Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has impacted the world with devastating socio-economic effects and the global tourism sector has been severely affected by it. A number of current studies have examined the size and form of these negative impacts on tourism but to date, there is lack of research exploring possible positive effects of the pandemic, especially in tourism. This study fills this gap as the purpose of this research is to understand how the pandemic has stimulated the development of virtual tourism and how this new form of tourism is performing. Moreover, this study aims to better understand the roles that structure and agency play in stimulating the emergence of virtual tourism. The study is largely qualitative in nature, using in-depth interviews and participant observation as methods of data collection. The study shows that the pandemic has stimulated technological innovation and the re-conceptualization of leisure-seeking behavior, resulting in the emergence of an Indonesian virtual tourism industry. Virtual tours are offered online, mostly via Zoom, where tourism images are displayed via Google Maps/Earth, photos, or short videos. By using structuration theory, this study shows that the pandemic, a single structure, plays a dual constraining/enabling role that has accelerated the emergence of virtual tourism. These dual roles are performed simultaneously; constraining traditional tourism forms and enabling new virtual forms. More specifically, these findings suggest that structures and agencies/actors represent dualism, as opposed to duality. This study shows that the structure (rules and resources) plays a dominant role in driving actors to innovate, triggering the emergence of virtual tourism.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The Covid-19 pandemic has rocked the world with devastating socio-economic effects, and the global tourism sector has been severely affected by it. Studies show the size and form of these negative impacts on tourism. Still, it appears that the pandemic has stimulated innovation within Indonesian tourism businesses with the emergence of virtual tourism. This study aims at understanding of how pandemic Covid-19 plays a double role: constraining the practice of the “conventional tourism” but at the same time promoting the emergence of a new type of tourism, namely virtual tourism. This article is suitable and interesting for a wide public interest. The topic is about a new type of tourism that emergence due to the Covid-19 pandemics. It, among others, describes narratively how the virtual tourism is conducted. The article is also supplied with pictures to make it more interesting and easy to follow.

1. Introduction

Tourism is one of the most important sectors for socio-economic development in many countries. Its contribution to the economy of a country is reflected directly in the amount of foreign exchange earnings and also the opportunities it brings for generating community and regional revenue, job creation, investment and business development (Lee, Citation2008; Jaafar & Maideen, Citation2012; Jaffe & Pasternak, Citation2004; Jayathilake, Citation2013; Scheyvens & Momsen, Citation2008; Vogt et al., Citation2020; WTTC, Citation2019). A study by Seghir et al. (Citation2015) shows that in the 49 countries that implement the Tourism-Lead Growth (TLG) development policy, there is a positive correlation between tourism growth and economic growth. This positive correlation has been experienced in most of the top tourism destination countries, namely China, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Russia, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Shahzad et al., Citation2017). Thus, the tourism industry has become a strategic sector for national development for many countries, including Indonesia.

Indonesia is well-endowed with natural and cultural diversity and this has long attracted international tourists. The Indonesian archipelago has more than 17,000 Islands, more than 300 ethnic groups, 51 national parks, with many of them recognized as World Heritage sites ([LPEM UI] Lembaga Penyelidikan Ekonomi dan Masyarakat Universitas Indonesia, Citation2018). Indeed, tourism has been a critical part of the country’s economic growth, and with improved international transportation and improved access as tourism destinations, the sector has expanded rapidly (Hampton & Jeyacheya, Citation2015; Kinseng et al., Citation2018). In 2018, the country’s tourism growth ranked 9th fastest in the world (WTTC, 2019). Based on data from the Ministry of Tourism (Kemenpar), the sector’s contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 was 4.8 per cent—an increase of 0.3 points compared to 2018. This increasing tourism contribution to GDP has typically been driven by rising numbers of foreign tourists, with higher levels of investment in the industry ([Kemenpar] Kementerian Pariwisata Republik Indonesia, Citation2019). Foreign exchange earnings by this sector increased from US$13.139 billion in 2017 to US$16.426 billion in 2018 ([BPS] Badan Pusat Statistik, Citation2019). However, this significant growth suddenly crashed in 2020 because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In Indonesia, the first detected case of Covid-19 was announced by the President on 2 March 2020, and on 13 April 2020 the President declared the Covid-19 pandemic a national disaster. By 16 July 2020, there were 81,668 people infected by the virus and 3,873 people died of it. The virus has indiscriminately affected the socio-economic life around the globe. In reviewing its impact, Hanafi (Citation2020) emphasizes that “the current disruption will change, at an unprecedented rate, how we eat, work, shop, exercise, manage our health, socialize, and spend our free time.” The pandemic “shakes the world” (Zizek, Citation2020) and may be “the greatest disruption in the 21st century” (R.A. Kinseng, Citation2020). Several studies have analyzed the wide-reaching negative impacts of the pandemic, such as on higher education systems (Suwignyo & Agus Purwanto, Citation2020), the global economy (Liu et al., Citation2020), and on social solidarity (Kustiningsih & Nurhadi, Citation2020; Supriyati, Citation2020). Specifically, Yang et al. (Citation2020) and Li et al. (Citation2020) show the negative impacts the pandemic has had on tourism, including declining health and welfare, the disruption of planned travel behavior and the importance of a government’s active role in tourism recovery (Fong et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Chen et al. (Citation2020, p. 3) stated that “COVID-19 has devastated China’s current socio-economic tourism system”. Meanwhile, Bae and Chang (Citation2020) have studied “a new behavioural pattern among tourists” in South Korea during the pandemic Covid-19.

