Abstract

sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is struggling with unemployment and food insecurity, which became severe with the spread of COVID-19 pandemic and its containment measures. This paper aimed to present a systematic review of food insecurity and unemployment crisis in sub-Saharan Africa under COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, 1026 papers were retrieved from different sources, and 53 papers were included for the synthesis after screening and selection of retrieved papers. The review paper revealed that household livelihoods were disrupted, which deepened the crisis in the region. Unemployment was severe particularly in times of lockdowns and working hours loss in 2020 were above 10% in Eritrea, Cape Verde, and Uganda. COVID-19 lockdown measures caused a 10.6% fall in Ethiopia’s agri‐food system, about 19.8% agri-food system GDP loss in Ghana, a 6–15% increase in food insecurity of Nigeria, and 10% of Kenyan farmers faced food shortage. Moreover, Kenya and Uganda’s food insecurity raised by 38% and 44%, respectively, and a 44% drop in per adult equivalent food expenditure of rural Uganda. The review paper pointed out that social protection measures, regional cooperation, a strong financial sector, and domestic borrowing to mitigate the socio-economic effect of COVID-19 and rapid economic recovery.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

COVID-19 has affected the social and economic well-being of most citizens in Africa. The economic impact is already severe, particularly for oil-exporting countries and those significantly rely on the global supply chain. The effect of COVID-19 for workers includes job loss, income reduction or loss, health risks due to susceptible working conditions, and reduced productivity. It undermines the food security of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) directly, by disrupting food systems, and indirectly, through the impacts of lockdown on household incomes and physical access to food. It severely affected food accessibility, followed by its availability compared to other food security dimensions. The review calls attention to social protection measures, regional cooperation, and strengthening domestic financing to ease the socio-economic effect of the pandemic and boost economic recovery.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has created public health, economic, and political crises throughout many countries in the world (Greer et al., Citation2020). The pandemic hit China first and the negative spillovers to the rest of the world are substantial as the country accounts for 17% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 11% of world trade, 9% of global tourism, and above 40% of global demand for some commodities (Baldwin & Mauro, Citation2020). It has disrupted the socio-economic welfare of most African citizens. Real GDP in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is estimated to shrink by −1.6% in 2020, about 5.2% lower than the predicted growth in 2019 due to the spread of COVID-19 and lower commodity prices (IMF, Citation2020). The pandemic has a severe economic effect on countries highly dependent on oil export and significantly benefited from the global supply chain (Ozili, Citation2020). Oil price falling by half reduced SSA’s net export revenues by $30 billion in 2020 (Willem, Citation2020). Nigeria could lose up to $19 billion as the country reduced its crude oil exports in 2020 compared to predicted exports without COVID-19 (AU, Citation2020).

The spread of COVID-19 pandemic disrupted food security and food supply chains in developing countries (Erokhin & Gao, Citation2020). Food accessibility was severely affected followed by its availability compared to other food security dimensions (Workie et al., Citation2020). The food insecurity crisis may persist longer due to the pandemic effect on the economic decline, raised poverty, food supply disruption (Udmale et al., Citation2020). COVID-19 intensify worrying levels of hunger and undernourishment, which could aggravate as the pandemic disrupted household’s livelihood in Africa (Aborode et al., Citation2021). Food insecurity was widespread in Africa even before the COVID-19 pandemic devastated the continent economy (Mohamed et al., Citation2021). The hunger index and child mortality for most African countries are already high and became alarming to extremely severe (Boretti, Citation2021).

The effect of COVID-19 for workers includes job loss, income loss, health risks due to vulnerable working conditions, and reduced productivity (ILO, Citation2020d). Firms in developing countries have high liquidity constraints, which constrained their capacity to pay their employees during the pandemic. The problem became severe in households that have inadequate credit access and poor saving (Gerard et al., Citation2020). The sectors that employed a high portion of workers in the informal employment, and workers that do not have social protection and access to health service are hardly hit by the spread of the pandemic (ILO, Citation2020e). Over 70% of the workforce in the informal sector does not have any social protection. The pandemic has a shocking effect on income and livelihoods, as well as food and nutrition security of workers throughout food supply chains in Africa (Lawson-Lartego & Cohen, Citation2020).

Demand and supply-side shocks induced by COVID-19 collapsed African growth prospects in 2020 and beyond. The pandemic closed domestic economic activity, people unable to work, production diminished, jobs are lost, supply chains disrupted, welfare and livelihoods worsen, and poverty and vulnerability to risk rise due to COVID-19 in SSA (Adam et al., Citation2020; IMF, Citation2020). The crisis became severe in the region that faces several external shocks, including trade deficit and tighter global financial conditions, and a sharp drop in commodity prices (IMF, Citation2020). The pandemic deteriorates SSA food security by disrupting food systems, and its lockdown impact on household income and physical access to food indirectly (Chiwona-Karltun et al., Citation2021; Devereux et al., Citation2020). The pandemic control measure severely affected the demand-size economy and physical access to food, even though it has weakened food production, processing, and marketing (Devereux et al., Citation2020; Teachout & Zipfel, Citation2020). For example, movement restrictions in the planting season of staple crops have exacerbated food security challenges in many SSA countries (Ayanlade & Radeny, Citation2020).

