Abstract

This study is based on an incident of collaborative cheating by a group of postgraduate management students during an online quiz. There was direct evidence against eight students. Circumstantial evidence was found against another 49 in a class of 184 students (52.72% women, average age 24.03 years), and 28 of them confessed during the post-facto investigation. Gender and age were not significant factors for either cheating or confession. The students came from various educational backgrounds, which turned out as a significant factor in both cheating and confession. The results indicate that the likelihood of cheating in that course (Managerial Economics), and confessing after being charged, was significantly lower for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) graduates. Based on the content analysis of the confessors, I have developed a model of the decision-process accounting for self-conscious negative affect, and decision dilemmas owing to the anxiety of getting implicated and fear of social exclusion by peers. Negative affect has impacted everyone. Eight students confessed independently possibly because of overpowering anxiety. Others confessed in six groups to avoid social exclusion. The study highlights the importance of experimental research, as some of the findings differ from those obtained in surveys where the participants self-report dishonesty.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Cheating in exams is a matter of concern for the higher education community. The incidence of cheating increased during the COVID19 pandemic when classes and exams were conducted online. This study is based on a group of postgraduate management students, some of who cheated during an online exam. While there was evidence of cheating against a small fraction, others were suspected due to circumstantial evidence. Some of the suspects confessed while others did not. This study examined the reasons for cheating as well as that to confess. The findings indicate that educational background was a significant demographic factor that determined both cheating and confession. Analysis of the confession statements of the students helped in identifying the behavioural and psychological factors that induced them to confess. The study concludes that the decision to confess, or not, was driven by the anxiety of getting implicated and the fear of social exclusion by peers.

1. Introduction

Academic dishonesty (Davis et al., Citation1992; Wajda-Johnston et al., Citation2001) in the form of cheating (Cizek, Citation1999) in examinations has been a global concern for the higher education community for long. During the COVID19 pandemic, which forced the institutions of higher education to conduct online examinations, and often without any proctoring, the concern about cheating increased manyfold (Slade et al., Citation2021). However, the pandemic induced online examinations created opportunities to study cheating behaviour on the ground. In this paper, I report the findings from an incident of collaborative cheating (Chapman et al., Citation2004; Martin, Citation2012; Wryobeck & Whitley Jr., Citation1999) by a group of postgraduate management students in India. While there was direct evidence of cheating against a few students, many were charged based on circumstantial evidence that surfaced during the investigation in the aftermath. These students were given a chance to confess before direct evidence against them appeared, or their accomplices implicated them, in exchange for a lessened penalty. Some confessed independently as individuals, some others confessed as groups of collaborators, and some did not confess.

At the onset, I must clarify that the incident of collaborative cheating took place of its own accord, without any intervention. Hence, in this paper, I will refer to the method as a natural experiment. DiNardo (Citation2008), in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (Second ed., pp. 856–864), defines natural experiments or quasi-natural experiments in economics as “serendipitous situations in which persons are assigned randomly to a treatment (or multiple treatments) and a control group, and outcomes are analysed for the purposes of putting a hypothesis to a severe test; they are also serendipitous situations where assignment to treatment ‘approximates’ randomized design or a well-controlled experiment.” In the cheating incident described here, and its aftermath, the instructor could test the students in online quizzes as well as in proctored, in-person, pen-and-paper-based exams, due to COVID19 induced situation that occurred naturally. After the cheating incident was reported, and direct evidence was obtained, the instructor decided to investigate. The instructor also got the opportunity to assess the students’ learning in proctored, in-person, pen-and-paper-based exams when the pandemic induced restrictions were relaxed. The naturally evolving scenario created an experiment like set-up, where the test-taking environment got controlled naturally. The instructor could assess the students in both online and in-person exams. Consequently, the performance of the students who cheated could be studied vis-à-vis those who did not cheat in both test-taking environments. The investigation that followed the incident of collaborative cheating also occurred naturally. Based on the data obtained from this natural experiment, in this paper I address the following research questions:

RQ1. What factors prompt a student to cheat?

RQ2. What factors prompt a cheater to confess?

Most studies on academic dishonesty and cheating used questionnaire-based surveys (Chirumamilla et al., Citation2020; Colnerud & Rosander, Citation2009; Zhang & Yin, Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2018) among students and educators. There are very few studies (Harmon & Lambrinos, Citation2008; Rosile, Citation2007) where the cheating behaviour of students has been examined in a natural setup. Confession decision has been studied experimentally (Dunbar et al., Citation2019; Halevy et al., Citation2014; Wilford & Wells, Citation2018), but not in the context of academic dishonesty. The present study is the first of its kind where collaborative cheating and the decision to confess academic dishonesty have been examined through a natural experiment. A statistical comparison between the students who collaborated in cheating, and the others in the class, helped us in answering RQ1. Likewise, the comparison between the students who confessed, and those who did not, answered RQ2. The students belonged to a diverse educational (undergraduate) background and had a varying quantum of professional work experience, both of which were considered as plausible factors apart from other demographic factors. The educational background turned up to be the significant demographic factor that determined both cheating and confession. Further, analysing the confession statements of the students, I have identified the behavioural and psychological factors that induced them to confess and have outlined the decision-making process.

