?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

As one of the most youthful populations in the world, with close to 80% of its population under the age of 30, Uganda is grappling with initiatives for engaging youth in productive sectors of the economy. Agriculture is considered the most immediate means of catalyzing economic growth and employment for the youth. The Self-Help Groups (SHGs) Model is preferred by both government and non-government agencies to organize youth to engage in agriculture because it takes into account the critical socio-economic elements. The challenge is how to ensure the sustainability of the SHGs for the progressive transformation of the youth. This article assesses the likelihood forof the sustainability of youth groups engaged in agricultural enterprises, based on the parameters of group sustainability specified by the Producer Organization Sustainability Assessment Model. The study employed a quantitative design using a cross-sectional survey conducted between Government and Non-Governmeagency agenciesagencies supported Self Help Groups. In the study, Non-Government Supported groups were more likely to be sustainable than the Government supported groups. The main contributors to sustainability among the Non-Government supported groups were access to production resources, financial health, and member loyalty, while the main contributors for the Government supported groups were leadership, financial health, and member loyalty.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Globally, the majority of the youth are unemployed. As a result, both Government and Non-Government agencies are concerned about this phenomenon and are taking initiatives to create opportunities for youth engagement in gainful employment. The agricultural sector remains the highest potential to absorb the growing youthful labor force compared to the service and industry sectors of the economy. Because agriculture is characterized by smallholder farming, the Self-Help Groups (SHGs) Model is preferred to organize the youth to engage in agriculture. The challenge is sustaining the SHGs for the gainful employment of the youth. From this background, the researchers investigated the likelihood of the sustainability of the groups. Findings showed that the non-government-supported groups were more likely to be sustainable than the government-supported groups. In the end, appropriate recommendations have been forwarded in this paper.

1. Introduction

The youth unemployment rate in Uganda is pervasive, comprising 83% of the total unemployed (Alfonsi et al., Citation2020). Both Government and Non-Government agencies are concerned about this phenomenon and are taking initiatives to create youth engagement in gainful employment. Agriculture though already employing the majority of Ugandans, retains the highest potential to absorb the burgeoning youthful labor force (Aryeetey et al., Citation2021) compared to other sectors of the economy. Given that agriculture in Uganda is characterized by smallholder farming, the Self-Help Groups (SHGs) Model is preferred by the development agencies to organize the youth to engage in agriculture because it considers the critical socio-economic elements.

The concept of SHGs is widely applied in development initiatives by both Government and Non-Government agencies, especially in addressing socio-economic challenges of society (Nayak et al., Citation2019), including unemployment for the youth and poverty eradication programs for socially disadvantaged categories of society. Examples cited to have worked well include micro-credit and women SHGs in Bangladesh (Mathur & Agarwal, Citation2017), poverty eradication initiatives targeting women in India, and poor men and unemployed youths in many countries (Mathur & Agarwal, Citation2017). However, the challenge is how to sustain the SHGs for the progressive transformation of the beneficiaries, yet it has been equally challenging to study the sustainability of such groups.

The sustainability of youth groups refers to the ability of such groups to endure to carry out various project activities and maintain the processes after the end of the external intervention (Nation & Of The U, Citation2014). Youth groups have become an essential tool for socio-economic development that fosters youth empowerment, livelihood strengthening, and poverty alleviation (USAID, Citation2019). Government interventions such as the Youth Livelihood Program implemented by the Ministry of Gender, Labor, and Social Development (MoGLSD); and Non-Government agencies use groups to engage the youth in economic activities to create self-employment. Sustainability, however, does not just emerge after the interventions; it has to be inherent in the intervention design, taking into account all the factors that might affect the transition to the self-reliance of groups.

Youth groups set a foundation for development by instilling in young people a spirit of mutual help, building solidarity, motivating joint responsibility to take actioning solidarity and motivating collective responsibility to take actioning solidarity, and boosting common commitment to change their status quo. Youth SHGs inspire the pursuit of group enterprises, mobilization of savings, offer group collateral for accessing formal credit facilities (Goyette et al., Citation2016), and ease access to other services such as advisory services and markets. Evidence shows that group-based participatory programs are an effective strategy for sustainably fighting against poverty (Akanksha & Patnaik, Citation2021). However, this is only possible if the groups can adapt and cope with challenges for a long time or even evolve and inspire creativity to address the members’ emerging economic and social needs.

The sustainability of Self-Help Groups (SHGs) is a dominant challenge worldwide (Kumar, Citation2019). Youth SHGs experience various constraints that hinder them from achieving their set objectives and after impact sustainability. Such constraints are related but not limited to lack of funds and financial management; internal and external politics; bureaucracies in accessing resources for youth enterprises, governance of the youth groups and youth programs; lack of technical support and capacity building; conflict management; and resource mobilization capacity (Vasantha, Citation2014).

At the time of this study, over 34 Million US Dollars had been disbursed to 16,169 youth SHGs as loans by the Government of Uganda through the YLP to support youth projects in four years, but only 1.3% of the youth groups had repaid 100% of the loans. The NGOs also channel their support to youth through SHGs. The more significant concern is drawn to the fact that most beneficiary youth groups disintegrated in the first three years (Mwesigwa & Mubangizi, Citation2019). It is acknowledged that very few youth groups and their projects are sustained beyond the intervention, whether by Government or non- Government actors (MoGLSD, Citation2018). However, development interventions rely on groups as the primary organizing principle. Whereas the use of SHGs is reported to have been successful elsewhere, particularly in Asia, in transforming disadvantaged categories of societies like the youth, it may not be replicated in Uganda based on the concerns for the sustainability of such groups.

