Abstract

What does it mean to grow older? This paper explored this question through discourse analysis. Life course and interpretive perspectives provided a theoretical framework for the study. Semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of 23 participants provided data on their aging experience which were analyzed as a discourse. Initial analysis identified four narrative frames: accumulated age, experience and wisdom; changed social status; onset of health problems; and increased likelihood of death. Further analysis introduced two contrasting discursive subjects of “powerful seniors” and “declining elders-ambiguous ancestors”. The results show that aging leads to a powerful social status of elderhood and seniority, on one hand, while overtime, it results in decline and ambiguity in one's social relations. The findings are discussed in light of global and local discourses on aging and elderhood. Whereas on one hand social anthropologists construct elders as agents of influence who constitute a bridge between the past and the future, on the other hand, medical science and public health construct older adults as sick, weak, and dependent subjects whose place is in respite and long-term care facilities. Clearly, discourses on aging are particular ways of speaking to and about older adults and serve as surveillance on everyday practice—individual behavior and collective responses toward the elderly. It is recommended that, to the best of their abilities, older adults be engaged in peace building and dispute resolution efforts, child protection and child rearing decision-making, community problem solving, and the teaching of history from experience. It is also recommended that older adults be given income and housing assistance as well as increased access to affordable healthcare services to attenuate decline and loss.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper presents and discusses findings of a study that explored the meaning of aging – growing older – from the viewpoints of older adults in Ghana. Interviews were conducted with participants who described their understanding of aging and their experiences with growing older. According to participants, on one hand, growing older means becoming a powerful senior or elder who has influence and an enhanced social status in the family and community; on the other hand, aging means becoming frail and weak, and moving toward death. These findings are of interest to aging scholars and policy analysts. The paper builds on social science and cultural perspectives on aging, and provides aging scholars, policy analysts and professionals a unique understanding of what aging means from the viewpoints of older Ghanaians.

1. Introduction

The population of older adults in Africa, as globally, is increasing. The United Nations (Citation2019) has indicated that by 2050 nearly 17% of the world<apos;>s population will be over the age of 65. The projection is that by 2050, the population of people aged over 65 years will be more than twice that of children under five years (United Nations, Citation2019). Older adults in Africa are defined as those aged 60 years and above (He et al., Citation2020; Help Age International, Citation2008). He et al. (Citation2020) have estimated that between 2020 and 2050, the population of older adults in Africa will triple from 74.4 million to 235.1 million. The general trend of increase in the population of older adults on the African continent is reflected locally in Ghana. In 2021, older adults constituted approximately 2 million (6.5%) of Ghana<apos;>s population of 30.9 million (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2021) and is projected to hit a 6.3 million mark by 2050 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2013). As a significant demographic group, concerns about older adults in Ghana have become a key policy focus since Ghana participated in and made commitments at the Second World Assembly on Aging in 2002 (Government of Ghana, Citation2010).

This paper explores what growing older means in contemporary Ghana, using discursive repertoires of older adults. Although research on aging in Ghana has grown in scope over the past five decades (De-graft Aikins et al., Citation2016), studies that purposefully explore the question: “what does growing older (or aging) mean to elderly Ghanaians?” are in short supply. Existing research has highlighted the changing socio-demographic profile of older Ghanaians (Kpessa-Whyte, Citation2018; Tawiah, Citation2011) and described the health, housing, and income challenges faced by the elderly, with obvious female-male and rural-urban disparities (Aboderin, Citation2004; Ayernor, Citation2012, Citation2016; Issahaku & Neysmith, Citation2013; Kuuire et al., Citation2017; Kwankye, Citation2013; Minicuci et al., Citation2014). Studies have observed that a high proportion of older Ghanaians live in poverty and lack housing and access to quality health care. Connected to this, as traditional care systems have weakened (Aboderin, Citation2004), Coe (Citation2016, Citation2017) has reflected on what is described as “the commodification of eldercare in urban Ghana”. In Coe<apos;>s (2016, 2017) work, older people in urban Ghana are a dependent population because they need care. But their children do not have the time to provide care. Therefore, eldercare becomes a commercial service which is purchased by those who can afford it. In contrast, Drah (Citation2014) and Atobrah (Citation2016) have highlighted the important role of older women as caregivers, using the example of elderly women who care for orphans and other vulnerable children as entry points. Drahs (Citation2014) and Atobrahs (Citation2016) studies show that, in some significant ways, older adults play an important socialization role in the community. Another important addition to the literature is from Van der Geests (Citation2002, Citation2004) work in Kwahu-Tafo. In some qualitative detail, Van der Geest (Citation2004) describes the feelings of loneliness and lack of respect expressed by older adults in the rural Akan community. Perhaps for the loneliness and lack of respect, some of Van der Geests (Citation2002) participants indicated that they preferred to die. Each of these works offers something unique about older adults in Ghana. However, no recent study has directly posed the question of what growing older means to the current generation of older adults in Ghana, neither has any study explored this question using discourse analysis.

The goal of this paper, therefore, is to revisit an apparently old but relevant question: What does it mean to grow older? How do older adults speak about the aging experience? As times and traditions have changed in Ghana (Nukunya, Citation2003), which change has introduced new ways of being and relating, perhaps there is something new to learn or something unique to reemphasize through a revisiting of this question and by exploring it through the lenses of older Ghanaians as participants in a discourse. Discourses are constructions and interpretations of social experience, drawing from scientific knowledge and from cultural assumptions, beliefs, and practice, and are produced and circulated by members of a cultural group. For poststructuralist scholars (e.g., Foucault, Citation1972), discourses create the objects of whom they speak and are the focal ways in which a culture produces and circulates beliefs and practices that instill discipline and guide individual behavior and social interactions. The current study therefore uses discourse analysis to explore how older adults in Ghana construct and interpret their aging experience and to situate findings within global and local aging discourses. This approach ensures that an insider<apos;>s perspective, as opposed to an outsider<apos;>s view, is brought to bear on what growing older means. In this paper, I use the terms aging and growing older interchangeably. Similarly, elder, elderly, and older adult are substitute terms.