In Indonesia, official statistics show that the number of foreign tourists who entered the country in December 2019 was 1,377,067. Then, within a few months, it had plummeted to 160,042 in April 2020 ([BPS] Badan Pusat Statistik, Citation2020). However, no detailed studies have examined any potential positive impacts the pandemic has had on tourism, namely the emergence of virtual tourism. This study aims to fill this gap and the purpose of this research is to uncover and understand any positive effects the pandemic has had on the tourism industry in Indonesia. Specifically, this study examines how the pandemic has stimulated the development of virtual tourism and assess how this new form of tourism is performing. Giddens’ lenses of structuration theory have been applied to the analysis of this new phenomenon.

By relying on the theoretical foundation of structuration theory, although this is largely exploratory research, we suspect (weakly hypothesize) that the key drivers to the emergence of virtual tourism in Indonesia are indeed structural factors, encompassing both rules and resources. In the case of this pandemic, rules and regulations have been established by the government and other institutions to stop the spread of Covid-19. These restrictions, or “material structures”, such as curfews, travel limitations, group maxima, and limited face-to-face encounters as well as non-restrictive changes like increased reliance on the internet, connected devices, and technological alternatives to face-to-face interaction. In other words, the actors who have spearheaded virtual tourism have largely moved in that direction because the structural factors have both limited traditional pathways and provided avenues towards innovative solutions.

1.1. Theoretical framework

We see that the emergence of virtual tourism is an outcome of actions taken by social actors—the tour hosts/guides/organizers. The application of social action theory—a central argument in sociology, specifically in the creation and reproduction of social systems—fits well to understand the relationship between the pandemic and the emergence of virtual tourism in Indonesia. A longstanding debate exists between those who have view an individual actor as completely independent, who can make choices based on their calculations and values, and those who hold the view that an actor’s action is determined by social structures within the actor’s social systems. For example, in his classical works, “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism”, Max Weber shows that the Protestants acted rationally, based on their ethics derived from Calvinism (Weber, Citation1930/1992). In contemporary sociological theories, Symbolic Interactionism, Phenomenology, and Rational Choice, all emphasize the autonomy of the individual in their actions. On the other side, theories such as Structural Functionalism and Marxism argue that human actions are determined by social structures.

In his Structuration theory, Giddens argues that this dualism of structure versus agency is a false dualism (Giddens, Citation1984; Sibeon, Citation2004). He reasons that agency and structures should be regarded as duality; they are like two sides of the same coin. Every action is considered as an interplay between agency and structure. While rejecting Giddens idea of duality of agency and structure, R. A. Kinseng (Citation2017) suggests the term “Structugency” to underscore that every action is influenced by two elements: agency and structures. He agrees with those who argue, at the conceptual and analytical level, that agency and structures must be treated as separate and different entities (Archer, Citation1982; Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; Mouzelis, Citation2008; Sibeon, Citation2004). An actor’s particular action can be determined by agency, by structures, or by degrees of both. The interplay between agency and structures in an actor’s action is presented in .

Figure 1. The interplay between agency and structure in an actor’s action (source: R. A. Kinseng, Citation2017).

Giddens further explains the two components that make a structure: rules and resources (Giddens, Citation1984). Rules are norms that govern social practices, while resources consist of two types that generate power, namely authoritative and allocative. Authoritative resources are non-material resources while allocative resources are material resources, including the natural environment and physical artifacts.

Meanwhile, Sibeon provides a broader definition of structures as: “temporally enduring or temporally and spatially extensive social conditions that to a greater or lesser extent influence actors’ forms of thought, decisions and actions. Depending on the circumstances, these facilitate or constrain an actor’s capacity to achieve their objectives” (Sibeon, Citation2004, pp. 53–54). More specifically, this social structure consists of: “discourses; institutions social practices; individual and social actors; social systems or networks; and power distributions” (Sibeon, Citation2004, p. 54). In the current study, the definition of structure according to Giddens and the social structure submitted by Sibeon, have been followed, in order to better understand the actions taken by social actors who have introduced virtual tourism attractions. Further, we focus on how, following these definitions, the structures can be constraining, but also enabling social practice and the actions of actors.

1.2. Methodology

The data collection phase of the study was conducted from June to July 2020. Due to the novelty of the issues being examined, namely to better understand the processes and emergence of virtual tourism, the problem was examined qualitatively in an exploratory manner (Babbie, Citation2016, p. 19) Data was collected both through in-depth interviews with tour operators and through participant observation by the research team while experiencing virtual tours conducted by the participating tour operators. This approach is in line with Marshall and Rossman’s view that,

“The fundamental techniques relied on by qualitative researchers for gathering information are (1) observation and (2) in-depth interviewing. These two techniques form the core, the staple of the diet” (Marshall & Rossman, Citation1989, p. 79). The respondents, namely those who are actively conducting virtual tourism in Indonesia, were chosen purposively by using the snowballing method. The first respondent, Ira Lathief, was chosen after she was interviewed about virtual tourism on a popular program on national television. She provided valuable information to the researchers about tourism organizations that are active in virtual tourism.

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were held with six respondents from five tour guide organizations: Jakarta Good Guide (JGG), Wisata Kreatif Jakarta (Creative Tour Jakarta or WKJ), Atourin, Bersukaria and Telusuri. One respondent (founder or co-founder) from each organization were interviewed, except for Telusuri, who had two respondents.

