Abstract

Evaluation of research management is essential in higher education The Indonesian government regularly evaluates the research performance, as part of improvement the research ecosystem in higher education system. This study aims to analyze the problems in implementing research performance evaluations in Indonesian higher education system This study used a qualitative method with Focus Group Discussion (FGD). The participants invited were leaders of research institutes at universities that represent the best college clusters. We conducted a four-stage FGD to obtain the required information. The results are answered with recommendations to rearrange the assessment and implementation model that is adapted to conditions in Indonesia. The author believes that this research will not only contribute to the scientific development but also provide assistance to international readers with insight into the research evaluation system in Indonesia, as well as policy-makers in implementing a better research evaluation system.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Evaluation of research implementation and management is essential in structuring research in higher education. The Indonesian government has used the results of performance evaluations of higher education research institutions as the basis for determining the provision of incentives, grants, and program funding to universities, including research and development contracts in the internal budgeting process. Performance evaluation is not only a part of universities’ promotion, but can also help improve their performance and direct them to become world-class universities that support the improvements of the quality of life and the nation’s competitiveness. Therefore, it is necessary to rearrange the assessment and implementation model that is adapted to policy and conditions in Indonesia.

1. Introduction

The current policy-based measurement method is a vital factor in supporting the achievement of national research policy targets. Different objectives and policies of stakeholders, who adopt a unique research performance evaluation perspective, affect the dimensions of performance evaluation (Abramo & D’Angelo, Citation2015), including factors that prove significant for stimulating innovative activity in one country, which may not be at all effective in countries with other economic and cultural determinants (Karpińska, Citation2020). It is closely related to the term performance that Armstrong (Citation1994) conveyed as a result of work that has a strong relationship with the organization’s strategic goals, customer satisfaction, and contribution to the economy.

The Indonesian government has made efforts to increase the productivity and relevance of research both in universities and research institutions (Ristekbrin, Citation2021), which is in line with the definition of performance according to Kamble and Wankhade (Citation2017) as one of the main factors that affect productivity. Another effort of the Indonesian government is to increase the contribution of science and technology development to national development, including in solving social problems in society. It is encouraged through collaboration between universities, R&D institutions, the business sector, and other stakeholders so that research can be utilized by industry and contribute to the economy and national development. Based on this policy, research output is directed not only to academic purposes or to produce inventions but also to economic and social benefits in the form of commercial products or other outputs that can help solve societal problems.

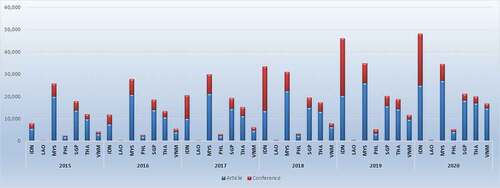

Recently, the ecosystem that supports the research and innovation sector in Indonesia has become conducive, so that the output produced has significantly increased (Ristekbrin, Citation2020b) amid differences in the situation among Southeast Asian countries in the ease of conducting research, especially in field research (Morgenbesser & Weiss, Citation2018). One of the increases in output achievement is presented in the figure , comparing the achievement of publication output among several ASEAN countries. The improvement of the number of Indonesian article publications at the ASEAN country level is the fastest growing. However, some of the publications were still published in the proceedings, which shows that the quality still needs improvement. This condition is inversely proportional to other ASEAN countries which have a higher percentage of articles in journals than proceedings. For Indonesia, this is important, in which publication in reputable journals is one of the assessment variables for lecturer careers listed in the Minister of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia Number 92 of 2014 regarding guidelines for performance assessment implementation for lecturer career. However, the quality of research outputs in Indonesia still needs to be improved, with one of the strategies by encouraging competition between universities through a performance appraisal system that is per the global rating assessment system.

Higher education, is one of the research institutions with the largest science and technology human resources in Indonesia and has big contributed to research outputs target achievement in Indonesia over the last five years. Higher education is one of the research institutions with the largest science and technology human resources in Indonesia and has big contributed to research output targets achievement in Indonesia for the last five years. According to the data from the Forlap PDIKTI system—the lecturer data information system—in February 2020, there were 4,667 with 920 academies, 325 polytechnics, 2,517 high schools, 237 institutes, 634 universities, and 34 community academies (Dikbud, Citation2020). There are 296.040 lecturers from all higher education, consisting of 207.586 lecturers with master’s degree backgrounds and 42.825 lecturers with doctoral degrees.

With this very significant contribution, the priority of improving the quality of research in higher education should be the government’s attention. Performance Evaluation is one of the supporting data not only for the government in preparing evidence base policies, but also for officials within the institution. It is important for an institution to think about its mission and goals, how to measure its internal performance and determine its performance indicators that need to be adjusted (Ball & Wilkinson, Citation1994). This information has also expected to support research institutions in making the right decisions regarding policies, programs, and funding. Therefore it can accurately allocate funds according to their needs.

This significance underlies the author’s curiosity to evaluate the implementation of research performance measurement in universities in Indonesia.

2. Performance evaluation measurement

Evaluation of research implementation and management is essential in structuring research in higher education. The benefit for the university being in a high ranking is the government’s trust that views the competitive status of the university (Hazelkorn, Citation2008).

The government prefers higher-performance universities in an education or research project, as evidenced by the government’s support through funding to improve the quality of teaching and research. Higher education ranking results are a source of comparative information for various stakeholder groups, which can influence policies in higher education and motivate them to be better in all aspects (Feranecová & Krigovská, Citation2016), thus improving higher education institutions’ performance (Söderlind & Geschwind, Citation2019).

