Abstract

The paper aims to identify the narrative communicative resources and messages spread by brands within the background of a global pandemic. This study compares two samples of advertising spots broadcast in Spain: one during the COVID-19 lockdown period and the other selected from the last de-escalation phase of the health crisis. A content analysis of a compendium of 125 commercials was proposed. The main finding is the social function adopted during lockdown in order to encourage the population with positive and resilient messages while during the de-escalation the brands recover their traditional commercial role and, do not even reflect reality with the persistence of the outbreak in the images and discourse. In fact, it showed a first phase focused on branding and a second phase when the population was urged to consume. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown a clear need for brands to adapt to an environment that has dramatically changed overnight. Practical Implications The paper includes implications for brands for sharing common support for emotional and psychological well-being in health crisis. This social function could improve their reputation and positioning globally.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The outbreak of COVID-19 has led to radical change even in social sphere. This study focuses on brand’s communication through advertising spots broadcast in Spain. Two periods are taken in account: the lockdown and the de-escalation phase of the health crisis. On the basis of the analysis of creative axis, communicative resources and messages of 125 spots, the social function adopted by brands is highlighted, especially during lockdown when commercial goals took a back seat and positive and resilient messages took precedence. By contrast, during the de-escalation the brands recover their traditional commercial role and, do not reflect reality with the persistence of the outbreak in the images and discourse. The common aim for brands was urged to consume. The results evidence that brands have adapted their communication to this unprecedent pandemic quickly and they focus their efforts assuming the effects on their reputation.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had dramatic consequences, not only in terms of health but also in economic, social, political and employment terms (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., Citation2021; De Las Heras-Pedrosa et al., Citation2020; Ripon et al., Citation2020). All countries have made great efforts to try to curb the spread of the virus and all that this global crisis means. However, Spain is one of the countries most affected by the virus, given the number of cases and deaths recorded, specifically 3,317,948 cases and 75,911 deaths (World Health Organization, Citation2021). Spain is also relatively dependent on the service sector and the significant weight of the tourism sector in its overall economic activity (OECD, Citation2020). The impact of the COVID pandemic is still unknown, but it undoubtedly represents the country’s greatest historical recession. The Gross Domestic Product variation rate suffered a 0.4% drop and the unemployment figure has grown by 16%, the latter indicator doubling the European average figure according to data from the end of 2020 (Eurostat, Citation2021).

In the case of Spain, the Government declared a state of alarm that implied the lockdown of the population from March 14th until 21 June 2020 (including gradual de-escalation). This decision also led to the paralysis of certain economic sectors such as tourism, hotels and commerce. New waves and peaks of contagion have followed one after the other and continue to spread to the present day, but on 21 June 2020 entry into the so-called “new normal” in Spain was announced. This first phase of de-escalation lasted from June 21st to 25 October 2020 the date on which the Government declared a new state of alarm, but relaxing the measures and restrictions for Spanish citizens.

Although the pandemic has aroused the interest of the scientific community from different perspectives, there is little research focused on commercial communication in audiovisual format. This paper analyzes how brands have faced the pandemic through their creativity, comparing the period of strictest lockdown and the de-escalation phase immediately after. The objective is to discover the role of brands in the crisis and their contribution to the containment and awareness of the disease through their dialogues, images and other resources and, therefore, their possible support for the psychological health of citizens and the transition to the “new normality”.

The current health crisis has demonstrated that communication is the central nervous system of our society (Fernández Beltrán, Citation2020). Previous literature had already highlighted the importance of communication in times of crisis for its ability to provide information that can prevent illness, injury and even death (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., Citation2020; Reynolds & W. Seeger, Citation2005; Shoenberger et al., Citation2021; Verlegh et al., Citation2021).

