Abstract

This paper concerns the management and protection of livestock using Indigenous Technical Knowledge among the Maasai of Kenya with an ultimate goal of promoting agricultural development. A sample of 120 households were selected from four Sub-locations of Loita ward in Narok County and subjected to questionnaire surveys. Additional qualitative data were collected through Key Informant Interviews and Focused Group Discussions. Results from this study show that the Maasai still rear three types of livestock, namely, cattle, sheep and goats. These animals provide them with food (99.2%) and other livestock byproducts. Study findings also reveal that the Maasai still predominantly use traditional methods based on indigenous technical knowledge to manage livestock feeding (85.8%), livestock diseases (89.9%), livestock breeding (74.2%) and livestock protection against predators and other incidental accidents. These findings are also supported by qualitative information from Focused Groups Discussions and Key Informants Interviews. In conclusion, the study established that the use of indigenous technical knowledge to manage and protect livestock among the Maasai have enabled them to sustain high-quality breeds of livestock for food security and income as well as environmental protection. The study recommends that as a policy, the Kenya government should put emphasis on mainstreaming indigenous technical knowledge systems in its agriculture extension programme and scientific knowledge base for sustainable well being and agricultural development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Indigenous Technical Knowledge in livestock management and protection is the only asset in the hands of the small holder farmers. It forms a strong base of knowledge for the society. Livestock require proper management and protection since they are vulnerable to poor nutrition, pests and diseases, danger of getting extinct due to poor breeding as well as injuries due to accidental incidences emanating from predation by wildlife animals, lightning and other causes. The Maasai pastoralist has over time developed ways and practices of caring or protecting their livestock from all the adversities they come across. The livestock are herded on land in order to graze on pastures as a way to ensure their survival from poor nutrition and hunger. Use of herbs helps to control pests and treat diseases and injuries emanating from various accidental incidences while proper breeding and selection is done to ensure livestock survival and continuity.

1. Introduction

Four to seven hundred million indigenous peoples directly depend on pastoralism that has evolved over the last ten thousand years since the domestication of animals (FAO, Citation2016). The long association of pastoralists with livestock has enabled them to acquire enormous range of indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) that is critical for responding to livestock management and protection-related risks at the pastoralists’ level (ibid). Sophisticated knowledge of the natural world is not confined to science but is found in all human societies. Rich sets of experiences and explanations relating to the environments they live in have been developed. These “other knowledge systems” are often variously referred to as ITK, indigenous or local knowledge among other names (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). The ITK encompass the sophisticated arrays of information, understandings and interpretations that guide human societies in their innumerable interactions with their environmental surrounding. It forms the basic component of any country’s knowledge system applied for maintaining or improving people’s livelihoods (Mafongoya & Ajayi, Citation2017).

The indigenous knowledge systems constitute the world’s largest reservoir of knowledge that is utilized in indigenous livestock management practices and techniques. The use of this knowledge allows for the continuous livestock rearing all the year around, an exercise that has little or no chemical effects to degrade the environment (Fre, Citation2018). The many benefits from livestock to pastoralists and the byproducts like livestock manure only serve to conserve the environment. This justifies reasons why the pastoralists stick to this knowledge that also allows good conservation of the environment as well as interaction with other knowledge systems especially extension service where best practices are selected and integrated or up-scaled for adoption (Tyagi et al., Citation2018).

Since the 1990s, world scholarly studies have been going on in an attempt to salvage ITK. One such study done in the recent years by Tyagi et al. (Citation2018) about using indigenous knowledge for agricultural development was successfully done. Another successful study was the one done in Nepal by Khatri et al. (Citation2021), on a framework for incorporating indigenous knowledge systems into agricultural extension organizations for sustainable agricultural development. Several studies then followed in Kenya like the one on ethnoveterinary diagnostic skills that concluded that the pastoralists’ diagnostic skills appeared to be superior to those of agro-pastoralists but with the advent of modern veterinary medicine, the Maasai ethnoveterinary practice appeared to be on the decline (Macharia & Ekaya, Citation2017). Kariuki et al. (Citation2018) in their study found out that the use of ethnoveterinary-medicine was the preferred mode of treatment after investigating the use of traditional health remedies among the Maasai of Loita Sub-County in Narok County, Kenya.

The ITK in livestock protection among the pastoralists has largely depended on their past knowledge, experiences and practices (De Glanville et al., Citation2020). Their experiences and expertise in land use in the feeding of livestock through grazing on pastures, minerals and water have also helped to conserve the biodiversity. Being one of the basic production units, the pastoralists have to be granted grazing rights in land use in order to rear the livestock resource unlike other animals. However, competition for fresh pastures, salt licks and water during grazing times is the main challenge faced by pastoralists from wildlife animals that frequently prey upon them, injuring or infecting them with diseases and parasites (Macharia & Ekaya, Citation2017).

The other challenges include accidental incidences such as livestock raids, laid up traps by hunting communities in forests and lightning that sometimes cause deaths or injuries to livestock ending up with pastoralists incurring huge losses (Wabwire, Citation2016). The traditional application of proper breeding and selection knowledge and skills in livestock protection has enabled the pastoralists to come up with stock well adapted to the environment (Sow & Ranjan, Citation2021). Skills and knowledge on the control of pests and treatment of diseases using local herbal medicine are immense among the pastoralists. This is an art that is mostly with the elderly people and is inherited through word-of-mouth.

The pastoral Maasai of Loita Ward in Narok South Sub-County of Kenya have used ITK to confront natural disasters, such as frequent droughts and diseases, with some form of resilience and flexibility (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). The availability of rainfall in the ward and the presence of the well preserved indigenous forest known as Enaimina Enkiyio (sometimes known as Saruenkiteng—literally meaning save the cow) have helped sustain the livelihoods of the community (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). Value for livestock as an important asset, a wealth reserve and a sacrificial gift among the Maasai is well known. Indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) is applied to protect them though its flow and access through oral channels like stories, riddles and songs is on the decline. Consequently, incidences of pests, diseases, plant poisoning, poor nutrition, improper breeding and other accidental incidences like predation and theft are on the rise due to declining ITK in livestock protection (LP). The Maasai’s vast experiences in the preservation of biodiversity and co-existence with wildlife that increases competition for the already meagre pastures, mauling and cross-transmission of pests and diseases to livestock are unrecorded. Unrecorded too, is the knowledge on environmental care given to forest resource that ensures availability of water, pastures, fodder and herbal medicine used for the control of pests and diseases. Livestock protection information from both ITK and extension service providers (ESPs) is in short supply among the Maasai of Loita Ward. There is a need to document the available information within and without the community dependent on livestock in order to safeguard their livelihoods. In the absence of a profiled ITK in livestock protection and little integration with information from ESPs, the Maasai livelihoods would remain low hence the need for the study. This study thus aims at building on earlier studies by profiling the use of ITK on livestock management and protection among Maasai of Narok County in Kenya. Specifically, the study aims to answer the question; “What are the ITK practices that are traditionally used to manage and protect livestock and their environment among the Maasai in Loita Ward of Narok County”?

The rest of the article is arranged as follows: Section 2 is a brief literature review about indigenous technical knowledge among societies in the world, followed by a description of the research area and the research methods that were used to conduct the study in section 3. Section 4 presents the study results and their discussions. Section 5 is conclusions based on the study findings while section 6 provides recommendations for policy and further studies.

2. The value of ITK among the indigenous societies of the world

The ITK systems are vital to all humanity as the well spring from which all knowledge originates (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). Ethnologists, anthropologists and demographers disagree on the number of indigenous societies there are in the world, but most often the range has been placed at between 6,000 and 7,000 different people (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). The ITK systems are part of the global body of knowledge, but due to historical, political, social and cultural events since the expansion of European and Asian peoples throughout the world, the knowledge systems of indigenous peoples were subordinated to colonizing powers (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021).

