Abstract

This paper focuses on the IT consultancy sector, an area of strategic importance within the Spanish economy and its mains aim is to analyse the impact that the support perceived by employees has on their organizational commitment and turnover intention.We distributed a questionnaire with a five-point Likert scale among 1000 professionals from various companies in the IT consultancy sector in Spain. The data collected were analysed using the PLS-SEM (partial least squares structural equation modelling) technique with the SmartPLS software. The analysis of the data demonstrates a negative relationship between employees’ perception of organizational support and their turnover intention, i.e., the greater the organizational support received, the lower the intention to leave the company. In companies where employees had a higher degree of organizational commitment, their intention to leave the company decreased to an even greater extent.This study shows that both the organizational support perceived by employees and their organizational commitment are important factors that influence their turnover intention; therefore, organizations need to take these aspects into consideration to reduce staff turnover rates.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

One of the most important factors in making a difference within the current business environment is to have committed, productive, and highly motivated employees who are willing to stay with the company. In Spain, turnover intention had an average incidence of 21% in 2018, rising to 25.6% in the information and communication technologies sector. In this context, the ability of companies to retain key employees becomes mandatory.

In this paper we try to determine how aspects such as between employees’ perception of organizational support and organizational commitment can lower high turnover intention levels in IT consultancy sector, an area of strategic importance within the Spanish economy.

1. Introduction

One of the most important factors in making a difference within the current business environment is to have committed, productive, and highly motivated employees who are willing to stay with the company (Aydogdu & Asikgil, Citation2011), the success of any organisation is largely dependent upon its employees (Rafiq et al., Citation2019).

The long-term success and survival of any organization depends on its ability to retain key employees. To a large extent, aspects such as customer satisfaction, company performance, or the work climate depend on the organization’s ability to retain the best employees (Das & Baruah, Citation2013). A report by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM, Citation2004) indicates that around 75% of employees are actively looking for another job, which is a statistic that should concern employers. Different studies have addressed the importance of the employer brand in attracting talent (Amelia & Nasution, Citation2016; Sokro, Citation2012). However, retention of the best talent does not depend on the brand alone; companies need to consider other aspects, such as those analysed in this paper.

Different aspects such as work–life balance (Abeykoon & Perera, Citation2019), training employees (Sebola et al., Citation2019), or occupational stress (Prasad et al., Citation2020) can influence the well-being of employees and impact their professional performance, degree of organizational commitment and, especially, their turnover intention. In Spain, turnover intention had an average incidence of 21% in 2018, rising to 25.6% in the information and communication technologies sector, with intention to leave resulting from aspects as diverse as lack of professional development, poor working environment, or lack of identification with the company’s objectives (Taudien, Citation2019). Knowledge of these aspects and understanding their capacity to influence employees is key to maintaining staff motivation and retaining the best talent. Talent retention is important in any company, especially in the competitive and dynamic IT consultancy sector whose employees are required to be highly qualified with professional experience that is often difficult to achieve.

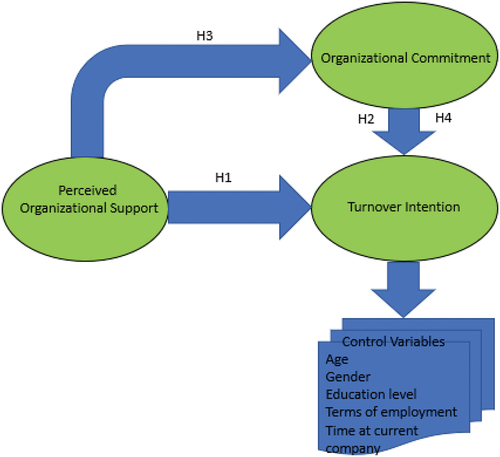

This paper analyses the impact of perceived organizational support on employee turnover intention, how this organizational support also has an impact on organizational commitment and, finally, how this organizational commitment has an even greater impact on the intention to leave the company than that of the direct relationship between organizational support and turnover intention. For this purpose, we used a questionnaire designed to collect data from a group of professionals from some of the main companies in the IT consultancy sector in Spain; the data have been analysed using the PLS-SEM method to determine the validity of our working hypotheses.

Although previous studies have analysed the impact of perceived organizational support on turnover intention (Kalidass & Bahron, Citation2015; Timms et al., Citation2015; Y. Wong & Wong, Citation2017), there appear to be no studies analysing this impact in the IT consultancy sector in Spain; therefore, we believe that this paper can help to fill this gap. It is important at this point to emphasize the high level of qualifications of employees in this sector: more than 66% have achieved university-level qualifications, and according to the Spanish Association of Consulting Companies (Asociación Española de empresas de consultoría, Citation2021), 74% of graduates specialize in STEM areas (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Together with the high level of employment in the sector that we noted earlier, this stresses the need to retain talent.

The paper is structured as follows: first, a brief review of the literature is provided, leading to the development of the proposed conceptual model. Then, the materials and methods are described, followed by a presentation of the results. The paper ends with the conclusions, limitations, implications, and future lines of research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Talent retention in the IT consultancy in Spain: Why is employee turnover a problem?

According to data collected by the Spanish Association of Consultancy Firms (Asociación Española de empresas de consultoría, Citation2021) in its 2020 report, the IT consultancy sector obtained more than 14,500 million euros in revenues that year, which represents more on less 1.15% of the national GDP. In the field of employment, the sector saw its workforce increase by 0.7% compared to the previous year, exceeding 203,500 workers, including 32.3% of women. IT consultancy is therefore a sector of great importance for both the economy and national employment, underlining the need to determine which aspects are likely to improve employee commitment to their companies and help to reduce the high workforce turnover, which is currently around 15% (Expansión, Citation2020).

