Abstract

The last two socioeconomic crises (2008 and 2020) in Spain have aggravated the precarious situation of the youth population in the labour market, reducing their chances of emancipation. However, the information that can be obtained from official statistics shows that the impact has not been homogeneous, affecting young women to a greater extent due to their situation of structural vulnerability. This article analyses whether the situation of the youth population in the Spanish labour market is due to variables that draw some of the crosscutting axes of social inequality: origin, gender and level of education. In addition, it examines whether the measures aimed at young people implemented since 2013 to reduce the effects of the crises, have considered these variables in the design of public policies. Any diagnosis, and the possible actions that may arise from it, should take into account the multidimensional nature that falls under the umbrella of the concept of youth.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article aims to visualize the comparative social inequality of young adults in Spain. This global objective is developed analysing quantitatively how age, sex, and migratory origin can explain social inequalities. The last two socioeconomic crises (2008 and 2020) have enhanced precarity in the labour market for young people. One of the main consequences is that chances to achieve residential emancipation from their families have been lowered. The specific role of young women in this process is highlighted because it depends not only on the current situation, but also on their structural vulnerability. Multiple measures that have been implemented by the Spanish public administrations, in response to the effects of the socioeconomic crisis in its many facets (health, employment, housing, etc.), but they have not been as effective as necessary, mainly due to their uniform character. To address the poor objective condition of many young people in Spain, policies designed according to their heterogeneous nature are necessary.

1. Introduction

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the employment situation of young people was characterized by a high unemployment rate and access to employment based on temporary employment, partiality, overqualification, underemployment, low prospects of personal promotion, informal work and low wages (Cabasés & Pardell, Citation2014; Úbeda et al., Citation2020a). A situation that developed a long way back, although it became worse following the 2008 crisis (Arranz et al., Citation2018; Castillo & López, Citation2018; Úbeda et al., Citation2020b; among others).

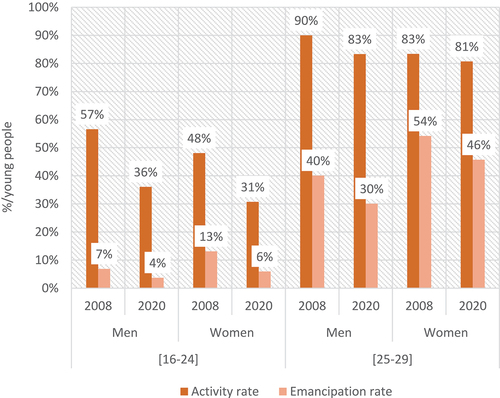

Through both crises, that of 2008 and 2020, the youth population has seen its “presence” in the labour market (activity rate) and its emancipation rate simultaneously reduced (López, Citation2020a), and has ended up receiving lower average real wages compared to previous generations at similar ages (Cabasés et al., Citation2021; Puente & Galán, Citation2014). Likewise, they have lived with uncertainty due to the impossibility of planning a stable employment future (Feixa et al., Citation2015) to the point that, due to the “model” of precarious occupation they enter, they are not aware of their belonging to a social class, and they do not offer resistance to the “model”, accepting it as unique and inevitable (Cabasés et al., Citation2017). It is a model that has affected the female group with greater intensity, in a context of persistent inequality of women in the labour market (GESTHA, Citation2020).

Faced with this reality, arguments have been made to demand the introduction of specific measures (which, when they have arrived, have in general been rather disappointing) and to underline that the employment situation of young people only crystallizes the structural deficits of the labour market. Specifically, with the measures adopted as of 2013 within the framework of the Youth Guarantee, it was not possible to reverse this model of youth employment. Perhaps the growth in unemployment rates was alleviated, but with little impact on the labour market (Cabasés & Úbeda, Citation2021).

In this article we want to establish that the situation of the youth group in the labour market is not homogeneous, but is related to variables that draw some of the crosscutting axes of social inequality: origin, gender and educational level; not forgetting that social inequalities linked to the individual and family class of origin persist. Specifically, we seek to sustain that the situation of greater vulnerability of young women and foreign population in the labour market is a structural issue and not a temporary one. For this purpose, the time frame of reference is the years 2008 and 2020, which marked two remarkable milestones in the recent history of Spain. The year 2008, as the point of departure of the socioeconomic crisis caused by the bursting of the real estate bubble that had occurred more than a decade earlier; the year 2020 due to the economic, health and social meltdown brought about by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Methodology

As a methodological starting point, this research considers the category “young” as a socially and historically constructed tool, which has served to homogenize and seal different social groups (Feixa, Citation2008; Martín, Citation1998).

First, the evolution of a group of indicators on access to a job and the working conditions of those under 30 years of age (activity, employment, unemployment, emancipation, temporality and part-time work) has been analysed by gender and nationality, based on the microdata from the Active Population Survey for the years 2008–2020 and the Continuous Sample of Working Lives of 2019.