2. Theoretical perspective and research approach

Two complementary perspectives that inform the work in this paper are the interpretive perspective (Marshall et al., Citation2016; Schutz, Citation1967; Wilson, Citation1970) and the life course framework (Cattell & Albert, Citation2009; Elder, Citation1995, Citation1995; Garbarino, Citation1985; Giele & Elder, Citation1998; Mayer, Citation2009; Runyan, Citation1982; Sokolovsky, Citation2009) both of which draw from traditions of phenomenology and symbolic interactionism (Marshall et al., Citation2016). In gerontology, the goal of the interpretive-micro lens is to highlight the unique ways in which individuals make sense of their lives and experiences and how they create and inhabit particular social identities (Breytspraak, Citation1984; Clarke, Citation2009; Gubrium, Citation1975; Marshall et al., Citation2016). The interpretive perspective holds that social life is interactional and that interpretations people give to their lives and experiences evolve and change over time and cross-culturally. People construct and interpret their realities drawing from knowledge in current circulation, past experience, and every day social interactions. To this effect, Gubrium (cited in Marshall et al., Citation2016, p. 386) has explained that “social reality is constructed through ongoing, negotiative, and definitional behavior” and that we can see people actively defining and negotiating their realities in everyday discourse. The interpretive perspective complements the broader life course perspective (Cattell & Albert, Citation2009; Elder, 1980; Elder, Citation1995; Garbarino, Citation1985; Giele & Elder, Citation1998; Mayer, Citation2009; Runyan, Citation1982; Sokolovsky, Citation2009) on aging to explore the social construction of meaning and reality in everyday life and in cross-cultural contexts. The life course perspective studies lives in context and in motion and lives as linked (Cattell & Albert, Citation2009; Elder, 1980; Elder, Citation1995; Sokolovsky, Citation2009). The framework helps to understand how people make sense of the age-graded social passages they go through in their unique cultural contexts (Sokolovsky, Citation2009). According to Sokolovsky (Citation2009), as people navigate the cultural contexts of community, family, gender, and work over the life span, they graduate from adulthood to elderhood through to possibly becoming ancestors. Available empirical literature demonstrates how the life course model follows people as they journey in life to explore what realities individuals construct for their lives and what events and experiences (such as social roles, critical incidents, and historical events) shape these realities (see Moller & Sotshongaye, Citation2002; Oakley, Citation2002; Rosenberg, Citation2009; Sagner, Citation2002; Van der Geest, Citation2002, Citation2004).

The life course and interpretive perspectives support a discourse analysis approach to research on aging. Discourse is understood as a social performance in relation to a subject matter using language (Wood & Kroger, Citation2000). Wetherell (Citation1998) has noted that discourse analysis not only attends to the unique ways in which agents employ discursive repertoires in specific situations, but also pays attention to the social contexts that inform such appropriation. According to McMullen (Citation2011, p. 205), discourse analysis has been used “as a method of analysis; a methodology; a perspective on social life that involves metatheoretical, theoretical, and analytic principles … ” The method lends itself to the analysis of both primary data (transcribed interviews or written responses) and “naturalistic” data (existing textual, audio and visual materials) and enables the researcher to focus on one or more dimensions of the data (McMullen, Citation2011; Potter, Citation2004; Willig, Citation2003; Wood & Kroger, Citation2000). Discourse analysis also enables researchers to pay attention to what knowledge claims are made by participants and how these claims corroborate or contradict what is known already (Wood & Kroger, Citation2000). Important concepts in discourse analysis include positioning of the self, narrative structure, and ideological dilemmas, while key strategies for analysis include reframing, focusing, and sensitivity “to multiple functions and variability” in participants’ accounts (McMullen, Citation2011, p. 208). Talking about what growing older entails constitutes a discourse on aging in which participants are invited to engage. This approach is a unique way to generate additional literature on aging and older adults in Ghana.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Twenty-three older adults were purposively sampled from the Northern and Greater Accra Regions for the study. Personal outreach and purposive sampling (Singleton & Straits, Citation2005) allowed for the inclusion of participants who were typical of the elderly population. The sample included men and women, older adults from rural and urban areas, individuals of varied levels of formal/nonformal education, and older adults who had pursued varied occupations during their active years. The sample also captured older adults belonging to different ethnic or tribal groups. Table presents characteristics of the sample.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

3.2. Data collection

Semi-structured interviewing was the method of data collection for the study. The author conducted face-to-face interviews with participants at mutually agreed locations, and used an audio recorder to capture and transcribe the data. The interviews explored the focal question: what does it mean to say one is aging or growing older? Sub-questions explored included what participants are excited about with the aging experience and what their fears are about growing older. All except four interviews were conducted in English. The four interviews were in a local language—Dagbanli—that is widely spoken in northern Ghana. (Dagbanli is the author<apos;>s mother tongue.) The interviews ranged from 35 min to 45 min in duration. Each participant provided consent either verbal or written. Memorial University of Newfoundland<apos;>s Interdisciplinary Committee on Ethics in Human Research (ICEHR) provided ethics approval for the study (ICEHR # 20,171,397-SW).

3.3. Data analysis

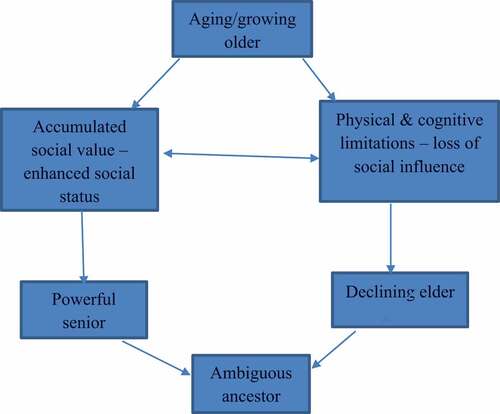

I analyzed the data following steps and strategies for analyzing discourse outlined in the literature. I gained familiarity with what participants were saying and how they were saying it by reading the transcripts repeatedly and making notes of key messages. I paid attention to the multiple ways in which participants spoke of the aging phenomenon and the differences and similarities in their accounts, and stayed closer to their explanations and interpretations. I used open and axial coding to identify and outline patterns of meaning in the emerging discourse, as shown in Table . Drawing from the existing literature and from my familiarity with the cultural context of the study, I engaged in further interrogation of the data by focusing on literal and implied meanings in participants’ utterances, and made judgments on what concepts would serve as heuristics for the emerging themes. This aided in reducing the data to main themes that constituted the discourse on aging as displayed in .

