Abstract

This study analyses forestry governance by assessing the situation of local and central governments’ land-use activities. Governance networks and regulations on intergovernmental functions support to shape patterns of coordination. Collaborative governance is often cited as a way to develop a plan for the sustainable management of forest land use. However, an empirical approach to collaborative governance is still lacking. This research investigates which factors of collaborative governance practices correspond to forest land use. Hence, understanding their roles is essential to managing networks for forest management activities. The findings of the study demonstrated that collaborative governance has changed away from information sharing and toward forestry governance and policy network. Furthermore, forest land use also emphasizes guidelines for preventing the spread of land-clearing fires, which is an important aspect of fire prevention in general. The fires from 2010 to 2018 affected agricultural lands, plantations, forests, and swamps. The clearing of peatland for oil palm and timber plantations appears to be the main source of smoke-haze and is indicated as the primary driver of land clearing motives in Riau Province, Indonesia. Nvivo-12 was used as a tool to codify each interview result. Observations were coded for discussion, and the work refined the findings from the analysis. The data were then transferred to Gephi to allow networking analysis. The network was combined using the Gephi software. NVivo was also used to explore forest land-use activities by combining network analysis to assess the pattern of collaboration.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The collaborative governance models illustrate coordination capability from the local to the central government, which has implications for future operational forest land-use management practices. The governance of environmental problems such as forest land-use management often involves multiple stakeholders, and it may be different purposes and capacities. Given the fact in the respective regions, the political structure government is expected to make an effort to increase the stakeholder’s involvement in forest management for responding to forest land use sustainably.

The governance network analysis is carried out to describe clusters from each level of the central, regional, and district governments by bringing up keywords from each cluster from the analysis results. The study’s findings demonstrated that collaborative governance had changed away from information sharing and toward forestry governance and policy network. Furthermore, forest land use also emphasizes guidelines for preventing the spread of land-clearing fires, which is an essential aspect of fire prevention in general.

1. Introduction

Oil palm is a potential source of crude palm oil (CPO). It plays a crucial role in both social and economic sustainability. Indonesia has a significant oil palm production, which has been increasing the demand for suitable land. Palm oil grows at a rate of approximately 15% per year (Agustiyara et al., Citation2021). There are 3.1 million hectares of palm oil plantations (smallholders plantations at 45.59%, company-owned plantations at 49.94%), and 1.6 million hectares of industrial timber (CIFOR, Citation2018; Nurfatriani et al., Citation2015; Rianto, Citation2015).

Forest fires and land use require the attention of many local and central governments. These problems have led to 1,753 people suffering from acute respiratory infections (Infeksi Saluran Pernapasan Akut-ISPA) due to land fires and haze, and more areas have also been impacted (E. P. Purnomo et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the land fires in Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, South Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, and East Kalimantan from 2010 to 2018 caused environmental, economic, and social problems. The financial loss was over USD 16 billion, covering health, education, germplasm, carbon emissions, and others (H. Purnomo et al., Citation2016). These latest fire events were more severe than those in 1997. The lack of peat swamp ecosystem management and the long dry season due to El Niño caused much more haze than mineral soil fires (Medrilzam et al., Citation2014). It is estimated that 2.61 million hectares of land were burned, 33% of which was peatland covering 869.754 hectares.

Meanwhile, fires in mineral soil burned 1.741.657 ha, or 67% of the land. This has significant negative impacts, including damage to water resources, carbon emissions, destruction of vegetation, loss of biodiversity, health costs, and costs of restoring ecosystems (Cacho et al., Citation2014). The global effects of fires include global warming, decreased temperature, light intensity, and had potential impact on El Niño (Adam & Heiduk, Citation2015).

To address land fires, peatlands require canals for land clearing, which is significantly increasing for the cultivation of oil palm. Various actors are interested in benefitting from converting land use into productive lands, such as planting oil palm and rubber (Enrici & Hubacek, Citation2018). Fire is often used to clear land, as observed in oil palm cultivation, because it is a cheap and easy method (E. P. Purnomo & Agustiyara, Citation2021). Land conflicts, land claims, and a lack of incentives to prepare land without burning are among the causes of fires (Dutu, Citation2016). It is argued that local elites benefit from this activity while smallholder farmers are placed in an unfavorable position (Kleinschmit et al., Citation2016). The primary motivation behind land fires is profit, followed by agricultural production and financial investment (Enrici & Hubacek, Citation2018). This study differs from previous research on forest fires in that it used social network analysis to address the sources and distribution of power from which land fire actors benefit (Agranoff, Citation2006; Füg, Citation2011; Schweinsberg et al., Citation2017). However, as it relates to the political economy of forest and land fires, the current study provides an understanding of deforestation linked to palm oil.

In land fire issues, laws and regulations to prevent land fires have been issued by the government. Given the rise of deforestation in peatland areas, attention related to environmental, economic, and social aspects is required (Afriyanti et al., Citation2016). Subnational governments should pay equal attention to forests that have been transformed into oil palm plantations since the palm oil industry has been one of the major causes of deforestation in recent years (H. Purnomo et al., Citation2016). The conversion of land into oil palm plantations has significantly increased and led to more apparent land concession in the forestry area (Nurfatriani et al., Citation2015). In addition, laws and regulations must ensure that there are no overlapping or complicated concessions when it comes to forest land use (E. P. Purnomo et al., Citation2019). This view shows that regional regulations have responded to significant deforestation and the largest concession that led to deforestation. However, many policies and regulations have not resolved forestry issues (Medrilzam et al., Citation2014).

