Abstract

This study explores the experiences of school going children who combine work and schooling in the Ekumfi-Narkwa fishing and farming community in the Central Region of Ghana. These children participate in works in their community as part of internalising their community’s norms and values, raise income and gain some skills to support their parents in a sustainable manner. The study employed a qualitative approach involving the use of in-depth interviews and participant/non-participant observations to elicit responses from the children. For these children, their tasks as fisher folks and farmers are regarded as purposeful for their everyday survival in their community. They consider the effort they put in their work as a way of reproducing inter-generational orders underpinned by strong ethical connotations. The children speak about how they gain their identities, self-esteem and skills through the work they do, the beneficial nature of the works they engage in and the ethical dimensions of engagement are emphasised. However, for their future, the children have dreams of other types of works that they think could be more fulfilling based on their level of education.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Most discourses on working children focus largely on the risks of children’s engagement in works, leading to measures that harm certain children’s development prospects. Appropriate works, rather than being generally bad in children’s life, add to their well-being and development, as well as their transition to adulthood. Children’s labour can provide advantages for survival and quality of life, provide learning to complement schooling, give psychosocial benefits, notably in the development of self-esteem, and assist in the development of social interactions and responsibility. For instance, children’s participation in work is considered very essential for their personal and communal sense of development. They internalise values and norms regarding work, enabling them support the development of their community. These benefits are especially important for children who are from marginalised communities. Common regulations that prohibit child labour based on age of work rather than potential damage deprive children of such benefits.

1. Introduction

Globally, the United Nations Organisation Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNOCRC) was established for protecting and securing children’s best interest anywhere in the world. The UNOCRC Article 3 (1,2,3) states that (1). “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”; (2). “States Parties undertake to ensure the child such protection and care as is necessary for his or her well-being, taking into account the rights and duties of his or her parents, legal guardians, or other individuals legally responsible for him or her, and, to this end, shall take all appropriate legislative and administrative measures.”; and (3). “States Parties shall ensure that the institutions, services and facilities responsible for the care or protection of children shall conform with the standards established by competent authorities, particularly in the areas of safety, health, in the number and suitability of their staff, as well as competent supervision.” These are in conformity with Ghana’s 1992 constitution (Article 28 (1e) and Ghana Children’s Act 1998 (Act 560) (Section 1). Furthermore, United Nations Children’s Funds (UNICEF) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) are some of the major global organisations that have continuously used legislative instruments as means of controlling the incidence of child labour in Ghana and other developing countries (Osei-Agyemang, Citation2020; UNICEF, Citation2020).

According to Afriyie et al. (Citation2019), participation of children in the workforce stands at 17%, 22% and 32% in Latin America, Asia and Africa respectively. Similarly, the ILO through its programme meant for eliminating child labour indicates that sub-Saharan Africa has the largest number of children between the ages of 5 to 17 participating in work (Osei-Agyemang, Citation2020). Ghana, as one of the countries in the sub-Sahara Africa, has an estimation of 13.7 million children engaging in work (Afriyie et al., Citation2019). According to the Ghana Statistical Service [GSS] (Citation2017) in the round 7 of the Ghana Living Standard Survey in 2017 about 28.8% children between the ages of 5 to 17 were in the labour market. In Ghana, there have been several governmental and international measures and policies aimed at ending child labour. These measures or interventions include the increasing of parental wages in order to increase the demand for schooling and decrease the supply of child labour. The aforementioned has created a context in which the situation of the right of children to work has become thorny and debatable and has also raised concerns about how schooling and work are related.

Most discourses surrounding child labour focus solely on the risks of children’s participation in work, leading to policies and measures that harm or impede the chances of some children to experience development (see, Aufseeser et al., Citation2018; Hoque, Citation2021; Human Rights Watch, Citation2021; Jijon, Citation2020; Sackey & Johannesen, Citation2015). Appropriate works/jobs, rather than being generally bad in children’s lives, add to their well-being and total development, as well as their transition to adulthood (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018). According to Jijon (Citation2020), children’s participation in work can help improve their quality of life and sustenance, provide learning to support and complement what they are taught at school, give psychosocial benefits, notably in the development of self-esteem, and assist them in being responsible and relating with others. The aforementioned benefits are especially important for children who are socio-economically marginalised. Hashim and Thorsen (Citation2011) argue that the consideration of education and work as being mutually exclusive has led to the designing of educational programmes with the aim of keeping working children out of any form of work. However, child-centred and contextualised surveys of the participation of children in work have demonstrated that the lives of children are extremely complex, diverse and dependent upon place and time (see, Bourdillon, Citation2017; Okyere, Citation2017). According to Ananga (Citation2013), contextualised study of children’s participation in work presents a nuanced understanding and conceptualisation of education and encourages broader and all-embracing implications of the position of school and work in the lives of children.

In recent times, localised studies (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018; Hoque, Citation2021; Human Rights Watch, Citation2021; Okyere, Citation2017; Osei-Agyemang, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2020) have shown that children experiencing marginalisation and deprivation benefit largely from working and thus it is a disservice to children and against their wellbeing to stop them from working at all because of school. Hashim and Thorsen (Citation2011) contend, therefore, that a child’s own concern and consideration indicate that work and schooling are not inherently oppositional but may represent distinct paths of education. However, Smith (Citation2020) cautions that allowing children to work comes with some degree of responsibilities on the part of adults in terms of ensuring that working children’s emotional and physical wellbeing is taken care of by their adult supervisors who have experience of working with children.

Ekumfi-Narkwa is a fishing and farming community in the Ekumfi District in the Central Region of Ghana. The socio-economic lives of the members of the community depend largely on natural resources. Farming and fishing thus represent the main occupations of the people. Nonetheless, members of the community engage in sewing, carving and other trading (trade in food crops, processed and unprocessed fish) as means of creating additional income sources. This study explores the perspectives of children in Ekumfi-Narkwa who live with their farmer and fisher folk parents, work and attend school regard their involvements in work and how they handle and manage their schooling and working lives. The study provides some clarity on work as a concept, as it considers what forms the nature of practices of work in the context of the study area. This study argues that, for the children of Ekumfi-Narkwa, works are neither just mere activities and they are also nor just important solely because of their economic importance. Instead, the works that these children engage in represent the organising principles of the children’s everyday lives and experiences as well as their socio-economic, socio-cultural and physical world in which they learn, socialise, grow and transition into adulthood (see, Hosny et al., Citation2020; Jijon, Citation2020; Sackey & Johannesen, Citation2015). The study highlights the children’s expression of their collective identities and the embodiment of their responsibilities as children, the meanings of shared practices among themselves and with members of their families and the community as a whole. However, for their future, the children have dreams of other types of works that they think could be more fulfilling based on their level of education. The findings reported in the study may provide a blueprint for Ghana’s ministries in charge of education and children to undertake a national study on children’s identity creation, schooling and work. The findings may provide data to the ministries and the Ghana Education Service for policy development and critical qualitative analysis regarding the holistic approach to working children and schooling as part of the pursuance of education for all.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: In the next section, the relevant related literature is presented, followed by a section that discusses the theories underpinning the study. The methods and approach deployed are also presented under the methodology section. The next section presents and discusses the results focusing on the children’s routinised daily practices, legitimation of the children’s participation in work, the values and norms of working and schooling and the policy implications. The final section presents the conclusion and recommendation.

