Abstract

Female-headed households have now become highly prevalent across the world. Much research in low-income urban populations has identified female household heads as more vulnerable and less secure livelihoods than male households. The study’s main goal was to investigate the livelihoods of female-headed families in Jimma town, southwestern Ethiopia, using a sustainable livelihoods approach (SLA), which examines and evaluates community experiences of poverty and disadvantage. However, this study used a qualitative approach supported by a phenomenological study design to achieve the stated objectives. The study data were collected from March–to July 2019 and involved 30 in-depth interviews, five key informants, and two focus group discussions. This study revealed that since female heads of households have low levels of educational attainment and employment access, most of them fall into the low-income groups, making their livelihood insecure. Besides, based on their gender and marital status, they are treated in hideous ways and isolated from participating in societal affairs, and they are vulnerable to violence. The widowed and those females living as FHHs were mainly blamed for their husbands’ deaths. Therefore, local governmental and non-governmental organizations should facilitate training in income-generating activities and access to credit services for those with the motivation, desire, and capacity to run their businesses and various activities.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENTS

Female headship has increased worldwide, and a large proportion of these HHs are found to be poor. African countries, including Ethiopia, are part of the world where these HHs are high in number and vulnerable to poverty. Yet, most social science research has focused on rural FHHs’ livelihood situations because most believe the overwhelming majority of the country’s population and the poor reside in rural areas. Despite the other studies, this research primarily relied on the urban areas of Ethiopia, particularly the town of Jimma. This study revealed that since female heads of households have low levels of educational attainment and employment access, most of them fall into the low-income groups, making their livelihood insecure. To combat the problem of livelihood insecurity among the FHHs, local governmental and non-governmental organizations should facilitate training in income-generating activities and access to credit services for FHHs.

1. Introduction

Female headship has increased worldwide, and a tall proportion of these HHs are poor. Several works of literature, including Chávez Plazas and Bohórquez (Citation2015), Fitzgerald and Ribar (Citation2003), and McClay and Brown (Citation2000), have confirmed that the number of FHHs has steadily increased in many parts of the world, including developing countries, due to HIV/AIDS and migration, among other factors. African countries, including Ethiopia, are part of the world where these HHs are high in number and vulnerable to poverty. Joshi Rajkarnikar and Ramnarain (Citation2019) assert that in Africa, the number of FHHs is rising and exceeding 20% in most African countries. There are many FHHs in Ethiopia, where 33% are directed by females in urban areas, in contrast to 17% of rural households (Devi & D, Citation2020).

The fact remains that Ethiopian women lag in every aspect and are generally poorer. This is attributed to their less remunerative livelihood than men, low education, and shouldering a triple misfortune: difficulties in generating income, child-rearing, and vulnerability to economic, political, and social crises (Gecho, Citation2014; Sisay Mengesha, Citation2017).

Much research on low-income urban populations has identified FHHs as more vulnerable and have less secured livelihoods than MHHs. As a result, female household heads become involved in the informal sector and perform jobs like petty trade for survival. Andersson Djurfeldt et al. (Citation2013) found that most urban FHHs had extra part-time jobs for survival.

Furthermore, single mothers engaged in informal work such as selling drugs, stolen goods, and sex to supplement their income. As Gecho (Citation2014) confirmed, selling vegetables and fruits, baked goods like enjera and bread, charcoal and firewood, traditional drinks, second-hand clothes and shoes, handicrafts, and goods like sugar and salt are the primary means of living adopted by FHHs in urban areas.

Despite urban areas having more and better economic opportunities than rural areas, many studies show that FHHs in urban areas are unemployed and deprived. They are also victims of urban socio-economic problems as they are likely to have limited access to livelihood assets and opportunities for various reasons (Muleta & Deressa, Citation2014). The vulnerability of FHHs stems from gender inequality in society and women’s low economic status (Muleta & Deressa, Citation2014). Gecho (Citation2014) also wrote that unequal opportunity in schooling for girls and boys in society restricts choices and creative life; households merely headed by women are most vulnerable to poverty.

Because of these complex and diverse phenomena of urban FHH livelihoods, there is a need for intervention and additional research on their living conditions in the country. Yet, most social science research has focused on rural FHHs’ livelihood situations because most believe that most of the country’s population and the poor reside in rural areas.

Various studies have been conducted concerning female-headed households and the need to empower women in the public sphere (Debela, Citation2017; Gecho, Citation2014; Kassa, Citation2013; Muleta & Deressa, Citation2014). This study primarily relied on the town of Jimma (Southwest Ethiopia). This town is highly affected by the rapid increase of FHHs due to rural-to-urban migration, among other reasons. However, none of the above studies has investigated the livelihood situation of urban FHHs in the city. Besides, most of the studies were primarily focused on the women found in the rural areas and were unable to integrate the problem with a sustainable livelihood approach. As far as the researchers were concerned, no detailed study has investigated the livelihood and coping strategies of FHHs in an urban area. Still, there is a lack of appropriate recent sociological research that investigates the livelihood strategies of urban female-headed Households in Ethiopia in general and in the Oromia region in particular because most of these studies, apart from the cited research, are over a decade old and could not have captured the current situation of FHHs. Generally, there are gaps in previous studies on identifying the essential livelihood assets and investigating the economic and social challenges FHHs face. Therefore, having a philosophical investigation of this challenging and multifaceted nature of urban FHHs’ livelihood situation in Jimma City, this study, through a qualitative approach, will contribute to knowledge, methods, and policy tips for responsible stakeholders. Moreover, it helps make various challenges and problems faced by FHHs a subject of sociological analysis, which will have paramount importance for academics, policymakers, and officials to seek alternative ways of solving the challenges they face, which will have implications for sustainable poverty reduction.

2. Study objectives

The main objective of this study was to explore the livelihoods of female-headed households in the study areas by integrating them with a sustainable livelihoods approach (SLA), which is a means of investigating and analyzing the community experience of poverty and disadvantage (see Figure ). However, as stated in the sustainable livelihood approach, this study attempted to explore two objectives. (1) This study investigates the vulnerability and assets of female-headed households, and (2) it investigates the livelihood coping strategies and outcomes of female-headed households in the study areas.

Figure 1. Sustainable livelihood approach frameworks.Source: DFID (Citation1999), p. 1.

