Abstract

This is the first paper to analyse the digitalisation measures that Jehovah’s Witnesses adopted during the pandemic and their behavioural consequences. The paper examines how the Witness community met the challenges of the pandemic by rapidly shifting to prerecorded and videoconference meetings, allowing online interaction between congregants. Based on a survey and focus groups, the effect of digitalisation of meetings on the feelings and attitudes to learning of Witnesses is analysed, investigating to what extent digitally-mediated religious services affected them in comparison with in-person meetings with regard to prayers, songs, speaking assignments, audience comments and social interaction, in both active and passive roles. The main conclusions are that digital meetings did not diminish their feelings of relationship with God or their intellectual learning, but performed less well than in-person meetings with regard to songs and social interaction. The authors reflect on how Jehovah’s Witnesses, while strictly upholding COVID-19 measures (they did not meet physically even where legally allowed due to their respect for life), navigated their feelings in the transcendent experience of uniting believers in a virtual environment.

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 marked a turning point for mankind (Beaunoyer et al., Citation2020). All aspects of human life were affected to some extent, including religious services (Baker et al., Citation2020; Ben-Lulu, Citation2021; Evener, Citation2020; Yezli & Khan, Citation2020). It changed the way in which many religions had been practising their rituals for centuries. It accelerated the recent tendency to use more technological resources and an evident change towards digitalisation (Campbell, Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2012, Citation2018; Campbell & Tsuria, Citation2022; Evolvi, Citation2021; Hutchings, Citation2015, Citation2017; Roso et al., Citation2020). Buonsenso et al. (Citation2020) state that one of the characteristics shared by the majority of religious events is the gathering of people to carry out their communal religious or spiritual practices, usually in enclosed spaces and, on many occasions, with a lot of physical contact, such as warm greetings, kisses and hugs. These kind of religious gatherings can be a vector for the transmission of viruses in a similar way as any other event involving gathering in groups (Liu et al., Citation2020; Quadri, Citation2020). On the other hand, closing or restricting access to places of worship might have negative consequences since it leads to the isolation of individuals and groups (Buonsenso et al., Citation2020). Phillips (Citation2020) traces the history of different religious groups’ responses to pandemics (including COVID-19). One of the major differences between the COVID-19 pandemic and former ones is that it has become relatively easy to move from face-to-face to virtual services (Wildman et al., Citation2020). According to Dowson (Citation2020), this was the logical step taken by some Christian churches because of the pandemic, simply, move worship online and use creativity to cope with the problems and situations faced by both parishioners and religious personnel (Adegboyega et al., Citation2020; Ahman & Thorén, Citation2021; Buonsenso et al., Citation2020; Campbell & Sheldon, Citation2021; Johnston et al., Citation2021; Pillay, Citation2020; VanderWeele, Citation2020). This can be viewed as the next step in an already-established trend: since the arrival of the Internet, digitalisation has been introduced into religious practices, although clearly the arrival of the pandemic has abruptly accelerated it. What were the effects of this sudden change carried out in the different religious communities, not only in their practices but at the individual level of their members?

In the specific case of Jehovah’s Witnesses this change is very obvious: even before the official lockdown was declared in many countries, they suspended their face-to-face religious meetings and started to carry them out remotely via the Internet. Despite the fact that the majority of countries allowed religious meetings subject to certain capacity restrictions and other measures, Jehovah’s Witnesses in Spain, and around the world, rapidly made the decision to suspend all face-to-face meetings. Initially, prerecorded meetings were used in Spain, then videoconference meetings were held by each congregation. The group went beyond the complex legal requirements of each autonomous region of Spain—Jehovah’s Witnesses endeavour to observe the law, but respecting the sacredness of life is even more important to them. They cancelled face-to-face meetings not only to prevent their members from being infected, but also to help curb spread of the virus in the communities where they live; they considered this a practical way to apply the Golden Rule “love your neighbour as yourself.” (Matthew 22:37–39, NWTFootnote1).

The digitalisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings affected them in many differing ways (Cardoza, Citation2019; Rota, Citation2018, Citation2019). To begin with, their in-person meetings were occasions to gather together in order to socially interact, to share their feelings and to show displays of affection, such as kisses and hugs, which were not possible digitally. Secondly, the digitalisation of meetings enhanced digital skills and competences of all their members. While young people are considered to be digital natives and the use of new technologies is easily learnt by them (Ng, Citation2012; Prensky, Citation2001), the elderly are usually considered digitally illiterate (Lind & Karlsson, Citation2014) and few efforts are promoted by organisations to help them to handle new technology. The digitalisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings has forced many of their members to learn new technologies, such as how to use both hardware and software to have a videoconference. Therefore, Jehovah’s Witnesses have been creating social value (Retolaza et al., Citation2020, Citation2018) by fighting against digital illiteracy, especially among the elderly which are a group of people usually forgotten by society with regard to development of digital skills. A third area of impact is that of spirituality, of which meetings are considered to be an essential feature—Jehovah’s Witnesses presented the highest percentage (85%) among surveillants in the Religious Landscape Study of the Pew Research Center (Religious Landscape Study, Citation2015) that analysed different religions with regard to the attendance at religious services. How has the digitalisation affected the development of their meetings or religious services? How have the computer-mediated meetings affected their behaviour, learning process and social interaction? How has this affected the emotions and attitudes of this religious group? Will this result, as stated by VanderWeele (Citation2020), in the loss of the spiritual life and the way of apprehending it: a loss of social connections in the group? These questions are investigated in this paper, which contributes to the field as it is the first paper to analyse the digitalisation process of Jehovah’s Witnesses during the COVID-19 pandemic. By means of both a survey and focus groups, this article aims to explain how prerecorded and videoconference meetings, in comparison with in-person meetings, affect the feelings and attitudes of Jehovah’s Witnesses in a spiritual, educational and social sense, by means of a quantitative and qualitative approach. This is the first paper that addresses this issue, as well as the first article to focus solely on Jehovah’s Witnesses that uses focus group methodology when analysing religion issues. The aim is to study the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Jehovah’s Witnesses’ spirituality, trying to delve into the sentiments caused by the abrupt change in their meetings’ typology. The study was carried out in Spain.

The religious landscape in Spain has always been dominated by the Catholic church, which had been the official religion since its inception as a country (XV century) and through to 1978, apart from a few years of religious tolerance in the 1860s and in the 1930s. Article 16 of the post-dictatorial Spanish Constitution, (Citation2018), which is still in force, gave religious freedom and declared that “there shall be no State religion” anymore. The proportion of Spaniards defining themselves as non-religious, agnostic or atheist (in the first quarter of 2022) is 38.7%, while 58.7% are Catholic (whether practicing or not) and 2.6% belong to other religions (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Citation2022, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). The latter group is a conglomerate of very different religions. Some of them have deep historical roots in this country, such as Judaism and Islam, despite their expulsion between the 15th and 17th centuries; others are more recent, but also historical, such as some Protestant denominations that were introduced throughout the 18th and the 19th centuries, or the Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses who are present in Spain since the beginning of the 20th century; additionally there are other religions that have been more recently present in Spain and which are, in many cases, fuelled by population movements on a worldwide scale due to globalisation or social conflicts, such as Hinduism, Pentecostal and Orthodox churches. According to Witnesses’ data (WTBTS, Citation2021), Jehovah’s Witnesses represent 0.26% of the total Spanish population, although Lawson and Xydias (Citation2020) say the official membership data should be multiplied by an average ratio of 2.07 to match those who identify themselves as Witnesses in the census.

