Abstract

The prevalence of COVID-19 in cities worldwide has impacted diverse groups of people, with the effects being debilitating on those living in slums, older persons, persons with disabilities and migrant workers. In this paper, we examine the effects of the pandemic on internal migrant workers in Accra, Ghana’s migration hotspot and measures implemented by the government to help them cope with the pandemic. Findings showed that COVID-19 have devastating impacts on internal migrant workers. Many have lost their livelihoods and were forced to return to places of origin. Besides, their poor living conditions put them at risk of contracting and spreading the virus. The government of Ghana’s response to the pandemic through lockdowns and travel restrictions failed to address teething challenges facing internal migrants–lack of accommodation, congested rooms, erratic incomes, limited access to health facilities–that the pandemic brought to light. On the basis of these findings, we recommend that the government, should commit more resources targeted at improving the economic, health and living conditions of internal migrants. In the short term, a dedicated financial support system for internal migrants is crucial to help ameliorate the impact of COVID-19 on them.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The COVID-19 pandemic has had debilitating impacts on societies across the globe. Although there is literature on the impact of the pandemic on migration, international migrants appear to have featured prominently in efforts to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic on vulnerable people. Very little attention has been given to internal migrant workers even though evidence shows that there are serious vulnerabilities associated with this category of people in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This article provides insights on the impact of the pandemic on internal migrant workers in Ghana’s capital city, Accra. Through examining their livelihoods, health and living conditions, the article draws attention to the plight of internal migrants and calls on government and relevant stakeholders to provide housing, health care facilities and other interventions that can sustain the well-being of internal migrants during and after COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The global impact of COVID-19 cannot be underestimated, as every sphere of human life has been affected by the onset and spread of the virus. The accompanying interventions, including restrictions in movements, lockdowns and border closures to curb the spread of the virus, present social and economic impacts that could be unprecedented in modern history. In Ghana, similar to other countries that experienced COVID-19, its effects were felt immediately and triggered a variety of responses including lockdowns, border closures, bans on social gatherings and religious activities, in an attempt to contain reported cases and prevent the virus from spreading further.

Nearly two years since it was declared a global pandemic, many countries are still struggling to cope with the devastating effects of COVID-19 on their economies. In the case of Ghana, key sectors of the economy including education, health, agriculture, tourism and hospitality, have been adversely impacted by COVID-19 (Ministry of Finance, Citation2020). With a projected reduction in the economic outlook for the country in 2020 from 5.8 percent to 1.5 percent (Ministry of Finance, Citation2020; World Bank, Citation2020), the ramifications on productivity and the general wellbeing of the population cannot be discounted. The shrinking economy could worsen poverty, increase unemployment, and increase health, energy and water expenditure (Brakman et al., Citation2020). Already, lockdowns and border closures introduced by the Government in March 2020 took a toll on education, health, tourism and general productivity.

Across the globe, the COVID-19 outbreak has affected vast segments of the population, with the poor and vulnerable groups impacted more severely (Ghosh et al., Citation2020 . According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA, Citation2020), the pandemic has severely impacted social groups in vulnerable situations, including people living in slums, older persons, persons with disabilities and migrant workers. Certainly, these people usually do not have adequate safety nets, generally have poor immunity and lack nutritious food, making them highly vulnerable (Ghosh et al., Citation2020; World Health Organisation, Citation2021). Considering that migrant workers tend to be concentrated in urban economic centres and are vulnerable to infections, there is a greater need to understand the dynamics of the virus on them. The impact of the virus on them becomes more severe in situations where they do not have decent housing, cannot access or pay for healthcare, or are engaged in risky jobs (Choudhari, Citation2020; Ghosh et al., Citation2020). Against this background, it is important to highlight the livelihoods, health and living conditions of internal migrant workers to understand how they navigate through the pandemic. The aim of this article is to examine the effects of the pandemic on internal migrant workers in Ghana’s capital city, Accra. The paper addresses a gap in the literature on migration and COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. A chunk of literature in this area have concentrated on challenges and problems of international migrants, focussing extensively on how the pandemic is impacting international migrants (see, e.g., Guadagno, Citation2020; International Labour Organisation, Citation2020a; Newland, Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2020; World Health Organisation, Citation2021), with little attention to how internal migrant workers navigate through lockdowns, food shortages or how they gain access to health and hygiene health facilities during the pandemic.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 gives an overview of internal migration in Ghana, while section 3 highlights critical challenges facing internal migrant workers during disease outbreaks. Section 4 presents the theoretical framework–Migrants’ Vulnerability Model–exploring factors that weave together to produce migrant vulnerabilities in urban locations. In section 5, we outline the methodology of the study. The results of the study are presented and discussed in Section 6. Finally, conclusions and recommendations of the study are outlined in section 7 and 8 respectively.

2. Internal migration, livelihoods and health of migrants in Ghana: A review

Internal migration is a common global phenomenon. Evidence shows that more people are engaged in internal migration than international migration. For instance, in 2018, there were 258 million international migrants and 763 million internal migrants (World Health Organisation, Citation2018). The situation in West Africa is not different from global trends as studies (e.g., Imoro, Citation2017; Tanle, Citation2010) have revealed high numbers of internal migrant workers in the sub-region.

However, given the dominance of international migration in the literature, it appears that internal migration has received little attention. The state of internal migrants in host communities, particularly in urban locations in times of COVID-19, deserves research attention, more so when the pandemic impacts all sections of society. The livelihoods of internal migrants in Ghana remain mostly informal, characterised by vulnerability and poor working conditions (Awumbila et al., Citation2014; Imoro, Citation2017). Access to necessities such as food, shelter, accommodation and security remains a significant challenge for this category of people (Awumbila et al., Citation2014; Imoro, Citation2017). More importantly, these challenges are woven into the livelihood activities of migrants, which implies that their ability to survive in host communities is dependent on livelihood strategies available to them (Awumbila et al., Citation2014; Imoro, Citation2017). The nature of work of migrants–hazardous occupations, unregulated work conditions, low wages, etc–puts a strain on their livelihoods and survival (Awumbila & Ardayfio-Shcandorf, Citation2008; Tanle, Citation2010).