2. Literature review

This section reviews the related literature to situate the issue of working children and schooling. The review covers the laws and policies on working children, sociocultural background of working children, the impacts of work among children and the theories that inform this study.

Laws and policies on working children in Ghana

The government of Ghana, over the last three decades, has passed, signed and formulated some laws, international agreements and policies with the sole aim of ensuring the prevention, elimination and regulation of all forms of children’s works that are detrimental to their total development (Imoh, Citation2019). Prominent among these is the Article 28 of the 1992 constitution of Ghana, which ensures the prohibition of children from participating in activities that are harmful to their education, health or total development, and establishes a framework for the making of laws and policies to achieve the elimination of child labour in Ghana. Similarly, the Children’s Act (1998, Act 560) was passed for the reformation and consolidation of legislation in relation to children with the aim of making provisions for the protection of children’s rights, child support, and adoption, as well as regulations governing apprenticeships and child labour. A child is defined by Section 1 of this Act as a boy or a girl below 18 years of age. This Act, in Section 87 (exploitative labour), prohibits the participation of children in works that negatively affect their education, health or total development. Section 91 of the Act also prohibits children from participating in works that affect their safety and morals (hazardous works). Section 88 of the Act ensures the prohibition of children from engaging in any form of works at night, from 8pm to 6am. Whereas Section 89 sets a minimum age of 15 years for a child to be employed, Section 90 sets a minimum age of 13 years for a child to engage in light works. Other forms of legislation that regulate children and their engagement in work are the Ghana Labour Act 2003, Juvenile Justice Act 2003, Education Act 2008 (Act 778), Human Trafficking Act 2005 (Act 694), Child Rights Regulation Instrument 2002 (LI 1705), and the Labour Regulations Instrument 2007 (LI 1833). Frimpong Boamah (Citation2018) observes that with the exception of the Ghana’s 1992 constitution, all the Acts relating to children rights and labour are shaped by neoliberal policies introduced by the IMF and the World Bank. Similarly, Lawrance (Citation2010) argues that debates, laws and policies surrounding children’s engagement in work in Ghana are all directed by agencies of the United Nation, international donors, Bretton Woods institutions and some international Non-Governmental Organisations.

Prominent among the policies meant for eliminating and preventing child labour in Ghana include Phase 1 of the National Plan of Actions against Child Labour (2009–2015) (NPA1). According to the Government of Ghana (Citation2009), the NPA 1 was Ghana’s first policy meant to systematically eliminate and prevent the prevalence of child labour in its worst or exploitative forms in Ghana. Its specific objectives were; ensure the continuous reviewing, updating and enforcement of laws surrounding children and socially mobilising for the protection of the rights of Ghanaian children; ensuring that the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education policy is fully implemented, especially in marginalised communities and ensure the enhancement of the path to post basic education for all children; empowering marginalised households and societies in overcoming vulnerabilities to child exploitations; establish institutional arrangement to help in identifying, rehabilitating, withdrawing and reintegrating children from any forms worst or exploitative child labour; make alternative arrangements for school dropouts to be educated; and introduce reforms in the labour market and new technologies with the aim of reducing the reliance on children’s labour (Yeboah, Citation2020). The next is the Phase 2 of the NPA 2 which started from 2017 to 2021. This was introduced to make up for the NPA 1 weaknesses and further strengthen the successes of the NPA 1 as the government of Ghana noted that the phase one underperformed leading to an increase in the prevalence rate of child labour in Ghana (Okyere et al., Citation2021). The NPA 2, therefore, targeted the reduction child labour drastically to about 10% by the year 2021 by laying institutional and policy foundations that are robust for a long-term prevention and elimination of all forms exploitative and hazardous child (Government of Ghana, Citation2017a).

The target of at least 10% represents the main difference between the NPA1 and the NPA2. According to Okyere et al. (Citation2021) the NPA2 had four main objectives; ensure the creation and reinforcement of public awareness and the strengthening of advocacy for effective policy programming and implementation of interventions specifically targeting children in Ghana; to increase capacities, collaborate, coordinate, and mobilise resources for the implementation of child labour intervention; to ensure that local government administrations effectively provide and oversee social services and economic empowerment programmes to parents; and to ensure the promotion of community empowerment and long-term solutions to the problem of child labour. Both NPA1 and 2 were a joint venture between external development partners and the government of Ghana. They were all “initiated, funded and given directed by external development partners.” (Okyere et al., Citation2021, p. 11). According to the Government of Ghana (Citation2017a), the NPA 2 was specifically undertaken with financial and technical supports from the Government of Canada, ILO, UNICEF and the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI). Notwithstanding the aforementioned objectives, whereas the Government of Government of Ghana (Citation2017a, p. 13) states in the policy document that “funding arrangements for the NPA2 would be given due attention”, no specific figures were made public even though the whole programme ended in 2021 (Okyere et al., Citation2021). Thus, like the NPA1, funds allocations to the NPA2 were not clear in the policy document.

The National Plan of Action for the Elimination of Human Trafficking in Ghana Statistical Service [GSS] (Citation2017–2021) is also one of the key policies against the trafficking of children. According to the Government of Ghana (Citation2017b), the plan addresses socio-economic challenges which predispose or make children vulnerable to child traffickers. The policy is also facilitated and funded by externally (UNICEF, Government of Canada). Another policy is the Declaration of Joint Action to Support the Implementation of the Harkin‐Engel Protocol (2010). This aimed at significantly reducing child labour in its worst and exploitative forms in the cocoa sector. The United States of America’s Department of Labour fully initiated and funded this programme in both Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire.

Sociocultural background of working children

Children in Ghana (then Gold Coast), traditionally, had been socialised through the process of acquiring and internalising competencies and skills from adults in relation to their communal way of life before the arrival of the British (Colonial master; Twum-Danso Imoh, Citation2012). Twum-Danso (Citation2009) recognises that children belonged to families, kinships and communities, and that an entire community bore the full responsibility for any child’s upkeep and upbringing. Different social, economic and political reforms were initiated following the emergence of the British in 1874 (Kilbride & Kilbride, 1990 as cited in Sackey & Johannesen, Citation2015). The changes brought about the monetisation of the economy of Ghana (from barter systems of trading to the use of cash). Valentine and Revson (1979 as cited in Stephen, Citation2020) argue that every member of families and households in Ghana had to make cash payments of head taxes. The trends of occupations that emerged from the economy of Ghana premised on fixed dates of payments using cash worked against the traditional practices of subsistence fishing, farming and kinships. This caused extended families and kinship relations to crumble and children were required to make contributions in relation to head tax payments, and thus children had no option but to participate in paid works (Lord, Citation2011).

