Abstract

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are the most ambitious development frameworks to assist in driving inclusive development globally. This is particularly so relative to Africa. Several efforts have been made to achieve development in Africa but more efforts are needed to achieve desired results. Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs), which used to positively impact development on the continent, have been on the decline even as African governments continue to struggle with development efforts. Current poverty alleviation efforts and development financing strategies have focused on the role of remittances in achieving development on the continent given sustained and appreciable increase in remittances and their abilities to reach/impact households. More studies are, however, needed to sufficiently understand how remittances affect, and will continue to affect, development in Africa, particularly within the framework of SDGs. Remittances are very relevant to SDGs particularly in achieving goals 1–6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 17 in Africa. It is against this background that this article examines the possibilities and potentials of remittances in driving development and achieving SDGs in Africa.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article is very important to development partners, bilateral/multilateral/multinational organisations/institutions, and broader development stakeholders to understand alternative and/or complementary ways the SDGs can be sustainably financed and driven through more strategic attention to remittances to poor countries, especially in Africa. This is necessary given the current precarious and challenging global financial situations which pose formidable threats to the achievement of SDGs in developing countries. This article contributes importantly to our knowledge by demonstrating how remittances can assist in achieving the SDGs, and development in general, if effectively and efficiently leveraged.

1. Introduction

Development should be strategic, inclusive, focused, multi-dimensional, innovative, and driven within international frameworks. This is particularly so as the continent of Africa appears to be enmeshed in a sustainable development quagmire (Akanle et al., Citation2014). Africa is known for her several developmental challenges; yet, it is dangerous to leave the continent to these development challenges especially in the age of globalization where negative occurrences in a region are bound to have impacts on other regions including the developed ones. Due to Africa’s sustained and aggravated underdevelopment and its untold consequences on the continent and the world at large, global development actors and stakeholders have recognized the need to be involved in development retooling and marshaling for the direct benefit of Africa and the world at large. In this age of globalistion, it is clear and apparent that Africa cannot be left alone to fight her development problems otherwise the whole world will suffer the consequences of the nearly intractable development problems of the continent, as can be seen in desperate and perilous migrations of Africans up North and some associated uncomplimentary consequences on destination countries.

It is against this background that Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as global development frameworks to assist Africa’s development become strategically important. Sustainable development hinges on economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability that are the three major development pillars of SDGs. In order to avoid the consequences of leaving Africa to her development dilemma, the continent is expected to adopt the most ambitious, strategic, and wide-ranging development plan framework (SDGs). SDGs give advantages and opportunities for African leaders and development actors to re-consider and re-approach development policy drafting, funding, and implementation approaches in a manner that can be tracked scientifically. Therefore, development policy drafting, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation are key and central to achieving SDGs. After the expiration of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2015, SDGs were quickly adopted by one hundred and ninety-three [193] members of the United Nations, Africa inclusive to fill the loops left by MDGs (Omobowale et al., Citation2018). The adoption of SDGs was to ascertain that no one or region is left behind on the journey to achieving sustainable development for the current generation and those to come.

The SDGs have 17 goals structured upon the lessons learnt from the performances and failures of MDGs. SDGs are used to guide development efforts globally, including the African continent until 2030, when performances, challenges, and outcomes get evaluated. Interestingly and unfortunately, the SDGs emerged at a period when the global economy and political landscapes were shaky, unlike in the era of MDGs when the global economy was comparatively buoyant and more stable. The global economic and financial context of SDGs is sluggish and challenging just as the political and policy systems of many regions and nations, including the developed ones, as they also experience a lull. Global financial systems, including the private and public sectors, are either on the decline or precarious stagnation, just as sluggish growths are prevalent in many. Financing SDGs is therefore a major issue and problem generally. This is normative as global development finance architectures face stress and uncertainty. This suggests the necessity of unusual development financing approaches even as sustainable development remains a major problem for Africa and the world in general. Early studies and experiences suggest African countries are lagging behind on the road to achieving the 2030 agenda (SDGC/A & SDSN, Citation2018). Development finance remains a strategic threat and challenge to achieving SDGs in Africa. Development growth and finance are generally slow and inadequate, and these have a significant impact on the realization of the 2030 agenda except fundings from usual and unusual quarters are explored and understood. The overall objective of this article is to objectively examine the possibilities and potentials of remittances to Africa as possible financial pathways to achieving SDGs in Africa. Through remittances, migrants are considered agents of change and strategic partners for the development of Africa (Akanle & Ola-Lawson, Citation2021). Remittances are relevant within SDGs particularly as tangents of families’ welfare, government development objectives, private sectors and market agilities, and inclusive development.

Despite several development efforts, poverty and poor infrastructures remain banes and consequences of Africa’s development. For instance, in Nigeria, the most populous black nation, poverty is at a threshold of 70% with an increasing rate of youth unemployment, corruption, dilapidated and collapse infrastructures, and insecurities that have become colossal courtesy of Boko Haram Insurgence and banditry. Development prospects continue to remain bleak in Africa, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, and many Africans have become more pessimistic about future development due to aggravated reversed development that they have witnessed after several successive governments. For example, as Africa’s case study, Nigeria is a major country in Africa, resourcefully endowed, and has a large economy (Akanle et al., Citation2014;), yet it is among the poorest and underdeveloped countries in the world. Nigeria is fifth (5th) position among the poorest countries in the world due to its widespread poverty, persistent underdevelopment, epileptic power supply, bad infrastructure, corruption, bad governance, and violent conflicts that have become cankerworms eating deeper into the fabric of the nation.

Generally, the proportion of Africans living in absolute poverty has substantially increased with about 135 million people within the space of 25 years (1990–2015). This has caused African leaders to frantically look for better solutions to the development challenges plaguing the continent, thereby moving from one development reform to another (World Bank, Citation2019). The precarious financial and economic realities across the world that make the development and achievement of SDGs problematic necessitated the need to examine and appreciate the unusual financial architectures like remittances. Recent studies have signaled remittances yet to be exploited as sources for sustainable development (Akanle & Adesina, Citation2017; Lumpur, Citation2018). For instance, according to Akanle and Adesina (Citation2017), the number of migrants has risen considerably to about 200 million, and they continuously send remittances to improve left-behind households’ welfare. Migrants can become important stakeholders in development financing. It is therefore pertinent to factor into the analysis and implementation of SDGs; achievement, management, implementation, and evaluation especially in Africa going forward (Akanle & Adesina, Citation2017).