The objective of the study, therefore, was to assess the likelihood for the sustainability of youth groups in mid-Western Uganda, based on the parameters of group sustainability specified in the Producer Organization Sustainability Assessment Model (POSA). Specifically, the key research question is: to what extent do the existing youth groups under the YLP and NGO initiatives score on the sustainability parameters established in the POSA model? The assumption is that if the scores on sustainability parameters are insufficient, the groups are unlikely to be sustainable after the intervention programs end.

2. Literature review

A sustainability program must begin with explicit knowledge of the “sustainable concept” (Ruggerio, Citation2021). Although the essence of the concept of sustainability is clear, how it is defined in practice is still subjective (Purvis et al., Citation2019). The term “sustainable” comes from the Latin word “subtenir,” which means “to hold up” or “to support from below.” In Kazakhstan, the primary funding source for youth group activities is through social contracting with the government (Bhanot et al., Citation2021). These social contracts tend to be short-term and do not help the youth groups to implement long-term programs. Only a small number of youth groups in 2009 received state funding, and the process is not transparent (Bhanot et al., Citation2021). Kazakhstan’s youth groups also receive funding from international organizations, mainly providing grants for the implementation of social projects (Bhanot et al., Citation2021).

Youth groups’ long-term sustainability and financial autonomy depend on their ability to internally generate funds and negotiate long-term national and international contracts (Bendjebbar & Fouilleux, Citation2022). Youth groups are also faced with governance and management challenges. Governance is defined as the relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of organizations (Pincock et al., Citation2021). Nasrallah and El Khoury (Citation2022), highlight that sound organizational governance and management practices are essential for organizations to improve their impacts over time. The question of governance, mainly the reasons for creating a board of directors, is rarely practiced by youth groups (Erwin, Citation2022). Such boards might appear only on paper and lack decision-making authority. Competent boards, working in conjunction with the senior management would help youth groups develop the vision and strategies that create the innovation needed for long-term viability and sustainability (Alfawaire & Atan, Citation2021).

2.1. Conceptual framework

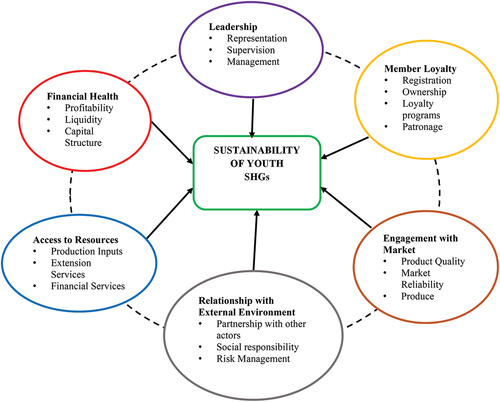

Sustainability may have diverse meanings and is applied differently in environmental and development literature. According to Pezzey (Citation2017), the term “sustainability” has two connotations; first, it includes the maintenance of the environment and human well-being; and second, it means the durability of a given Government over time and its resilience to perturbation. In the context of this study, sustainability refers to the ability of the youth groups to continue functioning over a period of time and being able to strike a balance between having good relations with each other, financially gaining from the group activities, and maintaining the environment irrespective of the challenges faced. This study applies the Producer Organization Sustainability Assessment Model (USAID-Uganda Producer Organizations Activity, Citation2019) to determine the likelihood of sustainability of youth SHGs under the YLP program in mid-western Uganda. The sustainability assessment model is designed to guide groups and organizations in undertaking periodic self-assessments to; gauge/predict their progress towards sustainability, identify and prioritize gaps that need to be addressed for the group to gradually grow into a mature and sustainable collective business.

The model also guides in choices of external intervention for capacity strengthening support; structure partnership dialogue between the group and the implementing agency; and can also be used as a program monitoring, management, and decision-making model. Whereas POSA is a comprehensive model, it has been used more in guiding development intervention, and yet it is also an analytical tool. In this study, it is used as an analytical model to inform the status of the existing youth SHGs in Mid-Western Uganda based on the key parameters for group sustainability. The current status of the groups is a predictor of the eventual sustainability and highlights areas for improvement towards the desired sustainability.

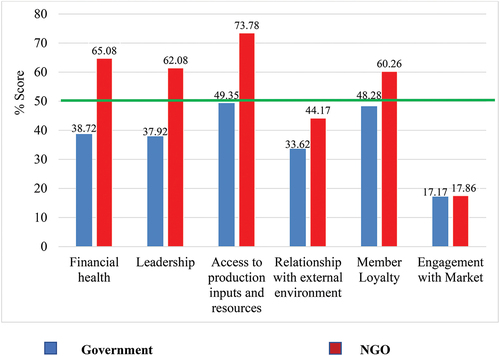

The POSA model is composed of six priority sustainability parameters for any group as illustrated in figure . These are Financial Health; Engagement with the Market; Access to production inputs and services; Relationship with the external environment; and Member loyalty. Each parameter is decomposed into sub-elements and specific indicators. The respective indicators are assigned weighted scores based on their contribution to sustainability. An overall sustainability score is calculated as a fraction of a maximum aggregate score of 100.

Figure 1. Sustainability conceptual framework (adapted from USAID,Citation2019).