Çakır et al. (Citation2015) compared several university performance evaluation systems, stating that the selected indicators are based on their respective interests. An overview of the measurement systems can be seen in Table .

Table 1. Condition of several national ranking system

The Indonesian government has used the results of performance evaluations of higher education research institutions as the basis for determining the provision of incentives, grants, and program funding to universities, including research and development contracts in the internal budgeting process (Dikbud, Citation2013). Additionally, research fund management institutions, such as the Indonesian Endowment Fund (LPDP), also use university rankings to provide research funds to universities with better performance, through the invitation of RISPRO scheme (LPDP, Citation2018). Previous studies have shown that the United Kingdom (Ball & Wilkinson, Citation1994), Sweden (Söderlind & Geschwind, Citation2019), Malaysia (Tahira et al., Citation2015), and Thailand (Siripitakchai & Miyazaki, Citation2015) carried out similar policies.

To acquire good measurement results (Dixon & Hood, Citation2016) recommend the following three conditions: the ranking can discern the institution being evaluated based on the indicators used; Stable rating instrument; the evaluation is not only beneficial for the Institute but also for the wider community. While Sizer et al. (Citation1992) explained that there are five performance indicators in the measurement: Monitoring aspect, which measures the continuous assessment of a program, institution, or system; Evaluation aspect, which looks at the achievement of goals and objectives; Dialogue aspect, as a basis for communicating concepts and goals, so that we have the same perception of policy; Rationalization aspect, where performance indicators can encourage rational and coherent policy-making; and The aspect of resource allocation, which becomes the basis for resource mapping for resource strengthening.

We summarized some of the performance assessments presented in Table , while Meng and Minogue (Citation2011) stated that there are several performance evaluation models that are more widely accepted and more effective than others, namely Key Performance Indicators (KPI), Balanced Scorecard (BSC), and Business Advantage Model (BEM).

Table 2. Several performance appraisal model

KPI is widely used in global and national performance evaluation models, and is a guideline to divide for universities (Azma, Citation2010). Azma stated that in the 1970s, the US Board of Education had started designing national indicators to compare universities, including the system for determining PT ratings by the US Board of Education.

The indicators of the higher education performance measurement system used in the previous research were: changing environment, development of the nature of university activities, competitiveness, and changes in the management system (Balabonienė & Večerskienė, Citation2014). Meanwhile, Tijssen and Winnink (Citation2022) stated that Developing quality criteria and performance indicators of local excellence can encourage researchers to contribute to socio-economic development and innovation.

This means that indicators are crucial in measuring performance, and the indicators in each national measurement system are unique (Çakır et al., Citation2015). The performance measurement model used is based on the measurements of research performance indicators that comply with the aims and objectives of the performance measuring institution. The performance measurement process is regarded as a key element of strategic management and can identify gaps between the current situation in the organization and the level of excellence with the proposed objectives of strategic planning and the use of indicators.

3. Evaluation of research performance in Indonesia

The Ministry regularly evaluates the performance of the Research Management Institution, to improve the research ecosystem in higher education. Through a system called simlitabmas, the evaluation produces outputs in the form of four university groupings, namely the Mandiri, Utama, Madya, and Binaan clusters (Dikbud, Citation2013).

The Mandiri Cluster is a group of universities with the best performance. This group is considered to have implemented a quality assurance system in research management so that it has superior research resources and very high research productivity with an international reputation. Meanwhile, the Binaan cluster has the lowest performance, and just starting to arrange resources in conducting research. Utama and Madya clusters are between Mandiri and Binaan clusters, in which the Utama cluster already has a good research management system but has not produced many research outputs with an international reputation, and the Madya is a group consisting of universities that necessary to increase the capacity of resources and research management.

Statement of the determination of universities in the group based on the results of the evaluation. The evaluation begins with data input from each university in the period determined by the Ministry. Experts assigned by the Ministry verify all data collected in the research performance database and declare it valid if the data is complete and the supporting documents required are under the provisions

Four aspects were used as the basis of appraisal of college research, including research resources, management, output, and revenue-generating (Dikbud, Citation2013). The indicators of the four aspects include the number of researchers, research funding, facilities, institutional, standards, publications, procedures, intellectual property, textbooks, and research contracts. The indicators used in the evaluation process have not changed since the first evaluation conducted in 2010 until the last evaluation in 2019. So 2022 is a good time to adapt and adjust the indicators assessed. The measurement of the performance of research institutions in higher education is carried out every three years, beginning in 2010 with a performance assessment in period 2007–2009. The last evaluation was in 2019, assessing the period 2016–2018. The Table shows the results of performance measurement in four periods.

Table 3. The cluster of Indonesian university on research performance

The latest ministry policy is different from the existing measurements evaluating the performance of Higher Education Innovation, where there are four components to be evaluated on the aspects of policies, institutions, networks, resources, and results of innovation. This measurement determines which universities have not led toward research and innovation, so that the Ministry can take the policy to accelerate downstream research (Ristekbrin, Citation2020a).

4. Research design and methods

The purpose of this study is to investigate the problems that arise during research performance evaluation in Indonesian higher education institutions. The research questions are:

What are the general problems and the current issues related to the implementation of performance measurement in research aspects?

What are the current issues related to the implementation of the measurement?

What indicators may need to be used as a basis for measuring the current policies and conditions?

What aspects of innovation might affect the evaluation of research performance of institutions in accordance with government policies?

This research employs a qualitative research method based on the efforts to obtain in-depth information on data, with a thematic approach. Problems that arise during the evaluation of research performance are interpreted using content analysis (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016; Weber, Citation1990).

