Abstract

According to the International Labour Organisation, the informal sector employs more than 60% of the world’s workforce. Due to severe gender inequality in the formal sector, women dominate the informal economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. As a result, the informal sector can help with poverty reduction efforts, especially among vulnerable groups like women. Despite a number of studies examining various businesses, the informal palm oil and kernel production industry (POKPI) has garnered little attention, especially in Ghana. We used a cross-sectional survey design and pragmatism as our philosophical approach to answer the question of whether the POKPI is a safe haven or a poverty trap for women. The perspective through which we conducted this research was the Sustainable Livelihood Approach. The findings demonstrate that the POKPI has a lot of promise for providing women with long-term livelihood options. However, if its current slew of problems is neglected, it has the potential to sink its participants into a never-ending cycle of poverty. As a result, we made some suggestions for overcoming the obstacles to positioning the POKPI as a viable livelihood plan for women.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Globally, the informal sector is a major source of employment for people who are unable to find work in the formal sector. In Ghana, the informal palm oil and kernel production industry (POKPI) employs a significant number of women. The industry’s ease of entry appeals to women. However, the question that needs an answer is whether the POKPI could be viewed as a strategy for women’s poverty reduction and/or alleviation. In this study, we examine whether the POKPI provides a path out of poverty for its participants or if it is merely a trap that could trap them even deeper in poverty. According to the findings, the POKPI industry has a lot of potential for reducing poverty and empowering women. However, its current slew of problems makes it a trap with a high risk of endangering its participants in a never-ending cycle of poverty. As a result, we recommend that the government authorities prioritize the sector and meaningfully implement suggested recommendations as outlined in the study into action.

1. Introduction

Informality is a common feature across the globe, especially in developing and emerging economies. The International Labour Organisation (2018) argues that globally, more than 60% of the employed population, numbering about 2 billion, derive their livelihoods from the informal economy, despite the sector’s deprivation of decent working conditions. The informal sector is worth investing in to achieve poverty reduction outcomes (Chant, Citation2012; Chen, Citation2008; United Nations, Citation2018; World Bank, Citation2009) because many poor individuals and households work in the informal sector compared to the formal sector. Many people work in the informal sector because of the limited opportunities available within the formal sector to help them earn a living. Hence, it suffices that working in the informal economy becomes a matter of consequence rather than choice for most people.

In Africa, 86% of the total employment is within the informal sector Citation2018aIt is interesting to note that a substantial number of this population are women, constituting 90% of the informal sector and, in particular, from sub-Saharan Africa (Tinuke, Citation2012). The situation in Ghana, a sub-Saharan African country, is not any different. About 90% of the total work in Ghana is within the informal sector, of which more than half (55%) of these workers are women (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2016). Consequently, the importance of empowering women has taken centre stage in many development discourses over the last decade (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2012). Women’s empowerment, therefore, aims at building the capacities and reversing the subordinate status of women in most societies, especially in developing countries worldwide (Jahachandran, Citation2014). Thus, achieving women’s empowerment efforts has become a potential poverty alleviating strategy for most women in the informal economy. It is important to recognise that some studies have sought to understand the role of the informal sector as a livelihood opportunity for women (Baah-Ennumh & Adom-Asamoah, Citation2012; Peprah et al., Citation2019), and these studies have revealed a paucity of knowledge on the contribution and role of women in the informal economy. For instance, there is limited knowledge, particularly in the informal palm oil and kernel industry (POKPI) in Ghana, a woman dominated activity and a key component of the informal economy in the country, and this research paper sought to unravel the importance of this economic activity to the economy of Ghana. In this paper, the study sought to ascertain whether the POKPI is a sustainable livelihood strategy for alleviating poverty (‘safe-haven’Footnote1) among women or whether the industry is just an imposed choice of work among women who are engaged in it. The study begins with a review of the informal sector as a sustainable livelihood strategy for women. Furthermore, it sought to conceptualise the POKPI through the lens of the sustainable livelihood approach, and finally presented an overview of the POKPI, the methods employed, the findings, and conclusions from the study.

2. Informality as a Livelihood Strategy for Women: A Literature Perspective

There is a growing debate on whether the informal sector is a “safe haven” (a poverty reduction strategy) for women or a poverty trap for them instead. The informal sector as an industry has contributed to reducing poverty and enhancing economic empowerment, especially for women, who constitute the majority of the informal sector (Chidoko & Makuyana, Citation2012; Sparks & Barnet, Citation2010). The authors argue that, through informal activities, women generate adequate incomes to support themselves and their families. The informal sector contributes to women supplementing their family income, ensuring that their households enjoy an improved standard of living. In some cases, women do not just provide support but serve as breadwinners for their families through their informal activities. For instance, Forkuor et al. (Citation2018) argued that the informal processing and sale of marine fish is a substantial source of livelihood for women in the coastal areas of the Central Region of Ghana. Sales from this livelihood activity offer the women some economic power to contribute to household expenditures like paying rent and bills.

Some scholars share a diverging view and have questioned the sustainability of the informal economy as a poverty alleviation strategy for women (Bertulfo, Citation2011; Singh, Citation2013; Tinuke, Citation2012). According to these authors, income from the informal sector is not sustainable. They are non-sustainable because women in the informal sector are challenged and hindered from earning enough for a considerable period of time. These women have limited financial strength due to the low start-up capital, mostly gained from hard earned personal savings (Peprah, Citation2012; Tinuke, Citation2012). Also, the inadequate credit facilities for women due to the unwillingness of financial institutions to give out loans for their activities contribute to their limited financial strength (Peprah, Citation2012).

This unwillingness could be due to the informalities of the informal sector, which is characterised by poor business documentation, which is unacceptable by formalised financial institutions. The effects of the limited finances make the women unable to buy enough raw materials and the needed logistics for their operations. Forkuor et al. (Citation2018) reinforce the above assertion by showing that women in the informal sector have inadequate capital equipment.