Some people argue that employee rotation should not pose a problem since new employees tend to have lower costs, and new blood brings new ideas and perspectives (Dibbern et al., Citation2008); however, the reality is different. High employee turnover is one of the main concerns for companies due to the high costs that the training and replacement of qualified staff represent for organizations, both in terms of time and money (Birur & Muthiah, Citation2013). Recent research recognizes the serious effects of high employee turnover on organizational performance (Smite et al., Citation2020), which are especially strongly felt in software companies due to their high dependence on intellectual capital (Smite & Solingen, Citation2016). A study of turnover impact on IT companies in the United Kingdom found that the average lost productivity of replacing an skilled employee was more than US$6,500 (Pontin & Pearson, Citation2015). The economic impact of turnover includes aspects such as the cost of recruitment, knowledge transfer and training costs, travel costs, or costs of mentoring and support, in addition to the operational and behavioural impact (Smite et al., Citation2020) that affects productivity and employee frustrations.

According to data from the National Statistics Institute’s labour force survey of 2018 (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta de Población Activa, Citation2019), the information and communication technologies sector had the highest employment rate (79.88%); therefore, retaining the best talent is a priority and a source of competitive advantage for companies in this sector (Stumpf et al., Citation2010).

Employee turnover is not only a Spanish challenge; it is one of the biggest challenges faced by the global software industry in general (Ebert et al., Citation2008). Hence, achieving continuity in the most experienced and productive staff is a main priority for any organization.

2.2. Main factors involved in staff turnover intention

Previous studies have examined different factors that may affect the intention of employees to leave their companies, including stress (Prasetio et al., Citation2019; Yukongdi & Shrestha, Citation2020), ambiguity in employment position or role assignment (Jones et al., Citation2007), work overload (Jones et al., Citation2007), job satisfaction (Alniacik et al., Citation2011; Cho et al., Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2020; Yamaguchi, Citation2012; Yucel & Bektas, Citation2012), occupational health and safety (Amponsah Tawiak et al., Citation2016; Suárez et al., Citation2021; Sun Jung et al., Citation2021), workplace relationships (Soltis et al., Citation2013), and organizational support (Kalidass & Bahron, Citation2015; Timms et al., Citation2015; Y. Wong & Wong, Citation2017). Although all of these factors are important, this paper focuses on analysing how perceived organizational support influences employees’ organizational commitment and turnover intention. The aim of this study is to fill the gaps in the literature and to increase current knowledge on how perceived organizational support relates to organizational commitment to the company and employee turnover intention in the IT consultancy sector in Spain. The study also examines how companies should approach these aspects in order to reduce the current problem of high employee turnover in this sector at the national level in Spain.

2.3. The relationship between perceived organizational support and employee turnover intention

Staff turnover refers to the process by which an employee leaves his current organization for another (Cho & Son, Citation2011). In this paper, we focus on voluntary turnover, which has a significant negative impact on both the efficiency and productivity of companies, and also incurs significant costs for the organizations affected (Sun & Wang, Citation2017).

As noted above, different factors influence employees when it comes to modifying their intention to leave the company, such as stress, length of service, work overload, job satisfaction, occupational health and safety, and organizational support, among others. One of the most studied factors is the influence of job satisfaction on employee turnover intention (Alniacik et al., Citation2011; Cho et al., Citation2012; Li et al., Citation2020; Yamaguchi, Citation2012; Yucel & Bektas, Citation2012). However, in this paper we have decided to focus on how perceived organizational support is able to influence employee organizational commitment and turnover intention, specifically in Spanish IT consultancy companies.

Perceived organizational support refers to the assurance that the organization’s help will be available when necessary to carry out its work effectively and to cope with difficult situations (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002); it is employees’ perception that the organization cares about their well-being and values their contributions, and is able to consider that the perceived organizational support is capable of influencing the employees’ attitudes and the results of their labour (Alnaimi & Rjoub, Citation2019).

Numerous previous studies have analysed the relationship between perceived organizational support and turnover intention in different professional settings and countries, such as banking, education, and public services in Australia (Timms et al., Citation2015), hospitality in Malaysia and Nigeria (Kalidass & Bahron, Citation2015; Karatepe & Olugbade, Citation2017), and manufacturing in China (Y. Wong & Wong, Citation2017), all of which have found a significant relationship between the two factors. In the study by Kalidass and Bahron (Citation2015), although it was conducted in another professional sector, it reached the same conclusion as that desired for the present study: the existence of a significant negative relationship between perceived organizational support and employee turnover intention. Kalidass and Bahron obtained this conclusion by analysing a statistical model developed based on responses to a questionnaire distributed among professionals in the hotel sector in Malaysia.

We also found that since employees tend to identify their managers with the company, an improvement in employees’ perception of their line manager’s support also improves their perception of the organization’s support; therefore, we can also consider the relationship between supervisor support and employee turnover (Alkhateri et al., Citation2018).

Based on the elements discussed above, we put forward our first working hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1. There is a negative relationship between perceived organizational support and employee turnover intention.

2.4. The mediating role of organizational commitment

Interest in the study of organizational commitment emerged in the 1960s (Cohen, Citation2003). Over time, new approaches to commitment appeared that were more focused on the job and work group than organizational aspects (Morrow, Citation1993; Randall & Cote, Citation1991).