The method chosen is focus group discussion (FGD) with many people to obtain in-depth information from several individuals simultaneously (Macdonald & Headlam, Citation2008). We conducted four stages of FGD to obtain information on the objectives of this study. Each group consists of 6–10 participants (Cooper & Schindler, Citation2014) from higher education research and innovation institutions with different characteristics based on the results of measuring higher education performance in the latest period. The selection of the set of higher education institutions is based on the following criteria: (1) it is located in the same country, (2) it has presented a diversity of universities, and (3) universities are in the development phase (Bosch & Taylor, Citation2011; Diezmann, Citation2018). We invited participants from Mandiri and Utama clusters (Table ). Participants were leaders of research and innovation units at public or private universities, and we also involve polytechnics.

Table 4. FGD participant criteria and code

The procedures carried out at each stage of the FGD are as follows (Cooper & Schindler, Citation2014; Creswell, Citation2014; Macdonald & Headlam, Citation2008):

Meetings have been held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic;

The discussion in the FGD has been recorded;

The FGD began with an introduction of the facilitator and the informants;

The facilitator starts the discussion by delivering an introductory material for the discussion, in the form of the background and objectives;

Informants convey their experiences or opinions; and

The discussion has been recorded for transcripts.

We analyzed The FGD results using content analysis,, by systematically evaluating the symbolic content of the recorded and transcribed results. The transcribed FGD results were encoded into similar content categories, and then relational and conceptual analyses were conducted by examining the relationship between concepts in the text (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016).

As a means for addressing ethical challenges in FGD and analysis, where there are three main issues: consent; confidentiality and anonymity; and the risk of harm (Sim & Waterfield, Citation2019), we take several steps. We adopted a strategy by conducting an approval process for participants at the briefing session. Then we also coded the participants for data presentation and analysis to maintain confidentiality. While the third issue is not related to the topic in this study

5. Result and discussion

5.1. Policies and general issues

There are seven issues related to the policies and general problems that are often raised in the four stages of the FGD, as shown in figure . These issues are the indicators used, the heterogeneity of universities in Indonesia, unclear guidelines and their socialization, the verification and validation process for data use, the career path of lecturers, the benefits of evaluation, and the use of assessment instruments.

Most participants stated that the performance measuring must be adjusted to the measurement of the main performance indicators of universities, which have been set by the government. The assessment components currently used in simlitabmas still use the old system, so it is necessary to adjust to the new indicators that are adapted to the relevant policies and issues, as well as diverse universities in Indonesia (Ball & Wilkinson, Citation1994; Tognolini et al., Citation1994; Vernon et al., Citation2018).

The issue of heterogeneity in higher education becomes important. Chigudu and Toerien (Citation2018) stated that diversity must be regulated to produce better performance. For example, the role of foundations in private universities related to is very significant in achieving the research output. The results of previous studies show the importance of the support of private university owners in improving the quality of research (Javed et al., Citation2020). Existing performance appraisals do not take this issue into account.

The issue of socialization of performance measurement implementation was also raised at the four stages of discussion. To prepare performance measurement, it is necessary to socialize the details of indicators and the effect of each point (Tognolini et al., Citation1994). Informative technical guidance is clearly needed since it is based on performance evaluation. A lot of data were invalid, maybe due to a lack of clear information. Data entry should be done accurately and completely, accompanied by the necessary evidence. If the information on how the filling process is not obtained by the operator correctly through technical guidelines, the possibility of invalid data will be higher. So the improvement and dissemination of the guideline are very necessary.

Another issue is the review process, which must be more thorough and precise, including how to capture the ethics behind the numbers so that the qualitative measurement is clear. Additionally, the results of the validation of performance assessments carried out in the previous period can be submitted to the assessed universities so they can determine the shortcomings and treat them as a basis for future improvement (Sizer et al., Citation1992; Söderlind & Geschwind, Citation2019).

On the other hand, there are differences in the perspectives of lecturers, university management, and the government. From the lecturer’s perspective, innovation is related to the change in the teaching workload, adding research, or more innovation. It shows that there is injustice in the assessment of individual performance in advancing the career of lecturers because the current regulations do not place a large portion of the innovation aspect in the career development so that there is a statement that innovation is not supported by lecturers but only the requests of the leaders of higher education institutions. The evaluation of research performance at research institutions in universities in Indonesia had a significant positive impact, including motivating researchers to produce better outputs (Feranecová & Krigovská, Citation2016). However, an evaluation will be more contributive if it was associated with performance-based funding. Therefore, evaluation quality should be maximized (Favero & Rutherford, Citation2019; Hazelkorn, Citation2008; Layzell, Citation1999; Sizer et al., Citation1992).

A topic of the discussion is that it is necessary to see how supportive the performance measurement is in improving the quality of higher education, especially by considering how relevant the national indicators are to the parameters used by global performance-measuring organizations. The performance evaluation that culminates in a national ranking is expected to be able to direct world-class universities that support the improvement of the quality of life of the community and national competitiveness. This is mainly to improve the quality of higher education, which can be measured from the results of the assessment. Many activities that have a competitive euphoria culminate in how to focus on having a better ranking or reputation than others. And in fact universities are competing to improve their performance to become a world-class universities while providing information to the public regarding their quality and position. Therefore, it is necessary to be transformed into an attitude pattern of how the universities’ ranking is more contributive in providing solutions to the nation’s problems through, research and innovation in representing realistic things.