As there is no comprehensive evidence, a synthesis of the compounded effects of COVID-19 on the existing food insecurity and unemployment treats in SSA is crucial for policymakers and researchers. Thus, this paper aimed to provide a holistic review of empirical evidence on the dual COVID-19 crisis in SSA food insecurity and unemployment. To attain this goal, the following research questions were defined: (1) How COVID-19 disrupt the existing food insecurity situation of SSA? (2) How much the pandemic devastated employment in SSA? In doing so, the review paper makes two important contributions. First, the review explores the effect of COVID-19 on the prevailing food insecurity and unemployment of the region. Second, it synthesizes the future policy directions countries would adopt for containing the associated socio-economic impact of COVID-19 and other pandemics.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. First methods used for this review were presented, secondly literature review and discussion, which comprises unemployment, food insecurity, and poverty under COVID-19 sub-sections. Thirdly, COVID-19 policy directions were discussed. Finally, the conclusion of the review was presented.

2. Methodology

In this study, a systematic review approach was followed to explore food insecurity and unemployment crisis under COVID-19. The review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines that provide a standard accepted method. The paper followed a systematic approach that started with a search for relevant literature in international databases (Google Scholar, Science Direct, Web of Science, and SCOPUS). We developed the search strategy using keywords including “food in/security”, “poverty”. “un/employment”, “COVID-19”, “Sub Sahara Africa” using OR and AND operators in the article title, abstract, and keywords. To get many eligible studies, reference lists of the eligible articles were manually searched to get additional papers, which is relevant for the synthesis. The identified articles were imported into the bibliographic software EndNote X9. Thus, (1) papers published in the English language, (2) published after the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, and (3) Published papers (article, commentary, letter, short communication) and unpublished paper (working paper, report, policy briefing, and documents) were included in the synthesis to obtain comprehensive evidence.

In total, 1,026 references were retrieved in the literature search, including scientific articles, working papers, unpublished works, and reports. Primarily, two of the authors reviewed titles and abstracts of retrieved references independently to determine paper eligibility to be included based on the abovementioned criteria. Hence, studies retrieved in the literature search were screened and divided into (1) titles considered relevant and (2) titles considered not relevant for the analysis. All disparities were resolved by consensus between the researchers. Accordingly, 138 papers were considered relevant for full-text retrieval after the initial screening of titles and abstracts. From these 138 papers, 53 studies were identified to be included in this systematic review after conducting a full-text review. Empirical evidence from included articles supported with descriptive analysis using data extracted from international organization databases such as World Bank, International Labor Organization (ILO), Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). A summary of papers included for the systematic review were presented in Appendix that shows the country of study and its thematic area of studies included in this review.

3. Literature review and discussion

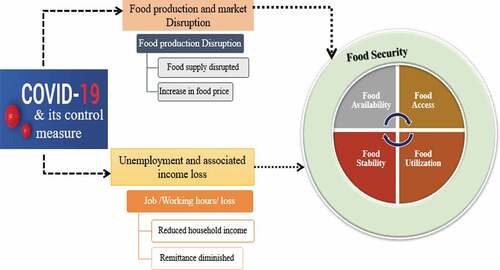

COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted food market supply and the control measure shocked unemployment and associated income loss. These together affect the food security of households through influencing all four dimensions of food security (food availability, food access, food utilization, and stability). The existing literature showed that food production and market disrupted by the pandemic lockdown measures that lead to significant damage to the food security of households in the region. COVID-19 pandemic that resulted in a loss of jobs or income, market disruption, and a rise in food price highly disrupted food access. As a result, households faced difficulty of accessing food physically due to lockdown and economically due to rise in food price and income loss. Food utilization and stability dimensions were hardly hit over time by the pandemic in SSA, which was already a food insecure region before the pandemic ().

3.1. Unemployment and COVID-19

During the first quarter of 2020, COVID-19 resulted in 155 million full-time job losses globally (ILO, Citation2020b), which increased to 495 million full-time jobs losses in the second quarter of 2020 (ILO, Citation2020c). The pandemic significantly affected youth, particularly women in the labor market (UN, Citation2021). Over 75% of young people employed in the informal economy are enormously exposed to the crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic severely affecting young people in three dimensions: (1) disruptions to education, training, and work-based learning; (2) enlarged worries for job seekers; and (3) job and income losses, together with the worsening quality of employment (Lee et al., Citation2020). Hence, young people face the pain of existing job loss and worry about future job search processes (Crayne, Citation2020). Sustaining business operations are also difficult for small and medium enterprises, which significantly weaken informal and casually employed workers’ income (ILO, Citation2020a).