Second, a non-hierarchical classification has been obtained, using the K-means algorithm (uses the criterion of matching two groups with the same distance between them, considering it as the mean of the distances between all pairs of individuals, in which one member of the pair belongs to each previously formed group), of the youth population employed in 2008 and 2020 from factorial variables previously obtained in a principal components analysis. These new segmentation variables are a linear combination of the original variables that prove to have greater explanatory power on the existing variability among the young employed population. The variables initially considered have been the type of contract, type of working day, juxtaposition of studies and work, seniority, activity sector and professional category.

In the principal components analysis, the Kaiser criterion has been chosen to determine the number of factorial axes—only those with eigenvalues greater than 1-, according to which the factors that present eigenvalues greater than one have been conserved. These factors retain 70.8% of the information provided by the original variables and three components have been obtained that define 29.4%, 23.3% and 18.1% of the total variability, respectively. From these, the employed youth population has been classified into mutually exclusive categories that contribute to understanding the total existing variability.

And finally, the measures implemented since 2013 to combat youth unemployment have been examined.

3. Results. evolution of the elements that make up the youth employment model between 2008 and 2020

In line with the Europe 2020 Strategy, the elements taken into consideration to analyse the youth employment model are access to the labour market and working conditions such as the type of contract, working hours and salary conditions.

3.1. Access to the labour market

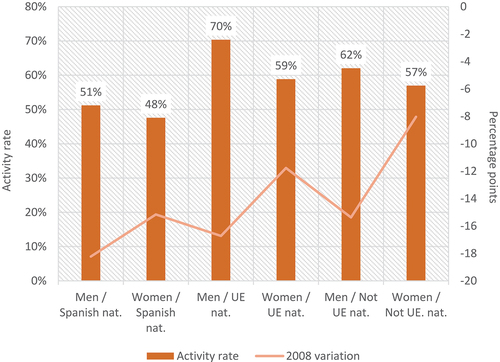

Using the activity rate as a generic indicator to quantify the population that is present in the labour market, either working or unemployed and actively seeking employment, notable differences can be observed within the youth population as a whole (figure ). It is necessary to bear in mind that, in general, the full incorporation of the youth population into the workforce usually occurs when the training cycle has been completed, although it is also very common to combine studies and work (especially at university) and take advantage of the holidays in the academic year to obtain salaried income, no matter how temporary it may be (López, Citation2020b).

Figure 1. Activity rate of the young population in Spain. 2020 and variation compared to 2008(Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE)).

The group with the greatest presence in the labour market in 2020 was men of European nationality, followed without many significant differences, by the rest of the foreign youth population: women of European nationality and men and women of non-EU nationality. However, the group of Spanish nationality had a lower presence (this article defines the foreign population based on nationality; in practice, there are usually only few divergences using the place of residence or nationality). It should be taken into account that this group tends to enter the labour market later, more so women than men (López, Citation2020b). This duality already occurred in 2008, although in 2020 there was a lower proportion of active young people from the labour point of view, and the greatest decreases in employment were concentrated in the population of Spanish nationality. The disengagement of young people from the labour market was, in fact, one of the main effects of the 2008 socio-economic crisis.

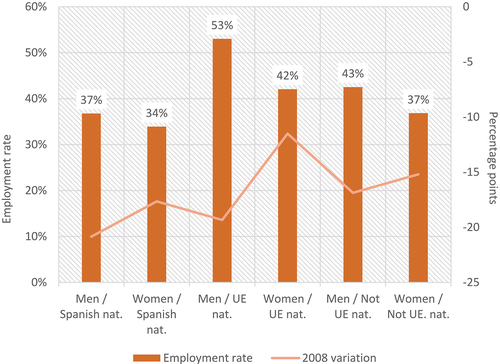

Something similar happened with the employment rate. In 2020, regardless of working conditions, only 36.4% of the young people were working in Spain, while in 2008 they accounted for more than half (55.2%). This abrupt reduction in employment, much higher than that experienced by the non-youth population, reached the highest levels among the youth population of Spanish nationality, but also among young men of European nationality. Despite this, this latter group was the one with the highest probability of being employed in 2020. In any case, the differences according to gender, always with less employment among women, were repeated regardless of their nationality (figure ).

Figure 2. Employment rate of the youth population in Spain. 2020 and variation compared to 2008(Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE)).

The youth group has been structurally characterized by registering a higher unemployment rate—proportion of unemployed people out of the total active people- than the rest of the population. In Spain, starting in 2008, this gap gradually widened until it reached its maximum in 2013, with a youth unemployment rate of 42.4%, while that of the rest of the population over 15 years of age stood at 26.1 %. From then on, and until 2019, unemployment in Spain declined, as did the differential according to age. In 2020, with the new health crisis, unemployment increased again, especially among young people.