According to Nukunya (Citation2003), the British ensured that formal education was introduced in Ghana and made sure that practices and values that were of European origin were applied while neglecting traditional or local knowledge (see also, Adzahlie-Mensah, Citation2014; Boakye-Boaten, Citation2012). That apart, globalisation has had influence on Ghana’s political economy and social systems that are important to children. For instance, the structural adjustment programme (SAP) that Ghana implemented in 1983 contributed largely to the Government of Ghana abolishing subsidies on formal education and thus leading to an increased socio-economic pressure on children pursuing education and their families who were financiers of children’s quest for formal education (Lord, Citation2011). Children in Ghana, however, are continuously growing and developing as members of families and local communities. In that sense, it has been argued that children’s membership to their families and communities guarantee them the fulfilment of their needs and that as members of their families and communities, they are obliged and expected to perform some specific duties (Twum-Danso, Citation2009; Twum-Danso Imoh, Citation2016). Children’s identities are also formed as they take up their duties and responsibilities, and interact with others in their families and communities (Imoh, Citation2019; Uprichard, Citation2008). The suggestion, here, is that the identities of children keep being mobile and shifting. Walkerdine (Citation1998) argues that children go through varied forms of childhoods and construct identities that are “shifting and mobile” depending on how they position themselves and are positioned by others (including their parents), abilities, gender, class and race. The identities the children experience take shape at early childhood as they strike interactions with their peers, parents and teachers. Thus, the identities of children shift in experiences and relationships but are not “fixed ways of being” (Kuby & Vaughn, Citation2015, p. 437). Uprichard (Citation2008, p. 303) problematises the ideas of “being” and “becoming”, when she states that the “being child is seen as a social actor actively constructing childhood, the becoming child is seen as an adult in the making, lacking the competencies of the adult that he or she will become.” Similarly, Dyson (Citation1997) focuses on the communicative activities and practices that children partake in and children’s construction of relationships via interactions to contextualise identities formation in children.

Impacts of working among children

Children grow up by emulating, and progressively contributing to, the activities going on around them, including works, in many parts of the world. According to Bourdillon (Citation2017), work is an inevitable aspect of life, and as children mature into responsible social beings, they become more involved. Children pay the price all too often when those in charge of policies and interventions are so focused on the perceived hazards of children’s participation in work. As a result, they overlook the benefits that children and their families derive from their works (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018; Okyere et al., Citation2021). Specifically, working children derive some economic benefits from working in most cultures. Most people understand the relevance of this economic benefit for people living in extreme poverty or in a serious crisis, where children’s labour is required for survival (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018). However, it is in these situations that work becomes excessive and frequently dangerous, and a working child’s agency becomes severely limited (Bourdillon, Citation2017). Thus, child labour becomes harmful which causes problems. According to Dammert et al. (Citation2018), aside relieving families of extreme poverty, allowing children to participate in work leads to the improvement of the lives of the children and that of their families. In examining poverty incidences, schooling and child labour, Aufseeser et al. (Citation2018) drew the conclusion that prominent among the determinants of child labour in Ghana are economic factors. Their study found that children’s works, particularly in family development programmes may make substantial impacts, and that it is not just about only survival. Bourdillon (Citation2017) argues in his work that children’s work, particularly in family development programmes, may make a substantial impact. He argues that children’s participation in work has increased as a result of sustainable development programmes such as microcredit and agricultural technologies, that have also led to increased working children. In the aforementioned situation, children’s works become a sign that the programmes are working and improving lives in these settings; nonetheless, the work can become burdensome and negatively affect their schooling (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018). According to Jijon (Citation2020), the dilemma here is how to allow working children to derive and maintain the benefits of participating in works without jeopardising their schooling. Nevertheless, this allows children to contribute to the growth of their communities while also developing their individual skills and abilities (Bourdillon et al., Citation2011). Even in affluent communities, children may profit financially from work, assist their households, and gain autonomy and become responsible (Bourdillon, Citation2017).

However, the evident economic rewards of works should not blind people to the fact that life is not only about money. Psychosocially, children take joy in what they accomplish when they effectively participate in the labour activities around them (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018). It has been observed when children, especially those who are marginalised, engage in work they end up boosting and fostering their morale, self-esteem and confidence. Work also helps in the provision of respite anytime there is tension at school or home (Jijon, Citation2020). In many communities or societies, participation of children in work is considered central in the establishment of relationships with the people surrounding them as this ensures the enhancement of cooperation and stability in communities and families (Helliwell et al., Citation2017). Thus, Bourdillon (Citation2017) argues that the elites may easily miss the possibility that interrupting children’s work can gravely harm children’s social relationships and total education, as well as the social fabric of society, because they are focused on individual growth.

Work has educational value, and, thus has the potential to boost children’s education. In accordance with Article 29 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), education involves schooling as a significant component, but it also goes beyond schooling to focus on the whole development of children’s skills, personalities, physical and mental capacities. With the above in mind, Aufseeser et al. (Citation2018) contend that work, rather than being in direct conflict with education, may and frequently contribute to education in its broadest meaning. Anthropological studies, in particular, have demonstrated the importance of child work in learning about the society in which the children are growing up and how they interact with others and their environment (see, Aufseeser, Citation2014; Bolin, Citation2006; Huberman, Citation2012). Aufseeser (Citation2014) working with street children in Peru found out how these children picked up some communicative skills and numeracy abilities which are very crucial for their lives as they transition from childhood to adulthood.

3. Theoretical underpinnings

Theoretically, participation, according to Sen (1999) as cited in Jacobson and Chang (Citation2019), has to do with the possibilities opened to people to freely be part of the making of decisions that affect their lives as part of the processes of human development. Sen’s (Citation2009) capability approach conceptualises participation as an aspect of capability set and ways of helping individuals to achieve their personal development. According to Clark (Citation2006), capability set has links with the options of functionings (that is, doing and acting) which have a relationship with how people use available opportunities. Making decisions are considered as activities that translate the concept of participation in its abstract form into an empirical reality. This offers the chances of observing the management of capabilities. Capability is also conceptualised as freedom to act and choose, and as human skills or talents (Soliman et al., Citation2022). For Sen (1999 p. 75) as cited in Jacobson and Chang (Citation2019), a distinction could be made between “well-being freedom” and “agency freedom”, with the latter suggesting a person’s capacity in exercising his or her will freely. According to Baradi and Lervese (2014, p. 45), children from this perspective lack “agency freedom” and their functionings are fundamentally regarded as very critical when determining the development of children’s capabilities in future. Saito (Citation2003, p. 26) observes that “when dealing with children, it is the freedom they will have in the future rather than the present that should be considered.” Biggeri and Karkara (Citation2014), however, argue that capability theory is an approach which is both opportunities-based and agency-oriented. Thus, the approach takes into consideration the aspirations and values of children and their societies through a bottom-up approach.

