Abstract

Using a qualitative research approach, this study provides an inquiry into the nature of democracy and digital political activism discourses on @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume prior to the 31st July demonstrations. Alternative communications spaces have revolutionised political communication in Zimbabwe. In Zimbabwe, political polarisation has created a monolithic voice in the mainstream media. In the ‘Second Republic’, digital activism is a growing phenomenon where subalterns question the state. This study is guided by Manuel Castells’ Power and Counter Power Theory. Data gathered using netnography was analysed using critical discourse analysis. Findings show that digital activism has turned into social media ‘dissidence’, calling for the resignation of the government officials including the Executive through 31st demonstrations. There is an intimate relationship between digital democracy and digital activism, enabling political advocacy and lobbying. Twitter is used to safeguard the lives of activists. Religious discourses were used by both Jacob Ngarivhume and Hopewell Chin’ono as they drummed up support for the July 31st demonstrations.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This present study is a contribution to the digital media and digital activism research in Zimbabwe and globally. This study provides a comprehensive discussion of existing scholarly debates. The ubiquitous nature of social media has enabled users to discuss topical issues. This article (re)traces various facets of digital activism and digital democracy in the post-Mugabe era. The authors explore how a journalist, Hopewell Chin’ono, and a politician, Jacob Ngarivhume, use Twitter to rally and mobilise the masses to protest against the ills of Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration on cyberspace. The 31st July demonstrations sought to (re)address democracy and human rights issues in Zimbabwe. The practical relevance of this article is to draw attention to how Twitter evolves to house cyber dissidence fighting against corruption and looting. The analysis made in this article will assist in understanding digital activism to academicians and policymakers in various contexts

1. Introduction

Besides public opinion formation processes, digital media is used to rally people for collective offline efforts, such as demonstrations. The Arab Spring is even known as the Twitter Revolution due to the use of Twitter to mobilise and sustain the demonstrations that toppled oppressive regimes in Egypt and Tunisia. Social media has been used to rally citizens to demonstrate against the government, with successes recorded such as the Tajamuka riots of 2016 and #ThisFlag demonstrations (Mugari & Cheng, Mungwari & Ndhlebe). Social media is liberative in countries made up of political repression (Chibuwe & Ureke). Twitter was used by @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume to mobilise people to act offline in the July31 demo, leading to the arrest, detention, and trial of the two activists on charges of incitement to participate in public violence.This article contributes to debates on digital activism and digital democracy in Zimbabwe by focusing on various forms that digital activism takes, and its ability to inspire collective offline activities. This study complements earlier studies on digital activism in Zimbabwe (Chibuwe, Citation2020; Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; Moyo, Citation2019; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019).

Digital activism is associated with civil disobedience as denial of service attacks, open-source advocacy, hacktivism, or hashtag activism (Poell & Van Dijck, Citation2014). Communication platforms play a significant role in politics, creating public opinion (Chibuwe, Citation2020). Cyberspace has transformed political communication globally. Although Twitter is slowly emerging to be an elitist public sphere where influential people in society are found, it has a big influence on public opinion. The “New Dispensation” has witnessed the infiltration and use of Twitter by government officials and politicians, even though the Executive has social media accounts. Mnangagwa’s administration has put strides to tamper and control internet use and the rampant internet traffic to its advantage. Nonetheless, there is sparse empirical evidence specifically documenting the limitations to internet access in Zimbabwe amidst protests. The ZANU PF-led government has continued to throttle the internet as a strategy to control and monitor protesters, while security institutions unleashed brutality on activists.During the January 2019 riots, the internet was unconstitutionally turned off all over Zimbabwe, while Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp were permanently cut off. Zimbabweans resorted to alternative means of communicating, though it was tedious to have real-time updates. Ironically, Robert Mugabe ever turned off the internet during his reign. However, it must be noted that subalterns are rarely misled by conservative images of elites. Given such binaries, social media rarely changes how netizens process information rather it amplifies these tendencies.

While regimes can utilise social media to undermine democracy, netizens also use cyberspace to address the democratic deficiency experienced. In other words, this study goes beyond unpack the term netizens within the context of digital democracy (see, Hauben & Hauben, Citation1997). According to Hauben and Hauben (Citation1997), cyberspace contributes immensely to the networking of users sharing similar interests. Netizens are occupants of online societies bound by intellectual activities presented and discussed (Hauben & Hauben, Citation1997; Mossberger, etal., Citation2003). Pattie etal. (Citation2004) argue that citizenship is composed of norms and values, enforcing a collective approach to problems based on the rights and obligations of a political community. This study acknowledges that citizenship is no longer geographically defined but digitally defined. It is crucial to note that netizens’ interactions before the 31st demonstrations are grounded in the socio-political dynamics influencing the nature of digital democracy. Therefore, netizens can be either pro-government or anti-government. (Mungwari & Ndhlebe Citation2019). Social media is liberative in countries made up of political repression (Chibuwe & Ureke Citation2016). Twitter was used by @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume to mobilise people to act offline in the July31 demo, leading to the arrest, detention, and trial of the two activists on charges of incitement to participate in public violence.These offline experiences are brought back online again in a back-and-forth spiral, and this study aims to investigate these facets of digital activism and how they translate to physical offline action, initiated and sustained by social media.

The political participation of netizens is evident through hashtag activism. Hashtag activism raises awareness of issues by either fighting against or supporting a cause. Hashtag activism is an identifier of social movement and engages netizens into socio-political. In the digital era, activism creates netizens’ subscription to democratic practice, apolitical understanding, and consciousness towards political events (Dennis, Citation2019). Technology improves or undermines democracy depending on how it is used and who uses it, and also who controls it; hence, this study aims to find out how, and for what purposes @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume have been using Twitter towards the July 31st demonstrations. Zobl and Reitsamer (Citation2012, Citation2014) argue digital platforms have opened up new possibilities for resistance activism towards dominant discourses by those marginalised in mainstream political debates. Social media has transformed the political landscape in Zimbabwe. Since the colonial era, the Smith government used mainstream media to propagate political ideology while clamping down on private press to suppress subaltern voices. This was, however, inherited by the Mugabe regime after independence, and re-inherited by the “Second Republic” led by President Mnangagwa after the November 2017 coup. Unlike Mugabeism, the “New Dispensation” has seen more digital activism because initially dissent was tolerated.

2. Background and context of the problem

Social media is a haven for Zimbabweans. E-democracy is a growing phenomenon in the post-Mugabe era. Baba Jukwa marked the genesis of digital activism in Zimbabwe by exposing (political) assassinations, corrupt and evil machinations of Robert Mugabe, and human rights abuses (Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016). Social media plays a significant role in political communication. The Arab Spring in 2010 led to the control of social media use by regimes (Matingwina, Citation2018). This saw political revolutions emanating from overthrowing governments in countries like Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya (Matingwina, Citation2018; Mukhongo, Citation2014). Digital media are notable for radically extending silenced subaltern voices.

The notable results yielded by digital political activism include #RhodesMustFall (#RMF) against racism in South Africa, #Thisflag and #Tajamuka in Zimbabwe (Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019). Digital media continues to challenge power. While ZANU PF used to ignore social media and concentrated on traditional media, the “New Dispensation”, in a bid for total hegemonic control, sought to counter this with “Varakashi” (online media bashers; Chibuwe, Citation2020; Mugari & Cheng, Citation2020; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019). ZANU PF supporters go online to counter pro-democracy activists. Besides Varakashi, top officials, including the President and Presidential spokesperson George Charamba, have Twitter accounts to counter digital activism. From this backdrop, this study intends to find out the scope of digital activism in the “Second Republic”.Studies on the (re)emergence of digital activism in the “Second Republic” are growing arguing that the internet has empowered Zimbabweans (Chibuwe, Citation2020; Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; Dendere, Citation2019; Matingwina, Citation2018; Saunders). Digital media is a site of mass resistance (Chatora, Citation2012; Gallagher, Citation2015; Mhiripiri & Mutsvairo, Citation2013; Moyo, Citation2009; Mutsvairo & Sirks, Citation2015). According to Knoll et al. (Citation2020), netizens use social media to verify the relevance of new information, subsequently determining the attention required. Internet is a source of counter-power and insurgent politics (Castells, Citation2007; Fuchs, Citation2009).