Governance and policy networks have imposed collaborative governance in intergovernmental roles to shape coordination patterns. Although some organisations play essential roles in forestry activities, they may not have the power to involve more actors (Brockhaus et al., Citation2012; Cacho et al., Citation2014; Nurfatriani et al., Citation2015; Prabowo et al., Citation2017; H. Purnomo et al., Citation2016). Meanwhile, (Kleinschmit et al., Citation2016) investigated collaborative management for forest policy analysis and (Coulston et al., Citation2014; Medrilzam et al., Citation2014) analysis of forest land use. Collaborative governance in forestry includes the intergovernmental actor’s coordination and communication between the local and central governments, which are described through social network analysis (F. Andersson et al., Citation2017; Giest, Citation2015). This led to the development of an assessment of the pattern of intergovernmental networks for collaboration. The central government shifted in a political structure that affected all sectors, including forestry management. Its impact on the local government is related to unclear guidelines for forest land-use policy implementation.

Collaborative governance is often cited as a way to develop a plan for sustainable management of forest land use. However, an empirical approach to collaborative governance is still lacking. Hence, this study examines the extent to which collaborative governance techniques are effective in responding to forestry concerns. Land usage in forest areas is managed by both local and central governments, which have an impact on deforestation and forest fires. As a result, understanding their functions is essential to effectively managing networks in forest management activities.

2. Literature review

2.1. Collaborative governance (CG)

A few studies have theorised on the governance of forest management (Ansell & Gash, Citation2008). The term ‘governance” here refers to the process of achieving collaborative performance targets along with stakeholders participation in the process. Moreover, collaborative governance has emerged as a response to improved forest management practices, which focus on multi-stakeholder participation . Some collaborations are voluntary, and some are mandatory by the states or government (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003). The collaboration process entails adapting integrated components of a relationship, commitments, organisational roles and functions, and pursuing balances between stakeholder integration and aggregation (Honig, Citation2006; Lane & Hamann, Citation2003). Another line of research considers collaboration action, which implies that the government is responsible for policy implementation (Debela & Meer, Citation2020). Policy implementation should focus on what is implementable and what works rather than investigating the underlying conditions (Netto et al., Citation2017). It also shows that the existing policies have proven ineffective in managing forests. There is a gap between the policy and its implementation. It is important to note that much of this current debate does not explicitly address the government’s way of collaborating to manage forest land use. For collaborative governance among stakeholders, this research design integrates local government efforts that may overlap. In this view, the collaborative governance process within the provincial government is elaborated in order to illustrate government authority and communication, local government capacity, norms, governance, and networks in the provincial government network.

Several research findings show that the fundamental cause of deforestation and degradation is fragmentation due to development and economic activities, such as plantations in forest areas occupied by smallholders and industrial companies (H. Purnomo et al., Citation2016). Environmental issues related to forest management have been empirically examined using different approaches. Previous work on forest management has emphasised forestry emission reduction, which focuses on land degradation, industry, and forest plantations (Verchot et al., Citation2010). Moreover, past research has primarily asserted the environmental issues of policy enforcement, generating economic, social, and ecological problems. Some of them identified forest land use, such as degradation, fires, and damaged forest areas.

It essentially boils down to a literature review (Kramer, Citation1990) defining inter-organisational collaboration as an emergent process among interdependent organisational actors who negotiate the solution to share concerns. According to O’Toole (Citation1997), inter-organisational collaboration is considered a network for collaboration and collaboration as a decision-making tool for collaborative networks (Smith, Citation2015). Network management offers an introductory class of collaborative governance models. Network management modelling was conducted here to examine the general impact of public administration on government performance.

2.2. Network management (NM) in forestry governance

Network management modelling discerns the effect of these functions and the organisational resources used to perform them in particular structural contexts (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003). A network structure can represent other network structures in various forms. Social network analysis (SNA) is used to define multiple networks consisting of actors (Freeman, Citation2004), who aim to address governance and social capital in networks. Even relatively small groups of actors form complex network structures that can be discovered using SNA methods but are hard to detect otherwise, as social structure is usually a mix of cohesive subgroups (Borg et al., Citation2015).

Network management is intended to examine the general impact of public administration on government performance. First, policies dealing with ambitious or complex issues are likely to require such structures in the execution, which assert that the types of problems or topics society seeks to collectively address are increasingly appalling, or are “problems with no solutions, and only temporary, an imperfect resolution”. Second, the government has limitations in building networks, so direct action by the government is strongly encouraged for a network-based approach. Collaborative structures are also needed to address specific problem areas, with more government action and government involvement. When the public demands action on specific public issues, multiple players are drawn together to fulfil that demand because it can only be done through collaboration. Third, political imperatives elicit networking beyond what might be necessitated by policy objectives; the actors must often balance technical needs for precise and concentrated program authority with political demands for broader influence. Fourth, as information regarding second-order program effects has accumulated, efforts have been made to institutionalise the connections, such as inter-organisational task force and planning. Fifth, layers of mandates, including crosscutting regulations and crossover sanctions, provide additional pressure for managing networks (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003). Hence, the term collaborative governance is used to describe forest management problems that accommodate the political interests of both local and central governments. It shows the involvement of intergovernmental linkages and their participation in forest governance through a collaborative governance approach.