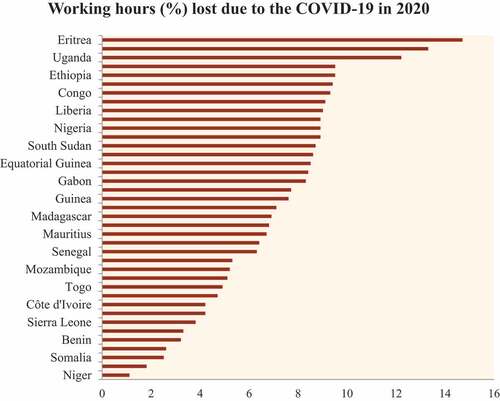

The strict lockdown and school closures severely disrupted work on paid and unpaid economies (Casale & Posel, Citation2021). The school closures in SSA mostly affected the income of private school teachers, public transport, and urban services workers (Teachout & Zipfel, Citation2020). The pandemic raised unemployment, mainly lower-skilled workers enduring most of the economic crisis (Chitiga-Mabugu et al., Citation2020). The impact of COVID-19 on South Africa’s labor market resulted in a 36.8% unemployment rate in the final quarter of 2019 (ILO, Citation2020f). South Africa’s job posting in the travel industry declined by 14% in the first two weeks of March 2020 (Willem, Citation2020). Wage earnings diminished by 30%, lower educated workers’ earnings fell by over 40% in South Africa (Arndt et al., Citation2020). Gender inequalities have grown in the labor market as the pandemic severely affected women than men workers (Casale & Posel, Citation2021). The pandemic increased working hours lost in SSA by 7.2%, while Eritrea, Cape Verde, and Uganda recorded greater working hours lost in 2020 ().

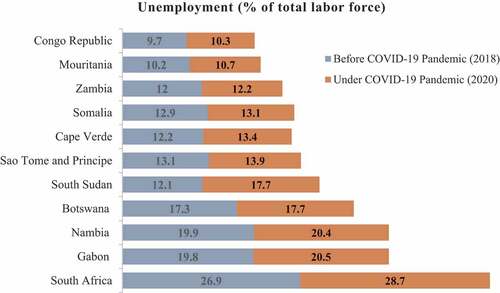

The pandemic worsen unemployment in Nigeria, which substantially reduced government revenue, and intensifies poverty (Oruonye & Ahmed, Citation2020). In addition, the quarantine measures in Somalia lead to an economic burden for most of the population relies on daily paid jobs (Gele, Citation2020). Employment in Kenya would have dropped by 11.9% annually (Nechifor et al., Citation2021). The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on SSA countries for which unemployed labor force is greater than 10% is presented in . The percentage increase in unemployment of the total labor force was largest in South Sudan (5.6%), South Africa (1.8%), and Cape Verde (1.2%) respectively, due to the pandemic compared to before COVID-19.

Figure 3. Unemployment due to COVID-19 in the most affected SSA countries.Source: Extracted from World Bank Database

Kenya flower farms have diminished production and employment, which directly and indirectly affected 500,000 people reliant on the sector (Willem, Citation2020). The pandemic employment impact remains small in rural Ethiopia, since most of the workforce is engaged in agriculture. However, the adverse employment effect in urban areas was tangible (Hirvonen, Citation2020). Hence, the lockdown measures dropped urban household income by 19.0% compared to 12.6% in rural households of Ethiopia (Aragie et al., Citation2021). A study in Ethiopia reported that two-thirds of respondents’ income was reduced, and 50% could not satisfy their food needs (Abay et al., Citation2020). The income from work decreased by about one-third after the start of the pandemic in low-income households of rural Kenya (Janssens et al., Citation2021).

3.2. Food insecurity and poverty under COVID-19

The COVID-19 crisis worsens the food security and nutrition of millions of people (UN, Citation2020), leaving over 100 million people chronically undernourished and making the goal of ending hunger hard to achieve (UN, Citation2021). Millions of farmers are facing a large food crisis in Africa. Agribusiness in the continent is exposed to diverse threats such as climate change, pests, and diseases, and now COVID-19, which makes the problem worse (Fernando, Citation2020). The spread of COVID-19 and its control measures threatens the goal of eliminating hunger and poverty in SSA. The disruption of supply chain resulted in food insecurity of vulnerable segments of the population, migrants, informal workers, and seasonal farmworkers are losing their jobs which influence food demand (Poudel et al., Citation2020).

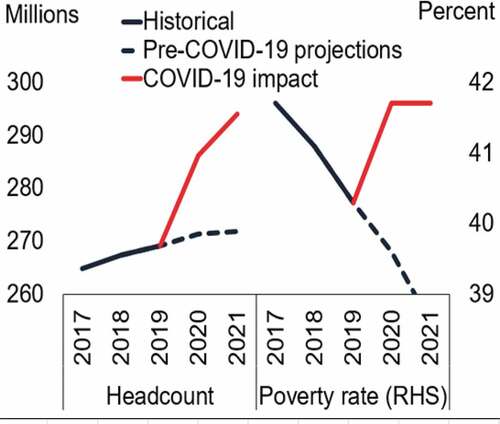

The effect of COVID-19 on food security begins at the farm level, which is conveyed through agri-food chains, such as market access, logistics, and food processing caused by lockdowns and cross-border restrictions. In the end, it leads to income loss, limited availability, and access to food that altogether affected food insecurity and poverty (Nchanji & Lutomia, Citation2021). The prevailing food insecurity crisis compounded with social injustice and income inequality is severe for the urban poor immigrants in South Africa (Odunitan-Wayas et al., Citation2021). Most of African immigrants are without a social welfare safety net (Odunitan-Wayas et al., Citation2021). The pandemic sharply increased poverty headcount of low-income countries and it has increased poverty rate that was falling prior to the outbreak of the pandemic ().