During the pandemic the Spanish population has consumed a lot of television, motivated by the search for information related to COVID-19 and for entertainment due to spending more time at home. As a result, television consumption in Spain reached historical records in April 2020, with 302 minutes per person/day and in March of the same year, 284 minutes per person/day (Barlovento Comunicación, Citation2020a). With the new normal, this television consumption has been reduced. In September 2020, 235 minutes per person/day were consumed (Barlovento Comunicación, Citation2020b), 67 minutes less than in April and 49 minutes less than in March. The greater exposure to television brings with it a greater probability of contact with the audiovisual advertising broadcast and, therefore, it is interesting to analyze the role of brands in this scenario of radical change in every sense.

An example of the change in the behavior of brands in terms of advertising can be found in the volume of campaigns carried out. While in lockdown they decrease significantly and are even almost non-existent for some sectors of activity, such as perfumes. At the beginning of June 2020 there is an increase of 15% (Somos Marketing, Citation2020), coinciding with the onset of summer, as well as the relaxation of the restrictions applied due to the health crisis.

He and Harris (Citation2020), affirm that during lockdown many companies were proactively involved in diverse Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities. However, there must be consistency between CSR activities and social advertising, because if the opposite occurs, consumers may question the actions of the company (Pabón Montealegre et al., Citation2013). In line with the above, Timothy Coombs and Jean Holladay (Citation2014) suggest that the real challenge for an organization is not established by the magnitude of the crisis, but by the type of response it causes in audiences. Specifically, Xifra (Citation2020) states that during the pandemic, any objective linked to sales takes a back seat and priority is given to demonstrating that brands can offer solutions to the problems directly or indirectly caused by COVID-19.

Coronavirus launches new challenges and demands an adaptation in discourses and creative resources in advertising (Taylor, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Vorhaus, Citation2020). At that time, unprecedented by the measures of social isolation, it radically changes the concerns of citizens, as well as their daily lives (Kantar, Citation2020) and, consequently, brands also change their advertising strategies and messages. In fact, the work of Olivares-Delgado et al. (Citation2020), focused only on the lockdown phase, shows that the health crisis in Spain has enhanced the social function of advertising by brands, even acting as resilience guardians and stress deterrents.

The “new normal” is an opportunity that companies can take advantage of to continue to maintain the social advertising they developed during lockdown, but there is hardly any field work leaning in this direction. In this case, appealing more than ever to individual responsibility and showing the different preventive measures in their advertisements. Especially when new outbreaks and the inability to completely curb the pandemic continue to be common elements at the international level. On the one hand, alluding to works such as Holbrook’s (Citation1987) on the ability of advertising to reflect everyday life, making it possible to maintain certain practices, advertisements through their messages and images could directly and indirectly reinforce supportive behaviour and practices to reverse the disease. On the other hand, the development of the health crisis has increased public demand on brands regarding their involvement, commitment and contribution to the problems (Kantar, Citation2020; UTECA, Citation2020) and it remains to be resolved whether this demand is also met in the advertising field, or is framed only within the Social Responsibility actions developed by brands (Schaefer et al., Citation2020).

This paper is divided into four sections, after this introduction, the methodology is explained. It has been carried out through a content analysis of 125 spots divided within two specific periods: the total number of spots broadcast in Spain during lockdown (71) and a random selection by quotas of 54 spots covering all the activity sectors of the de-escalation phase started on 21 June 2020. All this audiovisual content allows us to ascertain the role of brands in an unprecedented crisis. Thirdly, the most important results of the research are presented. The paper concludes by offering a reflection based on the Spanish case study with practical implications especially relevant for official crisis communication managers and advertisers. The main contribution of the paper is the contrast of the creative strategy more oriented towards branding and reputation, opting for positive and resilient messages during lockdown and then returning to the more commercial orientation of the messages that urge consumption and that no longer have the pandemic as a central axis, not even in the imagery, showing the new reality by displaying, for example, masks, social distance, etc.

Based on the above, the following research questions are posed

RQ1. How does brand advertising communication support prevention, containment and coping with the health crisis?