Without a doubt, migration is associated with health risks. Institutional barriers to health such as discrimination and exclusion coupled with hash contexts of urban integration and unpleasant working and living environment present new health risks to internal migrants. Extant studies show that many internal migrants are excluded and marginalised in the provision of health care by national governments (Choudhari, Citation2020; Nyarko & Tahiru, Citation2018). Their situation is further heightened by their inability to access health care services promptly, absence of family support and social exclusion (Choudhari, Citation2020). For instance, in China, several internal migrants find it difficult to subscribe to health insurance services for reasons such as exclusion and high cost of insurance products, which results in poor health-seeking behaviours and unsatisfactory health outcomes (Mou et al., Citation2009). In India, Urudaya et al. (Citation2020) categorise migrant workers among vulnerable populations that face discrimination and maltreatment at the hands of health care personnel. In the case of Ghana, the literature highlights instances of exclusion and marginalisation as critical factors that create poor health outcomes and heighten the vulnerability of migrant workers residing in cities. In particular, female migrants experience difficulties when accessing health care due to marginalisation, exclusion, risk of being uninsured, poor health outcomes and vulnerability for the chunk of migrants in cities across the country (Nyarko & Tahiru, Citation2018). Despite the introduction of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), which proponents argued was intended to facilitate access to health care by Ghanaians, especially vulnerable groups, poverty, which is associated with unmet health needs, remains a critical barrier to internal migrants’ ability to register with the scheme (Lattof, Citation2018; Nyarko & Tahiru, Citation2018).

3. Challenges facing internal migrant workers in the wake of COVID-19

Arguably, one of the fastest media through which diseases spread is migration, defined in this study as the movement of people from one place to another over geographical space and distance. A number of studies have shown that migrants are critical elements in infection spread and containment of viral diseases such as COVID-19 (Ghosh et al., Citation2020; International Labour Organisation, Citation2020b; Ivakhnyuk, Citation2020; Moroz et al., Citation2020; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA, Citation2020). Given that migration is a common route for diseases to spread, it is imperative for health care professionals, policymakers and migration scholars to give attention to the challenges confronting migrant workers in the quest to understand the different dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic, curb its spread and mitigate its impacts on vulnerable populations. Particular interest is given to internal migrant workers because, as would be revealed in section 6, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed this category of workers in dire conditions, with many losing their mostly informal jobs and unable to access food and shelter. Indeed, the literature paints a bleak picture of desperate migrant workers during the first wave of the pandemic. For instance, Moroz et al. (Citation2020) acknowledge that lockdowns, travel restrictions and social distancing measures introduced to respond to the COVID-19 crisis have disproportionately affected migrant workers across the globe. As a result, many of them became stranded, and could not return either to their places of work or communities of origin. Without adequate access to housing, health, water, sanitation facilities, and other social safety nets, these migrants are bound to become more vulnerable to contagion in the third and subsequent waves of the pandemic.

In India, Bhagat et al. () give a gloomy account of how travel restrictions and lockdowns brought untold hardships to migrants and impending difficulties that confronted government agencies in managing the pandemic, such as inadequate PPEs and lack of isolation centres. In Russia, Ivakhnyuk (Citation2020) classified the challenges internal migrant workers faced during the pandemic into five themes: economic, medical, or sanitary-epidemiological, socio-psychological and political. Crucially, lockdowns and travel restrictions have impacted remittance transfers of internal migrants as they mostly send funds to families through informal channels such as transportation services. Disruption to public transport services such as train and bus services emanating from lockdowns has indirectly affected remittance flows. As pointed out by Egger and Sen (Citation2020), most internal remittances go to rural areas where there are limited banking and mobile network services. In places where migrants can switch to formal channels such as banks, mobile money platforms and e-wallets, limited access to ICT and banking facilities in destination regions have hampered such moves (Dipeolu, Citation2020).

India stands out as the country where the impact of COVID-19 has been felt most by internal migrant workers. With approximately 453.6million internal migrants working in major cities across India, lockdowns and restrictions imposed by state and local authorities exacerbated the already poor and inhumane living conditions of internal migrants (Ghosh et al., Citation2020). The shutdown of commercial activities and the announcement of lookdowns triggered panic among migrant workers. It led to an exodus of migrants from cities to predominantly rural areas, where many of them originate. Those who could not escape to their villages had to bear the brunt of living under a lockdown in decrepit housing conditions. Many faced food and health challenges, and social and psychological distress (Ghosh et al., Citation2020).

Still in India, Ritanjan and Kumar (Citation2020) provide detailed insights into the daily drudgery internal migrant workers went through amidst journeys to rural destinations on foot. The authors recount how migrants lost daily wages, ran out of food, defaulted in rents, and became stranded at bus and train stations. Similar studies reiterated the immediate challenges faced by migrant workers in India to include food, shelter, loss of wages, fear of getting infected and anxiety (Bhagat et al., ; Urudaya et al., Citation2020). In a study on the impacts of COVID-19 involving more than 3000 migrants from north-central India, Sahas (Citation2020) found that 42 percent of migrant populations were left with no ration, while one third were stuck at destination cities with no access to food, water and money. Given the dynamics of internal migration in urban locations, it is important to highlight the vulnerabilities associated with the phenomenon. In the next section, we present the Migrants’ Vulnerability Model to highlight factors that create vulnerabilities for migrant workers during a pandemic.

4. Theoretical framework: Determinants of migrants’ vulnerability

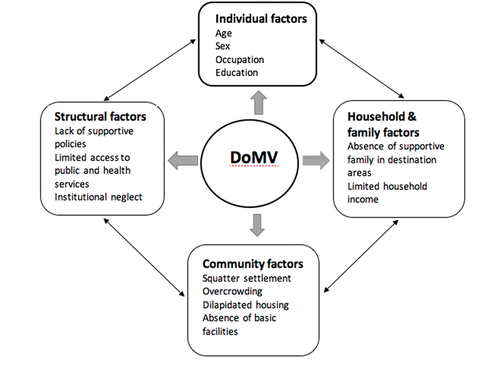

To reiterate, the purpose of this article is to highlight the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on internal migrant workers. Through the Migrants’ Vulnerability Model (Figure ), we offer a lens to examine vulnerabilities faced by migrant workers during the pandemic. Migrants, particularly internal migrant, workers are vulnerable in many situations (Oliver-Smith, Citation2010; Sahas, Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2020). For instance, migrants in destination areas are open abuse and exploitations (Yu et al., Citation2020). Events such as war, disease outbreaks and natural disasters tend to make them more vulnerable. Migrants’ Vulnerability Model is used to showcase the vulnerabilities of migrant workers during the COVID-19 outbreak. It also helps to explain their resilience and adaptive capacities. The model was designed by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) to explain the different forms of vulnerabilities confronting migrants. The model is a social-ecological model which acknowledges that individuals are situated within a household, a community and a country (International Organisation for Migration, Citation2019). As indicated in Figure , four broad factors–individual, household, community and structural—affect the vulnerability of migrants (International Organisation for Migration, Citation2019; Sahas, Citation2020).

