Local community’s perceptions and attitudes towards protected areas and ecotourism management: A case study of kakum conservation area, Ghana. In 2nd world ecotourism conference. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Ghana National Development Planning Commission. (2013). Medium-term national development policy framework National Dev. Commission.

- Gowreesunkar, V. (2019). African Union (AU) Agenda 2063 and tourism development in Africa: Contribution, contradiction and implications. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5(2), 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-02-2019-0029

- Gubbi, S., Linkie, M., & Leader-Williams, N. (2008). Evaluating the legacy of an integrated conservation and development project around a tiger reserve in India. Environmental Conservation, 35(4), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892908005225

- Huluka, A. T., & Wondimagegnhu, B. A. (2019). Determinants of household dietary diversity in the Yayo biosphere reserve of Ethiopia: An empirical analysis using sustainable livelihood framework. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1690829. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1690829

- IDS. (2011). What are Livelihoods Approaches?. RetrievedOctober 26, 2012, From: http://www.eldis.org/go/topics/dossiers/livelihoods-connect/what-are-livelihoods-approaches

- James, E. A. (2007). Qualitative data collection: Participatory action research for educational leadership. Educational Action Research,14(4),525–533.

- Joffe, H., & Yardley, L. (2004). Content and thematic analysis . Research methods for clinical and health psychology, 56, 68.

- Kollmair, M., & Juli, S. G. (2002).The sustainable livelihood approach. Input paper for integrated training course of NCCR North-South Aeschiried, Switzerland. Development study group, University of Zurich .

- Kumar, C. (2005). Revisiting ‘community’s community-based natural resource management. Community Development Journal, 40(3), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsi036

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry sage.

- Marchetta, F. (2011). On the move livelihood strategies in Northern Ghana.https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00591137

- Mayaka, M., Croy, W. G., & Cox, J. W. (2018). Participation as a motif in community-based tourism: A practice perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(3), 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1359278

- Mbaiwa, J. E., & Stronza, A. L. (2010). The effect of tourism on rural livelihoods in okavango delta, botswana. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(5), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003653500

- MBOKA (2008).Sustanable tourism dvelopment in Ghana. West Africa Travel Market. Banjul, The Gambia.

- McNamara, K. (2008). Enhancing the livelihoods of the rural poor through ICT, A knowledge map Overseas Development Institute and InfoDev InfoDev.

- Melubo, K., & Lovelock, B. (2019). Living inside a UNESCO world heritage site: The perspective of the maasai community in Tanzania. Tourism Planning & Development, 16(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1561505

- Mensah, C., Akyeampong, O. A., & Antwi, B. K. (2013). Residents’ perception of impacts of Amansuri Conservation and Integrated Development Project (ACID) in Jomoro District, Western Region, Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Development, 6(5), 73. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v6n5p73

- Mensah, E. J. (2011). The sustainable livelihood framework: A reconstruction.1(1), .https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/46733/

- Njana, M. A., Kajembe, G. C., & Malimbwi, R. E. (2013). Are miombo woodlands vital to the livelihoods of rural households? evidence from Urumwa and surrounding communities, tabora, Tanzania. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods, 22(2), 124–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2013.803774

- Nkhata, B. A., & Breen, C. M. (2010). Performance of community-based natural resource governance for the kafue flats (Zambia). Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892910000585

- Novelli, M. (2015). Tourism and development in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current issues and local realities Routledge.

- Ospina, S., & Wagner, R. F. (2004). Encyclopedia of leadership, qualitative research.

- Pandey, R., Jha, S. K., Alatalo, J. M., Archie, K. M., & Gupta, A. K. (2017). Sustainable livelihood framework-based indicators for assessing climate change vulnerability and adaptation for Himalayan communities. Ecological Indicators, 79, 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.03.047

- Paterson, A. (2011). Contractual tools for implementing the CBD in South Africa. In Environmental law and sustainability after Rio Edward Elgar Publishing. 341.

- Rakodi, C. (2014). A livelihoods approach–conceptual issues and definitions. In Urban livelihoods: A people-centred approach to reducing poverty. (pp. 26–45). Routledge.

- Ruth-mcswain, A. (2011). Gatekeeper or peacekeeper: The decision-making authority of public relations practitioners. Public Relations Journal, 5(1) 1–14.

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003)Techniques to identify themes. Field methods,15(1) 85–109.

- Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 171–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820503

- Sey, A. (2011). We use it different, Different: Making sence of trends in mobile phone use in Ghana. New Media and Society, 13(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810393907

- Teye, V. B. (2008). International involvement in a regional development scheme: Laying the foundation for national tourism development in Ghana. Tourism Review International, 12(3–4), 291–301.

- van Rijn, F., Burger, K., & Den Belder, E. (2012). Impact assessment in the sustainable livelihood framework. Development in Practice, 22(7), 1019–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2012.696586