Abstract

An important role in deliberations on measures taken to eliminate the Sars-cov-2 flu pandemic is played by the definition of factors which contribute to containing its spread. These factors include social capital which contributes to mitigating the development of the flu pandemic by enhancing engagement and cooperation among people within various types of social groups, organizations and institutions. Taking the assumption that social capital can contain the spread of the flu pandemic facilitated formulating the purpose of the research, namely seeking the answers to the following research questions: What is the scope of social capital in Poland? To what extent do elements of social capital, i.e. social networks, trust and active citizenship, support measures taken to mitigate the development of the flu pandemic? The author applied the deductive and desk research methods. The research showed tangible relations linking the structural and cognitive capital with the SARS-CoV-2 incidence in specific provinces across Poland. The findings provide knowledge about the role of social capital in containing the spread of the flu pandemic. Social capital in all forms enhances the effectiveness of physical distancing and other protective behaviour. This paper highlights the importance of social networks and trust as key factors determining the development of the flu pandemic.

Public Interest Statement

In this paper, the research findings of the analysis of the relations between social capital and COVID-19 have been presented, which indicate that a high level of social capital constitutes significant safeguarding against the spread of the pandemic. The high level of social trust displayed towards other people, medical institutions, state institutions and the government itself strengthens the feeling of safety among people during COVID-19. In turn, active participation in multiple networks (family, groups of friends, neighborhood groups, social organizations, etc.) facilitates the mitigation of the spread of the pandemic, while the network members may count on support in cases of lockdowns and may acquire essntial information relating to the pandemic and preventive actions. Knowledge on the subject of the role of social capital in terms of mitigating the spread of COVID-19 may help to prepare actions that mitigate the danger of the recurrence of new pandemics.

1. 1.Introduction

Although the scale of the current SARS-CoV-2 flu pandemic is unprecedented in the 21st century in terms of the geographical reach and influence on human life, its course seems to be similar to the previous pandemics, and it is therefore worth investigating them. The H1N1 flu, announced by the WHO in June 2009, was the most severe one. At its early stage, there was no vaccine and it was uncertain whether one would be manufactured. Public health recommendations included mainly frequent hand washing, avoidance of the infected, staying away from crowds and following appropriate hygiene guidelines. Experience drawn from how people behaved during earlier flu pandemics show that prevention is hindered by three groups of factors: a) people underestimate the risk they expose themselves to, b) closing oneself in strict isolation as a means to protect others is against human nature, and c) people, often unwittingly, put themselves and others at risk by their actions (Bavel et al., Citation2020). Some help in minimizing the effect of these factors may be provided by a global campaign to promote public health, in particular hand washing, refraining from touching one’s face, wearing a face mask in public spaces and maintaining physical distance. Decision makers and health experts around the world, including WHO, have asked people to limit social contacts and follow hygiene and distance recommendations, appealing to the social responsibility of citizens. According to Bartscher et al. (Citation2020), this willingness to act collectively and pursue socially valuable goals is commonly referred to as social capital. It is reinforced by strong social trust and involvement in social networks. Other elements of social capital in the conditions of the flu pandemic are intimate relations and social ties focused around families, while also the extent of relations at a distance maintained by communication online (Bian et al., Citation2020).

The purpose of this paper is to search for relations between social capital and the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 flu in Poland. The author seeks answers to the following research questions: What is the scope of social capital in Poland? To what extent do elements of social capital, i.e. social networks, trust and active citizenship, support measures taken to mitigate the development of the flu pandemic? The research was of a qualitative nature. The author applied the desk research method to conduct a critical analysis of secondary data.

2. Social capital—definition context

The subject of social capital has become attractive for research projects seeking to explain social and economic processes, including public health, in the micro, mezzo and macro scale in the 21st century. There are different concepts of social capital—both at the conceptualization and operationalization levels. The large number of interpretations of this term arises from the differing research perspectives. An analysis of the most frequent approaches to social capital allows isolating six principal ways in which it is defined. Firstly, as the theory of networks which indicates that social capital is exactly a social network, which is the structure of relations between two or more actors (Coleman, Citation1988). Researchers identified various network mechanisms by means of which capital is generated. One of such is that of network ties that combine individual and organizational actors and serve as the channels for the flow of information, knowledge transfer, the learning of skills, social support and the exchange of resources (Granovetter, Citation1973; Podolny & Page, Citation1998). Secondly, as the theory of criteria, according to which social capital refers to the integrity, criteria and virtues embedded in a social network and the ability of people to undertake work towards common goals in groups and in organizations (Fukuyama, Citation1995). Thirdly, as the theory of resources, according to which, social capital is a set of real and potential resources that are associated with having a network of long-lasting social relations (Bourdieu, Citation1986; Lin, Citation1999). In the case of single entities, social capital enables them to benefit from the resources of other network members. These resources may take on the form of useful information, personal relations, or the ability to organize groups (Paxton, Citation1999). Fourthly, as the theory of ability which shows that social capital refers to the relation between the subject of an action and the society, and the ability to secure limited resources through such a connection (Portes, Citation1998). Fifthly, as the theory of the features of communities which include networks, norms, trust and social activity that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit (Putman, Citation1993). Sixthly, as features of communities—relationships, trust and norms—which allow the members of society to achieve common goals. Relationships in communities are based upon trust and are regulated by the norms of reciprocity and fairness (Woolcock, Citation1998). Moreover, various forms of social capital, including ties with friends and neighbours, are associated with the indicators of the mental well-being, such as self-evaluation and satisfaction with life (Bargh & McKenna, Citation2004; Helliwell et al., Citation2004).

A detailed analysis of approaches to defining social capital facilitates distinguishing its key elements including informal social relations, involvement in social networks, civic engagement (voluntary service), participation in the life of communities and organizations, social trust and norms of reciprocity. Therefore, social capital represents social relations, connections, shared values and mutual trust which allow individuals and social groups to cooperate and achieve their goals. In other words, these are an individual’s skills to engage and cooperate within social groups, organizations and various types of social institutions to achieve common goals.

3. Dimensions of social capital

Social capital can have different dimensions. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998) distinguished structural, cognitive and relational social capital. Structural social capital relates to the properties of the social system and of the network of relations as a whole; it is the network of people who an individual knows and upon whom he/she can acquire benefits such as information and assistance. It is the configuration and pattern of connections between people and includes the roles, rules and procedures. Strong ties promote and strengthen both the mutuality and the perspectives of long-term cooperation (Larson, Citation1993). As opposed to the structural dimension, the relational dimension does not relate to the structures of relations or connections between actors, but the fundamental basis of relations (Inkpen & Tsang, Citation2005). Relational social capital is the affective part as it describes relationships in terms of interpersonal trust, existence of shared norms and identification with other individuals. It plays out in behavioural attributes such as trustworthiness, shared group norms, obligations and identification. Cognitive social capital is the cognitive schemes and systems of meaning as exhibited in common vocabulary and narratives which facilities the understanding of actions taken by the actors. It combines resources which provide shared representations, interpretations, and systems of meaning among parties. Common goals and values develop thanks to the constant participation in the semantic process as various groups create a common perception (Krause et al., Citation2007, p. 531).