Each interview with respondents was conducted online via Zoom, using an interview guide to ensure consistency across all interviews. The main purpose of the interviews was to document the specific timing, the salient situational factors, critical information, organizational capabilities, and any other influences surrounding their decision to embark on the development and delivery of virtual tourism offerings.

“Field observations” were conducted by research team members who joined a tour organized and led by each of the four tour organizations. The research team participated in two tours organized by Telusuri. The main purpose of the field observations were to document the process from the participant’s point of view, from interactions prior to the tour (advertising, communication, registration, instructions) as well as aspects of the tour itself. Of particular importance was the contribution of the tour guide and the use of various technologies to make the experience more “real”.

Secondary data was obtained from Statistics Indonesia (Badan Pusat Statistik), the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism, and the Economic Research Institute of University of Indonesia (LPEM UI) to establish national trends and statistics that document the background and help highlight the importance of this research. Secondary data was also obtained from the participating tourism operators, especially narrative that explained the motivations and establishment of their virtual tours offerings and the tour brochures and advertising that contained information such as schedules, destinations, attractions, and fees.

Data were analyzed using the “Interactive Model” proposed by Huberman and Miles (Citation1994, p. 429), which consist of data collection, data reduction, data display, and conclusion (drawing/verifying) as presented in . This method also involved data interpretation and logical analysis as mentioned by Marshall and Rossman (Citation1989, p. 114). Furthermore, these data analyses involved identifying common themes such as the driving forces that caused the emergence of virtual tourism, the methods and objects of virtual tours, marketing strategies, pricing and payment systems, which form the basis for analyzing the potential of the emerging virtual tourism industry in Indonesia. To strengthen our description, we also present several pictures as visual data.

Figure 2. Components of data analysis: interactive model.Source: Huberman and Miles (Citation1994, p. 429).

Before Results and Discussion, we profile the tourism organizations from which we selected our respondents. This will give a better understanding of the respondents’ background and business activities before and after the Covid-19.

1.2.1. Creative tourism Jakarta

Creative Tourism Jakarta (Wisata Kreatif Jakarta, hereafter WKJ) provides organized tours that focus on a variety of creative tourism in Jakarta. The “community” was established in 2017 by Ira Lathief, herself a tour guide. Initially, it was called Jakarta Food Traveler and specialized in culinary tours. It then expanded to providing “creative” tour packages experiencing unique places and their histories in Jakarta. This expansion, and ultimately the establishment of WKJ came from the founder’s experience while guiding foreign tourists, many of whom wanted to know more about the city of Jakarta and its history, rather than simply its food culture. Lathief also observed that many of the residents of Jakarta also do not know much about the historical places in their city. The company also offers unique and creative tour packages such as culinary tours, fun tours for families, religious tours, and cemetery tours. In the context of structuration theory, it can be seen that actor’s agency plays a dominant role in the emergence and development of this new tourism business compare to the role of structures.

1.2.2. Jakarta good guide

Jakarta Good Guide (JGG) also operates as a community of tour guides that take tourists around Jakarta on walking tours. Its vision is to “make Jakarta a tourist-friendly city.” JGG believes that the city has not been a popular destination for tourists visiting Indonesia, and this belief encourages JGG to make visiting Jakarta a unique and memorable tourism experience by exploring the city closely on foot. JGG offerings introduce tourists Jakarta even if it means experiencing its crazy traffic.

JGG was founded in 2014 by Farid and co-founder Chanda Adwitiyo Harto. All the guides it employs are licensed, and to date, JGG has offered countless tours around Jakarta, with at least 28 routes. Recently, twelve more guides began working for JGG, showing tourists around Jakarta on virtual tours. In addition to being tour guides, some are also responsible for marketing, scheduling and planning routes, and administration and graphic design. Again, we can see that virtual tourism was developed by the creative thinking of the founders as a way to sustain their businesses.

1.2.3. Atourin

Atourin is a travel agent, officially established in December 2019 as a company engaged in providing tours. So far, it has focused only on serving domestic tourists within Indonesia.

Atourin could be regarded as one of Indonesia’s virtual tourism pioneers because in the early days of pandemic (March-April), it started conducting virtual tours designed to train its new tour guides. Currently, it conducts virtual tours 2–3 times a week, with 30 to 60 people participating on these virtual trips. Tour destinations are either determined by the company, the guides, or together through discussions. Atourin markets its services through its website, social media, and the news media.

1.2.4. Bersukaria

Bersukaria (literally means having a fun time) is a community-based tour organizer, established as a legal entity in 2016 in Semarang City, Central Java. It specializes in organizing historical and cultural tours. The group’s name itself is loaded with history, derives from the title of a popular song composed in 1965 by Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia. The word “Bersukaria” is also derived from the lyrics of the Gambang Semarang song, in which the word “Bersukaria” appears and thus reflect its cultural root.

Prior to Covid-19, Bersukaria offered two types of tourist experience—a city walking tour and a city car tour. Initially, it offered a walking tour once a month. With increased popularity, this moved to every Saturday or Sunday, at either 08.30 am or 15.30 pm, and each trip lasts about 2–3 hours. They can run tours on other days as well, so the weekly tour schedules are updated on its Instagram account to help prospective customers choose the route and the time of the tour.

When Covid-19 struck, the Bersukaria switched to virtual tourism as they found interest was high enough to start historical and cultural virtual tours. It is thought that the transition to virtual tours was possible because their tour guides have such an excellent reputation for storytelling, and their past customers have really enjoyed the experience.