Organizational commitment has been defined in the literature as the extent of an employee’s identification toward his company; the degree to which an employee is satisfied to belong to his or her organization (Ehrhardt et al., Citation2011). Other authors have referred to organizational commitment as the force that binds people to companies (Bentein et al., Citation2005). Organizational commitment, in addition to having a positive effect on the performance of employees, means that committed employees are willing to perform other tasks and put in additional effort (Loan, Citation2020); organizational commitment may have an even greater impact on these behaviours outside their duties than on their own performance.

Different aspects influence employees’ organizational commitment, such as job satisfaction (Aydogdu & Asikgil, Citation2011), culture of ethics in an organization (Farhan, Citation2021), leadership style of managers (Tohidian & Rahimian, Citation2019), occupational health and safety (Amponsah Tawiak et al., Citation2016; Suárez et al., Citation2021; Thirapatsakun et al., Citation2015), or organizational support (Behson, Citation2005; Eisenberger et al., Citation2001; Timms et al., Citation2015).

In this study, we assumed the existence of a mediating relationship of organizational commitment between organizational support and employee turnover intention. Previous studies have explored the mediation of different human resources and organizational policies such as career development opportunities and career supervision (Yamazakia & Petchdee, Citation2015) or adequate compensation (Y. Wong & Wong, Citation2017), as well as the mediation of employees’ organizational commitment to their organization between organizational support and employee turnover intention in different sectors and countries, such as the public sector in Australia (Perryer et al., Citation2010) or the hotel sector in Malaysia (Kalidass & Bahron, Citation2015). Other papers have also analysed the mediation of organizational commitment between different human resources practices and turnover intention (Rageb et al., Citation2013).

Based on the data analysed above, we present our second working hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: Organizational commitment mediates between perceived organizational support and employee turnover intention.

The concept of organizational support is closely related to employees’ perceptions or beliefs about the level at which the organization values their work and contribution to the company and cares for their well-being and professional development (Eisenberger et al., Citation1986). Perceiving adequate organizational support has a positive influence on employees, encouraging them to take care of their company and help it to achieve its goals (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Citation2002). This in turn invites company management to strive to build a healthy work environment, where aspects such as organizational support become more relevant since they can contribute to employee well-being (Berthelsen et al., Citation2008).

Previous studies (Behson, Citation2005; Timms et al., Citation2015) indicate that providing a supportive environment in the company has an impact on increasing employee satisfaction and reducing employee stress levels and turnover intention. A strong perception of the organizational support received would strengthen the affective commitment of workers to the organization (Eisenberger et al., Citation1986). Given the strong relationship between the organizational support perceived by employees and overall job satisfaction (Eisenberger et al., Citation1997), we can speak of a reciprocity on the part of employees who have a greater affective commitment to their company and feel greater support from it (Eisenberger et al., Citation2001). This reciprocity, which serves as a support in the present study, was formulated as a theory by Gouldner (Citation1960) and indicates that, whoever receives a benefit acquires an internal moral precept to repay the giver of this benefit.

Once again, we are faced with a relationship that has been previously studied in different professional sectors (Baird et al., Citation2019; Eisenberger et al., Citation2001). As in the previous hypothesis, we consider that the implementation of adequate organizational support policies will have a positive impact on the work and emotional commitment of workers to their organization, even in activities such as IT consultancy in Spain.

Based on the data analysed above, we put forward our third working hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3. There is a relationship between perceived organizational support and employees’ organizational commitment.

Although the concept of organizational commitment is quite common in academic research (Lyu et al., Citation2017; Tsaur et al., Citation2019), it has been little studied in the field of IT consultancy, although it is possible to find papers that analyse this variable in the IT sector (Kumar et al., Citation2013; Noorman et al., Citation2015).

Since organizational commitment is a motivational construct (Karatepe & Karadas, Citation2015) that involves a positive work-related attitude and is a determinant in predicting employees’ job performance (Christian et al., Citation2011), it is extremely important for organizations to be able to achieve this commitment among their employees. This is especially the case considering the potential for the long-term development and sustainability of organizational commitment (Bakker & Schaufeli, Citation2008), and given that it also impacts the improvement of high-performance work practices and job performance (Karatepe, Citation2013).

We can therefore affirm that working on maintaining and improving organizational commitment is of vital importance for organizations, especially given that organizational commitment together with job satisfaction plays a very important role in employee turnover intention (LeRouge et al., Citation2006).

It is also important to consider job satisfaction, since this aspect, together with employees’ organizational commitment, is a key predictor of turnover (Ullrich & Fitzgerald, Citation1990); therefore, we consider it important to try to find out which factors influence these aspects in a negative way.

Although this relationship has been previously studied by different authors (Mathieu et al., Citation2016; Neves et al., Citation2022; C. Wong & Spence, Citation2015; Yousaf et al., Citation2015), we will focus on analysing its magnitude in the field of IT consultancy in Spain.

Based on the data analysed above, we propose our fourth working hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: There is a negative relationship between employees’ organizational commitment and their turnover intention.

3. Materials and methods

In this study, we distributed a research questionnaire consisting of 19 questions with a five-point Likert scale ranging among 1000 full-time professionals who are working in different Spanish companies in the IT consultancy sector during end of 2020. Participants were from all Departments and levels from developers to managers. All the employees received an introductory e-mail explained the scholarly purpose of the research with the research questionnaire.