The next section explains the overview of the method, and the following three sections document the analyses. I have discussed the extant literature and positioned the present research in the penultimate section, before drawing conclusions and implications.

2. Method and material—Overview

The institution where the study has been conducted is a well-known management institute in India (the identity of the institute is not disclosed to protect the identity of the students) and offers a full-time two-year postgraduate program in Management (equivalent to MBA) and operates on a trimester system. Due to COVID19 induced restrictions, the first trimester of the academic year 2021–22 began online on 5 July 2021. In their first trimester, the students take a course in Managerial Economics. On 21 August 2021 during an online multiple-choice (MC) quiz for this course, which was not proctored, several students in multiple groups collaborated in cheating using WhatsApp messaging. A whistle-blower (one student) informed the instructor about the collaborative cheating and provided screenshots of the WhatsApp conversations of eight classmates. When charged by the instructor, these students admitted to cheating. Further investigation made the instructor suspect the involvement of another 49 students in collaborative cheating. 28 of the 49 suspects confessed to cheating and the rest denied it. Based on the suspicion of the involvement of many students in cheating, the instructor rendered the quiz null and void. A detailed report on the investigation is provided as supplementary material. The outcome and timeline of the investigation are summarized in .

Table 1. Outcome and timeline of the investigation

The easing of the COVID19 induced restrictions allowed the institute to resume in-person classes and exams in the first week of September. The instructor switched back to traditional pen and paper-based written tests, wherein collaborative cheating was not possible due to strict surveillance. This opportunity of assessing a set of students both online (not proctored) and in-person (under surveillance), within a single course, created the setup of a natural experiment.

2.1. Subjects

184 postgraduate students of Management (52.72% women; average age 24.03 years). The students came from a varied educational background at the undergraduate level (Engineering and Technology 60.87%, Business 15.76%, Humanities and Social Sciences 11.95%, Natural Sciences and Mathematics 11.41%), and some had prior work experience (average work experience 18.81 months; 35.33% no work experience). To maintain the anonymity of the individuals, in this study the students are denoted by subject identity numbers (“subject ID”), different from their student identity numbers.

2.2. Methodology

For this study, I used a mixed-method. First, I have conducted a series of statistical analyses of the student's performance in the online quizzes and the in-person assessment tests to infer that the suspected students, irrespective of whether they confessed or not, had cheated in the quiz wherein collaborative cheating was detected. Next, I have conducted Pearson’s chi-square tests and binary logistic regressions to examine if cheating and the decision to confess depended on demographic factors (gender, age, undergraduate educational background, and prior work experience). For the statistical tests, I have used SPSS 23.0. Finally, I have studied the students’ decision to confess by undertaking a content analysis of the confession statements sent by the students to the instructor. The content analysis also uncovers the students’ motivation to cheat.

3. Performance analysis

The students were classified into three categories—those who confessed when charged based on circumstantial evidence or admitted of collaborative cheating when charged based on direct evidence (N = 36, referred to as “Confirmed cheaters”), those who were charged based on circumstantial evidence but denied their involvement in collaborative cheating (N = 21, referred to as “Deniers”) and those who were not suspected (N = 127, referred to as “Not suspected”). Their performances in the assessment tests of the course, before and after the cheating incident, was analysed. A student’s test score relative to the average score of the class was taken as the performance indicator. This was done to neutralize the effect of varying difficulty and nature of different assessment tests.

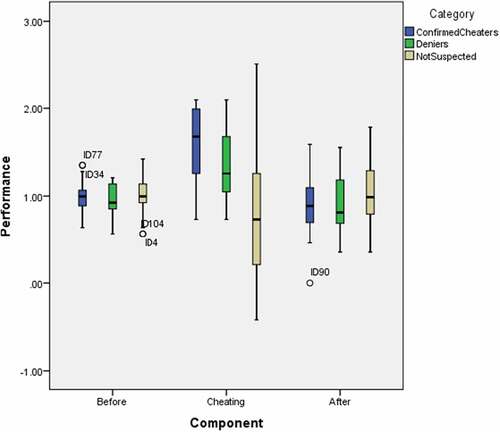

The distribution of performance of the students belonging to the three categories, before and after the cheating incident, and in the quiz where in the students collaborated in cheating, are shown in the clustered boxplots of Figure . The mean performances of the three different categories are summarized in .