1.2.5. Telusuri

Telusuri (literally means, “explore”) was founded in 2014. It started its tourist business by collaborating with Google Indonesia to offer walking tours in 10 Indonesian cities. It was initially formed by three people: Maureen Fitri (Semarang), M. Syukron (Kapoposang), and Yovita Ayu (Jakarta). It is now part of Tempo Group (a large media company), under the Rombak Media Group.

Telusuri, also known as “Telusuri school”, ‘Ayo Telusuri (Let’s explore) and Telusuri.id. The organization was formed because it wanted to raise awareness of tourism sites in Indonesia that people were not aware of and elevate local tourism. Its mission is to introduce and encourage local tourism and provide a high-quality experience with positive and beneficial outcomes. To this end, it uses its main media browser (Telusuri.id) and travel websites.

Telusuri’s tour activities are often held in collaboration with local communities to help promote local tourism and while sharing information and experiences with the local community. Telusuri also encourages people to write and share their travel experiences with others by publishing them on the Telusuri.id website.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Driving forces of the emergence of virtual tourism

Studies show that Covid-19 spreads through droplets and aerosols that occur when humans interact with each other (Heymann & Shindo, Citation2020; Shereen et al., Citation2020). “The human to the human spreading of the virus occurs due to close contact with an infected person, exposed to coughing, sneezing, respiratory droplets or aerosols” (Shereen et al., Citation2020, p. 92). Therefore, to break its chain of spreading, governments around the world, including Indonesia, have issued policies to regulate physical space between people for social distancing (minimum 1.5 meters).

To ensure this physical distance of social interaction, citizens have been banned from forming groups or clusters. Furthermore, governments have implemented work from home (WFH) policies and established quarantine conditions for people who have been travelling overseas. To enforce these policies, provincial and district governments have had to implement lockdown policies, banning the public from leaving the area, or even their houses. These lockdown policies have had broad consequences, in some cases stopping economic activity from production, trade, and public transportation. During lockdowns, most education was delivered online, and even religious services were conducted online.

Structuration theory posits that policies and regulations issued by the government and other institutions such as corporations, malls, and universities to break the spread of covid-19 are termed as rules (Giddens, Citation1984) or “institutional or normative structures” (Mouzelis, Citation2008, p. 111).

In most countries, tourism activities have ceased altogether due to policies applied to prevent the spread of Covid-19. Consequently, the tourism sector has suffered significant decline internationally (Fong et al., Citation2020). This reality is mirrored the tour guides in this study. WKJ’s informant underlined that “the decline in tourism was very severe.” She underlined that WKJ’s tour guides have had “no money for three months because of Covid-19”, that led them to feel “briefly hopeless.” The same experience was also conveyed by the JGG informant, who stated that, in the early days of the pandemic, for about two weeks in March, tourist activities completely stopped. There was “a two-week vacuum.” Similar comments were expressed by interviewees from Telusuri who emphasized how tourism was “heavily affected” or “hugely declined” while Bersukaria’s informant said that all their activities stopped during March. However, they did not despair at the effects of the pandemic. A representative of Atourin stated “we realized that if we are not holding up, our partners will be adversely affected too. So, we had to think about ways through which our company and our partners can survive, one of them is by creating virtual tours.”

Such a massive slump in tourism triggered the creation of virtual tours. The WKJ interviewee, for example, was inspired to carry out virtual tours following an activity about Kampung Tugu that it shared via Zoom session that drew about 50 tourists. After that session, the group launched its first virtual tour on 1 May 2020. Its goal was to continue its activities and generate income for the duration of the pandemic as no one knew when it would end. The pandemic also prompted JGG to offer virtual tours. The JGG interviewee explained that the idea to provide virtual tours started when a tourist asked him “why not try virtual tours?” After that, JGG conducted a trial in March 2020, and when it was successful, it started its virtual tours in April.

For Atourin, the pandemic was also the major driving factor for offering virtual tours. Johar reflected that before the health crisis, he never thought about doing a virtual tour and the idea emerged from a suggestion by one of the group’s founders who studied a postgraduate course in sustainable tourism and did a research project on designing a virtual journey. As Johar explained further, “starting with the Atourin founder’s personal experience, we all thought why not commercialize this and make this an economic alternative for the tourism partners.”

Telusuri also started to build a virtual tour in March. It’s informant (Maureen) shared that “initially we offered a school program as a learning space about travel, photography, and writing about travel and tourism in Indonesia. Because of Covid-19, we switched from the school program to a virtual tour”. The virtual tour program was built upon the historical and cultural richness of the chosen destinations in Indonesia. Then, the team searched for information about virtual tourism that could provide an income for local guides. The founder of Bersukaria also shared a similar comment, “before the pandemic, we did not think about a virtual tour”; however, he admitted the group “benefited” from this virtual tour because through the tour Bersukaria became better known.

As the above testimonies show, the tour guide companies never considered offering virtual tours before Covid-19. As Chandra admitted, “we had no idea about a virtual tour, so there was no preparation” to implement their virtual tour. Another interviewee from WKJ agreed that “we never thought about virtual tourism; it is beyond imagination; even in early April we gave virtual tour no thought”. When asked if this new virtual tourism started at the same time as the spread of Covid-19 began, a tour guide from JGG told to the research team who took a virtual tour of Barcelona on 28 June 2020, via chat, noting that: “Yes, right. We just started off the tour in early April because of Covid-19”. Johar of Atourin also said that “honestly, we would never have thought of doing virtual tours if it weren’t for the existence of this Covid-19.”