Figure 1. Migrants’ vulnerability model.Source: International Organisation for Migration (Citation2019)

In the context of COVID-19, we argue that some factors–individual, household, community, and structural–weave together to produce migrant vulnerabilities, particularly in urban destinations. As pointed out earlier in Section 3, the outbreak of COVID-19 put migrant workers in cities and other urban locations in the world in vulnerable situations. At the individual level, factors such as migrants’ demographics (age, sex, level of education, etc), physical and biological characteristics, as well as their mental health and well-being exposes them to risk and vulnerabilities. Studies (e.g., Awumbila et al., Citation2014; Imoro, Citation2017; Tanle, Citation2010) show that in developing countries, most migrants fall within the 21–40 year age range and are mainly single or married. In addition, they are mostly uneducated and hail from rural areas where poverty and underdevelopment are common (Awumbila et al., Citation2014). Besides, migrants engage in risky behaviours, including smoking, violence and prostitution, and rarely seek health information and services from formal sources (Dzomba et al., Citation2019; Lu, Citation2010; Yu et al., Citation2020).

At the household level, migrants in urban enclaves manage families in destination and origin communities. Performing this dual-task puts pressure on them as they have to contend with other challenges like job insecurity and housing in destination areas. Families are essential in determining migrant vulnerabilities and adaptation. They are typically the first option for individuals who require support, particularly for children and youth. However, the absence of supportive social environments in the form of family and social support systems in cities can impact negatively on the health and well-being of internal migrant workers. Furthermore, the experience of being unfairly treated and lack of opportunities can compound the conditions of migrants (Yu et al., Citation2020), heighten insecurity and threaten their livelihoods.

Moreover, the environment in which migrants are located can deepen their vulnerabilities. For instance, most migrants reside in squatter settlements characterised by squalid conditions, overcrowding and absence of infrastructure and social services (Oppong et al., 2020). (Citation2020).In the context of Migrants’ Vulnerability Model, such environments present vulnerability to migrants. We argue that with the outbreak of COVID-19, this is highly likely to worsen for migrant workers living in slums and squatter settlements. Apart from individual, household, and community conditions that make migrants vulnerable and inhibit their adaptation capacity, the model also highlights structural conditions that impact the environment in which migrants reside. Migrants in vulnerable environments face structural barriers due to a lack of supportive policies and limited or no access to public services (Yu et al., Citation2020). For the most part, they are isolated from the economic, social, cultural and political benefits available to the broader society. Included in this barrier are institutional neglect and poor engagement of migrants by government agencies, which the International Organisation for Migration (Citation2019, p. 8) labelled “critical factors that perpetuate migrants’ vulnerability and adaptive capacities in destination areas”. Having provided perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic and associated vulnerabilities the disease can pose on migrant populations, we turn attention to Ghana, the case study location, to explore these issues in detail.

5. Materials and methods

5.1. Study design

The methodology draws from the philosophical stance of interpretivism. Within the qualitative research tradition, an interpretive approach has been recognised for being flexible, even though the context in which it is applied is systematic, rigorous and precise (Creswell, Citation2012). The focus of the researcher is on understanding the meanings and interpretations of “social actors” (Denzin, Citation2017), in this case, internal migrant workers, from their point of view. This philosophical standpoint of the interpretivist school fits well with the aim of this research: to examine the COVID-19 pandemic in Ghana from the perspective of internal migrant workers. Thus, the design adopted a rigorous and systematic process to generate data from respondents, relying on authentic sources and explicit procedures. It also helped to gain detailed insights into their adaptation strategies and the government’s response to the pandemic.

5.2. Data and sources

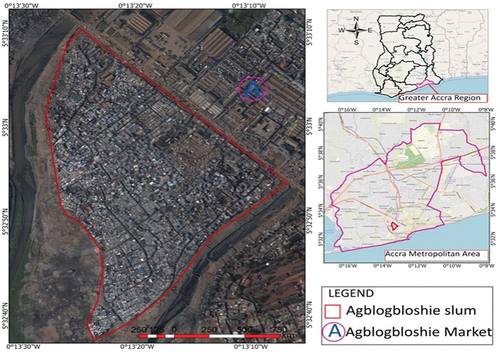

Through analysis of first-hand accounts by migrants, supplemented with secondary data, this study provides a rather sombre account of the impact of COVID-19 on internal migrants living in Accra, Ghana’s most populous city (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2017). We collected primary data in Agbogbloshie (Figure ), a popular migrant settlement in Accra and a hotspot for migration in Ghana. Primary data collected through interviews was augmented with content analysis of media reports and official government communications. This helped to enrich the data and provided detailed insights into the study.

Figure 2. Map of agbogbloshie slum in Accra, Ghana.Source: Cartography Unit, Department of Geography and Regional Planning, UCC (2022)

As of late 2015, the area hosted 9,684 migrant population in Accra alone (Accra Metropolitan Assembly, 2015). These migrants originate mainly from the northern part of Ghana and neighbouring countries in the West Africa sub-region, including Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso. Migrants in the area constituted themselves into informal groups in the form of trade-related associations–yam traders, onion dealers, scrap metal dealers and e-waste dealers–based on the dominant economic activities in the city that they offered their services.Footnote1

5.3. Selection, inclusion and exclusion

The researchers relied on a network of migrant associations in the study area to reach out to respondents for interviews. Following initial phone conversations with leaders of these groups to discuss the research, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and assurances of confidentiality, a list of potential respondents was compiled. To be included in interviews, respondents had to meet the following criteria: be considered an internal migrant (i.e, a Ghanaian); live in the Agbogbloshie migrant enclave for two or more years (since some are itinerant migrants) and; belong to an informal group where members seek daily wage-based labour activity. Given that the study focused exclusively on internal migrant workers, international migrants who resided in the study area were exempted. Besides, Ghanaian migrants who lived outside the study area were excluded.