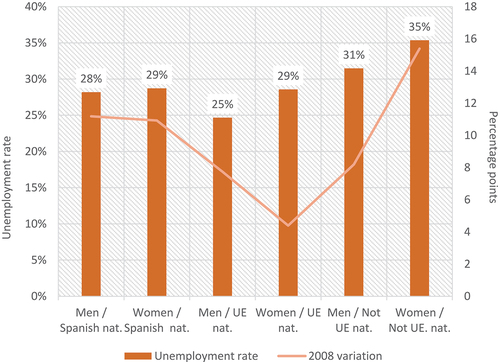

In 2020, the distribution of the youth unemployment rate by gender and nationality did not follow the same pattern as the activity and employment rates. While inequality between men and women was only observed among the foreign population, within the population of Spanish nationality the unemployment rate was practically the same (28.2% men and 28.7% women). Among the youth population of foreign nationality, women always presented a higher risk of unemployment, particularly non-EU women. Also, the increase in unemployment between 2008 and 2020 was very uneven: it only increased 4.4 pp among women of EU nationality and reached maximum levels of more than 10 points among men and women of Spanish nationality and women of non-EU nationality (figure ).

3.2. Working conditions

Despite the fact that activity, employment and unemployment allow a quantitative or volumetric approximation of the labour integration of young people, they tell us little about the specific conditions of the jobs they end up occupying. In order for them to be able to carry out vital independent projects in the medium and long term, in addition to working and having an income of their own for the first time, they must achieve (themselves or their partners: one of the characteristics of the residential emancipation of young people in Spain is that it is rarely done alone, especially in the case of women. (CES, Citation2020)) an economic sufficiency to cover the necessary expenses, such as the rent or the household bills.

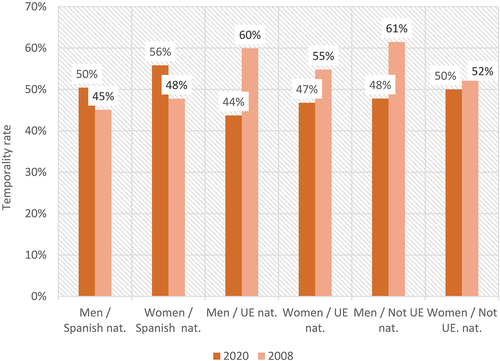

Regardless of the macroeconomic cycle, young people have higher levels of temporary employment that do not completely disappear when they turn 30 years old; rather they drag on beyond this age, generating more discontinuous and vulnerable work itineraries (Cabasés et al., Citation2021). In the first half of 2020—during the state of alarm period that restricted many economic activities—temporary employment was drastically reduced, due to the fact that many temporary jobs were not renewed or disappeared and permanent jobs were not created. Between 2008 and 2020, the evolution of temporality was antagonistic according to age groups: while it increased among the young population (from 48.5% in 2008 to 52.0% in 2020), it fell slightly among the population aged 30 to 64 (from 22.8% in 2008 to 19.5% in 2020). But it cannot be concluded that temporality among the young population has followed a homogeneous pattern. If in 2008 young Spanish people maintained a lower rate of temporary employment, in 2020 the opposite happened. The expansion of temporality was particularly intense among young Spanish women. However, the temporary employment rate among the male group of European nationality, decreased from 59.9% in 2008 to 43.7% in 2020 (figure ).

Figure 4. Temporality rate of the young population in Spain. 2008–2020(Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE)).

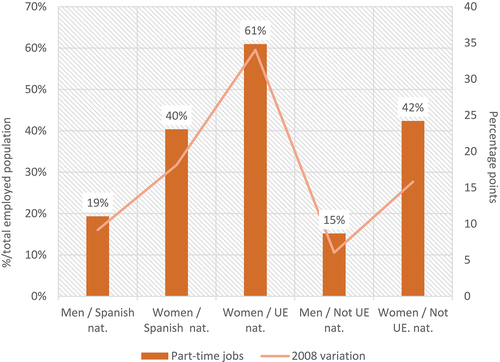

Regarding part-time work, the increase was not homogeneous. Between 2008 and 2020, part-time work increased by more than 15 pp among young women. In 2020, more than 40% of women worked part-time, reaching 61% in the female group with European nationality (figure ). This fact cannot be attributed to a voluntary decision to work fewer hours in order to be able to take on other activities (for example, to continue studying or to take care of dependents). At the end of 2020, most of the part-time employed population explicitly stated that they did so because they simply had not found a full-time alternative, in particular, 55.8% of young men and 59.8% of young women.

Figure 5. Young population in Spain with part-time jobs. 2020 and variation compared to 2008(Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE)).

If we consider the percentage of the youth population that worked part-time in a temporary contract, we can observe inequality by gender. Although over the last 12 years it has been within the male population that has increased the most, young women are the ones with the highest values in 2020 and with almost the same proportion among women of Spanish nationality (20.9%), EU nationality (22.0%) and non-EU nationality (19.7%).