3. The rationale for the sustainable livelihood approach

No single theoretical framework analyzes poverty in its entirety. Therefore, in this study, a sustainable livelihood approach was used since it improves the understanding of the livelihoods of the poor and vulnerable (Su et al., Citation2021). Su et al. (Citation2021) say that SLA is based on evolving Livelihoods out how the poor and vulnerable live their lives and the importance of policies and institutions. Additionally, it creates the connection between people and the overall enabling environment that influences the outcomes of livelihood strategies. It also brings attention to bear on people’s inherent potential in terms of their skills, social networks, access to physical and financial resources, and ability to influence core institutions (Gichure et al., Citation2020).

Gichure et al. (Citation2020) highlighted three insights into poverty that strengthen this approach. The first is the understanding that while economic growth may be essential for poverty reduction, there is no automatic relationship between the two since it all depends on the capabilities of the poor to take advantage of expanding economic opportunities. Secondly, there is the understanding that poverty, as imagined by the poor themselves, is not just a question of low income but includes other dimensions such as poor health, illiteracy, lack of social services, a state of vulnerability, and feelings of powerlessness. Finally, it is now recognized that the poor themselves know their situation and needs best and must therefore be involved in designing policies and projects intended to better their lot. Thus, a livelihood framework for development draws on a conceptual framework that may be used to analyze, understand, and manage the complexity of livelihoods.

According to Yirga (Citation2021), the SLF is built around five principal categories of livelihood assets, graphically depicted as a pentagon to underline their interconnections and that livelihoods depend on a combination of assets of various kinds and not just from one category. Therefore, an essential part of the analysis is determining people’s access to different assets (physical, human, financial, natural, and social) and their ability to put these to productive use. The framework offers a way of assessing how organizations, policies, institutions, and cultural norms shape livelihoods by determining who gains access to which types of assets and defining what range of livelihood strategies are open and attractive to people (Suzuki, Citation2021).

Source: DFID (Citation1999), sustainable livelihood guidance sheet

3.1. Study setting

Jimma, the study area, is one of the oldest cities in southwestern Ethiopia. The name of today’s Jimma was derived from the Mecha-Oromo clan called JimmaWayu. These people had started to live in the main quarters of the city, namely, Jiren, Hirmata, and Mendra.

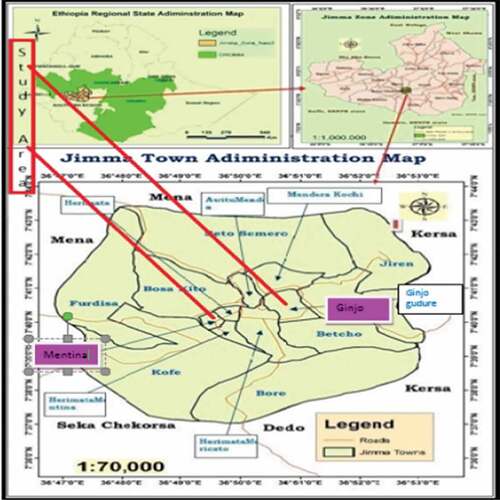

The study was conducted in Jimma City. The city is located in southwestern Ethiopia. The Oromia National Regional State city serves as the administrative city of the Jimma Zone and is bordered by Kersa Wereda to the east, Manna Wereda to the east the north, Manna and Seka Chekorsa to the west, and Dedo to the south. The city is located about 356 km southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. It is situated at an elevation boundary that ranges from the lowest (1720 m.a.s.l.) of the airfield (Kitto) to the highest (2010 m.a.s.l.) of Jiren. The city is located at 70° 40 north and 360° east in astronomical coordinates ().

Jimma town comprises 17 kebeles (a small administrative unit in Jimma). However, in this study, the researchers dealt with just two of the 17 kebeles in the city. The reason for choosing these two kebeles is primarily based on the intensity of the vulnerability of the areas to livelihood insecurity and the relatively significant number of FHHs exposed to poverty and livelihood insecurity. Given this, therefore, two kebeles, Mentina Kebele, who comprises 236 FHHSs out of 2,105 households, and Ginjo Kebele, which comprises 241 FHHs out of 2533 households, were taken as sample kebeles for this study. The Kebeles were also purposively selected based on recommendations given by the kebeles for women’s and children’s affairs of Jimma City to consider the magnitude, severity, and intensity of the urban problems in selected areas.

3.2. Study design

This study used a qualitative approach. The study adheres to a constructivist’s philosophical orientation toward the qualitative case study in terms of philosophical orientation. However, the researchers employed a phenomenological research design. According to Groenewald (Citation2004), the phenomenological study design describes specific people’s conscious and lived experiences by studying time, place, and personal history to grasp social reality. With this in mind, data for the study was obtained from carefully selected participants in the study regions between March and July 2019. However, this study used a phenomenological study design to look at female-headed families’ vulnerability and livelihood assets in Jimma’s two kebeles. Besides, this study employed this study design to explore how the female-headed households in the study areas cope with the given environment and what their livelihood looks like and assess the outcome of their livelihood. While investigating this study, the researchers adhered to the sustainable livelihood approach depicted in Figure .

3.3. Participants and samplings

The town of Jimma is found in southwestern Ethiopia and is in the province of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. The town of Jimma comprised 17 kebeles.

The researchers used a qualitative approach. However, a purposive (judgmental) sampling method was used to select the study participants. This study used a purposive sampling strategy to avoid the subway biases toward a single Kebele in one of the study areas. However, this study purposefully selects the two kebeles (Mentina and Ginjo Kebeles) based on the intensity of vulnerability of the areas to livelihood insecurity and the relatively significant number of FHHs exposed to poverty livelihood insecurity. This study, purposively based on the desire of the researchers, chooses 30 female-headed households (see, Table ) from the two kebeles, conducts two focus group discussions, and includes five key informants to gain richer and more detailed information regarding the extent of existing government policies and strategies considering the problem of urban FHHs. As a result, sampling criteria were created for residents and government personnel. Residents were chosen based on the following criteria: having lived in the study areas for at least five years, owning a Kebele, private, or rented housing unit, and having at least one child. Furthermore, as a household inclusion criterion, this study solely included female-headed families. The criteria for selecting government officials were working in the region for at least a year and holding a closely relevant position to the study’s subject matter.