Different authors proffer several names and definitions to ITK. It is a whole list of names that include practical knowledge, ethno-ecology, folk knowledge, traditional knowledge (TK), indigenous science, traditional environmental knowledge (TEK), ethno-science, wisdom, culture or simply people’s science or non-conventional knowledge (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). Indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) is stored in people’s heads and is always ready for use by the community when required (Mafongoya & Ajayi, Citation2017). Ezeanya-Esiobu (Citation2019) has broadly defined ITK as that knowledge indigenous or local community accumulates over generations of living in a particular environment. Mafongoya and Ajayi (Citation2017) describe ITK as a knowledge that is holistic in nature, which makes it an adaptable, dynamic system based on skills, abilities and problem-solving techniques that change over time depending on environmental conditions.

Other definitions include one by Sow and Ranjan (Citation2021) who defines ITK as an epistemological vehicle that provides useful values, skills and attitudes that make recipients functional members of the society. Surani (Citation2016) on the other hand regards ITK as social capital or asset used by every community to invest in the struggle for survival, provision of shelter or achievement of control of their own lives. Muricho et al. (Citation2018) summarize ITK as a dynamic system, ever charming, adopting and adjusting knowledge that continue to be discovered, cultivated, harvested and promoted more vigorously for social-economic transformation. The knowledge is unique to a given culture and is embedded in practices and experiences of the local people (Fre, Citation2018).

Knowledge is generally categorized as either being tacit or explicit. Naharki and Jaish (Citation2020) define tacit knowledge as any conventional knowledge held in people’s heads, expressed through action-based skills and not rules. Explicit knowledge, on the other hand, is knowledge that can be expressed in formal or systematic language and can be codified in form of data, scientific formulae and manuals (Smith et al., Citation2018). By its nature, ITK is tacit meaning that it is implicit and thus difficult to systemize.

The ITK is embedded in community practices, institutions, relationships and rituals and depends on what people can see and remember without the aid of microscopes, journals or the written word (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). People often see correlations and understand causality, but where they see gaps in the process, they depend on spirituality to explain them (Mafongoya & Ajayi, Citation2017). The knowledge belongs to the community and those who possess the knowledge possess it on behalf of the community. It is not documented anywhere but passed over to the next generation verbally and through practices (Mafongoya & Ajayi, Citation2017). It is a source of development where the pastoral communities have successfully used it to protect their livestock and sustain their livelihoods from time immemorial.

The ITK is characterized by the fact that it is mostly rural in origin and locally bound, not systematically documented, oral in nature and usually transmitted through personal communication, not integrated into modern scientific knowledge, culture specific and often generated within communities, use is cost-effective, deployment and mobilization not expensive, plays a major role in food production, informal education, poverty alleviation and biodiversity conservation (Sow & Ranjan, Citation2021). The knowledge, as a reservoir of ideas and solutions for development work, should be brought into the mainstream of knowledge in order to establish its place within the larger body of knowledge (Olney & Viles, Citation2019). Thus, the ITK of the Maasai is a largely untapped reservoir of intellectual wealth, experience and valuable asset. The wisdom of ITK is an asset from which all humanity should benefit. One way of using this asset is to ensure that the rights, knowledge and production systems of traditional people are properly valued in economic assessments of development projects (Williams et al., Citation2020). In order to preserve this knowledge base, there is a need to profile and document it for the future generation. It should be integrated into the extension service programme for sustainable improved livestock protection and income generation among the indigenous communities (Anbu et al., Citation2018).

3. Site description and research methods

3.1. Site description

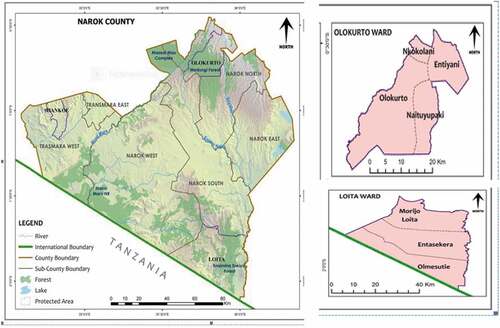

This study was conducted in Loita Ward of Narok County, Kenya. Loita Ward is within a large protected park known as the Maasai Mara National Game Reserve that is famous for wild animals like lions, wild-dogs, hyenas, cheetahs, elephants, rhinos, giraffes, zebras, warthogs and buffaloes (County Government of Narok (CGN), Citation2019). The park attracts tourists who are a source of income (foreign currency) required in Narok County and Kenya as a whole. Loita Ward where the study was done is approximately 1,675.55 km2 in size and is made up of Morijo Loita, Entasekera and Olorte locations (County Government of Narok (CGN), Citation2019). It is occupied by the Maasai community who practice a nomadic life style. They move with their animals from one place to another in search of pastures, water and minerals, lack of which could lead to infections by livestock nutritional deficiency diseases. Cattle, sheep and goats are the main livestock reared here for milk, meat, blood and other products while other foods are gotten by trading with other people (County Government of Narok (CGN), Citation2019). Sometimes livestock are moved all the way to Olokurto Ward in Mau Area where pilot test for this study was done. shows the locations of the study site and pilot test site.

3.2. Research methodology

The overall approach to the study was both quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative data were collected through questionnaire survey. The target population was the 30,130 pastoral Maasai households in Narok South Sub County. The accessible population for the study was 2437 pastoral Maasai households in Loita Ward (GoK, Citation2015). The number of households in Loita Ward by location and sub-location is as shown in .

Table 1. The number of pastoralists’ households by ward, location and sub-location

The survey instrument was administered to 120 Maasai households who are themselves livestock keepers. Loita Ward in Narok County was purposively selected for the study. This was based on the past knowledge, practices and experiences the pastoralists in Loita Ward have in livestock management and protection using ITK.

The sample was drawn from the four sub-locations of Morijo, Olngarua, Olorte and Mausa that constitutes part of Loita Ward through proportionate stratified sampling method. The sample size was proportionately drawn from each sub-location. A sample size of 120 respondents was selected for the study through proportionate random sampling method. This sample size was considered appropriate for the study. According to Jager et al. (Citation2017), “More than just convenient: The scientific merit of homogeneous convenience samples at Arizona State University”, a sample of 100 is considered appropriate for survey type of research for homogeneous sub-groups. Thus, the sample size of 120 taken for the study is high enough to take care of unexpected cases that sometimes occur in field surveys. shows the distribution of household numbers and proportionate sample size.

Table 2. The distribution of household numbers and proportionate sample size

The sampling unit was Maasai household heads who keep livestock in Loita Ward. Proportionate random sampling procedure was adopted to select respondents from all the Sub Locations in Loita Ward. This is because, for a homogeneous population, proportionate sampling offers fair representation of the population of the study.

Key Informant Interviews (KII) was carried out with people purposively selected in order to gain in-depth understanding of the livestock management and protection using ITK. The Key Informants comprised of professionals and cultural specialists. The professionals involved were Veterinary Officer (VO), Livestock Production Practitioner (LPP), Kenya Forest Service Officer (KFSO), Local Government administrator, Environmental Officer, Kenya Wildlife Service Officer from Narok South Sub County and Narok County. Key informants from representatives of the community cultural specialist were herbalists or traditional healers, herdsmen, blacksmiths and seers (Oloibonis) selected among the pastoralists of Loita Ward. The herbalists or traditional healers helped identify herbs, their uses and possible diseases they cure. The herdsmen gave information about livestock herding, theft and predation while blacksmiths provided information about weapons they made for the protection of livestock. Cultural livestock management and protection information was provided by the livestock keepers and cultural experts.