The concept of governance is now firmly embedded in our understanding of public administration, but there is still a tendency to conflate various governance concepts. Collaborative governance (CG) and Network management (NM) are two key concepts in governance literature that have been used interchangeably. For example, NM is defined as “to examine the general impact of public administration on government performance” (Agranoff, Citation2006; Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003; K. Andersson, Citation2017; Chen & Lee, Citation2018) based on the principles of trust, reciprocity, negotiation, and mutual interdependence among actors. These same elements of NM are also the characteristics in the definitions of CG (Ansell & Gash, ; Kathrin, Citation2019; O’Leary & Vij, Citation2012). For instance, a governing arrangement in which one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative collective decision-making process intending to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or resources.

However, such an interchangeably used between the two concepts might further impact the significance of building CG theory in supporting a general theorization of collaborative governance. Therefore, combining these two terms is needed for subsequent theory development in this forestry governance research. This article attempts to explore the close indicators between NG and CG. How will the current conceptualizations of CG and NM merge to contribute to building governance literature and guide forestry governance practices? The NM is a structural concept emphasizing more on organizational networks to facilitate inter-organizational interactions among network members. While CG is a process concept emphasizing how multiple actors come together to collaborate, that implicates governance practices. Thus, a combined analysis of the theories studied in CG and NM literature could explicate the extent of the concept of collaborative governance, especially in terms of the forestry governance context.

3. The research method

This qualitative research used a descriptive approach, in which data were collected through observations and in-depth interviews. This method comprises primary and secondary data collection (Goodwin & Horowitz, Citation2015). By using six indicators related to collaborative governance, the current study aims to explore government authority and communication, and local government capacity, norms, governance, and networks that simultaneously lead to network management activities. A more expected result was that these forest land-use adjustments are essential in describing collaborative governance itself. The overarching aim of this research is to study the collaborative governance that affects policy implementation practices in Riau Province, Indonesia. The six specific issues of collaborative governance are presented in Figure . The overarching scope of collaborative governance can examine and analyse the components of forest management practices in Riau Province.

Within the scope of the research, we conducted interviews and observations. This work is designed to measure the roles of targeted government institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and underlying local government networks. Network analysis can indicate the patterns of network management.

First, the scope of research based on desk study and observation can be used to describe the roles of government organisations, civil society organisations, NGOs, and the public. The identification of sustainable forest land use management and analyses of land areas and changes were visualised using NVivo-12. Second, the Gephi software was used to illustrate the relationship between different actors framing organisational and interpersonal relationships among stakeholders. SNA emphasises the importance of a research approach involving multiple entities (McCurdie et al., Citation2018), to address networks among actors. Gephi is an open-source network visualisation analysis platform whose features lead to a better understanding of the pattern of communication and interaction of linked actors in creating a collaboration network (Cock et al, Citation2015; Graham et al., Citation2015).

The study’s limitations include following the indicators, political structures, regulation, trust, and cost as essential indicators of network management in the local government. Observation data could likely be seen as a limitation when studying organisational networks. Interview data used to support the findings (Copes & Miller, Citation2015) may reliably assess the validity of the indicators.

3.1. Research setting

The research focus is Riau Province, Indonesia. It explores how network management models illustrate management within the networks. Riau is the most significant expansion area for plantation and oil palm industries in Indonesia. in 2015, out of the 3 million hectares of land in Riau, 51% or 1.6 million hectares of industrial forest concession (HTI) were used for oil palm plantations (CIFOR, Citation2018). The concession areas mainly covered the province. The site is typically a peatland area, which suffered the highest number of forest fires in Sumatra (E. P. Purnomo et al., Citation2021). The structure of forest land allocation permitted the establishment of a palm oil plantation. This is a forest concession that has become common practice and most likely leads to deforestation (Afriyanti et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2016); (see, Figure on land types and allocation).

Shown above is a map of the location of Riau Province’s facilities—a virtual landscape aimed at describing the complexity of forest resource management. There is a general increase in forest land concessions and a decreasing number of forest areas due to many forest land-use allocations that are more difficult to control. There is a need to consider local government roles involving multiple actors and the growing networks of stakeholders (Agranoff & McGuire, Citation2003; H. Purnomo et al., Citation2016).

3.2. Population and sample

Grouping and networking based on interviews and observations identified more organisational networks and organisational and interpersonal relationships among stakeholders. The quantifying aspects of Gephi processing, through modularity indicators, analysed the number of stakeholders that connected actors in the network who partially overlapped and lacked involvement (Ellison & Hardey, Citation2015).

Practically speaking, we collected and analysed data regarding forest land-use policy by interviewing government officials at the district and provincial levels. The primary data were collected by conducting in-depth interviews with thirty-one (31) informants ranging from central, provincial, and village levels (see ). At the very least, the contents of the interviews included: Who was involved in promoting forest management through collaboration? What did they do, when, why, and how? To what extent do activities encourage stakeholders to collaborate in resolving issues of forest land use? What other actions or policies should be implemented in response to forest land-use management issues? Also, during the ethical process for the interviews, participants have been informed at the outset of the purpose and scope of the study, the types of questions likely to be asked, and so forth.

Table 1. Interviews with respondents in the Riau Provincial Government, 2018

During the research, we conducted 60-minute in-depth interviews in the form of open dialogs led by the members or our research team. Subsequently, the findings from the interviews were coded and summarised, organised in charts, shapes, and keywords, to satisfy the analysis goal visualised by NVivo-12. The collected data were analysed using SNA and the Gephi software to visualise the main activities performed by each institution, and coordination. A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was used to organise the analysed data. Numeric results (document counts) from matrix nodes were exported to Excel (CSV file), and 49 descriptors were created for all six variables. Coded words in each cluster represent the number of respondents used to describe essential collaborative governance issues. The data were then transferred to Gephi to allow network analysis of the data. Network analysis aims to identify the central problems of collaboration patterns among intergovernmental networks.

