Abstract

The lives and livelihoods of rural communities are affected by climate change in Pakistan. These impacts vary between households, localities and individuals of the same household due to a diversity of livelihood strategies and differing needs. The aim of this study, therefore, was to understand how gender may highlight vulnerability to climate change through a combination of complex and interlinked factors that results in different vulnerabilities for men and women. The study was conducted in three rain-fed localities of Pakistan’s Punjab that represented three different climatic zones namely high rainfall, mid rainfall and low rainfall. The qualitative research method was employed with the help of 30 key informant interviews (15 women, 15 men) that were undertaken to understand gender roles, responsibilities and livelihood strategies. Finding of the study revealed that there is an increased frequency and duration of extreme climatic events and natural disasters with great uncertainty about the rate of change. Women stands on the frontline of these disasters to bear its impacts but with limited and restricted access to human, financial and natural capitals, and this is driving an expanded vulnerability to climate change in study area. Overall, women were culturally and socially dependent on men in a way that increased vulnerability to climate change. It was observed that women empowerment could play an important role in building the resilience toward climate change; hence, voices of women need to be raised and heard. Women groups should be established in each community where they can come and discuss about their issues and suggest possible solutions. Overall, there is a need in improvement of livelihoods and strengthening the adaptation capacity by ensuring women’s access, control and ownership of resources. Women involvement should be considered in developing climate adaptation strategies and policies.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This research explored men’s and women’s climate-induced vulnerabilities in rain-fed rural set up of Pakistan. Results revealed that women access and control over major livelihood assets (human, social, financial, physical and natural) is restricted, or they have only access to these resources with the permission of their male counterpart. Men in the society are perceived as planner and decision maker and women are thought to be custodian of their children and household chores. Erratic rainfall, rising temperature and drought are major observed climatic shocks. Women’s adaptive capacity face constraint due to social and cultural set up of the society. Women play an active role in livelihood earning, despite this, women work acknowledgment is unpaid at household level and under researched at policy level.

1. Introduction

Rural areas in the developing world are characterized with great dependency on farming, low adaptive capacities, low human development levels and relative lack of consideration from policymakers (Dasgupta et al., Citation2014; Wymann von Dach et al., Citation2017). Climate change creates serious consequences for rural localities through with a direct impact on rural livelihoods. Semi-arid rural economies are predominantly based of natural resources. Rural livelihoods are formed by a set of intricate economic, political, biophysical and institutional indicators (Dasgupta et al., Citation2014; Ishaq & Memon, Citation2016). These include aspects of governmental agricultural policies, agricultural extension services, markets availability, tax structure, subsidies and physical infrastructure with addition of natural resource base characteristics such as quality and fertility of soil and irrigation facilities (Biemans et al., Citation2019). Manifestations of these impacts on livelihoods may occur either through a gradual onset of climate change affecting average temperatures and rainfall or through extreme events including droughts, erratic rainfall and heat waves (Dasgupta et al., Citation2014; Habib, Citation2021).

Emergent and ongoing research (Aguilar, Citation2009; Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Alston, Citation2014) indicates that climate change has caused vulnerabilities and impacts on societies that are gendered. Women and men are impacted differently by climate change because of their different vulnerabilities. Women have different traditional roles, societal expectations and livelihoods. Usually, women suffer from inequality and are found to have lower incomes, less access to knowledge and extension facilities, restricted control over assets, less accessibility for financial resources and limited decision-making authority (Jost et al., Citation2015).

Due less education for women they face more vulnerabilities than men to climate change and often limited property privileges, making it much more difficult to access financial resources or institutional services, e.g., extension representatives (Gurung et al., Citation2010). Women thus face disadvantage in exercising their powers and accessing resources. They are usually more exposed to climatic risks, both during and after a disaster. While climatic variability does not always result in disadvantage and detrimental situations for women (Dankelman et al., Citation2008), in many occasions women are expected to treat unduly with greater negative impacts than men due to prevailing deep-rooted gender compositions and power associations (Ahmed et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, policies and programs aimed at strengthening and developing the adaptive capacity of local people often fail to realize the gendered nature of climate change responses and impacts (Alston, Citation2014). Women are typically portrayed as vulnerable, weak, socially isolated and poor rather than looking into their lives to see how they are dealing with climatic change (Okali & Naess, Citation2013).

Pakistan is facing a climate change challenge as in other parts of the world the Global Climate Risk Index 2021 ranked Pakistan the 5th most vulnerable country to climate change. Increasing intensity and frequency of excessive climatical events has disturbed the natural resource base with phenomena like frequent floods, erratic rainfall, drought and deterioration of soil fertility and reduction of crops productivity (Biemans et al., Citation2019; Hussain & Mudasser, Citation2007; Siddiqua et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the limited adaptive capacity of poor people reinforces a vicious circle of poverty (Wymann von Dach et al., Citation2017).

In particular, climate change has adversely affected the agricultural sector, which is the backbone of Pakistan’s economy. The major adverse impacts include decrease in crop productivity, shortening of growing seasons and reduction in water availability (GOP, Citation2018). Women play an essential role in the effective performance of agriculture; hence, existing climatic pressures are making women more vulnerable. Women’s participation in different livelihood activities is determined by various cultural norms and socio-economic conditions (Ashok & Sasikala, Citation2012; Meinander, Citation2009; Van et al., Citation2008). Women’s participation in agriculture is more than men’s but mostly goes unnoticed (Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Habib & Muhammad, Citation2014; Hussain & Mudasser, Citation2007). Therefore, it is important to understand climate-induced vulnerabilities in the agriculture sector in Pakistan using a gender lens.