The glaring effect of the foregoing is that women in the informal sector earn low wages, despite their labour-intensive nature and long working hours. The low wages suggest their inability to save and make substantial investments, as their incomes are just from hand-to-mouth. Low wages could account for a finding by Osei- Asibey (Citation2014) that, on average, women earn 57% of the income of men per hour in Ghana. Again, Saikia (Citation2019) shows that income generated from informal activities is subjected to seasonal fluctuations, so it cannot be a secure and reliable source of income for survival. Consequently, most women stay in the informal sector not because they earn enough but because they consider it better to be employed in the informal sector rather than be unemployed (Saikia, Citation2019; Tinuke, Citation2012). Further, women stay poor in the informal sector by being vulnerable to health and safety hazards from harsh weather conditions and the arduous nature of their activities (Amfo-Otu & Agyemang, Citation2016; Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2016; Ghatak & Lalitha, Citation2016). Apart from the vulnerability, one other effect is that women are worse-off by using their limited incomes to take care of their vulnerabilities.

The review has indicated a two-sided debate as to the prospects of the informal sector for women. This study, therefore, seeks to contribute to the discussion by examining whether the informal palm oil and kernel industry in Ghana is a safe haven for yielding sustainable livelihoods to women or is a poverty trap for vulnerable women looking to gain a sustainable livelihood. The conclusion of the paper on whether the POKPI is a sustainable livelihood strategy or otherwise among women is framed by the Sustainable Livelihood Framework as discussed in the previous section.

3. Conceptualising the Informal Palm Kernel and Oil Processing Industry in Ghana via the Sustainable Livelihood Framework

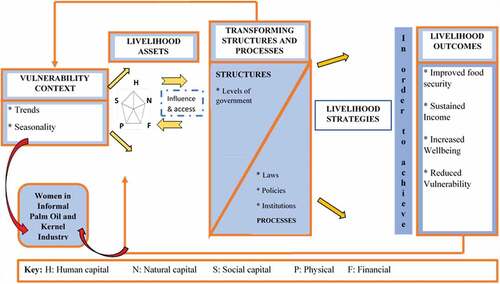

Based on the fundamental philosophies of the Sustainable Livelihood Approach (Chambers & Conway, Citation1991), several development institutions have come up with slightly different frameworks for understanding the sustainability of livelihoods. In this study, the Department for International Development (DFID) sustainable livelihood framework (SLF) is adapted to understand the sustainability of the informal palm oil and kernel industry for women in Ghana. The DFID SLF provides a broad understanding of the myriad factors that affect people’s livelihoods and the relationships among these factors. This framework differentiates between three components: the asset portfolio, which forms the core element of livelihood; the vulnerability context and policy, institutions, and processes; and the loop linking livelihood strategies and livelihood outcomes (DFID, Citation1999). The relationships between these components influence women’s livelihood outcomes, so they are linked to the framework in both the vulnerability contexts and the livelihood outcomes (see, ).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.Source: Adapted from DFID (Citation1999). Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheet.

As seen in , five broad classes of assets, including natural, social, physical, human, and financial, are dependent on for negotiating livelihoods. These assets are the tangible (resources and stores) and intangible (claims and access) resources that supply material and social means (Chambers & Conway, Citation1991) on which livelihoods are built. They form the core of the SLF and relate to all the components of the SLF.

Human capital encompasses the abilities, experience, working skills and physical state of good health (UNDP, Citation2017). The quality and quantity of human capital impact the type of livelihood strategy pursued by households. For example, a significant relationship exists between the level of education of households and their livelihood strategies (Dehghani Pour et al., Citation2018). Moreover, other studies (Hua et al., Citation2017; Soltani et al., 2014; Su et al., Citation2009) have found a positive correlation between households’ access to human and financial assets and the adoption of non-agricultural strategies. Social capital is obtained through individuals’ and groups’ membership in a social network (Álvarez & Romaní, Citation2017), and households’ endowments of this capital are sometimes dependent on other assets, financial and human (Dehghani Pour et al., Citation2018). For the most deprived, social capital often stands as a place of refuge in mitigating the effects of shocks or lack of other capital, through informal networks (Kollmair and Gamper, Citation2002). Natural capital is the term used for the natural resource stocks from which resource flows and services (such as land, water, forests, air quality, biodiversity degree and rate of change, etc.) useful for livelihoods are derived (Kollmair and Gamper, Citation2002). Financial capital denotes the financial resources that people use to achieve their livelihood goals, and it is the availability of cash or equivalent that enables people to adopt different livelihood strategies. There are two main sources of financial capital. The first is available stocks (cash, bank deposits, or liquid assets such as livestock and jewelry that do not have liabilities attached and are usually independent of third parties). The second is regular sources of money, such as labour income, pensions, other state transfers, and remittances. The regular sources of financial capital are dependent on others and need to be reliable. Among the five categories of assets, financial capital is the most versatile. They can be converted into other types of capital or used for the direct achievement of livelihood outcomes. However, financial capital is the least available form of capital to the poor, making other forms of capital an important substitute (Kollmair and Gamper, Citation2002). Physical capital forms the basic infrastructure (changes to the physical environment that help people meet their basic needs) and producer goods (tools and equipment that people use to function more productively) needed to support livelihoods. (UNDP, Citation2017). They include affordable transport, secure shelter and buildings, adequate water supply and sanitation, clean, affordable energy, and access to information. The price tag and secure access to infrastructure for the poor in society are as important as their physical existence. The mere presence of physical infrastructure does not cater to the benefit of the poor, as they may not have the means to access it. The informal palm oil and kernel industry depends on all five sets of assets, and the women taking part in the sector command varying degrees of each of the assets for the realization of their livelihoods.

All the assets noted above do not occur in isolation but within complex and varying levels of vulnerability contexts, including changing trends, shocks, and seasonality. The vulnerability context is the external environment where people exist and gain importance for their livelihoods (Devereux, Citation2001). The prevailing vulnerability contexts can either create or destroy the assets available to households and include trends, shocks, and seasonality. In the context of this study, the core vulnerability context within which the POKPI operates is the seasonality of the sector’s major asset (palm fruit), which leads to price fluctuations and changing output levels.