Performance evaluation is also a part of college promotion (Feranecová & Krigovská, Citation2016). However, evaluation could be biased, because, before the mapping of conditions in universities, there were already universities with a high public trust, so those with good quality would be affected by the evaluation results. However, in principle, the evaluation results are essential in conveying the position and quality of higher education institutions to the public.

However, some problems can create confusion among universities due to the new policy for measuring innovation performance. Some of these instruments can be carried out in an instrument, which consists of aspects of supporting research, innovation, and community service (Tognolini et al., Citation1994).

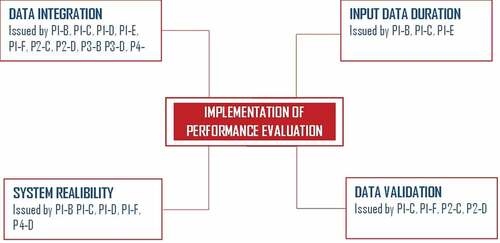

5.2. Implementation of performance evaluation

figure presents the most frequently discussed issues in the implementation of performance evaluation. FGD participants discussed many things related to data input time, validation process, system reliability, and data integration.

Data integration for similar variables from multiple evaluation systems will eliminate duplication of work and make it more effective. Synchronization is needed from the evaluation unit manager in the ministry discussing this issue. Data from institutions need to be collected at the same time and then used separately. One solution is to do a single entry, a multi-purpose internal university that emphasizes increasing data consolidation. Data interconnection is also one of the issues raised. Another problem related to data integration is that many criteria in the system are irrelevant to various policies related to lecturers.

The more parameters used, the more data are needed so that they are more representative of valid research performance (Dixon & Hood, Citation2016). This will be supported if it is associated with the capabilities of the information system required by the user. This means that the data entered are very important to be transferred into information and decision-making through a reliable system. One of the solutions is a web-to-web-based system that allows the system to be integrated. If assessment parameters are added to the evaluation instrument, there are consequences for improving the system to be able to facilitate this. It is difficult to determine a platform that can be accepted by all institutions, especially if it is connected to other related systems.

The performance evaluation must be accurate in providing maximum performance support (Meek et al., Citation2005). The current evaluation uses a data input mechanism that takes more time, while the filling period is limited so that operators in institutions focus on the filling process. Thus, the operator’s role can be different from the actual conditions. This includes clarity of the charging mechanism scheduling. This mechanism needs to be improved to increase data validity by no longer limiting data entry at certain times as if there was a data entry competition—currently, research performance is determined by physical evidence uploaded to the system, so some of data are declared invalid. Participants recommended that the input data are updated at any time, thus simplifying the data management. Filling in data entry and regularly and continuously will map the performance conditions of the university to be more realistic.

Despite the many invalidities due to input errors, the results of the validity process are valuable information for universities as input and improvements in the future. The information must also be shared with clear criteria standards so as not to raise questions from the university.

5.3. Performance evaluation component

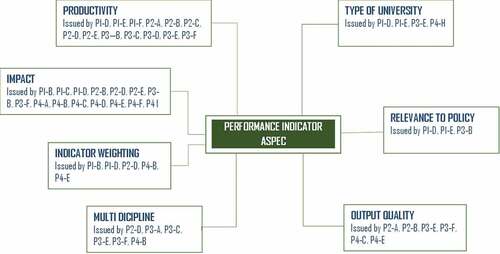

Regarding the third research question on the performance appraisal component, several issues were raised in the FGD, such as productivity assessment, impact/benefit, weighing indicators, interdisciplinary, output quality, policy relevance, and the type of higher education, which is illustrated in figure .

Currently, performance evaluation is measured by the cardinal size of the number of specified data indicators. It is unlikely that small universities will have better evaluation results than larger ones. It makes the results of the performance appraisal less suitable for the conditions. It is necessary to arrange parameters or weighting related to productivity aspects (Avanesova & Shamliyan, Citation2018; Dundar & Lewis, Citation1998; Marisha et al., Citation2017; Ramsden, Citation1999) because many small universities are dissatisfied with the assessment result. Productivity can be measured through the ratio, for example, the ratio of the number of lecturers with a doctorate to the total lecturers or the number of funds allocated to research, compared to the total funds of the university or the ratio of citation count to the number of publications (Diem & Wolter, Citation2013). Weighting the difference in the size of a university can also be an alternative to measuring performance.

The FGD participants agreed that the existing measurement instruments are good, but it was necessary to review the suitability of the indicators with the objectives and needs. In developing future indicators, it is necessary to consider aspect of long-term impact of a research as an assessment indicator, so to the instrument can measure the contribution of universities in providing solutions to the community’s problems. Many kinds of research and innovations have been carried out, such as those applied to the community through community service, which produce social impacts, and those used by the industry (economic impacts), which produce policy recommendations (Avanesova & Shamliyan, Citation2018; Balabonienė & Večerskienė, Citation2014; Zhang & Wang, Citation2017).

Performance evaluation can encourage higher education institutions that have not entered the QS list or other international measurements to adjust their indicators. As well as how the adjustment towards The Tridharma aspect (teaching, research, and service society) which is the primary mandate given to lecturers.

Research results can be optimized not only by managing the number of publication indicators but also by students involved, administrative officers utilized, the number of assets, and the optimization of research spending, as well as the current and future collaborative partnerships (Wood, Citation1990). Indicators of intellectual property need to clarify the definition used. Meanwhile, revenue-generating parameters require measurements of 1) work contracts; 2) research results from business unit; 3) business unit revenue. As for the research management parameters, the definition of variables in a study program needs to be clarified.