The study focuses on a region of the Pakistan Punjab known as the rain-fed Punjab, which is highly vulnerable to climate change (Muhammad et al., Citation2016; Naheed et al., Citation2017). In the rain-fed Punjab, men have gradually moved away from farming sector to differentiate their household incomes, while women role increases for managing the family farms in absence of their men (Habib et al., Citation2015; Ishaq & Memon, Citation2016). The issues relating to gender vulnerability vary with different rainfall zones. Hence, the study region was stratified into three zones based on annual rainfall: i) low rainfall zone (<500 mm), ii) medium rainfall zone (500–750 mm) and high rainfall zone (>750 mm). Previous research on climate change adaptive measure has broadly considered a natural system perspective leaving a knowledge gap on human system, such as knowledge in terms of how men and women react and perform differently in any climatic disaster is missing in world literature. Understanding gender wise impacts and vulnerabilities are important for determining which type of adapted livelihood strategy could be useful for specific group of gender with climatic context. Therefore, this research venture is imperative because it explores the bigger livelihood vulnerabilities portrait with gender lens and filled the gaps that have been yet addressed by researcher in a study.

The study investigated three research questions:

What is gender differentiated roles and responsibilities?

What is the gender difference in access and control of livelihood resources?

What is the current state of knowledge about gender differentiated vulnerabilities in managing livelihoods with context of rain-fed conditions?

This paper contributes to the existing literature in three important ways. First, the study contributes evidence from a region of Pakista,n which has been little studied. Second, the study was designed with a special focus on gender differentiated livelihood activities and vulnerabilities in Pakistan, which previous studies have not rigorously investigated. Third, the findings of the study have important policy implications for understanding gender differentiated vulnerabilities in planning future developmental projects and policies.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents materials and methods. Section 3 presents results. Section 4 discusses the findings, while Sections 5 and 6 represent limitations of the research and concludes the paper, respectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Research paradigm

A research paradigm is a philosophy that guides a researcher in studying, evaluating and understanding a situation, particularly in a social sciences research (Creswell, Citation2012). The components of research paradigms include ontology, epistemology and methodology (Krauss, Citation2005). Ontology is involved with understanding the nature of reality, its elements and relationship among selected elements (Blaikie, Citation2009; Creswell, Citation2012), epistemology refers to what constitutes acceptable knowledge (Blaikie, Citation2009; Saunders et al., Citation2009). These two components (ontological and epistemological) lays the foundation for the research methodology, or the way in which knowledge is gathered (Krauss, Citation2005). Methodology deals with the logic of scientific inquiry and its underlying assumptions and limitations (Gelo et al., Citation2008; Saunders et al., Citation2009).

The literature on research methodology presents the four types of research paradigms: positivism, critical, pragmatism and constructivism (Saunders et al., Citation2009). For this study selected research paradigm is constructivism because constructivists or qualitative conformists think about that reality has multiple faces, interrelations and interdependences, which can be known by developing various intellectual ideas (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005; Maxwell, Citation2013). This approach urges the complete involvement of the researcher in social inquiry so as to generate a thick and rich understanding of reality (Gelo et al., Citation2008). Inductive approaches and qualitative research methods are considered appropriate by this school of thought for seeking insight into research problems. The major strength of this approach is that it leads to a deep understanding of a research problem in a particular setting because of the close interaction of the researcher with the phenomenon (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008).

To analyze and understand the current state of knowledge gender differentiated roles, responsibilities, access and control over resources and vulnerabilities in managing livelihoods with context of rain-fed conditions. This study adopted following research paradigm (). In qualitative studies, key informant interviews (KIIs’) method is a very important tool and is generally conducted with the relevant sector specialists, researchers, government officials, women, community leader, civil society members and local governments’ representatives. Key informants should be selected for their specialized knowledge and unique perspectives on a topic. Key informant interviews help to build shared understanding on issues and suggest responses for the targeted groups and actors.

2.2. Selection of study location

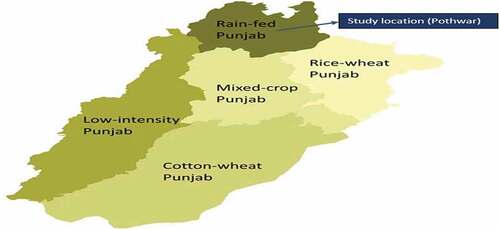

Punjab is the largest and most agricultural province of Pakistan and is divided in five Agro-ecological zones ().

Mixed cropping Punjab: The mixed zone of Punjab constituted on seven districts namely Sargodha, Khushab, Jhang, Faisalabad, Okara, Chiniot and Toba Tek Sing. The major agricultural strategies of this zone are crops, livestock, fodder, fruits and vegetables (GOP, Citation2020).

Rice-wheat Punjab: The rice-wheat cropping system of Punjab is centered in the districts of Gujranwala, Sialkot, Nankana Sahib, Sheikhupura and Hafizabad, and these districts contains canal irrigation system and includes 1.1 million ha of farming land (GOP, Citation2020).

Low intensity Punjab: This zone is most affected zone of Punjab in terms of climate change after rain-fed Punjab. The zone constated on six districts namely Dera Ghazi Khan, Muzaffar Garh, Rajan Purr, Layyah, Bhakkar and Mianwali. The major source of livelihoods for this zone are wheat and pulses (GOP, Citation2020).