Table 2. Discourse on aging: Coding of data on what aging means

4. Findings

Consistent with the tone of discourse, the data revealed subject positioning by participants (e.g., aging persons as experienced, wise, weak or strong people), narrative structure in participants’ utterances (e.g., comparative analysis, use of folklore), and dilemmas (e.g., about changing physiological functions and social status). As presented here, the themes of “powerful senior” and “declining elder-ambiguous ancestor” emerged as the contrasting components of the discourse on aging among participants. Participants who are quoted to illustrate these themes are referenced by age and gender.

4.1. Powerful senior

The theme of powerful senior emerged as a significant component of the aging discourse. Characteristics of the powerful senior included a sense of accumulated social value, enhanced social status, and changed expectations and responsibilities. These experiences, in the discursive frames of participants, are intrinsic to aging and bring seniority and social power. As many as fifteen participants underscored that longevity brings experience, knowledge, wisdom and strength of character all of which in unique ways make one a powerful senior member of society. The powerful senior narrative on aging among participants is illustrated in the passages below, with references to some of the participants. One participant argued that:

If you hear that somebody is growing older, the first thing that comes into the mind is your age, it is very, very important … And, it comes with experience. Once you are aging you pass through life situations and by that you acquire more knowledge and then with that experience you have wisdom. (Male, 61 years).

Some participants held that the aging experience makes one better understand events/issues so you can proffer solutions; you become a problem solver. According to participants, one who survives beyond the reproductive years has knowledge and wisdom from experience, and qualifies to give advice, make decisions, and preside over customary rites. For example:

When a person says he is growing older, then life is becoming very interesting for you. Because he sees himself above so many things that have happened before which the young ones are doing, and he feels he could do better. Secondly, seeing the mistakes of the young ones, he can see that he too, some time ago, had also gone into that and says, ‘if I had known I should have done this. Because now that I’m growing older, I have solutions to so many of them’. (Male, 63 years).

Notably, male participants were predominant among those who constructed the powerful senior as wise and knowledgeable who gives advice, makes decisions, and presides over ceremonies. One participant used folklore to buttress the point as follows:

A boy once asked his elderly father, ‘father, what is special about growing older’? The father sat him down and told the following story. “There was a young man understudying an elderly native doctor. One day the native doctor asked the young man to go bring a live vulture for a ritual. Confused, the young man asked: ‘how on earth can I catch a live vulture’? The elder smiled and, tapping the young man, said, ‘don’t worry, I will tell you what to do. Go to the open field, lie down face up, pretend to be dead, and watch what happens’. The young man did as was told and soon vultures started hovering over the spot. The first to come was a 100-year old vulture who said: ‘I have seen many vultures captured because they went close to a suspicious carcass like this one’. Then it went away. The second was a 75-year old vulture who said: ‘some of my friends have been captured because they went to eat a suspicious carcass like this one’. Then it went away. The third vulture was 25 years old and it said: ‘Aha! This is booty on a silver platter’. Then it landed by the side of the young man to eat. Can you guess what happened to it? What an elder can see while sitting down, a young man cannot see even if he climbs an oak tree”. (Male, 68 years).

Further to the above, in as many as ten transcripts, participants posited that part of the agency of the powerful senior is care and nurturance of children and general responsibility for family and community well-being. They were of the view that, as one grows older and children and grandchildren come, your priorities, roles and responsibilities change, and others change their expectations of you. As a result, your status in the family/community changes from merely a member to an elder who wields power and influence. Female more than male participants emphasized the care and nurturance role of the powerful senior. Some of the accounts are as follows:

Growing old is a blessing from God. To grow old is a blessing from God. For me I will be happy if I can live more than 100 years. I will be happy in the sense that I can look after my grandchildren. (Female, 74 years).

Growing older, you experience a change in your life. Old age is characterized by the presence of children, sometimes many of them in your life. For this reason, your plans change. You become a parent, a grandparent. (Female, 60 years).

Another participant, building on this understanding of the powerful senior, indicated that it came with some stress:

So, if you go on retirement and your children are still in the basic school then you will think more. Paying school fees and some petty, petty things will be needed for the children. If you go on retirement and you have to provide all these things you will think more and that will make you have headache; your pressure too will go up. (Female, 61 years).

Emphasis on responsibility for the general well-being of family and community came more from male participants. To illustrate, one participant had the following to say:

Growing older, for me, your attitude and your behavior and other things change. Your movement and code of dressing also change. You cannot dress like when you were young and growing up. You know, other generations look up to you. So, your dress code should be different from that of the younger generation. When you have children in the house, they must pick up some of these things from you. (Male, 69 years).

Another participant, drawing from memory, made the following submission:

When we were growing up as children, there was no older person except the one who was the head of the clan [extended family]. This is the person everybody paid homage to. Everybody would gather at his house for anything you want to do. Even eating; your wives will cook, and you will all bring the food to the elder’s house to eat together. We rallied around the elder in the family. (Male, 78 years).

Corroborating this view, another participant had this to say:

Growing older, you are becoming mature, you are now an elderly person. Yes, so you can be called a mature person. Like currently, with my current age, I’m now the family head. I am now the family head and for that matter, I will even find it very difficult to leave the family house [a house where many generations live together]. This is because, in fact, the people we are handling in this house, they are many. So, I am thinking that if I leave the family will disintegrate. (Male, 67 years).

4.2. Declining elder-ambiguous ancestor

In the emerging discourse, the process that ushers the aging subject into a powerful senior also transforms one into a declining elder-ambiguous ancestor. The decline and ambiguity of elders result from debility and disease, and a progression toward death. According to one participant, as one grows older, you not only accumulate years and other social values, you also accumulate “ill-health, sometimes protracted illness” (Male, 63 years). Thus, subthemes of declining elder-ambiguous ancestor included physical and cognitive limitations, loss of social influence, and increased dependency and proximity to death. Because of physical and cognitive limitations such as loss of strength, inability to work, loss of income, hearing, memory, and vision problems, among others, the elder loses power and influence. Increasingly, the elder becomes weak and dependent, where others have to make care and other decisions for them. Further, decline and ambiguity result from the fact that sicknesses set in or multiply or become protracted, and the elder eventually dies to become an ancestor. One participant explained that:

It [growing older] means you are no longer strong like the first time; you cannot do things as you used to do before. Your energy is less; everything of yours has limits. You cannot go about your work because sicknesses start setting in. You get sicknesses which probably when you were younger you weren’t getting them. Then you become tired with the least work that you do. So, you cannot more make ends meet like the first time. (Female, 63 years).

