Abstract

This article discusses the response of Muslim youth to the conception of a child through in-vitro fertilization. The pros and cons among young Muslims were carefully evaluated. Data that were collected through questionnaires, interviews, and document reviews constitutes the basis of this article. Questionnaires consisted of two types of questions: close-ended multiple-choice questions and open-ended narrative questions. Documents analyzed, meanwhile, included the legislative and fatwa products of the Indonesian Council of Ulamas as well as the decisions of the Tarjih Council of Muhammadiyah Central Leadership. This research found that the majority of respondents (85.7%) approved of the usage of in-vitro fertilization by legally married couples. Similarly, most respondents (73.7%) indicated that the use of in-vitro fertilization for conception, so long as it is conducted following applicable standards, did not violate any legal or ethical guidelines. This article emphasizes that young Muslims have diverse knowledge of in-vitro fertilization, which may be attributed to their particular fields of study. This research solely involved young Muslims. As such, future studies should use a broader sample, involving youths of diverse religious backgrounds, to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Having children through in-vitro fertilization is a method used by married couples who have special constraints. In-vitro fertilization is used by married couples who have problems with fertility as an alternative. In Muslim society, especially the younger generation, there are still pros and cons regarding the use of this method to have children. However, the conception of young people regarding the use of this method generally agrees that husband and wife are bound in a legal marriage. Likewise, they saw that there were no legal and ethical (Islamic) violations of the having children using the in-vitro fertilization method. In fact, young people consider it as part of the efforts of married couples to have children and to maintain their offspring in the future. This perception is also based on several products of law that are a reference, especially by in-vitro fertilization perpetrators.

1. Introduction

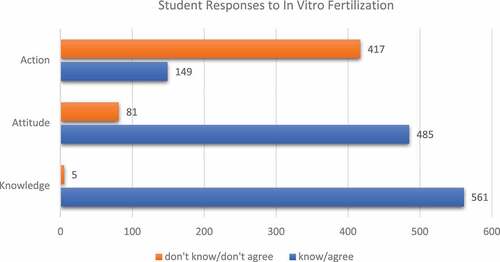

Young Muslims have diverse views regarding in-vitro fertilization. They see the process as highly beneficial, and thus it is morally, ethically, and medically acceptable for married couples seeking to conceive children. In a survey of 566 Muslim youths, 485 (85.7%) supported the usage of in-vitro fertilization by married couples; only 81 (14.3%) voiced disapproval of this practice. When asked about the legality of in-vitro fertilization, 417 respondents (73.7%) indicated that the practice did not violate any laws; 149 (26.3%), conversely, described it as legally problematic. This process is broadly perceived as being used by married couples who have difficulty conceiving, and thus as necessary for ensuring the continuation of the family’s bloodline (Rahmawati & Susilawati, Citation2018).

Studies of in-vitro fertilization have been conducted by many scholars. Such studies fall into three broad categories. First, studies that investigate in-vitro fertilization in terms of its process (Hidayat, Citation2014; Rizka, Citation2013). Before in-vitro fertilization occurs, it is necessary to ascertain the reason for infertility and the proper procedure for collecting deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA). Second, studies that investigate the legal implications of in-vitro fertilization for the children produced through the process (Komala, Citation2018; Yuliana & Saputra, Citation2019; Zahrowati, Citation2018), including in matters of inheritance. Third, studies of the experiences of children conceived through in-vitro fertilization, including in matters of representation during marriage, due to the involvement of surrogate mothers (Diani, Citation2020; Isnawan, Citation2019; Rahmawati & Susilawati, Citation2018; Zahrowati, Citation2018). Although such studies have investigated in-vitro fertilization as a process used by married couples to conceive children, they have failed to consider how the Muslim public has received and responded to it.

This article seeks to fill this gap in the literature by investigating how young Muslims view married couples’ use of in-vitro fertilization to conceive. What are the underlying reasons of their response towards the conception of a child through in-vitro fertilization. In so doing, this article explores three points. First, the legal discourses regarding in-vitro fertilization in Indonesia. Second, young Muslims’ understanding of in-vitro fertilization as practiced in Indonesian society. Third, young Muslims’ perception of the ethical and legal quandaries regarding in-vitro fertilization, which is associated closely with their religious and social knowledge. A discussion of these points will be presented below.

