Abstract

The paper explores the COVID-19 ontologies and experiences of children, youths and women in Ward 17 of rural Gwanda South. It argues that the locals have indistinct insights and perspectives on the pandemic. Most of them managed to conceptualize COVID-19 from a “realistic” and “fatalistic” standpoint. Adopting a mixed-method research design that inclines more towards a qualitative approach, data has been collected through document review that was validated with key informant interviews and questionnaire survey. Emerging from the study, the adaptation and responsiveness of youths has been blurred by lack of knowledge, indiscipline, lack of collaboration and inclusivity. Sustainability as an important element for disaster management in rural communities is obscurely being vitalized within the community. Furthermore, to ensure resilience COVID-19 responsiveness for children, youths and women within the locale has to largely depend on government, non-governmental and private structures. Therefore, the study concluded that institutions are the nucleus of health planning, in rural communities. Gwanda has limited health infrastructure, thus they are susceptible and vulnerable to disasters like COVID-19. The study recommends fostering of collaborations, partnerships, consortia, youth-driven; and women centered Volunteer Emergency Response Systems to ensure sustainability as well as strengthening of ward/village/district civil protection units or structures in the form of Disater Risk Reduction committees.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The effects of the global pandemic that has ravaged the whole world in the last few months are still unfolding in unbelievable ways. While the impact of the virus on global economy and its structural patterns of relations and connectivity are still a long way to be effectively figured out, one can at least safely conclude that the world as we know it has effectively changed. More importantly, the particular response mechanisms set up by governments to tackle the menace would also serve as a measure of the capacity, ingenuity and resilience of rural communities. While the impact of the pandemic is felt by everyone, it is known that the economic active group mainly youth and women are vulnerable. The outbreak has led to the disruption of the daily mode of living of communities around the world, which in turn leaves an adverse effect on every facet. This study contributes to the debate on knowledge, effective management and resilience of COVID-19 by rural youth and women.

1. Introduction

The past few years have seen an outbreak of a serious global health pandemic, Coronavirus 2019 (SARS-CoV). This has led to significant build-up of interest in public health matters by individuals, and institutions. The pandemic has disrupted every aspect of people’s lives in an unprecedented manner worldwide. While many of its implications, such as confinement-related psychological distress and social distancing measures, affected all in society, different age groups experienced these impacts in diverse ways. The pandemic impacted on the socio-economic livelihoods and well-being of a large section of the population in Zimbabwe. According to ZIMSTATS PICES report (2020). COVID-19 had far-reaching effects on the right to education and social well-being of children; health delivery system, which was already underfunded, undermining the right to health for many people. Affected millions of people who dependent on the informal economy and casual workers in the formal sectors, with women being the worst affected. Closure of informal economy businesses, market places and vending sites deprived them of their sources of livelihoods and incomes. There were high job losses in the retail and other service sectors, as well as reduction or disappearance of wages for most contract and casual workers.

The above findings were further cemented by Laetitia and Anushka (Citation2020) who posited that Covid 19 resulted in economic insecurity which have a global impact, pushing parts of Sub Saharan Africa towards its first recession in 25 years. The mounting financial burden faced by all countries puts progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal at risk as aid budgets come under pressure (Barbier & Burgess, Citation2020).

There has been an ongoing saying “we are all in this together” but beneath this togetherness lies inequality with women and girls shouldering a greater economic and emotional load. According to a survey done by Plan International (Citation2020) about the negative impacts of COVID-19 on lives of girls. Findings revealed that there were tensions at home, students felt lonely, they missed their schools and colleges, their friends and the easy freedoms of going out and about. Of which all these are crucial components of a young person’s academic, social and personal development.

COVID-19 also affected food consumption and nutrition security as households lost incomes, while food prices went up due to the inflationary shocks induced by the pandemic ZIMSTATS PICES (2020). Despite all this, the concept of COVID-19 has remained elusive. The outbreak and management of COVID-19 has been a seminal and topical issue around the globe. Social media have been coupled with myths and misconceptions regarding COVID-19 pandemic. This has resulted in the national and international governing bodies to be wary of the on-going situation, especially regarding the circulation of myths and misconceptions on COVID-19 (United Nations, Citation2020; WHO, Citation2020). The management of COVID-19 pandemic by rural children, youths and women has been blurry and inconclusive. Therefore, the need for engaging in research that can help inform the world and its governments about the realities within rural communities, with a goal to contribute in evidence-based sustainability in light of child-oriented, youth-laden and feminist public health promotion or governance.