5.4. Data collection and analysis

As indicated in Section 5.2, two sets of data were collected for the study. The first involved primary data collected through interviews with participants and observations of the study area. The second consisted of secondary data obtained from policy documents, official communication, newspaper and media reports on how the government of Ghana responded to the pandemic.

Primary data collection involved phone interviews with selected individual migrants as COVID-19 restrictions did not allow for face-to-face interviews. A sample of 25 internal migrants were interviewed. The sample size is relatively small, given that Accra is one of the migration hotspots in Ghana. However, the lockdown and other restrictions introduced by the government created disorder and uncertainties among migrant populations and affected the sample size. Some declined interviews following initial arrangements and consent has been secured. Many were navigating through “unexpected” challenges posed by the pandemic. Others were attempting to return to their places of origin as the pandemic seemed to have dislodged them from various livelihood activities that generated some income. These challenges notwithstanding, the interviews that were conducted elicited detailed information that touched on the critical issues covered in the paper.

An in-depth interview guide was designed to facilitate the interview process. The guide consisted of close and open-ended questions that sought information on participants’ demographics, key livelihood activities, views on COVID-19 and how it impacted their well-being and working conditions. Additionally, the questions sought their views on adaptation strategies and how the government of Ghana responded to the pandemic. Interview duration ranged from 30 minutes to one hour. Interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed into Microsoft word document format and developed into themes for analysis.

For secondary data, we focused primarily on media reports and official government policy documents relating to the pandemic and how these sought to address the needs of internal migrant workers. Content analysis was conducted on policy documents, newspapers and media reports. Four documents and 16 newspaper and 12 media reports were analysed. Various types of information, including strategies adopted by internal migrant workers to contain the pandemic and COVID-19 intervention programmes implemented by the government, were extracted and used to highlight a broader response to the pandemic and its implications on internal migrant workers in Accra.

6. Results and discussion

From a global perspective, it appears COVID-19 is urban-centric as cities with larger populations are the worst affected by the disease (Ghosh et al., Citation2020; World Bank, Citation2020). Given that in developing countries, a chunk of the slum population is found in cities (Ghosh et al., Citation2020), the threat of COVID-19 on slum dwellers and vulnerable groups such as migrants could be severe. In the case of Ghana, a set of measures rolled out by government institutions to contain the disease included the closure of the country’s borders, lockdown of major cities and a ban on social and religious activities. Despite the effectiveness of these measures in helping to curb the spread of the disease, they brought untold hardships to vulnerable groups. In the sub-sections that follow, we present results on the effects of the pandemic on internal migrants in three thematic areas: livelihoods, living conditions, and health and well-being.

6.1. COVID-19 and livelihoods of migrants

In Ghana, migrants’ livelihoods are centred around informal economic activities that require little or no skills to pursue (Osei-Boateng & Ampratwum, Citation2011). Many of them reside in slum settlements and urban enclaves called zongos.Footnote2 Others “create” squatter settlements where they live together in groups and undertake livelihood activities that centre primarily on informal economic activities (Imoro, Citation2017). Their daily lives revolve around their ability to hustle through market enclaves and offer labour-power for a wage. They work as bar attendants, hawkers, scrap metal dealers and sellers of consumable and non-consumable goods. For internal migrants seeking “greener pastures” in Accra, the most popular livelihood activities are head porterage–popularly called kayayeiFootnote3 for females–and truck pushing dominated by males (Adaawen & Owusu, Citation2013; Imoro, Citation2017). Nevertheless, with Accra under a lockdown following the government’s announcement of policies to curb COVID-19, major economic activities in the city came to a halt. All markets and major shops were closed. Migrant workers who offered their services in these markets were suddenly “out of work”. One migrant gives an account of how the lockdown impacted his livelihood and income:

Business was going on normal before the virus was reported in Ghana and since then business have been very very low. Because people no longer come to the market to buy things. I help my madam to sell yam. You know this is a perishable commodity and since the lockdown, the markets were ordered to close and now I am home doing nothing … no job. It is hard (personal communication, 23-year-old male migrant, 25 June 2020).

The restrictions imposed by the government impacted hugely on the livelihoods of migrants in terms of loss of jobs and income. The findings in this study confirm the assertion by Bhagat et al. () that migrants in destination areas may have their livelihoods terminated due to the pandemic. Some of the migrants interviewed expressed fear and anxiety regarding how their quest to earn a living has exposed them to the virus. Others voiced discomfort over the use of PPEs like nose masks and face shields. For instance, some head-porters and truck-pushers complained of difficulty breathing when wearing masks and carrying loads or pushing a truck. Besides, the precarious nature of their work and the environment in which they live–congested dwellings with no sanitation facilities and limited space for social distancing–affected their ability to adhere to measures recommended by health authorities to prevent the spread of COVID-19 such as the use of hand sanitizers and washing of hands with soap under running water. For many migrants in the study area, using hand sanitizers and soap is a rare privilege as shown in the following narrative:

I am a scrap metal dealer. We scavenge for metals and sell them for the manufacture of goods. We are told to wash our hands with soap and use hand sanitisers. But the nature of my work, it is not possible to do that. I dig through dumpsites with my bare hands and you can imagine how my hands look like. My work is ‘dirty work’ and cannot wash my hands frequently. We fear to get the virus but there is nothing we can do (personal communication, 27 year-old male migrant, 20 June 2020).

Internal migrants in Ghana, similar to those in China and India (see, e.g., Bhagat et al., ; Ghosh et al., Citation2020; Sahas, Citation2020), became vulnerable as they were exposed to the virus. Many could not procure PPEs such as hand sanitizers and nose masks to prevent possible infection and transmission of the virus. This is against the backdrop that PPEs supplied by the government to people residing in Accra came at the latter pattern of the lockdown. Prior to this, residents in the city had to procure their own PPEs to prevent them from getting the virus. Those who could not buy their PPEs waited until government-supplied PPEs were made available. For migrants whose source of income was erratic, procuring PPEs was a key challenge, especially when they could not engage in income-generating activities because of the lockdown.