This conceptualization of sustainability is informed by Moekle (Citation2012) theory of Sustainability, which according to (Gladwin, Kennelly, & Krause, Citation1995) is multidimensional and extends beyond environmental protection to economic development and social equity. It seeks to strike a balance between the economy—the business world view, the Society—humanistic view, and the environmentalist view. It is argued in this theory that sustainable groups ought to not only create profitable enterprises but also achieve certain environmental and/or social objectives. The combination of profitability, environmental concerns, and social benefits perfectly fit the purposes and intentions of the youth agricultural SHGs studied. Agricultural enterprises rely on natural resources making the aspect of environmental sustainability critical to continued profitability and societal social benefits. For this reason, the (Moekle, Citation2012) theory of sustainability reinforces the relevance of the POSA model. The sustainability of business groups that rely on natural resources stretches beyond the alternative European Corporate Sustainability Framework (ECSF) which emphasizes Effectiveness, Efficiency, creativity, and Flexibility (Hardjono & de Klein, Citation2004).

3. Methodology

3.1. Study design

The study employed a quantitative design using a cross-sectional survey conducted in April 2018. A cross-sectional survey allows comparison across groups to explore whether there are differences in sustainability between the Government and Non-Government agency support SHGs (Nichols, Citation2021).

The study was conducted in Hoima and Masindi districts located in mid-western Uganda. The two districts were selected because of the rapid urbanization due to the recent discovery of oil in the region and how the youth respond to such opportunities by producing food and other agricultural products. Whereas the oil industry is likely to provide job opportunities for some youth, most youth would have to strategically engage in agriculture to supply the growing food demands of the large population that the oil industry and related businesses will attract.

The study targeted youth groups (supported by both Government and Non-Government agencies) registered at the district level. Ideally, all community development groups, including youth groups, must register with the District Community Development Officer (CDO). In this regard, the two districts’ CDOs provided the lists of youth groups with agricultural activities supported by the Government YLP program and NGOs. These were the sampling frame for the selection of the study groups. The CDO provided 722 youth groups (289 and 433 from Hoima and Masindi, respectively) with their contacts. The Uakarn (Citation2021) formula (below) was used to calculate the sample size.

Where:

s = required sample size.

X2 = the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841).

N = the population size.

P = the population proportion (assumed to be 50 to provide the maximum sample size).

d = the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (05).

Using the above formula, a sample size of 110 youth groups was obtained. For each district, the list of youth groups provided was (with the aid of the CDOs) clustered into two: those supported by a Government agency (YLP) and those supported by Non-Government agencies. The district CDO also has a record of support agencies for the registered groups. The proportionate to size method (n/N) was then used to determine the number of youths drawn from each category (Table ) to enable comparison. Whereas 110 youth groups were targeted, only 107 youth groups were traceable, hence the accessible sample.

Table 1. Number of youth groups sampled

3.2. Sample selection

Systematic sampling procedure using the steps outlined below was used to select the groups studied:

Step 1: Arrange the names of youth groups (from each district) in the two categories (Government or Non-Government supported) in alphabetical order and number the arranged list starting from 1.

Step 2: Computation of the sample fraction (k) calculated by dividing the population (N) by the total number of groups (n) in each category (k = N/n). For example, for the first category in table 4.1, k=722/158 = 5

Step 3: A number was then selected between 0 and k to formulate the sampling basis. Following the above example, since k=5, the chosen number would be between 0 and 5.

Step 4: Groups that are represented by numbers between 0 and n that add k to the selected number are identified. For example, if our selected number is 4, and k is 5, the numbers selected are 4, 9 (4+5), 14 (9+5), 19 (14+5), and so on. The process is repeated until n is reached.

Step 5: Locate the groups on the sampling frame that corresponds to the calculated numbers drawn above, and these groups will constitute the sample.

3.3. Data collection

Data were collected from the 107 selected youth groups using a semi-structured questionnaire to measure the specific items under each of the six parameters: Financial Health, Leadership, Engagement with Market, Member Loyalty, Relationship with External Environment, and Access to production inputs and resources. Each item was weighed on the scorecard (see Appendix 6). A pre-test of the instrument was performed among ten youth groups in Kampala to establish suitability and reliability. Based on the pre-test results, some questions were adjusted for simplicity and understanding (by the respondents) and, in some cases, re-arranged for logical flow while maintaining the original content. Table presents the items in each parameter and how they were measured. For each of the selected groups, a team of 2–4 representatives was interviewed together for consensus that best represents the group’s status on the individual items measured.

Table 2. Items used to measure the sustainability of youth SHGs

3.4. Data analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) version 21 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics (Means, Percentages) were generated to characterize the youth groups based on the items measured. Sustainability assessment using Producers’ Organization Sustainability Assessment tool (POSA). The tool, developed by ILRI and partners within the EADD project (Munyaneza, Citation2018), has six dimensions that cover production and business/marketing aspects. Each dimension comprises basic sub-dimensions, and each sub-dimension is also an aggregation of measurable indicators. The Producer Organization Sustainability Assessment Model (POSA) developed the scorecard that provides cut-off scores for each of the parameters to indicate their overall contribution to sustainability. These scores were applied to generate the percentage contribution of each indicator to sustainability (USAID, Citation2019). Further, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to establish the critical determinants for sustainability among the Government and Non-Government supported groups.