James (Citation2009) contends that the participation of children is in association with their agency in relation to their lives presently. Agency, to A., James and James (Citation2008, p. 9), means “the capacity of individuals to act independently.” Giddens (Citation1984) considers agency as courses of actions among different possibilities. Nevertheless, agency suggests not only a person’s competencies but also the social structures and relationships within which they find themselves (James, Citation2009). In line with Percy-Smith and Thomas (Citation2010), this study considers child participation as being part of decision-making and social relations that inform children’s routine practices. In this sense, agency is considered as the capabilities of the children to socially affect the context they find themselves and end up shaping their lives through participation. From this point of view, an insight is provided in relation to the complexities involved in children’s negotiation of their agency and interacting and talking about their participation in work and their routine daily practices. Among the core elements of this study is the exploration of the children’s formation of their identities within the social environment they find themselves. The study identifies their responsibilities as perceived and the values in accordance with Harre and Van Langenhove (Citation1999) expositions and thus undertakes an exploration of the enactment of the children of Ekumfi Narkwa’s relationship with each other as well as their elders.

Child participation in research is considered critical in Africa because children are considered central in studies that are about children (see, Adzahlie-Mensah, Citation2012; Pallay, Citation2014). Despite this, it is also argued that involving children in research in Africa could be very challenging because of the complexities and multiple ethical hurdles that must be cleared before, during and after the research. It is imperative to note that these challenges may not be totally different from those in Western contexts. Nevertheless, the different socio-cultural factors in African contexts might present very complex methodological and ethical issues. For instance, whereas individualism is well endorsed in Western contexts, the communal way of life is affirmed over individualism in African contexts (see also, Pallay, Citation2014). In an African context, this means, to obtain assent of children to participate in a study, the researchers may have to also obtain the consent of their parents, heads of households, community leaders, chiefs of their ethnic groups, among others. Methodologically, parents of children selected for a study may want to be present during interviews just as observers of the whole process. The presence of parents may present some ethical dilemmas to deal with. Notwithstanding the aforementioned, Africans do respect individualism as shown in Africans’ way of naming and initiating children and burying the dead.

4. Methodology

4.1. Study design

This study used a qualitative design to explore and understand the experiences of working school going children. Ontologically, I approached this study with the understanding that the children’s experiences with work are organised through social practices that included their representations, performances and talks. In this sense, the data were collected via sustained interactions as I immersed myself in their everyday activities whilst observing and interviewing them for their experiences and perspectives surrounding work. This design allowed the researcher to learn more about the experiences of working children in depth (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018).

4.2. Study site

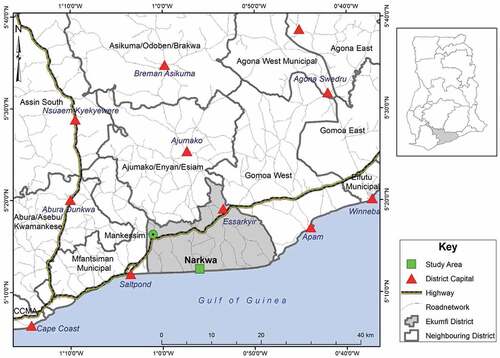

The Ekumfi-Narkwa community is a fishing community considered as one of the eight sub-district structures under the Ekumfi District in the Central Region of Ghana, as shown in . The total population of the district is 76,528, comprising 41,325 females and 35,203 males (Bukari et al., Citation2021). The main ethnic groups in the community are the Fanti, followed by the Ewe who migrated from the Volta Region to the community to be fish workers. Ekumfi-Narkwa was chosen for this study as a result of the popularity the community has gained through the production of pineapples for local consumption and export and their fishing activities. The pineapple planting and harvesting as well as fishing activities involve school-going children, making it imperative to deconstruct the complexities involved in rural children’s experiences on working and schooling at the same time.

4.3. Sampling population and sampling method

The sampling population were all the school going children in form three at the Junior High School (JHS) level in the Ekumfi-Narkwa community in the Central Region of Ghana. The researcher had no choice as a result of the insistence of the authorities of the schools to make available students in form three only as participants in the study. There are two JHSs in the community: the Methodist JHS and the District Assembly (DA) JHS. The number of form three students in the Methodist school was thirty-six and that of the DA was thirty. Twenty children (10 from each school) were involved in this study and the number of participants was determined by saturation point during the data collection process. The ages of these children range from 14 to 17 years, comprising 8 girls (4 from each school) and 12 boys (6 from each school). A non-probability sampling method; namely the convenience sampling technique was used to select the children for the study. A representative sample size was not a requirement, because the study was meant to ensure the provision of context-specific explanations surrounding children’s participation in work and schooling and how they get respected and internalise competencies via works in the Ekumfi-Narkwa community (Creswell, Citation2012; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018).

4.4. Recruitment of participants

The participants in this study were school-going children who were at the same time fish or farm workers in the community. The recruitments of the participants were done with the support, direction and consent of the authorities of the Junior High Schools (JHSs) in the community. The convenience sampling technique was used to select the children for the interviews. Using English as the language of the interviews, the interviews were conducted at school compounds, farmlands and seashore for an average period of 45 minutes for each interview.

4.5. Data collection procedure

The children’s perspectives were sought using informal conversations and in-depth interviews and participant/non-participant observations to collect primary data with an aim of developing a nuanced understanding of the existential dialogical meanings children assign to working and schooling at the same time. The data were collected through a process of sustained interactions which ensured a steady immersion and observation of the everyday lives and activities of the children with the intention of studying the complexities involved in how they relate with their age mates at the workplace and school. This was effected through a regular visitation to the shores, farms and schools. Even though their parents and teachers were talked to, the report writing was done mainly based on data collected from the children.

4.6. Data analysis and trustworthiness

In order to provide valuable and meaningful results, the data analysis was done in a methodical and rigorous manner (Nowell et al., Citation2017). The data analysis processes followed Green et al.’s (Citation2007) steps of data analysis; namely immersion, codification, categorisation, and identification of the themes. The steps were not followed linearly. The immersion step involved “lowering myself” deeply into the whole process of data collection during and after the collection. I repeatedly reflected and reviewed my field notes, reflexive journal, read and re-read transcripts and contextualised data. The recorded responses were played and listened to repeatedly focusing on any incoherencies and absences (Hollway & Jefferson, Citation2013). The immersion led to the reliving and witnessing of the details that formed the interviews and what was observed which includes, among others, the body language of the children as workers at the sea or on farms as well their attendance to school. This led to the developments of codes to represent the information that makes for easy tagging and sorting. The codification helped determining data that are to be excluded or included (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018). Codes that were related helped in the creation of categories which subsequently allowed for themes identifications. Themes (routinised practices, legitimate participation in work and norms and values of working and schooling) were developed to aid the writing processes.

I employed trustworthy thematic analysis by introducing credibility, dependability and confirmability in the study. To ensure credibility, I made sure that the children’s responses and my representation of these responses were the same. Additionally, I addressed credibility issues by prolonging my engagements with the children, observed them persistently as I triangulated my data collection procedures (observing and interviewing) (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018). I have had a thick description of all the data and methods used in this study for any other researchers interested in transferring its findings to a different site with the aim of judging transferability (Miles et al., Citation2014). To ensure dependability, all the processes involved in this study were documented logically and traceably (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2018). For confirmability, I ensured that my interpretation and findings were clearly obtained from the children’s responses by demonstrating how the interpretation and conclusions were reached (Miles et al., Citation2014; Nowell et al., Citation2017).