Table 1. In-depth interview of participants from Ginjo Kebele (March 12-May-7, 2019

Table 2. In-depth interview participants from Mentina kebele (May 10–19 July 2019)

3.4. Data collection instruments and procedure

This study was approved and reviewed by the Jimma University research center in collaboration with Wolkite University, Ethiopia. Before collecting the necessary data for the study-specific objectives, the researchers provided informed consent to the female-headed household participants and managerial bodies in the study areas, written by Wolkite University, Department of Sociology. However, after we obtained their willingness based on the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. The participants were asked about their willingness to participate and provide the necessary information for the study. To promote data validity and reliability, the researchers briefly explained the study’s overall purpose.

To ensure ethical issues and participant confidentiality, the researchers informed the participants that they had the full right to decline or accept participation in the study and reveal the anticipated information. The researchers also provided them with an informed consent form for those who could write and read it aloud to the participants to get their permission. After that, they have signed or agreed to participate to ensure the issue’s confidentiality.

The study data were collected during the study period of March–to July 2019. This study used in-depth interviews, focus-group discussions, and key-informant interviews as a means of data collection and saturation of data. An in-depth interview was held with participants who were explicitly chosen from the study areas, which the researcher designed for the female heads of households. In this study, therefore, in-depth interviews were employed to reveal and uncover respondents’ real experiences related to livelihood strategies that households adapt to sustain the livelihood of the household, their daily life experiences, challenges they face concerning their livelihood situation, and the coping strategies they pursue to withstand livelihood stress and shocks. The researchers prepared an open-ended questionnaire for the in-depth interview that included double-barrelled questions (Bryman, Citation2016). This was an interview question guide that the authors created. These interview guides enabled the participants to know the purpose and content of the interview questions on which the study concentrated.

Furthermore, each participant in the study received a 45-minute face-to-face interview, which was labeled as the standardized duration when conducting an interview. Data were collected using a tape recorder and note-taking (Ladner, Citation2017).

The focus group discussion was another form of data collection used in this study. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria depicted in this study, the researchers have conducted two focus group discussions that comprised eight participants each. To avoid the degree of influence of some group members on the other participants, the focus group was made relatively homogenous based on key characteristics such as age, level of education, socio-economic status, and the participants’ degree of intimacy with one another.

Consequently, two focus group discussions (one FGD for each kebele) were mainly conducted to collect information on the community’s attitude toward the FHHs and their members. In social research, there are diverse types of focus group discussions. On the other hand, the researchers employed two-way focus group discussions in this study. It comprised two groups, one of which remained to discuss, while the other was observed and listened to by the first group until they were through (O Nyumba et al., Citation2018). Hearing the opinions of the other group (or observing their interactions) inevitably leads the second group to conclusions that it would not have reached otherwise, which is why this type of focus group discussion was used (Birt et al., Citation2016). As a strategy, the researchers chose a specific topic for the discussion based on the themes of the study, and then the focus group questionnaire was prepared. After that, a note-taker was appointed. After doing this, the researcher recruited and scheduled participants for the discussion and grouped them into two parts. Participants were asked to indicate their willingness before being asked about the focus group questions. After getting their permission, they introduced themselves, and the discussion began with the questions raised by the questionnaires. Concerning the duration, most social science researchers recommend having 45–90 min for FGD. However, the researchers had a 45-minute duration for each focus group discussion with the discussants in this study. Note that the participants in the interviews were also used in the focus group discussion sessions.

Key informant interviews were also conducted in this study to gain more affluent and more detailed information about the subject of the study. Key informants capable of providing richer and more detailed information, like officials from women’s and children’s affairs at the city level and the Kebele administration selected based on their position, willingness, and role in the community. Accordingly, five key informants were chosen purposely to gain more prosperous and more detailed information regarding the extent to which the existing government policies and strategies consider the problem of urban FHHs.

3.5. Data analysis

The researchers in this study used qualitative or thematic analysis. Data from the in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and key-informant interviews were manually analyzed in five steps. First, the researchers become familiar with the raw data. In other words, the researchers translate and transcribe the local language data into an English term by reading and re-reading the data. Second, the researchers have started coding the transcribed data. Initial codes have been assigned systematically to each piece of data from the respondents by keeping the stated specific objectives stated in the study in mind. Third, the researchers extract the codes and arrange them through the particular themes according to the sustainable livelihood approach shown in Figure . The researchers tried to think out the linkage between the assigned codes and the degree of themes in the study. In the fourth stage, rearranging and checking the study themes and sub-themes were completed within the fifth stage, the data report writing. The fifth stage comprises writing the results and the discussion section of the study. In the result sections, the researchers explicitly narrate the facts about the study objectives based on the data gained from the participants. In the discussion section, the researchers triangulate the results with the other studies to ensure their reliability and data compliance.

4. Results

The result of this study was analyzed in line with the specific objectives and sustainable livelihood approach diagrams shown in Figure . Accordingly, this study has included 30 female-headed households in the study areas (Mentina and Ginjo Kebeles) for in-depth interviews, two focus group discussions, and five key informants. As a result, the study findings were consistent with the specific objectives, which were classified into two parts: (1) vulnerability and livelihood assets of female-headed families; and (2) livelihood methods and livelihood outcomes of female-headed households.

4.1. Vulnerability and assets

This section explores access to different livelihood assets of FHHs to make a living in the study area based on the SLA (sustainable livelihood approach) presented in . The conceptual framework asserts that human capital, physical capital, and social capital are very crucial assets for urban people to make a living in urban settings. In this study, therefore, an attempt was made to identify and explore respondents’ access to human capital (which mainly comprises access to education, employment, health, and proper nutrition), financial capital (that includes access to credit, remittances, and savings), physical capital (mainly by exploring access to infrastructures, land, and houses), and social capital.

4.2. Human capital

One of the essential factors strongly influencing the livelihoods of households, improving their status as human capital and decreasing their probability of falling into poverty, is the educational level of the household head and its members. Given the high competition in the job market in urban areas, individuals with low education have limited chances of getting formal employment in better jobs. Hence, engaging in low-paid activities and informal sectors are the only existing options. Many studies indicate that education improves knowledge and skills, which are essential for getting better employment opportunities and generating self-effacing income and livelihood security. The study’s findings from in-depth interviews with participants Gi-1, Gi-9, and Mi-1 revealed that because female heads of households have low educational attainment and employment access, most of them fall into low-income groups, making their livelihoods insecure. As per key informant 1, household poverty and inability to send children to school are also taken as a reason for the low level of women’s educational background, which in turn produces an intergenerational transmission of disadvantage and poverty trap in respect of access to different services and opportunities like education, food, housing, health, and employment.