Wheat-cotton Punjab: This zone has nine districts and major source of agriculture in this zone are wheat and cotton crops.

Rain-fed Punjab: The northern part of province rain-fed Punjab is selected for this study. This covers an area of about 15,830 sq kms and comprises of the districts of Attock, Rawalpindi, Jhelum and Chakwal. It is about 250 km long and 100 km wide with elevations ranging from 200 meteres along River Indus to about 900 meteres in the hills north of Islamabad with an average elevation of 457 meteres (Khan, Citation2002). The vulnerabilities and risk related to climate change are high among the communities living in this rain-fed rural region of Punjab due to limited livelihoods opportunities. Therefore, this study opts to select this region to best identify gender differentiated livelihood vulnerabilities that can better serves for policy initiatives and researchers.

Figure 2. Map of Punjab showing the study locations in rain-fed Punjab (adapted from (Khan, Citation2002).

2.3. Conceptual framework

Initially until 1980ʹs it was assumed that climate change related vulnerabilities are induced through biophysical indicators or due to external risks and social scientist were also applying this biophysical definitions for vulnerability studies (Adger, Citation1999; Hewitt, Citation2005). But later on in Wisner et al. (Citation2003) and Hewitt (Citation1983) initiated a standard shift with a rising appreciation that these vulnerabilities that arise from different hazards are heterogenous toward person to person or locality to locality and that these are not only based on biophysical indicators but rather these vulnerabilities are determined by social structure of the society (Habib, Citation2021).

Additionally, an essential aspect of vulnerability is that it is gendered, indicating that men and women have different capabilities to react to changing climatic parameters and its linked risk (Aguilar, Citation2009; Alston, Citation2014; Lambrou & Laub, Citation2004; Lambrou & Piana, Citation2006; Terry, Citation2009). A growing number of research bodies that have scope of studies about gender and climate change agreed and mentioned several evidence that climate change impacts are not gender neutral and added that disasters linked to climate change have higher adverse impact for women comparing with the men of the society. This gender differentiated impacts further worsen the conditions of women agency in term of gender inequalities (Bennett, Citation2005; Lambrou & Laub, Citation2004). But this does not meant that women are inherently vulnerable (Sultana, Citation2010; Wisner et al., Citation2003). It is not the women but the society social-cultural norms and rules that make women vulnerable. Gender and gendered differences are socially created, shaped by local cultural and social norms at a specific historical occasion. These structures are not steady but unstable, performative and varying over time to emulate developing experiences (Alston, Citation2014; Terry, Citation2009).

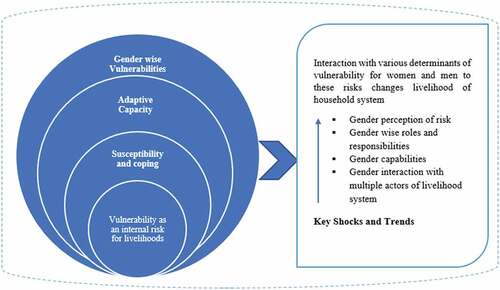

As the concept of vulnerability has evolved, Birkmann (Citation2013) concludes that it has widened to become a multi-dimensional construct that encompasses many components including livelihood capitals and institutional features such gender, class, caste and age. The Birkmann’s framework illustrated gender wise roles, responsibilities, capabilities to face livelihood risks and in more detail the intricate intersection of several components influencing vulnerabilities differently based on various determinants of vulnerability for men and women (see, Figure ). Using Birkmann’s wider framework of understanding multi-dimensional gender-based vulnerabilities, the present study considers how various forms of capital (human, financial, physical, natural and social) from the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF; DFID, Citation1999) underpin gender-based vulnerability in the study sites.

Figure 3. Gender differentiated framework for analysis of vulnerabilities (adjusted from Birkmann, Citation2013).

2.4. Data collection and analysis

This study is based on primary qualitative data and a sample of 30 key informant interviews was decided to complete with a detailed checklist. The respondents were selected based on gender (male & female), landholding size (less than 5 acres) and age of ≥50 years. The selection of key respondents’ procedure was made with the help of Agriculture Extension Department of Punjab and National Rural Support Program as they have very strong grass root level network in Punjab (Pakistan). Then, potential participants were contacted and asked about their willingness to take part in this research. Potential participants were informed that they need to consider to be involve with the researcher in a 1.15 hours conversation if they are willing to take part. When the participants express their willingness, then the main researcher has arranged the appointment (date and time) for interview. Because, due to pandemic (COVID-19) and Australian government travel ban, data was collected through telephonic and Skype interviews with the selected respondents from the three selected rainfall zones mentioned above. The interviews were conducted with knowledgeable persons (male and female), agricultural officials and working women in each selected zone to gain an understanding of the overall livelihood situation of the communities. These telephonic and skype meetings were during May–June 2020. This research caused discomfort or inconvenience to the participants in a very minimum way due to online data collection method (skype and telephonic). Interviews were conducted as per committed time of the participants that was easily managed. All the discussion were made in the most plain, understandable and less technical and in simple language. Table presents the sample profile for KII.

Table 1. Detail of KII sample profile from study locations

Modified gender analysis framework (GAF) was applied for collection and analysis of qualitative data in order to understand overall gender needs, access to and control of resources, benefits and incentives, vulnerabilities and capabilities (Bhadwal et al., Citation2019; Habib, Citation2021). To understand the complex process of manifestations of gendered vulnerabilities, this study adopted following gender analysis framework tools for descriptive and thematic content analysis of gender roles and responsibilities, entitlements and capabilities of livelihood assets and gender vulnerabilities to address the current study objective.