However, not all tour guides within the WKJ, JGG, Atourin, Telusuri and Bersukaria were willing to guide the virtual tours. In the recruitment of guides for the tours, Atourin assesses the guides based on their knowledge and capabilities. When several guides operate in a chosen destination, Atourin selected the guides first. However, when only one person was available, they were assessed for their readiness as a virtual tour guide. The informants emphasized that the determining factor for virtual tour guides was their access to a computer and a reliable internet network. Without these facilities, it was not possible to carry out quality virtual tours.

Meanwhile, from the point of view of human resources, all that is required is the guides’ desire to learn and adapt to the changing business environment. When asked about the requirements for being a virtual tour guide, Candra emphatically stated that “willingness to learn” is what matters most. The same is expressed by WKJ’s interviewee that “those who are willing to adapt, are those who will change.” Besides, the skills of using a computer and digital technology over the internet are also indispensable. Both informants acknowledged that there are members who could not become virtual tour guides because they are relatively old and cannot use a computer. Some have tried using this digital platform three times, but then decided not to continue. One of these guides commented that “talking to a computer is like a crazy man”.

Guides from Atourin and Telusuri faced similar challenges of limited technical ability to be able to guide a virtual tour. To overcome these barriers, Atourin and Telusuri provide operators who can assist their guides in operating the computer during a virtual tour. Another obstacle that Atourin encountered is to convince local guides “that their region is unique, so its story needs to be told through virtual trips.” Johar commented how it was even harder to convince a guide who did not feel confident and was fearful of not being able to answer questions and explain things in Zoom sessions.

2.2. Virtual tourism: Methods and objects

Virtual tourism actors such as WKJ, JGG, Atourin, Telusuri and Bersukaria operate their virtual tours through the Zoom platform. In addition to Zoom, Telusuri also uses Google Meet and Google for education. The tourists who join the tour first sign up online, then these tour operators send the Zoom link to the tourists who have registered. On a specified date and time, the tourists join the Zoom session to begin their tour. A tour “destination” is displayed using Google Earth. The attractions in the tour destination are displayed through photos or short videos. For example, the guide from Bersukaria showed a photo about the history and development of the railway in Java at the tour on Sunday 5 July 2020 (). WKJ conducts tours with a single tour guide, JGG runs tours with two guides, where one person guides the tour and the other acts as backup in case of technical problems, or to offer additional information and answer questions.

Somewhat different from those roles, guides from Atourin and Telusuri are in charge of guiding, while an operator shows tourism objects being “visited.” As in actual tours, tourists can ask questions and make comments at any time, either directly or through the chat function in Zoom. Virtual tourism has its advantages in that anyone from anywhere can join a tour, without the limitation of movement, space, or distance, and the time requirements are more flexible. However, the informants admitted that in terms of experience for tourists, a virtual tour is not as “real” as an actual one. For example, Dimas from Telusuri said that on a “real” trip, all the senses are engaged, while on a virtual tour, only sight and sound are involved. Moreover, informants from WKJ and Telusuri underlined that as the experience gained from a virtual tour “is very different”, and they have had to work harder to create the best visualization possible.

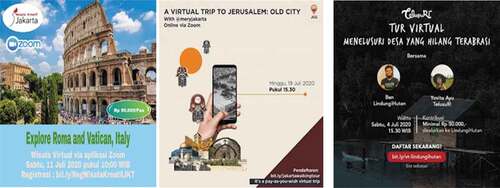

2.3. Marketing strategy

All virtual tour operators interviewed in this study use these common marketing strategies:

promotion through their websites and social media

determination of destinations

determination of virtual tour schedules

These marketing strategies are implemented through websites and social media, such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Through these platforms they provide information about destinations, schedules, and prices for virtual tours (). Each guide also helps conduct virtual travel promotions. For JGG and Bersukaria, marketing through Instagram is proving effective among their Instagram followers; JGG has more than 27,000 followers. Atourin uses paid advertising services on social media, and Telusuri conducts marketing via email.

The wide selection of virtual tourism destinations in Indonesia is the primary attraction for consumers to register. WKJ, JGG and Atourin continually update the destinations of their virtual tours, selecting the most popular destinations at any given time. WKJ’s informant commented that “with our promotion strategy that people can travel around Indonesia and the world virtually, this has proven to attract potential tourists”. According to informants from WKJ and JGG, most of their consumers choose foreign destinations. However, as Atourin only offers virtual tours for domestic destinations, it has local guides who specialize in several of their favourite regions of Indonesia. Additionally, the tours are scheduled three times a week instead of daily, to spread out tourist numbers. As for Telusuri and Bersukaria, they admitted that historical and cultural destinations are the most attractive to tourists. Accordingly, they specialize in selecting specific sites that have these features.

The schedules for virtual tours also affect the number of customers. Candra noted “in April and May, we provided various schedules for the virtual tour, such as in the first week the tour was held at noon, the second week in the afternoon, and in the evening in the third week. It appeared that on weekdays, the number of tourists in the evening tour was higher, so, since June, we scheduled an evening tour on weekdays.” This change in scheduling was also influenced by companies’ policies for their staff to return to work in the office after the government’s easing of the Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar (PSBB or High-Level Restrictions) that allow new customers to join evening virtual tours after they come home from work. WKJ and JGG organize virtual tours almost every day of the week, with WKJ offers twice a day at 16:00, 19:00 (Tuesday-Friday), and 10:00, 16:00 at weekends. It also suggests that customers can book virtual tourism for a group, for a minimum of ten people, and the time and destination can be adjusted to suit customers’ wishes.