Figure 4. COVID-19 effect on poverty headcount and rate in low-income countries.Source: World Bank (Citation2020) and UN (Citation2021)Note. Red line reflects the baseline projection for the impact of COVID-19 on poverty headcounts and rates.

The lockdowns in SSA expected to finish 30% of population savings, diminished the resilience capacity to future shocks. The outbreak of COVID-19 resulted in an additional 9.1% of SSA population immediately falling into extreme poverty (), with about 65% of this resulting from lockdowns only (Teachout & Zipfel, Citation2020). Households with little education levels and highly rely on labor income in South Africa experienced real income shock that would jeopardize the food security of these households (Arndt et al., Citation2020). The lockdown lead people to lose their jobs and have difficulties in providing food for their families in Sierra Leone (Buonsenso et al., Citation2020), affected urban refugee livelihoods, and increased income insecurity in Uganda (Bukuluki et al., Citation2020). The associated containment measures severely disrupted aquatic food value chains (Belton et al., Citation2021), and suffered economically vulnerable informal workers in Nigeria below the poverty line. They are thinking “Hunger Virus is deadlier than Corona Virus” (Omobowale et al., Citation2020). Ghana’s partial lockdown leads to a further 3.8 million people temporarily becoming poor (Amewu et al., Citation2020). A decline in income due to COVID-19 resulted in 8.8% temporary increase national poverty rate in Ethiopia (Aragie et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Impact of containment measures in SSA

Nigeria’s national lockdown measures are associated with a 12% drop in nonfarm business activities and a 6–15% increase in food insecurity (Amare et al., Citation2021). This lockdown negatively affected farm labor availability and transportation, that shrinks food production and raised food insecurity (Inegbedion, Citation2020). Even though no direct restrictions were imposed on Ethiopian agriculture sector, the sector faces a 4.7% loss in output and a 10.6% fall in the agri‐food system sector (Aragie et al., Citation2021). Ghana’s urban lockdown caused about 19.8% agri-food system GDP losses (Amewu et al., Citation2020) and the pandemic led to 10% of Kenyan farmers suffering food shortage (Nchanji & Lutomia, Citation2021).

The disruption to agricultural productivity and markets negatively affected livelihoods, particularly the most vulnerable households. The disruption of bean value chains and lockdown restriction in Eastern and Southern Africa diminished bean consumption, especially in urban and peri-urban areas due to market closure and restricted transportation, and high food prices (Nchanji et al., Citation2021). The estimated rise in world rice price by 25% would reduce rice consumption in Papua New Guinea by 14% and a 12% decrease in household incomes (Schmidt et al., Citation2021). In Senegal, 29% of consumers have reduced rice consumption, 41% decreased vegetable consumption, and 47% decreased fruit consumption due to the pandemic (Van Hoyweghen et al., Citation2021).

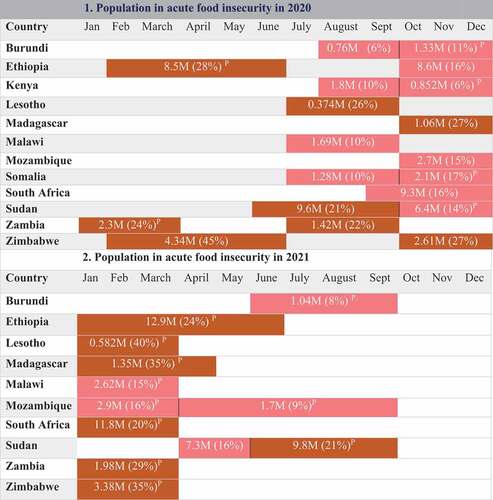

According to the results of IPC, the population in phase 3 and above requires urgent humanitarian action classified under acute food insecurity. This includes households classified in phase 3 (crisis), phase 4 (emergency), and phase 5 (Catastrophe/ Famine). These households are facing problems in accessing food or unable to meet their minimum food needs, and an extreme lack of food and/or other basic needs even after full employment of coping strategies. Thus, 12 SSA countries’ population under acute food insecurity in 2020 − 2021 are presented in above for the highlighted range of months, the period in which the survey was conducted. The percentage shows the percentage of population in acute food insecurity from the surveyed population.

Figure 5. Population under acute food insecurity (in millions).Source: Summarized from IPC analysis of countries (2021)

The effect of COVID-19 is severe in several Eastern Africa countries recovering from droughts, severe flooding, and worst desert locust invasion (FAO, Citation2020). Food imports in Kenya declined by 14.4% due to the price increase in imported commodities. This decreased imported food products affordability and leads to lower consumption of cereals, bread, oil, and fats (Nechifor et al., Citation2021). Livelihoods in Somalia are being destroyed and people are receiving little or no financial support to cope with the problems (Herring et al., Citation2020). The percentage of food-insecure respondents raised by 38% and 44% in Kenya and Uganda, respectively, and regular fruits consumption declined by 30% during the pandemic (Kansiime et al., Citation2021). Within a month COVID-19 restriction, the incidence of food insecurity significantly increased by 8% in Kenya (Huss et al., Citation2021). COVID-19 lockdown reduced the income of households in rural Uganda that led to 44% fall in per adult equivalent food expenditure (Mahmud & Riley, Citation2021). In Ethiopia, household food insecurity increased by 11.7% and widen the size of food gap by 0.47 months after the inception of the pandemic (Abay et al., Citation2020).