In Ward 17 of rural Gwanda south, the outbreak of COVID-19 and the trends or issues surrounding the community response to it have appeared to be fundamental (Gwanda Rural District Council, Citation2020). Lessons can be drawn from the experiences of children, youths and women dwelling in this part of rural Zimbabwe, an area “prone” and “vulnerable” to disasters of different kinds, scope and nature (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2016; Gwanda Rural District Council, Citation2016). This region has been ravaged by a plethora of environmental and health hazards in the past, and it appears to be a significant case to consider as one evaluates the children’s, youths’ and women’s response to the COVID-19 scourge, most specifically from a formative standpoint. This is important for public and community health policy, planning and governance; both in the present and the future. Most importantly, the degree to which rural children, youths and women can be in the “state to act” in response to pandemics of any kind is likely to depend on the “ties and collaborative activities” that are in place prior to disasters. Such collaboration and linkage the rural children, youths and women have with some vital stakeholders, has to be evidently realized and noticeable even at the onset, course, peak and fall or drop of the pandemic or disaster. Collaboration among individuals, government institutions, and non-profit organizations can result in improved coping capacity, prospective and corrective disaster risk management among rural children, youths and women. The study is thus an exploration of how rural children, youths and women can develop the collaborative capacity to respond the COVID-19 pandemic, and manage recovery and sustainable development efforts. Most specifically, we focus on the structure of rural emergency knowledge and responsiveness, in particular the practice of collaboration and capacity building for COVID-19 resilience.

1.1. Broad aim

To assess the perceived COVID-19 knowledge and/or management by children, youths and women in rural Zimbabwe

1.2. Specific objectives

The study sought to:

Establish what the local children, youths and women know, think or say about the COVID-19 outbreak;

Identify the factors informing what the local children, youths and women know, think or say about the COVID-19 pandemic;

Ascertain how the local children, youths and women respond or manage to stay responsive and resilient amid COVID-19 era.

2. Review of literature

According to Dlamini (Citation2021) many countries from developing and developed economies reported an escalation in gender-based violence during the lockdown. France reported an increase of 30% of domestic violence cases since the lockdown; Cyprus and Singapore reported an increase in helpline calls by 30% and 33%, respectively, in Argentina emergency calls for domestic violence cases increased by 25% since the beginning of the lockdown.

In Canada, Germany, Spain, the UK and the USA, government authorities, women’s rights activists and civil society partners indicated increasing reports of domestic violence during the crisis, and/or increased demand for emergency shelter (UN Women, Citation2020).

In the same manner, UNESCO (Citation2020b) pointed out that, the pandemic affected every sector of the Zimbabwean economy and all sections of society with differential impacts depending on age group, gender, socio-economic status, geographic location. UNESCO further estimated that about 10 million more secondary school-aged girls could be out of school following the crisis aftermath impacts of COVID-19. The impact of school closures is likely to be felt most by the world’s poorest, who are least likely to have access to alternative distance learning.

The social and economic stress brought by COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated pre-existing toxic social norms and gender inequality. At the time when half of the world population was in lockdown due to COVID-19, the number of women and girls between ages of 15 and 49 had been subjected to sexual and/or physical violence perpetrated by an intimate partner (GBV) was no less than 243 million (UN Women, Citation2020).

According to a study carried out by Plan International in (2020) most girls across the 14 countries were not being able to go to school or university (62%), not being able to socialise with friends (58%) and not being able to leave the house regularly (58%). This explains the extent how inequality have placed women and girls in greater difficulties as they shoulder greater economic and emotional problems. As this might further deepen existing gender inequalities within their homes this reality therefore requires equal participation of women in decision making and ensuring gender lens in crisis mitigation and recovery policies (Mora Mora, Citation2020). The above view is further shared by African Union (Citation2020) which bemoaned that with the advent of COVID −19, pandemic that has spread to almost all its 55 Member States, might possibly reverse some of the gains that have been made in promoting gender equality, women’s empowerment and rights. Therefore as a result of the multi-dimensional impacts COVID 19 on women, across the globe it is therefore of critical importance that responses towards the prevention, containment, management and eradication COVID-19, take into account gender equality and women’s empowerment, so that women, youths and girls are not left behind which makes the case for investigation in this study.

In an effort to mitigate the outbreak of COVID-19, many countries imposed drastic lockdown, movement control and quarantine centres on their residents. However, effectiveness of these mitigation measures is highly dependent on cooperation and compliance of all members of society. The knowledge, attitudes and practices people hold toward the disease play an integral role in determining a society’s readiness to accept behavioural change measures in times of pandemics and disasters (Azlan et al., Citation2020). Adherence is likely to be influenced by the public’s knowledge and attitudes toward COVID-19. Chirwa (Citation2019 & Citation2020) lamented that, public knowledge is important in tackling pandemics. By assessing public awareness and knowledge about the coronavirus, deeper insights into existing public perception and practices can be gained; thereby help to identify attributes that influence the public in adopting healthy practices and responsive behaviour (Podder et al., Citation2019). Assessing public knowledge is also important in identifying gaps and strengthening ongoing prevention efforts.