Further, the livelihood assets are directly related to the prevailing transforming structures and processes. These assets are profoundly influenced by existing institutions and policies in three broad ways (UNDP, Citation2017). First, they create assets through, for example, government policy to invest in basic infrastructure (physical capital) or technology generation (yielding human capital) or the existence of local institutions that reinforce social capital. Second, they determine access to assets through, for example, ownership rights or institutions regulating access to shared resources. Finally, they influence rates of asset accumulation through, for example, policies that affect returns to different livelihood strategies, taxation, etc.

These relationships are always two-sided and can go either way. Individuals and groups of individuals can also strongly influence the transforming structures and processes. Individuals’ and groups’ ability to constructively influence existing institutions and policies is dependent on their abilities, hence the call to empower people. A considerable number of non-governmental and policy think tanks have arisen over the past decades. They empower people and provide a voice for the voiceless concerning their access to resources in various sectors.

Also, the livelihood strategies adopted by households and the resulting livelihood outcomes, as shown in the SLF, hinge on the asset portfolio available. The more diverse and developed the assets available to a household, the greater the range of opportunities and the ability to pursue and switch between multiple strategies to secure their livelihoods (Fang et al., Citation2014; Scoones, Citation1998; UNDP, Citation2017; Wu et al., Citation2017). Similarly, the livelihood outcomes of households result directly from the assets available to them. Different assets are dependent on different livelihood outcomes.

4. The informal palm oil and kernel industry in Ghana

Palm oil and kernel production play a crucial role in supporting livelihoods and food security in Ghana. The oil palm fruit is the most important edible oil crop in Ghana and the whole of the West African region (Suarez et al., Citation2013; Angelucci F., 2013., Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], Citation2013). In 2012, Ghana produced over 120,000 tons of palm oil, making it the 15th largest producer globally (Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO], Citation2012). The palm oil and kernel processing industry in Ghana includes large, medium-sized, and small-scale processors. The sector provides income for many peri-urban and rural populations and comprises small-scale processors working either in groups or as individuals (Ofosu-Budu & Sarpong, Citation2013). The informal small-scale processors account for 80% of the total palm oil production in Ghana, and many of these processors (80%) are women employed as wage workers (Angelucci, Citation2013; Ministry of Food and Agriculture [MOFA], Citation2012).

In the study area, Bekwai Municipality in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, the informal sector is the largest employer, absorbing 88.9% of the population (Citation2014. The local economy of the municipality consists of three subsectors: primary production, manufacturing, and services/commerce. Informal palm oil and kernel processing is a subsector of the small and medium scale manufacturing industries that accommodate about 25%—29% of the industrial labour force in the municipality (Bekwai Municipal Assembly, Citation2014a). Despite the significant proportions of the industrial labour force in this subsector, the subsector has not received the needed attention from the Municipal Assembly and development partners. This lack of attention may be due to two things: first, an inadequate understanding of the prospects the subsector holds for the development of the local economy of the municipality; and secondly, the viability of the subsector to be developed as a sustainable livelihood strategy for women has not been assessed. This study, therefore, seeks to provide an insight into the informal palm oil and kernel processing industry to understand its potential as a sustainable livelihood strategy for women.

5. Material and Methods

5.1. Study area

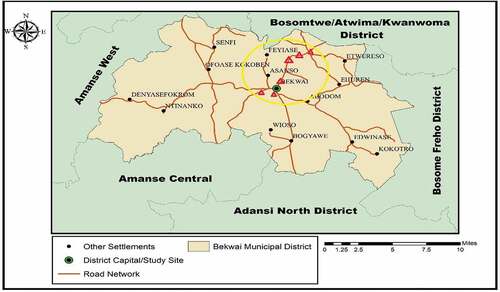

The study was in the Bekwai Municipality ()

5.2. Research Approach and Design

The study adopted pragmatism as its philosophical approach. This approach argues that strictly choosing one position is unrealistic in practice and prefers a blend of qualitative and quantitative data and methods in a study to resolve a real-life world challenge (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011; Ihuah & Eaton, Citation2013). As such, we adopted a mixed research approach. This approach allowed procedures that implemented both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis techniques. Through this integration, comprehensive and synergistic data was collected and analysed. Specifically, a cross-sectional survey design was adopted to study a section of women in informal activities in the Bekwai municipality.

5.3. Sampling design

Using a mathematical formula by Gomez and Jones (Citation2010), a sample of 80 women working in the palm oil and kernel industry in Bekwai municipality was selected for the study. This formula generated an unbiased and representative sample size at different levels of precision (95% in the case of this study). Moreover, it is discipline-specific and was used in a similar study (Obodai et al., Citation2018). The formula is stated as [n = N/ (1 + N e2)] where n = sample size, N = population size, and e = level of precision with a 5% margin of error. Proportional sampling was then applied to arrive at the exact number of women to be selected from each of the six communities selected for the study (see, ).

Table 1. Calculation of sample size for each sampled community

Because the sample size was almost the same as the sample frame, we used the convenient sampling technique to interview available women until the 80th person. The women were purposively selected from six different communities in the Bekwai Municipality, which is known for its palm kernel and oil production. The communities were Bekwai Zongo, Adankragya, Esumangya, Assebium, Kokofu Abankasum, and Sebedie.

5.4. Data Collection

An interview was the main procedure used in gathering primary data for this study. Also, non-participant observations helped in collecting data from the working environments of the study participants (Bryman, Citation2016; Creswell, Citation2014). A semi-structured interview (SSI) guide, made up of both open-ended and closed-ended questions and consisting of twenty-seven (27) items, was used. We interviewed the study participants in their respective working environments. This arrangement made them comfortable and willing to provide the necessary information needed to answer the research question (Bryman, Citation2016). The interviews were conducted in the late afternoon, between 4 p.m. and 6 p.m., when many of the study participants were wrapping up their daily activities. Verbal consent was obtained from each study participant before the interview. Because the data was for academic purposes, no incentives were paid to the participants. To guarantee anonymity, no names were assigned to study participants, and no personal identification details were recorded. Because of the low literacy level of the participants, the interviews were conducted in Twi (the local dialect of the study area) to serve their needs. The primary data was complemented with secondary information gathered from journal articles, institutional repositories, and the internet.