4. Results and discussion

First, the characteristics of the groups studied are discussed concerning group composition, experience, functions of the group, and key enterprises. Second, the six parameters of the POSA model are independently discussed, and their contributions to the sustainability of the group. Third, the differences in sustainability for the Government and NGO-supported groups are discussed.

4.1. Characteristics of the groups studied

A summary of the characteristics of the groups is presented in Table . The majority of the groups have been in existence for at least three years on average (3.7 and 3.2 years for the Government and NGO supported groups, respectively). It would be expected that at this period of existence, the groups should be exhibiting signs of sustainability as they maneuver through group development dynamics to stability and performance levels (Munyaneza, Citation2018). It is also noted (based on the CDOs’ opinions) that most of the Government-supported youth groups came into existence starting in 2013 when the government of Uganda launched the YLP.

Table 3. Group characteristics

The groups that the government supported were smaller in membership than those supported by Non-Government agencies. The reason is that the Government-supported groups under the YLP were restricted to a maximum membership of 15, while the Non-Government supported agencies did not have such restrictions. Whereas the average size of the Government-supported youth groups was 13, the NGO-supported groups had an average of 30 members making the two categories significantly different in membership.

4.2. Functions of the groups

Whereas all the groups studied were involved in agriculture, they had several specific objectives for their existence. Table summarizes the reasons for the formation as articulated by the groups’ representatives. It is important to note that each group had several reasons/objectives for their establishment.

Table 4. Main reason for group formation

There is a difference in orientation (by reason for existence) between the Government and NGO-supported groups, as shown in Table 4.4. The majority of the government-supported groups (75%) were established with the primary objective of accessing credit from the YLP, followed by access to information and advice related to their enterprises of choice. Most (47%) of the NGO-supported youth groups were established with the primary objective of accessing information and advice on their enterprises, followed by access to inputs (27%) and socialization (12%). Only 11% of the NGOs supported groups specified access to credit as a critical function of the groups.

Both the Government and NGO-supported groups essentially seek empowerment but through different pathways. The government-supported groups seek empowerment through credit, while the NGO-supported groups essentially seek empowerment through enhanced production facilitated by knowledge/information and inputs.

4.3. Choices of agricultural enterprises for the youth

There is a difference in the types of enterprises that the Government and NGO-supported groups engage in (Table ). Whereas the NGO supported groups tend to engage more in crop production, mainly grains and cereals (such as maize and rice); fruits and vegetables (such as cabbage, tomatoes, hot pepper, and passion fruits); and piggery; the Government-supported groups focused more on livestock (bull fattening, piggery, and poultry). The focus on livestock by the Government-supported groups is influenced by prioritizing the YLP program based on location. The Government supported groups were restricted in terms of choice of enterprises, priorities were pre-determined by the YLP; while the NGOs did not impose any preference for enterprises, groups made their own independent choices.

Table 5. Agricultural enterprise for the youth

Interest, experience, and what the youth see as the potential are precursors for success in a particular enterprise and, ultimately, the group’s sustainability. The difference in enterprises between the two categories of groups points to governance issues whether the youth groups have space and freedom to analyze their environment and make informed choices of their preferred enterprises or that their priorities are pre-determined for them. It can be attributed that where the youth groups have no freedom to make independent choices of their enterprises, such groups may not continue with the enterprise when the external support ends. The groups would not have a solid motivation to build the elements of sustainability in their operations.

4.4. Group scores on the sustainability parameters

The six parameters of the POSA model have independent contributions to the sustainability of the group. The overall scores on the sustainability parameters are presented before discussing the individual contributions of the parameters.

The POSA model specifies a 50% average score as the cut-off for sustainability for each parameter. figure shows that the NGO-supported groups score above the sustainability mark for four out of the six parameters (USAID, Citation2019). In contrast, none of the government-supported groups is below the sustainability mark for all the parameters. The NGO-supported groups score below the sustainability mark on the parameters of relationship with the external environment and engagement with markets. If this trend continues, there is a likelihood for the sustainability of the NGO-supported groups (if the two parameters of relationships with the external environment and engagement with markets are enhanced), unlike the Government-supported groups. With this picture, the contributions of individual parameters to this overall view are discussed.

4.5. Group leadership

According to the model, a sustainable group is dependent on having dependable leaders and how those leaders perform their core functions that enable cohesion and ownership of the group by its members (USAID, Citation2019). Among the essential leaders that a group should have been the chairperson, vice-chairperson, secretary, treasurer, and patron/mentor/elder. The minimum functions expected of these leaders are to supervise group activities, perform internal checks for finance management, and ensure compliance with agreed procurement procedures and performance appraisals. Table presents the assessment results of the leadership parameter based on whether the groups had the respective leaders.

Table 6. Presence of group leaders

Nearly all the groups had the expected leaders except for the patron/mentor. More than half of the groups supported by the NGOs had patrons/mentors compared to only 4% of the Government-supported youth groups. As a good practice, the NGOs encourage the groups to have a mentor/patron, which is not emphasized by the Government-supported programs. A patron’s role is critical in ensuring cohesion and conflict resolution, providing guidance and motivation to the group. The roles played by the patron and treasurer make a big difference in the sustainability score for leadership between the Government and NGO-supported youth groups. Among the leaders, the females comprised 42.1% and 36.9% respectively in the Government and NGO supported groups. The inclusion of female leaders indicates a general consciousness of gender inclusivity. In part, this could be influenced by the long-term gender advocacy and national guidelines that require 30% minimum representation by women at various levels of leadership, starting from the village level councils to representation in parliament (Local Government Act, Citation1997; Uganda Gender Policy (UGP), Citation2007).