The group now known as Jehovah’s Witnesses has a history of more than a century in Spain, starting before World War I. Around 1910 there is already evidence of its presence, although it was not until the mid-1920s and during the first half of the 1930s that their work spread to many regions of Spain. With the arrival of the Spanish Civil War (1936—1939) and the subsequent dictatorship of Franco, the existing Jehovah’s Witnesses in Spain had to go underground—like the other non-Catholic religions—and their public evangelizing work almost stopped. At the end of the 1940s, several groups of Jehovah’s Witnesses in different parts of the country were reactivated, developing since then, despite the conditions of persecution against any non-Catholic activity, an intense evangelizing work with which they achieved an increase in the number of members and the opening of numerous congregations or communities throughout the country. This outstanding increase continued through to the beginning of the 1990s. After a slight stagnation in the number of members, a growth of the group is observed again during the second decade of the 21st century. In 2006, its historical trajectory in Spain was recognized legally by the Spanish government by granting it the status of a “deep-rooted” (well-established) religion in the country (Stoklosa, Citation2016; Koch, Citation2007; Landing, Citation1982; Plaza-Navas, Citation2016a; WTBTS, Citation1977).

The research objective of this article is to analyse how the adoption of digitally mediated services–videoconferences and prerecorded meetings—during the COVID-19 pandemic affected Spanish Jehovah’s Witnesses’ behaviour, social interaction, learning process, emotions, feelings and attitudes in comparison with their in-person meetings, taking into account five different features of their meetings–prayers, songs, speaking assignments, audience comments and social interaction—in two roles: active and passive.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 will analyse Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings; Section 3 explains the digitalisation process of Jehovah’s Witnesses both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; Section 4 analyses the sample as well as the research methodology used; Section 5 presents and discusses the results obtained, and Section 6 gives the main conclusions of the article.

2. Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings

Jehovah’s Witnesses consider meetings an essential part of their behaviour (Beckford, Citation1975; Chryssides, Citation2016; Cronn-Mills, Citation1999). Meetings are vitally important to them, because through them they receive and strengthen their beliefs, values and the way to apply them in their lives. They regard meetings as something sacred that helps them to feel close to God, and as a channel through which they understand, strengthen and fortify their relationship with both Jehovah and his son, Jesus Christ (WTBTS, Citation1992, Citation1998, Citation2002, Citation2006b, Citation2009). Nonetheless, this spirituality, unlike some religious denominations, does not have an excessive emotionalism. The few works (Beckford, Citation1975; Holden, Citation2002; Ringnes et al., Citation2019, Citation2017; Stark & Iannaccone, Citation1997) that have addressed the topic of emotions in Jehovah’s Witnesses coincide on the fact that their meetings are less emotional than those of conventional Christian religious groups. Based on their understanding of the Bible, it cannot be denied that fellow feeling, joy, happiness, among other emotions, are manifested in their meetings. However, these emotions are evidenced in a much calmer and more moderate way than in other religions where gestures and sounds are expressed in more open ways.

When providing reasons to meet together for worship, a Witness article (WTBTS, Citation2016 April) explains how they are affected spiritually and emotionally as individuals and how they affect other members. Those who attend meetings are affected as individuals in three ways: 1) are spiritually educated, learning about God and how to apply Bible principles in their daily lives; 2) are encouraged and emotionally strengthened by listening to talks, audience comments, songs and conversations before and after the meetings to “feel a sense of belonging”, and 3) feel they are brought under the influence of holy spirit.Footnote2 In regard to how they affect others by means of attending meetings, two main ideas are discussed. Meetings give them the chance to show love among themselves, given that they consider their “fellow worshippers worthy of” their “time, attention, and concern,” and it is reasoned that giving comments and singing spiritual songs encourages others. Meetings unite fellow believers as a spiritual family to be loved and cared for.

From an exhaustive analysis of Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings, five features or dimensions are identified as part of their worship which generates different feelings when having an active as well as a passive role.

First, spiritual songs are sung at the beginning and at the end of every meeting, large and small. Another song is sung in the middle of meetings as a prelude to the next section. Songs are sung by all in attendance while standing with a sober and reverential attitude. On the platform, there is no chorus but only the meeting’s chairman. Songs are considered to be praise offerings to their God, Jehovah (Chryssides, Citation2014; Plaza-Navas, Citation2013, Citation2016b).

Second, prayers are also held at the beginning and at the end of meetings. One member of the community represents the whole congregation in a short public prayer (WTBTS, Citation1986, May 15). The rest in attendance reverentially bow down their heads during the prayer and say “amen” at the end. Prayers are considered to be sacred and no one in the auditorium talks or does anything else but listen attentively to it, given that it is considered to be talking with Jehovah. In the initial prayer, God’s blessing upon the meeting as well as his holy spirit is asked, among other things. In the final prayer, God’s help by means of his holy spirit is usually asked to apply in daily life the Bible principles that have been considered.

Third, once the meeting is opened with song and prayer, pre-scheduled assignments take place. These vary in length from 2 minutes to 30 minutes and are carried out by all members of the congregation, young and old, men and women. They can also differ in the way they are delivered, such as talks, readings, discussions or dramatisations. Delivering assignments is considered a way to praise God and to spiritually encourage others. Listening attentively to the programme is considered not just an intellectual exercise to increase Bible knowledge but a way to cultivate spirituality—they consider that they are being taught by Jehovah.

Fourth, some parts of the meetings are carried out by means of reading an article or a section of a book edited by Jehovah’s Witnesses and discussing what is written along with the cited Scriptures. The articles are supplied with questions for discussion, and the conductor asks both these and additional questions; thereafter, all members, even the youngest who are learning to speak, are allowed to participate by means of their comments. Those who want to participate raise their hand and the conductor selects who will give the comment. Comments are considered to be a praise offering to God and a way to encourage one another. Comments are linked to the offering of sacrificial animals under the Mosaic Law, according to Hosea 14:2 (NWT) “offer the praise of our lips as we would young bulls” (WTBTS, Citation1956, Citation2006a).

Fifth, social interaction between congregants is carried out before and after each meeting in order to “consider” and “encourage one another” (Hebrews 10:24,25, NWT; see, (WTBTS, Citation1989,, June)).

Jehovah’s Witnesses’ meetings have evolved in their name, format and number over recent decades. Currently, midweek meetings, weekend meetings, field service meetings, assemblies, conventions and the Memorial of Jesus’ death are carried out (WTBTS, Citation2019, Citation2020b).

Midweek meetings are usually held on a midweek evening. These meetings focus on a portion of the Bible (normally two chapters or more) from which several lessons are drawn. As in all their meetings, Jehovah’s Witnesses start with an opening song and a prayer. Then the chairman makes a brief explanation of the meeting’s contents, which follows the same pattern: “Treasures from God’s word”, a 10-minute talk in which two or three points from the analysed portion are explained. “Digging for Spiritual Gems”, a 10-minute question-and-answer section with the participation of those in attendance (rising their hands when they want to offer a comment). A 4-minute Bible reading of an assigned Bible portion without any additional explanation from the reader is presented. Then, a different section entitled “Apply yourself to the field ministry” begins, which is designed to help them to improve their preaching and teaching skills. To this end, they watch videos with sample conversations similar to those they may have when they speak with others about religion. Afterwards, some participants present their own dramatisations about different situations in which they preach. Occasionally, a 5-minute talk is scheduled to conclude this section. They sing a song to introduce the following part, “Living as Christians”, in which by means of talks, discussions or videos advice is offered about how to apply God’s Word. Finally, in the section “Congregation Bible Study”, they analyse by means of questions and answers a portion of their publications. The meeting is concluded with a song and a prayer. The whole meeting lasts 1 hour and 45 minutes.

On Saturday or Sunday, Jehovah’s Witnesses hold the weekend meeting that is divided into two parts: in the first one a 30-minute public talk (dealing with a variety of topics related to the Bible) is delivered, followed by a question-and-answer analysis of an article published in the Watchtower magazine. The whole meeting lasts 1 hour and 45 minutes.

Each congregation also schedules field service meetings during the week—brief gatherings (five to seven minutes) to organize them to participate in the diverse activities related to their preaching work. Each year a very special celebration is held by Jehovah’s Witnesses: the Memorial of Jesus’ death. Jehovah’s Witnesses also organise larger gatherings called assemblies and conventions, amalgamating different congregations.