5.5. Data Analysis

The dataset was serially numbered and cross-checked for consistency before data analysis began. The data codes were based on these serial numbers. IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 23) was used to analyse the quantitative data using descriptive statistical tools such as frequencies and descriptives. For the qualitative data, no computer-aided software was used. Instead, a recursive abstraction was applied (Polkinghorne & Arnold, Citation2014). Data were summarized and re-summarized until a focused and very brief summary that was both accurate and distinct was obtained. Using the convergent mixed analytical method (Creswell, Citation2014), quantitative and qualitative results were discussed, and conclusions were drawn. Thus, while inductive inferences were made from text responses, deductive interpretations were made from the quantitative data.

Key subjective views were presented using direct quotations. Two criteria were developed to ascertain if the POKPI is a sustainable livelihood or a poverty trap for women. First, for the POKPI to be considered a sustainable livelihood for women, there must be adequate access to three or more assets and favourable structures and processes. This criterion is denoted as “safe haven”. Secondly, access to fewer than three assets is considered inadequate. This inadequacy, exacerbated by the prevailing structures and processes, has the potency of plunging the women in the POKPI into a vicious cycle of poverty. This criterion is what we refer to as the poverty trap.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Background of study participants

As shown in , 42.5% of the women were aged 40 to 59 years, and 30% were aged 60 and above. The remaining 27.5% were 21 to 39 years old. The ages show that the POKPI accommodates and provides a livelihood opportunity for both the young and the old. The highest level of education attained by 16% of the study participants was junior high school, whereas the majority (55%) had no formal education. Moreover, most (72%) of the women were married, out of which 53.8% were household heads.

Table 2. Background of Respondents

6.2. The sustainability of the informal palm oil and kernel industry for women

Livelihood strategies depend on the range of capital available to pursue different activities that enable one to secure a sustainable livelihood (DFID, Citation1999; Farrington et al., Citation1999; Scoones, Citation1998). Women in the POKPI have access to a variety of all five broad classes of capital. Among these classes of assets, social, physical, and financial capital are the least available and developed and pose the greatest threat to the sustainability of the POKPI. The following sections elaborate in-depth on the various capital endowments of the women in the POKPI and how they impact their livelihood in the POKPI.

6.3. Analysis of human capital

From , the POKPI does not require ambitious standards in terms of human capital (abilities, experience, education, e.t.c.). The processes of palm oil and kernel production are not sophisticated, and they are predicated on training rather than formal education. Most (55%) women employed in this industry, therefore, lack formal education. This finding conforms with that of Hua et al. (Citation2017) and Dehghani Pour et al. (Citation2018), who found a correlation between the level of education of people in the informal sector and the livelihood strategies they can negotiate. As noted by Dehghani Pour et al. (Citation2018), there is a positive correlation between education and livelihood strategies adopted within the informal sector. The higher the education level of an individual or household, the higher their livelihood strategies will be, with most people having a higher education shunned away from agricultural industries. In addition, the survey shows that the POKPI attracts both the young and the old, and an overwhelming majority of the people involved in the sector are aged 40 and above. Also, the industry was more appealing to married women who serve as household heads too. (See, ). This appeal may be because these categories of women need to accumulate other assets to meet their household needs since most women in Ghana have inadequate access to resources (Osei- Asibey, Citation2014). This finding is in line with that of Forkuor et al. (Citation2018), which shows that women, through their informal activities, serve as breadwinners for their households.

6.4. Analysis of natural capital

Concerning natural capital, women working in the POKPI were well endowed. The most important raw material (oil palm) for the POKPI was readily available in the municipality. Its cultivation dominates the entire cash crop in the municipality due to its soil suitability and ready market for the produce (Bekwai Municipal Assembly, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Citation2014). Over five hundred hectares have been cultivated in the municipality (Bekwai Municipal Assembly, Citation2014a) with a proposal by the Municipal Assembly and the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA) to set up a nursery for farmers to supply quality seed at affordable prices, enabling them to get a good yield from their produce (Bekwai Municipal Assembly, Citation2014a). The land for this proposed project was, at the time of the study, already acquired at Anwiankwanta.

In addition, statistics from Citation2014 show that 1,066 households, which translate into a total population of 5,271–2,550 males and 2,721 females in the Bekwai municipality, are engaged in growing oil palm. A gross look at this statistic points to a substantial number of women cultivating the raw materials for the POKPI. A sizable number (30%) of the women working in palm oil and kernel processing received their raw materials from their farms. Most of the women buy it from neighbouring communities in the municipality. From the above, the municipality is well-endowed with the requisite asset (oil palm) that can be developed to offer a sustainable livelihood for women.

6.5. Analysis of financial capital

Despite the low average start-up capital of GHC250 (the equivalent of $41Footnote2), access to financial capital to expand and develop the processes involved in the activities of the POKPI was a major challenge. This challenge is similar to what other women working in the informal sector in South Africa, Nigeria, and Ethiopia experience (Deribie, Citation2012; Etim & Daramola, Citation2020). A substantial percentage (36%) of the women either started with as little as GH¢50 ($8) or the business was passed on to them, requiring no capital (See, ). These funds were raised through personal savings by the majority (71%) of the participants. This finding confirms the study of Aliber (Citation2015) in Kampala (Uganda) and Nagpur (India), where informal operators rely more on personal savings than on any other financial source, especially when the volume of money involved is not much. Loans are an option only when the initial capital needed is high (Aliber, Citation2015). Therefore, with the start-up cost of POKPI being low, loans from the bank or individuals are only subscribed to by a few. This finding aligns with different studies in Ghana, including those of Amoako-Tuffour (Citation2007) and Adingo (Citation2016). These studies all found that the low start-up capital requirement for the informal sector makes loans from banks the last resort.