A total of 16 elders and youth respondents were purposively selected from Morijo Loita and Olorte locations for Focused Group Discussions (FGDs). In every location, one Focused Group Discussion session was held. During the session, men and women had their Focused Group Discussions running parallel to each other. This is because the Maasai custom does not allow gender mixing during such discussions. Selection of participants was based on how they are viewed and the positions they held in the Maasai community. Elders were chosen because they are the main custodians of ITK while the youth represented the relatively immediate recipients of learning experiences on ITK in livestock protection. For this study, elders were all men and women above 40 years while youth were those people 18 to 39 years old.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Household characteristics

4.1.1. Gender of the respondents

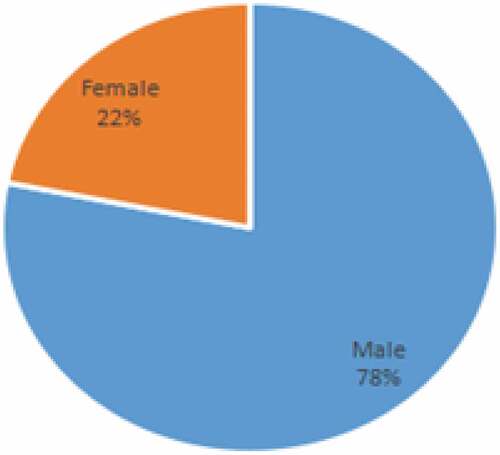

Data on gender of the household head were collected and are presented in below.

The results indicate that out of the 120 Loita Maasai interviewed, 78% were male and 22% were female. Majority of the households are headed by men and less by women. Among the Maasai, gender plays an important role in livestock management and protection using ITK as livestock is generally considered a domain for men, specifically large ruminants such as cattle. Women and children take care of small ruminants such as sheep and goats when men have moved away with cattle in such of green pastures. The Maasai consider livestock a key asset in their livelihood strategies (Nkedianye et al., Citation2020). It offers an entry point for promoting gender balance in rural areas as household members (men and women) have access to livestock which provide them with animal products such as meat and milk daily throughout the year, without seasonal restrictions (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). Livestock management and protection offer the potential for introducing a wide range of project activities relating to gender tasks and responsibilities as well as improved production methods (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). It was noted that typical duties such as milking cows, cooking, cleaning, fetching water and firewood were done by women while men dominated livestock activities. This assertion is also supported by Smucker & Wangui (2016).

4.2. Land tenure system in Loita Ward

All the respondents (100%) agreed that the land they live in Loita Ward is communally owned and granted with grazing rights as pastoralists. The study found out that livestock here faces stiff competition for fresh pastures, natural salt licks and water during grazing times from wildlife animals that frequently kill, injure or infect them with diseases and parasites (cf. Macharia & Ekaya, 2017). Livestock and wildlife freely graze together in the communally owned group ranches, forests and any other open grassland like the plains without any interference from the community.

4.3. Number of livestock owned by the respondents

The number of different types of livestock owned by the respondents is presented in below.

Table 3. Number of livestock owned by respondents (n = 120)

The study found out that the mean number of cattle kept per household was 48, while for sheep was 71 and goats 51. The numbers varied from as low as 5 to a maximum of 1,345. The more the number of sheep and goats (shoats), a pastoralist has the fewer or no sale or slaughter of cattle for small needs (Nkedianye et al., Citation2020). The study found out that most of livestock types reared in Loita Ward were cattle, sheep and goats and although donkeys are reared, they are never eaten nor their milk taken. They are mainly used to carry luggage, fetching water and firewood by women. Livestock is the main source of wealth among the Maasai and anyone without was regarded as being poor (Nkadianye et al. 2020). The average cattle ownership of 48 in Loita almost agrees with that of 50 cattle suggested by Smucker & Wangui (2016) as being the highest in Africa. However, during the Key Informant Interviews (KII), the Narok County Director of Livestock Development viewed the livestock data as likely to drop due to rising pastoralists’ population. The study also found out that the Maasai have the tendency of building up livestock numbers during favourable seasons to ensure the survival of their herds during drought or disease outbreaks. According to Sow and Ranjan (Citation2021), this has often led to overgrazing and environmental degradation. Many livestock as possible are kept so that only a portion of the milk yield is needed for human consumption, leaving plenty for the calves. As a result, Maasai livestock are generally larger and in better body condition than those of their neighbours (Smucker & Wangui, 2016).

4.4. Sources of livestock owned by the respondents

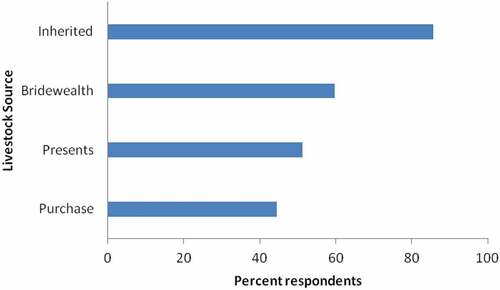

Livestock owned by the respondents in Loita Ward come from different sources as indicated by the results given in .

The study found out that majority (85.7%) of the respondents’ livestock originated from inheritance from parents and other relatives. Others came from bride wealth (59.7%) and presents (51.3%) and 44.5% were purchased.

The study established that whenever a member of Loita community got formal employment, their first salary was used to purchase livestock for those who did not have or to add to the already existing ones. This, according to the discussants of the male FGD, allowed the purchased livestock to multiply in numbers as owner worked. As a result of the increased numbers of livestock, their status of the proprietor improved and his opinions are respected in the community (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). Bride wealth, as also confirmed by discussants during male FGD, is another source of livestock wealth. Although it ranges between three and five cattle, it helps to increase the number of livestock in the kraal or Boma (where cattle sleep). This is despite the Maasai culture regarding this like being a token as their daughters are valueless and thus can never be sold off. Rather, they are given out to go and start new homes and the more the daughters a family has, the higher the likelihood of receiving a higher number of livestock in future (Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

The men and women discussants in their separate FGDs agreed that the bride also attracts more livestock from her relatives before leaving her parents’ home. As if this is not enough, once the bride arrives at her new home, she is allocated a herd of cattle, from which all her sons will build-up herds of their own, overseen by their father, who also makes gifts of cattle to his sons over the course of his life (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). When the parents die, the eldest son gets the residue of his father’s herd, and the youngest inherits the residue of his mother’s allocated cattle. Daughters inherit nothing at all (Nkedianye et al., Citation2020). The bottom line is, the more the livestock the relatives being inherited have, the more the livestock their heirs are likely to inherit from them (Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

The study further found out that through livestock presents or exchanges as gifts, the Maasai community are able to establish close ties by calling each other (men or women) names relating to the type of animal they have exchanged. For instance, if it is a heifer, men address each other as entawuo meaning they have exchanged a heifer and if a man and woman paashe (Smucker & Wangui, 2016). Many other present exchanges exist such as a man or woman giving the other a sheep from which they address each other as paker or pakine if a goat. Therefore, depending on one’s favour from the community, one would easily accumulate many livestock gifts that may end up growing into herds or flocks of cattle, sheep and goats over time thereby improving the social status of the recipient (Smucker & Wangui, 2016).

4.5. Uses of livestock and livestock manure

Besides the many other uses, livestock also produce useful manure after digestion of pastures and other feeds obtained during grazing and foraging. This manure spreads out nutrients over the landscape thereby reincorporating fertility at the same time improving the overall soil quality in a natural process besides other uses.

4.5.1. Uses of livestock

below presents the uses of livestock as stated by the respondents of Loita Ward.

Table 4. Uses of livestock by Loita Ward Maasai

The entire life of a Maasai in Loita is nearly all centred around livestock. The study found out that 99.2% of the foods (milk, meat, blood) the respondent consume come from livestock. Most Maasai derive their pride or prestige (52.1%) from livestock which are also used to support their other numerous cultural activities (64.7%). Sale (51.3%) of livestock is not given a priority and comes as a last resort. Sheep and goats are the ones sold for meeting needs at home including education of children (49.6%) or slaughtered in order to spare cattle for other big occasions.