A total of 458 responses were received, and after being analysed and refined 273 complete responses were selected. The reasons that led us to discard 185 questionnaires were mainly two: incomplete questionnaires and illogical answers (all 1, all 5 …).

The questions used for this study were validated in previous research studies (Bothma & Roodt, Citation2013; Eisenberger et al., Citation1997; Radic et al., Citation2020) and adapted to the needs of our study. Of the 19 questions in the questionnaire, five correspond to the socio-demographic characteristics (control variables) of the participants, while the other 14 are grouped into three different constructs used in the statistical analysis: perceived organizational support (Eisenberger et al., Citation1997; Holton, Citation1996), organizational commitment (Radic et al., Citation2020), and turnover intention (Bothma & Roodt, Citation2013).

The first stage of the analysis consisted of analysing the different socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

The quantitative model used for the study was validated with the PLS-SEM method using the SmartPLS 3 software (Sarstedt et al., Citation2017).

PLS-SEM is one of the techniques that make use of structural equation modelling (SEM), which is a technique for second-generation multivariate data analysis. SEM provides investigations with a high level of confidence due to its statistical efficiency, which is achieved by using specialized software such as SmartPLS, VisualPLS, or the different packages available for R. This software allows the simultaneous examination of the relationships between several dependent and independent variables, and is widely used in social science research, among other fields (Haenlein & Kaplan, Citation2004).

The use of SEM has increased significantly in recent years in a wide variety of disciplines, including human resources management (Shook et al., Citation2003). SEM methods are an evolution of traditional linear modelling procedures and are used to assess whether the analysed model is consistent with the data collected to validate the theory (Lei & Wu, Citation2007). SEM is a multivariate analytical method used to estimate complex relationships between several variables even when these relationships are not directly observable (Williams et al., Citation2009). The PLS-SEM technique is suitable for use in both exploratory and confirmatory analyses (Hair et al., Citation2014).

An analysis of a measurement model requires examination of the validity and reliability of the latent variables through their relationship with their associated measures. In this study, this analysis was performed through an assessment of the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the individual and construct variables. Once the reliability and validity of the measured model was established, the structural model was evaluated through an analysis of the relationships between the different constructs defined in the study hypotheses.

The following sections of this paper present the results obtained through the evaluation of the structural model.

4. Results

The PLS-SEM technique was used to analyse the model because it is the most suitable technique for this type of study due to its high predictive capability (J. F. Hair et al., Citation2019; Sharma et al., Citation2019). This method is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines, and is currently the most developed among variance-based systems for SEM. The analysis was performed using a two-step approach: evaluation of the measurement model and evaluation of the structural model.

Analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample showed that the largest group of the professionals surveyed (31.87%) are aged between 30 and 39 years old, with the second largest group being between 40 and 49 years old (29.30%), 22.37% of the professionals aged 18 to 29 years, and 16.48% aged 50 to 59 years. Regarding gender, there are more men than women (58.98% men compared to 41.02% women). Turning to the level of education, 74.72% of those surveyed are educated up to university studies, 33.33% have postgraduate studies, 23.07% have secondary studies, while only 2.2% have only primary studies. The vast majority of the employees who responded to the survey (87.19%) have a permanent contract compared to 12.82% with a temporary contract. In terms of length of service in their current company, the majority of respondents (54.95%) have been with their current company for less than 5 years, 19.41% for between 5 and 10 years, 11.36% for between 11 and 15 years, and only 10.26% of respondents have been in their current company for more than 15 years, which confirms our premise of the high employee turnover in the context of the IT consultancy sector in Spain.

4.1. Measurement model

Given the complexity of the model to be evaluated and the reliability and predictive strength that this method provides, we decided to use PLS-SEM through the SmartPLS software (Urbach & Ahlemann, Citation2010).

In order to evaluate the model, different factors of the model were validated, such as the significance level of 95%, the internal consistency, which was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, and the composite reliability. The convergent validity of the model was assessed through obtaining the indicator reliability and the average variance extracted (AVE). To assess the discriminant validity of the model, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was used. Cross-loadings between indicators and latent variables were also assessed. In validating the internal consistency of the model, we found that all the variables reached an adequate Cronbach’s alpha value (Hair et al., Citation2013) and that the composite reliability (CR) values are adequate, reaching values ranging from 0.842 to 0.941 (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). The results can be seen in Table .

Table 1. Factor loadings, means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and average variance extracted

Convergent validity is used to check that a set of indicators represents a single construct (Henseler et al., Citation2009). It was validated in our model through AVE, which must be equal to or greater than 0.50; this value is shown in Table , indicating that our model also meets this requirement.

Another aspect to consider is that of discriminant validity, which indicates to what extent a construct differs from the others. This is measured mainly by the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which considers the amount of variance that a construct captures from its indicators (AVE) and whose value must be greater than the variance that the construct shares with the other constructs in the model. Table shows how the observed values for our model meet this requirement.

Table 2. Discriminant validity—Fornell-Larcker criterion

It must also be validated that the value of the cross-loadings is higher for the variable itself than for the other variables evaluated in the model (Barclay et al., Citation1995). Table shows that the model analysed also complies with this assumption.

Table also shows the loading factors of the different variables, together with their mean values and standard deviation: the loading factors of all the variables have adequate values, which reaffirms the validity of the proposed model.