RQ2. Are resources, imagery and discourses included in the creative strategy of brand advertising during the containment and de-escalation phase to reflect the reality and challenges of the pandemic?

RQ3. What type of advertising characterizes these two relevant moments of the COVID-19 health crisis?

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials and methods

Content analysis was used as an analysis technique. According to Krippendorff (Citation2004), it cannot be considered as strictly qualitative because part of the variables have been coded with quantitative measures (message tone, resilience, etc.); it would be a mixed method. This option makes it possible to understand the content and dynamics within particular contexts (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007) and has made it possible to analyze correlations between key variables such as the type of advertising and the projected level of resilience, as well as to detect common patterns in the creative strategies adopted by brands. In short, the combination allows us to obtain a better understanding of the connections and weights between the main aspects to be evaluated and to provide a new holistic vision with respect to the existing literature.

The content analysis has been carried out on two groups of spots, those broadcast in Spain during lockdown and during the first phase of de-escalation. The messages, images, music and even the creative resources and tone of the spots have been evaluated to answer the research questions proposed.

Table shows the data sheet used for the analysis. Twelve variables were taken into account. Most of them are variables widely used in advertising research and introduce scales more typical of psychology for resilience and emotional charge based on the work of Grotberg (Citation1999), Grotberg et al. (Citation2015), and Brooks et al (Citation2020). In detail, these are: brand, sector of activity, place of broadcast, duration, full text, slogan, message typology, tone, emotional charge, resilience, voice-over and image resources.

Table 1. Analysis form

There are three types of variables: ordinal variables, such as ad duration; 5-point Likert scale such as tone, emotional charge and resilience; and nominal variables such as image resources.

The coding process was carried out by two groups of researchers to avoid inter-subjectivity. The double coding of the data has allowed to settle conflicts, to ensure the trust and eliminate the possible discordance following the proposal of Olson et al. (Citation2016).

2.2. Sample and data collection

The research has addressed 125 spots divided into two distinct samples coinciding with two periods of the health crisis: lockdown and de-escalation. The first group includes the total number of spots broadcast in Spain during the lockdown period (71), from March 14th to 21 June 2020. The second group was composed of 54 ad spots following a non-probabilistic discretionary quota sampling. These ads belong to the period from June 21st to 25 October 2020 coinciding with the first phase of de-escalation in which measures and restrictions were relaxed and preceding the so-called second wave of contagion.

An attempt was made to ensure that all sectors of activity were represented and that there was a parallelism between activities, product types and brands for both periods. Table shows the grouping of spots by sector of activity. In both cases, governmental advertising communication has been omitted, except in the case of spots for tourist destinations due to their relevance for the Spanish economy and because they are considered to be services of interest in the leisure and lifestyle of the Spanish population.

Table 2. Grouping of ads analyzed by sector

The total number of ads analyzed was 125, all of which were broadcast on television and, for the most part, simultaneously broadcast on YouTube and social networks.

The data was collected over 28 weeks (191 days). The 8 weeks of lockdown and the 20 weeks of the first phase of de-escalation and first social approximation to the so-called “new normality”.

The procedure followed to minimize research bias related to qualitative analysis entailed: reviewing the code by five researchers simultaneously; an extra coding phase for a random choice of ads to ensure the values and categories attributed to each ads regarding all their variables (Olson et al., Citation2016). In case of mismatches or doubt, a random crossover entry, the agreement of all the researchers was required.

2.3. Validity and confidence

The validity and confidence of this research is assured by three main issues:

The sample spots are compared by differentiating two key phases of the pandemic in Spain: lockdown and the first phase of the so-called de-escalation.

A representative sample of spots from all sectors of activity is ensured, in short, this favours the elimination of any bias in the sample, with respect to a particular advertising style or type of resource.

The application of statistical analysis of correlations adds value, increases the robustness of the results and the reliability of the comparison under research.