Table 3. Startup Capital

The use of outdated and traditional methods in the POKPI, peculiar to many other informal businesses (Deribie, Citation2012; Etim & Daramola, Citation2020), accounts for the low start-up capital. In the major centres of the district where the palm oil and kernel processing occur, for example, Bekwai Zongo and Kokofu, only one milling machine was available for use by all the women in the centre. Other centres do not even have milling machines. The women rely on primitive ways or travel long distances within the district to mill their palm fruit. This infrastructural challenge confirms the work of Angelucci (Citation2013) that shows small-scale palm oil processing units in Ghana have weak milling capacity. This weak milling capacity is because most women in the industry are handicapped financially due to the difficulty of accessing financial support from financial institutions because of the undocumented nature of their business and their inability to supply collateral for loans. For many women, their only possibility of survival in business was to borrow from friends and family to supplement their savings.

However, this choice is bemoaned as not exceptionally reliable and stable. One participant, nostalgic about the challenge of finance, intimated as follows

“I want to have my own building where I can work and get more raw materials.” I want to hand over the business to my daughter very soon, so I must keep it alive. But I am struggling to get enough money to do these.” [SSI, 07]

The above expression summarises the quandary of most of the women in the study area, and it is in line with some studies (Baah-Ennumh & Adom-Asamoah, Citation2012; Peprah et al., Citation2019) that show the unavailability of financial capital as a major challenge for women in the informal sector.

6.6. Analysis of social capital

The influence of both external and internal social capital on the activities of informal businesses cannot be underestimated (Dai et al., Citation2015). They supply channels of credit support and market information. However, this capital is the least developed among women in the POKPI. Even though in some areas, like Bekwai Zongo, many women were working in a particular hub, they went about their activities independently. Except sometimes using the same milling machines, the women operated independently. There were no formalised groups of membership with mutually agreed or commonly accepted rules to champion their interests and aspirations within the industry. This lack of formalised groups limits their potential to have access to other capital towards improving their business. For instance, a well-organised cooperative group of women in the POKPI could help cooperate, reduce some transaction costs (DFID, Citation1999), and receive financial support from financial institutions.

6.7. Analysis of physical capital

Physical capital was another form of capital that was problematic for women in the POKPI. To process palm oil and kernels, access to water, electricity, and milling machines is imperative. However, women in the industry had no reliable water source close to where they worked. They must travel long distances to access water. This challenge delays production and leads to a loss of productivity. In addition, frequent electric power outages were a major physical capital failure, affecting the operation of the women. This problem slowed down the activities of the women considerably, as the milling machines for milling the palm kernel for further production use electricity. When this happens, the women must wait for several hours before electricity is restored to their homes to continue their production.

Worsening this situation was also the very few milling machines in the municipality, resulting in undue pressure at the milling shop immediately after electricity is restored after being out for some time. The women complained of having to join a long queue for extended hours before getting their nuts milled. Further, the high pressure exerted on the few mining machines causes them to break down often. One of the women bemoaned the following sentence:

“Sometimes I go to the milling shop in the morning and come back to my house in the evening”. [SSI, 045]

The above sentiments are the feelings and realities of most women in the industry and confirm the lack of adequate basic infrastructure to support sustainable livelihoods in the informal sector, as reported by other studies (Baah-Ennumh & Adom-Asamoah, Citation2012; Etim & Daramola, Citation2020). The challenge of physical infrastructure in Ghana’s informal sector was confirmed to be like that of Nigeria and South Africa in a recent comparative study by Etim and Daramola (Citation2020).

Analysis of the vulnerability context and the structures and processes within which the POKPI operates

Many informal sector activities are characterised by seasonal, and other variations over time (OECD, Citation2002). Seasonality is the most critical vulnerability context within which the POKPI operates. Production and supply of oil to meet both local and international demands fluctuate with the growing seasons. Two main growing seasons exist within the study area. These are classified here as the peak and lean seasons. During the peak season (February to May), palm fruits (raw materials) are in abundance, and the women can produce more oil. More oil, however, results in low returns (sales) due to the high supply of oil in the local market. During this season, buyers dictate the price they would like to offer, and the women have no choice but to accept them or incur losses. Consequently, the oil is sold cheaply, sometimes just to meet production costs (break-even). In contrast, the lean season (June onwards) promises soaring prices for palm nut and kernel oil because of inadequate palm oil and kernels on the local market. The season is characterised by the very scarce availability of the raw material for production; thus, a substantial number of women can only produce low yields.

As shown in , women produce an average of 9 gallons of oil during the peak season, compared to only 4 gallons during the lean season. Women can not produce half of the total output recorded during the peak season during the lean season. However, the income derived from such sales is more than half the amount obtained for the peak season (Table 6). This statistic shows that women receive increased income for producing less in the lean season and get less income for supplying more in the peak season.

Table 4. Incomes and Outputs during Peak and Lean Seasons

To summarize, the seasonality context in which the women working in the POKPI operate presents a unique challenge of a negative correlation between yields and income, all else being equal. This negative correlation shows the powerful interplay of the invisible hand of demand and supply at work. The persistence of this challenge year after year reflects the issue of lack of leadership. Price fixation is the sole prerogative of women who do so based on intuition and immediate need. Furthermore, the challenge of outdated storage machinery, as well as the women’s lack of technological expertise and skills, exacerbates the vulnerability context.This finding confirms the study by Osei-Boateng and Ampratwum (Citation2011).

