Abstract

The global community has been unanimous about the negative implications gender discrimination holds for economic growth and human development. While gender and power have been widely researched in the broader context of their influences on political participation, household decision-making, and overall health outcomes within various settings globally, consolidated literature on gender and power relations in organisations in the developing world remains sparse. This paper systematically reviews current knowledge on workplace gender and power relations from Africa and Asia. The review compiles past and recent studies to help scholars and practitioners better understand; the theoretical and empirical trends on gender and power relations; the unfolding trends; and how they influence employment outcomes in the labour markets of Africa and Asia. A three-stage strategy was adopted to systematically identify 67 peer-reviewed research papers from article databases to summarise the direction of scholarship. While this review generally uncovers a growing interest in workplace gender and power issues and highlights increased attention towards female economic empowerment, it also reveals that differences still exist between men and women in their use of power within organisations. These gaps perpetuated by individual, societal and organisational factors, create productivity losses due to limitations placed on women’s enrolment into the labour force and their managerial prospects.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Given the importance of gender diversity to the fortunes of organisations, we compile past and recent research to help scholars, and practitioners better understand the trends on gender and power relations and how they influence employment outcomes in the labour markets of Africa and Asia. The results reveal a growing interest in workplace gender and power issues. The findings further reveal differences between men and women relative to power within organisations, with individual, societal and organisational factors perpetuating these gaps. These power gaps and discriminatory practices create productivity losses due to limitations on women’s enrolment into the labour force and managerial potentials.

1.. Introduction

Workplace diversity, inclusion and cohesion contribute to individual efficiency and organisational success (Bae & Skaggs, Citation2019; Mousa, Citation2021). Globally, strategic businesses employ a wide range of professionals who offer diverse perspectives and contributions to business growth (Gomez & Bernet, Citation2019; Kaur & Arora, Citation2020; Paruzie et al., Citation2020; M. Sharma & Verma, Citation2021). Such diversity and inclusion initiatives have enabled organisations to reposition and respond to the dynamics of the labour markets. They have boosted conducive workplace environments and, in many cases, have fostered peaceful coexistence, mutual respect and equal opportunity for all employees (Joubert, Citation2017; Urbancova et al., Citation2020).

While the outcomes of gender-sensitive initiatives driving employee participation have generally been mixed (Asongu et al., Citation2021; Bustelo et al., Citation2019; Forgues-Puccio & Lauw, Citation2021; González & Virdis, Citation2021; Yıldırım & Akinci, Citation2021), there are important gains that cannot be underrated, including women’s increasing enrolment into the global labour force (Ortiz-Ospina et al., Citation2018; World Economic Forum, Citation2019). For example, with one in four board members of African businesses now women, the continent sits on top of gender equality in private organisations, surpassing Europe’s 23% and the global average of 17% as of 2019 (Moodley et al., Citation2019). Some countries in Africa are gradually leaping towards workplace parity, with Rwanda, Namibia and South Africa occupying the 9th, 12th and 17th positions, respectively, on the 2020 Global Gender Gap Index that ranked 153 countries (World Economic Forum, Citation2019). Rwanda, the continent’s shining example, with 84% female workforce participation, has also tripled women’s representation in middle management since 2015. Generally, Africa leads all other world regions on the scale of female labour-force participation, ranking higher at 61% (ILOSTAT, Citation2020).

However, the statistics are not so good for the Asian region where the struggle towards achieving gender parity is real at their workplaces and women are heavily underrepresented with an average of 47% labour-force participation. In terms of ascension into organisational leadership positions, the continent trails behind the global trends with women holding only 9.3% of company board seats (Deloitte, Citation2018). Though South Asia holds the world’s fastest-growing economy (World Bank, Citation2020), female labour-force participation is only 23.6% compared to 75% for men (ILOSTAT, Citation2020). Even in East Asia, where female representation is relatively high at 59%, a country like Vietnam with 73% female labour-force participation only has 22% in senior leadership positions and 25% in CEO and board-level roles (Rastogi et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Woetzel et al. (Citation2018) cite evidence from other countries in the region where women hold only a maximum of 20% of organisational leadership.

Gendered power relations affect males as well, though discussions have consistently focused on the treatment meted out to women and their relegation to menial roles (George et al., Citation2020). For some organisations, gender stereotypes influence recruitment, division of labour and job mobility (González et al., Citation2019), and sometimes men are forced to deal with specific work circumstances they would instead not choose if given the power. For example, in agricultural enterprises where heavy-lifting jobs are usually reserved for men and women do harvesting, picking or sorting, a male employee who lacks the strength to match up to his assigned role may see it as being discriminated against due to gender. Similarly, it becomes discriminatory when an organisation’s gender practices assign human resource management, sales and marketing roles only to female employees. Gender barriers at workplaces can have severe implications for national development, having been found to create huge productivity losses to employers, increasing exponentially with the increasing magnitude of bias and firm size (Hardy et al., Citation2021). For Africa and Asia, which house most of the world’s poorest people (World Bank, Citation2021), eliminating such barriers to gender parity at workplaces can positively impact poverty reduction.

While the dynamics of gender and power have been widely researched in the broader context of their influences on political participation, household decision-making and overall health outcomes within various settings across the world (e.g., Darmastuti & Wijaya, Citation2018; Felicia, Citation2021; Jankowiak, Citation2006; Khan, Citation2021; Lien, Citation2005; Mirembe & Davies, Citation2001; Wingood & Diclemente, Citation2000; Zelek & Phillips, Citation2003), systematic reviews of how the constructs outplay within the labour markets of developing economies is sparse. There is only one known study reviews the literature on gender and power within organisations. The review conducted by Ragins and Sundstrom (Citation1989) some thirty years ago consolidates scholarship on the differences between men and women in power in developed economies. This paper therefore systematically synthesise existing discourse and current knowledge to expose the most important findings pertinent to understanding workplace gender and power relations in the two fastest-growing regions and identify potential blind spots to set out an agenda for future research. The following research questions are addressed with this contribution;

How has gender and power relations evolved in workplace organisations across Africa and Asia?

What factors explain the trends and developments?

The current review begins from the year 2000, which was set as the reasonable time by which full implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action should have been done and initial achievements recorded (UN, Citation1995). The authors are convinced that literature from 2000 to 2021 capture significant developments that would help to understand better what scholars are saying about gender trends and barriers pertaining to the labour markets of Africa and Asia.

2. Literature review

2.1. Gender and power as social construct

A detailed understanding of the concepts of gender is crucial to analyse the extent of inequalities that exist in the contemporary workplace and their impacts on employee performance and organisational productivity. In this review, gender is conceptually seen as the socially constructed masculine and feminine characteristics, roles, norms and relationships rather than the biologically determined sexual traits of women and men (Kågesten et al., Citation2016). As a social construct, gender is hierarchical and produces inequalities between societies and changes across periods. These inequalities represent one of the most frequent patterns in the distribution of power. Power originates from personal traits, societal status or the kind of association between individuals, and is defined as the ability to influence other people through promises or threats Meier and Blum (Citation2019).

Gender and power are, thus, intrinsically related. To emphasise their interrelatedness, Connell (Citation1987) combined previous theories on sexual inequality, gender and power imbalances to create the “Theory of gender and power” which explains gendered relationships between men and women. Connell identified three major frameworks: “the sexual division of labour”, “the sexual division of power” and “the structure of cathexis”. Though the sexual division of labour and sexual division of power provide some explanations for gender relations, Connell created an additional framework called the structure of cathexis to capture the emotional aspect of relationships (Schippers, Citation2019). Cathexis is the social structure that shapes the differential behavioural norms for men and women and enforces male dominance over female subordination to male authority (Fleming et al., Citation2018). This explains why gendered power relations have historically favoured men and their interests (Coffman et al., Citation2021; Feess et al., Citation2021; Steinþórsdóttir et al., Citation2020).