3. Results

After analyzing the advertising content, two strategies can be observed. On the one hand, in the lockdown phase there is a clear predominance of corporate advertising (71%) followed by hybrid advertising (29%) and no case of strictly commercial advertising. On the other hand, during the first phase of de-escalation, brands resort to sales-oriented advertising (41%), to spots that combine commercial and corporate purposes in the same proportion, and exclusively corporate advertising decreases to 18%. Given this difference in the typology of advertising, it has been deemed convenient to identify the association of corporate or commercial messages according to activity sectors in the de-escalation phase.

Figure shows the distribution graphically. Construction, the entertainment industry, the tourism sector and beverages continued to use corporate advertising, while household appliances, cosmetics and hygiene (hardly represented in the lockdown phase) and telephony were the sectors that made most use of purely commercial advertising. Finally, the distribution sector and the automotive sector, almost in the same proportion as with commercial messages, use hybrid spots.

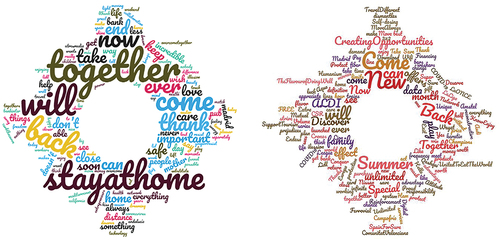

Figure 1. Comparison of Word cloud full-text of spots during isolation and de-escalation. (a) Word cloud full-text of spots during isolation. (b) Word cloud full-text of spots during de-escalation.

This trend also explains how during lockdown content was mainly aimed at encouraging the population and launching messages of solidarity. Likewise, it is worth mentioning the communicative line that projected the wishes for a return to normality and the prompt recovery from an unprecedented situation that entailed many social challenges due to the need to stay at home and not relate to the usual groups of belonging.

Brands adopted an active role in helping the population to overcome the situation derived from the pandemic with messages where resilience and the exposure of “psychological support” mechanisms to cope with the situation were the creative core (68%). Likewise, it is also relevant that 32% of the messages were connected to raising awareness for the prevention and containment of contagion.

During the first phase of de-escalation, the identification of resilient messages is practically nonexistent and other arguments and discourses are used to develop the creativity of the spots. In contrast, in both cases, the spots resort to a “very positive” (54% and 59% respectively) and “positive” (15% and 32%) tone. It is worth noting that during de-escalation no spot is attributed a “very negative” tone, while during lockdown there is a low but existent 1%. Likewise, realistic messages were more numerous during lockdown (27%) than during the period of adaptation to the “new normality” (7%).

Similarly, it is evident that the emotional load of the advertising messages was higher during the lockdown period, where the spots categorized as “very emotional” or “emotional” reached 60% of the total, while in the period immediately after the lockdown period it was reduced by almost half (33%). Just the opposite happens with the messages that are not emotional at all, in the first stage of analysis only a single spot is coded in this position of the scale while in the de-escalation 40% are coded in this category. The correlations between emotional charge and the type of advertising explain this issue at a level of 0.001. Thus, when the advertising is corporate the emotional charge is higher than when it is in commercial spots. Another positive correlation for both samples is produced when relating emotional charge with music as creative resources in the spot, in this case at a level of 0.005.

The most radical difference is evident in terms of resilience, the levels of which are higher in all the spots analyzed during lockdown and ceases to be relevant at a later time, where no spot is categorized with the values of “very resilient” or “resilient”. Clearly the orientation of the messages and the mentioned social or commercial function, depending on the period, explains this brand behaviour. Moreover, it should be emphasized that there is a brand’s common message in this line during the confinenment, everything will be ok, we can together, far to be closer … This issue is illustrated in Figures .

Regarding the content of the messages, there are clear coincidences in the topics addressed both during lockdown and in the later stage, although it is true that the similarity is more significant in the first period. The word clouds of the complete texts (dialogues, voice-over or written text) of the two samples of spots in Figure show this. Figure shows the word cloud for the slogans comparing both groups of ads.