4.7. Ethical consideration

Ethical considerations were negotiated at every stage of the study in order that the children will not be considered as objects (Parkes, Citation2009). An ethical clearance or approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), University of Cape Coast, on the 15 March 2020. The Ekumfi District Education Directorate, parents and school administrators were considered as gatekeepers whose consent were negotiated for considering the institutionalised nature of children in school. The children were given information in respect of the researcher’s obligation to respect them, protection of anonymity and the need for confidentiality. Thus, the purpose of the study and the right to withdraw from the study or withdraw data was explained to them. They took part in the study after consenting verbally to be part of the study. The children were considered as active agents in making a choice of being part of the study or not to be. The names used in this study are all pseudonyms, not the real names of the participants.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Children’s routinised daily practices

The children’s routinised daily practices have to do with their everyday life which encompasses the doing of home chores, playing with siblings and friends, sharing of meal times, going to school, activities after school, among others. From Monday to Friday, every school-going child in Ekumfi-Narkwa goes through regimented and routinised practices in respect of households’ chores before leaving for school. When children wake up early in the morning, they are expected to complete some chores such as sweeping their compounds, collecting and dumping the refuse at a designated refuse dump, and fetching water from a well or standpipe that is nearby for themselves, their parents and other relatively younger siblings to bathe. These confirm Hosny et al. (Citation2020) observation that, in Africa, children assist with duties in both inside and outside of their homes in ways considered as very crucial in the whole process of socialising children, development of children’s character, and applications of socio-cultural values as they transition from childhood to adulthood.

After completing home chores, they dress up and set off for school, individually or usually in groups, walking for about five to fifteen minutes. Before they set off to school that commences at eight o’clock, their parents or elderly siblings prepare breakfasts in the form of rice with stew, porridge with bread, “kenkey” or “etew” (well-cooked corn dough balls) with grinded pepper and fried or cooked fish, and “ampesi” (boiled yam, cassava or plantain) which could be taken to school or eaten at home before leaving for school. The children could also be given money to buy food at school from food sellers permitted by the school authorities to sell to the children. At school, these children are taken through routine roll calls by their teachers to know who attended school that day or not. The children are given lessons in relation to subjects such as integrated science, music, mathematics, vocational and technical skills, Ghanaian language, and religious and moral education. When the school bells ring loudly for break time, some of the children rush out to buy some foods from the food sellers around their school or eat those they brought from home.

At break time, these children were allowed to engage in all sorts of temporal exercises or gaming activities such as running around, “tug-of-love” and football. Some of the games the children play are gendered in a way that they were meant for only girls. For instance, a game like “ampay” (a jumping game that also involves clapping and throwing of legs) is for girls only. Officially, in any school-going day, public schools end at 2:30pm and sometimes at 4:00 pm when the children are asked to stay in for extra classes. These extended classes were not compulsory. It was only meant for those whose parents could afford it. Some of the children complained of not being able to afford it even though they were willing to be part of such an arrangement. However, most of them stayed for the unofficial classes. Some of those who could stay for the classes and cited lack of finance as a reason made it clear that they had to leave and move straight to the farm to make some money. Some of the children avoided school in some particular days in order to work for some money to support their parents. One of the children (Darko) said,

There has always been the need for me and other friends of mine in this school to quickly move to the sea shore when we hear that the fishermen are in with some catch. This happens getting to the time school is about officially ending. We need the money to support our parents, you know.

Their teachers had mixed feelings and reactions when they were asked to comment on the attitudes of the children in regard to their running away from school to go working as fisher folks or farm hands. A teacher (Sir Lord) commented, “what can we do or say. Sometimes we put ourselves in their shoes in order to somewhat understand them.”

Nonetheless, when school ends for the day, most children in the community move straight into work. Those into working with pineapple farmers as well as those (mostly girls) into helping women cart their fishes to their sheds or where they processed fishes do so earnestly. Furthermore, the girls work for adult fisher folks as fish pickers, sorters, packers and smokers of fish. Most of them had other unpaid domestic works such as cooking and taking care of younger siblings. Some of the children, especially the boys, worked as canoe paddlers, draining of water from the canoes, worked as errand boys, pulled and threw nets, cooked for the elderly fisher folks, mended torn fishing nets, helped fuel outboard motors with fuel, and worked as load carriers. Most of the children were always found at the shore of the sea in the midst of the elderly fisher folks, sometimes resting, cooking and/or playing when they had no work to do. Children who worked on farm lands also took off for work when school closed for the day—even some left before closing of school. Most of the children (mostly the boys) worked on farmlands by removing and clearing bushes, stumps, roots among others from the lands meant for farming. These children were usually hired to clear the lands in preparation for the planting of various types of crops such as maize, oil palm plants, cassava, plantain and did also help in the planting of pineapples etc. They did also transplant seedlings and took care of nurseries. The children were also involved in the harvesting of crops and gathering of firewood, and were hired to take care of animals such as pigs, goats, sheep and fowls. They were mainly in charge of the transporting of the harvested crops to the market in the community and sometimes sold the produce themselves or by the owners. They harvested and sold coconuts, and these coconuts were mainly transported to the road side (on the Cape Coast-Accra road) for private and commercial car drivers and their passengers to buy. The girls were mainly baby-sitters, house helps, sometimes cooking and running errands for the elderly people in the community. Others also worked as paid apprentice in hair dressing saloons and seamstress shops, apart from helping in the hand picking of tomatoes, garden eggs, peppers and transporting and selling of farm produce at the market.

The children explained that they earned more in participating in fishing activities than farming because of the seasonal nature of farming. They claimed they could earn averagely “GHS 15.00 (2.6 USD) on a good day when at the sea shore” as said by Ekow, a 13 years old boy.

5.2. Legitimation of children’s participation in work

In African settings, the tradition or practice of involving children in household works from a younger age is popular. Children’s participation in work in Ekumfi-Narkwa is considered as an essential and critical part of children’s personal and communal sense of development. These children make comments that suggest that their participation in work is legitimatised in the community. Observations of the daily activities and the behaviours of the adults and how these adults relate with the children in the community gives substance to the legitimation of children’s participation in work, either as farmers or fisher folks. These children, through their participation in work, play a critical role in the community’s local economy. Participating in such a domestic economy gives the children the chances of discovering the accumulated knowledge of the community, work on their skills and learn to work in corporation with other members of the community in achieving goals of the community. This helps children in the communication of their feelings in ways that allow them to live peacefully with other members of the community as they work together at the sea shores or farms in the midst of adults (Jijon, Citation2020; Lanuza & Bandelj, Citation2015). To support the above, Kofi (16 years old boy) said,

Every man, woman, boy, girl work in this community. We are all into fishing and the processing of fish as well as farming. As boys, we don’t just go out there to only play, we go to work and make monies …

This comment agrees with the conceptualisation of capability as talents, human skill and the freedom to act and/or choose (see, Sen, Citation2009; Soliman et al., Citation2022). It is also in conformity with Sen’s (1999, as cited in Jacobson & Chang, Citation2019) distinction between “well-being freedom” and “agency freedom”, with the latter suggesting a person’s capacity in exercising his or her will freely. Furthermore, the children make comments that suggest that their close association with occupations that are traditionally done by their parents, elders and others members of the community give them the identity of being fisher folks and farmers. Thus, these children considered it to be fashionable and responsible to acquire indigenous skills and knowledge because that is exactly that gains them the respect and praise of their parents/adults as well as their peers. Work chores and rights to participate in work were equally important for the children, as shown by the way they spoke about work and the appreciation and respect they got for it.