This article departs from the assumption that in-vitro fertilization involves numerous issues that are closely intertwined with recent legal and medical advances. In-vitro fertilization involves not only medical and health issues, but also ethical, moral, and legal ones. As such, the process must not be seen partially (using a singular perspective) but using diverse academic paradigms. The technological advances that facilitate Muslims in their everyday lives are not sufficient in and of themselves, as other sciences are necessary to minimize opposition to otherwise noble goals (such as conception).

2. Controversy regarding in-vitro fertilization

In-vitro fertilization has drawn the attention of scholars around the globe. Leite and Henriques (Citation2014) and Warzecha et al. (Citation2019) see in-vitro fertilization as an assisted reproduction technique (ART) that can be used to treat infertility, one similar to the freezing of oocyte (female gametocyte). In-vitro fertilization offers women with fertility issues the ability to conceive (Chelli et al., Citation2015). At the same time, however, it has certain inexorable gender, scientific, religious, and cultural implications. Cultural issues shape how in-vitro fertilization is perceived (Inhorn, Citation2003). In practice, three main factors are considered when deciding whether or not to use in-vitro fertilization: effectiveness, safety, and cost (Asplund, Citation2020; Asplund Citation2020; Stewart et al., Citation2013). Meanwhile, five factors determine the results of in-vitro fertilization: insurance, etiological determinism, type of infertility, duration of fertility treatment, and In-Vitro Fertilization–Embryo Transfer (IVF-ET) cycle (Jing et al., Citation2020). After in-vitro fertilization occurs, fertility quality of life significantly determines the extent of stigma (Jing et al., Citation2020). As such, Jing et al. (Citation2020) underscore the importance of providing psychological support to women experiencing infertility to reduce stigma and improve their quality of life.

When discussing in-vitro fertilization, it is important to note the complex interactions between scientific advances and the evolution of societal values (Asplund, Citation2020). As such, the process of in-vitro fertilization has been marked by moral and ethical conundrums (Leite & Henriques, Citation2014). Although in most countries the ethicality of in-vitro fertilization is no longer questioned, Asplund (Citation2020) notes that several issues are still being debated: maximum age, ownership of gametes and embryos, the use of in-vitro fertilization by single women and same-sex couples, preimplantation genetic diagnosis, social egg freezing, commercialization, public funding, and the prioritization of patients. Such debates are commonly politicized (Radkowska-Walkowicz, Citation2018), in part because the technology itself is not without risk. For example, ovarian tumors are more commonly diagnosed amongst women who have been involved in in-vitro fertilization, as shown by Stewart et al. (Citation2013). Although the use of fertility treatments may improve the immediate situation of women, it can have significant long-term consequences for their health and welfare (Lin, Citation2020).

Studies by Nicolas (Citation2021) and Chien (Citation2020) show that in-vitro fertilization remains taboo in society, and as a result, many Catholic leaders remain silent on the matter (Nicolas, Citation2021). Conversely, Islam permits and supports the study of human embryonic cells (Fadel, Citation2012). Permission depends on the usage of supernumerary early pre-embryos that are obtained by fertility clinics (Fadel, Citation2012). Careful investigation indicates that significant differences exist between people of different faiths. For example, comparing Sunni and Shiite Islam, the former wholly reject the involvement of third parties in reproductive assistance while the latter are more flexible (Chien, Citation2020). However, bioethical concerns remain strong, including in matters such as sperm donation (Chien, Citation2020). According to Islam et al. (Citation2013), Islamic ethics recognize in-vitro fertilization as being used for the greater good of humanity.