The JGG offers tours once a day on weekdays at 19:00, and twice a day at weekends at 10:00, 16:00. By contrast, Atourin and Telusuri hold three tours per week, while only once a week for Bersukaria. The reason Atourin, Telusuri and Bersukaria do not offer daily virtual tour is to avoid the decline of customers’ interest. However, in the selection of the most popular time amongst virtual tourists they are similar to WKJ and JGG offerings with afternoon or evening tours.

2.4. Cost and payment system

At the time of the research, the cost of taking a virtual tour organized by WKJ, JGG, Atourin, Telusuri and Bersukaria varied. At WKJ, the minimum tour fee for the greater Jakarta region (known as Jabodetabek for Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi) was Rp25.000 (US$1.72), Rp35.000 (US$2.41) for tours on the rest of Indonesia, and Rp50.000 (US$3.44) for overseas destinations. Unlike other tour operators, the JGG did not charge a fixed fee; instead, it encouraged customers to pay according to the level of their satisfaction. The average JGG’s customer payed between Rp30.000 (US$2.06) and Rp50.000 (US$3.44) per person. At Atourin, the fee was Rp30.000 (US$2.06) for domestic destinations, and during Eid holidays, it held a virtual tour for many favorite in-country destinations for Rp50.000 (US$3.44) per person (). Telusuri and Bersukaria’s fees were not very different from that charged by other operators, at Rp35.000 (US$2.41) per person per tour.

Figure 5. An example of information about destination and cost of a virtual tour in the Atourin’s website.

In terms of payment systems, WKJ and JGG charged their fees after their customers completed their tours. Before the tour began the operators sent bank details by email to the customers, along with the Zoom. At the end of the tour, the company reminded the customers about the bank account details into which the customers pay; also asking them to provide the name of their guide. Atourin, Telusuri and Bersukaria required their customers to pay before the virtual tour began. For customers of these three companies, they were asked to pay the fee online at the end of the registration and required to upload the proof of payment to confirm their registrations. Once they registered, Atourin confirmed the payment via email then sent the tour’s Zoom ID and password.

2.5. Theoretical reflection

The Covid-19 pandemic has severely disrupted of traditional global tourism industry but has also triggered innovation, namely the emergence of virtual tourism. The Covid-19 pandemic has stimulated the emergence of new rules (structure) governing patterns of social interactions. This new social structure has proved to play a double role: constraining one type of business and enabling another. These structures have constrained the traditional tourism activities that were operating before the pandemic, but at the same time they have served as enabling factors for the birth of virtual tourism. Theoretically, these findings enrich our understanding of the concept of structure and its “function” based on Giddens’ theory of structuration, in which he explains that the structure can “function” as constraining and enabling social practices.

Furthermore, according to Giddens, structure consists of rules and resources. In the case of the Covid-19 pandemic and the emergence of virtual tourism, it can be explained that these two elements of structure have a critical and dominant influence on the social practices of the actors (tour guides and tour organizations) that has led to the emergence of virtual tourism as a new social phenomenon in the Indonesian tourism sector. In this case, the rules have included government policies on physical distancing, working from home, quarantine and lockdown, as well as the policies of other social organizations, such as companies, universities, malls, and the absence of tourists (social actors according to Sibeon). Meanwhile, availability of a computer and reliable internet networks were also essential material structures (allocative resources) as they affected the action available for actors to take (tour guides and tourists), thus encouraging the birth of virtual tours in Indonesia.

The results of this study contribute empirical evidence to the ongoing debate of duality versus dualism. The findings clearly show that the new structures and the agency of actors represent a dualism, not duality as Giddens puts forward. Both social structure (rules) and material structure (Covid-19, computer, internet) represent external factors that have enabled the relevant actors (tour guides) to take action which has resulted in in the birth and grown of new virtual tourism activities.

Furthermore, the findings show that the social action taken by the actors (tour guides) is also influenced by their agency. Their desire to learn and adapt to change and courage to try something new (virtual tours) and the unwillingness of some conventional tour guides in the WKJ, JGG, Atourin, Telusuri and Bersukaria, to be involved in virtual tours, are the embodiment of the agency of the actors. The findings also suggest that the actions taken by social actors represent an interplay between the structure and the actor’s agency. However, referring to the R. A. Kinseng’s (Citation2017) work, it seems that structural factors, especially the pandemic and the policies to control its spread, are more dominant in influencing the action of actors in this virtual tourism.

Empirical evidence of this study shows that actors have been “forced” by the prevailing structural conditions to innovate by developing new viable ways to perform their services. In other words, the virtual tourism that emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic was basically triggered by structural factors that “forced” tour guides and organizations into new directions and action. This new business environment is very different from their earlier process of building business activities and in this new environment, the agency of the actors plays a more dominant role. For the tour operators who participated in this study, it was clear that the shift to a new business model was a product of the actors spotting a new opportunity and using their innovative minds to develop viable businesses.

3. Conclusion

This study examines the double role of Covid-19 pandemic in the tourism industry in Indonesia. Participants of this study reported that, prior to the pandemic, they never considered developing virtual tours. The Covid-19 pandemic, the rules for combating the pandemic, and the availability of computers technology and internet networks, as well as tourists interested in fulfilling their need to escape via virtual tourism are all important structural factors that have driven the development of virtual tourism. Of course, the agency of the actors (tour guides and organizers) is also important factor, influencing actor response to the structural conditions.