This paper focuses on the behaviour and feelings derived from midweek and weekend meetings. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, these meetings were held in their places of worship, known as Kingdom Halls. Over the last few years, arrangements had been made to make telephone or audioconferencing connections available for the members of the group that, because of illness or other different reasons, were not able to attend the meetings face-to-face. This way, they can be present “at a distance” in this spiritual activity that is so important to Jehovah’s Witnesses, not only listening to but also participating, to a certain degree, in songs, prayers, talks and comments. Nonetheless, these were just specific, not widespread, situations. The pandemic required a greater change, since from March 2020 to March 2022, all over the world, all meetings were held only virtually, apart from a pilot project announced on 15 October 2021 to restart some in-person meetings at reduced capacity in countries where COVID rates were lower (WTBTS, Citation2021).

3. The digitalisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses

Brennen & Kreiss (Citation2016) distinguish between “digitisation” as the process of converting information into digital form, and “digitalisation” as the resulting social changes. In the case of Jehovah’s Witnesses (JW), the most prominent driver of digitalisation has been the digitisation of JW literature. The network of 80 or so branch offices around the world, responsible for literature production and country-level organisation, called Bethels, have been digitalised since the 1980s (with ongoing developments), but the change that affected the over 8 million active members more directly was the recent digitalisation of the almost 120,000 local congregations and their meeting and study activities.

3.1. The digitalisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses before COVID-19 pandemic

The organisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses has never been averse to making selective use of new technology to strengthen the spirituality of their members (Cardoza, Citation2019; Chryssides, Citation2016; Rota, Citation2018, Citation2019) Chryssides (Citation2016, Citation2018) notes their early adoption of newspaper syndication, moving pictures with synchronised sound in the silent-movie era (accomplished by playing a gramophone while manually adjusting the projector’s frame rate for lip synchronisation), and, later, syndicated radio broadcasts. Textual publications of Jehovah’s Witnesses are notably multilingual: Jehovah’s Witnesses’ official website jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) currently has some 1000 languages including 100 sign languages. In the 1980s they developed a proprietary computer system called “MEPS” for internal handling of many languages at the branch-office level, including tracking translation decisions and assisting with typesetting, which facilitated expansion of their work translating Bibles and other literature.

The first large-scale effort to ship digital publications in a form readable on non-MEPS computers was the Watchtower Library application, first published on CD-ROM in 1994. The 2021 English edition organises and hyperlinks some 137,000 printed pages, much of which are hyperlinked to their equivalents in other-language editions. Watchtower Library’s primary limitation is the requirement for a desktop Windows PC (apart from a port to Microsoft’s ill-fated “Windows Mobile” platform from 2009 to 2015, and unofficial efforts to improve the WINE project to make Watchtower Library work on Mac and GNU/Linux).

Jehovah’s Witnesses’ online presence began in 1997 with a limited set of publications in few languages; in 2010 a new site jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) released many more publications as PDF (and MP3 audio, replacing the tapes of the 1980s and CDs of the 1990s). The webmaster of Pennsylvania University’s journal “Sino-Platonic Papers” noted the PDF files used the internal MEPS character set, which limited search and copy functionality in most languages, but praised the Chinese articles with “pinyin” phonetics as exhibiting unusually correct orthography (Swofford, Citation2011). In 2012 Watchtower Library was ported to use standard HTML and placed online, branded “Watchtower Online Library” or WOL, with full search and select/copy functionality in all languages. Older publications were added in 2018 and pinyin in 2019. Audio files were also integrated into WOL and time-indexed by paragraph.

The 2013 JW Library app is an offline-capable packaging of this material which substantially affected the community’s attitudes toward technology as noted by (Cardoza, Citation2019). It also marked the first digital publication of older Bible editions historically distributed by Watchtower, including Byington, the Kingdom Interlinear, the American Standard Version and the King James Version, which corresponds with the Pure Cambridge Edition in all verses we checked.

The jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) website increased its video output from 2014, by means of a monthly programme branded “JW Broadcasting” plus other videos, nearly all of which are dubbed into many language versions, and are also available via the JW Library app for either streaming or download (in multiple picture sizes). Videos in 100 sign languages are also produced (both to transcribe the spoken videos, and also to sign the Bible and printed articles), and a separate version of the JW Library app exists to assist with the navigation of these sign-language videos. The organization of Jehovah’s Witnesses subscribes to commercial Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) to ensure the release of a new video does not result in a traffic spike that overwhelms the jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) servers; this move made it possible to run virtual events in which millions of members simultaneously watch a video.

Prerecorded videos of weekly meetings are placed on jw.org’s (WTBTS, Citation2022) “log in” section by special arrangement for groups and individuals under extenuating circumstances that preclude their attendance in person, or where qualified individuals to lead the meetings are not locally available. For example, some foreign-language groups, composed of members learning a new language for the purpose of preaching to an immigrant population, have watched prerecorded video meetings as a group if they are not yet sufficiently competent to run every meeting themselves in that language.

3.2. The digitalisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings during COVID-19 pandemic

While Watchtower Library enabled the digitalisation of some members’ personal Bible study and preparation for meetings, and the JW Library app and the jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) website increased the digitalisation of members’ use of study material during meetings, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic these meetings were still being held in person at Kingdom Halls, and so it was necessary to coordinate a rapid digitalisation of the meetings themselves.

The COVID-19 pandemic proved to be a catalyst of digitalisation among Jehovah’s Witnesses. Initially, Jehovah’s Witnesses cancelled some circuit assemblies (large gatherings of 20 congregations or so); normal meetings were not yet cancelled in Spain but were instructed to use disinfectant, to be avoided by those with health issues, and microphones were to be placed on poles to avoid individuals needing to hold them. These instructions were rapidly changed so that all meetings were cancelled, and this occurred before the official lockdown in many countries (Table shows when the last in-person meeting of Jehovah’s Witnesses was held in different countries and the official lockdown date). JW activities continued to be online only until 31 March 2022 (WTBTS, Citation2022a), even though they could legally have been held earlier as religious services were allowed in many countries with some attendance constraints.

Table 1. Last in-person meeting and official first lockdown

At the beginning of the pandemic, the initial recommendation was to use prerecorded video meetings, but this was replaced within days by a recommendation to use Internet videoconferencing, with telephone fall-back for those who did not have videoconference-capable equipment.

The shift from prerecorded video meetings to realtime videoconferencing was likely undertaken because prerecorded meetings rule out participation during meetings and social interaction around them; this shortfall is mitigated if members are able to join congregations’ videoconferencing groups for discussion (typically Zoom software is used). Many members would still very much prefer to meet in person, but have refrained from doing so due to the ongoing COVID-19 concerns.

Notably, the Memorial of Jesus’ death was held over videoconference near the start of the pandemic, and attendees were encouraged to create their own emblems by making unleavened bread at home and purchasing unfortified wine. In some parts of Africa where videoconferencing was not feasible, arrangements were made with local broadcasting stations to broadcast a prerecorded Memorial as well as some other meetings. A prerecorded Memorial (and associated Special Talk for newly-interested people) was also posted on the jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) website, which received some seven million visitors on Memorial day. Jehovah’s Witnesses normally make an exact count of the total worldwide Memorial attendance for publication in their annual report, but in 2020 there is considerable uncertainty because it is not possible to ascertain precisely how many viewers there were for the broadcast meetings.

Perhaps the Witnesses’ most substantial use of video was the 3-day convention of 2020, which due to COVID-19 precautions was not held live at regional venues but was entirely presented on video, dubbed into over 500 languages by volunteer translators at short notice largely working from home, and for the first time also included an audio-described version for blind and low-vision viewers (extended in 2021 with spoken lyric prompts in the songs). Viewing of this video presentation was supplemented by videoconference gatherings after each session at the local congregational level, during which members could discuss what they have seen in small-group “breakout” rooms.

The jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) website’s video output in general was increased during the pandemic, including a regular stream of “Governing Body updates” regarding the pandemic itself, which urged members to continue following safety precautions as a way to show respect for the sanctity of life.

4. Sample and methodology

A questionnaire was prepared to analyse the feelings that Jehovah’s Witnesses experience when attending meetings in three different scenarios: 1) in-person (IP) meetings in the Kingdom Hall; 2) prerecorded (PR) meetings; 3) videoconference (VC) or live online meetings. The questions were focused on the main five features or dimensions of meetings, namely, prayers, songs, speaking assignments, audience comments, and social interaction, in a twofold perspective according to the roles displayed: active and passive. To illustrate, we ask about the feelings Witnesses experience when saying a prayer (active) and when listening to a prayer (passive). The 5-point Likert Scale was used, and free text responses were allowed to be given at the end of each section of the questionnaire.

The authors contacted the Office of Public Information of the Spanish Branch of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Madrid by means of a telephone call. Afterwards, different videoconferences were held. The aim of the paper was explained and, initially, their cooperation only in the distribution of a questionnaire link among interviewees was asked. Once permission was obtained, it was additionally asked to conduct focus group meetings with Witnesses of different ages, and to use a sample of 48 Witnesses (with parity in gender) distributed in 4 groups according to the following ages: 1) older than 65, 2) between 50 and 65, 3) between 30 and 49 and 4) younger than 30. Table shows the demographic descriptive analysis of the sample, including age, years after baptism as one of Jehovah’s Witnesses, gender and marital status. 46 Witnesses attended the focus group meetings and answered the questionnaire, giving a sample size similar to those used in religion papers published in journals indexed in Web of Science and ranked in significant positions by Journal Citation Reports (Hall, Citation1998; Sullins, Citation2000; Williams, Citation2013). Only a few papers have used the methodology of focus groups in studies of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Catré et al., Citation2014; Cronn-Mills, Citation1999; Kaiya, Citation2013; Kamanga, Citation2016; Lachland, Citation2007; Muyoba, Citation2015), of which only one (Catré et al., Citation2014) is present in the Scopus database and none in WoS. Catré et al. (Citation2014) used focus groups in a multi-religion study, with only three Witnesses compounding a single focus group when validating a questionnaire about quality of life. Lachland (Citation2007), in another multi-religious study addressed to medical staff, used a focus group composed of 6 to 8 Jehovah’s Witness participants. The other four works that have been found are exclusively focused on Jehovah’s Witnesses: Kaiya (Citation2013), in a study about religious persecution, conducts a focus group of JW women, without stating the number of participants; Kamanga (Citation2016), focusing on public schools, conducts a focus group of 6 JW women; Cronn-Mills (Citation1999), focusing on the social construction of Jehovah’s Witnesses, conducted group interviews with 43 Jehovah’s Witnesses; Muyoba (Citation2015), in a work about medical issues, used a larger number of participants, conducting seven focus groups each with eight Jehovah’s Witnesses. In addition to these studies in which focus groups are composed exclusively of Jehovah’s Witnesses, there are other works in which some of the focus groups conducted included members of this religious group (Freire et al., Citation2016; Mika, Citation2006; Wood & Hilton, Citation2012). Therefore, a significant contribution to the field of this article is being the first religion paper that focuses solely on Jehovah’s Witnesses that uses a focus group methodology.

Table 2. Descriptive of the sample

Focus-group methodology is in fact widely spread among scientific research. Focus groups are a proven method of obtaining qualitative data by means of conducting group interviews in which participants, in a conversational way, express their opinions, interests, experiences, feelings, emotions, etc. with regard to some questions posed by the moderator in order to guide the conversation; participants are free to interact in a dynamic way (Bloor et al., Citation2001; Kamberelis & Dimitriadis, Citation2013). The objective is to obtain information pertinent to the spectrum of the dimensions, or aspects of interest, for which the group is being studied. The obtained information, after conducting a pertinent analysis, allows deriving an insight of these dimensions in a context similar to the one in which everyday interpersonal conversations take place. When participants overcome their initial reticence and fear, and a comfortable environment is created, group conversations turn out to be of great interest and provide relevant information. The objective is not that the group reaches a consensus on the topics to be discussed, but rather to obtain their opinions and reactions about them and, if possible, about the sentiments and emotions involved. Focus groups are a technique that can be complemented by or that can complement the data obtained by means of other qualitative methods, such as individual interviews, questionnaires and participant observation. As stated earlier, in this work it was decided to choose the option of combining focus groups with questionnaires with multiple choice and free-text answers. The statements literally transcribed in the text are identified with FG#-P#, being FG = Focus Group and P = Participant, and Q#, being Q = Questionnaire.

The four focus groups were arranged and agreed with the Office of Public Information of the Spanish Branch of JWs. This way, they were carried out in a short period of time, from December 23rd to 28th, 2020. The restrictions in Spain because of the pandemic made it impossible to carry out the focus groups face-to-face. All participants were invited at a specific day and hour to conduct the focus group via videoconference. All participants connected, with the exception of two in the group aged between 50 and 65 years old. In all groups, some minutes were spent to create a good atmosphere by ensuring that it would be totally anonymous and by explaining some aspects, such as how the methodology works, the kind of topics that were going to be addressed, that they were going to be recorded (they had been notified in advance about this aspect and none of the participants had objected), that they could express themselves freely, in particular with regard to their feelings and attitudes toward the meetings, the expected duration, and so forth. At the beginning of the focus groups, some demographic questions were posed in order to obtain data about their age, the geographical location of the place where they attend religious meetings and for how long they have been members of Jehovah’s Witnesses. This data was used only to double-check that the respondents to the questionnaire were the same subjects as the members of the focus group, finding no anomalies. The duration of each of them ranged from 1 hour and 38 minutes in the case of the group composed of the youngest ones, to 2 hours and 31 minutes in the case of the group composed of those aged 65 years and over. Two of the three authors of this work acted as moderators. The videoconferences were recorded and afterwards were transcribed in order to analyse them.

By means of both the on-line questionnaire and the focus groups, different feelings and attitudes were asked and discussed in regard to the feelings Witnesses experience in in-person, prerecorded and live online gatherings. Whereas the role of the questionnaire was to provide quantitative information, the role of the focus group methodology was to obtain a deeper qualitative analysis. Therefore, both methodologies complement one another.

First, two feelings were considered for active and passive roles in regard to prayers: feeling close to the Lord (#1 and #3); and feeling that a reverential act to God that prepares the mind and heart for spiritual matters is performed (#2 and #4).

Second, as far as songs are concerned, four feelings and attitudes were considered for the active role (singing songs): feeling that they praise God (#5); that emotions are awakened (#6); sense of group belonging (#7); and showing from their active participation that songs are part of the spiritual programme (#8). This last feeling was not considered when assessing the passive role, namely, listening to songs (#9 to #11).

Third, when handling assignments (active role) five feelings were analysed: feeling of praising God (#12); feeling of teaching effectively (#13); feeling of encouraging others (#14); sensing the reactions of the audience (#15); and feeling of reaching the hearts of others (#16). On the other hand, six feelings were taken into account when analysing the passive role (listening to assignments): feeling of paying full attention (#17); sense of being distracted (#18); feeling of learning intellectually (#19); feeling of being taught by God (#20); feeling encouraged (#21); and feeling emotionally close to the speaker (#22).

Fourth, the same feelings of assignments were considered in regard to comments for both active (#23 to #28) and passive (#29 to #34) roles, with the exception of #24 where feelings of teaching effectively were substituted by feelings of communicating effectively. Additionally, a sixth feeling was introduced in the active role, namely, if they feel more motivated to offer comments.