WALPE report of (2020) in Chamunogwa (Citation2021) revealed that there were also gendered burdens of home schooling on parents, especially women, who mostly provide care for families and children. Children in female-headed families were affected because their mothers or female guardians had to spend more time engaging in informal activities to continue accessing income and support the livelihoods of their families without having time to provide home schooling for their children. Girls tend to be affected because they contribute to care work in most households due to the patriarchal nature of care work in which women are expected to provide care support for families this includes cleaning the house, cooking, fetching water to name just a few. The closure of schools meant that girls had to spend more time providing care support to families and less time engaging in home-based learning. This shows the “gendered inequality” impact of COVID 19 on the right to education. As a result of the multi-dimensional impacts, COVID 19 is having on women and girls who are the majority of the population in most Africa countries. It is therefore of critical importance that responses towards the prevention, containment, management and eradication COVID-19, take into account gender equality and women’s empowerment, so that women, youths and girls are not left behind which makes the case for investigation in this study.

3. Study area & methodology

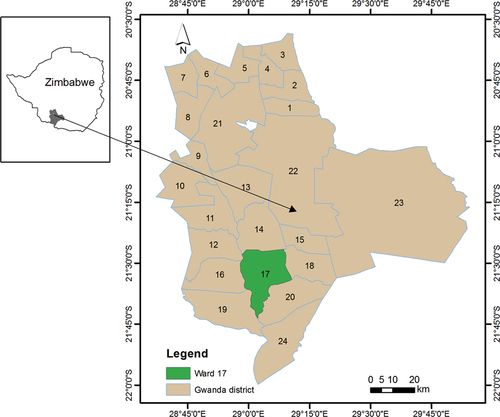

3.1. Study area map

See Gwanda ward 17

3.2. Methodology

A mixed method approach combining qualitative and quantitative techniques was adopted in this study because the two styles have different complementary strengths. Neuman (Citation2000) asserts that, a study adopting both methods is fuller and comprehensive as negatives of one method are negated by the positives of the other method. As a result, in this instance it did not only give the researcher means of achieving results but also boosted confidence in the end result. The study was conducted in Ward 17, Gwanda South, Matabeleland province, in Zimbabwe between March and August 2020. Due to resource and time, constraints the study sample was derived from 6 villages namely Humbane, Gohole, Magaya, Mnyabetsi, Marakong Fumukwe, which were randomly selected. Within the villages, probability random sampling was done with the aid of computer generated random number tables in the selection of respondents (Chitongo & Ricart Casadevall, Citation2019) the random numbers were generated using MS Excel 2010. The Raosoft sample size calculator (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html) was used to calculate the required sample size (Raosoft, Citation2020). The calculations were based on the assumption that the population from which the sample was derived were normally distributed. The confidence interval for the sample was 95%, margin of error was 5% and the response distribution was set at 50%. Based on the above calculation, the sample size was 361 respondents. According to ZIMSTAT (Citation2012) the population of Gwanda ward 17 is 5 955 that is 2 721 males and 3 234 females. Data was gathered through a researcher-administered questionnaire. Furthermore, purposive sampling was used to select 12 key informants’ comprising of community leaders, which included local female pastors from the mainstream churches, African Indigenous Churches, a female Sangoma, and a business woman among others were interviewed. Interviews were conducted using local languages best understood by respondents to avoid misinterpretation of questions. Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim to English. Interview summaries were written for each key informant interview (KII). Interview summaries were used to come up with a provisional coding framework, which was used to analyse qualitative data.

4. Findings & discussions

4.1. The demographic characteristics of the respondents

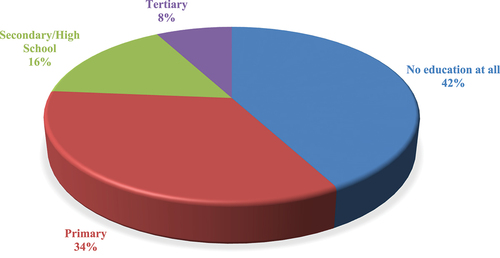

Sixty-three percent of the respondents interviewed were females whilst thirty-seven percent were males. Forty-two percent of household and key informant respondents had no education at all, 34% had attained primary education, 16% had secondary or high school education, around 8% had tertiary education (either college or university) respectively as shown in delspace;. It was very important to solicit COVID-19 data from both males and females, and draw conclusions from a comparative analysis of their experiences.

Researchers made sure that respondents interviewed had valuable and commendable experience in public health issues and were residents in the area for at least five years. This was so because, it has been assumed that if both the rural communities and the responsible authorities participating in this study could have grown up exposed to public health activities for the past five years or more, and they could have gained some reasonable experience about public health-related disasters or hazards of any kind, including the current COVID-19 pandemic.