Scholars (Hickel, ; Oloruntoba, Citation2020; Spaiser et al., Citation2016; Struckmann, Citation2018; Swain et al., Citation2017; The Economist, Citation2015) globally and locally have heavily criticized SDGs as an ambitious and prioritized focused development framework using indices like its inconsistency, difficulty to measure, implement, and monitor. Despite these critiques, some scholars assert that Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are germane to the universal discourse of development, hence their importance as a development framework. Being mindful of the global debates around SDGs, this article examines the possible effects of remittances on African development leveraging on the SDGs framework. The article explores the relevance of remittance as a driver of sustainable development if properly harnessed and calls for development architecture retooling by positioning migrants as strategic stakeholders’ on the discourse of Africa’s development and achievement of SDGs. Structurally, this article is divided into eight sections including the Introduction. The next section is the Methodology followed by: Africa and International Migration, Theoretical Issues in SDGs, Remittances and Development of Africa, Remittances, Development Financing and Development in Africa, SDGs and The Development Challenges/Situations of Africa, Remittances in Africa and Conclusion, respectively.

2. Methodology

The study that informed this article adopted a scientific/objective methodology. The research design adopted in this article was exploratory and unobtrusive. The exploratory unobtrusive research design was adopted for objectivity reasons and to cover the research interests comprehensively enough across contexts and issues. The research design was considered suitable in the instance and contexts of the study that informed this article. Data collection was done through secondary data and autoethnography leveraging also authors' over a decade of research engagements and lived experiences. Secondary data were gathered through journal articles, books, unclassified official documents, databases of development partners/organisations and reliable online sources. Primary data was based on autoethnography. Data analysis was done through content and thematic analyses. Ethically, the research posed no threat to humans and respected ethical principles of anonymity, beneficence and nonmaleficence throughout the research process.

3. Africa and international migration

Remittances are consequences and flipsides of migration. This section explores the interface between remittances and migration for clear, lucid, and pragmatic analysis. The African continent is the second-largest continent in the world with about 54 sovereign countries and Africans among the most migratory in the world. Africa is also among the highest recipient continents of remittances globally. The migrant population was projected to double in the near future (De Haas, Citation2006; Mberu & Pongou, Citation2010). Although many Africans move within the continent, a lot migrate to America, Europe, Australia, and Asia. Migrants from Africa move as modern slaves, seamen, students, intellectuals, traders, asylum-seekers, and economic migrants and produce communities in destination locations (Akanle & Adesina, Citation2017; Castillo, Citation2014a; Haugen, Citation2012; Korieh, Citation2006; Koser, Citation2007; Massey & Taylor, Citation2004; Mberu & Pongou, Citation2010). Generally, every country is affected by migration either as a sending or as receiving country and remittances remain moderating forces in the international migration space.

Migration in either large or small numbers across different borders has the capacity to enhance life-chances both to the origin and destination countries especially relative to remittances; hence, the discussion to ease migration corridors and encourage safe migration (Koser, Citation2007). Migration will not reduce in the near future especially due to the ascendancy of globalization that will continue to facilitate increased human mobility as it becomes more embedded in worldwide economic and social structures, and make it easier for more people to move at a reduced cost and increased speed with increased opportunity for huge remittances flow. Migration becomes a key factor in achieving sustainable development as migrants are now being recognized as agents of positive change in poor countries, including in Africa. Migrants are becoming increasingly popular in development finance due to impacts on household welfare, poverty reduction, and national foreign exchange earnings (Adepoju, Citation2010; Akanle, Citation2018; National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016; Naudé, Citation2012; Okafor & Obor, Citation2014; Omobowale et al., Citation2018; Rodney, Citation1972).

Africa’s deepening into underdevelopment continues to drive Africans, especially the agile and ambitious youths, up North in search of greener pasture (Orozco, Citation2002). Van Dalen et al. (Citation2005), while studying intentions to emigrate from Africa among Ghanaians, Senegalese, Moroccans, and Egyptians, found that emigration pressure is high in West Africa, especially among males due to what they called modern values. Van Dalen et al. (Citation2005) observed that optimism about economic prosperity upon migration is a determining factor for migration up north. Migrants receive financial, moral, and spiritual support from family members who believe that kin’s migration ultimately leads to economic success because of migration (Pelican & Tatah, Citation2009). Historically, Africans have experienced a variety of migrations in response to poverty, economic instability, political instability, high rising population, and endemic conflicts leading to insecurity and environmental challenges (Adepoju, Citation2003, Citation2005). These factors remain major forces influencing migration processes on the African continent. More recently, in corroboration to Adepoju’s submission on factors influencing African’s migration, Chereni (Citation2014) notes that real and perceived opportunities influence the popularity of Gauteng, South Africa, as a migration destination. Agadjanian (Citation2008) and Adeniran, (Citation2014) also emphasized the role of regional policies on free movement in driving population mobility in and from Africa.

Considering that poverty is a key push factor in African migration, it is also a major player in the response of migrants’ remittances to their home of origin. The kin relationship existing among Africans makes it normatively mandatory for migrants to always give support in terms of remittances to their left-behind kinfolks. This has made remittances popular lifelines in Africa as most of the poverty alleviation schemes have failed (World Bank, Citation2013). Nigeria, being the highest migrant sending nation in Africa, receives the highest percentage of remittances sent to sub-Saharan Africa. Globally, 34 million migrants are from Africa out of the 244 million international migrants. Migration and economic growth are intertwined as migrants’ remittance has the capacity to play significant roles in driving development if adequately understood and utilized origin countries, including in Africa.

Migrants’ remittances drive development in Africa as observable in its contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For instance, Cote d’Ivoire recorded 19% in 2008, Rwanda had 13% and South Africa was also able to record remittances input of 9% just as Ghana’s migrant remittances contributed 1% (World Bank, Citation2013). This portrayed international migration as a major sustainable development scheme in Africa if appropriate financing policies are implemented. From 2014 to 2016, Africa had a tremendous increase in remittance flow of about $64 million compared to $38 million in 2007 (World Bank, Citation2019, Citation2020; World Bank Group, Migration and Development Brief 27, Citation2017). Although there have been predictions of a sharp decline in remittances from international migrants going forward due to the shock of the coronavirus pandemic, particularly in international economies that will affect migrants’ jobs at destinations countries, remittances have shown appreciable resilience that may prove such predictions and projections wrong(World Bank, Citation2020). Considering that economic migration remains a key feature of international migration, global and African leaders may have to retool, re-strategize, and reprogram to channel development plans along with remittances from migrants.

4. Theoretical issues in SDGs, Remittances, and Development of Africa

Sustainable development is interested in development that meets the needs of today and that of the future generations without damaging the social, economic, cultural and physical environments (Clark, Citation1989; Lee, Citation1993b; Vierderman, Citation1994). Sustainable development is a development that is fair and inclusive in the short and long run. The idea of sustainability when discussing development was portrayed by the world environmental and development commission, Brundtland as a development or growth that caters for the wants of the people presently without alteration to the future generation needs. SDGs were adopted at the end of Millennium Development Goals in 2015 and it serves as a tool that can be used in completing the unfinished work of MDGs, hence the adoption of the ambitious 2030 agenda “transforming our world”, by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015.