Table 2. Mean performances

The mean performances summarized in Table show that the confirmed cheaters, as well as the deniers, performed better than those not suspected in the quiz where collaborative cheating was detected, and those not suspected did better in the assessments afterwards. To study whether the differences in the mean performances between the categories are significant, I have conducted Tukey’s HSD test. The p-values are summarized in . Results of Tukey’s HSD test show that there was no significant difference in the mean performances across categories before the cheating incident. Though the assessment tests before the cheating incident were also unmonitored online quizzes, Tukey’s HSD results indicate that there was no large-scale cheating before the quiz wherein cheating was detected.

Table 3. P-values of Tukey’s HSD test

There was no significant difference in the mean performances of the confirmed cheaters and the deniers, across the assessments. However, the mean performances of those who were not suspected were significantly worse compared to that of the confirmed cheaters and the deniers in the quiz wherein collaborative cheating was detected, and significantly better in the assessments after the incident.

We also conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the performances before, in and after the incident of collaborative cheating. The effect of the category (Confirmed cheaters, Deniers and Not suspected) was not significant before the incident (p = 0.276) but was significant in the quiz where collaborative cheating was detected (p = 0.000) and in the assessments after the incident (p = 0.024). Notably, the boxplots in indicate that there are some outliers. The results of Tukey’s HSD and the ANOVA results remain the same, with minor changes in the p-values, even if the outliers’ data are removed.

3.1. Inferences

Based on Tukey’s HSD tests and ANOVA, we may infer the following:

Firstly, there was only one incident of large-scale collaborative cheating in the course. Before that incident there was no significant difference in the performances, and after the incident the assessment tests were monitored to prevent cheating.

Secondly, the deniers were not honest. In the quiz where the students collaborated in cheating, the confirmed cheaters and the deniers performed significantly better than those not suspected.

Thirdly, the confirmed cheaters as well as the deniers were relatively weaker students. When the assessment tests were in-person and proctored, their performance was inferior compared to those who were not suspected.

4. Demographic factors

In this section, first we will examine collaborative cheating, and then the decision to confess, based on the demographic profile of the students. For the former study, I have clubbed the categories of Confirmed cheaters and Deniers into one category referred to as “Cheaters” (N = 57) and compared the Cheaters to the Not suspected (N = 127) category. The rationale for clubbing the Deniers with the Confirmed cheaters follows from the performance analysis reported in the previous section, which established that the deniers were not honest.

From the set of Confirmed cheaters, I have removed the observations corresponding to the eight students charged based on direct evidence to create the category referred to as “Confessors” (N = 28), as these eight students did not have to decide whether to confess. To study the decision to confess, I have compared Confessors to Deniers (N = 21). The demographic profile of the categories Cheaters, Not suspected, Confessors and Deniers are given in .

Table 4. Demographic profile across categories

In the dataset, gender was dichotomous. The data on the undergraduate educational background was available under four categories, as reported in the Methods section. Since there was a small number of observations for Confessors and Deniers, I have reorganised the education data into two categories—STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and non-STEM (which comprises Business, Humanities and Social Sciences). Also, the distribution pattern across Cheaters, Not suspected, Confessors and Deniers is similar for Business and Humanities and Social Sciences, and for Science and Technology and Natural Sciences and Mathematics (which were clubbed as STEM). The share of women and non-STEM graduates was greater among the cheaters compared to those who were not suspected, and among the confessors compared to the deniers. Also, the cheaters were less experienced vis-à-vis those who were not suspected, and the confessors were younger and less experienced vis-à-vis the deniers.

4.1. Cheating

Based on the demographic data of the class (N = 184), I have studied the determinants of cheating behaviour. Since the mean age of the cheaters and those not suspected are the same, and age and prior work experience are correlated (coeff. = 0.75), I have considered only the work experience. Also, while a few months’ difference in age is unlikely to be a differentiating factor, a few months’ difference in work experience could be. To study the effect of demographic factors on cheating, I ran binary logistic regressions (the reference category is “Not suspected”). I did not take both gender and educational background as independent variables because Pearson’s chi-square test showed a significant association (χ2 = 11.133, p = 0.001) between them. Hence, I ran separate regressions to examine the effects of these two factors. The omnibus test failed (χ2 = 3.66, p = 0.16) for the regression with gender and work experience as covariates, indicating that the accuracy of the model did not improve significantly by their inclusion. However, the regression with educational background and work experience as covariates cleared the omnibus test (χ2 = 10.848, p = 0.004), and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ2 = 2.733, p = 0.95 > 0.1) indicating that the model is a good fit for the data.Footnote1 The regression coefficients, the Wald statistic, the p-values, and the odds ratios are reported in . The regression results show that the non-STEM graduates in the data set were 3.3 times more likely to cheat in the course. However, there is no effect of work experience.