Based on the descriptive analysis of data collection, several steps were followed. First, in-depth interviews were conducted to describe each key informant’s perspective on forest management, starting from their roles, authority, and policies. The 31 informants represented the government, academicians, communities, and NGOs. Second, observations were made to explore the general conditions of intergovernmental linkages, indicating observation results for approximately 40 hours in small or marginalised groups related to forestry issues. In addition, data were collected from all stakeholders owing to limited data availability and resources. Instead, this research gathered data at the provincial government level from 18 stakeholders with roles and influence on forest management under the governor’s coordination. These agencies were observed primarily to see network management on forest land use.

4. Results and discussion

This research has demonstrated six assessment indicators for collaborative governance. Based on the conceptual framework, we found those problems which were relatively significant to deal with and were typical in identifying land use policy implementation by the central and local governments. We adopted a collaborative governance approach as a two-way communication system between central and local governments in response to the need for forest land use governance. Communication might differ in terms of shared understanding of different policies and regulations and how they can be implemented (F. Andersson et al., Citation2017; Giest, Citation2015). In particular, policy coordination is a platform for central and local governments to establish forestry governance through collaboration.

The implementation of collaborative governance must determine the means and interests based on the government’s capability. Collaborative governance is used to focus on stakeholder participation to find the right balance between land allocation policies and processes (Brockhaus et al., Citation2012; Cacho et al., Citation2014; Nurfatriani et al., Citation2015; Prabowo et al., Citation2017; H. Purnomo et al., Citation2016). The distribution of land has remained purely a matter of prioritising timber and oil palm enterprises. The government pursues economic growth and increased revenue, initially focusing on forest production, without considering its long-term contribution. This finding, supported by Enrici and Hubacek (Citation2018), argues that a collaborative governance approach develops a strong working relationship and builds collaboration with stakeholders in governance scenarios. Collaborative governance principles are employed to address critical issues of governance and interoperability (Honig, Citation2006). Nurfatriani et al. (Citation2015) argue that collaboration shares power arrangements and describes negotiation and commitment processes as participative governance in policy implementation. There are causes and effects of the government’s lack of cooperation, such as the lack of authority structure in a hierarchical division, awareness and responsibility, legitimate interest and power, and mutual understanding to reach an agreement.

The expanded collaborative governance activities have led to a new understanding of generated management, both at the local and central levels. The findings show that the forest land-use policy between local and central governments has changed as a result of decentralising forest management operations and the consequent transfer of local government power to the central government’s administration of forest areas. Indeed, local and central governments need to develop better communication and coordination through collaborative governance. The coordination between the central and local governments often resulted in a lack of trust among them, owing to issues such as disagreements over the forestry boundaries, illegal logging activities, and the government’s inability to manage forest land-use activities due to a gap in policy implementation. It has subsequently led to a “tyranny policy”.

Collaborative governance practices between central and local governments begin to highlight the finding assessments through interview-based observations, which can construct generalisations about some significant issues in collaborative governance. This allows a better understanding of each specific issue, as shown in Figure .

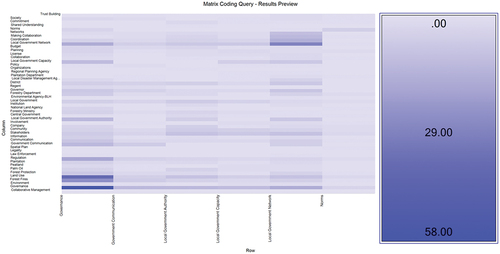

Figure 3. The matrix of collaborative governance assessment, 2019.Note: Jaccard’s coefficient (0 = least similar, 60 = most similar).

The average rating of each particular issue on collaborative governance, the result of the “Jaccard’s coefficient” test for finding differences between six specific points on the collaborative governance approach was calculated based on interview transcript coding items (columns = each different word that appears in the text of the sources, and top words in word frequency query results; rows = main indicators for collaborative governance assessment).

The result of the “Jaccard’s coefficient” test based on the averaged items score of the respondents in the interview transcripts show that out of six scopes of collaborative governance, two (i.e., “governance” and “local government networks”) are significant in collaborative governance practices. The figure above summarises the average indicators related to forest land-use policy, rating, and colour-coding them based on developed themes. The use of coding was synchronised with related forest land use issues and forest governance activities. Within these scopes and categories, coding analysis was used to identify the sub-categories of data.

There are 49 factors, including the six recorded and presented indicators of collaborative governance assessment generated from the matrix word query synthesis. The qualitative data were derived from in-depth interview results. The connection between one indicator and the others is presented in Figure , which was made using the most frequent words and connections between them. The matrix diagram and connecting links and comments are proportional to the number of common issues related to collaborative governance. The related factors are the composition of the most vital connections to the indicators. This finding is considered essential in describing collaborative governance. For example, the term “governance” has the most substantial connection with forest fires, regulations, and land use issues. “Government communication” is related to community and information. “Government authority” refers to central and local governments in terms of authority distribution. “Local government capacity” is influenced by budget and permits. “Norms” refer to commitment and shared understanding. Last, “local government networks” are related to coordination and establishing collaboration networks. These indicators are intuitively expected, and constitute the model of collaborative governance. However, a couple of indicators are the most commonly problematic issues, namely, governance and local government networks. The word matrix leads to an understanding of forest land use issues based on the results of interviews and observations, especially the interrelationships of the six main keywords.