COVID‐19 pandemic adversely affected food prices through the demand and supply chains of the food market in SSA, and ecological shocks aggravated the rise in food prices. The pandemic has a devastating and extended influence on food prices of maize, sorghum, rice, but the lockdown only influenced maize prices in the region (Agyei et al., Citation2021). The severity of food insecurity in Burkina Faso is growing among poor households due to several factors such as a rise in food prices (4%—8%) and a decrease in households’ incomes (between −1.47 and −3.19%; Zidouemba et al., Citation2020). Price changes for different vegetables due to pandemic-related trade disruptions in Ethiopia (Hirvonen et al., Citation2021). Value chain disruptions triggered sudden price changes and an increase in price volatility. The Daily food price monitors the consumer prices of the 14 main food products in SSA countries and compiles the average food price increase from 14 February 2020 to April 2021 ().

Figure 6. Average daily food prices change due to COVID‐19 in SSA.Source: Extracted from FAO Database (FAO, Citation2021).

4. COVID-19 economic policy directions and lessons

Besides health and behavioral measures to control COVID-19, SSA countries should adopt flexible fiscal policy to ease the intertwined social, economic, and health challenges of the pandemic (Bitanihirwe & Ssewanyana, Citation2020). The review paper summarized and synthesized the following policy actions needed in SSA to mitigate the socio-economic effects of COVID-19 and other pandemics:

4.1. Increase social protection measures

In developing countries, transfer policy to help vulnerable households in case of rapid and severe shocks like COVID-19 is vital (Arndt et al., Citation2020; Gerard et al., Citation2020). A comprehensive social protection strategy that includes intensifying the social insurance system, building the prevailing social assistance programs recommended in low-income countries (Gerard et al., Citation2020; Renzaho, Citation2020) to offer people resources to sustain economic productivity while holding jobs (Yaya et al., Citation2020). Hence, countries in SSA should enforce policies to maintain the pandemic without affecting the food supply chain and their people’s food security (Poudel et al., Citation2020). sub-Saharan African countries should adopt flexible and effective policies and legislation that harness and formalize informal trade and eliminate supply chain difficulties (Renzaho, Citation2020). Hence, SSA countries should ensure adequate income protection while providing job search assistance and support; adopt social protection measures to enable poor, vulnerable, and marginalized rural and urban households to meet their basic needs during the pandemic and recovery period (Beyene et al., Citation2020).

4.2. Build and maintain regional (inter-institutional) cooperation

The COVID-19 crisis has proven that international cooperation is weak and easily collapses in times of crisis (Elliott et al., Citation2020). We need a renewed form of global solidarity to enable Africa to overcome this crisis (OECD, Citation2020). In addition, Africa should have local solutions to face COVID-19 pandemic (Boum et al., Citation2021). Policies that promote economic diversification and reduce their reliance on external aid are crucial by fostering continental free trade such as Africa Union and Regional Economic Communities should be promoted and fostered (OECD, Citation2020; Yaya et al., Citation2020). sub-Saharan Africa needs investment and political will to support the health sector, and promote public-private partnerships to prevent, control, and manage future outbreaks (Osseni, Citation2020). Therefore, reinforcing regional cooperation; boosting partnerships and cross-border coordination are key to mitigate the pandemic effect and foster economic recovery.

4.3. Strengthen the financial sector and domestic borrowing

Developing strong financial institutions to support business recovery in a shorter period is needed (Kansiime et al., Citation2021). The COVID crisis has reminded the role of financial resilience and a strong but flexible prudential regulation for stabilizing income and living standards (Giese & Haldane, Citation2020). In times of global pandemic and uncertainty in external funds, central banks should provide liquidity and credit support to domestic financial markets and this should be provided to individuals, entrepreneurs, and corporations to help them cope with the adverse effects of the crisis (Beyene et al., Citation2020; Ozili, Citation2020). Endorsing and harnessing savings and borrowing capacity, mainly for low-income earners and rural households vital to withstand shocks (Kansiime et al., Citation2021). Fiscal measures such as easing corporate tax to maintain businesses’ cash flow, emergency credit lines, loan programs at low-interest rates, and guarantee facilities are critical for promoting businesses operation. A summary of COVID-19 Economic policy directions were presented in below.

Table 2. Summary of COVID-19 economic policy directions

5. Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic brings not only human health, but it also resulted in a significant socio-economic disruption in the world, more severe in Africa. This paper attempted to provide a compressive synthesis of empirical evidence on the impact of COVID-19 to food insecurity and unemployment in SSA. We conducted a systematic review using 53 studies, which were selected from 1,026 retrieved references. The paper affirmed that COVID-19 worse unemployment, food security, and nutrition of millions of people in SSA, specifically the most vulnerable segment of the population, migrants, informal workers. The rise in total labor force unemployment was cruel in South Sudan (5.6%), South Africa (1.8%), and Cape Verde (1.2%) due to the pandemic. Working hours lost were higher in Eritrea, Cape Verde, and Uganda and those countries recorded over 10% working hours lost in 2020.