Participants also conveyed other issues related to the weighting of indicators in the measurement criteria related to the components in the related parameters. By categoring these indicators into several groups, the weighting become crucial. The assessment can be used as a reference for universities to improve quality, so universities can be considered as organizations with an open system that converts inputs into outputs. In this case, the categorization of indicators in the assessment can be in the aspects of input, process, output, outcome, and research impact (Abramo & D’Angelo, Citation2014; Brown & Svenson, Citation1988; Çakır et al., Citation2015; D’Abate et al., Citation2009; Dill & Soo, Citation2005; Hermanu et al., Citation2021; Savithri & Prathap, Citation2015; Schroeder & Goldstein, Citation2016).

Research collaboration is a parameter that should be considered (Bonaccorsi & Secondi, Citation2017; Eduan & Yuanqun, Citation2019; Hill, Citation1995; Sabah et al., Citation2019), not only from the aspect of the number of collaborations but also regarding the heterogeneity of research fields. Assessment of the collaboration aspect is also something that is missing in the existing performance evaluation process, so it needs to be deliberated as part of the research performance assessment The strength of this multidisciplinary network can accelerate innovation (Aldieri et al., Citation2019; Kobarg et al., Citation2017; Okamuro & Nishimura, Citation2012; Tseng et al., Citation2018). It is impossible to match the productivity between the fields of the Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Faculty of Engineering, compared to the Faculty of Social Sciences (Abramo et al., Citation2014; Prathap, Citation2016; Sabharwal, Citation2013), with a coordinator who is able to communicate and connect various fields of science, education, and the role of academic institutions in increasing interdisciplinary cooperation (Parti et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is necessary to rearrange assessment instruments that consider the differences across scientific disciplines.

The output quality is also an aspect that has not been used in an existing assessment indicator. The system does not distinguish the quality of published in various journals, or other quality output quality measures like patents. There is no difference between patents that have been granted or those that are still registered. It needs to be formulated in comprehensive guidelines, including how to consider research results used by the industry as assessment indicator.

The indicator component is different from the enumerator. It does not mean if, for example, an assessment indicator is the number of citation publications, people compete to cite each other. Indicators become intermediate data showing something else. With the two ministries supervising the university, it becomes challenging to compile an instrument containing indicators that are in line with the policies of the two ministries.

Moreover, with a large number of universities in Indonesia, varying both in terms of capacity and trust, it is possible to find discrepancies. There could be indicators that are not even a function of a university. It is necessary to consider the division of roles in higher education, either as a teaching or a research university. Performance appraisals are tailored to their respective roles.

5.4. Innovation

The existing assessment instruments is not per the latest government policies, especially in term of measuring the impact of research that can contribute to the society. So it need a breakthrough in including these aspects, For example, the impact on the society and the economic development. figure shows that issues in the innovation aspect are regional and environmental, economic, social-developmental, and related to capacity-building for lecturers.

Universities need to contribute to the community and the surrounding environment. The long-term impact of research is measured by the outputs and outcomes of research that has been used by society, industry, or other stakeholders (Avanesova & Shamliyan, Citation2018; Balabonienė & Večerskienė, Citation2014; Zhang & Wang, Citation2017). This includes transforming research results into something challenging when applied to the world of teaching, local government, MSMEs, and the business world.

Issues that are raised in the innovation aspect include standards for evaluating innovation performance. In the current measurement of innovation performance, there is a wedge in the measurement of research performance even though the perspective is different so that these parameters can still be entered. However, what needs to be emphasized in the context of the innovation.

Research performance must be able to measure the impact of innovation on the economy and society, as well as on how universities can package patents into patents that are granted in performance appraisals. Indicators related to research results or breakthroughs that generate large amounts of money (economic impact) need to be included in the assessment (Ahmad et al., Citation2015; Alstete, Citation2014; Hannover Research, Citation2020). Although many innovations have been applied either directly to the community through community service or to some research results used by industry, it is necessary to emphasize the context of the extent to which downstream can be categorized as an innovation.

FGD participants have raised the issue of the importance of university involvement in research-based regional development planning. This is an opportunity that universities must take to focus on the potential of their respective regions and thus contribute to regional development planning. It needs to be classified differently in performance evaluation (Javed et al., Citation2020; Reichert, Citation2019).

Technology transfer can be designed to drive more valuable innovation in a holistic sense, including creating economic and social value, particularly in achieving the core objectives of the missions of the three universities (Madl et al., Citation2021). It has been argued that innovation has been accepted by the industry or society and does not have to have patented or commercialized results. Not all innovators want to commercialize their innovations, but some are dedicated to the benefit of society. As social research lags in the context of innovation, the term innovation has become more dominant in engineering, medicine, and the natural sciences. How the term innovation can become a holistic unit, between social sciences and humanities and others, is yet to be seen, which is why it is necessary to approach the humanities social research community so that they can enter various other fields. Especially to encourage technological progress, not only aspects of the natural sciences but also social sciences that have not been touched much

The downstream process is not only related to commercialization but also to how it can be carried out upstream. This is especially true with the national policy regarding “Merdeka Belajar Kampus Merdeka”, an emancipated learning program where students master various disciplines useful for improving their capacity (Dikti, Citation2020). This includes developing strategies so that publication results are implemented in the learning process, or developing networks, such as inviting industry to science technology parks in universities so that the downstream process can involve students. Another form of downstream linkage is incorporating research findings into community service. A new measurement model is needed regarding the aspects of lecturer self-development. The perspective is that the lecturer conducts research, which results in a role in the company, then returns and provides feedback to the campus (D’Abate et al., Citation2009).