Access to health and nutrition is another determinant of human capital. Inadequate food intake in terms of quantity and quality affects people’s health in poor living conditions. People who eat whole foods rich in nutrients enjoy vital health, a longer life, and a reduced risk of many diseases.

In contrast, people who do not obtain proper nutrition have a healthy life, which in turn affects their ability to sustain their livelihood (Su et al., Citation2021). In the study areas, FHHs and their members were in a much more difficult position to provide the family with proper nutrition, medicine, and necessary goods and services because their expenditure tends to be restricted to cheap food for survival. By thanking and expressing her great gratitude for the residents’ administrative and neighborly support, one of the female head focus group discussants, Ginjo Kebele, narrates her daughter’s recovery as follows:

A fire accident happened to one of my daughters when I was baking enjera (a flat pancake-like bread commonly made of locally grown grain called teff) at my home. It was at the time when she was 7 years old. I then went outside when one of my neighbors called me. When I returned to the room baking enjera, I found my daughter inside the fire the enjera pan (made of mud) was broken because she fell on top of it. At the time, I was without any money on hand. I disapproved and blamed being poor. I thought that she was to die … Later, thanks to Ginjo kebele residents, they saved my daughter’s life. (FGD # 1)

4.3. Financial capital

In SLA (Sustainable livelihood approach), financial capital involves liquid assets in cash, credit or debit, savings, and other economic assets that enable one to make ends meet in the pursuit of a livelihood (Yirga, Citation2021). There are two possibilities for obtaining credit access among female-headed households in the study areas or the two kebeles concerning the study areas. One is informally getting credit from their community members, and the other is getting a loan through formal microfinance institutions.

Nonetheless, very few respondents borrowed money from microfinance institutions and community members. The fear of debt was a significant constraint for most of the female household heads in this study in accessing loans for bettering their livelihoods. They fear debt because their economic capability is too low to repay it, and they choose to live with their difficulties rather than becoming indebted. Supporting the above information, one of the FHHs interviewed confirmed

How is borrowing thinkable in a place where washing clothes and selling charcoal are chosen as the primary livelihood strategy? From the very beginning, I could not care to pay the money back, mainly because of the frequency of repayment schedules and the loan interest rate. Besides, our kebele administrative doesn’t allow us to borrow money because they perceive we couldn’t pay it back. (Gi-3)

Additionally, key informants 2 asserts that the rigidity of the deadlines for repaying the loans, the frequency of repayment schedules, and the high-interest rate are among the obstacles to credit access for FHHs in study areas. Loan terms for microfinance in Jimma town range from 3 years (36 months) to 5 years (60 months). Most microfinance institutions charge a 10% interest rate per annum on their loan amounts to cover their operational costs. Thus, the lack of access to credit opportunities also worsened the livelihoods of FHHs in the study areas. As a recommendation, they say that the government’s lack of trust should be solved by its residents.

The second option for the communities to get credit access is iqub (a traditional saving mechanism in Ethiopia). Those female-headed households whose monthly or weekly income is more significant than their monthly expenditure could have the chance to save extra money from their expense. Accordingly, one of the focus group discussants (FGD # 2) confirmed that thinking about savings is impossible in a place where your income can hardly cover your daily survival needs.

Moreover, most of the monthly budget is spent on food, followed by house rent. It shows how the livelihoods of FHHs are deteriorating because it is too difficult to live without any money at hand in urban areas (for instance, if they and their children get sick, money is needed).

Even though iqub is a fundamental source of financial stability, this study found that membership of iqub for female household heads is weak due to a lack of financial capability since iqub membership requires a monthly or weekly contribution of money that they cannot afford. Therefore most of the female household heads in study kebeles are non-members of the Iqub membership. In-depth interview participants Gi-4, Mi-5, and Gi-5 put lack of a regular financial base as the main reason:

To be a member of iqub, you must have a steady monthly or weekly income to put equal or proportional amounts of money aside per month or week. Of course, iqub improves one’s living conditions if you have a regular income.

4.4. Physical capital

Housing and related facilities are among the physical capital that can represent the living standards of urban dwellers. According to Ekanem et al. (Citation2014), housing is often one of the essential assets for the urban poor. It is used for both productive (renting rooms and running domestic businesses) and for reproductive purposes and shelter. Most female household heads do not have their own house in the study areas. Most of them, 60% of 30 participants, lived in rented homes belonging to the Kebeles, while the remaining 40% were occupants of rented private houses that were very cheap and lacked quality. Those who live in kebele houses pay rent to the kebele administration every month. As they revealed, most homes are made of mud and are small-sized with one or two rooms.

Moreover, the houses were dilapidated, which could not protect the residents from rain. Both the inside and outside of their home are in a horrible situation and are not hygienic ().

Figure 3. The dilapidated house of FHHs in Ginjo kebele is a single room used as a living room, bedroom, and kitchen. Own camera, 2019.

Furthermore, as one of the most critical infrastructures in urban areas, female-headed households were also asked if they had access to energy for cooking. Accordingly, Mi-6, Gi-10, and Mi-7 interview participants with female household heads show that many households use firewood for cooking food, including baking enjera, following kerosene.

In contrast, very few female household heads use electricity for cooking. Some of them collect firewood by going to the forest because they cannot afford to buy firewood. On average, women walk over 7 km in search of firewood. They travel to rural areas around the town of Jimma. This means that they spent about 14 km each way. Moreover, electricity is used as a light source for most household heads, even though some do not have it.