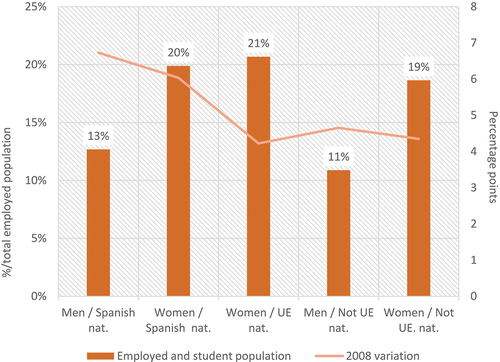

In addition, some young people combine work and study, sometimes to cover part of the economic expense that their studies place upon their families, and sometimes as a first contact with the world of work. In many cases, the simultaneous academic and labour activities imply that the jobs carried out are not very consistent with the young person’s qualifications; the work carried out is a secondary activity with the objective of increasing the young person’s educational capital with a view to obtaining qualified positions with higher professional prospects in the medium and long term (Strecker et al., Citation2018; Tejerina, Citation2020). As a result of the 2008 crisis, many young people began to “disappear” from the labour market to carry out training, considerably increasing the young student population. For this reason, Spain today has a young population with greater academic training than in 2008, especially in the group of young women with Spanish nationality (34% of said group).

The focus on studies as a strategy to preserve or improve the social status of the family of origin (Ballesteros et al., Citation2012) has also been transferred to the world of work. In 2020 it was more common to find young people studying and working simultaneously, especially in the female group (figure ).

Figure 6. Youth population in Spain working and studying simultaneously. 2020 and variation compared to 2008 * (Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE)) * Note: there are no significant data for men of foreign nationality from an EU country.

Concerning the types of jobs young people access, the difference by gender is clearly observed, regardless of the period. Taking into consideration only the population of Spanish nationality, young women are more present in sectors related to health, social services and education, and men in manufacturing and construction. Paradoxically, in hospitality and commerce, two sectors that are distinguished by their seasonality and lower wages, the differences are less significant. Young people of foreign nationality (EU or not) tend to have a greater role in the hospitality sector.

With the professional category, the contrast is even more evident. Young women of Spanish nationality are more likely to work in qualified jobs (“technical and scientific and intellectual professionals”) and in “catering, providing personal services, security and retail”, pointing to a clear indication of job segmentation even when only referring to young women. Young men of Spanish nationality, on the other hand, are proportionally more present in jobs of a more manual nature (“Craftsmen and skilled workers in the manufacturing and construction industries” and “Operators of fixed equipment and machinery, and assemblers”). Finally, “elementary occupations” refer to unskilled jobs, and this is where young people of foreign nationality are present to a greater extent.

Due to the pandemic, the increases in unemployment and inactivity were similar. With the publication of the results of the second quarter of 2020 by the INE, at the peak of the greatest economic recession, it was highlighted that the unemployment data were lower than expected, given the objective difficulties to actively find a job (a requirement to consider a person as unemployed) in a context of highly restricted mobility. In 2020, the “potentially active” population (seeking their first job or having previously lost one, admitting that they are available for work, but without having started any type of action) increased suddenly, and more so among the youth population—reaching 6% among men of Spanish nationality and 13% of foreign nationality. Compared to 2008, the increase was smaller than that of inactivity (work) and was focused on young men. However, young inactive people of non-EU nationality, men and women, are the ones who found themselves most often in this diffused territory between unemployment and inactivity (13% of men and 9% of women).

Among the youth population, there is a close interrelation between studies and work activity. Not only because most of the “inactive” youth population is studying, but also because training generates a notable bias in job opportunities. In the same way that unemployment is more extreme as the level of studies attained is lower (CES, Citation2020), the inverse relationship is also reproduced in terms of employment. The greater the training achieved and completed, the greater the proportion of people who are working. The job destruction that occurred after the COVID-19 pandemic was more pronounced for the most vulnerable groups, with fewer possibilities of accessing post-compulsory studies. In 2020, 27.2% of the young population in Spain had managed to complete higher education, reaching 46.9% among the young employed population and to a greater extent in the female group. Among the population of Spanish nationality, the contrast was especially striking: 61.2% of young employed women had higher education, as opposed to 44.0% of men of the same age and nationality.