Findings from Key Informant Interviews and from focus group discussions reveal that milk, meat and blood from cows and small stock are still the main pillars of the Maasai diet. In fact, among the Maasai exist a meat eating feast locally known as olpul, where men slaughter animals once in a while in order to rejuvenate their health by preparing meat in many ways including roasting and boiling with the inclusion of herbs to make their bodies healthy once more. Women and children also get their portion (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). Occasional use of herbal medicine in soups to help the community to care for their own health besides that of livestock was taken care of. This was supported by Smucker & Wangui, (2016), who also noted that berries and other wild fruits were used by women and children to supplement the diet gotten when looking after animals.

4.5.2. Uses of livestock manure

Manure as a livestock by-product that allows the natural growth of stinging nettle fed upon by livestock during drought and also it favours conservation agriculture practice where fodder and other crops grow. This mutual kind of relationship is vital, as livestock manure improves soil fertility that supports the growth of pastures, fodder and other crops that in turn are fed upon by livestock to produce milk, meat and blood for the survival of pastoralists. The uses of livestock manure cannot be underrated as presented .

Table 5. Uses of livestock manure (N = 120)

The respondents that use the dung to smear or plaster their houses (inkajijik in Maasai language) are that (44.5%). 28.6% use it to smear injured parts of plants where herbal medicine has been drawn from while 27.7% use it to support conservation agriculture and support the naturally growing plants such as the stinging nettle that livestock feed on during drought.

The use of fresh dung on the injured part of the herbal plant or tree where medicine has been extracted or peeled off from by the community helps to heal the plant. This fact is scientifically supported by Kotut & McCrickard, (Citation2021), by explaining that the dung accelerates callus formation and regrowth of cambium layer for plant healing. The use of manure is environmental-friendly and improves energy and nutrient cycling (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). The study found out that the community understands that manure adds fertility to the soils and that their large number of livestock produce a lot of dung and urine that could benefit them in many ways.

4.6. Livestock management and protection using ITK

Livestock require proper management and protection since they are vulnerable to poor nutrition or hunger, pests and diseases, danger of getting extinct due to poor breeding as well as injuries due to accidental incidences emanating from predation by wildlife animals, lightning and other causes. The Maasai pastoralist has over time developed ways and practices of caring or protecting their livestock from all the adversities they come across. The livestock are herded on land in order to graze on pastures as a way to ensure their survival from poor nutrition and hunger. Use of herbs helps to control pests and treat diseases and injuries emanating from various accidental incidences while proper breeding and selection is done to ensure livestock survival and continuity. The documentation of these management and protection practices is very important as it also encompasses biodiversity conservation.

4.6.1. Indigenous technical knowledge on pasture management

Poorly fed livestock cannot survive and yet meet the reasons for which they are reared. They need proper feeding. Fortunately, the Maasai livestock are generally larger and in better body condition than those of their neighbours. The reason given by Smucker & Wangui, (2016), for the good performance is that, the Maasai raise livestock through natural pastures that make them much healthier and the meat and other animal based products they offer come with much more nutrients.

Feeding of livestock during drought

The way Loita Ward pastoralists feed their livestock during extreme drought is indicated in .

Table 6. Livestock feeding during drought in Loita Ward

The study found out that the respondents took decisions to save their livestock from hunger based on the progression of the severity of drought. Initially, livestock are moved to other areas with pastures (85.8%) and if this hunger persists, palatable tree branches (60%) of trees like Oltepesi (Acacia tortilis) and Thorntree/whistling thorn or Olkiloriti (Acacia nilotica) are fell (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). With further persistence of drought, livestock start feeding on rare plants (49.6%) like the stinging nettle (Urtica masaica), Manyatta or Olmakutian grass (Elusine jaegeri) or start grazing indiscriminately (43.7%) in areas they are not supposed to graze like roadsides and even in towns. Some respondents rarely hire land for grazing their livestock (0.06%) or buy feeds (8.3%) for them.

Findings from the FGDs revealed that the Maasai community is capable of skillfully tending their animals and mostly operate with mixed herd of cattle, sheep, goats and donkeys thereby making intensive use of these animals and taking advantage of their different reproduction rates and feeding habits. Allowing mixed species to graze together, that is, grazers (cattle and sheep) and browsers (goats) including donkeys, ensures that there are survivors during drought as different species are adapted differently.

The deep understanding of their livestock requirements in terms of best vegetation type to feed them with have helped to sustain the life of Loita people. Their long time association with the natural grasslands has made the Maasai know each plant’s seasonality, nutritional value, toxicity and medicinal properties for the different animals they keep (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). Findings from FGDs indicate that Emurua (Cynodon dactylon) grass was given as an example of vegetation that increases lactation in livestock. Kariuki et al. (Citation2018), also agree with the study that the community have much knowledge in the different types of medicinal plants that exist in Maasai land. For example, they orally take Oloirien (Olea africana) herb and cider charcoal mixed with milk to counter the poisonous effects of Oldule (Ricinus communis).

In areas far away from forests, pastoralists either buy feeds or hire land for grazing livestock rather than going to search pastures in urban areas or allow indiscriminate grazing of livestock (Otieno, Citation2018). Pastoralists in Loita avoid mountain areas or long distance walk with livestock to avoid infections and diseases from strange livestock as well as cold and abrupt weather changes (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). In extreme drought, animals may end up eating rare or unconventional feeds and sometimes poisonous plants like Poison arrow tree or Olmorijoi (Acokanthera schimperi). This is rare in Loita Ward though.

Maintenance of quality pastures

The goal of pasture management is to produce an optimum, sustained yield of livestock while maintaining the land and watersheds in a healthy condition. Maasai ensured availability of sufficient quality pastures for livestock throughout the year by performing the following practices indicated in .

Table 7. Ensuring quality of pasture in Loita Ward

The study found out that respondents mainly apply three different methods to ensure livestock have sufficient and quality pastures in their farms. They mainly practice controlled grazing (66.4%) and paddocking (11.8%) and others (12.6%) leave their farms fallow or allow free range grazing.

The Loita Maasai traditional pastoral systems use different ways to preserve natural ecosystems. In controlled grazing, it is noted, the pastoralists preferred rotational grazing where a variety of livestock such as cattle, goats, sheep and donkeys are grazed in succession as they utilize different parts of the range’s plant life. This diversity is crucial in pastoral patterns of subsistence (Otieno, Citation2018). Rotational grazing also allows livestock movement to different sections of the pasture every set period of time in order to maintain healthy and nutritious forages. The fact that livestock can move to areas with rainfall, greener pastures and away from pests gives them an advantage over the agricultural crops (Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

Sometimes, large pastures of land are sectioned off into paddocks or smaller parcels using either permanent or temporary fencing to allow the pastoralists to effectively control grazing. It is established that many paddocks allow livestock a longer period away before returning to the same paddock. This allows slow grazing giving pasture enough time to regenerate while still allowing enough time out of the paddock for good growth.

Some KII herders confirmed that free range grazing is practiced in Loita Ward. They went further to explain that in free range grazing, livestock are let free to graze on grass without control. However, this kind of grazing require vast land where livestock could move as much as possible in pursuit of pastures yet allow adequate recovery of plants before the pasture is grazed again without degrading land through erosion. Where grazing is well managed with good time control, land remains healthy and productive. With proper application of ITK, pasture management could improve the livelihoods of Loita Maasai.

4.6.2. Control of livestock diseases using ITK

A disease is generally an interruption of the normal functioning of the body of an animal. Only in cases of serious illness, are experts consulted by pastoralists (Wabwire, Citation2016). The Loita Maasai, use herbs, to protect livestock against pests or parasites and ailments—thereby curtailing losses. Herbs are used to treat livestock since herbal products have less adverse side effects than other medications though it is only important that consumers consult traditional herbal medicine specialists for guidance (Ruggeri, Citation2017).

Preferred medicine type for Treatment of animal diseases in Loita Ward

The respondents stated the most preferred types of medicine used to treat sick animals as outlined in .