The paper explores that the paths on the impact of COVID-19 pandemic to food security begin at the farm level, which is transmitted across agro-food chains, such as market access, logistics, and food processing due to disruptions caused by lockdowns, and cross-border restrictions. The disruption of food systems and markets can have an adverse impact on livelihoods with severe consequences on food and nutrition security. The lockdown measures resulted in a 10.6% fall in Ethiopia’s agri‐food system, an estimated 19.8% agri-food system GDP loss in Ghana, a 6–15% increase in food insecurity in Nigeria. In addition, food insecurity increased by 38% and 44% in Kenya and Uganda, respectively, and per adult equivalent food expenditure decreased by 44% in rural Uganda. The review paper pointed that social protection measures, regional (inter-institutional) cooperation, and strong financial sector are key policy responses to ease the socio-economic effect of COVD-19 and rapid economic recovery.

Abbreviation

FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; GDP: Gross Domestic Product; ILO: International Labor Organization; IPC: Integrated Food Security Phase Classification; SSA: Sub Saharan Africa;

Consent for publication

The authors confirmed that this paper has not been submitted for publication elsewhere.

correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ebrahim Endris Mekonnen

Ebrahim Endris (MSc) is a lecturer and researcher in the department of agricultural economics at Woldia University, Ethiopia. His research interest comprises agricultural marketing, value chain, impact evaluation, adoption, livelihood, loan repayment, economics, and entrepreneurship.

Andualem Kassegn (MSc) is a lecturer and researcher in the department of agricultural economics at Woldia University, Ethiopia. His research interest emphasizes impact evaluations, economics, marketing, livelihood and income diversifications, food security, poverty, and economic policy analysis.

References

- Abay, K. A., Berhane, G., Hoddinott, J., & Tafere, K. (2020). COVID-19 and food security in Ethiopia do social protection programs protect? The World Bank.

- Aborode, A. T., Ogunsola, S. O., & Adeyemo, A. O. (2021, January). A crisis within a crisis: COVID-19 and hunger in African children. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 104(1), 30–17. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1213

- Adam, C., Henstridge, M., & Lee, S. (2020). After the lockdown: Macroeconomic adjustment to the COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Suppl._1), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa023

- Agyei, S. K., Isshaq, Z., Frimpong, S., Adam, A. M., Bossman, A., & Asiamah, O. (2021). COVID‐19 and food prices in sub‐Saharan Africa. African Development Review, 33(S1 1–12). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12525

- Amare, M., Abay, K. A., Tiberti, L., & Chamberlin, J. (2021). COVID-19 and food security: Panel data evidence from Nigeria. Food Policy, 101 (1) , 102099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102099

- Amewu, S., Asante, S., Pauw, K., & Thurlow, J. (2020). The economic costs of COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from a simulation exercise for Ghana. The European Journal of Development Research, 32(5), 1353–1378. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00332-6

- Aragie, E., Taffesse, A. S., & Thurlow, J. (2021). The short‐term economywide impacts of COVID‐19 in Africa: Insights from Ethiopia. African Development Review, 33(S1 1–13). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12519

- Arndt, C., Davies, R., Gabriel, S., Harris, L., Makrelov, K., Robinson, S., Levy, S., Simbanegavi, W., van Seventer, D., & Anderson, L. (2020, September). Covid-19 lockdowns, income distribution, and food security: An analysis for South Africa. Global Food Security, 26 (1) , 100410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100410

- AU. (2020). Impact of coronavirus (Covid 19) on the African economy. Africa Union.

- Ayanlade, A., & Radeny, M. (2020). COVID-19 and food security in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications of lockdown during agricultural planting seasons. NPJ Science of Food, 4(13), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-020-00073-0

- Baldwin, R., & Mauro, B. W. D. (2020). Economics in the time of COVID-19. Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Press.

- Belton, B., Rosen, L., Middleton, L., Ghazali, S., Mamun, -A.-A., Shieh, J., Noronha, H. S., Dhar, G., Ilyas, M., Price, C., Nasr-Allah, A., Elsira, I., Baliarsingh, B. K., Padiyar, A., Rajendran, S., Mohan, A. B. C., Babu, R., Akester, M. J., Phyo, E. E.,and Thilsted, S. H. (2021). COVID-19 impacts and adaptations in Asia and Africa’s aquatic food value chains. Marine Policy, 129 (1) , 104523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104523

- Beyene, L. M., Ferede, T., & Diriba, G. (2020). The economywide impact of the COVID-19 in Ethiopia: Policy and recovery options (Policy Working Paper 03/2020). Ethiopian Economics Association (EEA).