4.2. COVID-19 knowledge and perceptions amongst the local children, youths and women!

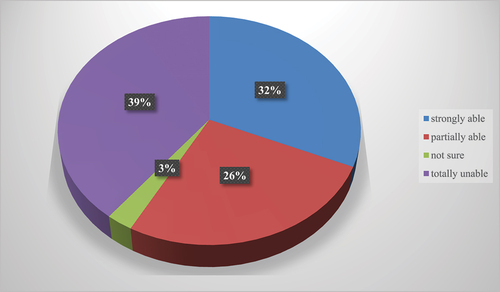

A moderate number of respondents were unable to give a general information about COVID-19. Findings show that about 39% of the respondents were unable, 32% were strongly able, 26% were partially able, and as low as 3% were not sure as shown in delspace;. This is a rather “blurred’ and/or “inconclusive” observation and testimony to the realities of how the local children, youths and women are informed on public health matters especially at a critical time of the COVID-19 scourge. The percentage scores of those who were unable and those who were strongly able are almost equal, with a slight difference of around 7%. Such a state of affairs makes the region highly vulnerable and fragile to hazardous events, as argued by Gilbert (Citation2020) that the effects of a pandemic and the responses should be better understood through a consideration of the more vulnerable members of society like children, youths and women. One can even argue to say those who mostly indicated that they are able to identify and outline the facts on COVID-19 are probably the most literate and professionals working on gender-sensitive platforms and institutions. The educational and professional background plays a fundamental part in the understanding of some phenomenal and catastrophic changes or experiences, some of which could have never been known and imagined before.

Figure 3. Ability/inability to identify and outline COVID-19 effects on women and children (n = 361).

The most predominant negative effects of COVID-19 were thus identified, established and generalized by the respondents. Most of the respondents mentioned that the social lives and relations of children, youths and women were disrupted since the outbreak of COVID-19. About 74% confirmed this, followed by 58% who argued that their religious lives and relations were dwindling, 42% pointed out that the economic lives and relations were at a dilapidating state, 34% opining that the traditional lives and relations of children, youths and women were distorted, and around 29% of “others” who had no idea or probably not willing to share and contribute anything child-oriented, youth-oriented or feminist as shown in Table .

Table 1. Possible negative effects of COVID-19 on the lives of women and children in order of significance (n = 361)

The disruptions, deteriorations and distortions in the lives and relations of the children, youths and women within the area under study were notable through children failing to go to school, play with peers, borrowing books and pregnant women failing to visit the maternal clinics, not engaging on their income-generating projects like poultry, knitting, clubs, and selling goods during cattle sales. More so children, youths and women within the locale were failing to attend church services same as their male counterparts. One female Key Respondent was quoted saying..

we are not happy at all. Our happiness as community women is eaten up by this pandemic and the restrictions associated with managing it. We really want our happy lives back … visiting other women to share constructive ideas to help us fend for our families. It’s really difficult when even our club meetings have been banned due to this virus.

This statement testifies to the fact that a “quality life” is that which is a “happy life”. It’s a life that is full of freedom, where the rights and wellbeing of the populace are observed and respected. In the case of COVID-19, rights are somehow limited. Their life and relations are dwindling and deteriorating. It is not clear though who they are blaming for such distortions is it men, government or other parties? It rather remains a “blurry” and “inconclusive” dialectic or way of finding the truth about the societal life challenges within the area under study, especially from a “feminist” point of view, under this COVID-19 scourge.

Relatedly, this could apply even to the situation faced by youths within ward 17 in rural Gwanda south as one young respondent said:

since we first heard of this pandemic, I have been living under the dark cloud of confusion and uncertainty. I do not know even what will happen next to me or my family, relative, friend or colleague. I am just confused. There is no life here. I do not even know if I will manage to go to university as I got a scholarship out of the country … but whom should I blame for this fate? If I do not manage to get into the plane and go oversees whom will I blame for that? I’m confused and I hate this pandemic and whosoever brought or created it with all my heart.

The statement above is a clear testimony of the sad realities of COVID-19 as children and youths have been negatively affected morally, socially and psychologically. Overall, the rural communities with a calibre of women and children like those domiciled in Ward 17 of rural Gwanda South, are most likely to be vulnerable and susceptible to destruction by disasters like COVID-19. Their exposure to hazards and disasters is risky and dangerous their coping strategies and/or abilities to resist and restrain from disasters remains highly questionable (Bankoff et al., Citation2004; Kapucu et al., Citation2013; Lindell et al., Citation2007; Makurumidze, Citation2020).

Findings indicated that most of the respondents in Ward 17 were of the view that they are few positive aspects that could be attributed to COVID-19 (84%); followed by 11% not being sure, 8% agreeing but minimally that there are positive attributes of the virus, and as low as 3% strongly agreeing towards that there are positive attributes of COVID-19. These results are testifying to the fact that most of the people within the geographical location under study have failed or are failing to identify and establish anything positive about COVID-19—to them this is total disaster. They have looked at the pandemic from a “fatalistic” point of view as discussed earlier on. This could be informed by the effects of other pandemics that have commonly ravaged the livelihoods within the area like Malaria and HIV/AIDS, as argued by the (Government of Zimbabwe, Citation2016; UNICEF, Citation2020).

4.3 Identifying and reviewing the institutions facilitating COVID-19 knowledge and/or perceptions amongst local children, youths and women!

The study also examined and documented the local communities’ level and degree of knowledge and/or responsiveness in the face of the COVID-19 disaster, as determined and informed by the existing community’s institutional structures, systems and platforms within the area under question. The community and institutional issues as provided or submitted by the respondents that possibly make the community under investigation to be “vulnerable” and at “high risk” in times of disasters, are appraised. The study gathers the structures and systems that are likely to enable or are enabling the responsiveness of the local children, youths and women in acting on the COVID-19 disaster, those that can exist as formal or informal frameworks or guidelines within their locale. The study thus presupposes that local children, youths’ and women’s assertiveness to act on COVID-19 is likely to be informed by the influence of a plethora of community and institutional factors.