Based on these coding query results, many important issues have been identified. The scopes of collaborative governance that were significantly related are governance and local government networks. Regarding “governance”, the row of sub-categories is highly integrated, such as forest fires and land use, and fundamental analysis, which evidently pertain to governance issues about forest fires and forest land-use. This means that governance is highly integrated, functioning as collaborative governance. The inability of governance to respond to forestry governance practices raises serious problems regarding forest land-use policy. An example is the substantial increase in the amount of land used as forest resources have been managed and allocated by both central and local governments and transferred to lower-local governments. Forest governance also has to manage forest plantations, village forests, conservation forests, and land concessions by companies. Due to several causes, such as lack of power in local government, and illegal logging, which led to deforestation, shifting massive forest land-use access has resulted in forest fires. There are several reasons for governing forestry management activities. First, forestry policies are generally made to increase forest production activities, land ownership structures, and government regulations in maintaining and protecting forest systems. Second, forest land-use activities need to be coordinated with the governor, as the head of the province, prior to policy implementation. Concurrently, there is a need to develop government communication relating to forest land use permits under the current forestry conditions. Ungoverned forest land-use issues on the treatment of small-to medium-scale forest land-use allocation fall under the local government’s authority, while the central government decides the large-scale forest land-use allocation, which falls under the purview of the Ministry of Forestry and the National Land Agency. On the other hand, forestry governance’s function to facilitate sustainable forest products, including forest land-use permits, needs to be regulated through collaborative governance.

Another coding query result is presented here as “local government networks”. The matrix result shows that local government networks is more associated with engaging in collaborations that require intergovernmental networks. The dynamic networks within forest land-use activities link the structure among the stakeholder networks, relating to how the central and local governments are more concerned with building coordination than linkage hierarchies, in which the activities affect the strategic action between multiple actors involved.

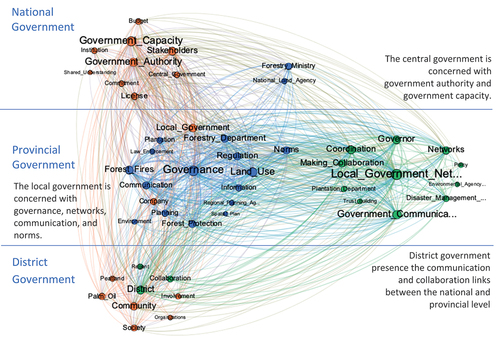

According to the contents and matrix words, nodes (data codes) identified patterns and relationships emerging from the data. The matrix coding query shows that governance and local government networks have higher correlation scores and are related to forest land-use issues. Furthermore, these relationships were diagrammed as networks using Gephi based on the coding results, as shown in Figure .

Figure 4. Relationships diagrammed as networks using Gephi software based on coding results, 2019.Note: The figure above displays the main component of collaborative governance of six indicators that nodes reflect across central and local governments. The size and vertices of the networks are in different positions at the government level. Colour of node = modularity; measure of node = network degree; the colour of tie = sources of the tie. Data analysis of in-depth interviews was visualised by Gephi, 2019.Sources: Data Analysis of In-Depth Interviews Visualised by Gephi, 2019.

The network analysis is carried out to describe clusters from each level from the central, regional, and district governments by bringing up keywords from each cluster from the results of the analysis. According to the results, the findings from the network analysis describing the pattern through the most problem in forestry governance consists of three clusters. First is the cluster that is currently involved in green lines and nodes are considered the relationship consequent of structures. In particular, we find that local government networks provide roles and are influenced by local government actors, especially the governor as the head of the province. Given the distribution of these networks related to coordination issues, this may have implications for regional and district governments due to the distribution of these networks related to coordination concerns. Second is the cluster that is currently involved in orange lines and nodes which has explored the role of vertical and horizontal networks that require the local government’s capacity to collaborate with the central government. The network illustrates how the local government’s capacity impacts the collaboration process, which is connected to stakeholders such as the community, companies, government institutions, and the central government. It also highlights the network of forest management activities in which actors and issues are linked. The central and local governments’ actions may impact other network structures and impact (change) the network itself (on which the other actors are dependent). This interplay between the network structures was analysed to explore the networking analysis. Social network analysis offers essential tools as it is used to display the various relationships that occur and the network structure arising from these relationships. The third cluster is currently involved in blue lines and nodes which illustrates the complexity of intergovernmental networking problems, such as governance for forest fires and land-use practices, and government communication. The ties of the networks were generally stable and primarily mutual. Interestingly, there were three types of this, namely: the central government, local government, and environmental factors, all of which may involve the community, companies, and government institutions as part of response to forest land management problems.

These processes imply that collaboration requires an emergent process among interdependent organisational actors (inter-organisational networks) who negotiate to deal with environmental issues. We argue that the main problem in forestry governance is that it is challenging to negotiate and compromise in terms of political approaches because there is a lot of pressure at various government levels. Collaborative governance accommodates the institutional framework to engage in local-level collaboration and pursue the interest of providing coordination and communication for mutual benefit, especially in forest land use management. These findings differ from those obtained by Brockhaus et al. (Citation2012) who observed conflicting policies, institutional clarity, and coordination, underpinned by a development paradigm in forestry governance. It has been clearly seen by Kramer (Citation1990), O’Toole (Citation1997), and Smith (Citation2015) that collaborative governance is required to achieve and resolve policy implementation problems in forest land use management, which mainly involves the consideration of factors that explain the involvement of actors’ behaviour. Thus, this situation is widespread across Indonesia’s forestry governance as a result of the country’s shift from an authoritarian government to weak leadership and local government in relation to the authority network.