These dimensions are conceptual distinctions that are useful for analytic convenience. They should be treated as complementary, rather than contradictory. In practice, social capital involves complex interrelations between the three dimensions.

4. Social capital during the SARS-cov-2 flu pandemic

The increased level of interest among researchers in social capital in the area of public health shows that social capital can, to a large extent, explain the differences in community reactions, thus affecting the spread of COVID-19 (Bai et al., Citation2020; Ding et al., Citation2020; Bartscher et al., Citation2020; Bian et al., Citation2020; Borgonovi & Andrieu, Citation2020; Pitas & Ehmer, Citation2020; Yan & Lau, Citation2020; Di Loro et al.2,021; Kritzinger et al., Citation2021; Wu, Citation2021).

The sporadic studies into the connections between social capital and the COVID-19 flu pandemic do not show any relations between them. Studies into the first wave of the pandemic in Italy conducted by Bartscher et al. (Citation2020), showed that areas with high social capital demonstrated a lower mortality rate and a decreased mobility than areas with low social capital. Therefore, actions undertaken in communities with high social capital to eliminate the disease are more effective than those undertaken in communities with low social capital. In their study into the impact of social capital on people’s reactions to COVID-19 in counties across the USA, Ding et al. (Citation2020), found that social capital mitigates the spread of COVID-19 by greater engagement of individuals in achieving the common goal rather than through social networks and bonds. Research by Borgonovi and Andrieu (Citation2020), reveals that at the preliminary phase of the epidemic when the government restrictions were not yet implemented, the members of society of a higher level of trust and stronger norms of mutuality were more inclined to adhere to informal principles of avoiding contact in order to protect their family members. Likewise, the urban inhabitants of a higher level of social capital reacted to COVID-19 faster and recovered more quickly (Bartscher et al., Citation2020). In turn, Bai et al. (Citation2020), found that U.S. counties with higher levels of civic engagement are more willing to maintain social distancing, whereas counties with denser social networks show poorer social distancing behaviour. This suggests that social capital can significantly affect people’s reactions to COVID-19. On the one hand, the norms of civic engagement make it easier to cooperate and make sacrifices for the common good, leading to greater compliance with social distancing restrictions. On the other hand, social networks increase the level of social interactions, making it more difficult to practice social distancing. However, Bian et al. (Citation2020), discovered that social capital in the form of family ties is the best source of social capital that helps the Chinese in the fight against the pandemic COVID-19. Research indicates that intimate relations within families and contacts at a distance jointly facilitate and strengthen the behavioural reactions of entities towards COVID-19 and together generate effective mental and physical counter-epidemic actions.

However, conclusions from the research do not facilitate answering the question about the mechanism of the impact of social capital on the spread of COVID-19. It is necessary to conduct further studies into the relations between social capital and the flu pandemic.

4.1. Structural and relational social capital

Structural and relational social capital are key elements that support the fight against the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Structural social capital is a network of people who a particular person knows and who he/she can count on, while also who he/she may acquire important information from. The attribute of structural social capital is the number of connections with other people and its strength (Taylor, Citation2000). Its most significant advantages are the ease of access to partners who possess the sought after, or specialized knowledge (Andrews, Citation2010). A further advantage is that of providing people with the possibility of participating in beneficial collective actions, which enable the reduction of the costs of transactions and the improvement of the social learning process (Uphoff & Wijayaratna, Citation2000).

Social networks can increase the dissemination of attitudes which contribute to the development of the pandemics, but they can also prevent such behaviour. An important role in this process is played by central actors (ego) who have the largest number of contacts in the network and are often among the first people to become infected. Central actors can infect other members of the network, or can become infected faster than people from the periphery. At the same time, however, central actors can contribute to mitigating the disease by promoting positive safety-related behaviour such as, e.g., hand washing, physical distancing and dissemination of positive information about vaccines. The implementation of health-conscious attitudes by directing them at central actors in networks has a positive impact on the propagation and effectiveness of those attitudes, as network members follow the behaviour of the central actor. Strong bonds in social networks are crucial for the dissemination of positive behaviour both online and in real-world social networks (Bond et al., Citation2012). One can therefore harness the influence of central actors on the behaviour of other social network members by sending them messages on recommended behaviour during the pandemic.

Relational social capital is the dimension of social capital which relates to personal relations, such as trust, respect and even friendship (Gooderham, Citation2007). This occurs in terms of behavioural attributes, such as credibility, common group norms, obligations and identification (Davenport & Daellenbach, Citation2011). Relational social capital is part of affective capital as it describes relations in categories of interpersonal trust, the existence of common norms and the identification with other people.

Relational capital in the form of trust and norms plays an important role in the fight against infectious diseases. An analysis of studies into pandemics shows that trust is the key factor facilitating the fight against the virus (Meredith et al., Citation2007). During a pandemic, employees of medical institutions should build people’s trust in them in order to reinforce their message regarding necessary changes in behaviour, e.g., refraining from social contacts, compliance with the rules of quarantine or voluntary reporting for medical tests if symptoms of the disease appear. Since the nature and size of the population covered by such actions make positive behaviour difficult to enforce, trusted local community leaders need to engage to reinforce the aforesaid messages and help build the trust needed to trigger behavioural changes. Studies into the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014–2015 suggest that attracting local actors to build engagement and trust in healthcare officers can enhance the effectiveness of actions in the area of public health (Bavel et al., Citation2020).

In order to limit the spread of the virus, it is very important that information about the risk can convince the public to comply with the recommendations of medical services at the early stages of the crisis. The public must first trust the health experts and representatives before following their recommendations. Numerous studies into the H1N1 flu pandemic of 2009 show that trust plays a major role as a predictor of social behaviour (Freimuth et al., Citation2014).

4.2. Trust and fake news about COVID-19 in social media

Trust is affected by the quality of communication between government representatives and citizens. Disruption of this communication contributes to the emergence of fake news about COVID-19 in social media which undermines the trust in governments and medical institutions. New information appears about new magical medicines, therapies, while also conspiracy theories. Despite efforts made by social media owners to stop the spread of misinformation, fake news about the coronavirus continue to circulate around the world (Frenkel et al., Citation2020). According to researchers, the prevention of this phenomenon requires understanding the substance and structure of fake news. They suggest that the origins of public misinformedness and polarization are more likely to lie in the content of ordinary news or the avoidance of news altogether as they are in overt fakery (Allen et al., Citation2020). Methods of counteracting this phenomenon include exposure of fake news by proliferation of true facts. The fight against misinformation requires expertise coming from an impartial source and exposure of inconsistencies through causal explanations (Swire & Ecker, Citation2018). Government representatives, medical institutions, health officers and the mass media have an important role to play in reducing the trust in fake news about COVID-19 by pursuing the appropriate information policies regarding the course of the pandemic, methods of containing the incidence rate and efficacy of treatment methods. A high level of social capital in society supports such information policies, lending credence to its media content.