Table 8. Use of ITK in herbs for the treatment of livestock diseases in Loita Ward (n = 120)

Asked which type of medicine they preferred in the treatment of their livestock, majority (89.9%) of the respondents stated that they used herbs, 33.3% used conventional medicine while 49.8% used both medicines. For herbs, the study found out that, the respondents often go to their nearby bushes or forests from which they extract medicines from live plants. Ruggeri (Citation2017) defines the herbal medicine as naturally occurring, plant-derived substances or organic chemicals used to treat livestock illnesses. Unfortunately, prior to independence, the colonialists abolished traditional herbal medicine regarding it as witchcraft through the “Witchcraft Act, in 1925”, though, this was reversed on attainment of Kenya’s independence in 1963 (ibid).

After independence, ITK was no longer regarded as primitive or even frowned upon, by well-educated civil servants and professionals (Macharia & Ekaya, Citation2017). Rather, it is being sought after by scientists and is no longer suppressed (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). Twenty-five percent of the drugs prescribed worldwide are derived from plant concoctions, Ruggeri (Citation2017), that are administered as digestives and excitants and help to treat different diseases and relieve symptoms (Sow & Ranjan, Citation2021). The people of Tanzania and Kenya in Kiswahili language call medicinal plants miti shamba which literally means plants derived from the garden or field or shamba (Kotut & McCrickard, Citation2021). The Loita Maasai call herbs ilkeek (plural) or olchani (singular). Plant herbs could contain dozens of ingredients like fatty acids, sterols, alkaloids, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins which help in healing from diseases (Ruggeri, Citation2017).

The community’s participation in identifying various trees and shrubs with medicinal values in Loita was great as the extension officers also helped in searching for botanical names of the locally identified herbal plants. Even after relocation through Maasai-British Agreement of 1904 over 100 years ago, from Laikipia, the Maasai are still experts in disease diagnosis, treatment, prescription and preparation of appropriate herbs using ITK (Tiampati, Citation2016). The herbs are used for treating different diseases. About 18 species of plants were reported as used for killing 7 different types of pests. This illustrates the in-depth knowledge of the Maasai plant resources (Smucker & Wangui, 2016).

Certain herbs were found to be shared between livestock and humans for the treatment of similar diseases in Loita Ward. For example, Olmisinkiyioi (Rhus natalensis) treats fractures in both man and livestock while Seketet (Myrsine africana) treats diarrhoea. This reduces the time and labour that would have been used for fetching separate herbs. Many of the herbal medicines are broad spectrum, thus, they treat more than one ailment and may be used in more than one country (Ruggeri, Citation2017). For example, Aloe vera herb is used to treat constipation and worm infestations in Kenya. This has been attributed to the more than 75 potentially active components including vitamins, minerals, saccharides, amino acids, anthraquinones, enzymes, lignin, saponins and salicylic acids found in Aloe vera alone (Ruggeri, Citation2017).

The herbs originate from the community’s single biggest natural and non-gazetted trust land indigenous forest in Loita Ward measuring about 30,000 Ha of closed canopy forest dominated by pastures, rivers, podo and cider indigenous trees with over 90% canopy cover as per Kariuki et al. (Citation2018). The forest provides the community with building materials, fodder, rivers, wood weapons and other commodities besides traditional herbal medicines. The areas outside Enaimina Enkiyio Forest in Loita Ward are approximately 4% tree cover. The Loita Maasai have jealously guarded Enaimina Enkiyio Forest so as to maintain their very spiritual relations and culture-based ITK through practices that have sustained and protected their land, forests and other natural resources (Naloolo Explorers, Citation2018).

The customary governance that helps to protect the forest resource is led by the seer or oloiboni and a strong Council of Elders (Naloolo Explorers, Citation2018) and remains largely undisturbed. The culture of the Loita Maasai forbids any community member from indiscriminatingly cutting down a tree, either for firewood or for any other purposes. They have learnt that if unprotected, their forests could be invaded and destroyed.

Findings from KIIs and FGDs show that for purposes of extracting herbal medicine, pastoralists in Loita Ward are forbidden from interfering with the taproots or removing the entire bark of a tree for herbal extraction. According to their cultural belief, one can only use tree branches for firewood and fibrous roots for herbs. If the bark of a tree has medicinal value, then only small portions of it could be removed by creating a “V” shape in the bark. The wound is then sealed using fresh cattle dung or wet soil which helps in healing the wound on a tree as leaving it unattended, culturally is believed to be an abomination ((Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

Preferred plant parts for treating livestock diseases

The respondents use ITK in the harvesting of branches, small tree barks and roots as the plant parts for the extraction of herbal medicine as is indicated in .

Table 9. Plant parts used as source of medicine for livestock protection (n = 120)

The application of ITK in the use of herbal medicine among the respondents is very important in every aspect of livestock treatment. Different parts of the plant are sustainably harvested from which herbal medicine is extracted. In this study, majority (75.6%) of the respondents extracted their medicine from branches or stems, 74.8% from small tree barks, 32.5% fibrous roots and few (7.5%) from leaves. Some respondents occasionally through relatives and friends brought rare herbal medicine from far areas outside Loita Ward to avoid fast depleting theirs. This is the gap that researchers and the Kenya Forest Service (KFS) need to exploit in order to supply the pastoralists with relevant seedlings for replacing the used trees or plants. Other plant parts used for herbal or botanical medicine extraction are seeds, berries and flowers. Leaves and taproots are rarely used possibly because they are responsible for photosynthesis and manufacture of plant food and responsible for the growth of the whole plant respectfully (Sow & Ranjan, Citation2021).

Focus groups findings show that the Maasai community’s love for conserving the biosphere is not in doubt. The Maasai community value trees for their beauty and products which include pastures, fruits and berries, medicine, fuel wood and construction materials. To protect the forests, there are restraints on the customary right of access to forests in order to check the indiscriminate use of forest resources. The taboos and restrictions also ensure the conservation of the big and rare trees are not cut anyhow before the small shrubs and grass which regenerate quickly. Thus, the people of Loita are only allowed to sustainably fell trees from which they split materials for building houses (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). This is agreed in line with Kotut and McCrickard (Citation2021), where conservation of the environment is required for posterity.

The study also established that, the part of the plant to be used often depends on the prevalence and size of the particular plant species. The roots of a rare, slow-growing tree would rarely be used, if at all, so as to ensure a sustainable supply of the medicine. However, some diseases are treated by using many different species of plants. For example among the Loita Maasai, apart from East Coast Fever (ECF) being treated using oloirien (Olea africana) only, it is treated with at least twelve other different plants. It is difficult therefore for such a disease to miss herbs for its treatment any time soon. Some of the plants are used for treating both human beings and domestic animals. Osokonoi or the East African Green Wood (Warburgia salutaris) is used for treating stomach ache in humans or bloat in livestock. Some herbs are used for treating the same condition in almost all livestock like Olmame (Talinum portulacifolium) is used to help remove retained placenta in cattle, sheep and goats in Loita Ward (Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

4.6.3. Livestock breeding and selection in Loita Ward

Most of the animal breeds developed and used by indigenous communities have traits that allow them to adapt to local environments and climates, resist pests and diseases and satisfy local cultural preferences (Fre, Citation2018).

Livestock breeding

The importance of livestock breeding to the Maasai of Loita Ward is presented in above.

Table 10. Reasons for livestock breeding in Loita Ward (n = 120)

The reasons why the pastoralists of Loita Ward breed livestock is to ensure their continuity (44.5%) and to get better stock (34.5%) that is big and heavy (21%) to genetically survive sustainably in the harsh environment in which they are born. Whilst breeding may seem like a modern technology, according to Kariuki et al. (Citation2018), improving livestock breeds is not a new practice since they were domesticated and selected for their adaptation to specific climates. The community control and decide which individuals of animals shall produce the next generation bearing in mind the gestation period (270 to 285 days for a cow and 150 days for a goat or ewe) for various livestock (Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

Breeding systems in Loita Ward

The livestock breeding systems in Loita Ward is shown in .