As a result, social institutions like workplace organisations have duplicated these existing social structures resulting in power relationships (Arboleda & Arbeláez, Citation2021; Idogho & Adeseye, Citation2019; Salifu, Citation2020). This means that workplace gender and power relationships are a function of existing social structures within the environment hosting an institution and are covertly influenced by patriarchal systems where men automatically maintain possession of power (Khan, Citation2021; Ngulube, Citation2018; A. Sharma & Nisar, Citation2016).

However, to ensure sustainable progress towards workplace gender parity, there needs to be systematic changes that can discourage the negative elements of gender and power relationships and encourage diversity and inclusion at all levels within organisations in Africa and Asia. This requires a thorough understanding of the interplay between gender and power at workplaces, the nature of the barriers that limit progress and the variables that explain these trends. Given the importance of gender diversity to the fortunes of organisations, this paper aims to provide an extensive overview of recent developments in workplace gender and power relations in the context of the labour markets of Africa and Asia and compile reasons behind them.

3. Effect of women representation at the workplace

Existing literature has been unequivocal about the impact of women’s economic participation on the global economy, drawing a causal relationship between female labour force participation and economic growth (; Khaliq et al., Citation2017; Verick, Citation2018). In the developing world, women’s increasing entry into the labour market has improved labour inputs, empowered firms to grow and created wealth for nations (Appiah, Citation2018). This growth has generated increases in household income, reduced poverty among families and improved household consumption patterns. While nations develop, more resources are invested in enhancing the competence of citizens. Women also benefit from such initiatives, improve their capabilities, and accept varying work opportunities as cultural constraints fade amid globalisation.

Marginal improvements in the gender mix across various countries in Africa and Asia have yielded commensurate increases in productivity across sectors and would yield more if efforts are multiplied. It is predicted that if each country in sub-Saharan Africa makes similar improvements like Rwanda, the region could add up to $1 trillion to its combined GDP by 2025 (Rastogi et al., Citation2017). Compared to Africa, Asia’s outlook looks brighter because of its huge population, highly skilled workforce, and the availability and use of advanced technology. By 2025, annual collective GDP increases for the continent could amount to $4.5 trillion if countries in the region make concerted efforts to advance gender diversity at their workplaces.

4. Methodologies

This study was structured around the systematic review strategy of Briner and Denyer (Citation2012). The process involved: (1) Creating research questions and objectives; (2) Retrieving relevant studies through keyword search; (3) Deleting duplicate articles; (4) Evaluating the quality of articles based on inclusion and exclusion criteria; and (5) Summarising evidence and interpreting findings presented in studies. Articles were retrieved through a keyword search of eight electronic databases: Elsevier, Emerald Insight, Research Gate, Taylor and Francis, Google Scholar, Sage Publications, Wiley Online Library and Springer Link, which together shelter a broad spectrum of academic peer-reviewed journals. Following the guidelines of Valentine et al. (Citation2010), no limit was put on the number of articles to include. As a result, this literature review focused on evaluating studies that provide quality evidence to better illuminate old and emerging developments on workplace gender and power relations and what explains them.

5. Article search and identification strategy

A three-stage strategy was adopted in order to identify the literature for this review. The first stage involved a preliminary scoping search for articles exploring gender and power relations in the African and Asian contexts. In this regard, the term “gender and power” was combined with various workplace terms (i.e. work, job, employment, industry, etc.) and individually with the terms “Africa” and “Asia”. Given that the broader concept of gender and power relations has barely been studied across workplaces in both regions compared to Europe and North America, only a few studies were returned by the electronic journal databases searched. Therefore, a content analysis was conducted on the more general articles retrieved from the scoping search to derive the various topics around which the issues of gender and power relationships revolved. Titles, abstracts, keywords and headings of articles were examined to understand the characteristics of workplace gender and power relationships which, consequently, became the lead terminologies for the next round of search. Subsequently, an inclusive approach was applied to create gender and power related key phrases so as to capture existing literature that investigated the key terms identified to be associated with the various forms of the phenomenon such as follows: “gender wage gap”, “gender pay gap”, “workplace sex discrimination”, “workplace gender bias”, “workplace gender inequity”, “female labour force participation”, “female hiring bias”, “female career progression”, “female career promotion”, “female managerial discrimination”, “female leadership discrimination”, “female managers”, “women managers”, “women leaders”, “women in management”, “women in leadership”, “male dominance at work”, “job segregation”, “workplace sexual harassment”, “workplace sexual abuse”, “workplace sexual violence, “workplace bullying” and “workplace abuse of power”. These keywords were each combined with the major terms “Africa” or “Asia” to further narrow the search and pull up relevant titles that investigated these topics in the context of the two continents being considered under the current review. At the third stage of the search, the snowball strategy was adopted to review the reference lists of some of the included studies (Serenko, Citation2013). This resulted in the addition of more articles for topics which did not produce enough results during the previous search stage.

6. Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment

Throughout the initial identification processes, article titles and abstracts were examined to eliminate unrelated studies. To be included, articles needed to be published in English in recognised peer-reviewed journals between the years 2000 and 2021. Studies considered were those conducted explicitly in countries in Africa and Asia. The authors relied on the Australian Business Dean Council’s Journal Quality List (ABDC, Citation2019) and Beall’s List (Beall, Citation2021) to confirm the quality of journals and weed out predatory journals or publishers, respectively. The selection was restricted to empirical evidence and, therefore, other published works including book chapters and reviews, student dissertations, conference proceedings, editorial notes, reports and publications of governments and firms were excluded. For final inclusion, studies were required to explicitly measure the extent of a workplace gender and power-related issue or the nature of the explanatory factors or both. No limit was placed on data analysis methods used by authors as both descriptive statistics and econometric models were considered to be relevant.

Information was extracted using a standardised Excel template across the following parameters: author, year of publication, journal, publisher, study title, country or region covered, data type, gender and power indicator studied, and key findings. All extracted data were reverified to resolve discrepancies and ensure compliance with inclusion criteria.

Consequently, there was a thorough review of the full text of each article to finalise the list of literature and ensure compliance with the inclusion criteria.

7. Results

7.1. General overview of empirical research on workplace gender and power relationships

Research on workplace gender and power relationships across the African and the Asian regions published between the years 2000 and 2021 covered various topics using various methodologies and highlighted different country and workplace contexts. These studies, underpinned by different theoretical perspectives, appeared in journals of assorted academic disciplines. Out of 169 significant records identified, 102 were excluded while 67 articles were coded for inclusion (see, ), which serve as the basis for this contribution. Overall, eight gender and power-related themes emerged from the authors’ thorough review of the 67 articles. Each article was fully read to note the specific topics investigated by its authors. Even though keywords for the extraction of these articles were decided following a content analysis after a scoping review of the more generalised content on workplace gender and power relationships, the authors were also on the lookout for additional topics that did not emerge in the beginning but could be categorised along with the generally accepted gender and power constructs.

Following two additional reviews to resolve possible discrepancies, the categorisation ranked the sample under the overarching themes highlighted in . Female labour-force participation was the most researched topic, followed by gender wage gap, abuse of power and unethical behaviours and female leadership inclusion respectively. The subtotals indicated in the table add up to more than 67 as some articles investigated two or more themes at the same time. Seven out of 56 journals account for about a quarter of articles included in the present review. They are Feminist Economics (4 articles); African Development Review (3 articles); Agenda (3 articles); Asia Pacific Business Review (2 articles); International Journal of Social Economics (2 articles); International Journal of Manpower (2 articles); and World Development (2 articles). Each of the remaining papers were filed under 49 different journals.