4.3. Relations of capital offline and online during pandemic of COVID-19

An important role in social capital during the pandemic is played by various digital media (e.g., telephone, chat, e-mail, social media) which let people communicate with others outside their homes. These forms of media have taken over the function of bridging and bonding people within their communities. Although digital communications, particularly social media, most likely generate social capital, one must consider some important reservations. Firstly, there are no studies into the role of social media in creating social capital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies were conducted when people had access to both online and offline communication. Secondly, online social capital in social media and offline face-to-face social capital are separate, albeit interconnected, phenomena. Findings show that social capital in social media differs empirically from face-to-face social capital (Gil de Zúñiga et al., Citation2016). Online social capital has a stronger impact on offline social capital than the other way round. In other words, the way in which people establish contacts, promote social values and try to discuss their problems within their Internet communities is transferred to and continued in the real world, i.e. offline. However, value sharing and mutual assistance in offline communities are not reflected in the behaviour of virtual communities.

During the widespread restrictions and bans associated with counteracting the flu pandemic, social capital offline has encountered a multitude of obstacles that had not existed before. A restriction on the participation in social networks has been implemented that is associated with the necessity to maintain a social distance and limit direct contacts. In this situation, social capital online becomes significant. A significant role in its development is played by the tools of communication with the aid of digital media (Ellison et al., Citation2007). The Internet has become an important medium that mediates between people as making interactions online complement, or in many cases replace personal interactions, thus easing all the losses associated with the restriction of social contacts. Interactions online have a positive impact on social interactions, engagement and social capital (Kavanaugh et al., Citation2005).

A large role is played by the network platforms which support loose social ties, thus rendering it possible for users to create and maintain greater and more dispersed networks of relations from which benefits may be accrued from the inherent resources (Donath & Boyd, Citation2004). The Internet ensures people an alternative way of connecting with others that share the same interests, or who strive towards the same goals (Ellison et al., Citation2006). These new relations may cause the growth of social capital (Boase et al., Citation2006). For instance, the intensive use of Facebook has a positive impact on the accumulation of social capital, particularly the bridging social capital type (Ellison et al., Citation2007).

During the course of the pandemic, Internet platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram fulfil an important role in the building of trust towards the medical services, by availing of their large range to spread selected information that is based on facts and the active removal of potentially damaging misinformation. For example, in the information media of Wikipedia, Google, Twitter or YouTube, the Poles acquired knowledge about the current situation and threats associated with Covid-19. An important action was to search for the confirmation of the sensibility or necessity to use measures of personal protection and adherence to mitigatory behaviour (Jarynowski et al., Citation2020).

A significant task for the network media is to encourage action to be taken with the aim of limiting the spread of the virus, or help for those infected. These actions are undertaken by both social organizations, as well as public institutions. Social organizations avail of network media to propagate safe behaviour during the course of the pandemic. One of the behavioural patterns propagated is the limitation of personal contacts on the part of elderly people. Research conducted by Nadobnik (Citation2021), relating to the role of network media in terms of the activation of elderly people in the period of the pandemic COVID-19 indicates multifaceted action. One of these is preventing senior citizens from leaving home thanks to the propositions of various types of activity in the cyberspace, e.g., virtual visits to museums, the possibilities of virtual walks around national parks, participation in plays online, while also ensuring the possibilities of having a discussion. Among the most popular slogans were those as follows: #stayathome; Don’t get off the couch! or Art will come to you! As a result, the Internet has become a tool for active deactivation. Likewise, public institutions avail of network media in order to propagate safe behaviour. For instance, the City Office of Warsaw avails of social media with the aim of informing inhabitants about the current events and changes evoked by the pandemic virus. Posts placed on Facebook and Twitter inform the citizens about the opening of new vaccination points in the area of Warsaw, while on the YouTube platform films are released on the subject of aid for the city dwellers during the time of the pandemic (Mikucki, Citation2021).

Analysis of the relations between social capital offline and online gives rise to several conclusions. Firstly, changes are observed in the functioning of social capital, particularly capital offline. The physical isolation has become a factor that increases the negative sense of coping with the pandemic situation and reduces the subjective well-being. The function of creating ties has taken on great importance. Staying at home amongst one’s family has become the most effective method of defence against infections as opposed to wearing masks and washing hands (Yan et al., Citation2020). Secondly, social capital online based on social media has also taken on great importance. This capital may help defensive action by informing people about the negative effects of the pandemic and propagating behaviour that protects health. The appropriate management of information about the pandemic plays an important role in social media, which is featured by excessive untrue information or misinformation in the digital and physical world during the course of the pandemic (Eysenbach, Citation2020). Infodemic may cause uncontrolled panic and gradually worsen the stigmatization of people in the epicentre of the epidemic (Davis et al., Citation2020). Infodemic causes the lack of trust towards the health service bodies and also weakens the reactions in the sphere of public health (Muñoz-Sastre et al., Citation2021). The management of infodemic requires the monitoring of information about COVID-19 that includes inaccurate data, e.g., fake news. Thirdly, social capital online is built on the basis of digital communication tools that support human activity during the pandemic. It encourages behaviour that is safe for our health and advocates vaccinations. Fourthly, the prevention of the spread of the pandemic involves the strategy of building social capital offline and online in periods of social isolation with the use of the tools of digital communication.

5. Methods

The study into the relation between social capital and the SARS-CoV-2 incidence rate was based on social capital indicators (Czapiński & Jerzyński, Citation2016; Statistics Poland, Citation2020) and data on the incidence rates in Poland as of 20 October 2020 (Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, Citation2020). The author applied the deductive and desk research methods to conduct a critical analysis of secondary data.

The research involved the use of two variables: the susceptibility to COVID-19 and social capital. Establishing the indicators for the varying susceptibility to COVID-19 is difficult as the impact may have varied factors, among others, differences in demography, employment, the size of cities, social networks, the social dynamics or individual behaviour (Stier et al., Citation2020). In subject-related literature, it is possible to find an attempt to establish these indicators. For example, the frequency of infection and deaths caused by COVID-19 among elderly people in Brazil, while also their relation with the contextual variables were placed under analysis. The indicators of accumulated maturity were assumed, while also the generally accumulated mortality and the accumulated mortality among elderly people. Among the contextual variables, the provision of health services, while also specialists, as well as demographic factors, income and developmental factors were all taken into account (Barbosa et al., Citation2020).

In the research on the relations between social capital and morbidity in terms of COVID-19 in Poland, the author took the dependency variables associated with the frequency of infections in terms of COVID-19 into account, namely: the accumulated coefficient of morbidity per 10,000 people (the accumulated number of cases of infections from COVID-19 in a province per 10,000 people) and the accumulated indicator of mortality per 10,000 people (the accumulated number of deaths of people sick with COVID-19 in a province per 10,000 people). The indicator of morbidity serves to describe the probability or risk of the occurrence of the infection in a specified population in a specified period (Haley et al., Citation1985). An important feature of these indicators is the fact that it is possible to relate to the longer time frames by simply accumulating them over the course of time. The most interesting indicators of accumulated morbidity are with relation to the entire history of the pandemic, counted from the accepted date of the beginning of the pandemic (this is usually the day of the systematic registration of the daily cases of infections with Covid-19) up to the current day (Di Loro et al., Citation2021).