Gender activity analysis captures information relating to gender division of labor and roles in the different spheres of life, helps to analyze roles, skills and capacities or capabilities.

Gendered access and control to resources analysis captures information relating to who has access to and control over different types of resources, helps to analyze decision-making roles and power dynamics.

Benefit and incentives analysis captures who get benefits and incentives in relation to the activities and resources, helps to analyze the position, status and power dynamics.

Institutional constraint and opportunity capture information relating to who has access to which institutions and benefits, what constraints are faced by those without access, and helps to analyze the position, status and power dynamics.

Vulnerability analysis Captures information relating to climatic vulnerabilities and their impacts on livelihood sectors and social groups. This tool is used on the basis on the information collected from the above tools to facilitate analysis of gendered vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities.

3. Results

3.1. Climatic trends and hazards

Rural livelihoods in rain-fed regions of Pakistan’s Punjab are increasingly exposed to climate impacts. The major climatic hazards identified by the participants (n = 30) during key informant discussions include rise in temperatures and erratic rainfall over the last two decades. These hazards affect the natural-resource-based activities of the communities, especially agriculture and livestock. The increased temperature at certain important crop stages results in decline of yield and increased insect attack. Similarly, the livestock sector also suffers with an increase in foot and mouth disease in small ruminants due to exposure toward high temperature, while excess heat decreases the health, growth, and milk yield of large ruminants. Erratic rainfall has also caused crop yield reduction, especially heavy rain spells at the time of flowering and crop harvest. The low-income groups in the communities and those that were fully dependent on agriculture and livestock for their livelihoods were the worst affected. However, the majority of the participants (n = 30) in the area do have diversified sources of income that allow them to cope with the climatic stresses and the losses from these stresses.

Table presents trends in relevant hazards of concern over the last two decades. The ranking of the trends was finalized on basis of responses for each hazard received from all key informant interviews (n = 30) who were mature enough (with age ≥50 years) to remember the trends of climate change for the last two decades. The trends are presented with the sign of a + and can be explained as, the more plus signs the more significant (impactful) is the trend and if the number of plus signs increases (decreases) from one decade to the next this indicates the trend has become more (less) significant. The analysis reveals that, across the three zones, trends in rising temperature, erratic rainfall, and fog are increasing, while cold waves have decreasing tendency in all zones. In the lower rainfall zone, erratic rainfall, temperature rise and drought had become the main hazards for the community. In addition, fogsFootnote1 had increased many folds in the previous few years, lasting for almost a month and resulting in decline of crop yields, livestock growth and farm productivity, as well as affecting the day-to-day activities of household members. Increase in temperature and erratic rainfall were the most significant trends in the medium rainfall zone. The high rainfall zone had seen reduced snowfall in the winter and increased intensity and duration of hailstorms in the summer.

Table 2. Reported trends of major climatic hazards in the Rain-fed Punjab by rainfall zone, 2000–2019

The climatic variation between the zones is quite distinct such that the high rainfall zone receives heavy rainfall and snows in winter whereas the low rainfall zone is drought prone. The top four rankings of climate change hazards given by the key informants are presented in Table . These ranking were estimated based on number of votes for each hazard provided by participants (n = 30) of the study. The interviewees in all zones ranked rise in temperature as the most important climate hazard. Erratic rainfall was ranked second in the high and medium rainfall zones. Drought was ranked second in the low rainfall zone, third in the medium rainfall zone and fourth in the high rainfall zone. The biggest contrast was that snowfall was ranked third in the high rainfall zone with decreasing trend, whereas fog was fourth in the other two zones.

Table 3. Ranking hazards

3.2. Distribution of gender roles and responsibilities

Gender division of labor is a product of the social system which indicates how men and women are expected to participate in different activities to contribute to livelihoods. However, these norms are becoming blurred over time. Women are not entirely confined to the household domain as in the past but are also entering in economic sectors and contributing to household livelihoods. To strike a balance between their “indoor” and “outdoor” work women have to struggle to establish their rights in the family, the society, and the state because social attitudes have not changed to match the changed realities In Pakistan, the autonomy of women is limited by traditional cultural and religious constraints. This results in women having little access to the social and economic opportunities that would otherwise be available to them.

In the communities studied in the Rain-fed Punjab, it was observed that men are considered as the breadwinner of the family through engaging in outside work such as cultivating crops, wage laboring, driving automated rickshaws or vans, masons, construction labor, tractor drivers, tailoring and small business (shopkeeper). Most of the employment is male dominated, except agriculture, which is the only activity in which men and women are participating jointly.

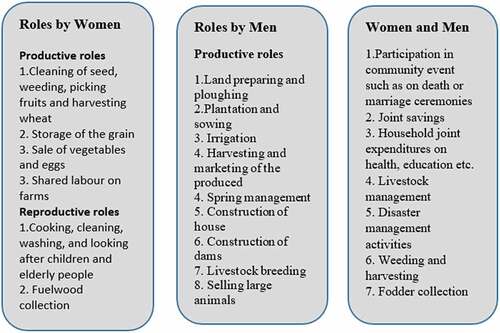

The gender roles and responsibilities at the household and farm level identified by the key informants are summarized in Figure . A significant number of women from poor and marginalized households are directly participating in the same productive work as men but in a submissive role, taking direction from men., They are also expected to maintain household chores and responsibilities along with their productive work. As farm laborer, women predominate in sowing, planting, weeding and harvesting crops and storage of the output. Occupying a secondary spot in the family and the community, women take the major responsibilities in the reproductive roles of the family. From early morning to late at night, women continuously do all types of household chores like cooking, cleaning, washing, taking care of their children, husband and livestock.