4.2. Structural model

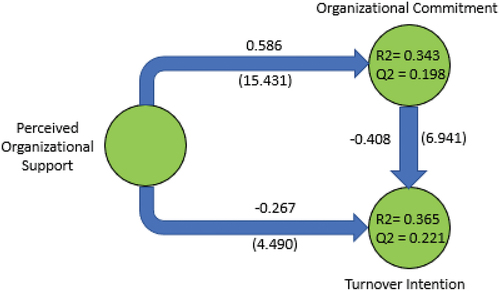

In this study, we used the structural equation model shown in to simultaneously assess the magnitude of the relationships between the different constructs in the model.

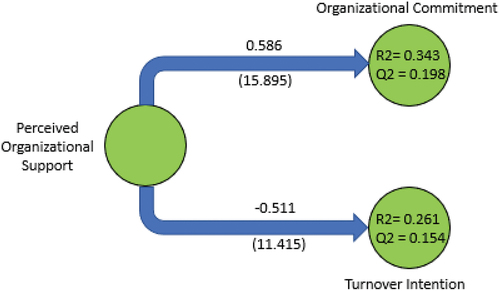

The analysis results show that perceived organizational support has a positive influence on organizational commitment (0.586) as well as a negative impact on employee turnover intention (−0.267). Moreover, organizational commitment has a significant negative relationship with employee turnover intention (−0.408).

4.3. Analysis of mediation

We can confirm the existence of mediation when a variable which acts as a mediator (in this study, Organizational Commitment) is capable of modifying the influence of a preceding or independent variable (Perceived Organizational Support in our model) on a dependent or predecessor variable (Turnover Intention in our case), significantly modifying the magnitude of the relationship between these two variables (Mathieu & Taylor, Citation2006).

When the inclusion of the construct that acts as a mediator modifies the magnitude of the initial relationship between the dependent and independent variables, but the relationship remains significant, the mediation is considered partial (Henseler et al., Citation2009), with the mediation being complementary when the two point in the same direction (Sarstedt et al., Citation2017). In our model, inclusion of the variable organizational commitment between the variables organizational support and turnover intention reduced the strength of the direct relationship between these two variables from −0.511 to −0.267 (Figures ) while maintaining the same sign, indicating that we are dealing with partial mediation of a complementary nature.

To determine the size of the total indirect effect, we reviewed the value of the variance accounted for (VAF; Hair et al., Citation2014). This calculates the indirect effect of the mediation, which is 0.472 for our model, so we can confirm a partial mediation with a magnitude of 0.472.

In addition, and to complement the validation of the models, the Stone-Geisser predictive relevance (Q2) was calculated, whose results (all positive) indicate that the models have predictive capacity for the estimation of values (Figures ).

The mediation model was evaluated using the bootstrapping method (Hayes et al., Citation2011), which is a non-parametric procedure valid for both single and multiple mediation analysis, and for small sample sizes, and therefore considered suitable for the PLS-SEM method (Hair et al., Citation2014). Some of the aspects to be evaluated, valid for both direct and indirect effects, are the magnitude of these effects, their confidence interval, the t-value, and the significance based on the p-value (Sarstedt et al., Citation2017); the analysis result are provided in Table .

Table 3. Direct and indirect effects

The results of the analysed data prove the existence of a significant complementary partial mediation between these constructs, which supports our working hypothesis.

5. Discussion

The results obtained from the statistical model analysis show that the organizational support construct has a direct positive influence on the organizational commitment construct (Hypothesis 1) and, at the same time, a negative influence on employee turnover intention (Hypothesis 3).

In addition, the organizational commitment construct has a direct and negative impact on employee turnover intention (Hypothesis 4). Organizational commitment significantly mediates, although partially, between perceived organizational support and employee turnover intention (Hypothesis 2).

Therefore, and based on the above, all our research hypotheses have been verified.

These results confirm our theory that in the IT consultancy sector in Spain, organizational support is a factor of great importance in employee turnover intention, a result in line with that observed in previous studies in different professional sectors around the world (Kalidass & Bahron, Citation2015; Timms et al., Citation2015; Y. Wong & Wong, Citation2017). This highlights the importance for companies in the sector to improve this aspect in their organizations.

This finding is in line with our expectations: workers who feel supported and backed by their organization will develop a stronger emotional commitment to it, will be more loyal to it, and will be more reluctant to look for another job or leave the company. These data also serve to corroborate the first research hypothesis of our study: the existence of a negative relationship between perceived organizational support and employee turnover intention.

We can also observe how perceived organizational support has a positive impact on employees’ organizational commitment, which is also in agreement with previous research studies (Behson, Citation2005; Eisenberger et al., Citation2001; Timms et al., Citation2015). These data support our second research hypothesis: the existence of a positive relationship between perceived organizational support and employees’ organizational commitment. As with the previous hypothesis, this finding is also to be expected: if employees feel that their company supports them, they will be more committed to both their work and their organization.

There is a negative relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention, implying that employees who are highly committed to their work and their company are more reluctant to leave, which is in agreement with previous studies (C. Wong & Spence, Citation2015; Yousaf et al., Citation2015). This supports our third research hypothesis: the existence of a negative relationship between employees’ organizational commitment and their intention to leave the company. While this last aspect was also expected, the inclusion of a mediating effect indicates that employees who feel satisfied with their company’s organizational support are likely to be more committed to the company and, consequently, have lower levels of turnover intention. Therefore, this evidences that organizational commitment mediates between organizational support and employee turnover intention.