Moreover, some stakeholders do not support forest management activities and even undermine the government. In such cases, communication needs to be established with all the actors. For instance, forest management policy, which involves central and local governments in determining the boundaries of forest and protected forest areas, is supervised by the Ministry of Forestry. According to Giest (Citation2015), policy needs to serve the stakeholder’s operation, control the behaviour, and organise incentives in the institutions. One of the critical problems in forest management is the different perceptions among stakeholders regarding the extent, boundaries, management rights, and utilisation of protected forests. Meanwhile, E. P. Purnomo et al. (Citation2019) suggest that this case has the potential to unify these perceptions and apply collaborative governance among the government, community, and other related parties. The discrepancy between the central government’s policies and the local governments is detrimental to the forest and its ecosystem if not immediately managed using government-initiated collaborative governance.

The stakeholders’ involvement in policy implementation at the local government level is unresponsive and less transparent. Legally, there are forest management authorities such as: (1) the central government, which is authorised to establish norms, standards, guidelines and criteria, policy, law enforcement, and facilitation of the rules of protected forests across provinces; (2) the provincial government, which is authorised to regulate and manage cross-protected forest regency made by the central government; and (3) the regional/municipal government, which is allowed to regulate and control the protected forest established by the central government. However, these authorities show that they need to build a local government’s capability to achieve coordination among various government levels and support collaborative governance practices. We argue that the distribution of power between the central-provincial-regional-district governments is a powerful actor that shapes forestry policies. Moreover, there are complete power-sharing changes in all of the paradigm elements, that is, new actors becoming crucial for forestry and new collaborative governance systems emerge. Policy implementation without considering the capability and readability of the government has shown a very slow establishment rate so far (F. Andersson et al., Citation2017; Giest, Citation2015). Concurrently, the degradation of forest areas shows that government policies remain ineffective.

These circumstances can lead to a tyrannical policy because an excessive number of departments or institutions are involved in managing networks for forest management activities. In terms of collaborative governance and networking, the relevant actors only work for their own benefit and prefer to follow procedural and bureaucratic procedures; thus, there is a need for a central-local mediator (Kirlin & Kirlin, Citation2014; Waring & Crompton, Citation2019). There are several issues that require consideration, namely, authorities at both the local and national levels, and power imbalances in implementing the forest land use policy. Institutional development is crucial for preventing policy gaps. Using collaborative governance contexts and customs is critical when dealing with forest land use policies and processes in Indonesia. At the same time, network analysis demonstrates networks in forest management activities and graph structures. In terms of collaborative networks, these actors influence forest governance procedures to further their own interests. The actors may have power, support, authority, and access to forest resources.

In this situation, collaborative governance in forest land use implicates to the network in policy implementation (Song et al., Citation2017), and development for forestry (Eghenter, Citation2006). Additionally, there must be a progressive reform of the frontline bureaucratic forest authority in building communication among land-use management institutions. A possible means of unifying land-use policy perceptions is the establishment of collaborative governance that significantly impacts policy implementation development.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, collaborative governance is primarily addressed through the analytical framework used in this study. The empirical research question has emerged and persisted on the pattern of forest land-use policy implementation through collaboration to ensure sustainability, both by the central and local governments. However, the lack of collaborative governance following the empirical findings of this study is as follows. First, the pattern of collaboration observed indicates the absence of a mutually recognised coordination between local and central governments that impacts the functions of forestry management networks in the context of their network cycles. Second, collaborative governance allows intergovernmental networks to enable local and central governments to facilitate improved coordination among linkage actors. This finding also shows a long coordination process in building collaboration, and that the existing communication among institutions is fragile. This result also occurs because a relatively large authority is borne by only one institution or agency.

The theoretical contribution lies in the approach to conceptualising collaborative governance on forest land use policy and the inter-related roles of policy implementation in Riau Province. Overall, the identified factors of collaborative governance that can facilitate forestry governance is as follows. First, the government has tried to unify forest management policy views on the scope, limits, management rights, and use of protected forest to make the needs collaborative. Second is the establishment of communication with all the necessary actors, especially from local governments to the centre. There is a need to improve the local government’s capacity to achieve coordination among governments and support collaborative governance practices. Third is the condition to jointly create rules and a structured network among the intergovernmental networks that will govern their relationship and involve shared norms and mutually beneficial interaction of stakeholders in forest land-use management.

In terms of collaborative governance based on the conceptual framework, the fourth factor found that the terms “governance” and “government network” differ significantly from the four indicators of the findings of the collaborative governance analysis. It is possible to resolve these fundamental problems in forest-land use management without losing government authority and communication, norms, and local government capacity. The importance of these indicators is generally associated with collaborative governance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to show our gratitude to the blind reviewers and the editor for giving us very constructive comments and suggestions. We would also thank to Prof. Dr. Achmad Nurmandi, M.Sc from Jusuf Kalla School of Government, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sataporn Roengtam

Prof. Sataporn Roengtam, Ph.D., is a Professor in the Department of Public Administration Program, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (HUSO), Khon Kaen University. He is an Executive Member of the Asia Pacific Society for Public Affairs (APSPA). Research fields of interest include governance, public policy, decentralization, and citizen engagement in public administration. He is also interested in conducting more research on how to increase co-governance among governments, private organizations, and people in local governance.