Sustainable development is a holistic concept with 17 goals set out to address three major growth dimensions: economic growth, social inclusiveness, and environmental sustainability. These goals include poverty alleviation; zero hunger; ensuring a healthy life and improving the state of well-being; quality education; equality between gender and women empowerment, achieve potable water and sanitation, improve modern energy; provision of productive employment, and decent work. It also aims to ensure resilient and sustainable cities; promote sustainable consumption and production pattern; combating climate change and its impacts; ensure sustainable use of water bodies; sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystem; promote peaceful and inclusive societies; and promote global partnership.

ne paramount concern of both developing and developed countries is development, either by working towards growth or by sustaining the growth. Development is required in every institution of society, ranging from the economy of a country, education, health, increasing employment opportunities, sustaining the environment, provision of social amenities, migration, and remittances. Much concern has, however, been placed on how to enforce direct strategies on these sectors to bring about development without paying close attention to the indirect strategies that can be undertaken to ensure development within developing countries, Africa as a case study. One of these indirect strategies is remittances to African countries. Remittances can only occur after the migration has taken place. Without the movement of people out of their home country, towns, there will be little or no need to send money to their home countries. More often than not, emigration or out-migration is as detrimental to the origin countries as it has a way of determining if development can occur or not, especially when the able-bodied men tend to be the ones migrating (Akanle, Citation2018). Through remittances, migrants become agents of change and strategic partners for development in Africa. To actualize most of these goals, remittances must receive the needed attention based on its relevance in achieving the goals on or before 2030.

5. Remittances, development financing and development in Africa

Studies have investigated the importance of remittance flow into countries and it has become evident that the flow of remittances positively and negatively influences economic growth. Moreover, remittance recipients are to move above the poverty line because these households now have a higher means of income. Another research carried out showed that transfer of funds increases the availability of workforce that increases productivity, and the competitive level of the receiving country. However, one cannot overlook the fact that it increases the effectiveness of the bank system, which then helps in the development of domestic companies, it enhances accessibility to the financial section, raises inflation, changes the exchange rate (Bayangos & Jansen, Citation2011; Cooray, Citation2012; Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Inoue & Hamori, Citation2016; Prakash & Mala, Citation2015; Rausser et al., Citation2018; Tung, Citation2018; Tung et al., Citation2015).

A study of 36 countries showed that the inflow of funds through migrants impacts and improves financial development by being a substitute for finance businesses. Remittances also contribute to the economic growth of a country (Fayissa & Nsiah, Citation2010). The reasons above showed the manifest function of remittances to receiving countries. In 2010, Shakur studied the “how remittances have an impact on investment” and a study found out that “remittances impact investment directly and indirectly through a better institutional framework and more developed financial sector”.

One of the basic instruments that should come to mind in the discourse on improving development is migration; migration is a mechanism that has shown to be useful to attain and sustain developmental goals and the impact of migration can be directly or indirectly. The indirect impact of migration is seen through remittances to the origin country; hence, governments and other sectors should place much focus on the trajectory between Migration, Remittances, and how these variables help in actualizing the SDGs. Movement of people and remittance will continue to play a significant role in developing the economic, social, and political sector of any developing country. Moreover, one cannot neglect that most of the migrants are from a less developed country, and their remittances account for about US$592 billion in 2014. To ensure financial development in Africa through remittances, some basic strategies must be adhered to by different financial institutions. One of the strategies is to ensure or encourage remittance recipients to open accounts in financial institutions and use financial products. It also provides financial education and accurate information to recipient families about their financial options.

It is also necessary to train staff at financial institutions on how to link transferring funds, banking, change the remittance recipients to customers. It is also necessary to provide technical assistance for business development and reduce barriers to deposit and invest. In developing the finances of a country, remittances must contribute to the formation of monetary benefit; improve entrepreneurial activities and provide an opportunity for investment (Ellyne, Citation2017; Orozco, Bump, Fadewa et al., Citation2005). The ability to invest remittances into the various spheres of the institution will bring about advancement in the country, especially Africa. For instance, in Pakistan remittance increases the population’s ability to invest in agricultural activities in terms of having the resources to purchase crops, lands, and where necessary equipment needed for mechanized farming (Adams, Citation1998). Similarly, the Africa Migration Project displayed an equivalent result. They found that remittances to Africa were reinvested in farming, agricultural equipment, property, and small-scale businesses. Statistically, in Nigeria, about 57% of remittances are invested, 55.3% in Kenya, 20.2% in Uganda, 36.4% in Burkina Faso, and 15.5% in Senegal (Ellyne, Citation2017; Ratha et al., Citation2011).

More recently, remittances if joined with other financial means will have a great impact on low-income households and Africa in general. Moreover, the projection has it that 80% of remitted funds are for instant consumption. Apart from these remittances being used to sustain life, it is also used for long-term purposes like acquiring landed property, housing, business, school enrolment (Education), and so on (Nurse, Citation2018). Migrants’ remittance has become a useful tool in poverty alleviation, which, however, aligns with SDG 1 “No poverty”. Literature shows that funds remitted to households allow receiving households to live quite above the poverty line and have a sustainable means of income (Kamuleta, Citation2014). In 1991, Adams carried out a study in Egypt where he used 1000 households as his sample size. He, however, found out that poor households decrease by 9.8% with the inflow of international remittances, hence the convergence of remittances at all levels. Remittances positively affect the socio-economic status of receiving households and help in actualizing SDGs 1–5. For instance, in Egypt during the Arab spring when the political instability struck the country, the flow of remittance proved to be the major source of income for receiving households. There was a speedy increase in remittances between 2009 and 2011. Moreover, a study that was carried out in 71 developing countries showed that there is a significant relationship between remittances and poverty reduction. The result of the study showed that a 10% increase in international remittances will lead to a 3.5% decrease in people under the poverty line (Kamuleta, Citation2014).

The money or items received by migrants’ households represent 60% income and are mostly used for unforeseen circumstances (IFAD, Citation2017) which have also help to actualize zero hunger (SDG-2). An increase in income is an increase in food production, improved nutrition, and the ability to afford enough food that is sufficient for the household. On the other hand, investment of remittances in agricultural activities is the creation of employment opportunities in the receiving country. Furthermore, achieving SDG 2 through an increase in income (SDG 1) will improve the healthy lifestyle of the households by having access to nutritional foods, health care systems, preventive care and health insurance products, and access to medicine. In addition, the mortality rate reduces in households who receive remittances because the children and elders receive adequate health care, thereby actualizing SDGs 3. For instance, Amega (Citation2018) as cited in Amakom and Iheoma (Citation2014b) noted that remittances increase life expectancy at birth by 1.2%, though Jamaica showed otherwise. Remittance receiving households are at the advantage of accessing better education that leads to an increase in school enrolment and attendance, especially for girls. Moreover, it reduces the probability of child labour and early girl-child marriage (IFAD, Citation2017). Studies have shown that remittances have a way of influencing and achieving sustainable development goals. With remittances being used for education, food, job creation, health maintenance, personal development is inevitable and when there is continuity of resources being remitted, development can be sustained (Amega, Citation2018; IFAD, Citation2017; Nurse, Citation2018).