Table 1. Emergent workplace gender and power themes

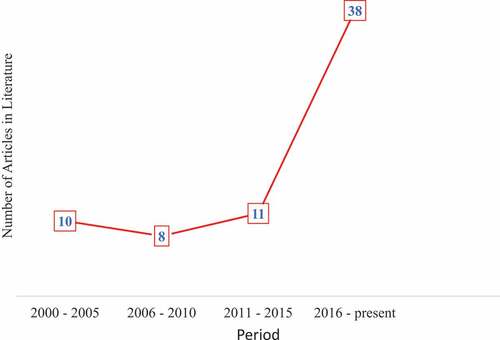

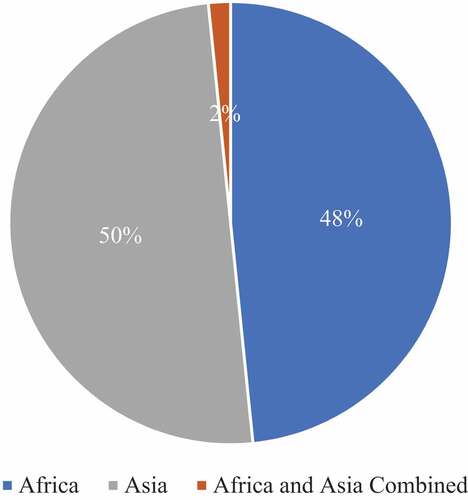

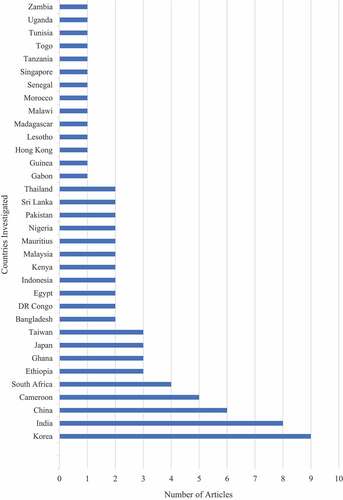

Focus on workplace gender and power-related issues improved significantly over the 21 years with the overall volume of publications increasing from ten articles in the early 2000s to as high as 38 articles in the last 6 years. This points to a growing interest in issues concerning workplace gender and power relationships in the context of Africa and Asia (see, ). On the continental level, both Africa and Asia received almost the same level of attention from researchers investigating the phenomenon under review as virtually the same number of publications examined the indicators in countries in both regions, excluding one cross-continent study which included countries in both Africa and Asia (see, ). Further analysis of research articles by country reveals that the selected papers for review spread across 34 countries (see, ). More articles examined workplace gender and power issues in Korea, India, China, Cameroon and South Africa. In total, nine papers studied the phenomenon in Korea, followed by eight papers in India, six papers in China, five papers in Cameroon and four papers in South Africa. Ghana, Ethiopia, Japan and Taiwan had three articles examining gender and power indicators within workplace organisations in each country, while, at least, one article examined cases in each of the remaining 25 countries.

8. Themes describing gender and power work relationships in Africa and Asia

Gender and power relationships captured by studies conducted in different workplace settings across Africa and Asia take varied forms, mostly stereotypical and inequitable. The critical research questions for this review were (1) how has gender and power relations evolved in workplace organisations across Africa and Asia?, and (2) what factors explain these trends and developments? The paper evaluates evidence from the earliest and most recent research for each theme and discuss the contributory factors identified in quantitative studies on workplace gender and power relationships in Africa and Asia. The relationships between the variables are presented in .

Table 2 Summary of significant variables explaining gender and power constructs

9. Female labour-force participation

Gender scholars discussed this theme in terms of the rates at which minority groups, primarily women, get employed in workplace organisations. They also highlight hiring biases against women and occupational segregation indicated by stereotypical work placement and the gender division of labour across the two regions. While some scholars report a generally increasing female labour-force participation rates, others report a relatively low female representation in workplaces. These gender disparities in labour-force representation are wider in North Africa (Robinson, Citation2005) and South Asia where Sanghi et al. (Citation2015) investigated female penetration into the labour market and reported a 50% point gap below that of the men. Though the enrolment figures in a country like Ghana have been high at 86.9%, reports of a marginal decline in recent years (Abraham et al., Citation2017 Sackey, Citation2005) and similar declines in China, Singapore and India (Chakraborty et al., Citation2018; Yoon, Citation2015) reinforce the discouraging trends reported across both continents by the previous authors who signalled a generally low workplace enrolment for females. While the latter seems to be broadly consistent with published trends (ILOSTAT, Citation2020) and passes as the domestic situation in some countries investigated, the review found a new trend unfolding in East Asia where Yoon (Citation2015) reported that women were increasingly entering the labour market at astronomically high rates in recent times. Several articles in the review sample discussed hiring biases and job segregation as the two gender and power parameters that contributed to the reported female labour-force trends across Africa and Asia. Elhoushy and El-Said (Citation2020) observed that managers’ gender and power attitudes influence their female-hiring intentions and create inequalities through hiring biases and job segregation.

Much as the new East Asian trend presents good news, these steady improvements are constantly being threatened by one primary facilitator of the low female labour-force figures seen in some countries, which usually comes in the form of selectivity bias. Four studies in the review sample delineate how African women begin their careers with discrimination experiences at employers’ hands during the hiring stages (Duraisamy & Duraisamy, Citation2016; Elhoushy & El-Said, Citation2020; Grün, Citation2004; Totouom et al., Citation2018). Using the Selectivity Corrected Decomposition Approach, Grün (Citation2004) confirmed gender career discrimination to be pervasive at the hiring stages of the labour market in South Africa. As observed by these authors, working female professionals in Africa constantly come against discrimination anytime they attempt to join an organisation. However, these gender and power related hiring biases do not only occur in African organisations as similar discriminatory recruitment practices have been identified to block women’s entry into employment in Asia (Ahmed & Maitra, Citation2010). For instance, a South Korean study by Kang and Rowley (Citation2005) reported that women did not have equal chances to be employed in organisations as men did and that, even though many jobs required equal qualifications from both genders, employment was purely biased against qualified females.

Despite the observed hiring bias reported in the current literature, the gender gap in both the African and Asian labour markets have been relatively stable, with slight progress in some countries indicating some level of participation by women (Cooke, Citation2010). However, some studies in Africa and Asia have revealed that employers downplay the capacity of women and sideline them in the productive process by restricting their work to only specific job categories (Arthur-Holmes, Citation2021; Cooke, Citation2010; Gokulsing & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, Citation2014; Obayelu et al., Citation2019; Osterreich, Citation2020). For example, while women in South Korea were posted to Public Relations, Planning, Research and Development departments, their male compatriots were mainly placed in Human Resources, General Affairs and Sales departments (Kang & Rowley, Citation2005). Other studies also mention biases in job placement, with discrimination cases reported in South Africa’s grape exports sector where women are the preferred choice for temporary jobs. This trend of employment feminisation is a typical phenomenon in the agricultural export and manufacturing sectors of the semi-industrialised economies in sub-Saharan Africa (Fontana, Citation2003; Seguino & Grown, Citation2006) and Asia (Osterreich, Citation2020). Citing additional evidence of job segregation in Japan, Cooke (Citation2010) indicated that married women usually form the peripheral of the job ladder and are mostly posted to most minor jobs below the labour market. He also reported cases in Korea and China where female employees have been inordinately targeted in retrenchment drives, laid off indiscriminately and sometimes forced into less secured casual jobs with low wages. Arthur-Holmes (Citation2021) also reported some level of occupational segregation and gendered division of labour in the mining sector. The above clearly indicates that African and Asian employers are still not confident in female employees, despite the observed productivity similarities between working men and women (Duraisamy & Duraisamy, Citation2016).