6. Conclusions, limitations, and future lines of research

According to the data analysed in this paper, we can confirm that employees who perceive adequate organizational support in their company tend to have a higher degree of commitment to both their organization and their job, thus decreasing their turnover intention. Conversely, employees who are dissatisfied with the support from the company tend to have a lower degree of commitment to the organization and the job, thereby increasing their interest in looking for another job and leaving the company.

Although this impact has been discussed previously in different areas, but no studies appear to have analysed the impact of these factors in the Spanish IT consultancy sector. Thus, we contend that this study can fill this gap and help organizations to implement appropriate policies to minimize the impact of high employee turnover rates in the sector.

Based on this study, and considering both the high level of employee turnover in the Spanish IT sector and its strategic importance, both from an economic point of view and in terms of job creation, there is a clear need for the management of these companies to strengthen and encourage organizational support for employees. Not only is it important to implement and improve organizational support policies in order to enhance the organizational commitment of employees and reduce their turnover rate, but companies must also work on making employees aware of these policies. On the other hand, it is important to make managers aware of the importance of providing adequate support to their employees in order for companies to retain the best talent.

Although we have managed to test the selected working hypotheses in this study, it is limited to the impact of perceived organizational support at work, without addressing the possible impact of other aspects on organizational commitment and employee turnover intention. From a practical point of view, this study demonstrates that improving and make visible employees’ support helps organizations to improve their organizational commitment and decrease employee turnover intention, Therefore, these actions should be a priority not only in Spanish IT consulting companies, but also in any organization that wants to retain the best talent and reduce the impact of employee turnover.

An important aspect to consider is that, although turnover volume is important the quality of the workers who leave the company is of even greater importance; therefore, it is necessary to monitor the mood of employees and focus in particular on retaining the best employees (Smite et al., Citation2020) by providing them with greater motivation.

Further research will explore the impact of other factors such as health and safety in the workplace, independence, job satisfaction, stress, or emotional intelligence on the well-being of employees and their turnover intention (Liu & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2012; Lu et al., Citation2016; Shore & Martin, Citation1989). This will thus achieve a broader analysis that includes different work factors and helps in gaining a broader understanding of the relationships between these factors.

Author Contributions

This paper is the result of teamwork. The study was conceived of and designed by the authors. The authors contributed equally to writing the paper and integrating and organizing the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julio Suárez-Albanchez

The authors are part of the department of business administration of the Castilla la Mancha University, in Spain. Among other aspects, they are working on a series of papers focused on the different aspects capable of influencing well-being and turnover intention of employees in IT consultancy sector in Spain.

References

- Abeykoon, A., & Perera, A. (2019). Impact of work life balance on employee job satisfaction of executive level employees. Management Issues, 4(1), 55–18.

- Alkhateri, A., Abuelhassan, A., Khalifa, G., Nusari, M., & Ameen, A. (2018). The Impact of perceived supervisor support on employees turnover intention: The Mediating role of job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. International Business Management, 12(7), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-03-2019-0076

- Alnaimi, A., & Rjoub, H. (2019). Perceived organizational support, psychological entitlement and extrarole behavior: The mediating role of knowledge hiding behavior. Journal of Management & Organization, 27 (3) , 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2019.1

- Alniacik, U., Cigerim, E., Akein, K., & Bayram, O. (2011). Independent and joint effects of perceived corporate reputation, affective commitment and job satisfaction on turnover intentions. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1177–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.139

- Amelia, N., & Nasution, R. A. (2016). Employer branding for talent attraction in the Indonesian mining industry. International Journal of Business, 21(3), 226–242.

- Amponsah Tawiak, K., Ntow, M. A., & Mensah, J. (2016). Occupational health and safety management and turnover intention in the Ghanaian mining sector. Safety and Health at Work, 7(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2015.08.002

- Asociación Española de empresas de consultoría. (2021). 2020, la consultoría española. El sector en cifras. AEEC.

- Aydogdu, S., & Asikgil, B. (2011). An empirical study of the relationship among job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention. International Review of Management and Marketing, 1(3), 43–53.

- Baird, K., Tung, A., & Yu, Y. (2019). Employee organizational commitment and hospital performance. Health Care Management Review, 44(3), 206–215. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000181

- Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). Positive organizational behavior: Engaged employees in flourishing organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.515

- Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2), 285–309.

- Behson, S. (2005). The relative contribution of formal and informal organizational work–family support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(3), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.004

- Bentein, K., Vandenberg, R. J., Vandenberghe, C., & Stinglhamber, F. (2005). The role of change in the relationship between commitment and turnover: A latent growth modeling approach. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 468–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.468

- Berthelsen, H., Hjalmers, K., & Soderfeldt, B. (2008). Perceived social support in relation to work among Danish general dental practitioners in private practices. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 116(2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00514.x

- Birur, S., & Muthiah, K. (2013). Turnover intentions among repatriated employees in an emerging economy: The Indian experience. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(19), 3667–3680. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.778318

- Bothma, C., & Roodt, G. (2013). The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v11i1.507

- Cho, Y. N., Rutherford, B. N., & Park, J. K. (2012). Emotional labor’s impact in a retail environment. Journal of Business Research, 66(11), 2338–2345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.04.015

- Cho, D., & Son, J. (2011). Job embeddedness and turnover intentions: An empirical investigation of construction IT industries. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 40, 101–110.

- Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

- Cohen, A. (2003). Multiple commitments in the workplace: An integrative approach. Erlbaum.

- Das, B. L., & Baruah, M. (2013). Employee retention: A review of literature. Journal of Business and Management, 14(2), 8–16.