This, however, leads to reaching SDG 4 and 5, quality education, and ensuring equality for all genders. At the community level, remittances have proven to be of significant importance to developing communities and countries by encouraging market competition and regulatory reform. In 2012, a cross-country study conducted in 69 underdeveloped and developing countries found that funds remitted had a higher impact on educational outcomes, especially at the high school level. Statistically, a 1% rise in real remittances per capital leads to a 0.12% increase in registered students in high school and a .09 percent increase in primary education rate (Amega, Citation2018; Zhunio et al., Citation2012). In Ghana, for instance, estimation projected that the number of primary school enrolment rose by 13% for households that are international remittance recipients and 54% increase in secondary school enrolment for remittance-receiving households (Amega, Citation2018). Salas (Citation2014), Hines (Citation2014) showed that remittances have affected the number of school dropouts positively due to the investment in human capital found among migrants (Raza et al., Citation2019). In Africa generally, Nigeria and Uganda spend most of their remittance on education and this makes education the second-highest expenditure that remittance is often spent on, while the third-highest is Burkina Faso and the fourth is Kenya (Ratha et al., Citation2011). As of 2011, Nigeria spent 20% of its remittances on education, Uganda spent 15% on education. Remittances are linked with investing in education, improving entrepreneurial activities and health system of recipients, and in the long run affect the economies of a nation.

Funds remitted have proven to be a consistent channel of finance at the micro level to developing countries like Africa. Amuedo-Dorantes and Pozo (Citation2014) stated that remittance “represents a steady and outsized supply of foreign currency, and it helps drive current account changes during period of economic stability, facilitates the inflow of new investments, and improves a country’s credit rating” (Ellyne, Citation2017). It improves the financial resources available to the general economy, when a substantial number of these remittances are invested into entrepreneurial activities, in micro, small and medium enterprises, job opportunities will be effectively generated thereby reaching SDG 8. These goals are geared towards sustainable economic growth, provision of employment, and decent work for all. By the end of 2030, expectations are that countries under the United Nations would achieve equality within and among countries. One way countries hope to actualize this goal and ensure sustainability is through remittances. Reduction in the cost of transferring remittances can ensure equality among countries. For instance, if the cost of transferring remittances can be reduced to 3% globally, remittance-receiving households will be able to save about U$20 billion annually (IFAD, Citation2017) thereby achieving SDG 20. If every country becomes aware of the effectiveness of remittances to their economy, host countries will therefore see the need to provide better work for migrant workers. Besides, strategies such as global compact for safe initiative, systematic and regular movement of people, and the international community should recognize remittances as an important support for millions of people across the world and work to strengthen their development impact on families and communities thereby actualizing SDG 17 (IFAD, Citation2017).

Ultimately, the goals laid down by the United Nations are to ensure development of all ramifications and for these goals to be actualized, remittances can be used as a tool in achieving these goals. Human development should be one of the focuses of every government both at the local level, state level and at the federal level (IFAD, Citation2017). Human development ensures the well-being of the people of a country. Securing the well-being of a country’s populace is placing a lot of attention on achieving SDG 1–5, and remittances have however proven to be a great tool for actualizing human development (Amega, Citation2018; IFAD, Citation2017; Raza et al., Citation2019). Development of human capital is a step ahead in the development of a nation as these people make up the labour market and those who are expected in the labour market. Also, most remittances are targeted as developing capital and economic projects by starting up businesses in their home countries, and in the process of establishing these businesses, dues and licenses are paid to the government, and the GDP of the country gets improved (Ellyne, Citation2017). Remittances raise the domestic savings, which in turn improves the growth of the receiving countries. This is evident in the Middle East and North Africa, where there is a relationship between the development of financial systems and remittances (Kamuleta, Citation2014)

Through the means stated above, SDG 8 is achievable. Basically, to achieve decent work and employment opportunities in home countries, funds remitted by people in the host country can help establish entrepreneurial activities, invest in agricultural activities in their home countries, thereby leading to the betterment of the country (IFAD, Citation2017). In addition, taxes and dues that are received from the establishment of these businesses and alliances can be invested into other sectors of the country such as the health system, improve the educational facility and provide clean water and improve sanitation, church and the development of the community in general. For instance, in Senegal and Ghana, migrants have been able to improve their society. In the 1980s and 1990s, the health institution was sustained due to the donations received from migrants who send in remittances. It has been recorded in Ghana that the remittances received are used in establishing small-scale businesses, which in turn generates income from which people tend to pay taxes from as well as create employment opportunities for the youth (Kamuleta, Citation2014). Insofar as the dues and fees for these sectors are properly used, becoming a developed country or continent can be achieved as fast and easy as possible. One of these sectors that these taxes and dues can be ventured into is the water and sanitation aspect of African countries.

Clean water and sanitation have been one of the greatest challenges of African countries since the government has done little or nothing about the detrimental situation ravaging different communities (IFAD, Citation2017). Nevertheless, families who receive remittances have been able to build boreholes in their houses thereby extending it to their communities by placing taps outside their homes for those around them to have access to clean water, which in turn develops the communities. One can see that remittances have a way of developing communities especially when the funds received are invested into improving the state of the community as a whole, thereby actualizing various goals placed by the United Nations. On the other hand, the global partnership has been the concern of many countries especially when it comes to attaining the development of first world countries. The global partnership can, however, be achieved through networking, which can aid and expand operational scope and structure.

When migrants in the Diaspora liaise with foreign organizations in their host countries and incorporate such foreign organizations and ideas in their home countries, the development will be inevitable because remittances are not just about funds but ideas and human resources (IFAD, Citation2017; Nurse, Citation2018). Moreover, the government gets a substantial amount of money from such a global partnership. It should, however, be noted that the sustainability of development is paramount to every country as continuity enables different generation’s needs to be met. Therefore, the focus should not be placed on how remittances can help develop communities and actualize the sustainable development goals, rather, attention should be placed on ensuring that remittances are continually remitted into migrant’s home countries and much of the resources received are invested into personal development, communal development and national development (Fayissa & Nsiah, Citation2010; United Nations, Citation2015).