Agustiyara graduated from the Master’s Program in Public Administration, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (HUSO), Khon Kaen University, Thailand. The area of research interests are public policy and sustainable development. Currently, as the Assistant Research at Jusuf Kalla School of Government (JKSG), Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

References

- Adam, S., & Heiduk, F. (2015). Hazy days : Forest fires and the politics. Journal Of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 34(3), 65–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341503400303

- Afriyanti, D., Kroeze, C., & Saad, A. (2016). Indonesia palm oil production without deforestation and peat conversion by 2050. Science of the Total Environment, 557–558, 562–570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.032

- Agranoff, R. (2006). Inside collaborative networks: Ten lessons for public managers. Public Administration Review, 66(SUPPL. 1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00666.x

- Agranoff, R., & McGuire, M. (2003). Collaborative public management: New strategies for local governments. Georgetown University Press.

- Agustiyara, E. P. P., Ramdani, R., & Ramdani, R. (2021). Using artificial intelligence technique in estimating fire hotspots of forest fires. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 717(1), 12019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/717/1/012019

- Andersson, K. (2017). Understanding decentralized forest governance: An application of the institutional analysis and development framework. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 2(1), 25–35 https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2006.11907975.

- Andersson, F., Mårell, A., Andersson, F., & Mårell, A. (2017). A European network in support of sustainable forest management Journal of Sustainable Forestry . 9811(January), 37–41 https://doi.org/10.1300/J091v24n02.

- Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18 (4) , 543–571 Retrieved June 8, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Borg, R., Toikka, A., & Primmer, E. (2015). Social capital and governance: A social network analysis of forest biodiversity collaboration in Central Finland. Forest Policy and Economics, 50, 90–97 doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.06.008. Retrieved June 8, 2017, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138993411400118X

- Brockhaus, M., Obidzinski, K., Dermawan, A., Laumonier, Y., & Luttrell, C. (2012). An overview of forest and land allocation policies in Indonesia: Is the current framework sufficient to meet the needs of REDD+? Forest Policy and Economics, 18, 30–37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2011.09.004

- Cacho, O. J., Milne, S., Gonzalez, R., & Tacconi, L. (2014). Benefits and costs of deforestation by smallholders: Implications for forest conservation and climate policy. Ecological Economics, 107, 321–332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.09.012

- Chen, Y. C., & Lee, J. (2018). Collaborative data networks for public service: Governance, management, and performance. Public Management Review, 20(5), 672–690. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1305691

- CIFOR. (2018.) Jaringan Kerja Penyelamat Hutan Riau. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Retrieved June 8, 2017, from http://www.cifor.org/ilea/Database/instrumen/JikalahariprojectILEA201108.pdf

- Cook, I. G, Halsall, J.P., Wankhade, P. et al. (2015 A Public Health Perspective). Sociability, social capital, and community development: A public health perspective. Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11484-2.

- Copes, H., & Miller, J. M. (2015). The Routledge handbook of qualitative criminology 1st Edition (London: Routledge) 328 https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203074701 .

- Coulston, J. W., Reams, G. A., Wear, D. N., & Brewer, C. K. (2014). An analysis of forest land use, forest land cover and change at policy-relevant scales. Forestry, 87(2), 267–276. Retrieved June 8, 2017, from https://academic.oup.com/forestry/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/forestry/cpt056

- Debela, K. W., & Meer, R. Local governance in Switzerland: Adequate municipal autonomy cumintergovernmental cooperation? (2020). Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1), 1763889. ed. Richard Meer. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1763889

- Dutu, R. (2016). Challenges and policies in Indonesia’s energy sector. Energy Policy, 98, 513–519 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.09.009.

- Eghenter, C. (2006). Social, environmental and legal dimensions of adat as an instrument of conservation in East Kalimantan ANU Press . Retrieved June 8, 2017, from http://hdl.handle.net/1885/240842

- Ellison, N., & Hardey, M. (2015). Social media and local government: Citizenship, consumption and democracy. Local Government Studies, 40(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.799066

- Enrici, A. M., & Hubacek, K. (2018). Challenges for REDD+ in Indonesia: A case study of three project sites. Ecology and Society, 23(2), 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09805-230207

- Freeman, L. C. (2004). The development of social network analysis In Document Design. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2005.01.010

- Füg, O. C. (2011). Coalition networks and relational policy analysis. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 10, 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.01.002

- Giest, S. (2015). Comparative analysis of sweden’s wind energy policy: The evolution of ‘coordinated’ networks. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(4), 393–407 https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2015.1017302.

- Goodwin, J., & Horowitz, R. (2015). Introduction: The methodological strengths and dilemmas of qualitative sociology. Qualitative Sociology, 25, 33–47 https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014300123105.

- Graham, M. W., Avery, E. J., & Park, S. (2015). The role of social media in local government crisis communications. Public Relations Review, 41(3), 386–394. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.02.001

- Honig, M. I. (2006). New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity. SUNY Press, 300 https://sunypress.edu/Books/N/New-Directions-in-Education-Policy-Implementation.