One of the leaders’ key roles is to organize regular meetings, including annual general meetings, and ensure group compliance to agreed rules and regulations. The minimum consideration was at least an annual general meeting. In this regard, 29.8% and 70% of the groups supported by the Government and NGOs respectively organized regular Annual General Meetings (AGM) in which they elected new leaders or renewed their mandates; discussed financial matters including their financial obligations; annual work plans, and budgets, and resolving conflicts that might have emerged. This implies that it is not just enough to have leaders, but the quality of leaders is critical to the extent that they understand their responsibilities and perform them diligently. In this regard, Most of the NGO-supported groups had leaders that executed their duties as compared to under 30% of the Government supported groups that did the same.

As explained in chapter 2, the NGOs focused more on capacity building of the groups, including building leadership capabilities, unlike the Government programs. Leadership qualities are more common in NGO-supported groups than in government-supported groups. All groups set rules and regulations (Table ).

Table 7. Group rules and regulations set

The leaders’ role was to ensure that the group members complied. In cases where they defaulted, 42.6% and 83.3% of the Government and Non-Government supported groups respectively enforced punitive actions such as suspension and expulsion, shaming, and levying a fine. Leaders also carried out performance appraisals (34% by Government and 68.3% Non-Government supported) that primarily focused on compliance with group rules.

4.6. Financial health

Financial health is the group’s capacity to generate sufficient and reliable revenue to finance short, medium, and long-term financial obligations, in response to the group’s needs (Roesch et al., Citation2021). Financial health was measured by the profitability of group enterprises, liquidity ratio, and capital structure (Roesch et al., Citation2021). Both Government and NGO-supported groups, to some extent, acquired some capital from their respective support agencies but to differing levels, as evidenced by their capital structure. The Government-supported groups received capital mainly as credit/loans from the YLP, which lowered their capital structure to 13.8%. At the same time, most of the NGO-supported groups acquired capital in kind, for example, farm inputs (such as seed, fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides), and a score of 85.8% on capital structure.

On the one hand, after acquiring the credit, the Government supported groups often shared the money between the group members to invest in individual rather than group enterprises. In this case, it appears most groups did not have a clear group plan for a joint business, and the groups served as a mechanism for the acquisition of a credit. Ironically this credit was expected to be paid by the group and not individuals. On the other hand, the NGO-supported groups undertook group enterprise before receiving the in-kind capital support. The capital was intended to enhance the performance of the group enterprise.

Calculation of profitability of groups revealed that 28.7% and 47.6% of the groups supported by Government and NGOs respectively made profits in the previous year. All groups had a development orientation in their objectives, reflecting the members’ interests to improve their livelihoods through incomes generated from the group activities. It should also be remembered that the overall goal of engaging youth in agriculture is to create gainful employment. In this regard, profits are critical to the members’ sustained interest and relevance. The group’s relevance to the membership is in itself a driver for sustainability. Wadell (Citation2001) emphasizes that adequate financing and financial prudence are essential ingredients in the sustainability of youth enterprises. Failure to make profits, which was more prevalent among the Government-supported youth groups, diminishes members’ commitment. Both Government and NGO-supported groups exhibited a high liquidity ratio of 93.62% and 96.67%, respectively (Zorn et al., Citation2018).

The provision of capital is fundamental to empowering youth in groups, although how the capital is provided matters (capitalization for government and capacitation for NGO supported). The lack of mentors/patrons (table 4.6) for the Government-supported youth groups coupled with limited supervision made such groups more vulnerable to inappropriate investment strategies that do not guarantee group benefits. The better performance of the NGO-supported youth groups on the financial health parameter can be in part due to guidance and support from the mentors/patrons. The mentors/patrons are usually successful people in society who have relevant experience and can appropriately guide the young people to, among other things, make logical and thoughtful decisions (Zorn et al., Citation2018).

4.7. Member loyalty

Member loyalty is the dedication members have towards participating in group activities and ensuring that they achieve their objectives. Member loyalty was measured by patronage, ownership, loyalty programs, and payment of membership or registration fees (Dary & Grashuis, Citation2021). Only 51.1% of the Government supported groups charged a membership (registration) fee compared to 86.7% of the NGO-supported groups. Payment of membership fees indicates a dedication to the group and legitimacy. Ownership, also known as collective action, was measured by the number of members who volunteered to do group activities (Feinberg et al., Citation2021). Results indicate that 36.2% and 48.3% of Government and NGO-supported group members, respectively, participated in group activities. The low score for ownership negatively affects groups’ sustainability since a few members feel all members share overworked yet benefits.

Patronage is the support (both financial and in-kind) received by the groups to enable them to carry out their activities (Rubio-Arostegui & Villarroya, Citation2021). Government and Non-Government supported groups scored 65.9% and 73.3%, respectively. All the groups received support from several initiatives engaging youth in agriculture. This implies that the groups will likely be sustainable if the trend continues in that direction.