These reports of employment discrimination suggest that the interplay of gender and power begins quite early in women’s career, occurring along the entire human resource value chain and are subtly entrenched into the employee fabric over time. As a potential explanation, various authors have blamed a mix of factors for the hiring biases, job segregation and the overall involvement of African and Asian women in the contemporary marketplace. While the influence of education on women’s employment fortunes appears to be the most studied explanatory variable, the review found conflicting relationships between the two variables. Many studies point to a positive relationship while a few others report a negative association. Though Sackey (Citation2005) and Abraham et al., Citation2017) concluded that attaining some level of literacy enhances female participation in the Ghanaian labour market, women with primary education did not significantly differ from those with post-primary education in employment participation. In Mauritius where girls outperform boys at all levels of education and are expected to gain access to more and better jobs, the wrong choice of subjects is the cause of female unemployment and their relegation to low occupation jobs (Gokulsing & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, Citation2014). This prevailing trend is charactrised by Mauritian women’s preference for a degree in already loaded traditional disciplines like Education and Humanities than Science and Engineering, making it more challenging to enter the labour markets. A similar situation was reported in Cameroon where women were less likely to join the labour force (Totouom et al., Citation2018). Low female labour-force participation in some countries have been linked with patriarchal systems. In Egypt, Robinson (Citation2005) reported high female illiteracy rates, low productivity, and labour market inefficiencies as the factors influencing low female labour-force participation rates.

Literature on gender and power relationships in Africa and Asia also mention other factors that wield appreciable influences on female labour-force participation. Marital status (Abraham et al., Citation2017), age and religion (Che & Sundjo, Citation2018), fertility patterns and childbearing (Obayelu et al., Citation2019; Sackey, Citation2005), tariff cuts (Mukhopadhyay, Citation2018), GDP growth rate and Foreign Direct Investments (Idowu & Owoeye, Citation2019; Osterreich, Citation2020), and poor communication technology (Efobi et al., Citation2018) are other factors that were found to influence female economic participation. The complex interplay of gender, caste, ethnicity and religion were responsible for female joblessness in India, while institutional frameworks and paternalistic gender stereotypes are blameable for the phenomenon in most parts of the Asian region (Cameron et al., Citation2019; Cooke, Citation2010). However, the present review makes contradictory observations regarding the influence of the number of children on female labour-force participation. While a Japanese study posits that the number of children poses no negative influence on female employment (Lee & Lee, Citation2014), the reverse is the case in Guinea (Glick & Sahn, Citation2005) where childcare responsibilities limit entry into permanent employment.

The reasons assigned for the trends in female labour-force participation were situated within several theories. Sackey (Citation2005) adopts the “human capital theory” to expound on the positive influences of schooling on women’s participation in the labour market. The theory suggests that, as individuals attain higher levels of education, they become more productive and, as a result, attract better wages. This implies that women’s anticipation of better wages motivates them to upgrade their skills and maximise utility by joining the labour force. In support, Abraham et al., Citation2017) invoke the “income leisure theory” to align women’s increasing representation in employment with the utility expected from participation, which is influenced by their personal attributes, job details and the accompanying rewards. Increasing female wages impacts negatively on female labour demand. According to Idowu and Owoeye (Citation2019), this phenomenon concurs with the “theory of labour demand”, which draws an inverse link between marginal productivity and labour demand, such that higher remunerations is associated with low demand for female labour. Elhoushy and El-Said (Citation2020) operationalised the “theory of planned behaviour” to predict how gender and power attitudes influence female-hiring intentions of company bosses and create inequalities.

10. Gender wage gap and remuneration

While reviewing wage disparities due to gender and power relations, an operational definition was adopted from Yoon (Citation2015), highlighting the gender wage gap as the percentage variability in male and female employment incomes. Despite similar productivity levels among both genders, low female wages generally characterise the labour markets in countries investigated by the various authors (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2017; Patterson & Benuyenah, Citation2021; Seguino, Citation2000).

Gender wage differentials in sub-Saharan Africa follow an observed trajectory of significant pay gaps (Arthur-Holmes, Citation2021; Baye et al., Citation2016; Nielsen, Citation2000; Obayelu et al., Citation2019) and declining wage inequalities (Grün, Citation2004; Mosomi, Citation2019). For example, in a Nigerian study, Obayelu et al. (Citation2019) reported that women working in agricultural enterprises received lower remuneration than their male colleagues. Similar wage discrimination was reported in Ghana, where women in mining received less pay than their male colleagues who were allocated the high-paying jobs of extraction and processing and, as such, women needed to work beyond the regular working hours to get higher wages (Arthur-Holmes, Citation2021). Contrary findings were uncovered in terms of the distribution of these gender wage gaps. While it generally remained large at the bottom of the job market and in rural areas across sub-Saharan Africa (Kim, Citation2020; Ntuli & Kwenda, Citation2020), it was smaller at the same level in Egypt (Tansel et al., Citation2020).

Despite the visibly significant disparities in male and female wages across organisations in Asia, a narrowing trend was reported in Thailand, Korea, Japan, Singapore and India (Duraisamy & Duraisamy, Citation2016; Nakavachara, Citation2010; Yoon, Citation2015). Wage disparities were mainly smaller in rural areas than urban centres and broader at the lower end of the employment ladder as women in that category faced higher discrimination than those above (Ahmed & Maitra, Citation2010, Citation2015). Notwithstanding the low pay gap at the apex of the job ladder and the generally declining wage inequalities in Asia, the Chinese labour market remained largely inequitable. Female managers constantly suffer wage discrimination as they are paid less than male managers (Xiu, Citation2013). Salary discrimination on gender lines persist in most countries in Africa and Asia, and it is clear from the review that these disparities can be attributed to two main reasons. First, is the differing choice of skillset between men and women. These choices motivated by social norms, location, personal expectations and historical trends, among other considerations, inform where they fit in the labour market. Second, even if there is a convergence between males and females in terms of productive skills and capabilities as has been reported in some studies covered in this review (e.g., Chen et al., Citation2017; Duraisamy & Duraisamy, Citation2016; Glick & Sahn, Citation2005; Nkomo & Ngambi, Citation2009), wage gaps may continue to exist if the gender and power positions of workers determine the worth of the skills they hold. Such discrimination at the workplace is a potential cause of wage inequalities (Nielsen, Citation2000). Detailed decomposition of study results ascribed both firm-level and individual reasons to the observed wage disparities (Kim, Citation2020; Xiu, Citation2013). Differences in occupation (Tansel et al., Citation2020; Yoon, Citation2015), hours worked (Baye et al., Citation2016), age (Mosomi, Citation2019) and level of education (Baye et al., Citation2016; Nielsen, Citation2000) are the significant variables that influence gender wage gaps in Africa and Asia, apart from pure discrimination which usually takes the form of male advantage over female disadvantage. Individual choices based on women’s expectation of weaker labour-force reception has been found to explain wage disparities resulting from occupational segregation (Gokulsing & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, Citation2014). Chen et al. (Citation2017) reported similar findings in industrialised China and explained that women workers suspect gender discrimination in the labour market while searching for jobs and choose lower-wage-paying jobs. They further asserted that women cannot negotiate for better conditions of service and are usually slapped with low wages when hired by employers with sexist preferences. In two separate studies conducted in Bangladesh, discrimination against women was the primary determinant of observed wage differentials (Ahmed & Maitra, Citation2010, Citation2015). Greater export orientation reduced gender wage inequality in Taiwan (Berik, Citation2000), while increases in female education stood as the primary factor explaining the declining gender wage gap in Thailand. However, these improvements in female literacy rates superior to male literacy rates did not result in women earning higher pay than men due to unexplained factors attributable to workplace discrimination observed in parts of Africa (Nakavachara, Citation2010).

Gender wage inequality trends across most countries in Africa and Asia are similar. However, while the trend in Africa does not seem to be directly linked to the structure of the economy, the Asian situation appears to be partly engineered by the state-level policies aimed at export-oriented industrial growth and also supported by elements in the labour market who use wage inequality to increase productivity in their companies (Seguino, Citation2000). As a result, companies discriminate against female workers by underpaying them. This is how they lower per-unit labour costs and save on foreign exchange, which is subsequently spent on capital investments and expenditures on intermediate goods and services to grow their businesses. Conversely, growing foreign direct investment (FDI) as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) has contributed to higher wage inequalities (Berik, Citation2000).