Figure 2. Comparison of Word cloud of spot slogans during isolation and de-escalation (a) Word cloud of spot slogans during isolation. (b) Word cloud of spot slogans during de-escalation.

While it is true that the orientation of the discourse contrasts clearly in the two periods: messages of encouragement and strength, as well as supportive information to prevent and minimize contagion as part of the creative script of the spots and a clear orientation to consumption and the “joy” of returning to normality in the first phase of de-escalation, there are coincidences in the general semiotics of the messages. Adverbs such as “now”, “never” and “always” were key in both stages.

It is worth noting the repeated use of phrases such as “now, more than ever” in the two phases while “now, as always” is in line with the brands’ interest in conveying the desired normality in advertising messages from June 2020.

The group feeling was globally present with words such as: “all”, “together”, “we”, etc. being very frequent. By extension, words that link citizenship with their particular case such as: “country” and “Spain” can be highlighted.

The first period reflects that group conscience, a reflection on the particular reality and the collective feeling of belonging, while the supposed “new normality” urges the public to “discover” and “enjoy” its charms that, until now, had to be kept waiting to leave home.

On the other hand, the weight of the word “return” in its different forms in both phases stands out. However, during lockdown, with the idea associated with the hope that everything would return to the way it was before, and in the de-escalation linked to the fact that business, leisure and what was missed, had returned. If we refer to the verb tenses used, it is worth highlighting the contrast between the future, during lockdown, and the present in the advertising messages of the immediately subsequent phase.

As for words closely related to the pandemic such as “COVID-19”, “coronavirus”, “disease” etc, they were practically non-existent during the whole time of the analysis. Even words linked to the reality resulting from the health crisis such as “mask”, “social distance”, etc. have a residual presence. As an exception, the word “close” stood out during Lockdown and was used to counteract the negative feeling derived precisely from the need to stay away from the most beloved people such as family and friends. In this same line, with the difference being significant with respect to the period of analysis established from June 21st (2020) epic verbs were very common for the marks from March to June: “resist”, “fight”, “combat” or “win”, as well as verbs intended to show nostalgia for things that were missed because of the special situation of staying at home; “hugs”, “kisses”, “travel”, “health”.

In contrast, the complete absence of words such as “price”, “pay”, “buy” and “offers” in the entire sample of spots from March 14th to June 21st (2020) stands out and reaches a significant level of representation from the end of June onwards. In contrast, the appearance -completely nonexistent in the entire sample of spots from March 14 to June 21- of words such as “price”, “pay”, “buy” and “offers” stands out, which do reach a significant level of representation from the end of June onwards. Similarly, “now”, “summer” or “enjoy” are noteworthy and again insist on the idea that after the hard time-shared during lockdown, it is necessary to return to normality. On the other hand, during lockdown, there were common hashtags in the messages of lockdown publicity, highlighting “IStayAtHome” and, with a great distance, “BrakesTheCurve “.

Regarding the slogans, there is a consistency between the ideas reflected in the full text of the ads for the two samples. While during lockdown there is a clear predominance of the hashtag #StayAtHome #IStayAtHome etc, as well as words such as “together”, “now”, “back”, in the de-escalation the weight distribution of the most common words is more balanced and there are no prominent words shared by most brands in their claims.

Finally, the image resources related to the pandemic used in the two samples of spots have been highlighted. During lockdown, the closure of non-essential activities, such as advertising, as well as the fact that the most commonly represented scenario is the domestic one, also affects the graphic and visual resources with which the spots are elaborated. Consequently, it is less surprising that the percentage of people wearing masks, keeping safe distances etc, is low (18%) and is more remarkable when health workers or other groups are shown as heroes or as the key to overcoming the difficult situation the population was going through. On the other hand, the following period does not reflect the social reality that demands the compliance with some measures for the effective entry of the “new normality”, only 26% of the advertisements expressly include them. It is worth mentioning that a pattern by sectors has been observed in this regard, the entertainment, telephony, household appliances and hygiene and beauty sectors have never used them while the tourism, transport and beverage sectors have been the ones that have incorporated more specific visual records linked to COVID-19. Finally, it should be noted that corporate and more emotionally charged advertisements have shown a higher rate of use of these resources, with the mask being the most recurrent.