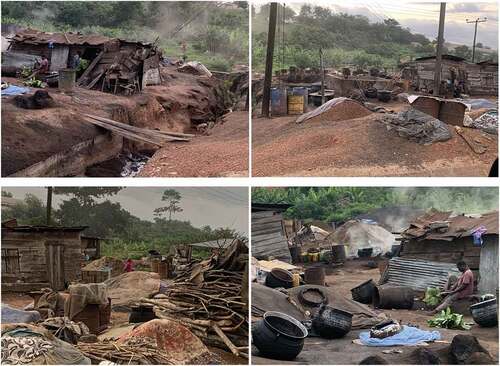

Also, the Municipal Assembly, serving as the institution mediating between the government and women, had nothing substantial and specific for the POKPI. At the time of the study, there was no policy regulating the activities of the POKPI, although the assembly acknowledged the presence of the POKPI and their inputs for local economic development. This situation is expressed vividly in the disorganised and poor governance of the industry. The women worked haphazardly and in poor locations since they had no organised place of work. Some worked in front of their houses, far away from the market. They, therefore, had to incur high transportation costs in transporting their finished products to the market. The scattered nature of the industry hindered women from enjoying economies of scale, including an exchange of skills and market pull, among others. This situation confirms and reinforces the Bank of Ghana’s (Citation2007) claims that the informal economy is unorganised and unregulated. The few women whose activities were organised, especially at Bekwai Zongo, worked at the mercies of harsh weather conditions because the site lacked any sheds (See, ). The lack of a shed exposed the women to sunshine, rain and other unfavourable weather conditions with dire health implications. Also, the rain sometimes destroys the raw materials that the women have intentionally exposed to the sun for drying. There were complaints of headaches after daily activities because of exposure to the rays of the sun. One of the women lamented as follows:

“As you can see, there are no structures here under which we work. We work in the open sun. Mostly, I go home in the evening very weak. I have paracetamol in the house that I take every evening to reduce my pain”. [SSI, 024].

Figure 3. Collage of pictures showing the poor working condition of the women in the POKPI at bekwai zongo.Source: Author’s observation

Osei Boateng and Ampratwum (Citation2011) found similar situations of women exposed to bad environmental and hazardous conditions that threaten their health and safety.

Also, the organised women at Bekwai Zongo lacked permits to work in their current location. The lack of permits left them unprotected and at the mercy of the landowner, who issued several evacuation threats as he demanded his land. The risk of evacuation made them susceptible to exploitation. They were forced to pay some lump sums of money to appease the owner and allow them to continue as squatters on his land. Two of the women indicated

“We do not have space to operate. Even this small space we have, is a squatting place”. [SSI, 039]

“Mostly, the owner comes to us unawares, asking us to evacuate. We have always been paying money dictated to us by him so that he allows us to have our peace of mind”. [SSI, 55]

The absence of physical assets in the form of an organised place of work noted above clearly suggests the failure of the structures and processes needed for sustainable livelihoods. This finding affirms the study by the World Bank (Citation2009, as cited in Spark and Barnet, Citation2010), which found that women are coerced to bribe their way through carrying out their activities, which has made the informal sector characterised by massive bribery and corruption. Also, Osei-Boateng and Ampratwum (Citation2011) show that the informal economy is characterised by tenure insecurity, with the operators in the sector often fearing forced eviction.

6.8. Livelihood strategies and outcomes

Access to diverse levels and blends of capital is undoubtedly a key influence on the choice of livelihood strategies. As explained and discussed in the preceding sections, women working in the POKPI have access to diverse levels and combinations of capital. This capital access determines the strategies they adopt to make a living from the industry. From the analysis, it is clear that the POKPI is indeed a significant livelihood strategy for women and their households. Because some of the women are household heads, there is a multiplier effect of their gains to cover their dependents.

The POKPI as a livelihood strategy for women contributes to sustained income generation and food security. Despite the fluctuations in output prices and, consequently, the income obtained from sales, women involved in the POKPI have a sustained income at the end of every month. As presented in Table 6, the women had an average monthly income of GH¢745 ($124). Using the internationally agreed poverty line of US$ 1.90 a day (United Nations, Citation2019) as a measure of poverty, none of the women in the POKPI are income poor. However, poverty is multi-dimensional (Sen, Citation1992, Citation1993; Thorbecke, Citation2013). Therefore, the overall well-being of these women, as well as their ability to reduce their vulnerabilities, is critical. Based on the poor working conditions of the women and the challenges associated with their livelihood assets, the POKPI cannot be fully described as a sustainable livelihood opportunity.

Also, the industry can offer livelihood opportunities for other people aside from women, directly and indirectly, although at reduced capacity. The 80 women who participated in the study employed 121 workers. This number was even a little lower than the total number of 147 they hired the previous year. On average, the total number of people employed by the women ranged from two (2) to eight (8) (refer to ). This statistic shows the industry’s strength in generating sustainable livelihoods for other supporting employees, either men or women. These total numbers exclude the job opportunities the sector produces indirectly from the broad spectrum of people supplying supporting services such as millers, nut crushers, transport officers, farmers, etc.

Table 5. Employment Capacity of the POKPI

Furthermore, the POKPI as a livelihood strategy has enormous potential to contribute to improved food security. The POKPI offers women access to financial resources. This financial access can support economic access to food, improving food security outcomes. Moreover, the production and sale of palm oil and kernels will increase food availability. This availability in both the local and external markets will contribute to improved food security outcomes.

7. Conclusions

The analysis of the POKPI as a livelihood strategy for women is key to improving the economy of Ghana and the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals Five (5) and Eleven (11), which seek to promote gender equality and promote the availability of decent jobs, respectively. The analysis has shown that the informal POKPI is an important livelihood strategy for women and their dependents. The industry holds great prospects that can be harnessed to create direct jobs for women and indirect jobs for both women and men.

The industry can be adopted as a strategic venture for empowering women, as it offers job opportunities for a range of age cohorts. Also, the start-up capital in the industry was low, suggesting that with little financial assistance, more women could gain jobs within that industry. Besides, the study area is well-known as an oil palm production hub in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. Access to raw materials will therefore not be an issue.