Table 5. Logistic regression of cheating behaviour

4.1.1. Reasons for cheating

The course (Managerial economics) uses a pedagogy focused on concept development and application. Further, the course requires familiarity with basic level calculus and an understanding of graphs. Consequently, the non-STEM graduates struggle more than STEM graduates in this course. As reasons for cheating, the students who confessed stated stress related to coping with academics, under-preparedness, poor performance in previous assessment tests, fear of failing in the course, inability to compete with peers, parental expectations, and expectations from self, among others. In brief, the stated reasons indicate performance pressure (Tremayne & Curtis, Citation2021) coupled with difficulty in coping with the course. The mean performance of the cheaters was significantly inferior, compared to the rest of the class, in the in-person and proctored assessments after the cheating incident (refer to ). Moreover, the confessors were relatively less experienced (refer to ). Several confessors mentioned “a momentary lapse of judgment” in their confession statements, which also indicates a lack of maturity in assessing the consequences of academic dishonesty.

4.2. Confession

To study the determinants of confession decision (confess or deny), I have examined 49 observations consisting of 28 confessors and 21 deniers. Within this dataset too, age and work experience are correlated (coeff. = 0.75), and I have considered only the work experience. Pearson’s chi-square tests revealed that gender is not associated to either educational background (χ2 = 2.225, p = 0.136) or confession decision (χ2 = 0.258, p = 0.612). However, there is a significant association between educational background and the confession decision (χ2 = 3.96, p = 0.047). I ran binary logistic regression of the confession decision (reference category is “Deniers”) on educational background and work experience. The model cleared the omnibus test at 10% level of significance (χ2 = 4.728, p = 0.094), and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (χ2 = 9.87, p = 0.13) indicating a good fit. The regression results are given in .

Table 6. Logistic regression of confession decision

The regression results show that the non-STEM graduates in the data set were 2.97 times more likely to confess. However, the effect of work experience is negligible and statistically insignificant. In the next section, we will delve into a more nuanced analysis of the decision to confess

5. Analysis of the decision to confess

In this section, first, we will identify the behavioural and psychological factors affecting the decision to confess through a content analysis of the email messages of the confessors and the deniers, and by analysing the timing and pattern of confessions. Next, I will develop a model of the decision-making process based on the identified behavioural and psychological factors.

5.1. Behavioural and psychological factors

The number of confessions increased over time, during the weeklong investigation. Majority of the students who confessed decided to do so in the last two days of the investigation (Refer to ). Several students who first denied, eventually confessed. To capture the dynamics of the decision-making process leading to confessions, I have presented the content analysis of confession statements following the chronology of the investigation, and in the process identify the factors affecting the decisions of the students.

5.1.1. Fear of social exclusion by classmates

It was difficult for the students to confess independently as peers built up pressure on them not to confess. Despite the instructor offering not to report against them in case they confessed, only seven among 26 students charged on Day-2 confessed. Two of them confessed independently, and the others confessed as two groups consisting of two and three members, respectively. The following statement (Subject ID 73) indicates gratitude towards classmates, but the underlying fear of social exclusion cannot be ruled out.

‘I believe it is not my position to indict or implicate any of my batchmates especially since a lot of my peers have been like mentors to me and helped me a lot in understanding the concepts of subjects.’

Seven more, including a four-member group of joint confessors, confessed on Day-3 when the instructor produced timestamps of students’ responses. The other three refused to disclose who their accomplices were. The following two statements by two students (Subject IDs 148 and 153, respectively) indicate that they were afraid of being socially excluded by their peers (referred to as “batchmates”) if they helped the instructor in implicating others.

‘ … as much as I know that they are at equal fault I truly do not wish to call their name out, I will be studying & living with these batchmates for the next two years together.’

‘I have taken help personally from my batchmate, but I would not want to take the name as I will be spending the next two years with my batchmates.’

5.1.2. Anxiety and confession dilemma

The remaining 35 suspects still denied their involvement in cheating. In their defence, they either claimed to possess superior computing skills or implied that they blindly guessed the answers. 14 suspects eventually confessed. Excluding one individual, they confessed in groups. From their confession statements it is apparent that some suspects could not bear the psychological distress caused by the anxiety of withholding information, and possibly convinced their accomplices to confess. Nine confessors mentioned feeling psychologically distressed. Seven of them were among the final 14 confessors. The following two statements (Subject IDs 62 and 84, respectively) are given as examples:

‘Because of one mark, I haven’t been at peace for the last few days. I felt very guilty and scared when this came out and could not come up to you to confess.’