6. Conclusion

This paper investigated the problems that arise during research performance evaluations in Indonesian higher education institutions. This includes analyzing general issues in the implementation of previous performance evaluations to technical matters such as the measurement process, indicators, and other problems that have arisen due to the incompetence of research management institution officials in conducting evaluations.

We designed this study to obtain input on whether the recent performance evaluation of research institutions is in line with the government policy and expectations of higher education institutions. The answers to the research questions related to aspects of general issues, implementation of the measurement, indicators used, and aspects of innovation are as follows.

The measurement of existing institutional performance evaluation model is based on measurement based on indicators of research/innovation performance indicators that are determined in accordance by the aims and objectives of the performance measuring institution. Therefore, it is highly expectation that through a good system and the right indicators, performance measurement evaluation process can identify gaps between the current condition and ideal ones to develop strategies for achieving higher education goals. Moreover, it is recommended to adapt the performance appraisal instruments to the current conditions through further research to prove the effectiveness of combined instruments. In the implementation aspect of performance evaluation, follow-up discussions are needed to integrate data and improve information systems and implementation mechanisms. Adjustment of the existing performance appraisal indicators with the policies and expectations of universities is another consideration, both in terms of the type of indicators, weighting, and factors related to the aspects of innovation, such as economic, social, regional, and environmental development impacts, as well as the impacts on capacity development.

Performance evaluation is not only a part of universities’ promotion (Feranecová & Krigovská, Citation2016) but can also help improve their performance and direct them to become world-class universities that support the improvements in the quality of life and the nation’s competitiveness. Therefore, the author’s curiosity regarding whether it is necessary to revamp Research Performance Evaluation Instrument of Research Institutes at Indonesian universities is answered with a recommendation to rearrange the assessment and implementation model that is adapted to conditions in Indonesia.

We believe that this study will not only contribute to the scientific development. But also assist international readers with insights regarding the research evaluation system in Indonesia, as well as policy-makers in implementing a better research evaluation system.

Some aspects that need to be targeted by them in needs analysis to remodel research evaluation systems include government policies, users, business processes and plans, problems and solutions, and equipment, as well as university goals. These are to support the process of research performance evaluation, starting from planning, technical and personnel preparation, data collection, analysis and evaluation, result feedback, and use of evaluation results.

With its various shortcomings, we also hope that there will be further comparative studies, as well as more developed performance measurement models in accordance with the Indonesian conditions. Such as an inventory of parameters that affect research performance as the basis for developing research evaluation models, deeper exploration of technical problems in the field, and even comparative studies of models applied to other countries with similar characteristics.

Correction

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Diana Sari

Adhi Indra Hermanu is a Ph.D student at the Department of Management and Business, Faculty of Economics and Business, Padjadjaran University, Indonesia and works at the Ministry of Research and Technology/National Research and Innovation Agency. He received a master’s degree from University of Indonesia. He is Interested in research management and policy and higher education management and policy. Orcid Id 0000-0002-4034-5906

Diana Sari, SE., M.Mgt, PhD. is an associate professor in the Faculty of Economics and Business, Padjadjaran University. She received her Ph.D degree from Monash University, Australia with an interest in Management. He is also the Director of Innovation at Padjadjaran University. Orcid id: 0000-0002-2984-3605.

Dr. Mery Citra Sondari is an Associate Professor in Department of Management and Business, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Padjajaran, Indonesia. She received a Doctoral degree from Bandung Institute of Technology and a master degree from Padjadjaran University. She is interested in Human Resources and Organizational Management. Orcid Id 0000-0003-0503-3605

Dr. Muhammad Dimyati is an Associate Professor in Department of Geography, Faculty of Mathematic and Natural Sciences, Universitas of Indonesia, Indonesia. He was a Director General of Research and Technology Development strengthening in Ministry of Research and Higher Education. He obtained his Doctoral and Master degree from Kyoto University. He interested in Research Policy, Remote Sensing, GIS and Modelling. Orcid Id 0000-0003-4703-4227.

References

- Abramo, G., & D’Angelo, C. A. (2014). How do you define and measure research productivity? Scientometrics, 101(2), 1129–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-014-1269-8

- Abramo, G., & D’Angelo, C. A. (2015). Evaluating university research: Same performance indicator, different rankings. Journal of Informetrics, 9(3), 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2015.04.002

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Di Costa, F. (2014). Variability of research performance across disciplines within universities in non-competitive higher education systems. Scientometrics, 98(2), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1088-3

- Aggarwal, A., Sundar, G., & Thakur, M. (2013). Techniques of performance appraisal - A review. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 2(3), 2249–8958. http://www/ijeat.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/v2i3/C1188022313.pdf

- Ahmad, A. R., Soon, N. K., & Ting, N. P. (2015). Income generation activities among academic staffs at Malaysian public universities. International Education Studies, 8(6), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v8n6p194

- Aldieri, Luigi., Guida, Gennaro., Kotsemir, Maxim., & Vinci, Cincetto Paolo. (2019). In Quality and quantity (Vol. 53, Issue 4). 2003–2040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00853-1

- Alstete, J. W. (2014). Revenue generation strategies: Leveraging higher education resources for increased income. ASHE Higher Education Report, 41(1), 1–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/aehe.20019

- Armstrong, M. (1994). Armstrong’s handbook of performance management: An evidence-based guide to delivering high performance (Google eBook) (4th ed.). Kogan Page. http://books.google.com/books?id=wtwS9VG-p4IC&pgis=1