Remittances have proven to influence the wealth creation of the receiving nation, one cannot overlook the negative effect of remittances. Through an increase in family earnings, lessening of fund constraints, remittances can decrease the supply of manual labour or the input of recipients in labour market, which will in turn decrease the output growth of the economy. Some even argued that when remittances increase the price of locally manufactured commodities and an increase in real exchange rate occurs, such an outcome can reduce the competitiveness of the country and boost the current account deficit (Kireyev, Citation2006; Singh et al., Citation2010). Migration and remittances will continue to add to and increase the growth of the economic sector, the political sector, and the social sector of a developing country (Topxhiu & Xhelili, Citation2016).

6. SDGs and the development challenges/situations of Africa

Dating back to the 1960s, the African continent has experimented with a variety of development strategies (Magbadelo, Citation2003) because development remains a major challenge that needs urgent attention since many nations of the continent became independent. Most of the African nations still lag in every aspect of development, as evident in several of their failed development reforms. Africa still faces an array of development challenges ranging from economic insecurity, insurgence, political instability, corruption, and a host of others. Discourses on economic development and sustainable development in developing settings like Africa remain germane within the global sphere, hence the necessity to adopt the most ambitious public plan framework. Although the underdevelopment of Africa is often linked to her contacts with western countries (Rodney, Citation1972), the global framework of development must be diligently adhered to for sustainable development in Africa else it will result in a disastrous situation, which will not only affect Africa but the world at large.

Major challenges confronting Africa in the twenty-first-century include rapid urbanization, economic insecurity, poverty, political fragmentation, violent conflicts, gender inequality, ethnicity, illiteracy, and poor infrastructure. This section examines Africa’s development challenges in the context of sustainable development goals. A good starting point of Africa’s development dynamics is to have a proper understanding of its trajectories. Dating back to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) era, development was said to have experienced a rapid turnaround in human history. The major success of the MDGs was a significant decline in the poverty rate among the global population (World Bank/World Bank/IMF, Citation2016) by half and also its effect on the deficit of income beneath the poverty line from about 13% in 1990 to about 3% in 2012. Despite this decline, however, poverty remains a cancerous development challenge in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with nine hundred million extremely poor and seven hundred projected for 2015. Decades ago, about 95% of the world’s poor is recorded in three regions: South Asia, East Asia and Pacific, and sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Bank and IMF, poverty has tirelessly wax stronger with about 42.6% in sub-Saharan Africa amid rapid population (Akanle, Citation2018; World Bank/IMF, Citation2016).

Nevertheless, the inability of the MDGs to drive home sustainable development effectively and economic growth in every area of Africa and globally led to the evolution and adoption of Sustainable Development Goals as an ambitious agenda that encapsulates the needs of every continent. Considering the overlapping connection of the world at large, SDGs became a more holistic and pragmatic vision for achieving sustainable development globally. A major priority of the SDGs is to accomplish the unresolved issues of the MDGs. It recognizes the interconnectedness of the world at large and emphasizes the necessity of collective action towards the realization of the setout goals for all, hence its slogan, “to leave no one behind”. SDGs understand the interaction between development goals that cannot be effectively pursued in isolation from others, hence the explicit articulation of the goals based on integration, an indivisible and balanced dimension that hinges on economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental sustainability (Dobbs et al., Citation2015; Singh, Citation2012).

It is pertinent to appreciate the inter-linkages of Africa’s development and sustainable development. According to Todaro and Smith, development is a process that involves the improvement of every aspect of human lives (Todaro & Smith, Citation2003). As noted earlier, a major concern of development for Africans is poverty eradication. The continuous increase in absolute and relative poverty remains a tumor that development stakeholders are worried about and need to resolve before it kills everyone in Africa and to ignite the hope of the citizens about sustainable development. The leaders must brace up and maximize every opportunity, including remittances, to ensure the success of a sustainable development agenda, unlike having a repeat of the below-average record of the MDGs. Development stakeholders must tackle bad governance, insecurity, poor historical consciousness, poverty, illiteracy, mortality, economic stagnation as these remain the bane of development on the continent (Bairoch, Citation1993; Grier, Citation1999; Omobowale, Citation2015; Rodney, Citation1972).

7. Remittances in Africa

Works on remittances have partly focused on developing regions and opined that remittances are a critical financial flow even though it could replace other forms of financial flows into the country. “The transfer of money or other kinds of materials to left behind kinfolks by a migrant is known as remittance (IMF, Citation2013, Citation2009). Rather than remittances being tangible, they can as well be intangible values acquired by migrants in their host country. The remittances in the form of social nature will, however, be transferred to their home country. These remittances are not just important to the family of migrants, but they also serve as a major stream of external development finance and are more stable than any other form of external financial sources, such as Portfolio Equity (PE), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Overseas Development Assistance (ODA; Buch & Kuckulenz, Citation2004; Ratha, Citation2003). European Parliament Policy Department (Citation2014) carried out a study on remittance and their findings showed that remittances are more suitable sources of foreign currency for developing countries than any other financial inflows, such as public debt and direct investment. Studies have shown that the main determinant of remittance inflows into countries is altruism and self-interest (Lucas & Stark, Citation1985). Migrants remit funds to their households who are in their home countries because of the altruistic feelings they have. In addition, self-interest has been another determinant of remittance flow, which is seen as remittances that are sent to invest in their reputation after leaving the Diaspora.

Globally, in 2018, the inflow of remittance reached about US$613 billion (World Bank, Citation2018). The trend in remittances to African countries can be traced to when migration began, be it international migration or internal migration. The increase in remittances to Africa was about 4.9 billion USD in 1990 and rose to 11.45 billion USD in 2000. The estimate has it that, by 2007, remittances to Africa would hit 50 billion USD, and by 2010; it has increased to about 460 billion USD (World Bank, Citation2018). The importance of remittances to Africa cannot be overemphasized, as they account for over 15% of GDP in Liberia, Comoros, Gambia, and Lesotho. It is also seen as a means of foreign financing and external financial inflow to Africa (Ellyne, Citation2017). For instance, the inflow of remittance in Nigeria is the highest compared to every other African country. In 2017, Nigeria ranked the sixth position in the world, and in 2018 about 24.2 billion USD were remitted to Nigeria. However, the increase in remittance to Nigeria prides in the improved global economic condition (CBN, Citation2017).

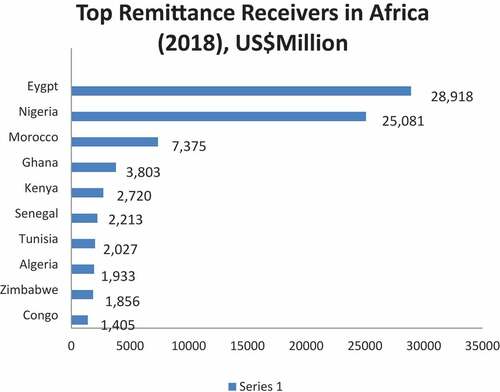

Source: KNOMAD (Citation2018)

The table above shows a graphical illustration of the flow of remittances to some African countries. The bar chart showed that Egypt and Nigeria receive the most when it comes to remitting funds, while Zimbabwe and Congo are the lowest recipients of remittances in Africa.