Fifth, with regard to interaction between Witnesses before and after the meeting, two feelings were considered for both roles (active and passive): feelings of encouragement (#35 and #37) and perception of personal interest (#36 and #38). Additionally, for including both roles, two more items were taken into account, namely, if they considered themselves to have meaningful (#39) and personal (#40) conversations.

Sixth, when considering meetings in general, the following feelings were considered: motivation to attend (#41); feeling of being close to God (#42); happiness (#43); feeling spiritually strengthened (#44); feeling part of the meeting (#45); sensing the strength of brotherhood feelings (#46).

As the 5-point Likert scale is ordinal, a non-parametric analysis was carried out (Jamieson, Citation2004). Three Kendall’s correlation coefficients were calculated, as well as their significance, for each feeling analysing the following combination of variables (or scenarios): 1) in-person and prerecorded; 2) in-person and videoconference; and 3) prerecorded and videoconference. The null hypotheses to be tested are whether variables are dependent, in other words, whether feelings perceived are the same in the analysed scenarios. If correlation is significant (<0.05), the hypothesis will be rejected and it can be assumed that there is no difference in the feelings derived by congregants among these two sets of meetings. If correlation is not significant (>0.05), the null hypothesis will not be rejected and, therefore, it may indicate that congregants do not derive the same level of feelings in this scenario.

5. Results and discussion

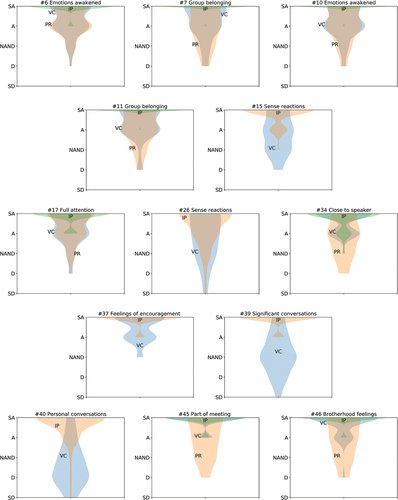

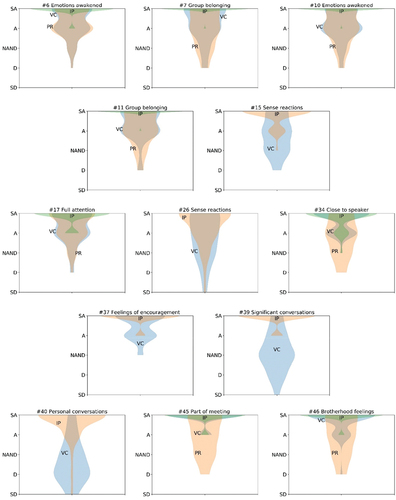

Every single feeling correlates significantly between prerecorded and videoconference meetings. Therefore, this indicates that the difference in the feelings derived by congregants between these two kind of meetings is not significant. Conversely, some feelings (see, Figure ) do not correlate significantly between in-person and online meetings.

Figure 1. Not-correlated feelings.IP: in-person; PR: prerecorded; VC: videoconference. SD: strongly disagree; D: disagree; NAND: neither agree nor disagree; A: agree; SA: strongly agree

These results confirm that congregants in virtual meetings, whether they are prerecorded or even live videoconferences, cannot experience the same level of intensity in some feelings as those felt in person. The discussion of the results by dimension, both quantitative (correlations) and qualitative (focus group), will be addressed in the following paragraphs.

5.1. Prayers

Public prayers in Kingdom Halls can be delivered only by baptised men. According to Table , in all feelings (#1 to #4), the Kendall’s coefficient is significant which shows that the correlation among the feelings experienced in the dimension of prayers in the three different kind of meetings (in-person, prerecorded and videoconference) is significant. Therefore, we can conclude that feelings of this dimension are correlated. In other words, the kind of meeting has not impacted significantly in the feelings derived by congregants in regard to prayers.

Table 3. Prayers

When offering prayers (active role) there is correlation and a possible explanation can be the fact that Jehovah’s Witnesses do not use images in their worship, therefore, they feel close to the Lord no matter where they are. Many close their eyes when praying, although this is not mandated in their publications. The answers obtained in the focus groups show that offering prayers is a very important aspect of their worship and meetings, whether they are held face-to-face or not, at their places of worship or at their homes, and whether in a small or large group. Prayers are the means they use to speak directly, representing those in attendance, to their God. They think that what matters is the message conveyed and not the means used to convey it. Three of the participants expressed that:

I, in my opinion, have not seen any change. I mean, prayers are not recorded, they are always live, even in streaming. And, these are our feelings in front of Jehovah. I personally have not seen any change in brothers. I have perceived a change, probably, in the depth of what is said. (FG-P20)

The setting in which it is done does not affect the feelings of respect and closeness to Jehovah when prayers are offered or heard (Q7).

Prayers are with Jehovah, the context where they are offered does not matter. (Q38)

When listening to prayers (passive role), as prayers are not recorded by the Witnesses, when watching a prerecorded meeting, the playback of the video is stopped and the family head offers a prayer for the family. Therefore, prayers in prerecorded meetings are tailored to the needs of the family. Correlated results suggest that the relationship with God among Jehovah’s Witnesses has not been affected by the fact that meetings have been conducted on-line over the last months. This is in line with Catré et al. (Citation2014) who conclude that Jehovah’s Witnesses have strong convictions, which include strong connection to a spiritual being and faith. Due to the exceptional situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the emotional connotations involved, some of the participants in the focus groups highlighted an increased depth in the prayers’ contents and the sentiments with which they are offered, an improvement of their quality, even feeling closer to God. With regard to hearing prayers in videoconference meetings, most of the focus group participants say it has not brought about any change for them. As shown by some comments obtained in the focus groups, which are transcribed below, they still feel close to Jehovah; prayers reach their hearts and they feel identified by the prayers’ contents. Many of them also close their eyes when they hear prayers in order to concentrate on what is being said. The channel used does not influence them.

I feel highly identified with the prayers offered, and they fill me as much as when we were in the Kingdom Hall […] for me they have the same value, they reach my heart in the same manner. And, I truly feel very identified (FG1-P12).

You could not see God when you were in the Kingdom Hall, could you? But you could see the brothers. Nothing has changed about God because, at the end of the day, it is all the same with him (FG4-P40).

Prayers always reach my heart (Q4).

When someone offers a public prayer, they represent all those who are at the meeting on this occasion. Therefore, we are interested in listening to what is being said […] we consider that closing our eyes is a way to focus our attention on what is being said (FG2-P22).

I feel it is one of Jehovah’s provisions and, for this reason, I appreciate them either way (Q2).

5.2. Songs

Jehovah’s Witnesses sing their songs to a prerecorded musical accompaniment. Despite the fact that there is not an explicit prohibition against live music, in Spain it is not used at regular meetings. When singing over videoconference, the method they adopted was to mute all participants: participants can see each other sing by watching each other’s lips move on-screen, but cannot hear each other sing. This is because early experiments singing without mute resulted in confusion due to differing audio latency between the prerecorded accompaniment and others’ voices. There do exist open-source projects that attempt to address this issue, such as SoundJack, but these require high-end infrastructure to all participants plus a local server setup (since any involvement of large distant data-centres such as Zoom’s would result in an unacceptable increase of latency, so SoundJack must be run on local servers run by the participants themselves, who should ideally share the same Internet Service Provider), so it is understandable if the organisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses decided not to suggest each congregation attempt the technical process of setting up a local SoundJack server—observing others sing on-screen appears to be an adequate compromise. The attempts mentioned in the focus groups to sing all together by videoconference were unsuccessful in all cases, as one of the participants said “it was cacophonous” (FG1-P3). In general, these attempts took place at the beginning of the lockdown, motivated by the best of intentions, but it was technically unfeasible. This option was rapidly dismissed and they began playing the music, displaying the lyrics on the screen but turning microphones off.