Social media has contributed extensively to the formation of online democratic participatory modes including e-participation (Gibson & Cantijoch, Citation2013; McLoughlin & Southern, Citation2021). Existing scholarship submits that tiny acts, low-threshold and low-cost political behaviours like views, sharing of posts and liking stimulate users’ interests in political participation (Margetts et al., Citation2015; Theocharis, Citation2015; Vaccari et al., Citation2015). Dennis (Citation2018) concludes that these actions do not reduce users to keyboard warriors as proposed by earlier scholarship. Political participation is “any behaviour by ‘ordinary citizens’ influencing political outcomes,” (Brady, Citation1999, p. 737). Political participation is relevant in mobilising activism. Netizens are either intentionally or incidentally exposed to political content resulting in low-effort and high-effort forms of participatory actions (Knoll et al., Citation2020). Exposure further leads to the development of political interests and commitment over time. Dennis (Citation2019) refers to this form of participation as a continuum of participation that politically motivates netizens. Online political participation in Zimbabwe was visible in the much celebrated Operation Restore Legacy on cyberspace.

In 2020, Hopewell Rugoho-Chin’ono an award-winning documentary filmmaker and an international journalist reported on alleged COVID-19 procurement fraud within the Health Ministry, leading to the arrest and firing of then Health Minister Dr Obadiah Moyo. Hopewell was arrested and charged with inciting public violence, and before his arrest, he used Twitter to inform netizens about his arrest, deemed an abduction. Amnesty International accused Zimbabwean authorities of misusing the criminal justice system to persecute journalists and activists. Freed in September on bail, he was arrested again in November 2020 and charged with obstructing justice and contempt of court for a tweet about the court outcome of a gold smuggling scandal.Jacob Ngarivhume is the leader of the Transform Zimbabwe political party aiming to cultivate leaders from different demographies and was part of the MDC Alliance during the 2018 harmonised elections. Ngarivhume was arrested on charges of inciting public violence with allegations of contravening Section 187 (1) (a) as read with section 37 (1) (a) (i) of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act, Chapter 9:23. The economic conditions in the “Second Republic” have made Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume speak back to power. The duo have utilised Twitter to create awareness for the suffering masses. Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume are organic intellectuals. This study addresses the nature of discourses on democracy and digital political activism on @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume. This study contributes to the existing literature on democracy and political activism in Zimbabwe by giving more attention to democracy and political activism in the “Second Republic”. It takes a multi-pronged or rather, a holistic analysis of digital activism in the “Second Republic” through investigating the various facets that digital activism takes in attempts to transfer online solidarity to offline physical collective action.

While other key online movements such as Baba Jukwa, #Tajamuka/Sesijikile, #ThisFlag have been studied (Chibuwe, Citation2020; Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; Matingwina, Citation2018; Mugari & Cheng, Citation2020; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019). there have been no studies on the July 31st, 2020 demonstrations, hence the need for this study.This study uses a different theoretical framework from the majority of other scholars who have undertaken almost similar studies. This study utilises the power and counters power theory (Castells, Citation2011) to understand how online networks are formed and sustained to resist power. This theory shows how violence against the powerful is legitimised and made common-sensual. Previous studies have not utilised this theory before, which makes this study important as it breaks new ground. While there is growing consensus that online movements are leading to successful offline physical action in Zimbabwe such as the 2016 #Tajamuka and #ThisFlag demonstrations (Mugari & Cheng, Citation2020; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019). No study has focused on factors motivating citizens to partake in these demos, and this study focuses on that previous studies have only celebrated the successes without taking stock of where these successes are coming from. This study informs both digital media activists and policy planners on online motivators of offline political actions.

3. Review of related literature

Social media platforms have revolutionised political communication in Zimbabwe. There is consensus among scholars that cyberspace is a counter-hegemonic space where subalterns speak back to power (Mathuthu, Citation2014; Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; Chibuwe, Citation2020; Madenga, Citation2021; Moyo, Citation2009; Mpofu, Citation2015). Mutsvairo and Columbus (Citation2012) note that political polarisation has led Zimbabweans to freely express their opinions online, compared to the mainstream media. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume migrate to cyberspace to question the ZANU PF government on its failure to uphold democratic practices and human rights, and this study investigates the full range of actions planned and orchestrated via Twitter. The use of new communication technologies helped publicize extra-legal activities and human rights abuses often blamed on ZANU PF affiliated militia groups and the security forces. Mpofu (Citation2013) argues that media censorship has led Zimbabweans to seek secure spaces to deliberate and express their views. Studies acknowledge the presence of cheap Chinese mobile phones has increased citizenry migration to digital spaces (G. Gukurume, Citation2017; Mhlanga & Mpofu, Citation2014; Mpofu, Citation2015). This study, therefore, intends to find out how Twitter users attain and wield through networks.

In the 21st century, social media use has been adopted by journalists. Scholarship on journalism discusses the affluence of citizen journalism during the crises (Campbell, Citation2015; Ncube, Citation2019; Moretzsohn, Citation2006; Moyo, Citation2009; Radsch, Citation2011; Rodríguez, Citation2001). Social media has enhanced journalistic performance as a watchdog in polarised media ecologies. Ncube (Citation2019). notes that media polarisation remains the hub of the “Second Republic” making the populace lose trust in the mainstream media and open “authentic” information dissemination avenues. This has restructured the communication and power matrix in the post-Mugabe era (Ncube, Citation2019). This study shows how @Hopewell Chin’ono, through investigative journalism, is even able to provide truthful information on COVID-19 funds looting, which is even taken up by traditional mainstream media. Citizen journalism is an activist form of news reporting functioning outside mainstream media institutions. Studies on citizens’ journalism show that citizen journalism is a response to shortcomings in professional journalistic across the globe (Atton, Citation2003; Ncube, Citation2019). In Zimbabwe, citizen journalism continues to bring out gross violations against citizenry (Chatora, Citation2012; Moyo, Citation2009). Mabweazara, (Citation2020). notes that citizen journalism is ubiquitous in offering alternative facts censored by regimes. There is a limited academic inquiry discussing how citizen journalism inspires various forms of digital activism and its ability to inspire collective offline activities in the “Second Republic”.

Studies also examine the intermediate relationship between digital activism and political activism. Social media use has grown rapidly over the last decade. Scholars argue that social media are a place of political socialisation providing information required to make political choices (Chibuwe, Citation2020; Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; Mabweazara, Citation2011; Mare, Citation2016, Citation2018; Moyo, Citation2009; Mutsvairo & Sirks, Citation2015). Social networking sites are undoubtedly emerging as a key venue for political debate and discussion and at times a place to engage in civic-related activities (Moyo, Citation2011: Storck, Citation2011; Tendi, Citation2016).

Cyber-activism is not a new phenomenon in Zimbabwe. The 2008 harmonised elections brought a new dimension to political activism (Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016). Moyo (Citation2011) illustrates how Zimbabweans resorted to blogging to air out suppressed voices during the period Ndlovu Gatsheni (Citation2015) terms Mugabeism. Political activism in Zimbabwe was nurtured by the Baba Jukwa Facebook page which empowered the subaltern to actively discuss politics without the fear of being arrested (Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016). While Mare (Citation2016) views Baba Jukwa as an epitome of a citizen journalism channel in Zimbabwe, Mutsvairo and Sirks (Citation2015) conclude that digital activism is the enactment of political action through ICTs. Also, Tajamuka Sesijikile as both a digital and political movement, Pastor Evan Mawarire posed an impact on Zimbabwean netizens (Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019). Mungwari and Ndhlebe (Citation2019) contend that the new wave of digital activism was ignited by Pastor Evan Mawarire’s #ThisFlag movement in 2016. Social movements and campaigns in Zimbabwe represent a third political force outside government and political parties. This has seen the growth of hashtag activism an influencer to netizens’ participation in mass movement and protest. The concept and practice of Hashtag activism are relatively new in Zimbabwe and thus remain under-theorised in various contexts. Using hashtags, netizens bring out human rights abuses, justice for victims, awareness against government ills, hence injecting new voices into public discourse. Building on already existing discussions, the article views the nature of discourses on democracy and digital political activism raised by Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume before the 31st demonstrations as a phenomenon worth investigating.