Other participants—male and female, as illustrated in the following, shared the narrative of decline of elders:

You know, growing old, you change; everything of yours changes. You yourself will get to know that you are aging. Me like this, sometimes I will even be telling my children and they are laughing. I say ‘I didn’t know I was growing old, but now I know. Because when I do small work, I’m tired. The work I used to do so much, now I can’t do it’. So that tells me that, yes, now I know that I’m growing old. And, small, small sicknesses, my knees hurt. (Female, 61 years).

When you are growing older, you can’t be active again. Like, sometimes, my leg will be paining me; if I walk from here to here, small time, I will be tired. (Female, 62 years);

Different people can have different experiences. To me, growing older means advancing in years and getting weaker in strength, getting memory crisis, losing your memory and your body stature. Even your sight, your hearing, may be affected. (Male, 62 years);

The way you used to live, you can no longer live that way. You experience a change in your life … Then you experience a decrease in your mental ability. (Female, 60 years);

Growing older, I will say there are signs and symptoms that will tell you that you are growing older. Because in life if you were able to do certain things and then at a certain time you can’t do those things again, it means you are growing weaker. Growing weaker means you are growing older. Right now, my health condition; I see that I urinate very frequently. In the night, maybe, I urinate about three, sometimes, about four, times before daybreak and I could see that I’m growing older. (Male, 72 years).

Further, on the decline of the elder, participants argued that the elder is in close proximity to death. For the declining elder, there is no argument about the death event; it is rather a question of when death will happen. The proximal nature of death to the elder was captured in one transcript as “ … every day means a shortening of your lifespan” (Female, 60 years) and in another as “Whilst you are born you are growing and then you come to a certain stage which, biologically, you don<apos;>t expect to live forever” (Male, 61 years). The following extracts built on the point:

When you are growing older, there is a proverb in Dagbanli which says that ‘if a leaf is turning yellow, it is going to fall from the tree’. It means you are going towards your death. Yes, growing older means one is getting closer to death. (Male, 65 years).

It [growing older] means a lot to me. I met my mother’s parents, but I didn’t meet my father’s parents; they were gone at old age. When my mother’s parents died, I said, ‘ah! So, one day I will also die’. Not quite long afterwards, in 1982, 5th January, my father died. I said ‘ah! Everybody is now going turn-by-turn. I know one day it will come to my turn’. As I am getting old, I do tell my children, my grandchildren, I say ‘your mother knows my mother, they know your grandmother, where are they? They are gone. In the same way, maybe, one day you will get married and have issue and your children will know me. But one day, you will not see me on earth again’. So, growing older means moving toward the time you will depart from earth. (Female, 71 years).

5. Discussion

Drawing on life course and interpretive perspectives (Elder, 1980, Elder, Citation1995; Makoni & Stroeken, Citation2002; Marshall et al., Citation2016; Sokolovsky, Citation2009), this study explored what growing older signifies from the viewpoints of older Ghanaians as participants in a local discourse on aging. Issahaku (Citation2018, p. 635) has observed that “discourse analysis enables us to engage with texts … in ways that uncover hidden meanings and reveal contrasts, contradictions, and clarifications”. Consonant with this methodological approach (McMullen, Citation2011), data analysis considered the question posed to participants as a form of discourse on aging and the discussion here attempts to make sense of the emerging discourse among participants. As is shown in the findings, “powerful senior” and “declining elder-ambiguous ancestor” constitute the discourse on aging. On the one hand, it constructs the aging subject as one who enters into elderhood (Sokolovsky, Citation2009), a position of seniority and social influence. As social agents, powerful seniors occupy a priority position, exert power and influence, make decisions, or take actions that produce effects. On the other hand, however, the aging elder also experiences decline and ambiguity in social relations. Decline and ambiguity is due to a perceived progressive accumulation of physical, cognitive, and social losses by the elder, a process whose climax is the death event, and a probable transition into ancestorhood.

We can situate the emerging aging discourse among participants within global and local scientific (medical and sociological) knowledge as well as within cultural assumptions and beliefs and practices regarding aging and old age. Significantly, cross-cultural literature on aging (Cattell & Albert, Citation2009; Gurven & Kaplan, Citation2009; Makoni & Stroeken, Citation2002; Sokolovsky, Citation2009) helps us to make sense of the discourse of powerful senior. Sokolovsky (Citation2009) has noted that aging has two dimensions; post reproductive survival and senescence. Postreproductive survival encompasses chronological time (in years) and socially graded rites of passage, which endow one with cultural influence—knowledge and wisdom. Sokolovsky (Citation2009) adds that aging is a process by which people approach “elderhood”, become “ancient”, and possibly attain “ancestorhood”. In line with this, Stroeken (Citation2002) has indicated that, in addition to bodily changes over time, growing older brings a change in “social status, as it is expressed in the social relationships, alliances, offspring … and knowledge that expand the self” (p. 90). We can see, therefore, that the discourse of powerful senior which participants built on notions of accumulated social value—experience, knowledge, and wisdom, which comes with enhanced social status and changed expectations, draws on existing knowledge of the post reproductive stage of life. The values that “expand the self” (Stroeken, Citation2002, p. 90) constitute a key dimension of social capital that society needs for nurturing the young and solving or preventing social problems. To emphasize the influential place of elders, a West African adage says that “what elders see while sitting down, children cannot see if they climb a tree”. In line with this reasoning, the discourse holds that growing older makes one an elder whereby you have the cultural expertise to be an agent of socialization and social control. The narrative corroborates current literature which shows that grandparenting and foster care for vulnerable children (Atobrah, Citation2016; Attar-Schwartz et al., Citation2009; Devine & Earle, 2011; Drah, Citation2014; Mason et al., Citation2007; Patrick & Tomczewski, Citation2007), especially grandmotherhood (Chapman et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Margolis & Wright, Citation2017) is an important component of the social life of many elders. Grandparents make decisions and take actions that have effects on children and, by implication, the future society.