Olson’s theory of groups is the glue that binds groups together (Willy & Ngare, Citation2021). Loyalty programs (social support such as labor pooling burial support in case of loss of a loved one) were established within groups to promote cohesion. Mutual support activities enhance group loyalty, such as labor pooling arrangements, member saving schemes, and supporting members when they lose close relatives. These social and mutual support systems motivate the members to want to remain a member of the group and increase the group’s social cohesion (Wenocur et al., Citation2021). Government and NGO-supported groups scored 63.8% and 81.7% respectively on loyalty. The scores can be matched with socializing as an objective for establishing the groups. More of the NGO-supported groups expressed this as their objective than the Government supported groups (Table 4.4). Therefore, it can be argued that in addition to economic benefits, the extent to which a group addresses the social interactions and mutual support among its members contributes to the chances of sustainability of the youth groups.

4.8. Access to production inputs and resources

The Production inputs used by youth groups engaged in agricultural enterprises were land, labor, fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and livestock feeds(Snyder, Citation2021). The resources for utilization of these inputs included extension services to guide the proper use of the inputs information and financial services to enable the acquisition of the inputs. Land, which is one of the main factors of production, was commonly acquired free of charge (40.2%), by renting (47.7%), inheritance (2.8%), and purchase (2.8%). 85% of the groups mobilized labor from group members to minimize costs, while 16.8% hired labor.

The utilization of the inputs is enhanced by the support services such as extension and financial services(Bahn et al., Citation2021). The Government programs, namely the YLP, focused on providing financial support (cash loans) and minimal advisory services and their score on this element was only 49.3%. Conversely, the NGOs attempted to integrate extension services in their capacity-building support, and the score for such groups was 73.78%. A good balance of enabling groups to access production resources and support services is more likely to enhance sustainability than just focusing on either of the two(Bahn et al., Citation2021).

4.9. Relationship with Externalxternal Environment

A relationship with the external environment is the group’s ability to harness relationships with other actors. This was measured by the groups’ ability to work with other actors; social cooperate responsibility, environmental sustainability, and risk management(Valackienė & Nagaj, Citation2021). A majority of the groups only worked with their respective supporting agencies with minimal effort to partner with other actors such as NGOs, Farmer Organizations, Financial Institutions, and Private sector partners such as seed companies. As a result, the support received by the groups was mainly from the supporting agencies. In case of withdrawal of such support, the group has no fallback position to continue with the services they have been getting, and hence, sustainability is not guaranteed. On this parameter, Government and NGO-supported groups scored 46.2% and 56.67%, respectively.

Social cooperate responsibility was measured by the activities the group engages in to offer a service to the community in which they existed. Social cooperate responsibility programs are established to create a bond and working relationship within the community and promote goodwill from other people who are not group members(Valackienė & Nagaj, Citation2021). It is also a form of visibility of the group within the community. Groups with such initiatives often attract guidance and counsel from external members, enhancing the group’s sustainability. On this parameter, both Government and NGO-supported groups scored 8.5% and 45.0%, respectively. Whereas both scores are below the sustainability mark, the score by the Government supported groups indicates that the concept of social cooperate responsibility is yet to be appreciated and or understood, while the supported groups are moving close to the sustainability mark on this parameter.

Risk management was measured by the group’s ability to avert risks and possession of a risk management plan. Although the groups were aware of the most frequent risks faced, such as weather variability, theft, price fluctuations, pests, and diseases, 87.9% did not plan to avert such risks. The inability of a group to prevent possible risks indicates a high level of vulnerability to these risks, and the likelihood to continue existing when such risks occur is low(Musacchio et al., Citation2021).

4.10. Engagement with the market

The primary goal of the youth enterprises was to generate income and thereby making engagement with markets inevitable(Cieslik et al., Citation2021). Engagement with the market is reflected in market reliability, product quality, and productivity. Market reliability was measured by contractual obligations to supply some products and whether they met the client’s requirements as stipulated in the contracts. Only 2.8% of the groups supported by NGO initiatives had a contract to supply to the markets, but even these could not meet the stipulated requirements. The groups sold their produce at the farm gate, relying on local traders (75% government and 61% NGO supported) who came to buy it. The buyers largely determined the prices, and the group members did not influence the prices.

Irrespective of several groups being located in the same area and engaging in similar enterprises, there was no evidence of the collective purchase of inputs and marketing of products. Each group engaged in the input-output markets independently.

About 60% of the government and 78% of the NGO-supported groups reported that they were not satisfied with the prices offered for their products, which does not favor the groups’ objective of generating income and subsequently affects sustainability as the member expectations are not satisfactorily met. This behavior deprives the groups of benefiting from economies of scale, including accessing more lucrative and contract markets. Their primary source of market information was radio, peers, and telephone correspondence.

All aspects of sustainability need to be strengthened among the Government-supported groups, implying that interventions aimed at engaging youth in agriculture ought to consider all the parameters if they are to attain sustainability and their intended goal of engaging youth in agriculture as a means of gainful employment (Khalid et al., Citation2021).

4.11. Critical contributors for sustainability of youth groups

A Varimax Rotated Principal Component Analysis was used to establish the contribution of the items measuring the parameters for the sustainability of youth groups with the absolute value set at 0.5. As indicated in Tables and ix.