Although people engage in political discussions on social media, it remains debatable if digital activism is translated into active political participation. Scholars show that social media creates and reinforces false consciousness among users, which hinders the translation of twitting into action (Chiumbu, Citation2015; S. Gukurume, Citation2019). Nonetheless, Mungwari and Ndhlebe (Citation2019) disagree with the fore mentioned scholars (Chiumbu, Citation2015; Gukurume, Citation2017) highlighting that social media movements do translate into political action as exemplified by the #ThisFlag movement and #Tajamuka/Sesijikile. This false consciousness has unintended consequences for reproducing the oppressive status quo that subaltern voices are trying to fight (G. Gukurume, Citation2017). In South Africa, social media is an activism space for movements disseminating counter-hegemonic narratives. These spaces fell prey to power dynamics militating against their morphing into physical political activism (Chiumbu, Citation2015). Chibuwe and Ureke (Citation2016) argue that the Internet poses danger to political activism as every netizen can be a content creator. Instead of ushering digital activism into political action, cyberspace ended up providing rooms for slander and defamation. Ncube (Citation2019) shows that citizen journalism is characterised by fake news interwoven with cyber-propaganda. For this study, one of the two under investigation, @Hopewell Chin’ono is a qualified journalist, and this inquiry attempts to find out whether he follows journalism ethics or not.

There is a growing scholarship discussing the role played by online activism as an enabler or inhibitor of physical political activism (Chibuwe, Citation2020; Chiluwa, Citation2012; C. Moyo, Citation2019; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019; Willems, Citation2016). C. Moyo (Citation2019) submits that social media have been resoundingly successful in facilitating civil resistance across the globe. The famous notable online activism that transcended into the physical political activism is the Arab spring in 2011, turning it into a socio-political plague with most of the Arabic countries (Chiluwa, Citation2012; Liaropoulos, Citation2013; Mugari & Cheng, Citation2020; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019; Mutsvairo & Sirks, Citation2015; Tendi, Citation2016). Digital activism is a site for civil disobedience (Tendi, Citation2016).

The concept of (digital) activism is connected with the idea of struggle, pain, and even physical and mental sufferings. For example, the Tunisian, Egyptian and Libyan cases are outstanding digital activism that fostered fundamental changes within regimes. Tunisian scenario sparked the Arab Spring, which saw the rise of networks by the digital elite reporting on the magnitude of protest events (Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; Chitanana, Citation2020; Elyachar & Winegar, Citation2012; Langmia & Glass, Citation2014). In as much as digital media is acknowledged for fostering activism, Mugari and Cheng (Citation2020) conclude that social media pose a serious national security threat, citing the 1 August 2018 demo and eventual shooting as caused by social media, which publicised the July 31 elections before the national electoral body, ZEC, did so. From this context, we argue that social media has eroded its credibility, hence the message is not believed.

Tendi (Citation2016) brings about a different thought in regard to the relations between online activism and physical political activism within a Zimbabwean context. Social media activists ignore the realities of power; thus, Zimbabwean online activists learned nothing from the Arab Springs unlike the Egyptian revolution (Tendi, Citation2016). Storck (Citation2011) contends that Egyptian activists successfully managed to coordinate protests using Twitter and Facebook. Castells (Citation2011) notes that power relationships are the foundation of society with institutions and norms constructed to fulfill the interests and values of those in power. On the effectiveness of digital activism, Mungwari and Ndhlebe (Citation2019, p. 284) argue:

Mawarire managed to take people to the streets in their numbers through social media. He was obeyed, his commands were obeyed, and he brought business to a standstill when he called for a stay away. It was a resounding success, thanks to social media

This article proves that @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume managed to mobilise both Twimbos and the ordinary citizens of Zimbabwe into taking part in the 31st July demonstrations. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume in contemporary Zimbabwe have become opinion leaders speaking against the Mnangagwa regime. As a result, scholars have concluded that most digitalised political movements in Zimbabwe and the world at large remain Twitter or Facebook revolutions instead of political action (Chitanana & Mutsvairo, Citation2019; Christensen, Citation2009, Citation2011; Dendere, Citation2019).

Online activism is characterised by cyberwars among netizens with different political interests. Tendi (Citation2016) alludes to the fact that militarism has been essential since the Mugabe era in quelling civil unrest as such social media activism can never substitute for organized political activity on the ground. Studies show that cyberspace is slowly being militarised by the state (Chibuwe, Citation2020; C. Moyo, Citation2019). Chibuwe (Citation2020) views cyber-contestation as a common trend among Chamisa’s followers, Nerorists; and Mnangagwa’s followers, Varakashi. Mwareya (Citation2019) contends that Varakashi is Zimbabwe’s online army, which is anti-progressive civil society and opposition parties and seeks to counteract online activists inspired by democracy and human rights discourses. Varakashi has changed the face of social media dynamics and activism in Zimbabwe (Chibuwe, Citation2020; C. Moyo, Citation2019; Mwareya, Citation2019).

Wherever there is power, there is counter-power enacting the interests and values of those in subordinate positions in society (Castells, Citation2011). Therefore, power is multidimensional. Twimbos are aware of the limitations of social media. Digital communications continue (re)shape and (re)fine power matrix. Perhaps in unpacking the digital activism McLuhan (Citation1964)’s argument that the medium is the message is essential. Twitter has an excellent system of metrics that allows us to measure success in the number of friends, likes, retweets, and shares. Scholars submit that social media is like a magic bullet against authoritarianism (Grossman, Citation2010; Mandikwaza, Citation2013). Dennis (Citation2018) argues that e-participation creates a personalised political identity that constitutes political engagement. Online participation behaviours enhance offline engagement of political activism mobilising citizenry into collective action (Cantijoch et al., Citation2016; McLoughlin & Southern, Citation2021). McLoughlin and Southern (Citation2021) contend that online participation behaviours and offline engagement of political activism are interwoven, developing into a participatory ladder made up of low intensity and passive forms of online engagement. Tweets made by @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume serve as a stimulus operating low efforts of political acts influencing ground direct action of the 31st of July protests.

Netizens utilised Twitter to air out observations around the 31st demonstrations. Twitter enforced a grassroots connection of the marginalised netizens to have a voice. Twitter is the medium of the moment due to its fast mechanism to disseminate information through hashtags and trending tweets retweeted. In essence, unlike other social media platforms, Twitter has a “promiscuous” connection. Social media promotes political participation whereby users execute both behaviours to achieve a goal (Knoll et al., Citation2020; Matthes et al., Citation2020). Users engage in low effort online political participation upon stimulation of political agenda pursued by lowly engaged users (Matthes et al., Citation2020). Low effect political participation influences high-effort political participation resulting in the adoption of the subsequent behavioural situation (Knoll et al., Citation2020).

The collaboration of a journalist and a politician in fostering online political participation yields offline political participation. Twitter is a personalized space and its effects depend on how netizens use it. These distinct features of political participation come in handy in understanding how @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume as marginalized actors within democracy utilise social media to organize and advocate for political participation. From this body of the literature, it is evident that @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume are not just computer keyboard warriors but politically active beyond computer mice. This study is unique in fulfilling a literature gap by exploring the nexus between political activism and democracy in the “Second Republic”.

4. Power and counter-power theory

This study uses Castells’ Power and Counter Power Theory. Castells (Citation2007) notes that digital media lead to a profusion of horizontal interactive communication as people build personalised communication channels. In the “Second Republic”, there is an increase in new communication networks distributing content to enhance interaction with the audience compared to traditional mainstream media. Castells (Citation2011) argues that power in the network society is exercised through networks. Power is a fundamental process in a society enabling the social actor to influence asymmetrically the decisions of other social actors in ways that favour the empowered actor’s will, interests, and values (Castells, Citation2009; Fuchs, Citation2009). There is an interplay between existing and emerging communications platforms and spaces, which have resulted in journalists, politicians, and audiences’ attempts to conceptualise the contemporary public sphere. Fuchs (Citation2009) argues that in a networked society, power is exercised using coercion based on the discourses through which social actors guide their actions. However, Castells argues that “the ability to successfully engage in violence or intimidation requires the framing of individual and collective minds” (Castells, Citation2011, p. 779). @Hopewell and @Ngarivhume, by showing the unbridled disregard for ordinary people’s lives as government condones corruption in drugs procurement yet the deadly COVID-19 pandemic is at Zimbabwe’s doorstep, legitimise the use of force against this “heartless” government. The evolution of technology has changed the operations of the public sphere (Dahlgren, Citation2009; Papacharissi, Citation2014). These concepts are instrumental in questioning the operation of the alternative spaces in Zimbabwe and how they aid E-democracy and digital political activism.