- Avanesova, A. A., & Shamliyan, T. A. (2018). Comparative trends in research performance of the Russian universities. Scientometrics, 116(3), 2019–2052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2807-6

- Azma, F. (2010). Qualitative Indicators for the evaluation of universities performance. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 5408–5411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.882

- Balabonienė, I., & Večerskienė, G. (2014). The peculiarities of performance measurement in universities. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 156(April), 605–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.249

- Ball, R., & Wilkinson, R. (1994). The use and abuse of performance indicators in UK higher education. Higher Education, 27(4), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01384902

- Bonaccorsi, A., & Secondi, L. (2017). The determinants of research performance in European universities: A large scale multilevel analysis. Scientometrics, 112(3), 1147–1178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2442-7

- Bosch, A., & Taylor, J. (2011). A proposed framework of institutional research development phases. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(5), 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2011.585742

- Brown, M. G., & Svenson, R. A. (1988). Measuring R and D productivity. Research-Technology Management, 31(4), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08956308.1988.11670531

- Çakır, M. P., Acartürk, C., Alaşehir, O., & Çilingir, C. (2015). A comparative analysis of global and National University ranking systems. Scientometrics, 103(3), 813–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1586-6

- Chigudu, D., & Toerien, D. F. (2018). Strength in diversity: An opportunity for Africa’s development. Cogent Social Sciences, 4(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2018.1558715

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2014). Business research methods (12th ed.). Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). sage.

- D’Abate, C., Youndt, M., & Wenzel, K. (2009). Making the most of an internship: An empirical study of internship satisfaction. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 8(4), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2009.47785471

- Diem, A., & Wolter, S. C. (2013). The use of bibliometrics to measure research performance in education sciences. Research in Higher Education, 54(1), 86–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-012-9264-5

- Diezmann, C. M. (2018). Understanding research strategies to improve ERA performance in Australian universities: Circumventing secrecy to achieve success. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 40(2), 154–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1428411

- Dikbud. (2013). University research performance guideline. Ministry of Education and Culture. http://simlitabmas.ristekdikti.go.id/unduh_berkas/Panduan_Operator_Kinerja_Kelembagaan_Penelitian_2017.pdf

- Dikbud. (2020). PD DIKTI. https://pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id

- Dikti. (2020). Guideline for Merdeka Belajar Kampus Merdeka (1st ed.). Directorate General for Higher Education.

- Dill, D. D., & Soo, M. (2005). Academic quality, league tables, and public policy: A cross-national analysis of university ranking systems. Higher Education, 49(4), 495–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-1746-8

- Dixon, R., & Hood, C. (2016). Ranking academic research performance: A recipe for success? Sociologie Du Travail, 58(4), 403–411. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.soctra.2016.09.020

- Dundar, H., & Lewis, D. R. (1998). Determinants of research productivity in higher education. Research in Higher Education, 43(3), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02457402

- Eduan, W., & Yuanqun, J. (2019). Patterns of the China-Africa research collaborations from 2006 to 2016: A bibliometric analysis. Higher Education, 77(6), 979–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0314-6

- Favero, N., & Rutherford, A. (2019). Will the tide lift all boats? Examining the equity effects of performance funding policies in U.S. Higher Education. Research in Higher Education, 61(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-019-09551-1

- Feranecová, A., & Krigovská, A. (2016). Measuring the performance of universities through cluster analysis and the use of financial ratio indexes. Economics and Sociology, 9(4), 259–271. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2016/9-4/16

- Hannover Research. (2020). Alternative revenue generation strategies. Higher Education, June. https://insights.hanoverresearch.com/hubfs/Alternative-Revenue-Generation-Strategies.pdf

- Hazelkorn, E. (2008). Learning to live with league tables and ranking: The experience of institutional leaders. Higher Education Policy, 21(2), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2008.1

- Hermanu, A. I., Sondari, M. C., Dimyati, M., & Sari, D. (2022). Study on university research performance based on systems theory: systematic literature review. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 35(4), 447–472. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2022.122777

- Hill, S. (1995). Regional empowerment in the new global science and technology order. Asian Studies Review, 18(3), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03147539508713014

- Jafari, M., Bourouni, A., & Amiri, R. H. (2009). A new framework for selection of the best performance appraisal method. European Journal of Social Sciences, 7(3), 92–100.

- Javed, Y., Ahmad, S., & Khahro, S. H. (2020). Evaluating the research performance of Islamabad-based higher education institutes. SAGE Open, 10(1), 215824402090208. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020902085

- Kamble, R., & Wankhade, L. (2017). Perspectives on productivity: Identifying attributes influencing productivity in various industrial sectors. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 22(4), 536–566. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2017.087868

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard – measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71–79.

- Karpińska, A. (2020). Innovation and science dilemmas. Unintended consequences of innovation policy for science. Polish Experience. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1718055

- Kim, D.-Y., Kumar, V., & Murphy, S. A. (2008). European foundation for quality management (fEFQM) business excellence model: A literature review and future research agenda. Asac, 1, 1–48. http://ojs.acadiau.ca/index.php/ASAC/article/view/839/728

- Kobarg, S., Stumpf-Wollersheim, J., & Welpe, I. M. (2017). University-industry collaborations and product innovation performance: The moderating effects of absorptive capacity and innovation competencies. Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(6), 1696–1724. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9583-y

- Layzell, D. T. (1999). Research in Higher Education, Volume 40, Number 2 - SpringerLink. Research in Higher Education, 40(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018790815103