‘ … considering how difficult the situation has been not only for me and my batchmates, but for you as well, I needed to come clean as this has been taking a toll on my mental health. I know I should have admitted to what I have done in my previous communication. It was my fear towards admission of guilt that stopped me from doing so.’

The same individual who wrote the letter of the above two statements wrote the following message two days earlier.

‘The answer marked was a fluke, a random guess, which contrary to my expectations, turned out to be the right answer.’

Another line of argument used by some of the suspects to initially deny their involvement in cheating was their superior ability. The following two statements of a student (Subject ID 77), within a period of three days, sums up the dilemma that several confessors went through.

‘I took a calculative risk to offset the previous loss of time, thus allowing myself to mark the answer in less than 30 seconds.’ [Day-4]

‘The past few days have severely impacted my mental state, and I can no longer live with this guilt. … Other members of the group will also be sending you their confessions.’ [Day-7]

5.1.3. Stress due to uncertainty

The majority of the confessions came in groups. Only eight students confessed independently. The others confessed in six different groups. (Refer to ).

Table 7. Confessing groups

As the instructor presented circumstantial evidence against them, the chance of being implicated increased. The students increasingly became anxious that the instructor would find conclusive evidence against them, or their accomplices would implicate them. The level of anxiety depended on the students’ estimate of the chance of being implicated and reported. The ones with the highest estimates became most anxious. This anxiety caused psychological distress. Different individuals had different levels of tolerance. The most risk-averse ones found it difficult to handle the pressure of withholding confession and wanted to confess. Eventually, they discussed within small groups of accomplices and decided to confess together, or against it.

5.1.4. Negative affects

27 out of the 28 confessors mentioned experiencing at least one of the following negative affective states—guilt, shame, and regret. 18 confessors reported being distressed by the feeling of guilt. For example, one student (Subject ID 59) wrote:

‘The mental stress and anxiety that has come as an outcome of this has shown me how the ordeal is not worth it. Right from eating to sleeping to preparing for academics, nothing has come easy to me as the guilt of this has eaten me up.’

Some of the excerpts reproduced earlier also indicate that the feeling of guilt had played a significant role in the decision to confess. Among the 18 confessors who expressed feeling guilty, 15 also expressed either regret, or feeling of shame, or both. The overlap of the stated affects is shown in the Venn diagram given in .

Guilt is internal to an individual’s self-consciousness (Lewis, Citation1971; Mosher, Citation1965) that can occur due to an act of moral transgression (Berndsen et al. Citation2004; Devine & Monteith, Citation1993), which is harmful to others (Baumeister et al., Citation1994; Eisenberg, Citation2000). Regret may also occur due to unfulfilled expectations from self, subsequent to an act of moral transgression (Gilovich & Medvec, Citation1995) that is harmful to someone else (Zeelenberg et al., Citation1998). In their statements, 12 confessors mentioned both guilt and regret, and four expressed regrets without mentioning the feeling the guilt. However, their regret must have stemmed from their guilt, which remained unexpressed. Six confessors expressed feeling ashamed, without mentioning guilt or regret. Eight others, who expressed feeling ashamed, also mentioned feeling guilty, and four of them expressed regrets too. Another student who was ashamed expressed regret without mentioning guilt. The act of cheating could be guilt-inducing for some people and shame-inducing for others (Tangney et al., Citation2007). In cases of both guilt and shame, the self is evaluated negatively in connection to the act of transgression. Shame is additionally associated with an objectionable self (Haidt, Citation2003; Lewis, Citation1971). Essentially, both guilt and shame arise from the same transgression (cheating, in the present context) and belong to the family of negative “self-conscious emotions” but differ in “the manner in which people construe and then experience” them (Tangney et al., Citation1996). Based on the abovementioned understanding of guilt, shame, and regret, we may safely conclude that negative self-conscious affective states played a role in the decision-making process of all 27 confessors who stated experiencing at least one of these affects.

5.2. Decision-making process

illustrates the decision-making process of confession.

Prior studies have documented that the liars suffer from anxiety and tension (Dunbar et al., Citation2019; Granhag & Strömwall, Citation2002) during interrogation. Those who had a high estimate of the probability became more anxious. At the same time, those who are relatively more self-conscious started experiencing guilt and/or shame and started regretting their decision to cheat. These two effects caused psychological distress and the ones who were most self-conscious and risk-averse confessed independently, as individuals. Confession by some students caused more anxiety among others as the chances of being implicated and reported increased. The decision to withhold confession seemed riskier to the students who did not confess. They did not confess independently fearing social exclusion by accomplices and peers but encountered a decision dilemma, which added to their psychological stress. After discussing in small groups, they decided either to confess or to deny.