In many countries, religious considerations continue to influence the regulation and practice of in-vitro fertilization. (Asplund, Citation2020). A study conducted by Leite and Henriques (Citation2014) in Italy, Israel, and Egypt found that religious values heavily influenced these countries’ laws on in-vitro fertilization. At the same time, there are clear distinctions between different countries’ acceptance of particular ethical issues (Leite & Henriques, Citation2014). Culture, thus, also plays an important role in the formulation of regulations regarding in-vitro fertilization (Leite & Henriques, Citation2014). Italy, a majority-Christian nation, has imposed strict limitations on in-vitro fertilization and has thus drawn significant discussion and criticism from domestic and foreign scholars (Ragni et al. in Leite & Henriques, Citation2014). In Islam, meanwhile, religious courts have tended to support in-vitro fertilization as a fertility treatment. In Islamic jurisprudence, pre-embryonic cells are to be respected but do not have the same status as those that have been implanted in the uterus or experienced ensoulment (Fadel, Citation2012). According to Simpson (Citation2016), such “flexible” religious regulations can reduce conflict on controversial issues such as reproductive rights (including in-vitro fertilization) and promote the advancement of medical technology. In other words, the acceptance and practice of in-vitro fertilization are influenced by the flexibility of applicable regulations.

3. Method

This study was conducted at the Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta and focused on students’ responses to the use of in-vitro fertilization for conception. Data were collected through questionnaires, interviews, and a review of pertinent documents. Questionnaires were distributed to 566 respondents, who were disaggregated by gender, academic background, and faculty of origin. By gender, 344 respondents (60.8%) were women and 222 (39.1%) were men; all were between the ages of 18 and 24. By academic background, 386 (68.2%) came from public schools and 180 (31.8%) came from religious schools. Finally, by faculty, 158 (27.9%) were enrolled at the Faculty of Law, 176 (31.3%) were enrolled at the Faculty of Health and Medicine, 107 (18.9%) were enrolled at the Faculty of Islam, and 125 (22.1%) were enrolled at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences. Students from several faculties were contacted as in-vitro fertilization involves not only legal considerations, but also religious, political, and medical ones.

To ensure the collection of qualitative and quantitative data, questionnaires used both close-ended multiple-choice questions and open-ended narrative questions. To complement this data, in-depth interviews were conducted with eight informants, two from each faculty. Demographic information regarding these informants is presented in Table below.

Table 1. Demographic information

Informants were selected based on their faculty and educational background. For informants from the faculties of law, religion, and social sciences, questions focused on the permissibility and acceptability of married couples’ use of in-vitro fertilization for conception. Other questions involved related matters, such as the implications of in-vitro fertilization for children’s inheritance and social position. For students from the Faculty of Medicine, questions focused primarily on in-vitro fertilization’s effects on women’s health.

After being collected, these data were presented in narratives, tables, and charts. Data collected through observation were presented narratively, while data collected through interviews were presented as direct quotations. These data were subsequently analyzed using a progressive constructivist approach. This approach departs from the assumption that, as in-vitro fertilization is a multi-dimensional issue, a comprehensive understanding requires consideration of its religious, legal, medical, and social facets.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. In-vitro fertilization in brief

In-vitro fertilization refers to a process through which the ovum is inseminated outside the uterus, i.e., in a culture medium. After several days of embryo culture, the fertilized ovum or zygote is implanted in the womb (Ariantini et al., Citation2018; Sa’adah & Purnomo, Citation2017). In Indonesia, this practice has drawn significant debate, with proponents and opponents of in-vitro fertilization using dynamically evolving arguments. At the same time, it is regulated by the government through several pieces of legislation and by religious organizations through internal decrees. These are summarized in Table below.

Table 2. Regulations regarding in-vitro fertilization

As indicated by Table , in-vitro fertilization involves more than the health sector; it has particular legal, religious, and social facets. In essence, the technologies and processes used for in-vitro fertilization are permitted by state and Islamic law. Existing legislation recognizes that married couples may decide to pursue in-vitro fertilization when they are unable to conceive through natural means, be it due to endometriosis, oligospermia, unexplained infertility, or immunological factors (Sondakh, Citation2015).

Policies regarding in-vitro fertilization have evolved dynamically, adapting not only to advances in medical technology but also to ongoing religious debate (Dongoran, Citation2020; Hamdani, Citation2020; Isnawan, Citation2019; Zahrowati, Citation2018; Zubaidah, Citation1999). In Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation, this means that the reception and regulation of in-vitro fertilization have been inexorably intertwined with Islam and its exegesis. Likewise, the practice is regulated by both positive and religious laws. In terms of positive law, strict guidelines are provided through Regulation of the Minister of Health No. 43 of 2015 and Decision of the Minister of Health No. 72/Menkes/Per/II/1999. In terms of religious law, meanwhile, the fatwas of the Indonesian Council of Ulamas have provided guidelines for ensuring that in-vitro fertilization does not violate Islamic law and ethics.