Table 11. Systems used in livestock breeding in Loita Ward (n = 120)

Selective breeding involves breeding of livestock with the intention to improve desirable and heritable qualities in the next generation. From the study, the Loita Ward respondents preferred traditional breeding system (74.2%). The modern breeding programme may either use artificial insemination (AI) or natural service (Tiampati, Citation2016). This cross breeding approach is applied with the intention of creating offspring that share the traits of both lineages to produce an animal with hybrid vigour (the improved or increased function of any biological quality in a hybrid offspring) (Fre, Citation2018).

Arising from centuries’ traditional practice of livestock raids, present-day zebu cattle of the Maasai are very heterogeneous (Smith et al., Citation2018). This is sanctioned by the Maasai legend which relates that Enkai (God) sent them cattle at the beginning of time and gave them the sole right to keep them safe (Smucker & Wangui, 2016). Compared with cattle belonging to the surrounding communities, Maasai cattle are the largest and in the best condition. This is largely due to the generous amount of milk the young calves get. As a rule, the Maasai have so many cattle that only a portion of the milk is needed for human consumption while there is plenty left for the calves (Macharia & Ekaya 2017).

The modern (41.7 %) approach which some of the respondents used is termed as artificial insemination (AI). Other Loita pastoralists applied both (37.5%) natural or AI approaches as the study indicated. The study noted that improved bulls provided by the County Government of Narok to every ward were being shared by pastoralists for the improvement of livestock (County Government of Narok (CGN), Citation2019). Generally, with their large and healthy livestock, the Maasai livestock are bound to increase production and subsequently improve their livelihoods, due to this integrated modern of livestock breeding technologies.

Traditional traits mostly selected in livestock breeding

In , the traits preferred by Maasai pastoralists when selecting breeds of livestock for breeding are presented.

Table 12. Common traits selected during breeding of livestock in Loita Ward

The studies found out that the most preferred livestock traits in Loita Ward were those of food (milk, meat and blood) production (79.0%). The other traits are drought tolerance (78.8%), resistance to pests and diseases (72%), animal colour (47.5%) and long distance walk (15.1%). Though scientists may want to regard the Maasai cattle as much improved compared to other African zebus, McHugo et al. (Citation2019) considers them to be typical zebu and mostly black in colour with varied horn shapes and hump that contains very juicy fatty meat something the pastoralist like very much which is a product of many years of selective breeding.

Thus, breed development is a dynamic process of genetic change driven by environmental conditions. The fact that ecosystems are dynamic and complex, human preferences change has resulted in the evolution of breeds until recently and a net increase in diversity over time (FAO, Citation2016). In harsh environments where crops will not flourish, livestock keeping is often the main or the only livelihood option available. The most preferred trait in Loita Ward was for food (milk, meat and blood) production (79.0%). The current food production contribution to agricultural gross domestic product in developing countries is 30% and is projected to increase to about 40% by 2030, according to FAO (Citation2016).

The peculiar thing about the Maasai cattle is that they are adapted to live under any climatic conditions (FAO, Citation2016). According to this study, 74.8% of the respondents believed that their livestock were drought tolerant, and therefore, well adapted in this area or environment because of their ability to convert particular types of vegetation or poor pasture and feeds into locally distinct foods or for the production of specific products. Animals with such kind of trait could manage to live under inadequate water supply, adapted to browsing during the long dry seasons and trek long distances in search of water (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). That is the main reason why the Maasai breed big and heavy animals with the average adult live weight for males and females being 300–400 and 275–385 kg, respectively (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). This is much less than the 80% world meat requirement by 2030 according to World Bank (FAO, Citation2016).

The development of the drought tolerance trait has given rise to breeds that effectively regulate their body temperature against thermal stress and better adapted to hot weather. This is due to their improved degree of thermo-tolerance at the cellular and physiological levels according to Henry et al. (Citation2018). That way, the Maasai zebu cattle breeds are able to withstand very harsh environmental conditions due to adaptation. These livestock also tolerate pests and diseases. The trait of pests and disease tolerance enable the livestock to withstand pests, for example, (ticks) and diseases like foot and mouth disease, trypanosomiasis and heartwater (Naloolo Explorers, Citation2018). In their endeavour to improve the pest and diseases resistance trait among livestock, the Loita pastoralists sometimes source breeding stock from as far as the neighbouring countries.

The Maasai African indigenous cattle breeds have unique colours that distinguish them from cattle from other communities (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). Colour is the other trait for which the Maasai of Loita Ward breed their livestock for. The main colours observed in Loita Ward livestock by the researcher include; white (enaibor), black (erok), red (enayokie) and brown (embarikoi). Cattle with more than one colour are deemed more beautiful and prestigious to own like enkiteng lerai (ash or moon coloured), enkiteng sambu (brown, white and red coloured) and enkiteng mugie (dark brown). The yellow colour is associated with colostrum and therefore also considered attractive (Ombija, Citation2018)

4.7. Protection of livestock using ITK

4.7.1. Livestock predators in Loita Ward

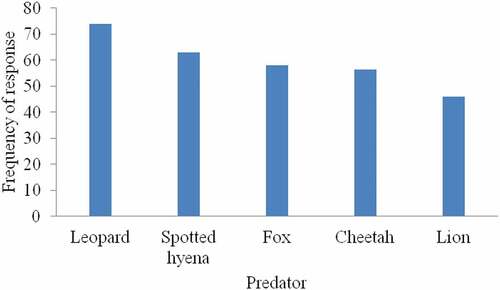

There are a number of wildlife animals that are cannibalistic in nature and depend on meat for their survival. Wild animals that commonly predate upon livestock in Loita Ward are presented in .

The pastoralist identified five different predators common in Loita ward (), as: leopard (74%), spotted hyena (63%), fox (58%), cheetah (56.3%) and lion (46%). This Ward acts as a wildlife dispersal area for the Maasai Mara National Game Reserve. The movement of wild animals into and out of the ward causes predators to follow them and in turn meet with livestock.

The Maasai’s success in conserving the environment without threatening the existence of the region’s wildlife can be attributed to pastoralism itself (Wainaina, Citation2019). Traditionally, Maasai did not eat their cattle but drank milk and blood instead without relying on wildlife except during severe drought when wildlife was hunted down. Such a system enabled the Maasai to retain a fairly stable wildlife population that thrived well. Ordinarily, the Maasai hardly hunted wildlife as they abhorred game meat although eland and buffalo meat is like cattle to them (Wainaina, Citation2019).

The study observed that the pastoralists in Loita still cared and maintained their livestock as they coexisted with wild animals. This could be explained by the fact that livestock assure them of food security and alleviate poverty as they conserve biodiversity for the continuity of life (Wainaina, Citation2019). The favourable environment in Loita Ward for both livestock and wildlife creates competition for available grass (Kariuki et al., Citation2018) thereby attracting marauding animals that become a permanent threat to human life and to herd especially during dry period.

According to the study, leopard (74%), hyenas (63%), fox (58%) and cheetah (56.3%) were the most notorious in that order in Loita as they primarily killed small stock that included goats, sheep and calves. They were said to mostly attack livestock at night. The lions (46%) preyed upon adult cattle and donkeys while grazing during daytime. The study found out that only less than 15.1% of the households’ livestock had not been affected by predators while the remaining 85% of the households had lost at least an animal to the predators as illustrated in .

Table 13. Number of cases of livestock attacked by predators (n = 120)

ii. Traditional techniques of protecting livestock from predation using ITK

The different traditional techniques respondents use to protect livestock is presented in above.

Table 14. Techniques used to protect livestock from predators (n = 120)

The respondents identified seven different techniques the residents of Loita Ward used to combat predator menace. The study was able to establish the fact that the community tries as much as possible to refrain themselves from killing predators by applying methods that help to keep them away. The methods used include bonfires (65.5%), caricatures (59.7%), vigilante groups (56.3%), laying traps (55.5%) and fencing around the homesteads (43.7%). Only, when predators repeatedly kept preying upon livestock in large numbers, is when the community is forced albeit reluctantly to hunt them down (8.3%) or on the extreme poison them (4.2%).