When singing songs, according to Table , feelings that deal with praising God (#5 and #9) as well as active participation in both roles have not been affected by virtual meetings. Nonetheless, the Kendall’s coefficient is not significant for emotions awakened (#6 and #10) and group belonging (#7 and #11) in both active and passive roles, where the highest feeling sensation is obtained in person. We can conclude, given that there is no correlation between in-person and virtual meetings (either prerecorded or videoconferences) in these feelings, that, to some extent, the virtual environment has affected their emotions in this regard, given that the results for on-line meetings are lower than in person. Since there is significant correlation between prerecorded and videoconferences in the aforementioned feelings, it seems that Zoom meetings—where congregation members can see but not hear congregants singing—have not fully addressed the lack of emotions awakened as well as the feeling of belonging to a group when singing.

Table 4. Songs

Songs are a key element for the participants of focus groups. As one of them said: “for us, singing is a way to praise Jehovah, is a way to worship him” (FG4-P40). In fact, one of the recurrent wishes when they were asked what they do miss in the current meetings, is clearly “singing with our brothers”. Some of the participants felt that “this is the aspect of the entire meeting that has been the biggest loss” (FG2-P19), “for me this is probably the hardest thing to cope with in this situation” (FG3-P34) or “this is what I miss most” (FG4-P43). Another participant expressed this emptiness as follows..

While prayer is a moment of individual seclusion, music in a group is not. It lifts, it is something very special. For me this is the most changed aspect and what I miss the most. I mean, I sing. Yes, yes, I read and sing, but it cannot be compared. I love how I feel when I am at the Kingdom Hall sharing music. It is a shared sentiment. And, yes, I miss it. (FG1-P7)

As mentioned, for both roles, feelings of praising God and considering songs as part of the spiritual programme present are correlated, whereas the feelings with significantly lower performances in online meetings are sense of group belonging and emotions awakened. These results show the difficulty of deriving the same level of emotions in an online environment when singing spiritual songs. During focus group discussions, they express a clear longing for face-to-face meetings that videoconference meetings cannot yet satisfy. Despite the fact that they can follow the music and the lyrics at home, they try to put the same sentiments but “the motivating effect of listening to others is a great loss. Zoom cannot compensate for it” (FG2-P17). Others expressed themselves saying that it was hard “not hearing their brothers” (FG2-P15), that “singing alone is very sad, very sad” (FG4-P39) or “my emotions were more intense when I was singing together with the brothers at the Kingdom Hall” (Q5). In this regard, some members of the focus group suggested the viability to play songs with a chorus singing, which are available in some languages, so as to stimulate the sense of hearing, as expressed in the following statement..

On some occasions, I have even thought about suggesting that we could sing with the choir […]. Maybe it would be nice that brothers could follow the songs’ lyrics as they hear the choir. (FG1-P3)

5.3. Assignments

In regard to handling assignments (active role), prerecorded meetings have not been taken into account given that no member of the sample delivered an assignment in these meetings that are directly recorded by the national branch office of Jehovah’s Witnesses (known as Bethel among Witnesses). Table shows the results obtained in this dimension for both roles.

Table 5. Assignments

When delivering assignments (active role), all feelings are correlated, with the exception of sensing the reaction of the audience, where in-person meetings perform better (#15). This makes sense given that it is difficult to perceive the reaction of the audience by means of a videoconference, despite the fact that some members do open their cameras while the speaker is delivering a talk. Perhaps it is because, even if they have their cameras open, their sizes on the computer, tablet or mobile screens is very reduced and the reactions cannot be clearly seen. One of the interviewees in the focus groups said that, even with the cameras open, it is “quite colder […] and on Zoom a lot is lost” (FG2-P17). Another participant expressed it as follows..

I can see that the brothers are there, yes, they are there, but I don’t know if they are paying attention or not, because they don’t look at the camera. They are looking at the screen, to a different point of the screen, which maybe is where I am. This is something that you, as speaker, as orator, cannot perceive and it is like doing it blindfolded (FG1-P9).

By contrast, some of the interviewees expressed how they feel when they deliver talks in congregations where many cameras are turned off as follows..

I don’t know if I have reached the heart of this audience, of this congregation (FG1-P5).

I think that nobody is listening to me (FG4-P37).

I don’t know if I am talking to myself or if there is someone out there (FG3-P29).

I felt like asking ‘can you hear me?’ Because I don’t know if I am connected or not. Because, I do need an audience nodding, laughing or blinking. Even a little bit (FG3-P23).

Likewise, when listening to assignments (passive role), most feelings are correlated, with the exception of paying full attention (#17) between in-person and prerecorded meetings, where the former perform better. Some interviewees mentioned that it is difficult for them to fully concentrate on the programme when watching prerecorded meetings. One of the focus group participants made a vivid comparison when saying “it is just like watching someone eating, while you are not doing it!” (FG3-P24). When it comes to videoconference meetings, there are diverse opinions. One participant said “I can concentrate properly” (FG1-P2), whereas another said “I find it hard to be more focused” (FG3-P28) or “it takes a lot of concentration” (FG3). Paying full attention to meetings is a very important issue among Jehovah’s Witnesses, and is frequently mentioned in the opening prayers, where they ask Jehovah’s blessing upon them to fully concentrate on the material that will be analysed; their publications also encourage them to pay careful attention at the meetings. One of the interviewees mentioned that “ultimately, we are aware that a meeting is a moment to learn more about God and praise him” (FG3-P26).

On the other hand, it is interesting that the perception of being taught by God (#20) is perfectly correlated among all meeting types, which shows that Jehovah’s Witnesses continue to consider meetings as a way of listening to their God no matter what the medium. Some of the following comments obtained in the focus groups refer to this aspect:

What matters is the information! If you understand that what is being said comes from the primary source, which is God’s Word, with regard to the way to convey it, each person will do it in a different way, or perhaps the way to express it. But, actually, what we appreciate is the basis, the source, and this source is unalterable. All the information comes from the same place; therefore, I can see that it reaches me personally (FG1-P12).

I think Jehovah is taking care of us. He is using the methods that exist today and, as for me personally, my trust in God has increased (FG3-P32).

Despite the present adversities, the channel to nourish us remains open. So, it is really praiseworthy (FG4-P42).

I am amazed that the organization has been able to maintain the meetings in the same format. Providing the same teachings as before. And, I think nothing has been lost in comparison with before. (FG4-P41)

Really, the only thing that has changed is the method, but the teachings are the same. We keep using the same food, the Bible. Everything is the same. The only difference is that, instead of being there physically, we are there virtually (FG4-P35).

5.4. Comments

As far as offering comments (active role) is concerned, prerecorded meetings have not been included given that no member of the sample delivered assignments in this type of meeting. Table shows the results obtained in this facet of Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings for both roles.

Table 6. Comments

When offering comments (active role), all feelings are significantly correlated except sensing the reaction of the audience (#26), where in-person meetings perform better. Some of the interviewees explain that “when I prepare a comment to benefit those who are going to hear it, for me it is the same, because I give it the importance it really deserves […] for this reason I prepare them in the same way” (FG1-P5); “I used to prepare them as best I could, and I keep doing the same, I have not lowered my standards” (FG1-P8); or “after all, you need to prepare in the same manner and you offer the comment in the same way, and the same people listen to you” (FG4-P36). With regard to feeling the audience’s reactions to their comments, one participant said:

There is something that helped me with comments […] now, I can see the brothers’ faces when I am offering a comment, and it helps to focus on someone and think that this comment might encourage or help them in this moment. Formerly, you offered a comment and all you could see was the back of the head of the person sitting in front of you (FG3-P28).

At the meetings on Zoom, I feel like seeing brothers giving comments or just listening (Q3).

Before, when you offered comments in the meetings, you did not have all the eyes looking at you. […] But now they are, and you know it. Absolutely, everyone is looking at the camera! (FG4-P43).