In both positive (national) and Islamic law, safety, heredity, and happiness are identified as important considerations when determining whether or not in-vitro fertilization is permissible. Likewise, clear regulations exist to ensure that the process is conducted in an ethical, moral, and medically sound manner (Anwar, Citation2016; Isnawan, Citation2019; Rani Tiyas Budiyanti, Citation2015; Santoso, Citation2019). For example, under Indonesian law, in-vitro fertilization may only be used by married couples, as defined by their religion and by Law No. 1 of 1974 regarding Marriage. In-vitro fertilization, thus, must do more than conceive a child; it must do so in a legally and religiously appropriate manner (Halimah, Citation2018).

5.1 Students’ Knowledge of In-Vitro Fertilization

Students exhibited considerable knowledge of in-vitro fertilization, including the term itself, the process involved, and the legal status of children conceived through it. In the survey, 561 respondents (99.1%) answered that they “knew/recognized” the term; only 5 respondents (0.9%) indicated that they were unfamiliar with the term. Regarding married couples’ use of in-vitro fertilization for conception, 485 respondents (85.7%) approved; 81 respondents (14.3%) expressed disapproval. Responses regarding the legality of the practice were similarly divided; 149 respondents (26.3%) believed that in-vitro fertilization was illegal, while 417 respondents (73.7%) knew that in-vitro fertilization was permitted under positive and Islamic law so long as it was used by married couples to conceive. Respondents’ responses are summarized in Chart 1.

In Chart 1, it is clear that students were familiar with the term in-vitro fertilization, as almost all of them answered that they recognized it. Similarly, they generally responded positively to married couples’ use of in-vitro fertilization when they were unable to conceive using natural means. This is shown, for example, by the fact that 73.7% of respondents approved of in-vitro fertilization and did not doubt its legality.

At the same time, they recognized that in-vitro fertilization had significant legal implications, affecting not only the process of conception itself but also the future status of the children. Islamic law holds that anything achieved through a deviant process is inherently tainted; it is not only the results that matter but also the process through which these results are achieved. Consequently, there are strict criteria for the practice of in-vitro fertilization, including the aforementioned requirement that the man and woman involved be legally married. When children are conceived out of wedlock, this violates Islamic law (Diani, Citation2020), and this blemishes any children resulting from the union. There is thus a great need to ensure compliance with applicable law.

Respondents emphasized that in-vitro fertilization is not intended simply to facilitate conception; it is also intended to produce an heir and bring joy to the family. When respondents were asked about the benefits of in-vitro fertilization, they indicated that the process is used to continue the bloodline, ensure the family’s happiness, and maintain the honor of the married couple, per the teachings of Islam. However, these benefits can only be achieved and enjoyed when the process is conducted following positive and religious laws; it must, as noted previously, be used only by married couples and cannot involve surrogacy (which is prohibited under Islamic law; Rahmawati & Susilawati, Citation2018).

5.2 Students’ Perceptions regarding Conception and Status of Children

Students’ perspectives regarding the conception of children through in-vitro fertilization were not uniform. Most respondents (412, 72.79%) indicated that the use of in-vitro fertilization was permitted by (religious) law. They saw this process as facilitating married couples in producing an heir when natural approaches have been unsuccessful. Respondents who accepted in-vitro fertilization saw the process not as rejecting fate, but as striving toward a laudable goal—akin to how one must study diligently to receive good marks in school. For married couples who desire children, they argued, various means are available and appropriate. One informant, for example, stated:

“Human beings only strive to produce the offspring of their dreams; this is natural for any husband and wife” (Interview, R1, June 2021).

Another informant emphasized that in-vitro fertilization need not be perceived as rejecting one’s fate. He stated:

“ … because it’s just like any endeavor. They might try various things, like herbal and modern medicines. They might wait for years but never be blessed, and so in-vitro fertilization offers a solution, especially as the couple ages and becomes more vulnerable to health issues such as miscarriage during pregnancy. This does not go against God’s Will, so long as it follows appropriate health procedures and does not violate religious teachings” (Interview, R2, June 2021).