The study sought to establish how the local institutions were considering and vitalizing COVID-19 response and management. The respondents confirmed this by arguing that they were not sure about the role of the institutions working in their disposal towards managing the virus. Thirty-nine percent (39%) of the respondents indicated that the institutions are minimally in considering and engaging in the child-centred, youth-laden and feminist management efforts; about 24% indicated that the institutions are strongly considering COVID-19 management efforts; 21% were not sure; and about 16% argued that the institutions were not considering and engaging COVID-19 management efforts at all. This information testifies to the fact that most of the institutions within the locale are not practically visible in this era of COVID-19, especially in light of the wellbeing or rights of children, youths and women though as argued by some key respondents, some are involved practically in the efforts to create awareness and knowledge about this pandemic. One Community Development Officer said:

some NGOs under Amalima USAID consortium have their officers moving around teaching about this pandemic to anyone, including the young people and women. I personally move around and make sure wherever or whenever I get in a household or business centre; I just share what I know about COVID-19. We also have pamphlets about this virus that we give to anyone whom we happen to meet.

The respondents were then asked about the existing programs or initiatives instituted by the different stakeholders within the community under study. This was a summative outline of the programs or initiatives meant to prevent and control COVID-19 within the locale. Findings have shown that, community-driven initiatives were the most predominant within the locale (92%); government-initiated programs (82%); faith-based organisations initiatives 68%; initiatives by NGOs (47%); initiatives from the private and/or local business partners (37%); and 32% for “other” variables including respondents being clueless and probably not willing to share as shown in Table . The community-initiated programs that dominated most of the respondents submitted by the majority of respondents included the “tippy tap” as a strategy to maintain cleanliness and hygiene, use of ash for washing hands, and eating lemons. The “tippy tap” that was placed on the gateways of most of the households and functioning, could however be identified and mentioned by other respondents as a government initiative and even the NGOs that were first instituted and implemented in the past during the times of Cholera outbreak. All this said, still the “tippy tap” becomes the most common and predominant initiative to facilitate and inform the local communities’ response to COVID-19 as impending disaster.

Table 2. COVID-19 prevention and control programs/initiatives as outlined in order of significance (n = 361)

The predominant government-initiated programs as outlined by the respondents included the occasional teachings about COVID-19 by the local authorities like the Ward Councilor, Village Heads and Environmental Health Technicians (EHT). These included lockdown and social distancing. However, some could argue that these are not teachings in the actual sense of teaching, but just talking about the pandemic, since even these local authority officials also seem to be not well-equipped and knowing much about the COVID-19 pandemic. A young Respondent said:

we are hearing some of our leaders around here, including health officials like the EHT, talking about this virus during funerals and distribution of food handouts. We cannot say they are teaching us. A good teacher is that one with vast and adequate knowledge of his or her subject matter, and we are seeing that our leaders and the EHT are just talking to us, though like us they do not have full knowledge about this shocking experience of our time.

Another young respondent was quoted saying:

… some of these health officials like the local Village Health Workers and Home Based Care givers are just silent and doing totally nothing as we face this terror and disaster. Maybe they do not know what to do and say about it …

The statements above are a clear testimony towards the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic is a shocking and devastating experience that comes to a society with “active but rather incapacitated leadership and community health personnel”. Their statuses as active leadership and workforce have been “halted” and “limited” by “incapacitation”. It is evident that they are strongly willing to participate and serve their communities as “responsible authorities and gatekeepers”—but are rather not fully equipped to do such especially during times of total disaster like this COVID-19 era. This makes the locally communities become more vulnerable, both physically and socially (Lindell et al., Citation2007; Moynihan & Landuyt, Citation2009; Gilbert, Citation2020). Gwanda Rural District Council (Citation2020) has further supported and strengthened the fact that most of parts or rural Gwanda south have good leadership and local authorities. However, they lack capacity to engage and act on some seminal issues and this was evidenced during this era of COVID-19.

The respondents have further indicated that most of the initiatives or programs pursued by the Church, NGOs and Private or Business entities, were largely those that are a repetition, retaliation and/or emphasis on the Community and Government ones. One local female pastor was quoted saying:

even though we are not congregating in our temple as usual, we use such platforms like WhatsApp groups to send and circulate messages on such initiatives like the “tippy tap” to make sure every church or non-church member uses this technique. Even the local NGOs are telling us about this initiative, some further giving us COVID-19 pamphlets. The local businesses are also not giving us anything particular during this era of disaster, but they have these “tippy tap” things in front of their shops and encourage us to wash hands and place our own in our homes. Some local stores have COVID-19 flyers and posters stuck at their shop windows where they encourage us to read for ourselves, and sometimes explain to us what is written and communicated there.