Independent variables in research are the accumulated indicator of social capital. The operationalization of the term social capital was conducted on the basis of the concept of R. Putman, who defines it as the following: “ … features of social organisation, such as trust, norms, and networks that can improve the efficiency of society by facilitating coordinated actions” (Putman, Citation1993, p. 167). Social capital relates to the participation in social networks, civic engagement associated with the participation in voluntary organizations and social trust.

The author adopted provinces as the unit of the analysis. The choice of provinces as a unit for analysis is the consequence of the significant social differentiation, as well as cultural and historical differentiation of the regions in Poland. In provinces that are strongly urbanized, which are situated in the central parts of Poland (the provinces of mazowieckie, śląskie, opolskie, łódzkie) in which there is a prevalence of industry and services, there is a dominant urban model of social life. This is associated with such features as a higher level of education, greater economic activity of the inhabitants and a predominance of liberal values. In turn, in provinces located in the eastern and southern regions of Poland (lubelskie, warmińsko-mazurskie, podkarpackie, małopolskie), there is a prevalence of agricultural activity and a rural model of social life based on, among others, family ties, neighbourly ties, while also the incumbency, while also the conservatism of the inhabitants and the attachment to tradition. In provinces located in the western and northerly parts of Poland (dolnośląskie, wielkopolskie, zachodniopomorskie, pomorskie, kujawsko-pomorskie), in which there are both urbanized areas, as well as agricultural areas, there is a prevalence of a mixed model of social life.

6. Results

6.1. Level of social capital in Poland

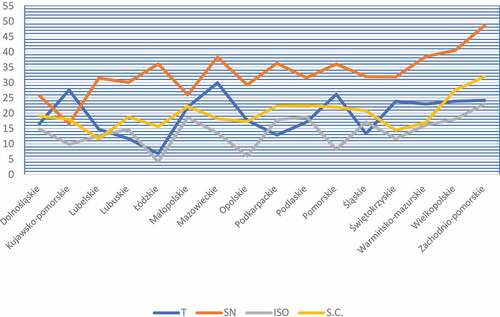

The analysis of data provided in shows that the level of social capital in Poland is relatively low (SC = 19.91), with regional differences across the country. The highest level was observed in zachodnio-pomorskie province (SC = 31.90), followed by wielkopolskie (SC = 27.46), podlaskie (SC = 22.43), podkarpackie (SC = 22.32), pomorskie (SC = 21.92) and małopolskie (SC = 22.17) provinces. The lowest level was observed in lubelskie (SC = 11.60), świętokrzyskie (SC = 14.39) and łódzkie (SC = 15.65) provinces. As can be seen, the territorial analysis of social capital shows significant differences in its levels in the respective provinces.

Figure 1. Social capital and his elements in respective provinces of Poland.Source: Elaborated on the basis of: Czapiński and Jerzyński (Citation2016).Notes: T- Trust, SN—Membership in social networks of 10 or more people ISO—Involvement in social organisations, SC—Generalised social capital indicator.

A detailed analysis of social capital indicators facilitates capturing some differences in their levels, with the social network indicator reaching the highest value. Networks of 10 or more people were accepted for analysis as they involve contacts extending beyond one’s closest relatives, which is relevant for the spread of the flu virus. The highest values of the network participation indicator were observed in zachodnio-pomorskie (SN = 48.55), wielkopolskie (SN = 40.48) and warmińsko-mazurskie (SN = 38.37) provinces, whereas the lowest values were found in kujawsko-pomorskie (SN = 16.54), dolnośląskie (SN = 25.69) and małopolskie (SN = 25, 97) provinces.

The trust indicator was the highest in mazowieckie (T = 29.87), kujawsko-pomorskie (T = 27.55), pomorskie (T = 26.13) and zachodnio-pomorskie (T = 24.18) provinces, and the lowest in łódzkie (T = 6.8), lubuskie (T = 11.67) and podkarpackie (T = 12.87) provinces.

The involvement in social organizations indicator (ISO) was the highest in zachodnio-pomorskie (ISO = 22.97), podlaskie (ISO = 18.71) and małopolskie (ISO = 18.57) provinces, and the lowest in łódzkie (ISO = 4.1), opolskie (ISO = 6.0) and kujawsko–pomorskie (ISO = 9.82) provinces.

6.2. Analyses of relations between social capital and the incidence rate and the mortality rate

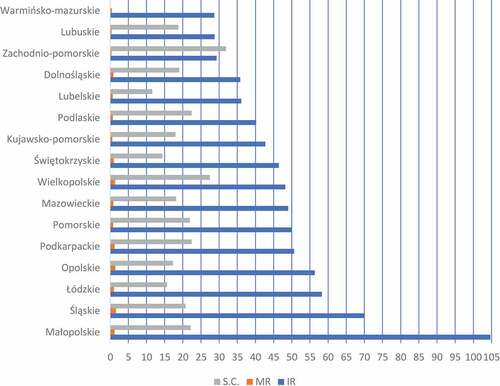

For the purpose of this paper, it is important to seek the relations between social capital and the incidence rate (IR- incidence per 10,000 province residents) and the mortality rate (MR—deaths due to COVID-19 per 10,000 province residents). These relations are shown in . A notable positive impact was observed in the following provinces: zachodniopomorskie (SC = 31.9, IR = 29.31, MR = 0.35), podlaskie (SC = 22.43, IR = 40.20, MR = 0.76), dolnośląskie (SC = 19.02, IR = 35.78, MR = 0.86), where relatively high social capital is accompanied by low incidence and mortality rates. However, a relatively high social capital was noted in małopolskie (SC = 22.17, IR = 104.77, MR = 1.19) and śląskie (SC = 20.77, IR = 69.98, MR = 1.58), which failed to limit the flu infection as the incidence and mortality rates were the highest in those regions. A different situation was observed in łódzkie province (SC = 15.65, IR = 58.27, MR = 1.00), where a low level of social capital affected a high incidence rate.

Figure 2. Social capital and COVID-19 incidence and mortality indicators in respective provinces of Poland.Source: Elaborated on the basis of: Czapiński and Jerzyński (Citation2016), Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Citation2020), and Statistics Poland (Citation2020);Notes: SC—Generalised social capital indicator, IR—incidence per 10,000 province residents, M R—deaths due to COVID-19 per 10,000 province residents.

In conclusion, the analysis of the relations between the level of social capital and incidence rate confirmed that these variables are correlated in most provinces. However, the correlation is not linear.