Another informant similarly emphasized fate, saying:

“In my opinion, when it comes to fate, some things can be changed, and some can’t. If God has willed a couple to have difficulty conceiving, I think that’s a fate that can be changed through hard work. If they can conceive a child this way, that is part of their struggle, and if God wills it … yeah, if God wills it, no matter what, their fate will change, and they will conceive a child through in-vitro fertilization” (Interview, R3, June 2021).

Another informant, R4, argued that in-vitro fertilization is essentially a God-given alternative for couples to conceive—with the assistance of a doctor. He argued that it was simply using a doctor’s services to realize one’s desire for offspring, saying “in-vitro fertilization doesn’t run against fate, as God offers the means through the doctor.” Such an approach offers couples the best means of maximizing their fertility and ensuring the continuation of their bloodline. Another informant stated,

“In-vitro fertilization is no problem, in so long as they use the ovum and sperm of a married husband and wife. This is their means of conceiving children, through in-vitro fertilization. It can be said to be their last hurrah in their quest to conceive” (Interview, R5, June 2021).

Informants also considered the ethical (religious) and medical aspects of the process. R6, for example, stated:

“ … because in-vitro fertilization helps those who want to conceive but have trouble doing so, and thus they use this method.” (Interview, R6, June 2021).

Another informant (R7) based her opinion on the decisions of other bodies, citing specifically a fatwa passed by one of Indonesia’s most prominent religious authorities: the Indonesian Council of Ulamas.

“In its fatwa, the Indonesian Council of Ulamas ruled that in-vitro fertilization, using the sperm and ovum of a married couple, is mubah (permitted), as this is an endeavor that complies with religious teachings and doctrines.” (Interview, R7, June 2021).

Based on these comments, it is evident that in-vitro fertilization has been perceived by informants as acceptable when used by married couples to conceive. This is particularly important when natural means fail, and thus couples must find alternative solutions. One informant, an aspiring midwife, stated:

“Women’s social status is often identified with their fertility, and thus failure to bear children is often deemed shameful and used as grounds for divorce.” (Interview, R8, July 2021).

This is supported by the literature, which shows that problems conceiving are often attributed to women’s fertility issues, even though impotence also plays a role. Between 1980 and 1985, the WHO Special Program of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction used 33 research centers in 25 countries (including 17 centers in developed nations) to investigate the causes of infertility. It found that fertility issues may be caused by the female partner, male partner, or both, and other issues cannot readily be explained.

In-vitro fertilization offers an alternative solution to couples who aspire to the noble goal of conceiving a child. In brief, students identified three reasons for accepting this process: couples’ intent to conceive a child and ensure the continuation of their bloodline, aspiring parents’ ongoing struggle that is blessed by God (i.e., permitted by religion) and supported by medical technology, and the legality of the process. R8 highlighted the health aspects of in-vitro fertilization when performed using the ovum and sperm cells of a married couple to conceive an heir. In brief, she argued:

“As someone heavily involved in in-vitro fertilization, of course, there is always a desire to help husbands and wives who want offspring, so long as the ovum and sperm cells aren’t taken from donors.” (Interview, R8, July 2021).

Meanwhile, 154 respondents (27.21%) opined that the use of in-vitro fertilization went “against fate”. Generally speaking, these respondents justified their opposition by referring to specific theological, sociological/political, and health considerations. These are presented in Table below.

Table 3. Reasons for rejecting in-vitro fertilization

As shown by Table , respondents made several points in justifying their opposition to in-vitro fertilization. The particular points made correlated with the respondents’ chosen major. For example, respondents who were enrolled at the Faculty of Islam were more likely to problematize in-vitro fertilization as going “against fate” and rejecting God’s will for a couple. Likewise, respondents who were enrolled at the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences were more likely to reject in-vitro fertilization due to its potential consequences for children conceived through the process. Finally, respondents enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine were more likely to highlight the medical risks of in-vitro fertilization, including the potential for a deadly ectopic pregnancy.