11. Female leadership inclusion and discrimination

There is overwhelming consensus across scholarship regarding the state of female leadership in Africa and Asia and the factors that obstruct women’s access and ascent to managerial positions. Generally, the situation is that of subjugation and high opposition to female promotion, fewer opportunities for female leadership, low aspirations, low wages, low recognition and restrictive decision-making opportunities (Low et al., Citation2015; Budhwar et al., Citation2005; Chaudhuri et al., Citation2018; Cho et al., Citation2015; Cooke, Citation2010; Islam & Amin, Citation2016; Kang & Rowley, Citation2005; Mwagiru, Citation2019; Nkomo & Ngambi, Citation2009; Poltera & Schreiner, Citation2019; Primecz & Karjalainen, Citation2019; Rowley et al., Citation2016; Titi Amayah & Haque, Citation2017; Xiu, Citation2013).

Female leadership representation across the two continents under consideration largely remains in the single digits, though appreciable improvements have been made regarding female enrolment in the labour market. Recent studies of women in management have published rates lower than 5% in Cameroon and between 5% and 10% in Korea (Islam & Amin, Citation2016; Kang & Rowley, Citation2005). Despite these low female leadership representation figures, there are pockets of good news in countries like Lesotho, where over 40% of managerial positions are held by women (Islam & Amin, Citation2016), rates overly above the African average (Moodley et al., Citation2019). Also, while the Korean average hovered around the single-digit, some sectors like health, social work and education posted a 20% female leadership participation compared to construction and manufacturing, where less than 6% of managerial positions were in the hands of females (Kang & Rowley, Citation2005).

Though governments and companies have enacted policies to eliminate discrimination and inequalities in Japan, India, Malaysia, Thailand, China, Korea, Taiwan and Sri Lanka, women remain subjugated and underrepresented in senior leadership positions (Cho et al., Citation2015). There is enough evidence that women have obtained education equating to or exceeding that of the men in some countries. Yet, men continue to be employers’ preferred choice for senior leadership positions and, in some cases, women are confined to the periphery and have little opportunity to develop their managerial skills through capacity-building programmes (Cooke, Citation2010; Nkomo & Ngambi, Citation2009). Those who find their way into management encounter opposition developing their careers and do not get a smooth rise up the corporate ladder in Africa and Asia (Primecz & Karjalainen, Citation2019; Rowley et al., Citation2016; Titi Amayah & Haque, Citation2017). In some parts of Africa, female managers receive little or no recognition from male colleagues and work under circumstances of overt discrimination where decision-making options are limited and restricted to pre-determined domains (Mwagiru, Citation2019; Poltera & Schreiner, Citation2019). In terms of remunerations, Xiu (Citation2013) reported that female managers are rarely hired in major high-paying companies and when they are lucky to get the job, they are paid smaller firm‐size premiums.

Due to possible disruptions to family life and hostile work environments, women are not motivated to participate in managerial positions and are comfortable working in low-level positions which are immune to frequent transfers (Budhwar et al., Citation2005; Titi Amayah & Haque, Citation2017). The probable causes of this lack of managerial aspiration and several other factors shape workplace gender and power relationships, accounting for the relatively low female representation in management across Africa and Asia. While social norms and traditional stereotypes make it difficult for male employees to accept women bosses (Budhwar et al., Citation2005; Chaudhuri et al., Citation2018; Poltera & Schreiner, Citation2019; Primecz & Karjalainen, Citation2019), women’s expertise are overlooked due to nomination preferences for men which present major impediments for female managers (Mwagiru, Citation2019; Nkomo & Ngambi, Citation2009). Discriminatory recruitment also limits women’s employment chances and consequently blocks their ascent into positions of responsibility (Kang & Rowley, Citation2005). Apart from social norms and personal characteristics, organisational culture tends to influence female participation in leadership. Though inherently patriarchal and has the potential to eliminate women from positions that could prepare them for leadership, a recent study in Africa reported that women contribute to the negative effects of organisational culture on other women (Rowley et al., Citation2016; Titi Amayah & Haque, Citation2017). Women in this study felt they were their own enemies as they receive less support from fellow women when they encounter workplace hostility in their managerial ambitions.

Theoretically, Low et al. (Citation2015) took a pluralistic approach, adopting six different theories to explain their observations on the significance of female managers and board members on firm performance. Based on the theories of “legitimacy”, “agency”, “stewardship” and “resource dependency”, they argued that societies that promote female employment get more women board members as they strive to conform to society’s values.

12. Abuse of power and unethical behaviours

Sexual harassment is an expression of power mainly in unwarranted sexual advances, requests and other attitudes laced with sexual connotations (Johnson et al., Citation2018). Three categories of workplace sexual harassment have been uncovered in this review. They are supervisor-subordinate harassment, coworker harassment and verbal gender harassment (Van Wijk et al., Citation2009). A careful review of findings in articles included in this paper suggests that workplace sexual abuse is a significant problem as the canker appears to be widespread in both regions. For example, in Africa, while Galu et al. (Citation2020) found that more than two-thirds (67.8%) of females encountered sexual violence in their workplaces, a prevalence of 12% has been reported among nurses in Ghana (Boafo et al., Citation2016). Sadly, the worst culprits in these instances were superiors and coworkers expected to ensure high ethical values in their organisations. A high prevalence of workplace sexual harassment has also been found among university staff in Nigeria (Agbaje et al., Citation2021). In the East African region, sexual harassment was reported to be widespread to the extent that people in the agribusiness industry had become fed up to discuss the situation and that unmarried women and female casual workers were the most affected (Eyasu & Taa, Citation2019; Jacobs et al., Citation2015).

Most surveys conducted in Asia considered the prevalence of sexual violence and its effects on employee and organisational productivity. In Pakistan where Saleem et al. (Citation2020) revaled that, more than half (56.2%) of the cases of harassment reportedly occurred in a workplace environment. Out of the majority (72%) who did not report the case, 51.6% indicated it was not important while 24.1% said they were afraid of negative consequences of complaints. Sri Lankan women also shield away from lodging complaints of sexual harassment due to the social construct surrounding gender and sexuality. Because of self-surveillance and self-discipline, they were mainly afraid to even use the phrase sexual harassment due to fear of victimisation (Adikaram, Citation2016). Chakraborty et al. (Citation2018) established a link between sexual harassment and India’s declining female labour-force participation, arguing that prospective female employees were likely to decline jobs outside their native regions where the incidence of sexual violence was known to be high. A recent article in China also found workplace sexual harassment to be positively associated with employee depression which consequently triggers workplace deviance (Zhu et al., Citation2019).

Bullying is another common form of unethical behaviour that holds the potential to diminish employee output. However, it was surprising to see only few articles on bullying in African and Asian organisations during the past 20 years (Agbaje et al., Citation2021; Eyasu & Taa, Citation2019; Galu et al., Citation2020; Power et al., Citation2013). While three papers reported of a high incidence of workplace bullying in Ethiopia and Nigeria (Agbaje et al., Citation2021; Eyasu & Taa, Citation2019; Galu et al., Citation2020), the one study which investigated the issue in both Africa and Asia only considered the acceptability of the behaviour and concluded that work-related bullying was more acceptable in Asia than sub-Saharan Africa. Apart from the prevalence of bullying, another highlight of the Ethiopian survey was that 61% of the victims reported they were coerced to accept other peoples’ opinions and feelings without actually sharing in them. These are crucial realisations that require critical investigations as they present similar consequences that could discourage minorities and vulnerable women from participating in the labour force. It is, therefore, prudent for scholarship to focus some attention on this rather important gender and power subject.