These children explained that for them to be considered as intelligent children in the community, they need to display or demonstrate how responsible they are by working hard to help their families as they also attend school. This is in line with Ewusie et al.’s (Citation2017) argument that in Africa, an intelligent child is conceptualised as a child who blends cognitive alacrities with being socially responsible. Ewusie et al. (Citation2017) found in their study that children in Ghanaian societies’ show of a sense of being obliged to their parents, communities, siblings and friends is regarded as a very crucial to the process of any forms socialisation of children. The children also demonstrate this when they cooperate with other children, engage in responsible lifestyles, solving practical problems, and having confidence when approaching any form of work or assignment. They should also be able to display their capabilities and collective agencies in ways that their parents can rely on and believe in their abilities in responsibly performing or doing works given them as individuals or groups to support their communities. Apetiwa (14 years old girl) said,

My parents tell me I am clever when they give me work to do and I do it well and render accounts properly. When I come back from school I know it is for me to take up their work and do it properly and also show that I am in charge if I want them to give me tumps up and be respected by the community as a whole.

Buckman (16 years old boy) also said the following,

For me I know when I am pushed by my parents to work hard, they do not only want me to understand my own people, train me or help me to help them but also to help me grow into a better adult and help contribute to the community and Ghana.

Buckman's comment agrees with Nsamenang’s (2009) argument that in sub-Saharan Africa, involving children in work is not only to be construed as a socio-economic means of efficiently deploying human resources or socialising children but as a vehicle that allows the priming of a child who is developing to understand, recognise and rehearse her socio-economic roles which are anchored on four spheres of human life (the self, networks, households and public). This resonates with Serpell and Adamson-Holley’s (2017, p. 24) consideration of children as “social apprentices whose developmental progress requires adaptation to the demands of their family’s eco-cultural niche.” This also agrees with Saito’s (Citation2003) drawing on the capability theory to explain the extent to which children are brought up as a way of preparing them for their future rather than just their present. Saito (p. 26) argued that, “when dealing with children, it is the freedom they will have in the future rather than the present that should be considered.”

The children explained how, in doing their works, their little brothers and sisters (less than 6 years) force their ways through to also help in working even though their older children regard their assistance as nuisance. These little ones who were considered nuisance were also considered as playing legitimate roles in accordance with their capabilities. This agrees with Polak’s (Citation2012) observation in Mali that little children of the Bamana tribe are well integrated into the work life cycle of the tribe. Furthermore, this confirms Biggeri and Karkara (Citation2014) argument that capability as an approach is agency and opportunity oriented when dealing with children. It takes care of, through a bottom-up approach, both the values and aspirations of children and their communities. In this sense, it is argued that children’s participation in work maybe associated with their agency in relation to their lives presently (James, Citation2009).

This may also suggest that children in the community do not attain a particular age before they are allowed to help in works. For instance, during the carting or transportation of fishes in the community, these children below six years were seen helping to pack fishes in bowls and buckets even though they had not attained the skills and strength to do so. These children did that under the guide of their older brothers and sisters, and these were observed during weekends. They were also seen at farms helping their older siblings.

Children’s participation in works in the community was informal to the extent that they could not distinguish their fishing and farming works from the routine chores such as dishwashing, fetching of water, feeding and bathing their little siblings, and sweeping their compound. As these children grow and acquire some skills and competencies whilst developing enough physical strength, capabilities and mental fortitudes, they do not hesitate in broadening their participation in works. Furthermore, these children keep increasing in competence and skills till they begin to take up more challenging roles that demand some specialised skills.

With respect to the specific works that these children do at the sea shore and on the farm lands, the children are fully part of every activity done in the community in relation to fishing and farming. These children always performed roles that complemented the roles performed by the adult fisher folks. For instance, with regard to fishing, the children were always intensely engaging with the adult fisher folks regarding the cleaning of boats and canoes, scooping of water from canoes, mending torn fishing nets, dragging nets from the sea and the rolling or pushing of canoes into the sea. This observation conforms with Okyere et al.’s (Citation2021) argument that children perform works that complement works of adults and that they do not compete with the adults. For instance, on several occasions at the sea shore, children and adults were observed working together. On one of such occasions, about six children in the midst of eight adult fisher folks had finished eating together, after which they all moved towards a canoe which had been refurbished and painted with colours (Red, Yellow and Green) of the Ghanaian flag. Together, these adults and children pushed the canoe closer to the sea. The adults ordered three of the children to get onto the canoe with their paddles. The other children stood there for some time watching their other colleagues with the adults in the canoe signing and paddling the away into the sea for a fishing expedition. This suggests that the tasks performed by the children were not just copying what adults did. Rather, they complemented what the adults did.

On another occasion on a pineapple farm, four of the children were observed carrying water and pineapple suckers at one of the farms. Other children (4) also joined later on to get the work done. An adult asked two of the children to clear off some weed that had been left on the farm land for long. One of the children suggested to the adult that they would rather use them for mulching to help enrich the soil. As a researcher, I got closer to that child (13 years boy) and asked him how he learnt that idea of enriching the soil with decaying leaves. He explained that, “we have always been doing these with our parents and other adults at a very tender age.” This same boy said, “in this community we just join people working without being invited just to learn.”

The comment that they join others to work even when not invited to work suggests that these children do not just see themselves as labourers who are only working to be paid but also helping their community as members of their community (Boakye-Boaten, Citation2012; Okyere, Citation2017). This also conforms with Hashim and Thorsen’s (Citation2011) argument that in Africa, work forms part of children’s identities. The children also explained that their participation in work is legitimated and accepted by the way their parents encourage them to work hard and the extent to which they are encouraged by their teachers to work at school in respect of sweeping, cleaning and weeding their school compounds. Agartha (15 years old girl), for instance, said “Our parents always tell us to work hard as children, so that when we become adults we won’t feel lazy working.”