- Kathrin, B. (2019). Collaborative governance in the making: implementation of a new forest management regime in an old-growth conflict region of British Columbia, Canada. Land Use Policy, 86(February), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.04.019

- Kim, Y. S., Bae, J. S., Fisher, L. A., Latifah, S., Afifi, M., Lee, S. M., & Kim, I.-A. (2016). Indonesia’s forest management units: Effective intermediaries in REDD+ implementation? Forest Policy and Economics, 62, 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.09.004

- Kirlin, J. J., & Kirlin, M. K. (2014). Strengthening effective government–citizen connections through greater civic engagement. Public Administration Review, 62(4), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.62.s1.14

- Kleinschmit, D., Bocher, M., & Giessen, L. (2016). Forest policy analysis: Advancing the analytical approach. Forest Policy and Economics, 68, 1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2016.05.001

- Kramer, R. (1990). Collaborating: Finding common ground for multiparty problems. Academy of Management Review, 15(3), 545–547 https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1990.4309133.

- Lane, B., & Hamann, T. (2003). Constructing policy : A framework for effective policy implementation. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, Chicago , 1–26 Retrieved from https://instll.com/resources/instll_constructingpolicy20.pdf.

- McCurdie, T., Sanderson, P., & Aitken, L. M. (2018). Applying social network analysis to the examination of interruptions in healthcare. Applied Ergonomics, 67, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.08.014

- Medrilzam, M., Dargusch, P., Herbohn, J., & Smith, C. (2014). The socio-ecological drivers of forest degradation in part of the tropical peatlands of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Forestry, 87(2), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpt033

- Netto, R., Veríssimo, J., Assumpção-Rodrigues, M. M., & Chamberlain, J. M. Skill formation, cultural policies, and institutional hybridity: Bridging the gap between politics and policies at federal and state levels in Brazil. (2017). Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1361601. ed. John Martyn Chamberlain. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2017.1361601

- Nurfatriani, F., Darusman, D., Nurrochmat, D. R., Yustika, A. E., & Muttaqin, M. Z. (2015). Redesigning Indonesian forest fiscal policy to support forest conservation. Forest Policy and Economics, 61, 39–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.07.006

- O’Leary, R., & Vij, N. (2012). Collaborative public management: Where have we been and where are we going? The American Review of Public Administration, 42(5), 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074012445780

- O’Toole, L. J., Jr. (1997). Treating networks seriously: Practical and research-based agendas in public administration. Public Administration Review, 57(1), 45–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/976691%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/10.2307/976691.pdf?acceptTC=true

- Prabowo, D., Ahmad Maryudi, S., Imron, M. A., & Imron, M. A. (2017). Conversion of forests into oil palm plantations in West Kalimantan, Indonesia: Insights from actors??? Power and its dynamics. Forest Policy and Economics, 78, 32–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.01.004

- Purnomo, E. P., Agustiyara, A., Ramdani, R., Trisnawati, D. W., Anand, P. B., Fathani, A. T., et al. (2021). Developing the assessment and indicators for local institutions in dealing with forest fire dilemma. Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues, 10(3), 1–15 https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060704 .

- Purnomo, E. P., Ramdani, R, Agustiyara, A, Tomaro, Tomaro, Samidjo, G. S., et al. (2019). Land ownership transformation before and after forest fires in Indonesian palm oil plantation areas. Journal of Land Use Science, 14 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1747423X.2019.1614686

- Purnomo, E. P., Ramdani, R., Nurmandi, A., Trisnawati, D. W., & Fathani, A. T. (2021). Bureaucratic inertia in dealing with annual forest fires in Indonesia. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 30(10), 733. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF20168

- Purnomo, H., Shantiko, B., Sitorus, S., Gunawan, H., Achdiawan, R., Kartodihardjo, H., & Dewayani, A. A. (2016). Fire economy and actor network of forest and land fires in Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics, 78, 21–31 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2017.01.001.

- Purnomo, E. P., Vesti Rahmasari, F., Trisnawati, D. W., & Erviana, R. (2021). Observed data of forest fire hotspots effects on respiratory disorder by Arc-GIS in Riau Province, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 717(1), 12036. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/717/1/012036

- Rianto, E. (2015). Dynamics of small-scale deforestation in Indonesia: Examining the effects of poverty and socio-economic development. FAO-Unasylva, 61(1–2), 14–20 https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2016039522.

- Schweinsberg, S., Darcy, S., & Cheng, M. (2017). The agenda setting power of news media in framing the future role of tourism in protected areas. Tourism Management, 62, 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.011

- Smith, Z. A. (2015). Perspective from the field collaborative management in natural resources and environmental administration. Environmental Practices, 17(2), 156–159. Retrieved June 8, 2017, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/FB8DF13F4C09834FBD279A88108B74C6/S1466046615000071a.pdf/perspective_from_the_field_collaborative_management_in_natural_resources_and_environmental_administration.pdf

- Song, A. M., Saavedra, A.C., Temby, O., Sandall, J., Cooksey, R. W., Hickey, G. M. (2017). On developing an inter-agency trust scale for assessing governance networks in the public sector. International Public Management Journal, 22 (4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2017.1370047

- Verchot, L. V., Petkova, E., Obidzinski, K., Atmadja, S., Yuliani, E. L., Dermawan, A., Murdiyarso, D., Amira, S. (2010). Reducing forestry emissions in Indonesia. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Reducing Foresty Emissions in Indonesia.pdf. Retrieved June 8, 2017, Reducing Foresty Emissions in Indonesia.pdf http://forestclimatecenter.org/files/2010

- Waring, J., & Crompton, A. (2019). The struggles for (and of) network management: An ethnographic study of non-dominant policy actors in the english healthcare system. Public Management Review, 22 (2) , 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1588360