In their attempt to explain unethical workplace behaviours, some authors associated the phenomenon with various factors. While age, educational status, marital status, work experience and the number of partners form the demographic characteristics that influence the incidence of workplace violence, the influence of social norms and organisational culture cannot be downplayed (Agbaje et al., Citation2021; Galu et al., Citation2020). Coercive labour conditions and hierarchical gender and power relations encourage sexual harassment, while hostile work environment and the absence of legislation have been found to discourage victims from filing complaints against culprits of unethical behaviours (Van Wijk et al., Citation2009; Jacobs et al., Citation2015; Park et al., Citation2019; Gibbs et al., 2019; Saleem et al., Citation2020; Shakthi, Citation2020).

Among other techniques, some studies explored workplace violence within varying theoretical frameworks. For example, Van Wijk et al. (Citation2009) raise the theory of structural power, arguing that such incidents originate from socio-cultural power gaps between males and females, making young female professionals more vulnerable. The authors maintained that the attacks resulted from sex-role constructs perpetuated within the society as postulated by the sex-role spillover theory. Similar role socialisation spillovers have ensured that sexual harassment cases go unreported due to society’s rejection of sexuality-connoting vocabulary. Explaining this phenomenon, Adikaram (Citation2016) uses the principle of social construction of reality, which indicates that their interactions with society shape individuals’ beliefs and attitudes. Thus, the inertia to file sexual harassment complaints, as exhibited by Sri Lankan women, stems from their society’s constant narrative about sexuality. Also, Zhu et al. (Citation2019) reported the negative effects of workplace sexual harassment and explained with the affective events theory. According to them, such incidents of sexual violence push employees to evaluate whether or not their welfare is under threat, which consequently affects their attitudes and triggers deviance. It is important to stress, however, that workplace sexual harassment is best explained by firm-level factors than demographic attributes (Huang & Cao, Citation2008).

13. Discussions and implications for future research

The review also exposes the sparsity of literature on discriminatory practices like hiring bias, job segregation, and workplace bullying, which have been found to block women’s enrolment into the global labour force, limit their managerial potentials, and hamper their emotional well-being productivity losses. There is a need for more in-depth studies into these constructs.

That notwithstanding, looking into the review findings across Africa and Asia suggests some congruence in most of the studies. First, they suggest that women contribute to some of the inequalities they face in the labour market through their choice of skills, employment interests and lack of interest in leadership positions. For example, studies uncovered that women commonly acquire skill sets that usually place them in low-paying jobs and shy away from jobs they expect weaker labour-force reception or those that predispose them to frequent transfers (Gokulsing & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, Citation2014). This remains mainly hypothetical and a future research could employ the “expectation states theory” and the “theory of the social role” to uncover the extent to which women’s expectations of weaker female reception into the labour markets contribute to their choice of skill and employment interest. Also, encouragingly, some studies report that women are standing up to be counted in some countries. For example, while females occupy over 40 per cent of top management positionin Lesotho, Korean women are contributing to over 20 per cent of leadership positions in health and other sectors (Islam & Amin, Citation2016; Kang & Rowley, Citation2005). This suggests that inequalities in the form of female participation in work and leadership are amenable to change. Therefore, the factors contributing to these inspiring recent trends should be investigated to provide the basis for replication in other countries in Africa and Asia.

Second, there is consensus among scholars that women and men do not significantly differ in their contributions to company productivity. However, traditions and social norms have infiltrated organisational culture to the extent that firm-level factors covertly perpetuate gender inequalities. This buttresses the role of culture and social factors in the workplace gender and power relationships and aligns with studies linking gender norms and social norms (Cislaghi & Heise, Citation2020; Lawless et al., Citation2019). In terms of female leadership in African and Asian organisations, researchers have focused mainly on the population of females in higher positions, the theories behind the discrimination and difficulties women face as they progress. However, what could influence firms to employ or promote more females into leadership positions is their level of performance or behaviour when given such opportunities. Therefore, additional research to examine the relationship between gender and leadership in African and Asian organisations is imminent. Specifically, scholars can draw on the “Role congruity theory” to explain female leadership outcomes while the “Leader categorisation theory” and “Implicit leadership theory” can also assist in decoding female leadership behaviours (Shen & Joseph, Citation2021).

Third, it was striking to know that some gender and power inequalities like the wage gap in Asia appear to be intentionally created by their economies’ structure and export orientation, perpetuated by individuals in high positions in the labour markets who benefit from it (Berik, Citation2000). In order to attract more foreign direct investments and maintain a good balance of trade, Seguino (Citation2000) explained that companies in Asia tend to segregate women into the labour-intensive manufacturing sector, where they are underpaid to reduce per unit labour costs. The accumulated wage surpluses are then reinvested in capital expenditure and intermediate assets to grow their companies. It may be safe to deduce that Asian companies are comfortable facilitating such arrangements because of their governments over-reliance on industrialisation and exports to boost their growth agenda. This may partly explain why the Asian region lags behind in ratifying and complying with various international labour conventions that could help address such workplace discriminatory practices (ILO, Citation2016). Though industries may have experienced some level of growth, these discriminatory practices are known to create employee dissatisfaction which can be counterproductive. Therefore, it is possible that well-paid female employees could have created higher profits which would spur exponential growth than the savings made through the less wages paid them. This is a grey area of comparative research that could operationalise the “Equity theory” to explore how employee motivation influences the growth rates of each of the two categories of firms, i.e., those underpaying female wages to save on per unit labour costs and, that offering equal pay for both male and female employees. This comparison could clear the clouds and possibly improve the wage gap in Asia.

Finally, it appears that legislations are virtually nonexistent and there are no formalised procedures at workplaces for victims of gender inequalities to report or file complaints for the various forms of discrimination they face (Jacobs et al., Citation2015; Park et al., Citation2019; Saleem et al., Citation2020; Shakthi, Citation2020; Van Wijk et al., Citation2009). This, coupled with social censorship, partly explains why women in Sri Lanka show no interest to report culprits of abuse of power. Legislation and complaint procedures can be promising strategies for improving workplace gender and power relationships, even though there are not enough bases to conclude that the same factors account for the victims’ lack of interest in filing complaints in other countries. Since culture and social norms influence gender and power relations, the reasons ascribed by Sri Lankan women may not necessarily explain the case in other countries in the two regions; thus, subsequent research is required to unveil the specific reasons behind the issues.

14. Limitations

Though a comprehensive search of the literature was conducted to ensure this review is conclusive, it is also likely that not every relevant study on workplace gender and power relationships in Asia and Africa within the 21 years was captured. Methodological approaches used in the selected articles were not reviewed. Also, foundational decisions concerning inclusion criteria and strategies adopted could have affected the research trends. For example, pushing the search back to 5 years before would have brought on board more evidence and improved the narrative. Again, the selection was restricted to papers published in the English language, fully accessible in the search databases explored. This could have led to possible bias in excluding studies published in the other official languages of the two continents. Nevertheless, judgment was made considering time limitations, costs and benefits of other techniques. Therefore, while this review remains an accurate research paper that will enhance the work of any researcher interested in workplace gender and power relations in the contexts of Africa and Asia, its results should be evaluated with these limitations in mind.

15. Conclusion

This paper advances the literature on gender and power relations by compiling evidence of progress and pitfalls from the labour markets of Africa and Asia, the two fastest-growing regions whose gender parity records were the poorest in the lead up to the major global commitment towards the advancement of gender equality. Uncovered in this review, is an exponential interest in workplace gender and power scholarship in the last six years with four primary constructs commonly studied during the last two decades: female labour-force participation, gender wage gap, female leadership participation, and abuse of power and unethical behaviours such as sexual violence and workplace bullying. These content areas emerged as gender and power influence discrimination in the contemporary workplace while hiring bias and occupational segregation influence female representation in the contemporary labour force. Evidence from the review also indicates that the negativities associated with gender and power relations can hamper employees’ psychological well-being, affect individual and organisational performance, and harm organisational reputation. Drawing from the selected studies, this literature review finds that workplace gender and power trends in the two regions are broadly similar and influenced by individual characteristics, firm-level factors and social norms. However, there remain some discriminatory practices mainly facilitated by national-level economic growth policies, making it difficult for governments to ratify international labour conventions that could improve gender parity in industry.