Even supporters of in-vitro fertilization noted the potential risks involved. For example, R8 stated,

“In-vitro fertilization can result in twins, premature births, low birth weights, hyperstimulation of the ovaries, ectopic pregnancy, birth defects, and even miscarriage.” (Interview, R8, July 2021).

In other words, the decision to turn to in-vitro fertilization may result in significant problems for couples (particularly women), even as they feel compelled to conceive a child and produce an heir.

From a legal perspective, the status of children conceived through in-vitro fertilization is not problematic, as such children enjoy the same legal rights as children conceived through natural means (Ramadhani et al., Citation2020). Under Indonesian law, the important point is the source of the reproductive cells used for conception. Conversely, in-vitro fertilization is not permitted when it involves a third party—for instance, a sperm donor or surrogate mother. Such distinctions are made in several legal products, including Regulation of the Minister of Health No. 43 of 2015 and Decision of the Minister of Health No. 72/Menkes/Per/II/1999.

From a medical perspective, meanwhile, the conception of children through in-vitro fertilization is permissible so long as certain standards are met (Doskočil, Citation2020; Halimah, Citation2018; Taebi et al., Citation2020). Rapid advances in reproductive technologies have made it increasingly simple for couples to use alternative means to conceive children. At the same time, however, there remain ethical considerations (Isnawan, Citation2019; Santoso, Citation2019). This can be seen, for example, in the argument that in-vitro fertilization is used to go “against fate” by seeking other means of realizing a sacred duty. It is therefore important for scholars of religion and medicine to establish dialogue and find a meeting point.

5. Conclusion

This article finds that young Muslims’ responses to the conception of children through in-vitro fertilization fall into two broad categories. Those who accept in-vitro fertilization perceive the process as part of couples’ struggle to produce an heir and bring joy to their families. Opponents, conversely, perceive in-vitro fertilization as an ethically flawed attempt to challenge God’s will. These responses need not be understood as intrinsically opposed; personal preference must also be considered. Indeed, for couples having difficulty conceiving through conventional means, the decision to turn to in-vitro fertilization does not pose an ethical dilemma.

In this context, medical and moral (religious) considerations should be understood as mutually complementary rather than diametrically opposed. Medically, for couples who cannot conceive through conventional means, in-vitro fertilization offers an acceptable alternative—albeit one with potential health consequences. Likewise, from an ethical/religious perspective, the benefits of conception far outweigh the risks. For many couples, conceiving a child through in-vitro fertilization represents the culmination of a lengthy struggle to produce an heir, and thus improve the happiness and welfare of the family.

This article’s analysis has relied solely on respondents with a shared religious and educational background. This sample is insufficient to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the issue. As such, future research should consider the perspectives of respondents from diverse religious and educational backgrounds. Likewise, this study has limited its scope solely to students of one university in Yogyakarta. Consequently, future research should draw its sample from a broader section of society. Only with a wealth of perspectives will generalization be possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahdiana Yuni Lestari

Ahdiana Yuni Lestari is a senior lecturer at faculty of law Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, she focuses on family law & Islamic inheritance studies.

Hasse Jubba

Hasse Jubba is a lecturer at Department of Islamic Politics Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, he focuses on minority group and Islamic political studies.

Siti Ismijati Jenie

Siti Ismijati Jenie is a professor at Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta and she focuses on private law studies.

Suparto Iribaram

Suparto Iribaram is lecturer and researcher on Institute Agama Islam Negeri Jayapura Papua, he focuses on community development studies especially in Papua.

Rabiatul Adawiah

Rabiatul Adawiah is teaching assistant in IA Scholars Foundation (IASF) Yogyakarta Indonesia.