In addition, the powerful senior—as elder—is head of the family and community, and presides over ceremonies, decisions, and disputes. Family elders preside over decisions such as regarding marriage, land tenure, and inheritance rights. They are also healers and in charge of important rituals during funerals, child naming, and coronation of chiefs and kings. In the Ghanaian context, elders mediate conflict and resolve cases of crime in the community. This is particularly so for elders in rural communities. To this effect, one male participant indicated that, as elders, it is their duty to resolve familial and communal conflict and crime, and that it is only when their efforts fail that a matter may go to court. According to him:

Those of us older persons in rural areas act as chiefs and custodians. If you have an issue, you take it to the chief and the elders. If you don’t go to the chief and instead take the matter to court, the chief can summon you and sanction you. (Male, 68 years).

Further, characteristics of the powerful senior in participants’ narratives included the fact that ‘you have learnt from your mistakes and now have solutions to many of life<apos;>s challenges, “people rally around you”, “families will disintegrate if you fail in your obligations”, and “young people must pick up good manners from you”. Similarly, in the story about the young apprentice and the vultures, the native doctor who heals and performs ritual sacrifices is an elder. The findings here corroborate literature which indicates that elders have special powers whereby they are not afraid of physical or spiritual forces; indeed, they have the ability to control these forces (Rosenberg, Citation2009). These points on agency are noted by Stroeken (Citation2002) who argues that “the elder stands for a ‘zone’ within the larger social network of events … Descendants and allied kin-groups define their belonging, distance or proximity in terms of that zone embodied by and emanating from the elder” (p. 90). A gender effect that emerges in the discourse of powerful senior is that older women<apos;>s power is exercised predominantly in the area of grandmotherhood, whereas older men exercise general leadership and social control in the family and community.

However, decline and ambiguity in social relations is part of the aging discourse. In their postreproductive survival stage, elders experience a progressive loss of physical strength, cognitive abilities, and social power, and eventual exit from among the living. One can interpret the discourse of declining elder-ambiguous ancestor in light of existing medical science and public health knowledge as well as participants’ personal experiences and cultural beliefs. Cell biologists, for example Lopez-Otin et al. (Citation2013), define aging as “the time-dependent functional decline that affects most living organisms” (p. 2). According to Lopez-Otin et al. (Citation2013, p. 1), aging is “characterized by a progressive loss of physiological integrity, leading to impaired function and increased vulnerability to death”. Similarly, Cattell and Albert (Citation2009) explain that aging subjects decline into “ancients” or frail elders. Cattell and Albert (Citation2009) note that frail elders may become spiritually influential among humans following their death. The discourse of decline among participants was captured in expressions such as: “I get sicknesses which I did not get before now”; I cannot do the work I used to do’; “I walk a short distance, I get tired and my leg pains”; “my knees hurt”; and “I urinate frequently which disrupts my sleep at night”. This narrative makes much sense when juxtaposed against existing global public health literature on health problems among older adults, especially chronic and non-communicable diseases, and some of the participants are perhaps aware of this literature, especially those who can read and follow health discussion programs on radio or television. Existing cross-national public health literature (Ayernor, Citation2012, Citation2016; Biritwum et al., Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2020; Mini & Thankappan, Citation2017; Mistry et al., Citation2021; Palmer et al., Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2008, Citation2013, Citation2014; Wu et al., Citation2015; Yadav et al., Citation2021) has highlighted the high non-communicable disease burden among older adults, including diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease, among others. Current public health discourse elevates health problems among older adults to a crisis level and recommends actions that affect older adults. Some of the participants demonstrated awareness of the crisis as they monitor health discussions on radio and TV. According to one participant:

I have been listening to radio or TV; they bring somebody on health digest. They discuss some of the sicknesses we see within ourselves. They will discuss diabetes and this urinal problem. They also talk about prostate cancer and other issues. So, when you sit down by the radio or TV and you listen, you will get to understand what is happening to you. (Male, 72 years).

The discourse of decline of elders is supported by other studies on aging in Africa. For example, in a study by Ferreira and Makoni (Citation2002), participants described how they become forgetful (e.g., difficulty remembering names or where they have hidden money), have difficulty recognizing relatives, and easily get lost in the community. Perhaps connected to these health problems, the elder loses social influence and the ability to earn income, thereby, experiencing poverty and disrespect. A male participant (68 years) made the point as follows: “ … For instance, as I sit here, I would have been on the farm working by now. But if I get up to go, my waist pains me. I cannot go”. Poverty brings dependency and disrespect to older adults (Sagner, Citation2002; van der Geest, Citation1997; Zelalem & Kotecho, Citation2020). Sagner (Citation2002) quotes a participant as saying that:

We as old people are not treated the way we should be treated. We are treated like people who are not supposed to live. A perfect example are those people in the public service, they are so rude to us when we go to collect our pension money (p. 48).

Consistent with the point made two decades ago, a recent survey among gerontology scholars in sub-Saharan Africa found that poverty, food insecurity, and dependency were top challenges among older adults (Adamek et al., Citation2022).

There is little wonder that declining elders are in close proximity to death. The discourse that the end of senescence is death has a basis in participants’ cultural beliefs and personal experiences with their own elders. Participants know and believe that the illnesses and loss of abilities that come with aging bring one to the end-of-life in the physical. Culturally, only the death of elders is considered normal or natural, and their death is celebrated with pump and pageantry. As suggested by one participant, a declining elder becomes the proverbial green leaf that turns yellow and eventually falls off. Participants also know this first-hand. As one indicated, her parents and grandparents died in old age and she will be joining them as she grows older. In effect, elders do not die; they transition into another life since they will become ancestors (Cattell & Albert, Citation2009; Ephirim-Donkor, Citation2016; Lee & Vaughan, Citation2008; Stroeken, Citation2002; De Witte, Citation2001). For example, among the Dagombas of northern Ghana, when an elder dies, he/she is said to have “joined the ancestors”. The discourse is that, eventually, powerful seniors-declining elders move into that ambiguous state of ancestorhood who the living honor during celebrations and call on to offer guidance and protection (Ephirim-Donkor, Citation2016). In contrast, the death of a young person is deemed premature and mostly attributed to other than natural causes. Again, among the Dagombas, for example, the death of a young person is usually attributed to witchcraft. Premature deaths are mourned bitterly.