Twitter is a counter-hegemonic medium utilised by @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume to deliberate issues patterning digital democracy and political activism. This theory is significant in unpacking the formulation of public opinions to democracy and political activism through what Habermas (Citation1962/1989) views as communicative power. Social media platforms are diverse virtual communities open for netizens to have the same power to answer back. Social networking is already a mainstay of everyday life and its use and importance within political communication. Power and Counter Power Theory, through mass self-communicating, also details how power is exercised, that is, how @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume convince citizens that after endangering citizens by looting COVID-19 funds, the Zanu-PF government ’deserves’ to be impeached. Ahmed et al. (Citation2016) argues that on social media platforms users receive information more often compared to direct exposure alone. Power in the network society is exercised through networks. Castells (Citation2011) discusses the four major forms of power that exist in a network society, namely networking power, network power, networked power, and network-making power. Social actors establish power by constituting a network that accumulates valuable resources and then by exercising their gatekeeping strategies to bar access to those who do not add value to the network or who jeopardize the interests that are dominant in the network’s programs (Dahlgren, Citation2005).

@Hopewell and @Ngarivhume created a network that speaks out about the state’s misuse of resources and also clampdown on human rights activists and citizens’ freedoms. This is a counter-power whereby digital activism is used to challenge the political status quo. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume are critical voices in lampooning the ZANU PF government. Based on the arguments presented by Castells (Citation2011) @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume are using the communication architecture of Twitter to influence user-generated content creation. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume circulate counter discourses to critique the dominant discourses of dominant publics. For Fraser (Citation1990) the widening discursive contestation on counter-hegemonic spheres is fuelled by the presence of counter-publics or subalterns. Building on Fraser’s concept of subaltern counter-publics, this study stresses the nature of Twitter as a discursive and conversational domain allowing the networking of marginalised groups to deliberate on issues of common concern. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume react, question, and deliberate on issues concerning democracy, human rights abuses, corruption, and looting done by the government officials and politicians. Government officials and politicians are viewed by Fraser (Citation1992) as the dominant publics. Gibson et al. (Citation2011) submit that counter publics transform public opinion reflecting on specific interests. Hashtag as innovations used to coordinate Twitter mobilisation, this study is interested in unpacking how activists use Twitter as a space of regrouping and training ground to mediate political action in Zimbabwe.

@Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume as subaltern counter publics utilise alternative communication spaces to question the official consensus. According to Fraser (Citation1990) subaltern counter-public advocates for alternative styles of political behaviour to attain collective actions. Counter elites operate within the official public sphere, as leaders of public opinion, trade unions, or professional associations. But citizens use the Internet as a space for ’self-communication nowadays’ (Castells, Citation2009). Prior to the 31st demonstration, @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume turn Twitter into a platform for critical discussion and political mobilisation against the power bloc. Holston (Citation2008) views this as insurgent citizenship, Twitter is an alternative space of participation through which @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume utilise citizen rights to foster discursive interactions and micro-politics of participation in cyberspace. Counter power is exercised in the network society by fighting to change the programs of specific networks and by the effort to disrupt the switches that reflect dominant interests and replace them with alternative switches between networks (Castells, Citation2007). Digital media activism aims to make people aware of their deplorable lived realities, the society defines ‘whose power can be exercised and how it can be exercised” (Castells, Citation2011, p. 779). Therefore, this study attempts to find out how @Hopewell and @Ngarivhume legitimised violence against the government by calling for the July 31st demo.

5. Methodology

This study is a qualitative research using Bryman (Citation2012)’s interpretive approach to understand the meanings of the nature of discourses on democracy and digital political activism raised by Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume. The researchers chose the qualitative research approach as it paves the way into understanding the phenomena under study, consequently answering the problems within the context of the populations involved (Yin, Citation2009). This study relies on data obtained from a first-hand observation, thus becoming the most ideal research approach for this study is questioning the significance of digital political activism and democracy discourses on social media platforms. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume are the case studies analysed to obtain emic data on the nexus of digital democracy and digital political activism on social media platforms. A case study allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings (Yin, Citation2011). A case study explains how and why digital activism has become rampant in the “Second Republic” through unpacking thematic issues discussed by @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume before the 31st demonstrations.

Netnography was used as a method of data collection that is dependent on digital traces of naturally occurring public conversations on communications networks (Kozinets, Citation2006, Citation2015). The researchers were complete observers on Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume Twitter handles for a period of 3 months from May 2020 to July 2020. When the researchers observed Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume Twitter handles, attention was given to how Twitter activities on these handles fluctuated within the period under observation. The tweeting activity by Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume in mobilising the 31st demonstrations indicated the importance of slacktivism (see, Dennis, Citation2019). Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume represented the spontaneous opinions of a subset of Twitter netizens, thus can translate into a score for a public opinion before the protests. For instance, Hopewell Chin’ono’s single tweet would reach more than 5000 retweets, 10,000 likes, and 4000 comments. Daily, tweets made by Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume trended reaching more than 120,000 users measured by retweets done. The window of observation was relatively large, enabling the researchers to identify different trends in the data that might help confirm the overall validity of political participation. In monitoring the user activity, various approaches were used.

The researchers used a keyword search or advanced search command mechanism, which highlighted up to 50 tweets done within 7 days. The command often used include 31st July, daddyhope, and zimlivematters to monitor the real engagement between netizens and activists yielding the required data. Also, the duo utilised hashtag campaigns which trended throughout Twitter not only to Zimbabwean users but globally receiving waves of support towards the 31st demonstrations. Hashtags became an effective strategy to monitor @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume. Launching various hashtags facilitated netizen reaction providing insights into everything that happened around the hashtag and also what users participated. Although it is difficult to quantify the numbers of tweets made during this period by Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume and the audience reached, we observed that tweets made were indeed a driving force to the initiation of the 31st demonstrations regardless of the duo being arrested. As we observed tweets made, upon reaching saturation point researchers purposively selected and archived 100 relevant tweets categorised along thematic lines based on their importance and response to the objectives of the study. Folders were created to store the screenshots in personal computers (PC) awaiting analysis.

Thematic analysis and critical discourse analysis (CDA) were used to analyse selected tweets. Wodak (Citation2008) argues that CDA aims to unpack power contestations within a constructed text to attain meaning. Critical discourse analysis becomes useful in understanding how tweets on democracy and political activism are constructed by Hopewell Chin’ono and Jacob Ngarivhume before the 31st demonstrations. Twitter being a virtual community, power dynamics are at play when shaping discourses about the 31st demonstrations. Thematic analysis was instrumental in the identification of patterns and themes emerging from a range of discourses on digital activism and e-democracy disseminated during the period under study. Findings are discussed themes below.

6. Social media “dissidence” in Zimbabwe

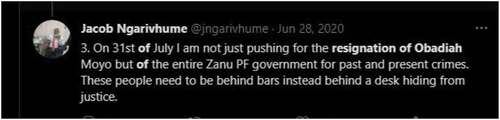

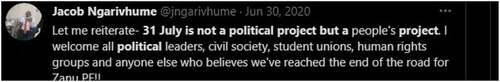

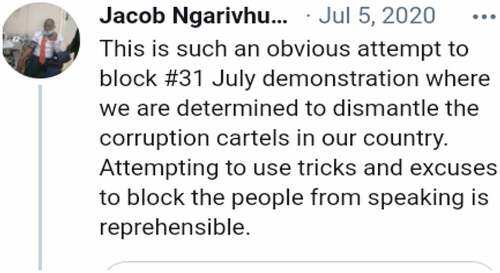

One of the dimensions of digital activism amounts to “dissidence in Zimbabwe. Through Twitter, there are calls to unseat a democratically elected government violently. Twitter has emerged as a sphere housing ”cyber dissidents’ who form networks and rally citizens to take physical actions of dissent against the government such as demonstrations, for instance, the July 31st demonstrations. Researchers observed that a politician and a journalist unified for a single cause that Zanu-PF must be removed from power. Both @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume tweeted that “Zanu-PF must go” a sign that the duo calls for a change of government. Ngarivhume calls for the Zanu-PF government to resign:

Ngarivhume advocates for government officials, including the President, to be put behind bars. @Jacob Ngarivhume invites political groups, civil societies, and races to take part in the 31st July demonstrations.