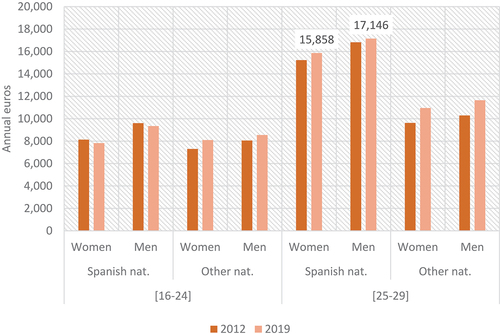

Regarding the salary conditions, the information provided by the Continuous Samples of Working Lives of 2012 and 2019 is available—extract of anonymized individual data, from the Social Security and the Tax Agency. It can be observed (figure ) that the wage gap is structural, reaching its maximum in the group of Spanish nationality. In turn, the average annual remuneration grew in all groups except for those under 25 years of age of Spanish nationality, reaching the highest values in 2019 among those aged between 25 and 29 of the same nationality, although compared to the average wages of 30–34-year-olds they were 30% lower. By educational level, women with a university degree aged 25 to 29 earned 30% more in 2019 than the average of all women in this age group. In addition, the salaries of young men of Spanish nationality of the same age group were 32% higher than those of the rest of nationalities and salaries of young women of Spanish nationality were 31% higher.

3.3. Emancipation

Uncertainty and the delay in the emancipation of young people are related to their situation in the labour market and the housing market, especially in times of economic recession, due to an increase in the training period, a fall in employment and an increase in unemployment and the difficulty of obtaining housing. In 2008 the situation worsened (Valls, Citation2015); however, between 2014 and 2020, despite it being a period of economic growth, youth emancipation figures did not improve due to persistent high rates of youth unemployment, the high proportion of temporary employment and part-time work, and the mismatches between young people’s qualifications and the labour market demands (CES, Citation2020). The constant rise in the housing rental market and the toughening of conditions for financial credit were also obstacles that prevented leaving the family home.

With the emergence of COVID-19, the situation worsened. At the end of 2020, only 30% and 45.7% of men and women aged 25 to 29 respectively, were emancipated (percentage of people residing outside the home of origin over the total of the same age). And those who were emancipated at the beginning of the pandemic and were affected by an ERTE (temporary employment regulation file) or had lost their jobs, had reduced the possibility of taking over a rent, a mortgage or basic utility bills.

Over the last few years, an inverse relationship has been observed between the emancipation rate of young people and their presence in the labour market, being more pronounced in those under 25 years of age (figure ). During the 2008–2020 period, the activity rate of the female group was lower; however, their emancipation rate was higher compared to the male group, especially in the 25 to 29 age group. This is due to the fact that young women do not emancipate and their income is disposable, while young men depend on their own income (Social Prism).

3.4. Young women and the economic cycle

In the last 30 years, the presence of women in the labour market has maintained an upward trend, not only because of the economic growth rate of these years (despite the recessions in the 1990s) but also as a consequence of the trend in women’s liberation (Cebrián & Moreno, Citation2007) and the higher level of training women have been achieving as a strategy to improve their employability. At the end of 2020, after two crises, 56.9% of women between the ages of 25 and 29 had reached a higher education level compared to 45.8% of men of the same age group.

However, women’s commitment to greater training and presence in the labour market has not been accompanied by a reduction in inequality with respect to the male group, even at higher education levels. In the period of economic boom between 1997 and 2007, the employment rate of young women increased by 20 pp and 24 pp if they had attained a higher education level. However, occupational segregation by gender also grew (López et al., Citation2019), that is, the concentration of women in certain occupations (with low levels of qualification, shorter hours and lower wages), which responded to supposed social stereotypes and feminine cultures of greater manual dexterity and sensitivity to personal care, being the cause of the wage gap and hindering mobility between occupations (Ibáñez & Vicente, Citation2020). With the arrival of the 2008 crisis, due to the greater impact on the male group, the employment rates for men and women fell to the same level, while the unemployment rates also rose to equal levels, a situation that was reversed as of 2013 (figure ).

Figure 9. Employment and unemployment rates of people under 30 years of age. Spain, 1997–2019(Source: our own elaboration from Eurostat data [Last update: 30–10-2021]).

![Figure 9. Employment and unemployment rates of people under 30 years of age. Spain, 1997–2019(Source: our own elaboration from Eurostat data [Last update: 30–10-2021]).](/cms/asset/18c1d8cb-290e-45a8-9c6c-bf9459ee551b/oass_a_2064071_f0009_oc.jpg)

At the end of 2008, 45% of young women were employed, of which 41.5% with higher education, 15.4% underemployed (a person is underemployed when they work fewer hours than other people in similar positions and, at the same time, state that they are in a position to extend their working day immediately), 48% with temporary contracts, 35% in catering, providing personal services, security and retail, 15.4% as technical, scientific and intellectual professionals, 14.8% as technical and support professionals and 10.6% in elementary occupations. However, the impact of the crisis, especially between 2008 and 2013, aggravated the employment situation of women under 30 years of age, placing them in a situation of vulnerability before the start of the pandemic. Hence, at the end of 2020, only 29.9% were employed, of which 58.2% had higher education, 19.7% were underemployed and 55.6% had temporary contracts.