Despite the prospects of the POKPI, the industry is faced with access to asset difficulties. Most women in the industry have inadequate access to three or more assets. Specifically, the women are confronted with limited and permanent space to work. They lack support from the Municipal Assembly and financial institutions. In addition, they experience seasonal fluctuations in prices and have limited access to infrastructure like water, electricity, and milling machines. They, therefore, resort to the use of manual and primitive processing methods. These challenges limit the prospects of the POKPI as a sustainable livelihood strategy for women. Against this backdrop, we conclude that the POKPI is not a “safe haven” for women but a poverty trap that may plunge many of its participants into poverty if the challenges are ignored. To address these challenges, we have a few recommendations. First, the capabilities of women should be enhanced through skill development. Second, the study suggests that the municipal assembly play an active role in providing the necessary physical infrastructure as well as financial support/services to women. Finally, we recommend that women be encouraged and supported to form cooperative groups to develop and build on their social capital. This and others will ensure the POPKI offers sustainable livelihoods, promotes women’s empowerment, and has a multiplier effect on local economic development in the municipality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jacob Obodai

The authors are a group of academics from the Christian Service University College’s Department of Planning and Development in Kumasi, Ghana. Paul, a senior research fellow, who was on sabbatical leave at the University College at the time of this study and served as the Department’s head, leads the team. Jacob is a final-year PhD student at the Open University in the United Kingdom. Both Abena and Festus are PhD candidates at Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). Paul has returned to KNUST to work as a senior research fellow and the coordinator of the Urban Studies Program.

The group collaborates on projects centered on their shared research interests, which include rural and urban informality, food security, urban planning and development, and housing issues. This study is part of a larger project aimed at better understanding the sectoral development management processes and challenges in the Ashanti region’s Bekwai Municipality.

Notes

1. The criteria of determining whether the POKPI is a safe haven or a poverty trap, framed from from the sustainable livelihood framework guiding this study are explained in the analysis section.

2. The rate of a US Dollar to a cedi was $1 = GHC6.03 as at August 2021.

References

- Adingo, T. M. (2016). Banks contribute only 7.9% to informal sector start-up capital. Business & Financial Times Online-Ghana. July 19. http://thebftonline.com/business/economy/19997/banks-contribute-only-79-to-informal-sector-start-up-capital-.html. [14th June 2017]

- Aliber, M. (2015). The importance of informal finance in promoting decent work among informal operators: A comparative study of Uganda and India. International Labour Office, Social Finance Programme. Geneva: ILO (Social Finance working paper; No. 66)

- Álvarez, E. C., & Romaní, J. R. (2017). Measuring social capital: Further insights. Gac. Sanit, 31(1), 57–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.09.002

- Amfo-Otu, R., & Agyemang, J. K. (2016). Occupational health hazards and safety practices among the informal sector auto mechanics. Applied Research Journal, 21, 1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315826350_Occupational_Health_Hazards_and_Safety_Practices_Among_the_Informal_Sector_Auto_Mechanics

- Amoako-Tuffour, A. (2007). Poverty Reduction Strategies in Action: Perspectives and Lessons from Ghana. Lexington Books.

- Angelucci, F. (2013). Analysis of incentives and disincentives for palm oil in Ghana. Technical notes series, MAFAP, FAO.

- Baah-Ennumh, T. Y., & Adom-Asamoah, E. (2012). The Role of Market Women in the Informal Urban Economy in Kumasi. Journal of Science and Technology, 2(2), 56–67. https://www.ajol.info//index.php/just/article/view/81390

- Bank of Ghana (2007). Issues on wages and labor market competitiveness in Ghana. A Sector Study report prepared by the Research Department of Bank of Ghana for the deliberations of the Bank’s Board of Directors.

- Bekwai Municipal Assembly. (2014a). Bekwai Medium Term Development Plan 2014-2017. Bekwai-Ghana.

- Bekwai Municipal Assembly. (2014b). Bekwai Draft M & E Plan 2014-2017. Bekwai-Ghana.

- Bertulfo, L. (2011). Women and the informal economy, AusAID; https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/women-informal-economy-lota-bertulfo.pdf

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods (5th Ed ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. R. (1991). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century. IDS Discussion Paper 296. Institute of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Chant, S. (2012). Feminization of poverty. In Ritzer, G. (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of globalization. The Wiley Blackwell.

- Chen, M. A. (2008). Informality and Social Protection: Theories and Realities. IDS Bulletin, 39(2), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00441.x

- Chidoko, C., & Makuyana, G. (2012). The contribution of the informal sector to poverty alleviation in Zimbabwe. Developing Countries Studies, 2(9), 41–44. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/DCS/article/view/2965

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed. ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (2nd ed. ed.). Sage Publication.

- Dai, W. D., Mao, Z.E., Zhao, X.R., Mattila, A.S. (2015). ‘How does social capital influence the hospitality firm’s financial performance? The moderating role of entrepreneurial activities’, International Journal of Hospitality Management. Pergamon, 51 October 2015, 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2015.08.011

- Dehghani Pour, M., Barati, A. A., Azadi, H., & Scheffran, J. (2018). Revealing the role of livelihood assets in livelihood strategies: Towards enhancing conservation and livelihood development in the Hara Biosphere Reserve, Iran. Ecological Indicators, 94 November 2018 , 336–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.05.074

- Deribie, E. (2012). Women in the informal sector: Evidence from Southwestern Ethiopia. International Journal of Peace and Development Studies, 3(6), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJPDS12.015

- Devereux, S. (2001). Livelihood Insecurity and Social Protection: A Re-emerging Issue inRural Development. Development Policy Review, 19(4), 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7679.00148

- DFID (1999). Sustainable Livelihood Guidance Sheet. www.livelihoods.org [14th June 2017]

- Etim, E., & Daramola, O. (2020). The informal sector and economic growth of South Africa and Nigeria: A comparative systematic review. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6(4), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040134

- Fang, Y.-P., Fan, J., Shen, M.-Y., & Song, M.-Q. (2014). Sensitivity of livelihood strategy to livelihood capital in mountain areas: Empirical analysis based on different settle- ments in the upper reaches of the Minjiang River, China. Ecol. Ind, 38 March 2014 , 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.11.007

- Farrington, J., Carney, D., Ashley, C., & Turton, C. (1999). Sustainable Livelihoods in Practice: Early Applications of Concepts in Rural Areas. www.eldis.org [14th June 2017]

- Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO]. (2012). FAOSTAT, 2012.

- Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO]. (2013). FAOSTAT. 2013.

- Forkuor, D., Peprah, V., & Alhassan, A. M. (2018). Assessment of the processing and sale of marine fish and its effects on the livelihood of women in Mfantseman Municipality. Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 20(3), 1329–1346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9943-7

- Ghana Statistical Service (2016). 2015 Labour Force Report. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781005507.00007

- Ghana Statistical Service [GSS]. (2014). 2010 Population Census: District Analytical Report-Bekwai Municipality. In Ghana Statistical Service. Accra: Ghana 1–84.

- Ghatak, A., & Lalitha, N. (2016). Occupational Health Among Workers in the Informal Sector in India ( No. id: 10092). eSocialSciences.

- Gomez and Jones. (2010). Research Methods in Geography: A Critical Introduction (1st Edition). Blackwell Publishing.

- Hua, X., Yan, J., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Evaluating the role of livelihood assets in suitable livelihood strategies: Protocol for anti-poverty policy in the Eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Ecol. Ind, 78 July 2017, 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.03.009

- Ihuah, P. W., & Eaton, D. (2013). The Pragmatic Research Approach: A Framework for Sustainable Management of Public Housing Estates in Nigeria. Journal of US-China Public Administration, 10(10), 933–944. http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/30793/

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2018a). Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, Third Edition. International Labour Office. https://doi.org/10.1179/bac.2003.28.1.018

- Jahachandran, S. (2014). The Roots of gender inequalities in developing countries. A paper prepared for Annual Review of Economics.

- Kollmair and Gamper. (2002). The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach ( 9–20). Input Paper for the Integrated Training Course of NCCR North.

- Ministry of Food and Agriculture [MOFA]. (2012). Master Plan Study for the Palm Oil industry in Ghana. Ghana.

- Obodai, J., Adjei, P. O. W., Hamenoo, S. V. Q., & Abaitey, A. K. A. (2018). Towards household food security in Ghana: Assessment of Ghana’s expanded forest plantation programme in Asante Akim South District. GeoJournal, 83(2), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-017-9776-9

- OECD. (2002). Measuring the Non-Observed Economy. OECD Publications, Paris.

- Ofosu-Budu, K., & Sarpong, D. (2013). Oil palm Industry Growth in Africa: A value chain and smallholders study for Ghana. In A. Elbehri (Ed.), Rebuilding West Africa’s Food Potential, (pp. 349–389). FAO/IFAD .

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2012). Promoting Pro-Poor Growth: The Role of Empowerment, The organisation for Economic Cooperation Network on Gender Inequality.

- Osei- Asibey, E. (2014). Inequalities Country Report-Ghana. A report presented at the pan-African Conference on Tackling Inequalities in the Context of Structural Transformation in Ghana-Accra, Ghana, 20th-30th April 2014.

- Osei-Boateng, C., & Ampratwum, E. (2011). The informal sector in Ghana. FES Ghana.

- Peprah, J. A. (2012). Access to micro-credit well-being among women entrepreneurs in the Mfantseman Municipality. International Journal of Finance and Banking Studies, 1(1), 1–14. https://www.ssbfnet.com/ojs/index.php/ijfbs/article/view/443/403

- Peprah, V., Buor, D., & Forkuor, D. (2019). Characteristics of informal sector activities and challenges faced by women in Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1656383

- Polkinghorne, M., & Arnold, A. (2014). A Six Step Guide to Using Recursive Abstraction Applied to the Qualitative Analysis of Interview Data. Bournemouth University.

- Saikia, K. (2019). Impact of Socio Economic Factors on Women Work force Participation in Informal Sector of Assam. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering. 8(2S11), 4015–4020. September 2019. https://www.ijrte.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/v8i2S11/B15470982S1119.pdf

- Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis, IDS Working Paper 72. http://www.ids.ac.uk/ids/bookshop/wp/wp72pdf [14th June 2017].

- Sen, A. (1992). Inequality Reexamined. Oxford University Press.

- Sen, A. (1993). Capability and Well-Being. In M. Nussbaum & A. Sen (Eds.), The Quality of Life (pp. 1–32). Clarendon Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198287976.001.0001

- Singh, S. (2013). A case study on empowerment of rural women through micro entrepreneurship development. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 9(6), 123–126. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-096123126

- Sparks, D. L., & Barnet, S. T. (2010). The Informal Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: Out of the Shadows to Foster Socio-Economic Development. International Business and Economic Journal, 9(5), 1. https://clutejournals.com/index.php/IBER/article/view/563

- Su, F., Pu, X., Xu, Z., & Wang, L. (2009). Analysis about the relationship between livelihood capital and livelihood strategies: Take Ganzhou in Zhangye City as an example. Popul.

- Suarez, H. K., Haoaram, K., & Madhumitha, M. (2013). Measuring Environmental Externalities to Agriculture in Africa Case Study: Ghana Palm Oil Sector Audrey, FAO. Institute of Development Studies.

- Thorbecke, E. (2013). The Many Dimensions of Poverty International Conference August 29-31, 2005. UNDP International Poverty Centre: Brasilia. (pp. 3–19). https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230592407

- Tinuke, M. F. (2012). Women and the Informal Sector in Nigeria: Implications for Development. British Journal of Art and Social Sciences, 4(1), 1. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tinuke_Fapohunda/publication/258344067_Women_and_the_Informal_Sector_in_Nigeria_Implications_for_Development/links/0c960527fcdc14ca7e000000.pdf

- UNDP. (2017). Guidance Note: Application of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework in Development Projects.

- United Nations. (2018). Economic development.

- United Nations. (2019). Ending Poverty. Retrieved January 9, 2020, from United Nations website: https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/poverty/

- World Bank. (2009). The world bank annual report ( 64).

- Wu, Z., Li, B., & Hou, Y. (2017). Adaptive choice of livelihood patterns in rural households in a farm pastoral zone: A case study in Jungar, Inner Mongolia. Land Use Policy, 62 March 2017, 361–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.01.009