It may seem surprising to some readers that there were little gender-based or rural-urban differences in the emerging discourse among participants. For example, in the area of declining elders-ambiguous ancestors, there was a degree of convergence in male and female participants’ perspectives. Except for the reference to “prostate enlargement” that results in difficulty and frequency of passing urine among men, there was no gender-based difference in participants’ description of senescence and the journey to death. However, in the area of powerful seniors, a gender-based difference emerges which is grounded in the cultural practices of participants. Whereas female participants referred to care for grandchildren as a key component of their positions of influence, male participants referenced their administrative, mentoring, and overseer roles in the family and community.

6. Study limitations

In drawing conclusions from the study, its limitations should be noted. Importantly, the findings are based on data provided by a sample of 23 participants and the interview data were not triangulated with data from a survey or participant observation. Again, the sample was predominantly northern and urban, and what older Ghanaians expect society in general and government in particular to do to support them is not captured in this paper. Further, the sample for this study was 60% male. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized; they constitute a partial, rather than a full, discourse on aging in Ghana. Future studies using mixed methods approaches and involving larger samples are needed to build on the current study.

7. Conclusion and implications

7.1. Conclusion

This paper makes a contribution to literature on aging and older adults in Ghana. The study provides aging scholars and policy analysts an understanding of local discourses of aging from the unique perspectives of older Ghanaians. In the emerging discourse, aging subjects become powerful seniors but also experience decline and ambiguity in social relations. On the one hand, aging subjects become powerful elders due to an accumulation of experience, knowledge and wisdom, which are important resources for socialization and problem solving. Because of their social power and influence, elders superintend over the affairs of families and communities, as they make decisions and/or take actions that have consequences in the present and in the future. On the other hand, however, decline and ambiguity is intrinsic to the aging experience, as the aging elder accumulates physical, cognitive, and functional limitations—senescence—that presage the death event. In the emerging discourse, the ambiguous place of elders draws from the fact that, in death, the elder is not absolutely and eternally absent from among the living. The belief in ancestors, who are assumed to have transcended mortal weaknesses and attained supernatural powers, ensures that the dead elder has an important mediational role to play in human affairs. The local discourse on aging reported in this study builds on global discourses on aging in current circulation. Whereas on one hand social anthropologists construct elders as agents of influence who constitute a bridge between the past and the future, on the other hand, medical science and public health construct older adults as sick, weak, and dependent subjects whose place is in respite and long-term care facilities. Clearly, discourses on aging are particular ways of speaking to and about older adults and serve as surveillance on everyday practice—individual behavior and collective responsibility toward the elderly.

7.2. Implications

Findings of the study have some implications for practice. First, the discourse of powerful senior suggests that elders have something of value that we could tap for local and national development. Therefore, it is recommended that, to the best of their abilities, older adults be engaged in peace building and dispute resolution efforts, child protection and childcare policy decision-making, local planning and community problem solving efforts, and the teaching of history from experience. To that effect, the role of the Ghana Council of State (or Council of Elders) as advisor to the President and the incorporation of older people in the work of the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC) is lauded and should be replicated at the local level. Perhaps there is need for Councils of Elders at regional and district levels to offer policy advice and proffer solutions to social problems. On the other hand, the discourse of declining elder suggests that there are issues to address in the lives of aging persons. The increased likelihood of disease and death among aging persons calls for an improved and functional healthcare system leveraged across rural and urban Ghana and friendly to both men and women. It is therefore recommended that older adults be given income and housing assistance as well as increased access to affordable healthcare services to attenuate decline and loss. In that regard, the Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty (LEAP) program being piloted by the government of Ghana is laudable, and should be rolled out to cover many older adults. In addition, government should invest more in the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) to provide full rather than partial coverage for the health care needs of older adults. Further research is needed to explore how older adults in Ghana are coping with the challenges of aging and what additional resources they require for healthy aging.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul Alhassan Issahaku

Dr. Issahaku has a comprehensive research program that encompasses the broader topics of family welfare, community well-being, and public health, and he studies a wide range of issues including domestic violence (DV) and intimate partner violence (IPV); child abuse and neglect; youth social ex/inclusion; aging and older adults; community development; and program evaluation. Dr. Issahaku has a keen interest in the experiences of youth/young people, particularly, those labelled marginalized and vulnerable. The goal is to learn to understand and shape the world from young people<apos;>s perspective. Dr. Issahaku<apos;>s scholarship on aging and older adults seeks to highlight three points: older adults are not a homogenous population; older adults have the agency of social action; and there is injustice against older adults. The research reported in this paper comes from a wider project which has addressed topics such as “older adults” expectations and experiences with health care professionals’ and “challenges and opportunities for social participation experienced by older adults”.

References

- Aboderin, A. (2004). Intergenerational family support and old age economic security in Ghana. In P. Lloyd-Sherlock (Ed.), Living longer: Ageing, development and social protection (pp. 210–16). Zed Books.

- Adamek, M. E., Kotecho, M. G., Chane, S., & Gebeyaw, G. (2022). Challenges and assets of older adults in sub-Saharan Africa: Perspectives of gerontology scholars. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 34(1), 108–126. doi:10.1080/08959420.2021.1927614

- Atobrah, D. (2016). Elderly women, community participation and family care in Ghana: Lessons from HIV response and AIDS orphan care in Manya Krobo. Ghana Studies, 19(1), 73–94. doi:10.1353/ghs.2016.0004

- Attar-Schwartz, S., Tan, J., Buchanan, A., Flouri, E., & Griggs, J. (2009). Grandparenting and adolescent adjustment in two-parent biological, lone-parent, and step-families. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(1), 67–75.

- Ayernor, P. K. (2012). Diseases of ageing in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal, 46(2 Suppl), 18–22.

- Ayernor, P. K. (2016). Health and well-being of older adults in Ghana: Social support, gender and ethnicity. Ghana Studies, 19(1), 95–129. doi:10.1353/ghs.2016.0005

- Biritwum, R., Mensah, G., Yawson, A., & Minicuci, N. (2013). Study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) wave 1: The Ghana national report. World Health Organization.

- Breytspraak, L. M. (1984). The development of self in later life. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

- Cattell, M. G., & Albert, S. M. (2009). Elders, ancients, ancestors and the modern life course. In J. Sokolovsky (Ed.), The cultural context of aging: Worldwide perspectives (pp. 115–133). Praeger.