This comment agrees with Gunu (Citation2018) and Twum-Danso’s (Citation2009) observation that attitudes toward work in the lives of children have been maintained and legitimated by the ways adults relate with their children, and that this is also reflected in the expectations, responsibilities and duties of children even within educational institutions or systems. For instance, Moojiman et al. (Citation2013) highlight the education service of Ghana’s (GES) programme termed as WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) as listing children in Ghanaian basic schools as being in charge of their personal cleanliness and the general cleanliness of school compounds in Ghana. They further argue that when schools in Ghana are unable to recruit cleaners, heads of schools have the mandate of educational authority to direct the children to clean toilets and wash rooms, sweep and clean school compounds, put water in tanks for later use and do any other work that will help maintain cleanliness in the school as a whole. To give substance to the aforementioned, the GES (Citation2014, p. 6) makes it clear that “where school pupils are required to do the cleaning, a schedule must be prepared for both boys and girls to undertake the cleaning under the supervision of a teacher.” In some advanced countries, children’s participation in work is also legitimated. For example, according to Tsuneyoshi et al. (Citation2016), schools in Japan allow pupils to clean school compounds and facilities. Similarly, according to the Independent News and Media (2016), the Ministry of Education in Singapore announced in 2016 that school pupils in the country will be cleaning school facilities and compounds (canteens, toilets, classrooms and corridors) under the supervision of their teachers.

Most of the children also explained that they are able to go to school when they find more work to do and make more money. They made so many expressions as regards their happiness to be in school where they meet their colleagues whose experiences in life are just similar to theirs. They tell stories of how they are able to share stories of various ways of saving money for later use in life.

The children explained that they work to make money to help their parents pay for their education. They have the intention to continue with their education to the university level. Darko (14 years old boy), for instance, believes that he could work hard beyond the basic level to the university level to become a lawyer. This highlights the children’s agency in pursuing targets that they value and have the reasons to place values on (Mizen & Ofosu-Kusi, Citation2013). Similarly, it demonstrates what the children are efficiently and effectively capable of doing and how effective they can function considering all the resources put to their disposal as children (Sen, Citation2009). Furthermore, these children had a strong belief in the positive change in life circumstances as a result of formal education. Most of the children were very motivated to go beyond basic education to the university level not to only get a lucrative employment but also as a way of showing to others that they are responsible and well respected members of their community.

Nevertheless, two of the children made it clear that they might continue to work as farmers and fisher folks when they grow up. These two boys explained that even if they end up working as medical doctors, engineers, teachers or lawyers, their collective identities as fisher folks or farmers cannot be forgotten or be erased forever.

The children’s everyday conversation and activities in school and the community showed how the community as a whole regarded communal life and school life. Children who regularly and punctually attended school were considered as respectful and well behaved whilst those who were truant were considered as “bad boys.” Children who worked hard in the community were regarded as children with great future while those who were not hard working were seen as lazy and bad examples for other children. The children considered school as a place where they are thought good manners and how to relate with adults as well as their own colleagues. They explained that parents of children who work hard and attend school are well honoured and respected in the community. The children’s comments also suggest that when children are faced with expectations and responsibilities of participating in works, they end up gaining skills and internalising some values, making them feel capable and respectable (Twum-Danso, Citation2009).

5.3. Values and norms of working and schooling

There are no regulations and rules explicitly documented to guide children’s participation in farming and fishing. That said, implicitly, there were norms, standards and values that were drawn on to guide, direct and shape the activities of children in respect of their involvement in work in the community even though these were not somewhat visible and readily available to visitors. The value and norms of the community are usually instilled in children from “babyhood” through childhood to adulthood. For instance, from young age, children are taught to show respect to their elders. Children of the community might express or demonstrate their respects for the elderly by joining them to work or complete a task for the adults. Inferences of the existence of these norms and values are also made from the way the children were considered as farmers and fisher folks as well as the ways through which these children join in working for people in the community without being asked to work. Thus, these norms and values are embedded in the everyday life activities and practices of the children in the community.

The children’s explanations agree with the argument that in sub-Saharan Africa, socialising children and introducing them to norms and values of a community are done by the community as a whole (Badasu, Citation2004), not just by an individual. Similarly, Frimpong-Manso (Citation2014) contends that children are introduced to such norms and values at tender age in order for them to internalise them, and this communal way of bringing up children makes it possible and enables the provision of care and guidance to children. These suggest that the children have internalised the notion of intergenerational continuity of their community as shown in the comment “We are doing exactly what they did when they were like us.” This particular comment also suggests that these children are active social actors with agency who do not merely or passively depend on other people or easily be impeded by social structures (Abebe, Citation2019; Giddens, Citation1984). These comments are also in line with Ansah-Koi’s (Citation2006) observation that a sense of communal responsibilities and obligations are imparted in children with the intention of instilling values and norms of altruism, reciprocity and respect for elders and hard work in them. Thus, these children at tender age understood that they were expected to respect their elders and also make contributions, through hard work, to the proper functioning and development of their community (see, Yeboah, Citation2020). Similarly, the comments highlight the argument that children are humans who have the capacities and responsibilities to act independently for themselves and for others (Twum-Danso Imoh & Ansell, Citation2015).

Furthermore, despite the relaxing working environment the children found themselves in, they were aware that they were expected to demonstrate complete commitment and dedication to their work and school. The comments from the children suggest that this was critical for socialising children because as part of their tradition, families or parents whose children who have grown into adults but are unable to demonstrate some mastery or skills in any form of work are described as lazy adults or “useless persons.” This conforms with Takyi’s (Citation2014) argument that traditionally, children in Ghana are brought up and socialised to understand that they need some skills that they will use in future when they grow up to work effectively to earn more income to take care of their families and that their inability to imbibe and internalise those skills will render them ineffective adults. It similarly agrees with Nukunya’s (Citation2003) contention that children are equipped well with skills that will make them better adults and that socio-economic activities represent the main competencies and skills that children of Ghana are taught by their parents and other elders in their community. This points to A. James and Prout’s (Citation1997) view that children have the abilities and capabilities to engage in the construction and determination of their own socio-economic lives and affect the lives of other members of their communities. To give substance to the above, Martha (15 years old girl) said,

You are considered a lazy child if you run away from work. Sometimes our parents point at other adults and refer to them as useless persons because they were lazy children

My parents want me to show commitment to the work I do in order for me to get all the skills that will help me when I become an adult. I am shouted at or sometimes beaten when I refuse to commit to my work

Adult fisher folks and farmers in the community do not make formal arrangements and plans for children to engage in farming or fishing. However, the children considered their parents or any other adults they worked with as their leader or coordinator anytime they worked together. These children continuously listened to their leaders (parents and other adults) who they regarded as very experienced despite sometimes knowing what is required of them. One of the children, Aburansa (15 years old boy), said, “We are always instructed by our elders or parents even though we can work on our own if permitted with little or no supervision.” Sometimes, during work, leadership roles are played by different individuals just as the working team synchronise their activities in ways that might look like everything has been planned. The children, in some occasions, were allowed to play leadership roles depending on their level of mastery of the act of fishing or farming. For instance, at the sea shore, a group of four children and five adults were observed untying a canoe from a coconut tree to be pulled into the sea. One of the children led this exercise amidst the singing of a war song. He controlled and ordered the rest of the team members in way that led to the successful pushing of the canoe into the sea. Another child also led the dragging of a net filled with fish from the sea unto the sea shore. This observation indicates that the adults in the community recognise and respect the capabilities and agency of the children to be part of the decision-making that positively or negatively affects their lives, and that these form part of the rights accorded children that give impetus to the perspective that children are competent, active and subjects who have the agency to claim their rights (Kjørholt, Citation2005). However, Mizen and Ofosu-Kusi (Citation2013) and Hammersley (Citation2016) caution that there is the need to be careful of not viewing children’s agency as merely a way of exercising free wills against social structures and their challenges that they pose.