5.2.1. Individual v. group confession

Self-conscious negative affect was reported by all confessors except one. Hence, negative affect is not the differentiating factor between individual and group confessors. But for those who confessed independently as individuals, the anxiety due to the risk of being implicated must have overpowered the fear of social exclusion. This, in turn, indicates that the individual confessors were more risk-averse and/or had greater estimates of the probability of getting implicated, compared to the group confessors. Among the eight individual confessors, six were non-STEM graduates (75%) and five were women (62.5%). Out of 20 group confessors (refer to Table ), 10 were non-STEM graduates (50%) and 13 were women (65%). The share of women was nearly the same among the individual confessors and among the group confessors. Therefore, we may conclude that gender was not a factor that drove individual confessions. But the share of non-STEM graduates among the individual confessors was strikingly higher than that among group confessors. Consequently, this indicates that the non-STEM graduates were relatively more risk-averse and/or had estimated greater probabilities of getting implicated, vis-à-vis the STEM graduates.

6. Discussion

6.1. Educational background

Results of logistic regressions show that non-STEM students among the subjects were 3.3. times more likely to cheat, and 2.97 times more likely to confess when charged based on circumstantial evidence. The non-STEM students might have had difficulty in coping with the academic rigour of the course because of its technical nature, and the need to survive in the competitive scenario of an MBA class might have tempted them to cheat. But it is apparently difficult to perceive a causal association between educational background and the decision to confess. While the educational background is unlikely to determine risk attitude, it may have an impact on how people estimate probabilities. There is experimental evidence that people who apply heuristics in estimating conditional probabilities tend to overestimate low probabilities and underestimate the high probabilities (Grether, Citation1980, Citation1992; Holt & Smith, Citation2009). Non-STEM graduates, because of their educational background, are more likely to apply heuristics in probability estimation than STEM graduates. They might have underestimated the probability of the instructor detecting cheating in an unmonitored online quiz and overestimated the probability of individual cheaters getting implicated after cheating was detected. This explains the most striking result in this paper, that undergraduate educational background surfaced as the only significant factor in cheating, as well as in confession decisions.

Juxtaposed to the findings of the present study, the extant literature shows that non-STEM students have a stronger negative attitude towards academic dishonesty (Chen & Chou, Citation2017; Hu & Lei, Citation2015) and self-report lower rates of cheating (Harding et al., Citation2007; Zhang et al., Citation2018). The plausible reason for this divergence of results is methodological rather than cultural because non-STEM students self-reported lower cheating rates in Western (Harding et al., Citation2007) as well as in Chinese (Zhang et al., Citation2018) cultural contexts. While I have obtained data from an actual cheating incident, the earlier studies relied on self-reporting of participation in cheating by survey respondents who are prone to social desirability bias (Dalton & Ortegren, Citation2011; Zhang & Yin, Citation2020).

6.2. Gender

Gender was not a significant factor in either collaborative cheating or the confession decision. Nevertheless, I found that the share of women was relatively more among the cheaters compared to those not suspected, and more among the confessors compared to the deniers. This result is incongruent with the results obtained in survey-based studies (Gibson et al., Citation2008; Tibbetts, Citation1999) that show significantly less participation of women in cheating and a stronger negative attitude of women toward cheating. This divergence of results could also be discerned through the differences in research methods. In surveys, societal gender norms can influence responses, which might be intended towards creating a socially desirable impression (Chung & Monroe, Citation2003). In contrast, the present research was based on a real-life incident wherein the subjects chose whether to participate in collaborative cheating. Notably, Zhang et al. (Citation2018) also did not find women’s participation in cheating to be significantly different from that of men, despite women showing a stronger negative attitude towards cheating.

We did not find any gender difference in experiencing self-conscious negative affect. This result is consistent with Whitley (Citation2001), who also observed that women did not experience more negative affect despite potential cognitive dissonance stemming from the dichotomy of having a stronger negative attitude towards academic dishonesty and participation in it.

6.3. Contribution to the literature

Our research contributes to the literature on academic dishonesty in general, and collaborative cheating in particular, on two accounts—(i) the use of natural experiment, which is a methodological contribution, and (ii) the study of confession decision, which had largely been overlooked so far. Although the literature on academic dishonesty is vast, only Rosile (Citation2007) and Harmon and Lambrinos (Citation2008) reported studies based on data from cheating incidents while the other studies were based on survey responses. The approach of Rosile (Citation2007) is entirely qualitative because she had only nine observations. Conversely, Harmon and Lambrinos (Citation2008) adopt an entirely quantitative methodology to conclude that the likelihood of cheating is much more in an e-exam that is not proctored. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study of demographic, behavioural and psychological factors, based on data from a cheating incident. The divergence of some of the results reported here, from those obtained in survey-based studies, highlights the importance of natural/field experiments in academic dishonesty research. Confession decision has been studied through surveys (Halevy et al., Citation2014) as well as experimentally (Dunbar et al., Citation2019; Wilford & Wells, Citation2018), though not through field experiments. The insights on why some students decide to confess, either independently or as a group, when charged based on circumstantial evidence, while others decide against it, should facilitate further research in the area.