- Bitanihirwe, B. K. Y., & Ssewanyana, D. (2020). The health and economic burden of the coronavirus in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Health Promotion 0 (0) , 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975920977874

- Boretti, A. (2021). COVID-19 lockdown measures as a driver of hunger and undernourishment in Africa. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 16 (1) , 100625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2021.100625

- Boum, Y., Bebell, L. M., & Bisseck, A.-C. Z.-K. (2021). Africa needs local solutions to face the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 397(10281), 1238–1240. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00719-4

- Bukuluki, P., Mwenyango, H., Katongole, S. P., Sidhva, D., & Palattiyil, G. (2020). The socio-economic and psychosocial impact of Covid-19 pandemic on urban refugees in Uganda. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100045

- Buonsenso, D., Cinicola, B., Raffaelli, F., Sollena, P., & Iodice, F. (2020, August). Social consequences of COVID-19 in a low resource setting in Sierra Leone, West Africa. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 97, 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.104

- Casale, D., & Posel, D. (2021). Gender inequality and the COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from a large national survey during South Africa’s lockdown. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 71 (1) , 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100569

- Chitiga-Mabugu, M., Henseler, M., Mabugu, R., & Maisonnave, H. (2020). Economic and distributional impact of COVID-19: Evidence from macro-micro modelling of the South African Economy. South African Journal of Economics, 0( 0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/saje.12275

- Chiwona-Karltun, L., Amuakwa-Mensah, F., Wamala-Larsson, C., Amuakwa-Mensah, S., Abu Hatab, A., Made, N., Taremwa, N. K., Melyoki, L., Rutashobya, L. K., Madonsela, T., Lourens, M., Stone, W., & Bizoza, A. R. (2021, April). COVID-19: From health crises to food security anxiety and policy implications. Ambio, 50(4), 794–811. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01481-y

- Crayne, M. P. (2020). The traumatic impact of job loss and job search in the aftermath of COVID-19. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(1), 180–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000852

- Devereux, S., Bene, C., & Hoddinott, J. (2020, July 14). Conceptualising COVID-19ʹs impacts on household food security. Food Security 12 (1) , 769–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0

- Elliott, R. J. R., Schumacher, I., & Withagen, C. (2020). Suggestions for a Covid-19 post-pandemic research Agenda in environmental economics. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), 187–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00478-1

- Erokhin, V., & Gao, T. (2020, August 10). Impacts of COVID-19 on trade and economic aspects of food security: Evidence from 45 developing countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165775

- FAO. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on agriculture, food systems and rural livelihoods in Eastern Africa: Policy and programmatic options. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Fernando, J. (2020, October 5). How Africa is promoting agricultural innovations and technologies amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Molecular Plant, 13(10), 1345–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.08.003

- Gele, A. (2020). What works where in prevention of Covid-19: The case of Somalia. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 26(5), 495–496. https://doi.org/10.26719/2020.26.5.495

- Gerard, F., Imbert, C., & Orkin, K. (2020). Social protection response to the COVID-19 crisis: Options for developing countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(1), 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa026

- Giese, J., & Haldane, A. (2020). COVID-19 and the financial system: A tale of two crises. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(1), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa035

- Greer, S. L., King, E. J., da Fonseca, E. M., & Peralta-Santos, A. (2020, September). The comparative politics of COVID-19: The need to understand government responses. Global Public Health, 15(9), 1413–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1783340

- Herring, E., Campbell, P., Elmi, M., Ismail, L., Jama, J., McNeill, S., Rubac, A., Ali, A. S., Saeed, A., & Yusuf, M. (2020). COVID-19 and sustainable development in Somalia/Somaliland. Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, 5(1), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/23779497.2020.1824584

- Hirvonen, K. (2020). Economic impacts of COVID-19 pandemic in Ethiopia A review of phone survey evidence. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Hirvonen, K., Minten, B., Mohammed, B., & Tamru, S. (2021). Food prices and marketing margins during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Evidence from vegetable value chains in Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics, 52(3), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12626

- Huss, M., Brander, M., Kassie, M., Ehlert, U., & Bernauer, T. (2021). Improved storage mitigates vulnerability to food-supply shocks in smallholder agriculture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Food Security 28 (1) , 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100468

- ILO. (2020a). COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses (ILO Monitor 1st Edition, Issue. International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (2020b). COVID-19 and the world of work: Updated estimates and analysis (ILO Monitor: Fifth Edition, Issue. International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (2020c). COVID-19 and the world of work: Updated estimates and analysis (ILO Monitor Sixth Edition, Issue. International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (2020d). The effects of COVID‑19 on trade and global supply chains. International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (2020e). ILO monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work. In Updated estimates and analysis (2nd ed.). International Labour Organization 1–11 .

- ILO. (2020f). The impacts from a COVID-19 shock to South Africa’s economy and labour market. International Labour Organization.

- IMF. (2020). Regional economic outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa: COVID-19: An unprecedented threat to development.