- Chapman, S. N., Pettay, J. E., Lahdenpera, V., & Lummaa, S. N. (2018). Grandmotherhood across the demographic transition. PLoS ONE, 13(7), e0200963. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200963

- Chapman, S. N., Pettay, J. E., Lummaa, V., & Lahdenpera, M. (2019). Limits to fitness benefits of prolonged post-reproductive lifespan in women. Current Biology, 29(4), 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.052

- Clarke, P. (2009). Understanding the experience of stroke: A mixed-methods agenda. The Gerontologist, 49(3), 293–302. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp047

- Coe, C. (2016). Not a nurse, not a house help: The new occupation of elder care in urban Ghana. Ghana Studies, 19(1), 46–72. doi:10.1353/ghs.2016.0003

- Coe, C. (2017). Transnational migration and the commodification of eldercare in urban Ghana. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 24(5), 542–556. doi:10.1080/1070289X.2017.1346510

- De Witte, M. (2001). Long live the dead! Changing funeral celebrations in Asante, Ghana. Aksant Academic Publishers.

- De-graft Aikins, A., Kushitor, M., Sanuade, O., Dakey, S., Dovie, D., & Kwabena-Adade, J. (2016). Research on aging in Ghana from the 1950s to 2016: A bibliography and commentary. Ghana Studies, 19(1), 173–189. doi:10.1353/ghs.2016.0008

- Drah, B. B. (2014). Older women, customary obligations and orphan foster caregiving: The case of Queen Mother in Manya Klo, Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29(2), 211–229. doi:10.1007/s10823-014-9232-y

- Elder, G. H. (1995). The life course paradigm: Social change and individual development. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder Jr., & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 101–139). American Psychological Association.

- Ephirim-Donkor, A. (2016). African religion defined: A systematic study of ancestor worship among the Akan (3rd edition). Hamilton Books.

- Ferreira, M., & Makoni, S. (2002). Towards a cultural and linguistic construction of late-life dementia in an urban African population. In S. Makoni & K. Stroeken (Eds.), Ageing in Africa: Sociolinguistics and anthropological approaches (pp. 21–42). Ashgate.

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language. Pantheon Books.

- Garbarino, J. (1985). Adolescent development: an ecological perspective. Columbus: Merrill Publication Co.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2013). 2010 population and housing census report: The elderly in Ghana. Ghana Statistical Service.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census: General report volume 3B. Ghana Statistical Service. https://census2021.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/reportthemesub/2021%20PHC%20General%20Report%20Vol%203B_Age%20and%20Sex%20Profile_181121b.pdf

- Giele, J. Z., & Elder, G. H. (1998). Methods of life course research. Sage.

- Government of Ghana. (2010). Ghana national ageing policy: Ageing with security and dignity. Ministry of Employment and Social Welfare.

- Gubrium, J. F. (1975). Living and dying at Murray Manor. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

- Gurven, M., & Kaplan, H. (2009). Beyond the grandmother hypothesis: Evolutionary models of human longevity. In J. Sokolovsky (Ed.), The cultural context of aging: worldwide perspectives (pp. 53–66). Praeger.

- He, W., Aboderin, I., & Adjaye-Gbewonyo, D. (2020). Africa aging: 2020. International Population Reports, P95/20-1. United States: U.S. Census Bureau, 20 March 2022. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p95_20-1.pdf

- Help Age International. (2008). Older people in Africa: a forgotten generation. http://eng.zivot90.cz/uploads/document/205.pdf

- Issahaku, P. A. (2018). What women think should be done to stop intimate partner violence in Ghana. Violence and Victims, 33(4), 627–644. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-15-00053

- Issahaku, P. A., & Neysmith, S. (2013). Policy implications of population ageing in West Africa. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 33(3/4), 186–202. doi:10.1108/01443331311308230

- Kpessa-Whyte, M. (2018). Aging and demographic transition in Ghana: State of the elderly and emerging issues. Gerontologist, 58(3), 403–408. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx205

- Kuuire, V. Z., Tenkorang, E. Y., Rishworth, A., Luginaah, I., & Yawson, A. E. (2017). Is the pro-poor premium exemption policy in Ghana’s NHIS reducing disparities among the elderly? Population Research and Policy Review, 36(2), 231–249. doi:10.1007/s11113-016-9420-2

- Kwankye, S. O. (2013). Growing old in Ghana: Health and economic implications. Postgraduate Medical Journal of Ghana, 2(2), 88–97. http://gcps.edu.gh/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Growing-old-in-Ghana-health-and-economic-implications.pdf

- Lee, R., & Vaughan, M. (2008). Death and dying in the history of Africa since 1800. The Journal of African History, 49(3), 341–359. doi:10.1017/S0021853708003952

- Li, X., Cai, L., Cui, W. L., Wang, X. M., Li, H. F., He, J. H., & Golden, A. R. (2020). Association of socioeconomic and lifestyle factors with chronic non-communicable diseases and multimorbidity among the elderly in rural southwest China. Journal of Public Health (Oxf), 42(2), 239–246. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdz020

- Lopez-Otin, C., Blasco, M. A., Patridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hall marks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194–1217. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039

- Makoni, S., & Stroeken, K. (2002). Towards transdisciplinary studies on ageing in Africa. In S. Makoni & K. Stroeken (Eds.), Ageing in Africa: Sociolinguistics and anthropological approaches (pp. 1–18). Ashgate.

- Margolis, R., & Wright, L. (2017). Healthy grandparenthood: How long is it, and how has it changed? Demography, 54(6), 2073–2099. doi:10.1007/s13524-017-0620-0

- Marshall, V. W., Martin-Matthews, A., & McMullen, J. A. (2016). The interpretive perspective on aging. In V. L. Bengston & R. A. Settersten Jr. (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Aging – Third edition (pp. 381–400). Springer Publishing Company.

- Mason, J., May, V., & Clarke, L. (2007). Ambivalence and paradoxes of grandparenting. Sociological Review, 55(4), 687–706.