4. Conclusions and discussion

This research provides a new approach for the analysis of the communication of companies in crisis situations, as well as for understanding brand strategies and their social contribution.

From the results of the analysis the three research questions are answered. it is clear that brand owners have faced the challenges of COVID-19 by adapting their discourse, images and creative resources (RQ2). However, the social function acting as a support to the psychological health of the population with encouraging and resilient messages prominently defines advertising during lockdown.

Companies have opted to show social commitment, empathy and, therefore, to work on branding. On the other hand, the advertising broadcast in the first phase of the de-escalation concentrated more effort on transmitting that the “new normal” was a reality. Consequently, it prioritized commercial objectives and left the importance of the pandemic in the reality of brands and their consumers in the background. Therefore, according to RQ3, there are two types of advertising well differentiated for each relevant moment of the COVID-19 health crisis. In a way, brand advertising communication combines their interests. On one side, brand presence and recognition but, on the other hand, brands made an effort to support prevention, containement and coping with the health crisis from their discourses, images, etc. Therefore, brands adapted to the unprecedent situation also in their commercials. The evidences related with lockdown and immediately after enable to partially answer the RQ1.

The urgency to reactivate consumption has led to a change in messages, although it is true that corporate advertisements and the introduction of certain visual resources that reflect the mandatory measures in our daily lives are evident.

During the lockdown period, a common pattern in message orientation and visual aesthetics was more homogeneous among the firms than in the period from June 21st to October 25th (2020).

According to Holbrook (Citation1987), advertising reflects reality, in this case the reality experienced by Spaniards in the two periods, in the first, mainly showing how they live the forced preventive measure of staying at home, and in the second period, mainly projecting the routine and social activity of the “new normality”. However, it is possible to notice an intention to relax the pressure that the beginning of the health crisis had meant with the most drastic measures and, to a certain extent, the brands transfer this to their advertising showing naturalness in the introduction to the “new normality”. In this sense, they have also played a supportive role in the feelings of anxiety, stress or uncertainty of the population coinciding with Verlegh et al. (Citation2021).

According to Grotberg et al. (Citation2015), Grotberg (Citation1999)), familiarizing oneself with new realities in a natural way and not focusing on comparing better situations is a way to move forward in the face of situations that can be qualified as traumatic. In this way, although with different creative strategies in each period, there is evidence of a contribution to the emotional and psychological well-being of the population and, therefore, of consumers.

In line with the works that analyze crisis management through communication, advertisements have tried to be a source of information as well as to provide positive feelings and actions to mitigate the effects of a crisis (Reynolds & W. Seeger, Citation2005). In the same way, as Taylor (Citation2020a) and Vorhaus (Citation2020) point out, the pandemic has also meant a radical change in the advertising sector and has demanded the adaptation and reconversion of the discourses, orientation and creativity of the campaigns.

In particular, there are certain parallels with the work of Grotberg et al. (Citation2015), Grotberg (Citation1999), and Brooks et al (Citation2020) regarding the management of psychological pressure during a crisis, although the originality of this work with respect to previous literature lies in giving prominence to the role that advertising communication can play in this area.

4.1. Limitations and future lines of research

The main limitation of this research stems from the continuity of the pandemic and the need to continue analyzing over time how the advertising strategies of companies evolve and to what extent they assume their social role in helping to curb contagion and the various new waves that have been occurring worldwide. In the case of Spain, it would also be convenient to see the behaviour of brands from the new state of alarm declared on October 25th (2020) and which extended until May 9th, 2021. In this sense, a more extended analysis in time incorporating samples of ads from the different key moments of the crisis, as well as an international comparison are presented as future lines of research.