The initial step, the study found out, that was taken by the pastoralists to prevent wildlife from predating upon livestock was to firmly fence their homesteads with thorny acacia bushes preferably Olkiloriti or ilera or eluai. To reinforce this, the pastoralists occasionally light bonfires (locally known as olengoti) outside of the fence with the intention of constraining predators from marauding livestock at night (Tiampati, Citation2016). The fire is lit in a vantage position where elders are able to see raiders or livestock coming back home in the evening from grazing fields and ensure they are all back, well fed, healthy or infected with pests or sick to prompt any necessary action. The pastoralists have a unique talent of being able to recognize and identify almost all the livestock (each animal has its own unique identifiable characteristic) without physically counting them.

Sometimes elders would entertain themselves around the bonfire by playing enkeshui an equivalent of the Bao Game where small pebbles are moved in small holes made either on the ground or on a log-like piece of wood (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021). Their noises and the pungent or choking smell from the burning decomposing manure would help keep the marauding animals away from livestock. Caricatures of human or metals knocking at each other at the slightest blow of the wind were also used to scare away wildlife, though; they diverted their route away once the caricatures became familiar. Caricatures were then frequently adjusted to outsmart the wildlife (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021).

The other method of controlling predators is where the youths conglomerate and keep a watchful or close eye on the movements of nocturnal animals. The vigilante groups as they are commonly called mostly comprise of village youth who keep vigil at night when wildlife become a nuisance. They move around homesteads at night, and, in case of any livestock in danger or distress, they take it from any charging marauding predators. Besides protecting livestock around homestead, the Loita Ward warriors’ also have a duty to protect the community and track down on any lost or stolen livestock (Kariuki et al., Citation2018).

The hunters’ traps could be another threat to livestock, though they are laid to illegally catch wildlife which they use as their source of meat (Gai, Citation2020). Accidental trapping of livestock may sometimes raise tensions or animosity but this is immediately thrashed out by the hunters and the pastoralists themselves. On the other hand, slanting sharpened sticks intended to scare away the predators that become notorious by jumping over the fence are placed on the route they use to access livestock. Most often than not the notorious nocturnal animals change their route far away and the livestock are left safe. The interest here is to scare away the predators but not to kill them (Tiampati, Citation2016).

Predator poisoning only started in the beginning of the 1980s, when the human population started to explode across Africa and competition for space and food increased sharply where land owners and pastoralists learnt that pesticides and herbicides could also be employed to kill predators (Edwin, Citation2018). The first poisoning took place on a male and a female lion where a goat or cow carcass was laced with chemicals that killed them; other culprits followed this by lacing the tip of the arrow with a lethal substance from the bark of the Acokanthera schimperi and killed lions, hyenas and leopard that predated upon their livestock. The chemical in the plant was found to contain a compound that in small doses could arrest the heart of a large mammal and has been popular for centuries (Pollini & Galaty, Citation2021).

4.7.2. Traditional techniques used to counter lightning occurrences in Loita Ward

Lightning strike comes with a lot of losses to both human and livestock. The Loita Maasai reduce losses of livestock emanating from lightning strikes by avoiding sheltering under trees (64.7%) and using cultural practices or techniques (80.7%) to thwart any such future occurrences by wearing rubber (tyre or akala) shoes (25%) as shown in .

Table 15. Traditional ways used to deal with lightning occurrences in Loita Ward

Lightning strikes injure about 240,000 people and animals and kill 24,000 each year where the nearly 100 million volts of electricity in a lightning strike is about five times hotter than the sun (Heutinck, Citation2018). Of the 700,000 people and livestock stroke each year, 90% of them survive lightning exposure but 80% of those survivors are left with permanent physiological and neurological damages (Moyo & Xulu, Citation2021). On the other hand, if a tree is hit, the sap in it will explode into a super-hot gas thereby shattering the tree and consequently causing death to it and any livestock or human sheltering under it, if any (Kariuki et al., Citation2018). That is a reason enough to make the community avoid sheltering livestock under trees, in water (as they are good conductors of electricity), hilltops or ridges during rains.

4.7.3. Traditional weapons used by Maasai pastoralists to protect livestock

presents the traditional weapons used to protect livestock by the Maasai.

Table 16. Traditional weapons used for protecting livestock from predation, raids or attacks

It is right to state here from the onset that the Maasai hate killing of wildlife as they believe every living thing has a right to live and therefore does not deserve to die. At the same time, the community has a duty to protect livestock that was bestowed upon them by God at the beginning of time. Therefore, their weapons are used to defend livestock and themselves against any attacks by wild animals, raids and any other kind of attack. The different traditional weapons or means used include; spears (77.3%), culture (66.7%), swords (58%), bows and arrows (52.9%) and clubs (40.3%).

5. Conclusions

Given the relative success of using ITK in managing and protecting livestock thus increasing food production, many argue that it should be profiled, documented, protected and incorporated in scientific knowledge so it can be widely applied as the model for agricultural development and as a means of ensuring household and national food security. This paper has also shown that the Maasai still largely rear three types of livestock, namely, cattle, sheep and goats that provide them with meat, milk and blood and other byproducts like livestock manure. Thus livelihood of the pastoral Maasai is still largely dependent on livestock. This paper has outlined numerous ways the Maasai have effectively applied ITK to manage and protect their livestock. These include; i) pasture use and management, ii) drought management, iii) pest control, iv) livestock manure use, v) treatment of animal diseases, vi) livestock breeding management, vii) livestock traits selection, viii) coexistence of Maasai livestock with wildlife, ix) weapons used to protect livestock, and (x) protection of livestock from other causes of accidents such as lightning. This is a testimony that indigenous knowledge regarding livestock production though is considered as old as domestication of various livestock species; it forms a strong base of knowledge for the society. Most technologies used in ITK for livestock management and protection practices in Loita Ward are environmental-friendly. The forests are traditionally protected with the resources therein like herbs harvested in a sustainable manner. There is also a harmonious coexistence of the Maasai, his livestock and wildlife thereby conserving biodiversity for future generations.

6. Recommendations

Given the success with which the Maasai have managed and protected their animals in various aspects, the study recommends that the government of Kenya to finalize the policy on traditional cultural knowledge to protect it from being copied and pirated without the real owners benefitting. The development of a policy to protect ITK by government of Kenya is important as envisaged in Article 11 of Kenya’s Constitution that recognizes culture as the foundation of the nation and cumulative civilization of the Kenyan people. This knowledge can further be protected by mainstreaming it into various subjects covered by the new Kenyan education curriculum known as Competencies Based Curriculum (CBC) started in 2017. The areas of breeding, pastures or feeding, environment and wildlife could fit well in biology, agriculture or social sciences among others. Covering ITK practices in vernacular radio and TV studios could also be an added advantage for the interested people.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge the Narok County Department of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries, all pastoralists in Loita Ward of Narok South Sub-County in Narok County, local leaders, both professional and cultural experts who freely contributed the information that was used to write this paper. We appreciate the enumerators for their due diligence in collecting accurate data regarding the use of Indigenous Technical Knowledge by the Maasai of Narok.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Josephat Kereto

Josephat Kereto is an extension science specialist with the Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. This research paper emerges from his PhD work in Narok County that is inhabited by the Maasai pastoral community. His PhD work is in Agricultural extension. Together with his research team, over the years his research work has focused on Maasai agro-pastoralists in Olokurto Ward of Narok County. He has worked as an extension expert in various counties namely; Kericho, Wajir, Garissa, Bomet and Narok County in Kenya. His current environmental orientation is on integrating Indigenous Technological Knowledge systems and scientific knowledge systems for sustainable livelihoods among pastoralists. Accumulated over the years, the development of Indigenous Technical Knowledge system is an area that is lagging behind among scholars yet very important and more so during this era where climate change is posing extra burden to farmers.