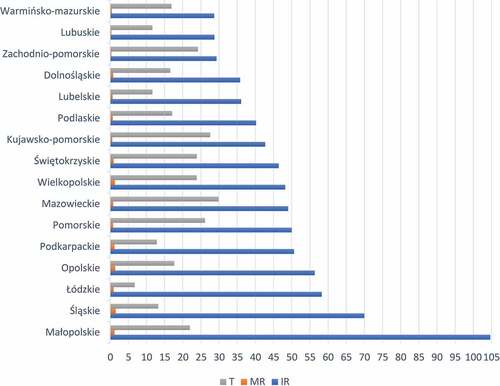

A detailed analysis of the relations between the social capital elements and the incidence and mortality rates facilitates observing certain significant differences. A number of researchers indicate that a high level of cognitive capital contains the spread of the COVID-19 flu pandemic (Jalan & Sen, Citation2020). The author found some connections which also confirm these research findings in the analysis of the relations between the trust and incidence rates and mortality rate in Poland []. A relatively low level of COVID-19 incidence rates were reported in provinces with the highest levels of trust, i.e. in zachodnio-pomorskie (T = 24.18, IR = 29.31, MR = 0.35), kujawsko-pomorskie (T = 27.55, IR = 42.69, MR = 0.60), mazowieckie (T = 29.87, IR = 49.04, MR = 0.60) and pomorskie (T = 26.13, IR = 50, MR = 0.84). Likewise, a relation was found to exist between a low level of trust and high incidence rates in łódzkie (T = 6.8, IR = 58.27, MR = 1.58) and śląskie (T = 13.3, IR = 69.98, MR = 1.58) provinces.

Figure 3. Trust and COVID-19 incidence and mortality indicators in respective provinces of Poland.Source: Elaborated on the basis of: Czapiński and Jerzyński (Citation2016), Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Citation2020), and Statistics Poland (Citation2020);Notes: T- Tust, IR—Incidence per 10,000 province residents, MR—deaths due to COVID-19 per 10,000 province residents.

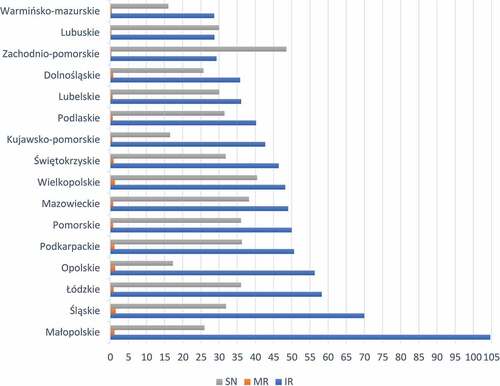

In the next research step, the author analysed the relations between the involvement in social networks and COVID-19 incidence rates []. Relatively low incidence rates were observed in provinces where involvement in social networks was the highest. This is true for the following provinces: zachodnio-pomorskie (SN = 48.55, IR = 29.31, MR = 0.35), warmińsko-mazurskie (SN = 38.37, IR = 28.65, MR = 0.47) and mazowieckie (SN = 38.25, IR = 49.04, MR = 0.87). In the case of małopolskie province, a relation was found between the level of social network involvement (SN = 25.97) and the highest incidence rate (IR = 104.67) and mortality rate (MR = 1.19). The author’s analysis of the effect of the size of social networks on incidence rates in the respective provinces seems of interest []. The author assumed four categories of networks depending on their size, i.e. 5–9 people, 10–19 people, 20–49 people, and 50 people or more. The greatest number of respondents declared involvement in small social networks of between 5 and 9 people, and networks of 10–19 people. The observation of relations between the size of a network and the incidence rate facilitates identifying certain connections. In some provinces, a positive relation between involvement in networks of 5–9 people and a low incidence rate, in particular in lubelskie (SN = 36.36, IR = 36.10, MR = 0.70), dolnośląskie (SN = 35.19, IR = 35.78, MR = 0.86), warmińsko-mazurskie (SN = 32.56, IR = 28.65, MR = 0.47) and kujawsko-pomorskie (SN = 35.43, IR = 42.69, MR = 0.60). That positive relation is slightly lower for networks between 10 and 19 people, as in warmińsko-mazurskie (SN = 26.74, IR = 28.65, MR = 0.47), zachodnio-pomorskie (SN = 24.44, IR = 29.31, MR = 0.35) and lubelskie (SN = 20.66, IR = 36.10, MR = 0.70) provinces. For networks of 20 to 49 people, a positive relation between the network and the incidence rate can be observed mainly in zachodnio-pomorskie (SN = 21.11, IR = 29.31, MR = 0.35), lubuskie (SN = 13.33, IR = 36.10, MR = 0.36) and kujawsko-pomorskie (SN = 12.60, IR = 42.69, MR = 0.60) provinces. As regards large networks of 50 people or more, a positive relation was observed in inter alia, warmińsko-mazurskie (SN = 4.65, IR = 28.65, MR = 0.47) and kujawsko-pomorskie (SN = 4.17, IR = 48.22, MR = 0.60) provinces.

Table 1. Involvement in social networks and COVID-19 incidence rate in Poland by province

Figure 4. Social network and COVID-19 incidence and mortality indicators in respective provinces of Poland.Source: Elaborated on the basis of: Czapiński and Jerzyński (Citation2016), Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Citation2020), and Statistics Poland (Citation2020);Notes: SN—Membership in social networks of 10 or more people, IR—Incidence per 10,000, MR—Deaths due to COVID-19 per 10,000 province residents.

Summing up, this study has demonstrated that social networks are an important factor which affects the scale of incidence and mortality, with a significant role played by the size of the network. Involvement in social networks composed of fewer people limits the COVID-19 incidence.

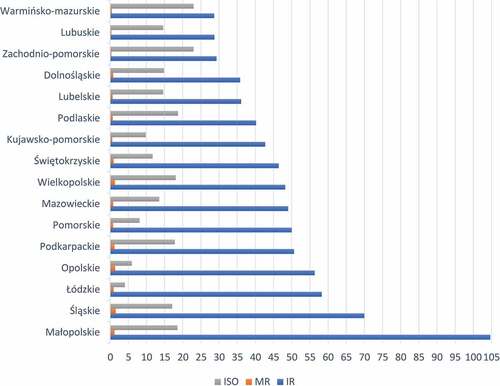

Involvement in social organisations has a limited impact on the incidence level in Poland. Analysis of data provided in shows that a positive relation between a relatively high level of social activity and a low incidence rate in some provinces, i.e. zachodnio-pomorskie (ISO = 22.97, IR = 29.31, MR = 0.35), podlaskie (ISO = 18.71, IR = 40.20, MR = 0.76), warmińsko-mazurskie (ISO = 16.04, IR = 28.65, MR = 0.47). The exception is małopolskie province, where there was a negative relation between a high level of social activity (ISO = 18.57) and a high incidence rate (IR = 104.67) and mortality rate (MR = 1.19). The lowest level of social activity was observed in łódzkie province (ISO = 4.10), where there was a relatively high incidence rate (IR = 58.27) and mortality rate (MR = 1.00), while also in opolskie province (ISO = 6.00, IR = 56.34, MR = 1.42).

Figure 5. Involvement in social organisations and COVID-19 incidence and mortality indicators in respective provinces of Poland.Source: Elaborated on the basis of: Czapiński and Jerzyński (Citation2016), Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (Citation2020), and Statistics Poland (Citation2020).Notes: ISO—Involvement in social organisations, IR—Incidence per 10,000 province residents, MR—Deaths due to COVID-19 per 10,000 province residents.

The study into relations between social capital indicators and COVID-19 incidence rate in Poland showed the strongest relation in the case of relational and structural capital.