It emerged from interactions with respondents that the lockdown pushed many internal migrants in the city to the brinks. With little or no safety nets to turn to and transportation services terminated, some were forced to return to their communities of origin using risky and unapproved routes. In one instance, about 40 migrants, including pregnant women and children, embarked on a perilous journey 660 km from Accra to Walewale, a town in the North East Region of the country. Two cargo trucks carrying these migrants were intercepted by police officers along the way.Footnote4 They were handed over to social protection officers for support and later returned to the slums where they lived in Accra. However, with very little social support services available to these vulnerable groups, their ability to cope with harsh conditions in the city is questionable. It was revealed from interviews that some migrants in the city moved back to their places of origin shortly after the lockdown was lifted,Footnote5 a situation they attributed to the difficult conditions posed by the lockdown and other restrictions such as the use of PPEs and social distancing requirements announced by the government. An interview with a migrant confirmed this development:

When they said we can now go out, some of my friends decided to go back home [source region]. … no jobs to do, our money is finished and there is no food. So, it is better to go back and be with your family and friends. At least they can get food to eat at home (personal communication, 30 year old female migrant,14 July 2020).

With no jobs, little money and dwindling food supplies, moving back to source regions was deemed a suitable alternative for some migrants. However, this form of reverse migration has implications on poverty and dependency burden in source regions. For instance, Dreze (Citation2020) argues that reverse migration emanating from the pandemic could affect the poorest states or cities in developing countries through a disproportionate labour pool that can affect employment prospects in such states. In the absence of social security or pension schemes for internal migrants in Ghana, there is no guarantee of employment or money for these return migrants, many of whom hail (Citation2020). from rural areas in the northern part of the country where poverty is endemic. The findings show that the COVID 19 pandemic took the livelihoods of internal migrants hostage. However, not only their means of earning a living was under siege. As will be shown in section 6.2, the virus affected the conditions in which migrants in the city lived.

6.2. COVID-19 and living conditions of migrants

Typical of slums, most of the dwellings in Accra occupied by migrants can be described as urban slums dominated by wooden structures with small spaces and little ventilation and routes for movement (Afenah, Citation2010; Imoro, Citation2017). These structures are prone to fire outbreaks as they are made mainly of wood and cardboard paper. The rooms are congested with an unusually high number of occupants and personal belongings. It is common to find as many as ten or more people sleeping in one wooden structure with a small space ideal for two people (Imoro, Citation2017). The threat of COVID-19 infection is very high under such circumstances. A migrant worker described her living condition in a telephone interview:

For accommodation we have rented it as a group, we are five in number and it is a single room. It is a wooden structure and all the five of us sleep in it. We pay weekly so when the weekends, we all contribute and pay. We pay 40 Ghana cedis [equivalent to US$ 4.26]. The room is very small so we are congested inside. You cannot sleep comfortably … we just manage ourselves inside (personal communication, 29 year old female migrant, 3 July 2020).

As observed by Imoro (Citation2017), internal migrant workers in Accra live in poor conditions. This makes them vulnerable to disease infections. Apart from being exposed to COVID-19, poor living arrangements expose migrants to respiratory and skin diseases, particularly when they sleep together in crowded rooms with little ventilation, as was the case in the slums where this study was conducted. Their situation is compounded by their use of common sanitation facilities such as public toilets and bathrooms with little or no adherence to safety protocols outlined by WHO to help fight COVID-19. In this way, the pandemic brought an additional burden to existing health risks facing migrants, similar to developments in India, where migrants living in slums faced serious health risks and deprivation during the lockdown (Ghosh et al., Citation2020). Considering that internal migrant workers mingle with a wider population through their daily hustle and bustle, much of which occurs in busy markets and crowded streets, the risk of contracting and transmitting the COVID-19 virus can be high, particularly before the lockdown was announced. However, as would be shown in section 6.4, government officials and local authorities did not pay adequate attention to internal migrant workers in rolling out measures to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Crucially, excluding this section of the population who require special attention in times of a pandemic of such a huge magnitude points to laxity on the part of state authorities to extend interventions to vulnerable sections of the society.

6.3. COVID-19 and migrants’ health

Findings show that COVID-19 has exacerbated the already precarious nature of the health-seeking behaviour of migrants. As outlined in the Migrants’ Vulnerability model that underpins this study (section 4), migrants hardly seek health information and services from certified sources. Instead, they would typically resort to self-treatment first before going to clinics or hospitals to seek further medical attention (Nyarko & Tahiru, Citation2018). This assertion was the case with migrants in the study area, as shown in the following account by a migrant worker:

The health facilities here are limited. I can say very few if you want to buy some essential drugs you have to go to Circle or other far places. Also, because we sleep in groups too it is easy to fall sick because during sleep, others cough and others sweat and we are more than ten in the room. This exposes us to ill health and you don’t know when you will catch Covid-19 (personal communication, 34 year old female migrant, 8 July 2020).

Since its outbreak, one of the ways of detecting whether the virus infects a person is by visiting designated health facilities to undertake a COVID-19 test, especially when a person shows symptoms of having the virus. But with few or no health facilities in slums, getting access to clinics or hospitals to undertake confirmation tests constituted a significant challenge for migrants. The absence of clinics further pushed some to engage in self-treatment. However, by engaging in self-treatment and adopting unorthodox routes to manage their medical conditions, it is difficult for internal migrants to know their COVID-19 status. They can easily get infected and possibly transmit the virus to their roommates and the general public inadvertently. Besides, such behaviours posed severe risks to initiatives put in place by the government to prevent the virus from spreading further.

Moreover, with their economic conditions usually characterised by poverty and deprivation, it becomes difficult for migrants to give adequate attention to their health needs in a pandemic situation (Ungruhe, Citation2020). Therefore, for migrants with underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases, the risk of contracting COVID-19 is even higher. In Ghana, evidence shows that most migrant workers have not enrolled on the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS; Sabutey, Citation2014). Among those who have signed onto the NHIS, a significant proportion do not renew their cards a year after expiration (Lattof, Citation2018). Some resort to self-medication by using herbal treatment or purchasing drugs from unlicensed facilities, as highlighted in the following interview:

Mostly, with my health issues, I have some of my friends here who sell drugs so anytime I do not feel well I explain my situation to any one of them and they give me drugs. Now in this Covid-19 situation we find it difficulty to go to the hospital because of fear. And for me, I don’t have the health insurance card, so I only contact some of my friends who sell the drugs and buy from them (personal communication, 27 year old male migrant, 27 June 2020).