4.5. Social capital

Social capital refers to the norms, shared understandings, ties, trusts, and other factors that make collective action possible. Social networks and connections (patronage, neighborhoods, and kinship), relations of trust and mutual understanding and support, formal and informal groups, and shared values and behaviors (Nadjib, Citation2020). According to Su et al. (Citation2021), social capital may also be referred to as the shock absorbers that help poor people recover from adverse socio-economic situations. Social capital involves social networks, social relations, affiliations, and associations, among others. The accessibility of better social networks manifests itself in stronger ties in terms of kinship, neighborhood ties, formal and informal decision-making, and participation in informal organizations such as Iqub and Iddir (Ethiopian customary financial associations). Iddir is a social/cultural institution for both men and women and is responsible for arranging funeral ceremonies, while Iqub is the local traditional saving and credit association. Both iddir and iqub are social capital that helps people recover from adverse socio-economic situations. Access to these social capitals helps them share some of the livelihood facilities during hardship when a member gets sick or dies. In this study, therefore, attempts were made to look into two social capitals, namely, access to kinship ties and membership of iddir by participants and their impact on the livelihoods of FHHs.

Even though kinship ties play a substantial role in the livelihoods of female-headed households, these networks are getting weaker and weaker among the FHHs of study areas. Some FHHs do not even know their relatives and where they live.

Qualitative information from FGD with FHHs indicated why their kinship tie is weak:

No one wants you if you don’t have any money; even your family wants you if you’re educated and in a good position. I have two brothers who live a secure life here in Jimma town. But they don’t even ask when I get sick. I have been selling enjera for ten consecutive years, but none of them supported me and said to stop that work and start another better job. (FGD # 2)

As far as the iddir is concerned, it is a traditional form of community-based association. Iddir’s principal function is to take care of funeral services usually established among neighbors. Although iddir is a fundamental source of financial stability during the death of a household family member, this study found that membership in Iddir by female household head participants was significantly weak. Accordingly, in-depth interview participants Mi-8, Gi-11, and Mi-9 asserted that the main reason for weak membership participation is the lack of financial capability to fulfill the requirements necessary for the iddir association since iddir membership needs a monthly contribution of money, which they cannot afford. Also, access to formal and informal decisions was a concern in this study.

Even though the iddir is a fundamental source of financial stability during the death of a household family member, this study found that membership in iddir by female household heads is weak. Only 20% of the total participants were members of iddir in the selected study areas. The main reason for this is a lack of financial capability to fulfill the requirements necessary for the iddir association since iddir membership needs a monthly contribution of money, which they cannot afford. A monthly contribution of money for iddirs in the study areas was ETB 50 (1 dollar), which they cannot pay or afford.

Similarly, most of the female household heads in study kebeles are found to be non-members of iqub. Only 5% of the study participants were members of iddir in the selected study areas. As an in-depth interview revealed, the main reason for this was a lack of a regular financial base. To be a member of equb, there should be a minimum of weekly ETB 50 (1 dollar), which they cannot pay for or afford. An interview with FHHs revealed that their participation in leadership and decision-making positions is limited for various reasons, including a lack of educational background, a dual role inside and outside the home, and violence against them.

4.6. Challenges faced by FHHS

Disadvantages related to female household headship compromise the economic and material well-being of women and their children in these households and multiply other social, emotional, and psychological challenges. Although women-headed families are called upon to discharge their male counterparts’ entire social and economic functions, their social status remains marginal and peripheral (Ekanem et al., Citation2014).

This study revealed that household heads faced stigma and social discrimination from community members. They were discriminated against based on their gender and marital status. Married women who live with their husbands are seen as having a high status in the study kebeles. Women in male-headed households are more respected in the study areas than in female-headed families. For several reasons, those households that do not live with their husbands are treated negatively in their community. The widows were primarily blamed for the deaths of their husbands. This added to their stress, leaving them socially and emotionally unprepared to face the challenges of sustaining their livelihood. As in-depth interviews with female-headed households revealed single female household heads who have children without legal marriage were treated in society as deviants or out of the ordinary. It was assumed they might have had sexual contact with numerous partners’ men (Mi-14, Mi-11, and Mi-15). Women in male-headed households also fear that these women may have a sexual relationship with their husbands, and they always fight or feud with each other.

Furthermore, female-headed families are treated negatively because of their low living conditions and economic well-being in society. Due to their low living conditions, they have been discriminated against and gossiped about by their neighbors and community members. In support of this, one of the study participants, or female household head, stated her experience of weeping.

My husband left me alone when I was seven months pregnant. At the time, I had nothing to eat or drink. None of my relatives know where I live because I come from a rural area. I also didn’t want to go to my relatives because they might assume my baby was a child without a father and may also hate me. The only person I knew was my husband, and I didn’t know where he had gone. I had no option but to give birth independently without any support. After one month, I gave birth in a situation where nothing was available to eat or drink. Then, for up to five days, I breastfeed my baby only by drinking coffee. Five days after giving birth, I decided to participate in gulit (petty trading center or small marketplace that supports the livelihood of the poor) by selling fruits by closing the door on my baby. Once, all my neighbors and community members started gossiping and chuckling at me because I had participated in gulit for five days. Starting from that time, I decided to sell in gulit after midnight because I didn’t want anybody to distinguish me (Gi-15).

These and related challenges worsen the livelihood strategies of FHHs by making them feel isolated and discriminated against in their community, making them less likely to undertake their livelihood activities without any restraint. They don’t participate equally, economically, politically, and socially with those women in male-headed households because they are poor and deprived in society.

Because of her low living standards, remembering what her neighbors from male-headed families whispered, one of the focus group discussants narrates her experience:

Once, someone stole all the clothes and shoes in our neighborhood. People in our immediate surroundings suspected me since I am poor and have no quality clothes or shoes compared to others. They also assume she steals mangos at night when everyone is sleeping. But God knows everything, and he will judge. (Mi-13)

Moreover, many of the in-depth interview participants felt hopeless and lonely. Some of their reasons, among others, include lack of regular income to make a livelihood, lack of support from the government, lack of employment opportunities, lack of support from relatives, spouses, etc. Some of them also prefer death to the living. In support of this information, an in-depth interview with a participant household head was stated:

For two months, I was sick with typhoid fever. My kids asked me to provide food for them. Nothing was in my house to eat or drink. As a result, I told them that I was sick and had no money to buy food. Then, I cried alone since I didn’t want my children to see me weeping. Then, I prayed to God to take my miserable life because I didn’t want to see my children hungry. (Mi-1)

5. Livelihood coping strategies and activities of the FHHs

Understanding the livelihood strategies of FHHs requires an understanding of the means of livelihood and activities undertaken by households to generate a living. This section discusses livelihood strategies adopted by FHHs and the types of activities FHHs perform to earn income. Activities that families pursue change over time because of shifts in social factors, trends, and shocks that lead people to develop their survival strategies. They created another alternative activity. Key-informant study 3 of the study revealed that baking and selling enjera, selling local areke liquor and tella (home-brewed local alcohol for drinking), selling fruits and vegetables, domestic work, exchanging labor for food supplies, begging, selling used clothes, selling charcoal, baking and selling bread and tea, selling coffee and tea, selling raw corn on the street, and casual work was the livelihood activities female-headed households engaged in to make their lives better.