References

- Anwar, S. (2016). Fertilisasi in vitro dalam tinjauan Maqāṣid Asy-syarī‘ah. Al-Ahwal: Jurnal Hukum Keluarga Islam, 9(2), 139–12. http://ejournal.uin-suka.ac.id/syariah/Ahwal/article/view/1201

- Ariantini, D., Lutfi, M., & Hadiati, D. R. (2018). Kadar Hormon LH Basal sebagai Prediktor Kebrhasilan Stimulasi Ovarium pada Program Bayi Tabung. Jurnal Kesehatan Reproduksi, 5(1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.22146/jkr.37988

- Asplund, K. (2020). Use of in vitro fertilization—ethical issues. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences, 125(2), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/03009734.2019.1684405

- Budiyanti, R. T. (2015). Aspek etika Pre-implantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD) pada teknologi bayi tabung. CDK: Cermin Dunia Kedokteran, 42(7), 1–3. http://www.cdkjournal.com/index.php/CDK/article/view/991

- Chelli, L., Riquet, S., Perrin, J., & Courbiere, B. (2015). Should we better inform young women about fertility? A state-of-knowledge study in a student population. Gynecologie Obstetrique Et Fertilite, 43(2), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gyobfe.2015.01.002

- Chien, S. (2020). Islamic beliefs on gamete donation: The impact on reproductive tourism in the Middle East and the United Kingdom. Clinical Ethics, 15(3), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477750920927175

- Diani, R. (2020). Legalitas penggunaan rahim ibu pengganti (surrogate mother) dalam program bayi tabung di Indonesia. Jurnal Hukum Tri Pantang, 6(2), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.51517/jhtp.v6i2.264

- Dongoran, I. (2020). Bayi Tabung dalam Tinjauan Hukum Islam (Analisis Maqashid Syari’ah). TAQNIN: Jurnal Syariah Dan Hukum, 2(1), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.30821/taqnin.v2i1.7604

- Doskočil, O. (2020). “Any surrogate mothers?” A debate on surrogacy in internet discussion forums. Human Affairs, 30(1), 10–26 https://doi.org/10.1515/humaff-2020-0002.

- Fadel, H. E. (2012). Developments in stem cell research and therapeutic cloning: Islamic ethical positions, a review. Bioethics, 26(3), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2010.01840.x

- Halimah, M. (2018). Pandangan Aksiologi terhadap Surrogate Mother. Jurnal Filsafat Indonesia, 1(2), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.23887/jfi.v1i2.13989

- Hamdani, M. F. (2020). Hukum Inseminasi Buatan dan Bayi Tabung. Al-Ahkam, 8(1), 107–119 http://repository.uinsu.ac.id/293/4/artikel.pdf.

- Hidayat, S. (2014). Seleksi dan tindakan medis istri sebelum program bayi tabung. Medica Hospitalia: Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2(1), 62–70. http://medicahospitalia.rskariadi.co.id/medicahospitalia/index.php/mh/article/view/94/82

- Inhorn, M. C. (2003). Local babies global science: Gender, religion, and in vitro fertilization in Egypt. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Islam, S., Rusli, B. N., & Hanapi, B. M. N. (2013). Ethical considerations on in vitro fertilization technologies in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Medical Science, 12(2), 121–128https://doi.org/10.3329/bjms.v12i2.14938.

- Isnawan, F. (2019). Pelaksanaan program inseminasi buatan bayi tabung menurut hukum Islam dan hukum positif Indonesia. Jurnal Fikri: Kajian Agama, Sosial & Budaya, 4(2), 179–199. https://journal.iaimnumetrolampung.ac.id/index.php/jf/article/view/558

- Jing, X., Gu, W., Xu, X., Yan, C., Jiao, P., Zhang, L., Li, X., Wang, X., & Wang, W. (2020). Stigma predicting fertility quality of life among Chinese infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2020.1778665

- Komala, N. (2018). Kewarisan anak hasil proses bayi tabung: Wasiat wajibah sebagai hak waris anak hasil surrogate mother ditinjau dari berbagai aspek hukum di Indonesia. Indonesian Journal of Islamic Law, 1(1), 65–81. http://jurnalpasca.iain-jember.ac.id/ejournal/index.php/IJIL/article/view/21

- Leite, T. H., & Henriques, R. A. D. H. (2014). Bioethics in assisted human reproduction: Influence of socio-economic and cultural aspects of the formulation of laws and reference guides factors in Brazil and other nations. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva, 24(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73312014000100003

- Lin, P. C. (2020). In vitro fertilization is safe for women undergoing the treatment after they deliver: A call to arms for the children, too! In Fertility and Sterility. Reflections, 133(3), 544–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.01.014