Certainly, the health conditions of migrants living in slum dwellings make them susceptible to COVID-19 infection. The health situation of internal migrants in Accra is worsened by congested settlements and workplaces, limited public toilet facilities and casual jobs. The issues outlined here, coupled with difficult financial circumstances resulting from lockdowns and other restrictions, present severe challenges to internal migrants in terms of a surge in vulnerability and reduced adaptation mechanisms. Against this background, policies designed to manage risks associated with the pandemic should pay particular attention to the needs of vulnerable groups like internal migrants. The next section throws light on the government of Ghana’s response to the pandemic and whether the policies implemented addressed the needs of internal migrants.

6.4. Government’s response and implications for internal migration in Ghana

Migrants’ living conditions, health-seeking behaviour and livelihood activities make their survival precarious and unsustainable, particularly during periods of crisis. Given the high risk of vulnerable groups, including migrant workers, to the COVID-19 pandemic as demonstrated in the extant literature, it is imperative that policies designed to contain the disease and address its spillover effects, consider the peculiar needs of internal migrants. Following the detection of COVID-19 virus in Ghana, the government rolled out several measures to as it were, curb its spread and mitigate its impacts on the population. The interventions ranged from self-isolation, quarantine, social distancing, and treatment of infected persons to border closures, partial lockdowns, provision of PPEs and distribution of relief packages to sections of society. In one of his biweekly addresses to the nation on measures designed to curb the spread of the virus, the President of Ghana launched the COVID-19 Alleviation Programme, with support from the World Bank which, among other things, sought to provide relief and essential supplies to people living in areas that had been locked down (World Bank, Citation2020). He explained how through the programme, state institutions were collaborating with local authorities to help residents in areas under lockdown in the following statement

Through this Programme, the Ministries of Gender, Children and Social Protection and Local Government and Rural Development, and the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO), working with MMDCEs and the faith-based organisations, have begun to provide food for up to 400,000 individuals and homes in the affected areas of the restrictions. It will come in the form of dry food packages and hot meals, and will be delivered to vulnerable communities in Accra, Tema, Kumasi and Kasoa (Bi-weekly update on COVID-19, President Akufo-Addo, 5 April 2020).

Even though the government’s COVID-19 response policies did not target migrant workers directly, some of the interventions announced by the President and other sporadic relief packages provided by NGOs, corporate organisations and private individuals brought some respite to vulnerable groups, including internal migrant workers who were impacted heavily by lockdown and border closures. The Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection,Footnote6 the government’s principal agency responsible for developing and implementing social protection policies, provided temporal shelter and food to vulnerable populations, including some internal migrants living in Accra during the lockdown. The sector Minister indicated that:

Some 15,000 ‘Kayayei’ (mostly migrants from Northern Ghana) and needy persons are being fed by the Ministry daily during the lockdown period. In addition, a makeshift shelter has been provided for some of them as well. We provide one hot meal a day as a government.Footnote7

Although these interventions brought some respite to vulnerable groups, including internal migrants, it is important to note that such initiatives hardly achieve lasting impacts as they are temporarily, sporadic and ad hoc. Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted negatively on vulnerable groups in Accra. The means through which migrant workers earn a living was “locked up” following the government’s “lockdown” of the city. Some of the respondents were of the view that the government’s social interventions in the form of one hot meal per day and blankets were very superficial. They felt state agencies failed to address the teething challenges facing migrants–lack of accommodation, congested rooms, erratic incomes, limited access to health facilities–that the pandemic brought to light. One of the leaders of the migrants in the study area lamented the inadequacy of support systems for internal migrant workers as follows:

Our problem is not water and blankets and hot food. We want accommodation, clinic so we can go and check ourselves, and cash support from the government. We are being ejected from here because we can’t get money to pay the rent. No jobs because of COVID. So why can’t the government get a temporal place for us to move there and sleep. If the COVID is over, we can come back and do our work (personal communication, 30 year old female and Leader of migrants, 24 June 2020).

Targeting migrants for support in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic requires adequate planning, mobilisation of resources and clearly laid out implementation procedures. However, this appears to have escaped state agencies and local authorities responsible for implementing the government’s COVID-19 response programmes. For instance, relief packages (e.g., hot food, warm blankets, biscuits and bottled water) were distributed haphazardly without proper coordination. While migrants were already in despair from COVID-19 induced economic, social and health challenges, the distribution of relief items exacerbated their situation as some had to join long winding queues and wait for many hours to receive relief items. The following account by a migrant worker paints a picture of the chaos associated with the distribution of items:

I heard of the it [distribution of supplies] through a phone call from my friend. I got there, I saw a very long line but said I will join, … maybe I will get something for my children. I waited in the line for three hours. But when it was getting to our turn, they said the things are finishing. I got just one pack of biscuits after spending my whole day at the place (personal communication, 28 year female migrant, 4 July 2020).

Another respondent expressed dissatisfaction with the distribution of supplies as follows:

They brought us water. That is not my problem. I want a place to sleep, food to eat and money in my pocket. No work so no money. Even the place was congested with many people. They pushed us and I fell down. I fear we can get more COVID from there so I left (personal communication, 24 year old female migrant, 20 June 2020).

People moved to distribution centres in droves following radio and TV announcements that outlined plans to provide support to vulnerable groups living in Accra. However, with no crowd control measures in place to facilitate easy distribution of items, there was little regard for health and safety protocols such as social distancing and the use of hand sanitisers and face masks. This potentially exposed the people to further risk of contacting the COVID-19 virus.

As of the time of writing, no specific interventions have been designed by the government to assist migrants or other venerable groups that were adversely impacted by the pandemic. The COVID-19 Alleviation Programme did not specifically target migrants and therefore, could not alleviate their plights substantially. Comparatively, the situation in Ghana is different from other countries where governments and health officials implemented specific interventions for migrants and slum dwellers during the pandemic. For instance, In India, the Civic Body of Mumbai set up camps to isolate migrant squatters living in the Dharavi slum (The New Indian Express, Citation2020). Similarly, local authorities in Brazil and Columbia implemented a subsidised rental housing programme or temporary settlement at government-managed facilities for the most vulnerable people, including migrant workers (KPMG, Citation2020). No such measures were implemented for internal migrant workers in Accra as the study’s findings show.