4.2. Practical implications

The pandemic has meant a radical change in the lifestyles of the general population and has even changed their view on the demands or expectations about the role that companies should assume in the face of the problem; firms can take advantage of this opportunity to connect with their consumers, strengthen their reputation and strengthen their relationships with customers by exercising their social function also through advertising. At the same time that this work raises the issue of the contribution of companies in the psychological support and emotional health of the population, it has highlighted the possibility of contributing to the containment of the disease and, therefore, companies could reflect the new reality and responsibilities to achieve the true “new normality” with more impetus. In short, firms should not fail to assume that the social function in advertising campaigns can increase their credibility and can help to improve their positioning and reputation globally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carlos de Las Heras-Pedrosa

Dra. Patricia P. Iglesias-Sánchez is Lecturer in Marketing, obtained the Outstanding Doctorate Award from the Economy and Business Faculty. Malaga University. She has a wide expertise and knowledge about companies and their management. Her lines of research are: social media, Open Innovation and gender.

Dra. Carmen Jambrino-Maldonado is a Professor of Communication and has been the managing director of the Doctoral programme “Research and Marketing”, the research team “Marketing for SMEs” of Faculty of Commerce and the Research Vice-Dean of the Faculty of Commerce and Management. University of Malaga.

Dr. Carlos de las Heras-Pedrosa is a professor in the field of Communication. Principal Research of the project “Communication Management in Startups led by women” (PY20-00407) University of Málaga. Spain.

Noelia Frías Villegas is involved in the research group: “Communication Management in Startups led by women”.

Dr. Fernando Olivares-Delgado is Director of the Chair of Family Business and Direction of the Chair of the Corporate Brand. Director of the University of Alicante Brand science research group.

References

- Barlovento Comunicación. (2020a). Balance del Consumo de Televisión durante el Estado de Alarma (del 14 de marzo al 20 de junio de 2020). https://www.barloventocomunicacion.es/wp-

- Barlovento Comunicación. (2020b). Consumo de internet vs. Televisión. Periodo de Análisis: Septiembre 2020. https://www.barloventocomunicacion.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Informe-Barlovento-consumo-Internet-Comscore-y-Television-Septiembre-2020.pdf

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, R. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8

- De Las Heras-Pedrosa, C., Sánchez-Núñez, P., & Peláez, J. I. (2020). Sentiment analysis and emotion understanding during the covid-19 pandemic in Spain and its impact on digital ecosystems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155542

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Eurostat. (2021). Recovery Dashboard. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/recovery-dashboard/

- Fernández Beltrán, F. (2020). La pandemia acelera y transforma los procesos de cambio comunicativos. Revista Científica de Estrategias, Tendencias e Innovación En Comunicación. AdComunica, 20(20), 381–383. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2020.20.16

- Grotberg, E. (1999). The International Resilience Research Project. Psychologists Facing the Challenge of a Global Culture with Human Rights and Mental Health, 239–256. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED417861.pdf

- Grotberg, E., Knuckey, S., Satterthwaite, M. L., Bryant, R. A., Li, M., Qian, M., & Brown, A. D. (2015). Mental health functioning in the human rights field: Findings from an International Internet-Based Survey. PLoS One, 10(12), e0145188. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145188

- He, H., & Harris, L. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. Journal of Business Research, 116, 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.030

- Holbrook, M. B. (1987). Mirror, mirror, on the wall, what’s unfair in the reflections on advertising? Journal of Marketing, 51(3), 95–103. JSTOR https://doi.org/10.2307/1251650

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Jambrino-Maldonado, C., de Las Heras-Pedrosa, C., & Fernandez-Díaz, E. (2021). Closer to or further from the new normal? Business approach through social media analysis. Heliyon, 7(5), e07106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07106