While virtual tourism cannot replace traditional tourism in terms of travel satisfaction, it can be used as an alternative for tourists who have limitations for actual travel, whether from physical impediments, distance, financial constraints, or time. It can also help tourists who have a plan and desire to visit a specific destination but because of the pandemic, are unable to. Therefore, it makes sense that although this pandemic will eventually end, virtual tour actors are planning to keep organizing virtual tours.

The Covid-19 phenomenon and the emergence of virtual tours in Indonesia show that the same structures could have a double role: constraining a social event and simultaneously enabling other social phenomena. This study also shows that theoretically, structures and agencies/actors represent a dualism, as oppose to duality. The structures are also external to the individual actors that triggered the emergence of virtual tourism (tour guides and organizers). In this dualism, the analysis demonstrates the factors that are more dominant in influencing particular actions of the actors. In the case of the emergence of virtual tours, the structures (Covid-19 pandemic/material structure and rules) appeared to be more dominant in encouraging the actors to develop virtual tourism.

This study contributes to our knowledge of innovation within the tourism industry. Although the Covid-19 pandemic has had a severe negative impact on global tourism, this study has shown how this phenomenon has driven Indonesian tourism actors to innovate and create a new type of tourism. This study also provides an essential theoretical contribution to sociology, specifically in providing a deeper understanding of the links between agency, actions taken by actors, and structures. Further studies on tourists’ experience of virtual tours are worth exploring for gaining insights into the prospect of this new form of industry and its potential development worldwide.

Contribution of each author

Rilus A. Kinseng, the principal author initiated the idea to pursue the and led the research process, including participating in the tours, leading the interviews. He drafted the report, did the theoretical reflection, and guided the discussion in whole process of research collaboration.

Ani Kartikasari provided critical comments and improvement of the article as well as translated the article from Bahasa Indonesia into English.

Nuraini participated in the discussion from the start of the research project, participated in the tours and conducted some of the interviews, write parts of the article, and ensure the article format in accordance with the journal guideline.

Rajib Gandi was involved the discussion from the project inception, participated in the tours and the drafting of the article.

David Dean expanded the methodology section and edited the entire paper in order to bring it up to the publication standard required by the reviewers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the important roles our informants played in this research. Their responses and access to photos and promotional material was invaluable. Therefore, we would like to extent our thanks to them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rilus A. Kinseng

As the first author, one of my research interest is about tourism issues in general. With my colleagues, we have published an article title Marine-tourism development on a small Island in Indonesia: blessing or course? in the Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research (Vol. 23 No. 11, 2018). I have also supervised several students in conducting research regarding the tourism. Likewise, Ani Kartikasari and David Dean, also has interest on tourism. With their colleagues, they have published an article title Tourist experience in Halal tourism: what leads to loyalty? in the Current Issues in Tourism, 2020 (DOI: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1813092). Nuraini, a PhD student, is also working on tourism for her PhD Dissertation.

References

- [BPS] Badan Pusat Statistik. (2019). Jumlah devisa sektor pariwisata 2015–2018. [Internet]. Retrieved June 2020, 28, from https://www.bps.go.id/dynamictable/2018/05/22/1357/jumlah-devisa-sektor-pariwisata-2015-2018.html

- [BPS] Badan Pusat Statistik. (2020). Jumlah kunjungan wisman menurut kebangsaan dan bulan kedatangan tahun 2017–2020. [Internet]. Retrieved June 2020, 28, from https://www.bps.go.id/dynamictable/2018/07/30/1548/jumlah-kunjungan-wisman-menurut-kebangsaan-dan-bulan-kedatangan-tahun-2017—2020.html

- [Kemenpar] Kementerian Pariwisata Republik Indonesia. (2019). Laporan akuntabilitas kinerja Kementerian Pariwisata tahun 2018.

- [LPEM UI] Lembaga Penyelidikan Ekonomi dan Masyarakat Universitas Indonesia. (2018). Kajian dampak sektor pariwisata terhadap perekonomian Indonesia. LPEM Universitas Indonesia. https://www.kemenparekraf.go.id/post/kajian-dampak-sektor-pariwisata-terhadap-perekonomian-indonesia

- Archer, M. S. (1982). Morphogenesis versus structuration: On combining structure and action. The British Journal of Sociology, 33(4), 455–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/589357

- Babbie, E. (2016). The practice of social research (fourteenth ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Bae, S. Y., & Chang, P.-J. (2020). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020), Current Issues in Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895

- Chen, H., Huang, X., & Li, Z. (2020). A content analysis of Chinese news coverage on COVID-19 and tourism, Current Issues in Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1763269

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Fong, L. H. N., Law, R., & Ye, B. H. (2020). Outlook of tourism recovery amid an epidemic: Importance of outbreak control by the government. Annals of Tourism Research, 102951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102951

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Univ of California Press. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=YD87I8uPvnUC&hl=id

- Hampton, M. P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2015). Power, ownership and tourism in small Islands: Evidence from Indonesia. World Development, 70, 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.007

- Hanafi, S. (2020). Post-COVID-19 Sociology. ISA Digital Platform. https://www.isa-sociology.org/frontend/web/uploads/files/Post-COVID-19%20Sociology.pdf

- Heymann, D. L., & Shindo, N. (2020). COVID-19: What is next for public health? The Lancet, 395(10224), 542–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3

- Huberman, A. M., & Miles, M. B. (1994). Data management and data analysis methods. In N. K. Denzin, and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. SAGE Publications. pp 428–444.