7. Discussion

Analysing the measures taken to limit the transmission of the COVID-19 flu virus, one can say that maintaining strict physical distancing and wearing face masks play a key role in flattening the epidemic curve. The level of social capital affects the prevalence of behaviour relating to social distancing during pandemics. For example, during the H1N1 pandemic in 2008, social capital (measured by the level trust in the government, interpersonal contacts and the sense of mutual obligation, reciprocity and social coherence) had a significant effect on the intention to become vaccinated, maintain physical distance, wash hands and wear a face mask (Bond et al., Citation2012).

The findings of the territorial studies into the relations between the elements of social capital and COVID-19 incidence rates in Poland show that social capital in various forms and at various levels can affect the spread of Covid-19. It was demonstrated that relational capital with its important element of trust, affects the flu incidence rate. Provinces with the highest level of social trust showed low COVID-19 incidence rates. This relation was also confirmed for situations where low trust levels affected high incidence rates. The identification of this relation facilitates formulating a conclusion that social trust in other people, trust in medical institutions, state agencies and in the government is favourable towards measures taken to contain the spread of the COVID-19 flu virus. An important role in this process is played by trust in the government which should provide information on risks related to becoming infected, while also the existence and effectiveness of preventive actions and measures, while also the safety and efficacy of vaccinations. The information should be gathered and presented in close cooperation with local health services, healthcare institutions and media in order to ensure effective social coverage. This would facilitate building and maintaining government trust and increasing compliance with the recommended measures that can contain the spread of the disease (Van der Weerd et al., Citation2011).

However, in practice trust shown to the government has an impact on the reactions of people in varying ways in terms of the health crisis evoked by Covid-19. For example, in Austria the high level of trust in the government was closely related to the perception of threats to their health (Esaiasson et al., Citation2020; Schraff, Citation2020), while also the evaluation of the results of the policies of the government (Bol et al., Citation2021). However, in France, it was observed that the low level of trust in the government and the high level of polarization reduced the chance of the citizens uniting behind their government and accepting the restrictions evoked by the lockdown (Kritzinger et al., Citation2021).

Another important function of trust during the course of the flu pandemic is the minimization of anxiety with regard to death. The flu pandemic brings excessive deaths to patients, which evokes an increasing level of the fear of death. The problematic issue of anxiety caused by the COVID-19 virus is seldom undertaken. Few research projects reveal that a significant impact on the level of anxiety prior to death as a result of COVID-19 is created by neuroticism and the level of stress (Murphy & Moret-Tatay, Citation2021). Anxiety over death is positively correlated with stress and a neurotic personality. A way to mitigate anxiety over death is re-education with regard to stress (Pérez-Mengual et al., Citation2021). The terror management theory (TMT) may be helpful in terms of explaining anxiety over death, which indicates that in times during which the consciousness of death appears, entities have the tendency to strengthen their feeling of values with the aim of mitigating anxiety over death (Pyszczynski et al., Citation1999, Citation2020). This anxiety may lead to defensive reactions that are harmful to, or indeed useful in terms of health protection, which depends on how the dimension of trust in social relations is managed (Testoni et al., Citation2018). Trust is a significant factor that mitigates anxiety over death. There must be trust between the patients and the doctors that arises from the level of faith in the effectiveness of the methods applied by the medical doctors. As Michelle M. Kittleson states (Kittleson, Citation2021, p. 1371), “The fear and uncertainty of COVID-19 may strain the patient-physician bond, but it need not break it. Patients need to know that we, as physicians, will not abandon them if we disagree. When this pandemic ends, our trust will be stronger for it” This growing area of research indicates that there is a need for further research on the management of trust in the context of the affective needs of protection from death as a result of COVID-19.

In his study, the author also demonstrated that there was a relation between structural capital and the incidence rates in respective provinces. It was found that involvement in many social networks enhances actions aimed at containing the spread of the flu, as members of the network can count on assistance and obtain more information on the pandemic and protective behaviour. It was demonstrated that in provinces with the highest level of engagement in social networks the COVID-19 incidence rate was low. This was confirmed by the case of a province with a low level of social network engagement and a high incidence rate.

Engagement in social organisations had the relatively lowest impact on COVID-19. Since the study demonstrated that a high level of social activity was present both in the case of low and high incidence rates, one can say that social activity did not have a clear impact on flattening the COVID-19 development curve.

Based on the findings, one can conclude that building relational and structural capital can greatly support the fight against the flu pandemic. Wu arrived at a similar conclusion (Wu, Citation2021). Studying the impact of social capital on COVID-19 in China, he found that cognitive social capital in the form of trust and norms has a stronger impact than structural capital, which suggests that cooperation and sacrifices for the common good, promotion of social acceptance and compliance with control measures significantly affect reactions to COVID-19.

Summing up, it has been demonstrated in this paper that social capital can contain the spread of the flu pandemic. During the course of the pandemic, all forms of social capital help activities in terms of mitigating the spread of the virus. The presence of the structural and relational social capital may constitute a safety net for the members of society, albeit social capital ensures the greatest benefits only when all its forms are present in society. The lack of equilibrium between them may cause the reduction of the efficiency in anti-pandemic activities. An excessively low level of structural capital may have a negative impact on the effectiveness of the fight against the virus. This was noticeable during the first wave of infections with Covid-19 when the regional authorities, the government and economic organisations competed with each other for the possibility of acquiring the means of personal protection, namely, N95 masks, face shields, as well as equipment serving the saving of lives, e.g., oxygen machines.

Likewise, an excessively low level of relational social capital may be an obstacle as the members of society are unable to unite and engage in joint action. As a result of the necessity to apply restrictions in the form of physical distance and isolation, the low level of this type of capital is a significant barrier in terms of the functioning of society. People affected by the disease are forced to undergo quarantine, which is associated with the limitation of the activities of everyday life, whereby the majority of time is spent at home separated from the majority of normal interactions face to face with everyone, with the exception of the members of the immediate household (if such exist). Random interactions with other people, which would usually take place in schools, workplaces, parks and other public places that maintain relational capital are the unintended victim of these practices. The medium serving the maintenance of social relations may become that of the Internet. On the one hand, social network platforms may help in terms of making new ties and maintaining old social relations with people who have become infected with COVID 19. On the other hand, they may help preventive action by informing people of behaviour that protects the health.

Simultaneously, the key methods of reducing the risk of transmitting the infection and development of the disease are vaccinations and behavioural techniques, namely, the reduction of contacts (e.g., quarantine, physical distancing and the restriction of mobility), while also the reduction of the probability of infections thanks to the application of the means of personal protection, promotion of a healthy lifestyle; shortening the duration of morbidity (e.g., treatment, tracking contacts and performing tests on the presence of coronavirus).

However, the effectiveness of the behavioural techniques is dependent on the adherence of society to the recommendations formulated by the central and local authorities. With regard to this fact, valid knowledge is necessary, what the attitudes and opinions of society are at a given moment and what the potential and adaptation effects are with regard to behavioural restrictions. Research indicates that the actions of forcing the closure of schools and changes in the forms of work from a stationary type to a remote one in terms of companies and the physical distancing of people had the greatest impact on the reduction of the dynamics of infections (Kędzierski et al., Citation2020). Simultaneously, such actions give rise to opposition in parts of society, e.g., the formation of the anti-vaccine movement.