This statement shows that though NGOs, churches and private business players within the locality were proactive. This was done through explaining and strengthening on-going initiatives established by local communities and government platforms. This testifies to the notion that CSOs and Private entities, including the local businesses, can be very useful and vital players and actors in “inclusive” disaster management praxis (Pelling, Citation2003). Some local businesses can even fund community disaster programming (Gwanda Rural District Council, Citation2020; UNECA, Citation2020).

When further asked as to how much the respondents themselves are actively involved in the COVID-19 programs or initiatives outlined and discussed above, about 37% indicated that they are actively involved but minimally; 10% confirmed that they were actively involved; and about 6% argued that they are not involved at all. This was rather a difficult scenario to conclude. Why could a community existing under vulnerability and exposure to pandemics, with active leadership and workforce as argued earlier on, be so reluctant and hesitant to engage actively in the initiatives tailored towards addressing and mitigating disastrous issues? This makes the local communities more vulnerable when disasters strikes as their “ontological” views might come to play as they have different views and understandings of a disaster based on their different beliefs. They might be having different views and understandings of an event or disaster. Faith might come to play. Some could believe that they cannot do anything about the pandemic at hand. Only their God can intervene and stabilise things. This is a region with a vast population of conservative religious people who shun public health and education-oriented activities and issues (Gwanda Rural District Council, Citation2020; Makurumidze, Citation2020; UNICEF, Citation2015). However, this is not sufficient to stand as a strong and precise conclusion as to why a few people within the community under question could be engaging actively in some prevention and control programming for disasters like COVID-19. The observation made here has remained “inconclusive” as rural communities are not ready to face disasters; this is based on the “blurred” and “obscure” conclusions drawn from local ontologies and experiences.

The respondents further indicated that they are facing some challenges as they attempt or make efforts towards accessing and acquiring up-to-date information on the pandemic. A plethora of restraining factors could be prohibitive and not allowing for the acquisition, cascading and sharing of COVID-19 information within the locale. Ninety-five percent of the respondents indicated that, there have been misinformed and misled about the pandemic and this has been the greatest challenge towards getting up-to-date information on COVID-19. About 92% indicated that they are unable or struggling to interpret the broadcasted and cascaded COVID-19 information; 89% mentioned the lack of financial support from the local authorities or structures to pay for COVID-19 IEC services; 82% indicated that they cannot afford to purchase data bundles so as to access COVID-19 information; 68% mentioned shortage of smart phones to access COVID-19 information; 61% indicated the issue of poor network and lack of power supply for their gadgets; and about 11% were not sure or clueless about such challenges as shown in Table . These results show that the quality of IEC on COVID-19 is the most worrisome issue within the area under question. There appears to be poor IEC within the locale, coupled with poor local support systems and structures to help improve the situation. The communities are thus “vulnerable” in that context—they are misled and misinformed. This happens to be common with marginalised societies (UNDP, 2012; Makurumidze, Citation2020).

Table 3. Challenges associated with access to COVID-19 information (n = 361)

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusions and recommendations on the perceived COVID-19 knowledge by rural children, youths and women have been established in this study through the “dialectic” of the ontologies and experiences in Ward 17 of rural Gwanda south, Zimbabwe. Conclusions and recommendations are strongly biased towards what the local children; youths and women are saying, thinking and doing about the novel COVID-19 pandemic. To them, COVID-19 is a “real, tumultuous, torturous and fatalistic experience of their time”. Results have shown that rural children, youths and women “feel incapacitated to act” on disasters like COVID-19, due to a plethora of community-laden and institution-oriented factors that are “obscurely defined” and “most probably complex”.

As indicated by the respondents, issues like the past or recurrent disease outbreaks, morbidities and mortalities; fragility of public health system and economy; migration and mobility; geographical location; inadequate or poor resource allocation and distribution; and centralized governance systems, are the most critical and fundamental factors or issues to be considered in this era of the COVID-19 disaster. This implies that it is rather difficult to face and respond towards the pandemic without paying full attention or considering such fundamentals. These aforementioned factors and/or issues happen to increase the local communities’ vulnerability, susceptibility and exposure to hazards. These have included the lack of community and inter-organizational collaborative activities based on: community or individual readiness, emergency or disaster preparation, community and inter-organizational networks and systems, household or community capacities, organizational or institutional capacity, sustainable thinking and acting for disaster response and mitigation, community or institutional disaster coping and resilience, and the community and organizational adaptive capacity and/or responsiveness. Results have shown that the communities under question are lacking such critical factors. The study thus proposes for the establishment of “localized” child-centred, youth-oriented and feminist Volunteer Emergency Response Systems that should be “functioning” and not “moribund” in the face of pandemics. These systems should be “voluntary, community-driven platforms”. Volunteerism is fundamental in community development work. “Community-Based Disaster Volunteers” can actively steer up the spirit of the locals to stay alert and prepared for disasters like COVID-19, as volunteers have done in pandemics like HIV/AIDS. This derives from the respondents’ perspective on the need for locals to establish “consortia” with every child, youth or woman being active and existing within their locale in managing the COVID-19 disaster.