As data gathered through in-depth interviews and focus group discussion stated, the main reason for changing livelihood strategy is the urban informal economy (FGD # 1, Mi-2, 3, and 4). FHHs are almost always engaged in non-permanent, less-paid, and informal activities, mainly due to a lack of access to various opportunities. These also force them to rely on multiple livelihood strategies simultaneously. Research findings indicated that the female heads in the study area also sought labor engagements from wealthier or better-off families in exchange for food supplies. They were in the position of providing free service to well-off families so they could obtain food and raise their children. One of the in-depth interview participants stated her experience as follows:

I am a mother of two children. We are living here in one of the well-off households. They accepted me with my two kids because I agreed to give free service to be paid with food. I provide food for work, raise my children, eat, and just for survival. Before joining this household, I was a paid domestic worker in another house. I earned 250 birrs a month working in another place, and it didn’t even cover the expense of food and house rent. I then decided to give free service and raise my children because there was nobody for my children without me. Later on, I told a broker about my situation and asked him to find people who wanted domestic workers. Then, we agreed with them. I decided to serve them without payment if they took the responsibility of providing food to my children and me. They then gave us a mattress to sleep on in the kitchen. This is both the place where I prepare food and where I sleep at night with my children. (Mi-12)

In-depth interviews with FHHs also show that they face many challenges in undertaking their livelihood strategies. In-depth interview: Gi-6 household head describes her experience:

Baking and selling enjeras in gullit is my livelihood. In the morning, I go to collect firewood from the forest to bake enjera. I have no money to buy firewood because its cost is high. After collecting the wood, I bake enjera and take it to the gullit to sell. As you know, the price of teff is skyrocketing, and there is no such profit in this activity. For the sake of survival, I was just engaged in this activity to be able to raise my children.

Generally, female heads of households develop numerous livelihood activities that are, in most cases, informal, low-paid, irregular, or non-permanent for the sake of their survival and that of their dependent family members. Data obtained through in-depth interviews also show that begging is used as a livelihood activity for some female household heads. Concerning this, an interviewee noted her experience as follows:

My children begged for a long time after their father abandoned them and left me alone with them … I have no relatives that support my children and me as well … Then, I started begging just for survival because I had no money to start another job. (Gi-13)

Observing the livelihood situation of FHHs was heartbreaking. During begging, sometimes they do not even get any money all day. They simply stay in the street without eating any food, and their children are also vulnerable because they are unproductive and depend only on their mothers.

5.1. Livelihood outcomes

Although FHHs adopt diversified livelihood strategies, their living conditions and economic situations do not improve because they are mainly engaged in informal jobs like casual work and receive insufficient and irregular income. Formal education, which is essential for human capital, was not accessed by most FHHs, which hindered their access to formal employment that could lead to betterment in their livelihoods.

Their children are involved in several activities to support the family rather than earning an education and enjoying their childhood, leading to a vicious cycle of poverty among these households. These households also have limited access to assets to improve their lives. Besides, as indicated under the conceptual framework of this research, most of them still face a consumption gap with their current livelihoods being vulnerable to shocks and stresses. This and other related problems worsen the livelihood outcomes of FHHs, which in turn shows that there are growing patterns of livelihood insecurity. Hence, as indicated under the conceptual framework of the research, the outcomes of livelihood strategies can be either desirable or undesirable. Thus, poverty and livelihood insecurity are among the unwanted consequences. It reflects the SLA, whose general principle is that those who are not amply endowed with assets and resources are unable to make positive life choices and vice versa.

6. Institutions and organizations’ roles in transforming the livelihood of FHHs

Institutions are the rules of the game in a society or the humanly devised constraints that shape the livelihood outcomes of humans, whether politically, socially, or economically. Initiating and supporting women in general and FHHs, in particular, generating activities and decision-making is considered paramount for creating favorable conditions to help themselves and their members, which can help them generate better livelihood outcomes, which in turn plays a great role in promoting the economic growth of the country as a whole. Even though they are expected to make many efforts for themselves and the development of the country in economic, social, and political aspects, their lack access to different opportunities and resources, including education, credit, infrastructure, and participation in formal and informal institutions, lets them lag in every aspect and forces them to adopt slightly different informal livelihood strategies and income-earning activities. As a result, FHHs were asked to share their impressions of current governmental and non-governmental institutions to assist them in their attempts to improve their lives in Jimma City. Findings from the in-depth interview with the FHHs revealed that NGOs in the city were important institutions in supporting them. Key informants #4 and #5 with the two kebele administrations also showed similar responses to the in-depth interview participants G9-7, Gi-8, and Gi-12. According to the chairman of Mentina and Ginjo kebele administrations, non-governmental organizations support FHHs and other poor households or needy FHHs by providing different income-generating activities. Regarding the state institutions, they also stated that although the role of the government in supporting and making a conducive environment to engage in various livelihood activities for FHHs is minimal, some activities like providing houses for poor households, including FHHs, are offered by the government in the city.

Besides, since most of them live in the houses provided by kebeles, an interview with FHHs in both kebeles also revealed that governmental organizations support them by providing kebele houses, which are very cheap to afford. Generally, the role of both governmental and non-governmental institutions in supporting FHHs is minimal. They are trying to intervene in the problems of FHHs but are not holistically managing to eliminate their problems.

7. Discussion and conclusions

This research was conducted in Ginjo and Mentina kebele of Jimma City, south-west Ethiopia, with the prime intent of investigating the livelihood strategies of FHHs. Specifically, the study described female-headed households’ livelihood strategies, assessed the coping mechanisms adopted by FHHs to withstand urban livelihood insecurity, examined the livelihood assets used by FHHs, and found out the challenges FHHs are facing. The vulnerability and holdings of the FHHs in the study areas were assessed using perspectives from a sustainable livelihood approach. Sustainable livelihood approach perspectives include human capital, financial capital, physical capital, and social capital.