8. Limitations of the study and future developments

The author of this paper wishes to highlight the limitations regarding the use of the findings of the present study into the impact of social capital on the development of the COVID-19 flu pandemic. Application of the desk research method to analyse secondary data was meant to outline the role of social capital in countering the spread of the flu pandemic and become a starting point for deeper studies into relations between public health and various types of social capital. Such studies are needed to develop a strategy for building social capital that will support the fight against infectious pandemics in times of social isolation, e.g., by using means of digital communication and social media.

In order to improve the precision of predictions, in future research it is possible to take account of the other factors, i.e. demographic variables, while also social and health variables. Despite the methodological limitations as a consequence of the application of the desk research method, the research findings lead to important conclusions that are potentially useful in practice. They illustrate that the creation of social capital is an important safeguard against future pandemics. Knowledge on the subject of the role of social capital in terms of mitigating the spread of the COVID-19 virus may facilitate the development of approaches that would mitigate the future reoccurrence of the flu pandemic. For instance, in the case of a new epidemic or pandemic, or perhaps the reoccurrence of COVID-19, such methods as social distancing, social trust in the institutions of health protection, participation in the social networks, remote working, may all strengthen the reactions to the preliminary phases of the danger.

Investing in social capital may help in terms of coping with the negative shock and maintaining a level of mutual ties and good level of well-being. Further research is essential in order to comprehend the evolution of social capital and the specific mechanisms by means of which there is an impact on the development of an individual during health crises.

With the aim of more precise predictions of the impact of social capital on the restriction of development of the pandemic, a more unequivocal definition of the way we conceptualize social capital is required due to its multifaceted and multi-level nature. Future research should be based on reliable quantitative and qualitative data on the subject of the roles of social capital in the fight against COVID-19.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Felicjan Bylok

Felicjan Bylok is an Full Professor of sociology. He’s the head of the Department of Sociology, Psychology and Communication of Management at the Faculty of Management of the Czestochowa University of Technology. His scientific interests is as follows: the social capital and trust, Human Resources Management and the sociology of organization. He is also the author and co-author of numerous monographs and over 180 articles in journals in the field of sociology of organization and management, social capital and trust. The problematic issue of social capital in the fight against COVID-19 is significant due to the potential possibilities of restricting the risk of the spread of the virus. In this research, I wanted to analyse the connections between trust, participation in social networks and social activity, while also the level of infections and mortality associated with COVID-19. A further research project shall relate to becoming familiar with the mechanism of the impact of social capital on the behaviour of an individual during health crises.

References

- Allen, J., Howland, B., Mobius, M., Rothschild, D., & Watts, D. J. (2020). Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem. Science Advances, 6(14), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay3539

- Andrews, R. (2010). Organizational social capital, structure and performance. Human Relations, 63(5), 583–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709342931

- Bai, J., Shuili, D., Wang, J., & Chi, W. (2020). The impact of social capital on individual responses to COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from social distancing. 39p. SSRN Working Paper 3609001. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3609001.

- Barbosa, I. R., Galvão, M. R. R., de Souza, T. A., Gomes, S. M., de Almeida Medeiros, A., & de Lima, K. C. (2020). Incidence of and mortality from COVID-19 in the older Brazilian population and its relationship with contextual indicators: An ecological study. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria E Gerontologia, 23(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-22562020023.200171

- Bargh, J., & McKenna, K. (2004). The Internet and social life. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 573–590. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141922

- Bartscher, A. K., Seitz, S., Siegloch, S., Slotwinski, M., & Wehrhöfer, N. (2020). Social capital and the spread of COVID-19: Insights from European countries IZA DP. http://ftp.iza.org/dp13310.pdf

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., … Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behavior, 4(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

- Bian, Y., Miao, X., Lu, X., Ma, X., & Guo, X. (2020). The emergence of a COVID-19 related social capital: The case of China. International Journal of Sociology, 50(5), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2020.1802141

- Boase, J., Horrigan, J. B., Wellman, B., & Rainie, L. (2006). The strength of internet ties. Pew Internet and American Life Project. Pew Internet & American Life Project. January 25. Washington. Retrieved May 20, 2006 from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Internet_ties.pdf (accessed 20 May 2020)

- Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., & Loewen, P. J. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? European Journal of Political Research, 60(2), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12401

- Bond, R. M., Fariss, C. J., Jones, J. J., Kramer, A. D. I., Settle, J. E., Fowler, J. H., & Fowler, J. H. (2012). A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature, 489(7415), 295–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11421

- Borgonovi, F., & Andrieu, E. (2020). Bowling together by bowling alone: Social capital and COVID-19. COVID Economics Vetted and Real-time Papers Issue. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113501

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The form of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(1), 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Czapiński, J., & Jerzyński, T. (2016). Międzynarodowy program sondaży Społecznych ISSP 2015: Raport [International social survey programme 2015: Report]. Instytut Studiów Społecznych im. Profesora Roberta B. Zajonca Uniwersytet Warszawski.

- Davenport, S., & Daellenbach, U. (2011). Belonging’ to a virtual research centre: Exploring the influence of social capital formation processes on member identification in a virtual organization. British Journal of Management, 22(1), 54–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00713.x

- Davis, J. T., Perra, N., Zhang, Q., Moreno, Y., & Vespignani, A. (2020). Phase transitions in information spreading on structured populations. Nature Physics, 16(5), 590–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-0810-3

- Di Loro, P. A., Divino, F., Farcomeni, A., Lasinio, G. J., Lovison, G., Maruotti, A., & Mingione, M. (2021). Nowcasting COVID-19 incidence indicators during the Italian first outbreak. Statistics in Medicine, 40(16), 3843–3864. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.9004

- Ding, W., Levine, R., Lin, C., & Xie, W. (2020). Social distancing and social capital: Why US counties respond differently to COVID-19, Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper: Article 27393. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3624495

- Donath, J., & Boyd, D. (2004). Public displays of connection. BT Technology Journal, 22(4), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BTTJ.0000047585.06264.cc

- Ellison, N., Heino, R., & Gibbs, J. (2006). Managing impressions online: Self-presentation processes in the online dating environment. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00020.x

- Ellison, N., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. http://doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

- Esaiasson, P., Sohlberg, J., Ghersetti, M., & Johansson, B. (2020). How the coronavirus crisis affects citizen trust in institutions and in unknown others: Evidence from ‘the Swedish experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 748–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12419

- Eysenbach, G. (2020). How to fight an infodemic: The four pillars of infodemic management. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e21820. https://doi.org/10.2196/21820

- Freimuth, V. S., Musa, D., Hilyard, K., Quinn, S. C., & Kim, K. (2014). Trust during the early stages of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Journal of Health Communication, 19(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.811323

- Frenkel, S., Alba, D. O., & Zhong, R. (2020). Surge of virus misinformation stumps Facebook and twitter. The New York Times Company. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/08/technology/coronavirus-misinformation-social-media.html (accessed 24 November 2020).