- Inegbedion, H. E. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown: Implication for food security. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, ahead-of-print(ahead–of–print 1–15). https://doi.org/10.1108/jadee-06-2020-0130

- Janssens, W., Pradhan, M., de Groot, R., Sidze, E., Donfouet, H. P. P., & Abajobir, A. (2021). The short-term economic effects of COVID-19 on low-income households in rural Kenya: An analysis using weekly financial household data. World Development, 138 (1) , 105280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105280

- Kansiime, M. K., Tambo, J. A., Mugambi, I., Bundi, M., Kara, A., & Owuor, C. (2021). COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development, 137 (1) , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199

- Lawson-Lartego, L., & Cohen, M. J. (2020). 10 recommendations for African governments to ensure food security for poor and vulnerable populations during COVID-19. Food Security, 12(4), 899–902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01062-7

- Lee, S., Schmidt-Klau, D., & Verick, S. (2020). The labour market impacts of the COVID-19: A global perspective. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 63(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00249-y

- Mahmud, M., & Riley, E. (2021). Household response to an extreme shock: Evidence on the immediate impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on economic outcomes and well-being in rural Uganda. World Development, 140 (1) , 105318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105318

- Mohamed, E. M. A., Alhaj Abdallah, S. M., Ahmadi, A., & Lucero-Prisno, D. E. (2021, March 8). Food security and COVID-19 in Africa: Implications and recommendations. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104(5) 1613–1615 . https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1590

- Nchanji, E. B., & Lutomia, C. K. (2021). Regional impact of COVID-19 on the production and food security of common bean smallholder farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implication for SDG’s. Global Food Security, 29(1) 1-10 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100524

- Nchanji, E. B., Lutomia, C. K., Chirwa, R., Templer, N., Rubyogo, J. C., & Onyango, P. (2021). Immediate impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on bean value chain in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Agricultural Systems, 188, (1) 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103034

- Nechifor, V., Ramos, M. P., Ferrari, E., Laichena, J., Kihiu, E., Omanyo, D., Musamali, R., & Kiriga, B. (2021, March). Food security and welfare changes under COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa: Impacts and responses in Kenya. Global Food Security, 28 (1) , 100514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100514

- Odunitan-Wayas, F. A., Alaba, O. A., & Lambert, E. V. (2021). Food insecurity and social injustice: The plight of urban poor African immigrants in South Africa during the COVID-19 crisis. Global Public Health, 16(1), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1854325

- OECD. (2020). Africa’s response to COVID-19: What roles for trade, manufacturing and intellectual property? Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Omobowale, A. O., Oyelade, O. K., Omobowale, M. O., & Falase, O. S. (2020). Contextual reflections on COVID-19 and informal workers in Nigeria. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 40(9/10), 1041–1057. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-05-2020-0150

- Oruonye, E. D., & Ahmed, M. (2020). An appraisal of the potential impacts of Covid-19 on tourism in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Technology Research, 1(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.22158/jetr.v1n1p32

- Osseni, I. A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa: Preparedness, response, and hidden potentials. Tropical Medicine and Health, 48(48), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00240-9

- Ozili. (2020). COVID-19 in Africa: Socio-economic impact, policy response and opportunities. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, ahead-of-print(ahead–of–print 1–24). https://doi.org/10.1108/ijssp-05-2020-0171

- Poudel, P. B., Poudel, M. R., Gautam, A., Phuyal, S., Tiwari, C. K., Bashyal, N., & Bashyal, S. (2020). COVID-19 and its global impact on food and agriculture. Journal of Biology and Today’s World, 9(5), 1–4 doi:10.3390/ijerph17103445.

- Renzaho, A. M. N. (2020). The need for the right socio-economic and cultural fit in the COVID-19 response in Sub-Saharan Africa: Examining demographic, economic political, health, and socio-cultural differentials in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103445

- Schmidt, E., Dorosh, P., & Gilbert, R. (2021). Impacts of COVID‐19 induced income and rice price shocks on household welfare in Papua New Guinea: Household model estimates. Agricultural Economics, 52(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12625

- Teachout, M., & Zipfel, C. (2020). The economic impact of COVID-19 lockdowns in sub-Saharan Africa. International Growth Centre. (Policy brief May 2020, Issue.

- Udmale, P., Pal, I., Szabo, S., Pramanik, M., & Large, A. (2020). Global food security in the context of COVID-19: A scenario-based exploratory analysis. Progress in Disaster Science, 7 (1) , 100120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100120

- UN. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition UN policy brief (Policy Breif, Issue. United Nations.

- UN. (2021). Progress towards the sustainable development goals: Report of the secretary-general.

- Van Hoyweghen, K., Fabry, A., Feyaerts, H., Wade, I., & Maertens, M. (2021, May). Resilience of global and local value chains to the Covid-19 pandemic: Survey evidence from vegetable value chains in Senegal. Agricultural Economics, 52(3), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12627

- WB (2020) Assessing the economic impact of covid-19 and policy responses in sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank.

- Willem, D. (2020). Economic impacts of and policy responses to the coronavirus pandemic: Early evidence from Africa support economic transformation.

- Workie, E., Mackolil, J., Nyika, J., & Ramadas, S. (2020). Deciphering the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security, agriculture, and livelihoods: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 2 (1) , 100014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2020.100014

- Yaya, S., Otu, A., & Labonté, R. (2020). Globalisation in the time of COVID-19: Repositioning Africa to meet the immediate and remote challenges. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00581-4

- Zidouemba, P. R., Kinda, S. R., & Ouedraogo, I. M. (2020). Could Covid-19 Worsen food insecurity in Burkina Faso? The European Journal of Development Research, 32(5), 1379–1401. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00324-6

Appendix

Table A1. Summary of papers included for the systematic review