7. Conclusion

It is concluded that, the vulnerability of internal migrant workers living in Accra heightened in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Broadly, policies and programmes implemented by the government of Ghana to mitigate the impacts of the pandemic on the population failed to capture the peculiar circumstances of internal migrants. While government interventions covered some vulnerable groups including internal migrants albeit without properly laid down procedures, no specific measures targeting the living, health and economic conditions of internal migrants was designed and rolled out to help them cope with the effects of the pandemic.

8. Recommendations

Given their level of vulnerability, internal migrants require a multi-dimensional social support system that is long term and capable of sustaining them even after the virus has been defeated. A dedicated financial support system for internal migrants is crucial to help ameliorate the impacts of COVID-19. This could take the form of cash transfers and health insurance to help vulnerable migrants meet basic needs such as food supplies, water and greater access to health care. Improving the living conditions of migrants in the Agbogbloshie migrant enclave through resettlement schemes would also guarantee a more decent livelihood for migrant workers. The government should commit more resources on this front and, in partnership with NGOs, civil society groups and migrant associations, provide housing, health care facilities and other interventions that can sustain the well-being of internal migrants during and after COVID-19. Given that Ghana is experiencing the third wave of the virus (the omicron variant), which experts warn could be more contagious, securing the well-being of vulnerable groups including internal migrants, is critical in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Declaration by Authors

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest and that all contributed equally in the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Suleman Dauda

Suleman Dauda is a Lecturer at the Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Cape Coast, Ghana, with a PhD from the University of Surrey, UK. His research focuses on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Ethics in the Extractive Industries. His research interest covers a range of issues including Sustainable Livelihoods, Extractive Industries, Development Geography and Business Ethics. His affiliation with University of Cape Coast and University of Surrey has deepened his research and teaching experience in these research areas.

Razak Jaha Imoro

Razak Jaha Imoro is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Cape Coast. He holds a Ph.D. in Development Studies from the Institute of Development Studies, University of Cape Coast, Ghana. His research interests include migration, conflict, development, social policy, social protection and peace studies. Dr. Jaha has carried out some consultancies for both local and international organizations including National Peace Council of Ghana and Inter-Governmental Action Group Against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA).

Notes

1. These groups are informal and do not signify that migrants were doing business as onion dealers or yam sellers. Rather, they are used to show where migrants offered their services such as carrying onion or yams through head porterage or assisting with sales and transportation of goods such as onion or yams.

2. The word “Zongo” comes from the Hausa “zango”, which means ‘temporary settlement (Casentini, 2018). Citation2018These places are viewed as informal settlements mostly found in urban centers inhabited by “strangers” who are often identified with Islam.

3. “Kaya business” refers to the act of carrying loads on the head for a fee and the women who are engaged in this activity are called “Kayayei” (Yeboah, et al, 2014(Citation2014)).

4. Monday, 30 March 2020 Myjoyonline.com report: https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/national/cargo-drivers-smuggling-head-porters-to-the-north-forced-to-turn-back/ (Accessed: 2 October 2020).

5. The President announced the lifting of the lockdown on Sunday, 19 April 2020 to allow for non-essential businesses to operate. The wearing of nose masks and other COVID 19 protocols remained in place.

6. The Ministry is responsible for policy formulation, coordination and monitoring and evaluation of Gender, Children and Social Protection issues within the context of the national development agenda. https://www.mogcsp.gov.gh/about/ (Accessed 21 January 2021).

7. Wednesday, 1 April 2020; Graphic Online report https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/gender-ministry-to-feed-15-000-kayayei-twice-daily.html (Accessed 25 October 2020).

References

- Adaawen, S. A., & Owusu, B. (2013). North-South migration and remittances in Ghana. African Review of Economics and Finance, 5(1), 1–16. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC148194

- Afenah, A. (2010). Re-claiming citizenship rights in Accra: Community mobilization against the illegal forced eviction of residents in the old fadama settlement. Habitat International Coalition. Accessed 27 July 2021.

- Awumbila, M., & Ardayfio-Shcandorf, E. (2008). Gendered poverty, migration and livelihood strategies of female porters in Accra, Ghana. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 62(3), 171–179. http//:migratingoutofpoverty.org

- Awumbila, M., Owusu, G., & Teye, G. K. (2014). Can rural-urban migration into slums reduce poverty? Evidence from Ghana. Migrating Out of Poverty Working Paper 13. UK: University of Sussex.

- Bhagat, R. B., Reshmi, R. S., Sahoo, H., Roy, A. K., & Govil, D. (2020). The COVID-19, migration and livelihood in India: Challenges and policy Issues. Migration Letters, 17(5), 705–718 . https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v17i5.1048

- Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & van Witteloostuijn, A. The turn from just-in-time to just- in-case globalization in and after times of COVID-19: An essay on the risk re-appraisal of borders and buffers. (2020). Social Science and Humanities Open, 2(1), 100034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100034

- Casentini , G. (2018). Migration networks and narratives in Ghana: a case study from the zongo Africa 3(88), 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972018000177

- Choudhari, R. (2020). COVID 19 pandemic: Mental health challenges of internal migrant workers of India. Asia Journal of Psychiatry, 54 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102254

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson Education.

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). Critical qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416681864

- Dipeolu, A. (2020). Beyond remittances: Covid-19 and the ‘future’ of African Diaspora –homeland relations. African Leadership Centre Op-Ed Series. King's College, London‘ (Accessed 24 September, 2020). https://www.africanleadershipcentre.org/attachments/article/644/Oped%20Vol.3%20Issue%203.pdf

- Dreze, J. (2020). Averting hunger during monsoon calls for bold security measures. The Indian Express. Accessed 20 May (2020).

- Dzomba, A., Tomita, A., Govender, K., & Tanser, F. (2019). Effects of migration on risky sexual behaviour and HIV acquisition in South Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 2000-2017. AIDS Behaviour, 23(6), 1396–1430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2367-z PMID: 30547333

- Egger, E. M., & Sen, K. (2020). Migrant workers in the Covid-19 pandemic. United Nations University-World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNI-WIDER)(Accessed 27 June 2021). https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/migrant-workers-covid-19-pandemic

- Ghana Statistical Service (2017). Ghana living standards survey (GLSS 7) report.