6.4. Future research directions

Since this study was based on a cheating incident where only a subset of students was implicated, the dataset was small. Though I have obtained some results that are different from the results obtained in surveys, their generalizability is limited. Further studies, in different cultures and in different academic disciplines, are required to validate the conjecture that actual student behaviour diverges from their self-reporting.

Our study was done on management students who come from varied educational backgrounds. In some courses, non-STEM graduates are at a disadvantage while in others STEM graduates may be disadvantaged. To observe whether being disadvantaged is a reason for cheating, a similar experiment needs to be replicated in a course where STEM students are disadvantaged. Also, the experiment may be replicated controlling for the disadvantage and comparing across disciplines of study. For example, if the experiment is conducted among undergraduate students within a discipline of study, it might be possible to compare the propensity to cheat amongst disciplines. We do not see a significant gender effect, primarily because gender and educational background was correlated in the data set. The effect of gender might be observed if such an experiment is run in disciplines where the students come from the same educational background.

We have hypothesized that non-STEM students underestimated the probability of cheating detection, and they overestimated the probability of being implicated after cheating was detected. Whether there exists a significant difference between STEM and non-STEM students in the heuristic estimation of conditional probability, could be investigated in a future study.

7. Implications and conclusion

In this paper, I have reported an incident of collaborative cheating during an online quiz and studied the reasons for cheating and the decisions to confess. The incident shows that the propensity to cheat increases if an online quiz is not proctored. However, employing proctors in short quizzes may be costly. Hence, it is crucial to investigate post-facto through circumstantial evidence like answering patterns and timestamps. This implies that keeping a record of every action of the students on the online testing system is immensely important. To reduce the instances of cheating in online exams, the instructors may strategically inform the students about this record-keeping of students’ activities during the online exams, and how such records might be used if anyone is suspected of cheating. Such information should result in an upward revision of students’ beliefs about the chance of getting implicated in cheating. Consequently, a majority of the students should refrain from using dishonest means.

Our findings from the natural experiment show that cheating behaviour, on the ground, differs from that self-reported by students. This divergence of results underscores the importance of experimental research on academic dishonesty can complement survey-based research and might bring forth new insights.

Ethics statement

The study was non-interventional and the identities of any individual or organization have not been revealed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.1 KB)Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Relevant data is provided as supplementary material.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sumit Sarkar

The author is a professor of Economics at XLRI – Xavier School of Management, India. His research areas are applied game theory and behavioural economics. The published works of the author are in the areas of psychological game theory, social preferences and fairness concerns. Some of the journals that published his works are the European Journal of Operational Research, the Annals of Operations Research, the Journal of Choice Modelling, the Journal of Consumer Marketing, and Managerial and Decision Economics, among others. Presently, he is undertaking research in the areas of lying, cheating and deception. The current paper belongs to this new research area.

Notes

1. All supplementary test results are available from the authors.

References

- Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243

- Berndsen, M., van der Pligt, J., Doosje, B., & Manstead, A. (2004). Guilt and regret: The determining role of interpersonal and intrapersonal harm. Cognition & Emotion, 18(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930244000435

- Chapman, K. J., Davis, R., Toy, D., & Wright, L. (2004). Academic integrity in the business school environment: I’ll get by with a little help from my friends. Journal of Marketing Education, 26(3), 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475304268779

- Chen, Y., & Chou, C. (2017). Are we on the same page? College students’ and faculty’s perception of student plagiarism in Taiwan. Ethics & Behavior, 27(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2015.1123630

- Chirumamilla, A., Sindre, G., & Nguyen-Duc, A. (2020). Cheating in e-exams and paper exams: The perceptions of engineering students and teachers in Norway. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(7), 940–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1719975

- Chung, J., & Monroe, G. S. (2003). Exploring social desirability bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(4), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023648703356

- Cizek, G. J. (1999). Cheating on tests: How to do it, detect it, and prevent it. Erlbaum.