4. Categorization of the types of employment of young people

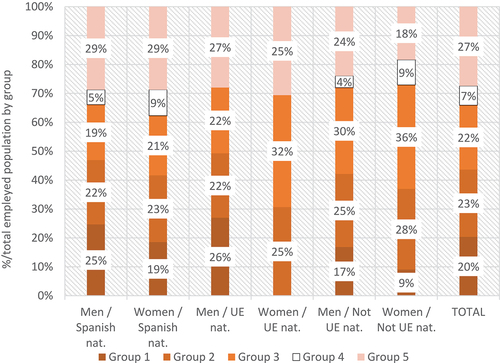

In order to classify the young employed population into mutually exclusive categories, which allow for the explanation of social differences, a two-stage process of main components and non-hierarchical aggregation has been developed, based on variables related to occupation. The result obtained has been five occupational groups or categories considering the two reference years of this article jointly (2008 and 2020):

Group 1: young people with higher education, with permanent contracts, greater seniority in the company and very often in the manufacturing industry.

Group 2: young people with temporary contracts and new to the job.

Group 3: people who work in the hospitality sector, in tasks that do not require a high level of qualification, but with permanent contracts and some seniority in the job.

Group 4: young people with short-term temporary contracts, part-time, who combine work with studies and work mainly in retail and hospitality.

Group 5: young people who do not work for others or, if they do, they do so in the public sector, with temporary contracts, but developing highly qualified tasks, thanks to their high level of education.

When crossing this general grouping with the variables gender and nationality, some very revealing conclusions are obtained (figure ). First, between 2008 and 2020 the distribution of the young population in these five categories did not vary excessively, except for the growth of group 3, which has been to the detriment of group 1. Second, women are more present in the groups with the greatest precariousness (2 and 4). In groups 2 and 5, which curiously define very different casuistry (temporary employment with higher turnover and qualified employment in the public sector or self-employed), the differences by gender are the smallest. Third, women of foreign nationality (whether EU or not) and men of non-EU nationality are more likely to have short-term temporary contracts (group 2). Group 3, which brings together people employed in the hotel and retail trade on a stable basis, has a preeminent concentration of young women of non-EU nationality.

Figure 10. Grouping of young employed people in Spain according to job categories. 2020(Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE)).

This merely descriptive analysis has the virtue to contribute to defining clearly for the first time the multiplicity of variables and concepts that make up employment and working conditions.

5. Active employment policies since 2013

With the 2008 crisis, the growth of youth unemployment became a European problem led by southern European countries. The European Union (EU) proposed various initiatives aimed at establishing youth guarantees to ensure that all young people were employed or being trained (COM, Citation2012). In this sense, the EU Council approved the “Council Recommendation of 22 April 2013 on the establishment of the Youth Guarantee”, which urged Member States to design a system of Youth Guarantee (GJ), as an instrument to ensure that all young people under 25 years of age who were not working, training or education (young people in NEET situation), received a good job offer, continuing in education, apprenticeship training or internship, within four months after completing formal education or becoming unemployed.

Spain approved its Plan in December 2013 and in 2014 the implementation of the National Youth Guarantee Scheme (NYGS), within the framework of the Annual Employment Policy Plans. From its application between 2014 and 2018, different evaluations have revealed that the objectives set by the European Recommendation (EC, Citation2018; ECA, Citation2017) have not been achieved, since most of the actions planned in the NYGS, have not considered different aspects of people’s lives beyond the occupational in their design, or the intertwining mechanisms of social inequality and multiple exclusion, such as gender, ethnicity, age or social class (Úbeda et al., Citation2020b). In addition, the II Evaluation Report of the Youth Employment Initiative of the Ministry of Labour, Migration and Social Security of 2018, highlighted that young women with certain disadvantaged profiles such as inactive, with a low educational level, with disabilities, of immigrant origin or belonging to ethnic minorities and homeless or affected by exclusion in terms of housing, were underrepresented in the design of the measures contemplated in the NYGS. Moreover, the quality of the job offers received by young people in the framework of the YG was called into question, as they were a reflection of the situation of the labour market, thus raising doubts about the incidence of the YG in the labour market.

In 2018, the “Emergency Plan for Youth Employment 2019–2021” was approved with the aim of recuperating the quality of employment, fighting the gender gap in employment and reducing youth unemployment. In 2020, the antecedents and the starting point analysed by the Plan had already changed, the Plan having been designed under a reality that changed during the pandemic. Where the youth labour market is now heading for is uncertain. In fact, a performance evaluation which had been expected after 18 months was not furnished, and the set of indicators it was to be based on, had not been established either. It should be specified that the measures contained in said Plan were not designed under an intersectional approach, as can be seen from its analysis.

As of March 2020, a set of regulations were approved with the aim of responding to the health, economic and social crisis caused by COVID-19. However, the measures aimed at the youth population were rather sparse and those that were applied lacked a gender perspective. The measure adopted on temporary suspension of contracts and temporary reduction of working hours (ERTE) stands out as preventing the temporary employment situation from becoming structural and affected more than 327,000 women under 30 years of age during the second quarter of 2020, coinciding with the strict lockdown period (Table ).