- Ghosh, S., Seth, P., & Tiwary, H. How does Covid-19 aggravate the multidimensional vulnerability of slums in India? A commentary. (2020). Social Science and Humanities Open, 2(1), 100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100068

- Guadagno, L. (2020). Migrants and the Covid-19 pandemic: An initial analysis. Migration Research Series No. 60 International Organization for Migration. Geneva, International Organization for Migration. publications.iom.int

- Imoro, R. J. (2017). North-South migration and problems of migrant traders in Agbogbloshie. African Human Mobility Review, 3(3), 1073. https://doi.org/10.14426/ahmr.v3i3.838

- International Labour Organisation (2020a). Protecting migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recommendations for policy-makers and constituents. April Policy Brief. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labourmigration/publications./WCMS_743268/lang–en/index.htm

- International Labour Organisation. (2020b). COVID-19: Impact on migrant workers and country response in Thailand. International Labour Organization Country Office for Thailand, Cambodia and Lao PDR. 17 April 2020

- International Organisation for Migration (2019). IOM Handbook on Protection and Assistance to Migrants Vulnerable to Violence, Exploitation and Abuse. Accessed 12 December 2020. https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/DMM/MPA/1-part1-thedomv.pdf

- Ivakhnyuk, I. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic challenges migrants worldwide and in Russia. Population and Economics, 4(2), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.3897/popecon.4.e53201

- KPMG. (2020). Government response–global landscape. Accessed 12 November 2020. https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2020/04/government-response-global-landscape.html

- Lattof, S. R. (2018). Health insurance and care-seeking behaviours of female migrants in Accra, Ghana. Health Policy and Planning, 33(4), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy012

- Lu, Y. (2010). Mental health and risk behaviours of rural–urban migrants: Longitudinal evidence from Indonesia. Population Studies, 64(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324721003734100.

- Ministry of Finance. (2020). Statement to parliament on the economic impact of covid-19 pandemic on the economy of Ghana. Accessed 24 March 2021 1-22 .

- Moroz, H., Shrestha, M., & Testaverde, M. (2020). Potential Responses to the COVID-19 Outbreak in Support of Migrant Workers. World Bank Group “Living Paper” Version 10. World Bank.Accessed 23 July, 2021. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11866

- Mou, J., Cheng, J., Zhang, D., Jiang, H., Lin, L., & Griffiths, S. M. (2009). Health care utilisation amongst Shenzhen migrant workers: Does being insured make a difference? BMC Health Service Research, 9(1), 214. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-214

- The New Indian Express. (2020). Mumbai civic body mulling ’Kerala model’ to contain coronavirus in Dharavi. Accessed 29 October 2021. https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/

- Newland, K. (2020). Will International Migration Governance Survive the COVID-19 Pandemic? Migration Policy Institute. Accessed: 25 October, 2020. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/globalcompact-migration-governance-pandemic-final.pdf

- Nyarko, S. H., & Tahiru, A. M. (2018). Harsh working conditions and poor eating habits: Health-related concerns of female head porters (kayayei) in the Mallam Atta Market, Accra. BioMed Research International, 2018, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6201837

- Oliver-Smith, A. (2010). Nature, Society, and Population Displacement: Toward an Understanding of Environmental Migration and Social Vulnerability. Interdisciplinary security connections’ publication series of UNU-EHS No. 8/2009. Accessed: http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:1862/pdf5130.pdf

- Oppong , E.F., Asomani-Boateng , R.& Fricano, R. J. (2020). Accra's Old Fadama/Agbogbloshie settlement. To what extent is this slum sustaniable? African Geographical Review 39 4 289–307 https://doi.org/10.1080/19376812.2020.1720753

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2020). What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants and their children? OECD policy responses to coronavirus (COVID-19). Accessed 25 October, 2020. http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/what-is-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-immigrants-and-their-children-e7cbb7de/

- Osei-Boateng, C., & Ampratwum, E. (2011). The informal sector in Ghana. Friedrich- Ebert-Stiftung. Accessed 3 July, 2021. http://www.fesghana.org/index.php?page=informal-economy

- Ritanjan, D., & Kumar, N. (2020). Chronic crisis: migrant workers and India’s COVID-19 lockdown. London school of economics and political science.Accessed 27 June, 2021. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2020/04/08/chronic-crisis-migrant-workers-and-indias-covid-19-lockdown/

- Sabutey, V. S. (2014). Celebrating International Women’s Day: A Look at the Plights of Ghanaian Female Porters (Kayayei). Multimedial Group, Ghana. https://www.myjoyonline.com/opinion/2014/March-11th/celebrating-international-womens-day-a-look-at-theplights-of-ghanaian-female-porters-kayayei.php

- Sahas, J. (2020). Social conditions of migrant construction workers. TML Weekly Information Project, 50(11), 12–22 . jansahas.org

- Tanle, A. (2010). Livelihood status of migrants from northern savannah zone resident in the Obuasi and Techiman Municipalities, Ghana. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Cape Coast

- Ungruhe, C. (2020) A lesson in composure: Learning from migrants in times of covid-19. UCL Medical Anthropology. Accessed 14 August 2021 Erasmus University of Rottadam https://medanthucl.com/2020/05/07/a-lesson-in-composure-learning-from-migrants-in-times-of-covid-19/. https://medanthucl.com/2020/05/07/a-lesson-in-composure-learning-from-migrants-in-times-of-covid-19/

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA, 2020). Everyone Included: Social Impact of COVID-19. Accessed 27 June 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/everyone-included-covid-19.html

- Urudaya, R. S., Sivakumar, P. & Srinivasan, A. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and internal labour migration in India: A ‘crisis of mobility’. Indian Journal Labour Economics, 63(4), 1021–1039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00293-8

- World Bank (2020). Ghana COVID-19 Emergency Preparedness and Response Project. http://documents1.worldbank.org

- World Health Organisation (2018), Refugee and migrant health. WHO. Accessed 1 July 2020. www.who.int/migrants/en/

- World Health Organisation (2021). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID 19) dashboard. Accessed 6 November 2021. https://covid19.who.int

- Yeboah , T., Owusu, L., Arhin, A. &, Kumi, E. (2014) Fighting poverty from the street: Perspectives from some female informal workers on gendered poverty and livelihood portfolios in Southern Ghana. Journal of Economic and Social Studies, 5 (1) 239–267

- Yu, C., Lou, C., Cheng, Y., Cui, Y., Lian, Q., Wang, Z., Gao, E., & Wang, L. (2020). Young internal migrants’ major health issues and health seeking barriers in Shanghai, China: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6661-0