Statistics from World Bank Group, Migration and Development Brief 27 (Citation2017) showed that remittances to Nigeria covered one-third of the formal remittance in-flow into the African continent. For instance, it is ten times higher than that of Senegal. The opening of the Nigerian Capital Market (IMF, Citation2016 increases remittance flow in the country by around 2005, though cash and materials remitted through the illegal channel are not often recorded in the official database. Akanle (Citation2018)() assumed that most of the informal remittances account for 50% of the total flow of remittances to Nigeria. Lately, the global remittances are expected to decrease by 20% in 2020 due to the recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic. If the projection is right, a sharp decline awaits to occur in the inflow of remittances to developing countries and Africa especially. The reason for the decline in these remittances could link to the reduction in the earnings of migrant workers, who seem to be weaker during the period of economic crisis. Moreover, remittance to developing countries and Africa, in general, could fall by 19.7% to US$445 billion, which will affect the finances of many vulnerable households, especially households in developing countries (World Bank, Citation2020).

The Coronavirus Pandemic has caused an economic recession, which then took a harsh toll on the migrants’ capability to remit to their domicile countries. Statistics on remittances to different countries in Africa have shown a great fall in the inflow of finances into the country. For instance, in North Africa and the Middle East region, the World Bank (Citation2020) projected that there will be a fall by 19.6% to US$47 billion. The reason for this fall is due to the global slowdown and the impact of lower oil prices, though the transfer of funds to these regions, with high hopes, is expected to increase at a small pace in 2021. While in sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank (Citation2020) accounted for a decrease of 0.5% to US$48 billion in 2019, due to the pandemic (Coronavirus) ravaging the country, it is expected that there should be a decline of remittances by 23.1% to US$37 billion in 2020. Nevertheless, a projected increase of 4% would be in recovery come 2021. The coronavirus outbreak is a major factor causing the decline in these remittances; this is because the virus has affected the migrants in different host countries like the United States and China.

The cost of sending remittances determines whether migrants use the regulated or unregulated modes of transfer (World Bank, Citation2020). Regulated channels are usually the most expensive channels, and they are as well complicated. Regulated channels for sending remittances are banks and non-bank institutions, MFIs, TOs, credit unions, cooperatives, and post offices (World Bank, Citation2020). Western Union and Money Gram are the two main regulated MTOs within Africa. However, compared to regulated channels, most migrants remit funds through the unregulated modes because of the low or no charges allocated to sending money home (Akanle & Adesina, Citation2017). The unregulated channels are faster and more convenient and are not affected by currency exchange rate regulations and remitters are required not to have bank accounts. Many migrants use unregulated channels. This is especially so among the undocumented migrants.

This is why it is often maintained that figures on estimates of remittances, especially to Africa, are gross underestimation as unregulated channels are huge yet usually poorly accounted for and/or unaccounted for (Akanle & Adesina, Citation2017; Akanle & Olutayo). The rate of sending funds to African countries is quite on the high side compared to other remittance-receiving countries due to little or no competition with and among the service providers who help in the transferring of funds. In developing countries, the charges collected in sending funds or remittances are high in comparison to other countries or regions. Statistically, the average rate of transferring funds to Sierra Leone is 7.48% to 26.01% in Malawi, while countries like Botswana and Mozambique cost of sending remittances was on an average of 18.06% and 2.34%, respectively (UN, 2013). Moreover, Africa has 10 of the most expensive remittance corridors in the world ranging from 19.3% to 26.6% average costs.

8. Conclusion

Development remains a concern wrapped around the neck of every political leader like an umbilical cord, globally and locally. Several efforts have gone down in history to achieve sustainable development at every level around the world, Africa inclusive. Most of the schemes of development on the continent have met little or no achievement; likewise, the global frameworks have decreased drastically, hence forcing many world leaders to seek alternatives to better economic growth. SDGs have emerged as a global framework as an appropriate medium of ensuring standard lifestyle for all humans, hence its slogan “leave no one behind”. In this article, we note migration and remittances as insufficiently tapped but curial sources of attaining the goals laid down and developed generally by the United Nations. In general, this article shows that migrants’ remittances are key factors that must be taken more seriously in development efforts and growth frameworks in Africa, especially when looking at achieving the SDGs on or before 2030. Remittances have the capabilities to go a long way in achieving development that is sustainable by reducing hunger, poverty, improving health, water, and sanitation, and ensuring equality and education for all at the individual and community level.

At the national level, remittances received by developing countries can be a supporting tool for economic growth, a form of financial investment into the country, as well as investment in human capital. Moreover, the banking sectors are at the advantage especially when there are channels through which remittance flow in and the continuous inflow of remittances will simultaneously bring about a continuous development, which ultimately leads to achieving sustainable development. The article also tried to point out the issues that have and have been encountered by African countries in ensuring development through remittances. It is, however, evident that government policies, rules, and regulations have a way of affecting development. Also, sending of remittances through unauthorized channels because of high charges fees is a huge factor of underdevelopment. More often than not, the government often discourages migration, out-migration, and emigration; those left at the origin owing to inadequate information about the significance of transferring funds to home countries. The concern is often high when the agile population frequently migrates.

Migration is of great significance as inflow of remittances cannot occur without migration. Thus, rather than discouraging international migration, governments and partners should implement policies that will ensure positive, sustainable and mutually beneficial migrations and flow of remittances across time, contexts and boundaries (Akanle, Citation2018). Hence, stakeholders need to pay much more attention to lowering remittances’ transfer fee as this will encourage migrants to make use of authorized channels. Financial institutions should also place much focus on travellers’ families by instituting inclusive savings and product plans. The trajectories between remittances, job creation, and global partnership can act as a strong tool towards achieving development (Akanle & Ola-Lawson, Citation2021) particularly in context of SDGs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Olayinka Akanle

Ọláyínká Àkànle (PhD) is a lecturer in the Department of Sociology, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. He is also a research associate in the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. His research interests include: Sociology, Development studies, International migration, Diaspora studies, Conflict and Humanitarian studies, Data management, Gender studies Child, Youth and Family studies, as well as Social policy.

Irenitemi G. Abolade holds a degree in sociology from the Department of Sociology, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Ibadan. Her research interests include the sociology of development, gender studies, critical management studies, social theory, international migration and diaspora studies, and urban sociology.

Demilade Ifeoluwa Kayode has degrees in Sociology from Bowen University, Nigeria and the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Her research interests include but are not limited to urbanization and migration, social policy, sustainable development, environmental sustainability, qualitative and quantitative methods, and entrepreneurship. She has a passion for teaching and academic writing.