Table 1. Estimated impact of ERTES by age and gender. 2020 (Source: our own elaboration from microdata of the Labour Force Survey (INE))

Another measure adopted to alleviate the situation of poverty and inequality caused by the pandemic was the Minimum Income Benefit (MIB), which rarely reached young people, since people under 23 years of age were excluded as beneficiaries, except in cases of gender violence, human trafficking and sexual exploitation. Moreover, young emancipated people between 23 and 29 years of age had to prove they had a different address from that of their parents, guardians or foster carers during the three years prior to the application. According to Eurostat, in 2020 the average age of emancipation in Spain was 29.8 years and according to INE data, 55% of young people aged 25 to 29 lived with their parents. Furthermore, if the risk of poverty or social exclusion is taken into account, in 2020, the figure for young women reached 29.3% compared to 31.2% of young men, highlighting that the MIB should consider inequalities by age.

Once again, the European response to mitigate the impact of the pandemic has been a new Youth Guarantee, which integrates the changing realities of the labour market and the double digital and ecological transition (CUE, Citation2020). Its implementation in Spain is developed through the “Youth Guarantee Plus 2021–2027 of decent work for young people”. This maintains the characteristic elements of 2014 (financing from the European Social Fund and management) and incorporates changes in aspects that have been shown to be inefficient and new content.

6. Conclusions

The socioeconomic crisis that the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it has further aggravated the employment situation of young people under 30 years of age. It could be argued that this group has experienced the full extent of some phenomena that have also affected the rest of the population. One year after the start of the health crisis, the number of employed persons under 30 years of age had decreased by 241,400 and their activity rate by 1.5 pp, with young women being the most affected: a lower employment rate (34%), a higher rate of underemployment (20%), temporary contracts (55.1%), part-time contracts (33.9%) and unemployment (31.3%, reaching 38.4% if the nationality is foreign).

In this article we have tried to corroborate that age, gender and migratory origin are still fully valid as cross-sectional variables that help to understand social inequalities. Considering the young population as a homogeneous, uniform group helps to hide existing social inequalities and leads to rather disappointing measures when attempting to appease the residential and labour exclusion that affect many young people. In Spain, the position of young women in the labour market depends not only on the current conditions, but also on their situation of structural vulnerability. In 2020, public administrations in Spain resolved to implement different measures to tackle the effects of the socioeconomic crisis in its multiple aspects (health, labour, housing, etc.). However, their effectiveness is more than questionable due to the lack of tradition in evaluating policies and because of the standardizing nature, which does not consider variables as decisive as gender, age or nationality.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

M. Àngels Cabasés

M. Àngels Cabasés is Doctor in Applied Economics and University Professor at the Department of Applied Economics of the University of Lleida. Currently, her research is focused on the economic impact of the employment policies for young people, mitigating a statistical and economic analysis of the labour market, just as the analysis of inequalities in income distribution. She is a member of the consolidation research group Joventut i Societat (JOVIS.com) and has participated in various national and European projects, in economic studies, innovation projects and in national and international conferences. She has held several university management posts.

Joffre López

Joffre López Oller works an independent researcher around youth, housing policies, social exclusion and poverty. Nowadays, he is one of the authors of Emancipation Youth Observatory from Spanish Youth Council and has participate in different studies about local urban policies and strategies, regional studies about living conditions of the young population and has different papers about the transition to adulthood in a quantitative perspective.

References

- Arranz, J. M., García-Serrano, C., & Hernández, V. (2018). Calidad del empleo: Una propuesta de índice y su medición para el periodo 2005-2013. Hacienda Pública Española, 225(2), 133–15. https://doi.org/10.7866/HPE-RPE.18.2.5

- Ballesteros, J. C., Mejías, I., & Rodríguez, E. (2012). Jóvenes y emancipación en España. Centro Reina Sofía sobre Adolescencia y Juventud.

- Cabasés, M. A., & Pardell, A. (2014). Una visión crítica del Plan de Implantación de la Garantía Juvenil en España. ¡Otro futuro es posible para las personas jóvenes! Bomarzo.