- Jaafar, M., & Maideen, S. A. (2012). Ecotourism-related products and activities, and the economic sustainability of small and medium Island chalets. Tourism Management, 33(3), 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.07.011

- Jaffe, E., & Pasternak, H. (2004). Developing wine trails as a tourist attraction in Israel. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(4), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.485

- Jayathilake, P. B. (2013). Tourism and economic growth in Sri Lanka: Evidence from cointegration and causality analysis. International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, 2(2), 22–27. http://ijbel.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Tourism-And-Economic-Growth-In-Sri-Lanka-–-Evidence-From-Cointegration-And-Causality-Analysis-P.M.-Bandula-Jayathilake.pdf

- Kinseng, R. A. (2020). Post COVID-19 pandemic: The old and the new normal. Paper presented at the Department of Communication Sciences and Community Development, Faculty of Human Ecology, Bogor Agricultural University, Bogor, Indonesia Monday 11 May 2020.

- Kinseng, R. A., Nasdian, F. T., Fatchiya, A., Mahmud, A., & Stanford, R. J. (2018). Marine-tourism development on a small Island in Indonesia: Blessing or curse? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(11), 1062–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1515781

- Kinseng, R. A. (2017). Structugency: A theory of action. Sodality: Jurnal Sosiologi Pedesaan, 5(2). 127–137. https://doi.org/10.22500/sodality.v5i2.17972

- Kustiningsih, W., & Nurhadi. (2020). Penguatan Modal Sosial dalam Mitigasi COVID-19. In W. Mas’udi, and P. S. Winanti (Eds.), Tata Kelola Penanganan COVID-19 di Indonesia: Kajian Awal. Gadjah Mada University Press. pp 179–193.

- Lee, C. G. (2008). Tourism and economic growth: The case of Singapore. Regional and Sectoral Economic Studies, 8(1), 89–98. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4881976_Tourism_and_economic_growth_The_case_of_Singapore

- Li, J., Nguyen, T. H. H., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2020). Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic planned travel behaviours. Annals of Tourism Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102964

- Liu, W., Yue, X. G., & Tchounwou, P. B. (2020). Response to the COVID-19 epidemic: The Chinese experience and implications for other countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072304

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (1989). Marshall, Catherine, and Gretchen B. Rossman, designing qualitative research. Sage.

- Mouzelis, N. P. (2008). Modern and postmodern social theorizing: Bridging the divide. Cambridge University Press.

- Scheyvens, R., & Momsen, J. H. (2008). Tourism and poverty reduction: Issues for small Island states. Tourism Geographies, 10(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680701825115

- Seghir, G. M., Mostéfa, B., Abbes, S. M., & Zakarya, G. Y. (2015). Tourism spending-economic growth causality in 49 countries: A dynamic panel data approach. Procedia Economics and Finance, 23( 1613–1623). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mohammed_Guellil2/publication/280386680_Tourism_Spending-Economic_Growth_Causality_in_49_Countries_A_Dynamic_Panel_Data_Approach/links/55b4293808aec0e5f434df2f.pdf

- Shahzad, S. J. H., Shahbaz, M., Ferrer, R., & Kumar, R. R. (2017). Tourism-led growth hypothesis in the top ten tourist destinations: New evidence using the quantile-on-quantile approach. Tourism Management, 60, 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.006

- Shereen, M. A., Khan, S., Kazmi, A., Bashir, N., & Siddique, R. (2020). COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. Journal of Advanced Research, 24, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005

- Sibeon, R. (2004). Rethinking social theory. Sage. https://sk.sagepub.com/books/rethinking-social-theory

- Supriyati. (2020). Gerak Relawan COVID-19: Tanggung Jawab Sosial Individu dan Masyarakat. In W. Mas’udi, and P. S. Winanti (Eds.), Tata Kelola Penanganan COVID-19 di Indonesia: Kajian Awal Gadjah Mada University Press. pp 194–213. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjM4dzWn4XrAhWf63MBHQssCa0QFjAAegQIAxAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdigitalpress.ugm.ac.id%2Fbook%2F257%2Fdownload&usg=AOvVaw154Kn05jDXB-zAE6a91s7m

- Suwignyo, A., & Agus Purwanto, E. (2020). COVID-19 dan Transformasi Paradigmatik Pendidikan Tinggi. In W. Mas’udi, and P. S. Winanti. (Eds.), Tata Kelola Penanganan COVID-19 di Indonesia: Kajian Awal. Gadjah Mada University Press. pp 107–124. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjRnZnxn4XrAhWUguYKHXKBDmwQFjABegQIAhAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdigitalpress.ugm.ac.id%2Fbook%2F257%2Fdownload&usg=AOvVaw154Kn05jDXB-zAE6a91s7m

- Vogt, C. A., Andereck, K. L., & Pham, K. (2020). Designing for quality of life and sustainability. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102963

- Weber, M. (1930/1992). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism. Routledge. https://old.taltech.ee/public/m/mart-murdvee/EconPsy/1/Weber_Max_1930-2005_The_Protestant_Ethic_and_the_Spirit_of_Capitalism.pdf

- World Travel and Tourism Council [WTTC]. (2019). Economic Impact Reports. https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

- Yang, Y., Zhang, H., & Chen, X. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913

- Zizek, S. (2020). Pandemic! COVID-19 sakes the world. New York, London: OR Books.