Table 8. Contribution of elements to group sustainability among government-supported groups

Results in Table indicate that the likelihood of youth groups being sustainable mainly depended on their leadership, particularly group management and supervision among the Government supported groups. In contrast, Table reveals that the likelihood of sustainability mainly depended on access to production inputs and resources, extension, and financial services among the non-government-supported groups. Youth groups that received extension services were believed to have more technical support and guidance on managing their enterprises. They were more likely to be sustainable than their counterparts who did not have access to extension services. Surprisingly, relationships with other actors and engagement with the markets did not contribute much to the likelihood of sustainable youth groups. This is attributed to the fact that there was no price differentiation in most markets concerning the quality of produce. Nonetheless, financial health, particularly profitability (proportion of profit to sales) and capital structure (Proportion of debt Used to finance the enterprise), contributed largely to the likelihood of a group to be or not to be sustainable. The component loadings revealed the items that contributed the most, while the value showed the magnitude of contribution on each item to the likelihood of the youth groups’ sustainability.

Table 9. Contribution of elements to group sustainability among NGO supported groups

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Based on the discussions above, the study concludes that the NGO-supported groups were more likely to be sustainable than the Government supported groups. The study demonstrates that the main contributors to sustainability among the Government supported groups were leadership, financial health, and member loyalty, while the main contributors to sustainability among the Non-Government supported groups were access to production resources, financial health, and member loyalty.

Efforts towards enhancing the sustainability of youth groups need to support them in strengthening their leadership, particularly management and supervision for the government-supported groups. NGO-funded initiatives should support the youth groups with the provision of production inputs and resources, especially extension services. Thus, merging the government and non-government initiatives will promote Public and Private Partnerships, and in turn ensure sustainability through comprehensive support to the youth groups.

Furthermore, findings showed that all support is channeled through self-help groups, and as such, youth are expected to organize themselves in groups to access the support. However, little attention is paid to the group formation process and the group dynamics therein. This study, therefore, recommends that further research is conducted on the formation process and group dynamics.

AcknowledgementsAcknowledgments

I am grateful to my research team for their thoughts on the conceptualization and write-up of this paper. Other colleagues at the Department of Extension and Innovation Studies at Makerere University have been generous as always with comments and suggestions about youth and agriculture and Governance. Finally, I would like to acknowledge all the initiatives and youth who took part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dorcas Elizabeth Loga

Loga Dorcas Elizabeth completed her first degree in Agribusiness Management, Masters Degree in Agricultural Extension Education, and is Pursuing her PhD in Agricultural and Rural Innovations of Makerere University, Uganda. She is currently a grants officer with the Agriculture Cluster Development Project (ACDP) of the Ministry of Agriculture Animal Industry and Fisheries, where she builds the capacity of Farmer Organizations and facilitates the award of Matching Grants, where an understanding of sustainability of groups hence farmer organizations is key. Before this appointment, Dorcas held the position of Grants Manager for the SHARE Intra ACP Mobility Scheme hosted in the Department of Extension and Innovation Studies Makerere University. In addition, she has a wealth of expertise with over 12 years experience in management and administration of European Union, Intra – Africa, Caribbean, Pacific, EDULINK and World Bank grants. She is passionate about managing and facilitating multi stakeholder projects aimed at building efficient partnerships for sustainable innovations development.

References

- MoGLSD. (2007). Uganda National Gender Policy. MoGLSD, Kampala.

- Akanksha, & Patnaik, H. (2021). Gender and participation in community-based adaptation: Evidence from the decentralized climate funds project in Senegal. World Development, 142, 105448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105448

- Alfawaire, F., & Atan, T. (2021). The effect of strategic human resource and knowledge management on sustainable competitive advantages at Jordanian Universities: The mediating role of organizational innovation. Sustainability, 13(15), 8445. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158445

- Alfonsi, L., Bandiera, O., Bassi, V., Burgess, R., Rasul, I., Sulaiman, M., & Vitali, A. (2020). Tackling youth unemployment: Evidence from a labor market experiment in Uganda. Econometrica, 88(6), 2369–23. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA15959

- Aryeetey, E., Baffour, P. T., & Turkson, F. E. (2021). Employment creation potential, labor skills requirements, and skill gaps for young people: Ghana case study. July.

- Bahn, R. A., Yehya, A. A. K., & Zurayk, R. (2021). Digitalization for sustainable agri-food systems: potential, status, and risks for the MENA region. Sustainability, 13(6), 3223. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063223

- Bendjebbar, P., & Fouilleux, E. (2022). Exploring national trajectories of organic agriculture in Africa. Comparing Benin and Uganda. Journal of Rural Studies, 89, 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.11.012

- Bhanot, S. P., Crost, B., Leight, J., Mvukiyehe, E., & Yedgenov, B. (2021). Can community service grants foster social and economic integration for youth? A randomized trial in Kazakhstan. Journal of Development Economics, 153, 102718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102718

- Cieslik, K., Barford, A., & Vira, B. (2021). Young people not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) in Sub-Saharan Africa: Sustainable development target 8.6 missed and reset. Journal of Youth Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1939287

- Dary, S. K., & Grashuis, J. (2021). Characterization of farmer‐based cooperative societies in the upper west region of Ghana. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 92(4), 669–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12305

- Erwin, A. (2022). Connecting food justice to farmworkers through a faith-based organization. Journal of Rural Studies, 89, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.10.009

- Feinberg, A., Hooijschuur, E., Hooijschuur, E., Ghorbani, A., & Herder, P. (2021). Sustaining collective action in urban community gardens. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation, 24(3). https://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.4506

- Gladwin, T. N., Kennelly, J. J., & Krause, T. S. (1995). Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable Development: Implications for Management Theory and Research. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 874–907. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9512280024

- Goyette, M., Mann-Feder, V., Turcotte, D., & Grenier, S. (2016). Youth empowerment and engagement: An analysis of support practices in the youth protection system in Quebec. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 74(263), 31–49.