- Dibbern, J., Winkler, J., & Heinzl, A. (2008). Explaining variations in client extra costs between software projects offshored to India. MIS Quarterly, 32(2), 333–366. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148843

- Ebert, C., Murthy, B., & Jha, N. (2008). Managing risks in global software engineering: Principles and practices. 2008 IEEE International Conference on Global Software Engineering, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICGSE.2008.12

- Ehrhardt, K., Miller, J. S., Freeman, S. J., & Hom, P. W. (2011). An examination of the relationship between training comprehensiveness and organizational commitment: Further exploration of training perceptions and employee attitudes. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(4), 459–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.20086

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.42

- Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 812–820. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.5.812

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

- Expansión. (2020). Available online: https://www.expansion.com/especiales/empleo/consultoria/index.html (accessed on 08-02-2021)

- Farhan, B. Y. (2021). Customizing leadership practices for the millennial workforce: A conceptual framework. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1930865. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1930865

- Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminaty statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

- Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2004). A beginner’s guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3(4), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328031us0304_4

- Hair, J., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11–2018-0203

- Hayes, A. F., Preacher, K. J., & Myers, T. A. (2011). . In & (Eds.), The sourcebook for political communication research: methods, measures and analytical techniques 23 (1) 434–465 . .

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

- Holton, E. (1996). The flawed four‐level evaluation model. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 7(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.3920070103

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Encuesta de Población Activa (2019). Variables de submuestra Año 2018. INE. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/epa_2018_s.pdf ( accessed on 24-04-2021)

- Jones, E., Chonko, L. B., Rangarajan, D., & Roberts, J. A. (2007). The role of overload on job attitudes, turnover intentions, and salesperson performance. Journal of Business Research, 60(7), 663–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.02.014

- Kalidass, A., & Bahron, A. (2015). The relationship between perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and employee turnover intention. International Journal of Business Administration, 6(5), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijba.v6n5p82

- Karatepe, O. (2013). High-performance work practices and hotel employee performance: The mediation of work engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.05.003

- Karatepe, O., & Karadas, G. (2015). Do psychological capital and work engagement foster frontline employees’ satisfaction? A study in the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Manager, 27(6), 1254–1278. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2014-0028

- Karatepe, O., & Olugbade, O. (2017). The effects of work social support and career adaptability on career satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.12

- Kumar, R., Lal, R., & Bansal, Y. (2013). Technostress in relation to job satisfaction and organisational commitment among IT professionals. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 3(12), 1–3.

- Lei, P., & Wu, Q. (2007). Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 26(3), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2007.00099.x

- LeRouge, C., Nelson, A., & Blanton, J. E. (2006). The impact of role stress fit and self-esteem on the job attitudes of IT professionals. Information and Management, 43(8), 928–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2006.08.011

- Li, C. J., Chang, K. K., & Ou, S. M. (2020). The relationship between hotel staff’s organizational justice perception, relationship quality and job performance. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1739953. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1739953

- Liu, S., & Onwuegbuzie, A. (2012). Chinese teachers’ work stress and their turnover intention. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.006

- Loan, L. (2020). The influence of organizational commitment on employees’ job performance: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Management Science Letters, 10(14), 3307–3312. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.007

- Lu, L., Lu, A., Gursoy, D., & Neale, N. (2016). Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(4), 737–761. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2014-0360

- Lyu, J., Hu, L., Hung, K., & Mao, Z. (2017). Assessing servicescape of cruise tourism: The perception of Chinese tourists. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(10), 2556–2572. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2016-0216

- Mathieu, C., Fabi, B., Lacoursière, R., & Raymond, L. (2016). The role of supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment on employee turnover. Journal of Management & Organization, 22(1), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2015.25

- Mathieu, J., & Taylor, S. (2006). Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1031–1056. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.406

- Morrow, P. (1993). The theory and measurement of work commitment. Jai Press Inc.

- Neves, T., Parreira, P., Rodrigues, V., & Graveto, J. (2022). Organizational commitment and intention to leave of nurses in Portuguese Hospitals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19042470

- Noorman, M., Akmal, M., Ibrahim, Z., & Nazri, A. (2015). Malaysian computer professional: Assessment of emotional intelligence and organizational commitment. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 172, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.360

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Perryer, C., Jordan, C., Firns, I., & Travaglione, A. (2010). Predicting turnover intentions: The interactive effects of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. Management Research Review, 33(9), 911–923. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171011070323

- Pontin, G., & Pearson, G. (2015). The retention gap: What it is and how to tackle it. Association for Consultancy and Engineering and EngTechNow.

- Prasad, K. D. V., Vaidya, R. W., & Mangipudi, M. R. (2020). Effect of occupational stress and remote working on psychological well-being of employees: An empirical analysis during covid-19 pandemic concerning information technology industry in Hyderabad. Indian Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, 11(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.18843/ijcms/v11i2/01

- Prasetio, P., Partono, A., Wulansari, P., Putri, S., Ramdhani, R., & Abdullah, A. (2019). The mediation of job satisfaction in the relation of work stress and turnover intention in hotel industry. In 1st international conference on economics, business, entrepreneurship, and finance (ICEBEF 2018), 608–612. Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/icebef-18.2019.130

- Radic, A., Arjona-Fuentes, J., Ariza-Montes, A., Han, H., & Law, R. (2020). Job demands–job resources (JD-R) model, work engagement, and well-being of cruise ship employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102518

- Rafiq, M., Wu, W., Chin, T., & Nasir, M. (2019). The psychological mechanism linking employee work engagement and turnover intention: A moderated mediation study. Work, 62(4), 615–628. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-192894

- Rageb, M., Abd-El-Salam, E., El-Samadicy, A., & Farid, S. (2013). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and job performance as a mediator between role stressors and turnover intentions a study from an Egyptian cultural perspective. International Journal of Business and Economic Development, 1(1), 34–54.