More research to inform and govern evidence-based approaches and programming for disaster management is needed and highly fundamental. The government and other partnering agencies should have a full update of what is happening in the rural communities. This therefore point to the dire need for the understanding of the localized child-oriented, youth-laden and feminist issues, concerns, insights, thoughts, perceptions and perspectives on disaster outbreaks and responses. In that case, informed decision-making and planning for disaster management can be instituted and implemented. Such research-oriented platforms are informing the need for “sustained partnerships, inclusivity and interactive partnering for resource child-oriented, youth-laden and feminist mobilization, planning and decision making” at the face of disasters like COVID-19.

In case of manning, controlling and supervising the “dangerous spots” at the face of disasters like COVID-19, the study opined for the development of “more realistic, people-driven and sustainable” techniques and strategies. For instance, in the case of water sources like boreholes and taps, the study proposes the establishment and implementation of a “modelling technique” tailored towards guiding, determining and governing the usage of boreholes in rural communities, be it in time of disaster or not—just to stay alert, prepared and ready to act. This technique has to “remain in place and functioning”.

The outcome is rather an “inconclusive” discovery—a template and blueprint that can guide and inform disaster thinking and/or interventions. It is our effort towards a “nuanced and/or refined rudimentary truth” established and discovered through the review of the child-oriented, youth-centred and feminist COVID-19 ontologies and experiences within Ward 17 in rural Gwanda south. It exposed and explored the importance of the understanding of “sustained collaborations and partnerships”, all premised around the identification of the community needs, issues, concerns, perceptions, insights and perspectives around making evidence-based decision-making and strategic planning for “sustainable, inclusive and active disaster resilience” in rural communities.

Henceforth, we conclude by making a call towards the “powering and strengthening of knowledge and readiness through the partnerships” cited in this study, and even those other researchers and stakeholders can think of and submit. We have attempted through this paper to make every relevant party or stakeholder to be aware of the fact that the children, youths and women dwelling in rural centres are sailing in one and the same boat with their urban counterparts in times of disaster or pandemics”. In the context of rural children, youths and women in light of disaster management, one has to understand the realities of “being rural”. Does being rural in our local contexts apply and tally with what implies in the world outside there, especially in the developed world? Is being rural universally agreeable and applicable? These are the questions that should be contextualized within the discourse of facing and dealing with disasters like COVID-19. Authorities like the Rural District Council should work hand in hand with the rural children, youths and women, local researchers and/or academics to ensure and facilitate a “research-founded” strategic response and planning towards promoting “active disaster resilience” within the communities under investigation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the local, regional and international structures or agencies for the available and accessible information or data that we were able to use in this study. These include the local government, leadership and/or institutions in Ward 17 of rural Gwanda south, Zimbabwe. We appreciate the support from the local Ward Councillor, who allowed us to conduct data collection within his area of jurisdiction, and the local communities and institutions that opened up and provide us with the most fundamental information sometimes beyond what we had expected or looking forward to hear or gather from the locale. It goes with recognition and appreciation the role played by the Lutheran Communion in Southern Africa (LUCSA), through its arms like the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Zimbabwe (ELCZ)’s Health Services Department and the Thusanang HIV and AIDS Project, for the unwavering support and encouragement we got from them as our responsible authorities for carrying out a research of this kind. We have always hoped that this collaboration and collaborating spirit shall forever exist and remain indelible. Conducting this study, especially through interviewing the locals was a highly risky and dangerous ‘voluntary exercise. On that note, we greatly appreciate the spirit of encouragement and motivation we got from respondents . Even during this current era of COVID-19, we managed to see ourselves through the indefinite societal discourses and conducted this study successfully, because of their encouragement. The philosophical, informative comments and contributions from upcoming academics like Mr Bonang Moyo, a teacher at Manama High School, can never go unnoticed and unappreciated. Above all, we give all the glory unto Him, the Infinite King, God! Leonard Chitongo would want to acknowledge SARChI Chair Sustainable Local Rural Livelihoods under the supervision of Prof B Mubangizi for his contribution to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nkosinathi Muyambo

Nkosinathi Muyambo is a research fellow at Tugwi Mukosi Multidisciplinary Research Institute, Midlands State University. His research interests cut through the discourses of African Indigenous theology, rural livelihoods development, health promotion, climate change and natural environmental management.

Philani Mlilo

Philani Mlilo is a Graduate research fellow, Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Great Zimbabwe University. He has strong interest on issues such as HIV&AIDS, disclosure, climate change, and public mental health.

Urethabisitse Mathe

Urethabisitse Mathe is a Programme Coordinator at the Thusanang HIV/AIDS Project, under the Lutheran Communion in Southern Africa and Evangelical Lutheran Church in Zimbabwe. His research and work are in the areas of public health and Community Development.

Leonard Chitongo

Leonard Chitongo is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, SARChI Chair Sustainable Local (Rural) Livelihoods, School of Management, IT & Governance; University of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. He has passion on issues, which affect human development.