3.3. Gender entitlement and capabilities for livelihood capitals

Following the DFID sustainable livelihoods framework (DFID, Citation1999), an effort was prepared to recognize the gender entitlement and abilities in the selected study area of Pakistan based on gender wise livelihoods’ access and control. Generally, in Pakistan, there are gender particular distinctions in the form of work, usage of different resources, life patterns, customary rituals, consumption patterns and control over and access to livelihood resources.

In overall Pakistan’s society has set gender wise norms and patterns, therefore, there are not too many distinctions that one can summarize across all selected zones (rain-fed Punjab), but the biggest difference arises with women lacking ownership of physical and natural capitals. Women were also struggling with social capital, as during discussions it was perceived that woman have mobility hurdles in lower and medium rainfall zones. Because women were not allowed to go outside their house for market or anywhere else without the permission of their male members and this was due to set social norms of the society. Women were also lacking in access to and control over financial resources as finances were controlled by men in all zones. Results indicates that instead women actively participation in household economic livelihood generating activities that includes livestock rearing and farming, their role in economic decisions is minimal for example, decisions associated to choice of crop varieties, buying or selling of large animals, business investments and usage of family income within household or outside the house was performed solely by men. However, they have access toward agricultural land and livestock primarily through with their men. Further summarized details about gendered entitlement and capabilities are mentioned in Table .

Table 4. Gender entitlement and capabilities

3.4. Gender perception of climatic vulnerabilities and their impacts on livelihoods

Climate change vulnerabilities are gendered. These are shaped by the roles, responsibilities and dependency among men and women of different social groups, age cohorts, castes, educational status and marital status. Attempts were made to recognize women’s sensitivities of vulnerabilities related to changing climate e and their adaptation strategies.

The majority of women perceived more frequent incidence of erratic rainfall, drought and high rainfall in recent years. Livestock rearing and crop production are becoming challenging for smallholders’ farmers because of unpredictable rainfall and other climatic factors such as drought, fog and snow falling in different zones of the study. Women were agreed that climate change has reduce farm productivity and overall family incomes in all three zones. In high rainfall zone fruit productivity declined by 50% for almost all fruits orchards. They mentioned that during unpredictable natural hazards their families face food shortage due to loss of their livelihoods during disaster periods. In form of adaptations during hazards, they reduce consumption on food items, purchase of clothes, replacing expensive goods with cheaper items or sometimes they borrow money from family or friends to reduce the impacts of shocks. As a major adaptation measure, they said (>80% participants) they reduced their expenditures on cloth.

Women’s health was being affected by intense heat in the course of wheat harvesting because in harvesting activity female participation was high. A woman from the high rainfall zone reported that water collection from springs is very hard for women. Sometimes women suffer from hair loss due to bringing water on their heads from long distances. Diseases, injuries and infections are more frequent for women during disasters days of hailstorm, cold waves, erratic rainfall and fog. They also communicated their concern about the security of their girls whose duty is to get water from long distance in the evening. Livestock was affected due to the extreme weather from November to March in these months’ villages in the high rainfall zone experience snowfall. Women from low rainfall zone mentioned that “changing climate has affected their lives more than men. As men role is only buying and sowing the seeds in farms and their role ended very soon before harvesting stage come. However, women remain in the field until the crop is ready for harvest and till the storage of that produce”. Table shows the vulnerability matrix that depicts the impact of different vulnerabilities on livelihoods and social groups. The ranking of each vulnerability is based on number of votes for each hazard from total sample of the study (n = 30).

Table 5. Vulnerability matrix

4. Discussion

The rain-fed Punjab is highly sensitive to extreme weather events (Hussain, Citation2010). These larger sensitivities encounters combined with strenuous topography raises further challenges for both women and men (Aguilar, Citation2009; Ahmed et al., Citation2016). Additionally, provided the livelihoods dependence on climatic sensitivities, namely livestock rearing and farming, a bigger exposure to vulnerabilities is observed (Aguilar, Citation2009; Hemani, Citation2015; Siddiqua et al., Citation2019). This is especially relevant in the selected study region of Pakistan’s Punjab, where a substantial amount of the population engages in farming and agro-pastoral activities (Ishaq & Memon, Citation2016). The analysis of this study revealed climate vulnerabilities for both gender (men and women) and this was also indicated in world literature that climate change has gender differentiated vulnerabilities and impacts on communities (Babugura, Citation2010; Dankelman et al., Citation2008; Goh, Citation2012; Gurung et al., Citation2010; Habib et al., Citation2022; Morchain et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the rain-fed context not only in Pakistan but across all Africa and Asia presenting this great diversity of environmental changes (Dasgupta et al., Citation2014). A diverse nature of biodiversity, topography and erratic nature of rainfall patterns brings more frequent events of floods and drought, with serious consequences on ecosystem, agricultural productivity, and social relations (IPCC, Citation2007). Finding about climatic trends identified in the selected study region that include increases in temperature and hailstorm are similar with M. A. Khan et al. (Citation2011) study. Unpredicted and uncertain nature of rainfall patterns are currently the biggest challenge to resistance and adaptation in the study area and past literature also mentioned this challenge as hurdle for sustainable livelihoods (Ashok & Sasikala, Citation2012; W. Khan et al., Citation2017; Tanzina et al., Citation2019).