References

- Adams, Jr., R. H. (1998). Remittances, investment, and rural asset accumulation in Pakistan. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(1), 155–16. https://doi.org/10.1086/452390

- Adeniran, A. I. (2014). Migration and regional integration in West Africa: A borderless ECOWAS. Springer.

- Adepoju, A. (2003). Migration in West Africa. Development, 46(3), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/10116370030463006

- Adepoju, A. (2005). Migration in West Africa; A article prepared for the policy analysis and research programme of the global commission on international migration. Human Resources Development Centre Lagos.

- Adepoju, A. (2010). Introduction: Rethinking the dynamics of migration within, to Africa. In A. Adepoju (Ed.), International migration: Within, to and from Africa in world (pp. 9–46). Sub-Saharan Publishers.

- Agadjanian, V. (2008). Research on international migration within Sub-Saharan Africa: Foci, approaches, and challenges. The Sociological Quarterly, 49(3), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.00121.x

- Akanle, O. (2018). International migration narratives: Systemic global politics, irregular and return migrations. International Sociology, 33(2), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580918757105

- Akanle, O., Adebayo, K., & Olorunlana, A. (2014). Fuel subsidy in Nigeria: Contexts of governance and social protest. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 34(1/2), 88–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-01-2013-0002

- Akanle, O., & Adesina, J. O. (2017). International migrants’ remittances and kinship networks in Nigeria: The flip-side consequences. Journal of Anthropological Research, 73(1), 66–91. (Spring 2017). https://doi.org/10.1086/690609

- Akanle, O., & Ola-Lawson, D. O. (2021). Diaspora networks and investment in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 002190962110529. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096211052970

- Amakom, U., & Iheoma, C. G. (2014b). Impact of migrant remittances on health and education outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, 19(8), 33-33. https://doi.org/10.9790/0837

- Amega, K. (2018). Remittances, education and health in Sub-Saharan Africa, cogent economics & finance. Cogent Economics and Finance, 6(1), 1516488. https://doi.org/10.80/23322039.2018.1516488

- Amega, K., & Tajani, F. (2018). Remittances, education and health in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1516488. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1516488

- Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Pozo, S. (2014). Workers’ remittances and the real exchange rate: A paradox of gifts. World Development, 32(8), 1407–1417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.02.004

- Bairoch, P. (1993). Economics and world history: Myths and paradoxes. University ofChicago Press.

- Bayangos, V., & Jansen, K. (2011). Remittancesandcompetitiveness. The case of the Philippines.WorldDevelopment, 39(10), 1834–1846.

- Buch, C. M., & Kuckulenz, A. (2004). Worker remittances and capital flows to developing countries, ZEW-centre for European economic research discussion article, No, 04-31. IDEAS/REPEC. Retrieved June 1, 2020, ZEW-centre for European economic research discussion article, No, 04-31 www.http://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/dp/dp0431

- Castillo, R. (2014a). Feeling at home in the “Chocolate City”: An exploration of place-making practices and structures of belonging amongst Africans in Guangzhou. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 15(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2014.911513

- CBN. (2017). Annual report, s. 1: Central Bank of Nigeria.

- Chereni, A. (2014). A methodological approach and conceptual tools for studying migrant belongings in African cities: A case of Zimbabweans in Johannesburg. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 39(4), 293–328.

- Clark, W. C. (1989). Managing planet earth. Scientific American, 261(3), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0989-46

- Cooray, A. (2012). Migrant remittances,financial sector development and the government ownership of banks: Evidence from a group of non-OECD economies. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 22(4), 936–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2012.05.006

- De Haas, H. (2006). International migration and national development: Viewpoints and policy initiatives in countries of origin–The case of Nigeria. International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford.

- Dobbs, R., Manyika, J., & Woetzel, J. (2015). No ordinary disruption: The four global forces breaking all the trends. McKinsey and Co., Public Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34296-8_9

- The Economist. (2015). The 169 Commandments, 28 March, http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21647286proposed-sustainable-development-goals-would-beworse-useless-169-commandments

- Ellyne, M. J. (2017). The impact of remittances on poverty in Africa:A cross-country empirical analysis. Paper Presented at the 14th African Finance Journal Conference, Zimbabwe.

- Fayissa, B., & Nsiah, C. (2010).The impact of remittances on economic growth and development in Africa. The American Economist.

- Giuliano, P., & Ruiz-Arranz, M. (2009). Remittances, financial development, and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.10.005

- Grier, R. M. (1999). Colonial legacies and economic growth. Public Choice, 98(3/4), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018322908007

- Haugen, H. Ø. (2012). Nigerians in China: A second state of immobility. International Migration, 50(2), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2011.00713.x

- Hines, A. (2014). Migration, remittances and human capital investment in Kenya. Colgate University.https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2015/09/23/five-reasons-to-think-twice-about-the-uns-sustainable-development-goals/

- IFAD. (2017). Remittances, investment and the sustainable development goals. International day of family remittances. Viapaolodidono, 44–00142.

- IMF. (2009). International transactions in remittances: Guide for compilers and users.

- IMF. (2013). Sixth Edition of the IMF’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, s.l:IMF.

- IMF. (2016). Nigeria selected issues, s.l.: International Monetary Fund.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). (2009). International transactions in remittances: Guide for compilers and users.

- Inoue, T., & Hamori, S. (2016). Do workers’ remittances promote access to finance? Evidence from Asia-Pacific developing countries. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 52(3), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2016.1116287

- Kamuleta, K. M. (2014). The impacts of remittances on developing countries. European Union. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2014/437

- Kaphl, R. R. (2018). Relationship between remittance and economic growth in Nepal’. Tribhuvan University journal, 32(2), 249–266.

- Kireyev, A. (2006). The macro economics of remittances: The case of Tajikistan. IMF.

- KNOMAD. (2018). Migration and Remittances; Recent Development and Outlooks.

- Korieh, C. J. (2006). African ethnicity as mirage? Historicizing the essence of the Igbo in Africa and the Atlantic. Dialectical Anthropology, 30(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-006-9004-3

- Koser, K. (2007). International migration: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Lee, K. N. (1993b). Greed, scale mismatch and learning. Ecological Applications, 3(4), 560–564. https://doi.org/10.2307/1942079

- Lucas, R. E. B., & Stark, O. (1985). Motivations to remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 901–918.

- Lumpur, K. (2018). Remittances-an untapped engine for sustainable development |UN DESA| United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://www.un.org

- Magbadelo, J. O. (2003). Africa’s Development: Issues and Prospect. International Studies 40(2), 145–157. https://isq.sagepub.com

- Massey, D. S., & Taylor, J. E. (2004). Introduction. In D. S. Massey & J. E. Taylor (Eds.), International migration prospects and policies in a global market (pp. 1–12). Oxford University Press.