References

- African Union. (2020). Responsive responses to covid 19. Addis Ababa.

- Azlan, A. A., Hamzah, M. R., Sern, T. J., Ayub, S. H., Mohamad, E., & Tu, W.-J. (2020). Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS ONE, 15(5), e0233668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233668

- Bankoff, G., Frerks, G., & Hilhorst, D. (2004). Mapping Vulnerability: Disasters, Development and People. London, UK: Earth scan. Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 7 (1), Article 51.

- Barbier, E., & Burgess, J. C. (2020). Sustainability and development after Covid-19 world development. 135, (accessed 27 March 2022). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X20302084

- Chamunogwa, A. (2021). The impact of COVID 19 on socio-economic rights in Zimbabwe. (Zimbabwe Peace Project)Accesed 13 March 2022 www.zimpeaceproject.com.

- Chirwa, G. C. (2019). Socio-economic inequality in comprehensive knowledge about HIV in Malawi. Malawi Medical Journal, 31(2), 104–16. https://doi.org/10.4314/mmj.v31i2.1

- Chirwa, G. C. (2020). Who knows more, and why? Explaining socioeconomic in related inequality in knowledge about HIV Malawi. Scientific African, 7, e00213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2019.e00213

- Chitongo, L., & Ricart Casadevall, S. (2019). Rural livelihood resilience strategies in the face of harsh climatic conditions. The case of ward 11 Gwanda, South, Zimbabwe. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1617090

- Dlamini, N. J (2021) Gender- Based Violence, Twin Pandemics to COVID-19, Symposium: COVID-19, Globalization, Heaiith Disparities and Social Policy, Critical Sociology 47(4–5) 583–590 https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520975465

- Gilbert, M. (2020). Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: A modelling study. The Lancet.com, 395.

- Government of Zimbabwe. (2016). Country report. The Government Gazette.

- Gwanda Rural District Council. (2016). Constituency Report, Zimbabwe. GRDC. Gwanda.

- Gwanda Rural District Council. (2020). Constituency COVID-19 Situation Report, Zimbabwe. GRDC. Gwanda.

- Kapucu, N., Hawkins, C. V, & Rivera, F. I. (2013). Disaster preparedness and resilience for rural communities. Journal of Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 4(4 215–233).

- Laetitia, W., & Anushka, S., (2020) India and Africa: Charting a post-COVID-19 future. Observer Research Foundation, Special Report No. 1 11, (June 2020), https://www.orfonline.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/06/ORFSpecial

- Lindell, M. K., Prater, C. S., & Perry, R. W. (2007). Introduction to emergency management. Wiley.

- Makurumidze, R. (2020). Coronavirus-19 disease (COVID-19): A case series of early suspected cases reported and the implications towards the response to the pandemic in Zimbabwe. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 53(3), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.002

- Mora Mora, A. (2020) African guidelines on Gender covid 19 in women’s live: Reasons to recognize the differential impacts. OASCIM

- Moynihan, D. P., & Landuyt, N. (2009). How do public organizations learn? Bridging structural and cultural divides. Public Administration Review, 69(6), 1097. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02067.x

- Neuman, W. L. (2000). Social research methods qualitative and quantitative approaches. Alyn and Bacon.

- Pelling, M. (2003). The vulnerability of cities: Natural disasters and social resilience. Earthscan.

- Plan International. (2020). Halting lives: The impact of COVID-19 on girls and young women, plan international, global hub dukes court Accessed 5 February 20222 https://plan-international.org/publications/halting-lives-the-impacts-of-covid-19-on-girls.

- Podder, D., Paul, B., Dasgupta, A., Bandyopadhyay, L., Pal, A., & Roy, S. (2019). Community perception and risk reduction practices toward malaria and dengue: A mixed-method study in slums of Chetla, Kolkata. Indian Journal of Public Health, 63(3), 178. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_321_19

- Raosoft sample size calculator 2020 http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html assessed 17 March 2021

- UN Women (2020), The shadow pandemic: Violence against women and girls and COVID-19, New York, USA. (Accessed 26 March 2022). https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-Library/multimedia/2020/4/infographic-ccovid19-violence-against-women-and-girls

- UNECA. (2020). Economic impact of the COVID-19 on Africa. (Accessed 15 June 2020). http://www.uneca.org

- UNESCO (2020a) Conflict-affected, displaced and vulnerable populations. COVID-19 education response: Education sector issue notes. Issue Note 8 (1). (accessed 27 March 2022). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373330

- UNESCO (2020b), COVID-19 impact on education. (accessed 27 March 2022). https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

- UNICEF. (2015). Children, youths and climate change in Zimbabwe.

- UNICEF. (2020). COVID-19 situation in Zimbabwe.

- United Nations. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: A global threat to humanity. The Secretariat. UN.

- WHO, (2020), Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) situation report-22. (Accessed 11 May 2020). www.who.int/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200211-sitrep-22-n-cov

- ZIMSTAT. (2012). Poverty and poverty datum line analysis in Zimbabwe 2011/12.