The results of the study that revealed that men and women have diverse interventions and knowledge base in response of mitigating impact of climatic vulnerabilities in study area further strengthening the available knowledge on similar studies of climate change adjustment capabilities with gender lens in world literature (Carr, Citation2008; Hemani, Citation2015; Ishaq & Memon, Citation2016; Jacobs, Citation2008). Additionally, gender wise access and control over resources in minimizing the climatic hazards side effects was affected by social and political norms of the society among smallholders’ households, particularly for those who were headed by women head. In fact, in adaptation toward climate change impact’s women role was relatively low due to Pakistan’ social, cultural and political norms. Instead of these facts, in study area men and women were in an effort to prove their strength in reducing (Ahmed et al., Citation2016; Alston, Citation2014; Samee et al., Citation2015).

As per discussion presented above women roles and relations in selected sites of the study, women were more vulnerable comparative to their male counterparts in most of the situations when they make effort to minimize the adverse effect of climate change (Arora, Citation2011; Babugura, Citation2010). In medium rainfall zone reduction in income due to natural hazards further accelerate and enhance the vulnerabilities that lead toward severe water scarcity impacted women most vulnerable as they are the prime body to fitch drinking water from spring (Habib et al., Citation2017; Irfan, Citation2007). However, those who settled near to water supplies have better accessibility upon natural resources comparing with those who settled themselves away from these localities. Higher women’s vulnerabilities to climate change were due to their limited access, control and influence over livelihood assets and poor institutional networking and support services (Gautam & Andersen, Citation2016; Skinner, Citation2011).

Previously it was understood that women’s vulnerabilities arise due to lack of their accessibility upon social and natural assets, while this study research added that financial constraints further increase these existing vulnerabilities for women to next level of climatic exposures (Caretta, Citation2014; Lambrou & Piana, Citation2006; Terry, Citation2009). In Pakistan’s set up women are involved in day-to-day cash flows but when larger financial decisions are considered male take dominance. Due to social norms practices women mobility is restricted that leaded to make them blind in understanding early warning systems, as a consequences they are less prepared against any upcoming disaster and face higher loss then men (Caretta, Citation2014; Gautam & Andersen, Citation2016; Skinner, Citation2011). This differentiated treatment of vulnerabilities influenced women lives and livelihoods with stronger impacts (Carr, Citation2008). Major reasons behind are traditional social structures and their dependence upon natural resource-based livelihoods (Arora, Citation2011), and consequently, raising voice for women sensitive vulnerabilities is a decisive step in the direction of focusing women in climate change policies.

5. Limitations of the research

Though we tried our effort to include multiple localities and careful selections of key respondents to evaluate livelihood allocation, but several limitations are notable during the course of study. First, interviews were conducted with limited subset of the population and may not have captured all type of livelihood vulnerabilities. Second, the interviews were conducted with rural male and female of farming communities who were with low level of formal education, so all the information was gathered, based on their memory. Therefore, there is a possibility of errors regarding their recalling capacity. Lastly, study was affected by COVID-19 pandemic, the original plan was for individual semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions between the investigator and participants face-to-face. Before starting this plan, travel restrictions came into place in Australia and Pakistan, which threatened the progress of the study. Face-to-face interviews were viewed as the best way to gain the rapport and trust necessary to uncover as much as possible about the unexplored men and women’s’ livelihood vulnerabilities in Pakistan. We felt that to explore the role deeply, we also needed to assess body language and other non-verbal cues and that face-to-face interviews were necessary to capture this important additional information, which can be at risk of being missed using online data collection methods. However, the possibility of Skype, zoom and telephonic interviews was built into the study design for completion this planned research study.

6. Concluding comments

This study analyzed the gender differentiated climate change related vulnerabilities for men and women. From explored findings of the study, it can be concluded that asymmetrical gender relations, gender division of work, social norms, restricted women’s mobility and less access and control over resources, opportunity and poor decision-making power still make women disproportionately marginalized and powerless in comparison to men rural rain-fed region of Pakistan’s Punjab. Coupled with these social factors climatic variations are reinforcing these inequalities in rain-fed area of Punjab. Rise in temperature, erratic rainfall and drought are the main hazards in study region. However, impacts and vulnerabilities due to these hazards on low and medium rain fall zones are high, and women stand on the frontline of these vulnerabilities. Women vulnerability to climate change is comparatively higher than men as they are directly exposed toward climate change impacts with their higher participation in farming activities. Women resilience to bear climate change impacts is limited due to limited access to livelihood resources and awareness. Based on study analysis following are the few important policy recommendation; (1) it is vital to make sure that men and women are equally contributing and benefiting from climate change related policies; (2) women role can be enhanced in non-farm livelihood sector, this can be done by local government to provide them opportunities such as by supporting and financing them for cottage industries; and (3) finally, to expand women’s livelihoods and brace adaptation by warranting women’s control, access and rights toward livelihood resources can bring sustainable and improved livelihoods outcome for the households in general and for women in specifically.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nusrat Habib

Nusrat Habib, is a Ph.D. candidate in The University of Queensland, Australia. Nusrat has previously 10 years of working experience as a Social Scientist/Agricultural Economist in the field of applied economics in Pakistan Agricultural Research Council which is a national level organization working in the country. She has completed her M.Phil. Applied Economics and MSc. Economic degrees from Pakistan. Additionally, she has more than 30 research publications on her record. Her areas of interest are applied economics, climate change, livelihoods and gender.