- Hardjono, T., & de Klein, P. (2004). Introduction on the European Corporate Sustainability Framework (ECSF). Journal of Business Ethics, 55(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-1894-x

- Khalid, A. M., Sharma, S., & Dubey, A. K. (2021). Concerns of developing countries and the sustainable development goals: The case for India. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 28(4), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2020.1795744

- Kumar, N. A. (2019). Self-help groups in India: Challenges and a roadmap for sustainability. In P. P. Kumar Ed., Social responsibility journal: Volahead-of-p (Issue ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-02-2019-0054

- Mathur, P., & Agarwal, P. (2017). Self-help groups: A seed for intrinsic empowerment of Indian rural women. Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion: An International Journal, 36(2), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-05-2016-0039

- Moekle, K. R. (2012). THE RHETORIC OF SUSTAINABILITY. Teaching Sustainability/Teaching Sustainably, 76 https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Moekle%2C+K.+R.+%282012%29.+THE+RHETORIC+OF+SUSTAINABILITY.+Teaching+Sustainability%2FTeaching+Sustainably%2C+76.&btnG=.

- MoGLSD. (2018). Youth Livelihood Programme (YLP) compendium of Programme Success Stories, 1(August).

- Munyaneza, C. (2018). Assessing sustainability of smallholder dairy and traditional cattle milk production systems in Tanzania. A Thesis Submitted In Fulfillment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Of Sokoine University Of Agriculture.

- Musacchio, A., Andrade, L., O’Neill, E., Re, V., O’Dwyer, J., & Hynds, P. D. (2021). Planning for the health impacts of climate change: Flooding, private groundwater contamination, and waterborne infection – A cross-sectional study of risk perception, experience, and behaviors in the Republic of Ireland. Environmental Research, 194, 110707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.110707

- Mwesigwa, D., Mubangizi, B. (2019). Contributions of the Youth Livelihood Programme (YLP) To Youth Empowerment in Hoima District, Uganda. International Journal of Business and Management Studies, 11(1), 54–71.

- Nasrallah, N., & El Khoury, R. (2022). Is corporate governance a good predictor of SMEs financial performance? Evidence from developing countries (the case of Lebanon). Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 12(1), 13–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2021.1874213

- Nation, F., & Of The U, A. O. (2014). Youth and Agriculture. In The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in collaboration with the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD. 17.

- Nayak, A. K., Panigrahi, P. K., & Swain, B. (2019). Self-help groups in India: Challenges and a roadmap for sustainability. Social Responsibility Journal, 16(7), 1013–1033. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-02-2019-0054

- Nichols, C. (2021). Self-help groups as platforms for development: The role of social capital. World Development, 146, 105575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105575

- Pezzey, J. C. (2017). Sustainability constraints versus” optimality” versus intertemporal concern, and axioms versus data. The Economics of Sustainability, 73(4), 263.

- Pincock, K., Betts, A., & Easton-Calabria, E. (2021). The rhetoric and reality of localisation: Refugee-Led organisations in humanitarian governance. The Journal of Development Studies, 57(5), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1802010

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

- Republic of Uganda. (1997). Local Governments Act 1997. 235.

- Roesch, A., Nyfeler-Brunner, A., & Gaillard, G. (2021). Sustainability assessment of farms using SALCAsustain methodology. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, 1392–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.02.022

- Rubio-Arostegui, J. A., & Villarroya, A. (2021). Patronage as a way out of crisis? the case of major cultural institutions in Spain. Cultural Trends, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2021.1986670

- Ruggerio, C. A. (2021). Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. Science of the Total Environment, 786, 147481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147481

- Snyder, A. (2021). Modern agriculture and its impact on smallholder farmer livelihoods. In Handbook on the Human Impact of Agriculture (pp. 163–178). Edward Elgar Publishing.https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839101748.00020

- Uakarn, C. (2021). Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran and krejcie and Morgan and green formulas and Cohen statistical power analysis by G*Power and Comparisons. Apheit International Journal, 76–88.

- USAID, (2019). USAID-Uganda producer organizations activity. July.

- Valackienė, A., & Nagaj, R. (2021). Shared taxonomy for the implementation of responsible innovation approach in industrial ecosystems. Sustainability, 13(17), 9901. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179901

- Vasantha, S. (2014). Challenges of self-help group members towards income generation activity International Journal of Accounting and Financial Management Research . 4(2), 1–8.

- Wadell, S. (2001). Engaging in youth Employment and Livelihood: bridging the divides. New York: Organization Future Inc.

- Wenocur, K., Page, A. P., Wampole, D., Radis, B., Masin-Moyer, M., & Crocetto, J. (2021). PLEASE be with me: benefits of a peer-led supervision group for early career social work educators. Social Work with Groups, 44(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2020.1836548

- Willy, D. K., & Ngare, L. W. (2021). Analysis of participation in collective action initiatives for addressing unilateral agri-environmental externalities. Environmental Science & Policy, 117, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.12.013

- Zorn, A., Esteves, M., Baur, I., & Lips, M. Financial ratios as indicators of economic sustainability: A quantitative analysis for Swiss dairy farms. (2018). Sustainability, 10(8), 2942. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10(8. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082942