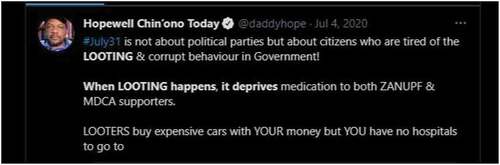

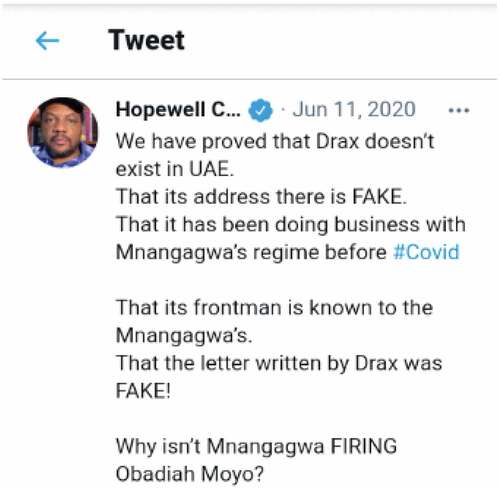

Hopewell exposes corruption in COVID-19 meds or prevention procurement to rally Zimbabweans against the government. @Hopewell Chin’ono even uses the hashtag #JULY31 #LOOTERSMUSTGO and this shows the violent removal of the government from power.

Hopewell tweets:

Digital media is used for political mobilisation and fostering violent movements against the government. @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono used hashtags to lure people to take part in the 31 July 2020 demonstrations. @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Jacob Ngarivhume legitimise violence against the government, even invite citizens, regardless of political affiliation to participate in the demonstration. This is done by meticulously revealing that government officials are looting COVID-19 medication funds and endangering the population, hence justifying violent removal of the government. According to Castells (Citation2011), anyone who can rally collective minds can mete out violence, not only the State. Although theories of power and historical observation point to the importance of the state’s monopoly on violence as a source of social power. The ability to successfully engage in violence or intimidation requires the framing of individual and collective minds (Castells, Citation2011, p. 779). Corruption endangers the whole country in the face of a deadly virus that is used to legitimise the removal of that government. Twitter is being used in the bid to remove Zanu-PF from power immediately, without going for elections. Due to the success of online movements to mobilise citizens to riots, such as the Tajamuka riots of 2016 and Pastor Evan Mawarire’s #ThisFlag demo, the Government has even gone on to brand social media activists as dissidents. As such, the researcher observed that the digital activism led by @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono is meant to inspire offline political activism calling for the violent removal of government from power, just like the Arab Spring.

7. Social media as an enabler of offline political activism

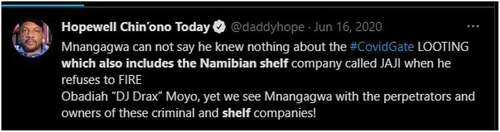

Social media as an enabler of offline political activism is another dimension of digital activism. If used well, Twitter can lead to offline collective action. Truthfulness and accuracy are elements that push people further into taking action. Hopewell exposed Obadiah’s alleged corruption and the Jaji Investments saga, which then angered the people. Hashtags used by @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono include #ObadiahMoyomustgo, #COVIDgate, #July31, #Zanupfmustgo, #zimlivesmatter, and #brokendemocracy. The tweets below expose the government and hold information that can potentially anger the people, leading to offline action.

@Hopewell Chin’ono presents truthful information as regards the corruption by Health Minister Obadiah Moyo and links between President Mnangagwa and Delish Nguwaya, who fronts for Drax International and Jaji Investments.

… when Interpol flagged the US$2m LOOTING payment by Mnangagwa’s regime. Drax went and changed its name from Drax Consult to Drax international. It is a LIE that the government of Zimbabwe didn’t know that. They are part of the criminality, they Knew and the evidence is there …

Hopewell shows that his information is truthful with the words “evidence is there”. By showing how the government has been awarding tenders, yet they “Knew” of Drax’s brush with the international law builds public anger, and therefore justifies the need for the July 31 demonstrations.

@Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono used hashtags to get people to take part in the 31 July 2020 demonstrations. @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono successfully served as enlightenment strategies to inform Zimbabweans of the ill doings of the government and politicians. These hashtags enabled the active participation of several different netizens. the use of these fore-mentioned hashtags enabled netizens to easily follow activities on the @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono demonstrations call.

@Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono have bestowed hope and faith that the 31st July movement or protest will bring forth change in the political arena as illustrated below,

… @ZtcuZimbabwe and @Zinasuzim, all political groups, civic society, people of all ages and races. The time has come for voices to be heard in Zimbabwe, on the continent and beyond- we want to change!!!

The tweet calls for participation from anyone and everybody, hence calling for offline political activism. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the misuse of COVID-19 Funds meant to buy procurements to assist the nation. However, Hopewell, a journalist, through investigative journalism exposes corruption in the procurement of COVID-19 drugs and protective equipment. A journalist and politician are unified under a common cause, which is to fight corruption. @Jacob Ngarivhume uses the hashtags #31july #paybackthemoney while @Hopewell Chin’ono uses #JULY 31 #LOOTERSMUSTGO. This study established that social media dissidence in Zimbabwe has replaced the role of mainstream media as the watchdogs of the society, which has failed to report on corruption.

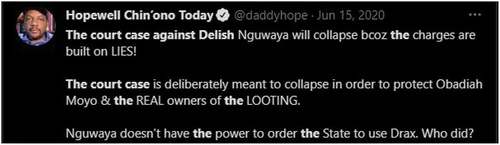

@Hopewell Chin’ono questions how Health Minister Dr Obadiah Moyo is not treated like any common criminal crime or any Zimbabwean arrested for breaking laws. For instance, @Hopewell Chin’ono highlights the former Health Minister doesn’t sleep in jail cells and the handling of the corruption charges in the courts proves that charges won’t stick despite the evidence against him. Sadly, this doesn’t only happen to the former Health Minister, but also to Delish Nguwaya, who walked away scot-free. This is depicted on the screenshots below

Drax International is not the only off-shore company used by government officials to loot state funds. From the tweets @Hopewell Chin’ono, the researcher observed that there is a second company implicated in the COVID gate scandal. An offshore company, Jaji Investments, in Namibia was set up by Mnangagwa’s close allies to loot public funds. This company is named according to the tweets made by @Hopewell Chin’ono on the 9th of June 2020 as illustrated below:

… . There is Jaji based in Namibia which is run by someone who many claims to be an associate of the Mnangagwa, MORE SHOCKING REVELATIONS backed up by documents. #ObadiahMoyo Mustgo …

@Hopewell Chin’ono goes further to tweet that Jaji was shut down yet the company continued to receive payments from the government of Zimbabwe as shown below,

… I can AUTHORITATIVELY say that this bank account on Jaji invoices didn’t BELONG to Jaji. It was shut down last year yet it was used for a 2020 invoice! Where was this money paid @GGuvamatanga The Namibians have said it was never wired to this bank account #ObadiahMoyo Mustgo …

The data and proof produced by @Hopewell can anger people and in this respect, social media, particularly Twitter, as aligned with this study, is an enabler of offline political activism. If used well, Twitter can lead to exposure of some truths and accuracy in society, which results in citizens engaging in action. Social media is usually seen as peddling rumours, falsehoods that have stopped people from participating in collective offline efforts such as demos. However, in this study, Hopewell exposes corruption in the procurement of COVID-19 drugs and protective equipment. This was a life and death scenario posed by the deadly COVID-19 virus, yet if someone is looting, this results in public anger and possible action from the people; hence, social media can indeed act as an enabler of poetical offline activism. Digital activism is successful in influencing the firing of errant government officials. @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume advocated for the dismissal of Health Minister, Dr. Obadiah Moyo. The successes of the Arab Spring revolutions were due to social media platforms mobilization. One notable strength of social media is that it is a unifying factor, that is; politicians, churches, and ordinary citizens coalesce around it.

@Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono successfully organised the 31st demonstrations, and its failure is not due to them, but that the government locked down Harare CBD from the 29th of July, that is, 2 days before the demo and restricted movement of people from residential areas. The demonstrations did not succeed, but not because social media failed as a push factor, but because of heavily armed police and army presence on the streets of Harare and also because of the arrest and detention of Hopewell and Ngarivhume days before July 31st. Therefore, Mugari and Cheng (Citation2020) note that social media poses a serious national security threat, citing the 1 August 2018 demo and eventual shooting as caused by social media, which publicised the July 31 elections 2018 before the national electoral body, ZEC, did so; which is offline activism.

8. The link between digital political activism and E-democracy

There is an intimate relationship between digital democracy and digital activism. There is a general sense that increased access to digital information technology is good for democracy in Africa and other developing regions (Bailard, Citation2012; Bailard & Livingston, Citation2014). Twitter brings about political advocacy and lobbying, and e-democracy encourages citizens to engage and be involved in public debates and decision-making (see screenshot below). Twitter has created a platform for democratic participation. Ngarivhume refers to citizens regaining their “voice”..

Twitter is a platform where agendas are created and influenced. The owners of Twitter seem to support the ongoing government attacks by netizens worldwide. In some parts of the world, social media platforms have been used as powerful communication tools for fuelling social and political upheaval. Through social media platforms, activists can overcome censorship, coordinate protests, and spread rumour with ease in instances where regimes stifle dissent and try to control public discourse (Tufekci, Citation2017). @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono are influential opinion leaders both on social media platforms and offline platforms. the 31st July demonstrations rested on the socio-economic ideologies created by @Jacob Ngarivhume and @Hopewell Chin’ono. @Hopewell Chin’ono tweets (see screenshot below).

E-democracy is being used by increasing numbers of people to network with other individuals to support social accountability across governments and politics. Accordingly, @Jacob Ngarivhume tweets:

… on the 31st of July I am not just pushing for the resignation of Obadiah Moyo but the entire ZANU PF government for the past and present crimes. These people need to be behind bars instead of behind a desk hiding from justice …

Twitter became the hub of information regarding the COVID gate scandal. An offshore company, known as Drax International, was used to loot COVID-19 Funds. Drax international is owned by President Emmerson Mnangagwa sons as tweeted by @Hopewell Chin’ono that Drax was a family business that he views as “Drax and Sons”

@Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume utilise digital activism as a means to advocate for and lobby political change and social injustice before 31st July demonstrations from the screenshots below, @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume are lobbying for change within the government that does not seem to acknowledge desires of the people. In essence, the study found out that a politician (@Jacob Ngarivhume) and a journalist (@Hopewell Chin’ono) unify for a socio-political cause.

Twitter has afforded people with seats to discuss political issues leading to the empowerment of citizens. The growing field of digital democracy is seen as a fringe revealing its potential to address this crisis. This is evident from the tweet made by @Hopewell Chin’ono:

Findings of this study demonstrate that digital democracy has the potential to refresh, deepen and question democratic practices and systems of governance.

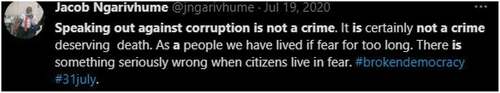

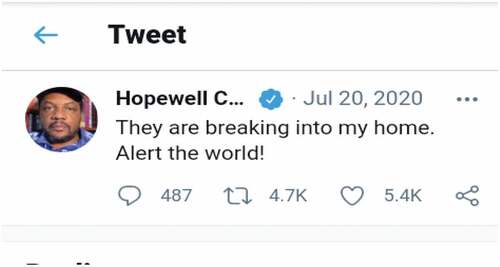

9. Twitter used to safeguard the lives of activists

Besides fighting for the freedom of citizens, another dimension of digital activism is safeguarding the lives of the activists themselves. Pro-democracy activist Itai Dzamara was abducted on 9 March 2015 and never seen again. However, when @Hopewell Chin’ono’s house was being broken into by state security agents, Hopewell sends out an SOS alert via Twitter (see screenshot below). Even Hopewell’s lawyer, Beatrice Mtetwa, rushed to the scene which meant Hopewell would be arrested lawfully by the police, not abducted.

This study found that @Hopewell Chin’ono was arrested by the police before the 31st of July. Findings obtained demonstrate that @namataik, a young female political activist, was arrested by the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP). @Hopewell Chin’ono tweets:

they have arrested @namataik again. She is at the central police station in Harare. RETWEET for her safety!!! …

Political activism in Zimbabwe has been regarded as a chargeable offense. The “Second Republic” re-inherited the suppression and oppression of individuals speaking against the government from the Mugabe era, who also inherited it from the Ian Smith (pre-independence) era. However, it is interesting to note that Chin’ono was abducted, not arrested, his action of tweeting about the security forces breaking into his house alerts the people, and the abductors will know that they are being watched, consequently reducing instances of torture and/or abductions, thus social media also safeguards the lives of the activists.

As noted by Mungwari (2017), social media equipped people with the truth so much that it was no longer easy and possible to spin and do a propaganda job on any incident. The Mnangagwa administration arrested @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume on charges of inciting violence. As a result, digital activism is a cause for concern to the government of Zimbabwe as it cannot control social media like the mainstream media. This is illustrated in the screenshot of a tweet made by @Jacob Ngarivhume:

Ngarivhume even invokes religion, urging netizens to pray so that God would keep them safe from government brutality.

… To #31july supporters as the big day draws near we cannot predict the state’s action. … Also pray for activists being arrested and let your voices be heard. God bless …

This shows that Twitter is used to encourage citizens to persevere in the face of state brutality.

10. Religious discourses as political activism

The researchers observed that religious discourses were used by both Ngarivhume and Chin’ono as they drummed up support for the demonstrations. Both refer to the Biblical 40 years since 2020 it was 40 years after Zimbabwe’s independence. The duo is implying that freedom is as guaranteed as happened with the Israelites, who were allowed into Canaan after 40 years in the desert. Hopewell tweets:

… 40 years after independence; being beaten for speaking against corruption isn’t freedom. Weaponising the police and army for political gain isn’t freedom. Having a government full of corrupt people isn’t freedom. People dying of hunger and disease isn’t freedom …

As the tweet above shows, @Hopewell Chin’ono is taking stock of freedom afforded Zimbabweans 40 years after independence and concludes that there is no freedom. Similarly,

@Jacob Ngarivhume ’s tweet is another stocktake:

Ngarivhume also encourages the Zimbabweans to pray to have spiritual guidance for the success of the 31st demonstrations. He tweets: “pray for activists being arrested and let your voices be heard. God bless”. This indicates that Jacob Ngarivhume is calling for divine intervention for the demonstrations to succeed without the loss of lives.

The use of religious discourses to gain political mileage is common among politicians. The politicians hide behind biblical quotes and contexts to justify political motives. The use of religious discourses was prevalent even during the 2018 harmonised elections. This was meant for political parties and their policies to appear as if they were ordained by God, and therefore cannot be questioned. ED had the slogan “The voice of the people is the voice of God” while Chamisa had the hashtag #GodIsInIt. Similarly, @Jacob Ngarivhume hopes also to invoke religion so that July 31st appears God-ordained and inevitable. @Jacob Ngarivhume alludes to the fact that apart from activism, prayer is a powerful weapon to fight against government oppression. Consequently, Ngarivhume also refers to God as a means to justify and make Zimbabweans feel the demo is the will of God. Ironically, it is religious discourse coming from a politician! This raises questions about the way politicians seek biblical alliterations of justification. On the 1st of July 2020, @Jacob Ngarivhume tweets,

On the 31st of July by the Grace of God, we will break off the chains of fear and speak boldly for the changes we want to see in Zimbabwe …

From the tweet above, the success of democracy and activism in Zimbabwe centres on divine intervention. As such, activists leading the 31st demonstrations are likened to Moses and Joshua who led the Israelites to from Egypt to Israel. The use of metaphors in the tweet, for instance, “we will break off the chains of fear” demonstrates that Zimbabwe is being governed by “slave masters” who must be overthrown, by the “Grace of God”. Ngarivhume even capitalises the letter “G” in “Grace” to appeal to Christians. Zimbabwe is largely recognised as a Christian country, hence Ngarivhume was trying to tap into this Christian population. Several notable Christian organisations have been seen to advocate for political change. To mention just but a few, organisations such as The Zimbabwe Council of Churches, The Catholics Bishops’ Conference, the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP), and the Church and Civil Society Forum, among others, have been very vocal in criticising government brutality.