Notes

1. Fog is a common phenomenon in plains of Punjab which is formulated by surface conditions such as high level of pollution. Fog is considered as serious hazard for Pakistan’s Punjab during winter season. As with changing climate pattern, winter season is become and intense and resultant in several kind of impacts on rural livelihoods (Habib, Citation2021)

References

- Adger, W. N. (1999). Social vulnerability to climate change and extremes in coastal Vietnam. World Development, 27(2), 249–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00136-3

- Aguilar, L. (2009). Women and climate change: Vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities. World Watch Institute, 59 (80), 10–29 .

- Ahmed, A., Lawson, E. T., Mensah, A., Gordon, C., & Padgham, J. (2016). Adaptation to climate change or non-climatic stressors in semi-arid regions? Evidence of gender differentiation in three agrarian districts of Ghana. Environmental Development, 20, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2016.08.002

- Alston, M. (2014). Gender mainstreaming and climate change. Women’s Studies International Forum, 47, 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.01.016

- Arora, J. S. (2011). Virtue and vulnerability: Discourses on women, gender and climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang, 21(2), 744–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.005

- Ashok, K. R., & Sasikala, C. (2012). Farmers’ vulnerability to rainfall variability and technology adoption in rain-fed tank irrigated agriculture. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 25(2), 267–278.

- Babugura, A. (2010). Gender and climate change: South Africa case study. Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Southern Africa.

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–559.

- Bennett, E. (2005). Gender, fisheries, and development. Marine Policy, 29(5), 451–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2004.07.003

- Bhadwal, S., Sharma, G., Gorti, G., & Sen, S. (2019). Livelihoods, gender and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas. Environmental Development, 31, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2019.04.008

- Biemans, H., Siderius, C., Lutz, A. F., Nepal, S., Ahmad, B., Hassan, T., von Bloh, W., Wijngaard, R. R., Wester, P., Shrestha, A. B., & Immerzeel, W. W. (2019). Importance of snow and glacier meltwater for agriculture on the Indo-Gangetic plain. Nature Sustainability, 2(7), 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0305-3

- Birkmann, J. E. (2013). Measuring vulnerability to natural hazards (2d ed.). United National University Press.

- Blaikie, N. (2009). Designing social research. Polity.

- Caretta, M. A. (2014). Credit plus’ microcredit schemes: A key to women’s adaptive capacity. Climate and Development, 6(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.886990

- Carr, E. R. (2008). Men’s crops and women’s crops: The importance of gender to the understanding of agricultural and development outcomes in Ghana’s central region. World Development, 36(5), 900–915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.05.009

- Creswell, J. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Dankelman, I., Alam, K., Ahmed, W. B., Gueye, Y. D., Fatema, N., & R, M.-K. (2008). Gender, climate change and human security lessons from Bangladesh, Ghana and Senegal. Report prepared by The Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) with ABANTU for Development in Ghana, ActionAid Bangladesh, and ENDA in Senegal.

- Dasgupta, P., Morton, J. F., Dodman, D., Karapinar, B., F. Meza, F., & Riverra-Ferre, M. G. (2014). Rural areas. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, & K. J. Mach (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, part A: Global and sectoral aspects, contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 613–657). Cambridge University Press.

- Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research thousand (pp. 1–32). Sage.

- DFID. (1999). Department for international development. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets.

- Gautam, Y., & Andersen, P. (2016). Rural livelihood diversification and household well-being: insights from Humla, Nepal. Journal of Rural Studies, 44, 239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.02.001

- Gelo, O., Braakmann, D., & Benetka, G. (2008). Quantitative and qualitative research: Beyond the debate. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 42(3), 266–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-008-9078-3

- Goh, A. H. X. (2012). A literature review of the gender differentiated impacts of climate change on women’s and men’s assets and well-being in developing countries (CAPRi Working Paper No. 106). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- GOP. (2018). Economic survey of Pakistan. Government of Pakistan. Pakistan bureau of statistics, ministry of finance.

- GOP. (2020). Economic survey of Pakistan. Government of Pakistan.Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Finance.

- Gurung, G. B., Pradhananga, D., Karmacharya, J., Subedi, A., Gurung, K., & Shrestha, S. (2010). Impacts of climate change: Voices of the people. Practical Action.

- Habib, N. (2021). Climate change, livelihoods and gender dynamics of mountainous communities in Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 37(4), 1269–1279. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2021/37.4.1269.1279

- Habib, N., Alauddin, M., Cramb, R., & Rankin, P. (2022). A differential analysis for men and women’s determinants of livelihood diversification in rural rain-fed region of Pakistan: An ordered logit model (OLOGIT) approach. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 5(1), 100257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2022.100257

- Habib, N., Anwar, M. Z., Zubair, A., & Hashmi, N. (2017). Impact of floods on livelihoods and vulnerability of natural resource dependent communities in Northern areas of Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 5(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2017.0502.0026

- Habib, N., & Muhammad, Z. A. (2014). An analysis of socioeconomic profile of rural sugarcane farmers in district Muzaffar Garh, Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 2(1), 191–199.