Similarly, when listening to audience comments (passive role), most feelings are correlated between in-person and prerecorded meetings, except feeling close to the speaker (#34), where in-person meetings perform better. Logically, they feel not so close to people who are not part of their congregation when they cannot see their faces, given that the camera does not register the face of those who offer comments in prerecorded meetings. One of the focus groups’ conversations reflects it as follows:

Being with your congregation is just as being with your family, isn’t it? And seeing familiar faces! […] But meetings on streaming are the official thing (FG3-P24).

Yes, a passive observer (FG3-P23).

Yes, that’s it! You are like a passive observer! (FG3-P24).

It was as if it wasn’t about us! We also were like this for two weeks during which, even though I enjoyed the level, because their comments and preparation were really very good, I really enjoyed them, but […] I felt separated because I couldn’t offer a comment. The assignments were not made by anyone from my congregation. So, I couldn’t commend anyone or talk about anything with them (FG3-P30).

Once again, the perception of being taught by God (#26) presents high levels of correlation, which indicates that Jehovah’s Witnesses consider their meetings, virtual or otherwise, a channel where God communicates with them. Some of the interviewees put it this way:

I am completely convinced that our God Jehovah can teach us by means of a comment offered either by a child or by an adult. There is no doubt in my mind […] all what is said at the meetings […] is for me a divine teaching and I accept it as such (FG1-P8).

Is a way to appreciate what is being said, a way of learning, of keeping for ourselves what is said, the relevance of their comments. Because everything is based on the Bible and it reaches us (FG1-P4).

5.5. Interaction

No interaction among congregants occurs when watching prerecorded meetings. Therefore, the prerecorded format was not included in the questionnaire for interaction. Table shows the results obtained in this dimension for both roles in the other two formats as well as two kind of conversations (#39 and #40) that may affect how they feel in both active and passive roles.

Table 7. Interaction: in-person vs. videoconference

Despite the fact that they perceive no difference in regard to how others feel (#35 and #36), there is no correlation in how they feel encouraged by others (#37). The highest values are obtained in person. Many interviewees mentioned that what they miss the most is physical contact, namely hugs and kisses. We need to take into consideration that this trait is very specific to Spanish culture; future studies developed in other countries should analyse if this also happens among Witnesses where this method of showing affection is less common (for instance, Korea, Japan, or to some extent England). All in all, digital interaction does not seem to be a perfect substitute for in-person meetings. When they are asked what do they miss, this is one of the aspects more often mentioned in the focus groups, along with the songs, as mentioned above, as shown by the following comments:

Closeness is something irreplaceable (Q7).

To be able to express love, affection in a personal and direct way (FG2-P17).

Direct contact with brothers, shaking hands (FG1-P1). Direct contact with brothers (FG2-P20). Human contact (FG3-P23). Human warmth (FG3-P32). Human warmth! To be able to hug brothers (FG3-P25).

Hugs. Kisses (FG1-P3). Kisses, kisses …, hugs … (FG3-P32). Hugs […] Contact (FG3-P30). Kisses and hugs (FG3-P34). Hugs (FG3-P28). Hugs and kisses (FG3-P24). For me, hugging brothers (FG4-P38). Hugging, laughing with them (FG4-P42). Convey affection with hugs and physical contact (FG4-P45). Greeting and hugging you, this is what I miss the most (FG4-P41).

Having personal conversations […]. And, well, hugs, strong hugs like this [embracing herself], I also need this. (FG2-P14)

Significant (#39) and personal (#40) conversations in videoconference interaction do not significantly perform as well as those in the Kingdom Hall. Some of the participants mention this feeling as follows:

You cannot ask personal questions, just about general things: How are you? How is work going? But if you want to talk about something more personal I feel it is different to the Hall. Because at the Kingdom Hall if you wanted to ask something to someone, you could take them apart and do it in private. Here is different (FG1-P10).

Maybe the conversations are less personal, because at the Kingdom Hall you could talk with a particular brother or couple and you could have more significant conversations, with a bit more intimacy. Of course, on Zoom […] the conversation level, in my opinion, is a bit more superficial. You don’t speak about personal issues because more people are listening (FG2-P17).

In face-to-face meetings, I can have more contact. I don’t know, I felt more comfortable talking privately. And, probably, I was talking during more time with a brother or a different one. Now, in my particular case, Zoom intimidates me. Since there are more people there, maybe it is just shyness … (FG2-P14).

I miss having meaningful conversations, sharing my feelings with someone. On Zoom we just talk about trivial issues (Q16).

Initially, many Witnesses left the meeting a few minutes after the programme was over because all congregants were in a large virtual room, as explained by one of the interviewees, who said:

There is a warm atmosphere but it is chaotic because there are several conversations at the same time […] You can perceive warmth. You can see that you really want to see them, but it is very confusing because, of course, 70 or 75 simultaneous conversations overlap and it is very difficult to understand anything (FG1-P7).

Some congregations have decided to use breakout rooms where smaller groups can interact, which has expanded the time that Witnesses interact after the meeting. Since in general the participants are randomly assigned to these rooms, some of the interviewees in congregations where this has been done, show their emotions when they say that:

Let’s see who I’m assigned with today! And this is very nice, very enjoyable (FG1-P8).

It is charming—since it is randomized, you don’t know who will be in your breakout room! And, it feels like when you are shopping in the street or in a mall and you unexpectedly find someone. This is a surprise, you do not know who you are going to be with tonight, and brothers really love it (FG1-P7).

In our congregation we have each week around fifty, from fifty to sixty, connections. Just two seconds after saying “amen” almost half of the connections used to disappear. They didn’t stay. But now, with the breakout rooms there are brothers who stay, and stay and stay … Sometimes there are still brothers connected two hours after the end of the meeting (FG4-P46).

There are some who also say that after the meetings those who stay longer are “even more than before, and for more time than before. Finally, the meeting must be finished, because otherwise it would last all day.” (FG2-P21). Thanks to this time to interact, some highlight that they have been able to “discover” brothers whom they almost did not know before (FG2-P15), or that

You discover amazing lives that you were not acquainted with because nobody would explain their funny stories, and now you find out that, well, there are some amazing people in the congregation. I believe we have won something in this regard. (FG3-P23).

5.6. Meetings in general

Table shows the results of meetings in general, which analyse the overall performance of some feelings that were asked before for a particular dimension, such as feeling close to God (#42), as well as new feelings and attitudes in an overall perspective.

Table 8. Meetings in general

Prerecorded meetings significantly perform more poorly in regard to feeling part of the meeting (#45) and brotherhood feelings (#46). The explanation has to do with the fact that interviewees did not personally know Witnesses that are recorded in the meetings that are broadcasted for the entire country. It seems then, that it was a good decision to substitute prerecorded meetings with videoconferences as a “good placebo” as an individual put it. Interestingly, when he was asked what he meant by that expression he replied..

I mean that I wouldn’t replace face-to-face meetings by this, I like to show physical affection. But since I cannot, for me this is perfect. I feel satisfied both emotionally and spiritually, I don’t think the educational level has decreased, it is just a different method (FG3-P23).

Other participants express it by saying: “I think that Zoom is like a patch, and a very good solution. But there is nothing comparable to in person meetings” (Q42) and, “it [Zoom] is better than nothing.” (Q9)

Other comments in this sense, some of them full of sentiment, are shown below with regard to prerecorded meetings:

For me the first week with prerecorded meetings was very hard […] you did not know anyone, I do not know. I really cried in the first week because I thought: ‘My God! I hope things are not going to be like this for the whole time’ And, when we started using Zoom, honestly, it is not the same as being face to face, but I love to see my congregation’s brothers presenting their assignments, which is a challenge, but you know them and you can talk to them for a while. It is not just watching a video with people you do not know, even though they are your brothers, but … (FG4-P42).