- Randall, D., & Cote, J. (1991). Interrelationships of work commitment constructs. Work and Occupations, 18(2), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888491018002004

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C., & Hair, J. (2017). . In Handbook of market research 26 (1) 1–40 . .

- Sebola, I. C., Roberson, J. R., & Vibetti, S. P. (2019). Attitudes of institutional catering employees in Gauteng towards training programs. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1681925. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1681925

- Sharma, P. N., Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N., & Ray, S. (2019). Prediction-oriented model selection in partial least squares path modeling. Decision Sciences, 52(3), 567–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12329

- Shook, C., Ketchen, D., Cycyota, C., & Crockett, D. (2003). Data analytic trends in strategic management research. Strategic Management Journal, 24(12), 1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.352

- Shore, L., & Martin, H. (1989). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment in relation to work, performance and turnover intentions. Human Relations, 42(7), 625–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678904200705

- SHRM. (2004). New survey finds 75% of employees looking for new jobs ‘It’s all about the money’. PR Newswire.

- Smite, D., & Solingen, R. (2016). What’s the true hourly cost of offshoring? IEEE Software, 33(5), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2015.82

- Smite, D., Solingen, R., & Chatzipetrou, P. (2020). The offshoring elephant in the room: Turnover. IEEE Software, 37(3), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2018.2886179

- Sokro, E. (2012). Impact of employer branding on employee attraction and retention. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(18), 164–173.

- Soltis, S., Agneessens, F., Sasovova, Z., & Labianca, G. (2013). A social network perspective on turnover intentions: The role of distributive justice and social support. Human Resource Management, 52(4), 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21542

- Stumpf, S., Doh, J., & Tymon, W. (2010). The strength of HR practices in India and their effects on employee career success, performance, and potential. Human Resource Management, 49(3), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20361

- Suárez, J., Blazquez, J., Gutierrez, S., & Jimenez, P. (2021). Occupational health and safety, organisational commitment, and turnover intention in the Spanish IT consultancy sector. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115658

- Sun Jung, H., Sik Jung, Y., & Hyun Yoon, H. (2021). COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intention of the luxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92 102703 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703

- Sun, R., & Wang, W. (2017). Transformational leadership, employee turnover intention, and actual voluntary turnover in public organizations. Public Management Review, 19(8), 1124–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1257063

- Taudien, S. (2019). La rotación laboral en España: Causas, datos e inconvenientes para las empresas. RRHHDigital. Available online http://www.rrhhdigital.com/secciones/mercado-laboral/135288/La-rotacion-laboral-en-Espana-causas-datos-e-inconvenientes-para-las-empresas?target=_self ( accessed on 24-04-2021)

- Thirapatsakun, T., Kuntonbutr, C., & Mechida, P. (2015). The relationships among four factors and turnover intentions at different levels of perceived organizational support. Journal of US-China Public Administration, 12(2), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.17265/1548-6591

- Timms, C., Brough, P., O’Driscoll, M., Kalliath, T., Ling Siu, O., Sit, C., & Lo, D. (2015). Flexible work arrangements, work engagement, turnover intentions and psychological health. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 53(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12030

- Tohidian, I., & Rahimian, H. (2019). Reflection on working culture in public organizations: The case of three Iranian Higher Education Institutions. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1630932. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1630932

- Tsaur, S.-H., Hsu, F.-S., & Lin, H. (2019). Workplace fun and work engagement in tourism and hospitality: The role of psychological capital. International Journal of Hospitality Manager, 81, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.016

- Ullrich, A., & Fitzgerald, P. (1990). Stress experienced by physicians and nurses in the cancer ward. Social Science & Medicine, 31(9), 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90113-7

- Urbach, N., & Ahlemann, F. (2010). Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 11(2), 5–40.

- Williams, L., Vandenberg, R., & Edwards, J. (2009). Structural equation modeling in management research: A guide for improved analysis. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 543–604. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903065683

- Wong, C., & Spence, H. (2015). The influence of frontline manager job strain on burnout, commitment and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(12), 1824–1833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.09.006

- Wong, Y., & Wong, Y. (2017). The effects of perceived organisational support and affective commitment on turnover intention: A test of two competing models. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 8(1), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHRM-01-2017-0001

- Yamaguchi, I. (2012). A Japan–US cross-cultural study of relationships among team autonomy, organizational social capital, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.016

- Yamazakia, Y., & Petchdee, S. (2015). Turnover intention, organizational commitment, and specific job satisfaction among production employees in Thailand. Journal of Business and Management, 4(4), 22–38.

- Yousaf, A., Sanders, K., & Abbas, Q. (2015). Organizational/occupational commitment and organizational/occupational turnover intentions: A happy marriage? Personnel Review, 44(4), 470–491. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2012-0203

- Yucel, I., & Bektas, C. (2012). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment and demographic characteristics among teachers in Turkey: Younger is better? Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1598–1608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.346

- Yukongdi, V., & Shrestha, P. (2020). The influence of affective commitment, job satisfaction and job stress on turnover intention: A study of Nepalese bank employees. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 9, 88–98.

Appendix A

Table A1. Research questionnaire