- Mayer, K. U. (2009). New directions in life course research. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 413–433. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134619

- McMullen, L. M. (2011). A discursive analysis of Teresa`s protocol: Enhancing oneself, diminishing others. In F. J. Wertz, K. Charmaz, L. M. McMullen, R. Josselson, R. Anderson, & E. McSpadden (Eds.), Five ways of doing qualitative analysis: Phenomenological psychology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, narrative research, and intuitive inquiry (pp. 205–223). The Guilford Press.

- Mini, G. K., & Thankappan, K. R. (2017). Pattern, correlates and implications of non-communicable disease multimorbidity among older adults in selected Indian states: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 7(3), e013529. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013529

- Minicuci, N., Biritwum, R. B., Mensah, G., Yawson, A. E., Naidoo, N., Chatterji, S., & Kowal, P. (2014). Sociodemographic and socioeconomic patterns of chronic non-communicable disease among the older adult population in Ghana. Global Health Action, 7(1), 1–13. doi:10.3402/gha.v7.21292

- Mistry, S. K., Ali, A. R. M. M., Yadav, U. N., Ghimire, S., Hossain, B., Shuro, S. D., Saha, M., Sharwar, S., Nirob, M. H., Sekaran, V. C., & Harris, M. F. (2021). Older adults with non-communicable chronic conditions and their health care access amid COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0255534. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255534

- Moller, V., & Sotshongaye, A. (2002). They don’t listen: Contemporary respect relations between Zulu grandmothers and grandchildren. In S. Makoni & K. Stroeken (Eds.), Ageing in Africa: Sociolinguistics and anthropological approaches (pp. 203–225). Ashgate.

- Nukunya, G. K. (2003). Tradition and Change in Ghana: Introduction to Sociology. Ghana Universities Press.

- Oakley, R. (2002). Imprints of history and economy across the life course of an elderly Namanqualander 1920-1996. In S. Makoni & K. Stroeken (Eds.), Ageing in Africa: Sociolinguistics and anthropological approaches (pp. 67–86). Ashgate.

- Palmer, K., Monaco, A., Kivlpelto, M., Onder, G., Maggi, S., Michel, J. P., Prieto, R., Sykara, G., & Donde, S. (2020). The potential long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on patients with non-communicable diseases in Europe: Consequences for healthy ageing. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(7), 1189–1194. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01601-4 This reference has been inserted in the text on page 22

- Patrick, J. H., & Tomczewski, D. K. (2007). Grandparents raising grandchildren: benefits and drawbacks? custodial grandfathers. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 5(4), 113–116.

- Potter, J. (2004). Discourse analysis as a way of analyzing naturally occurring talk. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice (pp. 200–221). Sage.

- Rosenberg, H. G. (2009). Complaint discourse, aging and caregiving among the Ju/’hoansi of Botswana. In J. Sokolovsky (Ed.), The cultural context of aging: Worldwide perspectives (pp. 30–52). Praeger.

- Runyan, W. M. (1982). Life histories and psychobiography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sagner, A. (2002). Identity management and old age construction among Xhosa-speakers in Urban South Africa: Complaint discourse revisited. In S. Makoni & K. Stroeken (Eds.), Ageing in Africa: Sociolinguistics and anthropological approaches (pp. 43–66). Ashgate.

- Schutz, A. (1967). The phenomenology of the social world. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Singleton, R. A., & Straits, B. C. (2005). Approaches to Social Research. Oxford University Press.

- Sokolovsky, J. (2009). The life course and intergenerational ties in cultural and global context. In J. Sokolovsky (Ed.), The cultural context of aging: Worldwide perspectives (pp. 105–114). Praeger.

- Stroeken, K. (2002). From shrub to log: The ancestral dimension of elderhood among Sukuma in Tanzania. In S. Makoni & K. Stroeken (Eds.), Ageing in Africa: Sociolinguistics and anthropological approaches (pp. 89–108). Ashgate.

- Tawiah, E. O. (2011). Population ageing in Ghana: A profile and emerging issues. African Population Studies, 25(2), 623–645. doi:10.11564/25-2-249

- United Nations. (2019). World population prospects 2019: Highlights. https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf

- van der Geest, S. (1997). Money and respect: The changing value of old age in rural Ghana. Africa, 67(4), 534–559. doi:10.2307/1161107

- Van der Geest, S. (2002). ‘I want to go!’ how older people in Ghana look forward to death. Ageing and Society, 22(1), 7–28. doi:10.1017/S0144686X02008541

- Van der Geest, S. (2004). They don’t come to listen: The experience of loneliness among older people in Kwahu, Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 19(2), 77–96. doi:10.1023/B:JCCG.0000027846.67305.f0

- Wetherell, M. (1998). Positioning and interpretative repertoires: Conversation analysis and post-structuralism in dialogue. Discourse and Society, 9(3), 387–412. doi:10.1177/0957926598009003005

- Willig, C. (2003). Discourse analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 159–183). Sage.

- Wilson, T. P. (1970). Normative and interpretive paradigms in sociology. In J. D. Douglas (Ed.), Understanding everyday life (pp. 57–97). Aldine.

- Wood, L. A., & Kroger, R. O. (2000). Doing discourse analysis: Methods in studying action in talk and text. Sage.

- World Health Organization. (2008). The global burden of disease: 2004 update.

- World Health Organization. (2013). Mental health and older adults. fact sheet No. 381. WHO. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs381/en/

- World Health Organization. (2014). Ghana country assessment report on aging and health. World Health Organization.

- Wu, F., Guo, Y., Chatterji, S., Zheng, Y., Naidoo, N., Jiang, Y., Biritwum, R., Yawson, A., Minicuci, N., Salinas-Rodriguez, A., Manrique-Espinoza, B., Maximova, T., Peltzer, K., Phaswanamafuya, N., Snodgrass, J. J., Thiele, E., & Ng, N. (2015). Common risk factors for non-communicable diseases among older adults in China, Ghana, Mexico, India, Russia, and South Africa: the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) wave1. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1407-0

- Yadav, U. N., Ghimire, S., Mistry, S. K., Shanmuganathan, S., Rawal, L. B., & Harris, M. (2021). Prevalence of non-communicable chronic conditions, multimorbidity and its correlates among older adults in rural Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 11(2), e041728. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041728

- Zelalem, A., & Kotecho, M. G. (2020). Challenges of aging in rural Ethiopia: “Old age is like the sunset: It brings disrespect and challenges”. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(8), 893–916. doi:10.1080/01634372.2020.1814475