When I watch a meeting on streaming, I feel that I am not in my congregation. But when the meeting is locally held and broadcast, you know the brothers, because you used to speak with them before and after the meetings, I feel close to them and I really appreciate this feeling, if it is possible to do it by Zoom, instead of on streaming. When there is no other option, it is just fine. But, it makes me feel closer, at home, when meetings are held by Zoom (FG2-P17).

The information on streaming is fine. You take advantage of it, but it is different. It is like watching a movie. Honestly, I grasp the meaning, but there is something missing. Maybe it is because you do not see the participant brothers, I do not know, but it is colder. […] By Zoom it is more interactive. It is as if you were on the stage, so to say. This is my feeling. In a congregation meeting I feel as if I were on a stage, participating, like the actor of a movie, and with a meeting of streaming I feel I am just a spectator watching a movie (FG2-P22).

I can hardly identify myself with the participants (Q9).

I feel I am less participative (Q13).

I feel I am not part of the moment (Q37).

Two participants of the focus group mentioned: “I believe that Zoom is here to stay” (FG3-P32) and, “ … I hope so, we will find the way to combine both things [Zoom and in person meetings]” (FG2-P15).

6. Conclusions

This is the first paper that deals with the digitalisation process of Jehovah’s Witnesses during the COVID-19 pandemic, analysing its impact on their feelings, as well as the first religion paper that focuses only on this religious minority to use focus group methodology.

Five dimensions identified as key elements of their meetings were objects of this study: prayers, songs, speaking assignments, audience comments, and social interaction among congregants.

Jehovah’s Witnesses were prepared to quickly shift to online meetings, because their digitalisation process started years ago, with electronic publications, the jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) website, prerecorded meetings, as well as associated apps and software. This previous digitalisation process has both equipped their organisation with the needed technology and trained their members to develop digital skills that have proved to be crucial during the pandemic in order to meet virtually.

Digital meetings—both prerecorded and by means of videoconference—have not impacted in the relationship of Jehovah’s Witnesses with their God. All the feelings that have to do with their personal relationship with Jehovah, such as feeling close to the Lord (#1, #3, #42), feeling that they are praising God (#5, #9, #12 and #23) and feeling that they are taught by God (#20, #32) are correlated in the different kind of meetings. This is in line with (Catré et al., Citation2014) who conclude that Jehovah’s Witnesses have a strong faith and strong connection to a spiritual being.

Songs are one of the dimensions that performed significantly worse in the digital environment. It is very difficult to emulate the same degree of feelings (#6 and #10) when singing virtually at home—in the best-case scenario along with family, and in the worst case scenario completely alone—in comparison with doing it along with dozens of congregants. Likewise, the feeling of belonging (#7 and #11) to a group of worshippers when singing is clearly affected by meeting virtually. So as to stimulate the sense of belonging, it could be useful to play recorded songs with a chorus singing, which are available on jw.org (WTBTS, Citation2022) for some languages.

Digital interaction did not perform as well as in-person interaction. The scarce presence of significant (#39) and personal conversations (#40), as well as the absence of hugs and kisses in a digital environment, deeply affected the feelings of encouragement (#37). Nonetheless, the use of smaller breakout rooms, which can be considered a new virtual ritual, has been welcomed by Witnesses as a way to better emulate what is carried out in a Kingdom Hall.

Although digital meetings did not perform as well as in-person meetings, and in-person meetings were allowed to be carried out in Spain with some limitations in the number of attendants, the Governing Body of Jehovah’s Witnesses decided to continue an online-only arrangement as a way to show respect for the sanctity of life by means of not contributing to the pandemic expansion. Different Governing Body Update videos highlighted Bible principles involved when showing prudence due to the pandemic, such as placing a high value on life (Ecclesiastes 7:12, NWT), listening to the authorities (Romans 13:1,2, NWT) and not developing a casual attitude (Proverbs 22:3, NWT; WTBTS, Citation2020a). All things considered, the need for spiritual encouragement by means of in-person meetings has no suitable substitute. Nonetheless, the transcendent experience of uniting believers in a virtual environment is the option chosen by Jehovah’s Witnesses so as to mitigate the effects of not having meetings in Kingdom Halls.

Limitations of the research included that the sample was too small for the study to make segmentation. Future lines of research (Baker et al., Citation2020; Campbell & Evolvi, Citation2020) could analyse if different factors, such as age, gender or number of years after baptism as one of Jehovah’s Witnesses, influenced the feelings derived in digital meetings. In fact, the impact on the elderly could be especially significant given that digital illiteracy is common among this segment. Future papers will analyse how the digitalisation of Jehovah’s Witnesses meetings have impacted on their digital skills. To all intents and purposes, the improvement of digital competences among the older Witnesses can be considered a social value created by this religion, similar to their contribution to the fight against illiteracy in many countries (e.g., Spain) during the twentieth century. Additionally, a second limitation of the study was that no minor was included in the sample. Future research conducted with a larger sample could include minors to see how they are coping with the consequences of the pandemic. Furthermore, a third limitation of the analysis was that the study was carried out only in Spain. If the sample could be obtained at an international level, future papers could analyse how Jehovah’s Witnesses feelings differ depending on the country where they live, given that some cultures are more emotional than others. A fourth limitation is the scope of the analysis: only mid-week and weekend meetings were the object of the study. Future papers could also analyse how COVID-19 has affected the rest of the meetings that have not been considered in this paper, namely the Memorial of Jesus Christ’s Death, their large gatherings—called Assemblies and Conventions—as well as their public ministry that includes the field service meetings. A fifth limitation has to do with the fact that focus groups were conducted virtually due to COVID-19 restrictions. A sixth limitation deals with the fact that the analysis was carried out comparing the feelings derived from in-person meetings before the pandemic with online meetings during the pandemic. Given that hybrid meetings were allowed in most countries starting from 1 April 2022, future lines of research could analyse the difference between the feelings arising from in-person and online meetings in the hybrid era, thus controlling for recency bias. Finally, the proposed methodology could be applied in the study of other religious groups, in regard to the feelings derived from online interaction in comparison with in-person services.

Credit author statement

Jose Torres-Pruñonosa: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Miquel Angel Plaza-Navas: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing. Silas S. Brown: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was not required. Consent by participants was obtained by participants.

Public interest statement

The religion called Jehovah’s Witnesses is a community with over 8 million members around the world. They respect life, so they guard against COVID-19 more than the law says. They quickly changed their meetings to online. Even their elderly ones had to learn how to do it. We used a survey and focus groups. We looked at the feelings of Witnesses in Spain, checking how much their online meetings affected them compared to in-person meetings. They still felt close to God and learned things from the meetings, but online meetings were not so good when it came to singing songs and talking with others. Their example shows how feelings can be handled when religious people meet online.

Acknowledgments

We thank to the Office of Public Information of the Spanish Branch of Jehovah’s Witnesses, to Academia Group (Office of Public Information) of the World Headquarters of Jehovah’s Witnesses as well as the individuals interviewed for their cooperation.

We thank Jonatan Lajara López, Joan Sáez Fernández, Samuel Leyva Moreno, Noelia Gil Canalejo, Jose Luis Fuentes Verdes, Yerlin Karina Vásquez Mendoza, Diana Duque Limones, Jan Torres Barroso, Anabel Barroso Rodríguez, Abrahán Orante Gavidia, Paqui de la Cruz Ruiz, Emilia Belmonte Marginet, Rosa Plaza Belmonte, Marta Plaza Belmonte, Ferran Gómez Ribas, Naty Ortiz Clavería, Karen Ortiz Clavería, Paula Carceller Aguirre and Rosalía Gavidia Martínez for their technical support.

We thank Aníbal Iván Matos Cintrón and Daniel Martín Sánchez for their generous and invaluable assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jose Torres-Pruñonosa

Jose Torres-Pruñonosa is an associate professor at Universidad Internacional de la Rioja. His research is focused on social value, banking efficiency, corporate value, football economics and housing valuation. This research is related to the role of religions in regard to the creation of social value.