The present review contributes to literature with a compilation of past and recent research that can be employed by scholars and practitioners who require a better understanding of the theoretical and empirical trends on gender and power relations, what themes are important in understanding the unfolding trends and how they influence employment outcomes in the labour markets of Africa and Asia. Future studies should empirically explore the productivity levels of firms using wage inequality as a growth strategy and that of firms offering equal remunerations for equal work among both male and female employees. Findings of such studies may expose inefficiencies in state-level industrial policies working against women and push industry to alter gender discriminatory practices while encouraging governments to ratify international labour standards and legislate policies that promote gender diversity across business. Industrial policies must proscribe harsh punishments for companies that flout diversity guidelines and discriminate against genders. Also, programmes to promote gender equity must be designed to suit the needs of the groups involved in order for it not to promote tokenism and become counterproductive in countries with strong cultural inclinations. Career counselling efforts in various countries must discuss the interests of young people and how to help them achieve their goals and expose them to issues about possible remuneration and wage gaps for each career chosen. Lastly, programmes must also encourage young people to challenge gender-power imbalances and reject norms that foster conformity to male superiority and female subordination.

Author contribution

All authors participated in the conceptualisation, design, analysis, writing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We express our deepest gratitude to Ms Wilhemina Kwabeng Owusu for her proofreading of the draft manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Kwasi Bannor

Dixon Oppong is an agri-food commodity value chain development expert and an FBO/MSME Business Growth Consultant. He is a former National Long-Term Expert on the GIZ Green Innovation Centers for the Agriculture and Food Sectors, Ghana project. He is presently an MPhil student at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies of the University of Energy and Natural Resources, Sunyani, Ghana. His research interests include Agribusiness Analytics, Food Quality Management Standards and Certification, Agri-food Market Systems, and Rural Economic Development Models.

Richard Kwasi Bannor holds a PhD in Agribusiness from the Institute of Agribusiness Management at the Swami Keshwanand Rajasthan Agricultural University, India. He is a Senior Lecturer in Agricultural Marketing at the Department of Agribusiness Management and Consumer Studies of the University of Energy and Natural Resources- Dormaa Campus, Ghana. His research areas of interest include E-Commerce, Agricultural and Digital Marketing, Supply and Value Chains, Consumer Studies and Agrohuman Resource Management. As part of the Agrohuman Resource Management studies, we are exploring several human resource management issues which have primarily not been addressed in agribusinesses and agriculture. This study forms part of the grand research theme to reveal issues that have largely not been addressed in the agriculture context while at the same time offering insights into ways to improve the situation.

References

- ABDC (2019). ABDC journal quality list. https://abdc.edu.au/research/abdc-journal-quality-list/

- Abraham, A. Y., Ohemeng, F. N. A., & Ohemeng, W. (2017). Female labour force participation: Evidence from Ghana. The Eletronic Library, 44(11), 1489–1505. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-06-2015-0159.

- Adikaram, A. S. (2016). “Unwanted” and “bad,” but not “sexual”: Non-labelling of sexual harassment by Sri Lankan working women. Personnel Review, 45(5), 806–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2014-0195

- Agbaje, O. S., Arua, C. K., Umeifekwem, J. E., Umoke, P. C. I., Igbokwe, C. C., Iwuagwu, T. E., Iweama, C. N., Ozoemena, E. L., & Obande-Ogbuinya, E. N. (2021). Workplace gender-based violence and associated factors among university women in Enugu, South-East Nigeria: An institutional-based cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health, 21(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01273-w

- Ahmed, S., & Maitra, P. (2010). Gender wage discrimination in rural and urban labour markets of Bangladesh. Oxford Development Studies, 38(1), 83–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810903551611

- Ahmed, S., & Maitra, P. (2015). A distributional analysis of the gender wage gap in Bangladesh. Journal of Development Studies, 51(11), 1444–1458. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1046444

- Appiah, E. N. (2018). Female labor force participation and economic growth in developing countries. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: E Economics, 18(2), 1–7 https://globaljournals.org/GJHSS_Volume18/1-Female-Labor-Force-Participation.pdf.

- Arboleda, N., & Arbeláez, V. (2021). The Asante matrilineal society: Gender, power and social representations. Colombian Journal of Sociology, 44(2), 169–188 https://doi.org/10.15446/rcs.v44n2.87907.

- Arthur-Holmes, F. (2021). Gendered division of labour and “sympathy” in artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Prestea-Huni Valley Municipality, Ghana. Journal of Rural Studies, 81, 358–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.11.001

- Asongu, S. A., Adegboye, A., & Nnanna, J. (2021). Promoting female economic inclusion for tax performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 69, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.11.010

- Azid, T., Khan, R. E. A., & Alamasi, A. M. S. (2010). Labor force participation of married women in Punjab (Pakistan). International Journal of Social Economics, 37(8), 592–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068291011060643

- Bae, K. B., & Skaggs, S. (2019). The impact of gender diversity on performance: The moderating role of industry, alliance network, and family-friendly policies - Evidence from Korea. Journal of Management and Organization, 25(6), 896–913. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.45

- Baye, F. M., Epo, B. N., & Ndenzako, J. (2016). Wage differentials in cameroon: A gendered analysis. African Development Review, 28(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12168

- Beall, J. (2021). Potential predatory scholarly open-access publishers. https://beallslist.net/

- Berik, G. (2000). Mature export-led growth and gender wage inequality in Taiwan. Feminist Economics, 6(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/135457000750020119

- Boafo, I. M., Hancock, P., & Gringart, E. (2016). Sources, incidence and effects of non-physical workplace violence against nurses in Ghana. Nursing Open, 3(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.43

- Briner, R. B., & Denyer, D. (2012). Systematic review and evidence synthesis as a practice and scholarship tool. The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Management, 112–129. Oxford University Press. http://ukcatalogue.oup.com

- Budhwar, P. S., Saini, D. S., & Bhatnagar, J. (2005). Women in management in the new economic environment: The case of India. Asia Pacific Business Review, 11(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360238042000291199

- Bustelo, M., Flabbi, L., Piras, C., & Tejada, M. (2019). Female labor force participation, labor market dynamic and growth (pp. 1–36). Inter-American Development Bank.

- Cameron, L., Suarez, D. C., & Rowell, W. (2019). Female labour force participation in Indonesia: Why has it stalled? Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 55(2), 157–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2018.1530727

- Chakraborty, T., Mukherjee, A., Rachapalli, S. R., & Saha, S. (2018). Stigma of sexual violence and women’s decision to work. World Development, 103, 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.10.031

- Chaudhuri, S., Park, S., & Kim, S. (2018). The changing landscape of women’s leadership in India and Korea from cultural and generational perspectives. Human Resource Development Review, 18(1), 1–31 https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318809753.