11. Conclusion

Social media has morphed into a preferred medium of communication. Using the case of @Hopewell Chin’ono and @Jacob Ngarivhume before the 31st July demonstrations in Zimbabwe, this article complements digital democracy and political activism in Zimbabwe (Chibuwe, Citation2020; Chibuwe & Ureke, Citation2016; C. Moyo, Citation2019; Mungwari & Ndhlebe, Citation2019). The article demonstrates various forms that digital activism takes, and its ability to inspire collective offline activities in the “Second Republic”. Zimbabwe has been experiencing socio-economic and political challenges leading to an influx of human rights abuse, rampant corruption, and a flawed justice system. The 31st demonstrations sought to correct such ills within the government. Social media continues to flourish as a counter to a hegemonic sphere lampooning Emmerson Mnangagwa’s administration. Most of the protests experienced in Zimbabwe and globally are initiated in cyberspace. The internet and social media emerge to be useful tools to promote online participatory behaviour, facilitate and mobilize offline protest. As argued by Fraser (Citation1992) social media continues to give a voice and spaces to counter publics to deliberate socio-political issues, Twitter as a haven is an enabler of social action and change through mass protest mobilization.

Though regimes put measures in place to suppress dissent both on and off-line, Twitter remains weaponised by ordinary people as a way to seize power from repressive regimes. Hashtags are ubiquitous in the analysed tweets. The hashtag activism unified netizens and develop awareness for a cause in a networked society. Social media influences the communication matrix. Based on the relationship between digital democracy and digital political activism in the “Second Republic”, this study shows how that social media assumes the “dissidence” dimension as digital activists organise and mobilise citizens to overthrow the government in Zimbabwe. Twitter is a political progress medium in the “Second Republic” for political discussion, engagement, and interaction among the citizens thus it has created a political home where the people or netizens from different backgrounds equally engage in debates. E-democracy has emerged as a new form of political advocacy and lobbying. Religious discourses remain central to the configurations of Zimbabwean political activism. Ngarivhume and Chin’ono invoke religious discourses to “ordain” the 31st July demonstrations. Twitter is used to safeguard the lives of the activists themselves. In as much as this study is a welcome intervention to digital democracy and political activism in Zimbabwe, more research is required in the area of digital democracy.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Payidamoyo Nyoka

Payidamoyo Nyoka is a holder of MSc Media and Society Studies from Midlands State University, Zimbabwe. His teaching and research interests focus on Citizen journalism (Africa) Critical theory, Decolonial and post-colonial studies, Photography and film studies, Genocides, and Audience reception studies.

Mary Tembo is a holder of a BSc Media and Society Studies from Midlands State University, Zimbabwe. Her research interests focus on Digital media, Journalism, Corporate Communication, and Audience reception studies.

References

- Ahmed, S., Jaidka, K., & Cho, J. (2016). Tweeting India’s Nirbhaya protest: A study of emotional dynamics in an online social movement. Social Movement Studies, 161, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2016.1192457

- Atton, C. (2003). What is ‘alternative’ journalism? Journalism. Theory, Practice and Criticism, 4(3), 267–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849030043001

- Bailard, C. S., and Livingstone, S. (2014) Crowdsourcing accountability in a Nigerian election. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 11(4), 349–367

- Bailard, C. S., and Livingstone, S. (2012). A field experiment on the Internet’s effect in an African election: Savvier citizens, disaffected voters, or both? Journal of Communication, 62(2), 330–344.

- Brady, H.et al (1999). Political participation. In: Robinson J. P., Shaver P. R., and Wrightsman L. S. (eds.), Measures of Political Attitudes (pp. 737–801). San Diego: Academic Press.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, V. (2015). Theorizing citizenship in citizen journalism. Digital Journalism, 3(5), 704–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.937150

- Cantijoch, M., Cutts, D., and Gibson, R. (2016). Moving slowly up the ladder of political engagement: A “spill-over” model of internet participation. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(1), 26–48.

- Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International Journal of Communication, 1(1), 238–266.

- Castells, M. (2009). Communication Power. Oxford University Press.

- Castells, M. (2011). A network theory of power. International Journal of Communication, 5(2011), 773–787.

- Chatora, A. (2012). Encouraging political participation in Africa: The potential of social media platforms. Institute for Security Studies Situation Report. Accessed 21 September 2021. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/encouraging-political-participation-in-africa-thepotential-of-social-media-platforms/

- Chibuwe, A., & Ureke, O. (2016). ‘Political gladiators’ on Facebook in Zimbabwe: A discursive analysis of intra–Zimbabwe African National Union–PF cyber wars; Baba Jukwa versus Amai Jukwa. Media, Culture and Society, 38(8), 1247–1260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716671492

- Chibuwe, A. (2020). Social media and elections in Zimbabwe: Twitter War between Pro-ZANU-PF and Pro-MDC-A Netizens. Communication, 46(4), 7–30 https://doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2020.1723663.

- Chiluwa, I. (2012). Social media networks and the discourse of resistance: A sociolinguistic CDA of Biafra online discourses. Discourse and Society, 23(3), 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926511433478

- Chitanana, T., & Mutsvairo, B. (2019). The Deferred ‘Democracy Dividend’ of Citizen Journalism and Social Media: Perils, Promises and Prospects from the Zimbabwean Experience. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 14(1), 66–80. https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.305

- Chitanana, T. (2020). From Kubatana to #ThisFlag: Trajectories of digital activism in Zimbabwe. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 17(2), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2019.1710644

- Chiumbu, S. (2015). Social movements, media practices and radical democracy in South Africa. French Journal for Media Research, 4(2015), 1–20, .

- Christensen, C. (2009). Iran: Networked dissent. Le Monde Diplomatique.

- Christensen, C. (2011). Twitter revolutions? Addressing social media and dissent. The Communication Review, 14(3), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714421.2011.597235

- Dahlgren, P. (2005). The internet, public spheres, and political communication: Dispersion and deliberation. Political Communication, 22(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600590933160

- Dahlgren, P. (2009). Media and political engagement: Citizens, communication, and democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Dendere, C. (2019). Tweeting to democracy: A new anti-authoritarian liberation struggle in Zimbabwe. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos, 38(38), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.4000/cea.4507

- Dennis, J. (2019). Operationalising the continuum of participation . In Beyond Slacktivism. Interest groups, advocacy and democracy series. Palgrave Macmillan https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00844-4_3.

- Dennis, J. (2018). Beyond Slacktivism: Political Participation on Social Media. Springer.

- Elyachar, J., & Winegar, J. (2012). Revolution and counter-revolution in Egypt a year after January 25th. Hot spots. Cultural Anthropology Accessed 25 June 2021 http://www.culanth.org/fieldsights/208-revolution-and-counter-revolution-in-egypt-a-year-after-january-25th.

- Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text, 25(26), 56–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/466240

- Fraser, N. (1992). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 109–142). The MIT Press.

- Fuchs, C. (2009). Some reflections on Manuel Castells’ book ‘Communication Power’. Triple C, 7(1), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v7i1.136

- Gallagher, J. (2015). The battle for Zimbabwe in 2013: From polarisation to ambivalence. Journal of Modern African Studies, 53(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X14000640

- Gibson, R., and Cantijoch, M. (2013). Conceptualizing and measuring participation in the age of the internet: Is online political engagement really different to offline? The Journal of Politics 75(3), 701–716.