- Habib, N., Muhammad, Z. A., Sobia, N., & Tariq, H. T. (2015). Identification of local climate change adaptation strategies for water management in districts Attock and Chakwal, Pakistan. Science Technology and Development, 34(4), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.3923/std.2015.255.259

- Hemani, C. (2015). Approaches to climate change adaptation of vulnerable coastal communities of India. In Handbook of climate change Adaptation (pp. 1521–1568). Springer.

- Hewitt, K. (1983). Interpretations of calamity from the viewpoint of human ecology. Programme.

- Hewitt, K. (2005). The Karakoram anomaly? Glacier expansion and the “elevation effect,” Karakoram Himalaya. Mountain Research and Development, 25(4), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2005)025[0332:TKAGEA]2.0.CO;2

- Hussain, S. S. (2010). Food security and climate change assessment in Pakistan. Special Program on Food Security and Climate Change.

- Hussain, S. S., & Mudasser, M. (2007). Prospects for wheat production under changing climate in mountain areas of Pakistan–an econometric analysis. Agric. Syst, 94(2), 494–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2006.12.001

- IPCC. (2007). Climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Working group II contribution to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press.

- Irfan, M. (2007). Poverty and Natural resource management in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review. The Pakistan Development Review 46 (4II), 691–708.https://doi.org/10.30541/v46i4IIpp.691-708

- Ishaq, W., & Memon, S. Q. (2016). Roles of women in agriculture: A case study of rural Lahore, Pakistan. Journal of Rural Development and Agriculture, 1(1), 1–11.

- Jacobs, S. (2008). Its discontents: gender, liberalization, and collectivization: Lund University Libraries. J. Work. Rights, (13), 17–39.

- Jost, C., Kyazze, F., Naab, J., Neelormi, S., Kinyangi, J., Zougmore, R., … Kristjanson, P. (2015). Understanding gender dimensions of agriculture and climate change in smallholder farming communities. Climate and Development, 8(2), 1–12.

- Khan. (2002). Pothwar’s Agricultural Potential. Pakistan Agriculture Overview. Daily Dawn.

- Khan, M. A., Hussain, A., Mehmood, I., & S, H. (2011). Vulnerability to climate change: Adaptation strategies and layers of resilience in semi-arid zones of Pakistan. Pak J Agric Res, 24(1–4), 65–74.

- Khan, W., Tabassum, S., & Ansari, S. A. (2017). Can diversification of livelihood sources increase income of farm households ? A case study in Uttar Pradesh. Agriculture Economics Research Review, 30(conf), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-0279.2017.00019.2

- Krauss, S. (2005). Research paradigms and meaning making: A primer. The Qualitative Report, 10(4), 758–770.

- Lambrou, Y., & Laub, R. (2004). Gender perspectives on the conventions on biodiversity, climate change and desertification: United Nations. Gender and Population Division

- Lambrou, Y., & Piana, G. (2006). Gender: The missing component of the response to climate change: FAO.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Meinander, M. (2009). Livelihood sustainability analysis of the floating villages of the tonle sap lake. Perspectives from Three Case Studies. Helsinki University of Technology.

- Morchain, D., Prati, G., Kelsey, F., & Ravon, L. (2015). What if gender became an essential, standard element of vulnerability assessments?. Gender and Development, 23(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2015.1096620

- Muhammad, Z. A., Waheed, C., & Nusrat, H. (2016). Changing rainfed agriculture: An empirical analysis of pothwar region of Punjab, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Life and Social Sciences, 14(2), 70–76.

- Naheed, Z., Nadeem, A., Nusrat, H., Saima, R., Mubashira, N., & Irum, R. (2017). Impact of climate change hostilities on livelihood strategies: A case study of rainfed pothwar area of Pakistan. Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences, 7(11), 138–143.

- Okali, C., & Naess, L. O. (2013). Making sense of gender, climate change and agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa: Creating gender-responsive climate adaptation policy (WP 057). Future Agricultures Consortium, IDS.

- Samee, D., Nosheen, F., Khan, N. H., Khowaja, A. I., Jamali, K., Paracha, I. P., & Khanum, Z. (2015). Women in agriculture in Pakistan. FAO, Issue.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson Education.

- Siddiqua, A., Munir, A., & Nusrat, H. (2019). Farmers’ adaptation strategies to combat climate change impacts on wheat crop in Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research, 32(2), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjar/2019/32.2.218.228

- Skinner, E. (2011). Gender and climate change: Overview report. Bridge.

- Sultana, F. (2010). Living in hazardous waterscapes: Gendered vulnerabilities and experiences of floods and disasters. Environmental Hazards, 9(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.2010.SI02

- Tanzina, D., Dwijen, M. M., U, P. B., Chanda, G. G., Anjal, P., Ganesh, G., & Atiq, R. (2019). Growing social vulnerability in the river basins: Evidence from The Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) Region. Environmental Development, 31, 19–33 doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2018.12.004.

- Terry, G. (2009). No climate justice without gender justice: An overview of the issues. Gender & Development, 17(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070802696839

- Van, A., Cannon, M. K. T., & Burton, I. (2008). Community level adaptation to climate change: The potential role of participatory community risk assessment. Glob. Environ. Chang, 18(1), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.06.002

- Wisner, B., Blaikie, P., Cannon, T., & Davis, I. (2003). At Risk natural hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters. Routledge.

- Wymann von Dach, S., Bachmann, F., Alcántara-Ayala, I., Fuchs, S., Keiler, M., & Mishra, A., eds. (2017). Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern, Switzerland.