- Che, G. N., & Sundjo, F. (2018). Determinants of female labour force participation in cameroon. Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting, 3(2), 88–103. https://doi.org/10.33094/8.2017.2018.32.88.103

- Chen, H., Chen, J., & Yu, W. (2017). Influence factors on gender wage gap: evidences from chinese household income project survey. Forum for Social Economics, 46(4), 371–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2017.1356346

- Cho, Y., McLean, G. N., Amornpipat, I., Chang, W. W., Hewapathirana, G. I., Horimoto, M., Lee, M. M., Li, J., Manikoth, N. N., Othman, J., & Hamzah, S. R. (2015). Asian women in top management: Eight country cases. Human Resource Development International, 18(4), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2015.1020717

- Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2020). Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(2), 407–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13008

- Coffman, K. B., Exley, C. L., & Niederle, M. (2021). The role of beliefs in driving gender discrimination. Management Science, 67(6), 3551–3569. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3660

- Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person, and sexual politics. stanford university press. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 8(4), 445. https://doi.org/10.1177/027046768800800490

- Cooke, F. L. (2010). Women’s participation in employment in Asia: A comparative analysis of China, India, Japan and South Korea. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(12), 2249–2270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.509627

- Darmastuti, A., & Wijaya, A. (2018). Gender power relations in development planning for forest and watershed management in Lampung, Indonesia. Gender, Technology and Development, 22(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2018.1545742

- Deloitte. (2018). Data-driven change Women in the boardroom A global perspective. Deloitte Global Center for Corporate Governance, , sixth edition, Deloitte’s Global Center for Corporate Governance, https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/risk/cyber-strategic-risk/articles/women-in-the-boardroom-global-perspective.html.

- Duraisamy, M., & Duraisamy, P. (2016). Gender wage gap across the wage distribution in different segments of the Indian labour market, 1983–2012: Exploring the glass ceiling or sticky floor phenomenon. Applied Economics, 48(43), 4098–4111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2016.1150955

- Efobi, U. R., Tanankem, B. V., & Asongu, S. A. (2018). Female economic participation with information and communication technology advancement: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 86(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12194

- Elhoushy, S., & El-Said, O. A. (2020). Hotel managers’ intentions towards female hiring: An application to the theory of planned behaviour. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36(3), 100741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100741

- Eyasu, N., & Taa, B. (2019). Effects of workplace violence on women’s psychosocial functioning in ethiopia: emotional demand and social relations at civil service sectors in focus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), NP12097–NP12124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519888634

- Feess, E., Feld, J., & Noy, S. (2021). People Judge discrimination against women more harshly than discrimination against men – does statistical fairness discrimination explain why? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.675776

- Felicia, O. (2021). A social semiotic analysis of gender power in Nigeria’s newspaper political cartoons. Social Semiotics, 31(2), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2019.1627749

- Fleming, P. J., Silverman, J., Ghule, M., Ritter, J., Battala, M., Velhal, G., Nair, S., Dasgupta, A., Donta, B., Saggurti, N., & Raj, A. (2018). Can a gender equity and family planning intervention for men change their gender ideology? results from the CHARM Intervention in Rural India. Studies in Family Planning, 49(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12047

- Fontana, M. (2003). The gender effects of trade liberalisation in developing countries: a review of the literature. Discussion Papers in Economics, 10, 1–21 https://www.ciedur.org.uy/adm/archivos/publicacion_200.pdf.

- Forgues-Puccio, G. F., & Lauw, E. (2021). Gender inequality, corruption, and economic development. Review of Development Economics, 25(4), 2133–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12793

- Galu, S. B., Gebru, H. B., Abebe, Y. T., Gebrekidan, K. G., Aregay, A. F., Hailu, K. G., & Abera, G. B. (2020). Factors associated with sexual violence among female administrative staff of Mekelle University, North Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes, 13(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4860-5

- George, A. S., Amin, A., De Abreu Lopes, C. M., & Ravindran, T. K. S. (2020). Structural determinants of gender inequality: Why they matter for adolescent girls’ sexual and reproductive health. The BMJ, 368, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6985

- Glick, P., & Sahn, D. (2005). Intertemporal female labor force behavior in a developing country: What can we learn from a limited panel? Labour Economics, 12(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2004.03.001

- Gokulsing, D., & Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. (2014). Gender, education and labour market: Evidence from Mauritius. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 34(9–10), 609–633. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-01-2013-0001

- Gomez, L. E., & Bernet, P. (2019). Diversity improves performance and outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(4), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006

- González, F. A. I., & Virdis, J. M. (2021). Global development and female labour force participation: Evidence from a multidimensional perspective. Journal of Gender Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1949581

- González, M. J., Cortina, C., & Rodríguez, J. (2019). The role of gender stereotypes in hiring: A field experiment. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy055

- Grün, C. (2004). Direct and indirect gender discrimination in the South African labour market. International Journal of Manpower, 25(3–4), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720410541425

- Hardy, J. H., Tey, K. S., Cyrus-Lai, W., Martell, R. F., Olstad, A., & Uhlmann, E. L. (2021). Bias in context: small biases in hiring evaluations have big consequences. Journal of Management, 20(10), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320982654

- Hofstede Insights (2021), “Compare countries”. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/ (accessed 25 December 2021)

- Huang, L. Y., & Cao, L. (2008). Exploring sexual harassment in a police department in Taiwan. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 31(2), 324–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510810878758

- Idogho, J. A., & Adeseye, B. O. (2019). Drama and gender power relation in african societies: The 21st century paradigm shift. Gender and Behaviour, 17(4), 14401–14412 https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1b25a984a6.

- Idowu, O. O., & Owoeye, T. (2019). Female labour force participation in african countries: An empirical analysis. Indian Journal of Human Development, 13(3), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973703019895234

- ILO. (2016). Gender equality in the labour market in Asia and the Pacific and the Arab States. International Labour Organization, November, 1–8. https://www.ilo.org/asia/publications/WCMS_534371/lang–en/index.htm

- ILOSTAT. (2020). Labor force participation rate, female (% of female population ages 15+) (modeled ILO estimate) - Sub-Saharan Africa. East Asia & Pacific, Europe & Central Asia | Data. International Labour Organization. https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/

- Islam, A., & Amin, M. (2016). Women managers and the gender-based gap in access to education: Evidence from firm-level data in developing countries. Feminist Economics, 22(3), 127–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1081705

- Jacobs, S., Brahic, B., & Olaiya, M. M. (2015). Sexual harassment in an east African agribusiness supply chain. Economic and Labour Relations Review, 26(3), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304615595604

- Jankowiak, W. (2006). Gender, power, and the denial of intimacy in chinese studies and beyond. Reviews in Anthropology, 35(4), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00938150600988166

- Johnson, P. A., Widnall, S. E., & Benya, F. F. (2018). Sexual harassment of women: climate, culture, and consequences in academic sciences, engineering, and medicine. The National Academies Press, 12(20), 312 https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24994/sexual-harassment-of-women-climate-culture-and-consequences-in-academic.

- Joubert, Y. T. (2017). Workplace diversity in South Africa: Its qualities and management. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(4), 367–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2017.1347760

- Kågesten, A., Gibbs, S., Blum, R. W., Moreau, C., Chandra-Mouli, V., Herbert, A., Amin, A., & Dalby, A. R. (2016). Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS ONE, 11(6), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157805

- Kang, H. R., & Rowley, C. (2005). Women in management in South Korea: Advancement or retrenchment? Asia Pacific Business Review, 11(2), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360238042000291171

- Kaur, N., & Arora, P. (2020). Acknowledging gender diversity and inclusion as key to organisational growth: A review and trends. Journal of Critical Reviews. Innovare Academics Sciences Pvt. Ltd, 7(6), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.06.25

- Khaliq, A., Khan, D., Akbar, S., Hamayun, M., & Ullah, B. (2017). Female labor market participation and economic growth: the case of Pakistan. Journal of Social Science Studies, 4(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.5296/jsss.v4i2.11386

- Khan, T. (2021). Gender power relations in the medical profession. Gender Equality, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, 588–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95687-9_54

- Kim, S. B. (2020). Gender earnings gap among the youth in Malawi. African Development Review, 32(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12426

- Lawless, S., Cohen, P., McDougall, C., Orirana, G., Siota, F., & Doyle, K. (2019). Gender norms and relations: Implications for agency in coastal livelihoods. Maritime Studies, 18(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-019-00147-0