- Nicolas, P. (2021). In vitro fertilization: A pastoral taboo? Journal of Religion and Health, 60(3), 1694–1712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01161-x

- Radkowska-Walkowicz, M. (2018). How the political becomes private: in vitro fertilization and the catholic church in Poland. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(3), 979–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0480-3

- Rahmawati, N. A., & Susilawati, H. (2018). Fenomena surrogate mother (ibu pengganti) dalam perspektif Islam ditinjau dari hadis. NUANSA: Jurnal Penelitian Ilmu Sosial & Keagamaan Islam, 14(2), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.19105/nuansa.v14i2.1641

- Ramadhani, M. F., Septiandani, D., & Triasih, D. (2020). Status hukum keperdataan bayi tabung dan hubungan nasabnya ditinjau dari hukum Islam dan Kitab Undang-undang Hukum Perdata. Semarang Law Review (SLR), 1(1), 74–88. https://journals.usm.ac.id/index.php/slr/article/view/2350

- Rizka. (2013). Penggunaan Deoxyribo Nucleic Acid pada Proses Kloning Embrio Manusia dalam perspektif hukum Islam. Profetika: Jurnal Studi Islam, 14(2), 177–186. https://journals.ums.ac.id/index.php/profetika/article/view/2016

- Sa’adah, N., & Purnomo, W. (2017). Karakteristik dan Perilaku Berisiko Pasangan Infertil di Klinik Fertilitas dan Bayi Tabung Tiara Cita Rumah Sakit Putri Surabaya. Jurnal Biometrika & Kependudukan, 5(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.20473/jbk.v5i1.2016.61-69

- Santoso, B. (2019). Aspek etik pemilihan jenis kelamin dalam proses pre-implantation genetic diagnosis pada rekayasa reproduksi in vitro fertilitation. Aktualita: Jurnal Hukum, 2(2), 473–487. https://doi.org/10.29313/aktualita.v2i2.4986

- Simpson, B. (2016). IVF in Sri Lanka: A concise history of regulatory impasse. Reproductive Biomedicine and Society Online, Jun, 2, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2016.02.003

- Sondakh, H. R. (2015). Aspek Hukum Bayi Tabung di Indonesia. LEX Administratum, 3(1), 1–27 https://ejournal.unsrat.ac.id/index.php/administratum/article/view/7053.

- Stewart, L. M., Holman, C. D. A. J., Finn, J. C., Preen, D. B., & Hart, R. (2013). In vitro fertilization is associated with an increased risk of borderline ovarian tumours. Gynecologic Oncology, 129(2), 372–376 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.01.027.

- Taebi, M., Alavi, N., & Ahmadi, S. (2020). The experiences of surrogate mothers: A qualitative study. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 9(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.4103/nms.nms_19_19

- Warzecha, D., Szymusik, I., Pietrzak, B., Kosinska-Kaczynska, K., Sierdzinski, J., Sochacki-Wojcicka, N., & Wielgos, M. (2019). Sex education in Poland - A cross-sectional study evaluating over twenty thousand Polish women’s knowledge of reproductive health issues and contraceptive methods. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 689. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7046-0

- Yuliana, W. T., & Saputra, A. A. A. D. (2019). Analisa Hak Mewaris Bagi Anak Yang Lahir Melalui Proses Bayi Tabung Dalam Prespektif Hukum Perdata. Hukum Dan Masyarakat Madani, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.26623/humani.v9i1.1441

- Zahrowati, Z. (2018). Bayi Tabung (Fertilisasi In Vitro) Dengan Menggunakan Sperma Donor dan Rahim Sewaan (Surrogate Mother) dalam Perspektif Hukum Perdata. Halu Oleo Law Review, 1(2), 196–219. https://doi.org/10.33561/holrev.v1i2.3642

- Zubaidah, S. (1999). Bayi Tabung, Status Hukum dan Hubungan Nasabahnya dalam Perspektif Hukum Islam. Al-Mawarid: Journal of Islamic Law, 7(2), 45–55 https://www.neliti.com/id/publications/56905/bayi-tabung-status-hukum-dan-hubungan-nasabahnya-dalam-perspektif-hukum-islam#cite.