- Colnerud, G., & Rosander, M. (2009). Academic dishonesty, ethical norms and learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(5), 505–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930802155263

- Dalton, D., & Ortegren, M. (2011). Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0843-8

- Davis, S. F., Grover, C. A., Becker, A. H., & McGregor, L. N. (1992). Academic dishonesty: Prevalence, determinants, techniques, and punishments. Teaching of Psychology, 19(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1901_3

- Devine, P. G., & Monteith, M. J. (1993). The role of discrepancy-associated affect in prejudice reduction. In D. M. Mackie & D. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Affect, Cognition and Stereotyping (pp. 317–344). Academic Press.

- DiNardo, J. (2008). Natural experiments and quasi-natural experiments. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The new palgrave dictionary of economics (second ed.) (pp. 856–864). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2006-1

- Dunbar, N. E., Bernhold, Q. S., Jensen, M. L., & Burgoon, J. K. (2019). The anatomy of a confession: An examination of verbal and nonverbal cues surrounding a confession. Western Journal of Communication, 83(4), 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2018.1539760

- Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 665–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.665

- Gibson, C. L., Khey, D., & Schreck, C. J. (2008). Gender, internal controls, and academic dishonesty: Investigating mediating and differential effects. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 19(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511250801892714

- Gilovich, T., & Medvec, V. H. (1995). The experience of regret: What, when, and why. Psychological Review, 102(2), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.379

- Granhag, P. A., & Strömwall, L. A. (2002). Repeated interrogations: Verbal and non‐verbal cues to deception. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 16(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.784

- Grether, D. M. (1980). Bayes’ rule as a descriptive model: The representativeness heuristic. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 95(3), 537–557. https://doi.org/10.2307/1885092

- Grether, D. M. (1992). Testing Bayes rule and the representativeness heuristic: Some experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 17(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(92)90078-P

- Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson (Ed.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford University Press.

- Halevy, R., Shalvi, S., & Verschuere, B. (2014). Being honest about dishonesty: Correlating self-reports and actual lying. Human Communication Research, 40(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12019

- Harding, T. S., Mayhew, M. J., Finelli, C. J., & Carpenter, D. D. (2007). The theory of planned behavior as a model of academic dishonesty in engineering and humanities undergraduates. Ethics & Behavior, 17(3), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420701519239

- Harmon, O. R., & Lambrinos, J. (2008). Are online exams an invitation to cheat? The Journal of Economic Education, 39(2), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.3200/JECE.39.2.116-125

- Holt, C. A., & Smith, A. M. (2009). An update on Bayesian updating. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 69(2), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2007.08.013

- Hu, G., & Lei, J. (2015). Chinese university students’ perceptions of plagiarism. Ethics & Behavior, 25(3), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2014.923313

- Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review, 58(3), 419–438.

- Martin, D. E. (2012). Culture and unethical conduct: Understanding the impact of individualism and collectivism on actual plagiarism. Management Learning, 43(3), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507611428119

- Mosher, D. L. (1965). Interaction of fear and guilt in inhibiting unacceptable behavior. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29(2), 161–167.

- Rosile, G. A. (2007). Cheating: Making it a teachable moment. Journal of Management Education, 31(5), 582–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562906289225

- Slade, C., Lawrie, G., Taptamat, N., Browne, E., Sheppard, K., & Matthews, K. E. (2021). Insights into how academics reframed their assessment during a pandemic: Disciplinary variation and assessment as afterthought. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1933379

- Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256

- Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145

- Tibbetts, S. G. (1999). Differences between women and men regarding decisions to commit test cheating. Research in Higher Education, 40(3), 323–342. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018751100990

- Tremayne, K., & Curtis, G. J. (2021). Attitudes and understanding are only part of the story: Self-control, age and self-imposed pressure predict plagiarism over and above perceptions of seriousness and understanding. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(2), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1764907

- Wajda-Johnston, V. A., Handal, P. J., Brawer, P. A., & Fabricatore, A. N. (2001). Academic dishonesty at the graduate level. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1103_7

- Whitley, B. E., Jr. (2001). Gender differences in affective responses to having cheated: The mediating role of attitudes. Ethics & Behavior, 11(3), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1103_4

- Wilford, M. M., & Wells, G. L. (2018). Bluffed by the dealer: Distinguishing false pleas from false confessions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 24(2), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000165

- Wryobeck, J. M., & Whitley Jr, B. E. (1999). Educational value orientation and peer perceptions of cheaters. Ethics & Behavior, 9(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0903_4

- Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W. W., Manstead, A., & van der Pligt, J. (1998). The experience of regret and disappointment. Cognition & Emotion, 12(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379727

- Zhang, Y., & Yin, H. (2020). Collaborative cheating among Chinese college students: The effects of peer influence and individualism-collectivism orientations. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1608504

- Zhang, Y., Yin, H., & Zheng, L. (2018). Investigating academic dishonesty among Chinese undergraduate students: Does gender matter? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5), 812–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1411467