- LPDP. (2018). Director Act 25/LPDP/2018, Guideline for Rispro. https://www.lpdp.kemenkeu.go.id/api/Medias/b24d8d97-1633-4abf-9a28-e5fbce3724ba

- Macdonald, S., & Headlam, N. (2008). Manchester: Express Network. 72. https://www.ccardesa.org/knowledge-products/research-methods-handbook-introductory-guide-research-methods-social-research

- Madl, L., Radebner, T., & Stouffs, R. (2021). Technology transfer for social benefit: Ten principles to guide the process. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1947560

- Marisha, B., K, S., & Singh, V. K. (2017). Research performance of central universities in India. Current Science, 112(11), 2198–2207. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v112/i11/2198-2207

- Meek, V. L., Der Lee, V., & Jeannet, J.(2005). University of New England 2. Performance indicators for assessing and benchmarking research capacities in universities. Unesco Bangkok Occasional Paper (Issue 2). https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/bitstream/handle/11343/28907/264616_2005PerformanceIndicators.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Meng, X., & Minogue, M. (2011). Performance measurement models in facility management: A comparative study. Facilities, 29(11), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1108/02632771111157141

- Morgenbesser, L., & Weiss, M. L. (2018). Survive and Thrive: Field research in Authoritarian Southeast Asia. Asian Studies Review, 42(3), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2018.1472210

- Okamuro, H., & Nishimura, J. (2012). Impact of university intellectual property policy on the performance of university-industry research collaboration. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(3), 273–301. doi:10.1007/s10961-012-9253-z

- Parti, K., Szigeti, A., & Serpa, S. (2021). The future of interdisciplinary research in the digital era: Obstacles and perspectives of collaboration in social and data sciences - An empirical study. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1970880

- Prathap, G. (2016). Mapping excellence and diversity of research performance in India. Current Science, 111(3), 470–474. https://doi.org/10.18520/cs/v111/i3/470-474

- Ramsden, P. (1999). Predicting institutional research performance from published indicators: A test of a classification of Australian university types. Higher Education, 37(4), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003692220956

- Reichert, S. (2019). the Role of Universty in Regional Innovation Ecosystem. European University Assoiation. Brussel, Belgium: asbl. https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/euainnovationecosystemreport2019-3-12.pdf

- Ristekbrin. (2020a). Innovation performance reporting guidelines 2020. Ministry of Research and Technology/ National Agency for Research and Innovation. https://lldikti14.kemdikbud.go.id/assets/berkas/d88750d96b594e6472724e4e36aa1a49.pdf

- Ristekbrin. (2020b). Performance Report of 2019. https://www.brin.go.id/informasi-publik/laporan-kinerja-2019

- Ristekbrin. (2021). Performance Report of 2020. https://www.brin.go.id/informasi-publik/laporan-kinerja-2020

- Sabah, F., Hassan, S. U., Muazzam, A., Iqbal, S., Soroya, S. H., & Sarwar, R. (2019). Scientific collaboration networks in Pakistan and their impact on institutional research performance: A case study based on Scopus publications. Library Hi Tech, 37(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10/1108/LHT-03-2018-0036

- Sabharwal, M. (2013). Comparing research productivity across disciplines and career stages. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 15(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.785149

- Savithri, S., & Prathap, G. (2015). Indian and Chinese higher education institutions compared using an end-to-end evaluation. Current Science, 108(10 1922–1926). https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2041.10

- Schroeder, R., & Goldstein, S. M. (2016). Operations management in the supply chain: Decision and cases (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Sim, J., & Waterfield, J. (2019). Focus group methodology: Some ethical challenges. Quality & Quantity, 53(6), 3003–3022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00914-5

- Siripitakchai, N., & Miyazaki, K. (2015). Assessment of research strengths using co-citation analysis: The case of Thailand national research universities. Research Evaluation, 24(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv018

- Sizer, J., Spee, A., & Bormans, R. (1992). The rôle of performance indicators in higher education. Higher Education, 24(2), 133–155. http://doi.org/10/1007/BF00129438

- Söderlind, J., & Geschwind, L. (2019). Making sense of academic work: The influence of performance measurement in Swedish universities. Policy Reviews in Higher Education, 3(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2018.1564354

- Tahira, M., Alias, R. A., & Bakri, A. (2015). Application of h and h-type indices at meso level: A case of Malaysian engineering research. Malaysian Journal of Library and Information Science, 20(3), 77–86. https://jummec.um.edu.my/index.php/MJLIS/article/view/1776

- Tijssen, R., & Winnink, J. (2022). Global and local research excellence in Africa: New perspectives on performance assessment and funding. Science, Technology and Society, March, 097172182210782. https://doi.org/10.1177/09717218221078236

- Tognolini, J., Adams, K., & Hattie, J. (1994). A methodology to choose performance indicators of research attainment in universities. Australian Journal of Education, 38(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494419403800202

- Tseng, F. C., Huang, M. H., & Chen, D. Z. (2018). Factors of university–industry collaboration affecting university innovation performance. Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(2), 560–577. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9656-6

- Vernon, M. M., Andrew Balas, E., Momani, S., & Bornmann, L. (2018). Are university rankings useful to improve research? A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 13(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193762

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Content analysis. In Basic content analysis (Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, Book 49) (2nd ed., pp. 117–124). Sage.

- Wood, F. (1990). Factors influencing research performance of university academic staff. Higher Education, 19(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00142025

- Zhang, B., & Wang, X. (2017). Empirical study on influence of university-industry collaboration on research performance and moderating effect of social capital: Evidence from engineering academics in China. Scientometrics, 113(1), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2464-1