In terms of human capital, the findings of this study revealed that since female heads of households have low levels of educational attainment and employment access, most of them fall into the low-income groups, which in turn makes their livelihood insecure. In the same vein, Lambu’s (Citation2016) findings confirmed these study findings. They affirmed that as the level of education of the household head and its member’s increases, their living standards also increase. There is also an inverse relationship between the status of a household head’s education and the incidence of poverty. In addition, access to health and nutrition is also another determinant of human capital (Rata, Citation2016). Accordingly, in the study areas, FHHs and their members were in much worse condition to provide the family with proper nutrition, medicine, and necessary goods and services because their expenditure tends to be restricted to cheap foodstuffs for the sake of survival. The findings of this study are consistent with those findings of the survey conducted by Meron in that the health institutions commonly visited by the FHHs (reported as having access) are government health centers. In Ethiopia, better health facilities are provided in private health institutions than public ones. However, the poorer female-headed households cannot afford the price of private health clinics due to their financial instability (Kassa, Citation2013).

Concerning financial capital, this study found that participants in the study areas have two possibilities for accessing credit finance. One is informally getting credit from their community members (iqub), and the other is getting a loan through formal microfinance institutions. From the standard way of accessing credit liabilities, the fear of debt was a significant constraint for most of the female household heads in this study when accessing loans for bettering their livelihoods. They fear debt because their economic capability is too low to repay it, and they choose to live with their difficulties rather than becoming indebted. In the same vein, Debela (Citation2017) supports this study’s findings in the way that poor households are unable to benefit from such kinds of services due to a lack of required assets, and only a few relatively better-off male-headed families can get involved in such credit-giving institutions as they fulfill the necessary collateral. Accordingly, the rigidity of the deadlines for repaying the loans, the frequency of repayment schedules, and the high-interest rates are among the obstacles to credit access for FHHs in study areas. Alternatively, iqub is the second possibility and fundamental source of financial stability. This study, however, found that membership to iqub for female household heads is weak due to a lack of financial capability since iqub membership requires a monthly or weekly contribution of money, which they cannot afford.

Although people living in rural areas strongly depend on natural resources like land, forest, and water, the land is also a crucial asset in urban areas for making a sustainable living. Access and rights to land affect the type and quality of housing, and in urban areas, it is also a source of income by selling to run domestic businesses. However, findings from this study revealed that almost all female households in the study areas have no access to land. Concerning physical capital, most female household heads do not have their own house in the study areas. Most of them, 60% of 30 participants, lived in rented homes belonging to the Kebeles, while the remaining 40% were occupants of rented private homes that were very cheap and lacked quality. Those who live in kebele houses pay rent to the kebele administration every month. Kebele houses are owned by the local government and rented out to low-income earners. The Kebeles houses are tiny houses made mainly of mud and wood. The average rent for a Kebele house is almost 100 ETB ($2).

As they revealed, most of the places they lived in were made of mud and were small-sized with one or two rooms. Moreover, the houses were dilapidated, which could not protect the residents from rain. Both the inside and outside surroundings of their home are in a horrible situation and are not hygienic.

Moreover, concerning social capital, attempts were made to look into two social means, namely, access to kinship ties and membership of iddir (an informal group gathering to support each other at the funeral ceremony) by participants and their impact on the livelihoods of FHHs. However, this study found that although iddir is the fundamental source of financial stability during the death of a household family member, this study found that membership in iddir by female household heads is weak. The main reason for this is a lack of financial capability to fulfill the requirements necessary for the iddir association. The iddir membership needs a monthly contribution of money, which they cannot afford. Even though kinship ties play a substantial role in the livelihoods of female-headed households, these networks are getting weaker and weaker among the FHHs of study areas. Some FHHs do not even know their relatives and where they live. In the same vein, Sisay Mengesha (Citation2017) showed that financial insecurity is one of the major determining factors for the FHHs’ social relationships to become very weak. As a result, their neighbors and relatives are unable to contact them.

As per these study findings, the significant challenges faced by FHHs were stigma and social discrimination. Based on their gender and marital status, they are treated in hideous ways and isolated from participating in societal affairs such as iqub and iddir, and they are vulnerable to violence. The widowed and those living as FHHs were particularly blamed for the deaths of their husbands. This added to their stress, leaving them socially and emotionally unprepared to face the challenges of sustaining their livelihood.

Similarly, Woyesa and Kumar confirmed that female-headed households are treated negatively because of their low living conditions and economic well-being in society. Due to their poor living conditions, they have been discriminated against and gossiped about by their neighbors and community members. Although their living conditions are deplorable and their economic situation has not improved, their strategies to survive in this course of struggle are many and varied. The most common livelihood strategies they adopt, however, are casual work, selling fruits and vegetables, making and selling enjera, selling local liquor and Tella, collecting and selling firewood, selling charcoal, selling second-hand clothes, selling tea and coffee, washing clothes, and working in well-off households. In the same vein, Ekanem et al. (Citation2014) asserted that most FHHs in Nigeria do not have regular occupations or sources of income, and, as a result, they find other means of living. Securing financial capital is one of the most important undertakings by small businesses, and daily labor and paid domestic work are two of the most important ones. Finally, the findings of this study revealed that the state government (Jimma town) plays an enormous role in supporting female-headed households financially and by creating a conducive environment. However, the responsible bodies (the state government and Kebeles administrative) are negligent. They refuse to provide and orient houses for poor households, including FHHs, offered by the government in the city.

8. Recommendations and integration with Ethiopian women policy

The national Ethiopian women’s policy that was enacted in 1993 has mapped out the problems of Ethiopian women in all fields of development and identified the patriarchal system as the root cause that exposed women to political, economic, and social discrimination, which is reinforced by traditional practices that give credence to cultural norms and values over women’s human rights. The policy has emphasized women’s roles in household housekeeping, limiting their access to social services, public affairs, and property. It has been identified as an area that needs a concerted effort by all stakeholders.