- Cabasés, M. A., Pardell, A., & Serés, A. (2017). El modelo de empleo juvenil en España (2013-2016). Política y Sociedad, 54(3), 733–755. https://doi.org/10.5209/POSO.55245

- Cabasés, M. A., & Úbeda, M. (2021). The Youth Guarantee in Spain: A worrying situation after its implementation. Economics and Sociology, 14(3), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2021/14-3/5

- Cabasés, M. A., Úbeda, M., Gómez, M. J., Feixa, C., Sánchez, J., & Riera, C. (2021). The evolution of employment precarity among young people in Spain, 2008-2018. The Social Observatory “La Caixa” Foundation. https://elobservatoriosocial.fundacionlacaixa.org/en/-/evolucion-de-la-precariedad-laboral-de-los-jovenes-en-espana?p_l_back_url=%2Fes%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dcabases

- Castillo, J., & López, P. (2018). Youth between social category and ideological alibi. Sociologia del lavoro, 149(149), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.3280/SL2018-149003

- Cebrián, I., & Moreno, G. (2007). El empleo femenino en el mercado de trabajo en España. Temas Laborales. Revista Andaluza de Trabajo y Bienestar Social, 91, 35–56. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2481145

- CES (2020). Jóvenes y mercado de trabajo en España. (Report No. 2/2020). Consejo Económico y Social. https://www.ces.es/documents/10180/5226728/Inf0220.pdf

- COM (2012). Proposal for a council recommendation on establishing a youth guarantee. (Report 729 final. Brussels, 5.12.2012). European Council.https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012PC0729&from=EN.

- CUE. (2020). Council recommendation of 30 October 2020 on A bridge to jobs – reinforcing the youth guarantee and replacing the council recommendation of 22 April 2013 on establishing a youth guarantee. (Report 2020/C 372/01). The Council of the European Union.https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020H1104(01)&from=EN

- EC. (2018). Youth guarantee country by country, Spain. May 2018. (Report December 2018). European Commissionhttps://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1161andlangId=enandintPageId=3353

- ECA. (2017). Youth unemployment – Have EU policies made a difference? (Report No. 5/2017). European Court of Auditors.https://www.eca.europa.eu/es/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=41096

- Feixa, C. (2008). De jóvenes, bandas y tribus. Ariel.

- Feixa, C., Cabasés, M. A., & Pardell, A. (2015). El juvenicidio moral de los jóvenes … al otro lado del charco. In J. M. Valenzuela (Ed.), Juvenicidio. Ayotzinapa y las vidas precarias en América Latina y España (pp. 235–269). NED Ediciones-El Colegio de la Frontera Norte-ITESO.

- GESTHA. (2020). Brecha salarial y Techo de cristal. GHESTA, Técnicos del Ministerio de Hacienda. https://www.ioncomunicacion.es/la-brecha-salarial-continua-ensanchandose-y-las-mujeres-cobran-4-915-euros-menos-que-los-hombres/

- Ibáñez, M., & Vicente, M. R. (2020). Occupational segregation by Sex in Spain 2001-2011: Ten years without progress. REIS: Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 171, 43–62. https://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.171.43

- López, J. (2020a). JUVENTUD EN RIESGO: Análisis de las consecuencias socioeconómicas de la COVID-19 sobre la población joven en España (Report No. 1, marzo-abril 2020). Consejo Juventud España.http://www.injuve.es/sites/default/files/adjuntos/2020/06/estudio_consecuencias_economicas_covid19_en_la_juventud.pdf

- López, J. (2020b). JUVENTUD EN RIESGO: Análisis de las consecuencias socioeconómicas de la COVID-19 sobre la población joven en España (Report No. 2, junio-julio 2020). Consejo Juventud España. http://www.injuve.es/sites/default/files/adjuntos/2020/06/estudio_consecuencias_economicas_covid19_en_la_juventud.pdf

- López, M., Nicolás, C., Riquelm, P., & Vives, N. (2019). Análisis de la segregación ocupacional por género en España y la Unión Europea (2002-2017). Revista Prisma Social, 26, 159–182. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3085

- Martín, E. (1998). Producir la juventud. ITSMO.

- Puente, S., & Galán, S. (2014). Un análisis de los efectos composición sobre la evolución de los salarios. (Report No. 57, Boletín Económico, febrero 2014). Banco de España. https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/InformesBoletinesRevistas/BoletinEconomico/14/Feb/Fich/be1402-art5.pdf

- Strecker, T., Ballesté, E., & Feixa, C. (2018). El juvenicidio moral en España: Antecedentes del concepto, causas y efectos. In M. A. Cabasés (Ed.), Jóvenes, trabajo y futuro (pp. 430–454). Tirant lo Blanch.

- Tejerina, B. (2020). Experiencias y metáforas sobre la precariedad y la hiperactividad de la juventud en un tiempo de espera. Revista Española De Sociología, 29(3 – Sup2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2020.76

- Úbeda, M., Cabasés, M. A., & Pardell, A. (2020a). Empleos de calidad para las personas jóvenes: Una inversión de presente y de futuro. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 38(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.5209/crla.68867

- Úbeda, M., Cabasés, M. À., Sabaté, M., & Strecker, T. (2020b). The deterioration of the Spanish youth labour market (1985–2015): An interdisciplinary case study. YOUNG, 28(5), 544–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308820914838

- Valls, F. (2015). El impacto de la crisis entre los jóvenes en España. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 54, 134–149. http://dx.doi.org/10.7440/res54.2015.10