- Mberu, B. U., & Pongou, R. (2010). 2010-06-30. Multiple Forms of Mobility in Africa’s Demographic Giant. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/nigeria-multiple-forms-mobility-africas-demographic-giant

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Unemployment/Under-employment Report Q3 2016.

- Naudé, W. A. (2012). Migration, remittances and resiliences in Africa. Migration, Economic Development. United Nations University (UNU), Tokyo, Japan. Retrieved June 11, 2020, from https://unu.edu/publications/articles/migration-remittances-and-resilience-in-africa.html

- Nurse, K. (2018). Migration, diasporas and the sustainable development goals in least developed countries. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/cdp-backgroundarticles/

- Okafor, E. E., & Obor, D. O. (2014). Social networks and business performance of Igbo Migrant traders in Ibadan, South-West Nigeria. The Nigerian Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 12(2), 63–81.

- Oloruntoba, S. O. (2020). The politics of paternalism and implications of global governance on Africa: A critique of sustainable development goals. Pan Africanism, Regional Integration and Development in Africa. Springer.

- Omobowale, A. O. (2015). Stories of the ‘dark’ continent: Crude constructions, diasporic identity, and international aid to Africa. International Sociology Reviews, 30(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580915571796

- Omobowale, A. O., Falase, S. O., Omobowale, M. O., & Akanle, O. (2018). Migration and environmental crises in Africa. In C. Menjivar, M. Ruiz, & I. Ness (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of migration crises (pp. 1–10). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190856908.013.33

- Orozco, M. (2002). Globalization and migration: The impact of family remittances in Latin America. Latin American Politics and Society, 44(2), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2002.tb00205.x

- Orozco, M., Bump, M., Fadewa, R., & Sienkiewicz, K. (2005). Diasporas, development and transnational integration: Ghanaians in US., UK, and Germany. Report commissioned by citizen International through the U.S. Agency for International Development, Institute for the study of International Migration and Inter-American Dialogue. http://www.thedialogue.org

- Pelican, M., & Tatah, P. (2009). Migration to the Gulf States and China: Local perspectives from Cameroon. African Diaspora, 2(2), 229–244.

- Policy Department. (2014). The impact of remittances on developing countries. European Parliament. EXPO/B/DEVE/2013/34.

- Prakash, K. A., & Mala, A. (2015). Is the Dutch disease effect valid in relation to remittances and the real exchange rate in Fiji? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 21(4), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2016.1153225

- Ratha, D. (2003). Workers’ remittances: an important and stable source of external development finance In: Global Development Finance Washington: World Bank. Article 7. SSRN. Global Development Finance.

- Ratha, D., Mohapatra, S., Ozden, C., Plaza, S., Shaw, W., & Shimeles, A. (2011). Lever aging migration for Africa: Remittances, skills, and investments. TheWorld Bank.

- Rausser, G., Strielkowski, W., Bilan, Y., & Tsevukh, Y. (2018). Migrant remittances and their impact on the economic development of the Baltic states. Geographical Pannonica, 22(3), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.5937/gp22-16988

- Raza, S. A., Arif, I., Ivkovi, A. F., & Suleman, T. (2019). Role of remittance in the development of higher education into premittances receiving countries. Social Indicator Research, 141, 1233–1243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1857-8

- Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Howard UniversityPress.

- Salas, V. B. (2014). International remittances and human capital formation. World Development, 59(C), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.035

- SDGC/A, & SDSN. (2018). Africa SDG index and dashboards report 2018. Sustainable Development Goals Centre for Africa and Sustainable Development Solutions Network website: https://sdgcafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/AFRICA-SDG-INDEX-AND-DASHBOARDS-REPORT-2018-Complete-WEB.pdf

- Singh, S. (2012). New mega trends. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Singh, R. J., Haacker, M., Lee, K. W., & LeGoff, M. (2010). Determinants and macro economic impact of remittances in Sub-Saharan, Africa. Journal of African Economies, 20(2), 312–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejq018

- Spaiser, V., Ranganathan, S., Bali Swain, R., & Sumpter, D. (2016). The sustainable development Oxymoron: Quantifying and modelling the incompatibility of sustainable development goals. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 24(6), 457–470.

- Struckmann, C. (2018). A postcolonial feminist critique of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development: A South African application. Agenda, 32(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2018.1433362

- Swain, R. B. (2017). A critical analysis of the sustainable development goals. In W. L. Filho, et al. (Eds.), Handbook of sustainability science and research, world sustainability series. Springer International Publishing. Springer, Cham. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63007-6_20

- Todaro, M. P., & Smith, S. C. (2003). Economic development (8th ed.). Addison Wesley.

- Topxhiu, R., & Xhelili, F. (2016). The role of migrant workers’ remittances in fostering economic growth: The Kosovo experience. The Romanian Economic Journal, 19(61), 165–192.

- Tung, L. T. (2018). Impact of remittance inflows on trade balance in developing countries. Economics and Sociology, 11(4), 80–95. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2018/114/5

- Tung, L. T., Ly, P. T. M., Nhu, P. T. Q., Thanh, P. T., Anh, L. T., & Phung, T. T. P. (2015). The impact of remittance inflows on inflation: Evidence in Asian and The Pacific developing countries. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences, 10(7), 1076–1084.

- United Nations. (2015). The general assembly. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1

- Van Dalen, H. P., Groenewold, G., & Schoorl, J. J. (2005). Out of Africa: What drives the pressure to emigrate? Journal of Population Economics, 18(4), 741–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0003-5

- Vierderman, S. (1994). The economies of sustainability: Challenges. Jessie Smith Noyes foundation.

- World Bank. (2013). Migration and remittance flows: Recent trends and outlook, 2013-2016. Migration and Development Brief, 21, 1–2.

- World Bank. (2018). World development indicators.https://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators

- World Bank. (2019). Accelerating poverty reduction in Africa: In five charts Retrieved May 27, 2020, from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org

- World Bank. (2020). World Bank predicts sharpest decline of remittances in recent history. http://www.worldbank.org

- World Bank Group, Migration and Development Brief 27. (2017). http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/992371492706371662/-Migration-and-Development-Brief27.pdf.

- World Bank Press Release. (2015). https://worldbank.org/en/news/pressrelease/2015/04/13/remittances-growth-to-slow-sharply-in-2015-aseurope-and-russiastay-weak-pick-up-expected-next-year

- World Bank press release. (2018). https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/04/23/record-high-remittances-to-low-and-middle-income-countries-in-2017

- World Bank/IMF. (2016). Global monitoring report, 2015/2016: Development goals in an era of demographic change. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

- Zhunio, M. C., Vishwasrao, S., & Chiang, E. P. (2012). The influence of remittances on education and health outcomes: A cross country study. Applied Economics, 44(35), 4605 4616. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.593499