Although the policy has placed the patriarchal system as the root cause that exposes women to political, economic, and social discrimination and encourages women’s participation in development, women’s access to and control of productive resources, information, training, education, employment, and decision making is limited. Based on these findings, the researchers recommend empowering FHHs to access credit services to begin better income-generating activities to change their living conditions. This could be a mitigation intervention to make women less vulnerable to economic challenges. As a result, local governmental and non-governmental organizations should facilitate training in income-generating activities and access to credit services for those with the motivation, desire, and capacity to run their businesses and various activities.

Although the Women’s Affairs Office and national policy entitle and ensure women’s right to property, gender empowerment in the country faces several major constraints. Among the challenges was the population’s lack of awareness of the roles played by women in the country’s development and deep-rooted cultural beliefs that reflect the values and beliefs of specific community members passed down from generation to generation, and traditional practices that prevent women from fully participating in the country’s development process. A lack of appropriate technology to reduce the workload of women at the household level.

Generally, there is a need for the national and regional governments to recognize the FHHs as vulnerable and disadvantaged categories in many aspects and therefore develop policies and design and implement projects that target FHHs.

Additionally, policies and strategies that increase access by the FHHs to productive resources need to be designed and implemented to empower them and widen their opportunities economically. It is mainly because FHHs cannot improve their living conditions unless timely and systematic development policies are implemented and concerned governmental and non-governmental institutions’ interventions are integrated for sustainable poverty reduction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Habtamu Wondimu

Habtamu Wondimu is a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Wolkite University, Ethiopia. He has published more than 15 papers in various international journals. His research interests include gender issues, vulnerability, child indicator research, and environmental challenges.

Wubit Delelegn

Wubit Delelegn is a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Wolkite University, Ethiopia. She has an M.A. degree in sociology and has engaged in various community services and reviewed several research papers at the university level. And her research interests focused on gender issues, rural sociology, and urban pathologies.

Kassahun Dejene

Kassahun Dejene is a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Wolkite University, Ethiopia. He obtained his M.A degree from the University of Debrecen, Hungary. His research interests relied on medical sociology and child indicator research.

References

- Andersson Djurfeldt, A., Djurfeldt, G., & Bergman Lodin, J. (2013). Geography of gender gaps: Regional patterns of income and farm–nonfarm interaction among male- and female-headed households in eight African countries. World Development, 48, 32–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.03.011

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member Checking. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Chávez Plazas, Y., & Bohórquez, M. C. (2015). Female headship and forced displacement: Reflections on family and citizenship. Prospective, 19(19), 125. https://doi.org/10.25100/prts.v0i19.969

- Debela, B. L. (2017). Factors affecting differences in livestock asset ownership between male- and female-headed households in Northern Ethiopia. The European Journal of Development Research, 29(2), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2016.9

- Devi, P., & D, A. K. V. S. S. R. (2020). Incidence of urban poverty in guntur municipal corporation of Andhra Pradesh- An empirical study. International Journal of Economics and Management Studies, 7(10), 109–112 https://doi.org/10.14445/23939125/IJEMS-V7I10P117.

- DFID. (1999) Sustainable livelihood guidance sheets. http://www.eldis.org/vfile/upload/1/document/0901/section2.pdf

- Ekanem, J. T., Nwachukwu, I., & Etuk, U. R. (2014). Impact of shell’s sustainable community development approach on the livelihood activities of community beneficiaries in the Niger Delta, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Society, 3(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.11634/216825851403583

- Fitzgerald, J. M., & Ribar, D. C. (2003). Transitions in welfare participation and female headship. SSRN Electronic Journal. 23(5), 641–670. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.459585

- Gecho, Y. (2014). Rural household livelihood strategies: options and determinants in the case of the wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia. Social Sciences, 3(3), 92 https://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/journal/paperinfo.aspx?journalid=202&doi=10.11648/j.ss.20140303.15.

- Gichure, J. N., Njeru, S. K., & Mathi, P. M. (2020). Sustainable livelihood approach for assessing the impacts of slaughterhouses on livelihood strategies among pastoralists in Kenya. Pastoralism, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-020-00184-z

- Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690400300104

- Joshi Rajkarnikar, P., & Ramnarain, S. (2019). Female headship and women’s work in Nepal. Feminist Economics, 26(2), 126–159 https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1689282.

- Kassa, Y. (2013). Determinants of adoption of improved maize varieties for male headed and female-headed households in west harerghe zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijebo.20130104.11

- LADNER, S. (2017 ()). Ethnographic research design. Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings 2017, 500 (edited by Elizabeth J. Chin). American Anthropological Association.

- Lambu, I. B. (2016). The cultural forces and women livelihood options in rural areas of Kano state, Nigeria. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 3(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.32.1852

- McClay, M., & Brown, M. (2000). Training for headship. Management in Education, 14(1), 22–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/089202060001400109

- Muleta, A., & Deressa, D. (2014). Female-headed households and poverty in rural Ethiopia. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 3(1), 152 https://doi.org/10.4314/star.v3i1.25.

- Nadjib, A. (2020). How social capital works: The role of social capital in acts of corruption. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(3), 2424–2433. https://doi.org/10.37200/IJPR/V24I3/PR201890

- O Nyumba, T., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., Mukherjee, N., & Geneletti, D. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12860

- Rata, M. Z. (2016). The Role of Livelihood Choices on Women Economic Empowerment, the Case of Kilte Awlaelo Woreda, Tigray Region, Ethiopia. International Journal of Management and Economics Invention, 2(1), 1–108 . https://doi.org/10.18535/ijmei/v2i1.01

- Sisay Mengesha, G. (2017). Food security status of peri-urban modern small scale irrigation project beneficiary female-headed households in Kobo Town, Ethiopia. Journal of Food Security, 5(6), 259–272 http://pubs.sciepub.com/jfs/5/6/6/index.html.

- Su, F., Song, N., Ma, N., Sultanaliev, A., Ma, J., Xue, B., & Fahad, S. (2021). An assessment of poverty alleviation measures and sustainable livelihood capability of farm households in Rural China: A sustainable livelihood approach. Agriculture, 11(12), 1230. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121230

- SUZUKI, K. (2021). Issues and perspectives of sustainable development and gender. Japanese Journal of Environmental Education, 31(3), 43–48 https://doi.org/10.5647/jsoee.31.3_43.

- Yirga, B. (2021). The livelihood of urban poor households: A sustainable livelihood approach in urbanizing Ethiopia. The case of Gondar City, Amhara National State. Poverty & Public Policy, 13(2), 155–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.306