References

- Anbu, I. V., Asokhan, M., Chinnadurai, M., Arunachalam, R., & Balarubini, M. (2018). (1Potential of indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) through agricultural extension in selected districts of Tamil Nadu, India. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 27(2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJAEES/2018/43489

- County Government of Narok (CGN). (2019). Livestock annual reports. Department of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Fisheries.

- de Glanville, W. A., Davis, A., Allan, K. J., Buza, J., Claxton, J. R., Crump, J. A., Halliday, J. E. B., Johnson, P. C. D., Kibona, T. J., Mmbaga, B. T., Swai, E. S., Uzzell, C. B., Yoder, J., Sharp, J., & Cleaveland, S. (2020). Classification and characterization of livestock production systems in northern Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 15(12), e0229478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229478

- Edwin, D. (2018). Why poison is a growing threat to Africa’s Wildlife. Deadly chemicals are now a weapon of choice for those who see lions, elephants, and other wild animals as threats to livestock and property. National Geographic Magazine. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/article/poisoning-africa-kenya-maasai-pesticides-lions-poachers-conservationists

- Ezeanya-Esiobu, C. (2019). Africa’s indigenous knowledge: from education to practice. In indigenous knowledge and education in Africa. Frontiers in african business research. pp 55-80,Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6635-2_5

- FAO (2016). The contributions of livestock species and breeds to ecosystem services. Retrieved June, 24, 2020 from http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6482e.pdf

- Fre, Z. (2018). Knowledge sovereignty among African cattle herders. UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353114

- Gai, A. B. (2020). Impacts of Involuntary Resettlement on Livestock Production and performance among the Maasai pastoralists of Rapland Village, Olkaria, Kenya [ Unpublished thesis], University of Nairobi

- GoK. (2015). Kenya national bureau of statistics. Narok County Statistical abstract. Government Printer

- Henry, B. K., Eckard, R. J., & Beauchemin, K. A. (2018). Review: Adaptation of ruminant livestock production systems to climate change. Animal Journal, 12(S2), s445–s456. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731118001301

- Heutinck, E. (2018). Maasai and feeding their cattle. How can the Maasai restore the Savannah Ecosystem so that their cattle and wildlife have sufficient and healthy feed on the Middle Long-and Long Term [ Unpublished Thesis], Aeres University of Applied Sciences.

- Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., Marc, H., & Bornstein, M. H. (2017). More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homegenous convenience samples. In N. A. Card (Ed.), Development Methodology (Vol. 82). 2 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mono.v82.2/issuetoc

- Kariuki, P. M., Onyango, C. M., Lukhoba, C. W., & Njoka, T. J. (2018). The role of indigenous knowledge on use and conservation of wild medicinal food plants in Loita Sub-county, Narok County. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 28(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.9734/AJAEES/2018/45032

- Khatri, S., Khanal, S., Santosh Kafle, S., & Tejada Moral, M. (2021). Perceived attributes and adoption of indigenous technological knowledge on agriculture - a case study from Bhirkot municipality of Syangja District, Nepal. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 7(1), 1914384. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1914384

- Kotut, L., & McCrickard, D. S. (2021). Trail as heritage: Safeguarding location-specific and transient indigenous knowledge. In 3rd African human-computer interaction conference (AfriCHI2021), March 8–12, 2021, Maputo, Mozambique. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 11. https://doi.org/10.1145/3448696.3448702

- Macharia, P. N., & Ekaya, W. N. (2001). Maasai indigenous knowledge on range vegetation analysis, utilization and management. Journal of Human Ecology, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2001.11907620

- Mafongoya, P. L., & Ajayi, O. C. (editors). (2017). Indigenous knowledge systems and climate change management in Africa.

- McHugo, G. P., Dover, M. J., & MacHugh, D. E. (2019). Unlocking the origins and biology of domestic animals using ancient DNA and paleogenomics. BMC Biology, 17(98). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-019-0724-7

- Moyo, I., & Xulu, S. (2021). Public knowledge, perceptions and practices in the high-risk lightning zone of South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7448. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147448

- Muricho, D. M., Otieno, D. J., & Oluoch-Kosura, W. (2018). The role of pastoralists’ indigenous knowledge and practices in reducing household food insecurity in West Pokot, Kenya: A binary probit analysis. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 10(7), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2017.0871

- Naharki, K., & Jaish, M. (2020). Documentation of indigenous technical knowledge and their application in pest management in Western Mid Hill of Nepal. SAARC Journal of Agriculture, 18(1), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.3329/sja.v18i1.48397

- Naloolo Explorers. (2018). Loita: The Forest of the Lost Child. Enaimina Enkiyio Kenya. https://naloolo.com/2018/10/17/loita-forest-of-the-lost-child/

- Nkedianye, D. K., Ogutu, J. O., Said, M. Y., Kifugo, S. M., De Leeuw, J., Van Gardingen, P., & Reid, R. S. (2020). Comparative social demography, livelihood diversification and land tenure among the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice, 10(17). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-020-00165-2

- Olney, S., & Viles, H. (2019). Indigenous peoples and climate change: Emerging research on traditional knowledge and livelihoods. International Labour Organisation, Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch. ILO Publication.

- Ombija, R. (2018). Invented in Sweden, made within Sunny Nairobi. Online Travel Operations Pty LTD Copyright © 1999-2018 Travelstart. Retrieved June 25, 2021, from https://www.travelstart.co.ke/servlet/newsletter-signup

- Otieno, J. (2018). City hall arrests illegal Maasai herders, holds over 500 cows. Star Newspaper, 01 January 2018.

- Pollini, J., & Galaty, J. G. (2021). Resilience through adaptation: Innovations in Maasai livelihood strategies. Nomadic Peoples, 25(2), 278–311(34). https://doi.org/10.3197/np.2021.250206

- Ruggeri, C. (2017). Herbal Medicine Benefits & the Top Medicinal Herbs More People Are Using. Retrieved January 8, 2022, from https://draxe.com/health/herbal-medicine/

- Smith, B. M., Gathorne-hardy, A., Chatterjee, S., & Basu, P. (2018). The last mile: Using local knowledge to identify barriers to sustainable grain legume production. Frontier in Ecology and Evolution Journal, 6(102). https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00102

- Sow, S., & Ranjan, S. (2021). Indigenous technical knowledge (ITK) for sustainable agriculture in India. Agriculture and Food: E-Newsletter, 3(1). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349278516

- Surani, K. (2016). Indigenous knowledge systems and rangeland governance in Northern Tanzania. Tanzanian Journal of Population Studies and Development, 23(1&2), 1–31.

- Tiampati, D. O. (2016). Information needs and seeking behavior of Maasai pastoralists of Kajiado County [ Unpublished Thesis]. Moi University.

- Tyagi, S., Singh, M. K., Singh, B. D., & Sunil, K. (2018). Conservation and management of indigenous technical knowledge for livelihood upliftment of small and marginal farmers in rural areas. International Journal of Inclusive Development, 4(2), 53–58. New Delhi Publishers. India

- Wabwire, D. (2016). A philosophical examination of the nature of indigenous knowledge and implications for education with reference to Maasai community of Kenya [ Unpublished Thesis], Kenyatta University.

- Wainaina, B. (2019). Traditional Music & Cultures of Kenya. Retrieved January 6 2022, from http://www.bluegecko.org/kenya/tribes/maasai/livestock.htm

- Williams, P. A., Sikutshwa, L., Sheona Shackleton, S., Reed, D. E., Shirkey, G., Lei, C., Abraha, M., & Chen, J. (2020). Acknowledging indigenous and local knowledge to facilitate collaboration in landscape approaches— Lessons from a systematic review. Land, 9(331). https://doi.org/10.3390/land9090331