The values and norms at school were very formal, structured and totally different from what the children experienced at home and workplace as fisher folks and/or farmers. Schools in the community as well as other parts of Ghana operate hierarchically and, according to Alexander (Citation2000, p. 92), with rules that demonstrate power relations and “sustain authoritarian stress on conformity and obedience” on the part of the pupils. The head teachers are the highest in a ranking order, with the pupils being at the tail end of the order. The deputies to the heads are the assistant head teachers, and together with the other subject teachers, they exercise authority and control over the pupils. In the classrooms, the teachers place their chairs and tables right in front of the class, facing the pupils. This sitting arrangement allows the teachers to observe, direct and control the pupils’ behaviours. These teachers regulate classrooms by checking whether the pupils were in school or not, using a well-prepared register for each class. These registers are official documents which contain names of all the pupils in an alphabetical order for each class. The pupils in the classrooms were considered as subjects who were only to take in the instructions of the teachers and thus were not allowed to negotiate any responsibilities. The pupils only pitched in at the instruction and direction of their teachers and were not allowed to make contributions anytime they deemed fit. These arrangements highlight Foucault’s (Citation1995, p. 197) notion of classrooms and schools as,

enclosed, segmented space, observed at every point, in which individuals are inserted in a fixed place, in which the slightest movements are supervised, in which all events are recorded, … in which power is exercised without division, according to a continuous hierarchical figure, in which each individual is constantly located, examined.

The values, standards and rules of conduct were explicitly stated and these were beyond the control of the pupils. The activities and practices that represented their curriculum at school had no connections with fishing and farming activities, even though they were thought agriculture at school. Therefore, what they did at school had nothing to do with their everyday farming and fishing activities. During an informal conversation between the researcher and head of the school, he said,

The children can stay home if they want to be farmers or fisher folks. What they do at their various homes can’t be tolerated here. We are polishing them for the world, not just their community.

6. Policy implications

High child labour rates are usually associated with lack of growth and developments in reports and studies, particularly those funded by the World Bank and ILO. It is assumed that development necessitates the abolition of child labour (International Labour Organisation [ILO], 2015). The potential benefits of children’s engagement in works may not be acknowledged, and so are usually not evaluated against the cost in the lives of children. It is often considered that children should be kept out of the workplace. There is no discussion of how working children can be protected, how the benefits accruing to working children may be safeguarded and what constitutes, for children, decent work (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018; Bourdillon, Citation2017; Jijon, Citation2020). Benefits of allowing children to engage in work to their development and total well-being highlight the disadvantages of depriving children of engaging in all forms of works. Not every work that breaches international norms for minimum employment age should be associated with hazardous work. Contrarily, according to the ILO (Citation2017, p. 18) child labour is work that is dangerous or detrimental to children or hampers their development, but maintains that the Minimum Age Convention is “the fundamental standard of child labour.” The ILO recognises that certain works done by children can be helpful to children, but it pays no attention to how such advantages can be guaranteed, and it assumes without explanation that such benefits do not lay in activity prohibited by its minimum age rules (Aufseeser et al., Citation2018). The UNOCRC adds its voice to ILO’s assumptions by asserting that there should be protection of every child’s right against works that are hazardous and exploitative and continues to normalise the conventions on conditions of employment and minimum age (Aufseeser, Citation2014). The International Labour Organization’s Convention 182 on the “worst forms of child labour” now outlaws all forms of children’s works that are considered hazardous or harmful to children’s total development, regardless of age. Bourdillon (Citation2017) suggests, therefore, that there is the urgent need to discard Convention 138 since it simply adds to Convention 182 prohibitions which further prohibit works that are not thus hazardous. This policy discriminates against children rather than defending their rights, and international child protection groups who promote it harm rather than protect children, especially those marginalised.

Even though there is a widespread belief that minimum age legislation can protect children from exploitative and harmful work, there is no adequate research that links exploitation, hazards, and harm on the one hand, with age and employment on the other; however, there are numerous case studies indicating that children’s well-being can be harmed by being removed from work due to minimum age standards (see, Bharadwaj et al., ; Bourdillon, Citation2017; Bourdillon et al., Citation2011; Edmonds & Shrestha, Citation2012). Studies that look at how policy and intervention in regard to children’s engagement in work holistically influence children’s wellbeing are rare since it is often considered that children gain from being stopped from working. According to Aufseeser (Citation2014), most studies and organisations concentrate on quantity of work done by children as most appropriate way of assessing working children rather than evaluating outcomes in children’s life. For instance, the Food and Agriculture Organisation Bhullar et al. (Citation2015) in their book, “Handbook for monitoring and evaluation of child labour in agriculture” did not offer any recommendations for the assessment of the benefits accrued to marginalised working children. The report fully conformed with international labour standards without any regard for the extent to which child labour benefits children. Recommendation in such reports lead to campaigns for the total eradication of child labour without thinking of effects on these children (Bourdillon, Citation2017).

According to Aufseeser et al. (Citation2018), campaigns to eradicate child labour may cause havoc in children’s lives by removing their only source of livelihoods. Concerned for Working Children (Citation2015), similarly, observes that most campaigns against working children end up terrorising them and take them away from their parents or families. Bhullar et al. (Citation2015) observed that most of the working children rescued in India from the garment industry later on went back to work in the same garment industry. For these children, the opportunity to be taught a trade regardless of the nature of working condition was far better compared to the lack of opportunities in their villages. Nonetheless, most of the organisations find no contradiction in their campaigns to ban child labour as part of their efforts to enhance the children’s quality of life (Hoque, Citation2021; Jijon, Citation2020; Okyere et al., Citation2021).

Children who wish to work are occasionally refused help on the basis that children should not be working (Muoki, Citation2015). Children’s efforts are dismissed as “help” and go underpaid due to the shame associated with child labour. Aufseeser et al. (Citation2018) conclude that children are properly involved in all types of labour for their families in rural areas, but they are barred from performing benign chores in export-oriented family plantations, and so miss out on the learning opportunities that such duties bring. These children are usually denied the opportunities of learning through work as they grow up, thus their acquisition of productive skills, as well as gradual entrance into the labour market, is hampered (Muoki, Citation2015). According to Aufseeser et al. (Citation2018) this could suffer further obstruction policies interventions that are against child labour. Notwithstanding, most governments give little attention to excessive or dangerous unpaid domestic labour. Liebel (Citation2015) noted the extent to which Bolivia’s government responded to working children’s complaints in 2014 and changed its Children’s Code to accommodate their wants and requirements, enabling them to earn under protected conditions.

Instead of applauding this focus on children’s issues, child and human rights experts blasted it as a step backward in the campaign against the elimination of child labour. Children would benefit from paying attention to both signs of benefits and harms to working children rather than assumed values in all of these instances (Bourdillon, Citation2017; Jijon, Citation2020; Liebel, Citation2015).

7. Conclusion and recommendation