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., Barnidge, M., & Scherman, A. (2016). Social media social capital, offline social capital, and citizenship: Exploring asymmetrical social capital effects. Political Communication, 34(1), 44–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1227000

- Gooderham, P. N. (2007). Enhancing knowledge transfer in multinational corporations: A dynamic capabilities driven model. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 5(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500119

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

- Haley, R. W., Culver, D. H., White, J. W., Morgan, W. M., & Emori, T. G. (1985). The nationwide nosocomial incidence rate: A new need for vital statistics. American Journal of Epidemiology, 121(2), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113988

- Helliwell, J. F., Putnam, R. D., Huppert, F. A., Baylis, N., & Keverne, B. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 359(1449), 1435–1446. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1522

- Inkpen, A., & Tsang, E. (2005). Social capital network and knowledge transfer. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 146–165. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2005.15281445

- Jalan, J., & Sen, A. (2020). Containing a pandemic with public actions and public trust: The Kerala story. Indian Economy Review, 55(1), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41775-020-00091-5

- Jarynowski, A., Wójta-Kempa, M., & Belik, V. (2020). Trends in interest of COVID-19 on Polish internet. Epidemiological Review, 74(2), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.32394/pe.74.20

- Kavanaugh, A., Carroll, J. M., Rosson, M. B., Zin, T. T., & Reese, D. D. (2005). Community networks: Where offline communities meet online. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00266.x

- Kędzierski, M., Możdżeń, M., & Oramus, M. (2020). Analiza wpływu restrykcji na epidemię, mobilność i zużycie energii. Working paper, Kraków: Centrum Polityk Publicznych, Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Krakowie, Kraków. https://politykipubliczne.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/13-Zarzadzanie-restrykcjami-last.pdf (accessed 26 December 2021).

- Kittleson, M. (2021, December). Trust in the time of COVID-19. American Journal of Medicine, 133(12), 1370–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.07.007

- Krause, D. R., Handfield, R. B., & Tyler, B. B. (2007). The relationships between supplier development, commitment, social capital accumulation and performance improvement. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 528–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2006.05.007

- Kritzinger, S., Foucault, M., Lachat, R., Partheymüller, J., Plescia, C., & Brouard, S. (2021). Rally round the flag’: The COVID-19 crisis and trust in the national government. West European Politics, 44(5–6), 1205–1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1925017

- Larson, A. & Starr, J. A. (1993). A Network Model of Organization Formation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 12(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879301700201

- Lin, N. (1999). Building a network theory of social capital. Connections, 22(1), 22–51. https://faculty.washington.edu/matsueda/courses/590/Readings/Lin Network Theory1999.pdf

- Meredith, L. S. E., Rhodes, D. P., Ryan, H. G., Long, A., & Long, A. (2007). Trust influences response to public health messages during a bioterrorist event. Journal of Health Communication, 12(3), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730701265978

- Mikucki, J. (2021). Koncepcja smart city a COVID-19. Wykorzystanie nowych mediów w obliczu pandemii. Media Biznes Kultura, 2(11), 75–95. https://doi.org/10.4467/25442554.MBK.21.015.15156

- Muñoz-Sastre, D., Rodrigo-Martín, L., & Rodrigo-Martín, I. (2021). The role of twitter in the WHO’s fight against the infodemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211990

- Murphy, M., & Moret-Tatay, C. (2021). Personality and attitudes confronting deat h awareness during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy and Spain. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 627018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.627018

- Nadobnik, H. (2021). Media społecznościowe jako narzędzie aktywizacji osób starszych w okresie pandemii COVID-19. Analiza funkcjonowania na facebooku organizacji wybranych z czterech polskich miast. Studia Z Polityki Publicznej, 82(30), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.33119/KSzPP/2021.2.4

- Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–269. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533225

- Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105(1), 88–127. https://doi.org/10.1086/210268

- Pérez-Mengual, N., Aragonés-Barbera, I., Moret-Tatay, C., & A.r, M.-A. (2021). The relationship of fear of death between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers Psychiatry, 12, 648498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.648498

- Pitas, N., & Ehmer, C. (2020). Social capital in the response to COVID-19. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(8), 942–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120924531

- Podolny, J., & Page, K. (1998). Network forms of organization. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.57

- Portes, A. P. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern society. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Putman, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press.

- Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (1999). A dual-process model of defense against conscious and unconscious death-related thoughts: An extension of terror management theory. Psychological Review, 106(4), 835–845. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.835

- Pyszczynski, T., Lockett, M., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (2020). Terror management theory and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820959488

- Schraff, D. (2020). Political trust during the COVID-19 pandemic: Rally around the flag or lockdown effects? European Journal of Political Research, 60(4), 1007–1017. available at https://doi.org/10.1111/1475–6765.12425

- Serwis Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. (2020).Mapa zarażeń koronawirusem SARS-CoV-2 w Polsce [Coronavirus infection map SARS-CoV-2 in Poland]. https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/wykaz-zarazen-koronawirusem-sars-cov-2

- Statistics Poland. (2020). Population. Size and structure and vital statistics in Poland by territorial division in 2019: As of 31st December. https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/ludnosc/ludnosc-stan-i-struktura-ludnosci-oraz-ruch-naturalny-w-przekroju-terytorialnym-stan-w-dniu-31-12-2019,6,27.html (accessed 25 November 2020)

- Stier, A., Berman, M., & Bettencourt, L. (2020). COVID-19 attack rate increases with city size medRxiv, Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation Research Paper No19. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20041004

- Swire, B., & Ecker, U. K. H. (2018). Misinformation and its correction: Cognitive mechanisms and recommendations for mass communication. In B. G. Southwell, E. A. Thorson, & L. Sheble (Eds.), Misinformation and mass audiences (pp. 195–211). University of Texas Press.

- Taylor, M. (2000). Communities in the lead: Power, organisational capacity and social capital. Urban Studies, 37(5–6), 1019–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980050011217

- Testoni, I., Bisceglie, D., Ronconi, L., Pergher, V., Facco, E., & Duregger, C. (2018). Ambivalent trust and ontological representations of death as latent factors of religiosity. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1429349

- Uphoff, N., & Wijayaratna, C. M. (2000). Demonstrated benefits from social capital: The productivity of farmer organizations in Gal Oya, Sri Lanka. World Development, 28(11), 1875–1890. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00063-2

- van der Weerd, W., Timmermans, D. R., Beaujean, D. J., Oudhoff, J., & van Steenbergen, J. E. (2011). Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 575. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-575

- Woolcock, M. (1998). Social capital and economic development. Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society, 27(2), 151–208. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006884930135

- Wu, C. (2021). Social capital and COVID-19: A multidimensional and multilevel approach. Chinese Sociological Review, 53(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2020.1814139

- Yan, Y., Bayham, J., Fenichel, E. P., & Richter, A. (2020). Do face masks create a false sense of security? a COVID-19 dilemma. MedRxiv 2020.05.2320111302. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.23.20111302

- Yan, P., & Lau, F. (2020). Fighting COVID-19: Social capital and community mobilisation in Hong Kong. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 40(9/10), 1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-08-2020-0377