- Gibson, A., Lewando Hundt, G., & Blaxter, L. (2011). Weak and strong publics: Drawing on Nancy Fraser to explore parental participation in neonatal networks. Health expectations. Political Participation, 17(1), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00735.x

- Grossman, F. D. (2010). Dissent from within: How educational insiders use protest to create policy change. Educational Policy, 24(4), 655–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904809335110

- Gukurume, G. (2017). #ThisFlag and #ThisGown Cyber Protests in Zimbabwe: Reclaiming political space. African Journalism Studies, 38(2), 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2017.1354052

- Gukurume, S. (2019). Surveillance, spying and disciplining the university: Deployment of state security agents on campus in Zimbabwe. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 54(5), 763–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909619833414

- Habermas, J. (1962/1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An inquiry into a category of a Bourgeois Society, trans. T. Burger and F. Lawrence. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press.

- Hauben, M., & Hauben, R. (1997). Netizens: On the history and impact of usenet and the internet. Wiley, The University of Michigan.

- Holston, J. (2008). Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil In-formation series. Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691130213, 9780691130217

- Knoll, J., Matthes, J., & Heiss, R. (2020). The social media political participation model: A goal systems theory perspective. Convergence. The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(1), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517750366

- Kozinets, R. V. (2006). Click to connect: Netnography and tribal advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(3), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060338

- Kozinets, R. V. (2015). Netnography. redefined. Sage.

- Langmia, K., & Glass, A. (2014). Coping with smart phone ‘Distractions’ in a college classroom. Teaching Journalism and Mass Communication, 4(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-5-5-14

- Liaropoulos, A. (2013). The challenges of social media intelligence for the intelligence community. Journal of Mediterranean and Balkan Intelligence, 1(1), 5–14.

- Mabweazara, H. M. (2011). The internet in the print newsroom: Trends, practices and emerging cultures in Zimbabwe. In D. Domingo & C. Paterson (Eds.), Making online news: Newsroom ethnographies in the second decade of internet journalism (pp. 57–69). Peter Lang.

- Mabweazara, H., M. (2020). Towards reimagining the ‘digital divide’: impediments and circumnavigation practices in the appropriation of the mobile phone by African journalists”. Information, Communication & Society, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1834602

- Madenga, F. (2021). From transparency to opacity: Storytelling in Zimbabwe under state surveillance and the internet shutdown. Information, Communication and Society, 24(3), 400–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1836248

- Mandikwaza, E. (2013). Social Media and Democracy: A study on the role of social media in Supporting political dissent and political participation. The case of Tunisia and Egypt [ Unpublished MSc Thesis]. University of Reading.

- Mare, A. (2018). Politics unusual? Facebook and political campaigning during the 2013 harmonised elections in Zimbabwe. African Journalism Studies, 39(1), 90–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2018.1425150

- Mare, A. (2016). Baba Jukwa and the digital repertoires of connective action in a ‘Competitive Authoritarian Regime’: The case of Zimbabwe. In B. Mutsvairo (Ed.), Digital activism in social media era: Critical reflections on emerging trends in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 45–68). Palgrave MacMillan.

- Margetts H, John P, Hale S, et al. (2015). Political Turbulence: How Social Media Shape Collective Action. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mathuthu, M. (2014). The Jukwas: asThe Jukwas: ashort history by Mduduzi Mathuthu. Nehanda Radiohort history by Mduduzi Mathuthu. Nehanda Radio. Nehanda Radio. Retrieved June 122021, from http://nehandaradio.com/2014/06/23/jukwas-short-history-mduduzi-mathuthu

- Matingwina, S. (2018). Social media communicative action and the interplay with national security: The case of Facebook and political participation in Zimbabwe. African Journalism Studies, 39(1), 48–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2018.1463276

- Matthes, J., Nanz, A., Stubenvoll, M., & Heiss, R. (2020). Processing news on social media. The political incidental news exposure model (PINE). Journalism, 21(8), 1031–1048. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920915371

- McLoughlin, L., & Southern, R. (2021). By any memes necessary? Small political acts, incidental exposure and memes during the 2017 UK general election. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 23(1), 60–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120930594

- McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. McGraw-Hill.

- Mhiripiri, N. A., & Mutsvairo, B. (2013). Social media, new ICTs and the challenges facing the Zimbabwe democratic process. In A. A. Olorunnisola & A. Douai (Eds.), New media influence on social and political change in Africa (pp. 402–422). IGI Global.

- Mhlanga, B., & Mpofu, M. (2014). The Virtual Parallax: Imaginations of Mthwakazi Nationalism Online Discussions and Calls for Self-Determination. In A. M. G. Solo (Ed.), Handbook on research on political activism in the information age (pp. 129–146). IGI Global.

- Moretzsohn, S. (2006). Citizen journalism and the myth of redemptive technology. Brazilian Journalism Research, 2(2), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.25200/BJR.v2n2.2006.81

- Mossberger, K., Tolbert, C. J., & Stansbury, M. (2003). Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Moyo, C. (2019). Social media, civil resistance, the Varakashi factor and the shifting polemics of Zimbabwe’s social media war. Global Media, Journal, African Edition, 12 (1) 1–36. hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1d7a935bf8.

- Moyo, D. (2009). Citizen Journalism and the parallel market of information in Zimbabwe’s 2008 election. Journalism Studies, 10(4), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700902797291

- Moyo, L. (2009). Constructing a home away from home: The internet, Nostalgia and identity politics among Zimbabwean Communities in Britain. Journal of Global Mass Communications, 11(1/2), 66–85.

- Moyo, L. (2011). Blogging down a dictatorship: Human Rights, Citizen Journalists and the right to communicate in Zimbabwe. Journalism, 12(6), 745–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911405469

- Mpofu, S. (2013). Social media and the politics of ethnicity in Zimbabwe. Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies, 34(1), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560054.2013.767432

- Mpofu, S. (2015). When the subaltern speaks: Citizen journalism and genocide ‘victims” voices online. African Journalism Studies, 36(4), 82–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2015.1119491

- Mugari, I., & Cheng, K. (2020). The dark side of social media in Zimbabwe: Unpacking the legal framework conundrum. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1825058. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1825058

- Mukhongo, L. (2014). Negotiating the new media platforms: Youth and political images in Kenya. Triple C: Communication, capitalism and critique. Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 12(1), 328–341.

- Mungwari, T., & Ndhlebe, A. (2019). Social media and political narratives: A case of Zimbabwe. Sociology International Journal, 3(3), 277‒287. https://doi.org/10.15406/sij.2019.03.00187

- Mutsvairo, B., & Columbus, S. (2012). Emerging patterns and trends in citizen journalism in Africa: The case of Zimbabwe. Central European Journal of Communication, 5(2), 121–135. http://ptks.pl/cejc/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/CEJC_Vol5_Vol5_No1_Mutsvairo.pdf.

- Mutsvairo, B., & Sirks, L. A. (2015). Examining the contribution of social media in reinforcing political participation in Zimbabwe. Journal of African Media Studies, 7(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1386/jams.7.3.329_1

- Mutsvairo, B. (2013). Are new media technologies positively influencing democratic participation? Evidence from the 2008 elections in Zimbabwe. Global Media Journal African Edition, 7(2), 181–200.

- Mutsvairo, B. (2016). Dovetailing desires for democracy with new ICTs’ potentiality as platform for activism. In B. Mutsvairo Digital Activism in the Social Media Era: Critical Reflections on Emerging Trends in Sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 3–25). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mwareya, R. (2019). Meet ‘Varakashi’- Zimbabwe’s Online Army. iAfrikan.

- Ncube, L. (2019). Digital Media, Fake News and Pro-Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) Alliance Cyber-Propaganda during the 2018 Zimbabwe Election. African Journalism Studies, 40(4), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2019.1670225

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni S.J. (2015) Introduction: Mugabeism and Entanglements of History, Politics, and Power in the Making of Zimbabwe. In: Ndlovu-Gatsheni S. J. (eds) Mugabeism?. African Histories and Modernities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137543462_1

- Papacharissi, Z. (2014). Affective publics sentiment, technology and politics. Oxford University Press.

- Pattie, C., Seyd, P., & Whiteley, P. (2004). Citizenship in Britain: Values, participation and democracy. Cambridge University Press.