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Vaccaro Witt, G. F., Cabrera, F. E., & Jambrino-Maldonado, C. (2020). The contagion of sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: The case of isolation in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5918. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165918

- Kantar. (2020). COVID-19 Barometer. https://www.kantar.com/campaigns/covid-19-barometer

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- OECD. (2020). Evaluating the initial impact of covid-19 containment measures on economic activity. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/evaluating-the-initial-impact-of-covid-19-containment-measures-on-economic-activity-b1f6b68b/

- Olivares-Delgado, F., Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., Benlloch-Osuna, M. T., De Las Heras-pedrosa, C., & Jambrino-Maldonado, C. (2020). Resilience and anti-stress during COVID-19 isolation in Spain: An analysis through audiovisual spots. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238876

- Olson, J. D., McAllister, C., Grinnell, L. D., Walters, K. G., & Appunn, F. (2016). Applying constant comparative method with multiple investigators and inter-coder reliability. The Qualitative Report, 21(1), 26–42. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2447

- Pabón Montealegre, M. V., Jimenez Serna, V., & Sierra López, A. (2013). Relación entre la responsabilidad social y la publicidad social en las organizaciones. Comunicación, 30, 67–76. https://revistas.upb.edu.co/index.php/comunicacion/article/view/2859

- Reynolds, B., & W. Seeger, M. (2005). Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. Journal of Health Communication, 10(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730590904571

- Ripon, R. K., Mim, S. S., Puente, A. E., Hossain, S., Babor, M. H., Md, Sohan, S. A., & Islam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological effects on a COVID-19 quarantined population in Bangladesh. Heliyon, 61, E05481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05481

- Schaefer, S. D., Terlutter, R., & Diehl, S. (2020). Talking about CSR matters: Employees’ perception of and reaction to their company’s CSR communication in four different CSR domains. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1593736

- Shoenberger, H., Kim, E., (Anna), & Sun, Y. (2021). Advertising during COVID-19: Exploring perceived brand message authenticity and potential psychological reactance. Journal of Advertising, 50(3), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1927914

- Somos Marketing. (2020). La importancia de la publicidad en tiempos de coronavirus. https://somosmarketing.lasprovincias.es/tendencias/la-importancia-de-la-publicidad-en-tiempos-de-coronavirus/

- Taylor, C. R. (2020a). How brands can successfully engage with consumers quarantined due to COVID-19. Forbes.Com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/charlesrtaylor/2020/04/01/how-brands-can-successfully-engage-with-consumers-quarantined-due-to-covid-19/#82eb16c3fc23

- Taylor, C. R. (2020b). Advertising and COVID-19. International Journal of Advertising, 39(5), 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1774131

- Timothy Coombs, W., & Jean Holladay, S. (2014). How publics react to crisis communication efforts. Journal of Communication Management, 18(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-03-2013-0015

- UTECA. (2020). Barómetro sobre la percepción social de la Televisión en Abierto. https://uteca.tv/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/INFORME-BAR%C3%93METRO-SOBRE-LA-PERCEPCI%C3%93N-SOCIAL-DE-LA-TV-EN-ABIERTO.pdf

- Verlegh, P. W. J., Bernritter, S. F., Gruber, V., Schartman, N., & Sotgiu, F. (2021). “Don’t worry, we are here for you”: Brands as external source of control during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Advertising 50(3), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1927913

- Vorhaus, M. (2020). COVID-19 represents the biggest challenge to media advertising expenditures eve. Forbes.com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikevorhaus/2020/04/27/covid-19-represents-the-big-gest-challenge-to-media-advertising-expenditures-ever/#5b207e357398

- World Health Organization. (2021). COVID-19 situation in the WHO European region. https://who.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/ead3c6475654481ca51c248d52ab9c61

- Xifra, J. (2020). Comunicación corporativa, relaciones públicas y gestión del riesgo reputacional en tiempos del Covid-19. El Profesional de La Información, 29(2), e290220. http://dx.doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.20